Abstract

The genetics of the mating-type (MAT) locus have been studied extensively in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, but relatively little is known about how this complex system evolved. We compared the organization of MAT and mating-type-like (MTL) loci in nine species spanning the hemiascomycete phylogenetic tree. We inferred that the system evolved in a two-step process in which silent HMR/HML cassettes appeared, followed by acquisition of the Ho endonuclease from a mobile genetic element. Ho-mediated switching between an active MAT locus and silent cassettes exists only in the Saccharomyces sensu stricto group and their closest relatives: Candida glabrata, Kluyveromyces delphensis, and Saccharomyces castellii. We identified C. glabrata MTL1 as the ortholog of the MAT locus of K. delphensis and show that switching between C. glabrata MTL1a and MTL1α genotypes occurs in vivo. The more distantly related species Kluyveromyces lactis has silent cassettes but switches mating type without the aid of Ho endonuclease. Very distantly related species such as Candida albicans and Yarrowia lipolytica do not have silent cassettes. In Pichia angusta, a homothallic species, we found MATα2, MATα1, and MATa1 genes adjacent to each other on the same chromosome. Although some continuity in the chromosomal location of the MAT locus can be traced throughout hemiascomycete evolution and even to Neurospora, the gene content of the locus has changed with the loss of an HMG domain gene (MATa2) from the MATa idiomorph shortly after HO was recruited.

Mating in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a choreographed fusion of two haploid cells with opposite mating types to form a diploid zygote. The mating type of a haploid cell is determined by its genotype at the mating-type (MAT) locus on chromosome III. The two variants of the MAT locus, MATα and MATa, are referred to as idiomorphs rather than alleles because they differ in sequence, size, and gene content (1). Characterization of homothallic and heterothallic strains of S. cerevisiae by Winge and Lindegren (2) led to the discovery of genetic loci controlling homothallism and ultimately to the cassette model of mating-type switching proposed by Herskowitz and colleagues (3). The cassette model, which has been thoroughly verified by experimentation (4, 5), states that a haploid cell can switch genotype at the MAT locus (from MATa to MATα or vice versa) by a gene-conversion process that involves replacing the genetic information at MAT with information copied from one of two silent cassette loci, HMLα or HMRa. The gene conversion is initiated at a double-stranded DNA break made by the Ho endonuclease, encoded by the HO gene on chromosome IV, which cuts at a site that marks the boundary between the Y sequences unique to the MATa or MATα idiomorphs and the shared Z sequence flanking them. HO is expressed only in cells that have budded once, which means that only mother cells switch mating type and neighboring cells in a colony can mate (4). Hence, most natural isolates of S. cerevisiae are diploid and phenotypically homothallic.

The focus on S. cerevisiae as a model organism has had the consequence that relatively little investigation has been made into the mating systems of other species in the hemiascomycetes, the group of fungi that includes Saccharomyces. The question of whether a mating-type system similar to that of S. cerevisiae is found in other hemiascomycetes has become pertinent recently because of the discovery of mating-type-like (MTL) loci in Candida species that had been regarded as asexual (6-9). The Candida albicans genome sequence (10) includes an MTL locus but not silent cassettes or a HO endonuclease gene. In Candida glabrata, three MTL loci (MTL1-3) were reported (9). Here we have used a genomics approach to study the organization and evolution of the MAT locus in nine hemiascomycete species. By combining our sequence data with information from previous reports and genome projects, we show that the Ho endonuclease was a relatively recent addition to a preexisting, cassette-based switching system, which in turn evolved from a simpler system without cassettes. The genomic structures are consistent with what is known about the genetics of mating-type switching and homo- and heterothallism in each species.

Methods

C. glabrata strain RND13 was generously provided by R. Ueno and N. Urano (Tokyo University of Fisheries, Tokyo) (11, 12). Although initially characterized as Torulaspora delbrueckii (11), strain RND13 has an 18S rDNA sequence (12) with only four differences from that of the type strain CBS 138 of C. glabrata, which we suspected could be sequencing errors. We amplified and sequenced the variable D1/D2 domain of 26S rDNA from RND13 using primers NL-1 and NL-4 (primer sequences are listed in Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and found only 1 nucleotide difference of 581 between it and CBS 138, which is within the normal range of intraspecies variation (13). Similarly, only 5 of 1,398 and 0 of 420 nucleotides differed between RND13 and CBS 138 in the regions we sequenced to the left and right, respectively, of MTL1; this level of difference is as low as that seen among clinical isolates of C. glabrata (9).

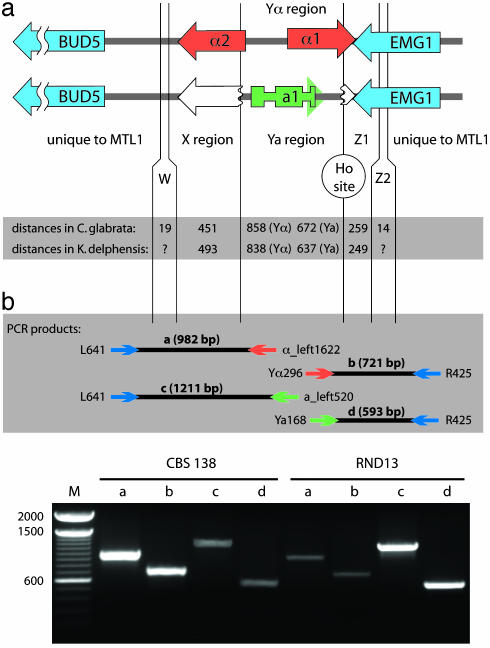

C. glabrata strain CBS 138 MTLa sequence information was obtained from a PCR product amplified from the MTL2a cassette by using primers X1 and Z1 (Table 1). Testing for MTL1 genotype switching in C. glabrata was done by PCR amplification and sequencing across both the Y/Z1 and X/Y junctions of MTL1 (Fig. 1). At the Y/Z1 junction we used common primers from the EMG1 gene with either MTL1α- or MTL1a-specific rightward primers. At the X/Y junction we used common primers from the region upstream of BUD5 with MTL1α- or MTL1a-specific leftward primers. As described in Table 2 (which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), “switched” PCR products were detected from both RND13 and CBS 138 in amplifications across both the X/Y and Y/Z1 junctions. The sequences of switched PCR products were verified at the X/Y and Y/Z1 junctions from RND13 and at the Y/Z1 junction from CBS 138. In the sequenced region between BUD5 and the X/Y junction, there were five nucleotide differences between strains RND13 and CBS 138 that served to show that contamination did not occur during PCR amplification.

Fig. 1.

(a) Organization of the α and a idiomorphs of the C. glabrata MTL1 and K. delphensis MAT loci. The organization is identical in the two species. The a1 gene has three exons. Broken open arrows denote truncated copies of the 3′ ends of the α2 and α1 genes present in the a idiomorphs. W, X, Z1, and Z2 indicate regions shared with silent cassettes. (b) PCR amplification of idiomorph-specific products from C. glabrata strains CBS 138 and RND13. Shown are idiomorph-specific primer pair combinations as diagrammed in Upper (lanes CBS 138 a-d and RND13 a-d); lanes 2-fold overloaded compared with the others (lanes CBS 138 c and d and RND13 a and b); and a size standard (lane M).

The C. glabrata and Kluyveromyces delphensis HO genes were sequenced from genomic plasmid clones CG3380 and KD0425 (8). A K. delphensis HMRa-like cassette was sequenced from plasmid KD1818 (8). The MATB idiomorph of Yarrowia lipolytica was cloned by PCR using sequences from the flanking genes as primers. We sequenced loci in other species from Génolevures plasmids BA0AB039C05, BA0AB024C06, BB0AA018C05, BB0AA019A10, AR0AA031F11, and AZ0AA005C07 (14). Additional Zygosaccharomyces rouxii information was obtained from a random sequencing project similar to that described in ref. 8 (J. Gordon and K.H.W., unpublished data).

Results and Discussion

C. glabrata MTL1 and K. delphensis MAT Loci and Their Ho Endonucleases. We previously reported sequences of a putative MAT locus from C. glabrata and its close relative K. delphensis containing homologs of the S. cerevisiae MATα1 and MATα2 genes (8). Srikantha et al. (9) independently identified three MTL loci in C. glabrata, one of which (MTL1) corresponds to the locus we described. They found both MTL1α and MTL1a isolates of C. glabrata, which is haploid. In 36 of the 39 isolates that they examined (classes I and II), the MTL genotypes were consistent with the designation of MTL1 as the mating-type locus and MTL2a and MTL3α as silent cassettes similar to HMRa and HMLα of S. cerevisiae. However, Srikantha et al. (9) reported that the MTL1a1 gene has no start codon.

We verified that the K. delphensis MTL1 ortholog is its MAT locus. From our random K. delphensis genomic library (8) we identified five more plasmids whose insert end sequences indicated that they span the locus. Three plasmids contained the MATα1 and MATα2 genes as reported (8), and the other two contained a homolog of S. cerevisiae MATa1 (Fig. 1a). The mating-type-specific segments in K. delphensis are 838 and 637 bp for the K. delphensis MATα and MATa idiomorphs, respectively. Given the large sizes of the plasmid inserts (7.2-11.3 kb), we can be certain that they are derived from the MAT locus and not from silent cassettes. This indicates that K. delphensis strain CBS 2170 is a MATα/MATa diploid and that its MAT locus is orthologous to C. glabrata MTL1.

The C. glabrata type strain CBS 138 (ATCC no. 2001) has an MTL1α genotype (8). By PCR amplification using primers from the presumed X and Z1 regions flanking MTL1, which are expected also to flank any silent cassettes, we obtained two products, one with MTLα information (from an MTL1α or MTL3α template) and one with MTLa information (from an MTL2a template). Comparison of the C. glabrata MTLa and K. delphensis MATa sequences showed that the a1 gene in each species contains two introns and has a normal start codon (Fig. 1a and see Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

The boundary between the Y and Z1 regions, where sequences unique to the α or a idiomorphs meet common flanking sequence, is formed by a putative cleavage site for the Ho endonuclease in both K. delphensis and C. glabrata. The first bases of the Z1 region have the canonical Ho site sequence CGCAAC in K. delphensis MATα and MATa and C. glabrata MTL1a. In C. glabrata MTL1α it is altered to CGCAGC, but this sequence also has been shown to be cleaved efficiently by the S. cerevisiae Ho endonuclease in vivo (15). These observations suggested that C. glabrata and K. delphensis have HO endonuclease genes. We found these genes by using comparative gene order information to walk from neighboring genes we had identified from genome survey sequencing (8) (Fig. 2). The predicted C. glabrata and K. delphensis Ho proteins have 68% sequence identity to each other and 57% identity to S. cerevisiae Ho protein and show conservation of the two LAGLIDADG endonuclease motifs and the Gly-223 residue identified as essential for mating-type switching in S. cerevisiae (16).

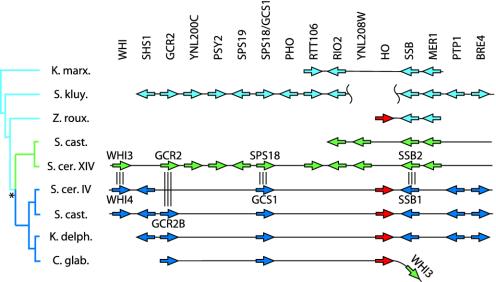

Fig. 2.

Gene organization around the HO locus in yeast species. Homologous gene groups are aligned vertically. Triple vertical lines indicate duplicated gene pairs. The phylogenetic tree on the left shows the evolutionary relationships among sequences, with the genome duplication event (asterisk) resulting in two descendant lineages in some species. Green, lineages and genes orthologous to S. cerevisiae chromosome XIV; dark blue, orthologs of chromosome IV. The extent of sequence data available for each species is shown by black horizontal lines. Data for Saccharomyces castellii and Saccharomyces kluyveri are from ref. 18 (GenBank accession nos. AACE01000158, AACE01000109, AACF01000039, and AACF01000107). K. marx., Kluyveromyces marxianus; S. kluy., S. kluyveri; Z. roux., Z. rouxii; S. cast., S. castellii; S. cer. XIV, S. cerevisiae chromosome XIV; S. cer. IV, S. cerevisiae chromosome IV; K. delph., K. delphensis; C. glab, C. glabrata.

To investigate whether switching of the MTL1 genotype occurs in C. glabrata, we used an environmental isolate, RND13 (with the MTL1a genotype), as well as the type strain CBS 138 (MTL1α). RND13 was isolated recently from hot spring drainage water (40°C) and has been phenotypically characterized (11, 12). PCR amplification using one primer specific to Yα or Ya together with a primer from common flanking sequence (Fig. 1b) was used to test for MTL1 genotype switching. The flanking primers lie outside the W and Z2 regions shared with the MTL2 and MTL3 cassettes (9) and so will amplify a product only from the MTL1 locus. The RND13 isolate consistently yielded a strong PCR product with MTL1a-specific primers and a weaker product with MTL1α-specific primers (Fig. 1b). This result was seen in amplifications with several different primer combinations and with four independent DNA preparations from RND13 (Table 2). The structures of PCR products from RND13 spanning the X/Y and Y/Z1 junctions in MTL1α (switched) and MTL1a (unswitched) forms were confirmed by sequencing. Similarly, we obtained strong MTL1α and weak MTL1a PCR products from CBS 138 (Fig. 1b), and we verified the MTL1a Y/Z1 junction product by sequencing. In both CBS 138 and RND13, the MTL1α sequence was always found with the variant CGCAGC Ho site sequence, and MTL1a co-occurred with the canonical site sequence, which indicates that the Ho site was cleaved and repaired by using information from MTL2a (in the MTL1α → MTL1a switch in CBS 138) or MTL3α (in the MTL1a → MTL1α switch in RND13). We interpret these results to indicate that a small number of RND13 cells are switching genotypes from haploid MTL1a to haploid MTL1α, and a small number of CBS 138 cells are switching from MTL1α to MTL1a. However, we did not find any evidence of diploid C. glabrata by a PCR amplification across the whole MTL1 locus from BUD5 to EMG1 to look for colonies yielding equal quantities of the MTL1α and MTL1a products, which differ slightly in size. Mating-type switching in a clinical isolate of C. glabrata also was reported recently (17).

Acquisition of the HO Endonuclease Gene in Species Close to S. cerevisiae. To investigate the organization and evolution of MAT (or MTL) and HO loci in yeasts, we combined sequences available from genome projects (10, 18) with our sequence data from several species, determined primarily from genomic clones made by the Génolevures project (14). The organization of HO and MAT loci is summarized in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

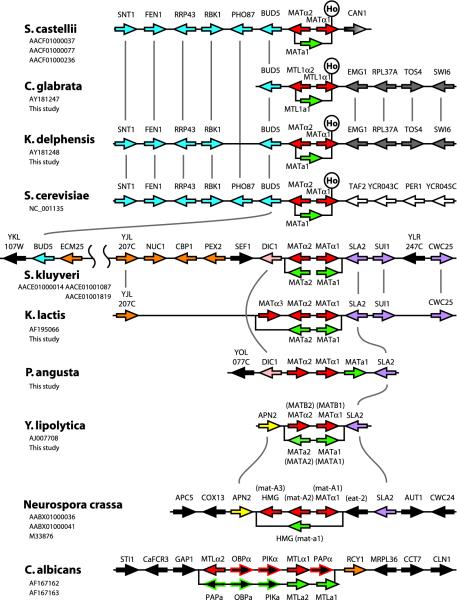

Fig. 3.

Comparative organization of the MAT locus in nine yeast species and Neurospora. For each species, the main horizontal line shows the organization of the α idiomorph, and the a idiomorph is represented by the offset box below it. Vertical lines connect orthologous genes. The position of a Ho endonuclease site in MATα1 is marked when present. Coloring indicates conserved groups of genes: red, α idiomorph; green, a idiomorph; blue, homologs of S. cerevisiae chromosome III (YCR033W-YCR038W); orange, homologs of chromosome X (YJL201W-YJL210W); purple, homologs of chromosome XIV (YNL243W-YNL245C), pink, DIC1 (YLR348C); yellow, APN2 (YBL019W); white, homologs of chromosome III (YCR042C-YCR045C); gray, homologs of chromosome XII (YLR186W-YLR182W); and gray gradient, CAN1 (YEL063C). Gene names in parentheses are species-specific. Previously published data are from refs. 6, 8, 10, 18, 33, 39, 48, and 49. GenBank accession numbers are listed under species names.

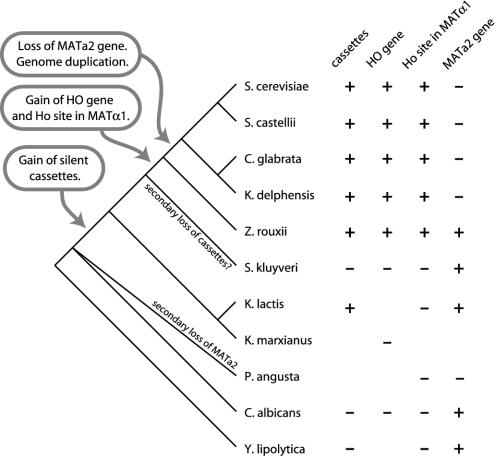

In S. cerevisiae, C. glabrata, and K. delphensis, the cleavage site for the Ho endonuclease is located within the MATα1 gene, because the 3′ end of this gene is located in the Z1 region (Figs. 1a and 3). Similarly, in S. castellii the Y/Z junction occurs within MATα1 and resembles a Ho cleavage site, and the genome sequence includes a HO gene (18). Heterothallic ho mutants of S. castellii have been obtained by ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis (19). In S. kluyveri, Kluyveromyces lactis, Y. lipolytica, and C. albicans, MATα1 is located completely within the unique Yα region of MATα, and the sequences at the Y/Z junctions in these species are heterogeneous and do not resemble the Ho site (Fig. 3). Considering the phylogenetic relationships among the species, it seems that the Y/Z boundary became situated inside MATα1 relatively recently, because of the gain of the Ho site (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Summary of events in MAT and HO locus evolution. The phylogenetic tree on the left (based on refs. 8, 50, and 51) is schematic and not drawn to scale. In the table on the right, blanks indicate missing data. Z. rouxii information is from Fig. 2 and low-coverage shotgun sequencing.

There is no evidence that any of the yeast species that lack a Ho site in MATα1 (Fig. 3) have a HO gene either. This observation is based on nearly complete genome sequencing of C. albicans and S. kluyveri (10, 18) and significant sequence surveying of K. lactis, Pichia angusta, and Y. lipolytica (14). We sequenced Génolevures plasmids containing part of a HO gene from Z. rouxii and an equivalent genomic region in K. marxianus from which the HO gene is missing (Fig. 2). From interspecies comparisons of local gene order, it seems that the HO gene materialized between the genes RIO2 and SSB in the immediate common ancestor of Z. rouxii, S. cerevisiae, S. castellii, C. glabrata, and K. delphensis. Gene order around the HO locus is well conserved across species, but the comparisons (Fig. 2) are complicated by the occurrence of a genome duplication in the ancestor of four species after it had split off from Z. rouxii (20) (see Fig. 4). The gene YNL208W is also absent from the K. marxianus site but is present on a small S. kluyveri contig not shown in Fig. 2.

The Ho endonuclease protein is related in sequence to inteins, selfish mobile genetic elements that can insert in-frame into host genes (21-25). Their translation products contain a protein-splicing domain to autoexcise the intein from the host protein and an endonuclease domain to propagate the element into intein-lacking alleles of the host gene. The Ho protein has the same two domains but lacks a host gene and has an additional zinc finger domain at its C terminus (23). Within the phylogenetic tree of all LAGLIDADG endonucleases (26), Ho clusters with the VMA1 intein (called VDE or PI-SceI), which is the only true intein in the S. cerevisiae genome. The VMA1 intein, like HO, is found only in hemiascomycetes, although its taxonomic distribution has been affected by horizontal transmission between species (27, 28). A hypothesis for the origin of HO is that an intein invaded the VMA1 gene of a hemiascomycete ancestor from an unknown source and subsequently duplicated to give rise to HO. Intein endonucleases normally cut an inteinless allele of their host gene, which is then repaired by using the intein-containing allele as a template. Ho has managed to switch this specificity so that it cuts in MATα1 (instead of a host gene), which is then repaired by using HML or HMR as a template (25). Because only haploid cells switch mating type, there is no second allele at MAT that can be used to direct repair. The switch in specificity is probably due to the extra zinc finger domain in Ho, because Ho uses this to bind its recognition site in MATα1 (29), whereas the VMA1 intein binds to its homing site in the VMA1 gene primarily using DNA contacts in the protein splicing domain (30, 31). Many aspects of HO evolution, such as how it came to be asymmetrically regulated in mother and daughter cells by Ash1 or why Ho retains a protein-splicing domain, still are not understood.

Silent Cassettes. Silent cassettes of mating-type information are an essential part of the switching system. All species that have HO genes also have silent cassettes (Fig. 4). Cassettes often can be readily distinguished from functional MAT loci because they may contain truncated duplicates of the genes that flank MAT. In S. cerevisiae, part of BUD5 is duplicated at HML. In the S. castellii genome sequence, the 5′ end of CAN1 is found beside α1 and a1 genes in short contigs that probably represent silent cassettes. The C. glabrata MTL2 and MTL3 loci contain truncated copies of the 3′ end of EMG1 (8, 9). In K. delphensis we identified a genomic clone containing a probable HMRa-like cassette with a 3′ fragment of EMG1 adjacent to homologs of the genes YMR315W-YMR310C, which in S. cerevisiae are in a subtelomeric region.

Although it apparently has no HO gene, K. lactis has a MAT locus and two cassettes (HMLα and HMRa) whose transcriptional silencing has been studied (32-34). Almost 40 years ago Herman and Roman (35) carried out a detailed genetic analysis of mating-type switching in K. lactis and identified mutants in two genes (Hα and Ha) that clearly correspond to the two cassettes. They commented that they did not identify any mutants with phenotypes equivalent to mutations in the HO gene of S. cerevisiae, which is consistent with the genomic evidence. The two strains of K. lactis used by Herman and Roman were natural heterothallic isolates, and mating-type switching was observed only in spores made by crossing the two strains. The frequency of mating-type switching they observed was much lower than in homothallic S. cerevisiae, and, moreover, the ability to switch declined after a few meiotic generations. To complete the picture for K. lactis, we sequenced the MAT locus from strain CBS 2359 [Northern Regional Research Laboratory (NRRL) no. Y-1140], which was arbitrarily designated as mating type a by Herman and Roman (35). It contains MATa1 and HMG domain (MATa2) genes identical to those reported in the HMRa cassette by Astrom et al. (33) (Fig. 3).

The genome sequence of S. kluyveri (18) does not show any silent cassettes, which is surprising given its phylogenetic position (Fig. 4). Also, there are no published reports of mating-type switching in S. kluyveri. This species is unusual in that it readily forms sexual aggregates and frequent polyploids (36-38). It is possible that it has secondarily lost cassettes and become an obligate heterothallic species (Fig. 4). The more distantly related hemiascomycetes Y. lipolytica and C. albicans also do not have silent cassettes (6, 39). These observations suggest a two-step model for the evolution of mating-type loci, with the first step being the invention of cassettes and the recruitment of silencing apparatus and the second step being the acquisition of the Ho endonuclease, which may have increased the frequency and/or precision of genotype switching. In S. cerevisiae, the frequency of switching is ≈106 times higher in HO than in ho cells (3). Our results support the suggestion of Keeling and Roger (24) that when Ho arose it became integrated into a preexisting passive switching system that relied on gene conversion.

Loss of an HMG Domain Gene. The S. cerevisiae MAT locus idiomorphs code for only three proteins: the homeodomain proteins a1 and α2 and the “α-domain” protein α1 (40). Homologs of these three genes are found in all nine hemiascomycete species we examined (Fig. 3). It was reported previously that Y. lipolytica MATA1 has no similarity to MATa1 in other species (39), but this report resulted from overlooking a probable second exon of this gene.

An additional gene (MATa2) coding for an HMG domain DNA-binding protein is present in the MATa idiomorphs of several species (Fig. 3). This gene is called MATA2 in Y. lipolytica (39) and MATa2 in K. lactis (33), but it should not be confused with the unrelated ORF called MATa2 in S. cerevisiae, which is unlikely to be a functional gene (40). The HMG gene is present in the MTLa idiomorph of C. albicans but was not previously recognized (6) because it is divergent in sequence and contains an intron (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). It is also present in S. kluyveri and Z. rouxii (Fig. 4). In Y. lipolytica, the function of the MATA2 HMG domain gene is to repress conjugation in diploids (39). Very recently, Tsong et al. (41) identified C. albicans MTLa2 as a positive regulator of a-specific genes.

We sequenced a genomic clone from P. angusta (also called Hansenula polymorpha; strain CBS 4732) that contains the genes MATα2, MATα1, and MATa1, in that order and all in the same orientation. The presence of MATα and MATa information on the same idiomorph is surprising but consistent with genetic evidence that P. angusta is a homothallic haploid in which any strain can mate with any other strain (42). P. angusta's MAT locus organization is similar to that seen in homothallic species of Cochliobolus (a distantly related ascomycete classified in the Pezizomycotina), which arose from heterothallic ancestors by DNA rearrangement at the MAT locus (43), and in a homothallic Gibberella species (44). It is also surprising that the P. angusta MAT locus does not have a MATa2 gene, although it has been suggested that P. angusta has a tetrapolar mating system that would necessitate a second unlinked mating-type locus (45).

Partial Conservation of the MAT Locus Position Among Ascomycetes. The location of the MAT genes can be traced through hemiascomycete evolution and reveals a surprising degree of positional continuity despite numerous gene order changes (Fig. 3). The one exceptional species is C. albicans, whose gene order around MTL is unrelated to that in other species except for the presence of RCY1 (YJL204C).

In Y. lipolytica the MAT locus lies between homologs of S. cerevisiae APN2 and SLA2 (39). Remarkably, the same two genes are beside the MAT loci of the filamentous ascomycetes N. crassa (Fig. 3) and Gibberella zeae (GenBank accession no. AACM01000358), so this configuration may be the ancestral one for all ascomycetes. The arrangement of SLA2 on the right side of MAT (as shown in Fig. 3) is conserved in P. angusta, K. lactis, and S. kluyveri. In contrast, three different genes are found to the right of MAT in S. cerevisiae, S. castellii, and the C. glabrata/K. delphensis pair. We hypothesize that in these species the activity of Ho may have elevated the rate of evolutionary chromosome rearrangement.

On the left side, BUD5 is immediately beside MAT in S. cerevisiae, S. castellii, C. glabrata, and K. delphensis. This section of S. cerevisiae chromosome III has a sister relationship through genome duplication with part of S. cerevisiae chromosome X, including the duplicated gene pair YCR037C (PHO87) and YJL198W (PHO90) (46). In S. kluyveri, which separated from the S. cerevisiae lineage before genome duplication occurred (20) (Fig. 4), the region to the left of MAT includes a series of genes from the same area of chromosome X, between YJL207C and YJL210W (PEX2). After genome duplication, a contiguous group of ≈10 genes must have been deleted from the left side of MAT in the progenitor of S. cerevisiae chromosome III, because in S. kluyveri BUD5 is adjacent to YJL201W (ECM25). In K. lactis, YJL207C is immediately adjacent to the left side of the MAT locus and is truncated by ≈1.2 kb at its 3′ end relative to other species. This suggests that a single large deletion may have removed everything between the 3′ end of YJL207C and MATα3 in K. lactis. The 3′ end of the shortened gene is duplicated in the K. lactis HML and HMR loci.

Between PEX2 and MAT in S. kluyveri are two genes, including one orthologous to the chromosome XII gene DIC1, which also appears to the left of MAT in P. angusta (Fig. 3). In summary, the chromosomal location of the MAT locus has been conserved throughout much of hemiascomycete evolution but has been disturbed by the effects of genome duplication and the gain of the Ho endonuclease.

Conclusion

The mating system of hemiascomycetes has evolved from an obligate heterothallic system, as seen in Y. lipolytica, to heterothallism with low-level switching, as seen in K. lactis, to Ho-catalyzed homothallic switching, as seen in S. cerevisiae,via a series of steps (summarized in Fig. 4). The partial conservation of gene order flanking the MAT loci is sufficient to indicate that the mating-type loci of hemiascomycetes and filamentous ascomycetes are orthologous despite their gene content differences and their very different pathways of sexual development. Homeodomain and HMG domain DNA-binding proteins seem to have been interchangeable during fungal evolution, with the MAT loci of modern species having only homeodomains [S. cerevisiae and Cryptococcus neoformans (47)], only HMG domains (N. crassa), or a mixture of the two (K. lactis, C. albicans, Y. lipolytica, and Schizosaccharomyces pombe).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. R. Ueno and N. Urano for the RND13 strain, S. Casaregola for Génolevures plasmids, and S. Krueger and W. Zimmermann at Agowa (Berlin) for sequencing. This work was supported by Science Foundation Ireland.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: MAT, mating-type; MTL, MAT-like.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession numbers AJ617300-AJ617311).

References

- 1.Metzenberg, R. L. & Glass, N. L. (1990) BioEssays 12, 53-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oshima, Y. (1993) in The Early Days of Yeast Genetics, eds. Hall, M. N. & Linder, P. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), pp. 291-304.

- 3.Hicks, J. B., Strathern, J. N. & Herskowitz, I. (1977) in DNA Insertion Elements, Plasmids and Episomes, eds. Bukhari, A., Shapiro, J. & Adhya, S. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), pp. 457-462.

- 4.Herskowitz, I., Rine, J. & Strathern, J. N. (1992) in The Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces, eds. Jones, E. W., Pringle, J. R. & Broach, J. R. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), pp. 583-656.

- 5.Haber, J. E. (1998) Annu. Rev. Genet. 32, 561-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hull, C. M. & Johnson, A. D. (1999) Science 285, 1271-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller, M. G. & Johnson, A. D. (2002) Cell 110, 293-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong, S., Fares, M. A., Zimmermann, W., Butler, G. & Wolfe, K. H. (2003) Genome Biol. 4, R10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srikantha, T., Lachke, S. A. & Soll, D. R. (2003) Eukaryot. Cell 2, 328-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tzung, K. W., Williams, R. M., Scherer, S., Federspiel, N., Jones, T., Hansen, N., Bivolarevic, V., Huizar, L., Komp, C., Surzycki, R., et al. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3249-3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueno, R., Urano, N. & Kimura, S. (2001) Fish. Sci. 67, 138-145. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueno, R., Urano, N. & Kimura, S. (2002) Fish. Sci. 68, 571-578. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurtzman, C. P. & Robnett, C. J. (1998) Antonie Leeuwenhoek 73, 331-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Souciet, J., Aigle, M., Artiguenave, F., Blandin, G., Bolotin-Fukuhara, M., Bon, E., Brottier, P., Casaregola, S., de Montigny, J., Dujon, B., et al. (2000) FEBS Lett. 487, 3-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nickoloff, J. A., Singer, J. D. & Heffron, F. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 1174-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekino, K., Kwon, I., Goto, M., Yoshino, S. & Furukawa, K. (1999) Yeast 15, 451-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brockert, P. J., Lachke, S. A., Srikantha, T., Pujol, C., Galask, R. & Soll, D. R. (2003) Infect. Immun. 71, 7109-7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cliften, P., Sudarsanam, P., Desikan, A., Fulton, L., Fulton, B., Majors, J., Waterston, R., Cohen, B. A. & Johnston, M. (2003) Science 301, 71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marinoni, G., Manuel, M., Petersen, R. F., Hvidtfeldt, J., Sulo, P. & Piskur, J. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181, 6488-6496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong, S., Butler, G. & Wolfe, K. H. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 9272-9277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirata, R., Ohsumi, Y., Nakano, A., Kawasaki, H., Suzuki, K. & Anraku, Y. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 6726-6733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gimble, F. S. & Thorner, J. (1992) Nature 357, 301-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pietrokovski, S. (1994) Protein Sci. 3, 2340-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keeling, P. J. & Roger, A. J. (1995) Nature 375, 283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gimble, F. S. (2000) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185, 99-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dalgaard, J. Z., Klar, A. J., Moser, M. J., Holley, W. R., Chatterjee, A. & Mian, I. S. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4626-4638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koufopanou, V., Goddard, M. R. & Burt, A. (2002) Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okuda, Y., Sasaki, D., Nogami, S., Kaneko, Y., Ohya, Y. & Anraku, Y. (2003) Yeast 20, 563-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nahon, E. & Raveh, D. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 1233-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moure, C. M., Gimble, F. S. & Quiocho, F. A. (2002) Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 764-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werner, E., Wende, W., Pingoud, A. & Heinemann, U. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3962-3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Astrom, S. U. & Rine, J. (1998) Genetics 148, 1021-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Astrom, S. U., Kegel, A., Sjostrand, J. O. & Rine, J. (2000) Genetics 156, 81-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sjostrand, J. O., Kegel, A. & Astrom, S. U. (2002) Eukaryot. Cell 1, 548-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herman, A. & Roman, H. (1966) Genetics 53, 727-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wickerham, L. J. (1958) Science 128, 1504-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wickerham, L. J. & Dworschack, R. G. (1960) Science 131, 985-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCullough, J. & Herskowitz, I. (1979) J. Bacteriol. 138, 146-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurischko, C., Schilhabel, M. B., Kunze, I. & Franzl, E. (1999) Mol. Gen. Genet. 262, 180-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson, A. D. (1995) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 5, 552-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsong, A. E., Miller, M. G., Raisner, R. M. & Johnson, A. D. (2003) Cell 115, 389-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lahtchev, K. L., Semenova, V. D., Tolstorukov, I. I., van der Klei, I. & Veenhuis, M. (2002) Arch. Microbiol. 177, 150-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yun, S. H., Berbee, M. L., Yoder, O. C. & Turgeon, B. G. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5592-5597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yun, S. H., Arie, T., Kaneko, I., Yoder, O. C. & Turgeon, B. G. (2000) Fungal Genet. Biol. 31, 7-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lahtchev, K. (2002) in Hansenula polymorpha: Biology and Applications, ed. Gellissen, G. (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany), pp. 8-20.

- 46.Wolfe, K. H. & Shields, D. C. (1997) Nature 387, 708-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hull, C. M., Davidson, R. C. & Heitman, J. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 3046-3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goffeau, A., Aert, R., Agostini-Carbone, M. L., Ahmed, A., Aigle, M., Alberghina, L., Allen, E., Alt-Mörbe, J., André, B., Andrews, S., et al. (1997) Nature 387, Suppl., 5-105. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galagan, J. E., Calvo, S. E., Borkovich, K. A., Selker, E. U., Read, N. D., Jaffe, D., FitzHugh, W., Ma, L. J., Smirnov, S., Purcell, S., et al. (2003) Nature 422, 859-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurtzman, C. P. & Robnett, C. J. (2003) FEMS Yeast Res. 3, 417-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cai, J., Roberts, I. N. & Collins, M. D. (1996) Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46, 542-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.