Abstract

The reaction of oxidized bovine cytochrome c oxidase (bCcO) with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was studied by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) to determine the properties of radical intermediates. Two distinct radicals with widths of 12 and 46 G are directly observed by X-band EPR in the reaction of bCcO with H2O2 at pH 6 and pH 8. High-frequency EPR (D-band) provides assignments to tyrosine for both radicals based on well-resolved g-tensors. The wide radical (46 G) exhibits g-values similar to a radical generated on L-Tyr by UV-irradiation and to tyrosyl radicals identified in many other enzyme systems. In contrast, the g-values of the narrow radical (12 G) deviate from L-Tyr in a trend akin to the radicals on tyrosines with substitutions at the ortho position. X-band EPR demonstrates that the two tyrosyl radicals differ in the orientation of their β-methylene protons. The 12 G wide radical has minimal hyperfine structure and can be fit using parameters unique to the post-translationally modified Y244 in bCcO. The 46 G wide radical has extensive hyperfine structure and can be fit with parameters consistent with Y129. The results are supported by mixed quantum mechanics and molecular mechanics calculations. In addition to providing spectroscopic evidence of a radical formed on the post-translationally modified tyrosine in CcO, this study resolves the much debated controversy of whether the wide radical seen at low pH in the bovine enzyme is a tyrosine or tryptophan. The possible role of radical formation and migration in proton translocation is discussed.

1. INTRODUCTION

Cytochrome c Oxidase (CcO) is the membrane-bound terminal enzyme in the electron transfer chain of eukaryotes. In CcO, a two-atom copper center (CuA) accepts electrons from cytochrome c and transfers them via a low-spin heme group (heme a) to a heme a3–CuB binuclear center at which the four-electron reduction of oxygen to water takes place. Associated with the oxygen chemistry, four protons are translocated by the enzyme, creating a proton gradient across the membrane that is utilized for the generation of ATP by ATP synthase.1

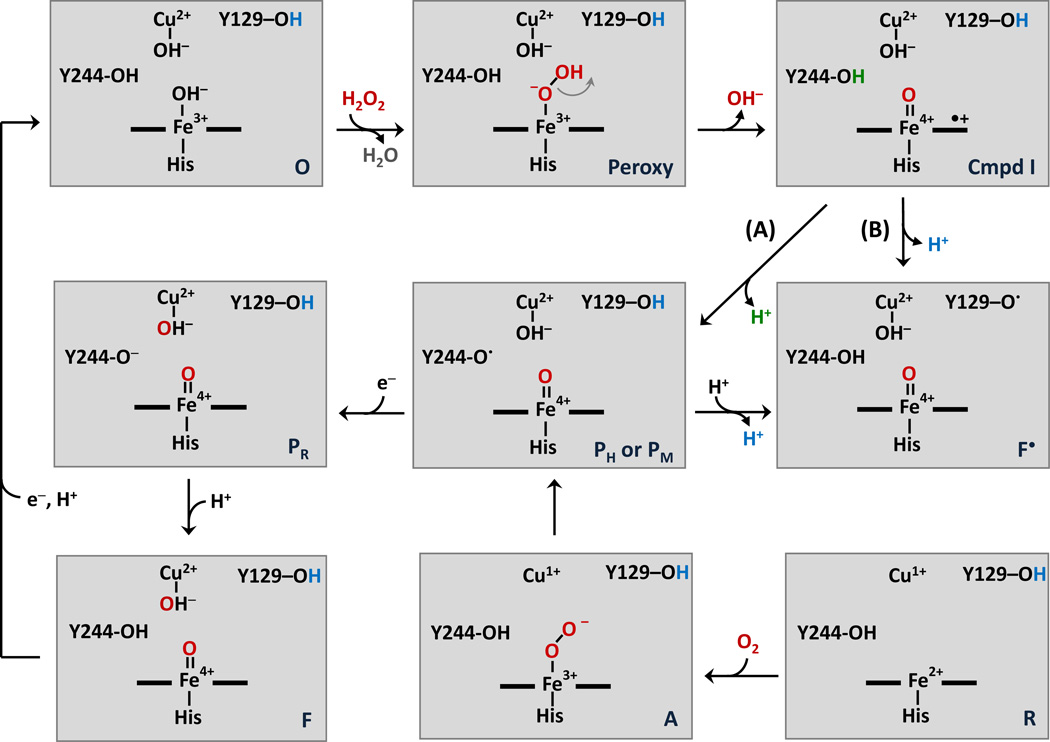

Although the mechanism of the oxygen reduction reaction has been proposed (Fig. 1), the properties of some key intermediates and the role of amino acid radical(s) during the oxygen reaction are not known.2 Of particular importance is the need to clarify the properties of the “P” intermediates, in which it has been shown that the O-O bond has been cleaved resulting in a ferryl structure on the heme a3 iron atom.3 Two P intermediates have been reported during turnover. The PR intermediate is formed under conditions in which all of the metal redox centers are initially in their reduced states. The PM intermediate is formed when only heme a3 and CuB are reduced, while heme a and CuA remain oxidized (the so-called “mixed-valence” (MV) form of the enzyme). Under physiological conditions it is thought that PM precedes PR in the reaction cycle (Fig. 1) and subsequently is converted to another ferryl species (F). Upon formation of PM, the free energy released by the reduction of O2 is trapped by the high oxidation state of the binuclear site and the nearby protein moiety.

Figure 1. Postulated mechanisms for the reaction of oxygen with the reduced CuB-heme a3 binuclear center in CcO and for the reaction of H2O2 with the oxidized enzyme.

In this scheme the reaction with O2 with the reduced binuclear center starts from the lower left corner and progresses to the PM intermediate shown in the center. PM is associated with a radical on Y244, which donates an electron to the binuclear center following the O-O bond cleavage reaction. The reaction sequence progresses to the PR and F intermediates and ultimately to the oxidized state on the top left. The reaction with H2O2 is initiated by its binding to the heme a3 of the oxidized enzyme. The oxidized bCcO preparation used for the present work contains a peroxide bridged between Cu and Fe.25, 56 Thus, the O species in the scheme are likely to be formed by the H2O2 reduction of the bridged peroxide. The O-O bond cleavage of the resulting hydroperoxy intermediate leads to a Compound I species with a porphyrin π-cation, which can accept an electron from Y244 to form PH, leaving a radical on Y244 (Pathway A). The Y244 radical can be re-reduced by Y129 to form F•. Alternatively, the porphyrin π-cation can accept an electron directly from Y129 to form F• without passing through Y244 (Pathway B). The PH intermediate formed via Pathway A is the same as that (PM) generated in the O2 reaction and depending on the pH can progress to form PR and F.

In the formation of the PM state, an insufficient number of electrons are available from the metal redox centers to cleave the O-O bond, and thus an additional electron is needed; it has been postulated to be donated from an amino acid residue resulting in a radical species. The most likely candidate to supply the additional electron is Y244 (bovine numbering), which contains a covalent bond to H240, one of the CuB ligands. However, a radical on Y244 has not been observed in spectroscopic studies of intermediates generated in the reaction of the reduced enzyme with oxygen,4, 5 although it was indicated indirectly during the reaction of the MV form of the enzyme with oxygen by an iodine trapping experiment, in which an iodine adduct of Y244 was identified in a small fraction of the enzyme.6 Attempts to react the MV enzyme with oxygen and freeze-trap the intermediates for EPR or other spectroscopic studies are challenging experiments and have not been reported to our knowledge.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) treatment of CcO is a well-established method for preparing the P and F ferryl intermediates in CcO, which have been postulated to have the same structures as those generated during turnover conditions.3, 7–10 (For a recent review of the H2O2 reaction see the article by Wikstrom.11) Specifically, an analogue of PM, sometimes referred to as PH, is formed by the reaction of the oxidized enzyme with H2O2 at alkaline pH. The optical absorption difference spectrum (with respect to the fully oxidized enzyme) of PH has a band at 607 nm, just as in PM 3, 12, 13 and amino acid-based radicals are associated with its formation although the radical populations are typically in the range of a few percent of the enzyme.14 Another ferryl species, F•, forms by reacting CcO with H2O2 at weakly acidic pH. It is assigned as an intermediate with an amino acid based radical and an optical transition at ~575 nm 14, 15 similar to that of the catalytic intermediate, F (580 nm), which, however, is not associated with a radical. Importantly, the lifetimes of these intermediates are much longer than those in the reaction of the enzyme with O2, so they can be more readily trapped and studied by spectroscopic methods. The H2O2 reaction is postulated to follow a mechanism in Eq. 1 in which the reaction product is a Compound I type species with a π-cation radical on the porphyrin ring (Por•+) of heme a3, 4, 16 which is then reduced by an amino acid (AA) in its vicinity leading to the formation of a radical (AA•) on the amino acid.

| Eq. 1 |

Although it is well-accepted that the P and F states have the same Fe4+=O electronic structure, it remains unclear as to why they exhibit distinct optical transition bands. Recently it was shown that the addition of ammonia to the F state in CcO from Paracoccus denitrificans (PdCcO) could convert it to a P state, in contrast to the order of intermediate formation in the catalytic cycle.16 These new results suggest that the difference in the CuB ligands between the P and F states may account for their optical differences.16

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) is very useful for the identification of the radicals formed by the H2O2 treatment of CcO. However, the correlation of radical species with specific intermediates formed in the H2O2 reaction has been controversial. In PdCcO, a radical was reported to form on Y167 (equivalent to Y129 in bCcO).15, 17 In contrast, in bCcO, a wide and a narrow radical were detected in the reaction with H2O2 18 and were attributed to a tryptophan cation radical (either W126 or W236) and an unidentified radical resulting from a side reaction, respectively. 14, 19 Based on a later comparative study of the data, Svistunenko et al. suggested that local interactions could modulate the lineshapes and in bCcO the wide radical was on Y129 rather than on a tryptophan residue.20

In summary, although amino acid based radicals have been detected by several investigators, there is no consensus as to their assignment. In addition, so far, there is no spectroscopic evidence for radical formation on Y244 in bCcO or its equivalent in PdCcO. In this study, we have generated the PH and F• intermediates by the addition of H2O2 to bCcO and used X-band (9 GHz) and D-band (130 GHz) EPR spectroscopy to characterize the amino acid-based radicals. To obtain an atomic detailed description of the spin density, we also performed mixed quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM)21 simulations of the radical formation.22, 23 Our results provide firm assignments for the identity of the radical species including the first spectroscopic identification of a radical on Y244.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The bovine Cytochrome c Oxidase (bCcO) samples used in these measurements were prepared from bovine heart tissue by two different methods. Some were prepared according to the protocol developed by Yoshikawa and coworkers.24 Others were prepared from crystallization quality enzyme, by crystallizing the enzyme into microcrystals, collecting them and then redissolving them for the experiments. No qualitative differences between the two types of enzyme were observed. Enzyme concentration was calculated using an extinction coefficient of 33.6 mM−1 cm−1 for the fully-reduced bCcO at 604 nm minus oxidized enzyme at 630 nm.25 30% w/v hydrogen peroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was diluted in buffer, purged on ice for the anaerobic samples, and used within four hours. Enzyme and hydrogen peroxide solutions were diluted in the following buffers: 200 mM BIS-TRIS with 0.2% w/v n-decyl-β-maltoside at pH 6 and 200 mM HEPES with 0.2% w/v n-decyl-β-maltoside, at pH 8.

Optical spectra

Optical absorption measurements were made on identical samples at room temperature. The acquisition was started after an incubation period of 60 seconds. Optical absorption measurements were taken on a UV2100 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Inc., Columbia, MD) with a spectral slit width of 1 nm. The concentration of P was determined by using the difference spectrum between the intermediate and the oxidized spectrum with extinction coefficients of 14 and 2.9 mM−1 cm−1 for the 607 nm minus 630 nm and 575/580 minus 630 nm absorbance, respectively; and the concentration of F• was determined by using the difference spectrum between the intermediate and the oxidized spectrum with extinction coefficients of 0.6 and 6.2 mM−1 cm−1 for the 607 nm minus 630 nm and 575/580 minus 630 nm absorbance, respectively. These values were determined from those reported by Wikstrom and Morgan26 and corrected for the high purity of the samples used in this study.

EPR spectra

X-band (9 GHz) measurements were made on a Varian E-line spectrometer at 77K using a liquid nitrogen finger dewar inserted into a TE102 resonator. Typical instrumental parameters were as follows: frequency, 9.1 GHz; power, 0.2 mW; modulation amplitude, 3.2 G; scan time 2 minutes; time constant, 0.5 s; number of scans averaged, 8 to 16. D-band (130 GHz) EPR spectra were performed on a spectrometer assembled at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, as previously described.27 The magnetic field is generated using a 7 T Magnex superconducting magnet equipped with a 0.5 T sweep/active shielding coil. Field swept spectra were obtained in the two pulse echo-detected mode with the following parameters: frequency, 130.001 GHz; temperature, 7 K; repetition rate, 15 Hz; 90 degree pulse, 40 ns; time τ between pulses, 150 ns. The spectra displayed in Figs. 3b, 3c, 5c, and 5d are derivatives of the echo-detected spectra in order to approximate the effects of field modulation. The temperature of the sample was maintained to an accuracy of approximately ±0.3 K using an Oxford Spectrostat continuous flow cryostat and ITC503 temperature controller. The magnetic field at both X-band and D-band was calibrated to an accuracy of ~3 gauss using a sample of manganese doped into MgO.28

Spectral simulations

The isotropic hyperfine coupling of the β-methylene protons is directly proportional to the spin density in the pz orbital of the adjacent carbon, ρπ(C4). The McConnell equation29 describes this relationship:

| Eq. 2 |

We can assume that B0 << B2, simplifying the equation:

| Eq. 3 |

For tyrosine radicals, a value of 58 G can be assumed for B2.30 If we let ρπ(C4) = 0.30, then the Aiso value listed in Table 2 for the pH 8 radical yields a θ value of 60° for both beta protons. In unmodified tyrosyl radicals, the value of ρπ(C4) is variable and dependent on the environment, but a value in the range of 0.36 to 0.41 is typically assumed.20, 31 However for the His-Tyr moiety studied here, we anticipate that some spin density may be shared on the covalently linked imidazole. In our simulations, we started at ρπ(C4) = 0.38 and varied θ through space. The simulations were slightly broad, so we decreased ρπ(C4) to 0.30 and varied θ through space again, finding a good fit at θ = 60°. The slight reduction in spin density on the phenol ring is consistent with a modified tyrosine, which can share spin onto the imidazole of H240. Kim et al. report experimental results and DFT calculations of a model compound in which 0.09 spin is shared onto the imidazole.32 FT-IR data of another Tyr-His model compound also supports that spin density is withdrawn by the imidazole.33

Table 2.

Parameters used to simulate X-band and D-band spectra of CcO tyrosyl radicals formed at pH 8 and pH 6.a

| pH 8 radical | pH 6 radical | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Hβ1,2 | Hortho 1 | Hβ1 | Hβ2 | Hortho 1,2 |

| Ax | 4.5 | 7.2 | 16.5 | 14.9 | 9.1 |

| Ay | 4.2 | 2.2 | 17.9 | 14.0 | 2.9 |

| Az | 4.2 | 5.5 | 13.8 | 12.4 | 6.8 |

| Aiso | 4.3 | 5.0 | 16.1 | 13.4 | 6.3 |

| θb | ±60 | - | −26 | +34 | - |

| αc | - | +33 | - | - | ±33 |

The absolute values of hyperfine coupling constants are given in Gauss.

The dihedral angle (degrees) between the C–H bond of the beta carbon and the normal to the phenol ring plane.

The angle (degrees) between Ax and gx.

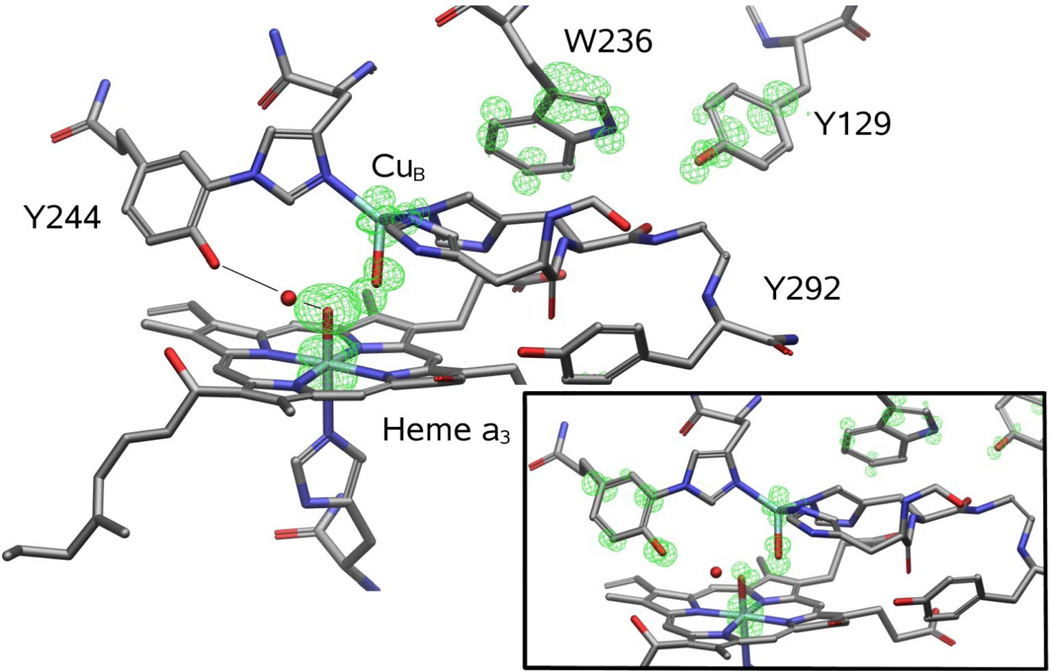

QM/MM calculations

QM/MM methods can join together QM and MM representations of different sectors of a complex system.21 The conjunction of these technologies contains the elements necessary to properly describe the potential energy surfaces relevant to enzymatic chemistry. The model for CcO compound I has been extracted from our recent study.34 For the MM part we have used the OPLS-AA force field35 while the QM part used unrestricted DFT with the B3LYP functional in combination with the 6-31G* and LACVP* effective core potential basis sets; all calculations were done with Qsite.36 By using QM/MM techniques, we can model the entire enzyme (plus a 10 Ǻ solvent layer) and treat a large enough quantum mechanical region to describe the electronic wave function. The results presented are based on spin density plots describing the radical content of the different intermediates. The spin plots are obtained from a grid projection of the difference in the alpha and beta spin-orbitals from an unrestricted wave function. They represent the total amount (and localization) of spin density. Both quartet and doublet spin states gave almost identical energies and spin density. The quantum mechanical region, shown in Figure 6, includes heme a3 with its oxo and histidine axial ligands, the metal center CuB with its three coordinated histidines and OH group, Y129, Y244, Y292 and W236.

Figure 6.

Spin density for the optimized ferryl species without deprotonation of Y244 (main panel) and after a proton transfer from Tyr244 (lower right inset). The total unpaired spin density is shown with a green mesh.

3. RESULTS

The reaction of bCcO with H2O2 was carried out by hand mixing the enzyme with H2O2 at pH 6 and 8. For the EPR measurements the samples were freeze quenched within 1 minute and for the optical absorption measurements the spectra were obtained at 1 minute after mixing as well, but under our conditions the samples were stable for much longer periods. To confirm that the data were not sample preparation dependent all of the measurements were duplicated with enzyme samples prepared by the protocol developed by Yoshikawa and coworkers24 and those prepared from solubilized microcrystals as described in the Materials and Methods section.

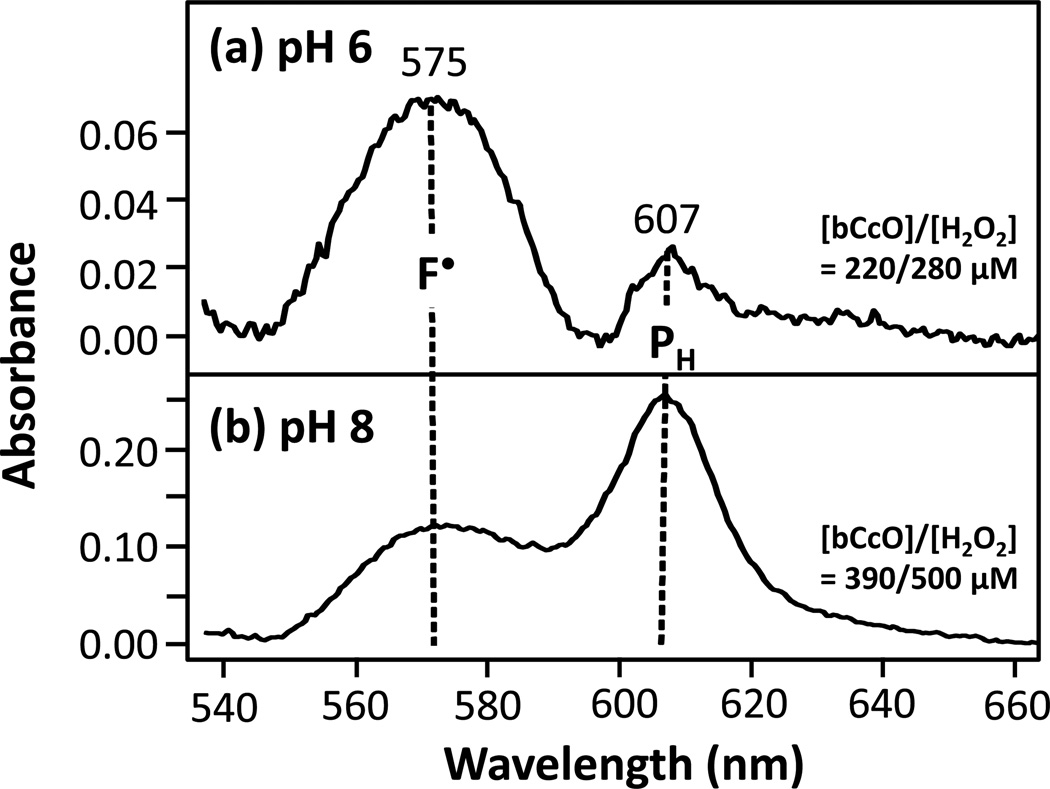

Optical characterization of the intermediates formed in the reaction of bCcO with H2O2

The optical difference spectra (versus the fully oxidized enzyme) of the intermediates derived from the reaction of bCcO with H2O2 at pH 6 and 8 are shown in Fig. 2. Two distinct intermediates were detected with optical transitions at 575 and 607 nm, which we assign as F• and PH, respectively, as reported previously.14 At pH 6, when the enzyme (220 µM) was reacted with 280 µM of H2O2the 575 nm species (F•) was the dominant product (100 µM) with a small amount (10 µM) of the 607 nm species (PH) also present (Fig. 2a). At pH 8, in which the enzyme (390 µM) was reacted with 500 µM of H2O2we observed contributions from the PH species (150 µM) at 607 nm and the F• species (110 µM) at 575 nm (Fig. 2b). These results are summarized in Table 1. In both of these cases we attribute the incomplete accounting of the total enzyme as an indication that some of it was in the fully oxidized state and therefore not visible in the difference spectra. It is also noteworthy that at both pH values both PH and F• were detected. As pointed out by Tuukkanen et al. this is likely a result of the broad pH dependence of the protonation of the lysine residue at the entrance of the K-pathway.37

Figure 2. Optical absorption difference spectra of the intermediates formed in the reaction bCcO with H2O2.

Difference spectra were taken relative to the oxidized resting bCcO at either pH 6 (a) or pH 8 (b). Optical spectra were recorded at ~1 min following mixing. The bCcO/H2O2 concentrations for (a) and (b) were 220/280 µM and 390/500 µM, respectively.

Table 1.

The concentrations of PM and F• determined from the optical absorption spectra of the reaction of H2O2 with bCcO.

| pH | [bCcO] | [H2O2] | [F•] | [PM] | [PM]/[F•] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 220 | 280 | 100 | 10 | 0.1 |

| 8 | 390 | 500 | 110 | 150 | 1.4 |

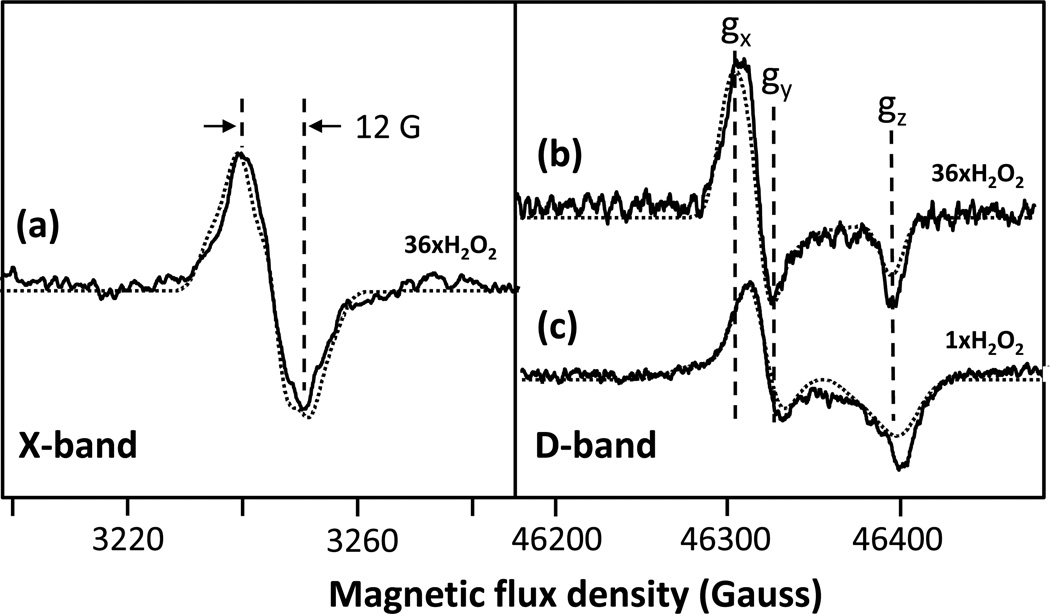

EPR characterization of the intermediates formed in the reaction of bCcO with H2O2 at pH 8

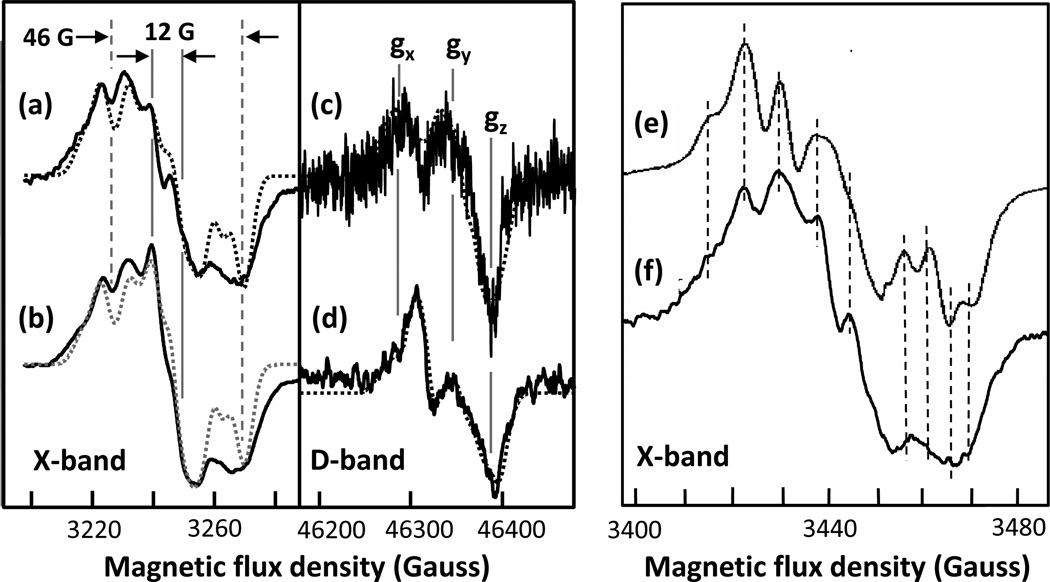

In the initial series of experiments at pH 8, the X-band and D-band EPR spectra were measured on samples prepared at equal concentrations of bCcO and H2O2 and at a 36-fold excess of H2O2. In the former case a mixture of radicals was obtained (Fig. 3c), whereas in the latter case, a single radical species was detected (Fig. 3a). It has been noted in the past that with a large excess of H2O2 (500-fold), only a narrow radical is present. 16 Although the origin of the effect of the H2O2 concentration has not been determined, it may be associated with the catalase activity of CcO, at high H2O2 concentrations. 16 In any case to simplify the analysis, we first focus on the pure narrow radical shown in Fig. 3a.

Figure 3. X-band and D-band EPR spectra of the intermediates formed in the reaction of bCcO with H2O2 at pH 8.

Panel (a) and (b) show the X-band and D-band spectra (solid lines), respectively, obtained following the reaction of bCcO with 36-fold excess of H2O2. Panel (c) shows the D-band spectrum (solid line) of bCcO obtained following its reaction with a stoichiometric amount of H2O2revealing contributions from both the 12 G and 46 G radicals. The experimental and simulation data are given by the solid and dotted lines, respectively. The parameters for the simulations are given in Table 1. In the X-band spectrum (a), the contribution from CuA has been removed by subtracting the spectrum of resting oxidized bCcO.

In the X-band EPR spectrum (Fig. 3a), the radical signal is very narrow (12 G wide) with a shape and linewidth that are consistent with the unassigned narrow radical observed by others at alkaline pH. 14–16, 18, 19 To resolve the origin of the 12 G radical species observed in the X-band spectra, the D-band (130 GHz) echo-detected EPR measurements at 7 K were carried out allowing precise determination of g-tensor values. Based on the D-band measurements, the gx, gy and gz values of the 12 G radical are 2.0059, 2.0051 and 2.0017, respectively (Fig. 3b). The gx value is in the range of a tyrosyl radical, 2.01 > gx > 2.006, 30, 38–40 and effectively rules out tryptophanyl, histidinyl and glycyl species, all which have a gx ≤ 2.0045. 41, 42 It also rules out cysteine thiyl radicals, which exhibit gx values in a range of 2.29 - 2.21. 43 Moreover, the gy and gz values are also consistent with tyrosyl species, as gy generally falls between 2.005 and 2.004 and gz is typically ~ 2.002. Interestingly, the gx and gy values have converged to a |gx – gy| separation of only 0.0008, indicating a near axial symmetry. We conclude, based on this analysis of the g-tensor, that the narrow (12 G) radical resides on a tyrosine residue, albeit modified, based on the small |gx – gy| separation (vide infra).

Narrow radical resonances in X-band EPR spectrum, such as that reported here, are relatively unusual for a tyrosine. However, they have been found in modified tyrosines in which the ring ortho protons are replaced with other atoms. Importantly, narrowed X-band spectra have been reported for several model complexes of CcO in which a His is linked to a Tyr at its ortho position replacing the proton.32, 33, 44 Narrowed X-band spectra have also been reported for proteins such as apogalactose oxidase (width ~25 G) 45 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis KatG (width ~17 G),46 both of which have a radical located on a tyrosine with modifications at the ortho position. A modification at the ortho position of the Tyr is also consistent with the small |gx – gy| separation of 0.0008 observed in the D-band spectra (Fig. 3b). It has been established that radicals generated on tyrosine adducts with a single covalent modification at the ortho position have a reduced value of |gx – gy| relative to unmodified tyrosyl radicals in which |gx – gy| ~ 0.0046 – 0.0015 as summarized in Supporting Information, Table S2. This trend was confirmed by the D-band EPR spectrum of 2-amino-p-cresol (Supporting Information, Fig. S2) with a |gx – gy| of 0.0012.

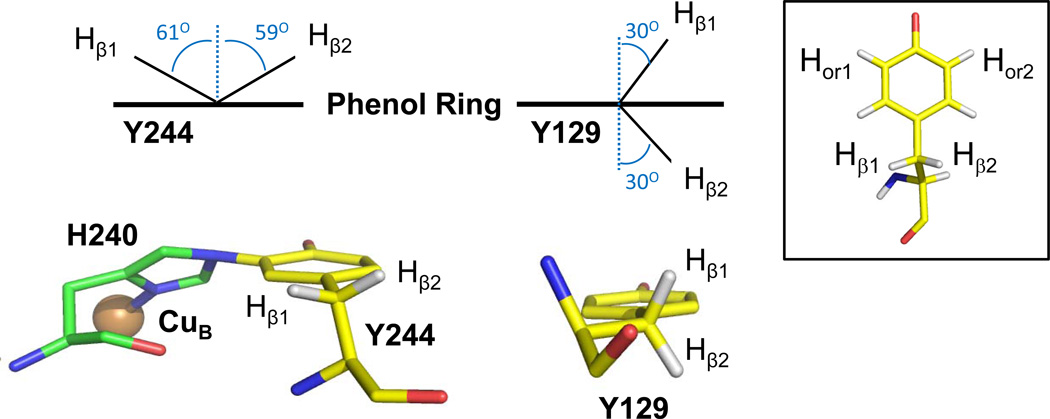

To determine quantitatively the origin of the narrow resonance in bCcO we used the g-values obtained from the D-band data to simulate the X-band data shown in Fig. 3a, with two sets of hyperfine couplings: (1) one ortho proton and two β-methylene protons and (2) two ortho protons and two β-methylene protons (See the inset in Fig. 4). The details of the calculations are described in the Materials and Methods section and the parameters used to fit the data are listed in Table 2. The experimental spectrum is best fit by the simulation of a tyrosine radical on a modified tyrosine in which an ortho proton has been replaced by a covalent bond to another nucleus, but not by the simulation of an unmodified tyrosine radical with two ortho protons. In addition, in order to account for the relatively small hyperfine interactions with the β-methylene protons, the estimated spin density on the Tyr must be reduced by ~20% relative to unmodified tyrosyl radicals, as would be expected due to sharing of the spin density on the covalently linked imidazole.32 The hyperfine coupling of the two β-methylene protons is consistent with an angle θ ~ 60°, which minimizes the resulting total contribution of the hyperfine splitting from both protons to the spectral width.39 Here, θ is defined as the dihedral angle between the Cβ-Hβ bond and pz axis of the α-carbon. In the vicinity of the binuclear center, the only tyrosine with the side chain conformation which gives θ in this range for the β-methylene protons is Y244. Fig. 4 shows the crystal structure of Tyr244 in the resting bovine enzyme, which has angles of 61° and 59° for the β1 and β2 methylene protons.

Figure 4. Crystal structures showing the orientation of Y244 and Y129.

(Left) Crystal structure showing the orientation of Y244 and His240. The Cα—Cβ bond is 31.3° to the plane of the phenol ring. Assuming sp3 geometry, the β-methylene protons are calculated to be 61.3° and 58.7° to the perpendicular axis to the phenol plane. (Right) Crystal structure showing the orientation of Y129. The Cα—Cβ bond is 0.3° to the plane of the phenol ring, and the β-methylene protons are 30.3° and 29.7° to the perpendicular axis of the phenol plane. The inset defines the positions on the tyrosine.

In summary, we assign the 12 G wide radical as residing on the modified tyrosyl, Y244, based on (i) the principal g-values determined from the D-band data and (ii) the linewidth in the X-band CW-EPR spectrum. The narrow linewidth, of the X-band EPR spectrum of Y244, is a result of reduced electron-nuclear hyperfine interactions due to three factors: (1) an ortho-proton is replaced by the covalent bond to nitrogen of His240, eliminating the splitting from the hydrogen nucleus, (2) the β-methylene protons are each ~60° relative to the perpendicular axis to the phenol plane, minimizing their hyperfine contributions, and (3) spin density is shared over the imidazole of the cross-linked His240, reducing the electron spin density coupled to the β-methylene and the ortho proton nuclei.32

EPR characterization of the intermediates formed in the reaction of bCcO with H2O2 at pH 6

At pH 6, 900 µM of H2O2 was reacted with 350 µM bCcO and the X-band spectra of the frozen sample was measured at 77 K. The X-band spectrum (Fig. 5b) shows the presence of two different species, a narrow resonance (width ~12 G) with subtle hyperfine structure, as that reported in Fig. 3a, and a wide resonance (width ~46 G) with extensive hyperfine splitting. To isolate the spectrum of the wide resonance, the narrow resonance was subtracted from the composite spectrum. The resulting spectrum is shown in Fig. 5a. The D-band EPR spectrum obtained at pH 6 also contained the mixture of two radicals (Fig. 5d). When the narrow radical signal (taken from Fig. 3b) is subtracted out, the remaining radical has g-values at gx = 2.0072, gy = 2.0041, and gz = 2.0023 (Fig. 5c). This g-tensor displays classic rhombic symmetry, indicating an unmodified tyrosine with a |gx – gy| of 0.0031, as has been observed for radicals generated on the L-Tyr model compound and for tyrosyl radicals identified in a variety of enzymes.30, 38–40 Furthermore, the high gx definitively rules out a tryptophanyl species, showing that the 46 G radical in the mammalian enzyme is a tyrosyl as reported in the bacterial enzyme.15

Figure 5. X-band and D-band EPR spectra of the intermediates formed in the reaction of CcO with H2O2 at pH 6.

The H2O2 (900 µM) used was ~2.5-fold excess of the enzyme (350 µM). Panels (b) and (d) are the observed spectra obtained at X-band and D-band, respectively while (a) and (c) are the corresponding spectra after subtraction of the 12 G radical. (f) is an expansion of the spectrum in (a) compared to that reported for PdCcO (e).17 The dashed lines in (e) and (f) are to help guide the eye. The dotted lines in (a–d) are simulated spectra with parameters given in Table 1. In the X-band spectra, the contributions from CuA have been removed by subtracting the spectrum of resting oxidized CcO.

Using the g-values obtained from the D-band EPR data, the X-band EPR spectrum can be simulated with two ortho protons and two β-methylene protons each oriented ~30° to the perpendicular axis of the phenol plane. The hyperfine couplings are listed in Table 1. (Consistent with the past studies of Tyr residues, in the simulations contributions of the small hyperfine interactions from the meta protons on the C4 and C4 ring carbons were neglected.47) This orientation puts the Cα—Cβ bond nearly parallel to the phenol plane, which matches the orientation of Y129 seen in the crystal structure (Fig. 4). The uniqueness of this orientation of Y129 has been noted in the past.20 In addition, a similar broad EPR signal was observed and assigned to Y167 in PdCcO (equivalent to Y129 in bCcO); the assignment was confirmed from site-directed mutagenesis studies, in which the broad radical signal disappeared in the Y167F mutant.15 As comparable Tyr radicals are formed in both the bacterial and the mammalian oxidases, the two types of enzymes likely share common radical mechanisms (vide infra).

In prior studies of the reaction of bCcO with H2O2the hyperfine splitting of the broad radical, resulting from the reaction of bCcO with H2O2was not well resolved but ENDOR spectra were obtained from which it was concluded that the broad signal resulted from a tryptophan cation radical which is exchange coupled to the heme iron.14 However, later Svistunenko et al. simulated a hypothetical EPR spectrum from Y129, and showed that it could account for the observed broad signal.20 Although the broad radical we detected in bCcO has approximately the same peak-to-trough width as those reported previously in the bovine enzyme,14 the hyperfine splittings are better resolved. Most interestingly, they exhibit features very similar to the spectra reported for the reaction of PdCcO with H2O2as may be seen in Fig. 5 e–f, further confirming the assignment of the broad radical to Y129 in bCcO and Y167 in PdCcO.

The effect of cyanide on the H2O2 reaction

To assure that the radical species in the reaction of the enzyme with H2O2 originated from heme a3 coordination of the peroxide and was therefore not artifactual, the reactions were repeated in the presence of 10 mM cyanide. The complete coordination of CN− to heme a3 was confirmed by optical absorption spectroscopy (Supporting Information, Fig. S3). No optical changes occurred and no radicals formed upon reacting the CN−-bound enzyme with H2O2indicating that radical formation in the reaction of bCcO with H2O2 involves chemistry initiated at the binuclear center.7, 17, 18, 48

QM/MM simulations

Previous Density Functional Theory calculations on the CcO active site implicated the importance of the Y244-H240 moiety in the proton pumping mechanism,49 but these calculations included only CuB and its ligands, neglecting the role that heme a3 and the surrounding amino acids may play. By using QM/MM techniques, we have been able to model the entire enzyme (plus a 10 Ǻ solvent layer) and treat a large enough quantum mechanical region to describe the electronic wave function. The quantum mechanical region, shown in Fig. 6, includes heme a3 with its oxo and histidine axial ligands, the metal center, CuB, with its three coordinated histidines and the OH group, Y129, Y244, Y292 and W236. The initial state for the calculations was a Compound I species. Typically, Compound I presents two unpaired electrons in the iron-oxo moiety and a third unpaired electron in a porphyrin radical, as a result of an electron transfer to the iron-oxo center. Our data show, following energy optimization, that the spin density is located on Y129 and W236, instead of the porphyrin ring (Fig. 6). It should also be noted that the observation of a radical on W236 is consistent with the data reported in the past.14

As the data reported above showed spin density on Y129 and W236 rather than on Y244, we questioned if the radical formation on Y244 was coupled to proton transfer. Thus, we transferred the proton from the hydroxide group of the Y244 side chain to the oxo atom of Compound I using the water molecule as a bridge. It is noteworthy that the bridging water molecule has been proposed to play a critical role in mediating proton transfer during the oxygen reaction of bCcO by Muramoto et al. 50 Similar water molecules, with a hydrogen bond to the oxo group, have been shown to play important functional roles in other cytochromes, such as P450cam.51 The QM/MM energy profile indicates only a ~0.3 kcal/mol increase in energy when transferring the proton to the oxo atom. As expected, the proton transfer is associated with an electron transfer, reducing the porphyrin π-cation radical, giving a neutral radical localized on Y244. The lower inset of Fig. 6 shows the total spin density map of the product.

These calculations indicate that the radical formation on Y244 is a proton coupled electron transfer as the radical will only form if the OH group becomes deprotonated. In contrast, for Y129 a radical can form without the loss of the proton. The formation of a cation radical on Y129 in the simulations is a result of its very polar environment, although it is readily deprotonated to form the neutral species. The data suggest that radical formation on Y244 is pH sensitive, consistent with our EPR data showing that the relative population of the Y244 radical is decreased at a relatively lower pH (Figs. 3 & 5). To further test the pH sensitivity, a second proton was added to the OH ligand of the CuB center, to form a water ligand. We have recently reported that this ligand is formed spontaneously when adding protons in the active site.34 The tyrosine deprotonation energy profile is now 18 kcal/mol endothermic, suggesting that the radical formation on Y244 is less favorable at low pH.

4. DISCUSSION

In the past we were unable to detect any amino acid-based radicals in the reaction of the fully reduced bCcO (i.e. a 4-electron reduced state) with oxygen,4, 5 possibly due their short lifetime as a result of their rapid reduction by electrons provided by the heme a/CuA centers. To better characterize radicals that may be formed on the enzyme, we have reacted oxidized bCcO with H2O2 as a surrogate for the physiological oxygen reduction reaction and have been able to identify radicals residing on Y244 and Y129.

Association of radical formation with specific intermediates

In bCcO the EPR signal from oxidized CuA serves as an internal reference, so the concentrations of the radicals within a given EPR spectrum can be estimated by their ratio to the CuA signal. Based on the analysis of several samples, we found that the radical populations correspond to 2-5 % of the intermediate concentrations, similar to that reported in prior studies.10, 14, 18 Unfortunately, as the ratio of the broad to narrow radical signals varied with the concentration of the H2O2, we are unable to quantitatively relate the P and F• populations to the radical populations. However, at pH 6 the F• species and the 46 G radical are dominant and at pH 8 the P species and the 12 G radical are dominant.

Several studies have postulated that the absence of a Y244 radical signal in the EPR spectrum is due to spin relaxation or antiferromagnetic coupling with CuB.9, 14, 19, 52, 53 However, if in a fraction of the enzyme, the Tyr-His ligation to CuB is broken or weakened, the Tyr-His radical signal could be recovered in the EPR spectrum. Support for a dynamic change in coordination to CuB comes from the recent report by Muramoto et al.50 in which binding of cyanide to the enzyme caused H290 to be displaced and moved 2.8 Å away from CuB. If the H290 or the Tyr-His moiety is displaced during the H2O2 reaction, the anti-ferromagnetic coupling could be altered, allowing detection of the radical on Y244. An alternative explanation for the substoichiometric EPR signal may be radical migration and eventual quenching by solvent, as it was shown by Chen et al. that the radical generated by the reaction of H2O2 with bCcO can undergo transfer to the surface of the protein.48 However, it is interesting to note that the tyrosine, ortho-substitued with cysteine, in galacatose oxidase is ligated to Cu(II), and that the catalytically relevant radical formed on this moiety is antiferromagnetically coupled to the paramagnetic Cu(II) and thus silent in the X-band EPR spectra.45 Nonethelss, a minority EPR signal is detected in holoenzyme preparations as a result of a decrease or elimination of the antiferromagnetic coupling due to the presence of a small percentage of radicals displaced from the Cu(II) ligation, as is suggested to occur in this work. It is important to note that the detection of this EPR signal in galacatose oxidase provided the first evidence for the key radical formed on the tyrosine crosslinked with cysteine.45

Mechanism of the reaction of CcO with H2O2

The data reported here offer the basis to form a postulated mechanism of the reaction of CcO with H2O2 as summarized in Fig. 1. Initially, the fully oxidized enzyme binds H2O2 to yield a hydroperoxo intermediate. That the H2O2 does in fact bind to the heme as the first step in the reaction is supported by our experiments in which it was found that pre-incubation of the oxidized enzyme with cyanide prevented the formation of any radical intermediates. The O-O bond in the hydroperoxo intermediate is rapidly cleaved, by receiving one electron from the iron atom and one from the heme, releasing an OH− moiety and forming a Compound I type of intermediate in which a π-cation radical is formed on the heme group that we are unable to detect owing to its short lifetime.

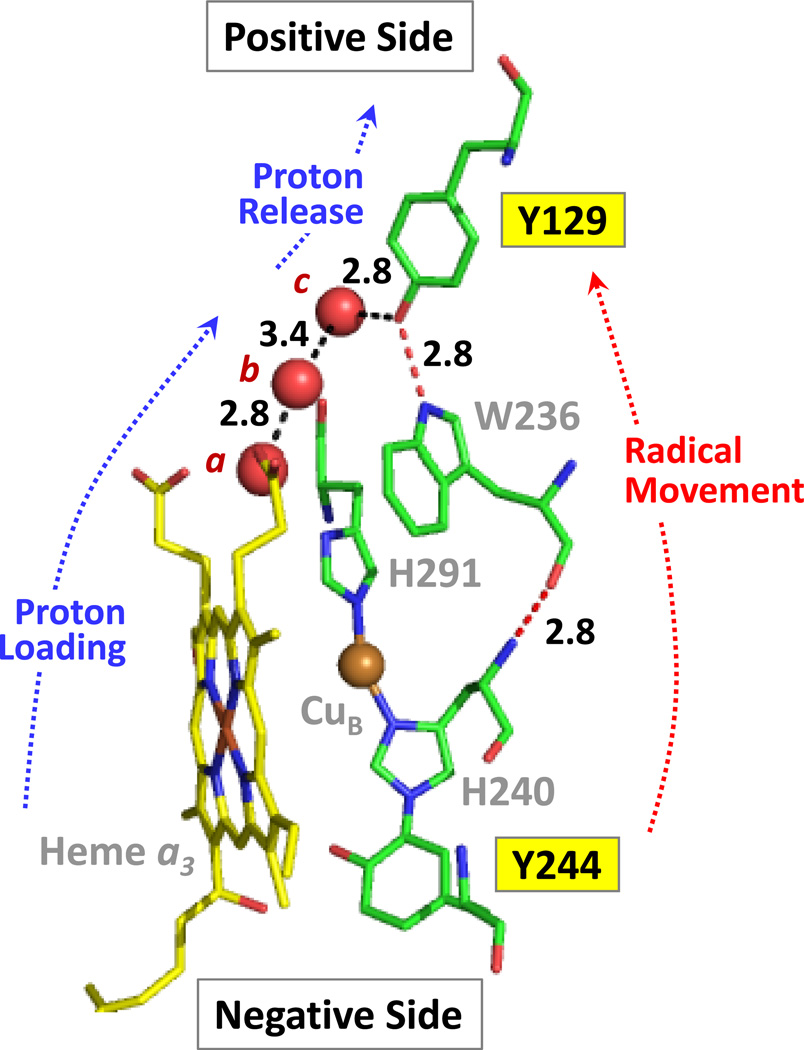

Where the radical ultimately resides depends on the experimental conditions. At high (pH 8) and low (pH 6) pH the radicals on Y244 and Y129 have significant populations, respectively. There are two possible pathways for radical migration from the heme a3 Compound I to Y129. Either the radical could migrate via the D-ring propionate to W236 and to Y129 (Pathway B in Fig. 1) or the radical could migrate first to Y244 and then to Y129 by Pathway A linking the two tyrosines (Y244-H240-W236-Y129) as shown in Fig. 7. Support for the role of W236 in either pathway comes from the W272F and W272M mutations in PdCcO (W272 in PdCcO is equivalent to W236 in bovine) by McMillan et al. in which no radical signals were detected on Y167 in the H2O2 reaction; furthermore, the activity of these mutants was drastically reduced as compared to the wild type enzyme,54 suggesting that radical formation and migration may play a critical role in the enzymatic function. Moreover, in the QM/MM calculations reported here, unpaired electron density was detected on W236, implicating its participation in electron delocalization/transfer. Migration of the radical from Y244 to Y129 requires reprotonation of Y244. This may plausibly occur by acceptance of a proton from the water molecule identified in the crystal structure reported by Muramoto et al.50 Ultimately proton entry into the catalytic site would occur by protons delivered via the D-channel during the oxidative phase of the reaction or via the K-channel during the reductive phase.1

Figure 7. The structure of the heme a3-CuB binuclear center, Y244 and Y129 with respect to the positive and negative sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane.

The red spheres are water molecules that are part of the water cluster near the heme a3 propionates. These three water molecules directly link the propionates of heme a3 to Tyr-129 by an H-bonding network (black dashed lines). The radical migration between Tyr-244 and Tyr-129 may occur through the linked Y244, H240, W236, Y129 network. The H-bond distances (in Å) between water molecules a, b and c and that between c and the oxygen of Y129 are indicated. The figure was made from PDB ID: 3AG3 with PyMol Molecular Graphics Software (Delano Scientific, LLC).

The functional roles of radical formation

A proton loading site, in which protons are stored prior to their release to the positive side of the inner mitochondrial membrane during the proton translocation process, is critical for CcO function. The proton loading site has been widely postulated to reside in the region of the heme a3 propionate groups2 which are bridged by a water molecule (molecule a in Fig. 7 is ~2.65 Å from each propionate carboxyl group). In this region, containing a large cluster of water molecules, a chain of water molecules (a, b and c in Fig. 7) lead directly to Y129 located below the positive side of the inner mitochondrial membrane. Based on the firm assignment of radicals on Y244 and Y129, we postulate that Y129 is a key element of the proton loading site that couples electron transfer to proton translocation. In a given redox state, such as PM, a radical is formed on Y244, which is subsequently reduced by electron transfer from Y129 (i.e. radical migration from Y244 to Y129; Fig. 7) and the associated release of a proton, forming the more stable neutral species, i.e.

| Eq. 4 |

The proton is ejected from Y129 unidirectionally toward the positive side of the membrane, as the proton loading site is “loaded” (i.e. all labile groups in the loading site are fully protonated), and it can’t accept any protons. Proton movement out of the loading site region toward the negative side of the membrane may be blocked by the orientation of E242.55 (See Fig. S4 in the Supporting Information.) Subsequent reduction of the radical, with the formation of a tyrosinate, will increase its proton affinity and promote the uptake of a proton, in particular from water molecule c, which is H-bonded to Y129. It is important to note that the proton must come from this direction, as there are no labile protons within 6 Å above Y129 and below the positive side of the membrane. The water molecule is ultimately re-protonated from protons supplied from the D-channel linking to the negative side of the membrane. This pathway leads to E242, where it is widely accepted that the protons are gated to either the binuclear center for the formation of water or to proton loading site above the heme a3 propionates. This pathway is illustrated in Fig. S4 in the Supporting Information.

In summary, we propose that Y129 is a critical element of the proton loading site; it ejects a proton to the positive side of the membrane during radical formation and abstracts a proton supplied via the D channel during its re-reduction. The unique local environment of Y129 allows it to act as an effective proton diode, which rectifies unidirectional proton movement as it switches between the neutral and the radical form. The assessment of the role of Y129 during each of the steps in the catalytic cycle remains to be investigated.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM074982 and GM098799 to D.L.R. and GM075920 to G.J.G and National Science Foundation Grant NSF0956358 to S.-R.Y. M.A.Y. was supported by the Medical Scientist Training Program (GM07288) at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. S.Y. is supported in part by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 2247012, the Targeted Protein Research Program, and the Global Center of Excellence program, each provided by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. V. G. is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Education CTQ2010-18123.

Footnotes

Supporting Information available: A description of radicals in model complexes and in other proteins. The hyperfine coupling parameters used to simulate the X-band and the D-band EPR spectra of L-Tyr and 2-amino-p-cresol (Table S1) and the listing of the g-values for modified and unmodified tyrosyl radicals (Table S2). The X-band and D-band EPR spectra of L-Tyr (unmodified) irradiated by a mercury arc lamp (Figure S1). The X-band and D-band EPR spectra of 2-amino-p-cresol irradiated by a mercury arc lamp (Figure S2). The Optical absorption difference spectra for the cyanide-adducts of bCcO (Figure S3). The structure of the D- and K-pathways relative to the location of the E242 putative switching element (Figure S4). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belevich I, Verkhovsky MI. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1–29. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brzezinski P, Gennis RB. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:521–531. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9181-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proshlyakov DA, Ogura T, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Yoshikawa S, Appelman EH, Kitagawa T. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29385–29388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu MA, Egawa T, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Yoshikawa S, Yeh SR, Rousseau DL, Gerfen GJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:1295–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu MA, Egawa T, Yeh SR, Rousseau DL, Gerfen GJ. J Magn Reson. 2010;203:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proshlyakov DA, Pressler MA, DeMaso C, Leykam JF, DeWitt DL, Babcock GT. Science. 2000;290:1588–1591. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wrigglesworth JM. Biochem J. 1984;217:715–719. doi: 10.1042/bj2170715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vygodina TV, Konstantinov AA. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;550:124–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb35329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weng LC, Baker GM. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5727–5733. doi: 10.1021/bi00237a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Junemann S, Heathcote P, Rich PR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1456:56–66. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wikstrom M. Biochim Biophys Acta [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proshlyakov DA, Ogura T, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Yoshikawa S, Kitagawa T. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8580–8586. doi: 10.1021/bi952096t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Einarsdottir O, Szundi I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1655:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rich PR, Rigby SE, Heathcote P. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1554:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(02)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Budiman K, Kannt A, Lyubenova S, Richter OM, Ludwig B, Michel H, MacMillan F. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11709–11716. doi: 10.1021/bi048898i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von der Hocht I, van Wonderen JH, Hilbers F, Angerer H, MacMillan F, Michel H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3964–3969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacMillan F, Kannt A, Behr J, Prisner T, Michel H. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9179–9184. doi: 10.1021/bi9911987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabian M, Palmer G. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13802–13810. doi: 10.1021/bi00042a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigby SE, Junemann S, Rich PR, Heathcote P. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5921–5928. doi: 10.1021/bi992614q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Svistunenko DA, Wilson MT, Cooper CE. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1655:372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friesner RA, Guallar V. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2005;56:389–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.55.091602.094410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bathelt CM, Mulholland AJ, Harvey JN. Dalton Trans. 2005:3470–3476. doi: 10.1039/b505407a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guallar V. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:13460–13464. doi: 10.1021/jp806435d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshikawa S, Choc MG, O'Toole MC, Caughey WS. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:5498–5508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mochizuki M, Aoyama H, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Usui T, Tsukihara T, Yoshikawa S. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33403–33411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wikstrom M, Morgan JE. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10266–10273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranguelova K, Girotto S, Gerfen GJ, Yu S, Suarez J, Metlitsky L, Magliozzo RS. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6255–6264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607309200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burghaus O, Rohrer M, Götzinger T, Plato M, Möbius K. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1992;3:765–774. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stone ES, Maki AH. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1962;37:1326–1334. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fasanella EL, Gordy W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969;62:299–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoganson CW, Sahlin M, Sjoberg BM, Babcock GT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:4672–4679. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SH, Aznar C, Brynda M, Silks LA, Michalczyk R, Unkefer CJ, Woodruff WH, Britt RD. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2328–2338. doi: 10.1021/ja0303743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cappuccio JA, Ayala I, Elliott GI, Szundi I, Lewis J, Konopelski JP, Barry BA, Einarsdottir O. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1750–1760. doi: 10.1021/ja011852h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lucas MF, Rousseau DL, Guallar V. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jorgensen WL, Maxwell DS, Tirado-Rives J. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1996;118:11225–11236. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schrodinger . Inc QSite 5.6. Portland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tuukkanen A, Verkhovsky MI, Laakkonen L, Wikstrom M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:1117–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerfen GJ, Bellew BF, Un S, Joseph M. Bollinger J, Stubbe J, Griffin RG, Singel DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Svistunenko DA, Cooper CE. Biophys. J. 2004;87:582–595. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.041046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Un S, Atta M, Fontecave M, Rutherford AW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10713–10719. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duboc-Toia C, Hassan AK, Mulliez E, Ollagnier-de Choudens S, Fontecave M, Leutwein C, Heider J. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:38–39. doi: 10.1021/ja026690j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pogni R, Baratto MC, Teutloff C, Giansanti S, Ruiz-Duenas FJ, Choinowski T, Piontek K, Martinez AT, Lendzian F, Basosi R. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9517–9526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510424200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffman BM, Roberts JE, Swanson M, Speck SH, Margoliash E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:1452–1456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagano Y, Liu JG, Naruta Y, Ikoma T, Tero-Kubota S, Kitagawa T. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14560–14570. doi: 10.1021/ja061507y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whittaker MM, Whittaker JW. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9610–9613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suarez J, Ranguelova K, Jarzecki AA, Manzerova J, Krymov V, Zhao X, Yu S, Metlitsky L, Gerfen GJ, Magliozzo RS. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7017–7029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808106200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hofbauer W, Zouni A, Bittl R, Kern J, Orth P, Lendzian F, Fromme P, Witt HT, Lubitz W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6623–6628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101127598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen YR, Gunther MR, Mason RP. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3308–3314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaila VR, Johansson MP, Sundholm D, Laakkonen L, Wikstrom M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muramoto K, Ohta K, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Kanda K, Taniguchi M, Nabekura H, Yamashita E, Tsukihara T, Yoshikawa S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7740–7745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910410107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Altun A, Guallar V, Friesner RA, Shaik S, Thiel W. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3924–3925. doi: 10.1021/ja058196w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Proshlyakov DA, Pressler MA, Babcock GT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8020–8025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan JE, Verkhovsky MI, Palmer G, Wikstrom M. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6882–6892. doi: 10.1021/bi010246w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacMillan F, Budiman K, Angerer H, Michel H. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1345–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaila VR, Verkhovsky MI, Hummer G, Wikstrom M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6255–6259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800770105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aoyama H, Muramoto K, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Hirata K, Yamashita E, Tsukihara T, Ogura T, Yoshikawa S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2165–2169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806391106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.