Abstract

Objectives To evaluate the efficacy and safety of currently used drug eluting stents compared with each other and compared with bare metal stents in patients with diabetes.

Design Mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis.

Data sources and study selection PubMed, Embase, and CENTRAL were searched for randomised clinical trials, until April 2012, of four durable polymer drug eluting stents (sirolimus eluting stents, paclitaxel eluting stents, everolimus eluting stents, and zotarolimus eluting stents) compared with each other or with bare metal stents for the treatment of de novo coronary lesions and enrolling at least 50 patients with diabetes.

Primary outcomes Efficacy (target vessel revascularisation) and safety (death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis).

Results From 42 trials with 22 844 patient years of follow-up, when compared with bare metal stents (reference rate ratio 1) all of the currently used drug eluting stents were associated with a significant reduction in target vessel revascularisation (37% to 69%), though the efficacy varied with the type of stent (everolimus eluting stents∼sirolimus eluting stents>paclitaxel eluting stents∼zotarolimus eluting stent>bare metal stents). There was about an 87% probability that everolimus eluting stents were the most efficacious compared with all others, though there were limited usable data for the zotarolimus eluting Resolute stent in patients with diabetes. Moreover, there was no increased risk of any safety outcome (including very late stent thrombosis) with any drug eluting stents compared with bare metal stents. There was about a 62% probability that the everolimus eluting stent was the safest stent for the outcome of “any” stent thrombosis.

Conclusions Among patients with diabetes treated with coronary stents all currently available drug eluting stents were efficacious without compromising safety compared with bare metal stents. There were relative differences among the drug eluting stents, such that the everolimus eluting stent was the most efficacious and safe.

Introduction

The presence of diabetes has been associated with worse outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention with bare metal stents and drug eluting stents.1 2 3 4 While drug eluting stents have reduced the risk of restenosis, there is controversy as to the relative efficacy of various drug eluting stents in patients with diabetes. Several subgroup analyses from patients with diabetes enrolled in randomised clinical trials, pooled analyses from the diabetic subgroups of randomised controlled trials, and several registry studies5 6 7 suggest that the paclitaxel eluting stent might provide similar benefits to sirolimus eluting stents and everolimus eluting stents. Other analyses derived from randomised controlled trials, however, have reached different conclusions, showing sirolimus eluting stents to be superior to paclitaxel eluting stents.8 Dedicated randomised controlled trials in patients with diabetes have shown that sirolimus eluting stents are superior to paclitaxel eluting stents.9 10 11 The long term efficacy and safety of the various drug eluting stents and bare metal stents in patients with diabetes is therefore controversial. This issue has important implications for the selection of the most effective treatment in these high risk patients. Accordingly, we examined the relative safety and efficacy of various drug eluting stents compared with bare metal stents and each other among patients with diabetes.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We searched PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) for randomised clinical trials using the terms: “drug eluting stent”, “bare metal stent”, and the names of individual durable polymer drug eluting stent systems (sirolimus eluting stents, paclitaxel eluting stents, everolimus eluting stents, and zotarolimus eluting stents) until April 2012 (week 1). Table A in appendix 1 lists the search terms. We checked the reference lists of review articles, meta-analyses, and original studies identified by the electronic searches to find other eligible trials. There was no language restriction for the search. In addition, we searched conference proceedings/abstracts from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics, Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, European Society of Cardiology, and Euro-PCR. For studies that did not report outcomes of interest we contacted the authors via email. In addition, we reviewed the Food and Drug Administration dockets for all documents submitted during the stent approval process.

To be eligible for inclusion, trials had to be randomised controlled trials comparing the above drug eluting stents either with a different drug eluting stents or with bare metal stents in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention of a de novo coronary lesion; enrol patients with diabetes or report data on a diabetes subgroup; enrol at least 50 patients with follow-up of at least six months, and report the outcomes of interest. We excluded trials that used bioabsorbable stent or polymer, non-polymer stents, stents with eluting drugs other than the four compared (above), and trials that used balloon angioplasty alone or compared stents with coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

The search process was fairly extensive, and efforts were made to obtain the longest reported follow-up data from a combination of sources: all the published trial data, presentations at national meetings, unpublished data from communication with authors, data published in previous meta-analyses, and data from pooled patient level meta-analyses.

Selection and quality assessment

Four authors (SB, SK, MF, NA) independently assessed trial eligibility and risk of bias and extracted data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Risk of bias was assessed with the components recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration12: sequence generation of the allocation; concealment of allocation; blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors; use of intention to treat analysis; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias. As none of the trials blinded participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors was considered as an indicator of low risk of bias for the blinding component of the quality analysis. Trials with high or unclear risk for bias for any one of the first three components were considered as trials with high risk of bias. In addition, all analyses were performed with an intention to treat principle. Otherwise, they were considered as trials with low risk of bias.

Data extraction and synthesis

We evaluated efficacy and safety outcomes. Efficacy outcomes were target vessel revascularisation and target lesion revascularisation. Safety outcomes were death, myocardial infarction, and stent thrombosis. Four types of stent thrombosis were evaluated: “any” stent thrombosis (based on the trial definition of stent thrombosis), “definite” or “probable” stent thrombosis as defined by the Academic Research Consortium,13 “definite” stent thrombosis as defined by the Academic Research Consortium, and very late stent thrombosis (stent thrombosis >12 months). For these outcomes, we abstracted the longest reported follow-up events.

Statistical analyses

Mixed treatment comparisons

We used Bayesian models for mixed treatment comparison to compare the different types of stent. For the purpose of analysis, we defined five stent types: bare metal stents, sirolimus eluting stents, paclitaxel eluting stents, everolimus eluting stents, and zotarolimus eluting stents. Analysis was performed with an intention to treat principle for all included trials. The primary analysis compared each individual drug eluting stent with bare metal stents, which was used as reference. This was performed with WinBUGS code written by the UK Medical Research Council health services research collaboration.14 The mixed treatment comparison allows for comparisons of agents not directly addressed within any of the individual trials. In addition to analysing the direct within trial comparisons between two stents (such as stent A v B), the framework enabled us to incorporate the indirect comparisons constructed from two trials that have one stent type in common (such as comparison of stent A v C using trials comparing A v B and B v C). This type of analysis has the advantage of maintaining the randomised treatment comparisons within each trial while combining all available comparisons between treatments.

We fitted a random effects Poisson regression model, taking into account the correlation structure induced by the multi-arm trials.15 We used a random effects rather than a fixed effects model as this is probably the most appropriate and conservative analysis to account for variance within and between studies. For the purpose of analysis, given the variability in the length of follow-up for each of these trials, we used the rate of outcomes per 1000 person years to obtain the log rate ratio of one stent relative to another. We considered rates, rather than number of events, as the most appropriate outcome for these analyses because they incorporate the duration of the trials, which was variable. We calculated patient years of follow-up for each trial by multiplying the trial sample size with the mean duration of follow-up of the trial. Rate ratios were estimated from the median and the accompanying 95% credibility intervals from the 2.5th and 97.5th centiles of the posterior distribution.

We evaluated heterogeneity between trials, defined as variability of results across trials within comparisons over and above chance based on previous methods.16 A τ2 estimate of 0.04 is interpreted as a low, 0.14 as a moderate, and 0.40 as a high degree of heterogeneity between trials. In addition, we estimated the goodness of fit of the model to the data using previously described methods.16 The model was considered to provide an adequate fit to the data if the mean of the residual deviance was similar to the number of data points used in the model; at least 95% of means of standardised node based residuals were within 1.96 SD (standard deviation) of the standard normal distribution; and Q-Q plots of residuals lay closely around a line on visual inspection.16 We evaluated the inconsistency of the network, defined as the variability of results across different comparisons of the network, by calculating the rate ratio of the direct comparison meta-analysis as described below.

Calculation of the probability that each treatment is best (lowest event proportion) was performed with a Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method, adapted to apply to a connected network set of treatment comparisons. We used minimally informative previous distributions for log rate ratios and for random effects standard deviations, so that the findings can be interpreted similarly to findings from frequentist methods. All network analyses were conducted with WinBUGS 1.4.3.

Direct comparison analyses

Direct comparison meta-analysis was performed in line with recommendations from the Cochrane Collaboration and the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) statement,12 17 with standard software (Stata 9.0, StataCorp, TX).18 The pooled effect for each grouping of trials was derived from the point estimate for each separate trial weighted by the inverse of the variance (1/SE2). The rate ratio was calculated with the random effects model of DerSimonian and Laird.19 All analyses were carried out with a random effects model given probable clinical heterogeneity in study design between trials regardless of statistical homogeneity.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses to test for the robustness of the primary analyses. Analyses were restricted to trials with a low risk of bias; trials limited to patients without acute coronary syndrome (to avoid confounding effect of acute coronary syndrome subgroup; an acute coronary syndrome trial was defined as a trial in which over half of patients enrolled had acute coronary syndrome (unstable angina, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, or ST segment elevation myocardial infarction) as the reason for percutaneous coronary intervention); and trials in which the duration of treatment with clopidogrel in the drug eluting stent arm was at least six months (to avoid any confounding effect of shorter duration of treatment on safety outcomes). We also performed a sensitivity analysis after including the only two trials published thus far on zotarolimus eluting Resolute stent (TWENTE77 and RESOLUTE All comers35 trials). Both the trials reported only target lesion failure and target vessel failure, respectively. For the purposes of this analysis, we used these as a substitute for target vessel revascularisation. This analysis on the zotarolimus eluting Resolute stent should therefore be viewed as highly exploratory.

Results

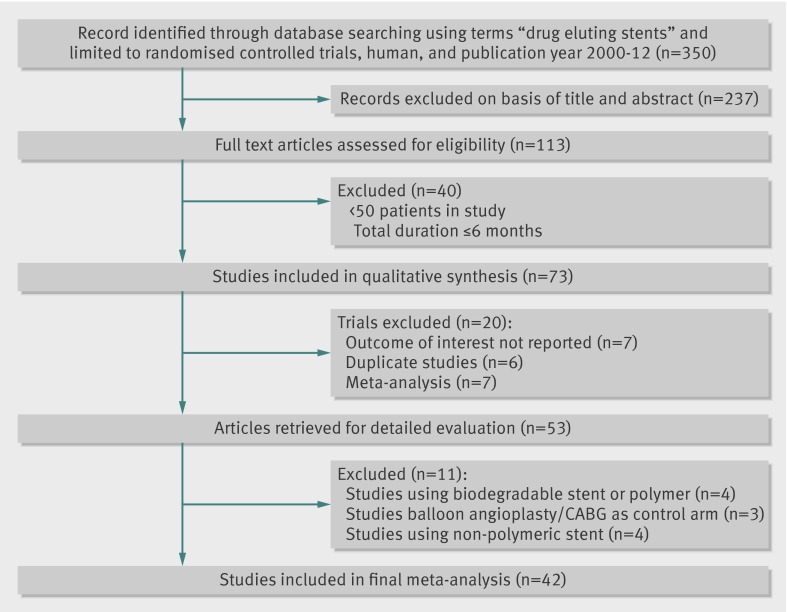

Study selection

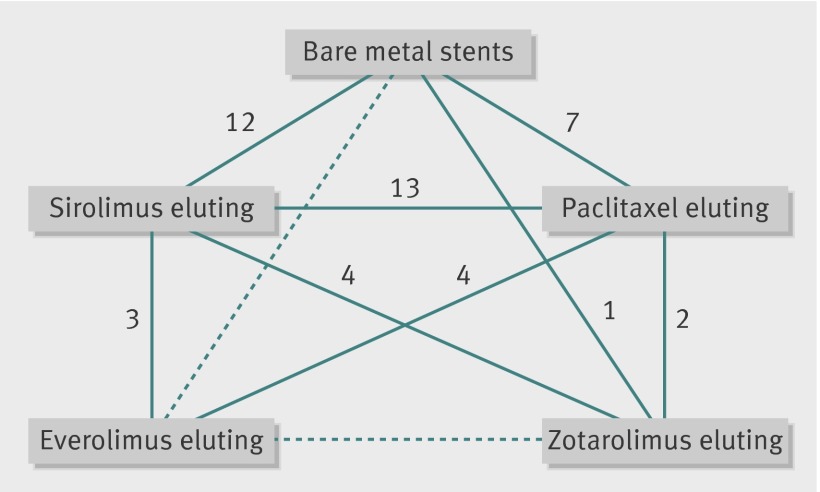

We identified 42 randomised controlled trials that satisfied our inclusion criteria (fig 1). For the SPIRIT and COMPARE trials, we used the pooled data in patients with diabetes that was recently published as this provided more comprehensive longer term data than the published individual trials for the diabetic subgroup.20 Figure 2 shows the network of available treatment comparisons.

Fig 1 Selection of studies examining efficacy or safety, or both, of various drug eluting or bare metal stents in patients with diabetes mellitus

Fig 2 Network of comparisons of types of stents in studies examining efficacy or safety, or safety, of various drug eluting or bare metal stents in patients with diabetes mellitus. Links between stent types represent direct comparisons (solid line) or indirect comparisons (dashed line). Numbers along links represent number of trial arms providing direct comparison between stent types

Characteristics of included trials

Tables 1 and 2 describe the trial characteristics and quality analysis. The 42 trials enrolled 10 714 patients with 22 844 patient years of follow-up. Two trials were three arm trials, but the rest were two arm trials. Thirty seven trials were considered to be at low risk of bias, while five were at intermediate or high risk of bias. In 34 of the 42 trials, clopidogrel was used for at least six months in the drug eluting stents arm (table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included trials examining efficacy or safety, or both, of various drug eluting or bare metal stents in patients with diabetes mellitus

| Trial | Year | Total No | Comparisons | Follow-up (months) | Mean age (years) | Men (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASKET16 40 | 2005 | 153 | SES/PES/BMS | 24 | 64 | 79 |

| CORPAL16 41 | 2005 | 202 | SES/PES | 36 | 61 | 77 |

| DECODE42 | 2008 | 83 | SES/BMS | 12 | 60 | 68 |

| DES-Diabetes9 10 | 2009-09 | 400 | SES/PES | 48 | 61 | 58 |

| DESSERT43 | 2008 | 150 | SES/BMS | 42 | 70 | 56 |

| DIABETES44 45 | 2005-11 | 160 | SES/BMS | 60 | 67 | 63 |

| DiabeDES46 | 2009 | 152 | SES/PES | 8 | 65 | 79 |

| Endeavor II47 | 2006 | 239 | ZES/BMS | 9 | NR | NR |

| Endeavor III48 | 2011 | 128 | SES/ZES | 24 | NR | NR |

| Endeavor IV49 | 2009 | 477 | ZES/PES | 12 | 64 | 61 |

| E-SIRIUS16 50 | 2003 | 81 | SES/BMS | 48 | 61 | 71 |

| ESSENCE-DIABETES51 | 2011 | 300 | EES/SES | 12 | 64 | 59 |

| Hong et al52 | 2010 | 169 | SES/PES | 36 | 66 | 74 |

| HORIZONS-AMI53 | 2011 | 478 | PES/BMS | 12 | 64 | 71 |

| ISAR-Diabetes11 | 2005 | 250 | SES/PES | 9 | 68 | 73 |

| ISAR-LeFt Main54 | 2009 | 176 | SES/PES | 12 | NR | NR |

| ISAR-TEST 255 56* | 2009-10 | 180 | SES/ZES | 36 | NR | NR |

| Kim et al57 | 2008 | 169 | SES/PES | 6 | 62 | 74 |

| LONG-DES II16 58 | 2006 | 166 | SES/PES | 24 | 61 | 64 |

| Naples-diabetes59 | 2011 | 226 | SES/PES/ZES | 36 | 64 | 57 |

| Pache et al16 60 | 2005 | 154 | SES/BMS | 48 | 67 | 78 |

| PASSION16 61 | 2006 | 68 | PES/BMS | 12 | 61 | 76 |

| REALITY16 62 | 2006 | 379 | SES/PES | 36 | 63 | 72 |

| RESET63 | 2011 | 1439 | SES/EES | 12 | NR | NR |

| SCANDSTENT16 64 | 2006 | 58 | SES/BMS | 12 | 63 | 77 |

| SCORPIUS65 66 | 2007 | 190 | SES/BMS | 12 | 66 | 64 |

| SESAMI16 67 | 2007 | 65 | SES/BMS | 24 | 62 | NR |

| SES-SMART68 | 2005 | 74 | SES/BMS | 8 | 65 | 70 |

| SIRIUS16 69 | 2004 | 279 | SES/BMS | 48 | 62 | 61 |

| SIRTAX8 16 | 2008 | 201 | SES/PES | 24 | 62 | 71 |

| SORT OUT III34 | 2011 | 337 | ZES/SES | 18 | 66 | 72 |

| SORT OUT IV70 | 2011 | 390 | EES/SES | 18 | NR | NR |

| SPIRIT II,III, IV, and COMPARE pooled20 | 2011 | 1869 | EES/PES | 24 | 64 | 63 |

| TAXi16 71 | 2004 | 69 | SES/PES | 36 | 64 | 80 |

| TAXUS II16 72 | 2003 | 51 | PES/BMS | 48 | 62 | 76 |

| TAXUS IV16 73 | 2005 | 318 | PES/BMS | 48 | 62 | 64 |

| TAXUS V16 74 | 2005 | 356 | PES/BMS | 24 | 63 | 69 |

| TAXUS VI16 75 | 2005 | 89 | PES/BMS | 36 | 62 | 76 |

| TYPHOON16 76 | 2006 | 116 | SES/BMS | 12 | 59 | 78 |

NR=not reported; BMS=bare metal stent; EES=everolimus eluting stent; PES=paclitaxel eluting stent; SES=sirolimus eluting stent; ZES=zotarolimus eluting stent.

*Three year data; R Byrne, personal communication.

Table 2.

Selected characteristics of included trials examining efficacy and/or safety of various drug eluting or bare metal stents in patients with diabetes mellitus

| Study | Diabetes as prespecified analysis | Duration of clopidogrel (>6 months) use | Quality of study* |

|---|---|---|---|

| BASKET16 40 | No | Yes | +++ |

| CORPAL16 41 | No | NR | +±± |

| DECODE42 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| DES-Diabetes9 10 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| DESSERT43 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| DIABETES44 45 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| DiabeDES46 | Yes | Yes | ++± |

| Endeavor II47 | No | No | +++ |

| Endeavor III48 | No | No | +++ |

| Endeavor IV49 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| E-SIRIUS16 50 | No | No | +++ |

| ESSENCE-DIABETES51 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| Hong et al52 | Yes | Yes | ++± |

| HORIZONS-AMI53 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| ISAR-Diabetes11 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| ISAR-LeFt Main54 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| ISAR-TEST 255 56 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| Kim et al57 | Yes | Yes | +±± |

| LONG-DES II16 58 | No | Yes | +++ |

| Naples-diabetes59 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| Pache et al16 60 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| PASSION16 61 | No | Yes | +++ |

| REALITY16 62 | No | Yes | +++ |

| RESET63 | Yes | NR | +++ |

| SCANDSTENT16 64 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| SCORPIUS65 66 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| SESAMI16 67 | No | Yes | +++ |

| SES-SMART68 | No | No | +++ |

| SIRIUS16 69 | No | No | +++ |

| SIRTAX8 16 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| SORT OUT III34 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| SORT OUT IV70 | NR | Yes | +++ |

| SPIRIT II,III, IV and COMPARE pooled20 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| TAXi16 71 | No | NR | +±± |

| TAXUS II16 72 | No | Yes | +++ |

| TAXUS IV16 73 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| TAXUS V16 74 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| TAXUS VI16 75 | Yes | Yes | +++ |

| TYPHOON16 76 | No | Yes | +++ |

NR= not reported.

*Represents risk of bias based on: sequence generation of allocation; allocation concealment and blinding; + represents low risk of bias, − represents high risk of bias, and ± represents unclear risk.

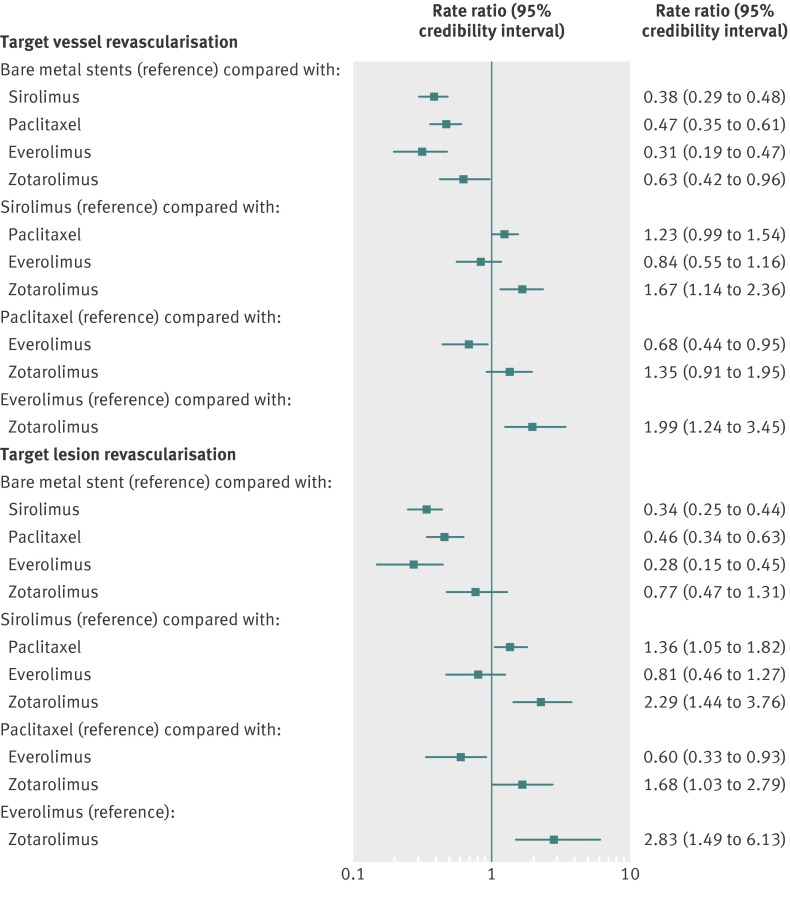

Efficacy outcomes

When compared with bare metal stents (reference rate ratio of 1), all drug eluting stents were associated with a 37% to 69% reduction in the rate of target vessel revascularisation (fig 3), but the magnitude of this reduction varied with the type of stent. Sirolimus eluting stents were significantly more efficacious than zotarolimus eluting stents but similar to paclitaxel eluting stents or everolimus eluting stents. In the comparison between sirolimus eluting stents and paclitaxel eluting stents, however, the point estimate favoured sirolimus eluting stents (fig 3). Similarly, everolimus eluting stents were more efficacious than paclitaxel eluting stents or zotarolimus eluting stent. There was an 87% probability that everolimus eluting stents have the lowest rate of target vessel revascularisation (table 3) compared with all other stent types. The median target vessel revascularisation rate with bare metal stents was 109.40 per 1000 patient years of follow-up, and the rate with the most efficacious drug eluting stent (everolimus eluting stent) was 34.55 per 1000 patient years (table 3).

Fig 3 Stent type and risk of target vessel revascularisation and target lesion revascularisation with 95% credibility intervals

Table 3.

Rate (per 1000 patient years of follow-up) of selected efficacy and safety outcomes with 95% credibility intervals and the probability that each stent type is the best (lowest rate) from mixed treatment comparison analysis

| Bare metal | Sirolimus | Paclitaxel | Everolimus | Zotarolimus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target vessel revascularisation | 109.40 (95.10 to 124.60) | 41.51 (32.51 to 51.45) | 51.14 (39.00 to 64.98) | 34.55 (21.36 to 50.62) | 68.72 (45.70 to 102.50) |

| Probability of being best | 0.00% | 12.44% | 0.26% | 87.22% | 0.08% |

| Death | 17.51 (11.33 to 27.75) | 17.58 (10.85 to 28.87) | 16.99 (10.25 to 28.54) | 14.51 (6.76 to 29.67) | 20.27 (9.24 to 43.31) |

| Probability of being best | 11.59% | 7.13% | 11.52% | 56.63% | 13.13% |

| Myocardial infarction | 19.16 (12.31 to 30.35) | 13.83 (8.31 to 22.88) | 15.84 (9.27 to 26.81) | 10.13 (3.92 to 22.83) | 41.70 (15.66 to 163.4) |

| Probability of being best | 0.49% | 16.71% | 2.15% | 80.58% | 0.07% |

| Any stent thrombosis | 1.49 (0.60 to 3.71) | 0.96 (0.36 to 2.60) | 1.19 (0.44 to 3.35) | 0.82 (0.22 to 2.86) | 4.16 (0.75 to 26.64) |

| Probability of being best | 1.98% | 29.57% | 4.53% | 61.87% | 2.05% |

| Definite/probable* stent thrombosis | 0.91 (0.33 to 2.49) | 0.47 (0.15 to 1.39) | 0.64 (0.2 to 1.98) | 0.39 (0.08 to 1.55) | 3.61 (0.63 to 23.66) |

| Probability of being best | 0.74% | 28.40% | 3.38% | 67.41% | 0.07% |

*According to Academic Research Consortium definitions

The results were largely similar in the sensitivity analyses that included only trials in which patients had used clopidogrel for more than six months (fig A1 in appendix 2); in trials with low bias risk (table B in appendix 1); that excluding acute coronary syndrome trials (table C in appendix 1); and in the direct comparison meta-analysis (table D in appendix 1). For the outcome of target lesion revascularisation the results were largely similar, except that the results of the comparison between bare metal stents and zotarolimus eluting stent was no longer significant (trend favouring zotarolimus eluting stent) and sirolimus eluting stents were significantly more efficacious than paclitaxel eluting stents (fig 3 and fig A2 in appendix 2).

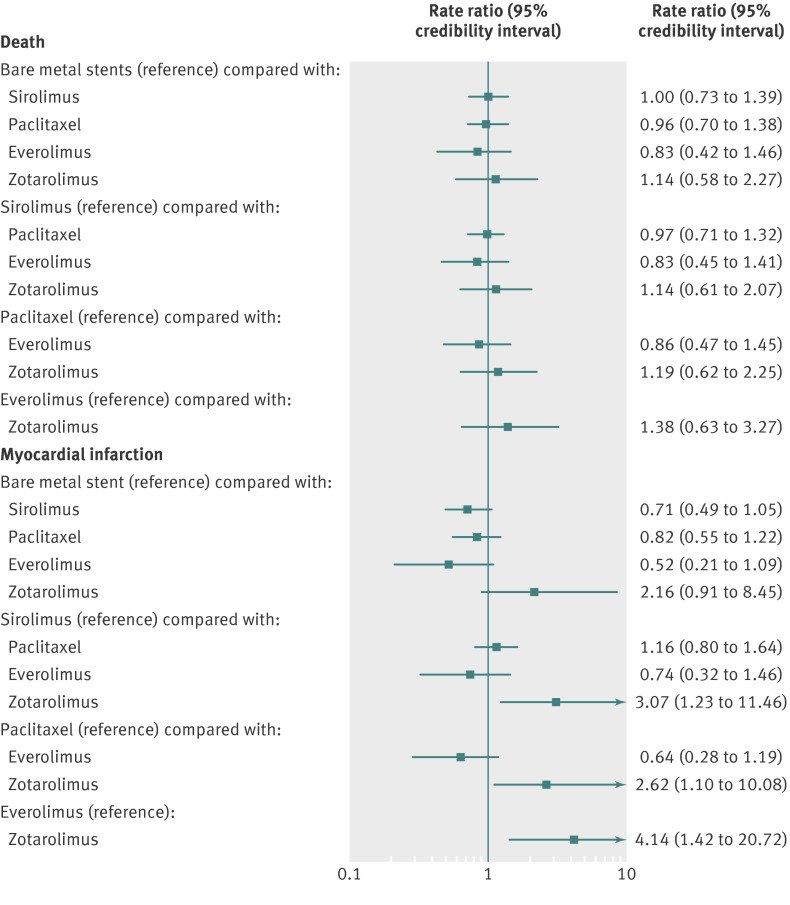

Safety outcomes

Compared with bare metal stents, there was no increase in death with any of the drug eluting stents or among any comparisons between pairs of drug eluting stents (fig 4). The median death rate with bare metal stents was 17.51 per 1000 patient years of follow-up (table 3). The median death rate with drug eluting stents varied between 14.51 and 20.27 per 1000 patient years (table 3). There was a 57% probability that everolimus eluting stents was associated with the lowest death rate (table 3).

Fig 4 Stent type and risk of myocardial infarction and death with 95% credibility intervals

For the outcome of myocardial infarction, there was no significant increase with any of the drug eluting stents compared with bare metal stents (fig 4). Among types of drug eluting stent, sirolimus eluting stents, paclitaxel eluting stents, and everolimus eluting stents were all associated with a lower rate of myocardial infarction compared with zotarolimus eluting stents (fig 4). The credibility interval around the increased risk with the zotarolimus eluting stent, however, was rather wide (fig 4). The median rate of myocardial infarction with bare metal stents was 19.16 per 1000 patient years. There was an 81% probability that everolimus eluting stents had the lowest rate of myocardial infarction with a rate of 10.13 per 1000 patient years (table 3).

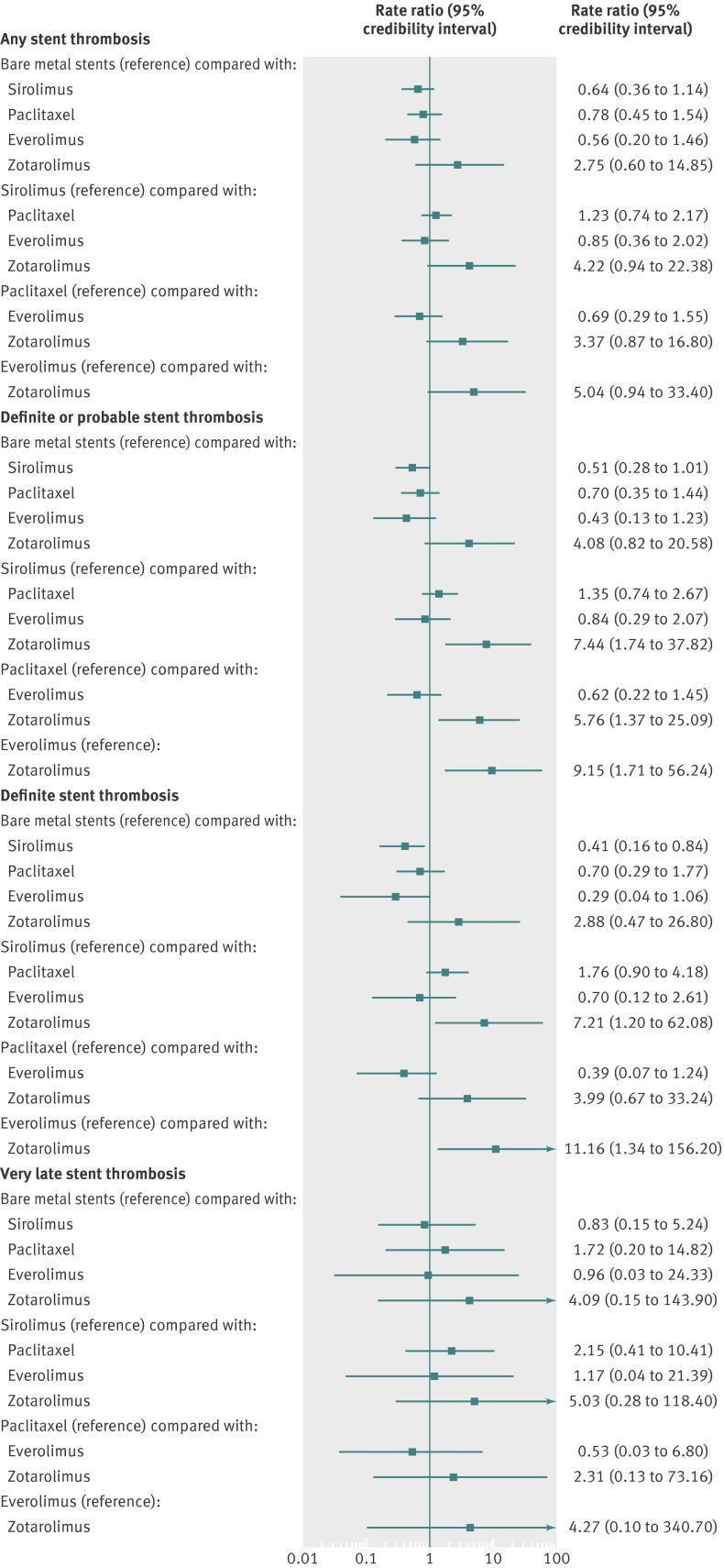

For the outcome of “any” stent thrombosis, there was no significant increase with any of the drug eluting stents compared with bare metal stents (fig 5). Among types of drug eluting stent, there was no increased risk with any one type compared with another, though most comparisons did not favour zotarolimus eluting stents. There was a 62% probability that everolimus eluting stents had the lowest rate of any stent thrombosis (table 3). The results were largely similar for the outcomes of definite or probable stent thrombosis and definite stent thrombosis, with a suggestion for better outcomes with drug eluting stents other than zotarolimus eluting stents (fig 5). For the outcome of very late stent thrombosis, there was no increased risk with any drug eluting stents compared with bare metal stents nor was there a difference between types of drug eluting stents (fig 5). For this outcome, probability analysis failed to identify one stent type that was the best (the probability of being best was 25% for bare metal stent, 27% for sirolimus eluting stents, and 36% for everolimus eluting stents).

Fig 5 Stent type and risk of any stent thrombosis, definite or probable stent thrombosis, definite stent thrombosis, and very late stent thrombosis with 95% credibility intervals

We performed a sensitivity analyses including the only two published trials of ZES-Resolute stents (TWENTE, RESOLUTE all comers trials). For these two trials, given the availability of target lesion/vessel failure endpoints in the diabetic cohort, we substituted this for the target vessel revascularisation outcome. ZES-Resolute was associated with similar rate ratio for target vessel revascularisation compared with other drug eluting stents, with significant benefit compared with bare metal stents (fig A8 in appendix 2). Compared with ZES-Resolute, however, the point estimate (rate ratio 1.54, 95% credibility interval 0.95 to 2.63) favoured everolimus eluting stents. Moreover, the probability analysis showed that there was still an 80% probability that everolimus eluting stents were associated with the lowest rates of target vessel revascularisation compared with all other stents, including the ZES-Resolute. Given the limited data, this analysis should be viewed as highly exploratory.

For all of the above analyses, sensitivity analyses in trials in which patients had used clopidogrel for more than six months (figs A3-A7 in appendix 2), trials at low risk of bias (table B in appendix 1), and trials after exclusion of acute coronary syndrome trials (table C in appendix 1) and the direct comparison meta-analysis (table D in appendix 1) yielded largely consistent results.

The heterogeneity between trials for the various network models showed low to moderate heterogeneity for most of the analyses (table E in appendix 1). In addition, evaluation of the goodness of fit for the various models showed adequate fit for the various analyses (tables F-H in appendix 1; figs B1-B7 in appendix 2).

Discussion

In patients with diabetes all drug eluting stents are highly efficacious at reducing the risk of target vessel revascularisation without increases in any adverse safety outcomes, including very late stent thrombosis, when compared with bare metal stents. There were significant differences among types of drug eluting stent for efficacy and safety, such that everolimus eluting stents were the most efficacious and safe.

Diabetes and outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention

Coronary artery disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes.21 Compared with patients without diabetes, those with diabetes have had worse outcomes with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty,1 22 bare metal stents,2 23 and drug eluting stents.3 4 They have smaller calibre vessels, diffuse disease that often progresses rapidly, a greater burden of atherosclerotic disease,21 24 and exaggerated neointimal hyperplasia, all of which increase the likelihood of the need for repeat revascularisation.25 26 27 In addition, glycosylation of vascular collagen and elastin is thought to result in more diffuse pattern of restenosis.28 Though use of drug eluting stents has considerably reduced the risk of restenosis, this still remains a major limitation in patients with diabetes. Stents differ in the amount of neointimal hyperplasia (as measured by late lumen loss), with bare metal stents having the highest followed by zotarolimus eluting stents, paclitaxel eluting stents, sirolimus eluting stents/everolimus eluting stents (in order of decreasing late lumen loss), probably accounting for differences in relative efficacy and safety. In the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) trial of patients with stable ischaemic heart disease, a strategy of revascularisation with optimal medical treatment did not reduce the risk of death or myocardial infarction compared with optimal medical treatment alone.29 In BARI 2D only 30% of patients received a drug eluting stent. In our analysis, the point estimate for sirolimus eluting stents (rate ratio 0.71, 95% credibility interval 0.49 to 1.05) and everolimus eluting stents (0.52, 0.21 to 1.09) favoured these stents compared with bare metal stents for myocardial infarction. In addition, there was an 80% probability that everolimus eluting stents had the lowest rates of myocardial infarction of all stents including bare metal stents (probability of only 0.5% of having the lowest rate). We therefore do not know if the results of trials of revascularisation versus medical treatment would have changed with the use of newer generation stents.

Stent choice in diabetes

There have been inconsistent results of clinical outcomes among various drug eluting stents as well as when drug eluting stents are compared with bare metal stents in patients with diabetes.

Drug eluting stents versus bare metal stents

A pooled patient level meta-analysis of four trials comparing sirolimus eluting stents with bare metal stents suggested an increased risk of mortality with sirolimus eluting stents in the subgroup with diabetes.30 This analysis, however, included only 428 patients with diabetes. Our analysis with a 25-fold greater sample size failed to show any important safety concerns with any of the currently used drug eluting stents compared with bare metal stents. These observations are consistent with those of Stettler and colleagues16 and extend the finding to newer generation drug eluting stents.

Sirolimus eluting stents versus paclitaxel eluting stents

Earlier studies and analyses comparing sirolimus eluting stents and paclitaxel eluting stents in patients with diabetes had discordant conclusions, with subgroup analyses/pooled analyses from patients with diabetes enrolled in randomised controlled trials and several registry studies5 6 7 suggesting that a paclitaxel eluting stent (Taxol) might perform similarly to a sirolimus eluting stent (limus), with other studies showing superiority of sirolimus eluting stents.8 While the limitations of earlier studies were mainly the small sample size of the cohort with diabetes, dedicated randomised controlled trials in patients with diabetes have shown superiority of sirolimus eluting stents compared with paclitaxel eluting stents.9 10 11 In the Drug-Eluting Stent in patients with DIABETES mellitus (DES-DIABETES) trial, sirolimus eluting stents were associated with reduction in restenosis and major adverse cardiac outcomes during up to two years of follow-up.9 10 At four years, however, there was no difference in the outcomes between the two stents.10 The collaborative network meta-analysis by Stettler and colleagues, which included 3852 patients with diabetes, showed no difference between sirolimus eluting stents and paclitaxel eluting stents for the efficacy (hazard ratio 0.76 (95% confidence interval 0.53 to 1.05) for target lesion revascularisation) and safety outcomes.16 The point estimate for target lesion revascularisation, however, favoured sirolimus eluting stents. Our analysis, with close to three times the sample size of the previous analysis, showed similar trend for the outcome of target vessel revascularisation (0.81, 95% credibility interval 0.65 to 1.01) but superiority of sirolimus eluting stents over paclitaxel eluting stents (0.73, 0.55 to 0.95) for the outcome of target lesion revascularisation and are consistent with head-to-head trials of sirolimus eluting stents versus paclitaxel eluting stents, in which sirolimus eluting stents have consistently been associated with lower late lumen loss.11 31 32 In addition, in a randomised trial of sirolimus eluting stents versus paclitaxel eluting stents in the same patient with multiple lesions, sirolimus eluting stents fared significantly better with lower late lumen loss.33

Everolimus eluting stents versus paclitaxel eluting stents

A pooled analysis from the SPIRIT and COMPARE trials showed an interaction between diabetes mellitus and stent type on clinical outcomes.20 In patients without diabetes mellitus, everolimus eluting stents resulted in two year reductions in death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, and target lesion revascularisation, whereas no significant differences in safety or efficacy outcomes were found in patients with diabetes.20 This study had only 1869 patients with diabetes. The point estimates favoured everolimus eluting stents, though the confidence intervals were wide (odds ratio 0.87 (95% confidence interval 0.55 to 1.40) for myocardial infarction, 0.90 (0.59 to 1.37) for target lesion revascularisation, and 0.80 (0.39 to 1.67) for stent thrombosis). Our analysis, with larger sample size, showed a significant benefit of everolimus eluting stents over paclitaxel eluting stents for target vessel revascularisation and target lesion revascularisation (rate ratio 0.68 (95% credibility interval 0.44 to 0.95) and 0.60 (0.33 to 0.93), respectively). In addition, probability analyses showed that there was an 87%, 81%, and 62% probability that everolimus eluting stents had the lowest rates of target vessel revascularisation, myocardial infarction, and any stent thrombosis, respectively, but these probability rates were low for paclitaxel eluting stents (probability of 0.3%, 2.1%, 4.5%, respectively).

Zotarolimus eluting stents

In our analyses, zotarolimus eluting stents were associated with a higher rate of repeat revascularisation (compared with sirolimus eluting stents or everolimus eluting stents) and higher rate of myocardial infarction (compared with sirolimus eluting stents/paclitaxel eluting stents or everolimus eluting stents). The credibility interval around the estimates for zotarolimus eluting stent were wide, suggesting less precision and confidence in the estimates, and is probably because of limited published data on the use of zotarolimus eluting stents in patients with diabetes. In the diabetes subgroup analysis from the Danish Organization for Clinical Trials with Clinical Outcome (SORT OUT) III trial, zotarolimus eluting stents were associated with a fourfold increase in the risk of a major cardiac event (18.3% v 4.8%; P<0.001), an eightfold increase in myocardial infarction (4.7% v 0.6%; P=0.049), an fivefold increase in target vessel revascularisation (14.2% v 3.0%; P=0.001), and an 11-fold increase in target lesion revascularisation (12.4% v 1.2%; P=0.002), with trends for worse definite stent thrombosis (1.8% v 0.0%) compared with sirolimus eluting stents.34 In patients with diabetes, given their extensive atherosclerosis and smaller reference vessel diameters, an increased late loss (such as that observed with zotarolimus eluting stents) might lead to an increase in restenosis, with a lesser margin for “tolerated late loss”. In our sensitivity analysis, inclusion of the only two published randomised trials on ZES-Resolute showed that ZES-Resolute was similar to everolimus eluting stents for target vessel revascularisation, although the point estimate favoured everolimus eluting stents (rate ratio 0.65, 95% credibility interval 0.38 to 1.05). In addition, there was still an 80% probability that everolimus eluting stents was associated with the lowest rates of target vessel revascularisation compared with all other stents, including the ZES-Resolute. This analysis, however, is highly exploratory and more data are needed with ZES-Resolute before any robust conclusions can be made on the relative efficacy. Of note, both in the Resolute All Comers trial35 (odds ratio 1.45 (95% confidence interval 0.82, 2.58) for target lesion failure with ZES-Resolute v everolimus eluting stents) and the TWENTE trial (rate ratio 1.81 (0.91 to 3.60) for target vessel failure with ZES-Resolute v everolimus eluting stents, 13.9% v 7.7%, P=0.08), the point estimates favoured everolimus eluting stents over ZES-Resolute in the subgroup with diabetes.

Finally, in the present analysis, everolimus eluting stents were the most efficacious and the safest stents. These results are consistent with the results in the subgroups of patients without diabetes.36 37 38 39 Of note, in all the analyses the credibility intervals for the comparisons of everolimus eluting stents and sirolimus eluting stents crossed unity. Probability analyses, however, showed that there was an 87%, 81%, and 62% probability that everolimus eluting stents were associated with the lowest rates of target vessel revascularisation, myocardial infarction, and any stent thrombosis, respectively, but these were low for sirolimus eluting stents (probability of 12%, 17%, and 30%, respectively).

Limitations and strengths

The limitations of previous analyses have mainly been the limited sample sizes and pooling of one type of drug eluting stent and comparison with all other types. The strengths of our analyses are that we have data from more than 22 000 patient years of follow-up. In addition, we compared each type of drug eluting stent with each other, thus avoiding comparison of one type against a heterogeneous mixture of other types. In addition, our search strategy was fairly extensive with use of data from multiple sources, thereby reducing outcome reporting bias.

As in other meta-analyses, though we undertook detailed sensitivity analyses on many variables, given the heterogeneity of the study protocols, clinically relevant differences could have been missed and are best assessed in a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Given clinical heterogeneity, though we used a conservative approach using a random effects model (despite low statistical heterogeneity) and despite detailed sensitivity analyses on many variables, confounding by indication cannot be ruled out. Not all of the trials reported each of the outcomes assessed. In addition, we included the pooled SPIRIT and COMPARE trials data rather than individual trials as this pooled analyses provided more comprehensive and longer term follow-up and reported data exclusively on the diabetic cohort compared with the individual trials alone.20 The results of the sensitivity analyses are best described as secondary and hypothesis generating only. The differences seen within types of drug eluting stents are applicable only to the specific stents evaluated in this study. Nonetheless, this large study offers important insights into their relative safety and efficacy.

Conclusions

Among patients with diabetes, currently used drug eluting stents are highly efficacious at reducing the risk of target vessel revascularisation/target lesion revascularisation without compromising safety outcomes, including very late stent thrombosis, compared with bare metal stents. We found considerable differences in the relative efficacy and safety of currently used drug eluting stents, such that everolimus eluting stents were the safest and most efficacious. There were limited published data on zotarolimus eluting Resolute stent in the diabetes subgroup, and more data are need before any inference can be made on this stent.

What is already known on this topic

Presence of diabetes is associated with worse outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention

The long term efficacy and safety of various drug eluting stents compared against each other and compared with bare metal stents in patients with diabetes is controversial, with various reports of superiority of paclitaxel eluting stents, sirolimus eluting stents, or everolimus eluting stents

What this study adds

Among patients with diabetes treated with coronary stents, compared with bare metal stents all currently available drug eluting stents were efficacious without compromising safety

When compared with bare metal stents, all of the currently used drug eluting stents were associated with significant reduction in target vessel revascularisation (37% to 69%), though the efficacy varied with the type of stent

Everolimus eluting stents were the most efficacious and safe stent in patients with diabetes

Contributors: SB had the original concept and designed the study; acquired, analysed, and interpreted the data; and drafted the paper. SK, MF, and NA also acquired data. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SB was responsible for statistical analysis, supervised the study, and is guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that SB is on the advisory boards of Boehringer Ingelheim and Daiichi Sankyo and DEC was prinicpal investigator on the Medtronic EDUCATE trial.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e5170

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1: Supplementary tables A-H

Appendix 2: Supplementary figures A1-A8 and B1-B7

References

- 1.Kip KE, Faxon DP, Detre KM, Yeh W, Kelsey SF, Currier JW. Coronary angioplasty in diabetic patients. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty Registry. Circulation 1996;94:1818-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abizaid A, Kornowski R, Mintz GS, Hong MK, Abizaid AS, Mehran R, et al. The influence of diabetes mellitus on acute and late clinical outcomes following coronary stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheen AJ, Warzee F, Legrand VM. Drug-eluting stents: meta-analysis in diabetic patients. Eur Heart J 2004;25:2167-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheen AJ, Warzee F. Diabetes is still a risk factor for restenosis after drug-eluting stent in coronary arteries. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1840-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daemen J, Garcia-Garcia HM, Kukreja N, Imani F, de Jaegere PP, Sianos G, et al. The long-term value of sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents over bare metal stents in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur Heart J 2007;28:26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ong AT, Aoki J, van Mieghem CA, Rodriguez Granillo GA, Valgimigli M, Tsuchida K, et al. Comparison of short- (one month) and long- (twelve months) term outcomes of sirolimus- versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in 293 consecutive patients with diabetes mellitus (from the RESEARCH and T-SEARCH registries). Am J Cardiol 2005;96:358-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stankovic G, Cosgrave J, Chieffo A, Iakovou I, Sangiorgi G, Montorfano M, et al. Impact of sirolimus-eluting and Paclitaxel-eluting stents on outcome in patients with diabetes mellitus and stenting in more than one coronary artery. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billinger M, Beutler J, Taghetchian KR, Remondino A, Wenaweser P, Cook S, et al. Two-year clinical outcome after implantation of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in diabetic patients. Eur Heart J 2008;29:718-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SW, Park SW, Kim YH, Yun SC, Park DW, Lee CW, et al. A randomized comparison of sirolimus- versus Paclitaxel-eluting stent implantation in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:727-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SW, Park SW, Kim YH, Yun SC, Park DW, Lee CW, et al. A randomized comparison of sirolimus- versus paclitaxel-eluting stent implantation in patients with diabetes mellitus: 4-year clinical outcomes of DES-DIABETES (drug-eluting stent in patients with DIABETES mellitus) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dibra A, Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Pache J, Schuhlen H, von Beckerath N, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting or sirolimus-eluting stents to prevent restenosis in diabetic patients. N Engl J Med 2005;353:663-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.0.0. Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

- 13.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation 2007;115:2344-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JP. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ 2005;331:897-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiegelhalter D, Abrams K, Myles J. Bayesian approaches to clinical trials and health-care evaluation: statistics in practice.John Wiley, 2004.

- 16.Stettler C, Allemann S, Wandel S, Kastrati A, Morice MC, Schomig A, et al. Drug eluting and bare metal stents in people with and without diabetes: collaborative network meta-analysis. BMJ 2008;337:a1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet 1999;354:1896-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradburn MJ, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Sbe24: metan—an alternative meta-analysis command. Stata Technical Bulletin Reprints 1998;8:86-100. [Google Scholar]

- 19.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone GW, Kedhi E, Kereiakes DJ, Parise H, Fahy M, Serruys PW, et al. Differential clinical responses to everolimus-eluting and Paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2011;124:893-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goraya TY, Leibson CL, Palumbo PJ, Weston SA, Killian JM, Pfeifer EA, et al. Coronary atherosclerosis in diabetes mellitus: a population-based autopsy study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:946-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Comparison of coronary bypass surgery with angioplasty in patients with multivessel disease. The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) investigators. N Engl J Med 1996;335:217-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson SR, Vakili BA, Sherman W, Sanborn TA, Brown DL. Effect of diabetes on long-term mortality following contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention: analysis of 4,284 cases. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1137-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurst RT, Lee RW. Increased incidence of coronary atherosclerosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus: mechanisms and management. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:824-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luscher TF, Creager MA, Beckman JA, Cosentino F. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: part II. Circulation 2003;108:1655-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry C, Tardif JC, Bourassa MG. Coronary heart disease in patients with diabetes: part II: recent advances in coronary revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:643-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syeda B, Wexberg P, Gyongyosi M, Denk S, Beran G, Sperker W, et al. Mechanism of lumen gain during coronary stent deployment in diabetic patients compared with non-diabetic patients. Coron Artery Dis 2002;13:263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christensen T, Neubauer B. Increased arterial wall stiffness and thickness in medium-sized arteries in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Acta Radiol 1988;29:299-302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frye RL, August P, Brooks MM, Hardison RM, Kelsey SF, MacGregor JM, et al. A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2503-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spaulding C, Daemen J, Boersma E, Cutlip DE, Serruys PW. A pooled analysis of data comparing sirolimus-eluting stents with bare-metal stents. N Engl J Med 2007;356:989-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Windecker S, Remondino A, Eberli FR, Juni P, Raber L, Wenaweser P, et al. Sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 2005;353:653-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kastrati A, Mehilli J, von Beckerath N, Dibra A, Hausleiter J, Pache J, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stent or paclitaxel-eluting stent vs balloon angioplasty for prevention of recurrences in patients with coronary in-stent restenosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;293:165-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomai F, Reimers B, De Luca L, Galassi AR, Gaspardone A, Ghini AS, et al. Head-to-head comparison of sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stent in the same diabetic patient with multiple coronary artery lesions: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Diabetes Care 2008;31:15-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeng M, Jensen LO, Tilsted HH, Kaltoft A, Kelbaek H, Abildgaard U, et al. Outcome of sirolimus-eluting versus zotarolimus-eluting coronary stent implantation in patients with and without diabetes mellitus (a SORT OUT III substudy). Am J Cardiol 2011;108:1232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serruys PW, Silber S, Garg S, van Geuns RJ, Richardt G, Buszman PE, et al. Comparison of zotarolimus-eluting and everolimus-eluting coronary stents. N Engl J Med 2010;363:136-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garg S, Serruys P, Onuma Y, Dorange C, Veldhof S, Miquel-Hebert K, et al. 3-year clinical follow-up of the XIENCE V everolimus-eluting coronary stent system in the treatment of patients with de novo coronary artery lesions: the SPIRIT II trial (clinical evaluation of the Xience V everolimus eluting coronary stent system in the treatment of patients with de novo native coronary artery lesions). JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2009;2:1190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Serruys PW, Ruygrok P, Neuzner J, Piek JJ, Seth A, Schofer JJ, et al. A randomised comparison of an everolimus-eluting coronary stent with a paclitaxel-eluting coronary stent: the SPIRIT II trial. Euro Intervention 2006;2:286-94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stone GW, Midei M, Newman W, Sanz M, Hermiller JB, Williams J, et al. Randomized comparison of everolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents: two-year clinical follow-up from the Clinical Evaluation of the Xience V Everolimus Eluting Coronary Stent System in the Treatment of Patients with de novo Native Coronary Artery Lesions (SPIRIT) III trial. Circulation 2009;119:680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stone GW, Rizvi A, Sudhir K, Newman W, Applegate RJ, Cannon LA, et al. Randomized comparison of everolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents. 2-year follow-up from the SPIRIT (Clinical Evaluation of the XIENCE V Everolimus Eluting Coronary Stent System) IV trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaiser C, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Buser PT, Bonetti PO, Osswald S, Linka A, et al. Incremental cost-effectiveness of drug-eluting stents compared with a third-generation bare-metal stent in a real-world setting: randomised Basel Stent Kosten Effektivitats Trial (BASKET). Lancet 2005;366:921-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Lezo JS, Medina A, Pan M, Romero M, Delgado A, Segura J, et al. Drug-eluting stents for complex lesions: latest angiographic data from the randomized rapamycin versus paclitaxel CORPAL study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:75A. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan C, Zambahari R, Kaul U, Lau CP, Whitworth H, Cohen S, et al. A randomized comparison of sirolimus-eluting versus bare metal stents in the treatment of diabetic patients with native coronary artery lesions: the DECODE study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2008;72:591-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maresta A, Varani E, Balducelli M, Varbella F, Lettieri C, Uguccioni L, et al. Comparison of effectiveness and safety of sirolimus-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in patients with diabetes mellitus (from the Italian Multicenter Randomized DESSERT Study). Am J Cardiol 2008;101:1560-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sabate M, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Angiolillo DJ, Gomez-Hospital JA, Alfonso F, Hernandez-Antolin R, et al. Randomized comparison of sirolimus-eluting stent versus standard stent for percutaneous coronary revascularization in diabetic patients: the diabetes and sirolimus-eluting stent (DIABETES) trial. Circulation 2005;112:2175-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jimenez-Quevedo P, Hernando L, Gomez-Hospital JA, Iniguez A, Sanroman A, Alfonso F, et al. Five year follow up of DIABETES trial: the final results. Eur Heart J 2011;32:654-55.21113065 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maeng M, Jensen LO, Galloe AM, Thayssen P, Christiansen EH, Hansen KN, et al. Comparison of the sirolimus-eluting versus paclitaxel-eluting coronary stent in patients with diabetes mellitus: the diabetes and drug-eluting stent (DiabeDES) randomized angiography trial. Am J Cardiol 2009;103:345-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fajadet J, Wijns W, Laarman GJ, Kuck KH, Ormiston J, Munzel T, et al. Randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of the Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting phosphorylcholine-encapsulated stent for treatment of native coronary artery lesions: clinical and angiographic results of the ENDEAVOR II trial. Circulation 2006;114:798-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kandzari DE, Mauri L, Popma JJ, Turco MA, Gurbel PA, Fitzgerald PJ, et al. Late-term clinical outcomes with zotarolimus- and sirolimus-eluting stents. 5-year follow-up of the ENDEAVOR III (a randomized controlled trial of the Medtronic Endeavor drug [ABT-578] eluting coronary stent system versus the Cypher sirolimus-eluting coronary stent system in de novo native coronary artery lesions). JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:543-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirtane AJ, Patel R, O’Shaughnessy C, Overlie P, McLaurin B, Solomon S, et al. Clinical and angiographic outcomes in diabetics from the ENDEAVOR IV trial: randomized comparison of zotarolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents in patients with coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2009;2:967-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schofer J, Schluter M, Gershlick AH, Wijns W, Garcia E, Schampaert E, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stents for treatment of patients with long atherosclerotic lesions in small coronary arteries: double-blind, randomised controlled trial (E-SIRIUS). Lancet 2003;362:1093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim WJ, Lee SW, Park SW, Kim YH, Yun SC, Lee JY, et al. Randomized comparison of everolimus-eluting stent versus sirolimus-eluting stent implantation for de novo coronary artery disease in patients with diabetes mellitus (ESSENCE-DIABETES): results from the ESSENCE-DIABETES trial. Circulation 2011;124:886-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hong SJ, Kim MH, Cha KS, Park HS, Chae SC, Hur SH, et al. Comparison of three-year clinical outcomes between sirolimus-versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in diabetic patients: prospective randomized multicenter trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2010;76:924-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Witzenbichler B, Wohrle J, Guagliumi G, Peruga JZ, Brodie BR, Dudek D, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting stents compared with bare metal stents in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction: the Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mehilli J, Kastrati A, Byrne RA, Bruskina O, Iijima R, Schulz S, et al. Paclitaxel- versus sirolimus-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1760-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Byrne RA, Kastrati A, Tiroch K, Schulz S, Pache J, Pinieck S, et al. 2-year clinical and angiographic outcomes from a randomized trial of polymer-free dual drug-eluting stents versus polymer-based Cypher and Endeavor [corrected] drug-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2536-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Byrne RA, Mehilli J, Iijima R, Schulz S, Pache J, Seyfarth M, et al. A polymer-free dual drug-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized trial vs polymer-based drug-eluting stents. Eur Heart J 2009;30:923-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim MH, Hong SJ, Cha KS, Park HS, Chae SC, Hur SH, et al. Effect of paclitaxel-eluting versus sirolimus-eluting stents on coronary restenosis in Korean diabetic patients. J Interv Cardiol 2008;21:225-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim YH, Park SW, Lee SW, Park DW, Yun SC, Lee CW, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stent versus paclitaxel-eluting stent for patients with long coronary artery disease. Circulation 2006;114:2148-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Briguori C, Airoldi F, Visconti G, Focaccio A, Caiazzo G, Golia B, et al. Novel approaches for preventing or limiting events in diabetic patients (Naples-diabetes) trial: a randomized comparison of 3 drug-eluting stents in diabetic patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pache J, Dibra A, Mehilli J, Dirschinger J, Schomig A, Kastrati A. Drug-eluting stents compared with thin-strut bare stents for the reduction of restenosis: a prospective, randomized trial. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Laarman GJ, Suttorp MJ, Dirksen MT, van Heerebeek L, Kiemeneij F, Slagboom T, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting versus uncoated stents in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1105-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morice MC, Colombo A, Meier B, Serruys P, Tamburino C, Guagliumi G, et al. Sirolimus- vs paclitaxel-eluting stents in de novo coronary artery lesions: the REALITY trial: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;295:895-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.European Society of Congress. Randomized Evaluation of Sirolimus-eluting Versus Everolimus-eluting Stent Trial (RESET). European Society of Congress, 2011.

- 64.Kelbaek H, Thuesen L, Helqvist S, Klovgaard L, Jorgensen E, Aljabbari S, et al. The Stenting Coronary Arteries in Non-stress/benestent Disease (SCANDSTENT) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:449-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baumgart D, Klauss V, Baer F, Hartmann F, Drexler H, Motz W, et al. One-year results of the SCORPIUS study: a German multicenter investigation on the effectiveness of sirolimus-eluting stents in diabetic patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:1627-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De Waha A, Dibra A, Kufner S, Baumgart D, Sabate M, Maresta A, et al. Long-term outcome after sirolimus-eluting stents versus bare metal stents in patients with diabetes mellitus: a patient-level meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin Res Cardiol 2011;100:561-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Menichelli M, Parma A, Pucci E, Fiorilli R, De Felice F, Nazzaro M, et al. Randomized Trial of Sirolimus-Eluting Stent Versus Bare-Metal Stent in Acute Myocardial Infarction (SESAMI). J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1924-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ortolani P, Ardissino D, Cavallini C, Bramucci E, Indolfi C, Aquilina M, et al. Effect of sirolimus-eluting stent in diabetic patients with small coronary arteries (a SES-SMART substudy). Am J Cardiol 2005;96:1393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moussa I, Leon MB, Baim DS, O’Neill WW, Popma JJ, Buchbinder M, et al. Impact of sirolimus-eluting stents on outcome in diabetic patients: a SIRIUS (SIRolImUS-coated Bx velocity balloon-expandable stent in the treatment of patients with de novo coronary artery lesions) substudy. Circulation 2004;109:2273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Junkers A, Jensen LO, Thayssen P, Maeng M, Tilsted H-H, Kaltoft A, et al. Impact of diabetes on clinical outcomes after revascularization with everolimus- and sirolimus-eluting stents. A substudy of the SORT OUT IV Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:B25-TCT82. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goy JJ, Stauffer JC, Siegenthaler M, Benoit A, Seydoux C. A prospective randomized comparison between paclitaxel and sirolimus stents in the real world of interventional cardiology: the TAXi trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:308-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Colombo A, Drzewiecki J, Banning A, Grube E, Hauptmann K, Silber S, et al. Randomized study to assess the effectiveness of slow- and moderate-release polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting stents for coronary artery lesions. Circulation 2003;108:788-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hermiller JB, Raizner A, Cannon L, Gurbel PA, Kutcher MA, Wong SC, et al. Outcomes with the polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting TAXUS stent in patients with diabetes mellitus: the TAXUS-IV trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:1172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cannon L, Mann JT, Greenberg JD, Spriggs D, et al. Comparison of a polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting stent with a bare metal stent in patients with complex coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;294:1215-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dawkins KD, Grube E, Guagliumi G, Banning AP, Zmudka K, Colombo A, et al. Clinical efficacy of polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting stents in the treatment of complex, long coronary artery lesions from a multicenter, randomized trial: support for the use of drug-eluting stents in contemporary clinical practice. Circulation 2005;112:3306-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spaulding C, Henry P, Teiger E, Beatt K, Bramucci E, Carrie D, et al. Sirolimus-eluting versus uncoated stents in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1093-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Von Birgelen C, Basalus MW, Tandjung K, van Houwelingen KG, Stoel MG, Louwerenburg JH, et al. A randomized controlled trial in second-generation zotarolimus-eluting resolute stents versus everolimus-eluting Xience V stents in real-world patients: the TWENTE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1350-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Supplementary tables A-H

Appendix 2: Supplementary figures A1-A8 and B1-B7