Abstract

The modulation of mRNA turnover is gaining recognition as a mechanism by which Staphylococcus aureus regulates gene expression, but the factors that orchestrate alterations in transcript degradation are poorly understood. In that regard, we previously found that 138 mRNA species, including transcripts coding for the virulence factors protein A (spa) and collagen-binding protein (cna), are stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner during exponential phase growth, suggesting that SarA directly or indirectly affects the RNA turnover properties of these transcripts. Herein, we expanded our characterization of the effects of sarA on mRNA turnover during late-exponential and stationary phases of growth. Results revealed that the locus affects the RNA degradation properties of cells during both growth phases. Further, using gel mobility shift assays and RIP-Chip, it was found that SarA protein is capable of binding mRNA species that it stabilizes both in vitro and within bacterial cells. Taken together, these results suggest that SarA post-transcriptionally regulates S. aureus gene expression in a manner that involves binding to and consequently altering the mRNA turnover properties of target transcripts.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, SarA, RNA degradation

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a human pathogen that causes nosocomial and community-associated infections that result in high rates of morbidity and mortality (Klevens et al., 2007; Deleo et al., 2010). The organism largely owes its ability to cause infection to the production of an array of virulence factors which, in the laboratory setting, are coordinately regulated in a cell density-dependent manner. Cell surface-associated factors are predominantly expressed during exponential phase growth whereas extracellular factors are predominantly produced during stationary phase growth (Novick, 2003; Bronner et al., 2004). The organism’s virulence factors are also coordinately regulated in response to endogenous and exogenous cues, including cellular stresses and sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. A plethora of two component regulatory systems (TCRS) and nucleic acid-binding proteins have been hypothesized to modulate S. aureus virulence factor expression.

Of the 17 TCRS identified in S. aureus to date, the best-characterized is the accessory gene regulator (agr) locus. The agr locus encodes a quorum-sensing TCRS, AgrAC, whose regulatory effects are generally thought to be mediated by a regulatory RNA molecule, RNAIII. Within laboratory culture conditions, RNAIII expression peaks during the transition to stationary phase growth (Novick, 2003). RNAIII has been shown to modulate virulence factor expression by directly binding to target mRNA species, thereby affecting their stability and translation properties (Morfeldt et al., 1995; Huntzinger et al., 2005; Geisinger et al., 2006; Boisset et al., 2007). For instance, RNAIII binding to the cell surface factor protein A (spa) transcript creates a substrate for ribonuclease III digestion, which, in-turn, accelerates spa mRNA digestion and consequently limits Spa production (Huntzinger et al., 2005). Conversely, the binding of RNAIII to the extracellular virulence factor α-hemolysin (hla) transcript liberates the mRNA’s Shine–Dalgarno sequence and increases Hla production (Morfeldt et al., 1995). Similar mechanisms of RNAIII regulation have been documented for the virulence factor coa (Chevalier et al., 2010) and the regulatory locus repressor of toxins (rot; Boisset et al., 2007).

In addition to TCRS, S. aureus produces a family of DNA-binding proteins that regulate virulence factor expression. The best-characterized to date is the staphylococcal accessory regulator nucleic acid-binding protein, SarA. The sarA locus consists of a 1.2 kb DNA region that produces three overlapping transcriptional units (sarB, sarC, and sarA), each of which terminates at the same site and encodes for the SarA protein (Chien and Cheung, 1998). Unlike RNAIII, SarA is constitutively produced throughout S. aureus growth phases, however the expression of the individual sar transcripts occurs in a growth phase-dependent manner; sarA and sarB are primarily transcribed during exponential phase growth whereas sarC is predominantly expressed during stationary phase growth (Manna et al., 1998; Blevins et al., 1999). SarA has been characterized as a pleiotropic transcriptional regulator of virulence factors that can bind to the promoter regions of a subset of genes that it regulates, such as hla (α-hemolysin) and spa (protein A; Chien and Cheung, 1998; Chien et al., 1999). Nonetheless, several observations have suggested that SarA’s regulatory effects might be more complex than initially appreciated. Arvidson and colleagues have reported that, in addition to affecting spa transcript synthesis, SarA may also indirectly regulate Spa production (Tegmark et al., 2000). Further, no clear SarA consensus binding site has been defined; Cheung and colleagues found that SarA binds a 26 base pair (bp) region termed the SarA box, whereas Sterba et al. (2003) have defined the SarA box to be a 7 bp sequence, which is present more than 1000 times within the S. aureus genome, indicating that the protein may have the capability of binding the chromosome more frequently than one might expect for a bona fide transcription factor (Chien et al., 1999). In that regard, others have suggested that SarA is a histone-like protein whose regulatory effects are a function of altering DNA topology and, consequently, promoter accessibility (Schumacher et al., 2001).

In Escherichia coli, histone-like proteins can post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by binding directly to mRNA molecules and influencing the transcript’s stability and translation (Balandina et al., 2001; Brescia et al., 2004). Accordingly, based on the possibility that SarA may behave as a histone-like protein, we hypothesized that the protein’s regulatory effects may, in part, be due to its ability to bind and subsequently modulate the mRNA turnover properties of target transcripts. As a first step toward testing that prediction, we found that 138 mRNA species that are produced during S. aureus exponential phase growth, including the known SarA-regulated genes spa and cna, are also stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner (Roberts et al., 2006). More specifically, these mRNA transcripts are stabilized in a sarA+ background as compared to isogenic sarA− cells, raising the possibility that SarA protein may bind these transcripts in a manner that affects their stability and, consequently, expression. In the current body of work we extended our evaluation of this phenomenon by investigating whether the mRNA turnover properties of late-exponential and/or stationary phase transcripts are also modulated in a sarA-dependent manner. Results revealed that this is indeed the case; the sarA locus affects the mRNA turnover properties of transcripts produced during both phases of growth. Further, using ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation (RIP-Chip) assays, we found that SarA binds these transcripts within S. aureus cells. Results were verified via gel-shift mobility assays. Taken together, these results indicate that SarA is capable of binding cellular mRNA species and that the protein’s regulatory effects could be attributable to its ability to directly modulate the mRNA turnover properties of target mRNA species.

Materials and Methods

Growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Overnight S. aureus cultures were diluted 1:100 into fresh brain–heart infusion (BHI) broth with a flask to volume ratio of 5:1 and were incubated at 37oC with aeration on a rotary shaker at 225 rpm. When cultures reached mid-exponential (OD600 nm = 0.25–0.30), late-exponential (OD600 nm = 1.1–1.2), or stationary (24 h post-inoculation) phase, rifampicin (200 μg ml−1; Sigma; St. Louis, MO) was added to arrest transcription. Aliquots of cells were removed at 0, 2.5, 5, 15, and 30 min post-transcriptional arrest, mixed with an equi-volume of ice-cold acetone:ethanol (1:1) and RNA was isolated, as previously described (Anderson et al., 2006; Roberts et al., 2006; Olson et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| UAMS-1 | Wild type S. aureus osteomyelitis isolate | Gillaspy et al. (1995); Cassat et al. (2005) |

| UAMS-929 | UAMS-1 (ΔsarA) | Blevins et al. (1999) |

| KLA43 | UAMS-929 (pKLA40) | This study |

| RN4220 | Restriction-deficient S. aureus | de Azavedo et al. (1985) |

| INVαF | E. coli competent cells; lacZΔM15 | Invitrogen |

| DH5α | E. coli competent cells | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | Relevant genotype | |

| pCRII | TOPO-TA cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pBK123 | CamR derivative of pCN51 | Charpentier et al. (2004) |

| pKLA40 | pBK123::c-Myc-SarA | This study |

Genechip®microarrays

All microarray studies were performed as previously described (Anderson et al., 2006, 2010; Roberts et al., 2006; Olson et al., 2011). Briefly, 10 μg of each bacterial RNA sample was labeled and hybridized to a S. aureus GeneChip®, following the manufacturer’s recommendations for antisense prokaryotic arrays (Affymetrix; Santa Clara, CA). Average GeneChip® signal intensities for biological replicates (n ≥ 2) for each strain and time point were obtained from values normalized to exogenous transcripts. The half-life of each RNA transcript was determined using a “twofold” algorithm (Selinger et al., 2003) and was measured as the time point at which a given RNA signal intensity decreased two-fold as compared to that transcript at 0 min post-transcriptional arrest using GeneSpring 7.2 software (Agilent Technologies; Redwood City, CA).

In vitro transcription

DNA templates consisting of the full-length spa transcriptional unit or derivatives containing 3′ or 5′ deletions were created by PCR amplification using UAMS-1 chromosomal DNA as a template and oligonucleotides listed in Table 2. Resulting PCR products contained a 5′ T7 RNA polymerase promoter and transcription start site and were used as templates for generating corresponding RNA species using a T7 MegaScript In vitro Transcription Kit (Ambion; Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, for transcription reactions, approximately 1 μg of PCR product was incubated for 3 h at 37oC with 7.5 mM of a NTP mix and T7 RNA polymerase to generate the indicated RNA species. Template DNA was degraded with four units of TurboDNase I for 15 min at 37oC, and in vitro transcribed RNA was recovered by lithium chloride precipitation and resuspended in nuclease-free water. RNA concentration of the synthesized product was determined spectrophotometrically (OD260 nm 1.0 = 40 μg ml−1) and the integrity of the transcript was evaluated on a 1.2% agarose–0.66 M formaldehyde denaturing gel.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|

| RT-PCR | |

| cna F | AACGAACAAGTATACACCAGGAGAG |

| cna R | TTTGCTTTTTCATCTAATCCTGTC |

| norA F | GCAGGTGCATTAGGCATTTTAGC |

| norA R | TGCCGATAAACCGAACGCTAAG |

| spa F | GCAGAAGCTAAAAAGCTAAATGATG |

| spa R | GCTCACTGAAGGATCGTCTTTAAGG |

| sarA F | TTTTAACCATGGCAATTACAAAAAT |

| sarA R | TTTCTCTTTGTTTTCGCTGATGTAT |

| PCR-MEDIATED IN VITRO TRANSCRIPTION* | |

| L 1–450 spa T7 F | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCATACAGGGGGTATTAATTTGAAAA |

| L 1–450 spa R | ATCCTAGAATTCTCTTCGTTCAAGTTAGGCATGTTCA |

| L −250 spa T7 F | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGTTCAACAAAGATCAACAAAGCGCC |

| L −250 spa R | AGTAGAAAGTGTTGAGGCGTTTCAG |

| CLONING†,‡ | |

| c-Myc-SarA F | ATCCTAGTCGACGCTAACCCAGAAATACAATCACTGTGTC |

| c-Myc-SarA R | ATCCTAGGATCCTTACAGATCTTCTTCGCTGATCAGTTTCTGTTCTA GTTCAATTTCGTTGTTTGCTTCAGTG |

*Bolded nucleotides indicate T7 promoter sequence.

†Underlined nucleotides indicate restriction sites.

‡Italicized nucleotides indicate the c-Myc epitope.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

In vitro transcribed spa mRNA or a PCR product containing the endogenous hla promoter were 3′ end-labeled with digoxigenin-ddUTP (DIG; Roche Applied Science; Indianapolis IN) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. One picomole DIG-mRNA or -DNA was mixed with 0, 7.3, 36.6, 73.3, or 366.5 pmol purified SarA protein then, incubated for 15 min at 37oC in gel-shift buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 8.0, 8 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl), cooled on ice and the entire sample volume was electrophoresed in 1.2% agarose–0.66 M formaldehyde denaturing gels. Next, RNA-protein or DNA-protein complexes were transferred via capillary action to nylon membranes overnight in 20× SSC buffer (3 M NaCl, 300 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0). Nucleic acid was then cross-linked to the membrane by UV irradiation in a Stratalinker® UV crosslinker (Stratagene; La Jolla, CA) twice at 1200 (×100) microjoules. Membranes were probed for presence of the DIG-labeled RNA or DNA using anti-DIG Fab fragments conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (1:10,000; Roche Applied Science) and visualized chemiluminescently with CSPD reagent (Roche Applied Science). For all binding assays, bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a negative control for non-specific RNA-protein and DNA-protein interactions.

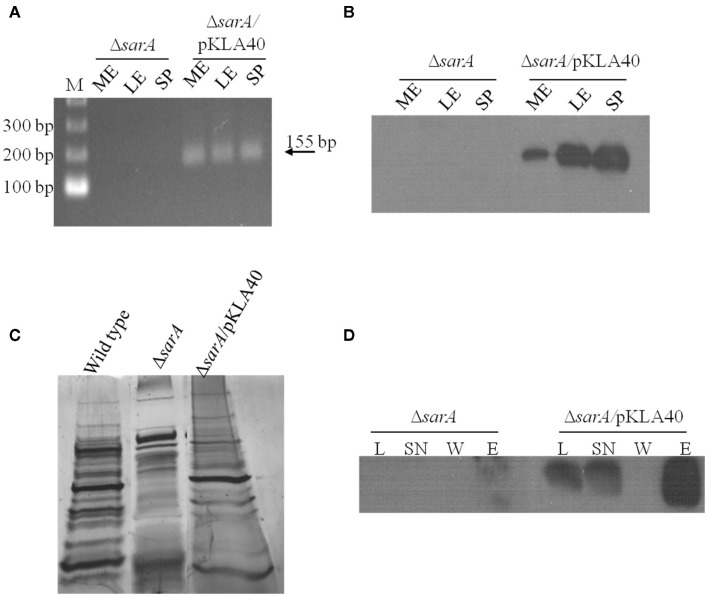

c-Myc-SarA construction

A c-Myc epitope was translationally fused to the C-terminus of the SarA open reading frame. To do so, 615 bp of the S. aureus strain UAMS-1 sarA gene and its corresponding P1 promoter region were amplified by PCR using primers c-Myc-SarA F and c-Myc-SarA R (Table 2); the latter included a c-Myc epitope and 3′ flanking restriction enzyme site. The resultant PCR product was gel-purified and digested with restriction enzymes SalI and BamHI and subcloned into pBK123 (Charpentier et al., 2004) to generate the plasmid pKLA40. Plasmid pKLA40 was then electroporated into the restriction-negative strain of S. aureus, RN4220 (de Azavedo et al., 1985) and transfected into UAMS-929 (ΔsarA) via Φ11-mediated phage to generate strain KLA43 and the plasmid was sequenced to confirm the integrity of the insert. c-Myc-SarA functionality was confirmed by examining the ability of the epitope-tagged protein to complement the exoprotein profile of UAMS-929(ΔsarA) cells. Briefly, supernates from stationary phase cultures of S. aureus UAMS-1, UAMS-929(ΔsarA), and KLA43 (ΔsarA; c-Myc-SarA) were collected, filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon membrane, and compared by electrophoresis in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and silver staining (Bio-Rad Life Science, Hercules, CA).

Western blotting

Cultures were grown to the indicated growth phase and cells were mechanically disrupted in TE buffer in BIO101 lysing matrix B tubes using a FastPrep120 shaker (MP Biomedicals; Solon OH). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 4oC for 15 min and the protein concentration of supernatants were quantified by Bradford protein assays. For confirmation of c-Myc-SarA expression, 1 μg of protein was electrophoresed in a 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked with 10% milk in Tween-TBS (TTBS; TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) and rabbit polyclonal anti-c-Myc antibody (1:1000; Sigma Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) was used to probe for presence of the c-Myc-SarA protein. Following incubation with the primary antibody, membranes were washed in TTBS and probed with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000; Promega; Madison, WI). Membranes were washed and c-Myc-SarA was detected chemiluminescently by ECLTM (Amersham BioSciences; Piscataway NJ). Confirmation of successful RIP was confirmed by loading 10 μl of cell lysate, cell supernate, wash, or elution fractions and subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting, as described above.

Ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation (RIP-Chip)

Ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation was performed using a c-Myc Tag/Co-IP Kit (Pierce Biotechnology; Rockford, IL). To do so, S. aureus strains UAMS-929 (ΔsarA; negative control) and KLA43 (ΔsarA/pKLA40::c-Myc-SarA) were grown to mid-exponential phase and RNA-binding proteins were cross-linked to RNA by incubating the cells for 30 min with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature. Cross-linking was quenched by adding 125 mM glycine for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were centrifuged at 3000 RPM for 10 min at 4oC and cell pellets were washed twice in 1 ml ice-cold TBS, resuspended in 350 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM PMSF) and were lysed by the addition 100 μg ml−1 lysostaphin (Ambi; Lawrence, NY) at 37oC for 30 min. Next, an equal volume of 2× immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 2% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF) was added and suspensions were incubated for an additional 10 min at 37oC. Nucleic acids were fragmented with a Sonic Dismembrator (Fisher) on ice twice for 15 s using an output setting of one with 15 s rests on ice between each pulse and cell debris was subsequently removed by centrifugation for 10 min at 4oC. Next, 800 μl of the supernatant was mixed with 10 μl of anti-c-Myc agarose (Pierce Biotechnology; Rockford IL) and then added to IP spin columns (Pierce Biotechnology) and incubated overnight at 4oC to collect c-Myc-SarA/RNA and DNA complexes. Columns were washed five times with 1× IP buffer and c-Myc-SarA complexes were eluted in 50 μl of elution buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) by first incubating at 65oC for 10 in followed by centrifugation at 4oC to collect eluate. Cross-linking was reversed by incubating eluate for 2 h at 42oC and then 6 h at 65oC in 0.5× elution buffer containing 0.8 mg ml−1 pronase. For chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-chip) experiments used to detect known SarA-DNA interactions, liberated DNA was purified using a PCR Clean-Up Kit (Qiagen) per manufacturer’s recommendations and hybridized to a GeneChip® and processed as described above. For RIP-chIP experiments, liberated nucleic acid was treated with 17 U of RNase-Free DNase I (Qiagen) and RNA was purified using a Clean and Concentrator Kit (Zymo Research; Orange, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. All assays were performed in triplicate for each strain and purification of the c-Myc-SarA protein was confirmed via Western blotting. Following IP, bacterial RNA was amplified and reverse-transcribed using a MessageAmp II-Bacteria Prokaryotic RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion). 1.5 μg of the amplified cDNA was then hybridized to a GeneChip® and processed as described above. The fold change in average signal intensity of KLA43 replicates as compared to the average signal intensity of UAMS-929 (negative control) replicates was calculated for each GeneChip® qualifier. SarA was considered to bind DNA or transcripts that exhibited a signal intensity that was ≥ two-fold in KLA43 samples and greater than two standard deviations from the average signal intensity (background), as compared to UAMS-929 cells.

Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

For standard qRT-PCR reactions, 25 ng of total bacterial RNA were reverse-transcribed, amplified, and measured using a LightCycler® RNA Master SYBR Green I kit per the manufacturer’s recommendations (Roche Applied Science). As an internal control by which to standardize RNA loading, 0.5 pg of RNA was used to quantitate the amount of 16S rRNA in each sample. Transcript concentrations were calculated using LightCycler® software and LightCycler® Control Cytokine RNA titration kit as a standard for determining the copies of each transcript present per reaction. Final concentration values are listed as normalized to 16S rRNA abundance. Transcript half-lives were calculated as the time point at which RNA titers exhibited a ≥ two-fold decrease in signal intensity.

Results

It is well recognized that SarA is a pleiotropic regulator of S. aureus virulence factors, yet the mechanism(s) by which the protein affects gene expression is incompletely understood. Several studies have shown that the molecule affects the transcript synthesis of target genes, however the lack of a consensus SarA-binding sequence and evidence of indirect control of gene expression have implicated SarA in post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Accordingly, it has also been hypothesized that SarA regulates S. aureus gene expression via modulating the mRNA turnover properties of target transcripts. In support of this hypothesis, we have previously shown that 138 mRNA species, including the virulence factor transcripts protein A (spa) and collagen-binding protein (cna) are stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner (Roberts et al., 2006). Our current efforts are designed to expand upon these initial studies and further define the role for sarA in modulating mRNA turnover.

sarA stabilizes subsets of mRNA species in a growth phase-dependent manner

Herein, we set out to establish whether the degradation properties of mRNA species that are expressed during late-exponential and/or stationary phase growth are affected by a product of the sarA locus. To do so, S. aureus UAMS-1 (wild type) and UAMS-929 (UAMS-1ΔsarA) were grown to late-exponential or stationary phase growth and transcription was halted by the addition of rifampicin. Total bacterial RNA was then purified from aliquots of cells at 0, 2.5, 5, 15, and 30 min post-transcriptional arrest and the mRNA titers of expressed transcripts were then measured using Affymetrix GeneChips®. A comparsion of each transcript’s titer at 0 min post-transcriptional arrest to that of each subsequent time point allowed the half-lives of each mRNA to be measured, as previously described (Anderson et al., 2006, 2010; Roberts et al., 2006; Olson et al., 2011).

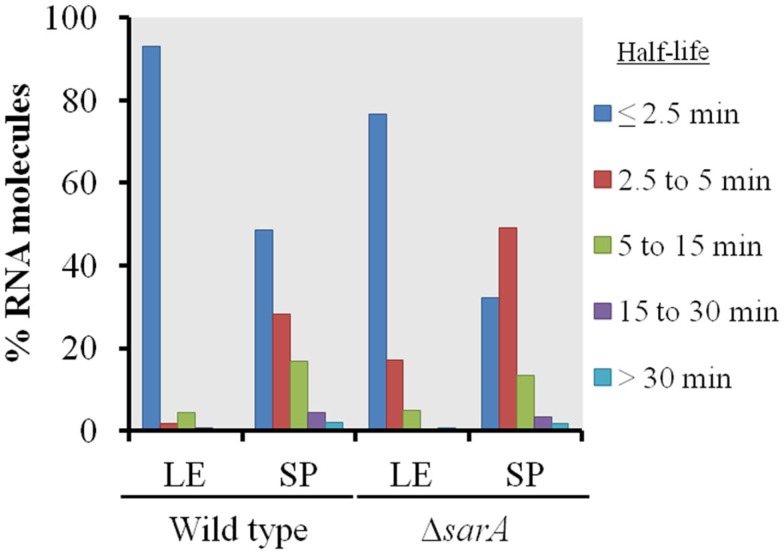

As shown in Figure 1, in general terms, the global RNA turnover properties of UAMS-1 and UAMS-1ΔsarA cells exhibited a similar trend that is consistent with our previous observations; bulk mRNA turnover occurs more rapidly in exponential phase as compared to stationary phase cells (Olson et al., 2011). Despite these similarities, a more detailed analysis of RNA degradation properties of individual mRNA species within each strain background indicated that sarA influences the stability of many transcripts. More specifically, 93.2 and 48.4% of transcripts exhibited half-lives of <2.5 min during late-exponential and stationary phase growth, respectively, in the wild type strain (Table 3). Conversely, 76.9 and 32.5% of transcripts were degraded within 2.5 min in late-exponential and stationary phase ΔsarA cells, suggesting that sarA affects the stability of a subset of transcripts. Within this subset, 68 (3.2%; Supplemental Table S1 in Supplementary Material) and 325 (15.3%; Supplemental Table S2 in Supplementary Material) of late-log and stationary phase transcripts, respectively, were less stable in ΔsarA cells, indicating that they are stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner. Conversely, 385 (18.2%; Supplemental Table S3 in Supplementary Material) and 580 (27.2%; Supplemental Table S4 in Supplementary Material) of transcripts were more stable in ΔsarA cells, indicating that, like RNAIII, SarA may facilitate degradation of a particular subset of mRNA species.

Figure 1.

Global transcript turnover properties of wild type and ΔsarA cells. The global RNA turnover properties of UAMS-1 (wild type) and isogenic ΔsarA (ΔsarA) cells during late-exponential (LE) and stationary phase (SP) growth are graphed. Percentages of total transcripts with half-lives of ≤2.5, 2.5–5, 5–15, 15–30, and ≥30 min are shown.

Table 3.

S. aureus growth phase mRNA degradation.

| UAMS-1 |

ΔsarA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late-log |

Stationary |

Late-log |

Stationary |

|||||

| Transcripts | Percentage | Transcripts | Percentage | Transcripts | Percentage | Transcripts | Percentage | |

| ≤2.5 min | 2044 | 93.2 | 1115 | 48.4 | 1620 | 76.9 | 691 | 32.5 |

| 2.5–5 min | 36 | 1.6 | 648 | 28.1 | 359 | 17.0 | 1032 | 48.5 |

| 5–15 min | 92 | 4.2 | 389 | 16.9 | 104 | 4.9 | 294 | 13.8 |

| 15–30 min | 16 | 0.7 | 103 | 4.5 | 9 | 0.4 | 69 | 3.2 |

| >30 min | 4 | 0.2 | 47 | 2.0 | 15 | 0.7 | 40 | 1.9 |

| Total | 2192a | 100 | 2302b | 100 | 2107c | 100 | 2126d | 100 |

a55 RNA species could not be measured.

b27 RNA species could not be measured.

c38 RNA species could not be measured.

d18 RNA species could not be measured.

sarA affects virulence factor mRNA stability

Results also indicated that the mRNA turnover properties of many virulence factors are influenced by sarA, but that these effects predominantly occur during stationary phase growth. More specifically, during late-exponential phase growth the transcripts coding for three virulence-associated genes were stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner (Table 4). Among these were two metabolic enzymes, enolase (eno; Carneiro et al., 2004) and carbamate kinase (arc; Beenken et al., 2004; Diep et al., 2006; Diep and Otto, 2008), both of which exhibited half-lives of 30 min in wild type cells but only 15 min in ΔsarA cells. Likewise, the ATP-dependent protease clpP (Frees et al., 2003, 2005;Michel et al., 2006), exhibited a half-life of 15 min in wild type cells, but was reduced to five min in the sarA-mutant. During stationary phase growth at least 13 virulence factor transcripts were stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner (Table 4). Included among these were: spa (protein A), hla (α-hemolysin), hlb (β-hemolysin), and hlgCB (γ-hemolysin), as well as members of the capsule operon (cap) and the cell surface-associated factors fnbA (encoding fibronectin binding protein A) and cna (encoding a collagen-binding protein). Quantitative RT-PCR-based determination of select virulence factor half-lives within stationary phase wild type and ΔsarA cells verified the microarray-based RNA turnover measures (Table 5). In addition to virulence factors, three virulence factor regulatory molecules, agrA, sarS, and saeS, were stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner.

Table 4.

sarA-stabilized virulence-associated transcripts.

| Common name†‡ | Half-life* |

Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | ΔsarA | ||

| LATE-EXPONENTIAL | |||

| arcC | 30 min | 15 min | Carbamate kinase |

| clpP | 15 min | 5 min | ATP-dependent protease |

| eno | 30 min* | 15 min | Enolase |

| spa‡ | Stable* | Stable* | Protein A |

| STATIONARY | |||

| agrA | Stable* | 30 min | AgrAC TCRS response regulator |

| arcB | 15 min | 5 min | Ornithine carbamoyltransferase |

| cap5A | 5 min | 2.5 min | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis |

| cap5C | 15 min | 5 min | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis |

| cap5D | 15 min | 5 min | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis |

| cna | 15 min | 5 min | Collagen-binding protein |

| fnbA | 15 min | 5 min | Fibronectin binding protein A |

| hla‡ | Stable | 30 min | α-hemolysin |

| hlb | 30 min | 15 min | Phospholipase C |

| hlgB | 30 min | 15 min | γ hemolysin component B |

| hlgC | 15 min | 5 min | γ hemolysin component C |

| norA | 15 min | 5 min | Multi drug transporter |

| rsbV | 5 min | 2.5 min | Anti–anti-sigma factor |

| SACOL0390 | Stable | 30 min | Lipase |

| saeR | 15 min* | 5 min | SaeRS TCRS response regulator |

| sarV | 5 min | 2.5 min | SarA homolog |

| spa‡ | 30 min* | 15 min* | Protein A |

*Estimated half-life due to detection limits of the system.

†S. aureus strain N315 loci unless otherwise noted.

‡Transcript synthesis affected by sarA in UAMS-1 cells (Cassat et al., 2006).

Table 5.

Stationary phase mRNA half-lives of selected virulence factor transcripts as calculated by qRT-PCR*.

| Wild type† | ΔsarA† | |

|---|---|---|

| spa | ||

| 0 min | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5 min | 1.06 | 1.34 |

| 15 min | 1.22 | 1.63 |

| 30 min | 2.43 | 5.56 |

| 60 min | 2.47 | 11.28 |

| norA | ||

| 0 min | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5 min | 1.45 | 3.14 |

| 15 min | 2.20 | 3.22 |

| 30 min | 3.14 | 6.99 |

| 60 min | 3.20 | 5.38 |

| cna | ||

| 0 min | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5 min | 1.02 | 2.49 |

| 15 min | 2.68 | 2.07 |

| 30 min | 18.66 | 6.22 |

| 60 min | 83.91 | 35.33 |

*Time point corresponding to ≥ two-fold decrease (half-life) is shaded gray.

†Values represented as fold-change normalized to mRNA titers at 0 min.

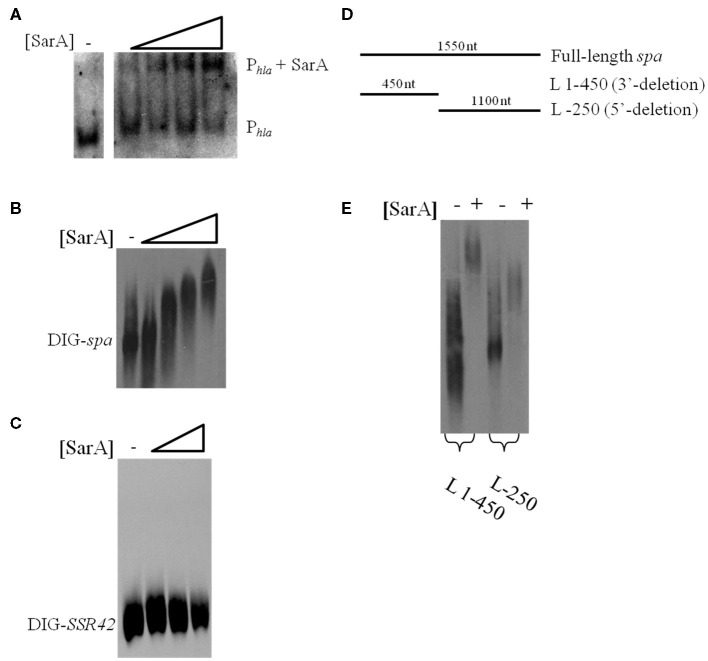

SarA binds mRNA in vitro

The results presented here are consistent with previous observations suggesting that the sarA locus affects S. aureus mRNA turnover properties with exponential phase cells (Roberts et al., 2006). The two most likely scenarios that could account for these observations are that a product of the sarA locus may directly interact with and subsequently affect the mRNA degradation properties of target transcripts or that SarA indirectly modulates the organism’s mRNA turnover properties by regulating other factors that affect S. aureus RNA decay. As a preliminary means of distinguishing between these two possibilities we set out to determine whether SarA is an RNA-binding protein. To do so, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed to investigate whether purified SarA protein directly binds to spa transcripts, an mRNA species that is stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner (Roberts et al., 2006). Accordingly, various amounts (0, 7.3, 36.6, 73.3, or 366.5 pmol) of purified SarA protein were incubated with DIG-labeled, in vitro transcribed spa mRNA, during experimental conditions that have previously been used to establish that SarA binds to the promoter region of the α-hemolysin (hla) gene (Chien et al., 1999). As shown in Figure 2A, during these assay conditions SarA protein did indeed bind to the hla promoter region, confirming that the experimental conditions are appropriate to measure SarA-nucleic acid interactions and further validating the work of Chien et al. (1999). Similarly, the EMSA revealed that SarA elicited a dose-dependent shift in mobility of labeled spa mRNA, suggesting that SarA may be capable of binding RNA molecules (Figure 2B). Gel-shift assays were also performed with BSA and a S. aureus stable RNA, SSR42 (Olson et al., 2011), to determine if non-staphylococcal proteins would bind to the in vitro transcribed mRNA and whether SarA alters the mobility of any RNA species, respectively. Results of those studies indicated that BSA did not affect the mobility of spa transcript and, likewise, that SarA did not affect the migration of in vitro transcribed SSR42 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

SarA binds mRNA in vitro. (A) Gel mobility shift assays evaluating the mobility of DIG-labeled hla promoter DNA (Phla) in the presence of increasing amounts of purified SarA protein (0, 7.3, 36.6, 73.3, or 366.5 pmol). (B) Gel mobility shift assays evaluating the mobility of DIG-labeled, in vitro transcribed spa in the presence of increasing concentrations of SarA protein (0, 7.3, 36.6, 73.3, or 366.5 pmol). (C) Gel mobility shift assays evaluating the mobility of DIG-labeled, in vitro transcribed SSR42 in the presence of increasing concentrations of SarA protein (0, 36.6, 73.3, or 366.5 pmol). (D) Schematic of transcript variants containing deletions of 3′ or 5′ regions of spa that were DIG-labeled for use in subsequent gel-shift assays. (E) Gel mobility shift assays evaluating the mobility DIG-labeled spa deletion variants in the presence of 73.3 pmol SarA.

RNA-binding proteins have been shown to bind to specific regions of target mRNAs (Folichon et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2005); to test this possibility with SarA, we used EMSAs to measure the protein’s ability to bind different regions of in vitro transcribed spa mRNA: a region lacking bases 1–320 of the 5′ end (L-250) and a fragment of spa containing only bases 1–450 (L 1–450; Figure 2D). As seen in Figure 2E, SarA affected the mobility of both RNA species. Further, a higher molecular weight product was observed when SarA was incubated with spa RNA fragments containing an intact 5′region (450 nt) in comparison to fragments lacking bases 1–250 of the transcript (1,100 nt), suggesting that the 5′ end of the spa transcript may harbor a greater number of SarA-binding sites than the 3′ terminus. Taken together, these results suggest that SarA may be capable of binding both DNA and RNA molecules.

SarA binds mRNA in vivo

Based on the observations that many exponential phase transcripts, including spa, are stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner and that SarA protein is capable of altering the mobility of spa transcripts in vitro, we set out to determine whether the protein is capable of binding mRNA species within bacterial cells using ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation-microarray (RIP-Chip) assays. To do so, we needed to create a means of capturing cellular SarA protein. Accordingly, the SarA open reading frame was translationally fused to a C-terminal c-Myc epitope. This construct was placed under control of the sarA endogenous P1 promoter and was inserted into plasmid pCN51 to generate pKLA40. This plasmid was transfected into UAMS-929 (ΔsarA) cells to generate strain KLA43 and the expression properties of C-Myc-SarA protein were evaluated. It should be noted that the c-Myc epitope has been shown to exhibit little or no non-specific nucleic acid binding in previous assays (Pannone et al., 1998). As expected, RT-PCR and Western blotting using anti-c-Myc antibodies established that the chimeric protein was expressed within KLA43 cells (Figures 3A,B) during mid- and late-exponential as well as stationary phase growth. We also confirmed that c-Myc-SarA was capable of complementing SarA’s regulatory effects within ΔsarA cells. Specifically, sarA-mutant cells have been reported as exhibiting altered exprotein profiles due to alterations in the control of gene expression (Tegmark et al., 2000). Thus, we evaluated the ability of the c-Myc-SarA construct to complement the exoprotein profile of supernates from stationary phase cultures of S. aureus strain UAMS-929 (ΔsarA). As shown in Figure 3C, the c-Myc-SarA construct at least partially complemented the exoprotein profile of ΔsarA cells, indicating that presence of the epitope did not significantly affect SarA’s regulatory capacity and, consequently, the chimeric protein was appropriate for studying SarA’s cellular role as an RNA-binding protein.

Figure 3.

SarA binds mRNA in vivo. (A) RT-PCR based detection of c-Myc-SarA transcript expression in ΔsarA and ΔsarA harboring plasmid pKLA40 harboring a c-Myc-SarA construct under control of the sarA P1 promoter during mid-exponential (ME), late-exponential (LE), and stationary (SP) phase growth. (B) Western blotting based detection of c-Myc-SarA chimeric protein from sarA and ΔsarA harboring plasmid pKLA40; lysates collected during mid-exponential (ME), late-exponential (LE), and stationary (SP) phase growth. (C) SDS-PAGE and silver staining of exoproteins purified from wild type, ΔsarA and ΔsarA harboring plasmid pKLA40 stationary phase culture supernates. (D) RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) was performed by capturing c-Myc-SarA protein cross-linked to nucleic acids. Successful immunoprecipitation was confirmed by Western blotting of cell lysate (L), lysate supernate (SN), wash (W), and elution (E) fractions with anti-c-Myc antibody.

Having confirmed that the chimeric protein was expressed and functional within ΔsarA cells, RIP-chIP assays were performed using anti-c-Myc immunoglobulin immobilized on agarose beads to capture cellular c-Myc-SarA-bound transcripts. To do so, KLA43 (ΔsarA c-Myc-SarA) was grown to mid-exponential phase and the proteins were cross-linked to nucleic acids with 1% formaldehyde to stabilize any interactions between c-Myc-SarA and RNA molecules. Cells were lysed and c-Myc-SarA protein was then immunoprecipitated with the anti-c-Myc agarose beads, co-precipitating any bound RNA species. Western blotting of the cell lysates and RIP intermediates indicated the presence of the epitope-labeled SarA through sequential steps of the IP process (Figure 3D). After reversal of the RNA cross-linking, the RNA was purified, treated with DNase, amplified, labeled, and applied to a S. aureus GeneChip®. All RIP-Chip assays were performed in triplicate for both KLA43 (ΔsarA c-Myc-SarA) and ΔsarA cells (negative control). A transcript was considered to be bound by c-Myc-SarA if its average signal intensity value was ≥ two-fold in KLA43 cells as compared to the negative control. It should be noted that as a prerequisite to performing RIP-Chip assays we exploited SarA’s known ability to bind the hla promoter region and the fact that the microarray used in this study contains intergenic regions representing gene promoters to determine whether our experimental approach was appropriate for studying cellular SarA-nucleic acid interactions. Results from ChIP-chip experiments revealed that the signal intensity of the intergenic region representing the hla promoter region exhibited a signal increase beyond the established threshold (≥ two-fold) in samples from KLA43 cells as compared to UAMS-929 cells, indicating that the experimental approach was capable of detecting known in vitro protein-nucleic acid reactions in vivo (data not shown).

RIP-Chip assays results indicated that cellular c-Myc-SarA is capable of binding to a total of 115 RNA species, including eight virulence factor transcripts (Supplemental Table S5 in Supplementary Material). Of the virulence factor transcripts bound by SarA (Table 6), spa and arcB were also stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner in at least one of the growth phases studied here (late-log and stationary phase) or by our laboratory previously (mid-exponential phase; Roberts et al., 2006). Thus, our collective results indicate that spa mRNA is stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner (Roberts et al., 2006) and that SarA protein is capable of binding the transcript during in vitro conditions and within bacterial cells. When taken together, these results suggest that SarA may post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by binding to and modulating the RNA degradation properties of target transcripts.

Table 6.

Virulence-associated transcripts bound by cellular c-Myc-SarA.

| Common name* | Fold change† | mRNA stability‡ | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| arcB | 8.3 | Stabilized | Ornithine carbamoyltransferase |

| pfoR | 3.7 | Destabilized | Perfringolysin O regulator protein |

| rsbW | 7.6 | Anti-sigma B factor | |

| SA0097 | 8.3 | Destabilized | Transcriptional regulator AraC/XylS family |

| sarZ | 2.7 | SarA homolog | |

| sbi | 3.3 | Destabilized | IgG-binding protein |

| spa | 4.2 | Stabilized | IgG-binding protein A |

| srtA | 7.4 | Sortase |

*S. aureus strain N315 locus.

†Fold change of signal intensities present in c-Myc-SarA samples in comparison to ΔsarA samples (p < 0.05).

‡Effect of sarA on transcript turnover.

Discussion

Staphylococci produce an array of TCRS and DNA-binding proteins that are thought to modulate virulence factor transcript synthesis, providing the pathogen with a means for sensing and responding to environmental stresses including exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics (Novick, 2003). By definition, transcript titers are a function of both transcript synthesis and degradation, and mounting evidence strongly suggests that orchestrated changes in mRNA degradation mediate the organism’s ability to regulate gene expression. Indeed, the global mRNA degradation properties of S. aureus are significantly altered in response to growth phase, stringent response-inducing conditions, and pH and temperature stress (Anderson et al., 2006, 2010;Olson et al., 2011). With respect to growth phase, RNA turnover is rapid in exponential phase cells whereas a global stabilization of RNA transcripts occurs during stationary phase growth; ∼90% of transcripts decay within 5 min during mid-exponential growth while only ∼50% of all transcripts decay within 5 min during stationary phase growth (Olson et al., 2011). Presently, the factors that mediate this transition between RNA degradation profiles are poorly characterized. Because all transcripts do not degrade at the same rate, it has been hypothesized that trans-acting factors, such as RNA-binding proteins or regulatory RNAs, may affect mRNA stability. Indeed, the mRNA turnover properties of nearly 150 exponential phase mRNA species, including the cell surface-associated virulence factors spa and cna, have been reported to be stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner (Roberts et al., 2006). However, those studies were limited in scope, in that the effects of sarA on RNA stability were only studied within mid-exponential phase cells. In the present work, we evaluated the effects of sarA on late-exponential and stationary phase RNA turnover.

A comparison of mRNA turnover within wild type and ΔsarA cells indicated that global RNA decay is similar between the two strains; mRNA is rapidly degraded in late-exponential phase cells but transcripts become more stable during stationary phase growth. Despite these similarities, transcript turnover within each growth phase was slightly decreased in ΔsarA cells indicating that a product of the sarA locus affects the stability of a subset of mRNA species. Indeed, sarA was found to both stabilize and destabilize transcripts in each growth phase; 3.4 and 16.5% of transcripts were stabilized, whereas 16.4 and 23.5% of transcripts were destabilized in a sarA-dependent manner within late-exponential and stationary phase cells, respectively. Among the stabilized transcripts were those encoding for translation machinery, suggesting that sarA may modulate protein production indirectly by post-transcriptionally altering expression of the translation apparatus. Perhaps more relevant to S. aureus pathogenesis, 19 virulence-associated factors were stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner, including cell surface components, secreted enzymes and toxins, transcriptional regulators, and antibiotic resistance determinants. Interestingly, a subset of these virulence factors, including spa, hla, sak, and sspB have been previously shown to be regulated by sarA at the transcriptional level (Cassat et al., 2006). These results suggest that the effects of sarA on gene regulation in S. aureus may be more complex than previously thought, and that a product of the locus may post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression.

The sarA locus is capable of producing three distinct transcripts, each of which encode for and result in the production of SarA protein. Thus, any potential post-transcriptional regulation could occur via the SarA protein or via one of the transcribed mRNAs as has been described with other regulatory RNAs in S. aureus (reviewed in Felden et al., 2011). The mRNA turnover properties of ΔsarA cells harboring plasmid-borne copies each of these three transcriptional units demonstrated that their RNA degradation properties mimicked one-another, suggesting that the SarA protein (as opposed to a particular sarA transcriptional unit) accounts for the sarA-dependent modulation of mRNA turnover (data not shown). Thus, we predicted that SarA directly or indirectly affects the RNA degradation properties of target transcripts. Accordingly, gel-shift assays were performed to determine whether SarA protein directly binds to spa mRNA in vitro, a transcript that is stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner. EMSA results revealed that SarA alters the mobility of spa mRNA in a concentration-dependent manner, suggesting that the protein is capable of binding the transcript in a cooperative manner. We hypothesize that this may reflect two potential dynamic properties of the interaction: (1) SarA oligomerizes when binding RNA or (2) the spa transcript contains multiple SarA-binding sites such that in the presence of excess SarA the number of sites bound by the protein are increased. Further, gel-shift assays indicated that SarA exhibits a greater propensity to cause a higher molecular shift of the 5′-end of spa mRNA, suggesting that either the 5′ end of the message harbors a higher incidence of SarA-binding sites or that the secondary structure of the transcript’s 5′ end reduces the amount of steric hindrance. Regardless, we conclude from the results of these assays suggest that the SarA-mRNA interaction is not likely to be equal across the entire length of the spa transcript.

In order to characterize the physiological relevance of SarA’s potential RNA-binding properties, we performed in vivo RIP-chIP assays to identify the transcripts with which the protein could interact within bacterial cells. To do so, c-Myc epitope-tagged SarA was expressed in ΔsarA cells and immunoprecipitated; c-Myc-SarA-bound RNA molecules were subsequently identified using GeneChips®. In total, SarA was found to interact with 115 mRNA species, including eight virulence factors. Specifically, two of the virulence factor transcripts that bound to SarA in vivo were also found to be stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner, including the spa transcript, an mRNA species that SarA appears to bind in vitro. Taken together, these data suggest that SarA may alter the stability of target transcripts by directly binding to these mRNA species, which could, in-turn, limit the RNA molecule’s accessibility to degradation machinery. Additionally, SarA also interacted with three transcripts that are destabilized in a sarA-dependent manner, suggesting that the protein:mRNA interaction may catalyze a conformational change in the substrate RNA molecule that makes it more susceptible to ribonuclease attack. In addition to ORFs, SarA also bound five transcripts that mapped to intergenic regions and may represent non-coding RNA molecules.

Collectively, the data presented here indicate that SarA interacts with RNA in a biologically relevant setting and that these interactions correlate with alterations in the degradation properties of a subset of those mRNA species. Thus, we hypothesize that SarA post-transcriptionally regulates gene expression via binding to and consequently modulating the mRNA turnover properties of target transcripts. There is precedence for this prediction in other organisms. For instance, in Escherichia coli, CsrA is an RNA-binding protein that modulates virulence factor expression, in part, by both stabilizing and destabilizing target transcripts. For instance, CsrA associates with the 5′ untranslated region of the pgaA transcript, which blocks translation of the molecule and subsequently destabilizes the transcript (Wang et al., 2005). CsrA has also been shown to bind the flhDC transcript, stabilizing the molecule and ultimately contributes to bacterial motility (Wei et al., 2001). Given the similarities of CsrA and other RNA-binding proteins to SarA, scenarios by which SarA can post-transcriptionally modulate gene expression emerge. In the case of spa, whose transcript is stabilized but protein production is repressed by SarA, binding of the RNA may simultaneously inhibit activity of the translational machinery and ribonucleases (RNases). This mechanism would presumably provide the cell with a mechanism to repress protein A production, in a manner that when inactivated would allow for efficient induction of Spa production without having to expend energy to synthesize new transcripts. Our finding that SarA seems to preferentially interact with the 5′ terminus of the spa transcripts supports this prediction, as the 5′end of mRNA not only serves as a potential entry point for the RNA degradation machinery, it is also the loading site for the translation apparatus. Similarly, the binding of SarA to transcripts which are normally stabilized and for which protein levels are increased, SarA could function by inhibiting degradation of the transcript by RNases, thus facilitating increased production of protein. As what occurs with CsrA, SarA also destabilizes transcripts that it binds in vivo, suggesting that this interaction could expose transcripts to cleavage by RNases. It was also observed that virulence factor transcripts that were stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner were not bound by SarA in vivo (Supplemental Table S5 in Supplementary Material). Thus, one can assume that the modulation of RNA stability of these transcripts is indirect; presumably, SarA regulates another factor, such as a regulatory RNA or other RNA-binding protein, which ultimately mediates the alteration in stability. While the biological significance of sarA-dependent control of mRNA stability is not yet fully understood, these results indicate that SarA is an RNA-binding protein with the potential to post-transcriptionally regulate the mRNA and consequently protein production of target transcripts. These results may have expanded significance in that SarA represents a prototypical regulatory molecule with a multitude of homologs within S. aureus and other bacterial pathogens.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/Cellular_and_Infection_Microbiology/10.3389/fcimb.2012.00026/abstract

Late-exponential phase transcripts stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner.

Stationary phase transcripts stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner.

Late-exponential phase transcripts destabilized in a sarA-dependent manner.

Stationary phase transcripts destabilized in a sarA-dependent manner.

Mid-exponential growth phase transcripts bound by SarA in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI073780 (Paul M. Dunman). John Morrison was supported by American Heart Association predoctoral award 11PRE7420020. We thank Barry Hurlburt for purified SarA protein used in the gel-shift assays.

References

- Anderson K. L., Roberts C., Disz T., Vonstein V., Hwang K., Overbeek R., Olson P. D., Projan S. J., Dunman P. M. (2006). Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus heat shock, cold shock, stringent, and SOS responses and their effects on log-phase mRNA turnover. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6739–6756 10.1128/JB.00609-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. L., Roux C. M., Olson M. W., Luong T. T., Lee C. Y., Olson R., Dunman P. M. (2010). Characterizing the effects of inorganic acid and alkaline shock on the Staphylococcus aureus transcriptome and messenger RNA turnover. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 60, 208–250 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00736.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balandina A., Claret L., Hengge-Aronis R., Rouviere-Yaniv J. (2001). The Escherichia coli histone-like protein HU regulates rpoS translation. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 1069–1079 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenken K. E., Dunman P. M., Mcaleese F., Macapagal D., Murphy E., Projan S. J., Blevins J. S., Smeltzer M. S. (2004). Global gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 186, 4665–4684 10.1128/JB.186.14.4665-4684.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins J. S., Gillaspy A. F., Rechtin T. M., Hurlburt B. K., Smeltzer M. S. (1999). The Staphylococcal accessory regulator (sar) represses transcription of the Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin gene (cna) in an agr-independent manner. Mol. Microbiol. 33, 317–326 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01475.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisset S., Geissmann T., Huntzinger E., Fechter P., Bendridi N., Possedko M., Chevalier C., Helfer A. C., Benito Y., Jacquier A., Gaspin C., Vandenesch F., Romby P. (2007). Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII coordinately represses the synthesis of virulence factors and the transcription regulator Rot by an antisense mechanism. Genes Dev. 21, 1353–1366 10.1101/gad.423507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brescia C. C., Kaw M. K., Sledjeski D. D. (2004). The DNA binding protein H-NS binds to and alters the stability of RNA in vitro and in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 339, 505–514 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner S., Monteil H., Prevost G. (2004). Regulation of virulence determinants in Staphylococcus aureus: complexity and applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28, 183–200 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro C. R., Postol E., Nomizo R., Reis L. F., Brentani R. R. (2004). Identification of enolase as a laminin-binding protein on the surface of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbes Infect. 6, 604–608 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassat J., Dunman P. M., Murphy E., Projan S. J., Beenken K. E., Palm K. J., Yang S. J., Rice K. C., Bayles K. W., Smeltzer M. S. (2006). Transcriptional profiling of a Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolate and its isogenic agr and sarA mutants reveals global differences in comparison to the laboratory strain RN6390. Microbiology 152, 3075–3090 10.1099/mic.0.29033-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassat J. E., Dunman P. M., Mcaleese F., Murphy E., Projan S. J., Smeltzer M. S. (2005). Comparative genomics of Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal isolates. J. Bacteriol. 187, 576–592 10.1128/JB.187.2.576-592.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier E., Anton A. I., Barry P., Alfonso B., Fang Y., Novick R. P. (2004). Novel cassette-based shuttle vector system for gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 6076–6085 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6076-6085.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier C., Boisset S., Romilly C., Masquida B., Fechter P., Geissmann T., Vandenesch F., Romby P. (2010). Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII binds to two distant regions of coa mRNA to arrest translation and promote mRNA degradation. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000809. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien Y., Cheung A. L. (1998). Molecular interactions between two global regulators, sar and agr, in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2645–2652 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien Y., Manna A. C., Projan S. J., Cheung A. L. (1999). SarA, a global regulator of virulence determinants in Staphylococcus aureus, binds to a conserved motif essential for sar-dependent gene regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37169–37176 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Azavedo J. C., Foster T. J., Hartigan P. J., Arbuthnott J. P., O’reilly M., Kreiswirth B. N., Novick R. P. (1985). Expression of the cloned toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 gene (tst) in vivo with a rabbit uterine model. Infect. Immun. 50, 304–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleo F. R., Otto M., Kreiswirth B. N., Chambers H. F. (2010). Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 375, 1557–1568 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61999-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep B. A., Gill S. R., Chang R. F., Phan T. H., Chen J. H., Davidson M. G., Lin F., Lin J., Carleton H. A., Mongodin E. F., Sensabaugh G. F., Perdreau-Remington F. (2006). Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 367, 731–739 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep B. A., Otto M. (2008). The role of virulence determinants in community-associated MRSA pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 16, 361–369 10.1016/j.tim.2008.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felden B., Vandenesch F., Bouloc P., Romby P. (2011). The staphylococcus aureus RNome and its commitment to virulence. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002006. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folichon M., Arluison V., Pellegrini O., Huntzinger E., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E. (2003). The poly(A) binding protein Hfq protects RNA from RNase E and exoribonucleolytic degradation. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 7302–7310 10.1093/nar/gkg915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frees D., Qazi S. N., Hill P. J., Ingmer H. (2003). Alternative roles of ClpX and ClpP in Staphylococcus aureus stress tolerance and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 1565–1578 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03524.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frees D., Sorensen K., Ingmer H. (2005). Global virulence regulation in Staphylococcus aureus: pinpointing the roles of ClpP and ClpX in the sar/agr regulatory network. Infect. Immun. 73, 8100–8108 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8100-8108.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisinger E., Adhikari R. P., Jin R., Ross H. F., Novick R. P. (2006). Inhibition of rot translation by RNAIII, a key feature of agr function. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 1038–1048 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05292.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillaspy A. F., Hickmon S. G., Skinner R. A., Thomas J. R., Nelson C. L., Smeltzer M. S. (1995). Role of the accessory gene regulator (agr) in pathogenesis of staphylococcal osteomyelitis. Infect. Immun. 63, 3373–3380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger E., Boisset S., Saveanu C., Benito Y., Geissmann T., Namane A., Lina G., Etienne J., Ehresmann B., Ehresmann C., Jacquier A., Vandenesch F., Romby P. (2005). Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII and the endoribonuclease III coordinately regulate spa gene expression. EMBO J. 24, 824–835 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens R. M., Morrison M. A., Nadle J., Petit S., Gershman K., Ray S., Harrison L. H., Lynfield R., Dumyati G., Townes J. M., Craig A. S., Zell E. R., Fosheim G. E., Mcdougal L. K., Carey R. B., Fridkin S. K. (2007). Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 298, 1763–1771 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna A. C., Bayer M. G., Cheung A. L. (1998). Transcriptional analysis of different promoters in the sar locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 180, 3828–3836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel A., Agerer F., Hauck C. R., Herrmann M., Ullrich J., Hacker J., Ohlsen K. (2006). Global regulatory impact of ClpP protease of Staphylococcus aureus on regulons involved in virulence, oxidative stress response, autolysis, and DNA repair. J. Bacteriol. 188, 5783–5796 10.1128/JB.00074-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morfeldt E., Taylor D., Von Gabain A., Arvidson S. (1995). Activation of alpha-toxin translation in Staphylococcus aureus by the trans-encoded antisense RNA, RNAIII. EMBO J. 14, 4569–4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick R. P. (2003). Autoinduction and signal transduction in the regulation of staphylococcal virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 1429–1449 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03526.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson P. D., Kuechenmeister L. J., Anderson K. L., Daily S., Beenken K. E., Roux C. M., Reniere M. L., Lewis T. L., Weiss W. J., Pulse M., Nguyen P., Simecka J. W., Morrison J. M., Sayood K., Asojo O. A., Smeltzer M. S., Skaar E. P., Dunman P. M. (2011). Small molecule inhibitors of Staphylococcus aureus RnpA alter cellular mRNA turnover, exhibit antimicrobial activity, and attenuate pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1001287. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannone B. K., Xue D., Wolin S. L. (1998). A role for the yeast La protein in U6 snRNP assembly: evidence that the La protein is a molecular chaperone for RNA polymerase III transcripts. EMBO J. 17, 7442–7453 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C., Anderson K. L., Murphy E., Projan S. J., Mounts W., Hurlburt B., Smeltzer M., Overbeek R., Disz T., Dunman P. M. (2006). Characterizing the effect of the Staphylococcus aureus virulence factor regulator, SarA, on log-phase mRNA half-lives. J. Bacteriol. 188, 2593–2603 10.1128/JB.188.7.2593-2603.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M. A., Hurlburt B. K., Brennan R. G. (2001). Crystal structures of SarA, a pleiotropic regulator of virulence genes in S. aureus. Nature 409, 215–219 10.1038/35051623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selinger D. W., Saxena R. M., Cheung K. J., Church G. M., Rosenow C. (2003). Global RNA half-life analysis in Escherichia coli reveals positional patterns of transcript degradation. Genome Res. 13, 216–223 10.1101/gr.912603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterba K. M., Mackintosh S. G., Blevins J. S., Hurlburt B. K., Smeltzer M. S. (2003). Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus SarA binding sites. J. Bacteriol. 185, 4410–4417 10.1128/JB.185.15.4410-4417.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegmark K., Karlsson A., Arvidson S. (2000). Identification and characterization of SarH1, a new global regulator of virulence gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 37, 398–409 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Dubey A. K., Suzuki K., Baker C. S., Babitzke P., Romeo T. (2005). CsrA post-transcriptionally represses pgaABCD, responsible for synthesis of a biofilm polysaccharide adhesin of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 1648–1663 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04648.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei B. L., Brun-Zinkernagel A. M., Simecka J. W., Pruss B. M., Babitzke P., Romeo T. (2001). Positive regulation of motility and flhDC expression by the RNA-binding protein CsrA of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 245–256 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02380.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Late-exponential phase transcripts stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner.

Stationary phase transcripts stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner.

Late-exponential phase transcripts destabilized in a sarA-dependent manner.

Stationary phase transcripts destabilized in a sarA-dependent manner.

Mid-exponential growth phase transcripts bound by SarA in vivo.