Abstract

Opioid neuropeptide receptors mediate diverse physiological functions and are important targets for both therapeutic and abused drugs. Opioid receptors are highly regulated in intact cells, and there is reason to believe that this regulation controls the clinical effects of opioid drugs. The present review will discuss some of this evidence, focusing specifically on the regulation of opioid receptors by endocytic membrane trafficking mechanisms. First, some basic principles of regulated endocytosis will be reviewed, and the principle of ‘molecular sorting’ as a means to determine the functional consequences of endocytosis will be introduced, Most of this information has been derived from studies of simplified cell models. Second, present knowledge about the operation of these mechanisms in physiologically relevant CNS neurons will be discussed, focusing on studies of neurons cultured from rodent brain. Third, recent insight into the effects of endocytic trafficking on opioid regulation in vivo will be considered, focusing on results from studies of transgenic mouse models. Much remains to be learned at these pre-clinical levels, and effects of endocytosis on opioid actions in humans remain completely unexplored. Two particular insights, which have emerged from preclinical studies, will be proposed for translational consideration.

Keywords: Opioid, endocytosis, adaptation, cellular models, membrane trafficking, desensitization, resensitization, downregulation

1. Opioids and cellular hypotheses of addictive drug action

Opioid research is arguably where the cellular approach to addictive drug action began. Seminal observations by Nirenberg and colleagues identified biochemical adaptation of opioid-dependent regulation of cellular cyclic AMP levels in a neuroblastoma-glioma tissue culture cell line (NG108-15 cells), and boldly proposed that adaptations of opioid receptors and downstream signaling biochemistry mediate cellular correlates of both opioid tolerance and dependence (Sharma et al., 1977). Studies of prolonged opioid effects on the isolated guinea pig ileum, a classic opioid-responsive ex vivo system, led Chavkin and Goldstein to propose that opioid tolerance resulted from a net decrease in ‘receptor reserve’ - a pharmacological estimate of the number of functional opioid receptors- in individual neurons of a native preparation (Chavkin and Goldstein, 1982). Law and Loh described down-regulation of opioid receptor number in NG108-15 cells following chronic enkephalin exposure (Law et al., 1982). These and other important early studies ushered in the idea that opioid addiction is associated with regulatory processes affecting opioid receptors and downstream signaling machinery and occurs, in part, at the level of individual opioid-responsive neurons.

The molecular cloning of opioid receptors, first accomplished by the groups of Evans and Kieffer (Evans et al., 1992; Kieffer et al., 1992), established definitively that opioid receptors are members of the large family of seven-transmembrane G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) related to rhodopsin and the β-adrenergic receptor. This important step brought to the opioid field, which already was an area of sophisticated physiological and pharmacological analysis, powerful new tools of molecular and cell biological analysis.

2. A play in three acts

Considerable progress has been made in recent years elucidating specific cellular mechanisms of opioid regulation in isolated cells, to the point that a number of the seminal early observations can now be explained in detail. More recent studies have identified new, and previously unanticipated, aspects of opioid receptor function and regulation that may be of translational importance. A current challenge in the field is to analyze specific opioid regulatory mechanisms as they occur in the intact CNS, and to understand the functional significance of specific mechanisms of cellular regulation.

The particular focus of the present review is on the regulation of opioid receptors by endocytosis. This aspect of opioid regulation, while it represents only a subset of the many cellular processes regulated by opioids, is intimately connected to opioid receptor function and may have already identified new targets for potential therapeutic manipulation.

The following review is organized into three sections. First, progress in elucidating fundamental mechanisms of regulated receptor trafficking will be discussed. This information is derived mostly from experiments using simplified cell culture model systems, and from biochemical analysis of cell-free preparations. Second, progress toward understanding regulated endocytic trafficking of opioid receptors in relevant neurons will be reviewed. This is based largely on study of cultured neurons and ex vivo neural preparations. Third, recent and ongoing efforts to elucidate opioid receptor trafficking and functional consequences in intact animal models will be discussed.

3. Regulated endocytic trafficking of opioid receptors in simplified cell models

3.1 Endocytosis linked to functional desensitization: Evidence for agonist-selective and receptor-specific regulation of opioid receptors

The hypothesis that opioid receptors can lose signaling effectiveness and undergo physical removal from the plasma membrane was suggested by early studies, as noted above, primarily using the tools of radioligand binding and subcellular fractionation. These observations, together with observations from the Evans and Barchas laboratories indicating that chemically distinct opiate drugs can differentially regulate the number and pharmacological properties of surface-accessible opioid receptors detected in intact NG108-15 cells (Evans and von Zastrow, 1990; von Zastrow et al., 1993), motivated mechanistic studies into opioid receptor endocytosis and how various structurally distinct peptide and non-peptide opioids differ in their regulatory effects. This set in motion efforts to explore the biochemical basis for so-called agonist-selectiveregulation of opioid receptors.

Beginning with studies of the δ opioid receptor, and then extending to the cloned μ opioid receptor, regulated endocytosis of opioid receptors expressed in a non-neural cultured cell system (human embryonal kidney 293 cells) was found to be mediated primarily by clathrin-coated pits. This is a highly conserved mechanism by which many types of membrane protein can be rapidly internalized (Conner and Schmid, 2003; Keith et al., 1996; von Zastrow et al., 1994).

The remarkable similarity between opioid and adrenergic receptor endocytosis, and the identification of non-visual (or β-) arrestins as regulated adaptors to promote adrenergic receptor association with coated pits (Ferguson et al., 1996; Goodman et al., 1996), led quickly to the realization that arrestins (particularly arrestin 3 or β-arrestin-2) promote rapid endocytosis of opioid receptors as well. They also revealed that opioid drugs such as morphine can, under some conditions, activate G protein-mediated signaling quite strongly while producing little stimulation of the arrestin-dependent endocytic mechanism (Whistler and von Zastrow, 1998).

GPCR interaction with arrestins is typically promoted not only by a ligand-induced conformational state of the receptor but by receptor phosphorylation catalyzed by a particular class of protein kinases, the GPCR kinases (GRKs), which selectively recognize ligand-activated receptors (Benovic et al., 1986; Freedman and Lefkowitz, 1996). It was shown that manipulating GRK levels in cultured cells could markedly enhance the ability of morphine to promote rapid endocytosis of receptors (Zhang et al., 1998). This requirement of both GRKs and arrestins for promoting the rapid endocytic mechanism revealed a remarkable interrelationship between receptor endocytosis and signaling, as the GRK/arrestin system also mediates functional desensitization of various GPCRs including opioid receptors (Kovoor et al., 1999), essentially by preventing receptors from coupling to trimeric G proteins (Gurevich and Benovic, 1997).

While both μ and δ opioid receptors were found to internalize within several minutes in response to opioid peptide agonists and the relatively non-selective alkaloid agonist etorphine, cloned κ opioid receptors internalized relatively slowly when activated by the same agonist (Chu et al., 1997). It was then found that κ receptors can internalize more rapidly when activated by other agonists, consistent with agonist-selective regulation of this opioid receptor as well, and the existence of significant species-specific differences in regulated endocytosis was established by comparison of human and rodent -derived receptors expressed in the same cellular background (Li et al., 1999).

3.2 Agonist-selective endocytosis as an early example of the emerging concept of ‘functional selectivity’ or ‘biased agonism’

The finding that certain opioid drugs could effectively activate G protein-mediated signaling by opioid receptors without strongly promoting regulated endocytosis raised an interesting mechanistic question: How could different ligands, thought traditionally to function as molecular ‘mimics’ by binding to the same receptor, selectively instruct the receptor to do different things? One possibility is that, because G protein-linked signaling can typically occur with only a small fraction of receptors, the relative inability of some opioids to promote endocytosis (which is thought to require receptor occupancy) could simply reflect a difference in agonist potency. Quantitative comparison of a panel of opioids applied at saturating concentration argued that this is an unlikely explanation (Keith et al., 1998). An alternative possibility is that the observed differences in receptor endocytosis reflect differences in the ability of opioids, once bound, to promote receptor activation. Differences among opioids in this property of relative agonist ‘efficacy’ were long recognized based on biochemical studies of G protein activation (Costa et al., 1992).

The new question raised by the endocytosis data was whether opioids with distinct effects on GRK/arrestin/clathrin dependent regulation differ only in the degree to which they produce the same activated receptor state, as predicted by the traditional concept of agonist efficacy (Kenakin, 2004), or if they differ in ability to promote the formation of distinct activated receptor states. Data supporting both hypotheses have been reported, and agreement on this issue has not yet been achieved (Borgland et al., 2003; Keith et al., 1998; Kovoor et al., 1998; Whistler et al., 1999; Williams et al., 2001). Nevertheless, there is increasingly widespread acceptance of the idea that the complex regulatory effects of opioids cannot be fully explained by the traditional view of agonist efficacy as a ‘uni-dimensional’ parameter. Instead, it is thought that opioid drugs exhibit something that might be called ‘multi-dimensional’ efficacy. A simple hypothesis is that chemically distinct drugs could selectively stabilize different receptor conformations that result in different functional effects. This is the basis of the concept of ‘functional selectivity’ or ‘biased agonism’ that is increasingly thought to be relevant to the effects of many GPCRs (Urban et al., 2007; Kenakin, 2007). Such multi-dimensionality of agonist efficacy has potentially profound translational implications (Galandrin et al., 2007; Kenakin, 2009).

3.3 Molecular sorting of opioid receptors after endocytosis

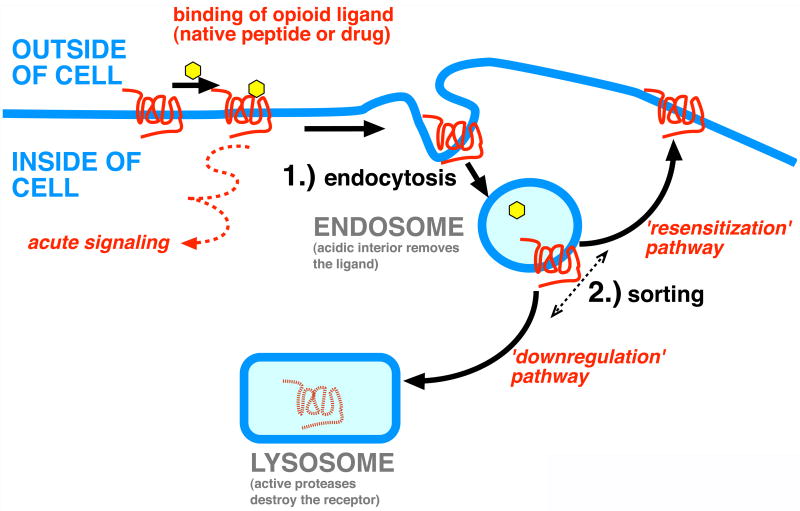

Beginning with early studies showing accumulation of enkephalin in lysosomes of NG108-15 cells (Law et al., 1984), it has been proposed that one mechanism by which opioids reduce receptor reserve is by promoting destruction of receptors by delivering internalized receptors to lysosomes, the major proteolytic organelle of the cell. The cloned δ opioid receptor was indeed shown to traffic to lysosomes after endocytosis via clathrin-coated pits and, remarkably, distinct GPCRs internalized by the same early endocytic pathway were found to differ greatly in their subsequent trafficking either back to the plasma membrane or to lysosomes (Tsao and von Zastrow, 2000). Further, these divergent membrane trafficking fates are known to contribute to the effectively opposite functional consequences of receptor resensitization or down-regulation (Law et al., 2000). Such molecular sorting of receptors after endocytosis is a recurring theme in GPCR regulation (Marchese et al., 2008; Hanyaloglu and von Zastrow, 2008) and in membrane trafficking in general (Gruenberg, 2001). The basic significance of opioid receptor sorting after endocytosis is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Simplified model depicting opioid receptor endosytosis and sorting.

Endocytosis of receptors, which occurs shortly after ligand-induced activation and the inititation of receptor signaling, removes receptors from the cell surface and promotes dissociation of the bound ligand due to the acidic environment present in the endosome (step 1 in Figure 1). Sorting of receptors occurs after endocytosis and determines if recept0rsx recycle to the plasma membrane or traffic to lysosomes (step 2 in Figure 1). Recycling promotes functional resensitization, effectively restoring opioid responsiveness, while trafficking to lysosomes attentuates responsiveness by promoteing proteolytic downregulation of receptors.

A number of cellular proteins that function in the molecular sorting and trafficking of opioid receptors to lysosomes have been identified (Hislop et al., 2004; Whistler et al., 2002), and there is particular interest currently in the role of covalent attachment of ubiquitin to receptors as a means of regulating this process (Hicke, 2001; Li et al., 2008; Marchese et al., 2008). Remarkably, the main structural determinant distinguishing the molecular sorting of opioid receptors is a non-ubiquitinated sequence that is fully contained in the receptor's cytoplasmic tail. The sequence present in the MOR1 splice variant drives receptor recycling to the plasma membrane after endocytosis. When this sequence is specifically mutated or deleted, mutant μ opioid receptors fail to recycle efficiently and traffic to lysosomes. Conversely, when this modular sequence is fused to the cytoplasmic tail of the δ opioid receptor, mutant receptors can be made to recycle rather than degrade in lysosomes after regulated endocytosis (Tanowitz and von Zastrow, 2003). Further, this modular sequence distinguishes the molecular sorting of μ opioid receptor isoforms produced by alternative splicing, resulting in significant differences between otherwise identical μ receptor isoforms in their ability to recover (or ‘resensitize’) functional signaling activity after ligand-induced activation (Tanowitz et al., 2008). The κ opioid receptor contains a different cytoplasmic sequence in its cytoplasmic tail that is important for efficient recycling of this receptor . It is also interesting to note that, while distinct opioid receptor subtypes appear generally similar in their ability to engage G proteins and arrestins, they differ considerably in binding to cellular proteins implicated in their sorting. A family of so-called ‘GPCR-associating sorting proteins’ (GASPs or GPRASPs) bind DOR better than MOR or KOR (Simonin et al., 2004; Whistler et al., 2002), Filamin A binds preferentially to MOR (Onoprishvili et al., 2003), and GEC1 to KOR (Chen et al., 2006). Together, these observations suggest that receptor-specific sorting proteins may represent an interesting new class of therapeutic targets.

4. Regulated endocytosis of opioid receptors in CNS neurons

4.1 A conserved ‘core’ regulatory machinery produces neuron-specific opioid effects

Studies of recombinant μ opioid receptors expressed in pyramidal neurons dissociated from rat hippocampus confirmed that regulated endocytosis occurs in this CNS-derived cell type with similarly rapid kinetics as in non-neural cell models, and identified similar agonist-selective regulation of endocytosis by morphine compared to opioid peptide (Bushell et al., 2002; Whistler et al., 1999). Importantly, subsequent studies of μ opioid receptor endocytosis in the locus coeruleus imaged in an acute brain slice preparation, which more closely approximates the native tissue environment of the CNS, also observed agonist-selective endocytosis paralleling that observed in non-neural cells (Arttamangkul et al., 2008). Studies carried out in medium spiny neurons cultured from rat striatum, however, found that morphine can promote rapid endocytosis of μ opioid receptors in these neurons nearly as effectively as opioid peptide agonists. Further, endocytosis induced by both peptide and non-peptide agonists was mediated by clathrin-coated pits, and promoted by receptor recruitment of arrestins (Haberstock-Debic et al., 2005). This suggests that non-neural cell models, while useful for elucidating core machinery mediating opioid receptor regulation, are not necessarily predictive of the effects of particular ligands on this machinery. They also suggest the existence of significant neuron-specific differences in the regulation of opioid receptors by opioid drug exposure, consistent with previous studies revealing different degrees of opioid receptor desensitization induced by morphine in distinct brain regions (Sim et al., 1996).

4.2 Regulation of opioid receptor signaling and endocytosis by activation of a distinct neuropeptide receptor

Studies of non-neural cell models expressing cloned receptor constructs have necessarily ignored the possible effects of other neuronal receptors that may affect opioid receptor regulation. Opioid-responsive CNS neurons, however, typically express multiple signaling receptors and function in circuits linked by non-opioid mediators. The NK1 neurokinin receptor, a distinct GPCR family member that is co-expressed with μ opioid receptors in parts of the striatum and amygdala, was found to inhibit morphine-induced desensitization and endocytosis of μ opioid receptors in medium spiny neurons when activated simultaneously in the same neurons by the NK1-specific agonist substance P (Yu et al., 2009). The mechanism of this inhibition involved depletion of net arrestin activity available for regulated endocytosis by activated NK1 receptors and, importantly, was verified to occur between native receptors when expressed at endogenous levels. Together these results indicate that the cellular machinery controlling opioid receptor signaling and endocytosis can be significantly affected by other signaling processes occurring in the same neurons, thus providing initial insight into the potential of this machinery to produce remarkably complex regulatory effects in the context of native neural circuits.

5. Physiological consequences of opioid receptor endocytosis

5.1 Assessing the occurrence of opioid receptor endocytosis in the intact CNS

It has been known for a number of years that opioid drugs such as etorphine, fentanyl and methadone can drive rapid endocytosis of μ opioid receptors in certain brain regions and in the spinal cord, while morphine does so to a significantly reduced degree (He et al., 2002; Keith et al., 1998; Trafton and Basbaum, 2004). It is also apparent that neuron-specific effects of opioids occur in the intact CNS, because morphine promotes rapid endocytosis of both native and recombinant μ opioid receptors in medium spiny neurons of the ventral striatum (Charlton et al., 2008; Haberstock-Debic et al., 2003). Agonist-selective endocytosis of delta opioid receptors has also been shown clearly in the intact CNS (Pradhan et al., 2009). While such drug-induced regulation of opioid receptor endocytosis is well established, it remains less clear the degree to which opioid receptor endocytosis occurs in response to opioid peptides released endogenously under normal conditions (Eckersell et al., 1998; Trafton and Basbaum, 2004). The development of improved mouse models allowing the more sensitive examination of opioid receptor endocytosis in the intact CNS may help to answer this important physiological question (Arttamangkul et al., 2008; Scherrer et al., 2006).

5.2 Efforts to understand the in vivo consequences of opioid receptor endocytosis

Unambiguously elucidating the in vivo consequences of opioid receptor endocytic trafficking is experimentally challenging. Nevertheless, recent studies using transgenic mouse models have provided some exciting and provocative first insights. Two models have been used to investigate the effect of μ opioid receptor endocytosis on antinociceptive tolerance to morphine. In one mouse model, the wild type μ opioid receptor gene was modified to create a mutant receptor with increased morphine-induced endocytosis (Kim et al., 2008). In another mouse model, a neuronal scaffolding protein (spinophilin) that facilitates opioid receptor desensitization and endocytosis was deleted, effectively reducing morphine-induced endocytosis (Charlton et al., 2008). Results from these distinct genetic approaches largely agree, suggesting that endocytosis of μ opioid receptors is associated with reduced development of antinociceptive tolerance to morphine in vivo. This finding is counterintuitive on its face, and two basic have been advanced to explain it. First, it has been proposed that the ‘resensitizing’ effect of receptor recycling is so strong that it dominates net cellular responsiveness to opioids under conditions of repeated or chronic exposure. Second, it has been proposed that endocytosis and recycling of receptors dynamically switch opioid signaling ‘off’ and then ‘on’ again, effectively protecting the cell from excessive signaling produced by sustained activation (Koch and Hollt, 2007; Martini and Whistler, 2007).

Another mouse model has been used to investigate endocytosis δ opioid receptors in vivo and its functional consequences. In this mouse, the δ opioid receptor gene was modified to add a fluorescent label to the receptor protein and thereby facilitate direct visualization of receptor localization in neurons (Scherrer et al., 2006). Using this mutant mouse, and comparing δ-selective agonists that differ in their ability to promote rapid endocytosis of receptors both in cultured cells and in vivo, precisely the opposite relationship between endocytosis of δ opioid receptors and anti-nociceptive tolerance was observed; a significant increase in opioid tolerance correlated with endocytosis (Pradhan et al., 2009). This apparently reversed association between tolerance and endocytosis of μ compared to δ opioid receptors has not been experimentally resolved. It is important to note that μ and δ opioid-mediated antinociception were assessed differently in the respective studies, which is required due to the different clinical pharmacology of the respective opioid agonists (Inturrisi, 2002) and different pain modalities affected by these receptors (Scherrer et al., 2009). An intriguiing possibility is that the reversal in the correlation between receptor endocytosis and physiological tolerance is precisely due to differences in the molecular sorting of μ and δ opioid receptors after endocytosis. Specifically, preferential recycling of μ opioid receptors, by promoting functional recovery of cellular opioid signaling, would be expected to sustain opioid responsiveness and decrease physiological tolerance following prolonged opioid administration. The inability of internalized δ opioid receptors to recycle efficiently, and preferential trafficking of these receptors to lysosomes, would be expected to reduce net opioid responsiveness following prolonged opioid administration and thus increase physiological tolerance. It will be very interesting to testing this hypotheses in vivo, such as by generating mutant mice in which the sorting specificity of the respective receptors is reversed.

6. Conclusion and future implications

Considerable progress has been made in elucidating fundamental mechanisms of regulated opioid receptor trafficking in the endocytic pathway, and we now have the beginnings of mechanistic insight into how these mechanisms influence opioid signaling at the cellular and systems levels. While much remains unresolved, and there is much work remaining to be done, it might be useful in closing to emphasize two implications of potential interest for translational consideration.

6.1 Functional selectivity or agonist bias among opioids

Functional selectivity or agonist bias, as suggested by agonist-selective endocytosis of opioid receptors, is a concept that is rapidly gaining traction in molecular pharmacology and is of potentially great significance both for guiding the clinical use of opioids and in drug development efforts. The ability of existing opioids to selectively drive distinct mechanisms of opioid receptor signaling and regulation could, in principle, provide useful new insight into diverse and complex effects observed in the clinic, particularly in the setting of repeated or chronic administration. Cellular model systems and assays used to discover such differences could provide a basis for developing screening assays to identify new compounds with even more pronounced functional selectivity.

6.2 Molecular sorting of opioid receptors as a potential therapeutic target

The profound functional consequences of molecular sorting of opioid receptors after endocytosis suggest that manipulating biochemical machinery responsible for sorting particular receptors might be therapeutically useful. The identification of limited structural determinants (regions of the cytoplasmic tail from 4 to 12 residues in length) that are sufficient to determine major differences in the molecular sorting of opioid receptors after endocytosis, and the specificity with which distinct receptor types bind cytoplasmic sorting proteins, together suggest that this machinery is potentially ‘drugable’ using small molecules. Current cell-based assays for this sorting could serve as a basis for developing relevant screening assays and validation tools for developing such compounds. Compounds capable of manipulating this machinery would offer a completely new way of intervening in opioid signaling therapeutically, and with pharmacological selectivity and predicted actions differing fundamentally from those of conventional opioid ligands.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arttamangkul S, Quillinan N, Low MJ, von Zastrow M, Pintar J, Williams JT. Differential activation and trafficking of micro-opioid receptors in brain slices. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:972–979. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benovic JL, Strasser RH, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-adrenergic receptor kinase: identification of a novel protein kinase that phosphorylates the agonist-occupied form of the receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2797–2801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland S, Conner M, Osborne P, Furness J, Christie M. Opioid Agonists Have Different Efficacy Profiles for G Protein Activation, Rapid Desensitization, and Endocytosis of Mu-opioid Receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18776–18784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushell T, Endoh T, Simen AA, Ren D, Bindokas VP, Miller RJ. Molecular components of tolerance to opiates in single hippocampal neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:55–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton JJ, Allen PB, Psifogeorgou K, Chakravarty S, Gomes I, Neve RL, Devi LA, Greengard P, Nestler EJ, Zachariou V. Multiple actions of spinophilin regulate mu opioid receptor function. Neuron. 2008;58:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin C, Goldstein A. Reduction in opiate receptor reserve in morphine tolerant guinea pig ilea. Life Sciences. 1982;31:1687–1690. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Li JG, Chen Y, Huang P, Wang Y, Liu-Chen LY. GEC1 interacts with the kappa opioid receptor and enhances expression of the receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7983–7993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu P, Murray S, Lissin D, von Zastrow M. Delta and kappa opioid receptors are differentially regulated by dynamin-dependent endocytosis when activated by the same alkaloid agonist. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27124–27130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner SD, Schmid SL. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature. 2003;422:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa T, Ogino Y, Munson PJ, Onaran HO, Rodbard D. Drug efficacy at guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory protein-linked receptors: thermodynamic interpretation of negative antagonism and of receptor activity in the absence of ligand. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:549–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckersell CB, Popper P, Micevych PE. Estrogen-induced alteration of mu-opioid receptor immunoreactivity in the medial preoptic nucleus and medial amygdala. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3967–3976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03967.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CJ, Keith DJ, Morrison H, Magendzo K, Edwards RH. Cloning of a delta opioid receptor by functional expression. Science. 1992;258:1952–1955. doi: 10.1126/science.1335167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CJ, von Zastrow M. A state of the delta opioid receptor that is ‘blind’ to opioid peptides yet retains high affinity for the opiate alkaloids. In: van Ree JM, Mulder AH, Wiegant VM, van Wimersma Greidanus TB, editors. New Leads in Opioid Research. New York: Excerpta Medica; 1990. pp. 159–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SS, Downey WE, 3rd, Colapietro AM, Barak LS, Menard L, Caron MG. Role of beta-arrestin in mediating agonist-promoted G protein-coupled receptor internalization. Science. 1996;271:363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman NJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1996;51:319–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galandrin S, Oligny-Longpre G, Bouvier M. The evasive nature of drug efficacy: implications for drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman OJ, Krupnick JG, Santini F, Gurevich VV, Penn RB, Gagnon AW, Keen JH, Benovic JL. Beta-arrestin acts as a clathrin adaptor in endocytosis of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 1996;383:447–450. doi: 10.1038/383447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich VV, Benovic JL. Mechanism of phosphorylation-recognition by visual arrestin and the transition of arrestin into a high affinity binding state. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:161–169. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberstock-Debic H, Kim KA, Yu YJ, von Zastrow M. Morphine promotes rapid, arrestin-dependent endocytosis of mu-opioid receptors in striatal neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7847–7857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5045-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberstock-Debic H, Wein M, Barrot M, Colago EE, Rahman Z, Neve RL, Pickel VM, Nestler EJ, von Zastrow M, Svingos AL. Morphine acutely regulates opioid receptor trafficking selectively in dendrites of nucleus accumbens neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4324–4332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04324.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Fong J, von Zastrow M, Whistler JL. Regulation of opioid receptor trafficking and morphine tolerance by receptor oligomerization. Cell. 2002;108:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00613-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L. Protein regulation by monoubiquitin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:195–201. doi: 10.1038/35056583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hislop JN, Marley A, von Zastrow M. Role of mammalian vacuolar protein-sorting proteins in endocytic trafficking of a non-ubiquitinated G protein-coupled receptor to lysosomes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22522–22531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inturrisi CE. Clinical pharmacology of opioids for pain. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:S3–13. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith DE, Anton B, Murray SR, Zaki PA, Chu PC, Lissin DV, Monteillet AG, Stewart PL, Evans CJ, von Zastrow M. mu-Opioid receptor internalization: opiate drugs have differential effects on a conserved endocytic mechanism in vitro and in the mammalian brain. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:377–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith DE, Murray SR, Zaki PA, Chu PC, Lissin DV, Kang L, Evans CJ, von Zastrow M. Morphine activates opioid receptors without causing their rapid internalization. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19021–19024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin TP. Cellular assays as portals to seven-transmembrane receptor-based drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:617–626. doi: 10.1038/nrd2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer BL, Befort K, Gaveriaux RC, Hirth CG. The delta-opioid receptor: isolation of a cDNA by expression cloning and pharmacological characterization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:12048–12052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JA, Bartlett S, He L, Nielsen CK, Chang AM, Kharazia V, Waldhoer M, Ou CJ, Taylor S, Ferwerda M, et al. Morphine-Induced Receptor Endocytosis in a Novel Knockin Mouse Reduces Tolerance and Dependence. Curr Biol. 2008;18:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch T, Hollt V. Role of receptor internalization in opioid tolerance and dependence. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;117:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovoor A, Celver J, Abdryashitov RI, Chavkin C, Gurevich VV. Targeted construction of phosphorylation-independent beta-arrestin mutants with constitutive activity in cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:6831–6834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.6831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovoor A, Celver JP, Wu A, Chavkin C. Agonist induced homologous desensitization of mu-opioid receptors mediated by G protein-coupled receptor kinases is dependent on agonist efficacy. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;54:704–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law PY, Hom DS, Loh HH. Loss of opiate receptor activity in neuroblastoma × glioma NG108-15 cells after chronic etorphine treatment: a multiple step process. Mol Pharmacol. 1982;72:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law PY, Hom DS, Loh HH. Down-regulation of opiate receptor in neuroblastoma × glioma NG108-15 hybrid cells: chloroquine promotes accumulation of tritiated enkephalin in the lysosomes. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:4096–4104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law PY, Wong YH, Loh HH. Molecular mechanisms and regulation of opioid receptor signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:389–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JG, Haines DS, Liu-Chen LY. Agonist-promoted Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of the human kappa-opioid receptor is involved in receptor down-regulation. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1319–1330. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JG, Luo LY, Krupnick JG, Benovic JL, Liu-Chen LY. U50,488H-induced internalization of the human kappa opioid receptor involves a beta-arrestin- and dynamin-dependent mechanism. Kappa receptor internalization is not required for mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:12087–12094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese A, Paing MM, Temple BR, Trejo J. G protein-coupled receptor sorting to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:601–629. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini L, Whistler JL. The role of mu opioid receptor desensitization and endocytosis in morphine tolerance and dependence. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:556–564. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoprishvili I, Andria ML, Kramer HK, Ancevska-Taneva N, Hiller JM, Simon EJ. Interaction between the mu opioid receptor and filamin A is involved in receptor regulation and trafficking. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:1092–1100. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AA, Becker JA, Scherrer G, Tryoen-Toth P, Filliol D, Matifas A, Massotte D, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Kieffer BL. In vivo delta opioid receptor internalization controls behavioral effects of agonists. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer G, Imamachi N, Cao YQ, Contet C, Mennicken F, O'Donnell D, Kieffer BL, Basbaum AI. Dissociation of the opioid receptor mechanisms that control mechanical and heat pain. Cell. 2009;137:1148–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer G, Tryoen-Toth P, Filliol D, Matifas A, Laustriat D, Cao YQ, Basbaum AI, Dierich A, Vonesh JL, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Kieffer BL. Knockin mice expressing fluorescent delta-opioid receptors uncover G protein-coupled receptor dynamics in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9691–9696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603359103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SK, Klee WA, Nirenberg M. Opiate-dependent modulation of adenylate cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:3365–3369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim LJ, Selley DE, Dworkin SI, Childers SR. Effects of chronic morphine administration on mu opioid receptor- stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS autoradiography in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2684–2692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02684.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonin F, Karcher P, Boeuf JJ, Matifas A, Kieffer BL. Identification of a novel family of G protein-coupled receptor associated sorting proteins. J Neurochem. 2004;89:766–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanowitz M, Hislop JN, von Zastrow M. Alternative splicing determines the post-endocytic sorting fate of G-protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35614–35621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806588200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanowitz M, von Zastrow M. A novel endocytic recycling signal that distinguishes the membrane trafficking of naturally occurring opioid receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45978–45986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafton JA, Basbaum AI. [d-Ala2,N-MePhe4,Gly-ol5]enkephalin-induced internalization of the micro opioid receptor in the spinal cord of morphine tolerant rats. Neuroscience. 2004;125:541–543. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao PI, von Zastrow M. Type-specific sorting of G protein-coupled receptors after endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11130–11140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zastrow M, Keith DE, Zaki P, Evans CJ. Morphine and opioid peptide cause opposing effects on the endocytic trafficking of opioid receptors. Regul Peptides. 1994;54:315. [Google Scholar]

- von Zastrow M, Keith DEJ, Evans CJ. Agonist-induced state of the delta-opioid receptor that discriminates between opioid peptides and opiate alkaloids. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44:166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whistler JL, Chuang HH, Chu P, Jan LY, von Zastrow M. Functional dissociation of mu opioid receptor signaling and endocytosis: implications for the biology of opiate tolerance and addiction. Neuron. 1999;23:737–746. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whistler JL, Enquist J, Marley A, Fong J, Gladher F, Tsuruda P, Murray SR, von Zastrow M. Modulation of postendocytic sorting of G protein-coupled receptors. Science. 2002;297:615–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1073308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whistler JL, von Zastrow M. Morphine-activated opioid receptors elude desensitization by beta-arrestin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9914–9919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, Christie MJ, Manzoni O. Cellular and synaptic adaptations mediating opioid dependence. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:299–343. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu YJ, Arttamangkul S, Evans CJ, Williams JT, von Zastrow M. Neurokinin 1 receptors regulate morphine-induced endocytosis and desensitization of mu-opioid receptors in CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:222–233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4315-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Ferguson SS, Barak LS, Bodduluri SR, Laporte SA, Law PY, Caron MG. Role for G protein-coupled receptor kinase in agonist-specific regulation of mu-opioid receptor responsiveness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:7157–7162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]