Abstract

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) O157:H7 is a lethal human intestinal pathogen that causes hemorrhagic colitis and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. EHEC is transmitted by the fecal-oral route and has a lower infectious dose than most other enteric bacterial pathogens in that fewer than 100 CFU are able to cause disease. This low infectious dose has been attributed to the ability of EHEC to survive in the acidic environment of the human stomach. In silico analysis of the genome of EHEC O157:H7 strain EDL933 revealed a gene, patE, for a putative AraC-like regulatory protein within the prophage island, CP-933H. Transcriptional analysis in E. coli showed that the expression of patE is induced during stationary phase. Data from microarray assays demonstrated that PatE activates the transcription of genes encoding proteins of acid resistance pathways. In addition, PatE downregulated the expression of a number of genes encoding heat shock proteins and the type III secretion pathway of EDL933. Transcriptional analysis and electrophoretic mobility shift assays suggested that PatE also activates the transcription of the gene for the acid stress chaperone hdeA by binding to its promoter region. Finally, assays of acid tolerance showed that increasing the expression of PatE in EHEC greatly enhanced the ability of the bacteria to survive in different acidic environments. Together, these findings indicate that EHEC strain EDL933 carries a prophage-encoded regulatory system that contributes to acid resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) O157:H7 is the most prevalent serotype associated with life-threatening hemorrhagic colitis and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome in Europe and the United States (30, 38, 40). EHEC is a food- and waterborne pathogen, with several outbreaks attributed to processed foods, such as apple cider (6, 24), dry cured salami, and ground beef products (11, 19, 43). Foods contaminated with bovine feces are a common source of infection, since the bovine intestinal tract is the major reservoir of O157:H7 isolates (19, 44, 46, 58).

Although the most important virulence determinant of EHEC responsible for severe disease is Shiga toxin, other virulence factors also contribute to the infection process. Adherence of EHEC to intestinal epithelial cells, the vanguard of intestinal colonization, results in the formation of attaching-and-effacing (AE) lesions, which cause the destruction of microvilli and the rearrangement of cytoskeletal proteins (16, 56). The genes required for the formation of AE lesions are encoded by the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island (PAI), one of the many O islands scattered around the EHEC O157:H7 chromosome (41). These O islands contribute ∼1.3 Mb of DNA, which is absent from the common chromosomal backbone of the nonpathogenic E. coli K-12 strain, and are associated with prophage or prophage-like elements (21, 41, 65). Many virulence factors are encoded on these prophage islands, including Shiga toxins and a type III protein secretion system (T3SS) and its associated secreted effector proteins.

The ability of EHEC to withstand the acidic environment of the human stomach is another essential virulence factor, because it allows the bacteria to access the large intestine in sufficient numbers to colonize and cause disease (15, 64). Once EHEC has reached its preferred niche of colonization, the bacteria encounter a more permissive, less acidic environment, although they still are exposed to volatile organic acids produced by the local microbiota during anaerobic fermentation (10). Thus, the ability of EHEC to mount an appropriate acid stress response is an essential virulence trait of this pathogen.

Several distinct acid resistance (AR) pathways have been identified in E. coli (64) and are present in EHEC (15). Oxidative or amino acid-independent acid resistance pathway 1 (AR1) is induced in stationary phase (18, 51) and is dependent on the alternative sigma factor σs and the cyclic AMP (cAMP) response protein (CRP) (4, 18). The mechanism of protection by AR1 is unclear. AR2, AR3, and AR4 are amino acid decarboxylase-based pathways, which require the presence of glutamate, arginine, or lysine, respectively, to function (31, 64). AR2 comprises two decarboxylase isozymes, GadA and GadB, and an antiporter, GadC. GadA and GadB transfer the intracellular protons to glutamic acid and convert it into γ-amino butyric acid. The latter is then secreted by GadC into the extracellular medium in exchange for another glutamate molecule (3). AR2 is the most efficient acid stress response system in E. coli and is able to protect bacterial cells against acidity as low as pH 2 (64).

Transcriptional control of the genes required for virulence is essential for bacterial survival and involves a complex interplay between various regulatory proteins. An important group of regulators consists of members of the AraC superfamily (17, 61, 62). In general, AraC-like proteins are composed of 200 to 300 amino acids (aa), comprising two distinct domains: an N-terminal stretch, which can be highly variable, and a C-terminal region harboring the characteristic double helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif for DNA binding (17). Since members of this family exhibit an overall low level of sequence conservation, it is not surprising that their mechanisms of action can be quite distinct. For example, they can induce and/or repress entirely unrelated genes/regulons, respond to different environmental stimuli, or modify gene expression in the absence of any signaling molecule (1, 35, 59, 60).

Although EHEC O157:H7 strain EDL933 encodes a number of housekeeping AraC-like regulators on its chromosomal backbone, prior to this work, no AraC-like protein had been identified within its various prophage islands. We therefore screened the EDL933 genome for unique AraC-like proteins. By investigating global transcription profiles, we identified the transcriptional regulator Z0321 (designated PatE below) and showed that this protein specifically activates the transcription of genes responsible for the complex response of EHEC to acid stress. We also examined the specific interaction of PatE with its promoter targets and assessed the effects of PatE on different acid resistance pathways of EHEC EDL933.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, primers, and media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Unless stated otherwise, bacteria were grown at 37°C in Luria Bertani broth (LB) or on Luria agar (LA) plates supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 10 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; trimethoprim, 40 μg/ml. The primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| EDL933 | EHEC serotype O157:H7 | 39, 41 |

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | New England Biolabs |

| EDL933 (Δstx1-2) | O157:H7 Δstx1 Δstx2 | This study |

| EDL933 (Δ1, Δstx1-2) | O157:H7 Δstx1 Δstx2 ΔpatE | This study |

| EDL933 (Δ2, Δstx1-2) | O157:H7 Δstx1 Δstx2 ΔpatE ΔpsrA | This study |

| EDL933 (Δ3, Δstx1-2) | O157:H7 Δstx1 Δstx2 ΔpatE ΔpsrA ΔprsB | This study |

| TOP10 | F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 nupG recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galE15 galK16 rpsL(Strr) endA1 λ− | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy | High-copy-number vector; Apr | Promega |

| pCR2.1-TOPO | High-copy-number vector; Apr Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pACYC184 | Medium-copy-number vector; Cmr Tcr | 9 |

| pKD46 | Low-copy-number vector; PBAD-λred; Apr | 12 |

| pFT-A | Low-copy-number vector; flp; Apr | 42 |

| pMU2385 | Single-copy-number transcriptional-fusion vector; Tpr | 63 |

| pMU2386 | Single-copy-number translational-fusion vector; Tpr | 2 |

| pJP1433 | Synthetic RBS with ATG start codon fused in phase with codon 8 of lacZ in pMU2385; Tpr | This study |

| pMAL-c2x | Expression vector for N-terminal MBP fusion proteins | New England Biolabs |

| pJB2 | pCR2.1-TOPO + patEprom + 6aa | This study |

| pJB3 | pCR2.1-TOPO + psrAprom + 6aa | This study |

| pJB4 | pCR2.1-TOPO + psrBprom + 6aa | This study |

| pJB5 | pMU2386 + patE | This study |

| pJB6 | pMU2386 + psrA | This study |

| pJB7 | pMU2386 + psrB | This study |

| pJB8 | pCR2.1-TOPO + patE | This study |

| pJB11 | pACYC184 + patE | This study |

| pJB17 | pGEM-T Easy + patE | This study |

| pJB21 | pMAL-c2x + patE | This study |

| pJB23 | pGEM-T Easy + hdeAprom | This study |

| pJB29 | pJP1433 + hdeAprom1 | This study |

| pJB37 | pGEM-T Easy + hdeAcontrol | This study |

| pJB50 | pJP1433 + hdeAprom4 | This study |

| pJB51 | pJP1433 + hdeAprom3 | This study |

| pJB52 | pJP1433 + hdeAprom2 | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance; Tpr, trimethoprim resistance. RBS, ribosome binding site.

Generation of E. coli EDL933 nonpolar mutant strains.

The λ Red recombinase system was utilized to construct nonpolar deletion mutants of EHEC EDL933. First, a Shiga toxin-negative mutant was generated as follows. Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes), which generates blunt-ended fragments, and primer pairs Stx2.F/Stx2CK.R and Stx2.R/Stx2CK.F were used to amplify the DNA sequences flanking the region to be deleted from the chromosome of EHEC EDL933, and primers pKD4.F and pKD4.R were used to amplify the kanamycin resistance (Kmr) cassette, bordered by FLP recombination target (FRT) sites, from plasmid pKD4. The products of these three PCRs (100 ng each) served as templates in overlapping extension PCR (8), using Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and primers Stx2.F and Stx2.R, to generate a DNA fragment carrying a Kmr cassette flanked by ∼500-bp regions up- and downstream of EHEC EDL933 stx2. This DNA fragment was cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega); the recombinant plasmid was introduced into E. coli K-12 TOP10 cells (Invitrogen); and the insert was then confirmed by sequencing. The pGEM-T Easy construct was used as a template in a PCR with primers Stx2.F and Stx2.R to amplify the linear allelic replacement DNA fragment, which was introduced by electroporation into EHEC EDL933 harboring plasmid pKD46. The Δstx2 mutation was confirmed by PCR using primer pairs in which one primer flanked the targeted region and the other primed within the Kmr cassette (Stx2seq.F/pKD4seq.R and Stx2seq.R/pKD4seq.F). The PCR products were sequenced using primers pKD4seq.R and pKD4seq.F. The Kmr cassette was excised from the EHEC EDL933 Δstx2 Kmr strain using Flp recombinase encoded on plasmid pFT-A, generating a marker-free deletion mutant, EDL933 Δstx2. The same general protocol was employed to delete the stx1 gene from EDL933 Δstx2, using the stx1-specific primers Stx1.F, Stx1CK.R, Stx1.R, and Stx1CK.F. The Δstx1 mutation was confirmed by PCR using primer pairs Stx1seq.F/pKD4seq.R and Stx1seq.R/pKD4seq.F, and the PCR products were sequenced using primers pKD4seq.R and pKD4seq.F. The Kmr cassette was excised using Flp recombinase, generating EDL933 Δstx2 Δstx1 [referred to below as EDL933(Δstx1-2)], which was used as the parent strain for further mutagenesis.

E. coli EHEC EDL933(Δstx1-2) Δz0321 Δz1789 Δz2104 [EDL933 (Δ3 Δstx1-2)] was constructed as described above, by sequentially deleting the putative genes z0321, z1789, and z2104 (in the order listed) using primer pairs Z0321.F/Z0321CK.R and Z0321CK.F/Z0321.R for z0321, Z1789.F/Z1789CK.R and Z1789CK.F/Z1789.R for z1789, and Z2104-FW/Z1789CK.R and Z1789CK.F/Z2104-RV for z2104 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). All chromosomal mutations were confirmed by PCR and sequencing, using gene-specific primers Z0321seq.F, Z0321seq.R, Z1789seq.F, Z1789seq.R, Z2104seq.F, and Z2104seq.R.

Construction of a trans-complementing plasmid, pJB11.

For complementation, a 1,426-bp fragment containing z0321 was amplified from E. coli EHEC EDL933 genomic DNA by using primer pair Z0321Fw-HindIII/Z0321Rv2-BamHI and was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) to yield pJB8, which was then checked by sequencing. The fragment was excised by HindIII/BamHI digestion and was ligated into HindIII/BamHI-digested pACYC184 to generate pJB11.

Construction of lacZ fusion plasmids.

Fragments consisting of a ∼500-bp upstream region and the first six triplets of the coding sequences of z0321, z1789, and z2104 were amplified from EDL933 genomic DNA by using primer pairs Z0321Fw-HindIII/Z0321Rv-BamHI, Z1789Fw-HindIII/Z1789Rv-BamHI, and Z2104Fw-HindIII/Z2104Rv-BamHI and were cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to yield pJB2, pJB3, and pJB4, respectively. Fragments were excised from vectors pJB2, pJB3, and pJB4 by HindIII/BamHI digestion and were inserted into the single-copy-number translational-fusion vector pMU2386 to generate plasmids pJB5, pJB6, and pJB7, respectively. Expression of β-galactosidase from these plasmids is dependent on transcription and translation from the EDL933-derived DNA inserts.

Four hdeA-lacZ transcriptional fusions were constructed by PCR amplification of DNA fragments that contain the regulatory region of hdeA. Each PCR fragment was cloned into pGEM-T Easy and was sequenced. The fragments were then excised from the pGEM-T Easy derivatives by PstI/BglII digestion and were cloned into the same sites of the single-copy-number transcriptional-fusion vector pJP1433 to create hdeA-lacZ fusions. The forward primers hdeA-PstI-fw, hdeA-lacZ1-fw, hdeA-lacZ2-fw, and hdeA-lacZ3-fw were used with reverse primer hdeA-BglII-rv to generate the hdeA-lacZ1 (pJB29), hdeA-lacZ2 (pJB52), hdeA-lacZ3 (pJB51), and hdeA-lacZ4 (pJB50) fusions, respectively.

β-Galactosidase assay.

Bacteria were grown to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼0.6) or for 22 h to late-stationary phase (OD600, ∼2). β-Galactosidase activity was assayed as described by Miller (37), and the specific activity was expressed in Miller units (MU). The data shown in the figures are the results of at least three independent assays, with a standard deviation of <15%.

Antisense E. coli EDL933 microarray.

An antisense oligonucleotide microarray was designed by using the eArray platform (Agilent Technologies). The arrays contained open reading frames (ORFs) representing all gene predictions as published by Perna et al. (41). Each ORF was represented by at least three different oligonucleotides.

RNA isolation and labeling.

E. coli strains EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pACYC184 and EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pJB11 were cultivated in LB medium overnight at 37°C. Quadruplicate cultures of a 1:100 dilution were grown to an OD600 of 0.85 to 0.95. One volume of cells was incubated with 2 volumes of RNAprotect solution and was processed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). Cell lysis and RNA preparation were carried out using the FastRNA Pro Blue kit (Qbiogene Inc.). After a 10-min treatment with RNase-free DNase I (Qiagen), the RNA was further purified utilizing the RNeasy MinElute kit (Qiagen). A total of 5 μg of RNA was labeled either with Cy-5-ULS or with Cy-3-ULS as described in the Kreatech ULS labeling manual (Kreatech Diagnostics), followed by determination of the RNA quality and degree of labeling with an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer and an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies). A dye swap was performed for two of the four cultures to minimize the effects of any labeling artifacts.

Fragmentation, microarray hybridization, scanning, and analysis.

Fragmentation, hybridization, and scanning of the microarray were performed at the Australian Genome Research Facility Ltd. (AGRF; Melbourne, Australia) as described previously (20). Normalization and data analysis were performed using the limma package in Bioconductor (52–54). Genes were considered differentially expressed if they showed an average change of ≥2-fold with an adjusted P value of ≤0.05.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

To verify global gene expression data, three independent bacterial cultures were grown as described above for the isolation of RNA used in microarray analysis. At an OD600 of 0.85 to 0.95, 1 ml of each culture was combined and treated with RNAprotect solution according to the manufacturers' instructions. About 2 μg of RNA (isolated as described above) was further treated with DNase I (2.7 Kunitz units) for 1 h at 37°C, followed by inactivation of the enzyme by addition of 2 μl of 25 mM EDTA and heating for 5 min at 65°C. Half the reaction mixture (10 μl) was subjected to reverse transcription utilizing SuperScript III reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). The lack of residual genomic DNA in each sample was verified prior to quantification of gene transcription. Primers for target gene quantification were designed by utilizing Primer3Plus (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi). Primer pairs hdeA-Fw/hdeA-Rv, slp-qPCR-fw/slp-qPCR-rv, espA-Fw/espA-Rv, and ICCrrsB-FRT/ICCrrsB-RRT were used to amplify hdeA, slp, espA, and 16S rRNA, respectively. The Brilliant II SYBR green QPCR master mix was used to perform PCR in real time as recommended by the manufacturer (Agilent Technologies). Reactions were performed in triplicate, and reaction mixtures contained 10 pmol of each primer in a total volume of 25 μl. Specific products were amplified and detected with the CFX96 Real-Time PCT detection system and a C1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories) by using the following protocol: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s and 60°C for 1 min. Data were analyzed using CFX Manager software (version 2.0; Bio-Rad). The threshold cycle (CT) values obtained for the target genes were normalized to the 16S rRNA and were expressed as the fold difference by calculating 2ΔΔCT.

Expression and purification of MBP::PatE.

The coding sequence of patE (z0321) was amplified from EDL933 genomic DNA by using primer pair Z0321MBPFw-BamHI/Z0321MBPRv-HindIII and was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to obtain plasmid pJB17. patE was excised by HindIII/BamHI digestion and was inserted into expression vector pMAL-c2x (New England BioLabs) for N-terminal fusion to malE. The resulting vector, pJB21, was transformed into E. coli strain BL21. Overnight cultures of transformants were diluted 1:100 into fresh LB broth and were grown at 30°C and 200 rpm to an OD600 of 0.9. Gene expression was induced for 19 h at 16°C by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.1 mM. Afterwards, bacterial cells were harvested (for 15 min at 3,000 × g and 4°C) and were disrupted by the addition of lysozyme (100 μg/ml) and subsequent sonication in column buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). PatE was purified through binding of the fusion protein to an amylose resin as recommended by the manufacturer (New England BioLabs). All steps were carried out at 4°C. The concentration and purity of eluted maltose binding protein (MBP)::PatE was determined by using a ND-1000 spectrophotometer, as well as by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of the fusion protein.

EMSA.

DNA fragments were labeled with 32P as follows. Primers hdeA-EMSA2-fw and hdeA-EMSAc-fw were labeled at their 5′ ends by using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. The DNA fragments to be analyzed for PatE binding were generated by PCR using primer pairs hdeA-EMSA2-fw/hdeA-EMSA2-rv (for fragment hdeAprom) and hdeA-EMSAc-fw/hdeA-EMSAc-rv (for fragment hdeAcontrol) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) from plasmids carrying either the entire promoter region of hdeA (pJB23, for hdeAprom) or part of the downstream coding sequences for the control experiment (pJB37, for hdeAcontrol). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were carried out as published previously (60). Briefly, each fragment was incubated with various amounts of purified MBP::PatE protein at 25°C for 30 min in binding buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.01% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5 ng/μl poly(dI-dC), 10% glycerol] in the absence or presence of a 100-fold molar excess of the unlabeled hdeAprom fragment. DNA and DNA-protein complexes were then separated on 5% native polyacrylamide gels (37.5:1) for approximately 12 h at 10 V/cm and 4°C.

Acid tolerance response assay.

To assess the influence of PatE on AR1, EHEC EDL933(Δstx1-2)/pACYC184 and EDL933(Δstx1-2)/pJB11 were cultivated for 20 h in LB broth at pH 7.0 or pH 5.5. For other experiments, bacteria were cultivated for 20 h in LB broth at pH 7.0 and were then stepwise diluted 1:1,000 in the challenge medium, LB broth adjusted to a final pH of 2.5 with HCl. Bacterial numbers before challenge (initial) were ∼1 × 106/ml as determined by plating serial dilutions of the inoculum onto LA plates. Survival was assessed after 2 h of incubation at 37°C under constant agitation (200 rpm) by enumerating viable counts. Data are expressed as the percentage of the initial inoculum surviving and are representative of at least two independent experiments carried out in triplicate. Resistance to volatile organic acids was determined as described above, with the addition of different molarities of sodium acetate to the challenge LB (pH 2.5) as indicated in Fig. 4B.

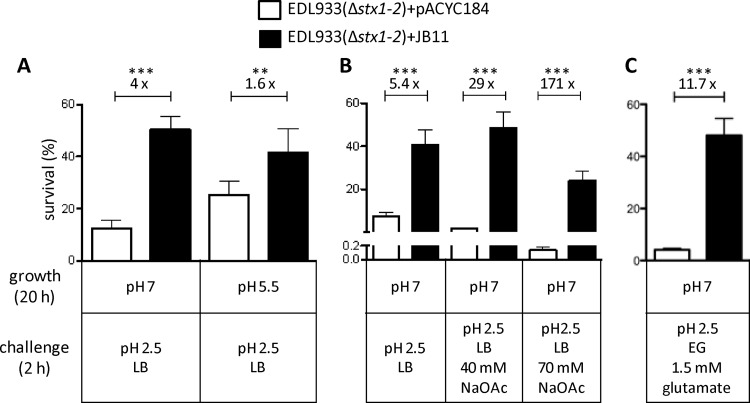

Fig 4.

Impact of overexpression of PatE on the survival of EHEC EDL933(Δstx1-2) under different acid challenge conditions. (A) The effect of overexpression of PatE on acid resistance system 1 (AR1) was analyzed under the following conditions: the control and test strains were grown in LB at pH 7.0 or pH 5.5 at 37°C for 20 h, after which ∼106 bacterial cells were challenged for 2 h with acidified medium (LB at pH 2.5). (B) The control and test strains were grown in LB (pH 7.0) for 20 h, and ∼106 bacterial cells were challenged in LB (pH 2.5) alone or supplemented with 40 mM or 70 mM sodium acetate (NaOAc). (C) The effect of overexpression of PatE on acid resistance system 2 (AR2) was assessed under the following conditions: the control and test strains were grown in LB (pH 7.0) at 37°C for 20 h, after which ∼106 bacterial cells were challenged for 2 h with EG medium (pH 2.5) supplemented with 1.5 mM glutamate. Survival is expressed as a percentage of the initial inoculum. Fold differences between the survival rates of the control [EDL933(Δstx1-2)/pACYC184] and test [EDL933(Δstx1-2)/pJB11] strains are shown above the bars for each comparison. Results are means for six experiments performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences by an unpaired two-tailed Student t test (***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.005).

To analyze the contribution of PatE to the glutamate-dependent pathway, AR2, bacteria were grown for 20 h in LB (pH 7.0), after which they were diluted 1:1,000 in EG medium (57) (pH 2.5) supplemented with 1.5 mM glutamate. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C and 200 rpm, bacterial viability was determined as described above.

Statistical methods.

Quantitative data were compared by using the two-tailed unpaired Student t test (Prism; GraphPad). P values of <0.05 were taken to indicate statistical significance.

Microarray data accession numbers.

The supporting microarray data for differentially expressed genes have been submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under GEO accession number GSE36922.

RESULTS

In silico identification of putative AraC-like regulators within O islands of EHEC strain EDL933.

To determine if EHEC carries any homologues of AraC-like virulence regulators, we screened the genome of EHEC strain EDL933 for nucleotide sequences homologous to regA from Citrobacter rodentium, toxT from Vibrio cholerae, aggR from enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), and rns from enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) by utilizing the BLASTn tool from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). In addition, a Pfam domain search (Pfam database; Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, United Kingdom) for the characteristic double HTH motif for DNA binding was conducted to verify candidates as putative regulatory proteins. Since EDL933 carries a number of housekeeping AraC-like regulators on its chromosomal backbone, we limited our search to open reading frames (ORFs) encoded by O islands, especially those located on prophage islands, because they could represent regulators acquired by horizontal gene transfer. Three ORFs encoding possible AraC-like regulators, which corresponded to z0321, z1789, and z2104, respectively, were identified. z2104 was predicted to result in a nonfunctional mature protein, due to the occurrence of a premature stop codon (41). However, our sequencing analysis of the genomic region revealed that ORF z2104 codes for a full-length protein (data not shown). The three putative regulatory proteins have similar molecular masses between ∼27 and 28 kDa (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

BLASTp analysis of the protein sequences showed that Z1789 and Z2104 are almost identical, with a similarity of 94%, whereas Z0321 differs substantially from the other two putative proteins, exhibiting ∼58% overall similarity to them (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). We next compared the protein sequences of Z0321, Z1789, and Z2104 with those of two well-characterized AraC-like virulence regulators, RegA and ToxT, by using the ClustalW2 multiple sequence alignment tool provided by the EMBL-EBI website (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/). All three putative regulators showed strong sequence conservation with RegA and ToxT within the double HTH motifs located at the C termini of the proteins (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). However, the N-terminal domains of Z0321, Z1789, and Z2104 (between residues 1 and 140) differed considerably from those of RegA and ToxT (see Fig. S1A).

z0321, z1789, and z2104 are transcriptionally and translationally active in vivo.

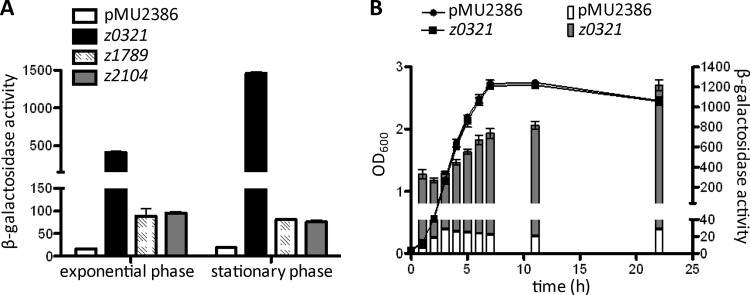

The fact that all three putative AraC-like regulators are encoded by intact open reading frames suggested that these proteins are expressed and are functionally active in vivo. To investigate this, we generated three constructs where the promoter regions of z0321, z1789, and z2104, from the 6th codon to a position ∼500 bp upstream of the predicted translational start site, were fused in frame with the lacZ structural gene on the single-copy-number translational-fusion vector pMU2386 (47). The resulting pMU2386 derivatives were each transformed into EHEC strain EDL933(Δstx1-2), and β-galactosidase assays were carried out following the growth of the transformants in LB to the exponential and stationary phases. The results (Fig. 1A) show that both the transcriptional and translational machineries of z0321, z1789, and z2104 were active, as evidenced by the fact that all three promoter-lacZ fusions produced significant levels of β-galactosidase activity. Similar expression patterns were observed for the z1789 and z2104 constructs, which synthesized approximately 75 Miller units (MU) of β-galactosidase in both the exponential and the stationary phase. In contrast, much stronger expression was seen for z0321, with 394 MU of β-galactosidase activity during the exponential phase, which increased 3.7-fold, to 1,440 MU, during the late-stationary phase (after 22 h of growth at 37°C) (Fig. 1A). The stationary-phase induction of z0321 expression was further confirmed by a time course analysis, which showed that z0321 promoter activity gradually increased from late-exponential to stationary phase (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

Promoter strength and translation efficiency of z0321, z1789, and z2104. β-Galactosidase activities from translational lacZ fusions of z0321, z1789, and z2104 were determined in both the exponential and stationary phases. β-Galactosidase activity is expressed in Miller units as defined by Miller (37). Data are means and standard deviations for three independent experiments carried out in duplicate. (A) The various EDL933(Δstx1-2) derivatives were either grown in LB at 37°C to an OD600 of ∼0.6 (exponential phase) or harvested after incubation for 22 h (stationary phase). (B) Analysis of z0321 expression over a period of 22 h.

During the course of this study, Tree et al. (55) reported their finding that Z1789 and Z2104 negatively regulate the expression of the EHEC type III secretion system (T3SS) through induction of the gadE and yhiF genes, encoding regulatory proteins involved in the transcriptional control of the LEE PAI (55). Consequently, we focused our investigation on the Z0321 protein. Z1789 and Z2104 are referred to below as PsrA and PsrB, respectively, the designations assigned to them by Tree at al (55).

Analysis of global gene transcription in response to Z0321.

Because Z0321 shares significant sequence homology, especially in the DNA binding domain, with PsrA and PsrB (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material), we hypothesized that there may be DNA targets of these putative regulators in the EHEC genome that are recognized by these three proteins. To identify those genes whose expression is controlled by Z0321 by using microarray analysis, we constructed an EDL933 strain in which all three alleles (z0321, psrA, and psrB) were deleted from the chromosome (see Materials and Methods). To create a nonhazardous EHEC strain that could be used safely in the laboratory, we also deleted both of the Shiga toxin genes (stx1 and stx2) (see Materials and Methods). The resulting strain, EDL933(Δz0321-psrA-psrB Δstx1-2), was designated EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2).

We next inserted a DNA fragment containing the z0321 coding sequence and its promoter region into the HindIII and BamHI sites of plasmid pACYC184 to form pJB11. This plasmid, which expresses z0321 from its own promoter, was transformed into EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2) to form EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pJB11. Total RNAs from both the control strain, EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pACYC184, and the z0321-complemented test strain, EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pJB11, were fluorescently labeled and were hybridized to a custom-made microarray chip covering all predicted open reading frames of the EDL933 genome (Agilent Technologies).

Analysis of the microarray data revealed that Z0321 significantly upregulated the expression of 10 genes (>2-fold) (Table 2). Interestingly, most of the Z0321-upregulated genes were located on an acid fitness island (AFI) (25), and 7 of the 10 genes are known to code for proteins that are involved in the acid resistance of E. coli. For example, hdeA and hdeB, which are expressed from the same operon, encode two acid stress chaperones that are required to prevent aggregation of periplasmic proteins at acidic pHs (26, 34). The gadB and gadC genes, which are located in the same gene cluster, code for the glutamate decarboxylase B and the glutamate–γ-amino butyric acid antiporter, two key components of AR2 in E. coli (15). The gadE gene encodes a LuxR-related regulator that is an essential activator for AR2 transcription (25, 33). The slp gene, encoding an outer membrane lipoprotein, can act to protect E. coli from the damage caused by its own organic acid metabolites produced and secreted during fermentation (36).

Table 2.

Genes upregulated by PatE, identified by use of microarray analysis

| ORFa | Gene | Predicted function | Fold activationb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z0604 | ybaR | P-type ATPase | 2.1 |

| Z1649 | Hypothetical protein | 2.4 | |

| Z2215 | gadB | Glutamate decarboxylase isozyme | 2.3 |

| Z2216 | gadC | Glutamate-GABAc antiporter | 2.2 |

| Z4908 | slp | Outer membrane lipoprotein | 11.3 |

| Z4921 | hdeB | Periplasmic chaperone | 5.3 |

| Z4922 | hdeA | Periplasmic chaperone | 10.3 |

| Z4923 | hdeD | Acid resistance at high cell density | 3.9 |

| Z4925 | gadE | LuxR family regulator | 3.4 |

| Z4926 | yhiU | Outer membrane protein involved in multidrug resistance | 2.2 |

ORF designations are given according to the EDL933 genome (GenBank accession no. AE005174.2).

Determined by comparing the log2 ratios of the transcript levels for strain EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pJB11 to those for strain EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pACYC184.

GABA, γ-amino butyric acid.

As shown in Table 2, the genes most highly activated by Z0321 were slp and hdeA, which were upregulated 11.3- and 10.3-fold, respectively. These results were confirmed by quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assays, in which Z0321-mediated activation was found to be 11.2-fold for hdeA and 10.1-fold for slp. Due to its role in the transcriptional activation of genes responsible for acid resistance, Z0321 was designated PatE, for prophage-encoded acid resistance transcriptional activator of EHEC.

Our microarray results also showed that PatE downregulates (between 2.0- and 5.7-fold) the expression of 18 genes (Table 3). These included three operons encoding heat shock proteins (grpE, ibpAB, clpYQ) and six genes located on the LEE (espA, espB, espZ, tir, z5137, and z5138), encoding type III secreted proteins and T3SS structural components (13). It is noteworthy that some of the PatE-regulated genes, such as the T3SS genes and the gadE gene (Table 2), are also subject to control by PsrA and PsrB (55), indicating that these three regulatory proteins might share some degree of DNA-binding specificity.

Table 3.

Genes downregulated by PatE, identified by use of microarray analysis

| ORFa | Gene | Predicted function | Fold repressionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z3242 | Hypothetical protein | −2.5 | |

| Z3796 | Hypothetical protein | −2.2 | |

| Z3797 | yfhO | KEGG database: cysteine desulfurase | −2.1 |

| Z3907 | grpE | Heat shock protein | −2.4 |

| Z4769 | yhgI | Hypothetical protein | −2.2 |

| Z5105 | espB | Type III secreted translocator | −2.4 |

| Z5107 | espA | Type III secreted protein | −2.4 |

| Z5112 | tir | Translocated intimin receptor protein | −2.0 |

| Z5122 | espZ | Type III secreted effector | −2.2 |

| Z5137 | Putative component of T3SS | −2.9 | |

| Z5138 | Putative component of T3SS | −2.7 | |

| Z5182 | ibpB | Heat shock protein | −5.7 |

| Z5183 | ibpA | Heat shock protein | −2.4 |

| Z5204 | tnaB | Low-affinity tryptophan transporter | −2.1 |

| Z5232 | atpA | ATP synthase, alpha subunit | −2.2 |

| Z5233 | atpH | ATP synthase, delta subunit | −2.0 |

| Z5478 | clpY | Heat shock protein, two-component protease | −2.7 |

| Z5479 | clpQ | Heat shock protein, two-component protease | −2.4 |

ORF designations are given according to the EDL933 genome (accession no. AE005174.2).

Determined by comparing the log2 ratios of the transcript levels for strain EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pJB11 to those for strain EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pACYC184.

Identification of a cis-acting element required for activation of hdeA expression by PatE.

To examine whether the PatE protein is a direct transcriptional regulator that is able to interact with a DNA target, we carried out an in vivo transcriptional experiment using a lacZ reporter system. The hdeA promoter was chosen for this analysis because hdeA is one of the most strongly upregulated gene targets identified for PatE (Table 2).

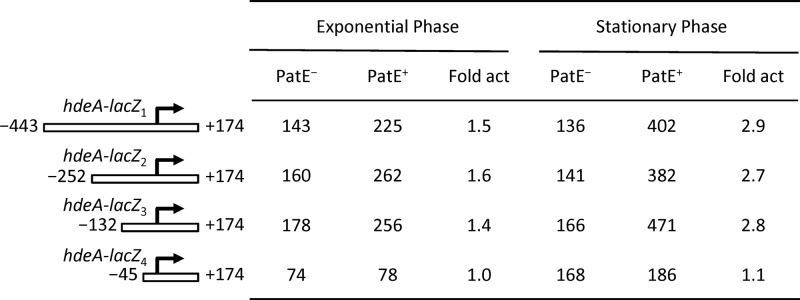

We first constructed an hdeA promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusion by cloning a DNA fragment, spanning positions −443 and +174 relative to the transcriptional start site of hdeA, in front of the lacZ structural gene of the single-copy-number vector pJP1433. The resulting plasmid, pJB29 (hdeA-lacZ1), was transformed into the PatE− and PatE+ EHEC strains EDL933(Δ3)/pACYC184 and EDL933(Δ3)/pJB11, respectively. The hdeA promoter activities of the two EHEC derivatives were then measured by β-galactosidase assays after growth of the strains in LB to the exponential and stationary phases. As shown in Fig. 2, in the exponential phase, the hdeA promoter was moderately active in a PatE− background, producing 143 MU of β-galactosidase activity, whereas in the PatE+ background, the promoter activity increased 1.5-fold, to 225 MU. In stationary phase, the PatE-mediated activation of hdeA transcription increased further, to 3-fold. These results confirmed the positive regulatory effect of the PatE protein on hdeA transcription observed in microarrays and quantitative real-time RT-PCR assays and demonstrated the presence of a cis-acting element between positions −443 and +174 of the hdeA promoter that is involved in PatE-mediated activation.

Fig 2.

β-Galactosidase expression of four different hdeA-lacZ fusions in the PatE− and PatE+ backgrounds. The numbering of the various hdeA fragments is relative to the hdeA transcriptional start site. The values for β-galactosidase activity are means and standard deviations for three independent assays. Promoter activities were determined for bacteria grown to the exponential or stationary phase in LB at 37°C. The fold activation (fold act) is the value for the β-galactosidase activity of the PatE+ strain EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pJB11 divided by that of the PatE− control EDL933(Δ3 Δstx1-2)/pACYC184.

To further map the cis-acting element within the hdeA regulatory region, we created three more promoter-lacZ fusions (pJB52 [hdeA-lacZ2], pJB51 [hdeA-lacZ3], and pJB50 [hdeA-lacZ4]), which carried various truncations in the upstream region of the hdeA promoter (Fig. 2). The results of β-galactosidase assays showed that the hdeA-lacZ2 (−252 to +174) and hdeA-lacZ3 (−132 to +174) deletion constructs exhibited the same degree of activation by PatE in both the exponential and stationary phases as that observed for the original hdeA-lacZ1 construct. This indicated that these two truncated constructs retained an intact cis-acting element (Fig. 2). In contrast, further deletion toward the promoter core elements to position −45 (the hdeA-lacZ4 construct) led to the complete loss of transcriptional activation by PatE (Fig. 2). This deletion analysis located the cis-acting element somewhere between positions −132 and −45.

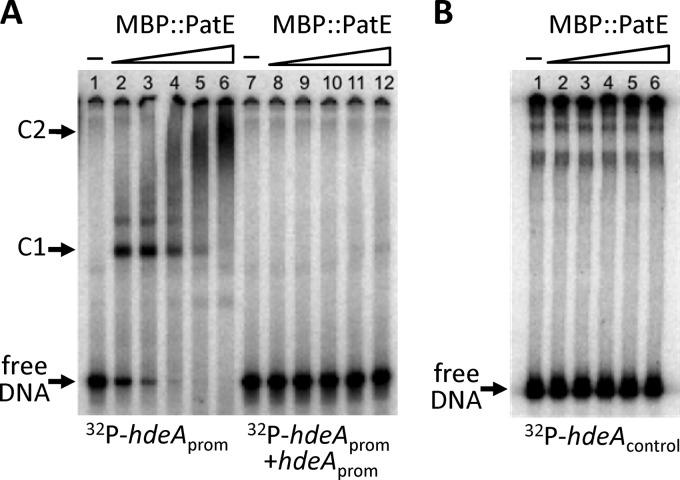

Specific interaction of PatE with the hdeA promoter region.

To test whether PatE can bind directly to the hdeA regulatory region, we performed an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). For this, we first constructed a plasmid that expressed a fusion protein (MBP::PatE) in which the C terminus of the maltose binding protein (MBP) was fused to the N terminus of PatE. The fusion protein (MBP::PatE) was purified and used in the EMSA. A 302-bp hdeA promoter fragment that spanned the region between positions −252 and +50 relative to the start site of transcription was end labeled with 32P and was incubated with varying amounts of MBP::PatE. As shown in Fig. 3, in the absence of MBP::PatE, the hdeA fragment migrated to the bottom of the gel during electrophoresis to form a free DNA band (Fig. 3A, lane 1). However, this band gradually disappeared after the addition of increasing amounts of MBP::PatE to the reaction mixture (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 to 6). At the same time, a major retarded band (C1) representing a protein-DNA complex was seen when MBP::PatE was added at final concentrations between 9 and 75 nM (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 to 5). Furthermore, as the concentration of MBP::PatE increased (from 9 to 150 nM), the intensity of the C1 band gradually faded, while a larger, smeared protein-DNA complex (C2) appeared (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 to 6), suggesting the possibility of oligomerization of the MBP::PatE protein on its DNA binding site.

Fig 3.

EMSA analysis of the binding of the fusion protein MBP::PatE to the hdeA promoter region. 32P-labeled PCR fragments were incubated for 30 min at 25°C with increasing amounts of MBP::PatE, after which the samples were analyzed on native polyacrylamide gels. Unbound DNA (free DNA) and DNA-protein complexes (C1 and C2) are indicated. (A) The hdeA promoter fragment (positions −252 to +50 relative to the transcriptional start site) was mixed with 0, 9, 18, 36, 75, or 150 nM MBP::PatE in the absence (lanes 1 to 6) or presence (lanes 7 to 12) of a 100-fold molar excess of an unlabeled hdeA promoter fragment. Densitometric analysis (using the MF-ChemiBIS 3.2 system [DNR Bio-Imaging Systems]) showed that the concentration of MBP::PatE required to shift approximately half of the hdeA fragment (the dissociation constant [Kd]) was 9 nM. (B) A control fragment containing the coding region of hdeA (between positions +162 and +363 relative to the transcriptional start site) was incubated with 0, 9, 18, 38, 75, or 150 nM MBP::PatE.

The data in the right panel of Fig. 3A (lanes 7 to 12) show that the addition of a specific cold competitor (the unlabeled 302-bp hdeA promoter fragment) could outcompete the binding of MBP::PatE to the labeled probe, demonstrating that PatE bound specifically to the hdeA promoter region.

A control experiment involving the use of a 32P-labeled DNA fragment covering a sequence within the coding region of the hdeA gene (between positions +162 and +363 relative to the transcriptional start site) was also carried out. As shown in Fig. 3B, MBP::PatE failed to bind to this DNA fragment, confirming the binding specificity of PatE for the hdeA regulatory region.

Increasing the expression of PatE enhances the resistance of EHEC EDL933 to acidic conditions.

Our data from the microarray and other transcriptional assays indicated the involvement of the PatE protein in the induction of acid stress response genes in EHEC. To determine if PatE influenced bacterial resistance to acid, we performed a series of acid tolerance response assays. We first investigated a PatE− strain, but no difference was observed in acid tolerance between the PatE− mutant [EDL933(Δ1 Δstx1-2)] and its isogenic PatE+ counterpart [EDL933(Δstx1-2)] (data not shown). Because this may have been due to redundancy, we then examined cells in which PatE was overexpressed.

To achieve this, we transformed the PatE-expressing multicopy plasmid pJB11 and the control vector pACYC184 separately into EHEC strain EDL933(Δstx1-2). To assess the impact of PatE on AR1, the transformants were grown for 20 h in LB with an adjusted pH value of either 7.0 or 5.5. Culturing the bacteria at pH 5.5 prior to acid challenge is known to induce resistance, whereas bacteria grown in LB at pH 7.0 are more susceptible to acidified media (7). Following growth under these conditions, the bacterial cells were challenged with acidified LB (pH 2.5) at 37°C for 2 h and were then enumerated on LA plates. The results showed that increasing the expression of PatE resulted in elevated levels of resistance of the test strain EDL933(Δstx1-2)/pJB11, whose survival rate increased 1.6- and 4-fold over that of the control strain EDL933(Δstx1-2)/pACYC184 when the bacteria were cultivated at pH 5.5 and pH 7, respectively (Fig. 4A).

The periplasmic chaperones HdeA and HdeB, as well as the lipoprotein Slp, are known to confer resistance to volatile organic acids and fermentation end products (36). Because the three genes (hdeA, hdeB, and slp) were all highly upregulated by PatE (Table 2), it seemed likely that PatE would enhance the ability of EHEC to survive in the presence of organic acids. To test this hypothesis, we grew bacterial cells overnight in LB (pH 7) and challenged the bacteria with LB (pH 2.5) alone or LB (pH 2.5) supplemented with either 40 mM or 70 mM sodium acetate. As expected, the survival rate of test strain EDL933(Δstx1-2)/pJB11 was higher (5.4-fold) than that of the control strain EDL933(Δstx1-2)/pACYC184 when challenged with LB (pH 2.5) in the absence of sodium acetate (Fig. 4B). The increases in the percentages of survival of the test strain over those of the control strain were 29- and 171-fold upon challenge with LB (pH 2.5) in the presence of 40 mM and 70 mM sodium acetate, respectively (Fig. 4B).

Our observation that PatE activates the transcription of the gadBC and gadE genes, which encode proteins that are the essential components of a highly efficient and glutamate-dependent acid stress response system (AR2) (64) (Table 2), suggested a positive role for PatE in inducing AR2. Accordingly, we investigated the effect of PatE on AR2 by using the methods previously described by Castanie-Cornet et al. (7). Bacterial cultures grown in LB (pH 7) were challenged with EG medium (pH 2.5) supplemented with 1.5 mM glutamate, after which the survival rates of the bacterial samples were measured (see Materials and Methods). The results (Fig. 4C) demonstrated that while only 4.5% of cells of the control strain EDL933(Δstx1-2)/pACYC184 survived a 2-h acid exposure, ∼47% of cells of the PatE-overexpressing strain EDL933(Δstx1-2)/pJB11 remained viable under the same experimental conditions.

DISCUSSION

The AraC family of transcriptional regulators comprises versatile proteins that control the transcription of genes involved in carbon metabolism, stress responses, and pathogenesis (17). In enteric bacterial pathogens, the genes encoding virulence-associated AraC-like regulators, such as ToxT, Rns, AggR, PerA, and RegA, appear to have coevolved with their principal target virulence genes through horizontal gene transfer. Consequently, the genes encoding these virulence regulators and their targets are typically colocated within the same genetic region. In this study, however, we identified a gene from the prophage island CP933H of EHEC strain EDL933 that encodes an AraC-like regulator, PatE, which activates the transcription of genes on an acid resistance island on the chromosomal backbone (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material).

The ability of EHEC O157 to resist acid (64) assists its passage through the human stomach, thus accounting for its low infectious dose (48). The extraordinary ability of EHEC to break through the acid barrier has previously been attributed to its efficient expression of various acid stress response systems. Our current study has shown that PatE enhances the production of acid resistance proteins, such as HdeA, HdeB, Slp, GadA, and GadB, which give rise to AR1- and AR2-mediated protection of EDL933 in low-pH environments (Table 2; Fig. 2 and 4). Our analysis using the patE-lacZ translational fusions demonstrated strong expression of the patE gene in E. coli (Fig. 1). Expression of patE was significantly higher in stationary phase than in exponential phase, suggesting that the patE promoter might be inducible by the alternative sigma subunit of RNA polymerase, σs. These results are in agreement with those of Dong et al. (14), who observed a 6-fold decrease in patE (z0321) transcription in an rpoS mutant of EDL933 from that in the wild-type strain. Furthermore, the intracellular concentration of σs also increases dramatically when bacterial cells enter stationary phase (27) or are exposed to acid (23). Thus, the connection of patE expression to the σs regulatory circuit leads to the formation of an additional positive regulatory loop that allows EHEC to sense and transduce an acid stress signal via PatE to the two important acid resistance pathways, AR1 and AR2.

Our microarray analysis showed that PatE downregulates the expression of two main groups of genes, one encoding heat shock proteins and the other, in the LEE, encoding the T3SS and its secreted proteins (Table 3). Presumably, the repression of these genes by PatE helps EHEC conserve energy and resources for the production of acid resistance proteins within acidic environments, such as acidic foods and the stomach. Tree et al. (55) recently reported their analysis of the control of the LEE-encoded T3SS genes by the two AraC-like regulators PsrA and PsrB. They showed that downregulation of the T3SS genes by PsrA and PsrB is achieved indirectly via transcriptional activation of the gene encoding GadE, which represses the transcription of the LEE directly (29, 55). Their EMSA experiments showed that PsrA and PsrB bind to the gadE regulatory region and that GadE interacts specifically with the LEE1 and LEE2/LEE3 promoters. Interestingly, gadE is one of the genes we found to be upregulated by PatE in this study (Table 2). Given the sequence similarity in the HTH DNA-binding motifs of the PsrA, PsrB, and PatE proteins (Fig. 1B), it is not surprising that repression of the T3SS genes by PatE occurs via the same pathway as that used by PsrA and PsrB.

Some AraC-like virulence regulators can sense environmental signals at the sites where the bacteria interact with their host. For example, the C. rodentium RegA and V. cholerae ToxT proteins, which are responsible for the upregulation of genes encoding colonization factors, respond to bicarbonate, which is abundant in the intestinal lumen at the site of colonization (1, 60). Upon entering the bacterial cell, bicarbonate binds to the regulatory proteins and stimulates their activity, leading to the expression of proteins that the bacteria require to attach to the intestinal epithelium. A detailed molecular analysis of RegA revealed that the N-terminal tip (aa 2 to 16) of this protein is critical for bicarbonate sensing (60). However, the corresponding region is absent from PatE, and the induction of the hdeA promoter does not require the presence of bicarbonate (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material) (data not shown). Since PatE activates the expression of acid tolerance genes at low pHs, bicarbonate sensing by PatE is not required. Instead, the expression of patE is evidently activated by σs RNA polymerase, the expression of which is subject to the induction of acid stress, a biophysical cue, from the host stomach.

Our transcriptional analysis using microarrays, promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusions, and EMSA demonstrated that PatE directly activates the transcription of the hdeAB-yhiD operon by binding to the regulatory region immediately upstream of the hdeA promoter sequence. The hdeA promoter is subject to regulation by multiple regulatory proteins, including both global and specific repressors and activators (EcoCyc database [http://ecocyc.org/ECOLI]). For example, transcription of hdeA is repressed by H-NS, Lrp, and MarA, activated by TorR and GadE, and both negatively and positively regulated by GadW and GadX (5, 25, 28, 45, 49, 50). The complexity of regulation reflects the importance of the operon that codes for HdeA, one of the most abundant periplasmic proteins in the stationary phase of growth and under acidic conditions (22, 32). The connection of the hdeA promoter to complex circuits of regulatory pathways allows the expression of the hdeAB-yhiD operon to respond to multiple environmental signals, because delicately balanced expression of this operon is essential for the fitness of E. coli in a variety of environments. Our current work indicates that EHEC O157:H7 has acquired an additional regulatory gene, patE, which activates the hdeAB-yhiD cluster and other acid resistance operons. Our findings exemplify how bacterial pathogens may enhance their virulence capacity by fine-tuning their regulatory mechanisms through the evolution of horizontally acquired genes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work in the authors' laboratory is supported by research grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. J.K.B. was supported by a fellowship from the Postdoc-Program of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 May 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abuaita BH, Withey JH. 2009. Bicarbonate induces Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression by enhancing ToxT activity. Infect. Immun. 77:4111–4120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Athanasopoulos V, Praszkier J, Pittard AJ. 1995. The replication of an IncL/M plasmid is subject to antisense control. J. Bacteriol. 177:4730–4741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bearson S, Bearson B, Foster JW. 1997. Acid stress responses in enterobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 147:173–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bhagwat AA, et al. 2005. Characterization of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli strains based on acid resistance phenotypes. Infect. Immun. 73:4993–5003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bordi C, Theraulaz L, Mejean V, Jourlin-Castelli C. 2003. Anticipating an alkaline stress through the Tor phosphorelay system in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 48:211–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Breuer T, et al. 2001. A multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections linked to alfalfa sprouts grown from contaminated seeds. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:977–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castanie-Cornet MP, Penfound TA, Smith D, Elliott JF, Foster JW. 1999. Control of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:3525–3535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chalker AF, et al. 2001. Systematic identification of selective essential genes in Helicobacter pylori by genome prioritization and allelic replacement mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 183:1259–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang AC, Cohen SN. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134:1141–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cummings JH. 1981. Short chain fatty acids in the human colon. Gut 22:763–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Currie A, et al. 2007. Outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections associated with consumption of beef donair. J. Food Prot. 70:1483–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deng W, et al. 2004. Dissecting virulence: systematic and functional analyses of a pathogenicity island. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:3597–3602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dong T, Schellhorn HE. 2009. Global effect of RpoS on gene expression in pathogenic Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL933. BMC Genomics 10:349 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foster JW. 2004. Escherichia coli acid resistance: tales of an amateur acidophile. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:898–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frankel G, et al. 1998. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: more subversive elements. Mol. Microbiol. 30:911–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gallegos MT, Schleif R, Bairoch A, Hofmann K, Ramos JL. 1997. Arac/XylS family of transcriptional regulators. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:393–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gorden J, Small PL. 1993. Acid resistance in enteric bacteria. Infect. Immun. 61:364–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hancock DD, et al. 1994. The prevalence of Escherichia coli O157.H7 in dairy and beef cattle in Washington State. Epidemiol. Infect. 113:199–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hart E, et al. 2008. RegA, an AraC-like protein, is a global transcriptional regulator that controls virulence gene expression in Citrobacter rodentium. Infect. Immun. 76:5247–5256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hayashi T, et al. 2001. Complete genome sequence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and genomic comparison with a laboratory strain K-12. DNA Res. 8:11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hayes ET, et al. 2006. Oxygen limitation modulates pH regulation of catabolism and hydrogenases, multidrug transporters, and envelope composition in Escherichia coli K-12. BMC Microbiol. 6:89 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-6-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hengge-Aronis R. 2002. Signal transduction and regulatory mechanisms involved in control of the σS (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:373–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hilborn ED, et al. 2000. An outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections and haemolytic uraemic syndrome associated with consumption of unpasteurized apple cider. Epidemiol. Infect. 124:31–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hommais F, et al. 2004. GadE (YhiE): a novel activator involved in the response to acid environment in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 150:61–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hong W, et al. 2005. Periplasmic protein HdeA exhibits chaperone-like activity exclusively within stomach pH range by transforming into disordered conformation. J. Biol. Chem. 280:27029–27034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishihama A. 2000. Functional modulation of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:499–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnson MD, Burton NA, Gutierrez B, Painter K, Lund PA. 2011. RcsB is required for inducible acid resistance in Escherichia coli and acts at gadE-dependent and -independent promoters. J. Bacteriol. 193:3653–3656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kailasan Vanaja S, Bergholz TM, Whittam TS. 2009. Characterization of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 Sakai GadE regulon. J. Bacteriol. 191:1868–1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Karch H, Tarr PI, Bielaszewska M. 2005. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli in human medicine. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 295:405–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin J, Lee IS, Frey J, Slonczewski JL, Foster JW. 1995. Comparative analysis of extreme acid survival in Salmonella typhimurium, Shigella flexneri, and Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:4097–4104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Link AJ, Robison K, Church GM. 1997. Comparing the predicted and observed properties of proteins encoded in the genome of Escherichia coli K-12. Electrophoresis 18:1259–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma Z, et al. 2003. GadE (YhiE) activates glutamate decarboxylase-dependent acid resistance in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1309–1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malki A, et al. 2008. Solubilization of protein aggregates by the acid stress chaperones HdeA and HdeB. J. Biol. Chem. 283:13679–13687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martin RG, Rosner JL. 2001. The AraC transcriptional activators. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:132–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mates AK, Sayed AK, Foster JW. 2007. Products of the Escherichia coli acid fitness island attenuate metabolite stress at extremely low pH and mediate a cell density-dependent acid resistance. J. Bacteriol. 189:2759–2768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nataro JP, Kaper JB. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O'Brien AD, Lively TA, Chang TW, Gorbach SL. 1983. Purification of Shigella dysenteriae 1 (Shiga)-like toxin from Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain associated with haemorrhagic colitis. Lancet ii:573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pennington H. 2010. Escherichia coli O157. Lancet 376:1428–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Perna NT, et al. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Posfai G, Koob MD, Kirkpatrick HA, Blattner FR. 1997. Versatile insertion plasmids for targeted genome manipulations in bacteria: isolation, deletion, and rescue of the pathogenicity island LEE of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 genome. J. Bacteriol. 179:4426–4428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rangel JM, Sparling PH, Crowe C, Griffin PM, Swerdlow DL. 2005. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreaks, United States, 1982-2002. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:603–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rasmussen MA, Cray WC, Jr, Casey TA, Whipp SC. 1993. Rumen contents as a reservoir of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 114:79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ruiz C, McMurry LM, Levy SB. 2008. Role of the multidrug resistance regulator MarA in global regulation of the hdeAB acid resistance operon in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 190:1290–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Russell JB, Diez-Gonzalez F, Jarvis GN. 2000. Potential effect of cattle diets on the transmission of pathogenic Escherichia coli to humans. Microbes Infect. 2:45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sarsero JP, Pittard AJ. 1995. Membrane topology analysis of Escherichia coli K-12 Mtr permease by alkaline phosphatase and beta-galactosidase fusions. J. Bacteriol. 177:297–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schmid-Hempel P, Frank SA. 2007. Pathogenesis, virulence, and infective dose. PLoS Pathog. 3:1372–1373 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.003147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schneiders T, Barbosa TM, McMurry LM, Levy SB. 2004. The Escherichia coli transcriptional regulator MarA directly represses transcription of purA and hdeA. J. Biol. Chem. 279:9037–9042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shin M, et al. 2005. DNA looping-mediated repression by histone-like protein H-NS: specific requirement of Esigma70 as a cofactor for looping. Genes Dev. 19:2388–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Small P, Blankenhorn D, Welty D, Zinser E, Slonczewski JL. 1994. Acid and base resistance in Escherichia coli and Shigella flexneri: role of rpoS and growth pH. J. Bacteriol. 176:1729–1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smyth G. 2005. limma: linear models for microarray data, p 397–420 In Gentleman R, Carey VJ, Huber W, Irizarry RA, Dudoit S. (ed), Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 53. Smyth GK. 2004. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3: Article 3. doi:10.2202/1554-6115.1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Smyth GK, Speed T. 2003. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods 31:265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tree JJ, et al. 2011. Transcriptional regulators of the GAD acid stress island are carried by effector protein-encoding prophages and indirectly control type III secretion in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 80:1349–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tzipori S, et al. 1986. The pathogenesis of hemorrhagic colitis caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7 in gnotobiotic piglets. J. Infect. Dis. 154:712–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vogel HJ, Bonner DM. 1956. Acetylornithinase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem. 218:97–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Whipp SC, Rasmussen MA, Cray WC., Jr 1994. Animals as a source of Escherichia coli pathogenic for human beings. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 204:1168–1175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang J, et al. 2009. Bicarbonate-mediated stimulation of RegA, the global virulence regulator from Citrobacter rodentium. J. Mol. Biol. 394:591–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yang J, et al. 2008. Bicarbonate-mediated transcriptional activation of divergent operons by the virulence regulatory protein, RegA, from Citrobacter rodentium. Mol. Microbiol. 68:314–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yang J, Tauschek M, Hart E, Hartland EL, Robins-Browne RM. 2010. Virulence regulation in Citrobacter rodentium: the art of timing. Microb. Biotechnol. 3:259–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yang J, Tauschek M, Robins-Browne RM. 2011. Control of bacterial virulence by AraC-like regulators that respond to chemical signals. Trends Microbiol. 19:128–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yang J, Tauschek M, Strugnell R, Robins-Browne RM. 2005. The H-NS protein represses transcription of the eltAB operon, which encodes heat-labile enterotoxin in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, by binding to regions downstream of the promoter. Microbiology 151:1199–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhao B, Houry WA. 2010. Acid stress response in enteropathogenic gammaproteobacteria: an aptitude for survival. Biochem. Cell Biol. 88:301–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhou Z, et al. 2010. Derivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from its O55:H7 precursor. PLoS One 5:e8700 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.