Abstract

Context:

Hyperandrogenism and oxidative stress are related in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), but it is unknown whether hyperandrogenemia can activate oxidative stress.

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of oral androgen administration on fasting and glucose-stimulated leukocytic reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase p47phox subunit gene expression, and plasma thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) in lean healthy reproductive-age women.

Participants, Design, and Setting:

Sixteen lean healthy ovulatory reproductive-age women were treated with 130 mg dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) or placebo (n = 8 each) for 5 d in this randomized, controlled, double-blind study that was performed at an an academic medical center.

Main Outcome Measures:

Leukocytic ROS generation, p47phox gene expression, and plasma TBARS were quantified in the fasting state and 2 h after glucose ingestion, before and after treatment.

Results:

Before treatment, subjects receiving DHEA or placebo exhibited no differences in androgens or any prooxidant markers while fasting and after glucose ingestion. Compared with placebo, DHEA administration raised levels of testosterone, androstenedione, and DHEA-sulfate, increased the percent change in glucose-challenged p47phox RNA content, and increased the percent change in fasting and glucose-challenged ROS generation from mononuclear cells and polymorphonuclear cells, p47phox protein content, and plasma TBARS.

Conclusion:

Elevation of circulating androgens comparable to what is present in PCOS increases leukocytic ROS generation, p47phox gene expression, and plasma TBARS to promote oxidative stress in lean healthy reproductive-age women. Thus, hyperandrogenemia activates and sensitizes leukocytes to glucose in this population.

Hyperandrogenism is a prominent feature of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Serum testosterone in PCOS is typically above the normal premenopausal female range (>70 ng/dl) and well below the male range (>300 ng/dl) with some variance in these limits depending on the assay used for measurement.(1, 2). Insulin resistance is another common finding in PCOS that is thought to promote the hyperandrogenism through the compensatory hyperinsulinemia and also raises the risk of developing hyperglycemia (3, 4).

Hyperglycemia induces oxidative stress by stimulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation from peripheral blood leukocytes. The superoxide radical in particular is a ROS that is generated by the enzyme activity of membrane-bound reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (5). Phosphorylation of p47phox, the key cytosolic component of NADPH oxidase, initiates its translocation to the cell membrane for formation of a functional enzyme complex (6). Superoxide-induced oxidative stress causes lipid peroxidation, protein carbonylation, and DNA damage (7–9). This in turn activates nuclear factor κB (NFκB) to stimulate transcription of TNFα, a known mediator of insulin resistance (10). We have previously reported that leukocytes of lean women with PCOS exhibit increased ROS generation and altered TNFα release after oral glucose ingestion (11, 12). Thus, leukocytic ROS generation in response to hyperglycemia may be a prooxidant trigger for the induction of insulin resistance in PCOS.

Oxidative stress also underpins the development of cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease, which are further complicated by other prooxidant phenomena such as impaired erythrocyte deformity (13–15). Indeed, the same disease profile is associated with the prooxidant state in PCOS that may in part be promoted by hyperandrogenism (16–19). In PCOS, fasting- and hyperglycemia-induced leukocytic ROS generation and p47phox protein are highly correlated with circulating androgens (11, 20). This raises the possibility that activation and sensitization of leukocytes by hyperandrogenism may be capable of promoting oxidative stress. In contrast, leukocytes of normal healthy reproductive-age women are not sensitive to hyperglycemia and do not exhibit a prooxidant, proinflammatory response to glucose challenge (11, 12, 20–22).

We performed a substudy using a previous double-blinded placebo-controlled protocol to examine the effect of oral androgen administration on leukocytic ROS generation, p47phox gene expression, and plasma thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS), a commonly used index of lipid peroxidation. We hypothesized that oral androgen administration increases these markers of oxidative stress in lean, healthy reproductive-age women.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty-five lean, healthy women 20–40 yr of age were initially screened for study participation. Five of these women qualified for study entry but declined participation. Another four women were excluded because they had polycystic ovaries on ultrasound. The remaining 16 volunteers completed the study protocol and are the same well-characterized cohort from our previous study on hyperandrogenism and inflammation (23). Some largely descriptive data from these participants included herein have been presented in the previous publication. All participants had a normal body mass index (18–25 kg/m2) along with regular menses lasting 25–35 d and a luteal-range serum progesterone level consistent with ovulation (>5 ng/ml). Serum androgen concentrations were normal in all participants, and they did not exhibit any skin manifestations of androgen excess or polycystic ovaries on ultrasound.

Diabetes and inflammatory illnesses were excluded in all participants. None of them smoked tobacco or used medications that could impact carbohydrate metabolism or immune function for a minimum of 6 wk before beginning the study. No participants exercised regularly during the 6 months before study participation. Written informed consent was obtained in all participants according to Institutional Review Board guidelines for the protection of human subjects.

Study design

A research pharmacist referred to an electronically generated predefined randomization schedule in which participants received 130 mg/d orally of micronized dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (Spectrum Chemical and Laboratory Products, Gardena, CA) (n = 8) or identical placebo (n = 8) by block assignment as they entered the study protocol. Both preparations were administered at 2100 h for 5 d. Study personnel and participants were blinded to the treatment assignment. A 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was administered to all participants starting at 0900 h after an approximately 12-h fast overnight before and after treatment. The pretreatment OGTT was performed after the start of menstruation (d 5–8) on the morning before beginning DHEA or placebo, and the posttreatment OGTT was performed on the morning after completing the 5 d of assigned treatment.

During each OGTT, blood samples were drawn while fasting and 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min after glucose ingestion. Androgen trough levels were measured from the fasting samples. Glucose and insulin levels from each OGTT were used to calculate an insulin sensitivity index (ISOGTT) using the following formula: 10,000 divided by the square root of (fasting glucose × fasting insulin) × (mean glucose × mean insulin) (24). Body composition was assessed by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in all participants on the day of the initial OGTT as previously described (23).

ROS generation and molecular assays

Mononuclear cells (MNC) and polymorphonuclear cells (PMN) were isolated from blood samples obtained during the OGTT at 0 and 120 min (2 h). ROS generation was measured by chemiluminescence as previously described (25). The mRNA content of p47phox in MNC was quantified by real-time PCR as previously described (26). Primer Express software (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to select the following p47phox primer and probe sequences (GenBank accession no. AF330627): forward primer AGAGCGGTTGGTGGTTCTGT, reverse primer GGAAGGATGCTGGGATCCA, and probe AGATGAAAGCAAAGCGAG. A 28S rRNA signal was used to normalize against differences in RNA isolation and degradation and remained constant with DHEA treatment.

The protein content of p47phox and actin in MNC was quantified by Western blotting as previously described using a monoclonal antibody against p47phox subunit (Transduction Laboratories Inc., San Diego, CA) at a dilution of 1:500 or actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at a dilution of 1:1000 (27). Densitometry was performed on scanned films using Carestream Molecular Imaging software version 5.0.2.30 (Rochester, NY), and all values for p47phox were corrected for loading using those obtained for actin.

Plasma and serum measurements

Plasma glucose and insulin along with serum testosterone, androstenedione, and DHEA-sulfate (DHEA-S) were measured as previously described (23). Estradiol was measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (ThermoFisher Scientific, Franklin, MA). Plasma TBARS concentrations were measured by fluorescence (OXItek; ZeptoMetric Corp., Buffalo, NY). Participant samples were all measured in duplicate in the same assay upon study completion. The interassay and intraassay coefficients of variation for all assays were no greater than 7.4 and 12%, respectively.

Statistics

The StatView software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to perform the statistical analysis. The sample size calculation was based on an expected difference of at least 40% between groups in ROS generation with a sd of 20% and desired power of 80% using our previous study as a reference (11). The primary endpoint was change from baseline in oxidative stress markers between DHEA and placebo groups. Secondary outcomes were also evaluated as change from baseline within a group. All values were initially examined graphically for departure from normality, and the natural logarithm transformation was applied as needed. Unpaired (DHEA vs. placebo) and paired (before vs. after treatment) Student's t tests were performed. Treatment effects on oxidative stress markers were assessed by calculating percent change for each participant in view of interindividual variability. Change from baseline to determine the response to DHEA or placebo was calculated using fasting values (0) before and after treatment (before vs. after, 0). Change from baseline to determine the response to glucose ingestion was calculated using the fasting value (0) and the 2-h postglucose ingestion value (2) for each OGTT before and after treatment with DHEA or placebo (before, 0 vs. 2; after, 0 vs. 2). Pearson linear regression was employed for correlation analyses using the method of least squares. Data are presented as mean ± se, and results with a two-tailed α-level of 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Body composition, glycemic status, and insulin sensitivity

The placebo group and the DHEA-treated group were similar in age (28 ± 2 vs. 28 ± 3 yr, P = 0.89), body mass index (23.0 ± 0.5 vs. 22.1 ± 0.4 kg/m2, P = 0.22), percent total body fat (35.8 ± 1.9 vs. 31.0 ± 2.7%, P = 0.17), percent truncal fat (33.2 ± 2.3 vs. 29.0 ± 2.9%, P = 0.28), and the ratio of truncal fat to leg fat (0.97 ± 0.08 vs. 0.90 ± 0.03, P = 0.47). The ISOGTT was similar in both groups before treatment (10.6 ± 0.9 for DHEA group vs. 10.3 ± 0.9 for placebo group, P = 0.76) and after treatment (10.6 ± 1.0 for DHEA group vs. 8.4 ± 1.2 for placebo group, P = 0.16).

Serum androgen and estradiol levels

Before DHEA or placebo administration, the DHEA-treated group and the placebo group exhibited similar serum levels of testosterone (40 ± 5 vs. 42 ± 4 ng/dl, P < 0.72), androstenedione (1.2 ± 0.4 vs. 1.2 ± 1.0 ng/ml, P = 0.93), DHEA-S (134 ± 24 vs. 138 ± 16 μg/dl, P = 0.87), and estradiol (78 ± 20 vs. 58 ± 13 pg/ml, P = 0.41). Compared with placebo, DHEA administration significantly raised levels of testosterone (123 ± 9 vs. 45 ± 4 ng/dl, P < 0.0001), androstenedione (2.2 ± 0.1 vs. 1.5 ± 0.1 ng/ml, P < 0.002), and DHEA-S (589 ± 40 vs. 147 ± 17 μg/dl, P < 0.0001). Serum estradiol rose during both DHEA and placebo administration and were significantly (P < 0.003) higher compared with baseline only in the placebo group. Nevertheless, estradiol levels remained similar in both groups after treatment (149 ± 53 vs. 150 ± 25 pg/ml, P = 0.99).

Markers of oxidative stress in leukocytes and plasma

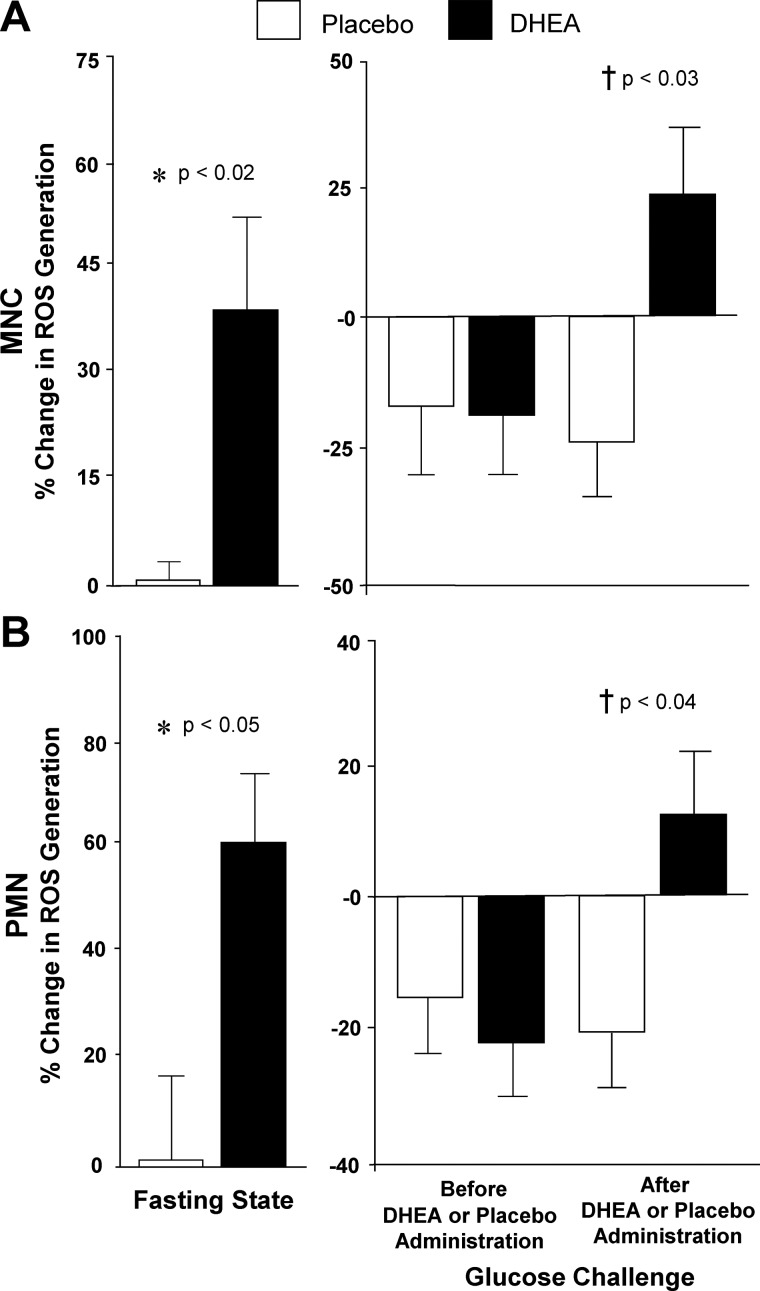

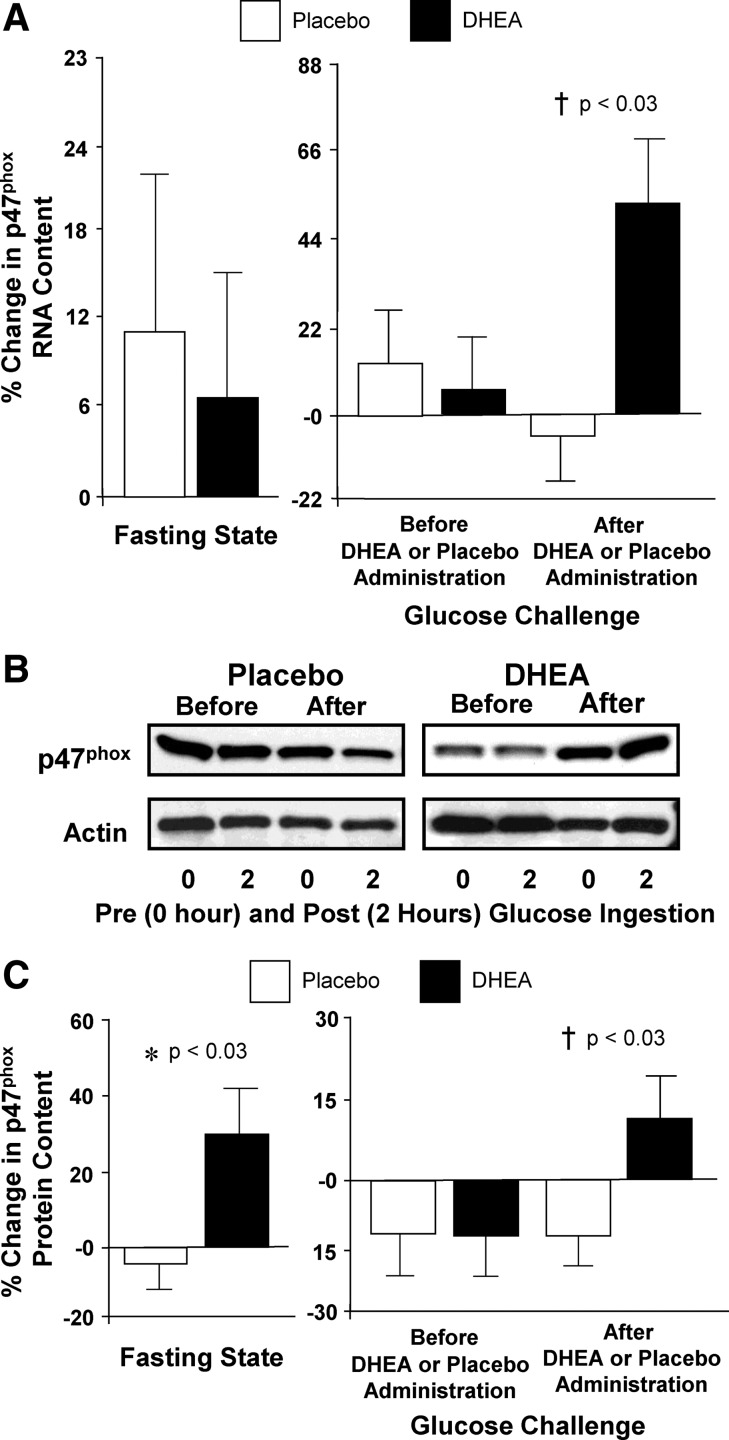

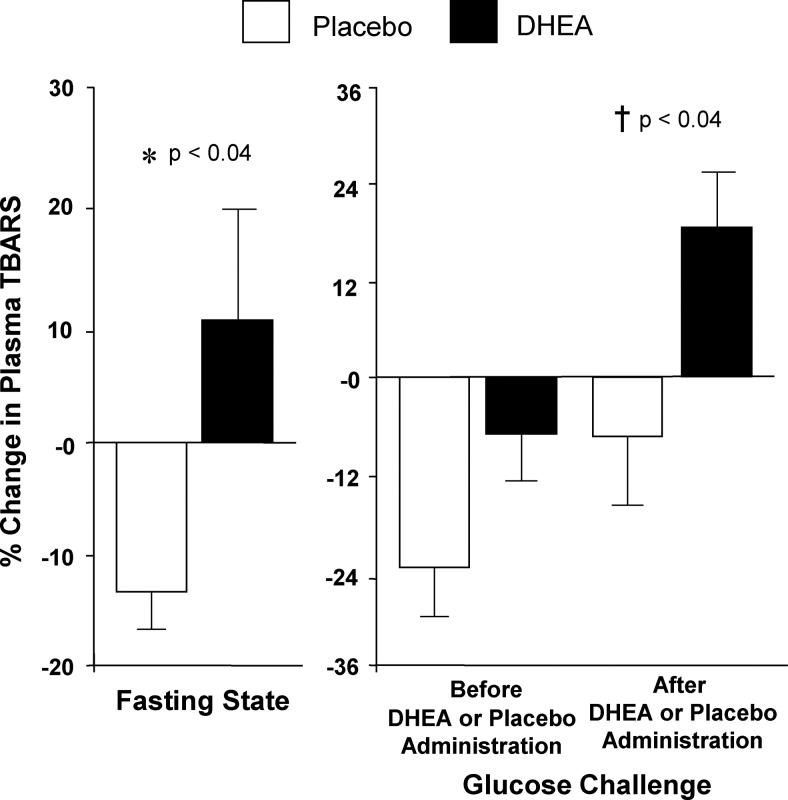

The percent change in ROS generation from MNC and PMN, p47phox protein content from MNC. and plasma TBARS obtained while fasting was significantly (P < 0.05) higher after DHEA compared with placebo (Figs. 1, 2, and 3, respectively). However, there was no significant difference between groups in the percent change in p47phox mRNA content in the fasting state. Before DHEA or placebo administration, the percent change in ROS generation from MNC and PMN, p47phox protein and RNA content from MNC, and plasma TBARS decreased and was similar in both groups after oral glucose ingestion. After DHEA or placebo administration, the percent change in all of these oxidative stress markers decreased once again after oral glucose ingestion in the placebo group but increased in the DHEA group and was significantly (P < 0.04) different between groups.

Fig. 1.

Comparison between groups of the change from baseline (percent) in ROS generation from MNC (A) and PMN (B) for fasting samples before and after (before vs. after, 0) DHEA or placebo administration (left panel) and for fasting and 2-h postglucose ingestion samples for each OGTT (before, 0 vs. 2; after, 0 vs. 2) as a measure of the response to glucose challenge before and after DHEA or placebo administration (right panel). After DHEA administration, the response in leukocytes was significantly greater compared with placebo in the fasting state (*, MNC, P < 0.02; PMN, P < 0.05) and in response to glucose ingestion (†, MNC, P < 0.03; PMN, P < 0.04).

Fig. 2.

A, Comparison between groups of the change from baseline (percent) in NADPH oxidase p47phox subunit mRNA content in MNC for fasting samples before and after (before vs. after, 0) DHEA or placebo administration (left panel) and for fasting and 2-h postglucose ingestion samples for each OGTT (before, 0 vs. 2; after, 0 vs. 2) as a measure of the response to glucose challenge before and after DHEA or placebo administration (right panel). After DHEA administration, the percent change in p47phox mRNA content was significantly greater compared with placebo in response to glucose ingestion (†, P < 0.03). B, Representative Western blots from the two study groups showing the protein content of NADPH oxidase p47phox subunit and actin in MNC homogenates in samples collected in the fasting state (0) and 2 h after glucose ingestion (2) before and after treatment with DHEA or placebo. The samples used to quantify proteins from both study groups were run on the same gel. C, Densitometric quantitative analysis comparing the change from baseline (percent) in MNC-derived NADPH oxidase p47phox subunit protein content between the two study groups for fasting samples before and after (before vs. after, 0) DHEA or placebo administration (left panel) and for fasting and 2-h postglucose ingestion samples for each OGTT (before, 0 vs. 2; after, 0 vs. 2) as a measure of the response to glucose challenge before and after DHEA or placebo administration (right panel). After DHEA administration, the percent change in p47phox protein content was significantly greater compared with placebo in the fasting state (*, P < 0.03) and in response to glucose ingestion (†, P < 0.03).

Fig. 3.

Comparison between groups of the change from baseline (percent) in plasma TBARS for fasting samples before and after (before vs. after, 0) DHEA or placebo administration (left panel) and for fasting and 2-h postglucose ingestion samples for each OGTT (before, 0 vs. 2; after, 0 vs. 2) as a measure of the response to glucose challenge before and after DHEA or placebo administration (right panel). After DHEA administration, the plasma TBARS response was significantly greater compared with placebo in the fasting state (*, P < 0.04) and in response to glucose ingestion (†, P < 0.04).

The within-group analysis revealed a significant increase in the percent change in ROS generation after DHEA administration (MNC, −17.4 ± 13.0 vs. 23.2 ± 14.1, P < 0.03; PMN, −22.5 ± 7.0 vs. 11.3 ± 10.9, P < 0.03) but no change after placebo. However, there was no significant change in p47phox RNA and protein content from MNC and plasma TBARS after administration of DHEA or placebo. All results remained the same after age adjustment.

Correlations

Serum testosterone, androstenedione, and DHEA-S levels after DHEA or placebo administration were positively correlated with the percent change in ROS generation from MNC and PMN in the fasting state for the combined groups (Table 1). DHEA-S levels after DHEA or placebo administration were also positively correlated with the percent change in fasting plasma TBARS.

Table 1.

Pearson correlations for the combined groups of circulating androgen levels after DHEA or placebo administration vs. change from baseline (%) in the fasting state of prooxidant markers that signifies the treatment response to DHEA and placebo and during posttreatment glucose challenge of prooxidant markers that signifies the posttreatment response to glucose ingestion

| ROS generation (% change) |

p47phox expression (% change) |

TBARS (% change) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNC | PMN | RNA | Protein | ||

| Treatment response to DHEA and placebo | |||||

| Testosterone (ng/dl) | |||||

| r | 0.607 | 0.553 | 0.005 | 0.476 | 0.376 |

| P | 0.013a | 0.026a | 0.985 | 0.073 | 0.085 |

| Androstenedione (ng/ml) | |||||

| r | 0.595 | 0.661 | 0.277 | 0.420 | 0.168 |

| P | 0.015a | 0.006a | 0.299 | 0.120 | 0.566 |

| DHEA-S (μg/dl) | |||||

| r | 0.537 | 0.535 | 0.081 | 0.472 | 0.561 |

| P | 0.032a | 0.033a | 0.765 | 0.076 | 0.037a |

| Posttreatment response to glucose ingestion | |||||

| Testosterone (ng/dl) | |||||

| r | 0.729 | 0.648 | 0.433 | 0.683 | 0.595 |

| P | 0.001a | 0.007a | 0.094 | 0.005a | 0.025a |

| Androstenedione (ng/ml) | |||||

| r | 0.721 | 0.491 | 0.485 | 0.497 | 0.288 |

| P | 0.002a | 0.043a | 0.047a | 0.049a | 0.318 |

| DHEA-S (μg/dl) | |||||

| r | 0.711 | 0.665 | 0.537 | 0.666 | 0.646 |

| P | 0.002a | 0.005a | 0.032a | 0.007a | 0.013a |

P < 0.05.

After DHEA or placebo administration, all three androgen levels were once again positively correlated with the percent change in ROS generation from MNC and PMN (Table 1). Androstenedione and DHEA-S levels after DHEA or placebo administration were positively correlated with the percent change in p47phox RNA and protein content, and DHEA-S levels after DHEA or placebo administration were positively correlated with the percent change in plasma TBARS.

After DHEA or placebo administration, glucose levels 2 h after glucose ingestion were positively correlated with the percent change in MNC-derived ROS generation (r = 0.51; P < 0.05), p47phox protein content (r = 0.77; P < 0.0009), and plasma TBARS (r = 0.56; P < 0.04) in response to glucose ingestion for the combined groups (data not shown).

The percent change in fasting ROS generation from MNC was positively correlated with the percent change in fasting p47phox protein expression (r = 0.58; P < 0.03) for the combined groups. With regard to the response to glucose ingestion after DHEA or placebo administration, the percent change in ROS generation from MNC and PMN were positively correlated with each other (r = 0.52; P < 0.04), and the percent change in ROS generation from PMN was positively correlated with the percent change in p47phox RNA content (r = 0.51; P < 0.05) for the combined groups (data not shown).

Measures of body composition and serum estradiol levels were not correlated with each other or with any markers of oxidative stress or with insulin sensitivity in the fasting state or in response to glucose ingestion (data not shown).

Discussion

Our data clearly show for the first time that leukocytes of lean reproductive-age women generate a prooxidant response after raising circulating androgens to levels comparable to what is present in PCOS. These findings corroborate our previous report showing that hyperandrogenism activates and sensitizes leukocytes to physiological hyperglycemia in this healthy population lacking previous evidence of glucose-induced oxidative stress (23). There is increased fasting ROS generation with additional increases in response to glucose ingestion after 5 d of oral androgen administration. Fasting p47phox protein content is also increased followed by a pronounced increase in both p47phox mRNA and protein content in response to glucose ingestion under these same conditions. In fact, glucose-stimulated changes in ROS generation and p47phox gene expression are directly related to posttreatment androgen levels in this lean cohort with normal adiposity. These results illustrate the prooxidant molecular events that may contribute to medical illness as a result of androgen excess. They also support the concept that, in PCOS, hyperandrogenism may be the progenitor of diet-induced oxidative stress independent of obesity or excess abdominal adiposity.

As anticipated, lean healthy reproductive-age women demonstrate no evidence of oxidative stress at the beginning of the study. Leukocytic ROS generation, p47phox protein expression, and plasma TBARS are suppressed after glucose ingestion in both groups before DHEA or placebo administration. This in vivo response to physiological hyperglycemia may represent the norm for lean healthy young women and corroborates our previous studies showing that glucose challenge minimally alters ROS generation and suppresses p47phox protein in addition to various leukocytic proinflammatory mediators including TNFα release in healthy lean young women (11, 20, 21, 28). Placebo administration also culminates in little change in the parameters assessed in the fasting state and reproduces the typical response to glucose challenge. It is possible that limiting the induction of NADPH oxidase activity and subsequent ROS generation is physiologically beneficial when it is necessary to dispose of glucose in the presence of hyperglycemia. Macrophages derived from circulating MNC infiltrate muscle and adipose tissue where they exert a paracrine effect on insulin action (29–31). ROS-induced oxidative stress from MNC-derived macrophages triggers NFκB activation and subsequent TNFα release, which in turn inhibits insulin signaling to impair glucose uptake (10). Conversely, insulin-resistant animals demonstrate improved insulin sensitivity after MNC-derived macrophages are ablated in muscle (32). Thus, negative regulation of NADPH oxidase activity in the postprandial state to limit ROS generation may optimize insulin signaling in lean reproductive-age women to facilitate glucose disposal.

The rise in serum androgens during the short course of oral androgen administration activates previously resting leukocytes in the fasting state and subsequently increases leukocyte sensitivity to glucose ingestion in our study volunteers who lack previous evidence of oxidative stress. There is increased leukocytic ROS generation, p47phox protein content, and plasma TBARS after DHEA administration compared with placebo in the fasting state, and in response to glucose ingestion. There is also an increase in p47phox RNA content in response to glucose ingestion. These pivotal results demonstrate that elevated circulating androgens are capable of fostering oxidative stress in a fashion similar to what is observed in chronically inflamed, insulin-resistant individuals (33). This response is substantiated by the positive association between androgen levels and ROS generation, p47phox protein content, and plasma TBARS after DHEA or placebo administration in the same circumstance. The positive association between glucose levels measured 2 h after glucose ingestion and ROS generation, p47phox protein content, and plasma TBARS after DHEA or placebo administration underscores the impact of androgen-induced leukocyte sensitization to hyperglycemia in the development of oxidative stress. The positive association between leukocytic ROS generation and p47phox gene expression after glucose ingestion lends additional support to this effect. The results of our current study solidify concepts brought forth in our previous reports. First, they mimic the hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress we described in women with PCOS regardless of body mass status and in obese young women without PCOS (11, 20, 28). Second, they extend our understanding of the hyperandrogenemia-induced leukocytic response, which is characterized not only by NFκB activation but also by prooxidant ROS generation (23). It is known that ROS generation and up-regulation of the NFκB inflammation pathway is directly mediated in leukocytes in an androgen receptor-dependent fashion and may explain our key findings of hyperandrogenemia-induced oxidative stress (34, 35). In fact, induction of hyperandrogenism produces systemic oxidative stress in normal female mice but not in mice with testicular feminization lacking the androgen receptor (36). Future studies to further support this mechanism should focus on nuclear androgen receptor quantification and in vitro androgen exposure with and without androgen receptor blockade using leukocytes from lean healthy young women.

The absence of excess abdominal adiposity indicated by a truncal fat to leg fat ratio below 1.0 may explain the unchanged insulin sensitivity in the face of hyperandrogenemia-induced oxidative stress in our lean healthy young female participants. In fact, measures of abdominal adiposity in our study population are not associated with any oxidative stress markers or insulin sensitivity. This is in contrast to women with PCOS who often have excess adiposity, particularly in the abdomen even when lean (12, 37). Oxidative stress in chronically inflamed excess adipose tissue may mediate insulin resistance in PCOS by stimulating a more sustained NFκB activation and excess adipose tissue-related TNFα production. In corroboration, abdominal adiposity in PCOS is positively associated with hyperglycemia-induced p47phox protein content and negatively associated with insulin sensitivity (11, 12).

DHEA treatment has been shown to elicit antiinflammatory, insulin-sensitizing, glucose-lowering effects due in part to the first-pass liver effect associated with oral administration (38–40). However, these effects have been reported mostly in animals with a physiology that is considerably different from humans and mainly in physical states accompanied by severe immune challenges such as genetically induced obesity, sepsis, trauma, and hemorrhage (38, 40). Thus, a potential mitigating effect of DHEA administration is unlikely to have averted a worsening of insulin sensitivity by blocking the prooxidant response observed in the lean healthy reproductive-age women in our study. Conversely, it is unlikely that oxidative stress is induced by an increase in circulating estrogen after peripheral conversion from DHEA. The modest rise in estrogen and the absolute concentrations observed in both study groups before and after DHEA administration merely reflect the normal excursion observed in the midfollicular phase of the menstrual cycle per the protocol. Estrogen levels after DHEA treatment are also not related to any oxidative stress markers or insulin sensitivity. Finally, the modest sample size powered mainly to compare the prooxidant response between groups or the brief course of treatment may account for the inability to detect an alteration in insulin sensitivity or all-around within-group significant differences. Further investigation is merited to ascertain whether chronic androgen administration in a larger cohort can sufficiently activate leukocytes to elicit any quantifiable metabolic derangements.

In conclusion, hyperandrogenemia to the degree present in PCOS stimulates oxidative stress as evidenced by increases in ROS generation, p47phox gene expression, and circulating TBARS in the fasting state and in response to glucose ingestion. These findings extend our knowledge of the immune-modulating effects of androgen excess by illustrating the resultant prooxidant phenomenon that precedes NFκB activation and confirms our recent discovery that hyperandrogenism activates and sensitizes leukocytes to physiological hyperglycemia in lean healthy reproductive-age women (23).

Acknowledgments

We thank the nursing staff of the Mayo Clinic Center for Translational Science Activities' (CTSA) Clinical Research Unit for supporting the implementation of the study and assisting with data collection.

This work was presented at the 93rd meeting of the Endocrine Society, Boston, MA, June 4–7, 2011.

This research was supported by Grants HD-048535 to F.G. and DK41973 to K.S.R. from the National Institutes of Health and RR-024150 to the CTSA from the National Center for Research Resources.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- DHEA

- Dehydroepiandrosterone

- DHEA-S

- DHEA-sulfate

- MNC

- mononuclear cells

- NADPH

- reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NFκB

- nuclear factor κB

- OGTT

- oral glucose tolerance test

- PCOS

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- PMN

- polymorphonuclear cells

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- TBARS

- thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances.

References

- 1. Knochenhauer ES, Key TJ, Kahsar-Miller M, Waggoner W, Boots LR, Azziz R. 1998. Prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected black and white women of the southeastern Unites States: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:3078–3082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carmina E, Rosato F, Janni A, Rizzo M, Longo RA. 2006. Relative prevalence of different androgen excess disorders in 950 women refereed because of clinical hyperandrogenism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:2–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burghen GA, Givens JR, Kitabchi AE. 1980. Correlation of hyperandrogenism with hyperinsulinemia in polycystic ovarian disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 50:113–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nestler JE, Jakubowicz DJ, de Vargas AF, Brik C, Quintero N, Medina F. 1998. Insulin stimulates testosterone biosynthesis by human theca cells from women with polycystic ovary syndrome by activating its own receptor and using inositoglycan mediators as the signal transduction system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:2001–2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chanock SJ, el Benna J, Smith RM, Babior BM. 1994. The respiratory burst oxidase. J Biol Chem 269:24519–24522 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Groemping Y, Lapouge K, Smerdon SJ, Rittenger K. 2003. Understanding activation of NADPH oxidase: a structural characterization of p47phox. Biophys J 84:356A (Abstract)12524289 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jain SK. 1989. Hyperglycemia can cause membrane lipid peroxidation and osmotic fragility in human red blood cells. J Biol Chem 264:21340–21345 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aljada A, Thusu K, Armstrong D, Nicotera T, Dandona P. 1995. Increased carbonylation of proteins in diabetes. Diabetes 44(Suppl 1):113A (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dandona P, Thusu K, Cook S, Snyder B, Makowski J, Armstrong D, Nicotera T. 1996. Oxidative damage to DNA in diabetes mellitus. Lancet 347:444–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hotamisligil GS, Murray DL, Choy LN, Spiegelman BM. 1994. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibits signaling from the insulin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:4854–4858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. González F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP. 2006. Reactive oxygen species-induced oxidative stress in the development of insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:336–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. González F, Minium J, Rote NS, Kirwan JP. 2005. Hyperglycemia alters tumor necrosis factor-α release from mononuclear cells in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:5336–5342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shi Y, Cosentino F, Camici GG, Akhmedov A, Vanhoutte PM, Tanner FC, Lüscher TF. 2011. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein activates p66Shc via lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1, protein kinase C-β, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase kinase in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31:2090–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Floor E, Wetzel MG. 1998. Increased protein oxidation in human substantia nigra pars compacta in comparison with basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex measured with an improved dinitrophenylhydrazine assay. J Neurochem 70:268–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brinkmann C, Blossfeld J, Pesch M, Krone B, Wiesiollek K, Capin D, Montiel G, Hellmich M, Bloch W, Brixius K. 18 October 2011. Lipid-peroxidation and peroxiredoxin-overoxidation in the erythrocytes of non-insulin-dependent type 2 diabetic men during acute exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 10.1007/s00421-011-2203-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Victor VM, Rocha M, Bañuls C, Sanchez-Serrano M, Sola E, Gomez M, Hernandez-Mijares A. 2009. Mitochondrial complex I impairment in leukocytes from polycystic ovary syndrome patients with insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:3505–3512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rasgon NL, Altshuler LL, Fairbanks L, Elman S, Bitran J, Labarca R, Saad M, Kupka R, Nolen WA, Frye MA, Suppes T, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, Leverich G, Grunze H, Walden J, Post R, Mintz J. 2005. Reproductive function and risk for PCOS in women treated for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 7:246–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Donà G, Sabbadin C, Fiore C, Bragadin M, Giorgino FL, Ragazzi E, Clari G, Bordin L, Armanini D. 2012. Inosotol administration reduces oxidative stress in erythrocytes of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol 166:703–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adams MR, Williams JK, Kaplan JR. 1995. Effects of androgens on coronary artery atherosclerosis and atherosclerosis-related impairment of vascular responsiveness. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 15:562–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. González F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP. 2007. Hyperandrogenism is related to reactive oxygen species generation from pre-activated leukocytes in polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Sci 14(2 Suppl):215A (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 21. González F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP. 2006. In vitro evidence that hyperglycemia stimulates tumor necrosis factor-α release in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol 188:521–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. González F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP. 2006. Increased activation of nuclear factor κB triggers inflammation and insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:1508–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. González F, Nair KS, Daniels JK, Basal E, Schimke JM. 2012. Hyperandrogenism sensitizes mononuclear cells to promote glucose-induced inflammation in lean reproductive-age women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302:E297–E306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. 1999. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing. Diabetes Care 22:1462–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. González F, Rote NS, Minium J, O'leary VB, Kirwan JP. 2007. Obese reproductive age women exhibit a proatherogenic inflammatory response during hyperglycemia. Obesity 15:2436–2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Balagopal P, Schimke JC, Ades PA, Adey D, Nair KS. 2001. Age effect on transcript levels and synthesis rate of muscle MHC and response to resistance exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 80:E203–E208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aljada A, Ghanim H, Dandona P. 2002. Translocation of p47phox and activation of NADPH oxidase in mononuclear cells. Methods Mol Biol 196:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. González F, Minium J, Rote NS, Kirwan JP. 2006. Altered tumor necrosis factor-α release from mononuclear cells of obese reproductive age women during hyperglycemia. Metabolism 55:271–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nguyen MT, Favelyukis S, Nguyen AK, Reichart D, Scott PA, Jenn A, Liu-Bryan R, Glass CK, Neels JG, Olefsky JM. 2007. A Subpopulation of macrophages infiltrates hypertrophic adipose tissue and is activated by free fatty acids via toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and JNK-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem 282:35279–35292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Varma V, Yao-Borengasser A, Rasouli N, Nolen GT, Phanavanh B, Starks T, Gurley C, Simpson P, McGehee RE, Jr, Kern PA, Peterson CA. 2009. Muscle inflammatory response and insulin resistance: synergistic interaction between macrophages and fatty acids leads to impaired insulin action. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296:E1300–E1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr 2003. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112:1796–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patsouris D, Li PP, Thapar D, Chapman J, Olefsky JM, Neels JG. 2008. Ablation of CD11c-positive cells normalize insulin sensitivity in obese insulin resistant animals. Cell Metab 8:301–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ghanim H, Aljada A, Hofmeyer D, Syed T, Mohanty P, Dandona P. 2004. Circulating mononuclear cells in the obese are in a proinflammatory state. Circulation 110:1564–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ashcroft GS, Mills SJ. 2002. Androgen receptor-mediated inhibition of cutaneous wound healing. J Clin Invest 110:615–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ripple MO, Henry WF, Schwarze SR, Wilding G, Weindruch R. 1999. Effects of antioxidants on androgen-induced AP-1 and NF-κB DNA-binding activity in prostate carcinoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:1227–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu S, Navarro G, Mauvais-Jarvis F. 2010. Androgen excess produces systemic oxidative stress and predisposes to β-cell failure in female mice. PLoS one 5:e11302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carmina E, Bucchieri S, Esposito A, Del Puente A, Mansueto P, Orio F, Di Fede G, Rini G. 2007. Abdominal fat quantity and distribution in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and extent of its relation to insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2500–2505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kimura M, Tanaka S, Yamada Y, Kiuchi Y, Yamakawa T, Sekihara H. 1998. Dehydroepiandrosterone decreases tumor necrosis factor-α and restores insulin sensitivity: independent effect from secondary weight reduction in genetically obese zucker fatty rats. Endocrinology 139:3249–3253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aoki K, Saito T, Satoh S, Mukasa K, Kaneshiro M, Kawasaki S, Okamura A, Sekihara H. 1999. Dehydroepiandrosterone suppresses the elevated hepatic glucose-6-phospatase and fructose-1,6-biphosphatase activities in C57BL/Ksj-db/db mice. Diabetes 48:1579–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barkhausen T, Hildebrand F, Krettek C, van Griensven M. 2009. DHEA-dependent and organ-specific regulation of TNF-α mRNA expression in a murine polymicrobial sepsis and trauma model. Critical Care 13:R114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]