Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) leads to a rapid and excessive glutamate elevation in the extracellular milieu, resulting in neuronal degeneration and astrocyte damage. Posttraumatic hypoxia is a clinically relevant secondary insult that increases the magnitude and duration of glutamate release following TBI. N-acetyl-aspartyl glutamate (NAAG), a prevalent neuropeptide in the CNS, suppresses presynaptic glutamate release by its action at the mGluR3 (a group II metabotropic glutamate receptor). However, extracellular NAAG is rapidly converted into NAA and glutamate by the catalytic enzyme glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) reducing presynaptic inhibition. We previously reported that the GCPII inhibitor ZJ-43 and its prodrug di-ester PGI-02776 reduce the deleterious effects of excessive extracellular glutamate when injected systemically within the first 30 minutes following injury. We now report that PGI-02776 (10 mg/kg) is neuroprotective when administered 30-minutes post-injury in a model of TBI plus 30 minutes of hypoxia (FiO2 = 11%). 24-hrs following TBI with hypoxia, significant increases in neuronal cell death in the CA1, CA2/3, CA3c, hilus and dentate gyrus were observed in the ipsilateral hippocampus. Additionally, there was a significant reduction in the number of astrocytes in the ipsilateral CA1, CA2/3 and in the CA3c/hilus/dentate gyrus. Administration of PGI-02776 immediately following the cessation of hypoxia significantly reduced neuronal and astrocytic cell death across all regions of the hippocampus. These findings indicate that NAAG peptidase inhibitors administered post-injury can significantly reduce the deleterious effects of TBI combined with a secondary hypoxic insult.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury (TBI), Hypoxia, Hippocampus, Neuronal degeneration, Glutamate, N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG), astrocyte

1. Introduction

In the United States, an estimated 1.7 million persons sustain a traumatic brain injury (TBI) resulting in 275,000 hospitalizations and 52,000 deaths annually (Faul et al., 2010). In experimental models of TBI, injury leads to excessive release of glutamate and excitotoxic damage to neurons (Faden et al., 1989; Katayama et al., 1990; Meldrum, 2000). In severe TBI patients, extracellular glutamate is significantly elevated over extended periods of time, and is correlated with lower Glasgow outcome scores at 6-months following injury (Koura et al., 1998). Glutamate induced excitotoxicity, therefore, has been one of the most common targets for neuroprotection following TBI. Pharmacological blockade of glutamate receptors has led to reductions in neurotoxicity and improvements in behavioral outcome in many experimental models, but the translation of this strategy into clinical application remains overwhelmingly disappointing (Bullock et al., 1999; Narayan et al., 2002).

As many as one third of severe TBI patients arrive in the emergency department with significant hypoxia and hypotension (Manley et al., 2001). A hypotensive second insult after TBI, especially paired with increased ICP, leads to a significant shift in patient outcome toward vegetative state and death (Marmarou et al., 1991). Chestnut and colleagues, using the Traumatic Coma Data Bank, demonstrated that hypoxia (PaO2 <= 60 mmHg) or hypotension (SBP < 90 mmHg) were independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality following severe TBI (GCS <=8) (Chesnut et al., 1993). Bullock and colleagues demonstrated that secondary insults could increase the concentration of extracellular glutamate in the hours following injury (Bullock et al., 1998). Several adverse effects of TBI complicated by hypoxia have been described including increased neuronal damage (Bauman et al., 2000; Clark et al., 1997; Nawashiro et al., 1995), exacerbated axonal pathology and neuro-inflammatory response (Goodman et al., 2011; Hellewell et al., 2010), and exacerbated sensorimotor and cognitive deficits (Bauman et al., 2000; Clark et al., 1997). Laboratory studies have also demonstrated that secondary insults of hypoxia and ischemia exacerbate neuronal death and behavioral deficits in animal models of TBI (Aoyama et al., 2008; Bauman et al., 2000; Clark et al., 1997; Nawashiro et al., 1995).

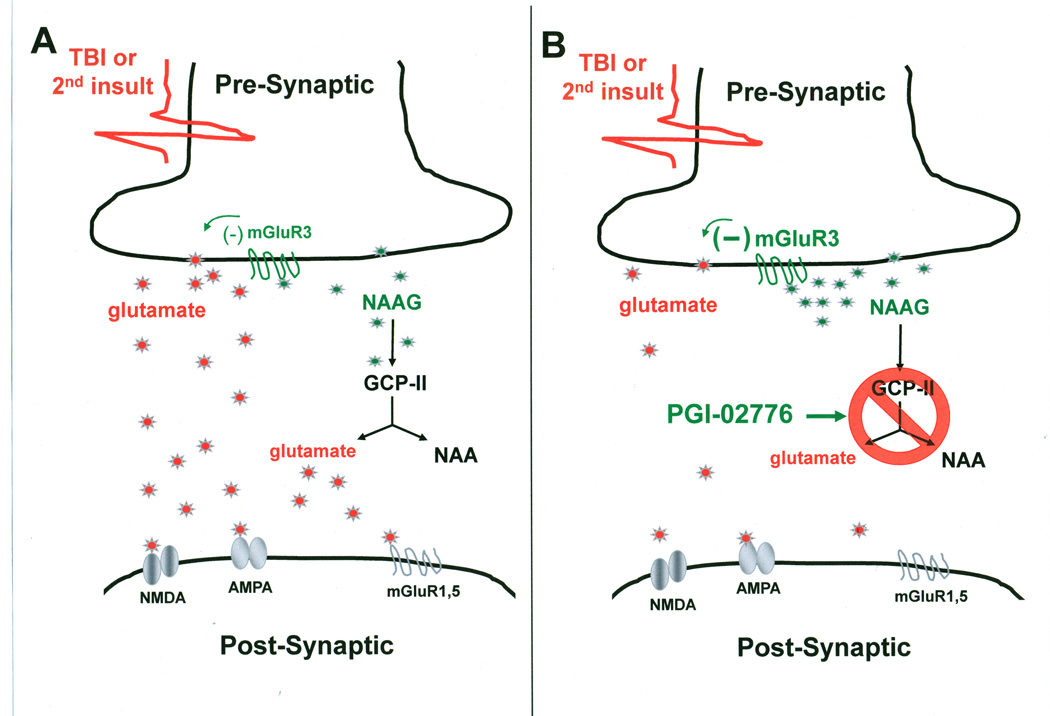

N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) is an abundant peptide neurotransmitter found in millimolar concentrations in the mammalian brain and is co-distributed with small amino transmitters including glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Coyle, 1997; Neale et al., 2000). NAAG selectively activates the group II metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 3 (mGluR3) thereby modulating the release of glutamate into the synapse (Figure 1) (Sanabria et al., 2004; Xi et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2001; Zhong et al., 2006). Thus, NAAG potentially acts as an endogenous modulator of glutamate excitotoxicity. However, synaptically released NAAG is rapidly hydrolyzed to NAA and glutamate by the NAAG peptidase catalytic enzymes, glutamate carboxypeptidase II and III (GCP II and GCP III) (Bzdega et al., 2004; Luthi-Carter et al., 1998). Pharmacological inhibition of GCP II has been proposed as a strategy for reducing glutamate excitotoxicity (Neale et al., 2000; Neale et al., 2005; Schweitzer et al., 2000; Wroblewska et al., 1997; Wroblewska et al., 1998; Wroblewska, 2006).

Figure 1.

Actions of NAAG and NAAG inhibitors at the glutamate synapse. (A) TBI and secondary insults such as hypoxia produce a large release of glutamate and NAAG into the synapse. NAAG preferentially binds to and activates pre-synaptic glutamate receptors (mGluR3) as inhibitory autoreceptors that reduce the release of glutamate. The actions of NAAG are short-lived since the peptidase, GCP-II rapidly hydrolyzes NAAG into free glutamate and NAA. Glutamate from presynaptic release and from hydrolysis of NAAG activates the various postsynaptic glutamate receptors resulting in excitotoxicity. (B) Application of PGI-02776 after TBI and secondary insults inhibits the action of GCP-II thereby preventing the hydrolysis of NAAG. Thus, the concentration of NAAG accumulates resulting in further activation of mGluR3 leading to increased inhibiition of glutamate release. NAAG hydrolysis as a secondary source of glutamate is also blocked by the inhibition of GCP-II. Thus, application of PGI-02776 reduces the concentration of synaptic glutamate and subsequently reduces excitotoxicity.

Previously, we have demonstrated that inhibition of GCP II with the urea-based NAAG peptidase inhibitor ZJ-43 immediately prior to TBI increased the concentration of extracellular NAAG while decreasing the concentrations of glutamate, aspartate and GABA, as measured by microdialysis (Zhong et al., 2006). These findings translated into a decrease in acute neuronal and astrocytic cell death when ZJ-43 was administered either immediately prior to, or following TBI (Zhong et al., 2005). In the present study, PGI-02776, a di-ester prodrug version of the NAAG peptidase inhibitor ZJ-43, was tested for neuroprotective potential when administered systemically 30-minutes after fluid percussion TBI combined with an immediate 30-minute hypoxic (FiO2 11%) second insult in the rat. Acute hippocampal neuronal and astrocytic loss was assessed 24-hrs following fluid percussion TBI in rats to determine the efficacy of PGI-02776 as a potential treatment for TBI.

2. Results

2.1 Descriptive Parameters

There were no significant differences between groups in body weight, injury magnitude, temporalis muscle temperature pre-TBI or post-TBI, and rectal temperature pre-TBI or post-TBI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Groups and Parameters (Values are Mean ± SD)

| Group | n | Weight (g) |

TBI (ATM) |

Temporalis temp (°C) | Rectal temp (°C) | ||

| Pre-TBI | Post-TBI | Pre-TBI | Post- TBI |

||||

| TBI + normoxia/saline | 8 | 335±13 | 2.15±0.01 | 35.7±0.2 | 35.8±0.3 | 37.0±0.2 | 37.0±0.2 |

| TBI + hypoxia/saline | 9 | 339±10 | 2.14±0.01 | 36.0±0.3 | 36.0±0.3 | 37.1±0.2 | 36.9±0.3 |

| TBI + hypoxia/PGI-02776 | 10 | 338±9 | 2.15±0.01 | 36.0±0.3 | 35.9±0.3 | 37.0±0.3 | 37.0±0.3 |

2.2 Neuronal Degeneration

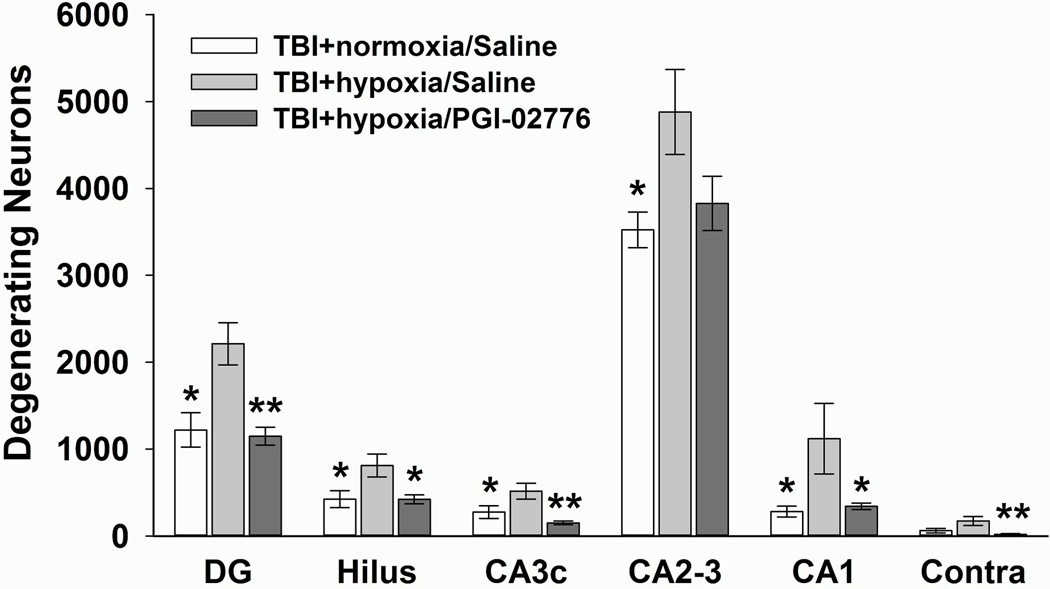

FJ-B positive cells were found throughout the ipsilateral hippocampus (Figure 2B, D, E, F). Quantification of the numbers of degenerating neurons revealed significantly differences among the three groups in ipsilateral CA1 [F(2,24) = 3.844, p = 0.036], CA2–3 [F(2,24) = 3.749, p = 0.038], CA3c [F(2,24) = 8.210, p = 0.002], hilus [F(2,24) = 5.291, p = 0.012], dentate gyrus (DG) [F(2,24) = 10.362, p = 0.001], and in the contralateral DG and hilus [F(2,24) = 6.037, p = 0.008]. Post hoc analysis revealed that the TBI+hypoxia/saline group had significantly increased numbers of degenerating neurons compared to the TBI+normoxia/saline group in each of the ipsilateral hippocampal fields (p < 0.05) (Figure 4). Treatment with PGI-02776 significantly reduced numbers of degenerating neurons compared to the TBI+hypoxia/saline group in all ipsilateral hippocampal fields (p < 0.05), except in the CA2–3 where there was a trend (p = 0.083) for reduced numbers of degenerating neurons.

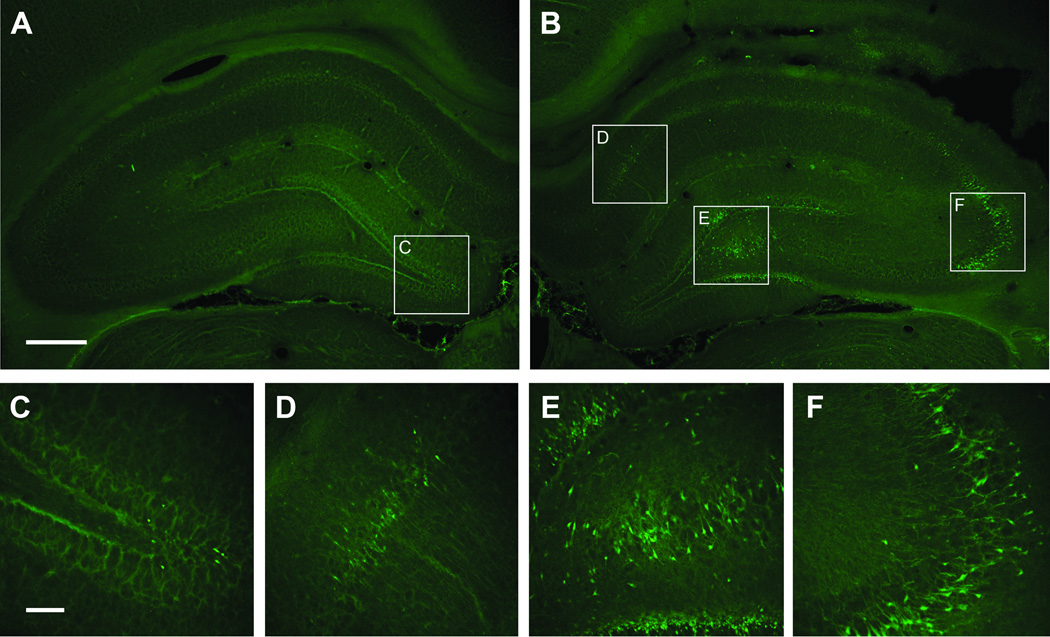

Figure 2.

Fluoro-Jade B histofluorescence of degenerating neurons 24 hrs after injury in the dorsal hippocampus. The micrographs are representative coronal sections (−3.6 mm Bregma) of the contralateral hippocampus (A, C) and the ipsilateral hippocampus (B, D, E, F) from a typical rat in TBI hypoxia + saline group. In the contralateral hippocampus, degenerating neurons were found only in DG and Hilus (C). In the ipsilateral hippocampus, degenerating neurons were found in the CA1 (D), the hilus and granular layer (E), and the CA2–3 (F). Calibration bars: A, B = 100 µm; C, D, E, F = 20 µm.

Figure 4.

Quantification of degenerating neurons in the hippocampus 24 hrs after TBI combined with hypoxia. Degenerating neurons were quantified using stereological techniques in the dorsal hippocampal fields in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. In the ipsilateral hippocampus, 30 min of post-TBI hypoxia significantly increased the numbers of degenerating neurons in the saline-treated group. Treatment with PGI-02776 at 30 min post-TBI in TBI+hypoxia condition significantly reduced the numbers of degenerating neurons in all fields except the CA2–3. In the contralateral DG/hilus (labeled Contra), treatment with PGI-02776 significantly reduced the number of degenerating neurons. Values are means ± standard error of the mean. * p<0.05 and ** p<0.01 compared to the TBI+hypoxia/saline.

In the contralateral hippocampus, degenerating neurons were only found in the regions of the DG granule cells and hilus (Figure 2A, C) and quantification revealed much lower numbers than in the ipsilateral hippocampus. The TBI+hypoxia/saline group had a trend for increased numbers of degenerating compared to TBI+normoxia/saline group (p = 0.054). Animals treated with PGI-02776 had significantly decreased numbers of degenerating neurons in the contralateral DG/hilus compared to the TBI+hypoxia/saline group (p<0.01) (Figure 4).

2.3 Astrocyte Cell Morphology and Death

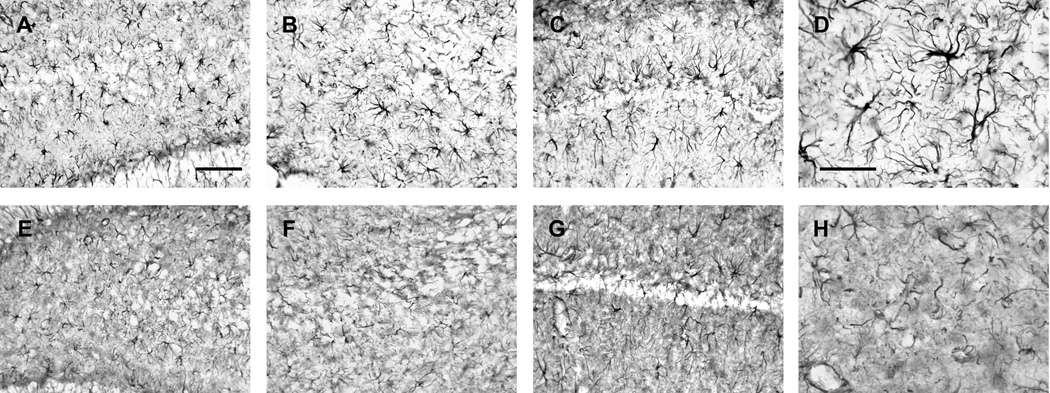

Astrocytes labeled by glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity in the contralateral hippocampus had distinct cell soma and clearly identifiable processes 24-hrs after injury (Figure 3D). In contrast, TBI, with hypoxia, produced a clearly visible change in GFAP immunoreactivity in the ipsilateral hippocampus with a loss of GFAP staining intensity and reduction in process complexity (i.e., fewer processes, reduced branching) (Figure 3H). Visual examination of astrocytes in the ipsilateral CA1, CA2–3, and DG/hilus regions revealed reduced GFAP immunofluorescence with fewer astrocytes with identifiable morphology (Figure 3E, F, G, H) compared to the relative intact morphology of astrocytes in the contralateral hippocampus (Figure 3A, B, C, D).

Figure 3.

GFAP immunoreactivity of astrocytes in hippocampal subregions 24 hrs after injury in the dorsal hippocampus. The micrographs are representative coronal sections (−3.6 mm Bregma) of the contralateral hippocampus (A, B, C, D) and ipsilateral hippocampus (E, F, G, H) from a typical rat in TBI hypoxia + saline group. The contralateral hilus (A), CA3 (B), and CA1 (C) show a normal pattern of GFAP immunoreactivity with distinct astrocyte morphology. In contrast, the ipsilateral hilus (E), CA3 (F), and CA1 (G) show a very different pattern of GFAP immunoreactivity with reduced number of intact astrocytes and the darkened background compared to the contralateral hippocampus. Under high magnification, note the distinct cell soma and clearly identifiable foot processes in the contralateral micrograph (D) compared to the ipsilateral micrograph showing astrocytes with a fragmented appearance and a reduction in process complexity (H). Calibration bars: A, B, C, E, F, G = 50 µm; D, H = 10 µm.

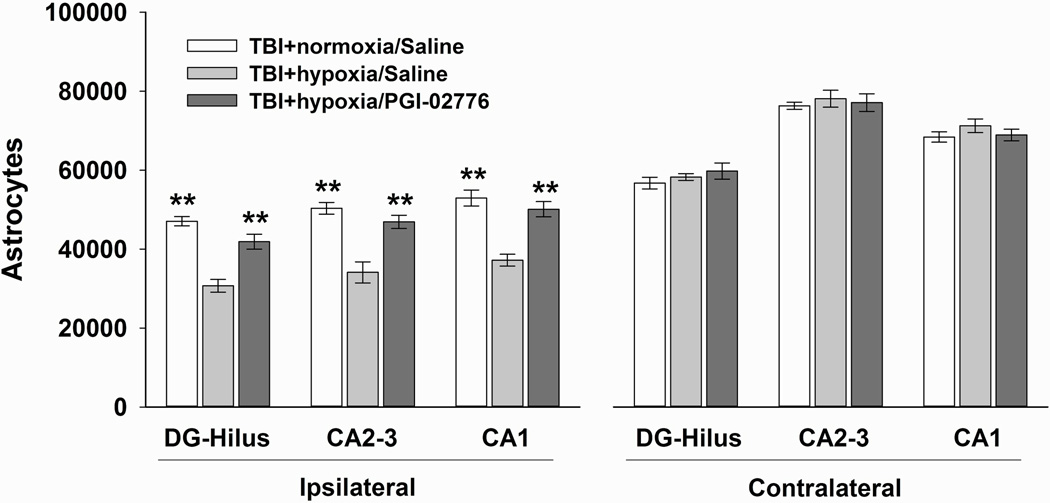

The numbers of GFAP positive astrocytes were significantly different among the three groups in ipsilateral CA1 [F(2,24) = 20.369, p < 0.001], CA2–3 [F(2,24) = 17.331, p <0.001], and DG/hilus regions [F(2,24) = 24.883, p <0.001]. Post hoc analysis revealed that the TBI+hypoxia/saline group had significantly decreased numbers of intact astrocytes compared to the TBI+normoxia/saline group in the CA1 (p<0.01), CA2–3 (p<0.01), and the DG/Hilus regions (p<0.01) (Figure 5). Treatment with PGI-02776 significantly increased numbers of intact astrocytes in each of the regions of interest compared to the TBI+normoxia/saline group (p<0.01).

Figure 5.

Quantification of GFAP labeled astrocytes in the hippocampus 24 hrs after TBI with hypoxia. Intact astrocytes were quantified in the dorsal hippocampal fields in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. In the ipsilateral hippocampus, 30 min of post-TBI hypoxia significantly reduced the numbers of intact astrocytes in the saline-treated group. Treatment with PGI-02776 at 30 min post-TBI in TBI+hypoxia condition significantly increased the numbers of intact astrocytes in all fields. In the contralateral hippocampus, there were no differences in astrocyte numbers between groups. In general, there were more intact astrocytes in the contralateral hippocampus. Values are means ± standard error of the mean. ** p<0.01 compared to TBI+hypoxia/saline.

In the contralateral hippocampus, there was no difference in the number of astrocytes between conditions in any of the three hippocampal fields (p>0.05) (Figure 5). Comparing the numbers of intact astrocytes across hemispheres between the TBI+normoxia/saline and the TBI+hypoxia/saline groups, there were significant decreases in the number of intact astrocytes in the ipsilateral as compared to the contralateral CA1 [t(14)=6.38, p<0.001], CA2–3 [t(14)=14.99, p<0.001], and DG/hilus [t(14)=5.16, p<0.001].

3. Discussion

In this study, rats were subjected to moderate lateral fluid percussion TBI followed immediately with either 30 minutes of hypoxia (FiO2 =11%) or normoxia (FiO2 =33%). TBI+hypoxia rats were administered either saline or the urea-based NAAG peptidase inhibitor, PGI-02776 (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 minute post-injury at the conclusion of controlled ventilation. The secondary hypoxia condition significantly increased acute hippocampal neuronal degeneration and significantly decreased the number of intact hippocampal astrocytes compared to the normoxia condition in each hippocampal sub-region. Treatment with PGI-02776 significantly reduced acute neuronal degeneration and significantly increased the number of immunostained astrocytes compared to saline-treated TBI rats maintained with normoxia. Therefore, post-injury administration of PGI-02776 significantly attenuated the deleterious effects of secondary hypoxia after TBI.

NAAG is an abundant peptide that is co-released with small amine transmitters, including glutamate and GABA, during intense neuronal stimulation (Coyle, 1997; Neale et al., 2000). NAAG selectively activates the presynaptic group II metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 3 (mGluR3) (Neale et al., 2000; Schweitzer et al., 2000; Wroblewska et al., 1997; Wroblewska et al., 1998; Wroblewska, 2006) and reduces the subsequent release of neurotransmitter thus acting as a negative feedback loop (Figure 1A) (Sanabria et al., 2004; Xi et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2001; Zhong et al., 2006). The NAAG peptidase catalytic enzymes GCP II and GCP III hydrolyze NAAG resulting in the breakdown products of NAA and glutamate and the termination of presynaptic inhibition (Bzdega et al., 2004; Luthi-Carter et al., 1998). A series of in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that inhibition of GCP II and GCP III increases the extracellular levels of NAAG, moderates the release of glutamate, and reduces excitotoxicity (Figure 1B) (Neale et al., 2005; Tsukamoto et al., 2007). Previously we have reported that the NAAG peptidase inhibitor ZJ-43 increased the concentration of NAAG in the synapse and reduced the release of glutamate, asparate and GABA into the extracellular space following moderate lateral fluid percussion TBI (Zhong et al., 2006). Administration of the mGluR3 antagonist LY341495 confirmed that ZJ-43 was reducing glutamate, aspartate and GABA release by increasing NAAG-induced pre-synaptic inhibition. Moreover, when administered either prior to or immediately following TBI ZJ-43 significantly reduced acute neuronal degeneration and acute loss of GFAP immunoreactivity 24 hours post-injury (Zhong et al., 2005). Therefore the NAAG peptidase inhibitor ZJ-43 has demonstrated significant potential as a neuroprotective compound to reduce excitotoxicity following TBI.

PGI-02776 is a di-ester prodrug designed by modification of the urea-based NAAG peptidase inhibitor ZJ-43 (Olszewski et al., 2004; Yamamoto et al., 2004; Zhong et al., 2005; Zhong et al., 2006). The esters with long alkyl chains act as a lipophilic carrier to enhance blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration compared to the parent ZJ-43 compound. Previously we have demonstrated that PGI-02776 (100 mg/kg) crosses the BBB in uninjured mice with concentrations peaking at 2 hours following injection and significant drug remaining 6 hours following injury (Feng et al., 2011). However, following TBI, blood-brain barrier integrity is compromised (Jiang et al., 1992) which likely leads to greater permeability of the drug. Earlier studies demonstrated that administration of PGI-02776 30-minutes following moderate lateral fluid percussion TBI led to a significant decrease in cell death in the first 24 hour following TBI and an improvement in cognitive performance in the Morris water maze (Feng et al., 2011).

Unlike in humans, where extracellular levels of glutamate can remain elevated for hours following injury (Bullock et al., 1998), following TBI in the rat there is a spike in extracellular glutamate, measured by microdialysis, that peaks in the first minutes following injury and returns to baseline within the first 15–30 minutes (Matsushita et al., 2000; Zhong et al., 2006). However, when TBI is accompanied by a second insult, such as hypoxia, extracellular glutamate is elevated for a much longer period of time in both humans and in experimental models (Bullock et al., 1998; Matsushita et al., 2000). TBI patients with significantly elevated mean extracellular glutamate levels tend to have worse scores on the Glasgow outcome scale (Koura et al., 1998). Previous rodent studies demonstrated that TBI with imposed secondary hypoxia significantly increased acute cell death across the injured hippocampus (Bramlett et al., 1999; Feng et al., 2012) and led to a reduction in cognitive performance as compared to TBI alone (Bramlett et al., 1999). Furthermore, we now demonstrate that the TBI with 30-minutes of hypoxia also leads to a significant reduction in hippocampal GFAP positive cells ipsilateral to the injury. Previous studies have demonstrated that both ischemia and TBI result in early loss of astrocytes in brain regions that have significant neuronal cell loss (Liu et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2003). Administration of PGI-02776 30 minutes following TBI (immediately following the termination of hypoxia) significantly reduced the amount of neuronal and astrocytic cell death to levels similar to that of TBI with normoxia. In the present study, animals receiving TBI+hypoxia likely experienced extended periods of elevated extracellular glutamate (Matsushita et al., 2000). Thus, it appears that increasing extracellular NAAG levels by inhibiting the activity of GCP II during this period of elevated extracellular glutamate attenuated cell death related to the second insult.

These data continue to support the development of NAAG peptidase inhibitors as potential therapeutics to reduce glutamate-induced excitotoxicity following TBI and TBI with second insults. Not only do NAAG peptidase inhibitors have a well-characterized mechanism of action, they also act on a system that does not disrupt physiological transmission of information via glutamate release under normal conditions therefore making GCP II inhibition an attractive target for neuroprotection. The effectiveness of PGI-02776 in ameliorating the effects of secondary hypoxia in the present study indicated the potential utility of this therapeutic strategy for treating secondary insults that may occur even hours after the primary TBI.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1 Subjects

Twenty seven male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan) weighing 320–350 grams were used in this study. Animals were housed in individual cages in a temperature (22°C) and humidity-controlled (50% relative) animal facility with a 12-hr light/dark cycle. Animals had free access to food and water during the duration of the experiments. Animals remained in the animal facility for at least 7 days prior to surgery. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California at Davis approved all animal procedures in the following experiments.

4.2 Preparation and Administration of PGI-02776

PGI-02776 was synthesized and generously donated by the laboratory of Dr. Zhou (PsychoGenics, Tarrytown NY). It is a di-ester prodrug form of the urea-based NAAG peptidase inhibitor ZJ-43 (Feng et al., 2011). PGI-02776 (10mg/ml) was dissolved in sterile 0.9 percent saline and injected intraperitoneal (i.p.) at a volume of 1ml/kg. PGI-02776 or equal volume saline was administered 30-minutes following TBI.

4.3 Experimental Design

All animals were subjected to moderate lateral fluid percussion TBI. Following injury animals were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. In the first condition, TBI+normoxia/saline rats remained ventilated under normoxic conditions (FiO2 = 33%) for 30-minutes following injury and were administered saline (1ml/kg) i.p. 30-minutes following injury. In the second condition, TBI+hypoxia/saline,rats were ventilated under hypoxic conditions (FiO2 = 11%) for 30-minutes following injury and then administered saline (1ml/kg) i.p. In the third condition, TBI+hypoxia/PGI, rats were ventilated under hypoxic conditions (FiO2 = 11%) for 30-minutes following injury and then administered PGI-02776 (10 mg/kg). All the animals were euthanized at 24 hrs after TBI and brain tissue processed for analysis of acute neuronal degeneration and astrocyte damage.

4.4 Surgical Procedure

Rats were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane in a carrier gas mixture of nitrous oxide/oxygen (2:1 ratio), intubated, and mechanically ventilated with a rodent volume ventilator (Harvard Apparatus model 683, Holliston, MA). A surgical level of anesthesia was maintained with 2% isoflurane. Rats were mounted in a stereotaxic frame, a scalp incision made along the midline, and a 4.8-mm diameter craniectomy was performed on the right parietal bone (centered at −4.5 mm Bregma and right lateral 3.0 mm). A rigid plastic injury tube (modified Leur-loc needle hub, 2.6-mm inside diameter) was secured over the exposed, intact dura with cyanoacrylate adhesive. Two skull screws (2.1 mm diameter, 6.0 mm length) were placed into burr holes, 1 mm rostral to Bregma and 1 mm caudal to Lambda. The injury tube was secured to the skull and screws with cranioplastic cement (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA). Rectal temperature was continuously monitored and maintained within normal ranges during surgical preparation by a feedback temperature controller pad (CWE model TC-1000, Ardmore, PA). Temporalis muscle temperature was measured by insertion of a 29-gauge needle temperature probe (Physitemp unit TH-5, probe MT-29/2, Clifton, NJ) between the skull and temporalis muscle.

4.5 Traumatic Brain Injury

Experimental TBI was produced using a fluid percussion device (VCU Biomedical Engineering, Richmond, VA) (Dixon et al., 1987) using the lateral orientation (McIntosh et al., 1989). The device consists of a Plexiglas cylindrical reservoir filled with isotonic saline. One end of the reservoir has a Plexiglas piston mounted on O-rings and the opposite end has a transducer housing with a 2.6 mm inside diameter male luer-loc opening. Injury was induced by the descent of a pendulum striking the piston, which injects a small volume of saline epidurally into the closed cranial cavity, producing a brief displacement and deformation of neural tissue. The resulting pressure pulse was measured in atmospheres (ATM) by an extracranial transducer (model SPTmV0100PG5W02; Sensym ICT) and recorded on a digital storage oscilloscope (model TDS 1002; Tektronix Inc., Beaverton, OR).

Rats were disconnected from the ventilator, the injury tube connected to the fluid percussion cylinder, and a moderate fluid percussion pulse (2.12 – 2.16 ATM) was delivered within ten seconds. Immediately after TBI rats were returned to ventilation with 1% isoflurane in either normoxic or hypoxic carrier gas conditions. The plastic injury tube and skull screws were removed immediately after TBI and the scalp incision was closed with 4-0 braided silk sutures.

4.6 Ventilation and controlled hypoxia

While true normoxia in room air has an FiO2 ~ 21%, we elected to maintain “experimental normoxia” with a ventilatory mixture of nitrous oxide/oxygen (2:1) to produce an FiO2=33% which has been used in many rat TBI studies (Feng et al., 2012; Lyeth et al., 1993; Phillips et al., 1994). Henceforth in this manuscript “normoxia” refers to “experimental normoxia” with an FiO2 = 33%. Hypoxia was maintained with a carrier gas mixture to 1:1 nitrous oxide/air (hypoxia FiO2 = 11%). At the conclusion of these procedures, isoflurane was discontinued and animals were extubated as soon as spontaneous breathing was observed.

4.7 Tissue Collection and Sectioning

Rats were euthanized 24-hrs after TBI by deep sodium pentobarbital anesthesia (100 mg/kg, ip) followed by transcardial perfusion with 100 ml of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (PB) (pH = 7.4) followed by 350 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4). Brains were removed and post-fixed for 1 hr in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. Then brains were cryoprotected in 10% sucrose solution for 1 day followed by 2 days in a 30% sucrose solution, frozen on powdered dry ice, and 45 µm coronal sections were cut on a sliding microtome (American Optical, Model 860). Every serial section starting at −2.12 mm Bregma and ending at −4.80 mm Bregma was saved in 24-well cell culture plates. Systematic random sampling techniques were used for selecting tissue sections for staining and stereological analysis.

4.8 Acute Neuronal Degeneration

Acute neuronal degeneration was assessed 24 hrs after TBI using the histofluorescent stain, Fluoro-Jade B (FJ-B). Tissue sections for FJ-B staining were selected by taking every fifth section starting at Bregma −3.1 mm and ending at Bregma −4.7 mm for a total of 7 sample sections per brain. Tissue sections were mounted onto gelatin-coated slides in a 1:1 ratio of 0.1 M PB and distilled H2O (dH2O) and air-dried overnight. The slide-mounted tissue sections were subsequently immersed in 100% alcohol (3 min), 70% alcohol (1 min), dH2O (1 min), and 0.006% potassium permanganate (15 min). Sections were rinsed in dH2O (1 min), incubated in 0.001% FJ-B (Histo-Chem Inc., Pine Bluff, AK) staining solution in 0.1% acetic acid for 30 min, rinsed again in dH2O (3 min), and air-dried. Finally, the sections were immersed in xylene and coverslipped with DePeX mounting medium (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA).

4.9 Acute Astrocyte Damage

Astrocyte damage was assessed at 24-hrs after TBI by quantifying the total number of GFAP positive cells. A total of 7 tissue sections from each animal, taken from adjacent sections used for FJ-B staining, were used for GFAP Immunohistochemistry. Free-floating tissue sections were washed three times (3 minutes each) in 0.1 M PB with agitation. Sections were incubated in 1.5% horse serum containing 0.3% Triton X-100 in 0.1 M PB for 1 hr at 37°C. The sections were then transferred without wash and incubated with anti-GFAP antibody (monoclonal, mouse, 1:2000, ICN Biomed. Inc., Aurora, OH) in PB for 1 hr at room temperature on a shaker followed by 24-hr incubation at 37°C. After three washes (10 minutes each) in PB, the sections were then incubated in secondary antibody (horse anti-mouse IgG, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 10 minute on a shaker at room temperature followed by 1 hr at 37°C. Sections were then washed three times in PB (3 minutes each) and incubated with avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vectastain Elite ABC kit PK6102, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 2 hrs at room temperature. Following three washes in PB (3 minutes each), the sections were visualized with a peroxidase substrate (Vector SG substrate kit, SK-4700, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The reaction was stopped by transferring the sections into PB, following by two 5 minute washes in PB with agitation. Finally, the sections were mounted on gelatin-chrome alum coated glass slides and allowed to dry in air, and then dehydrated serially in alcohol and coverslipped with DePeX mounting medium. The immuno-labeled products were visible as blue/gray stained cells under a light microscope with distinct astrocyte cell morphology. Control immunostaining experiments included identical immunohistochemistry procedures, but without the primary antibody or without the secondary antibody.

4.10 Hippocampal Regions of Interest

Neuronal loss was separately assessed in ipsilateral hippocampal fields: CA1, CA2–3, CA3c, hilus, and the granular layer of the DG as well as in the entire contra-lateral hippocampus (Figure 2A). The medial boundary point of CA1 was recognized at the corner of stratum pyramidale adjacent to the midline. And the lateral boundary point of CA1 was the widening of the stratum pyramidale at the border of the CA2, which also served as the superior boundary of CA2–3. A line connecting the lateral tips of the superior and inferior blades of the granule layer of DG was set as the inferior boundary of CA2–3. The pyramidal neurons between the superior and inferior blades of dentate granular cells were counted as neurons in CA3c. Degenerating polymorphic neurons in the hilar region and granular neurons in DG were also separately assessed. In the contralateral hippocampus FJ-B positive cells were only observed in the DG and hilus and in low numbers (Figure 2A,C); thus, quantitation in the contralateral hippocampus was limited to the combined DG and hilus fields.

Astrocyte damage was assessed separately in three hippocampal fields: the CA1 incorporating the strata oriens, pyramidale, and radiatum; the CA2/3 incorporating the strata oriens, pyramidale, and radiatum and bounded by a straight line connecting the lateral tips of the superior and inferior blades of the granule layer of the DG; and the combined dentate gyrus/hilus/CA3c (DG-hilus) incorporating the molecular, granule cell, and polymorphic layers of the DG and bounded laterally by a straight line connecting the lateral tips of the superior and inferior blades of the granule layer of the DG.

4.11 Stereological Cell Counts

Investigators were blind to the injury and treatment condition for cell quantification. The total number of GFAP-labeled astrocytes or Fluoro-Jade B positive degenerating neurons was assessed using the optical fractionator technique (West et al., 1991) with a computer-based system, Stereologer™ (version 1.3, Systems Planning & Analysis, Inc., Alexandria, VA). The equipment consisted of a microscope (E600, Nikon, Tokyo) with a motorized stage (MS-2000, Applied Scientific Instruments, Eugene OR) and color CCD camera (LE-470, Optronics, Goleta, CA). The camera’s digital output was processed by a high-resolution video card (Bandit, Coreco Inc., St. Laurent, Quebec) and displayed on a computer monitor (PF 775, Viewsonic, Walnut, CA). The Stereologer™ software controlled operation of the system. The optical fractionator technique combines the optical dissector method described by Sterio (Sterio, 1984) and the fractionator method described by Gundersen (Gundersen, 1986) for making unbiased estimates of objects in a three dimensional space.

Sections stained with FJ-B were examined under a mercury arc lamp with a FITC fluorescence filter cube (Nikon B-2A, Tokyo) (Schmued et al., 1997; Schmued and Hopkins, 2000). Criterion for counting degenerating neurons (FJ-B positive) included green fluorescing, morphologically distinct cell bodies. Neuronal identification and cell counting were performed with a 20X objective (Plan Apo, NA 0.95, Nikon). In this study, the ASF (area sampling fraction) and TSF (thickness sampling fraction) were both set to 100. As the density of FJ-B positive neurons is not equal across the regions of interest all degenerating cells were counted. SSF (section sampling fraction) was 0.20 (1 sample section out of 5 sections).

Criterion for counting astrocytes included morphologically distinct cell bodies and clearly identifiable foot projections. A 2X objective (Plan Apo, NA 0.10, Nikon) (on-screen magnification = 161X) was used to outline each region of interest. Astrocyte identification and cell counting were performed with a 40X objective (Plan Apo, NA 0.95, Nikon) (on-screen magnification = 3138X). The sampling parameters used for estimate of astrocyte number in each animal were as follows: SSF = 0.20, TSF = 0.71, and ASF = 0.076. Astrocyte number was compared between ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampi.

4.12 Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (Version 17, Chicago IL), which adheres to a general linear model. Alpha level for Type I error was set at 0.05 for rejecting null hypotheses. Data for body weights, fluid percussion injury magnitudes, and temperature measurements were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed with one-way ANOVAS. All other data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Degenerating neuronal counts from FJ-B staining and survival astrocyte counts from GFAP staining were each analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for each region followed by a Dunnett post hoc analysis using the TBI+Hypoxia/saline group as the control comparison.

Research Highlights.

TBI combined with 30 min hypoxia exacerbates neural degeneration in hippocampus.

TBI combined with 30 min hypoxia exacerbates astrocyte cell loss hippocampus at 24 hrs after injury.

PGI-02776 significantly reduced acute neuronal degeneration after TBI in rats

PGI-02776 significantly reduced astrocyte loss after TBI in rats.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH NS61352 (JZ) and NIH NS29995 (BGL).

Abbreviations used

- ATM

atmosphere

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CA1

Cornu Ammonis area 1

- CCD

charge-coupled device

- CNS

central nervous system

- DG

dentate gyrus

- dH2O

distilled water

- FiO2

fraction of inspired oxygen

- FJ-B

Fluoro-Jade B

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- GCP II

glutamate carboxypeptidase II

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- i.p

intraperitoneal

- mGluR3

metabotropic glutamate receptor (subtype 3)

- NAA

N-acetylaspartate

- NAAG

N-acetylaspartylglutamate

- PB

phosphate buffer

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aoyama N, Lee SM, Moro N, Hovda DA, Sutton RL. Duration of ATP reduction affects extent of CA1 cell death in rat models of fluid percussion injury combined with secondary ischemia. Brain research. 2008;1230:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman RA, Widholm JJ, Petras JM, McBride K, Long JB. Secondary hypoxemia exacerbates the reduction of visual discrimination accuracy and neuronal cell density in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus resulting from fluid percussion injury. Journal of neurotrauma. 2000;17:679–693. doi: 10.1089/089771500415427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett HM, Green EJ, Dietrich WD. Exacerbation of cortical and hippocampal CA1 damage due to posttraumatic hypoxia following moderate fluid-percussion brain injury in rats. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:653–659. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.4.0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock MR, Lyeth BG, Muizelaar JP. Current status of neuroprotection trials for traumatic brain injury: lessons from animal models and clinical studies. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:207–217. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199908000-00001. discussion 217-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock R, Zauner A, Woodward JJ, Myseros J, Choi SC, Ward JD, Marmarou A, Young HF. Factors affecting excitatory amino acid release following severe human head injury. Journal of neurosurgery. 1998;89:507–518. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.4.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdega T, Crowe SL, Ramadan ER, Sciarretta KH, Olszewski RT, Ojeifo OA, Rafalski VA, Wroblewska B, Neale JH. The cloning and characterization of a second brain enzyme with NAAG peptidase activity. Journal of neurochemistry. 2004;89:627–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnut RM, Marshall SB, Piek J, Blunt BA, Klauber MR, Marshall LF. Early and late systemic hypotension as a frequent and fundamental source of cerebral ischemia following severe brain injury in the Traumatic Coma Data Bank. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1993;59:121–125. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9302-0_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RS, Kochanek PM, Dixon CE, Chen M, Marion DW, Heineman S, DeKosky ST, Graham SH. Early neuropathologic effects of mild or moderate hypoxemia after controlled cortical impact injury in rats. Journal of neurotrauma. 1997;14:179–189. doi: 10.1089/neu.1997.14.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT. The nagging question of the function of N-acetylaspartylglutamate. Neurobiology of disease. 1997;4:231–238. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1997.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon CE, Lyeth BG, Povlishock JT, Findling RL, Hamm RJ, Marmarou A, Young HF, Hayes RL. A fluid percussion model of experimental brain injury in the rat. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:110–119. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.1.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden AI, Demediuk P, Panter SS, Vink R. The role of excitatory amino acids and NMDA receptors in traumatic brain injury. Science. 1989;244:798–800. doi: 10.1126/science.2567056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul M, Xu L, Wald MM, Coronado VG. In: Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths 2002–2006. C.f.D.C.a. Prevention, editor. Vol. Atlanta: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Feng JF, Van KC, Gurkoff GG, Kopriva C, Olszewski RT, Song M, Sun S, Xu M, Neale JH, Yuen PW, Lowe DA, Zhou J, Lyeth BG. Post-injury administration of NAAG peptidase inhibitor prodrug, PGI-02776, in experimental TBI. Brain research. 2011;1395:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng JF, Zhao X, Gurkoff GG, Van KC, Shahlaie K, Lyeth BG. Post-traumatic hypoxia exacerbates neuronal cell death in the hippocampus. Journal of neurotrauma. 2012;29:1167–1179. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MD, Makley AT, Huber NL, Clarke CN, Friend LA, Schuster RM, Bailey SR, Barnes SL, Dorlac WC, Johannigman JA, Lentsch AB, Pritts TA. Hypobaric hypoxia exacerbates the neuroinflammatory response to traumatic brain injury. J Surg Res. 2011;165:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ. Stereology of arbitrary particles. A review of unbiased number and size estimators and the presentation of some new ones, in memory of William R. Thompson. Journal of microscopy. 1986;143:3–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellewell SC, Yan EB, Agyapomaa DA, Bye N, Morganti-Kossmann MC. Post-traumatic hypoxia exacerbates brain tissue damage: analysis of axonal injury and glial responses. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1997–2010. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang JY, Lyeth BG, Kapasi MZ, Jenkins LW, Povlishock JT. Moderate hypothermia reduces blood-brain barrier disruption following traumatic brain injury in the rat. Acta neuropathologica. 1992;84:495–500. doi: 10.1007/BF00304468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama Y, Becker DP, Tamura T, Hovda DA. Massive increases in extracellular potassium and the indiscriminate release of glutamate following concussive brain injury. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:889–900. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.6.0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koura SS, Doppenberg EM, Marmarou A, Choi S, Young HF, Bullock R. Relationship between excitatory amino acid release and outcome after severe human head injury. Acta neurochirurgica. 1998;71(Supplement.):244–246. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6475-4_70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Smith CL, Barone FC, Ellison JA, Lysko PG, Li K, Simpson IA. Astrocytic demise precedes delayed neuronal death in focal ischemic rat brain. Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 1999;68:29–41. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthi-Carter R, Barczak AK, Speno H, Coyle JT. Hydrolysis of the neuropeptide N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) by cloned human glutamate carboxypeptidase II. Brain research. 1998;795:341–348. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyeth BG, Liu S, Hamm RJ. Combined scopolamine and morphine treatment of traumatic brain injury in the rat. Brain research. 1993;617:69–75. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90614-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley G, Knudson MM, Morabito D, Damron S, Erickson V, Pitts L. Hypotension, hypoxia, and head injury: frequency, duration, and consequences. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1118–1123. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.10.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarou A, Anderson RL, Ward JD, Choi SC, Young HF, Eisenberg HM, Foulkes MA, Marshall LF, Jane JA. Impact of ICP instability and hypotension on outcome in patients with severe head trauma. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:S59–S66. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita Y, Shima K, Nawashiro H, Wada K. Real-time monitoring of glutamate following fluid percussion brain injury with hypoxia in the rat. Journal of neurotrauma. 2000;17:143–153. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh TK, Vink R, Noble L, Yamakami I, Fernyak S, Soares H, Faden AL. Traumatic brain injury in the rat: characterization of a lateral fluid-percussion model. Neuroscience. 1989;28:233–244. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum BS. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology. J Nutr. 2000;130:1007S–1015S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1007S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan RK, Michel ME, Ansell B, Baethmann A, Biegon A, Bracken MB, Bullock MR, Choi SC, Clifton GL, Contant CF, Coplin WM, Dietrich WD, Ghajar J, Grady SM, Grossman RG, Hall ED, Heetderks W, Hovda DA, Jallo J, Katz RL, Knoller N, Kochanek PM, Maas AI, Majde J, Marion DW, Marmarou A, Marshall LF, McIntosh TK, Miller E, Mohberg N, Muizelaar JP, Pitts LH, Quinn P, Riesenfeld G, Robertson CS, Strauss KI, Teasdale G, Temkin N, Tuma R, Wade C, Walker MD, Weinrich M, Whyte J, Wilberger J, Young AB, Yurkewicz L. Clinical trials in head injury. Journal of neurotrauma. 2002;19:503–557. doi: 10.1089/089771502753754037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawashiro H, Shima K, Chigasaki H. Selective vulnerability of hippocampal CA3 neurons to hypoxia after mild concussion in the rat. Neurol Res. 1995;17:455–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale JH, Bzdega T, Wroblewska B. N-Acetylaspartylglutamate: the most abundant peptide neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system. Journal of neurochemistry. 2000;75:443–452. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale JH, Olszewski RT, Gehl LM, Wroblewska B, Bzdega T. The neurotransmitter N-acetylaspartylglutamate in models of pain, ALS, diabetic neuropathy, CNS injury and schizophrenia. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2005;26:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski RT, Bukhari N, Zhou J, Kozikowski AP, Wroblewski JT, Shamimi-Noori S, Wroblewska B, Bzdega T, Vicini S, Barton FB, Neale JH. NAAG peptidase inhibition reduces locomotor activity and some stereotypes in the PCP model of schizophrenia via group II mGluR. Journal of neurochemistry. 2004;89:876–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LL, Lyeth BG, Hamm RJ, Povlishock JT. Combined fluid percussion brain injury and entorhinal cortical lesion: a model for assessing the interaction between neuroexcitation and deafferentation. Journal of neurotrauma. 1994;11:641–656. doi: 10.1089/neu.1994.11.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria ER, Wozniak KM, Slusher BS, Keller A. GCP II (NAALADase) inhibition suppresses mossy fiber-CA3 synaptic neurotransmission by a presynaptic mechanism. Journal of neurophysiology. 2004;91:182–193. doi: 10.1152/jn.00465.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued LC, Albertson C, Slikker W., Jr Fluoro-Jade: a novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain research. 1997;751:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued LC, Hopkins KJ. Fluoro-Jade B: a high affinity fluorescent marker for the localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain research. 2000;874:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer C, Kratzeisen C, Adam G, Lundstrom K, Malherbe P, Ohresser S, Stadler H, Wichmann J, Woltering T, Mutel V. Characterization of [(3)H]-LY354740 binding to rat mGlu2 and mGlu3 receptors expressed in CHO cells using semliki forest virus vectors. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1700–1706. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterio DC. The unbiased estimation of number and sizes of arbitrary particles using the disector. Journal of microscopy. 1984;134:127–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1984.tb02501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto T, Wozniak KM, Slusher BS. Progress in the discovery and development of glutamate carboxypeptidase II inhibitors. Drug discovery today. 2007;12:767–776. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Slomianka L, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of neurons in thesubdivisions of the rat hippocampus using the optical fractionator. Anat Rec. 1991;231:482–497. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092310411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewska B, Wroblewski JT, Pshenichkin S, Surin A, Sullivan SE, Neale JH. N-acetylaspartylglutamate selectively activates mGluR3 receptors in transfected cells. Journal of neurochemistry. 1997;69:174–181. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewska B, Santi MR, Neale JH. N-acetylaspartylglutamate activates cyclic AMP-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebellar astrocytes. Glia. 1998;24:172–179. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199810)24:2<172::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewska B. NAAG as a neurotransmitter. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2006;576:317–325. doi: 10.1007/0-387-30172-0_23. discussion 361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Baker DA, Shen H, Carson DS, Kalivas PW. Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2002;300:162–171. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Hirasawa S, Wroblewska B, Grajkowska E, Zhou J, Kozikowski A, Wroblewski J, Neale JH. Antinociceptive effects of N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) peptidase inhibitors ZJ-11, ZJ-17 and ZJ-43 in the rat formalin test and in the rat neuropathic pain model. The European journal of neuroscience. 2004;20:483–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Ramadan E, Cappiello M, Wroblewska B, Bzdega T, Neale JH. NAAG inhibits KCl-induced [(3)H]-GABA release via mGluR3, cAMP, PKA and L-type calcium conductance. The European journal of neuroscience. 2001;13:340–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Ahram A, Berman RF, Muizelaar JP, Lyeth BG. Early loss of astrocytes after experimental traumatic brain injury. Glia. 2003;44:140–152. doi: 10.1002/glia.10283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong C, Zhao X, Sarva J, Kozikowski A, Neale JH, Lyeth BG. NAAG peptidase inhibitor reduces acute neuronal degeneration and astrocyte damage following lateral fluid percussion TBI in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:266–276. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong C, Zhao X, Van KC, Bzdega T, Smyth A, Zhou J, Kozikowski AP, Jiang J, O'Connor WT, Berman RF, Neale JH, Lyeth BG. NAAG peptidase inhibitor increases dialysate NAAG and reduces glutamate, aspartate and GABA levels in the dorsal hippocampus following fluid percussion injury in the rat. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1015–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]