Abstract

We describe one approach for recruitment and retention of minority individuals in intervention research using a systematic environmental perspective based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems (BES) model and the construct of temporality. An exemplar in a physical activity intervention study with low-income and primarily African American women is presented. The exemplar illustrates application of BES and temporality to enhance recruitment and retention in research focused on understanding and accommodating environmental influences. . Using this theory based approach resulted in successful recruitment and a high level of participant retention.

Keywords: Health disparity research, research methods, minority recruitment, theory application

Research literature on recruitment and retention strategies with minority populations in health care research has focused on successful techniques, identification of barriers to recruitment, or lessons learned from the recruitment and retention process. Most of this literature provides observations and recommendations related to discrete activities developed for the projects of interest. The targeted minority communities’ structure and day-to-day processes, as a system into which research must be incorporated, have received little attention. Our purpose in this article is to discuss the importance of understanding the structure, or systems, of a community and its day-to-day processes, or rhythms, as a foundation for choosing appropriate recruitment and retention approaches and effectively timing those approaches. An example of an a priori application of a cohesive theoretical framework to the conduct of recruitment and retention is presented.

Issues Related to Minority Participation in Health Care Research

As minority health is increasingly being emphasized, elucidating factors that function as barriers to inclusion of minority populations in research also has increased (Harden & McFarland, 2000; Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Interpersonal barriers include lack of trust of the medical and scientific community (Byrd & Clayton, 2001; Levkoff, Prohaska, Weitzman, & Ory, 2000), failure to actively recruit minorities, lack of health care provider participation, and language and cultural influences (Gallagher-Thompson, Solano, Coon, & Arean, 2003; Giuliano, et al., 2000; Lemon, Zapka, Estabrook, & Benjamin, 2006). One economic barrier relates to the cost of recruitment of minority populations (USDHHS, 2000). In addition, the study design and methods, and their impact on participants can also be barriers, particularly in intervention research (Adams-Campbell et al., 2004; Davis, Broome, & Cox, 2002; Jansen, Alioto, Boushey, & Asthma Clinical Trials Network, 2001).

Facilitators of inclusion of minority populations in research have been developed in response to recognition of barriers. Strategies such as trust-building, outreach and ease of access, language compatibility, and cultural congruency of recruiters and potential participants have been identified (Heiney et al., 2006; Qualls, 2002; Silvestre et al., 2006; Swanson & Ward, 1995). However, progress toward adequate representation of minority populations in research has been slow. Minority recruitment into clinical trials has been reported to be as low as 3% to 22% of the total sample even when many minority groups experience higher rates of disease specific morbidity and mortality (Adams-Campbell et al., 2004; Giuliano et al., 2000; McCaskill-Stevens, McKinney, Whitman, & Minasian, 2005).In this article we propose that minority recruitment and retention in research could be more appropriately accomplished if a comprehensive view of human behavior is adopted, taking into account the appropriateness of each strategy to a given environment or point in time. From the human behavior perspective, each potential minority participant is a member of a community that has a life context and structure (or system) and pattern of interaction (or rhythm). These systems and rhythms influence life choices, including the choice of whether to participate in research (Guiliano et al., 2000; Resnicow, Baranowski, Ahluwalia, & Braithwaite, 1999).

Systems Theory, Community Rhythm, and the Conduct of Research

Systems Theory

In his general systems theory, Von Bertalanffy (1976) identified organisms in interaction with others as part of the essentials of life processes. Systems theory is focused on the arrangement of, and relations between, the parts that connect them into a whole.

Bronfenbrenner (1979) further refined Von Bertalanffy’s systems theory in his bioecological (or ecological) systems (BES) theory. He theorized that individuals have multiple layers of interactions with others and their environment that may be determined by the context of each situation they encounter. These layers include: (a) the microsystem, which is the immediate environment in which a person operates (e.g., family, friends); (b) the mesosystem, which is the process of multi-system interaction as individual or groups experience layers of context (the interaction of individuals across different, and sometimes less familiar, microsystems); (c) the exosystem, which is an environment in which most individuals are not routinely a part of, but which nonetheless affects the individual (e.g., governmental or organizational entities); and the (e) macrosystem, or the larger cultural/social context (e.g., shared political, historical or social policy contexts of a given society). Each of Bronfenbrenner’s systems is characterized by roles; cultural, behavioral, and temporal norms; and relationships. The BES is depicted as spheres of influence affecting multiple aspects of the individual’s life. A macrosystem involves any group whose members share value or belief systems, resources, hazards, lifestyles, opportunity structures, life course options and patterns of social interchange (Bronfenbrenner, 1993). Although the systems influence each individual, individuals also influence their environments. According to Bronfenbrenner (1989, 1993), individuals influence their environment based on their belief system (including those derived from racial and ethnic membership), activity level, temperament, goals and motivations. All of these personal stimulus characteristics influence how the context is experienced by the individual and the types of contexts to which the individual may be drawn.

Time, Temporality and Community Rhythms

Bronfenbrenner (1989, 1993) and other theorists also have identified time (or temporality) as a critical element when examining individuals within their environments. Culture is a shared system of ideas about the nature of the world, and when and how people should behave in it (Leininger & McFarland, 2002, 2005). These shared ideas are the core of the microsystems (or communities) to which an individual belongs. The shared idea of “when behaviors occur” relates to uses and perceptions of time or temporality within a culture. Condon and Sander (1974) observed that by the time children are 3 months old they have already been temporally enculturated, having internalized the external tempo or rhythms of their culture. These rhythms underlie such things as people’s language, music, religious ritual, and daily living. Humans are universally attracted to rhythm, and to those who share their cadence of talk, movement, and pace of daily living. Cultures (as reflected within their microsystems) differ in the temporal precision with which they program everyday events and in ways various social rhythms are allowed to mesh. Differences in perceptions and use of time can be viewed on a continuum with the poles identified as polychronic and monochronic. Polychronic time is oriented toward involvement with people and completion of life transactions, or commitments related to those people, rather than adherence to preset schedules. This temporal orientation has been more closely aligned with minority and indigenous populations that demonstrate fluidity of time and people-oriented perspectives. Monochronic time is oriented toward tasks, schedules, and procedures. Monochronic time is also tangible. Time is spoken of as being saved, spent, wasted, lost, made up, crawling, killed, and running out (Hall, 1983). This latter orientation to time has been more closely associated with industrialized populations and organizations.

Individuals and systems establish institutions that possess temporal rhythms at a variety of levels that function to modify natural rhythms of the body such as circadian rhythms. The controls established by systems and subsequently placed on the social rhythms of life processes are called entrainment (McGrath & Kelly, 1986). Entrainment is most clearly exhibited in systems such as schools, business, and health care. International societies, scientific disciplines, and the U.S. government target the measurement and examination of the influence of temporality (including entrainment) on perception, daily functioning, and social rhythms of life (Bergmann, 1992; Cicchelli, Pugeault-Cicchelli, & Merico, 2006). One ongoing example of this focus on temporality in a social context is the U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (2008) survey of American time use. To fully understand human behavior and how humans organize and conduct their lives, it is necessary to examine the temporality and rhythms of that environment or microsystem. Just as governments and international societies have identified the importance of time, temporality, and human rhythm in the lives of diverse groups, so should health care researchers. Investigators should assess their own temporal orientation in the planning and conduct of research to better accommodate the orientations of the culturally diverse populations they hope to recruit and retain.

Application of BES and Temporality in Planning Research

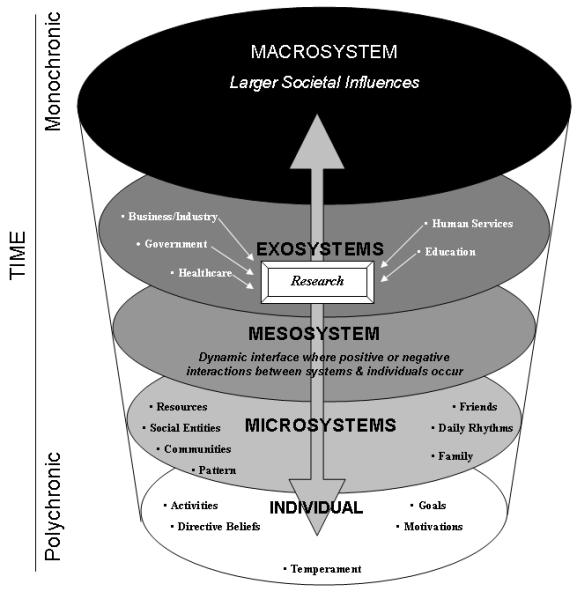

Although BES is focused on human development over the life span and has been applied to human development research, we found no evidence of its application to the conduct of research, specifically for designing recruitment and retention. Figure 1 illustrates the application of Bronfenbrenner’s environmental system constructs as they might be applied to the conduct of research within a multidimensional context. To achieve congruence with individuals who are the focus of research recruitment and retention, each layer of context must be examined, understood, and appropriately navigated. Figure 1 depicts the following process as it relates to research. Individuals (each with their own personal stimulus characteristics) are an integral part of their multidimensional microsystem. Research can be seen as a component or microsystem in many exosystems; one of which is the health care system. This health care exosystem affects individuals indirectly until they are sought out as potential research participants. The dynamic interface (mesosystem) that occurs between an investigator and an individual as part of the research process can be positively or negatively influenced by the congruence between the two systems. Mesosystem incongruence can result in barriers to inclusion of minority populations in the areas of interpersonal dynamics, language, and cultural values among other factors. The more deliberately and systematically an investigator acquires knowledge about the microsystems to which potential participants belong, the greater the possibility that the research context can be constructed to be compatible with the perspectives of those who are the focus of the research; hence, greater participation and retention may result. Research recruitment and retention planning should include each of the previously discussed system dimensions. Table 1 column 1 provides a summary of relevant questions that should be considered during recruitment planning using the BES approach.

Figure 1.

Model of the environment: A schematic diagram of the system levels for research Adapted from Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) Ecological Systems Theory & Temporality.

Table 1.

System Considerations and Research Recruitment/Retention Strategy Development

| Environmental System Factors |

Observations/Considerations that Emerged from the Setting |

Recruitment Needs and Activity |

Retention Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Which microsystems do the targeted group members (that are the focus for research recruitment or intervention) belong? |

Three (3) contiguous, low-income primarily African American communities were identified for the targeted population. Only two of the three communities had ongoing relationships (use of activities and services) with the centrally located community center chosen as the setting for the study. The setting for the study was situated within walking distance to a large public housing complex. |

Recruitment strategies focused on the two communities with established relationships with the chosen community setting |

Retention in both cohorts centered on starting and strengthening friendships among the women using the community first then the center as a common focal point |

| 2. What is known about that microsystem (structure and processes)? |

Women targeted for the study (ages 18-64) in the two relevant communities had very limited interaction with the chosen community center. Women did have other established community activities in which they were involved and daily activities during which they could routinely be contacted. |

Recruitment focused on the systems in which women are currently involved. Strategies developed to cultivate interest in the study setting for all phases of the study. |

Phase 1 participants identified intervention interests, constraints and facilitated knowledge in community women about resources at the community center. Strategies enhanced retention during the intervention and increased subject participation in activities and events. |

| 3. Does the investigator’s exosystem impact, or interact, (directly, indirectly, or not at all) with the targeted group? What can be said about the mesosystem dynamics? |

Targeted community had no ongoing formal interaction with the university conducting the research. Select community members used health care services located on the university health sciences campus and those services were not perceived as user friendly. The school of nursing that undertook the research was in the initial stages of establishing a presence within the chosen setting |

Recruitment strategies could not be built on the history of the university’s relationship with the community residents. A series of strategies were developed to foster positive relationships prior to recruitment efforts. |

Retention strategies involved research team members accepting and valuing differences. Scheduling of appointments was flexible and recognition of the impact of external factors on subjects’ daily lives unrelated to the study were validated and accepted. Social and educational opportunities were combined as part of study protocol. PI was integrally involved. |

| 4. How does that mesosystem interaction affect the desired outcome to recruit or intervene? |

No foundation on which to build for recruitment and intervention. |

Planned connections with the community would be two pronged - through study team members who were also community members, and through increased visibility and commitment of the investigators in non-study related situations. |

Trust building continued during the six month period each group participated in the study. The PI and research team continued visibility at physical activity sessions and in community activities unrelated to the study. |

| 5. What strategies would be most effective for access, recruitment, retention and intervention in the microsystem of interest? (What mesosystem processes must be in place)? Where would the strategies be most effective for access, recruitment, retention and intervention in the microsystem of interest? |

Because study setting activities and services did not target women, recruitment through the setting would be minimal. The lack of connection would also function as a barrier to ongoing use of the setting by community women. |

The recruitment team, with the assistance of graduate nursing students, walked each block of the two target communities. Women were observed during their daily patterns: taking their children to and from the school bus, going to local stores, paying rent at the public housing office. Study team members introduced themselves to individuals in their natural settings. Social interaction, and distribution of information about the study setting and the planned project, took place sequentially during these activities |

The PI and study team members who implemented the intervention demonstrated genuine interest in the lives of subjects not only during the study (newsletter updates, in person activities), but in continued contact with participants after the research was completed. This positive mesosystem interface supports future interaction between the research exosystem and the individual/microsystem. |

As investigators plan health care research that includes culturally and racially diverse individuals, they must also understand the temporal rhythm of the individual’s personal and community lives that may affect recruitment and retention approaches. Figure 1 depicts the potential variations in temporal perspectives between minority communities and formal systems. In addition, the temporal perspectives of the investigator(s) must be critically analyzed to identify potential areas of (in) compatibility that may affect recruitment and retention of study participants. Relevant temporality considerations are summarized in Table 2 column 1.

Table 2.

Temporality Considerations & Research Recruitment/Retention Strategy Development

| Temporality Factors |

Observations/ considerations that emerged from the setting |

Recruitment Needs & Activity |

Retention Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Is the overall temporal perspective of the targeted group monochronic or polychronic? |

When possible, community women preferred the polychronic temporal perspective. Meeting the needs of family was uppermost and time was fluid around those needs. |

Interactions with community women in a variety of circumstances used to support an understanding of this temporal perspective. Study team members functioned as participant observers for over 40 hours. |

Study data collection and intervention strategies were developed to address identified temporal needs |

| 2. What are the daily rhythms of the targeted population and what are important community patterns? |

Daily rhythms involved multiple activities around child care, work, and meeting the changing needs of daily living – shopping, using public transportation, obtaining needed services and resources reflecting polychronic perspective. With the bulk of activity related to child care, activities outside the home for mothers of children younger than 5 years began later in the day (11 am – 1 pm). Activities for mothers of school age children began with the visit to the bus stop (as early as 6:30 am). Older women without children had daily patterns that centered around work schedules and friends. For all women, most activity outside the home decreased at sundown. Significant involvement during community fairs and holiday events. Community activity was also influenced by the time of the month, with more activity on pay days. |

The recruitment strategies described below resulted from the synthesis of temporal factor observations and considerations (items 1 through 5). Recruitment took place during the afternoons at the bus stops. Mothers of school aged children lingered and socialized more freely then, than during early morning when mothers placed children on the bus. Mothers of children under age 6 were met in the community as they began their community activities in the late mornings – as they went to laundromat, etc. Recruitment sessions were set up outside the community dollar store on pay days when a variety of women were available. Give-aways from the store were distributed to those who listened to the recruitment information. |

Intervention activities were scheduled during times women had identified as most convenient, generally late afternoon and early evening for working and parenting women. Children were involved in walking activity and child care was provided to meet the daily needs of mothers. |

| 3. What are the temporal values of the investigators? |

The majority of the study team functioned primarily using the monochronic temporal perspective, assuming responsibility for multiple tasks with specific timelines. |

Information was provided at a variety of community locations including transitional housing, churches and day care centers. As community women became familiar with the recruitment team, women were invited to informational sessions situated in the community center setting. Informational sessions were set up based on schedules that allowed mothers to attend and bring their children. Breakfast/lunch/snacks were offered. These informational sessions requested RSVP’s to plan for meals and space needs, any woman who could not attend was not perceived as exhibiting a lack of interest. With the understanding of variations in temporal perspective and family needs, study team did personal follow-up when possible. |

Strategies such as flexible scheduling, although difficult from a quantitative research team perspective, demonstrated respect for subjects’ need to prioritize intervention activities with commitments that impacted their lives on a daily basis. Using telephone, written and in person approaches to better address entrainment barriers to participation in the study. Contact was maintained for both groups with three newsletters during the six months; intervention participants received activity schedules one or two times per month. Phone call reminders were made before any data collection point. |

| 4. What aspects of entrainment are integral to both the targeted population and the investigative organization that must be addressed for successful interaction? |

Community women were limited in time availability because of children’s school schedules, the most commonly used form of transportation (public transportation), daylight hours (related to safety issues), work schedules and availability of child care, which was primarily done by family and friends. Investigators were constrained by the research funding period, timeline for subject recruitment, time commitment for other academic responsibilities, and cyclical availability of students as study team members. |

||

| 5. What strategies are needed to adapt the research plan to the population temporal rhythms? |

Research team meetings occurred prior to each decision made during the process. Recruitment schedules developed to address community (fairs, events) and individual rhythm needs as identified. Consensus obtained within study team that project strategies would be perspectives of community women. |

An Example from the Field

We used the BES and temporality framework as theoretical bases to plan and conduct recruitment and retention in an intervention study aimed at increasing physical activity in low income women. Detailed description of, and findings from, this study are reported elsewhere (Speck, Hines-Martin, Stetson, & Looney, 2007). The purpose of the study was to decrease environmental barriers in order to promote physical activity in a sample of low-income, primarily African American women who were at high risk for health and social disparities. The study intervention was guided by Pender, Murdaugh, and Parson’s (2006) health promotion model, in which variables of individual characteristics and experiences, behavioral cognitions and affect, immediate coping demands, and commitment to action interact to influence specific health-promoting behavioral outcomes. We adapted the model to include the following variables: the influence on physical activity of individual characteristics (demographics, biobehavioral variables), behavior-specific cognitions (self-efficacy, barriers and benefits of physical activity), interpersonal support (friends, family, and nurse practitioner support), situational influences (physical activity options, perceptions of physical activity environment to promote physical activity), and immediate competing demands (lack of childcare). A cohort design, which controlled for the setting, was planned with two convenience cohorts of 50 participants each. The study was conducted in two sequential 6-month phases. The comparison group, cohort 1, was recruited in Phase 1, and cohort 2, the intervention group, was recruited in Phase 2. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses were undertaken to determine the effectiveness of the physical activity intervention.

Study Sample and Setting

The study target population consisted of women from three intersecting low income inner-city communities that were 65% African Americans, 34% White, and 1% other racial and ethnic groups. The communities from which the sample was drawn were all located within 1 – 3 miles of a university health sciences center in a southern urban city that included a school of nursing. Many of the members of these communities had received health care from the health sciences center. The communities experience significant disparities in health and economic status. Health problems in the target population include cardiovascular disease and diabetes. African Americans in the community have age adjusted death rates higher than Whites for cardiac diseases (291.1 versus 227/100,000) cardiovascular accidents (CVA; 73.6 versus 49.1/100,000) and diabetes (67.3 versus 30.3/100,000; Louisville Metro Public Health and Welfare, 2008).

In addition, members of the targeted communities had one of the highest homeless rates within the city (Coalition for the Homeless, 2009a). Homeless rates for zip codes within the identified communities have been estimated according to the percentage of people seeking emergency shelter (9% versus less than 5% city wide), and 34% reported not having a permanent home (residing with family or friends). Homelessness requiring emergency shelter and residing with others resulted from lack of affordable housing, low paying jobs and poverty. Of the six homeless shelters within the city, five are located within the three communities from which the study sample was drawn (Coalition for the Homeless, 2009b; U. S. Conference of Mayors, 2008). Nearly 75% of the sample reported annual family income below $20,000 in a city with a median income of >$40,000 (Speck et al., 2007).

The chosen setting for the study was a church sponsored community center that had been designated to serve the targeted neighborhoods. The community center had a gymnasium, exercise and weight room, administrative offices and a newly established nurse practitioner clinic. Services that were provided to the communities included activities for children, senior nutrition, food distribution for low income families, and an open gym for adults.

Study Procedure – Phase 1

Although the communities were served by the university health services, there had been no previous research conducted by the school of nursing within these community settings. Because of this lack of history, the research was developed to be conducted in two phases. Phase 1 involved the development of recruitment team, composed of a co-investigator, in addition to an African American nurse familiar with the target population, and two women who were long-standing community members.

Phase 1 activities began with periods of observation in the community setting and discussions with community center personnel to improve the investigators’ understanding of who used the community center services and when. It became increasingly clear that only two of the three communities felt a connection with or used the community center routinely. In addition, none of the activities and services provided by the center incorporated or directly targeted community women. Therefore, the recruitment team, with assistance from nursing graduate students, walked every block of the two relevant communities at different times of the day and different days of the week to better understand when and where community women could be found in their daily lives. During these times one or more of the following activities were conducted: team members introduced themselves, held social conversations, and learned women residents’ views of the community and the community center. We thereby gained an understanding of the systems and rhythms of the community. In addition, community women became familiar with the recruitment team.

Research team members’ involvement in the community gradually became more synchronous with community rhythms and interactions. Community women were informed of new initiatives at the center and were provided with recruitment flyers including pictures of the research team. The recruitment team then undertook usual recruitment activities, such as meeting with women’s groups in the communities and recruitment at community fairs. The recruitment process involved multiple stages to improve the research teams’ understanding of the mesosystem dynamic, microsystems, and community rhythm prior to recruitment efforts. As a result of this process, 53 participants from 18 to 63 years old (72.3% African American, 19.1% Caucasian, 8.5% American Indian) were recruited in Phase 1 for the comparison cohort of the study. Tables 1 and 2 (columns 1 and 2) illustrate the use of systems and temporality considerations that guided recruitment activities in the research recruitment phase and resulted in successful recruitment. Participants recruited into the study participated as a comparison cohort and served as experts about their communities and the needs of community women in focus group discussions.

Focus groups were conducted with study participants at the end of the recruitment period during Phase 1. Because of the wide age range of the women, focus groups were divided into two age groups, 18-39 and 40-63. The focus groups facilitated further understanding of the microsystems to which participants belonged and temporal factors that influenced their day to day lives. Use of focus groups helped to further identify potential mesosystem issues that might affect study intervention development and application. The understanding of the community gained during the recruitment period and the focus groups functioned as a foundation for retention approaches that considered culture (detailed in phase 2 discussion) and were uniquely tailored to the community processes and community rhythms for which they were developed.

Information gathered in phase 1, provided an understanding of the women’s community and culturally-based beliefs as described by Resnicow et al (1999), who differentiated a surface structure from a deep structure understanding of culture. Surface structure understanding is focused on the avoidance of obvious bias and the fostering of acceptability in relation to a chosen methodological approach. Generally accepted recruitment and retention techniques address this level of structure. Deep structure understanding adds assessment of the contextual and environmental forces that influence individual’s daily lives. The concept of deep structure understanding is more congruent with the definition of cultural competence as presented by the National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC, 2009). The NCCC defined cultural understanding as resulting from adaptation to populations and their communities to effectively and collaboratively work with diverse populations. Through that deeper understanding, investigators acquire the tools to develop methodologies that reflect what is critical to community women and supports the women’s willingness to invest in the ongoing process. The objective of the theory-based approach we used was to gain a deep-structure understanding of the women in this community. Through our process, we gained an understanding of such things as temporal perspectives, patterns of activity that reflected individual and community behaviors, and differing values according to age group related to social interaction. The insights we gained as a result of this described process also benefited the intervention phase of the research project.

Study Procedures – Phase 2

Following Phase 1, recruitment for the intervention cohort began. Fifty-one women 18 to 60 years old (88.2% African American; 9.8% White; 2.0% American Indian) were recruited into the intervention cohort. Participants were primarily recruited through positive word-of-mouth generated from the approach in phase 1 and snowballing. Recruitment was completed in <3 months. The multi-faceted, 6-month, nurse-facilitated intervention included physical activity opportunities, child care, newsletters, and social and educational sessions (Speck et al., 2007). Data collected in focus groups during Phase 1 also influenced when those intervention strategies would be offered and which activities to target to a particular age-related subgroup. There were six scheduled physical activity opportunities available each week and all were scheduled to accommodate the temporal orientation of the community women. The sessions were tailored to the current physical activity level of each woman. Supervised activities included walking laps, treadmill, stationary bicycle, balance ball, and strength and flexibility training. Low-impact and dance aerobic classes also were available.

Younger participants requested more active dance/hip-hop sessions, which were added to the schedule. Two opportunities for neighborhood group walks were initiated from the community center and conducted weekly during daylight hours to address safety issues. Women were encouraged to bring children on the walks. The research project provided child care during all other intervention activities.

Within this community setting, sharing experiences among women was a valued cultural norm. Three newsletters were mailed to subjects during the 6 month intervention period. Newsletters provided information about study activities and data collection, and they kept participants connected to each other and to the research team. General news about the community and about participant accomplishments was incorporated. This approach further supported the functioning of the microsystem and mesosystem dynamics as participants were involved in research activities. Social and educational opportunities provided dedicated times for study participants to interact with their cohort and the research team and were an important component of retention. One session was conducted during which study participants’ needs were addressed through discussion of health issues, access to care, and medication problems. At the annual health fair held at the community center, study participants were involved in a demonstration of their aerobic dance sessions, which allowed sharing between the women and the community in a valued setting. Using a strategy that combined social and educational components, members of the research team and study participants went to a store (gift cards provided), to compare nutritional value of various foods, and to see how many steps each took during the trip. This activity supported mesosystem interactions and demonstrated how interventions could be incorporated into their life rhythm. Activities related to the study that were not a part of the planned intervention, but supported retention, included frequent mailings of the physical activity schedule, visibility of the principal investigator at weekly research activities, and involvement of the research team in community (microsystem) activities (e.g., nurse-managed health clinic at the community center, community picnic, community award dinner). As a result of the observations and focus groups conducted in Phase 1, we became knowledgeable about community patterns, and women’s usual patterns of activity and multiple roles. We incorporated that knowledge into activities that addressed the context and rhythm experienced by these women, and thereby enhanced positive mesosystem dynamics. Tables 1 and 2 (column 3) illustrate the use of systems and temporality considerations that guided retention efforts in Phase 2 of the study.

Process Outcomes

In-depth understanding of the community systems, processes, and temporal patterns contributed to successful recruitment and retention. The retention rate was 81.7% at 6 months, with higher retention for the comparison cohort (88.7%) compared to the intervention cohort (74.5%). In the comparison cohort, 47 women completed the study, and 6 did not. Five women were lost to follow-up due to relocation; one woman withdrew from the study for unknown reasons. The race/ethnicity of women who completed the study was 73.9% African American, 19.6% Caucasian, and 6.5% American Indian. In the intervention cohort, 38 women completed the study, and 13 did not. Nine were lost to relocation; three withdrew for unknown reasons; and one died of causes unrelated to the study. The race/ethnicity of women in the intervention cohort who completed the study was 86.8% African American, 10.5% Caucasian, and 2.6% American Indian. Three of the 4 participants who withdrew for unknown reasons were from the intervention cohort. Even with the activity involved in the protocol, approximately 75% (n=38) of the intervention cohort was retained.

A review of comparable studies indicated that our study retention rate was comparable to that of other studies focused on physical activity in minority and low income women in community settings. Researchers of comparable studies have reported retention rates from 65 to 79% (see Table 3). In a study similar to ours, Albright et al. (2005) had a retention rate of 74%. In a longitudinal study with postpartum low-income women, Walker et al. (2004) reported a retention rate of 67.5% at 12 months. In a dietary intervention with a physical activity component, French, Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Jeffrey (1998) reported a retention rate of 65% at 8 weeks. None of these researchers reported additional attention to recruitment and retention as described in this paper.

Table 3.

Comparison of Retention Rates in Physical Activity Studies with Women.

| Authors | Sample - Baseline |

Intervention /Control N = |

Intervention | Intervention Length |

Data collection points after baseline |

n at 6 months |

Percent Retained at 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speck et al., 2007 |

N = 104 AA – 80.6%; Annual income <$20,000 = 74% |

53/51 | Environment barriers reduced; physical activity opportunities provided |

6 months | 6 months | 47/38 Total = 85 |

47/53 = 88.7%* 38/51 = 74.5% ** 85/104 = 81.7% |

| Albright et al., 2005 |

N = 113 Latina - ~70%; Annual income <$20,000 = 75% |

Phone + group/35; group/37; No control |

group classes; two home intervention randomized groups |

8 weeks of Classes; 10 months home (72 randomized to two groups) |

10 weeks; 6 months; 12 months |

n at 6 months not stated |

74% of randomized women completed energy expenditure measure At 12 months 79%* |

| French et al., 1998 |

N = 55 Low income women |

Two treatment groups; no control |

Weight loss treatment groups – one received incentive coupons; All were provided physical activity opportunities |

8 weeks | 8 weeks |

N = 36 at 8 weeks |

8 weeks = 65%* |

| Walker et al., 2004 |

N = 382 Low income post-partum women |

Longitudinal study; Baseline – after delivery |

No intervention -Data collected - psychosocial and behavioral variables including physical activity |

6 weeks 3 months 6 months 12 months |

n at 6 months not reported |

12 mo = 67.5%

+ (N at 12 months = 258 data collected at all five points) |

control

intervention

non-experimental

A theory-based understanding of the community additionally resulted in unplanned lasting community benefit. Community members identified the importance of continuing physical activity sessions at the community center after the completion of the study. The women who took part in the study joined with others to seek funds to continue support for the study physical activity leader. As a result, financial support was obtained from the public health department and a community agency to continue the women’s physical activity sessions for 2 ½ years following study completion.

Conclusion

Researchers have lamented the difficulty of recruiting and retaining minority participants into health care research and identified validated techniques for research recruitment and retention. These techniques have been presented as discrete activities to be applied without consideration of when and how they may be most appropriate. In addition, discussion of these activities are generally from a post hoc analysis or “lessons learned” perspective. However, it has become increasingly acknowledged that culturally competent approaches must include an understanding of the characteristics, experiences, norms, values, beliefs, behavioral patterns, social and environmental forces of the population of focus. Resnicow, Braithwaite, Ahluwalia, and Baranowski (1999) stated that incorporating strategies to address social and environmental forces identified as critical to potential participants, resonates within the communities and encourages community members to claim and sustain projects as their own. Our approach resulted in one such outcome.

The perspectives and strategies we have described are congruent with Keller, Gonzales and Fleuriet’s (2005) discussion of treatment theory as a strategy to retain minority women in studies of physical activity. They too described the need to consider the participants’ perspectives and their social context to improve retention. They too observed that a guiding theoretical framework enhanced retention success regardless of the study’s outcome. We add, in addition, consideration of the concept of temporality. There is a continued need better to understand what theoretical perspectives are applicable to these purposes, what potential variations are needed for specific populations, and which perspectives work to address methodological needs and to provide deep-structure understanding to support sustainable behavioral change.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Disease (R01DK63523).

Appreciation is expressed to Hong Huynh for her graphic and technical assistance.

Contributor Information

Vicki Hines-Martin, Office of Community Engagement University of Louisville Associate Professor University of Louisville School of Nursing.

Barbara J. Speck, University of Louisville School of Nursing bjspec@gwise.louisville.edu.

Barbara Stetson, University of Louisville Department of Psychology and Brain Sciences bastet@gwise.louisville.edu.

Stephen W. Looney, Medical College of Georgia Departments of Biostatistics and Oral Diagnosis & Patient Services slooney@mcg.edu.

References

- Adams-Campbell LL, Ahaghotu C, Gaskins M, Dawkins F, Smoot, Polk O, et al. Enrollment of African Americans onto clinical treatment trials: Study design barriers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(4):730–734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright CL, Pruit L, Castro C, Gonzalez A, Woo S, King AC. Modifying physical activity in a multiethnic sample of low-income women: One year results from the IMPACT (Increasing Motivation for Physical ACTivity) project. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30(3):191–200. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann W. The problem of time in sociology: An overview of the literature on the state of theory and research on the “sociology of time”, 1900-82. Time Society. 1992;1(1):81–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. In: Vasta R, editor. Annals of child development. Vol. 6. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1989. pp. 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of cognitive development: Research models and fugitive findings. In: Wozniak RH, Fischer KW, editors. Development in context: Acting and thinking in specific environments. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1993. pp. 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd WM, Clayton LA. Race, medicine, and health care in the United States: A historical survey. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2001;93(3 Suppl.):11S–34S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchelli V, Pugeault-Cicchelli C, Merico M. Individual and social temporalities in American sociology (1940-2000) Time & Society. 2006;15(1):141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Coalition for the Homeless [Retrieved September 6, 2009];2008 homeless connect. 2009a from http://www.louhomeless.org/coal%20files/connect_08.pdf.

- Coalition for the Homeless . The homeless census and homeless point-in-time survey summary report. Metro Louisville Government; Louisville, KY: 2009b. [Google Scholar]

- Condon WS, Sander LW. Synchrony demonstrated between movements of the neonate and adult speech. Child Development. 1974;45(2):456–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LL, Broome ME, Cox RP. Maximizing retention in community-based clinical trials. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34(1):47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Jeffrey RW. Reducing barriers to participation in weight-loss programs in low-income women. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1998;98(2):198–200. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, Arean P. Recruitment and retention of Latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: Issues to face, lessons to learn. Gerontologist. 2003;43(1):45–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano AR, Mokuau N, Hughes C, Tortolero-Luna G, Risendal B, Ho RCS, et al. Participation of minorities in cancer research: The influence of structural, cultural, and linguistic factors. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10(8 Suppl.):S22–S34. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall ET. The dance of life: The other dimension of time. Anchor Press; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Harden JT, McFarland G. Avoiding gender and minority barriers to NIH funding. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2000;32(1):83–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiney SP, Adams SA, Cunningham JE, McKenzie W, Harmon B, Hebert JR, et al. Subject recruitment for cancer control studies in an adverse environment. Cancer Nursing. 2006;29(4):291–299. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200607000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson SL, Alioto ME, Boushey HA, for the Asthma Clinical Trials Network Attrition and retention of ethnically diverse subjects in a multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2001;22(Suppl. 6):S236–S234. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller CS, Gonzales A, Fleuriet KJ. Retention of minority participants in clinical research studies. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;27(3):292–306. doi: 10.1177/0193945904270301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger M, McFarland MR. Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, research and practice. 3rd ed McGraw-Hill Medical; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger M, McFarland MR. Culture care diversity and universality: A worldwide nursing theory. 2nd ed Jones and Bartlett; Boston: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lemon SC, Zapka JG, Estabrook B, Benjamin E. Challenges to research in urban community health centers. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(4):626–628. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkoff SE, Prohaska TR, Weitzman PF, Ory MG, editors. Recruitment and retention in minority populations. Springer; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Louisville Metro Public Health and Welfare . Health status assessment report. Louisville, KY: [retrieved April 22, 2009]. 2008. (2008) from http://www.louisvilleky.gov/NR/rdonlyres/24260BFF-D353-437C-9A82-3EB59FD37BC2/0/HSAR_2008withlinks.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- McCaskill-Stevens W, McKinney MM, Whitman CG, Minasian LM. Increasing minority participation in cancer clinical trials: The minority-based community clinical oncology program experience. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(22):5247–5254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.22.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JE, Kelly JR. Time and human interaction: Toward a social psychology of time. Guilford Press; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Cultural Competence [Retrieved July 9, 2009];Cultural competence: Definition and conceptual framework. 2009 from http://www11.georgetown.edu/research/gucchd/NCCC/foundations/frameworks.html.

- Pender NJ, Murdaugh C, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. 5th ed Prentice-Hall Health; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Qualls CD. Recruitment of African American adults as research participants for a language in aging study: Example of a principled, creative, and culture-based approach. Journal of Allied Health. 2002;31(4):241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia J, Braithwaite R. Cultural sensitivity in public health: Defined and demystified. Ethnicity and Disease. 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre AJ, Hylton JB, Johnson LM, Houston C, Witt M, Jacobson L, et al. Recruiting minority men who have sex with men for HIV research: Results from a 4-city campaign. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(6):1020–1027. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith A, Nelson A. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck BJ, Hines-Martin V, Stetson BA, Looney SW. An environmental intervention aimed at increasing physical activity levels in low-income women. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2007;22(4):263–271. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000278957.98124.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: Toward a participant-friendly system. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1995;87(23):1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Conference of Mayors . Hunger and homelessness survey: A status report on hunger and homelessness in America’s cities, a 25-city survey. Author; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy people 2010. Author; Washington, DC: 2000a. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services . Recruiting human subjects: Pressures in industry sponsored clinical research. Office of Inspector General; Washington DC: 2000b. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bertalanffy L. General system theory: Foundations, development, applications. Braziller; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Walker LO, Freeland-Graves JH, Milani T, George G, Hanss-Nuss H, Kim M, et al. Weight, behavioral and psychosocial factors among ethnically diverse, low-income women after childbirth: II. Trends and correlates. Women & Health. 2004;40(2):19–34. doi: 10.1300/J013v40n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]