Background: Ubiquitination-dependent proteasome degrades CRY1. However, the deubiquitination enzyme for CRY1 is unknown.

Results: USP2a deubiquitinates and stabilizes CRY1 in vitro and in vivo. TNF-α stabilizes CRY1 via USP2a.

Conclusion: USP2a functions to stabilize CRY1 during a circadian cycle and in response to TNF-α treatment.

Significance: USP2a-dependent stabilization of CRY1 may mediate disruption of the clock function during inflammation.

Keywords: Circadian Clock, Clock Genes, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), Ubiquitin-dependent Protease, Ubiquitination, Clock Protein

Abstract

The mammalian circadian clock coordinates various physiological activities with environmental cues to achieve optimal adaptation. The clock manifests oscillations of key clock proteins, which are under dynamic control at multiple post-translational levels. As a major post-translational regulator, the ubiquitination-dependent proteasome degradation system is counterbalanced by a large group of deubiquitin proteases with distinct substrate preference. Until now, whether deubiquitination by ubiquitin-specific proteases can regulate the clock protein stability and circadian pathways remains largely unclear. The mammalian clock protein, cryptochrome 1 (CRY1), is degraded via the FBXL3-mediated ubiquitination pathway, suggesting that it is also likely to be targeted by the deubiquitination pathway. Here, we identified that USP2a, a circadian-controlled deubiquitinating enzyme, interacts with CRY1 and enhances its protein stability via deubiquitination upon serum shock. Depletion of Usp2a by shRNA greatly enhances the ubiquitination of CRY1 and dampens the oscillation amplitude of the CRY1 protein during a circadian cycle. By stabilizing the CRY1 protein, USP2a represses the Per2 promoter activity as well as the endogenous Per2 gene expression. We also demonstrated that USP2a-dependent deubiquitination and stabilization of the CRY1 protein occur in the mouse liver. Interestingly, the pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, increases the CRY1 protein level and inhibits circadian gene expression in a USP2a-dependent fashion. Therefore, USP2a potentially mediates circadian disruption by suppressing the CRY1 degradation during inflammation.

Introduction

Many physiological activities, such as the sleep-wake cycle, blood pressure fluctuations, and lipid and glucose metabolism, follow a 24-h circadian rhythm to allow mammals to adjust to environmental cues (1–3). These circadian activities are tightly synchronized by the molecular clock, which is driven by an interlocked transcriptional and translational feedback loop (2, 3). During a normal circadian cycle, the two positive regulators, BMAL1 and CLOCK, drive the expression of the negative regulators, including Crys (Cry1 and Cry2), Pers (Per1, Per2, and Per3), as well as Rev-erbα (4–7). Subsequently, CRY and PER proteins form a heterodimer complex and translocate back into the nucleus where they directly bind the BMAL1-CLOCK complex, repressing their own transcription to end the current cycle. Changes in clock protein stability in the negative feedback loop can impact both the period length and amplitude of circadian oscillations (8, 9).

Mammalian CRY1 protein shows a strong circadian oscillation in the liver, reaching its trough and peak levels at ZT8 and ZT15, respectively (10–12). AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent phosphorylation and subsequent FBXL3 E3 ligase-mediated ubiquitination have been shown to degrade CRY1 during a normal circadian cycle (13–16). A nonphosphorylatable CRY1 mutant (S71A) no longer interacts with FBXL3 and becomes resistant to AMP-activated protein kinase activator-induced degradation (15). However, the CRY2 protein has been demonstrated to be phosphorylated at Ser-552 by GSK3β prior to degradation by the proteasome system (17, 18). Although both CRY1 and CRY2 proteins are modified by ubiquitination, the critical lysine residues of either CRY1 or CRY2 protein serving as ubiquitination sites have not been identified yet.

Several genetic mouse models have revealed the circadian function of the mammalian CRY1 (14, 16, 19). The Cry1 null mice display a ∼60-min shorter free-running period (19). In contrast, mice with the Fbxl3 mutation display a 26-h circadian period probably due to the delayed CRY1 protein degradation (14, 16). Both mouse models indicate that the temporal abundance of the CRY1 protein is critical for determining the circadian period length. However, whether the circadian expression of the CRY1 protein also contributes to amplitude change has not been fully addressed (20, 21). Besides its role in circadian rhythms, the CRY1 protein may also be involved in inflammatory response (22), glucose metabolism (23), and blood pressure control (24). Whether the CRY1-dependent circadian function drives these diverse biological effects of CRY1 remains to be determined. A better understanding of the pathway controlling the CRY1 protein oscillations will help with understanding the physiological functions of CRY1.

A large group of cysteine proteases called deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs)2 counteracts the ubiquitin-dependent degradation to prevent targeted destruction by proteasomes (25–27). The mammalian genome encodes about 80–90 DUB enzymes with only a handful studied for their specific substrates and functions. DUB proteins exhibit several ubiquitination-related functions, including processing and recycling of ubiquitin after removal of the polyubiquitin chain of the specific substrate proteins (26). A recent large scale proteomic study (27) clearly demonstrated a large network of DUB enzymes within several major pathways, although relatively little is known about the physiological substrates of each DUB enzyme. The targets of DUB enzymes include transcription factors (28, 29), cell surface receptors (30), apoptosis (31), and Wnt signaling (32, 33).

The deubiquitinating enzyme USP2 has two isoforms due to alternative splicing, USP2a (69 kDa) and USP2b (45 kDa). USP2a targets multiple substrates for protein stability, including p53 (34), fatty acid synthase (35), cyclin D1 (36), and mouse double minute X (MDMX) (37). The Usp2a mRNA is ubiquitously expressed in most mouse tissues (38) and modulated by cytokines such as IL-1β (39), TNF-α (40), and adiponectin (41) in a cell type-specific manner. Aberrant expression of the Usp2a mRNA has been found in several types of human cancers (42), including prostate cancer (35, 43), ovarian adenocarcinoma (44), and breast cancer (37, 41). Remarkably, the Usp2a mRNA displays a robust circadian oscillation and has been considered as a direct circadian output gene (45, 46). In the mouse liver, Usp2a mRNA peaks around ZT16 with robust amplitude (45). Such oscillation is completely lost in Clock mutant mice (46). A recent study showed that deletion of the Usp2 gene impairs the light-induced phase shift, suggesting USP2 may mediate the signal-dependent regulation of the circadian clock (47). However, the circadian targets of USP2a still remain elusive.

In this study, we show that USP2a interacts with the clock protein CRY1 in response to serum shock synchronization. USP2a promotes the CRY1 deubiquitination and protein stabilization in both cell cultures and the mouse liver. Depletion of USP2a not only dampens the CRY1 protein oscillation during a circadian cycle but also impairs the CRY1-mediated circadian gene expression. More importantly, we discovered that TNF-α treatment stimulates Usp2a gene expression and promotes CRY1 protein stabilization in a USP2a-dependent manner. We thus identified USP2a as a novel cellular mediator for inflammation-induced disruption of the circadian clock functions. Taken together, the CRY1-specific deubiquitinating enzyme USP2a represents a potential enzymatic target for therapeutic intervention aimed at the CRY1 protein turnover.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Plasmids

The full-length Usp2a expression vector was initially purchased from Open Biosystems (Thermo Scientific) and then subcloned into the pQCXIP vector (Clontech). Usp2a enzyme-dead mutants were generated via QuikChange site-direct mutagenesis (Agilent). Usp2a shRNA knockdown construct was made by ligating the targeting oligonucleotide sequence into the RNAi-Ready pSIREN-Retro-Q vector (Clontech). The two targeting sequences for human USP2a are 5′-AGAUUGUGGUUTCUGUUCU-3′ and 5′-CCGCGCUUUGUUGGCUAUA-3′. The shRNA targeting sequence for mouse Cry1 is 5′-GGAAAUUGCUCUCAAGGAAGU-3′. The shRNA targeting sequences for mouse Fbxl3 are 5′-GCUUUAUGGAUCUACCAAAGU-3′.

The mPer2 promoter-driven luciferase reporter construct is a generous gift from Dr. Hogenesch at University of Pennsylvania. All plasmids were confirmed by automated sequencing analysis. TNF-α was purchased from Sigma. All the antibodies used in this work were anti-CRY1, PER1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-FLAG anti-ubiquitin, anti-MYC (Sigma), anti-USP2 (Abgent), and anti-FBXL3 (Abcam). Anti-M2-agarose beads were also purchased from Sigma. MG132 was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth, PA).

Generation of Recombinant Adenovirus

Ad-Block-iT shUsp2a and shLacZ control viruses were made using BLOCK-iT Adenoviral RNAi Expression System (Invitrogen). Ad-Easy-Usp2a virus was made according to instructions of the AdEasy Adenoviral Vector System (Agilent). All the viruses were concentrated by ultracentrifuge via cesium chloride gradient and dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline buffer containing 10% glycerol prior to animal injection. Primers for making pAd-BLOCK-iT shUsp2a construct are as follows: top, 5′-CACCGCTGAGATCTGACATCATTGGCGAACCAATGATGTCAGATCTCAGC, and bottom, 5′-AAAAGCTGAGATCTGACATCATTGGTTCGCCAATGATGTCAGATCTCAGC.

Cell Culture and Stable Cell Line

All cell lines (293T, Huh7, HepG2, and Hepa-1) except NIH3T3 cell were maintained in minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C under 5% CO2. A 293T-derived stable cell clone expressing either USP2a shRNA (shUSP2a-1 and shUSP2a-2) or shCon vector was generated by transient transfection and subsequent selection in medium containing puromycin (1.5 μg/ml) for 3 weeks. The positive clones were confirmed by both RT-PCR and immunoblotting.

Adenovirus Tail Vein Injection in Mice

All animal care and use procedures were in accordance with guidelines of the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Wild-type C57BL/6J male mice (between 8 and 10 weeks old) were maintained on a 12:12 light/dark cycle with free access to standard diet and water. For adenoviral injections, 1 × 1012 plaque-forming units per recombinant adenovirus were administrated via tail vein injection. For each virus, a group of four to five mice were injected with the same dose treatment. 10 days after injection, mice were sacrificed around ZT8 after overnight fasting, and liver tissues were harvested for protein analysis.

In-cell Ubiquitination Assay

Either shCon- or shUSP2a-expressing 293T cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding Cry1 and ubiquitin. 36 h after transfection, cells were treated with 2 μm MG132 for 16 h before lysis in 1% SDS denaturing buffer and boiling at 95 °C for 10 min. Cell lysates then were diluted 10-fold in FLAG IP buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40) and pre-cleared by centrifugation at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was used in IP buffer with anti-FLAG antibody. Immunocomplexes were resolved on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and detected with anti-ubiquitin (Sigma). For detecting the endogenous CRY1 protein ubiquitination, lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-CRY1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:200 dilution. For detecting the CRY1 ubiquitination in mouse liver, the liver tissues were homogenized in RIPA buffer to obtain the whole cell lysates. About 2 mg of total liver protein lysates were treated in denaturing conditions (as above) and then subjected to immunoprecipitation with indicated antibodies.

In Vitro Deubiquitination Assay

Both Usp2a WT and 290CA mutant were subcloned into pGEX4T.1 vector and transformed BL-21 competent cells. GST fusion proteins were induced by isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 1 mm and captured by glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). Elution buffer was used to elute GST fusion proteins off the beads for in vitro deubiquitination assay. CRY1-FLAG conjugates were captured by anti-FLAG M1 beads (Sigma) after lysis of transfected 293T cells. 10 μl of immunoprecipitated proteins were incubated with 20 μl of purified GST-USP2a-WT or -290CA mutant at 37 °C in reaction buffer (Tris 50 mm, pH 7.5, NaCl 150 mm, EDTA 2 mm, and DTT 2 mm) for 1 h. N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) was added at 10 mm as positive control for DUB inactivation. Reactions were mixed with 5× SDS loading buffer and denatured at 95 °C for 5 min before immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Cell pellets were lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor and 50 mm NaF and incubated on ice for 20 min. The protein lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatants were collected and quantified using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit. For detecting the clock proteins in the nuclear fraction, cells or tissues were first exposed to hypotonic buffer, and the cytosolic fractions were separated by low speed centrifugation. The nuclear pellets were then resuspended in RIPA buffer and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C to obtain nuclear fractions. Blots were probed with the following primary antibodies: anti-CRY1, anti-USP2a, and anti-ubiquitin (Sigma). The standard immunoprecipitation method has been described previously (8). For detecting the protein interaction between FLAG-CRY1 and Myc-USP2a, the cells were treated with 2 h of serum shock and lysed in RIPA buffer. The cell lysates were then incubated with specific antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The immunocomplex was captured by adding 30 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads and incubating at 4 °C for 1 h. The beads were washed five times in RIPA buffer and eluted in 30 μl of 2× SDS loading buffer. Western blotting was performed to detect the presence of targeted proteins.

Transfection and Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

Cells were plated in a 24-well plate overnight before transfection with mPer2 promoter luciferase reporter alongside either expression of shRNA vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). 48 h post-transfection, cells were lysed for luciferase activity assay measurement on BioTek Synergy 2 microplate reader. β-Galactosidase construct was also co-transfected in each well for normalizing luciferase activity.

Serum Shock and Synchronization Study

Hepa-1c1c-7 cells were used in the synchronization study. The confluent cells were first transduced with Ad-shLacZ or Ad-shUsp2a for 16 h. 50% horse serum was then added 48 h later as described previously (48). Cells then were collected for both mRNA and protein analysis at 4-h intervals between 16- and 60-h time points. Densitometry analysis was performed using the band analysis tool provided by AlphaImager (ProteinSimple). The protein level of CRY1 was normalized by the level of RAN, the loading control protein.

cDNA Synthesis and Q-PCR

Total cellular RNA extraction was performed with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and chloroform. cDNA was synthesized using Verso cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Surrey, UK) and subjected to Q-PCR using Absolute Blue SYBR Green ROX Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Surrey, UK) on an ABI 7900 HT thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The value of each cDNA was calculated using the ΔΔCt method and normalized to the value of housekeeping gene control (18 S RNA). The data were plotted as fold of change. The primer sequences used in this study are: hUsp2 forward, 5′-ctgccctgaatacctggtcg-3′, and reverse, 5′-tcggtaggttgggctgatgat-3′; mUsp2 forward, 5′-ctgagagattactgcctccag-3′, and reverse, 5′-ctcagatgggctcaccacatc-3′; hPer2 forward, 5′-agttggcctgcaagaaccag-3′, and reverse, 5′-actcgcatttcctcttcaggg-3′; hDbp forward, 5′-gttgatgacctttgaacccga-3′, and reverse, 5′-cctccggcacctggattttt-3′; hCry1 forward, 5′-acaggtggcgatttttgcttc-3′, and reverse, 5′-tccaaagggctcagaatcatact-3′; mPer2 forward, 5′-ttccactatgtgacaagcggagg-3′, and reverse, 5′-cgtatccattcatgtcgggctc-3′; mBmal1 forward, 5′-aaccttcccgcagctaacag-3′, and reverse, 5′-agtcctctttgggccacctt-3′.

Real Time Bioluminescence Assay

The U2OS-Bmal1-luc cells (21) were kindly provided by Dr. John Hogenesch (University of Pennsylvania) and maintained in DMEM with 5% FBS and 1 μg/ml puromycin. Manipulation of USP2a expression was achieved by transient transfection with the expression vector for Usp2a overexpression or shRNA knockdown. Two days post-transfection, the medium was changed to phenol red-free DMEM containing 5% FBS, nonessential amino acids, 1× penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine, 20 mm HEPES, 0.1 mm luciferin (Promega), 100 nm dexamethasone, and 10 μm forskolin for synchronization. The dishes were covered with sterile glass coverslips, sealed with sterile vacuum grease, and placed into a Lumicycle (Actimetrics). Bioluminescence levels were measured every 10 min for 5 days or more. The data analysis was performed using the Lumicycle analysis program (Periodogram graph, poly order 7), and means of both amplitude and period were extracted and exported for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

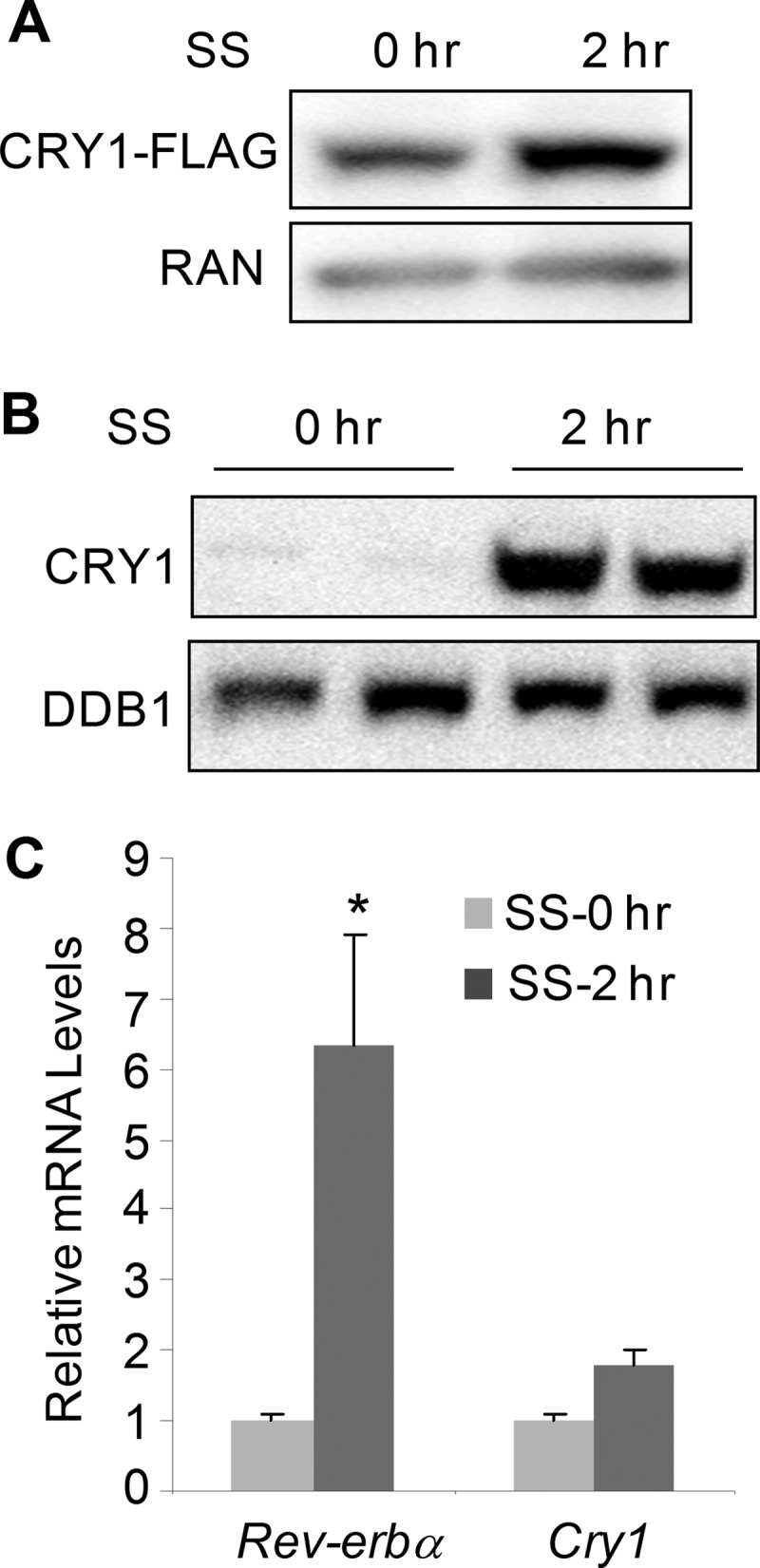

Serum Shock Potently Increases the Expression of the CRY1 Protein

Serum shock can synchronize the molecular circadian clock in various cell types (48, 49). We previously reported that serum shock transiently induces degradation of FLAG-REV-ERBα, a key negative component of the circadian loop (8, 50). This observation led us to ask whether other clock proteins are also affected by serum shock. To test this notion, we generated stable cell lines expressing various FLAG-tagged clock proteins (CRY1-FLAG, PER1-FLAG, PER2-FLAG, and BMAL1-FLAG) to study their responses to serum shock. In contrast to FLAG-REV-ERBα, which is usually down-regulated by serum shock, the CRY1-FLAG was stabilized upon serum shock (Fig. 1A), whereas other clock proteins, including PER1-FLAG, PER2-FLAG, and BMAL1-FLAG, are largely unchanged (supplemental Fig. 1). Moreover, this stabilization also occurred for the endogenous CRY1 protein in 293T cells (Fig. 1B). The potent effect of serum shock was further observed in other cell lines, which have been used in circadian studies, including NIH3T3, primary mouse hepatocytes, and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (supplemental Fig. 2A). We verified the specificity of the CRY1 antibody by using the protein lysates isolated from cells transfected with the Cry1shRNA vector (supplemental Fig. 2B). It has been shown that serum shock can induce the mRNA expression of human BMAL1 and REV-ERBα (50). We therefore examined the mRNA level of CRY1 in cells treated with serum shock. Interestingly, the quantitative RT-PCR only showed a modest change in CRY1 mRNA level compared with the induction of both BMAL1 and REV-ERBα (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. 3A), indicating that the potent increase in the CRY1 protein during the course of serum shock is not primarily through elevated transcription.

FIGURE 1.

Serum shock induces the expression of the CRY1 protein. A, serum shock (SS) induced an increase in CRY1-FLAG protein in human 293T cells stably transfected with the Cry1-FLAG expression vector. B, endogenous CRY1 protein level in 293T cells after serum shock. The level for DDB1 protein was shown as loading control. C, endogenous mRNA for human REV-ERBα and CRY1 in 293T cells treated with serum shock. The data were plotted as mean ± S.D. of triplicates. *, p value <0.05 by Student's t test.

Serum Shock Enhances the CRY1 Protein Deubiquitination by Inducing the Deubiquitinating Enzyme USP2a

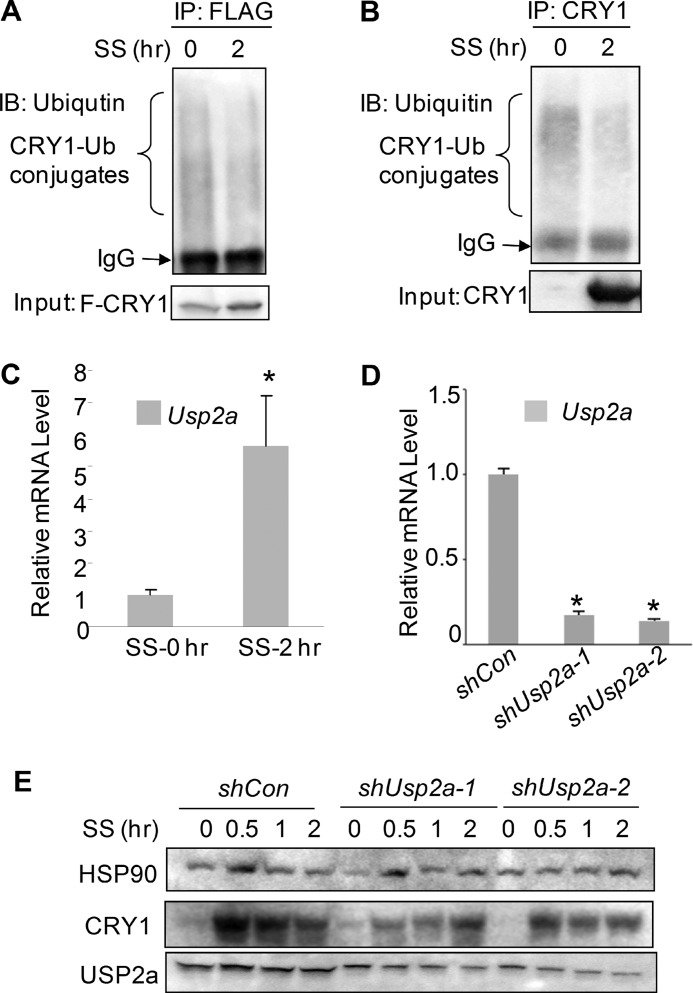

The fact that the Cry1 mRNA was only modestly induced upon serum shock prompted us to speculate that this induction mainly occurs at the post-transcriptional level. Because CRY1 has been shown to be a direct target of ubiquitination-dependent degradation (13, 14, 16), we examined the ubiquitination status of CRY1 upon serum shock via immunoprecipitation of the ubiquitin-conjugated CRY1. Indeed, the total ubiquitinated CRY1 was reduced in serum shock-treated samples in comparison with the control. This is true for both FLAG-tagged and endogenous CRY1 protein (Fig. 2, A and B), indicating that CRY1 stabilization after serum shock is indeed due to a reduction in its ubiquitination status. We also observed that serum shock induced the expression of FBXL3, a known CRY1 E3 ligase involved in its proteasome-dependent degradation (supplemental Fig. 3B). Although there was an increase of the basal level of CRY1 protein in Fbxl3-depleted Hepa-1 cells, Fbxl3 knockdown by shRNA did not block serum shock-induced CRY1 stabilization (supplemental Fig. 3C). Thus, it is unlikely that FBXL3 contributes to the CRY1 protein stabilization upon serum shock. In conclusion, our results indicate that CRY1 stabilization is likely due to an increased deubiquitination rather than a loss of active ubiquitination.

FIGURE 2.

Serum shock promotes deubiquitination of CRY1 via induction of USP2a. A, ubiquitination status of CRY1-FLAG upon serum shock (SS). The 293T Cry1-FLAG stable cells were treated with serum shock for 1 h and then lysed for immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody in the denaturing conditions. The amount of ubiquitin-CRY1-FLAG conjugates was detected by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-ubiquitin. B, ubiquitination status of the endogenous CRY1 protein upon serum shock. 293T cells were treated with serum shock for 1 h before lysis for immunoprecipitation with anti-CRY1 antibody in denaturing conditions and immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin. Input samples (Input) are shown as well. C, mRNA levels of USP2a in 293T cells after serum shock were determined by real time Q-PCR. The data were plotted as mean ± S.D. of three replicates. *, p value < 0.05 by Student's t test. D, knockdown of USP2a by two shRNA targeting sequences (shUSP2a-1 and shUSP2a-2) in 293T cells was confirmed by real time Q-PCR. The data were plotted as means ± S.D. of triplicates. *, p value <0.05. E, effect of USP2a knockdown on CRY1 protein stabilization after serum shock. 293T cells stably transfected with shRNA for USP2a were serum-shocked for the indicated time points before anti-CRY1 immunoblotting. The USP2a protein levels were detected by immunoblotting.

To determine whether DUB enzymes are involved in reducing the overall CRY1 ubiquitination upon serum shock, we measured the expression of Usp2a, which has been recently associated with circadian rhythm systems and repeatedly reported in circadian expression arrays (45–47). We observed a potent induction of the Usp2a mRNA in 293T cells (Fig. 2C) as well as Hepa-1c1c-7 (Hepa-1) cells (supplemental Fig. 4A) upon serum shock. We also measured USP2a protein in Hepa-1 cells following serum shock (supplemental Fig. 4B). Such treatment specifically enhanced the level of USP2a (69 kDa) but not the other isoform USP2b (45 kDa) (supplemental Fig. 4B). Given the prominent role of USP2a in regulating the stability or the function of proteins such as cyclin D1 (36), MDMX (37), ENaC (51), Aurora kinase (52), and TRAF2 (53), we sought to determine whether USP2a affects the protein turnover of CRY1 through modulating its ubiquitination status. We therefore generated 293T stable cell lines expressing two Usp2a shRNA vectors (shUsp2a-1 and shUsp2a-2) and achieved 90% knockdown efficiency at the mRNA level (Fig. 2D). To test the hypothesis that USP2a is directly responsible for CRY1 protein stabilization, we treated the shUSP2a-expressing 293T stable cells with serum shock for the indicated time points and observed a significant reduction in the total CRY1 protein in comparison with shRNA control (Fig. 2E). Such results are supportive of our hypothesis that USP2a is required for CRY1 protein stabilization upon serum shock.

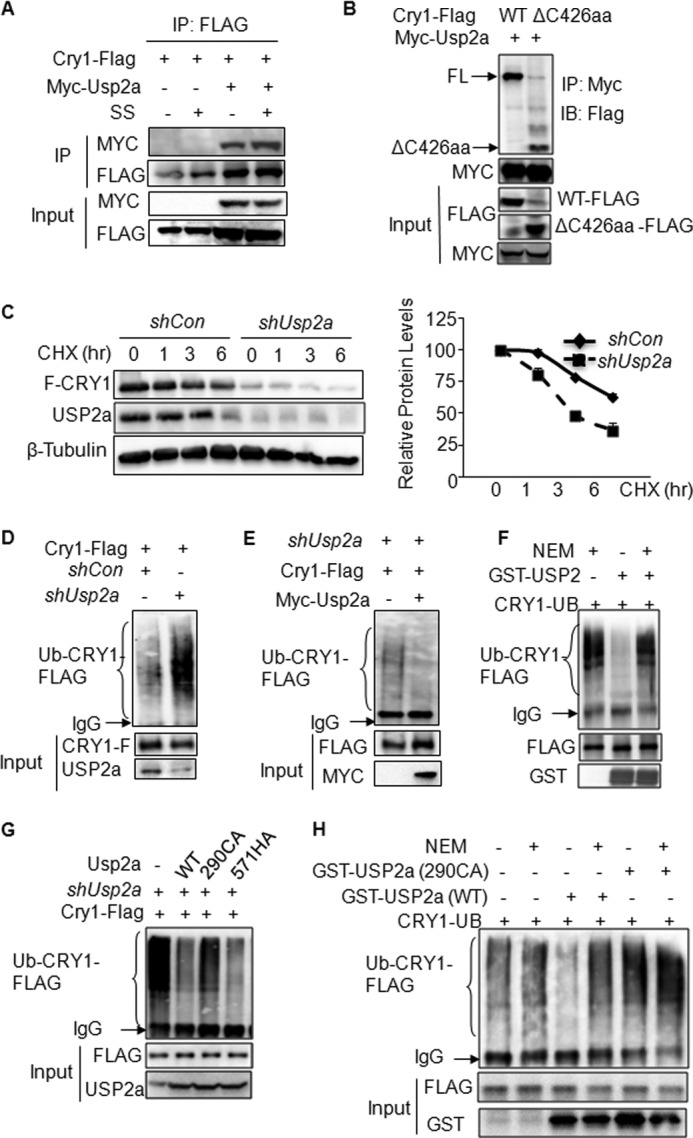

USP2a Interacts with CRY1 and Regulates Its Ubiquitination

To address whether USP2a directly acts on CRY1 to control its protein stability, we first asked whether these two proteins interact with each other. In cells co-transfected with both Cry1-FLAG and Myc-Usp2a, a clear protein-protein interaction between CRY1-FLAG and MYC-USP2a was detected following anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, serum shock treatment did not further increase the interaction between these two proteins, suggesting that the increased USP2a protein expression may be sufficient to mediate the serum shock effect. To map the region within the CRY1 protein for interaction with USP2a protein, we created both N- and C-terminal truncation mutants of CRY1 and tested their interaction properties with USP2a. We observed that both CRY1 wild-type and C-terminal deletion mutant (ΔC426aa) interacted strongly with full-length USP2a (Fig. 3B). We were not able to detect a clear interaction between USP2a and CRY1 N-terminal deletion mutants because the expression of those mutants (ΔN50aa and ΔN150aa, data not shown) was barely detectable even in the presence of MG132. Together, our data suggest that the N-terminal region (N180aa) of CRY1 is critical for both maintaining the structural integrity and interacting with USP2a. To address whether USP2a directly impacts CRY1 protein degradation, we measured the CRY1-FLAG protein abundance in cells expressing shUSP2a after exposure to protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) (Fig. 3C, both panels). The CRY1-FLAG protein in shRNA control-transfected cells has a half-life of more than 6 h, whereas the same protein has a half-life of about 3 h in shUsp2a-expressing cells. To address whether USP2a modulates CRY1 ubiquitination to control its protein stability, we established an in-cell ubiquitination protocol, which allows us to examine the ubiquitination of either CRY1-FLAG or endogenous CRY1 protein. In this ubiquitination assay, we transfected stable cell lines expressing either shRNA control or shUsp2a (the shUsp2a-1 293T cell line used in Fig. 2D) along with Cry1-FLAG expression construct. The protein lysates were prepared after overnight treatment with MG132 and were then used in anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation assay. The ubiquitination status of CRY1 was confirmed by the formation of ubiquitin-CRY1-FLAG conjugates, which can be detected as a smear by anti-ubiquitin antibody. Indeed, we observed a dramatic increase in the formation of ubiquitin-CRY1-FLAG conjugates along with the reduced CRY1 protein level in 293T stable cells depleted of USP2a, suggesting that USP2a stabilizes the CRY1 protein by actively removing the polyubiquitin chain (Fig. 3D). Moreover, overexpression of the wild-type mouse USP2a was able to completely remove the CRY1-FLAG ubiquitination in shUsp2a-expressing 293T stable cells (Fig. 3E). Next, we set up an in vitro deubiquitination assay to test whether USP2a functions directly as a DUB enzyme for the ubiquitinated CRY1 protein using the recombinant GST-USP2a protein. We confirmed the enzymatic activity of GST-USP2a by its ability to remove the ubiquitin moiety from TRAF2, a recently identified target of USP2a (data not shown) (53). As shown in Fig. 3F, we observed an almost complete loss of ubiquitination signal in the presence of GST-USP2a, which was inhibited by the DUB inhibitor NEM.

FIGURE 3.

USP2a interacts with CRY1 protein and promotes its deubiquitination. A, 293T cells were transfected with Cry1-FLAG in the presence or absence of Myc-Usp2a. Cells were then treated with 2-h serum shock and harvested for immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG. The presence of MYC-USP2a was detected with anti-MYC. B, USP2a binds to the N-terminal region of the CRY1 protein. Both Cry1 full-length and ΔC426aa truncation mutant were transfected into 293T cells along with Myc-Usp2a. 48 h later, cells were harvested for immunoprecipitation with anti-MYC and immunoblotting (IB) with anti-FLAG. C, abundance of CRY1-FLAG protein after CHX treatment and in the presence of USP2a knockdown. The same amount of Cry1-FLAG plasmid was transfected with either shCon vector or shUSP2a vectors (a mixture of equal amount of shUSP2a-1 and shUSP2a-2). 48 h later, the cells were treated with CHX (100 μg/ml) for the indicated time duration and then harvested for detecting levels of CRY1-FLAG and USP2a. The level of β-tubulin was used as loading control. A representative of three experiments with similar results is shown here. Quantification of CRY1-FLAG protein levels during the course of CHX treatment was plotted and is shown in the right panel. Each value represents means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. D, enhanced ubiquitination status of CRY1-FLAG in 293T cells stably expressing shUSP2a. Cry1-FLAG expression vector was transfected into 293T stable cell lines (shCon versus shUSP2a-1) before anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation. The ubiquitin-conjugates were detected by anti-ubiquitin. E, ubiquitination status of CRY1-FLAG was reduced by overexpression of wild-type mouse USP2a in the shUSP2a 293T stable cell. The Usp2a vector encodes the mouse USP2a protein, whereas the shUSP2a vector targets the human USP2a protein. F, in vitro deubiquitination assay of HA-tagged ubiquitin conjugates of CRY1-FLAG in the presence of GST-USP2a-WT. Immunoprecipitated ubiquitin-CRY1-FLAG conjugates were incubated with purified GST-USP2a-WT protein purified from BL21 cells at 37 °C for 1.5 h. Ubiquitinated CRY1 proteins were detected by anti-HA immunoblotting. NEM was used as positive control for DUB enzyme inhibition. Anti-GST antibody was used to measure GST fusion proteins in each reaction. G, only the mouse USP2a-WT and 571HA mutant but not 290CA mutant reduced the ubiquitinated CRY1-FLAG in shUSP2a 293T stable cells. The Usp2a expression vector encodes the mouse USP2a protein, whereas the shUSP2a vector targets the human USP2a protein. H, in vitro deubiquitination assay of ubiquitin-conjugated CRY1-FLAG in the presence of either GST USP2-WT or GST USP2a-290CA. Anti-HA immunoblotting was used to detect the HA-tagged ubiquitin signal after reaction. Anti-GST antibody was used to measure GST fusion proteins in each reaction.

Mutations of either the highly conserved Cys residue in the Cys box or the His residue in the His box of USP2a have been shown to create enzyme-dead or dominant negative forms of USP2a protein (34, 35). Based upon protein alignment analysis of human and mouse USP2a protein sequences, we created both Cys-box (290CA) and His-box (571HA) mouse USP2a mutants for assessing the importance of its enzymatic activity in CRY1 deubiquitination. In another in-cell deubiquitination assay in Fig. 3G, both the USP2a-WT and 571HA mutant led to a similar reduction of CRY1 ubiquitination, whereas the 290CA mutant failed to decrease the CRY1 ubiquitination. To confirm USP2a-290CA as a loss-of-function mutant, we performed another in vitro deubiquitination assay by incubating the immunoprecipitated ubiquitin-CRY1 conjugates with either purified GST-USP2a-WT or GST-USP2a-290CA before immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. Although GST-USP2a-WT strongly reduced the level of CRY1 ubiquitination, GST-USP2a-290CA was unable to remove the polyubiquitin chain off the CRY1 protein (Fig. 3H). Together, our results indicate that the conserved Cys-290 residue is critical for the USP2a enzymatic activity during the course of deubiquitination of CRY1.

Besides CRY1, other mammalian clock proteins have also been shown to be regulated by ubiquitination-dependent pathways (8, 13, 14, 16, 54–56), raising the question concerning the specificity of the CRY1 regulation by USP2a. Because the USP2a-dependent deubiquitination assay is highly sensitive, we set up a screening for the potential clock proteins targeted by USP2a. USP2a did not reduce the ubiquitination of CRY2-FLAG, BMAL1-FLAG, and PER1-FLAG (supplemental Fig. 5), suggesting that USP2a deubiquitination is specific to the CRY1 protein in the cultured cells. Thus, we established a critical role of USP2a in the regulation of CRY1 protein ubiquitination and degradation.

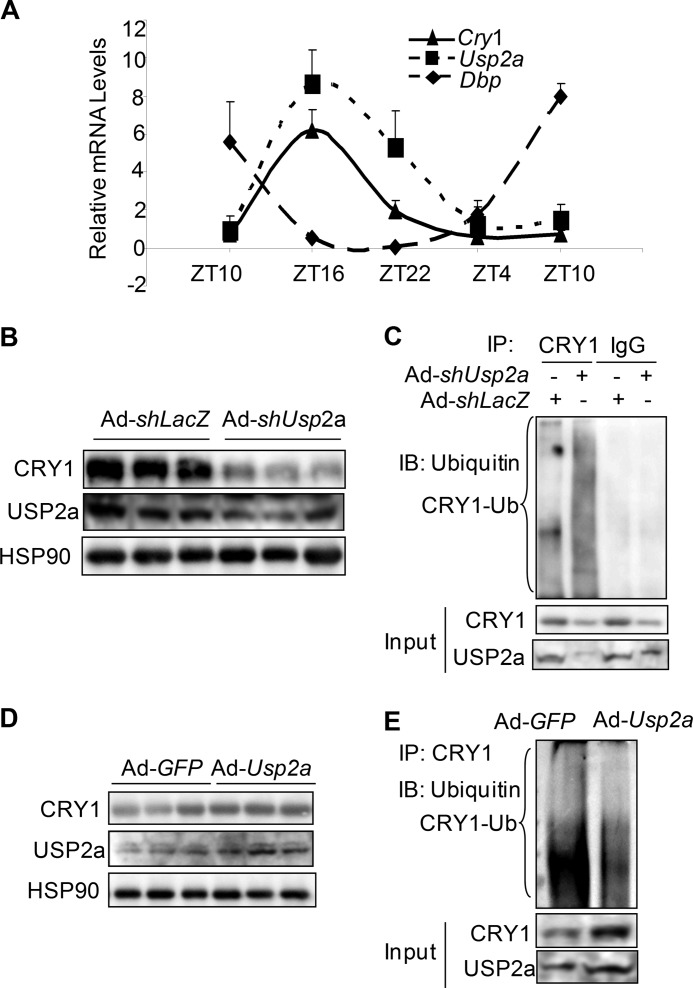

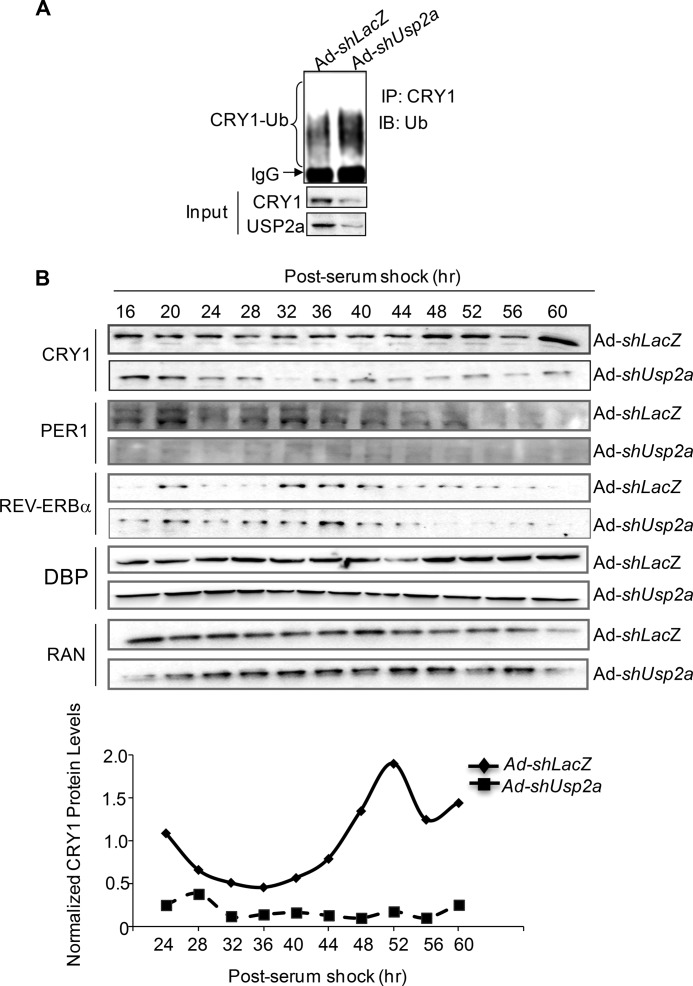

USP2a Deubiquitinates and Stabilizes CRY1 in Vivo

So far we have demonstrated the up-regulation of CRY1 by USP2a upon serum shock in the cultured cell lines. Its role in the regulation of CRY1 protein in vivo still remains to be determined. While examining the mRNA oscillation pattern in the liver isolated from mice housed in 12-h light/dark conditions, we found that the mRNA oscillation of hepatic Usp2a peaked at ZT16 and was in the same phase as that of Cry1, although anti-phasic to another circadian output gene, Dbp (Fig. 4A), consistent with the literature (47). To test whether USP2a regulates CRY1 ubiquitination and stability in vivo, we injected mice with adenoviruses for overexpressing or knocking down mouse Usp2a through tail vein administration. In all three adenoviral shUsp2a-transduced liver lysates, the endogenous CRY1 protein level was remarkably lower than in shLacZ control (Fig. 4B). In addition, Usp2a knockdown boosted the level of CRY1 ubiquitination (Fig. 4C). Conversely, adenovirus-mediated Usp2a overexpression led to stabilization of the CRY1 protein and reduced the level of CRY1-ubiquitin conjugates in liver lysates (Fig. 5, D and E). Taken together, our data demonstrate that USP2a-dependent deubiquitination and stabilization of CRY1 are conserved in vivo. To our knowledge, this is the first report that shows CRY1 ubiquitination can be detected and modulated in the mouse liver.

FIGURE 4.

USP2a regulates CRY1 stability through deubiquitination in the mouse liver. A, circadian oscillations of Cry1, Usp2a, and Dbp mRNA levels in circadian liver samples. Liver tissues from five mice were sampled for each time point. B, effect of depletion of Usp2a on the CRY1 protein level in liver lysates from mice injected with the adenoviral Usp2a shRNA through the tail vein. Three mice were injected with either shLacZ control or the shUsp2a adenovirus. C, CRY1-ubiquitin (Ub) conjugates were detected in pooled liver lysates from B by anti-CRY1 immunoprecipitation (IP) and anti-ubiquitin immunoblotting (IB). Mouse IgG was included as control for antibody specificity. D, effect of overexpression of USP2a on the CRY1 protein level in liver lysates from mice injected with Usp2a overexpressing adenovirus (n = 3). The control virus expresses GFP. E, overexpression of USP2a by adenovirus tail vein injection reduced CRY1-ubiquitin conjugates in pooled liver lysates from D.

FIGURE 5.

USP2a regulates circadian oscillation of CRY1 protein in synchronized Hepa-1 cells. A, knockdown of Usp2a by adenoviral shRNA leads to the decreased endogenous CRY1 protein level while enhancing its ubiquitination in mouse Hepa-1 cells. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot; Ub, ubiquitin. B, circadian oscillations of clock proteins during a 60-h circadian study were disrupted by adenoviral shUsp2a expression in Hepa-1 cells after serum shock. The nuclear protein lysates at each time point were pooled from three individual wells and were used in Western blotting for detecting the levels of CRY1, PER1, and REV-ERBα. The level of RAN was used as the loading control. The relative abundance of endogenous CRY1 protein during a circadian cycle was normalized by the loading control protein, RAN, and plotted (bottom panel).

USP2a Regulates the CRY1 Protein Oscillations in Synchronized Hepa-1 Cells

To determine the role of USP2a on the CRY1 protein cycling, we examined the effect of Usp2a depletion on the CRY1 protein oscillation in synchronized Hepa-1 cells, which were previously reported in a circadian study (8). After observing in-phase transcription of both the Usp2a and Cry1 mRNA levels in Hepa-1 cells (supplemental Fig. 6), we applied adenovirus-mediated transduction in those cells to achieve high efficiency of Usp2a knockdown. As observed in 293T cells, depletion of Usp2a with adenoviral shRNA decreased the overall level of CRY1 while increasing its ubiquitination status (Fig. 5A). Next, we performed a circadian study using adenoviral shRNA-transduced Hepa-1 cells after synchronization by serum shock. During a 60-h cycle (CT16 to CT60), depletion of Usp2a not only reduced the overall level of the CRY1 protein but also dampened its oscillations (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, we examined the impact of Usp2a knockdown on three other clock proteins (Fig. 5B). Although the REV-ERBα protein level was slightly increased, there was minimal change for DBP in the case of Usp2a knockdown. In contrast, the PER1 protein was completely destabilized during the circadian cycle. The possible cause for the lowered PER1 protein level might be that the reduced level of CRY1 triggers destabilization of the PER1 protein due to its complex formation with PER1 (57, 58). Together, our results suggest that USP2a is required for deubiquitinating CRY1 and maintaining the robust circadian oscillations of the CRY1 protein in synchronized hepatocytes.

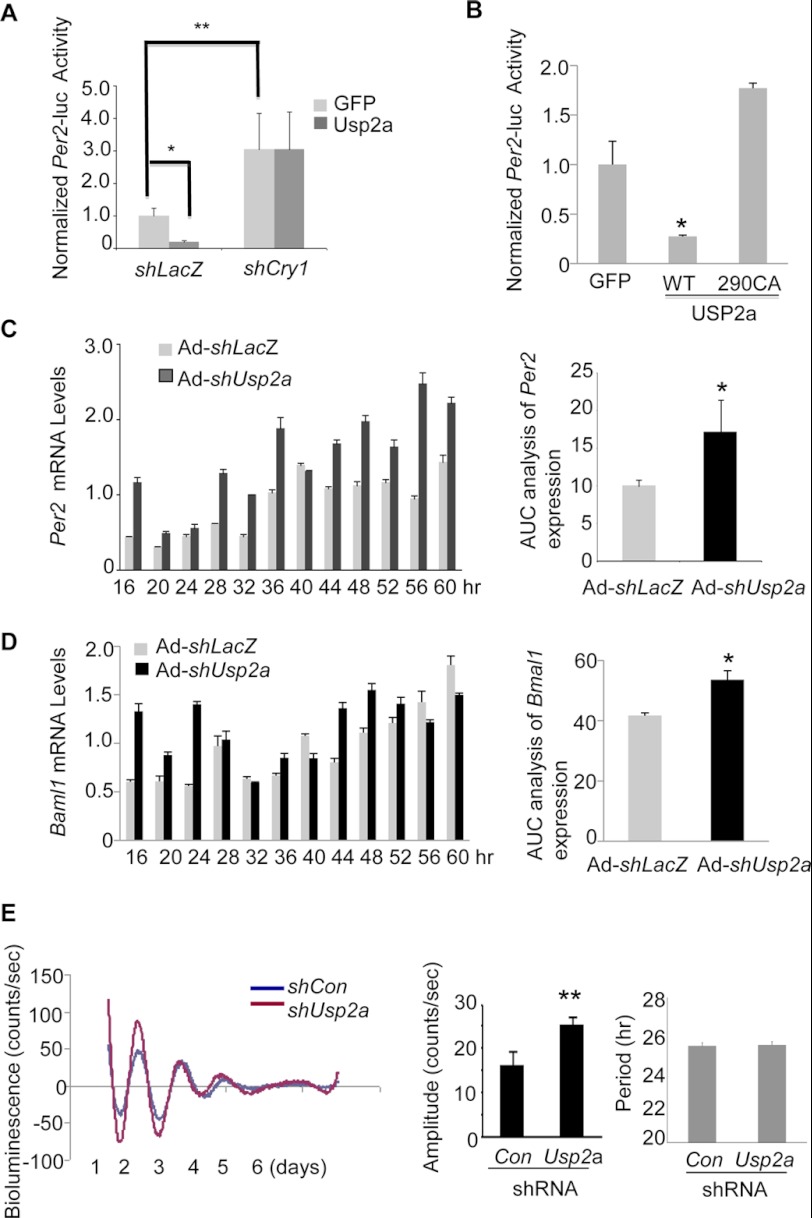

USP2a Regulates the CRY1-dependent Circadian Function

CRY1 functions as a critical component of the negative feedback loop within the circadian network (7, 19, 59). Once inside the nucleus, the CRY1 protein forms a complex with PER to block the transcription activity of BMAL1/CLOCK. Expression of endogenous Per2 and Dbp is sensitive to the CRY1 protein abundance because overexpression of the CRY1 protein in cells potently suppresses Per2 and Dbp transcription (supplemental Fig. 7, A and B). To determine whether USP2a is directly involved in the CRY1-mediated clock gene regulation, we tested the impact of USP2a overexpression on the mPer2 promoter-driven luciferase reporter activity in Hepa-1 cells. Co-transfection of Usp2a suppressed the mPer2-luc activity via CRY1 because adenovirus knockdown of Cry1 abrogated such repression (Fig. 6A). In contrast, co-transfection of USP2a 290CA failed to repress mPer2-luc, indicating that the enzymatic activity of USP2a is required in this process (Fig. 6B). To examine the role of USP2a in the cell autonomous clock, we measured the mRNA oscillations of four core clock genes (Per2, Bmal1, Dbp, and Rev-erbα) between 16 and 60 h after synchronization by serum shock in Hepa-1 cells. Consistent with CRY1 being a repressor of these circadian genes, knockdown of Usp2a led to higher amplitude of oscillations of Per2 (Fig. 6C), Bmal1 (Fig. 6D), and Dbp throughout most time points (supplemental Fig. 8). Moreover, between 24 and 48 h, the knockdown of Usp2a caused earlier peaks of the Per2, Bmal1, and Dbp mRNA expression. The area under the curve analysis confirmed a significant difference between shLacZ and shUsp2a adenovirus-treated samples (Fig. 6, C and D, right panel). To further assess the impact of USP2a on the molecular clock behavior, we switched to the established U2OS stable cell line that displays robust oscillations of the Bmal1 promoter-driven luciferase activity monitored by real time bioluminescence for days after synchronization (20, 21). Compared with shCon, knockdown of Usp2a led to higher amplitude of the Bmal1-luc oscillations (Fig. 6C). However, depletion of Usp2a did not cause either phase shift or change of period length in the Bmal1-luc activity.

FIGURE 6.

USP2a regulates the CRY1-mediated circadian function. A, Per2-luc activity is inhibited by overexpression of Usp2a but reversed by Cry1 knockdown in Hepa-1 cells. Hepa-1 cells were transduced by either shLacZ or shCry1 adenovirus after co-transfection with the Per2-luc reporter vector and Usp2a expression vector. The luciferase activities were measured and calculated 72 h after transduction. The data were plotted as means ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p value < 0.05; **, p value < 0.01 by Student's t test. B, effects of USP2a-290CA on the Per2-luc activity. The luciferase activity was measured and calculated 72 h after transfection. The data were plotted as means ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p value < 0.05 by Student's t test. C, effect of Usp2a knockdown on the circadian oscillations of the Per2 mRNA in synchronized Hepa-1 cells. Hepa-1 cells were synchronized with serum shock after transduction with either Ad-shLacZ or Ad-shUsp2a. The mRNA levels of endogenous Per2 at indicated time points were measured by Q-PCR. The data were plotted as means ± S.D. (n = 3). The area under the curve analysis for Per2 mRNA oscillation was presented as well. *, p value < 0.05 by Student's t test. D, effect of Usp2a knockdown on circadian oscillations of the Bmal1 mRNA in synchronized Hepa-1 cells. The data were plotted as means ± S.D. (n = 3). The area under the curve analysis for Bmal1 mRNA oscillations was presented as well. *, p value < 0.05 by Student's t test. E, effect of Usp2a knockdown on period and amplitude of the Bmal1-luciferase in U2OS cells. Manipulation of the USP2a protein level was achieved by transfection with shUsp2a vectors (a mixture of equal amount of shUsp2a-1 and shUsp2a-2) before synchronization by dexamethasone and forskolin. A representative of three replicates is shown in the bioluminescence graphs. Amplitude and period lengths of three replicates are shown as means ± S.D. for each treatment. **, p value < 0.01 was determined by Student's t test. Con, control.

For measuring gain-of-function of Usp2a on the Bmal1-luc activity, we observed that only overexpression of Usp2a-WT but not Usp2a-290CA mutant reduced the Bmal1-luc activity in a transient transfection assay (supplemental Fig. 9A). Moreover, overexpression of Usp2a-WT caused a modest but significant reduction in the amplitude of the reporter activity compared with GFP control (supplemental Fig. 9B), similar to an observation upon CRY1 overexpression in NIH3T3 cells (60). Either overexpression or knockdown of Usp2a did not seem to affect the period length of the Bmal1-luc reporter activity, consistent with the phenotype of Usp2 null mice (47). Taken together, our data suggest that manipulation of USP2a mainly alters the amplitude of molecular clock oscillations in the synchronized cells.

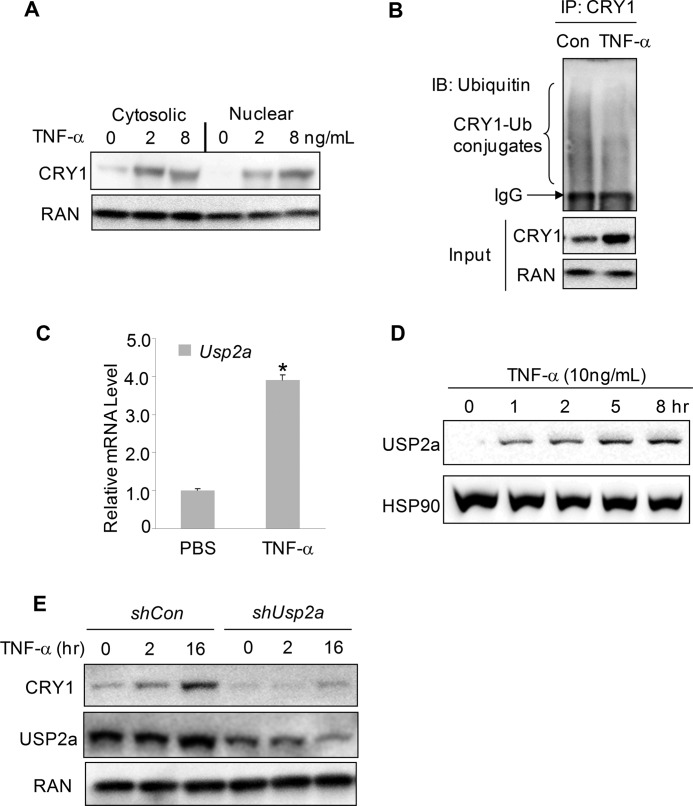

TNF-α Induces USP2a to Stabilize the CRY1 Protein

There is growing evidence for the intimate connection between inflammation response and the molecular clock (61, 62). The functional circadian clock systems are detected in major immune cells, including macrophages (63), B cells (64, 65), and natural killer cells (66–68). It has been reported that circadian clock disruption via the shifted light/dark cycle or genetic deletion of clock genes impairs innate immunity and response to LPS treatment in mice (22, 61, 63). Conversely, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β suppress the expression of several major clock genes in NIH3T3 cells (69, 70). We also found that TNF-α treatment led to a down-regulation of the circadian output gene DBP and suppressed the Per2 promoter-driven luciferase reporter activation by BMAL1/CLOCK overexpression in human hepatoma Huh7 cell line (supplemental Fig. 10, A and B). To determine whether TNF-α can directly target core clock proteins and in turn affect clock gene expression, we treated Huh7 cells with increasing doses of TNF-α overnight and observed a dose-dependent increase of the CRY1 protein (Fig. 7A). Similar induction of the CRY1 protein was observed in another human hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cell line after TNF-α overnight treatment (supplemental Fig. 10C). Of note, the TNF-α effect was more potent when cells were incubated in a low glucose condition versus a high glucose condition (data not shown). TNF-α treatment had no effect on the REV-ERBα protein level, indicating its induction on CRY1 is relatively specific (supplemental Fig. 9D). Furthermore, the ubiquitination status of CRY1 was reduced upon TNF-α treatment, reminiscent of serum shock treatment (Fig. 7B). In the meantime, we found that TNF-α treatment potently induced both the mRNA and protein expression of USP2a (Fig. 7, C and D), suggesting that TNF-α may utilize USP2a to control the CRY1 protein turnover. To confirm whether USP2a indeed mediates the TNF-α effect on the CRY1 stability, we depleted Usp2a with an shRNA vector and then stimulated cells with TNF-α after verifying the knockdown efficiency by RT-Q-PCR (supplemental Fig. 10E). In this condition, TNF-α was no longer able to increase the level of the CRY1 protein (Fig. 7E), indicating that USP2a is indeed required for the TNF-α-induced stabilization of the CRY1 protein. These data indicate that chronic TNF-α treatment suppresses the circadian clock by stabilizing the CRY1 protein through USP2a.

FIGURE 7.

TNF-α stabilizes CRY1 protein through USP2 induction. A, CRY1 protein in human hepatocarcinoma Huh7 cells treated with increasing doses of TNF-α. The protein lysates were harvested 16 h after TNF-α treatment. The CRY1 protein in both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions was measured by immunoblotting (IB). B, ubiquitination of the endogenous CRY1 was examined in Huh7 cells treated with TNF-α. After 16 h treatment of TNF-α, protein lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-CRY1. The ubiquitin-CRY1 conjugates were detected by anti-ubiquitin (Ub). C, TNF-α treatment induces the mRNA level of Usp2a in Huh7 cells. Huh7 cells were treated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 16 h before harvesting for Q-PCR. The data were plotted as means ± S.D. of four replicates. *, p value < 0.05 was calculated by Students' t test. D, dose-dependent induction of the Usp2a protein by TNF-α in Huh7 cells. Huh7 cells were treated with increasing doses of TNF-α for 6 h before harvesting for immunoblotting with anti-USP2a. E, effect of USP2a depletion on TNF-α-induced CRY1 protein stabilization. Huh7 cells were first transfected with either control or shUSP2a vector (a mixture of equal amounts of shUsp2a-1 and shUsp2a-2). 48 h later, cells were treated with a 2-h serum shock and switched to serum-free medium. TNF-α was then added before the protein lysates were harvested at indicated time points and examined for the CRY1, USP2a, and RAN protein levels. The mRNA levels of Usp2a after transfection were also determined by Q-PCR (shown in supplemental Fig. 9E).

DISCUSSION

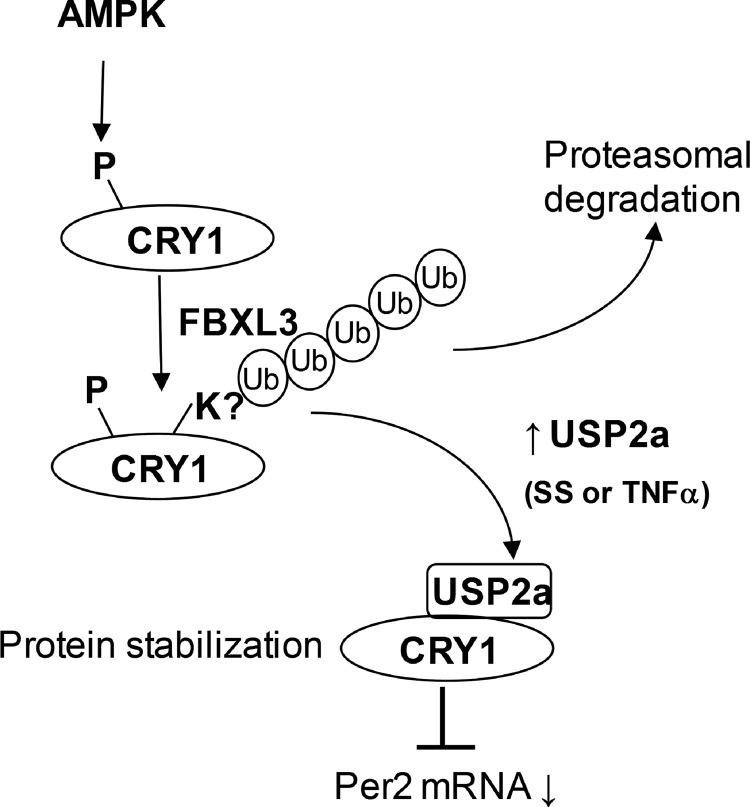

The importance of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in circadian rhythms has been demonstrated via identification of critical ubiquitin E3 ligase for individual core clock proteins (71). Like other post-translational modifications, ubiquitination is a reversible process catalyzed by both E3 ligases and deubiquitination enzymes. Thus, it is conceivable that deubiquitination enzymes are an essential part of the circadian network to fine-tune circadian rhythms in response to environmental cues. Here, we reported that serum shock potently induces the CRY1 protein by inhibiting CRY1 ubiquitination in a variety of cells. We identified USP2a as the critical DUB enzyme for deubiquitinating the CRY1 protein upon serum shock. Depletion of USP2a not only down-regulates the CRY1 protein level but also alters the CRY1-dependent circadian function. We also generated strong evidence showing that USP2a regulates CRY1 ubiquitination and protein stability in vivo and in vitro. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing in vivo and in vitro ubiquitination of the CRY1 protein. Most interestingly, Usp2a mRNA is up-regulated by the pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, and this induction accounts for the CRY1 protein stabilization after TNF-α stimulation. Therefore, we uncovered a critical link for direct regulation of the circadian clock in inflammatory conditions (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Working model. The CRY1 protein stability is under dynamic control by both ubiquitination and deubiquitination. After AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent phosphorylation, CRY1 will be polyubiquitinated by FBXL3 E3 ligase for proteasomal degradation. Ubiquitinated CRY1 protein becomes a suitable substrate for the deubiquitinating enzyme USP2a, which can be induced by a pulse of serum shock or the inflammatory cytokine TNF-α. CRY1 regulation by TNF-α may be important for the cross-talk between inflammatory response and the molecular clock.

Liver CRY1 proteins show a clear pattern of circadian oscillations (10, 11, 16). The CRY1 protein rhythmicity was disturbed in Fbxl3 mutant mice (16) and Lkb1 knock-out mice (15). In the case of Fbxl3 mutant mice, a delayed CRY1 protein degradation results in a significantly longer circadian period. In the liver of Lkb1 null mice, the defect in CRY1 degradation leads to a severely dampened oscillation of Dbp and Per2 genes (15). Our finding points out a reversible regulation of the CRY1 protein turnover by demonstrating USP2a as a stabilizing factor for this critical clock component. The Fbxl3 mRNA expression remains at a constant level during a circadian cycle (16), whereas the Usp2a mRNA displays a robust circadian oscillation (45). The abundance of USP2a may become a rate-limiting factor to determine the fate of ubiquitinated CRY1 protein during a given circadian cycle. When the cellular USP2a level is low, the ubiquitinated CRY1 protein will undergo proteasome-dependent degradation. However, in the presence of elevated levels of USP2a, the CRY1 protein remains stable despite being modified by ubiquitination. We propose that the CRY1 protein cycling is a function of dynamic balance between FBXL3-mediated ubiquitination and USP2-dependent deubiquitination. Future work will study the cross-talk between USP2a and FBXL3 in regulating the circadian oscillation of CRY1 protein.

Our data show that USP2a affects the molecular clock gene and protein oscillations by stabilizing a core clock protein in the negative feedback loop. Our data support the network features of the molecular clock system (4) in which the clock utilizes active compensatory mechanisms to confer robustness and maintain proper functions. Knockdown of Usp2a leads to lower levels of CRY1 protein throughout the entire circadian cycle. This circadian impact is further amplified by the effect of CRY1 on PER1, REV-ERBα, and even BMAL1 proteins. Our current observation establishes the role of USP2a as a stabilizer of the main negative feedback loop. A recent publication has reported that Usp2 knock-out mice preserve rhythmicity during dark/dark conditions but display increased phase delay upon low lighting exposure (47). Those Usp2 knock-out mice share a similar phenotype with Rev-erbα knock-out mice, which show inaccurate phase response to light due to the impaired negative feedback loop (72). Although the Usp2 knock-out study does show that USP2 forms a complex with clock proteins, including BMAL1 and CRY1 in the suprachiasmatic nucleus extracts, it focuses on the regulation of deubiquitination and stability of BMAL1 other than CRY1 protein by USP2b (the 45-kDa isoform) in 293 and NIH3T3 cells. Another recent study reveals that CRY1 protein undergoes a conformational change to transduce the blue light signal, to which animals are most sensitive to in a low lighting setting (73). Based upon that observation, our data provide another intriguing possibility that USP2a-dependent stabilization of CRY1 may also be responsible for the delayed phase observed in Usp2 knock-out mice. We speculate that CRY1 may be an alternative target of USP2 to reset the clock in response to changes of lighting. It will be of great interest to investigate the substrate specificity of each USP2 isoform in various tissues and to determine their differential contribution to the circadian clock in a tissue-specific manner.

A major finding in this study is that TNF-α can potently promote deubiquitination and subsequent stabilization of the CRY1 protein. This action is likely mediated by an increased expression of USP2a upon TNF-α treatment. Throughout the literature, TNF-α, IL-1β, and adiponectin have been reported to differentially regulate USP2a (39–41). A recent publication has demonstrated that USP2a functions as a critical downstream mediator of the TNFα-induced NF-κB signaling in tumor cells (74). Because both mRNA and protein levels of USP2a are induced by TNF-α treatment, it suggests that both transcriptional and post-translational regulation might be required for a robust USP2a induction, possibly via the NF-κB pathway. How TNF-α activates Usp2a gene expression has not been fully addressed in our study. The biological significance of the CRY1 protein stabilization upon chronic TNF-α treatment may imply that CRY1 is indeed required for TNF-α action on the clock gene expression. It has been reported that TNF-α treatment suppresses clock gene expression in NIH3T3 fibroblasts by interfering with the E-box-mediated transcription (69), although the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Our findings provide a possible molecular mechanism for this TNF-α-induced suppression of clock functions. It has been reported that obesity and high fat diet dampen the molecular clock in the liver. Both conditions are associated with a chronic state of low grade inflammation. It is tantalizing to hypothesize that the TNF-α-induced CRY1 stabilization may also contribute to the dampened clock function during the course of obesity (75–77), a possibility that will be explored in future studies. The CRY1 protein may be involved in a feedback regulation of the TNF-α signaling pathway. In Cry1/2 double null mice, the circulating TNF-α level is significantly increased, suggesting an anti-inflammatory role of CRY1 and CRY2 proteins through down-regulating TNF-α (22). Therefore, CRY1 may function in the negative feedback loop to tune down prolonged inflammatory response. Because this study is focused on hepatocytes, which are not ideal for studying cytokine production, it will be of a great interest to test whether the TNF-α/USP2a/CRY1 axis functions in macrophages and other immune cells.

In summary, we have identified a novel regulatory mechanism for controlling the CRY1 protein stability in the context of the circadian network. Our work highlighted the importance of the deubiquitinating enzyme USP2a in regulation of CRY1 protein stability and consequently circadian output gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Our results support the notion that USP2a functions to connect chronic inflammation to circadian disturbances. Because both inflammation and the circadian clock are important regulators of metabolism, a better understanding of the role of USP2a in the regulation of CRY1 protein might shed light on interplays between inflammatory response and the circadian clock. Thus, USP2a holds great promise as a pharmaceutical target for treating circadian and metabolic disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Hogenesch (University of Pennsylvania) for providing the plasmids for Per2-luc and pCMV-mCry1-FLAG and the U2OS Bmal1-luc stable cell line. We thank Dr. Ormond MacDougald (University of Michigan) for providing the circadian mouse liver samples. We also thank Dr. Liangyou Rui (University of Michigan) for helpful discussions. We greatly appreciate Dr. Qiang Zhang (Hamner Institute for Health Sciences) for help with manuscript preparation.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant K99/R00 DK077449 (to L. Y.). This work was also supported by Pilot Grant 5P3ODKO34933 (to L. Y.) from Michigan Gastrointestinal Hormone Research Core Center and Pilot Grant P60DK020572 from University of Michigan Diabetes and Research Training Center.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S10.

- DUB

- deubiquitinating enzyme

- Q-PCR

- quantitative PCR

- CHX

- cycloheximide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bass J., Takahashi J. S. (2010) Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science 330, 1349–1354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Green C. B., Takahashi J. S., Bass J. (2008) The meter of metabolism. Cell 134, 728–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takahashi J. S., Hong H. K., Ko C. H., McDearmon E. L. (2008) The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder. Implications for physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 764–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baggs J. E., Hogenesch J. B. (2010) Genomics and systems approaches in the mammalian circadian clock. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 20, 581–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dibner C., Schibler U., Albrecht U. (2010) The mammalian circadian timing system. Organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72, 517–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paschos G. K., Baggs J. E., Hogenesch J. B., FitzGerald G. A. (2010) The role of clock genes in pharmacology. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 50, 187–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reppert S. M., Weaver D. R. (2001) Molecular analysis of mammalian circadian rhythms. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 63, 647–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yin L., Joshi S., Wu N., Tong X., Lazar M. A. (2010) E3 ligases Arf-bp1 and Pam mediate lithium-stimulated degradation of the circadian heme receptor Rev-erb α. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11614–11619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang E. E., Liu A. C., Hirota T., Miraglia L. J., Welch G., Pongsawakul P. Y., Liu X., Atwood A., Huss J. W., 3rd, Janes J., Su A. I., Hogenesch J. B., Kay S. A. (2009) A genome-wide RNAi screen for modifiers of the circadian clock in human cells. Cell 139, 199–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Asher G., Gatfield D., Stratmann M., Reinke H., Dibner C., Kreppel F., Mostoslavsky R., Alt F. W., Schibler U. (2008) SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation. Cell 134, 317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Asher G., Reinke H., Altmeyer M., Gutierrez-Arcelus M., Hottiger M. O., Schibler U. (2010) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 participates in the phase entrainment of circadian clocks to feeding. Cell 142, 943–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee C., Etchegaray J. P., Cagampang F. R., Loudon A. S., Reppert S. M. (2001) Post-translational mechanisms regulate the mammalian circadian clock. Cell 107, 855–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Busino L., Bassermann F., Maiolica A., Lee C., Nolan P. M., Godinho S. I., Draetta G. F., Pagano M. (2007) SCFFbxl3 controls the oscillation of the circadian clock by directing the degradation of cryptochrome proteins. Science 316, 900–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Godinho S. I., Maywood E. S., Shaw L., Tucci V., Barnard A. R., Busino L., Pagano M., Kendall R., Quwailid M. M., Romero M. R., O'neill J., Chesham J. E., Brooker D., Lalanne Z., Hastings M. H., Nolan P. M. (2007) The after-hours mutant reveals a role for Fbxl3 in determining mammalian circadian period. Science 316, 897–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lamia K. A., Sachdeva U. M., DiTacchio L., Williams E. C., Alvarez J. G., Egan D. F., Vasquez D. S., Juguilon H., Panda S., Shaw R. J., Thompson C. B., Evans R. M. (2009) AMPK regulates the circadian clock by cryptochrome phosphorylation and degradation. Science 326, 437–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Siepka S. M., Yoo S. H., Park J., Song W., Kumar V., Hu Y., Lee C., Takahashi J. S. (2007) Circadian mutant Overtime reveals F-box protein FBXL3 regulation of cryptochrome and period gene expression. Cell 129, 1011–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harada Y., Sakai M., Kurabayashi N., Hirota T., Fukada Y. (2005) Ser-557-phosphorylated mCRY2 is degraded upon synergistic phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase-3β. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31714–31721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kurabayashi N., Hirota T., Sakai M., Sanada K., Fukada Y. (2010) DYRK1A and glycogen synthase kinase 3β, a dual-kinase mechanism directing proteasomal degradation of CRY2 for circadian timekeeping. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1757–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Horst G. T., Muijtjens M., Kobayashi K., Takano R., Kanno S., Takao M., de Wit J., Verkerk A., Eker A. P., van Leenen D., Buijs R., Bootsma D., Hoeijmakers J. H., Yasui A. (1999) Mammalian Cry1 and Cry2 are essential for maintenance of circadian rhythms. Nature 398, 627–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baggs J. E., Price T. S., DiTacchio L., Panda S., Fitzgerald G. A., Hogenesch J. B. (2009) Network features of the mammalian circadian clock. PLoS Biol. 7, e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vollmers C., Panda S., DiTacchio L. (2008) A high-throughput assay for siRNA-based circadian screens in human U2OS cells. PLoS One 3, e3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hashiramoto A., Yamane T., Tsumiyama K., Yoshida K., Komai K., Yamada H., Yamazaki F., Doi M., Okamura H., Shiozawa S. (2010) Mammalian clock gene Cryptochrome regulates arthritis via proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α. J. Immunol. 184, 1560–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang E. E., Liu Y., Dentin R., Pongsawakul P. Y., Liu A. C., Hirota T., Nusinow D. A., Sun X., Landais S., Kodama Y., Brenner D. A., Montminy M., Kay S. A. (2010) Cryptochrome mediates circadian regulation of cAMP signaling and hepatic gluconeogenesis. Nat. Med. 16, 1152–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Doi M., Takahashi Y., Komatsu R., Yamazaki F., Yamada H., Haraguchi S., Emoto N., Okuno Y., Tsujimoto G., Kanematsu A., Ogawa O., Todo T., Tsutsui K., van der Horst G. T., Okamura H. (2010) Salt-sensitive hypertension in circadian clock-deficient Cry-null mice involves dysregulated adrenal Hsd3b6. Nat. Med. 16, 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Katz E. J., Isasa M., Crosas B. (2010) A new map to understand deubiquitination. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 21–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reyes-Turcu F. E., Ventii K. H., Wilkinson K. D. (2009) Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 363–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sowa M. E., Bennett E. J., Gygi S. P., Harper J. W. (2009) Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell 138, 389–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sheng Y., Saridakis V., Sarkari F., Duan S., Wu T., Arrowsmith C. H., Frappier L. (2006) Molecular recognition of p53 and MDM2 by USP7/HAUSP. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 285–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van der Horst A., de Vries-Smits A. M., Brenkman A. B., van Triest M. H., van den Broek N., Colland F., Maurice M. M., Burgering B. M. (2006) FOXO4 transcriptional activity is regulated by monoubiquitination and USP7/HAUSP. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1064–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mukai A., Yamamoto-Hino M., Awano W., Watanabe W., Komada M., Goto S. (2010) Balanced ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation of Frizzled regulate cellular responsiveness to Wg/Wnt. EMBO J. 29, 2114–2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ramakrishna S., Suresh B., Baek K. H. (2011) The role of deubiquitinating enzymes in apoptosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68, 15–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tauriello D. V., Haegebarth A., Kuper I., Edelmann M. J., Henraat M., Canninga-van Dijk M. R., Kessler B. M., Clevers H., Maurice M. M. (2010) Loss of the tumor suppressor CYLD enhances Wnt/β-catenin signaling through K63-linked ubiquitination of Dvl. Mol. Cell 37, 607–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhao B., Schlesiger C., Masucci M. G., Lindsten K. (2009) The ubiquitin-specific protease 4 (USP4) is a new player in the Wnt signaling pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13, 1886–1895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stevenson L. F., Sparks A., Allende-Vega N., Xirodimas D. P., Lane D. P., Saville M. K. (2007) The deubiquitinating enzyme USP2a regulates the p53 pathway by targeting Mdm2. EMBO J. 26, 976–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Graner E., Tang D., Rossi S., Baron A., Migita T., Weinstein L. J., Lechpammer M., Huesken D., Zimmermann J., Signoretti S., Loda M. (2004) The isopeptidase USP2a regulates the stability of fatty acid synthase in prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 5, 253–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shan J., Zhao W., Gu W. (2009) Suppression of cancer cell growth by promoting cyclin D1 degradation. Mol. Cell 36, 469–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Allende-Vega N., Sparks A., Lane D. P., Saville M. K. (2010) MdmX is a substrate for the deubiquitinating enzyme USP2a. Oncogene 29, 432–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gousseva N., Baker R. T. (2003) Gene structure, alternate splicing, tissue distribution, cellular localization, and developmental expression pattern of mouse deubiquitinating enzyme isoforms Usp2–45 and Usp2–69. Gene Expr. 11, 163–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang S., Wu H., Liu Y., Sun J., Zhao Z., Chen Q., Guo M., Ma D., Zhang Z. (2010) Expression of USP2–69 in mesangial cells in vivo and in vitro. Pathol. Int. 60, 184–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Haimerl F., Erhardt A., Sass G., Tiegs G. (2009) Down-regulation of the deubiquitinating enzyme ubiquitin-specific protease 2 contributes to tumor necrosis factor-α-induced hepatocyte survival. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 495–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Treeck O., Lattrich C., Juhasz-Boess I., Buchholz S., Pfeiler G., Ortmann O. (2008) Adiponectin differentially affects gene expression in human mammary epithelial and breast cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 99, 1246–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sacco J. J., Coulson J. M., Clague M. J., Urbé S. (2010) Emerging roles of deubiquitinases in cancer-associated pathways. IUBMB Life 62, 140–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Priolo C., Tang D., Brahamandan M., Benassi B., Sicinska E., Ogino S., Farsetti A., Porrello A., Finn S., Zimmermann J., Febbo P., Loda M. (2006) The isopeptidase USP2a protects human prostate cancer from apoptosis. Cancer Res. 66, 8625–8632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang Y., Hou J. Q., Qu L. Y., Wang G. Q., Ju H. W., Zhao Z. W., Yu Z. H., Yang H. J. (2007) Differential expression of USP2, USP14, and UBE4A between ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma and adjacent normal tissues]. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi 23, 504–506 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oishi K., Amagai N., Shirai H., Kadota K., Ohkura N., Ishida N. (2005) Genome-wide expression analysis reveals 100 adrenal gland-dependent circadian genes in the mouse liver. DNA Res. 12, 191–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Oishi K., Miyazaki K., Kadota K., Kikuno R., Nagase T., Atsumi G., Ohkura N., Azama T., Mesaki M., Yukimasa S., Kobayashi H., Iitaka C., Umehara T., Horikoshi M., Kudo T., Shimizu Y., Yano M., Monden M., Machida K., Matsuda J., Horie S., Todo T., Ishida N. (2003) Genome-wide expression analysis of mouse liver reveals CLOCK-regulated circadian output genes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41519–41527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scoma H. D., Humby M., Yadav G., Zhang Q., Fogerty J., Besharse J. C. (2011) The deubiquitinylating enzyme, USP2, is associated with the circadian clockwork and regulates its sensitivity to light. PLoS One 6, e25382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Balsalobre A., Damiola F., Schibler U. (1998) A serum shock induces circadian gene expression in mammalian tissue culture cells. Cell 93, 929–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tamanini F. (2007) Manipulation of mammalian cell lines for circadian studies. Methods Mol. Biol. 362, 443–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yin L., Wang J., Klein P. S., Lazar M. A. (2006) Nuclear receptor Rev-erbα is a critical lithium-sensitive component of the circadian clock. Science 311, 1002–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ruffieux-Daidié D., Poirot O., Boulkroun S., Verrey F., Kellenberger S., Staub O. (2008) Deubiquitylation regulates activation and proteolytic cleavage of ENaC. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 2170–2180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shi Y., Solomon L. R., Pereda-Lopez A., Giranda V. L., Luo Y., Johnson E. F., Shoemaker A. R., Leverson J., Liu X. (2011) Ubiquitin-specific cysteine protease 2a (USP2a) regulates the stability of Aurora-A. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 38960–38968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mahul-Mellier A. L., Pazarentzos E., Datler C., Iwasawa R., AbuAli G., Lin B., Grimm S. (2012) Deubiquitinating protease USP2a targets RIP1 and TRAF2 to mediate cell death by TNF. Cell Death Differ. 19, 891–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Eide E. J., Woolf M. F., Kang H., Woolf P., Hurst W., Camacho F., Vielhaber E. L., Giovanni A., Virshup D. M. (2005) Control of mammalian circadian rhythm by CKIϵ-regulated proteasome-mediated PER2 degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 2795–2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sahar S., Zocchi L., Kinoshita C., Borrelli E., Sassone-Corsi P. (2010) Regulation of BMAL1 protein stability and circadian function by GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation. PLoS One 5, e8561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shirogane T., Jin J., Ang X. L., Harper J. W. (2005) SCFβ-TRCP controls clock-dependent transcription via casein kinase 1-dependent degradation of the mammalian period-1 (Per1) protein. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26863–26872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shearman L. P., Zylka M. J., Weaver D. R., Kolakowski L. F., Jr., Reppert S. M. (1997) Two period homologs. Circadian expression and photic regulation in the suprachiasmatic nuclei. Neuron 19, 1261–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yagita K., Tamanini F., Yasuda M., Hoeijmakers J. H., van der Horst G. T., Okamura H. (2002) Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and mCRY-dependent inhibition of ubiquitylation of the mPER2 clock protein. EMBO J. 21, 1301–1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vitaterna M. H., Selby C. P., Todo T., Niwa H., Thompson C., Fruechte E. M., Hitomi K., Thresher R. J., Ishikawa T., Miyazaki J., Takahashi J. S., Sancar A. (1999) Differential regulation of mammalian period genes and circadian rhythmicity by cryptochromes 1 and 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 12114–12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chaves I., Nijman R. M., Biernat M. A., Bajek M. I., Brand K., da Silva A. C., Saito S., Yagita K., Eker A. P., van der Horst G. T. (2011) The Potorous CPD photolyase rescues a cryptochrome-deficient mammalian circadian clock. PLoS One 6, e23447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Castanon-Cervantes O., Wu M., Ehlen J. C., Paul K., Gamble K. L., Johnson R. L., Besing R. C., Menaker M., Gewirtz A. T., Davidson A. J. (2010) Dysregulation of inflammatory responses by chronic circadian disruption. J. Immunol. 185, 5796–5805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cutolo M., Straub R. H. (2008) Circadian rhythms in arthritis. Hormonal effects on the immune/inflammatory reaction. Autoimmun. Rev. 7, 223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Keller M., Mazuch J., Abraham U., Eom G. D., Herzog E. D., Volk H. D., Kramer A., Maier B. (2009) A circadian clock in macrophages controls inflammatory immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21407–21412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sun Y., Yang Z., Niu Z., Peng J., Li Q., Xiong W., Langnas A. N., Ma M. Y., Zhao Y. (2006) MOP3, a component of the molecular clock, regulates the development of B cells. Immunology 119, 451–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sun Y., Yang Z., Niu Z., Wang W., Peng J., Li Q., Ma M. Y., Zhao Y. (2006) The mortality of MOP3-deficient mice with a systemic functional failure. J. Biomed. Sci. 13, 845–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Arjona A., Boyadjieva N., Sarkar D. K. (2004) Circadian rhythms of granzyme B, perforin, IFN-γ and NK cell cytolytic activity in the spleen. Effects of chronic ethanol. J. Immunol. 172, 2811–2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Arjona A., Sarkar D. K. (2005) Circadian oscillations of clock genes, cytolytic factors, and cytokines in rat NK cells. J. Immunol. 174, 7618–7624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Arjona A., Sarkar D. K. (2006) Evidence supporting a circadian control of natural killer cell function. Brain Behav. Immun. 20, 469–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cavadini G., Petrzilka S., Kohler P., Jud C., Tobler I., Birchler T., Fontana A. (2007) TNF-α suppresses the expression of clock genes by interfering with E-box-mediated transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12843–12848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Petrzilka S., Taraborrelli C., Cavadini G., Fontana A., Birchler T. (2009) Clock gene modulation by TNF-α depends on calcium and p38 MAP kinase signaling. J. Biol. Rhythms 24, 283–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gallego M., Virshup D. M. (2007) Post-translational modifications regulate the ticking of the circadian clock. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Preitner N., Damiola F., Lopez-Molina L., Zakany J., Duboule D., Albrecht U., Schibler U. (2002) The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBα controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell 110, 251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ozturk N., Selby C. P., Annayev Y., Zhong D., Sancar A. (2011) Reaction mechanism of Drosophila cryptochrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 516–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Metzig M., Nickles D., Falschlehner C., Lehmann-Koch J., Straub B. K., Roth W., Boutros M. (2011) An RNAi screen identifies USP2 as a factor required for TNF-α-induced NF-κB signaling. Int. J. Cancer 129, 607–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ando H., Kumazaki M., Motosugi Y., Ushijima K., Maekawa T., Ishikawa E., Fujimura A. (2011) Impairment of peripheral circadian clocks precedes metabolic abnormalities in ob/ob mice. Endocrinology 152, 1347–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kaneko K., Yamada T., Tsukita S., Takahashi K., Ishigaki Y., Oka Y., Katagiri H. (2009) Obesity alters circadian expressions of molecular clock genes in the brainstem. Brain Res. 1263, 58–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kohsaka A., Laposky A. D., Ramsey K. M., Estrada C., Joshu C., Kobayashi Y., Turek F. W., Bass J. (2007) High-fat diet disrupts behavioral and molecular circadian rhythms in mice. Cell Metab. 6, 414–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.