Recent data indicate that stem cells exist in many tissues, including skeletal muscle, liver, and the central nervous system, some of them not known classically as having stem cells. The unexpected plasticity and the tremendous disease implications of these findings have created a lot of excitement (1, 2). However, a major obstacle in these areas has been a lack of molecular markers and of the precise in vivo localization of the putative stem cells. Because epidermis is an excellent example of a self-renewing tissue containing stem cells, it is of interest to examine the current status of this field. Like stem cells of other tissues, epidermal stem cells are important because they not only play a central role in homeostasis and wound repair, but also represent a major target of tumor initiation and gene therapy.

Perhaps the most universally accepted criteria for keratinocyte stem cells are that they are normally slow-cycling (or, perhaps more accurately, rarely cycling) in vivo; that they can self-renew and are responsible for the long-term maintenance of the tissue; that they can be activated by wounding or by in vitro culture conditions to proliferate and to regenerate the tissue; and that they have a high proliferative potential (3–6). The slow-cycling attribute is particularly important biologically because it conserves the cell's proliferative potential and minimizes DNA replication-related errors. The rare divisions of stem cells give rise to, on average, one stem cell and one transit amplifying (TA) cell, which has a limited proliferative potential. On the exhaustion of their proliferative potential, the rapidly proliferating TA cells undergo terminal differentiation.

The slow-cycling stem cells can be identified experimentally as the “label-retaining cells” (LRCs) (7). This is done by long-term labeling of all of the cells with a DNA precursor such as [3H]thymidine or bromodeoxyuridine (BrdUrd), followed by a chase period that results in the dilution of the label from all of the rapidly cycling TA cells, but not from the slow-cycling stem cells (7, 8). Using this approach, two groups recently discovered that the label-retaining, presumptive keratinocyte stem cells of hairy mouse skin are located predominantly in the upper hair follicle in an area called the “bulge” (Fig. 1), with very few in the surface epidermis (9, 10). This unexpected finding raised the possibility that the ultimate epidermal stem cells may actually reside outside of the epidermis in an epidermal appendage, tucked away deeply into the skin in an area well protected from environmental damage. A paper in a recent issue of PNAS has shown that these slow-cycling bulge cells can be isolated in a viable form by cell sorting (11). Thus, Tani et al. isolated mouse keratinocytes that are integrin α6-positive and transferrin receptor-negative (α6briCD71dim), and showed that this cell fraction is enriched in label-retaining (stem) cells and has an enhanced in vitro proliferative potential. In contrast, another fraction consisting of α6briCD71bri cells is enriched in the dividing TA cells (11). By providing the first evidence linking specific cell surface markers with both in vitro growth potential and a well-accepted in vivo cell kinetic criterion for keratinocyte stem cells, this work represents an important advance in isolating epidermal stem cells. The data also demand a reexamination of the meaning of these follicular label-retaining cells: are these cells the ultimate stem cells of the epidermis?

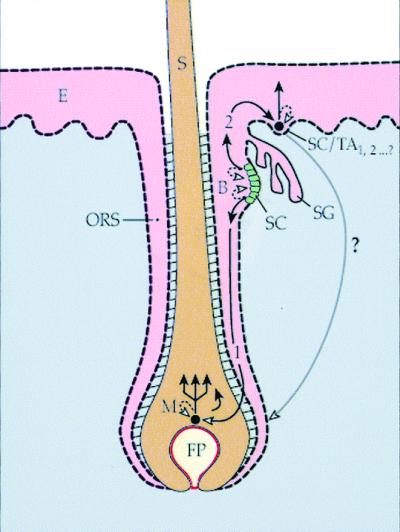

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of an epidermo-pilosebaceous unit in hair-bearing skin. The unit consists of the epidermis and the hair follicle with its associated sebaceous gland. The bulge contains a population of putative keratinocyte stem cells that can give rise to (pathway 1) a population of pluripotent and rapidly dividing progenitor (transit amplifying) cells in the matrix that yields the hair shaft. Alternatively, the bulge stem cells can give rise to the stem/progenitor cells of the epidermis (pathway 2). It is hypothesized here that the epidermal stem cell represents a form of bulge-derived, young transit amplifying cell (SC/TA1,2… ?). The long, curved arrow denotes the demonstrated capability of adult epidermal cells to form a new hair follicle in response to appropriate mesenchymal stimuli (46, 47). B, bulge; E, epidermis; FP, follicular or dermal papilla; M, matrix keratinocytes; ORS, outer root sheath; S, hair shaft; SC, stem cells; SG, sebaceous gland; TA, transit amplifying cells.

Properties of Keratinocyte Stem Cells: The Eye Shows the Way

A tissue that has yielded a tremendous wealth of information about keratinocyte stem cells is the corneal epithelium. The stem cells of corneal epithelium are located in peripheral cornea in a rim called the limbus (12, 13). Thus, in this system, the limbal stem cells can be millimeters away from their central corneal progeny TA cells. As shown in Table 1, limbal (basal) epithelial stem cells are slow-cycling; have a high in vitro proliferative potential; lack the corneal epithelial differentiation-associated keratin K3; are in association with a loose and well-vascularized stroma; are sequestered in the highly undulating Palisades of Vogt (human); are protected from solar damage by melanocytes; undergo centripetal migration; and represent the predominant site of corneal tumor formation. In sharp contrast, the (progeny) corneal epithelium is devoid of label-retaining cells; has a low in vitro proliferative capacity; expresses the K3 keratin even in its basal cells; overlies an avascular and highly organized corneal stroma; is highly susceptible to mechanical debridement by virtue of its smooth epithelial/stromal interface; lacks pigment protection; and almost never gives rise to tumors (reviewed in refs. 14–16). Moreover, limbal cells are essential for the long-term maintenance of the central corneal epithelium and can be used to reconstitute the entire corneal epithelium in patients with limbal stem cell deficiencies (reviewed in refs. 17 and 18). Collectively, these data leave no doubt that corneal epithelial stem cells reside in the limbus and provide a set of well-defined keratinocyte stem cell properties that can aid in the identification of stem cells in other stratified epithelia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Properties of keratinocyte stem cells

| Property | Assay or experimental identification | Cornea

|

Skin

|

Palm

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limbus | Central cornea | Hair bulge | Epidermis

|

Deep rete ridge | Shallow rete ridge | ||||

| Bottom | Top | EPU | |||||||

| Slow-Cycling | Label-retaining cells | +++ | − | +++ | +/− | +/− | + | + Next to TA cells | ? |

| High proliferative potential | In vitro expansion and passage | +++ | − | +++ | ? | +, ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Relatively undifferentiated phenotype | Lacking differentiation related keratins or other markers | ++++ | − | +++ | ++ | − | ? | ++ Nonserrated | −Serrated |

| Specialized stromal niche | A cluster of LRCs in contact with a specialized mesenchyme | +++ L/V | − T/N | +++ arrector pili muscle | + L/V | − | − | ++ L/V | − |

| Physical protection | Usually located in a well-protected environment | ++ Palisade of Vogt | − Smooth surface | ++++ | ++ | − | − | +++ | − |

| Pigment protection in exposed area | Melanin enrichment | +++ | − | N/A | ++ | +/− | N/A | +++ | + |

| Origin of tumor | Predominant site of tumor formation | ++++ | − | ++ | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

The number of plus (+) signs reflects the strength of the available data. Negative (−) sign indicates contradictory or inconsistent data. Question (?) mark indicates no available data. N/A, not applicable; L/V, loose and vascularized; T/N, tight and nonvascularized.

Site of Epidermal Stem Cells: An Unsettled Issue

It is surprising that, when these criteria are applied to the epidermis, one cannot find cells that fit many of these criteria (Table 1). Like the palm/sole epithelial stem cells located at the bottom of the deep rete ridges (4), keratinocytes at the bottom of the (interfollicular) epidermal rete ridges enjoy good physical protection and pigmentation, are ultrastructurally more primitive (the so-called “nonserrated cells”), and are immediately adjacent to some rapidly proliferative TA cells (Fig. 1; refs. 1, 4, 19, and 20); however, these cells express less integrin β1, a putative epidermal stem cell marker (6, 21) (see below). The basal cells located at the shallowest portion of the epidermis express more integrin β1 (21), but they tend to be ultrastructurally more specialized (the “serrated cells”), and they enjoy less physical and pigment protection (4, 19). Finally, the central basal cells under the so-called “epidermal proliferative unit” are known to be slow-cycling (22), and similar units have been shown to occur in reconstituted epidermis consisting of retrovirally tagged epidermal cells (23, 24). However, these columns are seen mainly in thin rodent epidermis, and the fact that these putative stem cells exist as isolated, single cells defies the general rule that stem cells are usually clustered in association with a specialized “niche.” The precise location of stem cells within the epidermal compartment is therefore unsettled.

Markers for Epidermal Stem Cells: The Search Continues

One of the major controversies in the field has to do with the stem cell markers. The uncertainties may have stemmed from variables such as human vs. mouse keratinocytes, body sites, hairy vs. non-hairy skin, different cell isolation techniques, and in vivo vs. cultured keratinocytes. Some integrins have been suggested as markers for epidermal stem cells. The α6β4 integrin is associated with the basal surface, whereas the α2β1 and α3β1 integrins are associated with the lateral (mainly) and basal (minor) surfaces of epidermal basal cells (25). Recent knockout studies indicate that these major epidermal integrins play important roles in basement membrane formation (26–28). Watt and coworkers found that integrin β1-enriched (but not α6-enriched) human epidermal basal cells, from both keratinocyte culture and in vivo foreskin, adhere more rapidly to some extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, and have a higher colony-forming efficiency than unfractionated cells (6, 21, 29). It was therefore suggested that β1 is a marker for epidermal stem cells, and that in vivo stem cells are located in the β1-bright, thinnest portion of the interfollicular epidermis (21). This stem cell location is surprising because, as mentioned earlier, basal cells in the thinnest portion of the epidermis are ultrastructurally more specialized, and are more vulnerable to environmental insults than basal cells located at the bottom of the deep rete ridges. In another series of studies, Kaur and coworkers suggested that α6 integrin is a better marker than β1 for sorting the keratinocyte basal cells of in vivo mouse (hairy) skin; that the rapidly adhering keratinocyte stem cell fraction, which are β1- or α6-positive, is far from being pure; and that the use of additional markers, e.g., the lack of a transferrin receptor (TR), is needed to further segregate stem from TA cells (11, 30, 31).

One of the variables that is particularly confounding relates to the biological state of keratinocyte stem cells in culture. Although in vitro clonogenicity and cumulative proliferative potential provide useful assays for stem cells (16, 32), these cultured cells have been released from the control mechanisms of the in vivo stem cell niche designed to keep them in a slow-cycling state. Thus, 100% of the keratinocyte stem cells become “activated” in culture, as evidenced by increased cell size, proliferation, and migration (14, 33)—features perhaps associated with TA cells and with in vivo wound repair (34). This in vitro expansion of keratinocytes in standard tissue culture conditions is frequently accompanied by a corresponding exhaustion of the cellular proliferative potential (35). This decline in growth potential can be slowed by appropriate tissue culture conditions (35) and apparently can be arrested by returning the cells to a natural or reconstituted in vivo niche, thus achieving long-term coverage of wounds (36, 37)—suggesting strongly a return of the TA cells to an in vivo stem cell state (albeit possibly with a somewhat reduced growth potential). Therefore, keratinocyte stem cells, as we define them in vivo in terms of their slow-cycling feature, completely disappear in most of the (mitogenic) tissue culture environments, with marked changes in their integrin and other markers (34, 38). Hence markers for the in vivo epidermal stem cells may not be identical to those for keratinocytes in large in vitro colonies. This may account for some of the inconsistencies in the field; additional work is needed to clarify this important issue.

Location of Epidermal Stem Cells: A Need to Look Deeper

It is intriguing that the putative skin keratinocyte stem cells, defined as the slow-cycling (label-retaining) cells (9, 10, 39) and independently as the α6briCD71dim cells (11), are found predominantly in the bulge region of the follicle. Unlike the epidermis, the follicular bulge zone contains a cluster of cells that satisfy almost all of the existing criteria for keratinocyte stem cells (Table 1). The bulge is a part of the outer root sheath that is contiguous with the epidermis. It is the attachment site of the arrector pili muscle and marks the lowest end of the upper (permanent) portion of the follicle (Fig. 1). The bulge cells are slow-cycling; have a higher proliferative capacity than the epidermis; have a primitive ultrastructure; are in contact with specialized smooth muscle; enjoy excellent physical protection; and are thought to be a major target of chemical carcinogens and papilloma virus (9, 33, 40–43). Moreover, a recent study showed that the progeny of bulge cells can emigrate into the normal newborn mouse epidermis, and into adult mouse epidermis in response to wounding (39). These data suggest that the bulge represents a major repository of skin keratinocyte stem cells that may be bipotent because they can give rise not only to the hair follicle (pathway 1 in Fig. 1), but also to the epidermis (pathway 2). Thus, some of the confusion about the in vivo location of epidermal stem cells can be resolved if one hypothesizes that (i) the follicular bulge is the repository of the ultimate stem cells of the interfollicular epidermis (39), and that (ii) the bulge stem cells give rise to TA cells with a continuum of decreasing proliferative potential (44). Young TA cells that have arrived in the epidermis can still have an impressive proliferative potential and may be considered progenitor cells (Fig. 1). This hypothesis is applicable only to hair-bearing skin, not to non-hairy skin, such as the foreskin or palm/sole epithelium, which seems to have its own stem cell-in-residence in its basal layer (4).

Concluding Remarks

In addition to the need for more data to further define the relationship between the epidermis and hair follicle, many important issues need to be addressed. More cell surface markers are clearly needed for the further enrichment and molecular characterization of keratinocyte stem cells. It is known that, during wound repair, keratinocyte stem cells can be stimulated to divide and TA cells can increase the number of rounds of DNA replication that they exhibit (15). Do these two cell populations respond to distinct or overlapping growth stimuli? Do keratinocyte stem cells of epidermis/hair follicle, corneal epithelium, and other stratified epithelia share certain molecular markers? What are the cellular and molecular bases for the stem cell niche? What is the plasticity of keratinocyte stem cells (Fig. 1), and what is the molecular mechanism of the instructive mesenchymal signals that seem to be able to change the fate of some keratinocytes (45–47)? We hope that future studies along these lines can lead to a better understanding of the nature and growth regulation of epidermal keratinocyte stem cells, the interrelationship between the epidermis and hair follicle, the possible reversibility of epidermal stem cell and TA cell compartments, the plasticity of keratinocyte stem cells and possibly even TA cells (45), and the involvement of epidermal and hair follicular stem cells in certain skin diseases.

Footnotes

See companion article on page 10960 in issue 20 of volume 97.

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.250380097.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.250380097

References

- 1.Fuchs E, Segre J A. Cell. 2000;100:143–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman I L. Cell. 2000;100:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potten C S, Hendry J H. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1973;24:537–540. doi: 10.1080/09553007314551441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavker R M, Sun T-T. Science. 1982;215:1239–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.7058342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potten C S, Morris R J. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1988;10:45–62. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1988.supplement_10.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watt F M. Philos Trans R Soc London B. 1998;353:831–837. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bickenbach, J. R. (1981) J. Dent. Res.60 Spec. No. C, 1611–1620. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bickenbach J R, Chism E. Exp Cell Res. 1998;244:184–195. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotsarelis G, Sun T-T, Lavker R M. Cell. 1990;61:1329–1337. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90696-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris R J, Potten C S. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112:470–475. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tani H, Morris R J, Kaur P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10960–10965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schermer A, Galvin S, Sun T-T. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:49–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotsarelis G, Cheng S Z, Dong G, Sun T-T, Lavker R M. Cell. 1989;57:201–209. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90958-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller S J, Lavker R M, Sun T-T. Semin Dev Biol. 1993;4:217–240. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehrer M S, Sun T-T, Lavker R M. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2867–2875. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.19.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pellegrini G, Golisano O, Paterna P, Lambiase A, Bonini S, Rama P, De Luca M. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:769–782. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tseng S C. Eye. 1989;3:141–157. doi: 10.1038/eye.1989.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tseng S C G, Sun T-T. In: Stem Cells: Ocular Surface Maintenance. Brightbill F S, editor. St. Louis: Mosby; 1999. pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavker R M, Sun T-T. J Invest Dermatol. 1983;81:121S–127S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12540880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen U B, Lowell S, Watt F M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:2409–2418. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones P H, Harper S, Watt F M. Cell. 1995;80:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris R J, Fischer S M, Slaga T J. J Invest Dermatol. 1985;84:277–281. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12265358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackenzie I C. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:377–383. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12336255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolodka T M, Garlick J A, Taichman L B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4356–4361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Luca M, Tamura R N, Kajiji S, Bondanza S, Rossino P, Cancedda R, Marchisio P C, Quaranta V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6888–6892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brakebusch C, Grose R, Quondamatteo F, Ramirez A, Jorcano J L, Pirro A, Svensson M, Herken R, Sasaki T, Timpl R, et al. EMBO J. 2000;19:3990–4003. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiPersio C M, van Der Neut R, Georges-Labouesse E, Kreidberg J A, Sonnenberg A, Hynes R O. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3051–3062. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raghavan S, Bauer C, Mundschau G, Li Q, Fuchs E. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1149–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones P H, Watt F M. Cell. 1993;73:713–724. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90251-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li A, Simmons P J, Kaur P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3902–3907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaur P, Li A. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:413–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrandon Y, Green H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2302–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang J S, Lavker R M, Sun T-T. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:652–659. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12371671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen B P, Ryan M C, Gil S G, Carter W G. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:554–562. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rheinwald J G, Green H. Nature (London) 1977;265:421–424. doi: 10.1038/265421a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallico G G d, O'Connor N E, Compton C C, Kehinde O, Green H. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:448–451. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408163110706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Compton C C, Gill J M, Bradford D A, Regauer S, Gallico G G, O'Connor N E. Lab Invest. 1989;60:600–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Luca M, Pellegrini G, Bondanza S, Cremona O, Savoia P, Cancedda R, Marchisio P C. Exp Cell Res. 1992;202:142–150. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor G, Lehrer M S, Jensen P J, Sun T T, Lavker R M. Cell. 2000;102:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller S J, Wei Z G, Wilson C, Dzubow L, Sun T-T, Lavker R M. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:591–594. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12366045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobayashi K, Rochat A, Barrandon Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7391–7395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmitt A, Rochat A, Zeltner R, Borenstein L, Barrandon Y, Wettstein F O, Iftner T. J Virol. 1996;70:1912–1922. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1912-1922.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morris R J, Tryson K A, Wu K Q. Cancer Res. 2000;60:226–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Potten C S, Loeffler M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1990;110:1001–1020. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferraris C, Chaloin-Dufau C, Dhouailly D. Differentiation. 1994;57:89–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1994.5720089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferraris C, Bernard B A, Dhouailly D. Int J Dev Biol. 1997;41:491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reynolds A J, Lawrence C, Cserhalmi-Friedman P B, Christiano A M, Jahoda C A. Nature (London) 1999;402:33–34. doi: 10.1038/46938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]