Abstract

Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) is highly expressed in odontoblasts and osteoblasts/osteocytes and plays an essential role in tooth and bone mineralization and phosphate homeostasis. It is debatable whether DMP1, in addition to its function in the extracellular matrix, can enter the nucleus and function as a transcription factor. To better understand its function, we examined the nuclear localization of endogenous and exogenous DMP1 in C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal cells, MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells and 17IIA11 odontoblast-like cells. RT-PCR analyses showed the expression of endogenous Dmp1 in all three cell lines, while Western-blot analysis detected a major DMP1 protein band corresponding to the 57 kDa C-terminal fragment generated by proteolytic processing of the secreted full-length DMP1. Immunofluorescent staining demonstrated that non-synchronized cells presented two subpopulations with either nuclear or cytoplasmic localization of endogenous DMP1. In addition, cells transfected with a construct expressing HA-tagged full-length DMP1 also showed either nuclear or cytoplasmic localization of the exogenous DMP1 when examined with an antibody against the HA tag. Furthermore, nuclear DMP1 was restricted to the nucleoplasm but was absent in the nucleolus. In conclusion, these findings suggest that, apart from its role as a constituent of dentin and bone matrix, DMP1 might play a regulatory role in the nucleus.

Keywords: DMP1, nucleus, nucleolus, osteoblast, odontoblast, mesenchymal cell

1. Introduction

Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) was originally identified in teeth as an acidic extracellular matrix protein [1] and was later found highly expressed in odontoblasts of tooth and in osteoblasts/osteocytes of bone [2,3,4]. The loss of DMP1 function in humans and mice results in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia (ARHR), characterized by defects in odontoblast and osteoblast differentiation, matrix mineralization and hypophosphatemia resulting from elevated levels of circulating fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), a potent phosphaturic hormone [5,6]. Consistent with the pathogenic roles of hypophosphatemia induced by increased FGF23 levels, we reported that both a high-phosphate diet and the intraperitoneal injection of FGF23 neutralizing antibodies restored serum phosphorus levels to the normal range and significantly improved the skeletal abnormalities of Dmp1-null mice [5,7]. We also showed that the transgenic expression of either full-length DMP1 or a 57 kDa C-terminal fragment of DMP1 under the control of a 3.6 kb Col1a1 promoter fragment completely rescued the dental and skeletal defects of the Dmp1-null mice [8,9,10]. These findings suggest that DMP1 plays essential roles in regulating dental and skeletal development and phosphate homeostasis.

Previous studies have documented that DMP1 might regulate odontoblast and osteoblast differentiation as an extracellular integrin ligand or as a transcription factor. DMP1 contains a classical RGD motif, so it is generally accepted that the regulatory roles of DMP1 are initiated by the binding of DMP1 to the integrin receptors, followed by activation of the MAP kinase signaling pathway [11,12,13,14]. In addition, DMP1 has been shown to contain a nuclear localization signal (NLS), A472DSRKLIVDA481, in the C-terminal end of DMP1, and it may function as a transcription factor in the nucleus [15]. No DMP1 mRNA lacking the ER entry signal sequence has ever been found, it is suggested that extracellular non-phosphorylated full-length DMP1 may reenter the cell through its binding to the glucose-regulated protein GRP-78 receptor on the cell surface, followed by endocytosis and subsequent nuclear translocation [16]. We confirmed the nuclear localization of DMP1 in the nuclei of osteocytes in bone and in vitro cultured cells transfected with constructs expressing full-length DMP1 [17,18]. However, the nuclear localization of DMP1 has been challenged by another group [19].

The purpose of this study was to analyze the expression and subcellular localization of endogenous and exogenous DMP1 in C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal cells, MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells and 17IIA11 odontoblast-like cells by RT-PCR, Western-blot analysis and immunofluorescent staining. We found that the nuclear localization of DMP1 may be a tightly regulated event and that nuclear DMP1 was restricted to the nucleoplasm but was not present in the nucleolus. These findings provide novel insights into the way in which DMP1 may function in the nucleus.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Cells and Constructs

C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal cells, MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells and Cos-7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC); 17IIA11 odontoblast-like cells were derived from E18.5 mouse molar papilla [8]. C3H10T1/2 cells, 17IIA11 cells, and Cos-7 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The MC3T3-E1 cells were maintained in alpha-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS. All cells were grown in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at a temperature of 37° C. A construct expressing HA-tagged DMP1 (referred to as “DMP1-HA”) was generated by inserting the sequence, tacccctacgacgtgcccgactacgcc, encoding an HA tag and an HpaI recognition site (gttaac) between codon 259 and codon 260 of the mouse DMP1 cDNA sequence in a pCDNA3 vector [20] using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies).

2.2. RT-PCR Analysis

To determine the expression of the endogenous Dmp1, total RNA was isolated from subconfluent C3H10T1/2 cells, MC3T3-E1 cells and 17IIA11 cells with Trizol® reagent (Invitrogen Corporation) and then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). PCR was carried out with the GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Life Technologies Corporation) using AmpliTaq® DNA Polymerase (Life Technologies Corporation). Initial denaturation was 94° C for 1 minute followed by 35 cycles of 94° C for 30 seconds, 55° C for 30 seconds and 72° C for 1 minute. The primer sequences for the Dmp1 gene were forward primer 5′-cgagtctcaggaggaca -3′ and reverse primer 5′-ctgtcctcctcactgga -3′. The primer sequences for Gapdh gene were forward primer 5′-tggagccaaaagggtca -3′ and reverse primer 5′-cttctgggtggcagtga -3′.

2.3. Transient Transfection

All transient transfection experiments were performed with Fugene HD transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Applied Science). For Western-blot analysis, the Cos-7 cells in a 6-well plate were transiently transfected with a total of 2 μg of either an empty vector or a construct expressing DMP1-HA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM, and the transfected cells were further cultured for 48 hours. The conditioned medium was then collected and analyzed by Western-blot analyses. For immunofluorescent staining, C3H10T1/2 cells were transiently transfected with 0.6 μg of the DMP1-HA construct in a 24-well plate; the next day, the transfected cells were replated into 8-well chamber slides. Twenty-four hours after replating, the transfected cells were processed for immunofluorescent staining.

2.4. SDS-PAGE and Western-blot Analysis

The total cell lysates extracted from the C3H10T1/2, MC3T3-E1 and 17IIA11 cells or the conditioned medium collected from Cos-7 cells transfected with either an empty vector or a DMP1-HA construct were electrophoresed using a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and the separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were then immunoblotted with rabbit anti-DMP1 polyclonal antibody (857-3; 1:2000), which recognizes the C-terminal region of DMP1 [21], or mouse anti-HA monoclonal antibody (Covance; 1:2000) followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1000) or HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1000). β-actin was immunoblotted with mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin-peroxidase antibody (Sigma; 1:20,000). The immunostained protein bands were detected with ECL™ Chemiluminescent Detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences) and imaged using a CL-XPosure film (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.)

2.5. Immunofluorescent Staining

The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 5 minutes and blocked overnight with 1% goat serum and 0.05% NaN3 in PBS. To detect endogenous DMP1, the cells were incubated with mouse anti-DMP1 monoclonal antibody (8G10.3; 1:800) or rabbit anti-DMP1 polyclonal antibody (857-3; 1:250), which recognizes the C-terminal region of DMP1 [21,22]. The specificity of the polyclonal antibody was confirmed by preincubating it overnight at 4° C with or without 4 μg/ml of the synthetic peptide used to generate the antibody. The preabsorbed primary antibody was then used for immunofluorescent staining. To detect exogenous DMP1, the transfected cells were incubated with mouse anti-HA monoclonal antibody (Covance; 1:2000) or together with rabbit anti-WDR46 polyclonal antibody (Proteintech group; 1:1000) for 2 hours, followed by incubation with Alexa 555-conjugated goat anti-mouse or Alexa 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG(H+L) (Invitrogen Corporation; 1:1000) for 1 hour. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI solution. Normal mouse or rabbit IgG was used as a negative control. The fluorescent-stained cells were imaged under a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U fluorescence microscope.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of the Dmp1 gene in various cell lines

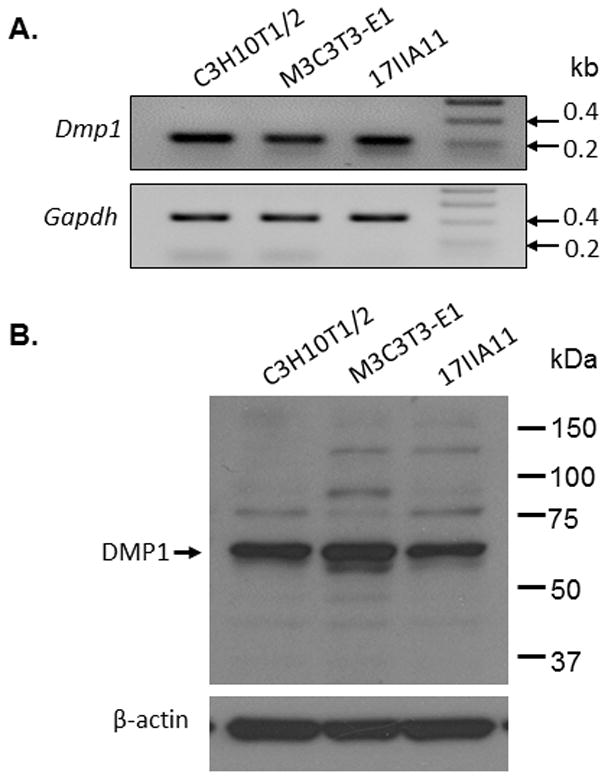

In addition to the ER-entry signal peptide, DMP1 also contains a functional NLS and may enter the nucleus and function as a transcription factor [15,16]. However, such a nuclear function has been controversial [19]. To better understand the range of DMP1 activities, we first analyzed the expression of endogenous Dmp1 in C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal cells, MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells and 17IIA11 odontoblast-like cells. We identified DMP1 transcripts in all three cell lines by RT-PCR analyses (Fig. 1A) and also revealed DMP1 proteins in the total cell lysates of these three cell lines by Western-blot analyses using polyclonal antibodies against the C-terminal part of DMP1 (Fig. 1B). It is intriguing that the size of the major DMP1 protein band is around 57 kDa, which corresponds to the size of the C-terminal fragment of DMP1 generated by the proteolytic processing of the secreted full-length DMP1 [10].

Fig 1. Expression of Dmp1 gene in various cell lines.

A. RT-PCR analyses showing that Dmp1 transcripts were detected in C3H10T1/2 cells, MC3T3-E1 cells and 17IIA11 cells (B). Western-blot analyses with antibodies against the C-terminal part of DMP1 revealed a major protein band of about 57 kDa in the total cell lysates of all three cell lines.

3.2. Nuclear localization of endogenous DMP1 in various cell lines

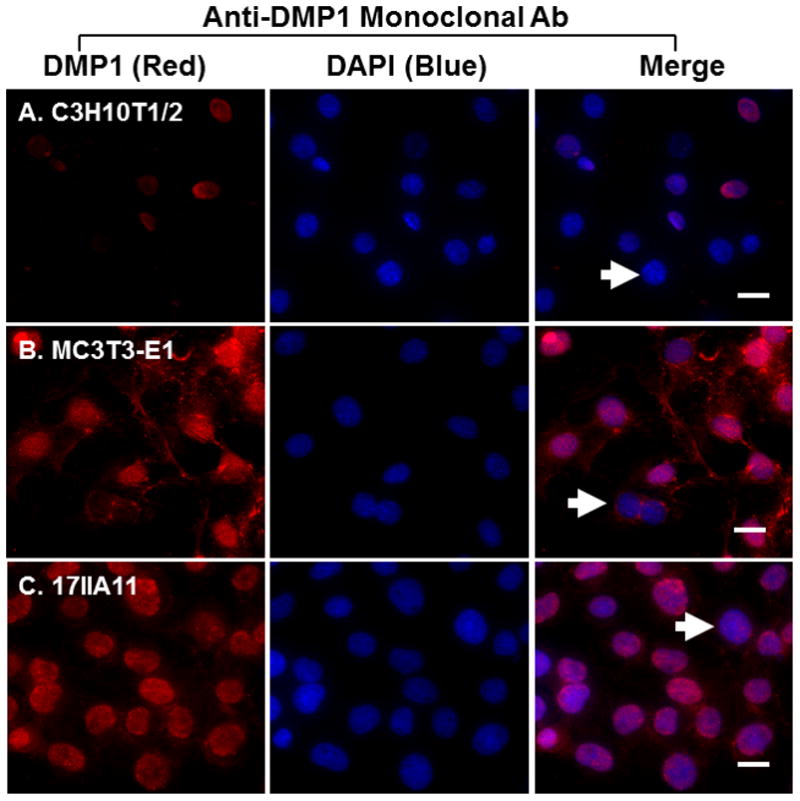

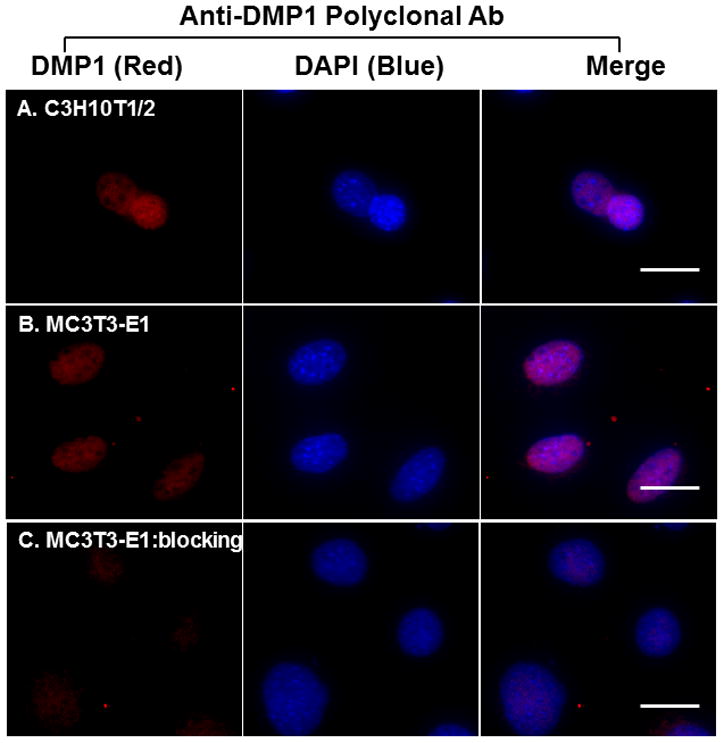

Next, we performed immunofluorescent staining to determine whether endogenous DMP1 was able to enter the nucleus. We observed the nuclear localization of endogenous DMP1 in all three cell lines by immunofluorescent staining with a monoclonal anti-DMP1 antibody against the C-terminal part of DMP1 (Fig. 2A–C). However, we found that the non-synchronized cells consisted of two subpopulations of cells, one with and the other without nuclear DMP1 staining (Table 1). Nuclear DMP1 was also observed in the C3H10T1/2 cells (Fig. 3A) and MC3T3-E1 cells (Fig. 3B) when a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the C-terminal part of DMP1 was used; the staining was inhibited after the antibody was preincubated with the synthetic peptide used to generate the antibody (Fig. 3C), confirming the specificity of the antibody. Collectively, these findings suggest that endogenous DMP1 can enter the nuclei in all the cell lines examined.

Fig 2. Nuclear localization of endogenous DMP1 proteins.

Immunofluorescent staining with anti-DMP1 monoclonal antibody showed the nuclear localization of DMP1 proteins in subpopulations of C3H10T1/2 cells (panel A), MC3T3-E1 cells (panel B) and 17II11 cells (panel C). DMP1 signal is in red. IgG controls show no staining signal (not shown). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Arrows indicate cells that lack nuclear DMP1 signal. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Table 1.

Nuclear localization of endogenous DMP1 in various cell lines

| Cell type | Cells with nuclear localization | Total cells counted | % cells with nuclear localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| C3H10T1/2 | 124 | 174 | 71.3 |

| MC3T3-E1 | 202 | 249 | 81.1 |

| 17IIA11 | 92 | 139 | 66.28 |

Fig 3. Detection of nuclear DMP1 proteins by a polyclonal antibody.

Immunofluorescent staining with anti-DMP1 polyclonal antibodies confirmed the nuclear localization of DMP1 proteins in C3H10T1/2 (panel A) and MC3T3-E1 (panel B). The staining signal was inhibited when the polyclonal antibodies were preincubated with the peptides used to generate the antibodies (panel C). DMP1 signal is in red. IgG controls show no staining signal (not shown). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm.

3.3. Nuclear localization of exogenous DMP1

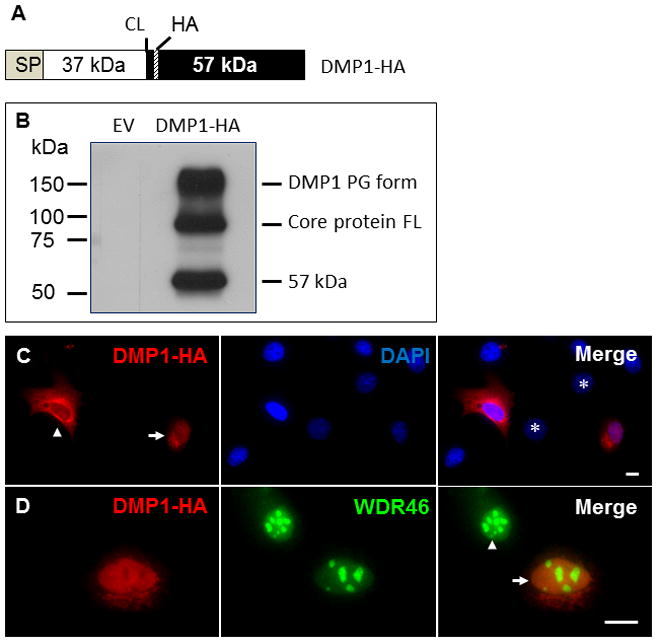

To determine whether exogenous DMP1 was transported into the nucleus, a DMP1 expression construct was generated that would express a DMP1 protein with a hemagglutinin (HA) tag inserted after the proteolytic cleavage sites (designated as “DMP1-HA”), so that the HA-tag would label either the full-length DMP1 (before cleavage) or the 57 kDa C-terminal fragment (after cleavage) (Fig. 4A). We transfected this DMP1-HA construct into easily transfectable Cos-7 cells and analyzed the conditioned medium by Western-blot analysis with polyclonal antibodies against the C-terminal part of DMP1. We found that the HA-tag did not affect the secretion, processing or posttranslational modifications of the tagged DMP1 since full-length, glycosylated and proteolytically processed DMP1 could be detected in the conditioned medium (Fig. 4B). The DMP1-HA construct was then transfected into C3H10T1/2 cells, and immunofluorescent staining showed that the transfected cells presented HA staining signals in either the nuclei or cytoplasm when detected with an antibody against the HA tag (Fig. 4C). These data provided strong evidence that DMP1 enters the nucleus.

Fig. 4. Nuclear localization of exogenous DMP1 proteins in C3H10T1/2 cells.

A. Schematic representation of the DMP1-HA construct showing the ER entry signal peptide (SP), 37 kDa N-terminal fragment (37 kDa), key cleavage site (CL), 57 kDa C-terminal fragment (57 kDa) and the location of the hemagglutinin tag (HA). B. Western-blot analysis of DMP1-HA proteins. Cos-7 cells were transiently transfected with DMP1-HA expression constructs. The conditioned medium was analyzed by Western blotting using the anti-DMP1 C-terminal polyclonal antibody, showing the processed 57 kDa C-terminal fragment, the full-length (FL) core protein and the proteoglycan (PG) form. EV, empty expression vector. Panel C. DMP1-HA expression constructs were transiently transfected into C3H10T1/2 cells, which were then immunofluorescently stained with antibodies against the HA tag (red). The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The arrow indicates a cell with nuclear HA signal; the arrowhead points to a cell without nuclear HA signal. The asterisks indicate nontransfected cells (without the constructs). Scale bar = 10 μm. Panel D. C3H10T1/2 cells transfected with DMP1-HA expression constructs were immunofluorescently stained with antibodies against the HA tag (red) and WDR46 (green). The arrow indicates a transfected cell, whereas the arrowhead points to a nontransfected cell. Scale bar = 10 μm

3.4. Lack of DMP1 in the nucleolus

Although DMP1 proteins were localized in the nuclei of many cells, they appeared to be unevenly distributed throughout the nucleus (Fig. 3 and 4C). Their distribution pattern resembled a negative image of the nucleolus distribution pattern [23]; the nucleolus is the center for rRNA processing and ribosomal assembly. WDR46 is enriched in the nucleoli and is a good maker for nucleoli [24]. Therefore, we performed co-immunofluorescent staining on cells transfected with a construct expressing HA-tagged full-length DMP1 with an antibody against the HA tag and an antibody against WDR46. The staining showed that, although weak WDR46 staining was observed throughout the nucleoplasm, intense signals were localized in the nucleoli; the merged image confirmed that nuclear DMP1 was absent in the WDR46-enriched region (Fig. 4D). These observations suggest that nuclear DMP1 may not be involved in rRNA processing or ribosomal assembly.

4. Discussion

Whether or not DMP1 can enter the nucleus and function as a transcription factor is controversial [15,16,17,18,19]. In this study, we found that, in addition to MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells and 17IIA11 odontoblast-like cells, DMP1 was also expressed in C3H10T1/2 cells, which are pluripotent stem cells that are able to differentiate into multiple lineages of cells, including osteoblast, chondrocyte and adipocyte [25,26,27,28]. Interestingly, they can also differentiate into odontoblast-like cells if excessive DMP1 is produced [29]. The expression of endogenous DMP1 in the C3H10T1/2 cells suggests that DMP1 may not necessary mark the differentiation of a cell toward the odontoblast or osteoblast lineage. Similarly, DMP1 is widely expressed in non-mineralized tissues, including brain, salivary gland, pancreas and kidney [30,31,32]. These observations suggest that DMP1 might have a function that is not unique to odontoblast/osteoblast, or have different functions in different cells/tissues.

In addition, we showed that nonsynchronized cells consisted of two subpopulations with either nuclear or cytoplasmic localization of endogenous as well as exogenous DMP1 in the cells, consistent with the presence of a typical ER-entry signal peptide sequence at its N-terminus and a functional NLS sequence in the carboxyl-terminal end of the DMP1 [15]. We further showed that nuclear DMP1 was restricted to the nucleoplasm and was absent in the nucleolus. This subnuclear localization is consistent with its function as a transcription factor in the nucleus, regulating odontoblast differentiation [15]. In addition, our findings also suggest that the nuclear localization of DMP1 may be highly regulated because only a proportion of cells showed the nuclear localization of DMP1. Since the cells in each cell line are genetically identical, the nuclear translocation of DMP1 may be associated with the progression of the cell cycle.

Although we have shown that both endogenous and exogenous DMP1 was able to accumulate in the nuclei, the identity of the nuclear DMP1 is not yet clear. First, previous studies have indicated that nuclear DMP1 is most likely the full-length DMP1 [16], although our Western-blot analysis detected a major DMP1 protein band of about 57 kDa in the total cell lysates corresponding to the 57 kDa C-terminal fragment of DMP1 [10]. Second, we previously showed that only the C-terminal fragment is detected in the nuclei of osteocytes in bone and in vitro cultured cells transfected with constructs expressing full-length DMP1 when using various antibodies against either the N-terminal or C-terminal fragment of DMP1 [17,18]. Third, we previously reported that the 57 kDa C-terminal fragment of DMP1 is sufficient to completely rescue the Dmp1-null mouse skeletal and phosphate abnormalities [9]. These findings suggest that the nature of the nuclear form of DMP1, i.e., full-length DMP1 or a 57 kDa C-terminal fragment, remains to be further investigated.

In summary, our studies suggest that the nuclear localization of DMP1 is a common and highly regulated process. We are currently exploring whether the nuclear localization is related to the progression of the cell cycle. In addition, we are investigating the identity of nucleus-localized DMP1 to determine whether it is full-length DMP1 or only the 57 kDa C-terminal fragment. This information will not only help elucidate the molecular mechanisms through which DMP1 regulates the formation of tooth and bone but will also help unravel the pathogenic mechanisms of ARHR caused by the loss of DMP1 function.

Highlights.

Nuclear localization of DMP1 in various cell lines

Non-synchronized cells show either nuclear or cytoplasmic localization of DMP1

Nuclear DMP1 is restricted to the nucleoplasm but absent in the nucleolus

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jeanne Santa Cruz for her assistance with the editing of this article. This research was supported by NIDCR/NIH Grants: R03 DE021773 to YL; R01 DE019471 and R01 DE013368 to RD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.George A, Sabsay B, Simonian PA, Veis A. Characterization of a novel dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein. Implications for induction of biomineralization. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12624–12630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng JQ, Huang H, Lu Y, Ye L, Xie Y, Tsutsui TW, Kunieda T, Castranio T, Scott G, Bonewald LB, Mishina Y. The Dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1) is specifically expressed in mineralized, but not soft, tissues during development. J Dent Res. 2003;82:776–780. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Souza RN, Cavender A, Sunavala G, Alvarez J, Ohshima T, Kulkarni AB, MacDougall M. Gene expression patterns of murine dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1) and dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP) suggest distinct developmental functions in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:2040–2049. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.12.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George A, Gui J, Jenkins NA, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Veis A. In situ localization and chromosomal mapping of the AG1 (Dmp1) gene. J Histochem Cytochem. 1994;42:1527–1531. doi: 10.1177/42.12.7983353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng JQ, Ward LM, Liu S, Lu Y, Xie Y, Yuan B, Yu X, Rauch F, Davis SI, Zhang S, Rios H, Drezner MK, Quarles LD, Bonewald LF, White KE. Loss of DMP1 causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1310–1315. doi: 10.1038/ng1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorenz-Depiereux B, Bastepe M, Benet-Pages A, Amyere M, Wagenstaller J, Muller-Barth U, Badenhoop K, Kaiser SM, Rittmaster RS, Shlossberg AH, Olivares JL, Loris C, Ramos FJ, Glorieux F, Vikkula M, Juppner H, Strom TM. DMP1 mutations in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia implicate a bone matrix protein in the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1248–1250. doi: 10.1038/ng1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang R, Lu Y, Ye L, Yuan B, Yu S, Qin C, Xie Y, Gao T, Drezner MK, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ. Unique roles of phosphorus in endochondral bone formation and osteocyte maturation. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1047–1056. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Y, Ye L, Yu S, Zhang S, Xie Y, McKee MD, Li YC, Kong J, Eick JD, Dallas SL, Feng JQ. Rescue of odontogenesis in Dmp1-deficient mice by targeted re-expression of DMP1 reveals roles for DMP1 in early odontogenesis and dentin apposition in vivo. Dev Biol. 2007;303:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu Y, Yuan B, Qin C, Cao Z, Xie Y, Dallas SL, McKee MD, Drezner MK, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ. The biological function of DMP-1 in osteocyte maturation is mediated by its 57-kDa C-terminal fragment. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:331–340. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin C, Brunn JC, Cook RG, Orkiszewski RS, Malone JP, Veis A, Butler WT. Evidence for the proteolytic processing of dentin matrix protein 1. Identification and characterization of processed fragments and cleavage sites. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34700–34708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305315200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kulkarni GV, Chen B, Malone JP, Narayanan AS, George A. Promotion of selective cell attachment by the RGD sequence in dentine matrix protein 1. Arch Oral Biol. 2000;45:475–484. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(00)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Marschall Z, Fisher LW. Dentin matrix protein-1 isoforms promote differential cell attachment and migration. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32730–32740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804283200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang B, Cao Z, Lu Y, Janik C, Lauziere S, Xie Y, Poliard A, Qin C, Ward LM, Feng JQ. DMP1 C-terminal mutant mice recapture the human ARHR tooth phenotype. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2155–2164. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu H, Teng PN, Jayaraman T, Onishi S, Li J, Bannon L, Huang H, Close J, Sfeir C. Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) signals via cell surface integrin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29462–29469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.194746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narayanan K, Ramachandran A, Hao J, He G, Park KW, Cho M, George A. Dual functional roles of dentin matrix protein 1. Implications in biomineralization and gene transcription by activation of intracellular Ca2+ store. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17500–17508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212700200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravindran S, Narayanan K, Eapen AS, Hao J, Ramachandran A, Blond S, George A. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein GRP-78 mediates endocytosis of dentin matrix protein 1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29658–29670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800786200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maciejewska I, Qin D, Huang B, Sun Y, Mues G, Svoboda K, Bonewald L, Butler WT, Feng JQ, Qin C. Distinct compartmentalization of dentin matrix protein 1 fragments in mineralized tissues and cells. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;189:186–191. doi: 10.1159/000151372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang B, Maciejewska I, Sun Y, Peng T, Qin D, Lu Y, Bonewald L, Butler WT, Feng J, Qin C. Identification of full-length dentin matrix protein 1 in dentin and bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;82:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9140-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrow EG, Davis SI, Ward LM, Summers LJ, Bubbear JS, Keen R, Stamp TC, Baker LR, Bonewald LF, White KE. Molecular analysis of DMP1 mutants causing autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets. Bone. 2009;44:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu Y, Qin C, Xie Y, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ. Studies of the DMP1 57-kDa functional domain both in vivo and in vitro. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;189:175–185. doi: 10.1159/000151727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang B, Sun Y, Chen L, Guan C, Guo L, Qin C. Expression and distribution of SIBLING proteins in the predentin/dentin and mandible of hyp mice. Oral Dis. 2010;16:453–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Y, Gandhi V, Prasad M, Yu W, Wang X, Zhu Q, Feng JQ, Hinton RJ, Qin C. Distribution of small integrin-binding ligand, N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLING) in the condylar cartilage of rat mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morimoto H, Okamura H, Haneji T. Interaction of protein phosphatase 1 delta with nucleolin in human osteoblastic cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:1187–1193. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leung CK, Empinado H, Choe KP. Depletion of a nucleolar protein activates xenobiotic detoxification genes in Caenorhabditis elegans via Nrf /SKN-1 and p53/CEP-1. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:937–950. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Date T, Doiguchi Y, Nobuta M, Shindo H. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 induces differentiation of multipotent C3H10T1/2 cells into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes in vivo and in vitro. J Orthop Sci. 2004;9:503–508. doi: 10.1007/s00776-004-0815-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujita T, Azuma Y, Fukuyama R, Hattori Y, Yoshida C, Koida M, Ogita K, Komori T. Runx2 induces osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation and enhances their migration by coupling with PI3K-Akt signaling. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:85–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang H, Song TJ, Li X, Hu L, He Q, Liu M, Lane MD, Tang QQ. BMP signaling pathway is required for commitment of C3H10T1/2 pluripotent stem cells to the adipocyte lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12670–12675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906266106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang QQ, Otto TC, Lane MD. Commitment of C3H10T1/2 pluripotent stem cells to the adipocyte lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9607–9611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403100101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narayanan K, Srinivas R, Ramachandran A, Hao J, Quinn B, George A. Differentiation of embryonic mesenchymal cells to odontoblast-like cells by overexpression of dentin matrix protein 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4516–4521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081075198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terasawa M, Shimokawa R, Terashima T, Ohya K, Takagi Y, Shimokawa H. Expression of dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) in nonmineralized tissues. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22:430–438. doi: 10.1007/s00774-004-0504-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW. Renal expression of SIBLING proteins and their partner matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) Kidney Int. 2005;68:155–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW. Expression of SIBLINGs and their partner MMPs in salivary glands. J Dent Res. 2004;83:664–670. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]