Abstract

The first structure of a catalytic domain from a hyperthermophilic archaeal viral integrase reveals a minimal fold similar to that of bacterial HP1 integrase and defines structural elements conserved across three domains of life. However, structural superposition on bacterial Holliday junction complexes and similarities in the C-terminal tail with that of eukaryotic Flp suggest that the catalytic tyrosine and an additional active-site lysine are delivered to neighboring subunits in trans. An intramolecular disulfide bond contributes significant thermostability in vitro.

TEXT

Lysogenic viral life cycles in which viral DNA integrates within the host genome are employed in each of the three domains of life: Eukarya, Bacteria, and Archaea. Mechanistically, the integration of viral DNA is an example of site-specific recombination, and enzymes responsible for integration fall into two categories, tyrosine and serine recombinases. Despite similar activities, these recombinase families are unrelated in protein sequence and structure and employ different recombination mechanisms (12, 25).

Tyrosine recombinases like the well-known integrase from bacteriophage λ, or Cre, which is involved in dimer reduction of phage P1 plasmids, are composed of a variable N-terminal DNA binding domain and a C-terminal catalytic domain. Though unexpectedly diverse, the catalytic domains generally contain 6 well-conserved active-site residues within a 40-residue C-terminal segment (3). This includes a nucleophilic tyrosine that attacks DNA, expelling a 5′-hydroxyl group to form a covalent adduct. This is followed by the reverse reaction, in which an incoming DNA strand displaces the tyrosine, religating the DNA to form a Holliday junction (HJ) intermediate. This reaction cycle is then repeated to complete DNA integration, or excision.

Structural studies of phage and bacterial tyrosine recombinases have provided detailed information on the structure of the catalytic domain alone and for complete enzymes complexed with DNA in several mechanistically important states, including tetrameric recombinase assemblies on the HJ intermediate (1, 7, 11, 13–15, 17, 20). Structural studies of the tetrameric HJ complex have also been completed for Flp, a eukaryotic tyrosine recombinase (8, 10). The latter works revealed that unlike the bacterial enzymes, the eukaryotic Flp contains a “helix-swapped” C terminus, such that the active-site tyrosine is provided to the neighboring catalytic subunit in trans.

Tyrosine recombinases have also been identified in archaea. Among the first to be identified was the viral integrase from Sulfolobus spindle-shaped virus 1 (IntSSV) (3). Its role in the viral life cycle and its enzymatic activity have been studied in some detail (9, 18, 22–24). While IntSSV displays minimal sequence similarity to the bacterial or eukaryotic integrases, with even the putative “conserved” active-site residues showing significant variability, mechanistic studies have suggested that it may also assemble its active site in trans (3, 18). However, we lack confirming structural information for IntSSV or any other archaeal tyrosine recombinase. For these reasons, the structure of IntSSV is of considerable interest.

Structure of the IntSSV catalytic domain.

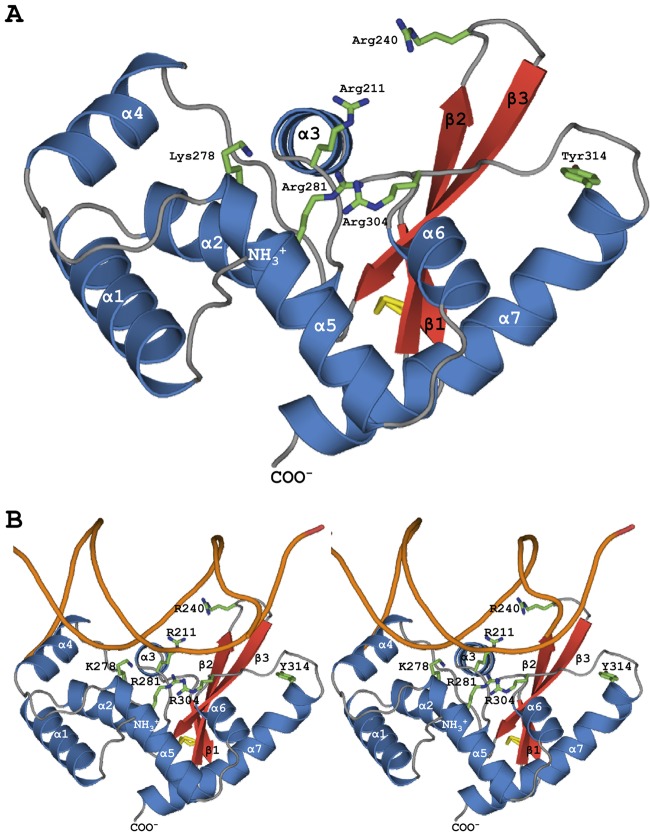

With minor modifications described in the supplemental material, IntSSV was cloned (21), expressed, and purified and its structure (Protein Data Bank identifier [PDB ID], 3UXU) determined by multiwavelength anomalous diffraction at the Se edge as previously described (19). Full-length IntSSV runs as a monomer on a Superdex S75 column and has a calculated mass of 39.8 kDa. However, N-terminal sequencing and mass spectrometry of dissolved crystals indicated subsequent, serendipitous in situ proteolysis (4) leading to crystallization of only the C-terminal domain, residues 173 to 335. BLAST searches against the PDB do not identify similarity to any integrase, but consistent with the results of previous bioinformatics and biochemical work (3, 18, 24), the structure revealed an unembellished integrase catalytic core composed of three successive alpha helices (α1 to α3) followed by a three-stranded, up-and-down, antiparallel β-sheet (β1 to β3) and four additional helices (α4 to α7) (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

(A) IntSSV catalytic domain. The structure reveals a minimal integrase fold with similarity to that of bacterial HP1 (Dali Z score, 10.6) (Table 1). Superposition on HP1 indicates that 5 (ArgI, Lysβ, HisII, ArgII, His/Trp) of 6 hallmark active-sites residues correspond to Arg211 (ArgI), Arg240 (Lysβ), Lys278 (HisII), Arg281 (ArgII), and Arg304 (His/Trp). However, the proposed catalytic Tyr (Tyr314) is distant from these first 5 active-site residues and the catalytic tyrosine in HP1, suggesting that like the eukaryotic Flp enzyme, IntSSV may provide the catalytic tyrosine to a neighboring subunit in trans. (B) Superpositional (stereo pair) docking of IntSSV on one arm of the eukaryotic Flp HJ complex (Z score, 9.1) (Table 1) suggests potential interactions for the first 5 active-site residues with the substrate DNA. Again, however, the putative active-site Tyr is distant from the ribose-phosphate backbone and is found on the back face of the subunit.

A disulfide bond between Cys227 and Cys232 cross-links β1 and β2. Because disulfides in cellular proteins of crenarchaeal viruses can enhance thermostability (17a, 17b, 17c, 21a), we determined the melting temperatures (Tm) of full-length IntSSV in the absence and presence of a reducing agent using differential scanning fluorometry and found a ΔTm of 9°C (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). As they are the only cysteines in IntSSV, the increased thermostability is likely due to this disulfide, suggesting that introduction of IntSSV-like disulfides into other recombinases might enhance their many applications in biotechnology.

A structural homology search with the program DALI (16) (Table 1) identifies greatest similarity to the catalytic domain of bacteriophage HP1 integrase (15), which also contains a catalytic core that is minimal relative to those of more-elaborate structures, like λ-integrase (17), Cre (13), Vibrio cholerae IntI (VcIntI) (20), and eukaryotic Flp (8, 10). However, after the β-sheet in IntSSV, α4 of HP1 is replaced with an extended stretch of polypeptides. Thus, IntSSV α4 to α7 correspond to HP1 α5 to α8 and IntSSV appears even more Spartan than HP1 and may define a minimal integrase fold.

Table 1.

IntSSV structural superpositions

| Tyr recombinase | PDB ID | Z score | RMSD (Å)a | No. of equivalent residues (of 159 in IntSSV) | % identity to equivalent residues | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP1 integrase | 1AIH | 10.6 | 2.6 | 121 | 17 | 15 |

| Flp recombinase | 1M6X | 9.1 | 3.1 | 142 | 9 | 8, 10 |

| V. cholera Int1 | 2A3V | 8.9 | 2.5 | 121 | 15 | 20 |

| λ integrase | 1AE9 | 8.7 | 2.9 | 123 | 12 | 17 |

| Cre | 3CRX | 7.8 | 3.3 | 121 | 10 | 13 |

RMSD, root mean square deviation.

However, we note a critical difference, namely, that the C-terminal helices in IntSSV (α7) and HP1 (α8) are not in structurally equivalent positions (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Related to this, a hallmark of tyrosine recombinases is the conservation of six noncontiguous residues involved in catalyzing DNA strand cleavage and strand exchange: ArgI, Lysβ, HisII, ArgII, His/Trp, and Tyr (18, 24, 25). Sequence alignments and mechanistic studies suggest that these correspond to Arg211 (Argi), Arg240 (Lysβ), Lys278 (Hisii), Arg281 (Argii), Arg304 (His/Trp), and Tyr314 (Tyr) in IntSSV and that 3 of the 6 residues are thus divergent from the consensus motif (18, 24). Importantly, while the superposition of IntSSV on HP1 confirms the predicted structural equivalence for the first 5 residues, the nucleophilic tyrosine present at the N terminus of IntSSV α7 is found on a different face of the domain, displaced from its counterpart in HP1 (Tyr 315) by ∼25 Å (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material).

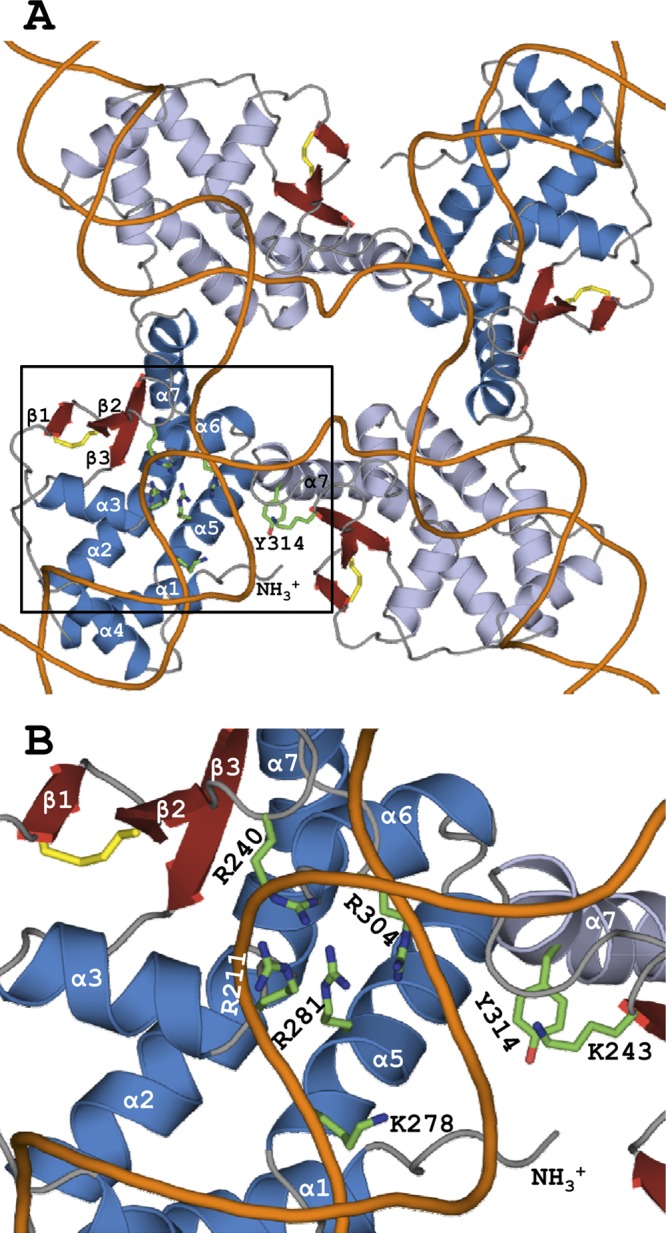

In contrast, IntSSV α7 does superpose on helix N of the eukaryotic Flp HJ complex (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material), where the N-terminal end of IntSSV α7 and Tyr314 approach within 8 Å of Flp's catalytic Tyr343, present at the C terminus of helix M. This suggests that, like Flp, IntSSV may assemble its active site in trans, donating the catalytic Tyr to a neighboring subunit as the synaptosome assembles the expected IntSSV tetramer on target DNA (8, 10). Further support for this comes from the tetrameric bacterial HJ complexes, particularly Cre, where IntSSV superposition on protomer A positions the IntSSV catalytic tyrosine within 4.5 Å of Cre Tyr324 in protomer D (Fig. 2). Similarly, when superposed on subunits A or D of VcIntI, the IntSSV catalytic tyrosine is intermediate between the positions of VcIntI Tyr324 in the D and C subunits. Importantly, this interpretation is also consistent with the mutational analysis of IntSSV by Letzelter et al., who also concluded that DNA cleavage occurs in trans, at least when topoisomerase IB activity was used to report activity (18). Delivery of the active-site tyrosine in trans is an attractive mechanism for controlling the requisite “half-of-sites” reactivity that is integral to DNA integration and excision and appears to be utilized in both the archaeal and eukaryotic domains of life.

Fig 2.

Quaternary structure and active-site assembly in trans. (A) Superpositional docking of IntSSV protomers on Cre HJ DNA (Z score, 7.8). IntSSV subunits superpositioned on chains A and B of the Cre HJ complex are shown in blue and light blue, respectively, with the disulfide bond in yellow. Five of the six hallmark active-site residues are shown for chain A, while catalytic Tyr314 is instead depicted on chain B, along with the strictly conserved Lys243. Though not depicted, similar active-site constellations are found at the other subunit interfaces. Note that Tyr314 closely approaches the DNA arm bound by the adjacent subunit (dark blue) but is quite distant from the DNA arm bound by its own subunit (light blue). (B) The square circumscribing the active site in panel A is enlarged. The distribution of putative active-site residues across the subunit interface suggests that both Tyr314 and Lys243 are provided to the neighboring subunit in trans.

A multiple-sequence alignment of 44 IntSSV-like sequences identifies 6 invariant residues (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), each within the catalytic domain. Arg211 (Argi), Arg281 (Argii), and the catalytic tyrosine (Tyr314) have been described above; the others are Gly209, which is next to Arg211 and appears to be structural, Lys243, and Tyr325. Though side-chain density for Lys243 is poor, its location suggests that this strictly conserved residue is also delivered in trans to the active site of a neighboring subunit (Fig. 2), where it might participate in DNA recognition or catalysis.

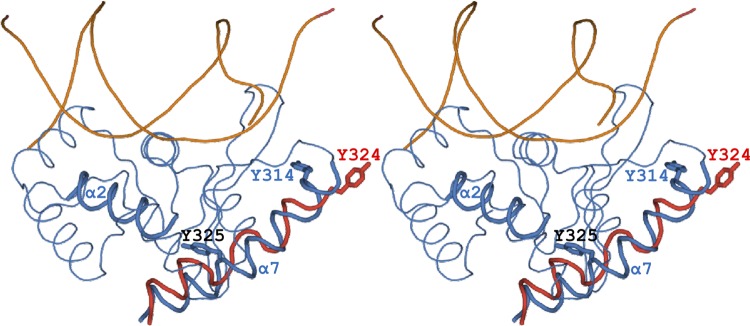

The invariant Tyr325 is found in the C-terminal half of helix α7, which occupies a structurally conserved cleft (Fig. 3). One wall of this cleft is formed by portions of strands β2 and β3, a second by helices α5 and α6, and a third by the C terminus of α2. As the α6-α7 loop leaves the active site, it makes a reverse turn that places the α7 helix on the back side of the α5 and α6 helices, filling this cleft. The importance of this interaction is highlighted by Tyr325, which forms a hydrogen bond that caps the C-terminal end of helix α2, helping to anchor α7 within the structurally conserved cleft.

Fig 3.

Stereo IntSSV (blue) and Flp (not shown) utilize a conserved binding cleft to accommodate their C-terminal α-helices. IntSSV Tyr325 (black) in helix α7, which is strictly conserved in the 44 IntSSV-like sequences (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), forms a hydrogen bond that caps the C-terminal end of helix α2, helping to anchor the C-terminal α7 helix. The bacterial enzymes, including Cre (shown in red), also utilize this conserved cleft, at least when assembled on the four arms of the HJ complex. However, rather than using the intrasubunit interactions seen in IntSSV and Flp, they instead accommodate a C-terminal extension from a neighboring subunit. Thus, when IntSSV is superpositioned on one subunit in the Cre HJ complex, αN from a neighboring Cre subunit (red) falls upon α7 (blue). Also shown are the catalytic tyrosines of IntSSV (Tyr314; blue) and Cre from the neighboring subunit (Tyr324; red). While the IntSSV catalytic tyrosine is less than 5 Å from the catalytic tyrosine in the neighboring Cre subunit, it is 25 Å from the catalytic tyrosine in the equivalent Cre subunit.

Returning to the bacterial complexes, when IntSSV is superpositioned on the tetrameric Cre HJ complex, we find that αN from a neighboring Cre subunit is superposed on IntSSV α7 (Fig. 3). Thus, at the quaternary level, this extension from the neighboring Cre subunit is accommodated by the same structurally conserved cleft that we see in IntSSV and Flp. Similarly, C-terminal extensions from a neighboring subunit in the λ integrase and VcIntI HJ complexes also position within this cleft, as does HP1 α9 when IntSSV is superpositioned on the HP1 dimer in the absence of DNA. Thus, considering tertiary- and quaternary-level structures, these cleft-helix interactions are conserved across the three domains of life, although the lengths and conformations of the helices do vary. This helix swapping is directly analogous to domain swapping, a generally recognized mechanism for forming oligomeric proteins from individual subunits (5, 6). From this point of view, it is actually the bacterial tyrosine recombinases, as opposed to IntSSV and Flp, that are helix or domain swapped. Overall, donation of the active-site tyrosine in trans and the lack of helix swapping suggest that IntSSV is more similar to the eukaryotic rather than the bacterial enzymes. This is consistent with the observation that archaeal enzymes in nucleic acid metabolism are frequently more similar to their eukaryotic than to their bacterial counterparts (2). However, the minimal sequence identity between IntSSV and the bacterial and eukaryotic enzymes also suggests that IntSSV and the fuselloviridae in general are deeply rooted within the archaeal domain.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant MCB-0920312).

Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 May 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aihara H, Kwon HJ, Nunes-Duby SE, Landy A, Ellenberger T. 2003. A conformational switch controls the DNA cleavage activity of lambda integrase. Mol. Cell 12:187–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allers T, Mevarech M. 2005. Archaeal genetics—the third way. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6:58–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Argos P, et al. 1986. The integrase family of site-specific recombinases: regional similarities and global diversity. EMBO J. 5:433–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bai Y, Auperin TC, Tong L. 2007. The use of in situ proteolysis in the crystallization of murine CstF-77. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 63:135–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bennett MJ, Choe S, Eisenberg D. 1994. Domain swapping: entangling alliances between proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:3127–3131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bennett MJ, Schlunegger MP, Eisenberg D. 1995. 3D domain swapping: a mechanism for oligomer assembly. Protein Sci. 4:2455–2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Biswas T, et al. 2005. A structural basis for allosteric control of DNA recombination by lambda integrase. Nature 435:1059–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen Y, Narendra U, Iype LE, Cox MM, Rice PA. 2000. Crystal structure of a Flp recombinase-Holliday junction complex: assembly of an active oligomer by helix swapping. Mol. Cell 6:885–897 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clore AJ, Stedman KM. 2007. The SSV1 viral integrase is not essential. Virology 361:103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conway AB, Chen Y, Rice PA. 2003. Structural plasticity of the Flp-Holliday junction complex. J. Mol. Biol. 326:425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gopaul DN, Guo F, Van Duyne GD. 1998. Structure of the Holliday junction intermediate in Cre-loxP site-specific recombination. EMBO J. 17:4175–4187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grindley ND, Whiteson KL, Rice PA. 2006. Mechanisms of site-specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:567–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guo F, Gopaul DN, Van Duyne GD. 1999. Asymmetric DNA bending in the Cre-loxP site-specific recombination synapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:7143–7148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo F, Gopaul DN, van Duyne GD. 1997. Structure of Cre recombinase complexed with DNA in a site-specific recombination synapse. Nature 389:40–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hickman AB, Waninger S, Scocca JJ, Dyda F. 1997. Molecular organization in site-specific recombination: the catalytic domain of bacteriophage HP1 integrase at 2.7 A resolution. Cell 89:227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holm L, Sander C. 1993. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 233:123–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kwon HJ, Tirumalai R, Landy A, Ellenberger T. 1997. Flexibility in DNA recombination: structure of the lambda integrase catalytic core. Science 276:126–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a. Larson ET, et al. 2007. A winged-helix protein from sulfolobus turreted icosahedral virus points toward stabilizing disulfide bonds in the intracellular proteins of a hyperthermophilic virus. Virology 368:249–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Larson ET, et al. 2007. A new DNA binding protein highly conserved in diverse crenarchaeal viruses. Virology 363:387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17c. Lawrence CM, et al. 2009. Structural and functional studies of archaeal viruses. J. Biol. Chem. 284:12599–12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Letzelter C, Duguet M, Serre MC. 2004. Mutational analysis of the archaeal tyrosine recombinase SSV1 integrase suggests a mechanism of DNA cleavage in trans. J. Biol. Chem. 279:28936–28944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lintner NG, et al. 2011. The structure of the CRISPR-associated protein Csa3 provides insight into the regulation of the CRISPR/Cas system. J. Mol. Biol. 405:939–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. MacDonald D, Demarre G, Bouvier M, Mazel D, Gopaul DN. 2006. Structural basis for broad DNA-specificity in integron recombination. Nature 440:1157–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Menon SK, Eilers BJ, Young MJ, Lawrence CM. 2010. The crystal structure of D212 from sulfolobus spindle-shaped virus ragged hills reveals a new member of the PD-(D/E)XK nuclease superfamily. J. Virol. 84:5890–5897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a. Menon SK, et al. 2008. Cysteine usage in Sulfolobus spindle-shaped virus 1 and extension to hyperthermophilic viruses in general. Virology. 376:270–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Muskhelishvili G. 1994. The archaeal SSV integrase promotes intermolecular excisive recombination in vitro. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 16:605–608 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Muskhelishvili G, Palm P, Zillig W. 1993. SSV1-encoded site-specific recombination system in Sulfolobus shibatae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 237:334–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Serre MC, Letzelter C, Garel JR, Duguet M. 2002. Cleavage properties of an archaeal site-specific recombinase, the SSV1 integrase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:16758–16767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Duyne GD. 2002. A structural view of tyrosine recombinase site-specific recombination, p 93–117 In Craig NL, Craige R, Gellert M, Lambowitz AM. (ed), Mobile DNA II. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.