Abstract

Host-microbe symbioses involving bacterial endosymbionts comprise some of the most intimate and long-lasting interactions on the planet. While restricted gene flow might be expected due to their intracellular lifestyle, many endosymbionts, especially those that switch hosts, are rampant with mobile DNA and bacteriophages. One endosymbiont, Wolbachia pipientis, infects a vast number of arthropod and nematode species and often has a significant portion of its genome dedicated to prophage sequences of a virus called WO. This phage has challenged fundamental theories of bacteriophage and endosymbiont evolution, namely the phage Modular Theory and bacterial genome stability in obligate intracellular species. WO has also opened up exciting windows into the tripartite interactions between viruses, bacteria, and eukaryotes.

Introduction

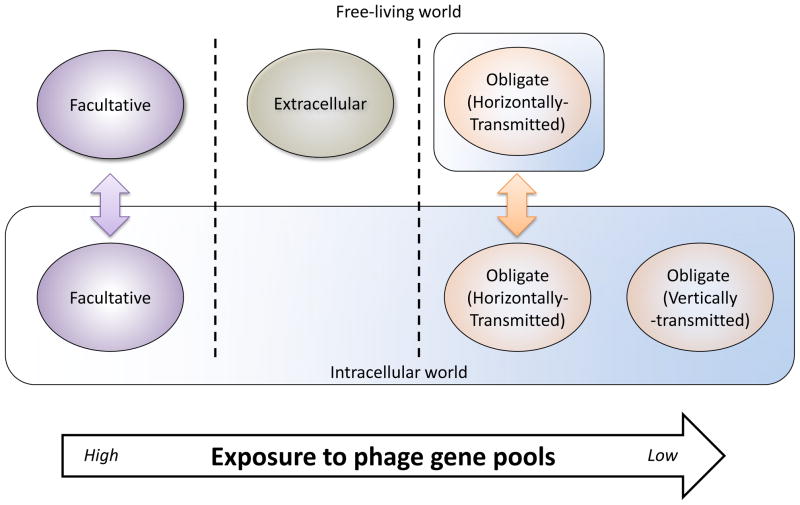

Bacterial endosymbionts that replicate within eukaryotic cells are extremely widespread in nature. In addition to the endosymbiont-derived organelles of mitochondria and chloroplasts, more recently-evolved bacterial endosymbionts are abundant in nature, occurring in virtually all eukaryotic hosts [1]. Historically, obligate intracellular endosymbionts were thought to be devoid of mobile and laterally acquired DNA given their isolated niche, but recent studies have shown that the ecology of bacterial endosymbionts significantly influences the amount of their genome populated by mobile elements such as phages (Fig. 1) [2,3]. Here, we discuss the prevalence of endosymbiont viruses and focus on recent reports describing the evolution, host interactions, and scientific applications of one of the most widespread and well-studied endosymbiont viruses, phage WO.

Figure 1.

Effects of microbial ecology on exposure to phage gene pools. Facultative intracellular bacteria have the largest exposure to bacteriophage genes due to their flexible lifestyle involving both the free-living and intracellular environments; thus, they have the greatest amount of mobile DNA in their genomes. Extracellular bacteria have an intermediate amount of mobile DNA, while obligate intracellular bacteria have the least. However, intracellular bacteria that switch hosts and can be horizontally transmitted often retain a large quantity of mobile DNA including phages.

Prevalence of phages in endosymbionts

Bacteriophages are the most abundant biological entity on Earth, outnumbering their unicellular hosts by at least an order of magnitude [4]. Although free-living bacteria are less restrictive targets for phages, the most recent survey of mobile genetic elements in bacteria has shown that many endosymbionts possess equal amounts of mobile DNA including phages [2]. While endosymbionts that are strictly vertically transmitted from mother to offspring, such as Buchnera, Wigglesworthia, and Blochmannia, often lack phages, the genomes of those that switch hosts, such as Chlamydia, Rickettsia, Phytoplasma, and Wolbachia, often contain a high percentage of mobile DNA [3]. Indeed, 21% of the genome of the wPip strain of Wolbachia pipientis is comprised of mobile DNA, including five prophages [5], and phages are present in Chlamydia pneumoniae isolates throughout the globe [6]. Additionally, endosymbionts not currently infected by phages often show evidence of past infections. For example, wBm, the Wolbachia strain infecting the nematode Brugia malayi, has at least six phage pseudogenes even though it currently lacks a whole prophage [7,8]. Even mitochondria, which have been obligate endosymbionts for over a billion years, possess genes that likely were derived from ancient bacteriophages [9].

The phages of Wolbachia in particular merit closer examination for several reasons: (1) Wolbachia is likely the most widespread endosymbiotic genus on the planet, infecting an estimated 66% of all arthropod species [10] as well as most medically and agriculturally important nematodes [11]. (2) Many Wolbachia strains are rampantly infected with a group of temperate dsDNA bacteriophages named WO [7,12]. (3) Wolbachia exhibit numerous influences on their hosts that ensure their spread as reproductive parasites [13] (see section below on reproductive parasitism), and WO may play a role in these effects[14]. (4) WO phages have several potential applications as tools for understanding endosymbiont evolution and manipulating their biology.

Evolution of WO

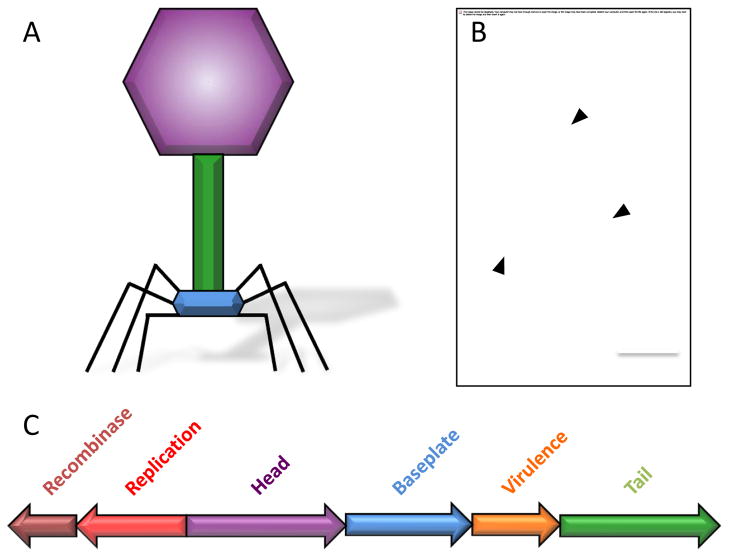

The availability of a large number of sequenced WO phages and Wolbachia genomes has enabled a close examination of WO genome structure and evolution [15]. There are five strains of Wolbachia in which active phage particle production has been demonstrated [12,16–18], each of which contains prophages with complete head, baseplate, and tail gene modules essential for proper phage function (Fig. 2). Interestingly, Wolbachia strains that harbor a complete WO phage usually have additional WO prophages that are degenerate, transcriptionally inactive [19], and, with a few exceptions [5,20], not closely related to other prophages in the same strain [15].

Figure 2.

WO particle and genome structure. (A) Typical appearance of a tailed bacteriophage, color-coded by structural groups. (B) Electron micrograph of WO particles. Examples of phage particles are indicated with arrowheads. Shown is WO isolated from wCauB in the moth Ephestia kuehniella. Photo courtesy of Sarah Bordenstein. (C) The modular genome of prophage WO. Relative portions of the genome dedicated to individual modules and the modules’ orientation and arrangement are shown for lysogenic WOCauB2. Other WO strains have modules in differing arrangements and orientations and some may lack various modules all together. Not all genes are shown.

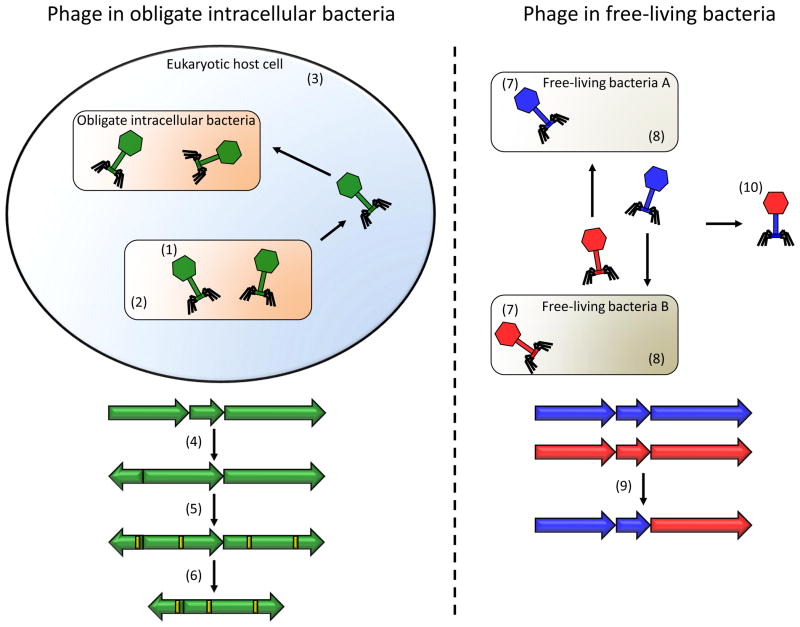

It is commonly understood that dsDNA bacteriophages evolve mainly through frequent horizontal gene transfer of contiguous sets of unrelated genes with a similar function (i.e. tail genes, head genes, lysis genes, etc) between phages in a common gene pool. This tenet is termed the Modular Theory [21]. However, analysis of 16 WO sequences revealed for the first time that, although WO phages are modular, they do not evolve according to the Modular Theory but rather through point mutation, intragenic recombination, deletion, and purifying selection (Fig. 3) [15]. Thus, although WO is prevalent in Wolbachia, its obligate intracellular niche limits the exposure of WO to other phages with which to recombine. Indeed, all evolutionarily recent horizontal transfer events among WO phages are between co-infections of intracellular bacteria in the same eukaryotic host, reflecting the fact that endosymbionts have relatively little interaction with free-living bacteria or their phages (Fig. 3). Examples of these transfers include a 52 kb phage transfer between Wolbachia strains wVitA and wVitB coinfecting the parasitic wasp Nasonia vitripennis [22], and multiple phage transfers between coinfecting Wolbachia strains in natural populations of the leaf beetle Neochlamisus bebbianae [23]. Transfer can also occur between different species of obligate or facultative intracellular bacteria, such as between Wolbachia and a plasmid from a Rickettsia endosymbiont of the tick Ixodes scapularis (Fig. 4) [24].

Figure 3.

Evolution of bacteriophages in endosymbionts and free-living bacteria. Bacteriophages (1) of endosymbionts (2) are restricted in their interactions with other phages due to the barrier of the eukaryotic host membrane (3). Their genomes evolve mainly through recombination (4), point mutation (5), and deletion (6). Bacteriophages (7) of free-living bacteria (8) can more freely interact with each other facilitating modular gene exchange (9) and forming viruses consisting of parts of each parent strain (10). Thus, free-living but not endosymbiont phages evolve by the Modular Theory.

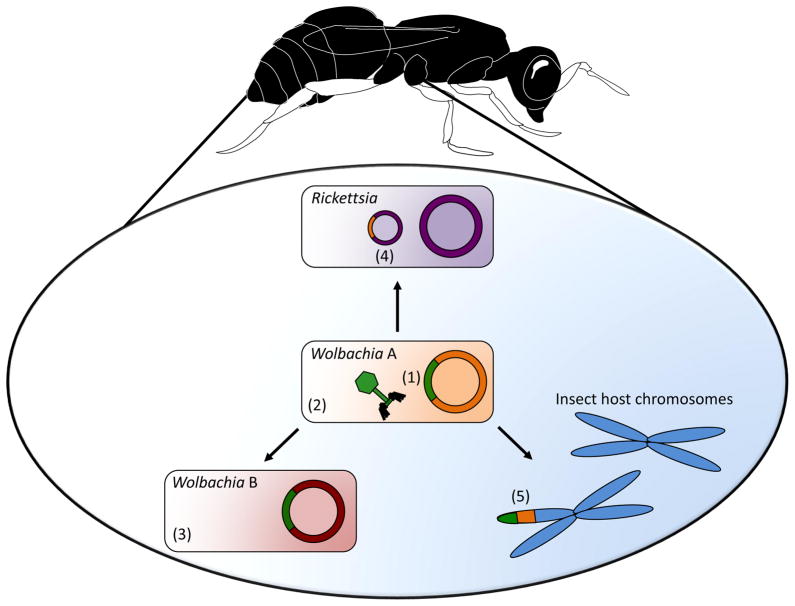

Figure 4.

Examples of gene flow between WO, Wolbachia, and insects. WO prophage sequences (1) have been transferred between coinfections of different Wolbachia strains (2 and 3) on several occasions. Additionally, Wolbachia genes have been transferred to a Rickettsia plasmid (4), and both WO and Wolbachia genes have been found in multiple insect host genomes (5).

In addition to transfer of phages between bacteria, lateral gene transfer of Wolbachia genes into their eukaryotic hosts’ genomes is surprisingly common, with Wolbachia genes found in at least seven insect species and four nematode species [25–28]. These inserts range in size from less than 500bp in Nasonia to nearly the entire Wolbachia genome in Drosophila ananassae [25]. Interestingly, these transfers often include WO prophage regions [25] or sequences adjacent to WO in the Wolbachia genome (Fig. 4) [26]. Given the extensive host range of these endosymbionts, many more as yet undiscovered horizontal transfer events are likely.

Involvement of WO in reproductive parasitism

Perhaps the most tantalizing concept in the study of WO is the idea that WO may influence the biology of not only Wolbachia, but also Wolbachia’s arthropod hosts. Wolbachia have evolved several mechanisms for manipulating their hosts’ reproduction to ensure their spread and maintenance in a population by increasing the evolutionary fitness of Wolbachia-transmitting females [13]. These mechanisms include (1) male killing (male offspring die during embryogenesis), (2) feminization (genetic males develop into fertile females), (3) parthenogenesis (virgin females produce all female broods) and (4) cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), an asymmetrical crossing incompatibility in which offspring of Wolbachia-infected males and uninfected females die during early embryogenesis. The idea that WO could be involved in these manipulations is based on the precedent that bacteriophages commonly encode virulence factors and other genes promoting the fitness of both phage and its host [29]. Even endosymbiont phages may provide such a function. For example, APSE, a phage of Hamiltonella defensa, defends H. defensa’s host, the aphid Aphidius ervi, against parasitic wasps, likely through a phage-encoded toxin of unknown mechanism [30,31]. Additionally, Wolbachia genomes and especially WO prophage regions are replete with ankyrin-repeat proteins [32], a motif known to mediate diverse protein-protein interactions in eukaryotes [33]; thus they could facilitate Wolbachia’s reproductive manipulation of its hosts.

Wolbachia-induced reproductive manipulations are remarkably complex. For example, bidirectional CI blocks the production of offspring between two insects harboring different strains of Wolbachia in some cases but not others [34], leading to several theories for how CI functions. The Lock and Key Model postulates that numerous combinations of modification (mod) factors alter arthropod sperm such that they cannot develop in uninfected eggs, while rescue (resc) factors repair this defect if the egg is infected with a compatible strain of Wolbachia [34,35]. Another theory, the Goalkeeper Model, posits that only two factors exist, but that their concentration or activity level accounts for incompatibility between some strains [36]. In any case, these intricate CI patterns have enabled a search for correlations between strain compatibility and WO, although the results have been somewhat contradictory [12,18,37,38].

One hypothesis is that a WO DNA methyltransferase gene may encode the mod and/or resc factors of CI [37]. This theory fits well with the fact that sperm DNA appears to be modified in the hosts of mod+ Wolbachia strains and that DNA methylation is altered during feminization of the leafhopper species Zyginidia pullula when infected with Wolbachia, although methylation patterns have not yet been investigated in CI [39]. Remarkably, all resc+ group A Wolbachia examined have a WO-encoded met2 methyltransferase gene, whereas resc− Wolbachia do not. However, this correlation does not extend to group B Wolbachia, suggesting that if met2 is the resc factor in group A, it is not universal or its equivalent in group B has not yet been recognized [37]. The met2 gene has been constitutively expressed in Drosophila melanogaster and was unable to cause or rescue CI in wMel-infected flies [40]. Nevertheless, there are several additional genes found in mod+, resc+ strains but not mod−, resc− strains [32], so it remains possible that the WO methyltransferase is involved in CI but requires additional proteins. Examination of transcription of WO genes has shown differential expression of haplotypes of a capsid gene, orf7, between sexes, strains, and life stages of Culex pipiens mosquitoes [18]; however, there has been no obvious correlation between orf7 haplotypes and CI patterns in several species [12,38]. Perhaps most damning to the hypothesis that WO underlies reproductive parasitism is the fact that some Wolbachia strains without WO still manipulate host reproduction [12]. Therefore, if WO genes are directly involved in arthropod reproductive manipulation, it is likely not universal in all strains, but could be part of a larger interplay with other Wolbachia genes and host factors.

Even if WO genes are not directly involved in reproductive manipulations, there is significant evidence that WO indirectly influences CI by controlling Wolbachia densities in the host, a theory termed the Phage Density Model [7]. In wVitA, which infects Nasonia vitripennis and contains active, lytic WO, densities of Wolbachia and WO are inversely related, as are Wolbachia densities and CI severity [16]. Interestingly, altering Wolbachia environmental factors does not abolish this three-way interaction. Introgression to move the wVitA strain from its native host into a related species of wasp, N. giraulti increased Wolbachia load, decreased WO densities, and increased CI [41], while rearing insects at temperature extremes had the opposite effect [42]. In wPip-infected Culex pipiens mosquitoes under conditions where WO is not lytic, this correlation is not seen [43]. These results strongly suggest that lytic WO influences CI by altering Wolbachia densities. Additionally, this interaction is influenced by host factors in a tripartite relationship between WO, Wolbachia, and their insect host.

Applications of WO

One of the greatest limitations in Wolbachia research is the inability to successfully transform these bacteria. Until the Wolbachia genome can be manipulated, it is unlikely that fundamental questions regarding the mechanism of CI and other aspects of Wolbachia biology will be definitively answered. Fortunately, WO offers hope as an avenue for accomplishing this genetic manipulation. Recombinases and attachment sites for WO integration have been identified that could be exploited to this end [44], although there is significant diversity in recombinases and no integration site common to all WO prophages [15]. The large size of the WO genome, diversity of phage sequences, and intracellular lifestyle of Wolbachia are all obstacles to overcome, but development of a WO DNA-delivery vector would be a colossal advance in the study of Wolbachia.

WO also has a potential therapeutic application. Although Wolbachia is a reproductive parasite in most arthropods, in many parasitic nematodes, including those causing filariasis and river blindness in humans, Wolbachia is mutualistic and required for the nematodes’ reproduction [13]. Indeed, elimination of Wolbachia with antibiotic therapies has been successful in treating filarial diseases [45]. WO may encode useful gene products for inhibiting Wolbachia, as phages often express numerous proteins for manipulation and inhibition of their hosts. Potential candidates in WO include lysozymes, which lyse bacterial cell walls [46], and patatins, which have a phospholipase activity [47]. Lysozymes have been identified in two WO phages, while patatins are nearly universal in WO [15]. An understanding of how WO manipulates and lyses Wolbachia may enable development of small molecules with similar functions, or the use of WO’s own proteins as therapeutics if they can be accompanied by an appropriate delivery system [48].

Conclusions

Given the abundance and range of Wolbachia and its phage WO, a firm grasp of the biology in this system will be important for understanding endosymbiont viruses in general and their interactions with their hosts. WO has already tested fundamental questions in evolutionary theory and hinted at fascinating host interactions at multiple levels of symbiotic relationships. Further study of WO and perhaps use of WO as a tool for genetic manipulation will no doubt lead to even more intriguing discoveries in the future.

Highlights.

Viruses are abundant in many endosymbionts despite their intracellular niche

WO, a phage of Wolbachia, is one of the most widespread endosymbiont viruses

The Modular Theory of phage genome evolution does not apply to WO

WO forms a tripartite symbiotic relationship between arthropods, bacteria, and viruses

WO has potential as a vector for Wolbachia transformation and in therapeutics

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Funkhouser for helpful feedback on this manuscript and Robert Brucker for assistance with figures. Preparation of this article was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 GM085163-01 to S.R.B and grant number T32 GM07347 to the Vanderbilt Medical Scientist Training Program).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Taylor M, Mediannikov O, Raoult D, Greub G. Endosymbiotic bacteria associated with nematodes, ticks and amoebae. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2••.Newton IL, Bordenstein SR. Correlations between bacterial ecology and mobile DNA. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62:198–208. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9693-3. Survey of 384 bacterial genomes and their mobile DNA, including phages, showing that mobile DNA abundance correlates with bacterial lifestyles. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bordenstein SR, Reznikoff WS. Mobile DNA in obligate intracellular bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:688–699. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clokie MR, Millard AD, Letarov AV, Heaphy S. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage. 2011;1:31–45. doi: 10.4161/bact.1.1.14942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klasson L, Walker T, Sebaihia M, Sanders MJ, Quail MA, Lord A, Sanders S, Earl J, O’Neill SL, Thomson N, et al. Genome evolution of Wolbachia strain wPip from the Culex pipiens group. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1877–1887. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rupp J, Solbach W, Gieffers J. Prevalence, genetic conservation and transmissibility of the Chlamydia pneumoniae bacteriophage (phiCpn1) FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;273:45–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent BN, Bordenstein SR. Phage WO of Wolbachia: lambda of the endosymbiont world. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster J, Ganatra M, Kamal I, Ware J, Makarova K, Ivanova N, Bhattacharyya A, Kapatral V, Kumar S, Posfai J, et al. The Wolbachia genome of Brugia malayi: endosymbiont evolution within a human pathogenic nematode. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shutt TE, Gray MW. Bacteriophage origins of mitochondrial replication and transcription proteins. Trends Genet. 2006;22:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH. How many species are infected with Wolbachia?--A statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;281:215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandi C, Trees AJ, Brattig NW. Wolbachia in filarial nematodes: evolutionary aspects and implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of filarial diseases. Vet Parasitol. 2001;98:215–238. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(01)00432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavotte L, Henri H, Stouthamer R, Charif D, Charlat S, Bouletreau M, Vavre F. A Survey of the bacteriophage WO in the endosymbiotic bacteria Wolbachia. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:427–435. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:741–751. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pichon S, Bouchon D, Liu C, Chen L, Garrett RA, Greve P. The expression of one ankyrin pk2 allele of the WO prophage is correlated with the Wolbachia feminizing effect in isopods. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.Kent BN, Funkhouser LJ, Setia S, Bordenstein SR. Evolutionary genomics of a temperate bacteriophage in an obligate intracellular bacteria (Wolbachia) PLoS One. 2011;6:e24984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024984. Detailed examination of evolutionary forces and genome structure in sixteen different WO phages. One key result is that the modular theory of phage evolution does not hold in bacteriophage WO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bordenstein SR, Marshall ML, Fry AJ, Kim U, Wernegreen JJ. The tripartite associations between bacteriophage, Wolbachia, and arthropods. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e43. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujii Y, Kubo T, Ishikawa H, Sasaki T. Isolation and characterization of the bacteriophage WO from Wolbachia, an arthropod endosymbiont. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanogo YO, Dobson SL. WO bacteriophage transcription in Wolbachia-infected Culex pipiens. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;36:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biliske JA, Batista PD, Grant CL, Harris HL. The bacteriophage WORiC is the active phage element in wRi of Drosophila simulans and represents a conserved class of WO phages. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:251. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klasson L, Westberg J, Sapountzis P, Naslund K, Lutnaes Y, Darby AC, Veneti Z, Chen L, Braig HR, Garrett R, et al. The mosaic genome structure of the Wolbachia wRi strain infecting Drosophila simulans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5725–5730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810753106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Botstein D. A theory of modular evolution for bacteriophages. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1980;354:484–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb27987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22••.Kent BN, Salichos L, Gibbons JG, Rokas A, Newton IL, Clark ME, Bordenstein SR. Complete bacteriophage transfer in a bacterial endosymbiont (Wolbachia) determined by targeted genome capture. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:209–218. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr007. First application of targeted sequence capture technology to trap and sequence full genomes of Wolbachia and its prophage WO. The study revealed the largest transfer to date of mobile DNA between obligate intracellular bacteria. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chafee ME, Funk DJ, Harrison RG, Bordenstein SR. Lateral phage transfer in obligate intracellular bacteria (wolbachia): verification from natural populations. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:501–505. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishmael N, Dunning Hotopp JC, Ioannidis P, Biber S, Sakamoto J, Siozios S, Nene V, Werren J, Bourtzis K, Bordenstein SR, et al. Extensive genomic diversity of closely related Wolbachia strains. Microbiology. 2009;155:2211–2222. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.027581-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunning Hotopp JC, Clark ME, Oliveira DC, Foster JM, Fischer P, Munoz Torres MC, Giebel JD, Kumar N, Ishmael N, Wang S, et al. Widespread lateral gene transfer from intracellular bacteria to multicellular eukaryotes. Science. 2007;317:1753–1756. doi: 10.1126/science.1142490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klasson L, Kambris Z, Cook PE, Walker T, Sinkins SP. Horizontal gene transfer between Wolbachia and the mosquito Aedes aegypti. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fenn K, Conlon C, Jones M, Quail MA, Holroyd NE, Parkhill J, Blaxter M. Phylogenetic relationships of the Wolbachia of nematodes and arthropods. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e94. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikoh N, Tanaka K, Shibata F, Kondo N, Hizume M, Shimada M, Fukatsu T. Wolbachia genome integrated in an insect chromosome: evolution and fate of laterally transferred endosymbiont genes. Genome Res. 2008;18:272–280. doi: 10.1101/gr.7144908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyd EF, Brussow H. Common themes among bacteriophage-encoded virulence factors and diversity among the bacteriophages involved. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliver KM, Degnan PH, Hunter MS, Moran NA. Bacteriophages encode factors required for protection in a symbiotic mutualism. Science. 2009;325:992–994. doi: 10.1126/science.1174463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Degnan PH, Moran NA. Diverse phage-encoded toxins in a protective insect endosymbiont. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6782–6791. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01285-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Burke GR, Riegler M, O’Neill SL. Distribution, expression, and motif variability of ankyrin domain genes in Wolbachia pipientis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5136–5145. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5136-5145.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Khodor S, Price CT, Kalia A, Abu Kwaik Y. Functional diversity of ankyrin repeats in microbial proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zabalou S, Apostolaki A, Pattas S, Veneti Z, Paraskevopoulos C, Livadaras I, Markakis G, Brissac T, Mercot H, Bourtzis K. Multiple rescue factors within a Wolbachia strain. Genetics. 2008;178:2145–2160. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.086488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poinsot D, Charlat S, Mercot H. On the mechanism of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility: confronting the models with the facts. Bioessays. 2003;25:259–265. doi: 10.1002/bies.10234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36•.Bossan B, Koehncke A, Hammerstein P. A new model and method for understanding Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saridaki A, Sapountzis P, Harris HL, Batista PD, Biliske JA, Pavlikaki H, Oehler S, Savakis C, Braig HR, Bourtzis K. Wolbachia prophage DNA adenine methyltransferase genes in different Drosophila-Wolbachia associations. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanogo YO, Eitam A, Dobson SL. No evidence for bacteriophage WO orf7 correlation with Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in the Culex pipiens complex (Culicidae: Diptera) J Med Entomol. 2005;42:789–794. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/42.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Negri I, Franchini A, Gonella E, Daffonchio D, Mazzoglio PJ, Mandrioli M, Alma A. Unravelling the Wolbachia evolutionary role: the reprogramming of the host genomic imprinting. Proc Biol Sci. 2009;276:2485–2491. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40•.Yamada R, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Brownlie JC, O’Neill SL. Functional test of the influence of Wolbachia genes on cytoplasmic incompatibility expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol Biol. 2011;20:75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01042.x. Drosophila melanogaster expressing twelve different Wolbachia genes were generated and their effect on cytoplasmic incompatibility was tested. Although none of the genes caused or rescued CI, this study was the first use of Wolbachia transgenes in Drosophila to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Chafee ME, Zecher CN, Gourley ML, Schmidt VT, Chen JH, Bordenstein SR, Clark ME, Bordenstein SR. Decoupling of host-symbiont-phage coadaptations following transfer between insect species. Genetics. 2011;187:203–215. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.120675. First study to suggest a host affect on densities of both Wolbachia and WO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bordenstein SR, Bordenstein SR. Temperature affects the tripartite interactions between bacteriophage WO, Wolbachia, and cytoplasmic incompatibility. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker T, Song S, Sinkins SP. Wolbachia in the Culex pipiens group mosquitoes: introgression and superinfection. J Hered. 2009;100:192–196. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esn079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka K, Furukawa S, Nikoh N, Sasaki T, Fukatsu T. Complete WO phage sequences reveal their dynamic evolutionary trajectories and putative functional elements required for integration into the Wolbachia genome. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:5676–5686. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01172-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor MJ, Hoerauf A, Bockarie M. Lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Lancet. 2010;376:1175–1185. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60586-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fischetti VA. Bacteriophage endolysins: a novel anti-infective to control Gram-positive pathogens. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nevalainen TJ, Graham GG, Scott KF. Antibacterial actions of secreted phospholipases A2 Review. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borysowski J, Gorski A. Fusion to cell-penetrating peptides will enable lytic enzymes to kill intracellular bacteria. Med Hypotheses. 2010;74:164–166. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]