Abstract

The immune system is tasked with defending against a myriad of microbial infections, and its response to a given infectious microbe may be strongly influenced by co-infection with another microbe. It has been previously shown that infection of mice with lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV) impairs early adaptive immune responses to Friend virus (FV) co-infection. To investigate the mechanism of this impairment we examined LDV-induced innate immune responses and found LDV- specific induction of IFNα and IFNγ. LDV-induced IFNα had little effect on FV infection or immune responses, but unexpectedly, LDV-induced IFNγ production dampened Th1 adaptive immune responses and enhanced FV infection. Two distinct effects were identified. First, LDV-induced IFNγ signaling indirectly modulated FV- specific CD8+ T cell responses. Second, intrinsic IFNγ signaling in B cells promoted polyclonal B cell activation and enhanced early FV infection, despite promotion of germinal center formation and neutralizing antibody production. Results from this model reveal that IFNγ production can have detrimental impacts on early adaptive immune responses and virus control.

INTRODUCTION

With a few notable exceptions, most scientific investigation of viral pathogenesis and immunology has been performed under highly controlled conditions using single pathogenic agents. However, animals (including humans) in the natural world carry an immunological history of previous infections, and a multiplicity of chronic infections that can have profound consequences on the immune responses to subsequent infections (1, 2). Infection with a particular pathogen reshapes the T cell repertoire in a manner that can either enhance or diminish immune responses to heterologous virus challenges, even when the original infection is completely resolved (2). In situations where viruses persist, the mechanisms used by viruses to evade elimination by the immune system can alter the reactivity to subsequent infectious insults (3). In addition to persistent infections, concomitant infections may also occur, particularly in intravenous drug users who may become simultaneously infected with HIV and hepatitis B or C virus. Thus, it is of interest to study the immunological effects of co-infections, particularly in models where the details of the isolated infections are well understood.

In the current study we investigate co-infection with two mouse viruses, Friend virus (FV) (4), and lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV) (5). FV is an oncogenic retroviral complex consisting of a non-pathogenic, replication competent Friend murine leukemia virus (F-MuLV), and a pathogenic but replication defective virus called spleen focus forming virus (SFFV) (6). Infected mice rapidly develop splenomegaly as a result of proliferation of erythroid progenitors from stimulation of erythropoietin receptors by the gp55 envelope protein of the SFFV component (7). This proliferation leads to lethal FV-induced erythroleukemia unless the mice mount complex immune responses including B cell and CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses (8, 9). LDV is a small, non-pathogenic, RNA virus of the Arteriviridae family (10) that replicates very rapidly in a subset of macrophages involved in scavenging extracellular lactate dehydrogenase. The lysis of these macrophages results in an excess of lactate dehydrogenase in the serum. Immune responses are relatively ineffective against LDV, which establishes life-long persistent infections with little pathological consequence to the host (5).

LDV is endemic in many mouse populations including the laboratory mice used in the early days to propagate FV (11), and FV/LDV co-infections were common in the laboratory infections until recently (12). Previous work demonstrated that co-infection of FV with LDV impaired adaptive immune responses to FV including CD8+ T cell responses (12), CD4+ T cell responses (13), and FV-specific neutralizing antibody responses (14). The current study was initiated to determine the mechanism through which LDV-mediated suppression of FV-specific immune responses occurred.

One possible mechanism by which LDV could induce broad effects on early FV-specific immune responses is by alteration of the cytokine milieu induced by the innate immune response to LDV. We examined cytokine profiles of FV and FV/LDV co-infected mice in a kinetic manner to identify candidate cytokines, and then investigated the effects of LDV-induced cytokines on FV-specific immune responses. Unexpectedly, the key cytokine revealed to be dampening FV-specific B cell and CD8+ T cell responses was IFNγ, a cytokine known to have potent antiviral properties, and that generally promotes the types of immune responses that are suppressed in this scenario.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Mice

Ten to sixteen week old B6.A-Fv2s mice (congenic to C57BL/6 (B6) but carrying the Fv2 susceptibility allele) have been previously described (14) and were used in Figure 1A and B. C57BL/6J (B6) mice were originally obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) and subsequently maintained at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML) or the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) animal facilities. Where indicated, experiments were conducted with 12- to 24-week old female (C57BL/10 × A.BY) F1 mice bred at RML. The relevant FV resistance genotype of these mice is H2b/b, Fv1b/b, Fv2r/s, and Rfv3r/s. B6-backcrossed IFNγ receptor-deficient mice (Ifngr1−/−) maintained at RML and NIMR and B6-backcrossed IFNαβ receptor-deficient mice (Ifnar1−/−) maintained at NIMR have been previously described (15, 16). B6-backcrossed B cell-deficient (Ighm−/−) mice (17) were also maintained at NIMR (Figure 6A) or purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Figure 6B-E). B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were treated in accordance with the regulations and guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of RML, the National Institutes of Health or the UK Home Office regulations and NIMR guidelines.

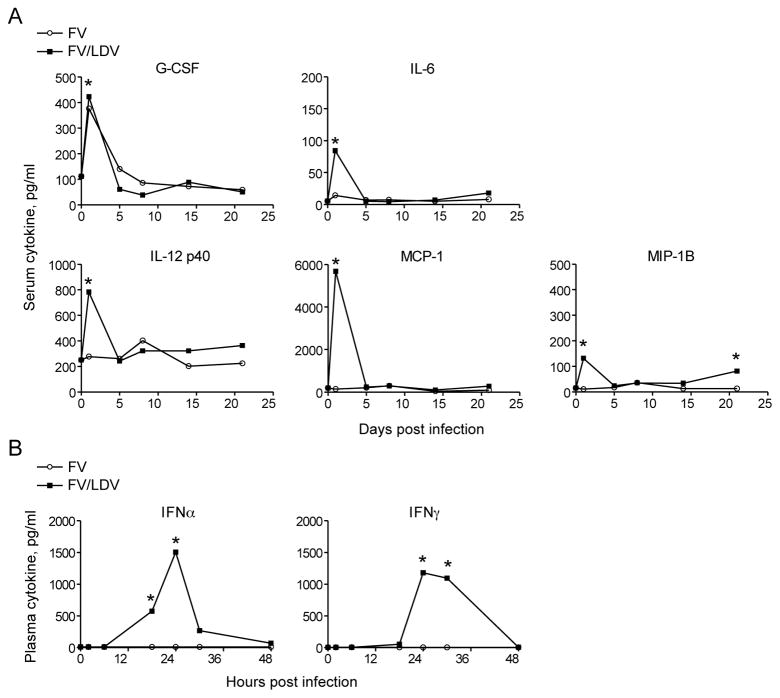

Figure 1. Inflammatory and interferon responses to FV/LDV co-infection, but not to FV infection.

(A) Cytokine and chemokine levels in serum samples of B6.A-Fv2s mice at indicated time points following either FV infection or FV/LDV co-infection. (B) IFNα and IFNγ levels in plasma samples of B6 mice at indicated time points following either FV infection or FV/LDV co-infection. Data are the means of 4–6 mice per group and statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test.

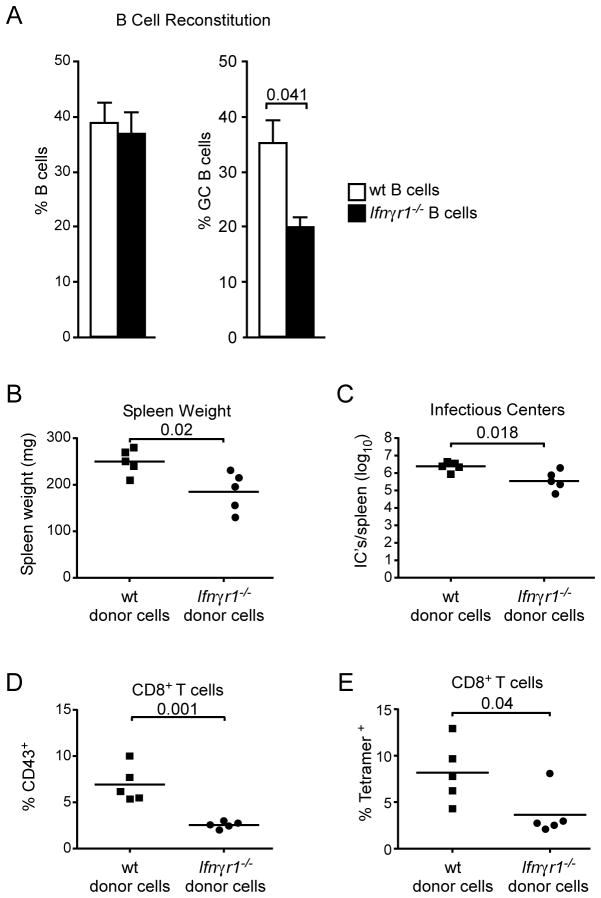

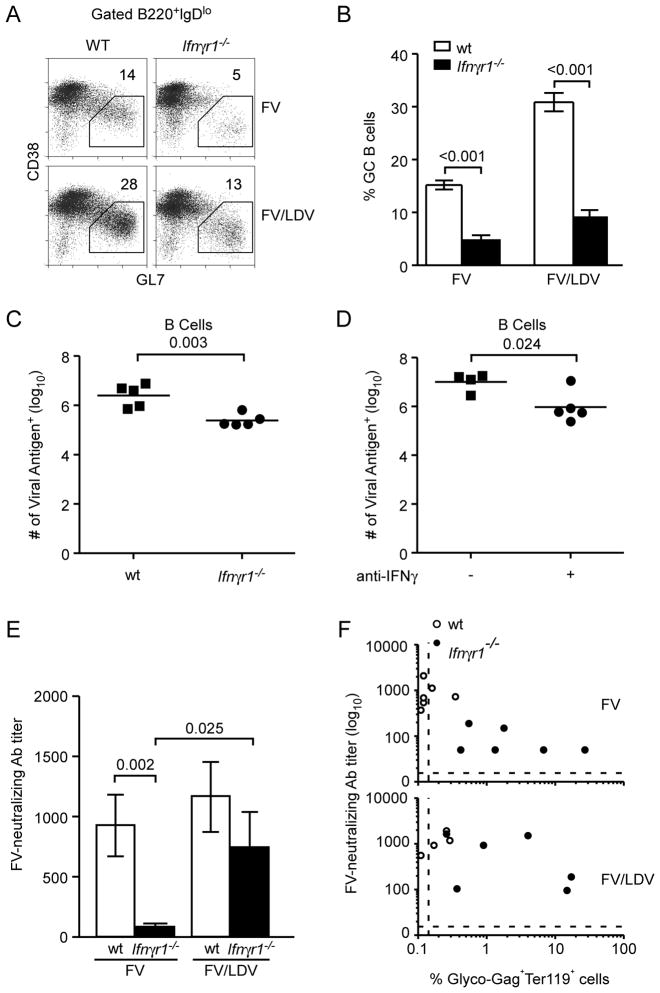

Figure 6. FV replication enhanced by direct IFNγ signaling in B cells.

Non-irradiated B cell-deficient mice were reconstituted with either wt or Ifnγr1−/− bone marrow, resulting in selective B cell reconstitution. The mice were co-infected with FV/LDV 8 weeks post reconstitution. (A) Percentage of B220+ B cells (left) and percentage of CD38lo GL7+ germinal center cells, in gated B220+ IgDlo B cells (right) in the spleens of reconstituted mice 14 days post FV/LDV co-infection. Data are the means ± s.e.m. of 8–12 mice per group and statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test. (B) Spleens from chimeric mice were weighed to determine FV-induced splenomegaly at 14 days post co-infection with FV/LDV. (C) Splenocytes from B were assayed for virus-producing cells by an infectious centers assay. (D) Percentage of activated CD43+ cells first gated on CD8+ T cells from chimeric mice at 14 days post co-infection with FV/LDV. (E) Percentage of CD8+ T cells from splenocytes from D staining with MHC I tetramer (specific for FV glycosylated gag). Data for B-E are representative of 2 independent experiments of 4–5 mice each and statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test.

Viruses and infections

The FV used in this study was a retroviral complex of B-tropic murine leukemia virus (F-MuLV-B) and polycythemia-inducing spleen focus-forming virus (SFFVp). The FV stock was free of LDV and was obtained as previously described (12). A stock of FV (6000 sffu) that additionally contained LDV (105 ID50) was also used (FV/LDV).

Assessment of infection

FV-infected cells were detected by flow cytometry using anti-FV gag mAb 34 bound to secondary goat anti-mouse IgG2b labeled with allophycocyanin (Invitrogen) (18). To determine the number of cells producing infectious virus, serial dilutions of spleen cells were plated onto susceptible Mus dunni cells and co-cultured for 3 days as previously described (18). Cells were fixed with ethanol and incubated sequentially with F-MuLV envelope-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) 720 and peroxidase conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Cappel Laboratories). Foci of infection were identified following incubation with aminoethylcarbazole substrate.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the spleen or bone marrow by mechanical disruption on nylon mesh followed by treatment with ammonium chloride-potassium to lyse erythrocytes. Blood samples were depleted of red cells by incubation in 2% dextran sulfate (1:1 ratio) for 30 min at 37°C prior to treatment with ammonium chloride-potassium. The expression of cell surface markers was analyzed using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to CD4 (clone RM4–5), CD8 (clone 53-6.7), CD11a (2D7), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (clone HL3), CD19 (clone 1D3), NK1.1 (clone PK136), and Ter119 (clone Ter119) (BD PharMingen). FV-specific CD8+ T cells were identified by binding to a DbGagL MHC class I tetramer (Beckman Coulter) as previously described (19). For detection of intracellular IFNγ production, cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS in the presence of 10 μg/ml brefeldin A for 5 hrs. The cells were then stained for surface expression of lineage markers, fixed with 2% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% saponin in PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide and 1% FBS, and incubated with anti-IFNγ (clone XMG1.2) (BD Pharmingen). For detection of Foxp3 expression by intracellular staining, we used the anti-mouse/rat Foxp3 (FJK-16s) and the Foxp3 staining set (eBioscience). For analysis of B cell activation cells were stained with directly conjugated antibodies to B220, CD19, IgD, CD38 and GL7 (eBiosciences). Data were acquired using FACSCalibur, LSRII (BD Biosciences) or CyAn (Dako) flow cytometers, and analyzed with FlowJo v8.7 (Tree Star Inc.) or Summit v4.3 (Dako) analysis software, respectively.

Antibody treatments

B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ mice were depleted of CD8+ T cells by i.p. injection of 100 μg of anti-CD8 (clone 169.4) 7 and 5 days before infection (20). Antibody treatment achieved > 98% depletion as determined by flow cytometric analysis of blood. Neutralization of IFNγ in (C57BL/10 × A.BY) F1 mice was performed by i.p. injection of 250ug of XMG1.2 antibody in 500ul of phosphate-buffered saline at days 0, 2 and 4 post infection. Experiments with control antibodies gave equivalent results as PBS-treatments so PBS treatments were used for most experiments.

Bone marrow chimeras and adoptive transfers

Selective B cell reconstitution in B cell-deficient mice was achieved following bone marrow transplantation of non-irradiated recipients as previously described (21). Briefly, one mouse-equivalent of bone marrow cells from either wt or Ifngr1−/− donor mice was injected into non-irradiated Ighm−/− recipient mice. Chimeras were used at least 8 weeks post bone marrow transfer. For T cell adoptive transfers, spleen cells were isolated from either B6 or B6.Ifngr1−/− mice, and CD8+ cells were separated using the MidiMACS Separation System (MACS) as recommended by the manufacturer (Miltenyi Biotec). A total of 1×107 CD8+ cells in 0.5ml phosphate-buffered balanced salt solution containing 15 U/ml heparin sodium (SoloPak Laboratories) was injected intravenously into B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ congenic mice 1 week post CD8 T cell depletion. Mice were infected with virus 1 day post adoptive transfer.

Cytokine assays

Serum cytokines/chemokines were measured on a Luminex system (Bio-Plex 100) using the mouse cytokine kits (Bioplex Mouse cytokine group II and Bioplex Mouse Cytokine Standard, Bio-Rad Laboratories) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were collected with a minimum of 100 beads per analyte (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-17, eotaxin, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, KC, MCP-1 (MCAF), MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, TNF-α) using Bio-Plex Manager Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). IFNα and IFNγ concentrations in plasma samples were quantified with the Verikine Mouse Interferon-alpha Elisa kit (Pbl interferon) and the mouse IFNγ Femto-HS Elisa kit (eBioscience), respectively, according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

FV-neutralizing antibody assay

Serum titers of FV-neutralizing antibodies were measured as previously described (14). The dilution of serum that resulted in 50% neutralization was taken as the neutralizing titer.

RESULTS

Type I and II IFN responses induced by FV/LDV co-infection but not by FV infection

Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV) is a natural mouse virus that was a common contaminant of Friend retrovirus (FV) stocks that had been maintained by in vivo passage (12). Studies showed that mice infected with FV had delayed antiviral immune responses and diminished virus control when co-infected with LDV (12–14). To determine if differences in cytokine or chemokine responses correlated with the delayed recovery of FV/LDV co-infected mice we used a multiplex assay to measure plasma levels of twenty-three different cytokines and chemokines in a kinetic manner. Experiments in B6.A-Fv2s mice, which carry a non-immunological FV susceptibility gene (14), showed up-regulation of several cytokines, but only G-CSF was induced comparably at early time points in both FV infections and FV/LDV co-infections (Fig. 1A). All the other factors that gave positive results were produced selectively in response to FV/LDV co-infection, and were interferon-inducible. These results suggested that FV/LDV co-infection, but not FV infection, was associated with a strong early interferon response.

To directly quantify the IFN responses mouse plasmas were analyzed by ELISA over a two-day time course following FV infection and FV/LDV co-infection. Rapid and potent induction of IFNα was associated with FV/LDV co-infection but not with FV infection (Fig. 1B, left). These results were consistent with a previous study showing that IFNα responses were due to the presence of LDV (22). Similarly, FV/LDV co-infection, but not FV infection, caused significant release of IFNγ peaking at 24 hrs post-infection (Fig. 1B, right).

Type I IFN responses during FV/LDV co-infection have minimal effect on FV titers

The dramatic difference in type I and II IFN responses between FV infection and FV/LDV co-infection raised the possibility that LDV-induced IFNs may have affected the course of FV infection. To examine the potential impact of IFNs, the course of FV replication was compared between wild type mice and mice lacking signaling through IFN type I or type II receptors.

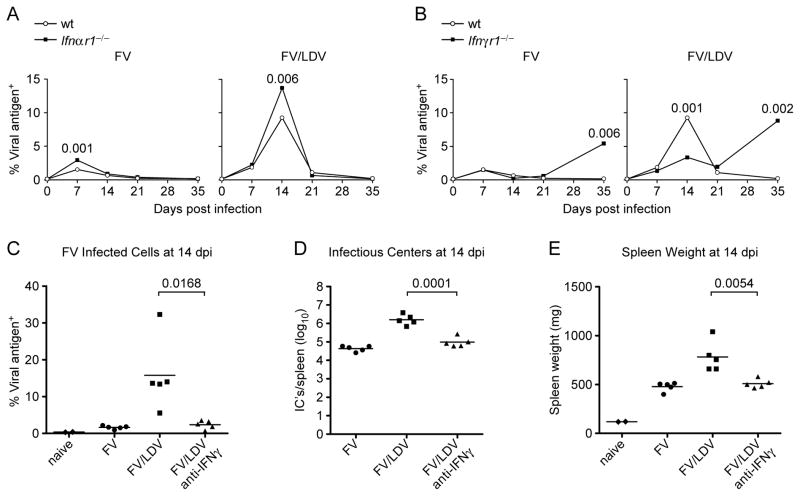

Mice infected with FV had largely recovered from acute infection by 2wpi, whereas co-infection with LDV caused significantly increased peak virus levels and delayed recovery by approximately 1 week (open symbols, Fig. 2A). For both FV infections and FV/LDV co-infections, mice deficient in type 1 IFN signaling (Ifnar1−/−) had slightly increased peak levels of FV infection compared to wt mice, but the kinetics of recovery were very similar to wt and virus control was maintained long-term (Fig. 2A). Thus, the lack of type I IFN signaling caused slightly worse FV infections, but recovery was not significantly affected.

Figure 2. Effect of type I or II IFN response on the course of FV infection.

B6 wild type (wt) mice or B6-congenic Ifnαr1−/− or Ifnγr1−/− mice were infected with FV alone or co-infected with FV/LDV and the course of FV infection was monitored at the indicated time points. (A) Percentage of erthroid (Ter119+) cells expressing FV viral antigen (glyco-Gag, detected by mAb34) in the spleens of wt or Ifnαr1−/− mice. (B) Percentage of erthroid (Ter119+) cells expressing FV viral antigen (glyco-Gag) in the spleens of wt or Ifnγr1−/− mice. Data for A and B are the means of 4–16 mice per group and statistical analysis was performed using non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test. (C) Percentage of erthroid (Ter119+) cells expressing FV viral antigen (glyco-Gag) in the spleens of susceptible (C57BL/10 × A.BY) F1 mice at 14 days post infection with FV or FV/LDV, with or without treatment of anti-IFNγ. (D) Splenocytes from C were assayed for virus-producing cells by an infectious centers assay. (E) Spleens from C were weighed to determine FV-induced splenomegaly. Symbols represent individual mice. Data for C, D and E are representative of 5 independent experiments of 4–6 mice for each group and statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test.

Type II IFN responses during FV/LDV co-infection enhance FV titers

In striking contrast to IFNαβR deficiency, IFNγR (type 2 IFN receptor) deficiency had a significant impact on acute FV replication during FV/LDV co-infection (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, although IFNγ is usually considered to be a potent antiviral cytokine, FV levels were significantly reduced in IFNγR deficient mice compared to wt mice at 14 dpi when acute FV replication was peaking during co-infection with LDV (Fig. 2B). Thus, IFNγ signaling allowed for increased FV titers during acute co-infection. This finding suggested that LDV-specific induction of IFNγ could largely account for increased FV titers during co-infection. In line with previous findings (23), mice lacking IFNγR failed to maintain long-term control of FV infection (Fig. 2B). Thus, IFNγ-signaling appeared detrimental to control of acute infection but critical for control of chronic infection.

To assure that the results from IFNγR-deficient mice were not due to a developmental problem related to genetic inactivation of the Ifngr gene, the effect of blocking IFNγ signaling with anti-IFNγ neutralizing antibodies was tested in susceptible (C57BL/10 x AB.Y) F1 mice co-infected with FV/LDV. IFNγ neutralization during the first week of infection reduced the day 14 FV infection to levels comparable to those seen in mice infected with FV alone as measured by viral antigen positive spleen cells (Fig 2C), virus-producing spleen cells (infectious centers) (Fig. 2D), and FV-induced splenomegaly (Fig 2E). These results confirmed that a major factor contributing to higher FV levels in LDV co-infected mice was LDV induction of the IFNγ response.

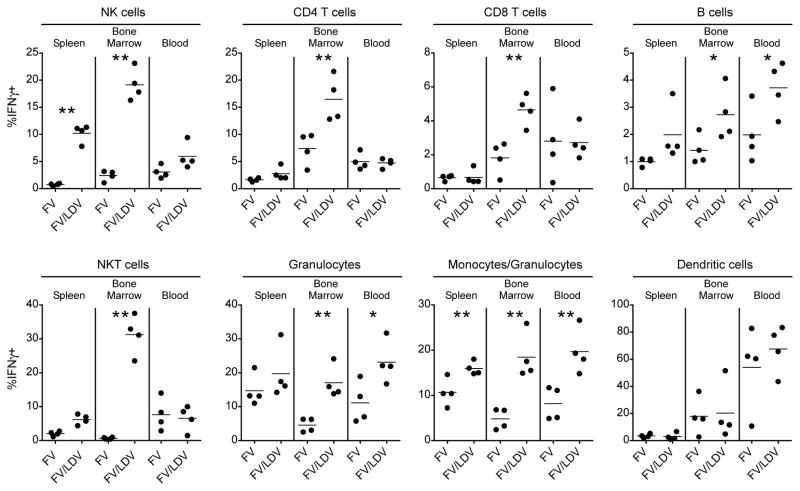

Multiple cell types produce IFNγ in response to FV/LDV co-infection

Intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry were next used to investigate the sources of IFNγ from the major cellular subsets of the spleen, bone marrow and blood at the peak of production (24hrs post-infection). Consistent with the ELISA data, IFNγ was produced predominantly in response to FV/LDV co-infection rather than FV alone (Fig. 3). Multiple cell types responded with strong responses by NK and NKT cells (Fig. 3). The best responses occurred in the bone marrow, an early site of FV replication (24, 25).

Figure 3. IFNγ induction in multiple cell types 24hrs. post-infection with FV/LDV.

IFNγ was measured by intracellular cytokine staining of single-cell suspensions harvested from spleen, bone marrow and blood obtained from susceptible (C57BL/10 × A.BY) F1 mice infected with FV or FV/LDV. Graphs display the percentage of IFNγ+ cells as defined by surface markers: NK1.1 (NK cells), CD4+CD3+ (CD4 helper T cells), CD8+CD3+ (CD8 cytotoxic T cells), B220+ (B cells), NK1.1+CD3+ (NKT cells), Gr1+ (granulocytes), CD11b+ (monocytes/granulocytes), CD11c+ (dendritic cells). Dots represent individual mice. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments of 4 mice for each group and statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test. *<.05, **<.01

IFNγR signaling during acute co-infection is required for CD4 T cell expansion but negatively affects CD8 T cells

Effective control of FV infection is mediated by complex immune responses including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and B cells (26), and it has been shown that co-infection with LDV can negatively impact all three cell types (12–14). We therefore investigated whether LDV-induced IFNγ signaling affected any of these lymphocyte subsets at 14 dpi, the peak of FV/LDV infection. To examine the intensity of the antiviral T cell responses we first analyzed upregulation of the activation-induced isoform of CD43 (clone1B11), which like CD11a (27, 28), has been used to follow virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses (29–32). Virtually all CD43hi CD4+ T cells in FV/LDV co-infection also expressed CD11a and contained a large percentage of recently divided cells (Ki67+) (Fig. 4A). In FV/LDV co-infection the percentage of activated (CD43+) CD4+ T cells was significantly reduced in the absence of IFNγR signaling as illustrated by representative CD43 histograms and mean percentages in bar graph form (Fig. 4B). Thus, IFNγ signaling was necessary for the full activation of CD4+ T cells.

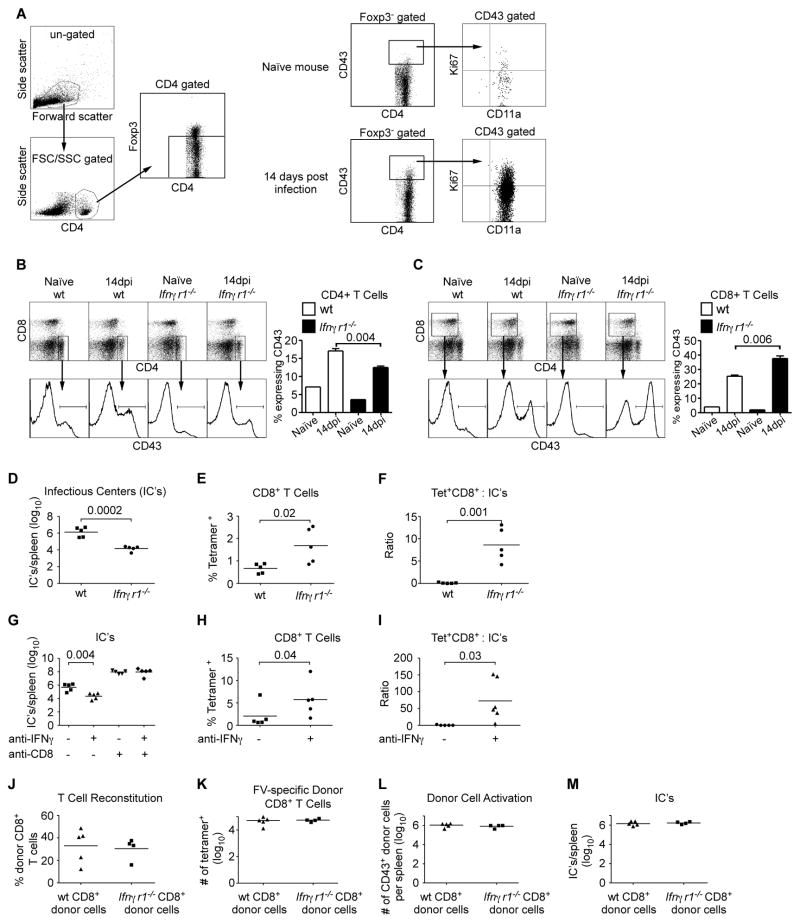

Figure 4. IFNγR signalling during FV/LDV co-infection is required for expansion of CD4+ T cells but it indirectly suppresses expansion of FV-specific CD8+ T cells.

(A) Gating strategy of spleen cells demonstrating that CD43+ (clone 1B11) CD4+ T cells are antigen experienced (CD11a+). Foxp3 positive cells were gated out to remove regulatory T cells, which do not display a naïve phenotype. Bar graphs show the expansion of splenocytes from wt mice (average spleen weight 390mg) and Ifnγr1−/− mice (average spleen weight 224.4mg) that expressed the activation marker, CD43+, at 14 days post co-infection with FV/LDV for (B) CD4+ or (C) CD8+ cells. Data are the means ± s.e.m. of 4–6 mice per group and statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test. (D) Splenocytes from B and C were assayed for virus-producing cells by an infectious centers assay. (E) Percentage of MHC I tetramer positive cells (specific for FV glycosylated gag) first gated on CD8+ T cells. The mean absolute numbers of tetramer positive CD8+ T cells from wt mice was 5.5 × 104/spleen and from Ifnγr1−/− mice was 1.2 × 105/spleen (n=5/group). (F) Ratio of the number of CD8+ MHC I tetramer+ cells divided by the number of virus-producing cells as measured by an infectious centers assay. (G) Splenocytes from (C57BL/10 × A.BY) F1 mice at 14 days post co-infection with FV/LDV, with and without anti-IFNγ and anti-CD8 treatment were assayed for virus-producing cells by an infectious centers assay. (average spleen weight for untreated mice 1211mg, anti-IFNγ treated mice 453mg). (H) Percentage of FV glycosylated gag MHC I tetramer positive cells from (C57BL/10 × A.BY) F1 mice first gated on CD8+ T cells at 14 days post co-infection with FV/LDV, with and without anti-IFNγ treatment. The mean absolute numbers of tetramer positive CD8+ T cells from untreated mice was 1.2 × 106/spleen and from anti-anti-IFNγ treated mice was 3.6 × 106/spleen (n=5–6/group). (I) Ratio of the number of CD8+ MHC I tetramer+ cells divided by the number of virus-producing cells as measured by an infectious centers assay. Wt or Ifnγr1−/− CD8+ T cells were adoptively transferred into congenic Thy1.1 mice and co-infected with FV/LDV for 14 days. (J) Percentage of donor CD8+ T cells (Thy1.2+) from recipient mice co-infected with FV/LDV. (K) The number of donor MHC I tetramer positive cells first gated on donor-specific Thy1.2+ and CD8+. (L) The number of donor cells from J that expressed CD43+CD8+. (M) Splenocytes from J were assayed for virus-producing cells by an infectious centers assay. Symbols represent individual mice. Data are representative of 2–5 independent experiments of 4–6 mice for each group and statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test.

Interestingly, and in contrast to CD4+ T cells, FV infection induced more activation of CD8+ T cells in mice deficient in IFNγR signaling than in wt mice (Fig. 4C). This unexpected increase in CD8+ T cell activation was associated with lower FV infection in IFNγR-deficient mice compared to wt (Fig. 4D). In addition to the overall CD8+ T cell response we also used tetramer staining to analyze the response to the immunodominant FV epitope (19, 33). At 14 dpi the percentage of tetramer positive cells in Ifngr1−/− mice was significantly greater than in wt mice (Fig. 4E). Using absolute numbers of CD8+ tetramer positive T cells and infectious centers from the spleens at 2 weeks post-infection, the effector to target ratios were calculated for wt and Ifngr1−/− mice (Fig. 4F). The Ifngr1−/− mice averaged 100 fold more tetramer positive CD8+ T cells for every infected cell than the wild type mice.

To confirm the results from the Ifngr1−/− mice, we used susceptible (C57BL/10 x AB.Y) F1 mice, and treated them with anti-IFNγ antibodies during FV/LDV co-infection to neutralize the LDV-induced IFNγ response. Anti-IFNγ therapy during the first week of infection reduced FV levels by 100 fold at two weeks post-infection (Fig. 4G), and significantly increased both the proportions of CD8+ tetramer positive T cells (Fig. 4H) and the effector to target ratios (Fig. 4I). CD8+ T cells were shown to be required for the protective effect of anti-IFNγ therapy since the therapy was not successful in CD8-depleted mice (Fig. 4G). Thus while IFNγ signaling appeared necessary for full activation of CD4+ T cells, it hampered the activation of CD8+ T cells in response to FV/LDV co-infection.

To determine if lack of IFN-γ signalling specifically in the CD8+ T cells affected their ability to expand and control virus levels, wild type mice were partially depleted of endogenous CD8+ T cells to make room in the T cell niche, and were then adoptively transferred with either wt or Ifngr1−/− CD8+ T cells prior to infection with FV/LDV. The donor cells were identified by expression of Thy1.2 and IFNγR (data not shown). Interestingly, wt and Ifngr1−/− CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4J), as well as tetramer positive CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4K) expanded to similar levels in response to infection, and also activated to similar levels (Fig. 4L). However, no donor cell-specific differences in virus control were observed (Fig. 4M) suggesting that the inhibitory effect of LDV-induced IFN-γ on CD8+ T cells was indirect.

IFNγR signaling enhances GC B cell formation, polyclonal B cell activation, and FV infection of B cells

Finally we examined the effect of IFNγR deficiency on the B cell response to FV. FV infection drives expansion of B cells with a germinal center (GC) phenotype (B220+IgDloCD38loGL7hi), which is greatly elevated during FV/LDV co-infection due to LDV-induced polyclonal B cell activation (34, 35). Notably, the GC B cell response induced by either FV infection or FV/LDV co-infection was dramatically curtailed in IFNγR-deficient hosts, although FV/LDV co-infection was still able to induce a detectable response (Fig. 5A, B). Thus, IFNγ was a predominant factor in the GC B cell response and polyclonal B cell activation.

Figure 5. IFNγ-dependent B cell activation and antibody response to FV infection.

(A) Flow cytometric example of CD38lo GL7+ germinal center cells, in gated B220+ IgDlo B cells in the spleens of wt or Ifnγr1−/− mice 14 days post either FV infection or FV/LDV co-infection. (B) Percentage of CD38lo GL7+ germinal center cells, in gated B220+ IgDlo B cells in the same mice described in A. Data are the means of 8–10 mice per group and statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test. (C) The number of B cells (B220+) splenocytes that express FV viral antigen (glyco-Gag) on the cell surface from wt and Ifnγr1−/− mice at 14 days post co-infection with FV/LDV. Symbols represent individual mice. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments of 4–5 mice for each group and statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test. (D) The number of B cells (B220+) splenocytes that express FV viral antigen (glyco-Gag) on the cell surface from (C57BL/10 × A.BY) F1 mice at 14 days post co-infection with FV/LDV. Symbols represent individual mice. Data are representative of 5 independent experiments of 4–6 mice for each group and statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test. (E) Titer of FV-neutralizing activity in the sera of FV infected or FV/LDV co-infected wt or Ifnγr1−/− mice at 35 dpi. Data are the means ± s.e.m. of 8–12 mice per group and statistical analysis was performed using non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test. (F) Association between the titer of FV-neutralizing activity and percentage of FV-infected (glyco-Gag) erythroid (Ter119+) cells in the spleens of the same mice described in E. The dashed lines depict the limits of detection.

FV is a type C retrovirus that infects actively dividing cells expressing the ecotropic virus receptor, mCAT-1(36). Next to erythroblasts, which are the primary targets for FV infection, B cells are the most heavily infected cell type (37). Consequently, a reduction in germinal center formation and polyclonal B cell activation due to a lack of IFNγ signaling could have an overall impact on FV infection levels. Indeed the levels of B cell infection in both IFNγR-deficient mice (Fig. 5C) and anti-IFNγ-treated mice (Fig. 5D) were reduced compared to wt or untreated mice, respectively. Thus, lack of IFNγ signaling significantly reduced FV infection in B cells.

The development of virus-neutralizing antibodies, which is dependent on GC B cell responses (38), has been shown to be critical for control of FV infections, especially after the first few weeks (39). Indeed, the defective GC B cell responses in Ifngr1−/− hosts were accompanied by reduced or absent FV-neutralizing antibodies at 5wpi, particularly in FV infections, but also in FV/LDV co-infections (Fig. 5E). This failure to generate virus-neutralizing antibodies was likely responsible for the lack of long-term FV control in Ifngr1−/− hosts (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, a proportion of FV/LDV co-infected, but not FV infected Ifngr1−/− mice produced FV-neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 5E) indicating that the presence of LDV could partially compensate for the lack of IFNγ. However, the presence of FV-neutralizing antibodies in some of the FV/LDV co-infected mice was not associated with protection against high FV titers (Fig. 5F). This finding is consistent with previous results demonstrating that FV-neutralizing antibodies are essential but not sufficient for virus control (8).

The use of Ifngr1−/− mice clearly demonstrated a role for IFNγ in the CG B cell and FV-neutralizing antibody responses. However, given that the CD4+ T cell response depended on IFNγR signaling (Fig. 4B), we examined whether the impaired GC B cell response was due to a B cell-intrinsic effect of IFNγR deficiency or a secondary effect from compromised T cell help. To address this question, we generated bone marrow chimeras by reconstituting non-irradiated B cell-deficient Ighm−/− hosts with either wt or Ifngr1−/− bone marrow. The chimeras were then co-infected with FV/LDV and their germinal center B cell responses were measured at 14 dpi. Whereas the frequencies of total B cells were similar in both types of chimeras (Figure 6A, left), B cell-specific IFNγR deficiency resulted in a significant reduction in the frequency of GC B cells (Fig. 6A, right). Thus, the LDV-induced GC B cell response was dependent on intrinsic IFNγR-signaling in B cells. Furthermore, lack of IFNγR signaling specifically in B cells resulted in reduced FV-induced splenomegaly (Fig. 6B) and infection levels as measured by splenic infectious centers (Fig. 6C).

Lack of intrinsic IFNγR signaling specifically in B cells did not fully recapitulate the phenotype of mice totally deficient in IFNγR. Although the levels of infection were reduced compared to wt, they were still significantly higher than in mice fully deficient in IFNγR signaling (Compare Fig. 4D and 6C). This was likely because mice with IFNγR deficiency solely in B cells did not have the restored CD8+ T cell responses observed in the fully deficient mice. In fact, the CD8+ T cell responses (known to be of host origin as determined by flow cytometric analysis of IFNγR expression, data not shown) in the mice reconstituted with B cells deficient in IFNγR signaling were unexpectedly worse than in mice reconstituted with wt B cells. The frequencies of activated (CD43+) CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6D) and of tetramer positive FV-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6E) were significantly lower in chimeras reconstituted with Ifngr1−/− than with wt B cells. These results indicated that while B cell-specific IFNγR signaling increased FV replication in those cells, the signaling was beneficial for the CD8+ T cell response.

DISCUSSION

Interferons are a diverse family of proteins that are typically induced very rapidly in the innate response to viral infections. In addition to their direct antiviral activity, interferons can also exert important immunomodulatory effects that can either promote or inhibit responses (40, 41). Interestingly, no type I IFN response was detectable from infection with FV only, although LDV elicited a strong and rapid type I IFN response (Fig. 1B). Mice deficient in receptors for type I IFN, and therefore incapable of responding to type I IFN, had slightly elevated peak virus titers, but showed very similar control over FV as wild type mice. Likewise, FV infections did not elicit type II IFN responses but LDV did (Fig. 1B). However, in contrast to the lack of major effects from type I IFN’s, LDV-induced IFNγ produced strong effects on FV-specific adaptive immunity and virus control. Somewhat surprisingly though, the overall effect was not beneficial to the host in the early phase of infection. In fact, our results indicate that LDV-induced IFNγ production is the primary mechanism by which LDV co-infection enhances FV infection. By neutralizing the LDV-induced IFNγ response, either genetically or therapeutically, we could diminish FV titers to levels comparable to those observed in FV-infected mice without LDV co-infection.

While IFNγ is generally considered to promote Th1 responses critical for antiviral immunity, the finding that IFNγ can have inhibitory effects on Th1 adaptive immune responses is not unprecedented. IFNγ has been shown to be capable of down-modulating Th1 responses by promoting T cell apoptosis (42) and inhibiting T cell proliferation in LCMV infection (43). Using the OT-1 model to study CD8+ T cell responses it has further been shown that IFNγ can act to limit CD8+ T cell expansion and promote contraction (44). IFNγ-mediated negative regulation of CD8+ T cells is generally thought to occur through direct effects on the cells, while indirect effects such as increased MHC class I and immunoproteosome expression enhance CD8+ T cell activity (45). However, the current data with CD8+ T cells lacking IFNγR (Fig. 4K, L) suggest that the suppressive effect of IFNγ on FV-specific CD8+ T cells was due to indirect rather than direct effects. Indirect effects are unlikely to come from either CD4+ T helper or regulatory CD4+ T cells because previous studies showed that the acute CD8+ T cell response to FV/LDV infection is not CD4+ T cell dependent, and depletion of CD4+ T cells neither improved nor abrogated the CD8+ T cell response (12). IFNγ-signaling in antigen presenting cells (APC’s), such as CD11b+ cells has been shown to counter-regulate CD8+ T cell expansion (44), but we did not detect IFNγ-associated changes in APC’s comparing untreated mice with mice receiving anti-IFNγ (data not shown). Another APC type that appears to be important in FV infection is the B cell. Interestingly though, lack of IFNγR specifically in B cells was detrimental to the CD8+ T cell response. This suggests that in the context of an IFNγR deficient mouse the B cells are probably not the primary APC, and that another cell type is fulfilling the APC function for CD8+ T cells. Thus, while it is clear that IFNγ inhibits the CD8+ T cell response to FV infection during LDV co-infection, the downstream mediators of that inhibition are not yet known, but do not appear to be from CD4+ T cells or B cells. It has also been shown in vaccinia virus infections that IFNγ deficiency increases CD8+ T cells responses (46). In that situation the increase in CD8+ T cells was attributed to increased virus titers, but a causal relationship was not proven and the increase could have been due to similar effects as seen in our current study.

Our results confirm a critical role for FV-specific CD8+ T cells in the control of acute infection (47). Depletion of CD8+ T cells during acute FV/LDV co-infection raised FV titers in the spleen by two logs10, and the antiviral effect of anti-IFNγ antibody treatment was ablated by depletion of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4). The importance of the CD8+ T cell response in controlling acute FV indicates that the delay of this response by LDV-induced IFNγ was an important factor in the lack of early FV control in co-infected mice. In contrast, IFNγ appeared to be beneficial for the expansion and activation of the CD4+ T cell response indicating that LDV-induced suppression of the CD4+ T cell response (13) occurs through an IFNγ independent mechanism. These results are consistent with a previous study showing that CD4+ T cells were affected by LDV co-infection by an acceleration of the contraction phase of the FV-specific CD4+ T cell response (13).

It was interesting that lack of IFNγ signaling specifically in B cells was sufficient to significantly reduce FV infection levels. Importantly, this reduction occurred even though the FV-specific CD8+ T cell response was not restored in those mice. Thus, the virus titer reduction was not due to an indirect effect on the CD8+ T cells, but appeared to be intrinsic to B cells. We found that IFNγR deficiency specifically in B cells diminished the germinal center response to FV infection as well as the production of FV-neutralizing antibodies. These findings are consistent with an established role for IFNγ and germinal centers in the maturation of B cell responses, especially the IgG2a response to FV as well as other viruses (16, 23, 48, 49). That being said, the virus neutralizing response is known to be very important in control of FV infection, not in promotion of it. The promotion of FV infection was likely due to LDV-induced polyclonal activation of B cells, which was largely, although not wholly, dependent on IFNγ signaling. Since FV is a type C retrovirus that needs actively dividing cells for productive infection, LDV-induced polyclonal activation of B cells provides an additional source of target cells for FV infection and spread. Because B cells are the most heavily infected subset next to erythroblasts (37), the effect on overall infection is significant.

We found that some FV/LDV co-infected Ifngr1−/− mice were able to produce FV-neutralizing antibodies at late stages of infection. The presence of antibody responses in some mice may have been due to the lack of complete dependence on IFNγ signaling for LDV-induced activation of B cells. In fact, it has been reported that LDV-induced hyper-production of polyclonal IgG2a is independent of IFNγ production (50), although our data suggest partial dependence rather than complete independence. Nevertheless, LDV induction of FV-neutralizing antibodies did not correlate with improved FV control, likely because antibody could not compensate long-term for poor CD8+ T cell responses.

Although our results demonstrate that IFNγ can have detrimental effects on a host during an acute viral infection, eventual control of the infection is lost without IFNγ. This was true for both FV infection and FV/LDV co-infections. Although early IFNγ responses in FV/LDV co-infection cause a worse and more prolonged acute infection, most of the mice go on to recover, albeit with chronic infections of both FV and LDV (12). Ultimately then, the IFNγ response must be considered beneficial and determines the difference between recovery from acute infection or succumbing to lethal disease. Thorough understanding of the pleiotropic effects of the IFNγ response in the context of specific infections could allow the development of immunotherapies to maximize both the antiviral and immunomodulatory effects of this potent cytokine in the treatment of life-threatening infections. However, the current study illustrates the importance of understanding the full consequences of IFNγ–mediated effects in the context of an active infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Health, USA, and by the UK Medical Research Council (U117581330).

We are grateful for assistance from the MRC Division of Biological Services and the Flow Cytometry Facilities at our institutes. We thank Anne O’Garra for the Ifnar1−/− mice.

References

- 1.Virgin HW, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Redefining chronic viral infection. Cell. 2009;138:30–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welsh RM, Che JW, Brehm MA, Selin LK. Heterologous immunity between viruses. Immunol Rev. 2010;235:244–266. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oldstone MB. Anatomy of viral persistence. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000523. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friend C. Cell-free transmission in adult Swiss mice of a disease having the character of a leukemia. J Exp Med. 1957;105:307–318. doi: 10.1084/jem.105.4.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plagemann PG, Rowland RR, Even C, Faaberg KS. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus: an ideal persistent virus? Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1995;17:167–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00196164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabat D. Molecular biology of Friend viral erythroleukemia. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1989;148:1–42. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74700-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li JP, D’Andrea AD, Lodish HF, Baltimore D. Activation of cell growth by binding of Friend spleen focus-forming virus gp55 glycoprotein to the erythropoietin receptor. Nature. 1990;343:762–764. doi: 10.1038/343762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasenkrug KJ. Lymphocyte deficiencies increase susceptibility to Friend virus-induced erythroleukemia in Fv-2 genetically resistant mice. J Virol. 1999;73:6468–6473. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6468-6473.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasenkrug KJ, Dittmer U. Immune control and prevention of chronic Friend retrovirus infection. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1544–1551. doi: 10.2741/2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plagemann PG, Moennig V. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus, equine arteritis virus, and simian hemorrhagic fever virus: a new group of positive-strand RNA viruses. Adv Virus Res. 1992;41:99–192. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60036-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riley V. Enzymatic determination of transmissible replicating factors associated with mouse tumors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963;100:762–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson SJ, Ammann CG, Messer RJ, Carmody AB, Myers L, Dittmer U, Nair S, Gerlach N, Evans LH, Cafruny WA, Hasenkrug KJ. Suppression of acute anti-friend virus CD8+ T-cell responses by coinfection with lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus. J Virol. 2008;82:408–418. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01413-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pike R, Filby A, Ploquin MJ, Eksmond U, Marques R, Antunes I, Hasenkrug K, Kassiotis G. Race between retroviral spread and CD4+ T-cell response determines the outcome of acute Friend virus infection. J Virol. 2009;83:11211–11222. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01225-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marques R, Antunes I, Eksmond U, Stoye J, Hasenkrug K, Kassiotis G. B lymphocyte activation by coinfection prevents immune control of friend virus infection. J Immunol. 2008;181:3432–3440. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller U, Steinhoff U, Reis LF, Hemmi S, Pavlovic J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264:1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang S, Hendriks W, Althage A, Hemmi S, Bluethmann H, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-gamma receptor. Science. 1993;259:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.8456301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. A B cell-deficient mouse by targeted disruption of the membrane exon of the immunoglobulin mu chain gene. Nature. 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson MN, Miyazawa M, Mori S, Caughey B, Evans LH, Hayes SF, Chesebro B. Production of monoclonal antibodies reactive with a denatured form of the Friend murine leukemia virus gp70 envelope protein: use in a focal infectivity assay, immunohistochemical studies, electron microscopy and western blotting. Journal of virological methods. 1991;34:255–271. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(91)90105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schepers K, Toebes M, Sotthewes G, Vyth-Dreese FA, Dellemijn TA, Melief CJ, Ossendorp F, Schumacher TN. Differential kinetics of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in the regression of retrovirus-induced sarcomas. J Immunol. 2002;169:3191–3199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cobbold SP, Waldmann H. Therapeutic potential of monovalent monoclonal antibodies. Nature. 1984;308:460–462. doi: 10.1038/308460a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marques R, Williams A, Eksmond U, Wullaert A, Killeen N, Pasparakis M, Kioussis D, Kassiotis G. Generalized immune activation as a direct result of activated CD4+ T cell killing. J Biol. 2009;8:93. doi: 10.1186/jbiol194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ammann CG, Messer RJ, Peterson KE, Hasenkrug KJ. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus induces systemic lymphocyte activation via TLR7-dependent IFNalpha responses by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stromnes IM, Dittmer U, Schumacher TN, Schepers K, Messer RJ, Evans LH, Peterson KE, Race B, Hasenkrug KJ. Temporal effects of gamma interferon deficiency on the course of Friend retrovirus infection in mice. J Virol. 2002;76:2225–2232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2225-2232.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antunes I, Tolaini M, Kissenpfennig A, Iwashiro M, Kuribayashi K, Malissen B, Hasenkrug K, Kassiotis G. Retrovirus-specificity of regulatory T cells is neither present nor required in preventing retrovirus-induced bone marrow immune pathology. Immunity. 2008;29:782–794. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zelinskyy G, Dietze KK, Husecken YP, Schimmer S, Nair S, Werner T, Gibbert K, Kershaw O, Gruber AD, Sparwasser T, Dittmer U. The regulatory T-cell response during acute retroviral infection is locally defined and controls the magnitude and duration of the virus-specific cytotoxic T-cell response. Blood. 2009;114:3199–3207. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasenkrug KJ, Chesebro B. Immunity to retroviral infection: the Friend virus model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7811–7816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrington LE, Galvan M, Baum LG, Altman JD, Ahmed R. Differentiating between memory and effector CD8 T cells by altered expression of cell surface O-glycans. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1241–1246. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masopust D, Murali-Krishna K, Ahmed R. Quantitating the magnitude of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-specific CD8 T-cell response: it is even bigger than we thought. J Virol. 2007;81:2002–2011. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01459-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogan RJ, Usherwood EJ, Zhong W, Roberts AA, Dutton RW, Harmsen AG, Woodland DL. Activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells persist in the lungs following recovery from respiratory virus infections. J Immunol. 2001;166:1813–1822. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dietze KK, Zelinskyy G, Gibbert K, Schimmer S, Francois S, Myers L, Sparwasser T, Hasenkrug KJ, Dittmer U. Transient depletion of regulatory T cells in transgenic mice reactivates virus-specific CD8+ T cells and reduces chronic retroviral set points. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2420–2425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015148108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onami TM, Harrington LE, Williams MA, Galvan M, Larsen CP, Pearson TC, Manjunath N, Baum LG, Pearce BD, Ahmed R. Dynamic regulation of T cell immunity by CD43. J Immunol. 2002;168:6022–6031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dietze KK, Zelinskyy G, Gibbert K, Schimmer S, Francois S, Myers L, Sparwasser T, Hasenkrug KJ, Dittmer U. Transient depletion of regulatory T cells in transgenic mice reactivates virus-specific CD8+ T cells and reduces chronic retroviral set points. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015148108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen W, Qin H, Chesebro B, Cheever MA. Identification of a gag-encoded cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope from FBL-3 leukemia shared by Friend, Moloney, and Rauscher murine leukemia virus-induced tumors. J Virol. 1996;70:7773–7782. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7773-7782.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coutelier JP, Coulie PG, Wauters P, Heremans H, van der Logt JT. In vivo polyclonal B-lymphocyte activation elicited by murine viruses. J Virol. 1990;64:5383–5388. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5383-5388.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coutelier JP, Van Snick J. Isotypically restricted activation of B lymphocytes by lactic dehydrogenase virus. Eur J Immunol. 1985;15:250–255. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830150308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaguchi S, Hasegawa M, Suzuki T, Ikeda H, Aizawa S, Hirokawa K, Kitagawa M. In vivo distribution of receptor for ecotropic murine leukemia virus and binding of envelope protein of Friend Murine leukemia virus. Arch Virol. 2003;148:1175–1184. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dittmer U, Race B, Peterson KE, Stromnes IM, Messer RJ, Hasenkrug KJ. Essential roles for CD8+ T cells and gamma interferon in protection of mice against retrovirus-induced immunosuppression. J Virol. 2002;76:450–454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.450-454.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santiago ML, Benitez RL, Montano M, Hasenkrug KJ, Greene WC. Innate retroviral restriction by Apobec3 promotes antibody affinity maturation in vivo. J Immunol. 2010;185:1114–1123. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chesebro B, Wehrly K. Identification of a non-H-2 gene (Rfv-3) influencing recovery from viremia and leukemia induced by Friend virus complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:425–429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gonzalez-Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E. Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boehm U, Klamp T, Groot M, Howard JC. Cellular responses to interferon-gamma. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:749–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Refaeli Y, Van Parijs L, Alexander SI, Abbas AK. Interferon gamma is required for activation-induced death of T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2002;196:999–1005. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lohman BL, Welsh RM. Apoptotic regulation of T cells and absence of immune deficiency in virus-infected gamma interferon receptor knockout mice. J Virol. 1998;72:7815–7821. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7815-7821.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sercan O, Hammerling GJ, Arnold B, Schuler T. Innate immune cells contribute to the IFN-gamma-dependent regulation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell homeostasis. Journal of immunology. 2006;176:735–739. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitmire JK, Tan JT, Whitton JL. Interferon-gamma acts directly on CD8+ T cells to increase their abundance during virus infection. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1053–1059. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Remakus S, Sigal LJ. Gamma interferon and perforin control the strength, but not the hierarchy, of immunodominance of an antiviral CD8+ T cell response. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:12578–12584. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05334-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zelinskyy G, Myers L, Dietze KK, Gibbert K, Roggendorf M, Liu J, Lu M, Kraft AR, Teichgraber V, Hasenkrug KJ, Dittmer U. Virus-Specific CD8+ T Cells Upregulate Programmed Death-1 Expression during Acute Friend Retrovirus Infection but Are Highly Cytotoxic and Control Virus Replication. J Immunol. 2011;187:3730–3737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Purdy A, Case L, Duvall M, Overstrom-Coleman M, Monnier N, Chervonsky A, Golovkina T. Unique resistance of I/LnJ mice to a retrovirus is due to sustained interferon gamma-dependent production of virus-neutralizing antibodies. J Exp Med. 2003;197:233–243. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schijns VE, Haagmans BL, Rijke EO, Huang S, Aguet M, Horzinek MC. IFN-gamma receptor-deficient mice generate antiviral Th1-characteristic cytokine profiles but altered antibody responses. J Immunol. 1994;153:2029–2037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markine-Goriaynoff D, van der Logt JT, Truyens C, Nguyen TD, Heessen FW, Bigaignon G, Carlier Y, Coutelier JP. IFN-gamma-independent IgG2a production in mice infected with viruses and parasites. Int Immunol. 2000;12:223–230. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]