Abstract

Context:

Non-nutritive sweeteners can bind to sweet-taste receptors present not only in the oral cavity, but also on enteroendocrine and pancreatic islet cells. Thus, these sweeteners may have biological activity by eliciting or inhibiting hormone secretion. Because consumption of non-nutritive sweeteners is common in the United States, understanding the physiological effects of these substances is of interest and importance.

Evidence Acquisition:

A PubMed (1960–2012) search was performed to identify articles examining the effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on gastrointestinal physiology and hormone secretion.

Evidence Synthesis:

The majority of in vitro studies showed that non-nutritive sweeteners can elicit secretion of gut hormones such as glucagon-like peptide 1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide in enteroendocrine or islet cells. In rodents, non-nutritive sweeteners increased the rate of intestinal glucose absorption, but did not alter gut hormone secretion in the absence of glucose. Most studies in humans have not detected effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on gut hormones or glucose absorption. Of eight human studies, one showed increased glucose-stimulated glucagon-like peptide 1 secretion after diet soda consumption, and one showed decreased glucagon secretion after stevia ingestion.

Conclusions:

In humans, few studies have examined the hormonal effects of non-nutritive sweeteners, and inconsistent results have been reported, with the majority not recapitulating in vitro data. Further research is needed to determine whether non-nutritive sweeteners have physiologically significant biological activity in humans.

Non-nutritive sweetener consumption, largely in the form of diet soda, has been associated in epidemiological studies with numerous adverse metabolic outcomes, including weight gain, the metabolic syndrome, and diabetes (1–7). In contrast, a small number of randomized, controlled trials involving these sweeteners have generally shown neutral to mildly beneficial metabolic outcomes with non-nutritive sweetener use, such as weight stability or decreased weight regain after dieting (8–10). Certainly, epidemiological studies cannot demonstrate causality, and one likely explanation for the observed correlation between weight gain and non-nutritive sweetener use is that people at risk of weight gain may choose to consume these sweeteners in an effort to reduce caloric sugar consumption. Another potential explanation for the epidemiological association between non-nutritive sweetener use and weight gain, largely supported by rodent data (11), is that training people to associate the sensation of “sweetness” with foods or drinks that are low in calories may cause them to overeat when presented with high-calorie, sugar-sweetened versions of these foods and beverages.

Although non-nutritive sweeteners have generally been considered metabolically inert, recent data suggest that these sweeteners may have physiological effects that alter appetite and/or glucose metabolism. Much of the research discussed in this review was predicated by the discovery of the structure of the sweet-taste receptor in 2001, followed shortly by the demonstration that sweet-taste receptors, in addition to being located on taste buds in the oropharynx, are found in enteroendocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract (12, 13) and other tissues, such as the pancreas (14).

Taste Perception

To understand the role of non-nutritive sweeteners in physiology, it is critical to understand taste perception. This has been thoroughly reviewed by others (15, 16), and is briefly summarized here. The tongue contains three varieties of taste papillae—the fungiform, foliate, and circumvallate—each of which contains one to hundreds of taste buds. The classic representation of the tongue as having regions specialized for differing tastes has been largely debunked, with the observation that all of the five major tastes [sweet, bitter, salty, sour, and umami (the taste of “savory,” exemplified by monosodium glutamate and aspartate)] can be sensed in all regions of the tongue.

Sweet, bitter, and umami tastes are sensed via G protein-coupled taste receptors located on taste receptor cells within taste buds and elsewhere in the oropharynx. Each individual cell expresses a single receptor type (either sweet, bitter, or umami), and thus is specialized to perceive a single taste (17). These cells project to neurons in the brain, permitting conscious awareness of taste. The sweet, bitter, and umami receptors are heterodimeric receptors, with the combination of subunits conveying their flavor specificity. The umami taste receptor has a T1R1 and a T1R3 subunit, whereas the sweet-taste receptor has a T1R3 and a T1R2 subunit (15). The bitter taste receptor family contains numerous binary combinations (∼25 in humans) of type 2 receptors. Because bitter tastants are often toxins, the substantial heterogeneity of bitter receptors is likely due to the evolutionary advantages of being able to detect a broad range of potentially toxic substances (18). Sour taste is sensed via ion channels. The taste of sodium salts is sensed at least in part via amiloride-sensitive sodium channels (19), but the sensory mechanisms for other salts have not been identified.

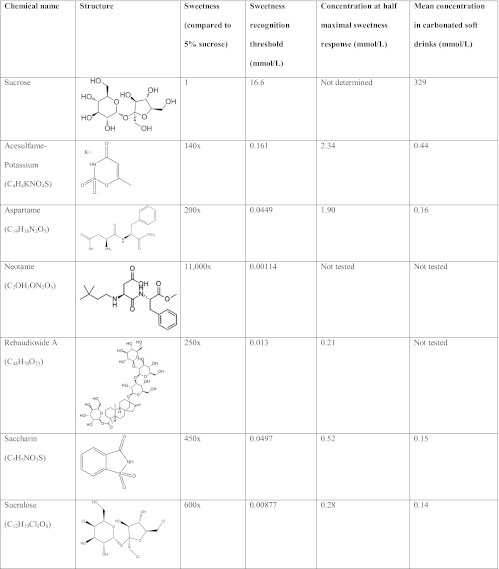

The sweet-taste receptor can bind to chemicals of widely varying structures, including the caloric sugars (e.g. sucrose, glucose, and fructose), sweet proteins such as thaumatin and monellin, and non-nutritive sweeteners. Non-nutritive sweeteners are also known as “artificial sweeteners” or “low-calorie sweeteners,” because some (such as aspartame) have measurable caloric value, albeit negligible at the concentrations used. Chemical and sensory properties of the six Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved non-nutritive sweeteners (with sucrose for comparison) are shown in Table 1. The sweeteners are: acesulfame-K, aspartame, neotame, saccharin, stevia, and sucralose. Stevia is a botanically derived sweetener from the Stevia rebaudiana plant and consists of related chemicals called steviol glycosides; only the sweetest of these, rebaudioside A, is shown in Table 1. Typical concentrations of sweeteners in carbonated beverages are also listed; these are frequently lower than anticipated based on sweetness equivalence because many beverages contain more than one non-nutritive sweetener. The metabolic fate of non-nutritive sweeteners varies from presumed excretion in a nonmetabolized manner (acesulfame-K, saccharin, sucralose) to intestinal breakdown into the sweetener's components (e.g. aspartame becomes aspartic acid, phenylalanine, and methanol) or deesterification (neotame) (20).

Table 1.

Chemical properties of FDA-approved non-nutritive sweeteners

Sweetness data were obtained from psychophysical testing in human volunteers (58, 59). The sweetness recognition threshold is the lowest concentration at which subjects identified the solution as sweet. For the non-nutritive sweeteners, subjects' perception of sweetness reached a maximum asymptotically. Thus, the concentration range from sweetness recognition to half maximal sweetness provides a sense of the biological response range of sweet-taste receptors to individual sweeteners. Sucrose was not tested at high enough concentrations to determine maximal sweetness. Mean concentrations of sweeteners in carbonated soft drinks were obtained from a sample of 19 beverages from Belgium (60).

Given the chemical heterogeneity of these compounds, it is not surprising that not all bind to the same ligand binding domain of the sweet-taste receptor (21, 22). However, all non-nutritive sweeteners have the ability to activate the oropharyngeal sweet-taste receptors, thereby generating a signal that ultimately results in the conscious perception of sweetness. Upon ligand binding to the receptor, associated G proteins, such as α-gustducin, are activated, resulting in increased phospholipase Cβ2, which increases production of the second messengers inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol. This in turn leads to activation of the taste-transduction channel, TRPM5 (transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 5, also known as long transient receptor potential channel 5), resulting in increased intracellular calcium and neurotransmitter release (16). There are important species differences in the perception of sweet compounds. For example, the non-nutritive sweetener aspartame does not stimulate sweet-taste receptors in the mouse, and thus mice do not exhibit behavioral responses to aspartame (17).

Not Just in the Mouth?

After the discovery of the structure of the sweet-taste receptor (17) and its G protein, gustducin (23), immunohistochemical techniques were used to identify sites of tissue expression of these proteins outside of the oral cavity. It was quickly learned that sweet-taste receptors were located in other regions of the gastrointestinal tract—most notably, in enteroendocrine L cells (24, 25) and K cells (26). Enteroendocrine cells are specialized cells of the gastrointestinal tract that secrete a variety of hormones. They are sparse, comprising less than 1% of epithelial cells within the intestine. In addition to the gastrointestinal mucosa, sweet-taste receptors have also been identified in pancreatic β-cells (14), in the biliary tract (27), and in the lungs (28). It is important to note, however, that conscious perception of sweetness is conveyed only after activation of oral sweet-taste receptors; sweet-taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract and other tissues do not convey taste.

The functional importance of sweet-taste receptors on enteroendocrine cells was recently investigated in two publications from the Beglinger group (25, 29) using the sweet-taste inhibitor, lactisole. Lactisole [sodium 2-(4-methoxyphenoxy) propionate] inhibits sweet and umami taste perception in primates by binding to the transmembrane domain of the T1R3 receptor (30). In human psychophysical studies, lactisole decreased sweetness perception for 12 of 15 sweet compounds tested, including both caloric and non-nutritive sweeteners (31). The Beglinger group studies demonstrated that, in healthy humans, the addition of lactisole to an intragastric infusion of glucose decreased secretion of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY) (both made by L cells) by 24 to 47% and 15 to 27%, respectively. In contrast, cholecystokinin secretion (from I cells, which are not known to express sweet-taste receptors) was unaffected by lactisole. These data support the idea that ligand binding to sweet-taste receptors on L cells is partially responsible for L-cell hormone secretion; there are undoubtedly sweet-taste receptor-independent mechanisms as well.

Non-Nutritive Sweeteners and Hormone Secretion

Given that both non-nutritive and caloric sweeteners bind to oral sweet-taste receptors, resulting in the conscious sensation of sweetness, it is logical to hypothesize that non-nutritive sweeteners could bind to sweet-taste receptors on enteroendocrine cells, likewise causing signal transduction and downstream actions such as hormone secretion. This possibility has been explored in multiple systems, from cell lines to rodents to humans, with inconsistent results (Table 2–4).

Table 2.

Effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on gut hormones and glucose absorption: in vitro effects

| Sweetener | Concentration | Model system | Biological effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acesulfame-K | 2 mm (33) | Cultured mouse intestine | No effect on GLP-1 |

| 50 mm (14) | MIN6 cells | Increased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion | |

| Saccharin | 50 mm (14) | MIN6 cells | Increased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion |

| Sucralose | 0.2, 1, 5, 20 mm (32) | NCI-H716 cells | GLP-1 secretion at 1 and 5 mm but not at 0.2 or 20 mm |

| 50 mm (24) | GLUTag cells | GIP and GLP-1 secretion | |

| 1 mm (34) | Isolated mouse K-cells | No effect on GIP | |

| 1 and 20 mm (33) | Cultured mouse intestine | No effect on GLP-1 at 1 mm. Increased GLP-1 at 20 mm only in colon (not small bowel) | |

| 50 mm (14) | MIN6 cells | Increased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion | |

| 10 and 50 mm (14) | Isolated mouse islets | Increased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion | |

| 2.5 mm (43) | Isolated rat islets | Increased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion |

Measurable biological effects are italicized. NCI-H716 is a human L cell line; GLUTag is a mouse enteroendocrine cell line; MIN6 is a mouse insulinoma (β-cell) line.

Table 3.

Effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on gut hormones and glucose absorption: in vivo effects on animals

| Sweetener | Dose | Model system | Biological effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acesulfame-K | 10 mm in drinking water × 2 wk (24) | Mouse | Increased SGLT-1 expression |

| 1 g/kg (26) | Rat | No effect on GIP or GLP-1 | |

| Not reported (51) | Rat | Increased GLUT-2-mediated glucose absorption | |

| Aspartame | 1 mm in drinking water × 2 wk (24) | Mouse | No effect on SGLT-1 expression |

| D-tryptophan | 50 mg/kg (26) | Rat | No effect on GIP or GLP-1 |

| Saccharin | 20 mm × 2 wk (24) | Mouse | Increased SGLT-1 expression |

| Not reported (51) | Rat | Increased GLUT-2-mediated glucose absorption | |

| Stevia | 1 g/kg (26) | Rat | No effect on GIP or GLP-1 |

| 0.03 g/kg/d (46) | Rat (T2D) | Reduced glucose, insulin, and glucagon | |

| Sucralose | 2 mm in drinking water × 2 wk (24) | Mouse | Increased SGLT-1 expression and glucose absorption |

| 1 mm intestinal infusion (51) | Rat | Increased GLUT-2-mediated glucose absorption | |

| 1g/kg (26) | Rat | No effect on GIP or GLP-1 |

Measurable biological effects are italicized. T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Table 4.

Effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on gut hormones and glucose absorption: in vivo effects on humans

| Sweetener | Dose | Subjects | Biological effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acesulfame-K | 220 mg (25) | Healthy | No effect on PYY or GLP-1 |

| Acesulfame-K + sucralose in diet cola | 26 mg acesulfame-K + 46 mg sucralose (39, 40) | Healthy, T1D, T2D | Increased glucose-stimulated GLP-1 in healthy and T1D, but not T2D. No effect on insulin, glucose, GIP, or PYY |

| Aspartame | 169 mg (25) | Healthy | No effect on PYY or GLP-1 |

| Stevia | 1 g (47) | T2D | Decreased glucagon and blood glucose. No effect on GLP-1 or GIP |

| Sucralose | 41.5 mg (35) | Healthy | No effect on PYY or GLP-1 |

| 62 mg (25) | Healthy | No effect on PYY or GLP-1 | |

| 80 and 800 mg (37) | Healthy | No effect on GIP or GLP-1 | |

| 960 mg (41) | Healthy | No effect on glucose-stimulated GLP-1 or glucose absorption rate | |

| 85 mg (36) | Healthy | No effect on ghrelin, glucagon, insulin, or glucose | |

| 60 mg (42) | Healthy | No effect on mixed-meal stimulated GLP-1, GIP |

Measurable biological effects are italicized. NCI-H716 is a human L cell line; GLUTag is a mouse enteroendocrine cell line; MIN6 is a mouse insulinoma (β-cell) line. T1D, Type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Jang et al. (32) showed that the non-nutritive sweetener sucralose (the active ingredient in Splenda) stimulated GLP-1 secretion from a human L-cell line (NCI-H716 cells) in a dose-dependent fashion. This GLP-1 secretion could be blocked by the sweet-taste inhibitor lactisole, implying that sucralose was acting via sweet-taste receptors. Similar results were published by Margolskee et al. (24), showing that sucralose stimulated both GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) secretion from a murine enteroendocrine cell line (GLUTag cells); this effect was likewise blocked by the sweet-taste inhibitor, gurmarin, implying that the effect was sweet-taste receptor mediated. These results were not confirmed in two other studies, however, in which sucralose and another sweetener, acesulfame-K, failed to increase GLP-1 in cultured mouse intestine (33), or GIP secretion in isolated mouse K cells (34). The concentrations of non-nutritive sweeteners used in these in vitro studies (Table 2) were generally in the upper half of, or well above, the expected dynamic response range of the sweet-taste receptor, and discrepant results among the studies cannot be easily explained on the basis of the sweetener concentrations used.

The majority of in vivo data have failed to confirm effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on hormone secretion observed in vitro. Fujita et al. (26) found that gastric gavage (thus bypassing lingual taste receptors) of four different non-nutritive sweeteners (acesulfame-K, stevia, d-tryptophan, and sucralose) failed to increase GLP-1 or GIP secretion in rats. It is notable that in this experiment, the doses of sweetener given (1 g/kg) were 1000-fold in excess of the concentrations typically found in commercial products such as diet sodas. Four similar experiments in healthy humans showed no effect of oral sucralose (35, 36) or intragastric sucralose, aspartame, or acesulfame-K on GLP-1, PYY, ghrelin, or GIP secretion (37, 38). Taken together, these data support the notion that non-nutritive sweeteners in isolation are not a sufficient stimulus to cause gut hormone secretion in vivo.

Our group examined this question using a slightly different design, testing whether non-nutritive sweeteners in a commercially available diet soda could change gut hormone secretion in combination with caloric sugars (39). Healthy adolescents and young adults drank either caffeine-free Diet Rite cola or carbonated water, followed 10 min later by an oral glucose load in a randomized, crossover design. We found that the plasma GLP-1 area under the curve after glucose ingestion was 34% higher after diet soda compared with carbonated water (P = 0.029). This finding was replicated in patients with type 1 diabetes, in whom the GLP-1 area under the curve was 43% higher in the diet soda condition, but not in those with type 2 diabetes (40). These data imply that diet soda (presumably via the non-nutritive sweeteners) enhances glucose-stimulated GLP-1 secretion, although it is not clear from the experiment whether this effect was mediated via sweet-taste receptors on enteroendocrine cells, lingual sweet-taste receptors, or another mechanism altogether. In addition, the clinical significance of this finding is not clear because insulin levels were not statistically different between the two conditions, and other GLP-1 effects, such as satiety and gastric emptying, were not measured. It is noteworthy that these findings were not confirmed by another study, which found no difference in plasma GLP-1 during intraduodenal infusion of 4 mm sucralose vs. saline in combination with glucose (41). Data from Gerspach et al. (29) support the idea that sweet-taste sensing is less important for GLP-1 secretion after intraduodenal vs. intragastric delivery of glucose, potentially accounting for the differing results in the two studies. Wu et al. (42) studied the effects of sucralose before a solid meal (powdered potatoes with 20 g glucose and egg yolk) and reported no effect on GIP or GLP-1 secretion; however, there was no unsweetened control.

Pancreatic β-cells, although located outside the intestinal epithelium, may be considered enteroendocrine cells. In 2009, Nakagawa et al. (14) identified sweet-taste receptors in MIN6 cells (a mouse insulinoma cell line frequently used to study β-cell function) and in mouse islets. In MIN6 cells, the non-nutritive sweeteners sucralose, saccharin, and acesulfame-K stimulated insulin secretion in the presence of glucose at low concentration (3 mm), and sucralose augmented glucose-stimulated insulin secretion across a range of glucose concentrations, from 3 to 25 mm. Consistent with known intracellular signaling mechanisms in lingual taste cells, sucralose increased intracellular Ca2+, and this effect was blocked by the sweet-antagonist gurmarin, implying that it was mediated via sweet-taste receptors. In isolated mouse islets, sucralose enhanced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion at low glucose concentrations (2.8 mm), but not at high glucose concentrations (20 mm). Although non-nutritive sweetener concentrations within islets in vivo have not been measured, the 10 to 50 mm concentrations used in these experiments are likely to be an order of magnitude above what might be found in humans, thus bringing into question the biological relevance of these results. However, in rat islets, 2.5 mm saccharin, a concentration that might conceivably be achieved by high levels of consumption in humans, was shown to increase basal insulin secretion (43). The effects on islet hormone secretion of the plant-derived sweetener, stevia, and its sweetest component molecule, rebaudioside A, have been extensively studied by the Hermansen group. Their work suggests that this class of compounds enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion via inhibition of ATP-sensitive K-channels (44, 45) and lowers blood glucose in both rodents (46) and humans (47) with type 2 diabetes primarily by suppressing glucagon release.

Non-Nutritive Sweeteners and Intestinal Glucose Absorption

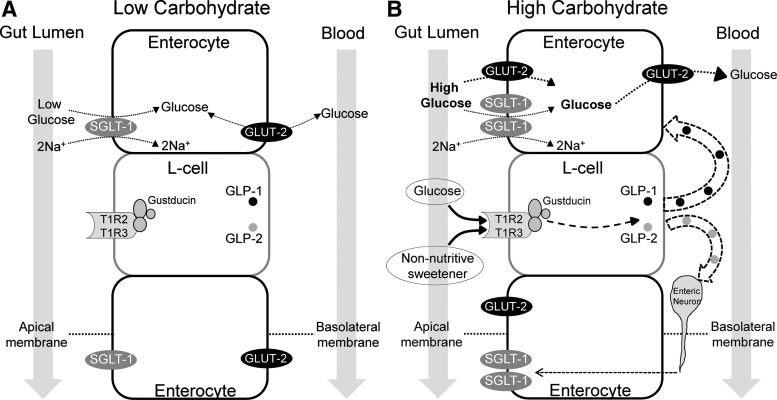

Dietary glucose is absorbed across the enterocytes of the intestinal wall via the active Na+/glucose cotransporter (SGLT-1) on the apical (luminal) membrane and the passive glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2) on the basolateral membrane of the enterocyte (Fig. 1A). In order for intestinal transport to adapt to dietary glucose concentrations, there must be a glucose sensing mechanism present in the gastrointestinal tract; the sweet-taste receptor is one such sensor (13, 24). Glucose binding to sweet-taste receptors on intestinal enteroendocrine cells causes secretion of GLP-1, GLP-2, and GIP, which in turn may act as neural or paracrine signals to nearby enterocytes, causing up-regulation of SGLT-1 (48) (Fig. 1B). Kellett et al. (49) have proposed that intestinal glucose absorption can be further increased at high glucose concentrations (over 30 mm) by insertion of GLUT2 at the apical membrane of the enterocyte. The functional importance of apical GLUT2 in intestinal glucose absorption has been questioned, however, because humans with GLUT2 deficiency (Fanconi Bickel syndrome) do not have significant carbohydrate malabsorption. In contrast, humans with SGLT-1 deficiency (glucose-galactose malabsorption) have severe carbohydrate malabsorption, emphasizing the functional importance of this glucose transporter (50).

Fig. 1.

A model of intestinal glucose absorption in the fasting or low luminal carbohydrate state (A) or after a high-carbohydrate meal, with or without non-nutritive sweeteners (B). In the low luminal carbohydrate state, glucose is largely transported from the gut lumen into the enterocyte via SGLT-1. Glucose may pass in a bidirectional manner between the enterocyte and the bloodstream via GLUT2 located on the basolateral membrane, depending on the plasma glucose concentration and the metabolic needs of the enterocyte. In the presence of high luminal carbohydrate, glucose binds to sweet-taste receptors on enteroendocrine L cells, initiating a signal transduction cascade that results in GLP-1 and GLP-2 release. GLP-2 may cause up-regulation of SGLT-1 via enteric neurons. GLP-1 may act in a paracrine manner on nearby enterocytes to up-regulate apical GLUT2. Non-nutritive sweeteners can also bind to enteroendocrine sweet-taste receptors, causing GLP-1 release (in vitro) and increased intestinal glucose uptake (in rodents).

Margolskee et al. (24) studied the role of non-nutritive sweeteners in the regulation of intestinal glucose absorption in mice, demonstrating that sucralose, acesulfame-K, and saccharin (but not aspartame, which is not sensed as sweet by rodents) up-regulated SGLT-1. This up-regulation resulted in a 1.9-fold increase in SGLT-1-mediated glucose transport measured in vitro. In 2007, Mace et al. (51) showed that these sweeteners could double the in vivo rate of intestinal glucose absorption in rats by increasing GLUT2 insertion into the apical membrane of enterocytes.

The effect of non-nutritive sweeteners on glucose absorption in humans was examined by Ma et al. (41). In healthy adults, they found no difference in intestinal glucose absorption during intraduodenal infusion of 4 mm sucralose vs. saline in combination with glucose. In this study, the rate of intestinal glucose absorption was measured by adding a non-metabolizable glucose analog, 3-O-methyl glucose (3OMG), to the intestinal perfusate. 3OMG is absorbed across enterocytes identically to glucose and is subsequently excreted by the kidney over 48 h (52). Serum levels of 3OMG over 2–3 h after ingestion can thus be used as a proxy for the rate of intestinal glucose absorption. Because this is an indirect measure, however, it may be less sensitive than direct measures of intestinal glucose absorption used in rodent studies. At the current time, there is insufficient evidence to support an effect of non-nutritive sweeteners on intestinal glucose absorption in healthy humans.

Non-Nutritive Sweetener Effects on the Microbiome

Connections between nutrition, gut microbial communities, and specific aspects of our health, such as the function of the immune system and the development of obesity, are under intense investigation (53, 54). A bidirectional influence of nutritional components such as non-nutritive sweeteners on the gut microbiome and vice versa is highly likely. For example, rodent studies have shown that germ-free animals up-regulate their sweet-taste receptors and glucose transporters in the proximal small intestine and preferentially consume nutritive compared with non-nutritive sweeteners (55). Abou-Donia et al. (56) suggested that sucralose may alter the microbiome of rats and furthermore reported that sucralose up-regulated intestinal enzymes important for drug metabolism. To date, there are no published studies in humans examining these questions.

Conclusions

The identification of sweet-taste receptors in enteroendocrine cells, both in the intestinal epithelium and the pancreas, has led to important insights into the mechanisms underlying glucose sensing, glucose transport, and hormone secretion. Non-nutritive sweeteners have allowed researchers to distinguish effects that are mediated via sweet-taste receptors (that bind to non-nutritive sweeteners) from effects mediated by other glucose sensors and transporters, such as SGLT-1. Given the epidemiological data associating non-nutritive sweetener use with weight gain and diabetes, it is intriguing to speculate that intestinal sweet-taste receptors might provide a mechanistic link. Egan and Margolskee (57) proposed that non-nutritive sweeteners binding to intestinal sweet-taste receptors would lead to increased GLP-1 secretion, which in turn would increase insulin secretion and lower blood glucose, and thus increase appetite and induce weight gain. Corkey (43) raised a similar provocative hypothesis in the 2011 Banting Lecture, speculating that non-nutritive sweeteners and other food additives might induce pancreatic β-cell hypersecretion, leading to hepatic insulin resistance and increased fat accumulation, both key components of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Although most in vitro data support the idea that non-nutritive sweeteners can increase hormone secretion by enteroendocrine cells or pancreatic β-cells, the available in vivo data have generally not supported this. In both rodents and humans, non-nutritive sweeteners in the absence of metabolizable sugars have not altered hormone secretion in vivo. When given in combination with metabolizable sugars, non-nutritive sweeteners increased intestinal glucose absorption in rodents, but not humans. One human study showed that non-nutritive sweeteners may increase GLP-1 when given in combination with metabolizable sugars, but this finding needs to be replicated. To date, solid evidence for a clinically relevant role of non-nutritive sweeteners on gut hormones or glucose metabolism in humans remains to be established. Ongoing and future clinical studies will hopefully soon provide answers to the highly relevant questions about the effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on gut hormones, glucose metabolism, and ultimately human weight regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Allison Sylvetsky for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the intramural research program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

- GIP

- Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide

- GLP-1

- glucagon-like peptide 1

- GLUT2

- glucose transporter 2

- 3OMG

- 3-O-methyl glucose

- PYY

- peptide YY

- SGLT-1

- Na+/glucose cotransporter.

References

- 1. Colditz GA, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, London SJ, Segal MR, Speizer FE. 1990. Patterns of weight change and their relation to diet in a cohort of healthy women. Am J Clin Nutr 51:1100–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dhingra R, Sullivan L, Jacques PF, Wang TJ, Fox CS, Meigs JB, D'Agostino RB, Gaziano JM, Vasan RS. 2007. Soft drink consumption and risk of developing cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults in the community. Circulation 116:480–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fowler SP, Williams K, Resendez RG, Hunt KJ, Hazuda HP, Stern MP. 2008. Fueling the obesity epidemic? Artificially sweetened beverage use and long-term weight gain. Obesity 16:1894–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lutsey PL, Steffen LM, Stevens J. 2008. Dietary intake and the development of the metabolic syndrome: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circulation 117:754–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nettleton JA, Lutsey PL, Wang Y, Lima JA, Michos ED, Jacobs DR., Jr 2009. Diet soda intake and risk of incident metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes Care 32:688–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Winkelmayer WC, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Curhan GC. 2005. Habitual caffeine intake and the risk of hypertension in women. JAMA 294:2330–2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stellman SD, Garfinkel L. 1986. Artificial sweetener use and one-year weight change among women. Prev Med 15:195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blackburn GL, Kanders BS, Lavin PT, Keller SD, Whatley J. 1997. The effect of aspartame as part of a multidisciplinary weight-control program on short- and long-term control of body weight. Am J Clin Nutr 65:409–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raben A, Vasilaras TH, Møller AC, Astrup A. 2002. Sucrose compared with artificial sweeteners: different effects on ad libitum food intake and body weight after 10 wk of supplementation in overweight subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 76:721–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tordoff MG, Alleva AM. 1990. Effect of drinking soda sweetened with aspartame or high-fructose corn syrup on food intake and body weight. Am J Clin Nutr 51:963–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Swithers SE, Martin AA, Davidson TL. 2010. High-intensity sweeteners and energy balance. Physiol Behav 100:55–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Montmayeur JP, Matsunami H. 2002. Receptors for bitter and sweet taste. Curr Opin Neurobiol 12:366–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dyer J, Salmon KS, Zibrik L, Shirazi-Beechey SP. 2005. Expression of sweet taste receptors of the T1R family in the intestinal tract and enteroendocrine cells. Biochem Soc Trans 33:302–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakagawa Y, Nagasawa M, Yamada S, Hara A, Mogami H, Nikolaev VO, Lohse MJ, Shigemura N, Ninomiya Y, Kojima I. 2009. Sweet taste receptor expressed in pancreatic β-cells activates the calcium and cyclic AMP signaling systems and stimulates insulin secretion. PLoS One 4:e5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chaudhari N, Roper SD. 2010. The cell biology of taste. J Cell Biol 190:285–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chandrashekar J, Hoon MA, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. 2006. The receptors and cells for mammalian taste. Nature 444:288–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nelson G, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Zhang Y, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. 2001. Mammalian sweet taste receptors. Cell 106:381–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drayna D. 2005. Human taste genetics. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 6:217–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heck GL, Mierson S, DeSimone JA. 1984. Salt taste transduction occurs through an amiloride-sensitive sodium transport pathway. Science 223:403–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whitehouse CR, Boullata J, McCauley LA. 2008. The potential toxicity of artificial sweeteners. AAOHN J 56:251–259; quiz 260–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu H, Staszewski L, Tang H, Adler E, Zoller M, Li X. 2004. Different functional roles of T1R subunits in the heteromeric taste receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:14258–14263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jiang P, Ji Q, Liu Z, Snyder LA, Benard LM, Margolskee RF, Max M. 2004. The cysteine-rich region of T1R3 determines responses to intensely sweet proteins. J Biol Chem 279:45068–45075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McLaughlin SK, McKinnon PJ, Margolskee RF. 1992. Gustducin is a taste-cell-specific G protein closely related to the transducins. Nature 357:563–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Margolskee RF, Dyer J, Kokrashvili Z, Salmon KS, Ilegems E, Daly K, Maillet EL, Ninomiya Y, Mosinger B, Shirazi-Beechey SP. 2007. T1R3 and gustducin in gut sense sugars to regulate expression of Na+-glucose cotransporter 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:15075–15080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steinert RE, Gerspach AC, Gutmann H, Asarian L, Drewe J, Beglinger C. 2011. The functional involvement of gut-expressed sweet taste receptors in glucose-stimulated secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY). Clin Nutr 30:524–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fujita Y, Wideman RD, Speck M, Asadi A, King DS, Webber TD, Haneda M, Kieffer TJ. 2009. Incretin release from gut is acutely enhanced by sugar but not by sweeteners in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296:E473–E479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Toyono T, Seta Y, Kataoka S, Toyoshima K. 2007. CCAAT/Enhancer-binding protein β regulates expression of human T1R3 taste receptor gene in the bile duct carcinoma cell line, HuCCT1. Biochim Biophys Acta 1769:641–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Finger TE, Kinnamon SC. 2011. Taste isn't just for taste buds anymore. F1000 Biol Rep 3:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gerspach AC, Steinert RE, Schönenberger L, Graber-Maier A, Beglinger C. 2011. The role of the gut sweet taste receptor in regulating GLP-1, PYY, and CCK release in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 301:E317–E325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jiang P, Cui M, Zhao B, Liu Z, Snyder LA, Benard LM, Osman R, Margolskee RF, Max M. 2005. Lactisole interacts with the transmembrane domains of human T1R3 to inhibit sweet taste. J Biol Chem 280:15238–15246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schiffman SS, Booth BJ, Sattely-Miller EA, Graham BG, Gibes KM. 1999. Selective inhibition of sweetness by the sodium salt of +/−2-(4-methoxyphenoxy) propanoic acid. Chem Senses 24:439–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jang HJ, Kokrashvili Z, Theodorakis MJ, Carlson OD, Kim BJ, Zhou J, Kim HH, Xu X, Chan SL, Juhaszova M, Bernier M, Mosinger B, Margolskee RF, Egan JM. 2007. Gut-expressed gustducin and taste receptors regulate secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:15069–15074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reimann F, Habib AM, Tolhurst G, Parker HE, Rogers GJ, Gribble FM. 2008. Glucose sensing in L cells: a primary cell study. Cell Metab 8:532–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Parker HE, Habib AM, Rogers GJ, Gribble FM, Reimann F. 2009. Nutrient-dependent secretion of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide from primary murine K cells. Diabetologia 52:289–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ford HE, Peters V, Martin NM, Sleeth ML, Ghatei MA, Frost GS, Bloom SR. 2011. Effects of oral ingestion of sucralose on gut hormone response and appetite in healthy normal-weight subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 65:508–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brown AW, Bohan Brown MM, Onken KL, Beitz DC. 2011. Short-term consumption of sucralose, a nonnutritive sweetener, is similar to water with regard to select markers of hunger signaling and short-term glucose homeostasis in women. Nutr Res 31:882–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ma J, Bellon M, Wishart JM, Young R, Blackshaw LA, Jones KL, Horowitz M, Rayner CK. 2009. Effect of the artificial sweetener, sucralose, on gastric emptying and incretin hormone release in healthy subjects. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 296:G735–G739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Steinert RE, Frey F, Töpfer A, Drewe J, Beglinger C. 2011. Effects of carbohydrate sugars and artificial sweeteners on appetite and the secretion of gastrointestinal satiety peptides. Br J Nutr 105:1320–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brown RJ, Walter M, Rother KI. 2009. Ingestion of diet soda before a glucose load augments glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Diabetes Care 32:2184–2186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brown RJ, Walter M, Rother KI. 2012. Effects of diet soda on gut hormones in youths with diabetes. Diabetes Care 35:959–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ma J, Chang J, Checklin HL, Young RL, Jones KL, Horowitz M, Rayner CK. 2010. Effect of the artificial sweetener, sucralose, on small intestinal glucose absorption in healthy human subjects. Br J Nutr 104:803–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu T, Zhao BR, Bound MJ, Checklin HL, Bellon M, Little TJ, Young RL, Jones KL, Horowitz M, Rayner CK. 2012. Effects of different sweet preloads on incretin hormone secretion, gastric emptying, and postprandial glycemia in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr 95:78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Corkey BE. 2012. Banting lecture 2011. Hyperinsulinemia: cause or consequence? Diabetes 61:4–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Abudula R, Matchkov VV, Jeppesen PB, Nilsson H, Aalkjaer C, Hermansen K. 2008. Rebaudioside A directly stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells: a glucose-dependent action via inhibition of ATP-sensitive K-channels. Diabetes Obes Metab 10:1074–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Abudula R, Jeppesen PB, Rolfsen SE, Xiao J, Hermansen K. 2004. Rebaudioside A potently stimulates insulin secretion from isolated mouse islets: studies on the dose-, glucose-, and calcium-dependency. Metabolism 53:1378–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jeppesen PB, Dyrskog SE, Agger A, Gregersen S, Colombo M, Xiao J, Hermansen K. 2006. Can stevioside in combination with a soy-based dietary supplement be a new useful treatment of type 2 diabetes? An in vivo study in the diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rat. Rev Diabet Stud 3:189–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gregersen S, Jeppesen PB, Holst JJ, Hermansen K. 2004. Antihyperglycemic effects of stevioside in type 2 diabetic subjects. Metabolism 53:73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shirazi-Beechey SP, Moran AW, Batchelor DJ, Daly K, Al-Rammahi M. 2011. Glucose sensing and signalling; regulation of intestinal glucose transport. Proc Nutr Soc 70:185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kellett GL, Brot-Laroche E, Mace OJ, Leturque A. 2008. Sugar absorption in the intestine: the role of GLUT2. Annu Rev Nutr 28:35–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wright EM, Loo DD, Hirayama BA. 2011. Biology of human sodium glucose transporters. Physiol Rev 91:733–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mace OJ, Affleck J, Patel N, Kellett GL. 2007. Sweet taste receptors in rat small intestine stimulate glucose absorption through apical GLUT2. J Physiol 582:379–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fordtran JS, Clodi PH, Soergel KH, Ingelfinger FJ. 1962. Sugar absorption tests, with special reference to 3–0-methyl-D-glucose and D-xylose. Ann Intern Med 57:883–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kau AL, Ahern PP, Griffin NW, Goodman AL, Gordon JI. 2011. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature 474:327–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jumpertz R, Le DS, Turnbaugh PJ, Trinidad C, Bogardus C, Gordon JI, Krakoff J. 2011. Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 94:58–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Swartz TD, Duca FA, de Wouters T, Sakar Y, Covasa M. 2012. Up-regulation of intestinal type 1 taste receptor 3 and sodium glucose luminal transporter-1 expression and increased sucrose intake in mice lacking gut microbiota. Br J Nutr 107:621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Abou-Donia MB, El-Masry EM, Abdel-Rahman AA, McLendon RE, Schiffman SS. 2008. Splenda alters gut microflora and increases intestinal p-glycoprotein and cytochrome p-450 in male rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A 71:1415–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Egan JM, Margolskee RF. 2008. Taste cells of the gut and gastrointestinal chemosensation. Mol Interv 8:78–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. DuBois GE, Walters DE, Schiffman SS, Warwick ZS, Booth BJ, Pecore SD, Gibes K, Carr BT, Brands LM. 1991. Concentration—response relationships of sweeteners. In: Walters DE, Orthoefer FT, DuBois GE, eds. Sweeteners—discovery, molecular design, and chemoreception. Chap 20 Washington DC: American Chemical Society; 261–276 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schiffman SS, Sattely-Miller EA, Bishay IE. 2008. Sensory properties of neotame: comparison with other sweeteners. In: Deepthi K, Weerasinghe DK, DuBois GE, eds. Sweetness and Sweeteners. Chap 13 Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 511–529 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Huvaere K, Vandevijvere S, Hasni M, Vinkx C, Van Loco J. 2012. Dietary intake of artificial sweeteners by the Belgian population. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 29:54–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]