Abstract

A timely review series on small heat shock proteins has to appropriately examine their fundamental properties and implications in the cardiovascular system since several members of this chaperone family exhibit robust expression in the myocardium and blood vessels. Due to energetic and metabolic demands, the cardiovascular system maintains a high mitochondrial activity but irreversible oxidative damage might ensue from increased production of reactive oxygen species. How equilibrium between their production and scavenging is achieved becomes paramount for physiological maintenance. For example, heat shock protein B1 (HSPB1) is implicated in maintaining this equilibrium or redox homeostasis by upholding the level of glutathione, a major redox mediator. Studies of gain or loss of function achieved by genetic manipulations have been highly informative for understanding the roles of those proteins. For example, genetic deficiency of several small heat shock proteins such as HSPB5 and HSPB2 is well-tolerated in heart cells whereas a single missense mutation causes human pathology. Such evidence highlights both the profound genetic redundancy observed among the multigene family of small heat shock proteins while underscoring the role proteotoxicity plays in driving disease pathogenesis. We will discuss the available data on small heat shock proteins in the cardiovascular system, redox metabolism and human diseases. From the medical perspective, we envision that such emerging knowledge of the multiple roles small heat shock proteins exert in the cardiovascular system will undoubtedly open new avenues for their identification and possible therapeutic targeting in humans.

Keywords: homeostasis, cardiomyocyte, heat shock factor, transgenic, knockout

INTRODUCTION

Historically, heat shock proteins (HSPs) are defined by properties of stress inducible expression in response to diverse (patho) physiological stimuli. Inducible Hsp genes share common DNA motifs (termed heat shock element-HSE), which correspond to DNA binding sites for heat shock factors (HSF) (see the review by V Mezger and collaborators in this series). Nevertheless, several members belonging to this family do not exhibit stress inducible/HSF-dependent expression. Small heat shock proteins are characterized by their smaller molecular weight (around 20–30kDa), and a conserved protein domain named the α-crystallin domain, which is important for their chaperone activity (Kampinga et al., 2009, Taylor & Benjamin, 2005). In Table 1, we outline the molecular features for specific cardiac members of sHSPs (HSPB1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8), which are the main focus of this review.

Table 1.

Chromosomal location and molecular characteristics of cardiac sHsps

| Small Hsps genes | Additional names | Human chromosomal locationa | Heat inducibility | IPR003090b: Alpha crystallin, N-term |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hspb1 | Hsp27 | chr 7, 7q11.23 | yes | no |

| Hspb2 | Mkbp | chr 11, 11q22-q23 | no | yes |

| Hspb3 | HSPL27 | chr 5, 5q11.2 | no | no |

| Hspb5 | CryAB | chr 11, 11q22.3-q23-1 | yes | yes |

| Hspb6 | Hsp20 | chr 19, 19q13.12 | yesa | yes |

| Hspb7 | cvHsp | chr 1, 1p36.23-p34.3 | no | no |

| Hspb8 | Hsp22, H11kinase | chr 7, 12q24.23 | no | no |

O’Connor and Rembold (2002) describe a moderate heat inducible HspB6 expression.

This domain appears to be required for the formation of higher order aggregates.

Cardiovascular diseases affecting the heart and major blood vessels include various pathologies such as hypertension, myocardial infarction due to coronary vessel occlusion, cardiac arrhythmia, genetic cardiomyopathy and, importantly, atherosclerosis. A major cause of mortality, atherosclerosis is a pathological process of lipid and extracellular matrix accumulation in the intima of blood vessels, which can ultimately become occluded causing cardiac ischemia and infarction. In this context, the main sHSP, HSPB1, has been extensively studied and recently reviewed (Ghayour-Morbahan et al., 2012) while much less is known about the other sHSPs (e.g. HspB6, Lepedda et al., 2009). Three sHSPs are known to be highly expressed in the smooth muscle cells and are likely involved in vascular tone: HSPB1, 5 and 6 (Dreiza et al., 2010; McLemore et al., 2005; Salinthone et al., 2008). Vascular tone refers to the balance between vasodilatory and vasoconstrictor influences and, in response to extrinsic and intrinsic factors, regulates the systemic vascular resistance and local blood flow in the organ, respectively. The main conclusion from those studies is that phosphorylation of HSPB6 contributes to vasorelaxation whereas phosphorylated HSPB1 antagonizes such effects, leading to more vasoconstriction (McLemore et al., 2005; Salinthone et al., 2008).

Vessels are the primary conduits for the blood supply that supports organ survival and cardiac cell function. Conversely, the cardiomyocyte is the principal cell type engaged in generating the necessary contractile force from to sustain the cardiac output to the entire organism circulation. Cardiac muscle cells are the main contributors to heart volume (~55%) while the remaining tissue comprises fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and nerves. Importantly, mitochondria contribute to 35% of the cardiac cell volume (Banerjee et al., 2007; Nag, 1980; Vliegen et al., 1991; Zak, 1974). This large mitochondrial compartment in the heart corresponds to the high energetic demand of permanently beating cells. As mitochondria are also the main source of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the maintenance of redox metabolism is a constant challenge in normal hearts but even more in pathological hearts. Thus sHSPs in particular, play a protective role against deleterious effects of redox imbalance observed when ROS production exceeds scavenging mechanisms. We have recently discussed the links existing between redox and protein homeostasis in heart (Christians and Benjamin, 2011), which relies on several protective mechanisms and requires the chaperone function of HSPs. Because of their abundance in cardiomyocytes (HSPB5: from 0.1 % up to 2 % soluble protein content) (Golenhofen et al., 1998; Kato et al., 1991; Ray et al., 2001), sHSP chaperones are ideally suited for surveillance roles and specifically serve to maintain cardiac cells in “perfect working order.” This is well-illustrated by the deleterious effects of the R120G mutation in HspB5/CryAB, which causes multisystem disease including cardiomyopathy (see 4.4.).

Although the pioneering studies on sHSP expression in heart were published more than 20 years ago (Bhat and Nagineni, 1989; Kato et al., 1991), we have still a lot to learn about those chaperones. Several reviews have covered the multifaceted roles of sHSPs, in part or exclusively dedicated to the cardiovascular system (sHSPs: Mymrikov et al., 2011; HSPB1: Ghayour-Mobarhan et al., 2012; HSPB1&5: Arrigo et al., 2007; HSPB6: Fan and Kranias, 2011; Edwards et al., 2011; HSPB8: Danan et al., 2007)). This review will discuss the present knowledge about sHSPs in the heart during development, aging and diseases, including the experimental models exploited to gather this information with an emphasis on their contributions to the redox metabolism and homeostasis.

2. SMALL HSP EXPRESSION IN THE NORMAL CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM: FROM EMBRYONIC DEVELOPMENT TO AGING

Small HSP expression and biological roles during embryonic development are being covered elsewhere in this review series (Morrow and Tanguay, 2012). Nevertheless, we wish to emphasize the major characteristics of sHSPs during development and aging of the cardiovascular system.

Several reviews have listed the members of the sHSP family (Taylor and Benjamin, 2005; Kampinga et al., 2009; Mymrikov et al., 2011). HSPB1 and HSPB5 are the first small Hsps expressed in heart (Bhat and Nagineni, 1989; Iwaki et al., 1989; Gernold et al., 1993). While this was not so surprising for the ubiquitously expressed HSPB1, this was unexpected for HSPB5/CryAB first identified in the lens. This is an appealing example of “gene recycling/sharing” during evolution where genes can evolve various roles without duplication (Caspers et al., 1995; Sun and MacRae, 2005; Taylor and Benjamin, 2005).

As an overview, embryonic development starts with the fertilization of the oocyte by sperm leading to the formation of a single cell embryo, the zygote. Through cleavage, the zygote evolves in a multicellular embryo, the blastocyst, which implants into the uterus in mammals for further development. Formation of the cardiovascular system becomes essential as soon as the embryo reaches the size and number of cells requiring an adequate nutrient and waste “disposal.” Figure 1 illustrates the pronounced expression of specific sHSPs during embryonic development of the cardiovascular system in mammals.

Figure 1.

Small Hsp expression in the developing heart in mammals. (A) LacZ knock-in shows the expression of HspB1 in heart and in head vasculature (arrow) (Huang et al., 2007). (B) Immunohistochemistry reveals the high level of HSPB1 expression in mouse heart (13.5 dpc) (Xiao et al., 1999). (C) In situ hybridization was employed to show the strong expression of Hspb5 in mouse heart (12.5 dpc) (Benjamin et al., 1997). (D) In situ hybridization illustrates the strong and highly specific expression of Hspb7 in developing mouse hearts (14.5 dpc) Diez-Roux et al., 2011). h, heart; m, skeletal muscle; l, liver; v, ventricle. (E) The graph schematically presents the profile of sHSP expression from the fetal period to aging based on relative value calculated as a ratio to the level measured at 1 month. Available data was obtained for published reports of Hspb1 and Hspb2 (Shama et al., 1999), Hspb5 (Oertel et al, 2000), Hspb8 (Depre et al., 2002).

Within the context of evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo), an interesting question is whether the pattern of expression of the sHSPs would change with the increasing complexity and organization of the heart through evolution. It would be conceivable that an increased metabolic demand of the organism dictates a more complex contractile organ and that this would be associated to profound qualitative/quantitative requirements for the chaperone properties of sHSPs to prevent protein misfolding and related proteotoxicity. As gene expression data accumulate in various animal models used in evo-devo studies, this question will soon find amore complete answer. Meanwhile, existing information provides some interesting insights in sHSPs and developing hearts, indicating that this hypothetical correlation is likely to be more complex than suggested. Flies have received recent attention as a model for cardiovascular diseases (D melanogaster: Wolf et al., 2011 Nishimura et al., 2011) in which the embryonic heart is formed by 104 cardiac cells organized in a contractile tube delimited by one layer of cells. Although the fly genome contains an extended sHSP family (7 genes), only two sHSPs, Hsp22 and Hsp26, are reported to exhibit a moderate expression in this organ (please see database: http://flybase.org/).

In the sea squirt (C intestinalis), considered part of an outgroup of vertebrates, the beating organ is still made of a simple tube but this one includes putative sub-territories as an evolving preliminary plan for a multichambered heart. The sea squirt genome contains two members close to mammalian cardiac sHSPs (Hsp27/HspB1 like and HspB8 like) and the EST (Expressed Sequence Tag) profile shows that the homolog of HspB1 is highly expressed in the tadpole heart (Cin.20758) (Franck et al., 2004). In fish (D rerio), where the heart is organized withone ventricle and atrium, and in which the regenerative capability is maintained in adults, there is a robust expression of HSPB1 whose sequence is close to mammalian orthologs (Tucker and Shelden, 2009). Based on ESTs, several sHSPs are predominantly expressed in the fish heart (HspB2, HspB6, HspB8, and HspB11), the latter being the most abundant and not found in mammals (Elicker and Hutson, 2007). Unlike in mammals, fish genome contains two genes (HspB5a and HspB5b) encoding the CryAB homolog whose protein expression remains lens-specific and is not found in the heart (Tucker and Shelden, 2009). Similarly in birds, which are warm-blooded vertebrates with a four-chambered heart, there are no detectable ESTs corresponding to HspB5 in the heart (UniGene Gga.1999). Altogether, these data reveal a more complex pattern of sHSPs expression than expected might exist along the evolutionary tree with the prominent expression of cardiac HSPB5, for example, reflecting possible mammalian innovation.

The next consideration is whether during embryonic development, the complexity of the organ, the energetic demand in the cardiac cells coupled with the production of ROS and possible risk of oxidative stress correlate with either a qualitative and/or quantitative pattern of sHSP expression. At least in mammals, the hypothesis of sHSPs expression seems to be supported by the corresponding developmental rise of oxidative stress. The profile of expression of HSPB2 and also HSPB1 (in contrast, for example, with members of HSP70 family) exhibits a sharp peak in the postnatal heart when cardiac function and metabolic demands are dramatically increasing in comparison with fetal development (Shama et al., 1999). Because a high level of cardiac activity is linked to a demand in mitochondrial energy, the organ becomes at risk for ROS-induced oxidative damage of the proteome, requiring a higher level of sHSPs to mitigate and maintain proteostasis (see also 3.1).

Along ontogeny, organisms face increased susceptibility to a variety of age-related illnesses and diseases. Aging is characterized universally by a reduced ability to induce the “classical” heat shock response, which corresponds to a rapid induction of HSP expression (Christians and Benjamin, 2012). This has been considered a sign of the lower capability of aging organisms to cope with stressful demands and to protect against proteotoxic stress. Nevertheless, sHSPs are expressed constitutively at basal level under normal conditions and it is interesting to note that the level of expression of HSPB1, a major member of sHSPs family, increases in heart as animals age from 3 to 6 months (Rajasekaran et al., 2007). This trend was also observed in two other age-related studies. Grant and collaborators identified similar upregulation for HSPB1 (26mo/4mo ratio: 1.13) and for HSPB5 (ratio: 1.31) in the rat left ventricle (Grant et al., 2009). Of interest, PIT1-deficient (dw/dw) mice (MGI: 1856025), which are known to live 30% longer than wild type control mice, also display significantly higher levels of HSPB1 and HSPB5 in hearts, suggesting such chaperone recruitment might potentially extend proper function of this organ (Swindell et al., 2009). So despite the diminished rapid-acute stress response, aging might trigger a chronic induction of some small HSPs. Taking into account the data from the long lived mice (Pit(dw/dw)), this seems to correlate with a longer lifespan and/or reduced deleterious effects of aging. Small HSPs function and aging is more extensively reviewed in another article of this series (Morrow and Tanguay, 2012).

3. REDOX METABOLISM AND SMALL HSPS

3.1. FOUNDATIONS FOR SMALL HSP ROLES IN REDOX METABOLISM

Redox metabolism could be defined as the biochemical reactions involved 1) in the production of ROS whose overabundance leads to oxidative stress and 2) in the scavenging of those species, which, in case of excessive activity, can provoke reductive stress. Thus redox metabolism is constantly regulated to maintain redox homeostasis and prevent deleterious effects associated in particular to oxidative stress and oxidation of cellular compounds. Redox metabolism has received increasing attention in the cardiovascular field and several recent reviews have discussed the definition of redox state/metabolism and how this impacts cardiac function (Christians and Benjamin, 2011; Santos et al., 2011; Sumandea et al., 2011). We have already pointed out the high-energy demand existing in beating cardiomyocytes and the potential risk for oxidative damage from excessive production of ROS in particular, at the level of the mitochondria, the primary energy factories of the cells. If not buffered through complementary redox couples (NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+, GSH/GSSG), ROS can alter myofibrillar proteins and other important proteins in cardiac cells leading to cardiac dysfunction. As a second line of defense, chaperones are known to be protective against the proteotoxic effect of oxidative stress.

The foundation of sHSP role in redox metabolism was mainly laid by work from Arrigo’s laboratory (see references in Arrigo et al., 2007). Although those initial experiments were performed in mouse fibroblasts and human HeLa cells (as opposed to cardiac cells), the pioneering studies by these investigators are being commented here for laying the foundations to the new perspectives being actively explored in cardiovascular redox (patho) biology (see 4.4).

Arrigo’s lab first reported on the effects of HSPB1 and HSPB5 overexpression for mitigating oxidative stress induced in cells treated with the cytokine, TNFalpha or H2O2 and how such maneuvers consequently protect the cells against cell death (Mehlen et al., 1995). To further understand this anti-oxidative property of sHSPs, which are not ROS scavengers by themselves, they investigated the implications of glutathione (GSH), one of the major redox modulators. HSPB1 and HSPB5 overexpression proportionally increases the level of glutathione and this mechanism is required to sustain the protective function of the sHSPs (Mehelen et al., 1996). In an additional study, it was shown that the higher GSH level and the reduced to oxidized (GSH/GSSG) ratio were required for cytoprotection. To address the question of GSH increase, the activity of several enzymes implicated in GSH level was analyzed. Overexpressing HSPB1 reinforces the activity of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) and protein content without changing the G6PD mRNA content. Those studies also reported additional changes in glutathione reductase (GR) and transferase (GST). Altogether, these data are schematically summarized in Figure 2. While the link between protection and level of GSH was well demonstrated by either overexpression of G6PD providing higher GSH level or by directly contributing increased amount of GSH, the molecular interactions between HSPB1 and the implicated enzymes (G6PD, GR, GST) were not fully investigated (Préville et al., 1999).

Figure 2.

Role of HSPB1 and HSPB5 in redox modulation. Schematic illustration is built from data presented in Préville et al. (1999) and references therein. In particular, both sHSPs maintain high activity of G6PD contributing to high level of reduced glutathione GSH. In contrast to HSPB1, HSPB5 also protects catalase activity.

3.2. SMALL HSPS AND GENETIC MAMMALIAN MODEL

Along with investigations in cell culture model, studies using intact organisms are critical to better evaluate the mechanisms involved in redox metabolism and during stress conditions linked to redox imbalance. Multiple mouse models have been created and exploited to determine the role of HSPs in the heart. Most earlier studies have exclusively focused on HSP70, the major stress-linked HSP with the original works describing beneficial effect of transgenic expression of this chaperone in mouse ischemic heart (Marber et al., 1995; Plumier et al., 1995; Radford et al., 1996). Notwithstanding, the number of genetically modified mice have increased to include both loss- and gain-of-function of sHSPs either indirectly (through the stress regulator, HSF1) or directly. Among the cardiac sHSPs presented in Table 1, only HspB7 has not yet been genetically modified in animal models.

As multiple sHSPs are highly expressed in heart, it is likely that they could compensate for each other in defined combinations and thus share some functions. Thus to better understand the sHSP redundancy pattern, it would useful to systematically determine how modifying the expression of one sHSP affects the others. Table 2 summarizes the present wealth of knowledge regarding sHSP mouse models and the existing data on sHSP expression. However, because of the diversity of the models and experimental methods used in the numerous publications about sHSPs, those studies are not easy to compare in order to design a fully comprehensive schema of sHSP roles in cardiovascular system. Notwithstanding, because of the main focus on redox metabolism, we extracted the available data on the major redox couple, GSH/GSSG and ROS production to provide such a global view of sHSP redox capability (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Description of genetically modified mouse models with subsequent variation in gene expression and studies involving those models

| sHSPs coregulation*

|

Other genes | Experimental conditions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up ↑ | Down ↓ | No change | |||

| HSF1 | |||||

|

| |||||

| -KO – Hsf1tm1Ijb (1) | ND | -HSPB1 (3.3 x) | ND | HSPA1 (↓1.5 x) | -basal conditions |

| -HSPB5 (1.6 x) | |||||

| -KO – Hsf1tm1Anak (2) | ND | ND | ND | HSPA1 (↓) | -basal conditions, TAC |

| -KO – Hsf1tm1Miv (3) | ND | -HSPB1 (1.1 x) | ND | -basal conditions | |

| -TG (ΔHSF1)(4) | HSPB1 (2.2 x) | ND | ND | HSPA1 (↑1.85 x) | -basal conditions. I/R, cardiac hypertrophy (TAC, exercise) |

|

| |||||

| HSPB1 | |||||

|

| |||||

| KO – HspB1tm1Msk (5) | - | - | -HspB2,3,5,6,7,8 (mRNA) -HSPB5 | HSPA1 (no change) | -basal conditions |

| -TG(pCAGGS-hHSPB1) (6) | |||||

| TG WT (↑100 x) | -mHSPB1 (0.3 x) | ND | -HSPB5 | ND | -basal conditions, I/R (in vitro) |

| TG mut (P sites)(↑76 x) | -mHSPB1 (0.13 x) | ND | |||

| -TG(αMHC-hHSPB1) (7) | |||||

| TG 85 (↑5.87 x) | ND | HSPB1 (3 x) | HSPB5 | ND | -basal conditions, DOXO treatment |

| TG 21 (↑10.6 x) | |||||

| TG 10 (↑11.7 x) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

|

| |||||

| HSPB5 | |||||

|

| |||||

| -TG(pCAGGS-rHSPB5) (8) | -basal conditions, I/R | ||||

| TG (↑6.9 x) | ND | ND | HSPB1 | ND | |

| -TG(αMHC-mHSPB5) (9) | -basal conditions, R120G control lines, TAC | ||||

| TG 11 (↑4.3 x) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| -TG(αMHC-hHSPB5) (10) | |||||

| TG (↑1.56 x) | - | HSPB1 (0.8 x) | ND | HSPA1(0.4x) | -basal conditions R120G control lines |

| - TG (αMHC-mHSPB5R120G) (9)(15) | |||||

| TG (↑ 2.5 x) | HSPB1(2.57x) HSPB8 (2.4x) |

- | - | HSPA1(↑1.35x) | -basal conditions |

| -TG(αMHC-hHSPB5 R120G) (10) | |||||

| TG (↑ 12.5 x) (6month old) | HSPB1 (3.65x) | - | - | HSPA1(↑1.33x) | -basal conditions |

| -KI HspB5R120G(11) | |||||

| -DKO with HspB2 (12) | HSPB1 (1.1 x) | ND | ND | ND | -basal conditions |

| HSPB2 and 5 (0 x) | -basal conditions, I/R, TAC | ||||

|

| |||||

| HSPB6 | |||||

|

| |||||

| TG(αMHC-hHSPB6) (13) | |||||

| TG Hsp20 WT (↑10 x) | ND | ND | HSPB1, HSPB5 | ND | -basal conditions, I/R, DOXO treatment |

| TG Hsp20S16A(↑7 x) | ND | ND | HSPB1, HSPB5 | ND | |

|

| |||||

| HSPB8 | |||||

|

| |||||

| - TG (αMHC-hHSPB8) (14) | |||||

| TG low (↑2 x), medium | HSPB1 (4.5 x) | ND | ND | HSPA1 (↑11 x) | -basal conditions, I/R |

| (↑4 x) high (↑7 x) | |||||

| -TG (αMHCtetO-HSPB8)(15) | |||||

| TG tTAxTG HSPB8 (↑2 x) | - | - | HSPB1, HSPB5 | - | -basal conditions, R120G triple TG |

| -KO - HspB8(16) | ND | ND | ND | HSPA1 (↑3 x) | -basal conditions, TAC |

References:

Qiu et al. (2011). No animal models have been published for HspB2, HspB3, HspB7.

Coregulation of sHSP level was measured under basal-normal conditions in the heart.

DOXO: exposure to doxorubicin. I/R: ischemia/reperfusion. Mut: mutant. ND: not determined. P sites: phosphorylation sites. TAC: transaortic constriction.

Figure 3.

Schematic comparison of redox metabolism parameters in wild-type (WT) (dark bar) and genetic mouse models (light bar) for sHSPs. Data available in the published literature were exploited to prepare the schematic graphs included in this figure. The corresponding references are indicated accordingly. (A) GSH/GSSG ratio is presented as relative to WT value (=1) obtained in mouse hearts from Hsf1 knockout (Yan et al., 2002), HspB1 transgenic animals (TG) (Zhang et al., 2010), hHspb5 TG (Rajasekaran et al, 2007), HspB2/5 double knockout animals (DKO) (Morrison et al., 2004). (B) Relative levels of various oxidative markers in sHSP mouse model compared with WT (values normalized to 1). O2- was compared in submitochondrial particles isolated in WT and Hsf1 knockout mice (Yan et al., 2002). Production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was measured in WT and HspB1TG (10) (Zhang et al. (2010), HspB6 TG (Fan et al., 2008). Production of malondialdehyde (MDA) as an index of the occurrence of lipid peroxidation and the development of oxidative stress was measured in WT and HspB1 TG (10) (Zhang et al., 2010), hHspB5 TG (Rajasekaran et al., 2007), rHspB5 TG (Ray et al., 2001).

3.2.1. HSF1 loss and gain of function

HSF1 is the master regulator for heat shock response (HSR) as demonstrated by the loss of stress inducible expression of Hsps in cells or tissues from Hsf1 knockout mice (McMillan et al., 1998; Xiao et al., 1999). It is also now well accepted that HSF1 transcriptional activity can be exerted in absence of defined stress: this was similarly revealed by comparing microarray data in Hsf1+/+ and Hsf1−/− animals (Trinklein et al., 2004; Inouye et al., 2004; Le Masson et al., 2011).

More careful examination of sHSP expression in Hsf1−/− hearts showed that the main small Hsps, HSPB1 and HSPB5 are down-regulated (Yan et al., 2002). This was coincident with lower GSH/GSSG ratio and diminished G6PD activity. Thus absence of HSF1 triggers an oxidative imbalance of redox status in hearts maintained otherwise under normal physiological conditions. Although significant, these modifications were not severe enough to alter significantly cardiac function in absence of pathological challenges.

Several transgenic mouse lines were generated to overexpress a constitutively active form of HSF1 (Zou et al., 2003) or to add the Hsf1 human locus into the mouse genome (Pierce et al., 2010). Increased level of HSF1 is expected to elevate the expression of HSF1-dependent sHSPs. This was formally shown for HSPB1 (Table 2) (Zou et al, 2003).

3.2.2. HspB1 (mHsp25) transgenic and knockout mice

Akbar et al (2003) and Hollander et al. (2004) used the same type of transgene to generate transgenic lines overexpressing the human HSPB1. The levels of overexpression were up to 100 fold, which seems particularly high but had no apparent effect on cardiac function in normal/physiological conditions (Hollander et al., 2004). Those models were further studied to determine the role of HSPB1 in ischemic conditions (see 4.1.). A cardiac-specific transgene was exploited by Liu and collaborators (2007) to add increasing amounts of human HSPB1 (hHSPB1) to the endogenous mouse HSPB1. All those transgenic lines created by different laboratories correspond to the addition of hHSPB1 but only the expression of the cardiac-specific transgene reduced the level of the endogenous mHSPB1 (Table 2). This interesting phenomenon has not been explained but warrants investigation as it could indicate some mechanisms regulating the maximum expression allowed for a defined chaperone.

The large series of transgenic lines exhibiting a cardiac specific expression of HSPB1 (five independent lines reported in Liu et al. (2007) and Zhang et al. (2010)) included two lines with remarkable high levels of expression. When HSPB1 is highly overexpressed in the heart, it is associated with reductive stress as demonstrated by increased amount of GSH, 50% reduction in ROS content and 30% reduction in carbonylated proteins (Zhang et al., 2010). Such effects were not obtained with a smaller increase in HSPB1 level. In this study, there was no effect of HSPB1 overexpression on G6PD protein levels, but G6PD activity was not reported. This study did not determine whether the molecular mechanisms causing reductive stress were comparable to those established by Arrigo’s work (Figure 2), which were based on the expected chaperoning function of HSPB1 to elevate G6PD activity (Préville et al., 1999). Nevertheless, Zhang et al. (2010) found a significant impact on another enzyme, glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1), which participates in recycling reduced GSH. From these transgenic studies, it would have been critical to analyze, in parallel, both high expressing lines to better demonstrate the causal link between overexpression of HSPB1 and reductive stress.

HspB1 knockout produced by Huang et al. (2007) exhibited neither any significant abnormality nor any visible transcriptional activation of other sHsps to compensate for the lack of HSPB1. Those animals were not submitted to any cardiac stress so the consequence of HSPB1 deficiency in pathologically relevant cardiac conditions remains unknown.

3.2.3. Hspb2-Hspb5 (MKBP/CryAB) loss-of-function and Hspb5 (CryAB) gain-of-function

Although the initial plan by Brady and collaborators was to generate an HspB5 knockout, the head-to-tail genomic organization of the genes encoding Hspb2 and Hspb5 inadvertently resulted in their genetic targeting procedure provoking the loss-of-function of both Hspb2 and 5 (Brady et al., 2001). This HspB2–5 double knockout (DKO) model lacking two mammalian sHSPs is viable into adulthood and raises possible redundancy between sHSPs. Although both HSPB2 and HSPB5 are developmentally regulated and abundantly expressed in heart, the combined deficiencies neither provoked any major visible anomaly during development nor limited cell growth to relative cardiac hypertrophy (~10% heart weight) in adults (Brady et al., 2001; Pinz et al., 2008; Kumarapelli et al., 2010). Since this DKO mouse line is viable, it has been further exploited to investigate the response to experimental models of cardiac diseases, such as myocardial infarction and work-overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy (see 4.1. and 4.2.).

Regarding redox state regulation, it is interesting to note that Morrison et al. (2004) found a severely diminished level of total GSH, representing 56% of the wild type (WT) hearts and increased amount of the oxidized form, GSSG, in the DKO hearts. All this would indicate that DKO hearts are under higher levels of oxidative stress. Based on the work published by Yan et al. (2002) that showed that HSF1 mutants express lower level of HSPB5 and exhibited reduced GSH, the lower GSH in the DKO mice could be attributed to the lack of HSPB5. Nevertheless, such findings do not rule out the intervention of HSPB2 in redox regulation since this chaperone interacts with the outer membrane of mitochondria (Nakagawa et al., 2001) and is hypothesized to regulate mitochondria energetics.

Taking these data into account, single and cardiac-specific knockouts of HspB2 and HspB5 would be useful to discriminate the different traits of the cardiac phenotype observed in the double knockout. These knockouts would also help avoid confounding effects generated by muscle degeneration, which are responsible for malnutrition and other non-cardiac phenotypes affecting the body weight in aging DKO animals, which ultimately exhibit a reduced lifespan in late adulthood (Brady et al., 2001; Morrison et al., 2004).

Several HspB5 gain-of-function transgenic lines were generated, in particular as a control for a transgenic model expressing the R120G mutant version of HspB5 (see 4.4) (Ray et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2001; Rajasekaran et al., 2007). HSPB5 overexpressing mice have also been studied in experimental models of cardiac disease such myocardial infarction and work-overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy (Ray et al, 2001; Kumapareli et al., 2008, 2010). Those studies have consistently demonstrated the cardioprotective roles of HSPB5 overexpression (see description in sections 4.1 and 4.2).

3.2.4. HspB6 (Hsp20) gain-of-function

Generation of transgenic mice overexpressing HSPB6 was reported in 2005 by Fan and collaborators. As the other transgenic models for cardiac sHSPs, HSPB6 overexpressing mice were submitted to various cardiac challenges, demonstrating the protective role of this chaperone. In addition, while HSPB6 overexpression did not modify cardiac morphology, this higher amount of HSPB6 reinforces the cardiac contractile function (Qian et al., 2011). This is mediated by interaction with type 1 protein phosphatase (PP1) and phospholamban (PBN), protein located in the sarcoplasmic membrane in muscle. HSPB6 inhibits PP1 and thus maintains PBN phosphorylated by inhibition of PP1. When phosphorylated, PBN does not compromise the activity of cardiac muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca++-ATPase (SERCA), which is essential to determine muscle contractility.

There is not yet a published HspB6 loss-of-function animal model, preventing further insights about its requirements for cardiac metabolism and/or (patho) physiological functions.

3.2.5. HspB8 (Hsp22, H11) loss and gain of function

HspB8 is dispensable during early development as the knockout mice created and characterized by Qiu and colleagues (2011) are viable. Nevertheless, HSPB8 overexpression was shown to accumulate in the mitoplasts of transgenic mice. It was shown that that either gain-or loss-of-function of HSPB8 impact mitochondrial respiration (Qiu et al., 2011). Although this was only analyzed in normal conditions without challenge, these data point out a possible interesting interaction of HSPB8 expression in redox homeostasis through its mitochondrial activity.

Several transgenic lines overexpressing HSPB8 were created a decade ago and transgenic animals exhibited a compensated cardiac hypertrophy, correlated to the level of HSPB8 expression (Depre et al., 2002). HSPB8 is thus the second sHSP (with HSPB1, Zhang et al., 2010), for which overexpression induces significant cardiac hypertrophy under non-stress conditions.

4. SMALL HSPS IN CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

In the HSR field, the cellular response is mainly investigated within hours following stress, which means under acute conditions. Cardiovascular diseases instead create chronic stress conditions and this can differently impact the expression of HSPs and their function.

Ultimately, cardiac diseases can provoke congestive heart failure (CHF), leading to death. Animal models of CHF have been exploited to describe this long term-chronic response of sHSPs. Dohke et al. (2006) used an experimental 29-day tachycardia in dogs to induce CHF and perform 2D gel proteomic analysis focusing on HSPB1, HSPB5 and HSPB6 expression. Those sHSPs are significantly more expressed in stressed hearts and also exhibit changes in post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation. This modification alters chaperone function and plays an important role in the oligomerization of sHSPs, in particular HSPB1 (reviewed in Kostenko & Moens, 2009). Nevertheless, those data remain descriptive: is it beneficial or deleterious for cardiomyocyte function to withstand forced expression to existing high level of small HSPs? In addition to the paucity of data collected from patients, more mechanistic studies using the mouse models described in the previous section can provide some answers.

4.1. ISCHEMIA/REPERFUSION

Myocardium Ischemia/Reperfusion (I/R) injury is the consequence of two successive stressful conditions for cardiac cells: 1) the interruption of the blood flow through coronary arteries preventing oxygen – nutrient supply for cardiac cells; and 2) reperfusion in which re-establishing the blood flow exposed hypoxic-anoxic cells to sudden higher level of oxygen with increased ROS production. A key element in the injury process is the burst of ROS produced by affected cells and subsequently the damages arising from this elevated oxidative stress (see additional references on oxidative stress, ROS and I/R in Christians and Benjamin, 2011).

Overexpression of sHSPs was shown to be protective against the I/R insult (Figure 4A, C). One of the first papers that reproduced ischemic conditions analyzed in vitro maintained neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes to determine the effects of overexpressing either HSPB1 or HSPB5 by adenovirus infection (Martin et al., 1997). These investigators took into account the difference between these two types of cells and increased the duration of hypoxic conditions in neonatal cells. Augmented levels of HSPB1 had no protective effect on young cells, in contrast to HSPB5 (Martin et al., 1997). This suggested distinct consequences of ischemic conditions, depending on the age of the organism providing the cardiomyocytes and the different ability of these two HSPs to protect against the respective deleterious challenges.

Figure 4.

Small HSPs and cardiac stress. (A–B) Description of experimental cardiac stresses. (A) Ischemia procedure is shown with the indications for the area of infarction (AOI) corresponding to dead cardiac cells and area at risk (AAR) corresponding to cardiac cells which have experienced the interruption of blood supply (ischemia) before being reperfused. (B) Transaortic constriction (TAC) which increased cardiac work load is schematized. (C) Mouse models of modified sHSP expression were submitted to various protocols of ischemia and reperfusion as illustrated in A. The area of infarction (AOI) to area at risk (AAR) ratio was calculated for HSF1 TG (Zou et al., 2003), hHSPB1 TG (2lines: TG18 and TG24) Efthymiou et al., 2004), HspB2/5 DKO (AMI, acute myocardial infarction; PI, preconditioned infarction) (Benjamin et al., 2007), rHspB5 (Ray et al., 2001), HspB6 TG (Fan et al., 2005), HspB8 TG (Depre et al., 2006). Schematic graph was prepared based on the data referenced above where the ratio values for the experimental animal model (white bar) are presented as relative to the values obtained with wild-type (WT) animals (black bar). (D) Cardiac hypertrophy is measured by the ratio heart weight/body weight (HW/BW). Schematic graph was prepared using published data where the variation of HW/BW in experimental animal models (white bar) is presented as relative to WT ones (black bar), under normal conditions or after transaortic constriction (TAC) as shown in (B). The data are compiled for HSF1 TG (Sakamoto et al., 2006), HSF1 KO (Zou et al., 2011), HspB1(Zhang et al., 2010) HspB2/5 DKO and HSPB5 TG (Kumarapeli et al., 2010), HSPB8 TG (Depre et al., 2002), HSPB8 KO (Qiu et al., 2011).

When Hollander and collaborators performed global ischemia and reperfusion in ex vivo working heart experiments, they found that the transgenic line overexpressing a non phosphorylatable HSPB1 due to mutations on sites of serine 15, 78, 82) showed improved ischemic cardioprotection. This mutant isoform of hHSPB1 exhibited a stronger anti-oxidative capacity as evaluated by lipid peroxidation and protein carbonylation (Hollander et al., 2004).

The HSPB5 overexpressing transgenic line created by Ray et al. (2001) was significantly protected against a 20-minute global ischemia as the percent infarct of total area at risk was reduced by 50%. This was accompanied by a lower production of oxidative stress markers.

HspB6 transgenic mice exhibited protection against ex vivo and in vivo ischemic stress with an infarct size/area at risk ratio reduced by 6 to 2.5 fold, respectively (Fan et al, 2005). This protection is dependent on post-translational modifications, such as the phosphorylation site (S16). Comparable overexpression of HSPB6 without such phosphorylatable site had a dramatic opposite effect with larger size of infarct compared with non-transgenic animals. This could suggest a dominant negative effect of the mutant protein as those animals are still expressing the endogenous genes. Knowing the importance of this post-translational site (PTM site), it would be interesting to determine whether the WT transgenic protein product is proportionally phosphorylated. The mechanisms implicated in the protection observed in the WT HSPB6 and in the mutant HSPB6 transgenic animals were not directly compared. On one hand, HSPB6 interacts with Bax (and not Bcl2) so that under ischemic stress, the ratio Bcl2/Bax increases, mitigating cell death. On the other hand, if HSPB6 cannot be phosphorylated, this prevents activation of the stress-induced autophagy and provokes more cell death (Qian et al., 2009). In addition, absence of S16 phosphorylation modifies the folding of this protein, which can then form larger aggregates under normal conditions. Larger complexes are biochemically identified in protein extracts from ischemic transgenic hearts, but it is not known if these can become cellular aggregates (Qian et al, 2009). Further evidence for an important role of S16 phosphorylation was revealed using a C59T variant identified in the human HSPB6. The S16 site was not postranslationally modified in the variant protein and this significantly reduced the ability of the chaperone to protect cells against stress (Nicolaou et al., 2008). In the context of regenerative medicine, HSPB6 overexpressing mesenchymal cells (HSPB6 MSCs) were injected in experimental ischemic hearts and the effects were compared with the same manipulation using the same cells but without HSPB6 transfection. Through a cell non-autonomous effect relying on the secretion of several factors (e.g. VEGF, FGF2, IGF1), the HSPB6 MSCs were able to stimulate cardiomyocyte survival (Wang et al., 2009).

Reinforced expression of HSPB8 was found to be part of the protective mechanisms triggered in hibernating myocardium, which are chronically dysfunctional but are able to ameliorate through coronary revascularization (Depre et al., 2004). Overexpression of HSPB8 enables a marked reduction of infarct size to a similar extent as ischemic preconditioning (Depre et al., 2006). The chaperone function of HSPB8 would serve to relocate important signalling molecules (such AKT, AMPK) to the nucleus explaining an increased stability of HIF1α, which is instrumental for protection against hypoxia.

Besides the regulation of sHSPs expression in hearts exposed to ischemia, Golenhofen et al. (2004) attempted to determine the distinct interactions of sHSPs with ischemic cardiac myofibrils. HSPB1, −5, −7 become associated with some other components than actin in the myofibrils. HSPB2 and HSPB6 had different biochemical behaviors. By immunofluorescence, HSPB1,−2,−5,−6 were colocalized to myofibrils, in particular in the Z line/I band area.

While the protective effect of sHSPs was demonstrated within the context of several models of gain of function, only the HspB2/5 DKO has been available so far to determine the consequences of sHSP loss-of-function. A first study by Morrison et al. (2004) analyzed the consequences of ex vivo global ischemia on hearts deficient in HspB2 and HspB5. The double knockout hearts exhibited an increased I/R necrosis and apoptosis with a less efficient recovery post ischemia. Interestingly, they had reported a 43% lower level in reduced GSH, which is a critical molecule to buffer the increased oxidative stress following ischemic stress. A second mechanism, which can contribute to weaken HSPB2–5 deficient cardiomyocytes, was an augmented mitochondrial permeability transition and mitochondrial calcium uptake (Kadono et al., 2006). Consistent with this observation, those two sHSPs were found associated with the mitochondria outer membrane (HSPB2: Nakagawa et al., 2001; HSPB5: Whittaker et al., 2009). Furthermore, when HSPB5 was translocated to the mitochondria surface, the level of S-59 phosphorylation increased and this reinforced the protective role of this chaperone (Whittaker et al., 2009). Analyzing the mechanical consequence of I/R in absence of both HSPB2 and -5 chaperones, Golenhofen and collaborators (2006) concluded that ischemic hearts require those chaperones to maintain cellular elasticity rather than contracture process (Golenhofen et al., 2006). Despite the established protective role of HSPB2 and 5, Benjamin et al. (2007) found that lack of both chaperones confer better cell survival following I/R. This apparent discrepancy could result from different ischemic protocols, which could trigger variable response in compensation to the missing sHSPs and comparative analysis of the cardiac transcriptome could solve this question. In an attempt to discriminate the roles played by HSPB2 and HSPB5, other studies took advantage of HSPB5 transgenic mice (Wang et al., 2001) to restore the expression of this chaperone in DKO mice by intercrossing the animals (Pinz et al., 2008). This partially rescued model led to the conclusion that HSPB5 would handle structural remodeling while HSPB2 would be devoted to maintain energetic balance.

In the context of cardiac stress response, the concept of cross tolerance – stress tolerance has been extensively studied under the name of preconditioning or ischemic preconditioning (reviewed in Hausenloy and Yellon, 2011). This is based on the fact that stress of reduced intensity or duration occurring before a major stress is protective. The low-level stress is triggering a protective response, which reduces the damages caused by the subsequent more severe stress (Henle et al., 1978). Distinct sHSPs have been implicated in such preventive mechanisms. For example, experiments by Benjamin et al. (2007) and Armstrong et al. (2000) established that HSPB2 and -5 were not critical to elicit ischemic preconditioning. Of interest, microRNAs identified in cardiac preconditioning have been found to contribute to the regulation of HSPB6 whose overexpression recapitulates the same level of protection as experimental preconditioning (Ren et al., 2009).

4.2. CARDIAC HYPERTROPHY

Cardiac hypertrophy corresponds to an increased cardiac muscle cell volume, since the heart is mostly a non-regenerative, non-proliferative and terminally differentiated organ. Cell growth naturally occurs when increased workload is imposed on the heart and it is often described as adaptive in case of strenuous exercise (e.g. swimming). In contrast, a pathological process more commonly leads to decompensation and heart failure. To recapitulate either adaptative and/or pathological hypertrophy, mouse models are well suited to simulate forced exercise (e.g. swimming, treadmill) or increased pressure overload conditions in aorta or in blood vessels (transaortic constriction, TAC; pharmacologic pressure overload, respectively). Various signaling pathways are differentially involved in cardiac hypertrophy and thus can interfere with sHSP expression (for reviews on cardiac hypertrophy: Heinecke and Molkentin, 2006; Harvey and Leinwand, 2011) (Figure 4B, D).

Very high expression of HSPB1 observed in two transgenic lines (TG 21, TG10) created by Li Liu and collaborators exhibited spontaneous cardiac hypertrophy (30% increased heart/body weight (HW/BW)) (Zhang et al., 2010). HSPB1 had been implicated in redox regulation, impacting the activity of critical enzymes to produce and recycle GSH. As expected, the level of the ratio GSH/GSSG was increased and consequently the level of ROS was decreased in the transgenic heart. This is one of the rare cases of reductive stress where redox homeostasis is severely imbalanced in the opposite direction of oxidation. It is likely that complex molecular mechanisms contribute to link redox status and cardiac hypertrophy since there is example of other transgenic model inducing oxidative stress and increased heart weight.

High level of HSPB1 provokes cardiac hypertrophy while cardiac hypertrophy induced by exercise or pressure overload is accompanied by increased expression of HSPB1 but not HSPA1 (Sakamoto et al., 2006). This suggests that HSPB1 is part of the causal and common molecular response and these characteristics might be shared with another sHSP, HspB8, whose overexpression also causes hypertrophy (Depre et al., 2002).

As described by Kumarapeli et al. (2008), the TAC procedure is rapidly followed by a progressive and significant increase in HSPB5 expression (up to 6 fold within two weeks after surgery). Nevertheless, overexpression of HSPB5 by transgenic means was not accompanied by a marked hypertrophic response (Wang et al, 2001; Kumarapeli et al., 2008; Kumarapeli et al. 2010; Rajasakeran et al., 2007). Furthermore, this transgenic overexpression had a short-term positive effect on TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy, but this seems to be more a delay in the response as 10 weeks after TAC, there was no difference between HW/BW in WT and TG animals. In contrast, the protective role of HSPB5 was better illustrated by the marked aggravation of the phenotype in the combined knockout of Hspb2 and 5 (Kumarapeli et al., 2010).

The regulation of posttranslational modifications might be an important mechanisms to mediate sHSPs intervention in cardiac hypertrophy. Interestingly Sin et al. (2011) showed that HSPB6 is directly interacting with the isoform cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase-4 and this complex reduces HSPB6 phosphorylation. This complex can be disrupted in vitro with designed cell-permeable peptides and HSPB6 phosphorylation is subsequently increased. Phosphorylated HSPB6 attenuates cardiac hypertrophy induced by beta-adrenrgic stimulation (Sin et al., 2011)

Recently, several studies have provided some evidence for a genetic association between HspB7 and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (Cappola et al., 2010; Matkovich et al., 2010 Starck et al., 2010; Villard et al., 2011). So HspB7 would be a candidate gene involved in non-familial cardiomyopathy or could act as a modifier gene of monogenic disease. Generation of HspB7 animal models could help to test this possibility.

Although HspB8 (Hsp22, H11 kinase) as HspB5 is found overexpressed in hypertrophic hearts, it seems that HPB8 by itself is a hypertrophic gene. The series of transgenic lines created by Depre et al. (2002) exhibited spontaneous cardiac hypertrophy proportionally to the level of overexpression: heart size increased by up to 65% when HSPB8 TG level was 7 fold in comparison to non-transgenic. The AKT pathway, which is generally considered as protective, is stimulated by a higher level of HSPB8 and following hypertrophic stress induced by TAC. When HSPB8 is absent, AKT response is severely reduced, which might be the reason why the classical response through HSPA1 (HSP70) is considerably increased (Table 2). From the energetic point of view, HSPB8 was found in the mitochondrial matrix and gain- or loss-of-function of HSPB8 directly impacts mitochondrial respiration (Qiu et al., 2011). Nevertheless the study reported by Qiu et al. (2011) did not include data about the redox status which could be affected through HSPB8 modulation and further contributes to stimulate HSPA1 expression.

4.3. ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is among the most common cardiac dysrhythmias since this pathological condition is diagnosed in about 25% of men and women over 40 years of age. AF imposes rapid and uncoordinated contraction on atrial cardiomyocytes, which provokes severe damages to these cells and is accompanied by Ca2+ overload, disruption of proteostasis and increased oxidative stress. Production of ROS (superoxide) was analyzed in left (LA) and right (RA) atrium by Reilly and collaborators (2011) using a goat model of atrial fibrillation. Their results revealed the heterogeneous increase in ROS production with higher levels detected in the left atrium (2.75 fold in LA versus 1.25 fold in RA). About 30% more ROS are measured in postoperative AF samples. Oxidative stress is further demonstrated by higher levels of protein carbonylation and diminished levels of reduced thiol-SH (Gao and Dudley, 2009).

HspB1 (Hsp25/27) expression, in addition to other HSPs, is modified in chronically affected patients and there is positive correlation between the level of these Hsps and the ability of the patients to restore a sinus rhythm (Yang et al., 2007; Cao et al., 2011). In tachycardia paced HL-1 atrial myocytes, an experimental model of AF, transcriptomic analysis showed a distinct pattern of response among the cardiac sHsps where HspB1, HspB5 and HspB8 increase while HspB2, 3 and 6 are decreased (Mace et al., 2009). HSPB1 and other members of the sHSP family were found to exert beneficial effects through distinct mechanisms. In those experiments, HSPB1, −6, −7 and 8 contributed to rescue the reduced level of Ca2+ transients. HSPB1, −6 and −7 were involved in the structural remodeling of actin stress fibers, and HspB8 specifically acts on RhoA GTPase, an upstream regulator of the cytoskeleton reorganization (Ke et al., 2011). In those studies, the REDOX state was not analyzed, so beyond HSPB1, it remains to be determined whether the other sHSPs highly expressed in the heart can rescue an imbalanced REDOX state such as found in AF.

4.4. HSPB5, A GENETIC ‘eHOT SPOT’f IN SHSP FAMILY: THE CASE OF PROTEIN MISFOLDING AGGREGATION DISEASE

Among the seven cardiac members of the sHsp family, HspB5 is the gene which has been the most frequently mutated in the human population, while some genetic alterations have been reported in HspB1 (but linked to neural disorders), HspB6 and HspB7. Due to the diversity of role executed by the chaperone HSPB5, some of its mutations are accompanied by complex phenotypes causing diseases qualified as multisystemic (Table 3). The impact of the HspB5 mutations on the structure-function relationships is far from being fully understood, so determining why some mutation affects only the lens, the skeletal/cardiac muscle or both remains an intriguing question. The most recent mutation reported in the literature D109H affects Asp 109, which is interacting with Arg120 mutated in HspB5R120G, indicating that this intramolecular interaction is critical for the multiple role of HSPB5 (Sacconi et al., 2012). So far, four mutations caused cardiomyopathy; one of them, reported by Pilotto et al. (2006), pGly154Ser or HspB5G154S, was identified in a patient with mild cardiac dysfunction and no cataract, while the same mutation was found associated to cataract without visible cardiac signs (Table 3). This could indicate that this alteration of HSPB5 could be further submitted to variation according to the genetic background of the patients. Other chaperone-related genes identified for their ability to modulate the cardiac phenotypes linked to HSPB5 in mouse models would be of particular interest in this context and two candidates, BAG3 and HSPB8 have been reported so far for their beneficial interactions regarding another mutation in HSPB5, HspB5R120G (Hishiya et al., 2011; Sanbe et al, 2009).

Table 3.

CryAB mutations and phenotypes

| Mutations | Protein change | Tissue/Organ affected | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EYE | MUSCLE | ||||

|

| |||||

| lens | Skeletal | Cardiac | |||

| 1) 358(cDNA) AtoG | p.Arg120Gly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Vicart et al. (1998) |

| Autosomal Dominant | R120G | ||||

| 2) 350 (cDNA) GtoC | p.Asp109Hist | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sacconi et al. (2012) |

| Autosomal Dominant | D109H | ||||

| 3) n. 495G>A | p.Arg157His | No | No | Yes | Inagaki et al. (2006) |

| Autosomal Dominant | |||||

| 4) n.460G>A | p.Gly154Ser | No | No (subclin) | Yes | Pilotto et al. (2006) |

| Autosomal Dominant | |||||

| 5) n.460G>A | p.Gly154Ser | No | Yes (late onset) | No | Reilich et al. (2010) |

| Autosomal Dom. | |||||

| 6) 2bp deletion 464delCT | C-term truncated protein 162 | No | Yes | No | Selcen and Engel (2003) |

| Autosomal Dominant | AA (18.8kDa) | ||||

| 7) n.451C>T | C-term truncated protein | No | Yes | No | Selcen and Engel (2003) |

| Autosomal Dominant | 150AA (17.5kDa) - Q151X | ||||

| 8) 450delA | Codon frameshift | Yes | No | No | Berry et al. (2001) |

| Autosomal Dominant | Aberrant protein 184 AA | ||||

| K150fs_184X | |||||

| 9) c60C deletion | pSer21AlafsX24 | No | Yes | No | Del Bigio et al. (2011) |

| Cdel60C | Ser 60Ala | ||||

| Autosomal Recessive | Part exon 1- missense aa: Aberrant protein 44 AA | ||||

| 10) c.343delT | p.Ser115ProfsX14 | No | Yes | No | Forrest et al. (2011) |

| Autosomal Recessive | Truncated protein 127 AA | ||||

| 11) n.58C>T | p.P20S | Yes | No | No | Liu et al. (2006a) |

| Autosomal Recessive | |||||

| 12) n.443 G>A | p.D140N | Yes | No | No | Liu et al. (2006b) |

| Autosomal Dominant | |||||

| 13) c.557G>A | p.A171T | Yes | No | No | Devi et al. (2008) |

| Autosomal Dominant | |||||

| 14) c.166C>T | p.R56W | Yes | No | No | Safieh et al. (2009) |

| Autosomal Recessive | |||||

| 15) c.32G>A | p.R11H | Yes | No | No | Chen at al. (2009) |

| Autosomal Dominant | |||||

The R120G mutation, which was identified more than a decade ago as responsible for a form of desmin-related myopathy characterized by adult onset and accumulation of desmin aggregates, associates cardiac disease and reductive stress. A recent review has covered most aspect of the current knowledge about the R120G mutation (McLendon and Robbins, 2011) so we will focus on the molecular mechanisms implicated in perturbing the redox environment.

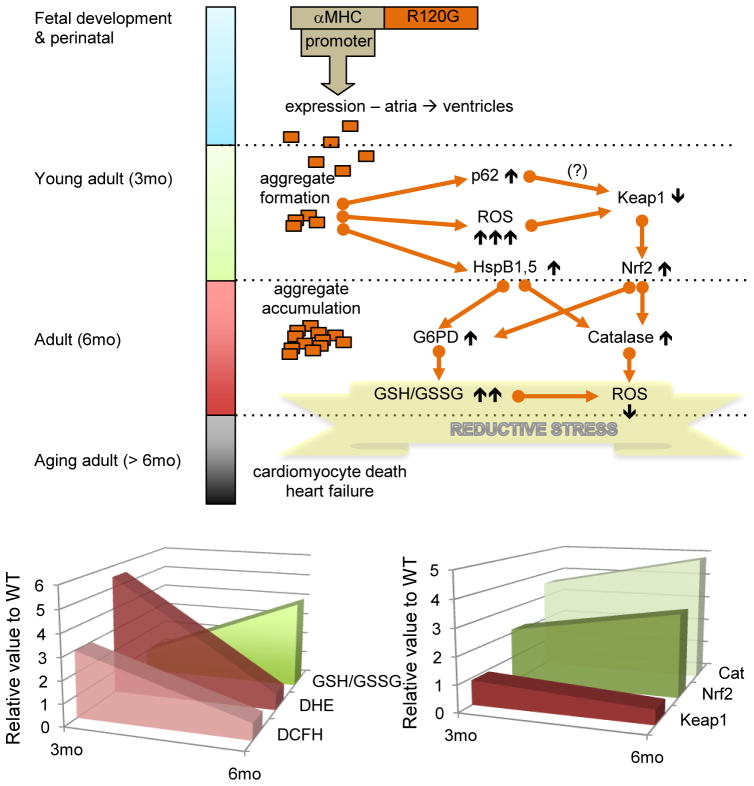

R120G is a dominant mutation so the wild-type version of HSPB5 is expressed along with the mutated form. As an accumulation of misfolded protein, it is expected that HSPB5R120G expression induces the classical stress response which is triggered by proteotoxic stress. The augmented expression of several Hsps (HspB1, HspB5, HspA1-Hsp70 and Hsp90 alpha) was shown in a mouse model of the human disease (Rajasekaran et al., 2007; Rajasekaran et al. 2008) but the requirement for the master regulator of stress response, HSF1, was not formally demonstrated. Higher expression of several chaperones should be protective against oxidative stress and therefore contributes to restore redox homeostasis (see above 3.1). Nevertheless, it seems that high expression of the mutated chaperone leads to sequential redox imbalance, which aggravates the disequilibrium towards reductive stress (Figure 5). In young adults, R120G expression leads to the formation of aggregates and is accompanied by high levels of oxidative stress. Those features are likely responsible to trigger a vigorous antioxidant response through one of the major antioxidant pathway such as Nrf2 (Rajaseakaran et al., 2011). Aggregates exhibit multiple effects from sequestration of critical proteins (HSPB1, KEAP1, G6PD) to mechanical disruption of cardiac sarcomeres. They also stimulate autophagy, which helps to remove accumulated misfolded protein (Tannous et al., 2008). Autophagy through p62 was shown to be involved in the regulation of KEAP1, a negative regulator of Nrf2 (Komatsu et al., 2010), so it could be speculated that p62, which becomes overexpressed in R120G young adult hearts, contributes to enhance this antioxidant pathway (Rajasekaran et al. 2008; Zheng et al., 2011). This pathway then joins the previously described sHSP-dependent G6PD expression-activity (Préville et al., 1999; Rajasekaran et al., 2007) and this further leads to reductive stress.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of R120G molecular mechanisms contributing to reductive stress. The upper panel describes the different phases in the R120G pathological processes as observed in the transgenic model overexpressing the human R120G protein (Rajasekaran et al, 2011). Molecular mechanisms, which evolve during disease progression, are summarized through the flow chart where the different arrows were built based on recent references including experimental data and speculative link indicated by a question mark (?) (Rajasekaran et al., 2007, 2010; Komatsu et al., 2010, Zheng et al, 2011). The lower panel displays two graphs summarizing data to illustrate the shift between oxidative to reductive stress as R120G TG animals, aged from 3 to 6 months. The experimental data is presented as relative value to WT. The graph on the right shows DCFH (fluorescent molecule produced from dihydrodifluoro diacetate (H2DCFDA)) and dihydroethidium (DHE), which are markers of reactive oxygen species and GSH/GSSG ratio which is increased in case of a more reductive environment. The graph on the left reports the relative expression of critical proteins in the oxido-reductive regulation. For additional comments, the reader is referred to the text.

4.5. SMALL HSPS RELATED PHARMACOLOGICALLY INDUCED CARDIAC CELL DEATH

As discussed elsewhere (Christians and Benjamin, 2011), numerous drugs impact the cardiac function on purpose to treat heart disease or, unfortunately, as side effects. Doxorubicin (DOXO), an efficient anticancer molecule, is known for its highly toxic effect on cardiac cells. This has been attributed to the increased level of oxidative stress as illustrated in the work by Li Liu et al. (2007), which showed that a single injection of DOXO increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the heart by 40% within a few days. This is likely responsible for protein alterations triggering a stress response with a complex pattern of gene expression (Fan et al., 2008). Several studies have investigated the role of sHSPs in cardiac cell models and hearts of mouse models exposed to the drug [e.g. mouse models which overexpress sHSPs (transgenic lines): HSPB1 (Li Liu et al. (2007), HSPB6 (Fan et al., 2008) or which are unable to induce Hsp expression due to the loss of HSF1 (Vedam et al., 2010)].

In Li Liu et al. (2007), HSPB1 expression was presented as protective against the higher level of oxidative stress generated following one single injection of doxorubicin, since the level of ROS and carbonylated proteins was four times less augmented in treated transgenic versus non-transgenic animals. Following a three-week doxorubicin treatment (6mg/kg), Vedam et al. (2010) reported a six-fold increase in HSPB1 protein levels in whole heart extract. HSPB1 formed visible aggregates and this was probably due to the combination of a high level of this chaperone and changes in cellular milieu (pH). Nevertheless, this study did not analyze the expression of the other sHSPs, nor the redox state of DOXO-treated hearts. The cardiac cell death is explained by the fact that the phosphorylated form (s-86) of HSPB1, which is similarly augmented, binds p53 so that a stronger expression of proapoptotic Bax is observed. DOXO treated Hsf1−/− animals, which did not induce HspB1 expression because of HSF1 deficiency, were consequently less affected.

This apparent discrepancy between protective and deleterious roles of HSPB1 as described in those two studies reveals the existence of other cellular parameters which are likely to be differently modified by either acute (Liu et al, 2007) and chronic exposure to the drug (Vedam et al., 2010). Another important experimental feature is the use of Hsf1 knockouts to abolish HspB1 induction, since HSF1 has numerous other target genes, which can be involved in this apparent negative effect of HSPB1. This suggests that caution must be applied before using treatment targeting HSF1 activity as they can stimulate the “good” as well the “bad,” mitigating the benefits and rationale of enhanced of enhanced HSPB1 chaperone activity.

Since HspB6 was shown to be downregulated by DOXO treatment (Fan et al., 2008), HspB6 is not naturally part of the DOXO-stress response. Nevertheless, Fan and collaborators demonstrated that elevated level of this chaperone exerts multiple beneficial effects, including reducing the amount of ROS.

5. FUTURE PROSPECTS

In comparison with Hsp70, which has been extensively studied, sHSPs have only recently received more attention in particular in cardiac stress conditions. Among other chaperones and HSP families, sHSPs are of particular interest and importance in cardiovascular diseases because of their high level of expression in the heart, their sustained response under cardiac stress, and their therapeutic potential. Beyond the studies commented in this review, the following questions remain incompletely answered: 1) How does small Hsp gene expression under the control of HSF1, a master regulator for the small Hsps, regulate redox state in the cardiovascular system?; 2) Which cardiac functions are redundant or distinct among cardiac small HSPs during cardiac development and disease states? Although it is somehow surprising that all the genes encoding sHSPs have not yet been knocked out in mice, such models remain the “gold standard” to identify specific biological roles and to determine potential redundancies among sHSPs. Although the sHSPs were considered as not ideal drug targets, a better understanding of their structure and behavior (aggregation, protein-protein interactions) offers new opportunities to design molecules, which could modulate their chaperone properties. For example, innovative screenings have explored ways to interfere with sHSPs, in particular to target the protective role in cancer cells (e.g. peptide aptamers) (Gibert et al., 2011). Besides their biomedical applications, those approaches could be used to complement the genetic models and contribute to the basic knowledge of sHSPs. Since several sHSPSs have been causally linked to human inheritable disorders, a better understanding of sHSP-related mechanisms of disease pathogenesis is also expected from accrued basic knowledge about those chaperones. Finally new cell models such as the patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which can be subsequently differentiated into cardiomyocytes, for example, add invaluable tools for disease modeling and screening for new therapeutic agents targeting sHSPs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (ARRA Award 2 R01 HL063834-06 to IJB), 2009 NIH Director’s Pioneer Award 1DP1OD006438-02, VA Merit Review Award (IJB), and NHLBI 5R01HL074370-03 (IJB). Jamila Roehrig and Alison Ausman provided excellent editorial assistance during preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviation list

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- CryAB

αB-crystallin

- DKO

double knockout

- DOXO

doxorubicin

- Evo-Devo

evolutionary developmental biology

- EST

expressed sequence tag

- G6PD

glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSH

glutathione

- GPx1

glutathione peroxidase 1

- GR

glutathione reductase

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- HSE

heat shock element

- HSF

heat shock factor

- HSR

heat shock response

- I/R

ischemia/reperfusion

- MW

molecular weight

- PP1

type 1 protein phosphatase

- PBN

phospholamban

- PTM

post-translational modification

- (s)HSP

(small) heat shock protein

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TAC

transaortic constriction

- TG

transgenic

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Elisabeth S. Christians, Email: ec1402@yahoo.com.

Takahiro Ishiwata, Email: ishiwata@ndmc.ac.jp.

Ivor J. Benjamin, Email: ivor.benjamin@hsc.utah.edu.

References

- Akbar MT, Lundberg AM, Liu K, et al. The neuroprotective effects of heat shock protein 27 overexpression in transgenic animals against kainate-induced seizures and hippocampal cell death. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19956–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andley UP, Hamilton PD, Ravi N, Weihl CC. A knock-in mouse model for the R120G mutation of alphaB-crystallin recapitulates human hereditary myopathy and cataracts. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong SC, Shivell CL, Ganote CE. Differential translocation or phosphorylation of alpha B crystallin cannot be detected in ischemically preconditioned rabbit cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1301–14. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo AP, Simon S, Gibert B, et al. Hsp27 (HspB1) and alphaB-crystallin (HspB5) as therapeutic targets. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3665–74. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee I, Fuseler JW, Price RL, et al. Determination of cell types and numbers during cardiac development in the neonatal and adult rat and mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1883–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00514.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin IJ, Shelton J, Garry DJ, Richardson JA. Temporospatial expression of the small HSP/alpha B-crystallin in cardiac and skeletal muscle during mouse development. Dev Dyn. 1997;208:75–84. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199701)208:1<75::AID-AJA7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin IJ, Guo Y, Srinivasan S, et al. CRYAB and HSPB2 deficiency alters cardiac metabolism and paradoxically confers protection against myocardial ischemia in aging mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3201–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01363.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry V, Francis P, Reddy MA, et al. Alpha-B crystallin gene (CRYAB) mutation causes dominant congenital posterior polar cataract in humans. Am Journal Hum Genet. 2001;69:1141–5. doi: 10.1086/324158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady JP, Garland DL, Green DE, et al. AlphaB-crystallin in lens development and muscle integrity: a gene knockout approach. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2924–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat SP, Nagineni CN. alpha B subunit of lens-specific protein alpha-crystallin is present in other ocular and non-ocular tissues. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1989;158:319–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(89)80215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Xue L, Xu X, et al. Heat shock proteins in stabilization of spontaneously restored sinus rhythm in permanent atrial fibrillation patients after mitral valve surgery. Cell stress & chaperones. 2011;16:517–28. doi: 10.1007/s12192-011-0263-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappola TP, Li M, He J, et al. Common variants in HSPB7 and FRMD4B associated with advanced heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Genetics. 2010;3:147–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.898395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers GJ, Leunissen JA, de Jong WW. The expanding small heat-shock protein family, and structure predictions of the conserved “alpha-crystallin domain”. J Mol Evol. 1995;40:238–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00163229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Ma J, Yan M, et al. A novel mutation in CRYAB associated with autosomal dominant congenital nuclear cataract in a Chinese family. Mol Vis. 2009;15:1359–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christians ES, Benjamin IJ. Proteostasis and Redox state in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012:H24–27. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00903.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danan IJ, Rashed ER, Depre C. Therapeutic potential of H11 kinase for the ischemic heart. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2007;25:14–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2007.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bigio MR, Chudley AE, Sarnat HB, et al. Infantile muscular dystrophy in Canadian aboriginals is an alphaB-crystallinopathy. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:866–71. doi: 10.1002/ana.22331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depre C, Hase M, Gaussin V, et al. H11 kinase is a novel mediator of myocardial hypertrophy in vivo. Circ Res. 2002;91:1007–14. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000044380.54893.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depre C, Kim SJ, John AS, et al. Program of cell survival underlying human and experimental hibernating myocardium. Circ Res. 2004;95:433–40. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000138301.42713.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depre C, Wang L, Sui X, et al. H11 kinase prevents myocardial infarction by preemptive preconditioning of the heart. Circ Res. 2006;98:280–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000201284.45482.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi RR, Yao W, Vijayalakshmi P, et al. Crystallin gene mutations in Indian families with inherited pediatric cataract. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1157–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Roux G, Banfi S, Sultan M, et al. A high-resolution anatomical atlas of the transcriptome in the mouse embryo. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohke T, Wada A, Isono T, et al. Proteomic analysis reveals significant alternations of cardiac small heat shock protein expression in congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreiza CM, Komalavilas P, Furnish EJ, et al. The small heat shock protein, HSPB6, in muscle function and disease. Cell stress & chaperones. 2010;15:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12192-009-0127-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards HV, Cameron RT, Baillie GS. The emerging role of HSP20 as a multifunctional protective agent. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1447–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efthymiou CA, Mocanu MM, de Belleroche J, et al. Heat shock protein 27 protects the heart against myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2004;99:392–4. doi: 10.1007/s00395-004-0483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elicker KS, Hutson LD. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiling of the small heat shock proteins in zebrafish. Gene. 2007;403:60–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan GC, Ren X, Qian J, et al. Novel cardioprotective role of a small heat-shock protein, Hsp20, against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2005;111:1792–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160851.41872.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan GC, Zhou X, Wang X, et al. Heat shock protein 20 interacting with phosphorylated Akt reduces doxorubicin-triggered oxidative stress and cardiotoxicity. Circ Res. 2008;103:1270–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan GC, Kranias EG. Small heat shock protein 20 (HspB6) in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:574–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck E, Madsen O, van Rheede T, et al. Evolutionary diversity of vertebrate small heat shock proteins. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:792–805. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0013-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest KM, Al-Sarraj S, Sewry C, et al. Infantile onset myofibrillar myopathy due to recessive CRYAB mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2011;21:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Dudley SC., Jr Redox regulation, NF-kappaB, and atrial fibrillation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2265–77. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gernold M, Knauf U, Gaestel M, et al. Development and tissue-specific distribution of mouse small heat shock protein hsp25. Dev Genet. 1993;14:103–11. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020140204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Saber H, Ferns GA. The potential role of heat shock protein 27 in cardiovascular disease. Clinica chimica acta. 2012;413:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibert B, Hadchity E, Czekalla A, et al. Inhibition of heat shock protein 27 (HspB1) tumorigenic functions by peptide aptamers. Oncogene. 2011;30:3672–81. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golenhofen N, Ness W, Koob R, et al. Ischemia-induced phosphorylation and translocation of stress protein alpha B-crystallin to Z lines of myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H1457–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.5.H1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golenhofen N, Perng MD, Quinlan RA, Drenckhahn D. Comparison of the small heat shock proteins alphaB-crystallin, MKBP, HSP25, HSP20, and cvHSP in heart and skeletal muscle. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122:415–25. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0711-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golenhofen N, Redel A, Wawrousek EF, Drenckhahn D. Ischemia-induced increase of stiffness of alphaB-crystallin/HSPB2-deficient myocardium. Pflugers Arch. 2006;451:518–25. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1488-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Bradshaw AD, Schwacke JH, et al. Quantification of protein expression changes in the aging left ventricle of Rattus norvegicus. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:4252–63. doi: 10.1021/pr900297f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PA, Leinwand LA. The cell biology of disease: cellular mechanisms of cardiomyopathy. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:355–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201101100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. The therapeutic potential of ischemic conditioning: an update. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:619–29. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henle KJ, Dethlefsen LA. Heat fractionation and thermotolerance: a review. Cancer Res. 1978;38:1843–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander JM, Martin JL, Belke DD, et al. Overexpression of wild-type heat shock protein 27 and a nonphosphorylatable heat shock protein 27 mutant protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in a transgenic mouse model. Circulation. 2004;110:3544–52. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148825.99184.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hishiya A, Salman MN, Carra S, et al. BAG3 directly interacts with mutated alphaB-crystallin to suppress its aggregation and toxicity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]