Abstract

The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 thiol peroxidase homolog (Tpx) belongs to a family of enzymes implicated in the removal of toxic peroxides. We have shown the expression of tpx to be highly inducible with redox cycling/superoxide generators and diamide and weakly inducible with organic hydroperoxides and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The PAO1 tpx pattern is unlike the patterns for other peroxide-scavenging genes in P. aeruginosa. Analysis of the tpx promoter reveals the presence of a putative IscR binding site located near the promoter. The tpx expression profiles in PAO1 and the iscR mutant, together with results from gel mobility shift assays showing that purified IscR specifically binds the tpx promoter, support the role of IscR as a transcriptional repressor of tpx that also regulates the oxidant-inducible expression of the gene. Recombinant Tpx has been purified and biochemically characterized. The enzyme catalyzes thioredoxin-dependent peroxidation and can utilize organic hydroperoxides and H2O2 as substrates. The Δtpx mutant demonstrates differential sensitivity to H2O2 only at moderate concentrations (0.5 mM) and not at high (20 mM) concentrations, suggesting a novel protective role of tpx against H2O2 in P. aeruginosa. Altogether, P. aeruginosa tpx is a novel member of the IscR regulon and plays a primary role in protecting the bacteria from submillimolar concentrations of H2O2.

INTRODUCTION

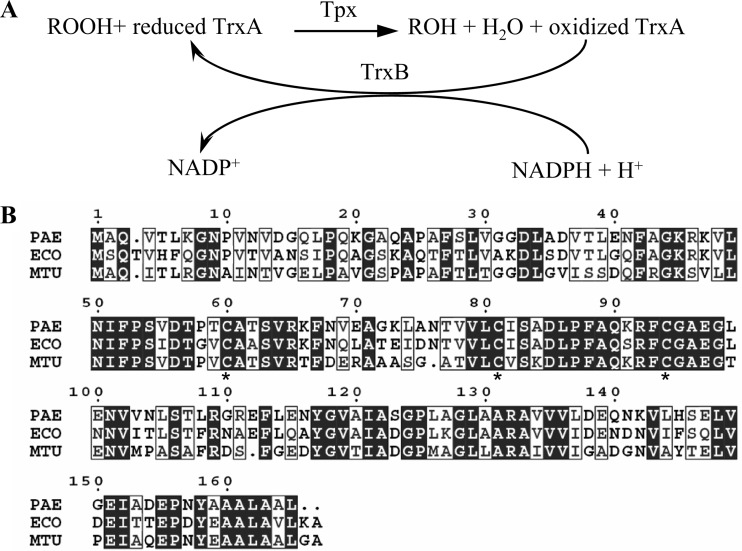

Thiol peroxidase (Tpx), formerly known as p20 or scavengase (9), is a member of the peroxiredoxin family that is widely distributed among prokaryotic organisms (20). Tpx contains thiol-dependent peroxidase activity and is capable of reducing either organic hydroperoxides or H2O2 by using reduced thioredoxin (Trx) as an electron donor. The resultant oxidized thioredoxin is cycled back to the reduced form by the thioredoxin reductase reaction, which utilizes NADPH as a reductant (Fig. 1A) (3, 9, 29). Tpx belongs to a group of atypical 2-Cys peroxiredoxins, as it contains two redox-active cysteine residues that correspond to Cys-61 and Cys-95 of the Escherichia coli Tpx (3, 9, 46). In the presence of peroxides, the peroxidatic Cys-61 reacts with the peroxide substrates and is oxidized to the sulfenic acid intermediate, which in turn reacts with the resolving Cys-95 to form an intermolecular disulfide bond (3).

Fig 1.

Peroxide reduction by Tpx and alignment of Tpx enzymes. (A) Schematic diagram showing the reduction of peroxide (ROOH) to its corresponding alcohol (ROH) as summarized from previous reports (3, 9, 29). (B) Alignment of putative Tpx from P. aeruginosa (PAE), E. coli (ECO), and M. tuberculosis (MTB) as performed using Clustal W2 (36). Asterisks indicate conserved cysteine residues that were mutated.

An E. coli tpx mutant displays sensitive phenotypes to both H2O2 and organic hydroperoxides (t-butyl and cumene hydroperoxides) and a superoxide generator, paraquat (PQ) (8). This picture strongly supports the physiological role of Tpx in the oxidative stress protection of E. coli.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a Gram-negative nonfermentative bacterium, is one of the leading causes of lethal hospital-acquired infections (7) and of chronic pulmonary infections in patients with cystic fibrosis (26). Upon invasion of a human host, the bacteria encounter an innate immune response that is the first line of defense against the infecting pathogens. The bacteria also have to confront reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in the phagolysosome, including superoxide anions, H2O2, and peroxynitrite. In addition, the bacteria are also exposed to ROS from their own by-products of aerobic metabolism, during exposure to chemicals and when interacting with other microbes in the environment. P. aeruginosa has evolved multiple strategies to overcome these deleterious conditions. A number of ROS-scavenging enzymes have been reported to play a physiological role in oxidative stress protection. P. aeruginosa produces several isozymes of superoxide dismutases to dismutate superoxide anions, catalases to detoxify H2O2, and peroxiredoxins to detoxify peroxides, including both organic hydroperoxides and H2O2 (2, 6, 24, 25, 39, 41, 42). Here, we report the biochemical, genetic, and physiological characterization of tpx and reveal it to be an important member of a group of peroxide removal genes that protect P. aeruginosa from oxidative stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial growth conditions.

P. aeruginosa PAO1 and mutant strains were cultured aerobically in LB medium at 37°C with continuous shaking (150 rpm). Exponential-phase cells were used routinely in all experiments.

Purification of P. aeruginosa Tpx, thioredoxin (TrxA), and thioredoxin reductase (TrxB).

Tpx protein from P. aeruginosa was purified using the E. coli expression system. A putative tpx gene (PA2532) was amplified from the PAO1 genomic DNA with primers BT2864 (5′-ATCAACGCCATGGCTCAAG-3′) and BT2865 (5′-GGAGAGCCGCCAGGGCCG-3′). The PCR product was digested with NcoI before being cloned into the pETBlue-2 vector (Novagen) digested with NcoI and XhoI (blunt ended) to produce pET-tpx for high expression of Tpx with a C-terminal His6 tag. An E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS strain harboring pET-tpx was grown aerobically in LB medium containing 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin at 37°C until the culture reached an optical density of approximately 0.6 to 0.8 at 600 nm (OD600). The culture was then induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and allowed to grow for an additional 3 h. Cells were harvested, resuspended in binding buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 300 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.0), and sonicated intermittently until being completely lysed. The clear lysate was loaded onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose column (Invitrogen) equilibrated with the binding buffer. The unbound proteins were washed with washing buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.0). The Tpx protein was eluted with elution buffer (50 mM phosphate buffer, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 7.0), and the eluent was dialyzed against the dialysis buffer (50 mM phosphate buffer, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.0). The purity of Tpx was estimated to be 90% based on a Coomassie blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

The full-length trxB (PA2616) was PCR amplified from the PAO1 genomic DNA with primers BT2982 (5′-CTTTCCATGGGTGAAGTCAAGCAT-3′) and BT2983 (5′-GTCCTCGAGATGGTCGTCGAGGTA-3′). The product was cut with NcoI prior to cloning into pETBlue-2 digested with NcoI and XhoI (gap filled with Klenow fragment), yielding pETtrxB for high expression of TrxB with C-terminal His6-tag. Purification of TrxB from E. coli harboring pETtrxB was similar to that described for Tpx purification.

To purify P. aeruginosa TrxA (PA5240), pET11a-trxA (L. B. Poole, unpublished data), a plasmid for high-level expression of nontagged TrxA protein, was introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3). Bacteria were harvested, and the cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (5 mM EDTA, 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 25 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) before being lysed using a French press. The clear lysate was loaded onto a DEAE cellulose column equilibrated with 25 mM phosphate buffer, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.0. The unbound proteins were washed with 250 mM phosphate buffer, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.0. The bound proteins were eluted with a linear phosphate gradient from 250 to 500 mM containing 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.0. The partially purified TrxA was precipitated with 80% ammonium sulfate prior to loading onto the Superdex G-75 column preequilibrated with 100 mM phosphate buffer, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.0. The column was eluted with the same buffer to obtain the purified TrxA.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of Tpx.

Michaelis constants (Km) and turnover numbers (kcat) of P. aeruginosa Tpx with peroxide substrates were determined by measuring initial reaction velocities at various concentrations of peroxides and at saturating concentrations of TrxA (100 μM). The initial Tpx reaction velocities were measured from the absorbance decrease at 340 nm due to the oxidation of NADPH in the TrxB-coupled reaction as described for E. coli Tpx (3) (Fig. 1A). The reaction mixture typically consists of 50 mM phosphate buffer, 0.5 mM EDTA (pH 7), 150 μM NADPH, 100 μM purified P. aeruginosa TrxA, 1.5 μM purified P. aeruginosa TrxB, 0.05 μM purified Tpx, and various concentrations of peroxides (H2O2, cumene hydroperoxide [CHP], and t-butyl hydroperoxide [BHP]).

Construction of P. aeruginosa mutants.

The Δtpx mutant was constructed using the allelic exchange method with a cre-lox antibiotic marker recycling system (40). A 1,390-bp DNA fragment containing the tpx gene plus the sequences flanking both tpx termini was PCR amplified from PAO1 genomic DNA with the primers BT2387 (5′-ACTACATCCTGTCGCTGG-3′) and BT2388 (5′-GGAAAGCCTGCGTGACGA-3′) and subsequently cloned into a pUC18 plasmid cut with HincII, yielding pUCtpx. The SalI and EcoRI (blunt-ended) fragment containing a gentamicin resistance (Gmr) cassette flanked with lox sequences from pUC18Gm (pUC18 containing lox-flanked Gmr, which is constructed by inserting SacI-EcoRI fragments containing lox-flanked Gmr from pCM351 [40] into pUC18 cut with the same enzymes) was cloned into pUCtpx digested with BstXI (blunt ended) and XhoI, yielding pUCΔtpx::Gm. Digestion with BstXI-XhoI deleted 109 bp of the internal sequence of tpx. pUCΔtpx::Gm was transferred into PAO1, and the putative tpx mutants that arose from the double crossover were selected for the Gmr and carbenicillin sensitivity (Cbs) phenotype. An unmarked Δtpx mutant was created using the cre-lox system to excise the Gmr gene as previously described (40), and deletion of tpx was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis.

The iscR mutant was constructed by insertional inactivation using pKNOCK, a suicide vector system (1). The 236-bp iscR (PA3815) fragment was amplified from the genomic DNA with the primers BT3186 (5′-TATCTCCGAACGCCAAGG-3′) and BT3187 (5′-GGTGGTGGGTCAGACAGG-3′). The PCR product was cloned into pKNOCK-Gm digested with SmaI, generating pKNOCK-iscR. This recombinant plasmid was introduced into E. coli BW20767 prior to being transferred into PAO1 by conjugation (1). The Gm-resistant transconjugants were selected and confirmed to be the iscR mutants by Southern analysis.

Construction of pTpx, pTpxC60S, pTpxC81S, pTpxC94S, and pIscR.

The full-length tpx gene was amplified from the PAO1 genome with the primers BT2647 (5′-GAAGGATCAACGCAATGG-3′) and BT2648 (5′-GGTCATGGGACGAAGCGG-3′). A 544-bp PCR product was cloned into the low-copy-number and broad-host-range vector pUFR047 (18) at the EcoRI and BamHI sites, yielding pTpx.

PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis was performed as previously described to generate mutant Tpx that has the conserved cysteine residue replaced with serine (45). The mutagenic forward primers and reverse primers used to generate the mutant Tpx were BT3411 (5′-CGACCTCCGCCACCTCGGTGCGCAA-3′) and BT3412 (5′-GTGGCGGAGGTCGGGGTGTCGACGC-3′) for C60S, BT3413 (5′-TGCTGTCCATCTCCGCCGACCTGCC-3′) and BT3414 (5′-GAGATGGACAGCACCACGGTGTTGG-3′) for C81S, and BT3415 (5′-GCTTCTCCGGCGCCGAAGGCCTGGA-3′) and BT3416 (5′-GCGCCGGAGAAGCGCTTCTGCGCGA-3′) for C94S. pTpx was used as a DNA template to allow PCR amplification with a mutagenic primer pair. PCR products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI and cloned into pUFR047 (18), which was then cut with the same enzymes. The resultant plasmids harboring inserted DNA were designated pTpxC60S, pTpxC81S, and pTpxC94S. The plasmids were sequenced to verify the accuracy of site-directed mutagenesis.

The full-length iscR gene was amplified from PAO1 genomic DNA with the primers BT3209 (5′-AAGAGCATAATCCGCGTC-3′) and BT3210 (5′-CGAGGTAGATCGGCAATT-3′). A 591-bp PCR product was cloned into expression vector pBBR1MCS4 (34) that had been digested with SmaI, generating pIscR.

Construction of the tpx-phoA and tpx-lacZ fusions.

The phoA and lacZ fusions were performed as previously described (52). A pTpx39-PhoA plasmid was constructed by in-frame fusion of the 5′-end fragment of tpx with a leaderless phoA from E. coli. The tpx fragment amplified from PAO1 genomic DNA with the primers BT3674 (5′-GCTTCTCACTGACTAGAA-3′) and BT3617 (5′-AGGGTACCAGGGTCACGTCGGCG-3′) was cut with KpnI before being cloned into pPhoA (52), whereas pBBR1MCS4 containing phoA was digested with SmaI and KpnI, generating pTpx39-PhoA.

pTpx39-LacZ was constructed by amplifying the tpx fragment with the BT3674 and BT3628 (5′-AGGGATCCAGGGTCACGTCGGCG-3′) primers using PAO1 genomic DNA as the template. The PCR product was cut with PstI prior to cloning into pLacZ (pBBR1MCS4 containing lacZ) and then digested with Acc65I (filled in with the Klenow fragment) and PstI, yielding pTpx39-LacZ.

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA isolation, agarose formaldehyde gel electrophoresis, blotting, and hybridization were performed as previously described (12). A 250-bp fragment of the tpx coding region amplified from pTpx using primers BT2647 (5′-GAAGGATCAACGCAATGG-3′) and BT2649 (5′-ACCACGGTGTTGGCCAGC-3′) was used as a radioactive probe. The labeling of the DNA probe with [α-32P]dCTP was performed using a DNA labeling bead (Amersham, GE Healthcare). Results from one representative experiment out of three independent experiments that were performed are shown. Densitometric analysis of the blot using ImageScanner III with LabScan 6.0 software (GE Healthcare) was performed to determine fold induction above the untreated level.

RT-PCR.

Endpoint reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was carried out as previously described (31) to determine the expression level of tpx in P. aeruginosa under exposure to oxidative stress. Total RNA samples were isolated from the exponential-phase cultures of PAO1 induced with 250 μM H2O2, CHP, menadione (MD), plumbagin (PB), or 100 μM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) for 20 min. The RT reaction was performed as described previously (31). After reverse transcription, the cDNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. The cDNA (100 ng) was used as a template for PCR amplification with primers specific to tpx, BT2647 (5′-GAAGGATCAACGCAATGG-3′) and BT2649 (5′-ACCACGGTGTTGGCCAGC-3′). The 16S rRNA gene was used as an internal control along with the primers BT2781 (5′-GCCCGCACAAGCGGTGGAG-3′) and BT2782 (5′-ACGTCATCCCCACCTTCCT-3′). To allow quantification within the linear range of the assay, PCR was performed under the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 20 s, 55°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s; this cycle was repeated 25 times for tpx and 22 times for the 16S rRNA.

Primer extension.

Total RNA was isolated from uninduced and PB-induced cultures. Primer extension was performed using [32P]-labeled BT3590 (5′-GCCTTTCTGCGGGAGCT-3′) primer, 20 μg of total RNA, and 200 U of Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The extension products were sized on a 6% acrylamide-7 M urea sequencing gel next to dideoxy sequencing ladders generated using a PCR sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems), with the labeled BT3590 primer and putative tpx promoter fragment used as the templates.

Purification of P. aeruginosa IscR and gel mobility shift assay.

His-tagged IscR from P. aeruginosa was purified using the pET-Blue2 expression system. The full-length iscR gene was amplified from PAO1 genomic DNA with primers EBI6 (5′-CGTCTGACCACCAAAGGCCGCTACGC-3′) and EBI7 (5′-CCGCTCGAGGTCGATGGCGGACGCTTCAATC-3′). A 495-bp PCR product was digested with XhoI before ligation into pET-Blue-2 digested NcoI (blunt ended) and XhoI to generate pET-iscR for high-level expression of IscR containing a C-terminal His6 tag. An E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS strain harboring pET-iscR was grown in LB medium containing 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin at 37°C to an OD600 of 1.0 before being induced with 1 mM IPTG for 15 min. IscR purification was carried out as previously described (43). The purity of IscR protein was more than 95% as judged by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Gel mobility shift assays were performed essentially as previously described (43). Briefly, a labeled probe (194 bp) containing the tpx promoter was prepared by amplifying PAO1 genomic DNA with 32P-labeled BT3712 (5′-TCGGGGGACGGCGATGCT-3′) and BT3590 primers. Binding reactions were conducted using 3 fmol of labeled probe in 25 μl of reaction buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.02 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 200 ng of poly(dI-dC). Various amounts of purified IscR were added, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 25°C for 20 min. Protein-DNA complexes were separated by electrophoresis on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 4°C and visualized by exposure to X-ray film.

Determination of oxidant resistance levels.

The resistance level of P. aeruginosa strains against low concentrations of oxidant was determined using the plate sensitivity assay (15). Serial dilutions of the exponential-phase cells were made in LB medium, and 10 μl of each dilution was spotted onto the LB agar plates alone or containing 0.5 mM H2O2, 1.5 mM CHP, 1.0 mM BHP, 1.0 mM diamide, 1.0 mM PB, or 0.5 mM PQ. The plates were incubated at 37°C overnight, and the bacterial colonies were counted. The resistance level was expressed as the surviving fraction, defined as the number of CFU on a plate containing oxidant divided by the number of CFU on a plate without oxidant.

The resistance level against lethal concentrations of H2O2 was determined as previously described (11), with some modifications. The exponential-phase cultures in LB medium were treated with 20 and 50 mM H2O2 for 30 min. Cells surviving the treatment were scored using viable cell counts by plating appropriate cell dilutions on LB agar plates and incubating them overnight at 37°C. The surviving fraction was defined as the ratio of CFU recovered after the treatment to the CFU existing prior to the treatment.

Enzyme activity assays.

Bacterial cell lysate preparation, protein assay, and catalase activity determination were performed as described previously (13). One unit of catalase was defined as the amount of enzyme capable of catalyzing the turnover of 1 μmol of substrate per min under assay conditions. Alkaline phosphatase activity was determined as described earlier (5). One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme capable of catalyzing 1 μmol of o-nitrophenol per min at room temperature. β-Galactosidase was assayed as described previously (41).

Nematode killing assays.

The pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa strains was determined using a Caenorhabditis elegans animal model (51). Both slow and fast killing experiments were performed as previously described (51). Nematodes in the fourth larval (L4) stage (30 to 40 animals per plate) were used in all experiments. Nematode killing was scored with a dissecting microscope after 3, 5, and 9 h for fast killing and 1, 2, 3, and 4 days for slow killing. Three biological replicates were carried out.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

P. aeruginosa Tpx belongs to the atypical 2-Cys peroxiredoxin class.

Analysis of the PAO1 genome (49) reveals the presence of an open reading frame, PA2532, encoding a thiol peroxidase (Tpx) homolog. This 165-amino-acid protein with a theoretical molecular mass of 17.23 kDa shares 66% sequence identity with E. coli Tpx, an atypical 2-Cys peroxiredoxin, and 60% identity with Mycobacterium tuberculosis Tpx (Fig. 1B). Analysis of the P. aeruginosa Tpx sequence using the SignalP 3.0 algorithm (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) and TatP 1.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TatP/) did not reveal a signal peptide. However, reanalysis of the protein for subcellular localization using PSORTb v3.0.2 (http://www.psort.org/psortb/) suggested that P. aeruginosa Tpx is a periplasmic enzyme similar to the previously described E. coli Tpx (9). To verify this in silico assumption experimentally, phoA and lacZ reporter gene fusions were used to determine the location of Tpx. The Tpx N-terminal fragment containing the first 39 codons of tpx was translationally fused either to alkaline phosphatase (PhoA), which is active only in the periplasm, where disulfide bonds are correctly formed, or to β-galactosidase (LacZ), which is active in the cytoplasm. PAO1 harboring pTpx39-PhoA that had an in-frame fusion of tpx39 to phoA and PAO1 carrying pPhoA, a plasmid expressing unfused phoA, produced an undetectable level of alkaline phosphatase activity. However, PAO1 harboring pTpx39-LacZ produced 5.86 ± 1.12 U mg−1 protein, whereas PAO1 harboring pLacZ (a plasmid expressing unfused lacZ) produced 0.11 ± 0.02 mU mg−1 protein. If Tpx was a typical periplasmic protein that was secreted from the cytosol via an N-terminal signal sequence, then we would expect a fusion to alkaline phosphatase to be active when expressed as a fusion to the first 39 amino acids of Tpx. Since we did not find any alkaline phosphatase activity in a strain expressing this fusion protein, we conclude that the protein is not secreted to the periplasm via a typical signal sequence, greatly decreasing the likelihood that this protein is located in the periplasm. Of note, a recent reanalysis of E. coli Tpx localization suggested that this protein also localizes to the cytoplasm (53).

Expression analysis of P. aeruginosa tpx.

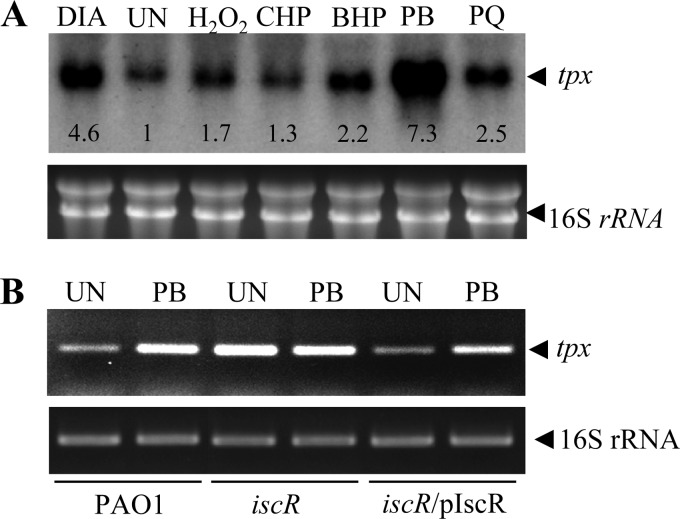

In P. aeruginosa, the expression of several genes encoding peroxide-scavenging enzymes, such as alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC), catalase, and Ohr (a thiol peroxidase), is inducible by peroxides (6, 41, 42). This adaptive expression in response to stress is a crucial general strategy for bacteria to survive under conditions of environmental stress, including oxidative stress. Previous observations have revealed contrasting tpx expression profiles. E. coli tpx is constitutively expressed and does not respond to treatments with peroxides, superoxide generators, or thiol-depleting agents (10). However, a proteomic analysis of Mycobacterium Tpx levels revealed increasing amounts of protein expression after exposure to thiol stress (19). Here, endpoint RT-PCR and Northern analysis were employed to determine the expression profile of P. aeruginosa tpx in response to oxidative stress. Exponential-phase PAO1 cells were treated with various oxidants for 15 min prior to RNA isolation. Northern analysis was performed using a tpx-specific probe labeled with [32P]dCTP. Exposure of the cultures to redox-cycling agents/superoxide generators, such as plumbagin (PB), paraquat (PQ), and the thiol-depleting agent diamide, substantially induced tpx expression by 7.3-, 2.5-, and 4.6-fold, respectively, as judged from densitometric analysis of the blot (Fig. 2A). Treatment of the cultures with either organic hydroperoxides (cumene hydroperoxide [CHP] or t-butyl hydroperoxide [BHP]) or H2O2 resulted in less tpx induction (1.3-fold for CHP, 2.2-fold for BHP, and 1.7-fold for H2O2). A similar pattern of tpx expression in response to oxidative stress was observed in the RT-PCR analysis (data not shown). The P. aeruginosa tpx expression profile revealed a novel pattern of oxidant-inducible gene expression that differs from other bacterial examples of tpx. In addition, the tpx expression pattern differs from that of other P. aeruginosa genes encoding peroxide-scavenging enzymes, such as ahpCF, katA, katB, gpx, and ohr (6, 27, 35, 41, 42). The expression of ahpCF, katA, and katB is regulated by the global H2O2-sensing regulator OxyR, while that of gpx and ohr is controlled by the repressors OspR and OhrR, respectively, both of which sense and respond to organic hydroperoxides (6, 27, 35, 41, 42). This unique expression pattern is unexpected, in that peroxide substrates of Tpx such as organic hydroperoxides are not strong inducers, whereas redox-cycling agents/superoxide generators and diamide, which are not substrates of the enzyme, act as strong inducers.

Fig 2.

Expression analysis of tpx. (A) Autoradiogram of a Northern blot analysis of tpx expression in an RNA sample extracted from exponential-phase PAO1 cells left untreated (UN) or treated with 0.25 mM H2O2, 0.5 mM cumene hydroperoxide (CHP), 0.5 mM t-butyl hydroperoxide (BHP), 0.5 mM plumbagin (PB), 0.25 mM paraquat (PQ), and 0.5 mM diamide (DIA) for 15 min. The number below each hybridized band represents the fold change in band intensity relative to the untreated culture. The RNA gel is shown below the autoradiogram to illustrate equal quantities of the RNA loaded. (B) The expression level of tpx in PAO1 strains was determined using endpoint RT-PCR. The exponential-phase cells of the PAO1 wild type, iscR mutant, and a complemented strain (iscR/pIscR) were treated with 0.25 mM PB for 15 min prior to RNA extraction. PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

tpx expression is regulated by IscR.

Numerous transcriptional regulators in P. aeruginosa, such as OxyR, SoxR, OhrR, OspR, MexR, and IscR, have been shown to be involved in the regulation of oxidative stress-inducible gene expression for a variety of genes (14, 23, 33, 35, 41, 44). These regulators are thought to be sensing and responding to different types of reactive oxygen species. The strong induction of tpx by superoxide generators/redox-cycling agents (Fig. 2A) suggests that OxyR, a peroxide sensor/transcriptional regulator, and/or transcription regulators containing the Fe-S cluster, such as SoxR or IscR, are involved in the regulation of the gene (32). Fe-S clusters containing transcriptional regulators are thought to be susceptible to oxidation by superoxide anions generated from redox-cycling drugs. In P. aeruginosa, SoxR has been shown not to be involved in the sensing of superoxide anions, and it has no role in the regulation of genes involved in the protection of superoxide stress. Nonetheless, RT-PCR analysis of tpx expression was performed on RNA samples from uninduced and plumbagin-induced wild-type PAO1 and oxyR and soxR mutants. RNA samples from oxyR and soxR mutants demonstrated plumbagin-inducible expression of tpx to levels similar to those attained in PAO1 samples (data not shown). This finding suggests that neither OxyR nor SoxR regulates plumbagin-inducible tpx expression.

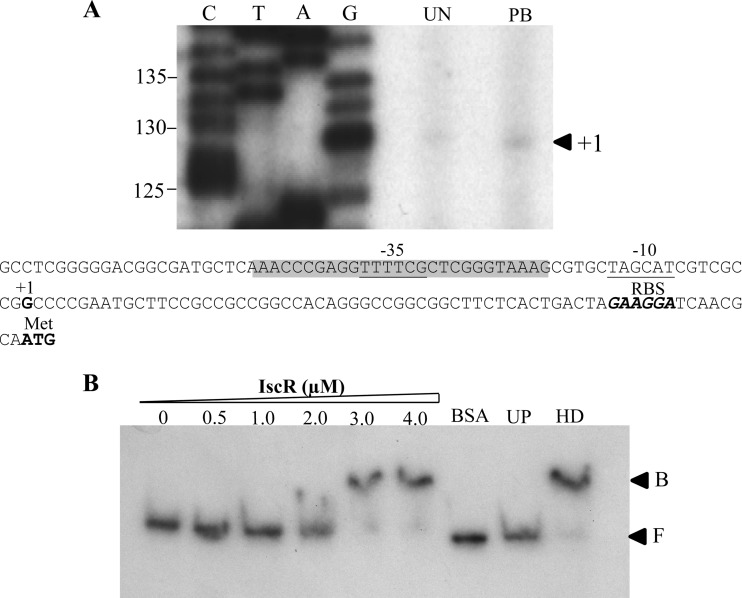

IscR is generally known as a transcriptional regulator of genes that participate in Fe-S cluster biogenesis. Experiments in P. aeruginosa PA14 have revealed a link between IscR regulation and KatA catalase, a gene that protects against oxidative stress (33). The iscR mutant shows reduced KatA activity and H2O2 hypersensitivity (33). IscR exerts its regulatory function by binding to the specific DNA sequence located in close proximity to the target gene promoters. Therefore, the putative tpx promoter was localized using the primer extension method.

Total RNA extracted from uninduced and PB-induced cultures was reverse transcribed using 32P-labeled BT3590 primer. The 129-base extension products mapped the transcriptional start site (+1) to the G residue located 66 bases upstream of the ATG translational start codon (Fig. 3A). The two conserved regions of the tpx promoter regions are TTTTCG and TAGCAT for the −35 and −10 regions, respectively, and are separated by 16 bp (Fig. 3A). As expected, no sequence similar to the consensus sequence for the E. coli SoxR binding site, 5′-CCTCAAGTTAACTTGAGG-3′ (28), could be identified in the region of the putative tpx promoter. This finding concurs with the tpx expression analysis in the soxR mutant. Interestingly, the sequence 5′-AAACCCGAGGTTTTCGCTCGGGTAAA-3′, which shares a high degree of homology (18 out of 26) with the consensus sequence for the E. coli IscR binding site 5′-AWARCCCYTSNGTTTGMNGKKKTKWA-3′ (22), was identified at positions −46 to −21 of the tpx promoter region. The presence of a putative IscR box in the promoter region of tpx suggests that IscR participates in transcriptional regulation of tpx gene expression. Thus, an iscR knockout mutant was constructed and used to monitor tpx expression. Northern blot analysis was performed using RNA samples prepared from uninduced and PB-induced iscR mutants, in addition to its complemented strain harboring pIscR plasmid (iscR/pIscR) and a PAO1 strain. As expected, PB-treated PAO1 showed a 6.5-fold induction in tpx expression based on densitometric analysis. The PB induction of tpx expression was abolished in the iscR mutant. The tpx expression showed constitutively high expression levels in the iscR mutant. The uninduced level of tpx transcripts in the iscR mutant was 10.5-fold higher than the uninduced level in PAO1 and 1.4-fold higher than the levels attained in the PB-induced sample from PAO1 (Fig. 2B). In the iscR/pIscR strain, the uninduced tpx transcript level was 0.7-fold lower than the uninduced level in the PAO1 strain. As expected, the exposure to PB induced a 2.5-fold increase in the tpx transcription level. PB-induced tpx expression was restored in the complemented mutant strain.

Fig 3.

Analysis of the tpx promoter. (A) Primer extension was carried out using the 32P-labeled BT3590 primer and RNA extracted from the PAO1 wild type, iscR mutant, and a complemented strain (iscR/pIscR) either uninduced (UN) or induced with 0.25 mM plumbagin (PB). C, T, A, and G represent the DNA sequence ladders prepared using a labeled primer identical to that used in primer extension and a tpx promoter fragment as the template. Numbers at the left indicate fragment lengths in base pairs. The arrowhead indicates the transcription start site (+1). Putative −35 and −10 motifs are underlined, and the ribosome binding site (Rbs) is in boldface and italics. Nucleotides that match the E. coli consensus sequence for the IscR binding box are shaded. The conserved bases are indicated by asterisks. The boldfaced ATG represents the translational initiation codon. (B) Gel mobility shift assay of reaction mixtures containing 32P-labeled tpx promoter fragment and the indicated concentrations of purified IscR. UP and HD represent the binding reaction mixtures containing 3.0 μM IscR and an additional 1 μg of unlabeled tpx promoter and 2.5 μg of heterologous DNA (pUC28 plasmid), respectively. F and B indicate free and bound probes, respectively.

In other bacteria, IscR has been shown to function as a transcriptional repressor or activator, depending on the binding site and the form of transcription regulator that binds to the operator. Here, tpx expression patterns in PAO1 and in the iscR mutant indicate that IscR functions as a transcription repressor on the tpx promoter. This notion is supported by observations that tpx expression is constitutively high in the iscR mutant and the documented decrease in the uninduced tpx expression levels when large amounts of IscR were produced from an expression plasmid in the iscR-complemented strain. One possible mechanism for IscR regulation of tpx expression is that, in uninduced conditions, the IscR binding site overlaps with the tpx promoter regions. This situation would prevent RNA polymerase from binding to the promoter and would result in repression of gene transcription. The 2Fe-2S center of IscR is known to be highly susceptible to oxidation by oxidants, i.e., redox-cycling drugs/superoxide generators and thiol-depleting reagents and peroxides (17, 38, 47, 54). Thus, with exposure to redox-cycling drugs/superoxide anions, such as PB, the 2Fe-2S center of IscR is likely to be oxidized, leading to disruption of the 2Fe-2S and a possible change in IscR conformation, thus rendering the regulator unable to bind to the operator site of the tpx promoter. This situation would allow RNA polymerase to bind to the promoter and enable full expression of the gene. To definitively prove this model, a gel mobility shift assay was performed using purified His-tagged IscR protein. Purified IscR specifically bound to the tpx promoter fragment (Fig. 3B). The binding specificity of IscR was illustrated by the ability of the unlabeled tpx promoter fragment, but not an excess of heterologous DNA (pUC18 plasmid), to compete with IscR for binding to the labeled promoter fragment, and the presence of an excess amount of unrelated protein (2.5 μg BSA) failed to enable binding to the tpx promoter (Fig. 3B). Thus, IscR directly binds the tpx promoter and regulates its expression.

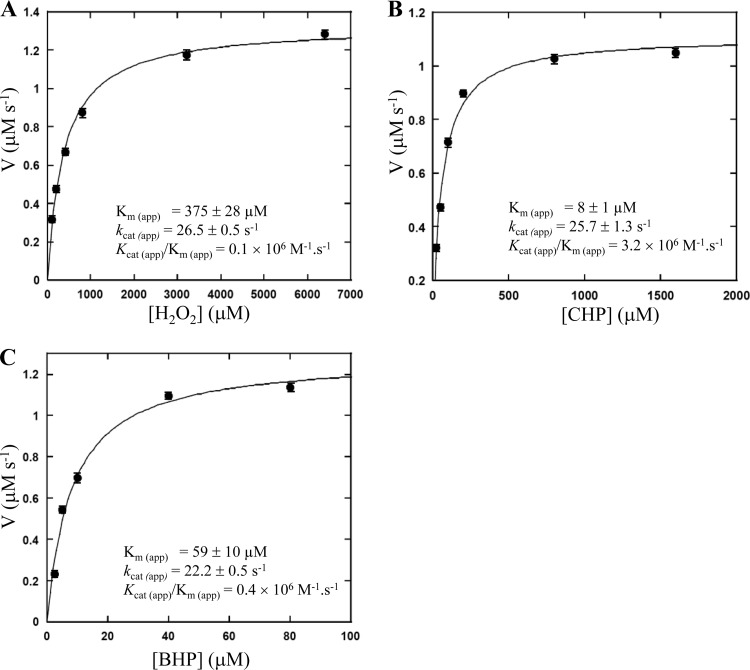

Biochemical properties of P. aeruginosa Tpx.

As a member of the peroxiredoxin enzyme family, Tpx uses reducing equivalents from the thioredoxin (TrxA)/thioredoxin reductase (TrxB) system to reduce peroxides (4). The peroxidase activity of P. aeruginosa Tpx was measured by coupling the Tpx reaction with the TrxA/TrxB system in which TrxB catalyzes the reduction of TrxA by NADPH (4). The His-tagged P. aeruginosa Tpx, TrxA (PA5240), and His-tagged TrxB (PA2616) proteins were purified using the E. coli expression system (see Materials and Methods). The oxidation of NADPH to NADP+ was monitored by the absorbance decrease at 340 nm. The results showed that H2O2 and organic hydroperoxides (CHP and BHP) can be used as enzyme substrates. The apparent kinetic parameters, including the Michaelis constant [Km (app)], turnover number [kcat (app)], and catalytic efficiency [kcat (app)/Km (app)], were determined for each peroxide substrate and are shown in Fig. 4. The Km (app) values of the P. aeruginosa Tpx for H2O2, CHP, and BHP (determined at 100 μM TrxA) were 375 ± 28, 8 ± 1, and 59 ± 10 μM, respectively, and the kcat (app) values were 26.6 ± 0.5, 25.7 ± 1.3, and 22.2 ± 0.5 s−1, respectively. Therefore, these data indicate that P. aeruginosa Tpx is more efficient at reducing organic hydroperoxides [CHP and BHP, with kcat (app)/Km (app) of 3.2 × 106 and 4 × 105 M−1 · s−1, respectively] than H2O2 [with kcat (app)/Km (app) of 1 × 105 M−1 · s−1]. Clearly, Tpx can use both organic hydroperoxides and H2O2 as substrates, albeit with different efficiencies. In this respect, P. aeruginosa Tpx and E. coli Tpx are similar, in that their Kms for organic peroxide substrates are lower than that of H2O2 (3). Interestingly, the results of Fig. 4 show similar turnover numbers for all peroxides, implying that the binding or reaction of peroxide with the enzyme is not the rate-limiting step in the overall reaction. When the assays were carried out in the absence of either TrxA or TrxB, no oxidation of NADPH to NADP+ occurred, confirming that P. aeruginosa Tpx is a thioredoxin-dependent peroxidase.

Fig 4.

Michaelis-Menten plots of P. aeruginosa Tpx activity versus peroxide substrates. The reaction mixtures contain 100 μM TrxA, 1.5 μM TrxB, 150 μM NADPH, 0.05 μM Tpx, and indicated concentrations of H2O2 (A), cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) (B), or t-butyl hydroperoxide (BHP) (C). The Km (app), kcat (app), and kcat (app)/Km (app) values were calculated using KaleidaGraph.

Physiological functions of P. aeruginosa tpx.

The physiological role of tpx in P. aeruginosa PAO1 was evaluated using a Δtpx mutant. The resistance levels against peroxides, including CHP (1.5 mM), BHP (1.0 mM), and H2O2 (0.5 mM), and superoxide generators of the mutant, including PB (1.0 mM) and PQ (0.5 mM), were determined using the plate sensitivity assay and were compared to the PAO1 wild type. No significant differences in the resistance levels against organic hydroperoxides (CHP and BHP) and PB between the Δtpx mutant and the PAO1 wild type were observed (data not shown). This finding is quite unexpected, because purified P. aeruginosa Tpx showed high catalytic efficiency for organic hydroperoxides, particularly for CHP. This point raises the question of whether Tpx functions as an organic hydroperoxide thiol peroxidase in vivo. P. aeruginosa has evolved multiple systems to efficiently detoxify organic hydroperoxides (41, 42). It produces four organic hydroperoxide reductase enzymes, AhpA, AhpB, AhpCF, and Ohr. Thus, the absence of Tpx alone has no obvious effect on the bacterium's ability to detoxify organic hydroperoxides. Moreover, the resistance levels of the Δtpx mutant against redox-cycling drugs/superoxide-generating substances (plumbagin and paraquat) were comparable to the corresponding levels in PAO1 (data not shown).

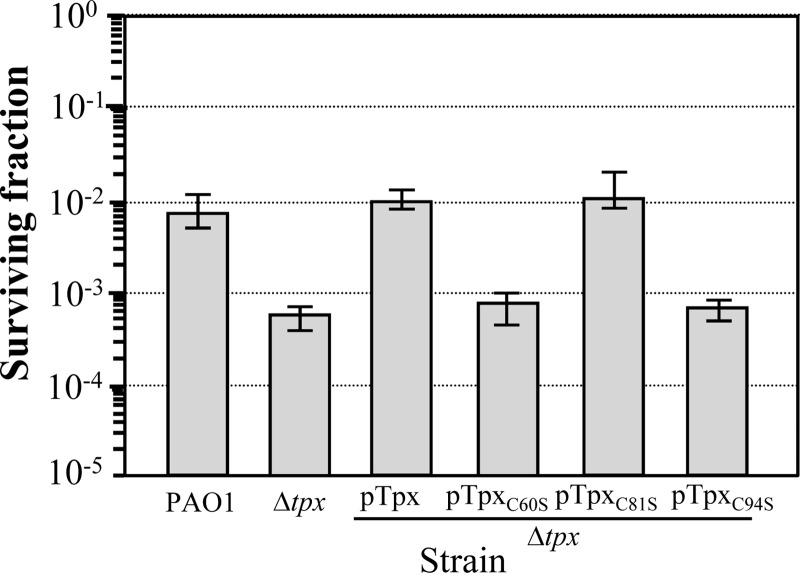

In many bacteria, the tpx mutant has decreased resistance to H2O2 (8, 16, 30). Hence, the resistance to moderate (0.5 mM) and high (20 and 50 mM) concentrations of H2O2 in the Δtpx mutant and in the PAO1 wild type were determined. The Δtpx mutant was more than 10-fold more sensitive to 0.5 mM H2O2 than the PAO1 wild type (Fig. 5). This altered phenotype could be complemented in the Δtpx mutant carrying pTrxA for trans-expression of tpx from the pUFR047 plasmid (18). Surprisingly, when the Δtpx mutant and PAO1 wild type were treated with lethal concentrations of H2O2 (20 and 50 mM) for 30 min and surviving cells were scored using viable cell counts, no significant changes in the resistance levels against H2O2 were observed (data not shown). In general, P. aeruginosa has redundant systems to scavenge H2O2 generated within cells or from exogenous sources. It produces several isozymes of catalases and peroxiredoxins that are capable of degrading H2O2 (2, 24, 39, 42). Total catalase activity in the Δtpx mutant and in the parental PAO1 wild type were measured to test whether the H2O2-sensitive phenotype of the Δtpx mutant arose from changes in the total catalase activity levels. The total catalase activity of the Δtpx mutant was 347.3 ± 8.5 U mg−1 protein, and that for the PAO1 wild type was 356.1 ± 16.7 U mg−1. Thus, the H2O2-sensitive phenotype of the Δtpx mutant was not due to a lowering of total catalase activity. Based on currently available data, P. aeruginosa possesses three different monofunctional catalases, namely, KatA, KatB, and KatE (37, 39, 42), but lacks a homolog of a bifunctional catalase-peroxidase (KatG) (49). Monofunctional catalases typically have relatively high apparent Km values for the reduction of H2O2 (38 to 200 mM) compared to bifunctional catalase-peroxidases (∼5 mM) (48, 50). Interestingly, our data indicate that the Km (app) for H2O2 of Tpx is much lower than the Km for H2O2 of catalases (Fig. 4). For many metabolic enzymes, Km values are similar to in vivo concentrations of substrates. It can be envisaged that Tpx is the main enzyme that defends against H2O2 at ∼0.5 mM because its Km value is in this range. This notion is also supported by the finding that the Δtpx mutant is only sensitive to 0.5 mM H2O2 and not to 20 or 50 mM concentrations (Fig. 5 and data not shown). Our data suggest that Tpx plays a disparate role in the protection of P. aeruginosa against H2O2. Tpx may offer protection against submillimolar levels of H2O2 in P. aeruginosa, whereas other systems, such as catalases, may play a role at higher mM concentrations. The question remains as to why, if tpx is important in H2O2 protection, the mutation results in only a small reduction in the peroxide resistance level. The small reduction in the resistance level to 0.5 mM H2O2 in the tpx mutant (10-fold) is most likely due to the presence of multiple P. aeruginosa alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) enzymes which have lower Km values for H2O2 than for catalases. These AhpC enzymes contribute to the protection of the bacteria against lower concentrations of H2O2. The results clearly show that P. aeruginosa Tpx has a novel physiological role in H2O2 protection that has not been observed in other bacteria.

Fig 5.

Functional analysis of tpx in P. aeruginosa. The resistance level of the PAO1 wild type, Δtpx mutant, or the mutants harboring pTpx, pTpxC60S, pTpxC81S, or pTpxC94S was determined using a plate sensitivity assay in the presence of 0.5 mM H2O2. The surviving fraction was calculated by counting the CFU on the LB plates containing H2O2 divided by the CFU on the LB plates without H2O2. Error bars indicate the means ± SD from three independently performed experiments.

Tpx has been shown to contribute to the pathogenicity of some bacteria. In P. aeruginosa PAO1, Tpx may provide the first line of defense against host-generated peroxides. Thus, the effect of tpx inactivation on the pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa was assessed using the C. elegans nematode model (51). Fast killing of C. elegans is believed to be based on cyanide poisoning, which leads to inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase, while slow killing requires proliferation of live bacteria in the worm gut (21, 51). We found that the percent survival of nematodes fed the Δtpx mutant under both fast-killing and slow-killing conditions was not significantly different from that of nematodes fed the PAO1 wild-type strain at all time points (data not shown). The results suggest that tpx was not required for P. aeruginosa pathogenicity when C. elegans was used as an animal model.

Role of conserved cysteine residues in Tpx.

P. aeruginosa Tpx contains three cysteine residues at positions Cys-60, Cys-81, and Cys-94. The importance of these three cysteine residues in terms of H2O2 detoxification was evaluated through single-site-directed mutagenesis to replace Cys-60, Cys-81, and Cys-94 with serine residues. The mutated tpxC60S, tpxC81S, and tpxC94S genes were cloned into the broad-host-range expression vector pUFR047, yielding pTpxC60S, pTpxC81S, and pTpxC94S, respectively. The ability of these recombinant plasmids to complement the H2O2-sensitive phenotype of the P. aeruginosa Δtpx mutant was tested. The expression of tpxC81S was able to complement the phenotype of the Δtpx mutant to a level similar to that of wild-type tpx complementation, whereas tpxC60S and tpxC94S failed to increase the H2O2 resistance level of the Δtpx mutant (Fig. 5). Thus, P. aeruginosa Tpx is a 2-Cys peroxiredoxin that requires Cys-60 and Cys-94 residues for its function as an H2O2 scavenger. However, we cannot rule out that a change in protein stability resulting from a point mutation occurred.

P. aeruginosa Tpx Cys-60 and Cys-94 correspond to Cys-61 and Cys-95 in the E. coli Tpx, which function as peroxidatic and resolving cysteines, respectively (3). The enzyme catalyzes the reduction of peroxide, which first entails oxidation of the thiol group of the peroxidatic cysteine, which then reacts with the thiol group of the resolving cysteine located within the same polypeptide, thereby forming an intramolecular disulfide bond (3).

Conclusion.

We present here the gene regulation, biochemical properties, and physiological roles of a P. aeruginosa antioxidant enzyme, Tpx. The presented data suggest that tpx is a novel member of the IscR regulon whose expression was induced in response to thiol-depleting agents and redox-cycling drugs. Cytoplasmic Tpx has thiol-dependent peroxidase activity with higher substrate affinity for organic hydroperoxides than for H2O2. Phenotypic analysis of the tpx mutant reveals differential patterns of H2O2 sensitivity with different H2O2 concentrations. The mutant is sensitive to submillimolar but not millimolar concentrations of H2O2. Incidentally, this sensitivity to submillimolar concentrations of H2O2 is in the range of the Km value of Tpx for H2O2. It is likely that Tpx offers a major defense against H2O2 in the submillimolar but not the millimolar range. Based on the C. elegans results, Tpx does not contribute to the virulence of P. aeruginosa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was supported by grants from Mahidol University and the Center of Excellence on Environmental Health and Toxicology, Science & Technology Postgraduate Education and Research Development Office, Ministry of Education. N.S. and A.R. were supported by Golden Jubilee scholarships from the Thailand Research Fund.

We thank Kittipat Sopitthummakhun for technical assistance and James M. Dubbs for critical reading of the revised manuscript.

Parts of this work are from the dissertation of N.S. submitted for a Ph.D. degree from Mahidol University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 May 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Alexeyev MF. 1999. The pKNOCK series of broad-host-range mobilizable suicide vectors for gene knockout and targeted DNA insertion into the chromosome of gram-negative bacteria. Biotechniques 26:824–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. An BC, et al. 2010. A new antioxidant with dual functions as a peroxidase and chaperone in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Cells 29:145–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker LM, Poole LB. 2003. Catalytic mechanism of thiol peroxidase from Escherichia coli. Sulfenic acid formation and overoxidation of essential CYS61. J. Biol. Chem. 278:9203–9211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker LM, Raudonikiene A, Hoffman PS, Poole LB. 2001. Essential thioredoxin-dependent peroxiredoxin system from Helicobacter pylori: genetic and kinetic characterization. J. Bacteriol. 183:1961–1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brickman E, Beckwith J. 1975. Analysis of the regulation of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase synthesis using deletions and phi80 transducing phages. J. Mol. Biol. 96:307–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown SM, Howell ML, Vasil ML, Anderson AJ, Hassett DJ. 1995. Cloning and characterization of the katB gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encoding a hydrogen peroxide-inducible catalase: purification of KatB, cellular localization, and demonstration that it is essential for optimal resistance to hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 177:6536–6544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caselli D, et al. 2010. Multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in children undergoing chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica 95:1612–1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cha MK, Kim HK, Kim IH. 1996. Mutation and mutagenesis of thiol peroxidase of Escherichia coli and a new type of thiol peroxidase family. J. Bacteriol. 178:5610–5614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cha MK, Kim HK, Kim IH. 1995. Thioredoxin-linked “thiol peroxidase” from periplasmic space of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 270:28635–28641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cha MK, Kim WC, Lim CJ, Kim K, Kim IH. 2004. Escherichia coli periplasmic thiol peroxidase acts as lipid hydroperoxide peroxidase and the principal antioxidative function during anaerobic growth. J. Biol. Chem. 279:8769–8778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Charoenlap N, et al. 2011. Evaluation of the virulence of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris mutant strains lacking functional genes in the OxyR regulon. Curr. Microbiol. 63:232–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Charoenlap N, et al. 2005. OxyR mediated compensatory expression between ahpC and katA and the significance of ahpC in protection from hydrogen peroxide in Xanthomonas campestris. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 249:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chauvatcharin N, et al. 2005. Genetic and physiological analysis of the major OxyR-regulated katA from Xanthomonas campestris pv. phaseoli. Microbiology 151:597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen H, et al. 2010. Structural insight into the oxidation-sensing mechanism of the antibiotic resistance of regulator MexR. EMBO Rep. 11:685–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chuchue T, et al. 2006. ohrR and ohr are the primary sensor/regulator and protective genes against organic hydroperoxide stress in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 188:842–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Comtois SL, Gidley MD, Kelly DJ. 2003. Role of the thioredoxin system and the thiol-peroxidases Tpx and Bcp in mediating resistance to oxidative and nitrosative stress in Helicobacter pylori. Microbiology 149:121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. D'Autreaux B, Toledano MB. 2007. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:813–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DeFeyter R, Kado CI, Gabriel DW. 1990. Small, stable shuttle vectors for use in Xanthomonas. Gene 88:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dosanjh NS, Rawat M, Chung JH, Av-Gay Y. 2005. Thiol specific oxidative stress response in Mycobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 249:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dubbs JM, Mongkolsuk S. 2007. Peroxiredoxins in bacterial antioxidant defense. Subcell. Biochem. 44:143–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gallagher LA, Manoil C. 2001. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 kills Caenorhabditis elegans by cyanide poisoning. J. Bacteriol. 183:6207–6214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Giel JL, Rodionov D, Liu M, Blattner FR, Kiley PJ. 2006. IscR-dependent gene expression links iron-sulphur cluster assembly to the control of O2-regulated genes in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 60:1058–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ha U, Jin S. 1999. Expression of the soxR gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is inducible during infection of burn wounds in mice and is required to cause efficient bacteremia. Infect. Immun. 67:5324–5331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hassett DJ, et al. 2000. A protease-resistant catalase, KatA, released upon cell lysis during stationary phase is essential for aerobic survival of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa oxyR mutant at low cell densities. J. Bacteriol. 182:4557–4563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hassett DJ, Schweizer HP, Ohman DE. 1995. Pseudomonas aeruginosa sodA and sodB mutants defective in manganese- and iron-cofactored superoxide dismutase activity demonstrate the importance of the iron-cofactored form in aerobic metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 177:6330–6337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hawdon NA, et al. 2010. Cellular responses of A549 alveolar epithelial cells to serially collected Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients at different stages of pulmonary infection. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 59:207–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heo YJ, et al. 2010. The major catalase gene (katA) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 is under both positive and negative control of the global transactivator OxyR in response to hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 192:381–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hidalgo E, Leautaud V, Demple B. 1998. The redox-regulated SoxR protein acts from a single DNA site as a repressor and an allosteric activator. EMBO J. 17:2629–2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jaeger T, et al. 2004. Multiple thioredoxin-mediated routes to detoxify hydroperoxides in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 423:182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jakubovics NS, Smith AW, Jenkinson HF. 2002. Oxidative stress tolerance is manganese (Mn2+) regulated in Streptococcus gordonii. Microbiology 148:3255–3263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jittawuttipoka T, Sallabhan R, Vattanaviboon P, Fuangthong M, Mongkolsuk S. 2010. Mutations of ferric uptake regulator (fur) impair iron homeostasis, growth, oxidative stress survival, and virulence of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Arch. Microbiol. 192:331–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kiley PJ, Beinert H. 2003. The role of Fe-S proteins in sensing and regulation in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim SH, Lee BY, Lau GW, Cho YH. 2009. IscR modulates catalase A (KatA) activity, peroxide resistance and full virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 19:1520–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kovach ME, et al. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lan L, Murray TS, Kazmierczak BI, He C. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa OspR is an oxidative stress sensing regulator that affects pigment production, antibiotic resistance and dissemination during infection. Mol. Microbiol. 75:76–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Larkin MA, et al. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee JS, Heo YJ, Lee JK, Cho YH. 2005. KatA, the major catalase, is critical for osmoprotection and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. Infect. Immun. 73:4399–4403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee KC, Yeo WS, Roe JH. 2008. Oxidant-responsive induction of the suf operon, encoding a Fe-S assembly system, through Fur and IscR in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 190:8244–8247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ma JF, et al. 1999. Bacterioferritin A modulates catalase A (KatA) activity and resistance to hydrogen peroxide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 181:3730–3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marx CJ, Lidstrom ME. 2002. Broad-host-range cre-lox system for antibiotic marker recycling in gram-negative bacteria. Biotechniques 33:1062–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ochsner UA, Hassett DJ, Vasil ML. 2001. Genetic and physiological characterization of ohr, encoding a protein involved in organic hydroperoxide resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183:773–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ochsner UA, Vasil ML, Alsabbagh E, Parvatiyar K, Hassett DJ. 2000. Role of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa oxyR-recG operon in oxidative stress defense and DNA repair: OxyR-dependent regulation of katB-ankB, ahpB, and ahpC-ahpF. J. Bacteriol. 182:4533–4544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Otsuka Y, et al. 2010. IscR regulates RNase LS activity by repressing rnlA transcription. Genetics 185:823–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Panmanee W, Hassett DJ. 2009. Differential roles of OxyR-controlled antioxidant enzymes alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpCF) and catalase (KatB) in the protection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa against hydrogen peroxide in biofilm vs. planktonic culture. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 295:238–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Panmanee W, et al. 2002. OhrR, a transcription repressor that senses and responds to changes in organic peroxide levels in Xanthomonas campestris pv. phaseoli. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1647–1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rho BS, et al. 2006. Functional and structural characterization of a thiol peroxidase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Mol. Biol. 361:850–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schwartz CJ, et al. 2001. IscR, an Fe-S cluster-containing transcription factor, represses expression of Escherichia coli genes encoding Fe-S cluster assembly proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:14895–14900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Singh R, et al. 2008. Comparative study of catalase-peroxidases (KatGs). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 471:207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stover CK, et al. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Switala J, Loewen PC. 2002. Diversity of properties among catalases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 401:145–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tan MW, Mahajan-Miklos S, Ausubel FM. 1999. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa used to model mammalian bacterial pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:715–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tanboon W, Chuchue T, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. 2009. Inactivation of thioredoxin-like gene alters oxidative stress resistance and reduces cytochrome c oxidase activity in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 295:110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tao K. 2008. Subcellular localization and in vivo oxidation-reduction kinetics of thiol peroxidase in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 289:41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yeo WS, Lee JH, Lee KC, Roe JH. 2006. IscR acts as an activator in response to oxidative stress for the suf operon encoding Fe-S assembly proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 61:206–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]