Abstract

Cone-rod homeobox (Crx) encodes Crx, a transcription factor expressed selectively in retinal photoreceptors and pinealocytes, the major cell type of the pineal gland. Here, the influence of Crx on the mammalian pineal gland was studied by light and electron microscopy and by use of microarray and qRTPCR technology, thereby extending previous studies on selected genes (Furukawa et al. 1999). Deletion of Crx was not found to alter pineal morphology, but was found to broadly modulate the mouse pineal transcriptome, characterized by a >2-fold downregulation of 543 genes and a >2-fold upregulation of 745 genes (p < 0.05). Of these, one of the most highly upregulated (18-fold) is Hoxc4, a member of the Hox gene family, members of which are known to control gene expression cascades. During a 24-hour period, a set of 51 genes exhibited differential day/night expression in pineal glands of wild-type animals; only eight of these were also day/night expressed in the Crx−/− pineal gland. However, in the Crx−/− pineal gland 41 genes exhibit differential night/day expression that is not seen in wild-type animals. These findings indicate that Crx broadly modulates the pineal transcriptome and also influences differential night/day gene expression in this tissue. Some effects of Crx deletion on the pineal transcriptome might be mediated by Hoxc4 upregulation.

Keywords: Crx, Hoxc4, microarray, pineal gland, transcriptome profiling, gene expression

INTRODUCTION

Cone-rod homeobox (Crx) is a homeodomain transcription factor and member of the Otx family; Crx has been thought to play a critical role in determining and maintaining the phenotype of both pinealocytes and retinal photoreceptors (Chen et al. 1997; Furukawa et al. 1997; Rath et al. 2006; Rath et al. 2007). The selective expression of Crx in these cell types reflects their common evolutionary origin (Klein 2004; Mano and Fukada 2007). In the mammalian retina, Crx is essential for the normal development and maintenance of cones and rods (Furukawa et al. 1999) and regulates expression of the network of genes that characterize the retina (Hsiau et al. 2007). Elimination of Crx by disruption of the homeobox domain results in loss of the image-forming visual system (Furukawa et al. 1999) but not the non-image-forming visual system controlling circadian rhythms (Panda et al. 2003; Rovsing et al. 2010). Crx−/− mice exhibit suppressed circadian rhythms in locomotor activity, suggesting that Crx may directly or indirectly alter retinal ganglion cell output, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, other structures controlling locomotor activity, or a combination (Rovsing et al. 2010).

Whereas it is clear that the retina is severely impacted in the Crx−/− animal, the full impact of Crx deletion on the pineal gland is less clear. Studies on mouse pineal gland and on gene expression have indicated that Crx does not appear to alter pineal morphology, but does moderately modulate the abundance of Aanat transcripts (Li et al. 1998; Furukawa et al. 1999); Aanat is of special importance in the pineal gland because it encodes the enzyme that regulates the daily rhythm in melatonin production in vertebrates (Klein 2007). Studies in the chicken indicate that Crx is also involved in the control of expression of the last enzyme in melatonin synthesis, Asmt/Hiomt (acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase/ hydroxyindole O-methyltransferase) (Bernard et al. 2001).

In the current report, we have pursued the goal of determining the full impact of Crx deletion on the pineal gland using anatomical methods and microarray technology, which has not been used previously to study the adult mouse pineal gland. Our results indicate that Crx plays a very broad role in modulating the pineal transcriptome and that a link exists between Crx and the homeobox gene Hoxc4.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Crx−/− mice were provided by Dr. Connie Cepko. The Crx−/− mice were made on a 129sv background (Furukawa et al. 1999), 129sv mice were used as wild-type controls in the current study. Genotypes were identified by use of primers detecting Crx (Table 1) and primers detecting the neo cassette in Crx−/− mice, which amplify a 470 bp fragment not detected in the wild-type mouse. Wild-type and Crx−/− mice (male and female, > two months of age) were bred and kept in a 12L:12D light cycle with food and water ad libitum. To collect tissue, animals were euthanized with CO2 and decapitated at ZT (zeitgeber time) 6 or ZT20. The skull cap was carefully removed with the intention not to alter the position of the superficial pineal gland. The gland was then located on the skull, removed and cleaned of extraneous tissue. Dim red light was used when animals were euthanized at ZT20. For microarray analysis, pineal glands were immediately frozen on Dry Ice, then stored at −80°C in pools of eight glands; for qRT-PCR, pools of three to eight glands were prepared similarly. For radiochemical in situ hybridization histology, pineal glands from five wild-type animals and five Crx−/− animals were used. For Affymetrix GeneChip analysis and qRT-PCR, three pools were analyzed per time point. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of EU Directive 86/609/EEC (approved by the Danish Council for Animal Experiments) and the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Table 1. Primer sequences for genotyping, quantitative real-time RT-PCR analyses and cloning.

Where accession numbers are not available, Entrez Gene identifiers are given.

| Gene | GenBank Accession number |

position | Forward primer 5'-3' | Reverse primer 5'-3' |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping | ||||

| Crx | NM_007770.4 | 461–770 | GCAGCGACAGCAGCAGAAACA | ATGACCTATGCCCCGGCTTCT |

| Neo | - | 274–975 | ATGGATTGCACGCAGGTTCTC | GATCTGGACGAAGAGCATCAG |

| qPCR | ||||

| Aanat | NM_009591.3 | 4–105 | TGCAGTCAGGAGTCTCAGCTT | AAGTGCTCCCTGAGCAACAG |

| Actb | NM_007393.2 | 414–550 | CTAAGGCCAACCGTGAAAAG | GTCTCCGGAGTCCATCACAAT |

| Ap1g1 | NM_009677.3 | 2489–2641 | GAGCTAGACATGACGGACTTTG | CAGCTGTTGCTTCTGTGGAT |

| B2m | NM_009735.3 | 111–211 | TATCCAGAAAACCCCTCAAAT | GAGGCGGGTGGAACTGTGTTA |

| Cpm | NM_027468 | 984–1139 | AAGTGTTCGATCAGAGTGGAGC | CGTGTCCAGGGACTGTAACAT |

| Cry1 | NM_007771 | 872–1015 | TCAATTGAGTATGATTCTGAGCCT | TCCGCCATTGAGTTCTATGATC |

| Gapdh | XM_001473623.1 | 77–178 | TGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACG | AGGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACAA |

| Gm626 | 268729 | 319–473 | GGGAGCGAGAGTGACTGG | GATGAAAATCAGCTGAGGGC |

| Gng4 | NM_010317 | 210–368 | GGAGTGCAGGAATGAAGGAA | GCACGTGGGCTTCACAGTA |

| Hoxc4 | NM_013553 | 1726–1867 | GGAGGACAGCAAACAAAGCTA | TAACCACGATGAGGGTAGGG |

| Pde10a | NM_011866 | 372–518 | GAAGGCTGACCGAGTGTTTC | TGGTTTTCCTCTTCAGCCAC |

| Pvr | NM_027514 | 454–606 | TTCCCCAGAGGCAGTAGAAG | AGAGATTCGTCCAGGAGGGT |

| Rasgrf 1 | NM_011245 | 1757–1911 | GAGGGCTGTGAGATCCTCCT | GAATAGGAAACACTGGCGCT |

| Rps27a | NM_024277 | 232–376 | GAAGACCCTTACGGGGAAAA | GCCATCTTCCAGCTGCTTAC |

| Snap25 | NM_011428.3 | 93–244 | GCTCCTCCACTCTTGCTACC | GCTCATTGCGCATGTCTGCG |

| Ube2d2 | NM_019912.2 | 389–533 | GGCTCTGAAGAGAATCCACAA | TACTCCACCCTGATAGGGGC |

| 1700042O10RIK | 73321 | 836–988 | CTGCATAGATTTTGCACGGA | TAACTGAGGGTTGATTGGGG |

| PCR for cloning | ||||

| Hoxc4 | NM_013553 | 61–465 | GGTGTGCAATGGTGAGCACC | TGGAATCCCGATTCCCTGGT |

| Hoxc4 | NM_013553 | 351–965 | TGGACTCTAACTACATCGAT | TCTTCCATTTCATACGACGGT |

| Hoxc4 | NM_013553 | 861–1867 | ACCGCTACCTGACCCGAAGG | TAACCACGATGAGGGTAGGG |

The primers generate a Neo derived product within this area.

Microarray

RNA was purified using the RNeasy micro kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (including DNase treatment); high quality was verified using the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). A commercially available kit (Nugen Ovation RNA amplification system V2, NugenTech, San Carlos, CA) was used to convert 100 ng RNA to cDNA following the manufacture’s protocol. Double stranded cDNA was SPIA® amplified using the same kit followed by purification (instead of using the washing buffer, the cDNA was washed twice in freshly prepared 80% ethanol) (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). cDNA (3.75 µg) was used for fragmentation and labeling (FL-Ovation cDNA Biotin Module V2, NugenTech, San Carlos, CA). Labeled cDNA was mixed with control oligonucleotides B2, 20× eukaryotic hybridization controls (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), herring sperm DNA, acetylated BSA, 2× hybridization buffer, and DMSO according to the Affymetrix protocol. This was used for analysis with the Affymetrix mouse GeneChip 430_2 microarray chip. The labeled cDNA was allowed to hybridize for 18 to 24 hours at 45°C before processing according to Affymetrix protocols. GeneChips were scanned on an Affymetrix 3000 Scanner. The microarray data are available at the Entrez Gene Expression Omnibus, National Center for Biotechnology (Edgar et al. 2002), and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE24625 (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Data analysis

The data files (.CEL) were analyzed with ChipInspector V2.0 software (Genomatix Software Inc., Munich, Germany); using this program gene expression in wild-type glands at ZT6 (n=3 groups) was compared to that in wild-type glands at ZT20 (n=3 groups). Crx−/− ZT6 (n=3 groups) and Crx−/− ZT20 (n=3 groups) were compared in a similar manner. In addition, a comparison of wild-type (n=6 groups) and Crx−/− (n=6 groups) gene expression was done independently of sampling time. In all analyses, the following filters were chosen: exhaustive matching, a False Discovery Rate (FDR)=0, cut off= 1, region size = 300 bp and a minimum of 4 and 5 significant probes (depending on the number of genes). Differences of p< 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Bioinformatics

Networks and canonical pathways were identified using Ingenuity Systems (IPA; Redwood, CA). Analysis of consensus sequences and transcriptional function were performed with Genomatix Pathway System (GePS), Genomatix Gene2Promoter and Genomatix RegionMiner.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis

RNA was purified using an RNeasy micro kit (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized from 350 ng of DNase-treated RNA using random primers and SuperScript III (Invitrogen, Taastrup, Denmark). Quantification of each gene was performed by use of a gene-specific internal standard curve of known copy number. For quantification, standard curves were produced by serial dilution (101 – 107 copies/ µl) of each PCR target; target sequences had been cloned into a plasmid (for details see molecular cloning). Standard curves were prepared for each qRT-PCR analysis.

qRT-PCR (LightCycler 1.5;Roche, Hvidovre, Denmark) reactions were carried out in a 20 µl volume with 1 µM primers (for sequences see Table 1), 1× SYBR green master mix (SABiosciences, Copenhagen, Denmark) and a 2 µl sample of a 3.5-fold dilution of cDNA. The program included an initial step of 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 63°C for 30 sec, extension at 72°C for 30 sec. Product specificity was confirmed initially on an agarose gel, thereafter by melting curve analysis after every qRT-PCR run.

Housekeeping gene selection for normalization was performed using 2 µl of 3.5-fold diluted samples of cDNA from wild-type and Crx−/− pineal glands. Seven genes (Gapdh, Ap1g1, β-actin, B2m, Snap25, Rps27a and Ube2d2) were analyzed to select those which exhibited the smallest time-dependent difference in expression. Crossing points were used for analysis by GeNorm (Vandesompele et al. 2002). The genes selected were Gapdh, Snap25, Ap1g1 and Ube2d2.

Data analysis

Two-way ANOVA was used to test for the influence of Crx on the genotype using Graph Pad Prism V4 (GraphPad software, USA). The four conditions were (129sv ZT6, 129sv ZT20, Crx−/− ZT6 and Crx−/− ZT20) compared with respect for genotype.

For each genotype, Student’s two-tailed ‘t’ test with Welch’s correction was used on log(2) transformed data to determine if genes were differentially expressed at a day/night basis. For each time point, the data are presented as the mean and standard error of mean (SEM) of 3 samples. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant difference (GraphPad Prism V4).

Molecular cloning of standards used for qRT-PCR and of overlapping fragments of Hoxc4

Target sequences for molecular cloning were generated by standard PCR reactions using pineal cDNA prepared from DNAase-treated RNA (primer sequences are listed in Table 1). PCR products were isolated by gel electrophoresis and gel extraction (Qiagen, Sollentuna, Sweden) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy vectors (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmids were selected and amplified in DH5-α cells (Invitrogen, Hvidovre, Denmark). In all cases, insert identity was confirmed first by EcoRI digestion and agarose gel analysis followed by sequencing (DNA Technology, Århus, Denmark). The qRT-PCR products ranged in size from 101 bp to 159 bp.

Transmission electron microscopy

The pineal glands from both Crx−/− mice and wild-type mice were fixed by immersion in cold 4% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 60 minutes. The sections were then dehydrated in a series of ethanol (30%, 50%, 70%, and 96%), block-stained in 1% uranyl acetate in absolute ethanol for 1 hour, rinsed twice in absolute ethanol, and embedded by propylene oxide in Epon®. Two-micrometer-thick survey sections were cut and counterstained with toluidine blue. Ultrathin sections, with a gray interference color, were cut from preselected areas and poststained in uranyl acetate and lead citrate. They were then viewed in a Philips EM 208 transmission electron microscope operated at 80 kV.

Radiochemical in situ hybridization histological detection of Hoxc4 transcripts

Cryostat sections (12 µm) were mounted on Superfrost Plus slides and hybridized as previously described (Møller et al. 1997;Rath et al. 2007) with a mixture of three 35S-labelled 38-mer antisense DNA probes directed against mouse Hoxc4 mRNA (NM_013553.2): 5’–CATAAAGCCCTCCTACTAGCTAGCGACCCTGTAAAGTT-3’ (278-241), 5’-CGAATTGCCAGGCCCCTGGAGACTGGTGCAGCTATACT-3’ (562-525), 5’-TTCACCCAAACCAGACCATCACACCTTGCAATATATAA-3’ (1519-1482). Sections from five wild-type and five Crx−/− mice were prepared. The hybridized sections were exposed to X-ray film for three weeks and developed.

RESULTS

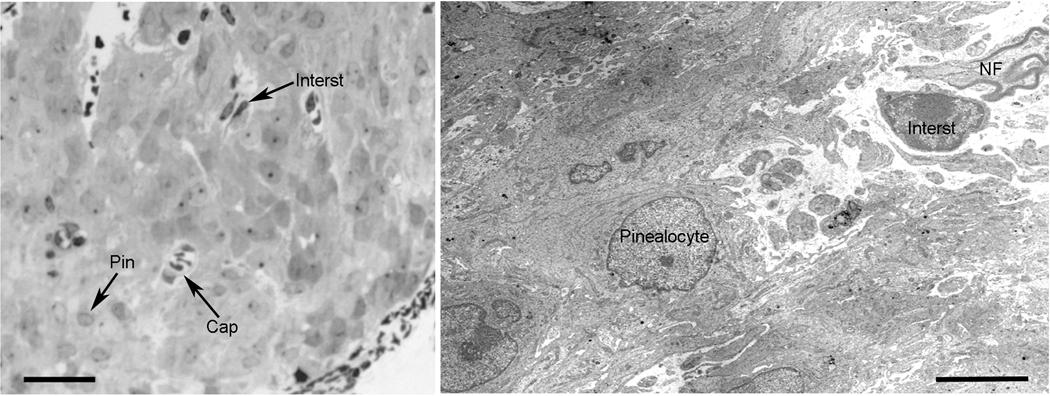

Morphology of the pineal gland

Examination of the Crx−/− pineal (Fig. 1) revealed that the morphology is not different from the wild-type gland. Rather, the gland exhibits normal features, evident from light and electron microscopic examination, characterized by a perivascular space with myelinated nerve fibers and interstitial cells surrounded by a parenchyma of pinealocytes; the shape, density and organelle content of pinealocytes in the Crx−/− and wild–type pineal gland (Upson et al., 1976; Møller et al., 1978) are indistinguishable.

Fig. 1. Transmission electron microscopic analysis of the pineal gland of the Crx−/− mouse.

(left) A Epon-embedded section (2 µ) of a Crx−/− mouse pineal tissue stained with Toluidine blue. The gland exhibits a normal morphology with pinealocytes (Pin), interstitial cells (Interst) and capillaries (Cap). Bar = 25 µm. (right) Electron micrograph of the pineal gland of the Crx−/− mouse. A perivascular space with a myelinated nerve fiber (NF) and interstitial cell (Interst) is seen surrounded by pinealocytes with normal shape, density and organelle content. Bar = 5 µm.

Crx has broad modulatory effects on gene expression in the pineal gland

Comparison of gene expression in the wild-type and Crx−/− pineal gland indicated that 512 genes were significantly (p < 0.05) downregulated in Crx−/− pineal gland: 23 >8-fold, 65 4-to 8- fold (Table 2) and 424 2- to 4-fold (supplemental Table S1). In addition, 714 genes were significantly (p<0.05) upregulated in the Crx−/− pineal gland: 10 > 8-fold, 33 4-to 8-fold (Table 2), and 671 2-to 4- fold (supplemental Table S2).

Table 2. Genes dysregulated in the pineal gland of the Crx−/− mouse.

The pineal transcriptomes of the wild-type and Crx−/− were compared independent of time of sampling. A set of 512 genes were found to be directly or indirectly downregulated by Crx deletion (p < 0.05); among these, 424 genes are downregulated only 2- to 4-fold; these genes are listed in supplemental data Table S1. A set of 714 genes were found to be directly or indirectly upregulated by Crx deletion (p<0.05); among these, 671 genes are upregulated only 2- to 4- fold; these genes are listed in supplemental Table S2. All genes are assigned by ChipInspector V2 (Genomatix). A "+" symbol in the Crx, Otx2 and/or Hoxc4 columns indicate the gene has at least one CRX, OTX2, or HOXC4 consensus sequence in the promoter region (500bp upstream of first TSS). Genes encoding transcription factors are indentified by a "+" symbol in the column labeled TF. The 1/x convention is used to indicate downregulation by a factor of x. For further details see the Materials and methods section. N/A, information is not available.

| Gene Symbol | Fold | Crx | Otx2 | Hoxc4 | TF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G3bp1 | 26.4 | ||||

| Hoxc4 | 17.5 | + | |||

| Smtnl2 | 15.6 | + | |||

| Tia1 | 15.5 | + | + | + | |

| D430019H16Rik | 13.5 | ||||

| Chodl | 12.0 | + | |||

| A330092A19Rik | 10.3 | N/A | |||

| Glra1 | 9.0 | ||||

| Mpp3 | 9.0 | + | + | ||

| Kcnip4 | 8.2 | + | + | ||

| Nefl | 6.5 | ||||

| C230022P04Rik | 6.5 | N/A | |||

| Ipcef1 | 5.9 | ||||

| Trank1 | 5.8 | + | + | ||

| Isl1 | 5.7 | + | + | ||

| Kctd4 | 5.6 | + | + | ||

| Lgi2 | 5.5 | + | |||

| Neurod2 | 5.5 | + | + | ||

| Ngef | 5.5 | ||||

| Gria2 | 5.4 | + | |||

| Caln1 | 5.1 | + | + | ||

| Tmem178 | 5.0 | + | + | ||

| Synpr | 5.0 | + | + | ||

| A2bp1 | 4.9 | + | |||

| Grin2c | 4.9 | ||||

| Prox1 | 4.9 | + | + | ||

| St18 | 4.8 | + | |||

| AI593442 | 4.8 | ||||

| Crtam | 4.7 | + | |||

| Cntn3 | 4.5 | + | + | + | |

| Epha8 | 4.5 | ||||

| Dusp26 | 4.4 | ||||

| Hist1h3i | 4.4 | ||||

| Pou3f1 | 4.4 | + | |||

| LOC100045707 | 4.4 | ||||

| Atp13a5 | 4.4 | + | |||

| Kcnq2 | 4.4 | + | |||

| Cox6a2 | 4.3 | ||||

| Slc6a1 | 4.3 | ||||

| 2900092D14Rik | 4.3 | ||||

| Lrtm1 | 4.2 | + | + | ||

| Nova1 | 4.1 | + | + | ||

| Nefm | 4.1 | ||||

| Cbln1 | 1/19.4 | ||||

| 1700042O10Rik | 1/19.3 | + | |||

| 4833423E24Rik | 1/17.4 | + | |||

| Gm626 | 1/ 16.0 | + | + | + | |

| Gm2595 | 1/ 16.0 | N/A | |||

| Ptpn20 | 1/15.7 | + | |||

| Tal2 | 1/12.2 | + | |||

| Mycn | 1/12.1 | + | |||

| Tubb3 | 1/ 12.0 | ||||

| Hk2 | 1/ 11.5 | + | |||

| Ankrd33 | 1/11.2 | ||||

| Trim15 | 1/10.5 | ||||

| Camkv | 1/10.3 | + | |||

| Ng23* | 1/9.9 | ||||

| Rasgrf1 | 1/9.2 | + | |||

| Myog | 1/8.9 | + | + | ||

| Cyp2j13 | 1/8.8 | + | |||

| Odz2 | 1/8.8 | ||||

| Panx2 | 1/8.6 | ||||

| Rho | 1/8.6 | + | |||

| 17H6S56E-3 | 1/8.5 | ||||

| Accn3 | 1/8.2 | + | + | + | |

| Rpp25 | 1/8.1 | ||||

| Gabrd | 1/7.9 | ||||

| Mst1r | 1/7.9 | + | |||

| Arhgef15 | 1/7.7 | + | + | ||

| 4930583H14Rik | 1/7.6 | + | |||

| Gpnmb | 1/7.4 | ||||

| Syngr3 | 1/7.4 | ||||

| Papss2 | 1/7.1 | + | + | ||

| 3930402G23Rik | 1/7.1 | ||||

| Piwil4 | 1/6.8 | + | + | ||

| Slc24a1 | 1/6.7 | ||||

| Rpia | 1/6.5 | ||||

| Ube2t | 1/6.3 | + | + | ||

| LOC100047829 | 1/6.3 | ||||

| Fhod3 | 1/6.1 | + | + | ||

| Nefh | 1/6.1 | ||||

| Gm2694 | 1/6.1 | N/A | |||

| LOC100045304 | 1/6.1 | ||||

| FLJ22297 | 1/6.1 | N/A | |||

| FLJ22717 | 1/6.1 | N/A | |||

| Rbpms | 1/5.9 | + | |||

| Garnl3 | 1/5.8 | + | + | + | |

| Mypn | 1/5.8 | + | + | ||

| Npl | 1/5.7 | + | + | ||

| Stc2 | 1/5.7 | ||||

| Wdr66 | 1/5.6 | ||||

| Recql | 1/ 5.5 | + | |||

| Ret | 1/ 5.4 | ||||

| Adcy3 | 1/ 5.3 | ||||

| Sall4 | 1/ 5.3 | ||||

| 2310011E23Rik | 1/ 5.3 | ||||

| Als2 | 1/ 5.2 | + | + | + | |

| Mpp4 | 1/ 5.2 | ||||

| Mesp1 | 1/ 5.1 | + | + | ||

| Cpm | 1/ 5.0 | + | + | + | |

| Golt1b | 1/ 5.0 | ||||

| Pvr | 1/ 5.0 | + | + | ||

| C1ql3 | 1/ 4.9 | ||||

| Gfra1 | 1/ 4.9 | ||||

| 2010107G12Rik | 1/ 4.7 | + | + | ||

| Cenpo | 1/ 4.6 | + | + | ||

| Gabrr1 | 1/ 4.6 | + | |||

| Lhfpl5 | 1/ 4.6 | ||||

| Rnf207 | 1/ 4.6 | ||||

| LOC639211 | 1/ 4.6 | ||||

| Accn1 | 1/ 4.5 | + | |||

| Bub1b | 1/ 4.5 | + | + | ||

| Galntl2 | 1/ 4.5 | + | |||

| Sez6l | 1/ 4.5 | + | |||

| Gng4 | 1/ 4.4 | ||||

| Sel1l3 | 1/ 4.4 | ||||

| Spsb4 | 1/ 4.3 | + | + | ||

| A930007K23Rik | 1/ 4.3 | N/A | |||

| D4Bwg0951e | 1/ 4.3 | + | + | ||

| Acoxl | 1/ 4.2 | + | + | + | |

| Gngt1 | 1/ 4.2 | + | + | ||

| Lrit1 | 1/ 4.2 | + | |||

| Akap6 | 1/ 4.1 | + | |||

| Bace2 | 1/ 4.1 | + | + | ||

| Bdkrb2 | 1/ 4.1 | ||||

| Dntt | 1/4.1 | ||||

| Kif22 | 1/ 4.1 | + | |||

| Mc1r | 1/ 4.1 | ||||

| Pde6g | 1/ 4.1 | + | |||

| Rgs20 | 1/ 4.1 | + | + | ||

| LOC100044395 | 1/ 4.1 |

Gene name assigned by authors based on homology.

Among the genes downregulated in the Crx−/− mouse pineal gland, the most affected gene other than Crx was Cbln1, which decreased by nearly 20-fold; Cbln1 encodes a protein that releases norepinephrine via adenylate cyclase/PKA-dependent signaling pathway (Albertin et al. 2000).

The most highly upregulated transcript in the Crx−/− pineal gland was identified as AK140080, which maps to a location adjacent to the ras-GTPase-activating protein SH3 domain binding protein (G3bp1) and is therefore assumed to be the 3’-extension of this gene. The second most upregulated gene was Hoxc4 (~18-fold). Hoxc4 encodes a homeodomain transcription factor required for development of the oesophagus and spinal cord (Geada et al. 1992).

Analysis of networks by IPA (Ingenuity Systems) revealed Crx influences genes involved in cellular assembly and organization, signaling and cell morphology (Table 3), among others. The indication that Crx affects genes involved in morphology is interesting because, as indicated above, the morphology and cell composition of the Crx−/− pineal gland appears normal (Fig. 1). Along with the ephrin receptor pathway, the GABA pathway was also observed to be affected by deletion of Crx.

Table 3. Networks of genes and canonical pathways influenced by the deletion of Crx.

Network and canonical pathway analysis was done using Ingenuity IPA software on the 50 most up- and 50 most downregulated genes.

| Networks | Canonical pathways |

|---|---|

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis signaling |

| Cellular assembly & organization | GABA Receptor Signaling |

| Cellular function & maintenance | Ephrin Receptor Signaling |

| Neurological disease | Neuropathic pain signaling in dorsal horn neurons |

| Genetic disorder | |

| Nutritional disease | |

| Lipid metabolism | |

| Molecular transport | |

| Small molecule biochemistry | |

| Nervous system development & function | |

| Cellular compromise | |

| Organismal injury & abnormalities | |

P-value <0.05.

An in silico analysis with Genomatix software revealed that among the 1288 genes that were dysregulated more than 2-fold in the Crx−/− mouse, 433 (represented by 772 transcripts) have predicted binding affinity for Crx (core consensus, TAATC) in the 500 bp promoter region upstream of the first transcriptional start site (TSS). Analysis of the genes regulated > 4-fold with a Crx consensus sequence, revealed that 9 had a transcriptional regulatory function (Table 2). This suggests that some effects seen in the Crx−/− pineal gland might be mediated by changes in one or more of these transcription factors.

Crx and Otx2 consensus sequences are similar and belong to the photoreceptor conserved element (PCE) family (Kikuchi et al. 1993). It was found that 194 of the dysregulated genes (representing 294 transcripts) had an Otx2 regulatory sequence (core consensus TAATCC/T) but only 54 genes could theoretically be regulated by both Crx and Otx2, thereby providing in silico evidence that expression of these genes might reflect the direct action of these transcription factors (Table 2). Aanat was one of these genes, having consensus sequences for both Crx and Otx2, are previously reported (Li et al. 1998). It was also found that that in some cases one transcript of a gene has a Crx and/or Otx2 regulatory sequence where another does not; this is seen with Tia1 and Mpp3, and may reflect use of alternative start sites.

The finding of a large upregulation of the transcription factor Hoxc4 encouraged us to investigate in silico if some of the most dysregulated genes in the Crx−/− mouse had regulatory sequences for Hoxc4 (core consensus TAATTA). Three hundred and fifteen transcripts, encoded by 205 different genes, were found to have an Hoxc4 consensus sequence. None of the transcripts that were upregulated >4-fold had a transcriptional role, thereby providing no reason to suspect that effects of Hoxc4 were mediated by any of these transcription factors. The Hoxc4 co-cited network generated by Genomatix Pathway System (GePS)(Figure 2) has only a single gene that is dysregulated in the Crx−/− pineal gland, Hoxc5 (2-fold). The absence of any other dysregulated gene in this co-cited network suggests that the genes influenced by Hoxc4 in the pineal gland differ from those regulated by Hoxc4 in other tissues.

Fig. 2. Genes co-cited with Hoxc4.

The dashed line indicates co-citation of the connected genes in the literature; a diamond indicates the promoter of gene B (the gene with the diamond) has a consensus sequence for the transcription factor encoded by gene A. An additional filled diamond at the other end of the line means that the promoter of gene A has a consensus sequence for the transcription factor encoded by gene B. The only gene from this network that exhibited a change in expression in the Crx−/− mouse other than Hoxc4 is Hoxc5 (2-fold). (Figure generated by the Genomatix Pathway System).

Crx influences differential day/night expression of genes in the mouse pineal gland

In the wild-type pineal gland, 51 transcripts were differentially expressed on a night/day basis (>2-fold, p<0.05, Table 4); amongst these the abundance of 34 (67%) decreased at night and that of 17 (33%) increased at night (Table 4). The abundance of ten transcripts changed more than 8-fold and that of 35 transcripts changed 4-to 8-fold (Table 4); the transcript with the largest nocturnal increase was Aanat. The transcript exhibiting the largest nocturnal decrease (1/9.2) was encoded by Nrxn3, which is thought to be involved in synaptic plasticity (Kelai et al. 2008).

Table 4. Transcripts differentially expressed (p < 0.05) on a day/night basis in the wild-type and/or Crx−/−pineal gland. A. Genes upregulated at night; B. Genes downregulated at night.

Ratios are given as transcript levels at ZT20/ ZT6. The columns labeled Crx, Otx2 and Hoxc4 indicate the presence of regulatory binding sequences for the indicated transcription factor in the promoter of the gene (500bp upstream of first TSS).

| A. Genes upregulated at night | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | Wild- type |

Crx−/− | Crx | Otx2 | Hoxc4 |

| Aanat | 14.6 | 8.5 | + | + | |

| Gng4 | 6.9 | 6.9 | |||

| Slc6a5 | 7.4 | 5.0 | + | ||

| E2f8 | 13.5 | − | + | ||

| Evi2a | 12.0 | − | + | ||

| Cpm | 11.2 | − | + | + | + |

| Pols | 9.5 | − | |||

| Gm2788 | 9.3 | − | |||

| LOC100046261 | 9.3 | − | |||

| 2810011L19Rik | 9.2 | − | |||

| Pvr | 8.9 | − | + | + | |

| 3930402G23Rik | 7.5 | − | |||

| Kcnc1 | 7.5 | − | + | ||

| Asphd2 | 7.4 | − | |||

| E130002L11Rik | 6.0 | − | + | ||

| Gulo | 5.7 | − | |||

| Frmpd1 | 5.6 | − | + | ||

| Pde10a | − | 4.7 | + | ||

| Lrit1 | − | 4.4 | + | ||

| Mitf | − | 4.3 | + | + | |

| Syt10* | − | 4.2 | |||

| Vil1 | − | 4.1 | |||

| Dclk1 | − | 4.0 | + | + | |

| ENSMMUT00000011414 | − | 3.7 | |||

| Ccdc109b | − | 3.7 | + | + | |

| EG245190 | − | 3.7 | |||

| Rftn1 | − | 3.7 | + | ||

| Slc6a17 | − | 3.6 | |||

| Gls2 | − | 3.5 | |||

| Rho | − | 3.4 | + | ||

| Odc1 | − | 3.4 | |||

| Adora1 | − | 3.2 | + | ||

| 1810041L15Rik | − | 3.2 | + | ||

| Clec4d | − | 3.1 | + | + | |

| Bok | − | 2.9 | + | + | |

| Nrp2* | − | 2.8 | |||

| Cry1 | − | 2.8 | + | + | |

| 6430411K18Rik | − | 2.6 | + | ||

| Clstn3 | − | 2.5 | |||

| Stard4 | − | 2.3 | |||

| B. Genes downregulated at night | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | Wild- type |

Crx−/− | Crx | Otx2 | Hoxc4 |

| Atg16l1 | 1/4.0 | 1/2.6 | + | + | |

| Cacnb2 | 1/7.4 | 1/2.9 | + | + | |

| Hspa12a | 1/4.8 | 1/3.3 | |||

| Nr1d1 | 1/4.4 | 1/5.9 | + | ||

| Pdc | 1/5.9 | 1/3.7 | + | ||

| Nrxn3 | 1/9.2 | − | + | ||

| AK048867 | 1/6.6 | − | + | ||

| Cntn4 | 1/6.0 | − | + | + | + |

| Xpo7 | 1/5.9 | − | |||

| Gabrd | 1/5.7 | − | |||

| BC027072 | 1/5.5 | − | + | ||

| Clca3 | 1/5.4 | − | + | ||

| A330008L17Rik | 1/5.4 | − | |||

| A730054J21Rik | 1/5.4 | − | + | ||

| Ppp2r2b | 1/5.3 | − | + | + | + |

| ENSPTRT00000066164 | 1/5.3 | − | |||

| Car8 | 1/4.9 | − | |||

| Ppfia2 | 1/4.9 | − | + | + | + |

| LOC676792 | 1/4.9 | − | |||

| Ubr1* | 1/4.8 | − | |||

| EG665934 | 1/4.8 | − | |||

| Bai3 | 1/4.6 | − | + | + | |

| Gabra1 | 1/4.5 | − | + | + | |

| Fat3 | 1/4.4 | − | + | ||

| Slc8a1 | 1/4.4 | − | + | + | + |

| Csmd3 | 1/4.3 | − | + | + | + |

| 4930414L22Rik | 1/4.3 | − | |||

| Fmn1 | 1/4.2 | − | + | + | |

| Mina | 1/3.9 | − | + | + | + |

| Sphkap | 1/3.9 | − | |||

| Sv2b | 1/3.9 | − | + | + | |

| 4930526L06Rik | 1/3.9 | − | |||

| Ddc | 1/3.8 | − | + | + | |

| Tmem90a | 1/3.7 | − | |||

| Cdh8 | − | 1/4.0 | + | ||

| Gngt1 | − | 1/4.0 | + | + | |

| Rprm | − | 1/3.8 | |||

| Chrna6 | − | 1/3.7 | + | ||

| Adcy1 | − | 1/3.3 | |||

| Sgip1 | − | 1/3.1 | + | + | |

| ENST00000371039 | − | 1/3.1 | |||

| Sphk2 | − | 1/3.0 | |||

| Dbp | − | 1/2.9 | + | ||

| A830039N20Rik | − | 1/2.6 | + | ||

| C030014L02 | − | 1/2.6 | |||

| B3galt2 | − | 1/2.5 | + | ||

| Cngb3 | − | 1/2.4 | + | + | |

| Gjd2 | − | 1/2.4 | + | ||

| Mypn | − | 1/2.4 | + | + | |

| Srpk3 | − | 1/2.3 | + | ||

| Morn1 | − | 1/2.0 | |||

Gene name assigned by authors based on homology.

Transcript is not differentially expressed at a day/night basis. For further details see the Materials and methods section.

In the Crx−/− mouse, 49 transcripts displayed differential night/day expression (Table 4), of which 7 are not annotated. Among these 49 differentially expressed transcripts, 22 (45%) decreased at night and 27 (55%) increased at night (Table 4). The transcripts that were day/night expressed in the Crx−/− pineal gland differed from those in the wild-type mouse; only 8 genes had a different day/night expression in both groups (Table 4).

Of special note was the observation that Aanat increased in the Crx−/− mouse pineal at night compared to day time (~8.5-fold; Table 4). The transcript that exhibited the largest decrease at night was Nr1d1/Rev-erbα, which functions as a transcriptional repressor and plays a role in circadian systems (Burris, 2008; Meng et al. 2008).

Genes that were differentially expressed on a day/night basis in the wild-type mouse were associated with networks dedicated with behavior, development and function as defined by IPA; the primary canonical pathways include dopamine receptor signaling, GABA receptor signaling and β-adrenergic signaling (Table 5), the last two of which are involved in melatonin synthesis (Klein et al. 1971; Sun et al. 2002).

Table 5. Assignment of genes differentially expressed on a day/night basis in the wild-type and Crx−/− mouse to networks and canonical pathways.

Network and canonical pathway analysis was done using Ingenuity IPA software.

| Networks | Canonical pathways | |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Behavior | Cardiac b-adrenergic Signaling |

| Nervous system development & function | GABA Receptor signaling | |

| Gastrointestinal disease | Dopamine Receptor Signaling | |

| Neurological disease | ||

| Psychological disorders | ||

| Cell morphology | ||

| Cellular development | ||

| Tumor morphology | ||

| Lipid Metabolism | ||

| Small molecule biochemistry | ||

| Cell death | ||

| Organ morphology | ||

| Crx−/− | Behavior | Phototransduction Pathway |

| Nervous system development & function | Protein Kinase A Signaling | |

| Genetic disorder | cAMP-mediated Signaling | |

| Cell-to-cell signaling & Interaction | Circadian Rhythm Signaling | |

| Cardiovascular disease | Cardiac b-adrenergic Signaling | |

| Neurological disease | ||

| Skeletal & Muscular disorders | ||

| Cellular development | ||

| Cellular growth & proliferation | ||

| Embryonic development | ||

| Organismal development | ||

| Skeletal & muscular system development & function | ||

P-value <0.05.

The genes that are differently expressed on a day/night basis in the Crx−/− mouse were found to be involved in networks committed to behavior, development and function; the same networks as observed in the wild-type mouse (Table 5). Different canonical pathways were observed to be altered in the Crx−/− mouse versus the wild-type animal: the phototransduction pathway, protein kinase A signaling, cAMP-mediated signaling and circadian rhythm signaling exhibit daily change in the Crx−/− mouse (Table 5). These pathways are all involved in the production of melatonin or the control of this process. The β-adrenergic signaling pathway was the only canonical pathway to exhibit differential night/day expression in the pineal glands of both the wild-type and Crx−/− mice (Table 5).

Using Genomatix software it was found that 24 of the 49 genes exhibiting differential day/night expression in the Crx−/− mouse had a Crx consensus sequence (Table 4), only five genes had binding affinity for both Crx and Otx2. Six of the upregulated genes had a Hoxc4 consensus sequence, indicating that these are candidates for upregulation by Hoxc4. Moreover, it is possible that the transcription factor Cry1, might mediate effects of Hoxc4 by virtue of a Hoxc4 consensus sequence in the Cry1 promoter. In addition, it was investigated that the Aanat 500 bp upstream promoter did not had a Cry1 consensus sequence indicating that Cry1 is not responsible for the upregulation of Aanat at night in the Crx−/− mouse in the absence of Crx.

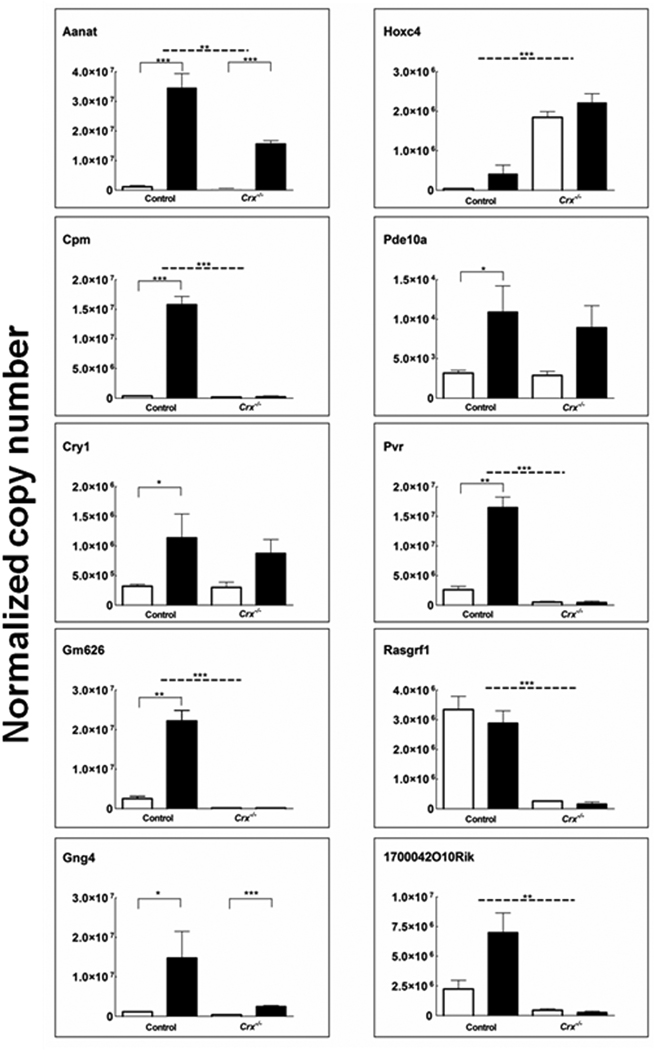

qRT-PCR validation of microarray data

Six genes that exhibited differential night/day expression by microarray in either wild-type or Crx−/− pineal glands (Aanat, Gng4, Cpm, Pvr, Pde10a, Cry1) were tested with qRT-PCR; a daily rhythm was detected in all encoded transcripts in glands from wild-type animals (Fig. 3) and in 5 genes from Crx−/− animals. In addition, the differential wild-type /Crx−/− expression patterns seen in four transcripts (Hoxc4, 1700042O10Rik, Gm626 and Rasgrf1) were confirmed by qRT-PCR.

Fig. 3. qRT-PCR analysis of transcripts detected as either day/night expressed or differentially expressed in Crx−/− mice as compared with wild-types.

Black bars, night samples; white bars, day samples. Transcripts are identified by gene symbols. Values were normalized to Gapdh, Ube2d2, Snap25 and Ap1g1. Each value represents the mean +/− S.E.M of three independent analyses. * p-values < 0.05; ** p-values < 0.01; and, *** p-values < 0.001. For further details see the Materials and methods section.

In the case of Pde10a, a set of primers directed against the 3’ region of the transcript confirmed the results of microarray which interrogated this region (Fig. 3). However, a set of primers directed against the 5’ region did not confirm the results of microarray; rather qRT-PCR with these primers revealed a 1/3.5 -fold ZT6/ZT20 inverse rhythm (6.2 × 103 / 1.8 × 103 transcripts) in the wild-type (p-value=0.02) and 1/1.4 –fold ZT6/ZT20 inverse rhythm (3.8 × 103 / 2.7 × 103) in the Crx−/− mouse (p-value=0.1), indicating at least two Pde10a transcripts are expressed in the pineal gland and that they are differentially regulated.

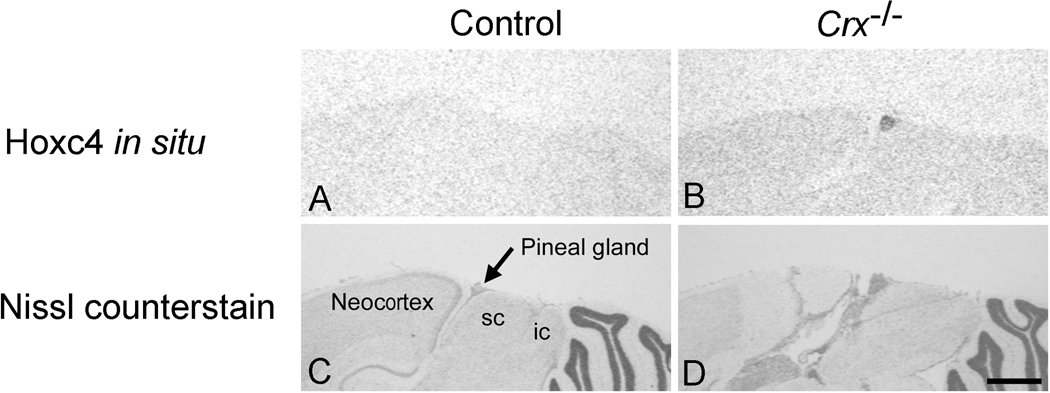

Studies on Hoxc4

The marked effects of Crx deletion on Hoxc4 was studied in greater detail because homeobox genes are known to broadly control cascades of gene expression. Three overlapping portions of the Hoxc4 transcript were cloned from Crx−/− pineal mRNA; sequencing confirmed their identity (ORF >99% identical to NM_013553.2), thereby indicating that a full-length Hoxc4 transcript is likely to be present in the Crx−/− pineal gland.

Hoxc4 expression in the Crx−/− mouse pineal gland was also confirmed using radiochemical in situ hybridization histology (Fig. 4), which failed to detect expression of the gene in surrounding tissues or in the wild-type gland.

Fig. 4. Radiochemical In situ hybridization histochemical (ISH) detection of Hoxc4 mRNA.

Panels A and C are sagittal brain sections from a wild-type mouse and panels B and D are sagittal brain sections from a Crx−/− mouse. The upper panels are results from ISH and the lower panels are results of Nissl counter staining of the sections used for ISH analysis. A positive ISH signal is only seen in the superficial pineal gland of the Crx−/− mouse (Fig B) and not in that of the wild-type (Fig A), in agreement with the results of microarray and qRT-PCR studies. A signal was not generated with a sense probe. Scale bar = 1 mm. For further details see the Materials and methods section. sc, superior colliculus; ic, inferior colliculus.

DISCUSSION

This study was primarily designed to extend previous studies on the pineal gland of the Crx−/− mouse; these results, including the broad modulatory effects of Crx on the pineal transcriptome, will be addressed below. In addition, since this is the first report of microarray analysis of the adult mouse pineal gland, the results of this study provide new understanding of gene expression in this tissue; this topic will also be discussed. It should be noted that microarray has been used to study the neonatal mouse pineal gland (Munoz et al. 2007). There are large differences in the genes expressed in the neonatal and adult pineal gland, consistent with evidence that marked developmental changes occur at about this time in the rodent, including a marked decrease in cell division and an increase in expression of genes linked to melatonin synthesis and visual signal transduction (Quay W.B. 1979; Klein et al. 1981). However, a thorough discussion of the developmental differences in gene expression in the pineal gland as revealed by both microarray studies is beyond the scope of this report.

Night/day differences in transcript abundance in the pineal gland are less prevalent in the mouse as compared to the rat

The pineal transcriptome has previously been studied by microarray in the rat (Tosini et al. 2008;Bailey et al. 2009), chicken (Bailey et al. 2003) and zebrafish (Toyama et al. 2009) but not in the mouse. Here we have found that 51 genes in the wild-type mouse pineal gland exhibit a daily rhythm (>2-fold). These 51 genes were found to be elements of canonical pathways that impact melatonin synthesis (Table 5). In a similar study of the rat pineal, Bailey et al., (2009) found >600 genes were different day/night expressed >2-fold. The rat versus mouse difference in the number genes differentially expressed on a night/day basis is striking. Further, the amplitude of changes appears to be greater in the rat, in which 130 genes exhibited a >4-fold night/day difference. In the wild-type mouse there are only 35 genes with a night/day difference of this magnitude; in addition, only Aanat and Pvr show a difference in both rat and mouse.

Differences in day/night gene expression between the rat and mouse may reflect fundamental biological differences between these species as are known to exist between other mammals. For example, the large night/day difference in Aanat transcript number seen in the rat is not seen in the Rhesus monkey or sheep, which exhibit little or no night/day difference in AANAT mRNA whereas changes in AANAT activity do occur (Coon et al. 1999; Johnston et al. 2004; Klein 2007; Coon et al. 2002), presumably as a function of posttranslational mechanisms (Klein 2007).

Inbreeding might also be responsible for the small number of genes expressed differentially on day/night basis in the mouse pineal gland. This is consistent with the observation that the genes encoding the melatonin synthesis enzymes Aanat and Asmt/Hiomt are nonfunctional in most laboratory mice because of mutations (Ebihara et al. 1987; Roseboom et al. 1998). Accordingly, a global difference in the daily pattern of gene expression might be caused by a mutation in a gene with a broad impact on gene expression, e.g. a transcription-related factor.

These findings provide further reason to question whether conclusions drawn from analysis of gene expression patterns in tissues of one species are necessarily applicable to other species.

The broad pleiotropic effect of Crx on the pineal transcriptome

The current study identified more than a thousand genes that are dysregulated in the Crx−/− mouse, more than half of which were upregulated. It is surprising that differential expression of such a high number of genes is not reflected in a major morphological change in the pineal gland (Fig. 1) as for example seen in retina of this mouse. It is of interest that several of the dysregulated transcripts in the Crx−/− mouse are part of the ephrin pathway, which controls cell morphology and cell communication; in view of this, it is surprising that morphological changes are not apparent.

An in silico analysis of Hoxc4 consensus sequences revealed that some of the most upregulated genes (Table 2) had at least one Hoxc4 consensus sequence; the upregulation of these genes might therefore be explained by a direct reflection of the upregulation of Hoxc4. It was observed that of the upregulated genes having a Hoxc4 consensus sequence, none had a transcriptional regulatory function and therefore were not responsible for upregulation of other genes. The finding of “genetic disorder” pathway as one of the networks most affected reflects Crx’s proven involvement in several retinal diseases (Furukawa et al. 1997; Furukawa et al. 1999).

In contrast to the absence of marked morphological changes in the pineal gland, the retina of Crx−/− mice is grossly affected as evident from the loss of photoreceptor outer segments (Furukawa et al. 1999; Rovsing et al. 2010). A large number of genes are also dysregulated in the retina of the Crx−/− mouse with major morphological changes to follow (Hsiau et al. 2007; Furukawa et al. 1999; Rovsing et al. 2010). Some of the genes which are downregulated in the Crx−/− pineal gland are also downregulated in the Crx−/− retina including rhodopsin (Rho) and cone opsin (Opn1sw) (Hsiau et al. 2007;Furukawa et al. 1999). A comparison of the most affected genes in both tissues (data from Hsiau et al., 2007) indicates that only a few are affected in both tissues. For example, Cbln1 is downregulated ~19-fold in the pineal gland but is not affected in retina, indicating that this gene is regulated by different mechanisms in these tissues. This is consistent with the explanation that Crx acts in concert with other transcription factors to control transcription (Nishida et al. 2003); apparently, the combination of factors in the retina differs from that in the pineal gland.

Here we found that the amplitude of the daily rhythm in Aanat transcripts is reduced 50% in the pineal gland of the Crx−/− mouse, in confirmation of previous observations (Furukawa et al., 1999). This indicates that a functional Crx is required for the normal pattern of expression of Aanat. It is not clear whether the absence of Crx appears to reduce Aanat expression by lowering the maximum level of expression or by shifting the timing of the peak in expression. The expression of Aanat is of special interest because it is thought that multiple Crx consensus sequences in the Aanat promoter play a conserved role in Aanat expression (Appelbaum and Gothilf 2006; Klein 2007). However, it is clear that Crx is not an absolute requirement for expression of Aanat. This does not; however eliminate the role of the PCE sites. It is possible that the role of Crx might be redundantly played by the related transcription factor Otx2 which binds to the Otx variant of the PCE site. Otx2 is essential for pineal development (Nishida et al. 2003) and has a distinct postnatal role in the mouse retina (Koike et al. 2007). Otx2 is expressed in the adult rodent pineal gland and retina in the presence and absence of Crx (Rath et al. 2006; Supplemental Table S3 and S5 in Hsiau et al. 2007). Otx2 and Crx have similar binding preferences and exhibit functional redundancy (Li et al. 1998;Bobola et al. 1999;Bernard et al. 2001;Dinet et al. 2006). Accordingly, it is reasonable to suspect that Otx2 substitutes for Crx in the pineal gland of the Crx−/− mouse in a redundant manner to control expression of Aanat and perhaps other genes. In the case of genes with consensus binding sequences for both, as is the case with Aanat, expression may only reflect the interaction of Otx2 with the Otx2 consensus binding sequence. Whereas it is also possible that upregulation of Otx1 or Otx2 might compensate for decreased Crx expression, our microarray analysis failed to detect a change in expression of either Otx1 or Otx2, thereby providing no reason to entertain such a compensatory explanation.

The reduction of the amplitude of Aanat expression in the Crx−/− mouse might also reflect reduction of expression of Cbln1, which is thought to modulate norepinephrine release (Albertin et al. 2000). Cbln1 might be normally released by pinealocytes into the extracellular space, where it could enhance norepinephrine release from sympathetic nerve endings. In addition, Adcy3, adenylate cyclase 3 is downregulated 5.3-fold in the Crx−/− mouse. The product of this gene catalyzes the formation of cAMP (Linder 2006). Cbln1 does not appear to be directly regulated by Crx because promoter analysis fails to reveal the presence of either a Crx or an Otx2 consensus sequence. Other possible scenarios include the impact of Crx elimination on visual function and control of Aanat levels and temporal organization of the transcription factor system controlling expression.

The results of this investigation also point to a role of Crx in circadian biology of the pineal gland, because there was no evidence in the Crx−/− pineal gland of a day/night pattern of expression of 43 genes seen in the wild-type animal. This may reflect temporal disorganization of the transcription factor system which controls gene expression, including Cry1 and Nr1d1/Rev-erbα. It is also possible that this is linked to the less robust nature of circadian locomotor activity seen in the Crx−/− mouse (Rovsing et al., 2010), which provides evidence for a role of Crx in circadian rhythms, separate from phenotype determination in the pineal gland and retina. Effects on circadian biology may reflect Crx-dependent changes in expression of a subset of the >1000 genes that are dysregulated in the Crx−/− mouse pineal gland, some of which are involved in signal transduction (for example Gng4, Rasgrf1 and Rho). It is also possible that Crx-dependent effects on the pineal gland contribute to the circadian amplitude of locomotor activity and temperature, both of which are reduced in the Crx−/− mouse (Rovsing et al., 2010). It can be speculated that these effects are mediated by an unidentified pineal-dependent mechanism. It is unlikely that melatonin is involved because the capacity to synthesize melatonin is markedly reduced in the 129sv strain (Roseboom et al. 1998), which, as indicated above, is true of most laboratory mice (Ebihara et al. 1987).

As discussed above for Aanat, It is not clear if changes in differential day/night gene expression represent a true shift from constant non-day/night expression to day/night expression or if genes that appear to become expressed at a day/night basis in the Crx−/− mouse are also expressed at a day/night basis in wild-type animals with different phasing; and, that changes in the circadian system combined with the limitations imposed by a two point sampling experimental design resulted in the detection of these rhythms. Future studies involving more frequent time samplings should provide a better profiling of the influence of Crx on the temporal nature of gene expression in the pineal gland.

The adult pineal gland is not known to be photosensitive. The expression of phototransduction genes in this tissue appears to reflect the common origin of photoreceptors and pinealocytes (Klein 2007). If the transcripts are translated, the encoded proteins could function indirectly in G-protein coupled receptor signaling. For example, photoreceptors could form heterodimers with the adrenergic receptors which control pineal function. Formation of receptor heterodimers is known to modify function and specificity (Prinster et al. 2005).

Hoxc4 in the pineal gland

These studies have revealed a strong upregulation of Hoxc4 in the Crx−/− mouse pineal gland (Fig. 3 and 4), which is not seen in the wild-type or Crx−/− retina by microarray (Hsiau et al. 2007) or qRT-PCR (data not shown). It seems reasonable to consider that the low levels of Hoxc4 expression in the wild-type pineal gland normally influences the transcriptome profile by influencing the expression of the genes which are upregulated in the Crx−/− pineal gland. It is of interest to find that analysis of the Hoxc4 co-citation network (Figure 2) indicates that to a large degree, the genes linked to Hoxc4 in other systems are not apparently linked to Hoxc4 in the pineal gland. This suggests that Hoxc4 networks differ markedly on a tissue-to-tissue basis.

Summarizing, it appears that Crx plays a broad role in controlling the pineal transcriptome by weakly to mildly enhancing or suppressing expression of ~1200 genes. However, the change in the transcriptome is not associated with a remarkable change in cellular composition of the gland or in dramatic loss of expression of pinealocyte marker genes. This indicates that Crx is not an absolute requirement for expression of the pinealocyte phenotype. Some of the changes observed in the absence of Crx expression could possibly be mediated in part by a marked increase in the downstream expression of the homeobox gene Hoxc4, which may normally play a less obvious role in shaping the pineal transcriptome.

Supplementary Material

This is an extension of data presented in Table 2, which lists genes downregulated > 4-fold. For further details see the legend to Table 2 and the Materials and Methods.

This is an extension of data presented in Table 2, which lists genes upregulated > 4-fold. For further details see the legend to Table 2 and the Materials and Methods.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Supported by the Lundbeck Foundation, the Danish Medical Research Council (grant number 271-07-0412), the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Carlsberg Foundation, Fonden til Lægevidenskabens Fremme, Simon Fougner Hartmanns Familiefond, the Danish Eye Health Society (Værn om Synet) and the Intramural Research Program of the The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. The authors wish to express their appreciation to Dr. Connie Cepko for the generous gift of the Crx−/− mice.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- Albertin G, Malendowicz LK, Macchi C, Markowska A, Nussdorfer GG. Cerebellin stimulates the secretory activity of the rat adrenal gland: in vitro and in vivo studies. Neuropeptides. 2000;34:7–11. doi: 10.1054/npep.1999.0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum L, Gothilf Y. Mechanism of pineal-specific gene expression: the role of E-box and photoreceptor conserved elements. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2006;252:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MJ, Beremand PD, Hammer R, Bell-Pedersen D, Thomas TL, Cassone VM. Transcriptional profiling of the chick pineal gland, a photoreceptive circadian oscillator and pacemaker. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003;17:2084–2095. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MJ, Coon SL, Carter DA, Humphries A, Kim JS, Shi Q, Gaildrat P, Morin F, Ganguly S, Hogenesch JB, Weller JL, Rath MF, Møller M, Baler R, Sugden D, Rangel ZG, Munson PJ, Klein DC. Night/day changes in pineal expression of >600 genes: central role of adrenergic/cAMP signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:7606–7622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808394200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard M, Dinet V, Voisin P. Transcriptional regulation of the chicken hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase gene by the cone-rod homeobox-containing protein. J. Neurochem. 2001;79:248–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobola N, Briata P, Ilengo C, Rosatto N, Craft C, Corte G, Ravazzolo R. OTX2 homeodomain protein binds a DNA element necessary for interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein gene expression. Mech. Dev. 1999;82:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris TP. Nuclear hormone receptors for heme: REV-ERBalpha and REV-ERBbeta are ligand-regulated components of the mammalian clock. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008;22:1509–1520. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Wang QL, Nie Z, Sun H, Lennon G, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Zack DJ. Crx, a novel Otx-like paired-homeodomain protein, binds to and transactivates photoreceptor cell-specific genes. Neuron. 1997;19:1017–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80394-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon SL, Del OE, Young WS, III, Klein DC. Melatonin synthesis enzymes in Macaca mulatta: focus on arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (EC 2.3.1.87) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87:4699–4706. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon SL, Zarazaga LA, Malpaux B, Ravault JP, Bodin L, Voisin P, Weller JL, Klein DC, Chemineau P. Genetic variability in plasma melatonin in sheep is due to pineal weight, not to variations in enzyme activities. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:E792–E797. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.5.E792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinet V, Girard-Naud N, Voisin P, Bernard M. Melatoninergic differentiation of retinal photoreceptors: activation of the chicken hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase promoter requires a homeodomain-binding element that interacts with Otx2. Exp. Eye Res. 2006;83:276–290. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara S, Hudson DJ, Marks T, Menaker M. Pineal indole metabolism in the mouse. Brain Res. 1987;416:136–140. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Morrow EM, Cepko CL. Crx, a novel otx-like homeobox gene, shows photoreceptor-specific expression and regulates photoreceptor differentiation. Cell. 1997;91:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Morrow EM, Li T, Davis FC, Cepko CL. Retinopathy and attenuated circadian entrainment in Crx-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:466–470. doi: 10.1038/70591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geada AM, Gaunt SJ, Azzawi M, Shimeld SM, Pearce J, Sharpe PT. Sequence and embryonic expression of the murine Hox-3.5 gene. Development. 1992;116:497–506. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.2.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiau TH, Diaconu C, Myers CA, Lee J, Cepko CL, Corbo JC. The cis-regulatory logic of the mammalian photoreceptor transcriptional network. PLoS. One. 2007;2:e643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang dW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JD, Bashforth R, Diack A, Andersson H, Lincoln GA, Hazlerigg DG. Rhythmic melatonin secretion does not correlate with the expression of arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase, inducible cyclic amp early repressor, period1 or cryptochrome1 mRNA in the sheep pineal. Neuroscience. 2004;124:789–795. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelai S, Maussion G, Noble F, Boni C, Ramoz N, Moalic JM, Peuchmaur M, Gorwood P, Simonneau M. Nrxn3 upregulation in the globus pallidus of mice developing cocaine addiction. Neuroreport. 2008;19:751–755. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282fda231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Raju K, Breitman ML, Shinohara T. The proximal promoter of the mouse arrestin gene directs gene expression in photoreceptor cells and contains an evolutionarily conserved retinal factor-binding site. Mol. Cell Biol. 1993;13:4400–4408. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DC. The 2004 Aschoff/Pittendrigh lecture: Theory of the origin of the pineal gland--a tale of conflict and resolution. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2004;19:264–279. doi: 10.1177/0748730404267340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DC. Arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase: "the Timezyme". J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:4233–4237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DC, Namboodiri MA, Auerbach DA. The melatonin rhythm generating system: developmental aspects. Life Sci. 1981;28:1975–1986. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90644-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DC, Reiter RJ, Weller JL. Pineal N-acetyltransferase activity in blinded and anosmic male rats. Endocrinology. 1971;89:1020–1023. doi: 10.1210/endo-89-4-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike C, Nishida A, Ueno S, Saito H, Sanuki R, Sato S, Furukawa A, Aizawa S, Matsuo I, Suzuki N, Kondo M, Furukawa T. Functional roles of Otx2 transcription factor in postnatal mouse retinal development. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:8318–8329. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01209-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Chen S, Wang Q, Zack DJ, Snyder SH, Borjigin J. A pineal regulatory element (PIRE) mediates transactivation by the pineal/retina-specific transcription factor CRX. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:1876–1881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder JU. Class III adenylyl cyclases: molecular mechanisms of catalysis and regulation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:1736–1751. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6072-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mano H, Fukada Y. A median third eye: pineal gland retraces evolution of vertebrate photoreceptive organs. Photochem. Photobiol. 2007;83:11–18. doi: 10.1562/2006-02-24-IR-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng QJ, McMaster A, Beesley S, Lu WQ, Gibbs J, Parks D, Collins J, Farrow S, Donn R, Ray D, Loudon A. Ligand modulation of REV-ERBalpha function resets the peripheral circadian clock in a phasic manner. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:3629–3635. doi: 10.1242/jcs.035048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller M, van Deurs B, Westergaard E. Vascular permeability to proteins and peptides in the mouse pineal gland. Cell Tiss. Res. 1978;195:1–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00233673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller M, Phansuwan-Pujito P, Morgan KC, Badiu C. Localization and diurnal expression of mRNA encoding the beta1-adrenoceptor in the rat pineal gland: an in situ hybridization study. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;288:279–284. doi: 10.1007/s004410050813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz EM, Bailey MJ, Rath MF, Shi Q, Morin F, Coon SL, Moller M, Klein DC. NeuroD1: developmental expression and regulated genes in the rodent pineal gland. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:887–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida A, Furukawa A, Koike C, Tano Y, Aizawa S, Matsuo I, Furukawa T. Otx2 homeobox gene controls retinal photoreceptor cell fate and pineal gland development. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:1255–1263. doi: 10.1038/nn1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S, Provencio I, Tu DC, Pires SS, Rollag MD, Castrucci AM, Pletcher MT, Sato TK, Wiltshire T, Andahazy M, Kay SA, Van Gelder RN, Hogenesch JB. Melanopsin is required for non-image-forming photic responses in blind mice. Science. 2003;301:525–527. doi: 10.1126/science.1086179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinster SC, Hague C, Hall RA. Heterodimerization of g protein-coupled receptors: specificity and functional significance. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005;57:289–298. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quay WB. Pineal Chemistry. Vol. 894. The Bannerstone division of American lectures in living chemistry; 1979. Cellular and physiological mechanisms; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Rath MF, Morin F, Shi Q, Klein DC, Møller M. Ontogenetic expression of the Otx2 and Crx homeobox genes in the retina of the rat. Exp. Eye Res. 2007;85:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath MF, Munoz E, Ganguly S, Morin F, Shi Q, Klein DC, Møller M. Expression of the Otx2 homeobox gene in the developing mammalian brain: embryonic and adult expression in the pineal gland. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:556–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roseboom PH, Namboodiri MA, Zimonjic DB, Popescu NC, Rodriguez IR, Gastel JA, Klein DC. Natural melatonin 'knockdown' in C57BL/6J mice: rare mechanism truncates serotonin N-acetyltransferase. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;63:189–197. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovsing L, Rath MF, Lund-Andersen C, Klein DC, Møller M. A neuroanatomical and physiological study of the non-image forming visual system of the cone-rod homeobox gene (Crx) knock out mouse. Brain Res. 2010;1343:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Deng J, Liu T, Borjigin J. Circadian 5-HT production regulated by adrenergic signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:4686–4691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062585499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosini G, Pozdeyev N, Sakamoto K, Iuvone PM. The circadian clock system in the mammalian retina. Bioessays. 2008;30:624–633. doi: 10.1002/bies.20777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama R, Chen X, Jhawar N, Aamar E, Epstein J, Reany N, Alon S, Gothilf Y, Klein DC, Dawid IB. Transcriptome analysis of the zebrafish pineal gland. Dev. Dyn. 2009;238:1813–1826. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upson RH, Benson B, Satterfield V. Quantitation of ultrastructural changes in the mouse pineal in response to continuous illumination. Anat Rec. 1976;184:311–323. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091840306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J, De PK, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van RN, De PA, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. RESEARCH0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This is an extension of data presented in Table 2, which lists genes downregulated > 4-fold. For further details see the legend to Table 2 and the Materials and Methods.

This is an extension of data presented in Table 2, which lists genes upregulated > 4-fold. For further details see the legend to Table 2 and the Materials and Methods.