Abstract

Tedizolid (formally torezolid) is an expanded-spectrum oxazolidinone with enhanced in vitro potency against Gram-positive pathogens, including methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). The efficacies of human simulated exposures of tedizolid and linezolid against S. aureus in an immunocompetent mouse thigh model over 3 days were compared. Four strains of MRSA and one of MSSA with tedizolid and linezolid MICs ranging from 0.25 to 0.5 and from 2 to 4 μg/ml, respectively, were utilized. Tedizolid or linezolid was administered in a regimen simulating a human steady-state 24-h area under the free concentration-time curve of 200 mg every 24 h (Q24) or 600 mg Q12, respectively. Thighs were harvested after 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h, and efficacy was determined by the change in bacterial density. The mean bacterial density in control mice increased over the 3-day period. After 24 h of treatment, a reduction in bacterial density of ≥1 log CFU was observed for both the tedizolid and linezolid treatments. Antibacterial activity was enhanced for both agents with a reduction of ≥2.6 log CFU after 72 h of treatment. Any statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) in efficacy between the agents were transient and did not persist throughout the 72-h treatment period. The tedizolid and linezolid regimens demonstrated similar in vivo efficacies against the S. aureus isolates tested. Both agents were bacteriostatic at 24 h and bactericidal on the third day of treatment. These data support the clinical utility of tedizolid for skin and skin structure infections caused by S. aureus, as well as the bactericidal activity of the oxazolidinones after 3 days of treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) are frequently caused by Gram-positive pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (35). While vancomycin is still considered the gold standard therapy for MRSA (29), treatment failures have been reported while the infecting pathogen is still susceptible to vancomycin (8, 10, 11, 24, 33). Moreover, studies have suggested a potential for vancomycin “MIC creep” or incremental increases in the MIC over time (22, 28, 34). While these increases have not been noted in national or global surveillance studies to date (13, 30), the reported clinical vancomycin failures, the advocacy for higher vancomycin exposures, and the need for more aggressive concentration monitoring highlight the need for alternative therapies targeting MRSA.

Tedizolid (TR-700, formerly torezolid), the active moiety of tedizolid phosphate is a novel expanded-spectrum oxazolidinone with activity against Gram-positive pathogens (16, 26), including MRSA. Much interest has emerged in comparing the in vitro and in vivo efficacies of TR-700 and the only other FDA approved oxazolidinone, linezolid (LZD), against clinically relevant pathogens. Against S. aureus and other Gram-positive pathogens, TR-700 has shown 4- to 16-fold greater in vitro activity than LZD and may have activity against LZD-resistant strains (3, 12, 15, 31, 32). Additionally, in a phase 2 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of TR-700 for the treatment of ABSSSI, the clinical cure rates were 96.6% and 96.8% for patients with S. aureus and MRSA infections, respectively (6). Our study was undertaken to compare the in vivo efficacies of human simulated exposures of TR-700 and LZD against S. aureus in the immunocompetent murine thigh infection model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antimicrobial test agents.

Analytical-grade tedizolid phosphate and LZD were used for the in vivo analyses. In the in vitro analyses, analytical-grade TR-700 and LZD were utilized. Immediately prior to each in vivo experiment, tedizolid phosphate and LZD were diluted in 0.025 M sodium phosphate dibasic solution and sterile water, respectively, to achieve the desired concentration. The solutions were stored under refrigeration and discarded 24 h after reconstitution.

Bacterial isolates.

Five clinical isolates of S. aureus were utilized in this study. Four isolates were MRSA, including one community-acquired MRSA isolate and three hospital-associated MRSA isolates, of which one was also vancomycin resistant. The remaining isolate was methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA). MICs of both agents were determined by broth microdilution according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (5). Isolates were stored at −80°C in double-strength skim milk (Remel, Lenexa, KS), subcultured twice onto Trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD), and grown for 18 to 24 h at 35°C prior to use in experiments.

Immunocompetent thigh infection model.

Specific-pathogen-free female ICR mice weighing approximately 22 g each were obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN), and utilized throughout these experiments. This study was reviewed and approved by the Hartford Hospital Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were maintained and used in accordance with National Research Council recommendations and were provided food and water ad libitum.

A suspension of each isolate was freshly prepared from the second subculture of each organism and diluted in normal saline to achieve a final inoculum of 108 CFU/ml. Each thigh was inoculated intramuscularly with 0.1 ml of inoculum 2 h prior to the initiation of antimicrobial therapy.

Pharmacokinetic studies and determination of dosing regimen.

Single doses of tedizolid phosphate and LZD were administered to infected, immunocompetent mice to determine a regimen that simulated the human steady-state exposures of 200 mg of TR-700 orally every 24 h and 600 mg of LZD intravenously every 12 h. The target indices were 24-h areas under the free drug concentration-time curve (fAUCs) of 3 μg · h/ml (2, 9) and 137 μg · h/ml (4, 23, 27) for TR-700 and LZD, respectively. The murine protein binding values utilized for TR-700 and LZD were 85% (25) (data on file at Trius Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA) and 30% (1, 14), respectively. The fAUCs for both of the regimens were calculated by using the trapezoidal rule. Blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture from groups of six mice at three or four time points over a 12- to 24-h dosing interval. Plasma (TR-700) and serum (LZD) samples, as dictated by the analytical procedures, were separated and stored at −80°C until analysis. TR-700 concentrations were analyzed by Midwest Bioresearch (Skokie, IL) using a validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay (26). LZD concentrations were analyzed at the Center for Anti-Infective Research and Development laboratory at Hartford Hospital with a modified validated high-performance liquid chromatography assay (36). The standard curve was extended from 20 to 30 μg/ml, and the extraction was modified from deproteinization with 200 ml of acetonitrile to deproteinization with 150 ml of 7.5% trichloroacetic acid with no drying step. The upper and lower limits of quantification of the TR-700 assay were 1,000 and 10 ng/ml, respectively. The upper and lower limits of quantification of the LZD assay were 30 and 0.2 μg/ml, respectively. The intraday percentage coefficients of variation (CV) for the LZD quality control samples of 0.5 and 20 μg/ml were 4.89 and 3.15%, respectively, and the respective interday CV were 3.25 and 2.37%.

In vivo efficacy as assessed by bacterial density.

Five clinical S. aureus isolates were utilized in the immunocompetent thigh infection model to assess the efficacies of humanized exposure regimens of TR-700 and LZD. Two hours after inoculation, groups of three mice were administered the human simulated regimen of TR-700 as a 0.2-ml intraperitoneal injection and LZD as a 0.3-ml subcutaneous injection over a 72-h treatment period. Control mice were administered normal saline at the same time, in the same volume, and by the same route as the most frequent regimen. Groups of three untreated control mice were euthanized by CO2 exposure, followed by cervical dislocation just prior to the initiation of therapy (0 h). Groups of TR-700-treated, LZD-treated, and control mice were sacrificed at 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h. Following sacrifice, both rear thighs were removed and homogenized individually in 5 ml of normal saline. Serial dilutions of thigh homogenate were subcultured onto Trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood for determination of bacterial density. Efficacy, defined as a change in bacterial density, was calculated as the difference in the log10 CFU/ml between the treated and control mice at the respective time points. A comparison of the efficacies of TR-700 and LZD against each isolate at each time point was made by using the Student t test. A P value of <0.05 was defined a priori as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Bacterial isolates.

The phenotypic profiles of the five S. aureus isolates evaluated in this study are listed in Table 1. The TR-700 and LZD MICs for the isolates ranged from 0.25 to 0.5 and from 2 to 4 μg/ml, respectively.

Table 1.

Phenotypic profiles of the S. aureus test isolates used in this study for TR-700 and LZD

| S. aureus isolate | Characteristicsa | MIC (range) in μg/ml |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| TR-700 | LZD | ||

| 152 | HA MRSA | 0.5 | 4 (2–4) |

| 156 | CA MRSA | 0.5 | 4 (2–4) |

| 426 | HA MRSA | 0.25 | 2 |

| 433 | MSSA | 0.5 | 4 |

| 456 | HA MRSA-VRSA | 0.25 | 2 |

HA, hospital acquired; CA, community acquired; VRSA, vancomycin-resistant S. aureus.

Pharmacokinetic determination.

In this study, we were able to define dosing regimens for both TR-700 and LZD to attain humanized 24-h fAUCs. In this model, we achieved exposures that simulated human regimens of TR-700 with a fAUC from time zero to 24 h (fAUC0-24) of 2.99 μg · h/ml and LZD with a fAUC0-24 of 144 μg · h/ml.

In vivo efficacy.

The mean bacterial density of control mice prior to the initiation of dosing was 6.89 log10 CFU, and the mean bacterial density increased to 7.34, 6.94, and 7.08 log10 CFU after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively.

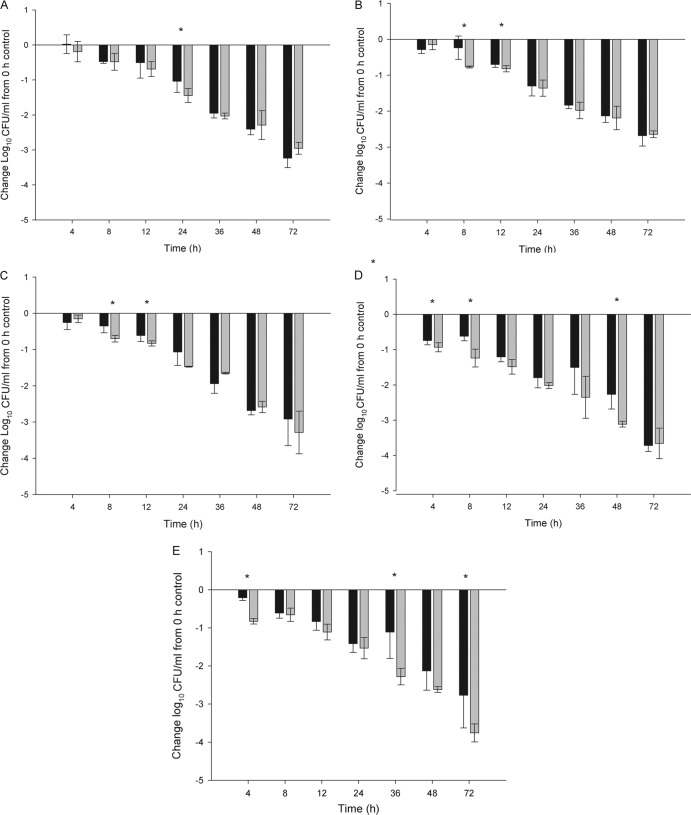

The TR-700 human simulated regimen produced 1.04 to 1.80, 2.13 to 2.68, and 2.68 to 3.72 log10 CFU reductions from the 0-h control at 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively, against all of the isolates in the immunocompetent thigh infection model (Fig. 1A to E). Similarly, reductions of 1.36 to 2.02, 2.19 to 3.11, and 2.64 to 3.76 log10 CFU were observed with the LZD human simulated regimen at the respective time points (Fig. 1A to E). While both agents would be defined as having bacteriostatic activity at 24 h, this activity was enhanced over time. By 72 h, both agents showed a considerable enhancement of overall killing that approximated or exceeded the bactericidal target of 3-log killing. Additionally, no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) between treatments at 24 h was observed, with the exception S. aureus 152 (P = 0.045); however, there was no statistically significant difference between treatments prior to or after 24 h for this isolate. Also, one isolate each at both 48 h (S. aureus 433; P = 0.002) and 72 h (S. aureus 456; P = 0.012) showed a statistically significant difference between treatments in favor of LZD; however, this difference was not identified consistently throughout therapy. When considering the reduction in the bacterial density of the five S. aureus isolates as a whole, the two regimens produced similar reductions in CFU counts over the 72-h treatment period, regardless of the genotype or phenotype.

Fig 1.

Log10 CFU counts of S. aureus 152 (A), 156 (B), 426 (C), 433 (D), and 456 (E) obtained with human simulated TR-700 (black bars) and LZD (gray bars) regimens at selected time points versus those of 0-h controls. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations for three mice per group. An asterisk signifies a statistically significant difference between treatment groups.

DISCUSSION

TR-700, the active moiety of the prodrug tedizolid phosphate, is an oxazolidinone with activity against Gram-positive pathogens, including MRSA. In addition to its spectrum of activity, TR-700 has been postulated to have a lower potential to induce resistance than the only FDA-approved oxazolidinone, LZD (16, 17, 18). In the present analysis, we evaluated the efficacies of human simulated exposures of TR-700 and LZD against a number of S. aureus strains, including MRSA, in an immunocompetent mouse thigh infection model. No sustained statistically significant difference in efficacy against the five S. aureus isolates tested was observed between the human simulated exposures of TR-700 once daily and LZD twice daily. Additionally, as treatment continued past the initial 24 h, enhanced antibacterial activity of both agents was observed, with an approximately 3-log overall bacterial count reduction over the 72-h treatment period.

Similar to LZD efficacy, the pharmacodynamic target associated with TR-700 efficacy is the AUC/MIC ratio (19). Previously, it was noted that a lower AUC/MIC ratio is required for efficacy in immunocompetent mice than in neutropenic mice (7, 20). In the current study, using immunocompetent animals, the human simulated regimen of TR-700 achieved mean total drug AUC0-24/MIC ratios of 79.7 and 39.8 for the isolates with TR-700 MICs of 0.25 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively. For LZD, the pharmacodynamic index associated with efficacy is an AUC0-24/MIC ratio of ≥83 (1, 21, 27) and our human simulated LZD regimen attained mean AUC0-24/MIC ratios of 102.9 and 51.4 for those isolates with LZD MICs of 2 and 4 μg/ml, respectively. While having isolates with higher MICs of both agents would have helped identify the in vivo therapeutic breakpoint, the TR-700 MIC90 for S. aureus is 0.5 μg/ml while the LZD MIC90 is 4 μg/ml; thus, the isolates in the present study represent the upper end of the MIC distribution that would be encountered clinically (31).

In a phase 2 clinical trial using TR-700 in patients with ABSSSI, S. aureus was the most common pathogen, with TR-700 baseline MICs ranging from 0.12 to 0.5 μg/ml (26). For those with S. aureus identified at the baseline, clinical cure rates were >96% and pathogen eradication occurred between 88.9 and 100%, depending on the dose of TR-700 (doses ranged from 200 to 400 mg daily). These data, in conjunction with our murine data, support the continued development of TR-700 for the treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections. The exposure of TR-700 and its reductions of CFU counts noted herein provide pharmacodynamic support for the clinical efficacy observed with this compound. Moreover, the cumulative bactericidal activity that TR-700 displayed over 72 h in this model provides additional pharmacodynamic evidence of its day 3 efficacy (i.e., cessation of lesion spread and resolution of fever), as observed in clinical trials of ABSSSI (6).

TR-700 is a novel expanded-spectrum oxazolidinone with in vitro potency against S. aureus, including MRSA, and has shown positive clinical outcomes in a setting of ABSSSI. In the immunocompetent murine thigh model, human simulated exposures of TR-700 and LZD resulted in similar efficacies against both methicillin-susceptible and -resistant S. aureus. Furthermore, the antibacterial activities of both agents were enhanced as therapy continued out to 72 h. A human simulated TR-700 dosage of 200 mg once daily resulted in efficacy against these S. aureus isolates with MICs up to and including 0.5 μg/ml. These data support the clinical utility and further development of TR-700 for use against S. aureus in the treatment of ABSSSI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Deborah Santini, Lindsay Tuttle, Jennifer Hull, Henry Christensen, Mary Banevicius, Christina Sutherland, Mao Hagihara, and Seth Housman for technical assistance in the performance of this study.

This study was sponsored by a grant from Trius Therapeutics, San Diego, CA.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Andes D, van Ogtrop ML, Peng J, Craig WA. 2002. In vivo pharmacodynamics of a new oxazolidinone (Linezolid). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3484–3489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bien P, et al. 2008. Human pharmacokinetics of TR-700 after ascending single oral doses of the prodrug TR-701, a novel oxazolidinone antibiotic, abstr. F1-2063. Abstr. 48th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown SD, Traczewski MM. 2010. Comparative in vivo antimicrobial activities of torezolid (TR-700), the active moiety of a new oxazolidinone, torezolid phosphate (TR-701), determination of tentative disk diffusion interpretative criteria, and quality control ranges. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2063–2069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buerger C, Plock N, Dehghanyar P, Joukhadar C, Kloft C. 2006. Pharmacokinetics of unbound linezolid in plasma and tissue interstitium of critically ill patients after multiple dosing using microdialysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2455–2463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) 2009. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically approved standard, 8th edition. M07-A8 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Anda C, Das A, Fang E, Prokocimer P. 2011. Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection (ABSSSI) dose-ranging phase 2 tedizolid phosphate (TR-701) study: assessment of efficacy with new FDA guidance, abstr. L1-1496. Abstr. 51st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drusano GL, et al. 2011. Impact of granulocytes on the antimicrobial effect of tedizolid in a mouse thigh infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5300–5305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hidayat LK, Hsu DI, Quist R, Shriner KA, Wong-Beringer A. 2006. High-dose vancomycin therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: efficacy and toxicity. Arch. Intern. Med. 166:2138–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Housman ST, et al. 2011. Pulmonary disposition of torezolid following 200 mg once-daily oral tedizold phosphate in healthy volunteers, abstr. A1-1747. Abstr. 51st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 10. Howden BP, et al. 2004. Treatment outcomes for serious infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:521–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsu DI, et al. 2008. Comparison of method-specific vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration values and their predictability for treatment outcome of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 32:378–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jones RN, Moet GJ, Sader HS, Mendes RE, Castanheira M. 2009. TR-700 in vitro activity against and resistance mutation frequencies among Gram-positive pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:716–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jones RN. 2006. Microbiological features of vancomycin in the 21st century: minimum inhibitory concentration creep, bactericidal/static activity, and applied breakpoints to predict clinical outcomes or detect resistant strains. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:S13–S24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. LaPlante KL, Leonard SL, Andes DR, Craig WA, Rybak MJ. 2008. Activities of clindamycin, daptomycin, doxycycline, linezolid, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and vancomycin against community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with inducible clindamycin resistance in murine thigh infection and in vitro pharmacodynamic models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2156–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Livermore DM, Mushtaq S, Warner M, Woodford N. 2009. Activity of oxazolidinone TR-700 against linezolid-susceptible and -resistant staphylococci and enterococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:713–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Locke JB, Hilgers M, Shaw KJ. 2009. Novel ribosomal mutations in Staphylococcus aureus strains identified through selection with the oxazolidinones linezolid and torezolid (TR-700). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:5265–5274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Locke JB, Hilgers M, Shaw KJ. 2009. Mutations in ribosomal protein L3 are associated with oxazolidinone resistance in staphylococci of clinical origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:5275–5278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Locke JB, et al. 2010. Structure-activity relationships of diverse oxazolidinones for linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains possessing the cfr methyltransferase gene or ribosomal mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:5337–5343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Louie A, Lui W, Kulawy R, Drusano GL. 2011. In vivo pharmacodynamics of torezolid phosphate (TR-701), a new oxazolidinone antibiotic, against methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains in a mouse thigh infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3453–3460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Louie A, et al. 2009. Defining the impact of granulocytes on the kill of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) by the new oxazolidinone prodrug TR-701, abstr. A1-1935. Abstr. 49th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 21. MacGowan AP. 2003. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of linezolid in healthy volunteers and patients with Gram-positive infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51(Suppl 2):ii17–ii25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mason EO, et al. 2009. Vancomycin MICs for Staphylococcus aureus vary by detection method and have subtly increased in a pediatric population since 2005. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1628–1630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meagher AK, Forrest A, Rayner CR, Birmingham MC, Schentag JJ. 2003. Population pharmacokinetics of linezolid in patients treated in a compassionate-use program. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:548–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Neoh H, et al. 2007. Impact of reduced vancomycin susceptibility on the therapeutic outcome of MRSA bloodstream infections. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 6:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pichereau S, et al. 2009. Comparative pharmacodynamics of novel oxazolidinone, torezolid phosphate (TR-701), against S. aureus in the neutropenic murine pneumonia model, abstr A1-1939. Abstr 49th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prokocimer P, et al. 2011. Phase 2, randomized, double-blind, dose-ranging study evaluating the safety, tolerability, population pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of oral torezolid phosphate in patients with complicated skin and skin structure infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:583–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rayner CR, Forrest A, Meagher AK, Birmingham MC, Schentag JJ. 2003. Clinical pharmacodynamics of linezolid in seriously ill patients treated in a compassionate use programme. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 42:1411–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rhee KY, Gardiner DF, Charles M. 2005. Decreasing in-vitro susceptibility of clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates to vancomycin at the New York Hospital: quantitative testing redux. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1705–1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rybak M, et al. 2009. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 66:82–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sader HS, et al. 2009. Evaluation of vancomycin and daptomycin potency trends (MIC creep) against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected in nine U.S. medical centers from 2002 to 2006. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4127–4132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schaadt R, Sweeney D, Shinabarger D, Zurenko G. 2009. In vitro activity of TR-700, the active ingredient of the antibacterial prodrug TR-701, a novel oxazolidinone antibacterial agent. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3236–3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shaw KJ, et al. 2008. In vitro activity of TR-700, the antibacterial moiety of the prodrug TR-701, against linezolid-resistant strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4442–4447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Soriano A, et al. 2008. Influence of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration on the treatment of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Steinkraus G, White R, Friedrich L. 2007. Vancomycin MIC creep in non-vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA), vancomycin susceptible clinical methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) blood isolates from 2001-05. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:788–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stevens DL, et al. 2005. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:1373–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tobin CM, Sunderland J, White LO, MacGowan AP. 2001. A simple, isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography assay for linezolid in human serum. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:605–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]