Summary

Dynamic regulation of calcium-permeable (CP-) AMPARs is important in normal synaptic transmission, plasticity and pathological changes. While the involvement of TARPs in trafficking of calcium-impermeable (CI-) AMPARs has been extensively studied, their role in surface expression and function of CP-AMPARs remains unclear. Here we examined AMPAR-mediated currents in cerebellar stellate cells from stargazer mice, lacking the prototypical TARP stargazin (γ-2). We found a marked increase in the contribution of CP-AMPARs to synaptic responses, indicating that, unlike CI-AMPARs, these can localize at synapses in the absence of γ-2. In contrast with CP-AMPARs in extrasynaptic regions, synaptic CP-AMPARs displayed an unexpectedly low channel conductance and strong block by intracellular spermine, suggesting they were ‘TARPless’. As proof of principle that TARP-association is not an absolute requirement for AMPAR clustering at synapses, mEPSCs mediated by TARPless AMPARs were readily detected in stargazer granule cells following knock down of their only other TARP, γ-7.

Introduction

A majority of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in the CNS is mediated by AMPA-type glutamate receptors (AMPARs). The subunits forming these receptors (GluA1-4) assemble as homo- or hetero-tetramers, the functional properties of which depend on their precise composition 1. In addition to these core subunits, the native receptors contain transmembrane AMPAR regulatory proteins (TARPs; γ-2, γ-3, γ-4, γ-5, γ-7 and γ-8). These accessory subunits play pivotal roles in the neuronal trafficking of AMPARs, promoting their maturation, delivery to the cell surface and accumulation at synapses 2-6. In particular, TARPs can interact, via their C-tail, with PDZ-containing proteins of the postsynaptic scaffold, such as PSD-95. This interaction is generally thought to be crucial for AMPAR synaptic clustering 2,7,8. TARPs also regulate many functional properties of AMPARs, slowing deactivation and desensitization and increasing single-channel conductance 9-16. In addition, TARPs display modulatory actions that are specific to GluA2-lacking calcium-permeable AMPARs (CP-AMPARs). Notably, they attenuate the characteristic voltage-dependent block by endogenous intracellular polyamines and enhance calcium entry 14,17. Because the various TARP isoforms differ in their influence on AMPAR properties and display distinct, yet partially overlapping, patterns of expression in the brain 5,18, this large family of auxiliary subunits adds greatly to the functional diversity of AMPARs in neurons and glia.

Most fast excitatory transmission in the brain is mediated by GluA2-containing calcium-impermeable (CI-) AMPARs. However, it has become apparent that CP-AMPARs are more widespread than originally thought, contributing to normal transmission at numerous synapses 19-21 and playing a key role in several important forms of plasticity 22-26. Furthermore, the disordered regulation of CP-AMPARs is linked to a wide variety of neurological conditions 19,27. Despite their importance in normal and pathological states, the molecular mechanisms that regulate CP-AMPAR trafficking to the neuronal membrane and synaptic clustering remain unclear.

The prototypical TARP, stargazin (γ-2), is intensely expressed in the cerebellum 2,5,18. In the mutant mouse stargazer (stg/stg), which lacks functional stargazin, cerebellar granule cells display a characteristic loss of surface AMPARs 2,28. In the present study, we investigated the effect of the stargazer mutation on the functional expression of AMPARs in cerebellar stellate cells. Like granule cells, these neurons contain both γ-2 and the atypical TARP γ-7 2,5,18,29. Stellate cells are known to contain mRNA for all four AMPAR subunits 30,31 but express a substantial population of CP-AMPARs, which together with CI-AMPARs, contribute to basal transmission and play a critical role in synaptic plasticity 24,25,32,33. Our experiments show that the TARP γ-2 shapes normal excitatory transmission in cerebellar stellate cells by promoting CI-AMPAR clustering and enhancing CP-AMPAR channel-conductance. Importantly, while a significant population of γ-7-associated CP-AMPARs is expressed at the surface of stg/stg stellate cells, our experiments suggest synaptic transmission is mediated mainly by TARPless CP-AMPARs in the absence of γ-2. Confirming the principle, that TARPless AMPARs can localize at synapses, we also found that mEPSCs mediated by AMPARs are readily detected in cerebellar granule cells which lacked TARPs (γ-2 and γ-7).Together, these findings establish that the loss of γ-2 selectively disrupts the synaptic clustering of CI-AMPARs in stellate cells and that functional AMPARs can be expressed at synapses without a TARP.

RESULTS

Increased EPSC rectification in stg/stg stellate cells

To investigate the role of γ-2 in the expression of CP-AMPARs at parallel fiber (PF)-stellate cell synapses, we first recorded evoked synaptic currents (eEPSCs) from stg/stg mice. PF stimulation reliably evoked currents (Fig. 1a), but usually required stimulus intensities higher than those used in slices from control littermates. Thus, even in the absence of γ-2, AMPARs were capable of clustering at PF-stellate cell synapses. In the presence of intracellular spermine (100 μM), which produces a voltage-dependent block of CP-AMPARs14,26,34, eEPSCs displayed I-V relationships that were strongly rectifying (Fig.1b, c). On average, the rectification index (RI, +40/−60 mV; see Methods) was less than half that found in control cells (see Supplementary Table 1). While increased EPSC rectification is likely to reflect an increased CP-/CI-AMPAR ratio, it could also have another possible origin. We have previously shown that polyamine block of CP-AMPARs is attenuated by TARP association14, and that the magnitude of the relief may differ between TARP subtypes4. TARP γ-7 is normally expressed along with γ-2 in stellate cells18,29. In recordings from recombinant receptors expressed in tsA201 cells we found that γ-7 was ~50% less effective than γ-2 at relieving polyamine block of homomeric GluA3 CP-AMPARs (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Therefore, an increase in rectification in stg/stg would be expected if γ-2-containing CP-AMPARs were replaced by γ-7-containing assemblies. However, given the rectification changes in cultured stellate cells, and the blocking action of PhTx (presented below ), we feel this possibility is excluded.

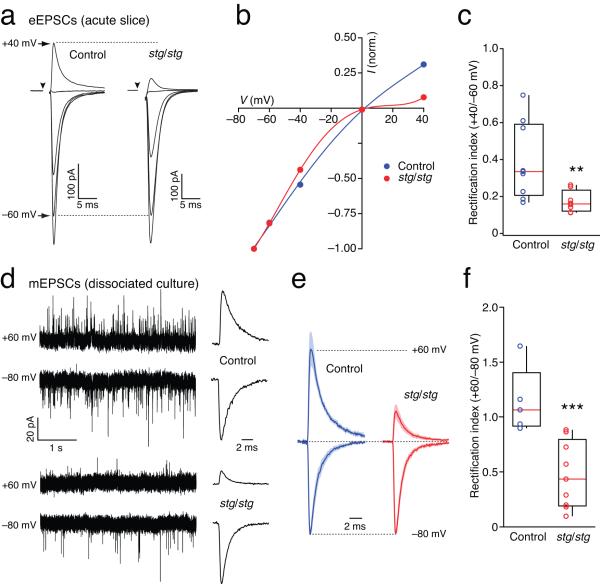

Figure 1.

Loss of γ-2 increases EPSC rectification in stellate cells. (a) AMPAR-mediated eEPSCs are strongly rectifying in stg/stg stellate cells. Representative PF-evoked synaptic currents in two stellate cells in cerebellar slices from a control mouse (left) and a stg/stg mouse (right). Currents are averaged responses at −80, −60, −40, 0 and +40 mV. (b) Corresponding I-V relationships normalized to −80 mV. The fitted curves are fifth-order polynomials. (c) Pooled data showing rectification index values determined as the ratio of synaptic conductance at +40 and −60 mV. Here, and in all figures, the box-and-whisker plots indicate the median value (red line), the 25-75th percentiles (box) and the 10-90th percentiles (whiskers); open circles show individual values. The rectification index is significantly less in stg/stg compared to control stellate cells (n = 8 cells from 5 animals and 9 cells from 4 animals, respectively; ** p < 0.01). (d) Rectification of stg/stg mEPSCs persists in presence of WT innervation. Representative recordings of mEPSCs from cultured stellate cells at −80 and +60 mV. Traces are from a control cell (top) and a stg/stg cell (bottom). Traces to the right show summed mEPSCs from equivalent time periods at the two voltages. (e) Global averages of normalized summed mEPSCs (5 control cells and 9 stg/stg cells from 2 cultures). Shaded areas denote s.e.m. (f) Pooled data showing rectification index values determined as the ratio of summed peak conductance at +60 and −80 mV. Open circles show individual values. The rectification index is significantly less in stg/stg compared to control cells (*** p < 0.001).

It has been shown previously that the relative expression of CI-/CP-AMPARs at stellate cell synapses can be regulated by PF activity24,25,32,33,35. As cerebellar granule cells show a near-complete loss of surface AMPARs in stg/stg mice, the activity-dependent release of glutamate from PFs (granule cell axons) may be decreased in vivo. It could be argued that this, rather than the postsynaptic loss of γ-2, caused the observed increase in stellate cell EPSC rectification. We therefore asked whether the increased EPSC rectification remained when stg/stg stellate cells were innervated by normal, γ-2-containing, granule cells. We examined dissociated cultures of cerebellar neurons prepared from stg/stg-GAD65-GFP mice or their control littermates. In these cultures stellate cells express GFP and can thus be identified among granule cells36. Neurons were isolated from P7 mice, a developmental stage at which PF-stellate cell synapses contain mainly CP-AMPARs14. To provide stg/stg stellate cells with normal excitatory input, both ‘control’ and ‘stg/stg’ cultures were seeded with a large excess of wild-type granule cells. After 7-9 days in vitro, under conditions that promote synaptic maturation (see Methods), mEPSCs from control cells displayed linear I-V relationships, suggesting a developmental shift to CI-AMPARs. By contrast mEPSCs recorded from stg/stg stellate cells displayed marked inward rectification (Fig.1c-e). This result strongly suggests that the altered rectification observed in stg/stg stellate cells in slices is indeed cell-autonomous. Moreover, these results argue strongly against the simple replacement of γ-2-containing CP-AMPARs by γ-7-containing CP-AMPARs. mEPSCs from control cells in culture displayed I-V relationships that were linear. As TARPs confer only a partial relief of polyamine block 4,14, such linear responses can arise only from CI-AMPARs. Thus, the difference between control and stg/stg stellate cells in culture is caused mainly by an altered CP-/CI-AMPAR ratio. These results from cultured stellate cells suggest that γ-2 plays a key role in the expression of CI-AMPARs at synapses.

Reduced qEPSC amplitude in stg/stg cells

We next recorded synaptic currents from stellate cells in slices in the presence of strontium (see Methods). In these conditions, PF stimulation evoked asynchronous transmitter release, resulting in isolated quantal EPSCs (qEPSCs) that were readily identified, both in control and stg/stg cells (Fig. 2a-d). This allowed us to examine postsynaptic changes in isolation from possible presynaptic effects of the stargazer mutation37, and to measure synaptic currents without contamination by glutamate spillover onto surrounding extrasynaptic AMPARs38. To analyze the distribution of qEPSC amplitudes we excluded any overlapping events that appeared to arise from the release of more than one quantum.

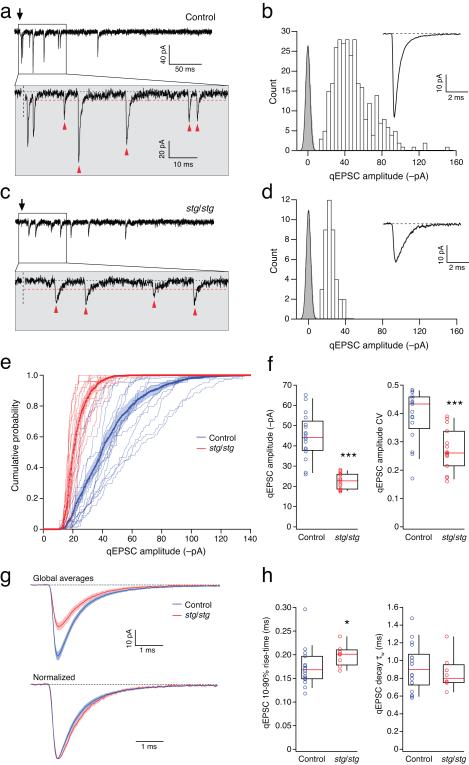

Figure 2.

Amplitude and kinetic properties of qEPSCs in control and stg/stg stellate cells. (a) Representative qEPSCs evoked in a control stellate cell by PF stimulation (arrow) in the presence of 5 mM SrCl2. The period immediately following stimulation is enlarged in the lower panel. Synaptic events occurring >10 ms after stimulation, and exceeding the detection threshold (red dashed line), are indicated by arrowheads. (b) Amplitude distribution (open bars) of all selected events from the same cell as a. Background variance is indicated by the baseline all-point amplitude distribution (grey bars) fitted with a Gaussian. The inset shows the average qEPSC. (c and d) Same as a, for qEPSCs evoked in a stg/stg stellate cell. (e) Cumulative probability distributions for qEPSC amplitudes in control (blue) and stg/stg stellate cells (red). The averaged distributions are shown in bold with filled areas representing s.e.m. (f) Pooled data for qEPSC amplitudes and their coefficients of variation (CV) (n = 17 and 15 cells, from 14 and 13 animals; both *** p < 0.001). (g) Superimposed global mean control and stg/stg qEPSCs; shaded areas denote s.e.m. (h) Pooled data for rise-time and decay measures (n = 18 and 8; * p < 0.05).

In control cells, individual qEPSCs displayed a wide range of amplitudes (typically up to 150 pA, at −80 mV) (Fig. 2a-b). By contrast, in stg/stg stellate cells, qEPSCs showed much less variation, with events typically less than 50 pA (Fig. 2c-d). Importantly, the amplitude distributions were clearly distinct from the background noise (Fig. 2b,d), indicating that small events were adequately resolved. Across cells, the amplitude distributions from stg/stg cells were consistently narrower than those from control cells (Fig. 2e), with a reduced coefficient of variation (CV) (Fig. 2f). Although the average amplitude of qEPSCs was markedly reduced in stg/stg stellate cells (Fig. 2f,g), the kinetic parameters were altered only slightly, with a small but significant increase in rise time and no change in decay time (Fig. 2g,h) (see Supplementary Table 1).

Increased prevalence of CP-AMPARs at stg/stg synapses

Consistent with the inward rectification of control eEPSCs, the peak conductance of qEPSCs recorded in control cells at +60 mV was significantly less than that at −80 mV (−35%; Fig. 3a,c). In addition, there was a visible reduction in the frequency of qEPSCs at positive potentials (Fig. 3d). In stg/stg cells, the peak conductance of qEPSCs was not significantly different at positive and negative potentials (Fig. 3b,c), but the decrease of qEPSC frequency at positive potentials was much greater than seen in control (Fig. 3d) (see Suplementary Table 1).

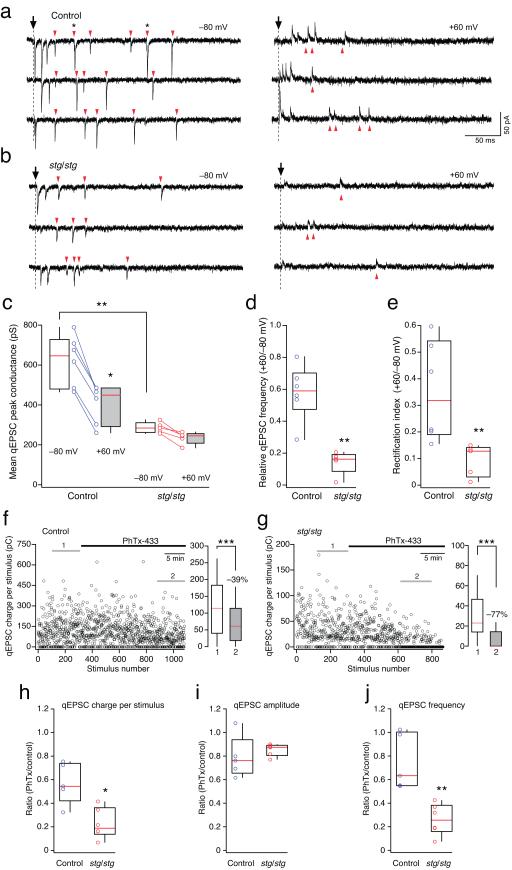

Figure 3.

Enhanced block by intracellular spermine and extracellular PhTx-433 of PF-evoked qEPSCs in stg/stg stellate cells. (a) qEPSCs recorded at −80 mV (left) and +60 mV (right) from a control stellate cell. Arrowheads indicate events occurring >10 ms after stimulation, and exceeding the detection threshold. Asterisks in the upper sweep denote events arising from apparent superimposition of two qEPSCs. (b) Equivalent traces recorded from a representative stg/stg stellate cell. (c) Pooled data showing voltage-dependent changes in qEPSC peak conductance in control and stg/stg stellate cells. Note the much smaller conductance at −80 mV of stg/stg compared to control qEPSCs (n = 6 and 5 cells, from 5 animals each; ** p < 0.01) and the significantly reduced conductance at +60 mV in control cells (n = 5; * p < 0.05). (d) Pooled data showing the greater depolarization-induced reduction in qEPSC frequency in stg/stg stellate cells (**p < 0.01). (e) Pooled data showing rectification index (see Methods). Note the significantly increased rectification in stg/stg stellate cells (** p < 0.01). (f) Time course of the effect of bath-applied PhTx-433 (10 μM) on qEPSC charge per PF stimulus in a representative control stellate cell. On the right, box-and-whisker plots of the charge transfer measured over time periods 1 and 2 (left, grey lines) before and after PhTx-433 application (*** p < 0.0001). (g) Time course of PhTx-433 action in a representative stg/stg stellate cell. Note the large fraction of failures in time period 2 and its dramatic effect on the qEPSC charge transfer per stimulus, right panel (*** p < 0.0001). (h-j) Pooled data showing the effect in control and stg/stg stellate cells of PhTx-433 on qEPSC charge per stimulus (n = 5 cells from 4 animals and 6 cells from 5 animals, respectively; * p < 0.05), qEPSC peak amplitude, and qEPSC frequency (** p < 0.01).

The reduced frequency of qEPSCs at +60 mV could arise if some events were suppressed by intracellular polyamine block. Alternatively, events might be less readily detected due to the lower driving force. We therefore made additional recordings with spermine-free intracellular solution. In these conditions qEPSC frequency was similar at positive and negative potentials (the relative frequencies at +60 versus −80 mV were 1.13 ± 0.07 in control and 1.12 in stg/stg, n = 4 and 2, respectively). Importantly, the background noise was similar at the two voltages: the standard deviation of the baseline current in control cells (see Methods) was 2.8 ± 0.3 pA at −80 mV versus 3.2 ± 0.4 pA at +60 mV (n = 6). Corresponding values for stg/stg stellate cells were 2.4 ± 0.1 pA and 2.7 ± 0.21 pA (n = 5). Thus, the reduction in qEPSC frequency at +60 mV appears dependent on the presence of intracellular spermine, suggesting that some qEPSCs are mediated mainly (or solely) by CP-AMPARs.

If CP- and CI-AMPARs occurred in similar relative proportions at all synapses within a cell, the qEPSCs detected at +60 mV would arise from those synapses that generate the largest events at −80 mV. Thus, the rectification measured from such events would match the average rectification measured from eEPSCs. However, our experiments suggested that this is not the case, as the rectification calculated using all events detected at +60 mV and a matching number of the largest events at −80 mV (see Methods) was considerably less than the rectification of eEPSCs and showed no difference between stg/stg and control (see Supplementary Table 1). This suggests that there are populations of synapses in both control and stg/stg stellate cells with different sensitivity to polyamines. However, synapses containing strongly rectifying CP-AMPARs are prevalent in stg/stg stellate cells, with a large proportion of synapses failing to generate any detectable current at +60 mV.

To estimate the relative proportion of CP-AMPARs across synapses we calculated the rectification index as the ratio of summed qEPSC peak conductances from equal numbers of sweeps at +60 mV and −80 mV. This method takes into account the full range of possible rectification at individual synapses, including those where no currents could be detected at +60 mV due to complete block by spermine (rectification index of 0). We found that the rectification index in stg/stg stellate cells was reduced to one quarter of that seen in control cells (Fig. 3e) (see Supplementary Table 1). These rectification values were comparable to the rectification measurements from eEPSCs, and confirmed an increased expression of CP-AMPARs at PF synapses in stg/stg stellate cells.

We reasoned that if the proportion of qEPSCs mediated by CP-AMPARs is greater in stg/stg stellate cells, qEPSCs should display a greater sensitivity to the selective CP-AMPAR antagonist philanthotoxin-433 (PhTx-433) 39. We therefore monitored qEPSCs (evoked at 0.5 Hz, −80 mV) while applying PhTx-433 (10 μM). The use-dependent blocker produced a progressive reduction in the synaptic charge transfer per stimulus, reaching a plateau after approximately 10 minutes. The effect was most pronounced in stg/stg stellate cells (Fig. 3f-h), with a noticeable increase in the number of stimuli that failed to produce any detectable currents (Fig. 3g). While PhTx-433 reduced the mean qEPSC amplitude equally in stg/stg and control cells (Fig. 3i), the effect on qEPSC frequency was significantly greater in stg/stg cells (Fig. 3j) (see Supplementary Table 1). This latter observation mirrors that seen with the voltage-dependent block by intracellular spermine. Thus, most qEPSCs in stg/stg stellate cells are mediated by CP-AMPARs, consistent with the view that synaptic expression of CI-AMPARs is selectively disrupted.

Low-conductance TARPless CP-AMPARs at stg/stg synapses

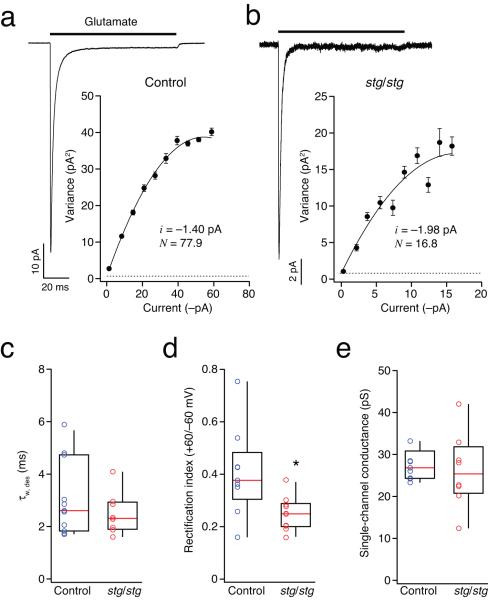

qEPSCs in stg/stg stellate cells were, on average, half the size of those recorded in control cells, while the whole-cell conductance evoked by bath-applied glutamate (100 μM) was roughly a quarter of the control value (Supplementary Fig. 2). Such reduction in AMPAR-mediated currents could arise from a decrease in AMPAR surface expression, a change in the single-channel conductance, or a modification in channel gating properties. To determine the conductance properties of synaptic AMPAR channels, we performed peak-scaled non-stationary fluctuation analysis on qEPSCs (ps-NSFA; see Methods) (Fig. 4a-d).

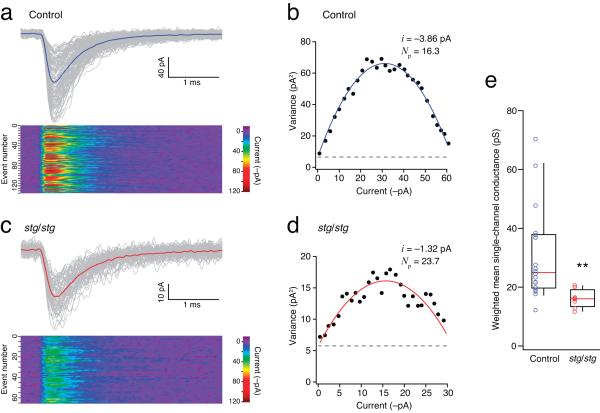

Figure 4.

Single-channel conductance of synaptic AMPARs is reduced in stg/stg stellate cells. (a) PF-evoked qEPSCs recorded in a representative control stellate cell at −80mV. Individual events (thin grey traces) were aligned at their 10% rise time and averaged (thick blue line). The lower panel is a color-coded image of all events. (b) Corresponding current-variance relationship. The dashed line indicates the background current variance. The weighted-mean unitary current (i) and the number of channels open at the peak (Np) were estimated from the parabolic fit. (c and d) As for a and b, but for a representative stg/stg stellate cell. Note the typically smaller qEPSC amplitude. (e) Pooled data showing the reduced single-channel conductance in stg/stg stellate cells (n = 18 cells from 16 animals and 8 cells from 7 animals; ** p < 0.01).

Synaptic AMPARs in stg/stg stellate cells displayed weighted mean conductance values ~50% lower than those in control cells (Fig. 4e). This was unexpected; our experiments indicated that these synapses contain mainly CP-AMPARs, and thus the receptors would be predicted to exhibit a high single-channel conductance14,40,41. Notably, the decrease in channel conductance matched almost exactly the reduction we observed in qEPSCs peak amplitude (Fig. 2f, g) (see Supplementary Table 1). As γ-2 does not affect the peak open probability of AMPARs4,14, our results suggest that the number of receptors activated by a quantum of transmitter is similar at stg/stg and control stellate synapses, despite the striking differences in mean qEPSC amplitudes. The low single-channel conductance, and high sensitivity to block by internal spermine (at +60 mV), of synaptic AMPARs in stg/stg stellate cells suggests that, in the absence of γ-2, TARPless CP-AMPARs reach the membrane and cluster at synapses.

Extrasynaptic γ-7-associated CP-AMPARs in stg/stg cells

As AMPARs diffuse within the neuronal membrane, and are continuously exchanged between synaptic and extrasynaptic sites7,42, one might expect that extrasynaptic CP-AMPARs in stg/stg stellate cells would also lack an associated TARP. To investigate this, and determine the properties of extrasynaptic AMPARs, we used ultrafast application of glutamate onto somatic outside-out patches (10 mM, 100 ms; see Methods). Glutamate-evoked macroscopic currents were kinetically similar in stg/stg and control cells (Fig. 5a-c), with peak currents that displayed marked inward rectification (+60/−60 mV) (Fig. 5d). As at synaptic sites, rectification was greatest in patches from stg/stg stellate cells. Of note, the rectification in somatic patches from control mice was indicative of the presence of a significant population of extrasynaptic CP-AMPARs. This finding differs from earlier studies, which suggested that extrasynaptic AMPARs in stellate cells were calcium-impermeable 24,25. This is probably because these earlier studies did not use the NMDAR antagonist d-AP5 to limit elevation of the intracellular calcium concentration during slicing. NMDAR activation is known to increase GluA2 expression in stellate cells 43 and is therefore likely to increase basal expression of extrasynaptic CI-AMPARs.

Figure 5.

Extrasynaptic AMPARs in stg/stg stellate cells exhibit increased rectification and large single-channel conductance. (a) Representative averaged current evoked by ultrafast application of 10 mM glutamate (100 ms) to an outside-out somatic patch (−60 mV) excised from a stellate cell in slices from a control mouse. Inset shows corresponding current-variance plot. Symbols denote mean variance in each of ten equally spaced amplitude bins. Vertical error bars denote s.e.m. The weighted-mean single-channel current (i) and the number of channels in the patch (N) are calculated from a weighted parabolic fit to the data. (b) As for a, but from a stg/stg stellate cell. (c) Pooled data showing the similar desensitization time course (τw, des) of the currents from control and stg/stg stellate cells (n = 11 cells from 9 animals and 8 cells from 6 animals). (d) Pooled data showing the greater rectification of extrasynaptic AMPARs in stg/stg stellate cells (n = 9 and 10 cells, from 7 animals each; * p < 0.05). Rectification index was calculated as the ratio of mean peak current amplitudes at +60 and −60 mV. (e) Pooled data showing the large single-channel conductance determined in both control and stg/stg stellate cells (n = 9 and 8 cells, from 7 and 5 animals).

Having established that CP-AMPARs are prevalent in extrasynaptic patches of both control and stg/stg stellate cells, we next applied NSFA to somatic currents to determine if these displayed properties of TARPed or TARPless receptors. The estimated weighted mean single-channel conductance of the extrasynaptic AMPARs was similarly high in stg/stg and control cells (27.5 ± 1.2 pS and 26.2 ± 3.2 pS, respectively; n = 9 and 8) (Fig. 5e), consistent with the view that extrasynaptic CP-AMPARs are TARPed in stg/stg cells. However, these conductance values are lower than those that we obtained with γ-2- or γ-7-associated recombinant CP-AMPARs (see Supplementary Table 2). This likely reflects the presence of multiple AMPAR subtypes (CP- and CI-AMPARs) in the extrasynaptic membrane of both stg/stg and control stellate cells. To address this issue, and provide direct evidence as to whether TARPed CP-AMPARs were indeed present extrasynaptically, we next turned to single-channel analysis.

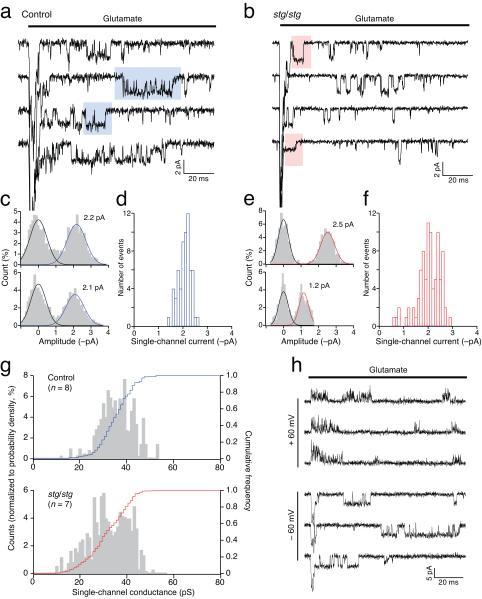

In both control and stg/stg patches, we resolved single-channel events following the initial glutamate-evoked macroscopic current (Fig. 6a-g). We reasoned that, even if a variety of AMPARs were present, the most readily detectable events would be those mediated by large conductance CP-AMPARs, which should be unambiguously distinguished by their susceptibility to block by intracellular spermine. Indeed, while clear single-channel currents were observed at −60 mV, only brief, flickery openings were seen at +60mV, consistent with a voltage-dependent channel block (Fig. 6h). In control cells, chord conductances of single-channel events at −60 mV ranged from 11.5 – 52.7 pS, with an average of 35.2 ± 1.8 pS (n = 8) (Fig. 6a-c, g). In stg/stg cells, the corresponding values were 9.1 – 56.7 pS, with an average of 31.6 ± 2.2 pS (n = 7) (Fig. 6d-g) (see Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 6.

Direct resolution of AMPAR channel events in outside-out somatic patches from control and stg/stg stellate cells. (a) Representative records showing resolved channel events in the tail of macroscopic responses (truncated) to rapid application of 1 mM glutamate. Responses were obtained at −60 mV and, for illustration, are filtered at 2 kHz. (b) Same as a but for a patch from a stg/stg stellate cell. (c) Representative all-point amplitude histograms, from the selected segments shown in the blue boxes in a, fitted with two Gaussian components, giving current estimates of 2.2 and 2.1 pA. Analysis was performed on records filtered at 4 kHz. (d) Pooled data for the same patch as a, showing the distribution of current amplitudes for 63 selected events in 273 sweeps. (e, f) Same as c and d, but from the stg/stg stellate cell patch shown in a (85 events in 174 sweeps). Individual histograms are from the selected segments shown in the red boxes. (g) Histograms and cumulative distributions of pooled data (n = 8 cells from 6 control animals and 7 cells from 6 stg/stg animals). Note that both control and stg/stg patches exhibit large conductance events. (h) Representative records from a stg/stg patch, showing prolonged large conductance openings at −60 mV but only brief flickering events at +60 mV, consistent with partial block by intracellular spermine of CP-AMPARs (records filtered at 4 kHz).

The large openings recorded in stg/stg stellate cells almost certainly arise from γ-7-associated CP-AMPARs. Our experiments on recombinant receptors confirmed that γ-7 enhances the conductance of CP-AMPARs to the same extent as γ-2 (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Ref. 4). Importantly, only TARPed CP-AMPARs displayed openings larger than 40 pS (see Supplementary Fig. 1b). Such large channel events were recorded in 6 out of 7 stg/stg patches, suggesting that TARPed CP-AMPARs contribute significantly to extrasynaptic currents. Furthermore, most extrasynaptic CP-AMPARs in stg/stg cells would appear to be TARPed, as average single-channel conductances were similar in control and stg/stg patches (Supplementary Table 2),

The mean conductance of directly resolved single-channels in control stellate cells (27.6 ± 1.3 pS; n = 8) was ~30% higher than our estimate obtained from NSFA in the same patches (p = 0.008). Although not statistically significant, a similar trend was apparent in patches from stg/stg cells (25.9 ± 3.6 pS; n = 7, p = 0.078). Importantly, when applied to homogenous populations of recombinant CP-AMPARs in heterologous cells (both TARPed and TARPless), these two methods of analysis yielded very similar conductance estimates (Supplementary Table 3). It is thus likely that the lower estimate obtained with NSFA in stellate cell patches reflects a small proportion of low-conductance CI-AMPARs that contributed to the weighted-mean conductance but were not resolved during selection of single-channel events (Fig. 6a, d). Our experiments suggest that, like control stellate cells, stg/stg cells express mostly TARPed CP-AMPARs in their extrasynaptic membrane, together with some CI-AMPARs. The increased rectification we observed in stg/stg patches, is consistent with view that CP-AMPARs are co-assembled with γ-7, which is less effective than γ-2 at relieving polyamine block (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

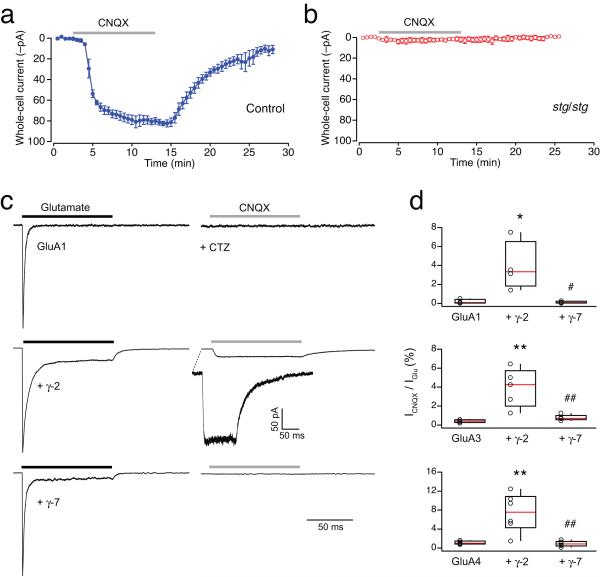

As CNQX has been shown to act as a partial agonist on TARP-associated AMPARs44, we sought to confirm the presence of such AMPARs in the plasma membrane of stg/stg stellate cells by recording CNQX-evoked responses. As expected, bath application of CNQX evoked clear inward currents in control cells (Fig. 7a). By contrast, CNQX failed to produce a current in stg/stg cells (Fig. 7b). This would seem to be inconsistent with the idea that extrasynaptic AMPARs are associated with a TARP. However, the action of CNQX on γ-7-associated AMPARs is not known. We therefore considered whether this TARP might differ from conventional ones (γ-2, γ-3, γ-4 and γ-8) in its ability to confer partial agonist activity on CNQX. We transfected tsA201 cells with AMPAR subunits (GluA1, GluA3 or GluA4) alone, and with γ-2 or γ-7, and compared responses activated by fast application of glutamate or CNQX to outside-out membrane patches. While glutamate produced large currents in each case, CNQX produced detectable currents only in those cells expressing γ-2 (Fig. 7c, d), providing a clear functional distinction between γ-7 and other TARPs. Together, the large single-channel conductance of CP-AMPARs in stg/stg somatic patches, their strong block by internal spermine, and their failure to respond to CNQX, all support the view that extrasynaptic AMPARs in stg/stg stellate cells are predominantly calcium permeable and associated specifically with γ-7.

Figure 7.

CNQX is not a partial agonist for CP-AMPARs containing TARP γ-7. (a) Bath application of 10 μM CNQX in the presence of 100 μM cyclothiazide (CTZ) (grey bar) evoked a whole-cell current in control stellate cells. Plot shows the time course of the response (−80 mV). Symbols represent the averaged whole-cell current from 3 cells (from 2 animals) and the error bars denote the s.e.m. (b) stg/stg stellate cells did not respond to CNQX (n = 3 cells from 2 animals). (c) Normalized representative currents evoked by ultrafast application of 1 mM glutamate (black bar), and 10 μM CNQX (grey bar; in presence of 100 μM CTZ), from somatic outside-out patches excised from tsA201 cells transfected with GluA1 alone (upper traces), GluA1 and γ-2 (middle traces) or GluA1 and γ-7 (lower traces). Note that CNQX evoked a detectable current only from the cell co-expressing GluA1 with γ-2. (d) Pooled data showing ratio of the peak amplitude of the currents (%) evoked by CNQX and glutamate for GluA1, GluA3 and GluA4, alone and with γ-2 or γ-7. For each GluA subunit, there was a significant difference between groups (one-way ANOVA), with the fractional CNQX-evoked current significantly larger with γ-2 than with the GluA subunit alone (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01) or with γ-7 (# p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01) (Tukey HSD multiple comparison of means).

TARPless AMPARs mediate mEPSCs in stg/stg granule cells

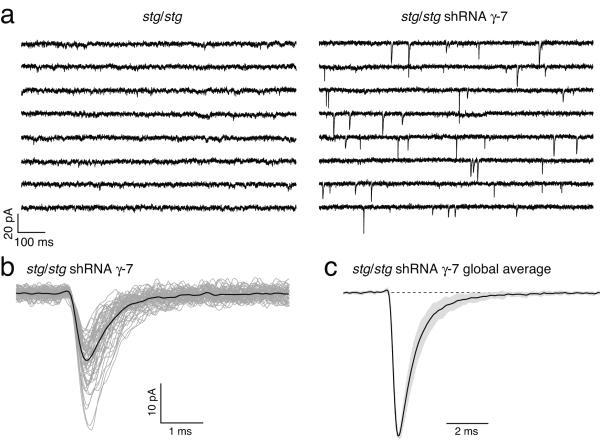

The results described so far suggest that while γ-7-associated CP-AMPARs are expressed at the surface of stg/stg stellate cells, synaptic currents are mediated by channels displaying properties characteristic of TARPless CP-AMPARs. However, this interpretation is based on correlative evidence. We therefore next sought to test more directly the principle that TARP-association is not an absolute requirement for AMPAR localization at synapses by acutely disrupting γ-7 expression. Because stellate cells occur at relatively low density in culture, making it difficult to demonstrate TARP knockdown biochemically, we turned to cerebellar granule cells – the neurons in which the critical importance of TARPs in synaptic transmission was first revealed. Like stellate cells, granule cells express only γ-2 and γ-72,5,29 (see also Fig. 3 of 18) and in stg/stg mice lack synaptic currents2,28.

We reasoned that if TARPless AMPARs are capable of reaching synapses, the absence of mEPSCs in stg/stg granule cells must be due to endogenous γ-7 interfering with this process. In which case, knockdown of γ-7 should make TARPless AMPARs available for synaptic clustering. We transfected stg/stg granule cells with shRNA against γ-7 (see Methods), and compared these with untransfected cells. As expected, no mEPSCs were detected in the control untransfected stg/stg granule cells (Fig. 8a). By contrast, mEPSCs (arising at granule cell-granule cell synapses) were readily detected in >90% of treated cells (Fig. 8a-d), occurring at an average frequency of 2.0 ± 0.5 Hz (n = 25 cells). These results confirm the principle that TARPless AMPARs can cluster at stg/stg synapses.

Figure 8.

shRNA knockdown of TARP γ-7 rescues synaptic transmission in stg/stg granule cells. (a) Representative whole-cell recordings (eight consecutive 1 s sweeps) from an untransfected stg/stg granule cell (left) and a stg/stg granule cell treated with shRNA against γ-7 (right). Recordings were obtained at −60 mV in the presence of 0.5 μM TTX. mEPSCs were seen in 0/5 granule cells from 1 stg/stg culture but in 25/27 cells from 2 shRNA treated cultures. (b) Superimposed mEPSCs (grey) and average record (black) for the shRNA-treated cell shown in a. (c) Scaled global average mEPSC from 14 shRNA-treated cells in which average mEPSCs were obtained from >20 events (21–406). Grey fill denotes s.e.m. The mean amplitude of the averaged mEPSCs was 11.6 ± 0.8 pA.

Discussion

We found that TARPs differentially control the expression of CP- and CI-AMPARs in cerebellar stellate cells. Our experiments show that γ-2 plays a pivotal role in efficient expression of CI-AMPARs at PF synapses, but is not essential for accumulation of CP-AMPARs at these sites. Furthermore, it enhances AMPAR channel conductance, attenuates block of CP-AMPARs by internal polyamines and promotes normal synaptic clustering of γ-7-associated AMPARs 29. We found that CP-AMPARs associate with the atypical TARP γ-7 at the surface of stg/stg stellate cells. Unexpectedly, these assemblies fail to accumulate at synapses, and instead, synaptic transmission in stg/stg stellate cells appears to be mediated by TARPless CP-AMPARs. We confirmed the ability of AMPARs to accumulate at synapses in the absence of TARPs by showing rescue of synaptic transmission in stg/stg granule cells following knockdown of TARP γ-7.

Loss of γ-2 increases prevalence of synaptic CP-AMPARs

We found a marked increase in the rectification, and an enhanced block by PhTx-433, of EPSCs in stellate cells from stg/stg mice, indicating an increased prevalence of synaptic CP-AMPARs. Our data from cultured stellate cells suggest that this change in AMPAR subtype is cell-autonomous, and results directly from the loss of postsynaptic γ-2. Observations in other cerebellar neurons are consistent with our interpretation of the role of γ-2 in stellate cells.

Like stellate cells, Golgi cells receive excitatory input from granule cells, and express γ-2 and γ-7 18,29. Additionally, they express γ-3 2,18 – a TARP closely related to γ-2. While I-V relationships for eEPSCs are linear in control Golgi cells, and remain so in γ-3 knockout and stg/stg mice, they become inwardly rectifying in the absence of both TARPs 45, supporting the view that γ-2 (or the closely related TARP γ-3) is required for the efficient expression of CI-AMPARs, but not CP-AMPARs. In fact, it seems to be the inability of cerebellar granule cells to express CP-AMPARs that results in the loss of synaptic currents in stg/stg animals (D.S., M.F. and S.G.C-C., unpublished observations).

Low-conductance CP-AMPARs underlie EPSCs in stg/stg cells

As well as being implicated in virtually every stage of AMPAR trafficking, including biosynthesis, surface delivery and synaptic clustering, TARPs remain co-assembled with surface AMPARs and determine many of their key functional properties. It is therefore unexpected that AMPARs appear to be TARPless at stg/stg PF-stellate cell synapses. Our evidence in support of this view comes from both rectification index and single-channel conductance measurements. Although the desensitization and deactivation rates of recombinant AMPARs are typically decreased by the presence of a TARP 10,15, we found no difference in qEPSCs kinetics between stg/stg and control. This is perhaps not surprising, as the kinetics of synaptic currents depend not only on intrinsic AMPAR properties but also on the waveform of glutamate in the synaptic cleft 46. As synaptic maturation is likely affected by the absence of γ-2, and the subsequent deficit in brain-derived neurotrophic factor in stg/stg cerebellum 47,48, an altered glutamate concentration waveform may obscure any change in qEPSCs decay associated with a change or loss of TARP. Indeed, we found that the rise time of qEPSCs was slightly but significantly slowed in stg/stg stellate cells. However, both rectification index and single-channel conductance measurements are independent of the glutamate waveform, and thus reliably characterize functional changes in synaptic AMPARs. Regarding AMPAR channel conductance, our experiments in heterologous cells demonstrate that γ-2- and γ-7-associated CP-AMPARs display similarly high single-channel conductances. Our recordings of qEPSCs at stg/stg synapses show that they are mediated by channels that have a low conductance and are strongly rectifying – a combination of properties unique to TARPless CP-AMPARs.

The reduction in glutamate-evoked whole-cell current in stg/stg stellate cells was greater than expected from the observed decrease in single-channel conductance of synaptic receptors; it is thus likely to reflect a reduced density of extrasynaptic AMPARs, as well as a decrease in the number of functional synapses. The latter would be consistent with our need to employ higher intensity PF stimulation to evoke EPSCs in stg/stg stellate cells. Despite this overall reduction in surface expression, the number of synaptic AMPARs activated during a qEPSC was remarkably similar at stg/stg and control synapses. Surprisingly, therefore, our experiments suggest that AMPARs will accumulate at ‘normal’ density at some synapses even in the absence of an associated TARP. The retention of TARPless CP-AMPARs at synapses in stg/stg stellate cells suggests that these are binding directly to postsynaptic PDZ-containing proteins. Indeed, there is good evidence that the C-tail PDZ-binding motif of GluA3 interacts directly with the anchoring protein GRIP, and the clustering of a fraction of CP-AMPARs at PF-stellate cell synapses is thought to depend on this specific interaction 24,35.

Exclusion of γ-7-associated AMPARs from stg/stg synapses

In stg/stg stellate cells, a large proportion of extrasynaptic AMPARs exhibit a high single-channel conductance, similar to that seen with recombinant TARPed CP-AMPARs. As no TARP other than γ-2 or γ-7 is found in WT stellate cells, and as the other main AMPAR accessory proteins – the cornichons – appear not to associate with surface AMPARs in cerebellar neurons 49, it is highly likely that extrasynaptic CP-AMPARs are co-assembled with γ-7 in stg/stg stellate cells. This view is supported by our data showing their strong block by intracellular spermine and the absence of CNQX partial agonism. Nevertheless, our data also suggest that TARPless AMPARs are expressed at synapses. The presence of both γ-7-associated- and TARPless AMPARs at the surface of stg/stg stellate cells must reflect some selectivity in TARP association. Indeed, such regulated assembly is indicated by the minimal co-immunoprecipitation of γ-7 and γ-2 in cerebellar extracts from WT mice 3.

TARP γ-7 has been shown to cluster at PF-stellate cell synapses, where it interacts directly with PSD-95 3,29. However, our experiments suggest that this is unlikely to be the case in the absence of γ-2. In agreement with this interpretation, western blot analysis revealed a pronounced reduction of γ-7 in the postsynaptic density fraction from the cerebellum of γ-2 knockout mice 29. Further, quantitative analysis of postembedding immunogold labeling from these mice shows a ~70% reduction in γ-7 across PF synapses onto stellate, basket and Golgi cells (M. Yamasaki and M. Watanabe, personal communication). The loss at PF-stellate cell synapses is potentially even greater, as the remaining γ-7 immunoreactivity likely reflects its presence at synapses onto γ-3-containing Golgi cells. Additional studies also support our proposal that γ-7 does not efficiently accumulate at synapse in the absence of γ-2. Cerebellar granule cells are severely affected by the lack of γ-2, displaying no clear synaptic currents and only residual whole-cell currents 3. Overexpression of γ-7, while promoting surface expression of AMPARs, does not rescue synaptic currents 3,12. In fact, our experiments showing the rescue of synaptic currents in stg/stg cerebellar granule cells by γ-7 knockdown suggest that γ-7-associated AMPARs may be excluded from the postsynaptic membrane in these cells.

While our manuscript was in revision, a paper describing AMPAR-mediated currents in stg/stg stellate cells was published 50. Although this study focused on synaptic plasticity, it also described increased AMPAR rectification at both synaptic and extrasynaptic sites. However, as the authors did not observe any increase in PhTx-433 sensitivity, they concluded that the increase in rectification was unlikely to be the result of a change in GluA2 content, and that stg/stg mice do not display a specific defect in GluA2 trafficking. These conclusions are in marked contrast with our finding of a clear increase in the prevalence of CP-AMPARs at stg/stg synapses. While the reason for such a difference is unclear, our experiments also show that, a change in CP-AMPAR properties contributes to the observed increase in rectification (at both synaptic and extrasynaptic sites). Importantly, by identifying a differential distribution of low- and high-conductance CP-AMPARs in stg/stg stellate cells we have been able to reveal the presence of TARPless and γ-7-associated CP-AMPARs at synaptic and extrasynaptic sites respectively, both of which are more effectively blocked by spermine than are γ-2-associated CP-AMPARs.

In conclusion, our data show that the loss of γ-2 in stg/stg stellate cells induces quantitative and qualitative changes in synaptic transmission that cannot be compensated for by the remaining TARP γ-7. While our results extend the idea that TARPs interact with specific AMPAR subtypes, display distinct patterns of expression in the neuronal membrane, and differentially modify AMPAR functional properties, they challenge the view that TARPs are essential for the expression of functional AMPARs at synapses.

Methods

Animals

Stargazer mice were bred from +/stg animals (with a C57BL/6 background) and categorized according to phenotype: stg/stg (smaller size, head tossing, unsteady gait) and control. To enable identification of GABAergic stellate cells in dissociated cerebellar cultures, these were prepared from stg/stg-GAD65-GFP or control littermate mice36,51. Cultures were from individual postnatal day 7 (P7) animals, and tail samples were used for stg/stg genotyping to enable culture identification52. All procedures for the care and treatment of mice were in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Cerebellar slices

Recordings were made in coronal slices (200 μm) cut from the cerebellarvermis of animals aged between P18 and P31. The slicing solution contained 85 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 4 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 64 mM sucrose and 25 mM glucose (pH 7.3 when bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2). To prevent NMDAR-mediated cell damage, we included 20 μM d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP5, Tocris Bioscience). Slices were viewed using a fixed stage upright microscope (Zeiss Axioskop FS or Olympus BX51 WI with DIC-IR or oblique illumination) and recordings (23-26 °C) were made from visually identified interneurons in the outer third of the molecular layer – presumptive stellate cells.

The extracellular solution contained 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4 and 25 mM glucose (pH 7.3 when bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2). To block NMDA and GABAA receptors, 20 μM d-AP5 and 20 μM SR-95531 (Ascent Scientific) were added. Pipettes for whole-cell and outside-out patch recording were pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass (1.5 mm o.d., 0.86 mm i.d., Harvard Apparatus), coated with Sylgard resin (Dow Corning 184) and fire-polished to a final resistance of ~5 or ~7 MΩ, respectively. The ‘internal’ solution contained 128 mM CsCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, 10 mM TEACl, 2 mM MgATP, 1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM NaCl, plus 1 mM N-(2,6-dimethylphenylcarbamoylmethyl) triethylammonium bromide (QX314) and 0.1 mM spermine tetrahydrochloride (both Tocris Bioscience) (pH 7.4 with CsOH). Currents were recorded at 22–24 °C using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, filtered at 5 kHz and digitized at 20 or 50 kHz (pClamp10 and Digidata 1440A; Molecular Devices). Series resistance (12–20 MΩ) and input capacitance (2.5–6.5 pF) were read directly from the amplifier settings used to minimize the current responses to 5 mV hyperpolarizing voltage steps. Series resistance was typically compensated by 60-85%.

Dissociated cultures

Dissociated cultures containing cerebellar stellate cells were prepared from P7 stg/stg-GAD65-GFP mice or their control littermates. Cells were plated on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips together with a 10-fold excess of cerebellar neurons dissociated from wild type C57BL/6 mice. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C (5% CO2) in Basal Medium Eagle (BME; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FCS; vol/vol, Gibco), 100 mg ml−1 gentamicin, 2 mM l-glutamine. Cells were maintained in ‘high K+’ (35 mM KCl) which promotes synaptic maturation by increasing intracellular concentrations of Ca2+. Cytosine arabinoside (10 μM) was applied 24h after plating and recordings were made from GFP-expressing interneurons after 7-9 days. The ‘external’ solution contained 145 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.3 with NaOH). Input capacitance was 5–11 pF and series resistance (15–43 MΩ) was typically compensated by 60%.

For granule cell recordings, dissociated cultures were prepared from P6 or P8 stg/stg mice or their control littermates. After 4 days in vitro, cells were transfected, using the calcium phosphate method, with a mixture of four shRNA expression constructs against TARP γ-7 (GeneCopoeia MSH037278-mU6; 2 μg per coverslip). The target sequences were; mouse γ-7 (Accession No. NM 133189.3) 54 (5′-CTGCGGCCTGCTCCTTGTG-3′), 176 (5′-GGAGAGTCTGCTTCTTTGC-3′), 374 (5′-CTCAGAGGACCATTCTTGC-3′) and 500 (5′-CTGAGCAGTACTTTCACTA-3′). The constructs contained the mCherryFP reporter gene. Recordings were made from un-transfected and transfected (red fluorescent) cells 3-4 days after shRNA application. Input capacitance was 3–7 pF. Series resistance (11–30 MΩ) was not compensated.

EPSC analysis

In slices, EPSCs were evoked by PF stimulation using a thin-walled glass electrode filled with external solution placed on the molecular layer (20–80 V, 20–40 μs, 0.5 Hz). Evoked EPSCS (eEPSCs) were aligned on the stimulus and averaged (Igor Pro 6.10 WaveMetrics Inc. with NeuroMatic 2.02, http://www.neuromatic.thinkrandom.com). The rectification index (RI) was calculated by dividing the peak conductance at +40 mV by that at −60 mV. In slices, quantal EPSCs (qEPSCs) were evoked in a recording solution in which Ca2+ was replaced with Sr2+ (5 mM SrCl2). Events were detected using amplitude threshold crossing 53, with the threshold (typically ~7 pA) set according to the baseline current variance. To avoid multiquantal events, only qEPSCs occurring >10 ms after the PF stimulus were included (total sweep length 360 ms). When analyzing event frequency or charge transfer, any event with a distinct peak was included. For qEPSC amplitude, all events with a monotonic rise were included, irrespective of overlapping decays. Finally, for ps-NSFA (see below) and kinetic analysis only events with a monotonic rise and uncontaminated decay were included, and aligned on their rising phase prior to averaging. In cultured stellate cells, mEPSCs were recorded at −80 and +60 mV in the presence of 500 nM tetrodotoxin (TTX; Tocris Bioscience). In cultured granule cells, mEPSCs were recorded at −60 mV. To increase mEPSC frequency, in both cases cells were briefly exposed (2 min) to 200 μM LaCl3 54.

Peak-scaled non-stationary fluctuation analysis

ps-NSFA was used to estimate the weighted mean single-channel conductance of synaptic receptors 55. Each qEPSC was divided into 30 bins of equal amplitude and, within each bin, the variance of the qEPSC about the scaled average was computed. The variance was plotted against the mean current value, and the weighted mean single-channel current was estimated by fitting the full parabolic relationship with the equation:

| (1) |

where σ2PS is the peak-scaled variance, Ī is the mean current, i is the weighted mean single-channel current, Np is the number of channels open at the peak of the EPSC, and σ2B is the background variance. The mean chord conductance for each cell was calculated assuming a reversal of 0 mV (no correction was made for liquid-junction potentials).

Excised somatic patches

Outside-out patches were excised from the soma of identified stellate cells. Currents were filtered at 10 kHz and digitized at 50 kHz. Ultra-fast application of glutamate was achieved using an application tool made from theta glass (2 mm o.d.; Hilgenberg GmbH) pulled to a tip opening of ~200 μm, and moved by a piezoelectric translator (Physik Instrumente) mounted on a PatchStar micromanipulator (Scientifica) 4. To determine channel properties from macroscopic responses, glutamate (10 mM) was applied (100-ms duration, 1 Hz) and the ensemble variance of all successive pairs of current responses calculated. The single-channel current (i), total number of channels (N) and maximum open probability (Po,max) were determined by plotting this ensemble variance (σ2) against mean current (Ī) and fitting with the equation:

| (2) |

The weighted-mean single-channel conductance was calculated from the single-channel current and the holding potential. Po,max was estimated by dividing the average peak current by iN.

Recombinant receptors

tsA201 cells were grown according to standard protocols and transfected with DNA encoding AMPAR subunits, TARP γ-2 or γ-7 and EGFP by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as previously described 14. Cells were perfused with ‘external’ recording solution, containing 145 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES and 11 mM glucose (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). Glutamate application and NSFA was carried out as described above.

Single-channel analysis

Channel openings in the tail of macroscopic patch currents (both stellate cells and tsA201 cells) were analyzed using QuB (ver. 2.0.0.7; http://www.qub.buffalo.edu). Records were filtered at 4 kHz and pre-processed with piecewise linear baseline correction. Individual channel events were selected by eye, and for each selected record an all-point amplitude histogram was generated and fitted with two Gaussians to determine the amplitude of the single-channel current. On average, 50 channel events were measured from each patch.

Kinetic analysis

The decay of averaged EPSCs was described by one or more often two exponential functions. When fitted with two exponentials, the weighted time constant of decay (τw, decay) was calculated as the sum of the fast and slow time constants weighted by their fractional amplitudes.

Data presentation and statistical analysis

Data are presented in the text as mean ± s.e.m. The n number indicates the number of cells. In figures, box-and-whisker plots (Igor Pro) indicate the median value (red line), the 25-75th percentiles (box) and the 10-90th percentiles (whiskers). Open circles show individual values. Differences between control and stg/stg data were examined using non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum tests (unpaired) or Wilcoxon signed rank tests (paired), as appropriate. Group comparisons of data from recombinant receptors were performed using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test followed by pair-wise Wilcoxon rank-sum tests with Holm’s sequential Bonferroni correction or one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test (as indicated). Results were considered significant with p < 0.05. Statistical tests were performed using R 2.13.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; http://www.R-project.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant (S.G.C.-C. and M.F.) and a Medical Research Council Programme Grant (S.G.C.-C. and M.F.). C.B. was supported by a Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship. We thank all members of the S.G.C-C./M.F. laboratory for invaluable discussions. We are grateful to Leah Kelly and Anna Vanessa Stempel for help during early stages of the project and to Ian Coombs for assistance with molecular biology. Miwako Yamasaki and Masahiko Watanabe (Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine, Sapporo, Japan) generously shared unpublished data with us. We thank Gábor Szabó (Institute of Experimental Medicine, Budapest) for GAD65-GFP mice, kindly provided by Michael Häusser (Wolfson Institute, UCL), and Michael Hastings (Medical Research Council, Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge) for stargazer mice.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Experiments were performed by C.B. (stellate cell recordings), D.St. (granule cell recordings), and D.So. (tsA201 cell recordings). M.F., C.B., D.So. and D.St. analyzed the data. S.G.C-C. and M.F. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of experiments. C.B., M.F. and S.G.C-C. wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Traynelis SF, et al. Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:405–496. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L, et al. Stargazin regulates synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors by two distinct mechanisms. Nature. 2000;408:936–943. doi: 10.1038/35050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato AS, et al. New transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory protein isoform, gamma-7, differentially regulates AMPA receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:4969–4977. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5561-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soto D, et al. Selective regulation of long-form calcium-permeable AMPA receptors by an atypical TARP, gamma-5. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:277–285. doi: 10.1038/nn.2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomita S, et al. Functional studies and distribution define a family of transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory proteins. Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;161:805–816. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandenberghe W, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Stargazin is an AMPA receptor auxiliary subunit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:485–490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408269102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bats C, Groc L, Choquet D. The interaction between Stargazin and PSD-95 regulates AMPA receptor surface trafficking. Neuron. 2007;53:719–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnell E, et al. Direct interactions between PSD-95 and stargazin control synaptic AMPA receptor number. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13902–13907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172511199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedoukian MA, Weeks AM, Partin KM. Different domains of the AMPA receptor direct stargazin-mediated trafficking and stargazin-mediated modulation of kinetics. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23908–23921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho CH, St-Gelais F, Zhang W, Tomita S, Howe JR. Two families of TARP isoforms that have distinct effects on the kinetic properties of AMPA receptors and synaptic currents. Neuron. 2007;55:890–904. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korber C, Werner M, Kott S, Ma ZL, Hollmann M. The transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory protein gamma 4 is a more effective modulator of AMPA receptor function than stargazin (gamma 2) J Neurosci. 2007;27:8442–8447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0424-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milstein AD, Zhou W, Karimzadegan S, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. TARP subtypes differentially and dose-dependently control synaptic AMPA receptor gating. Neuron. 2007;55:905–918. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Priel A, et al. Stargazin reduces desensitization and slows deactivation of the AMPA-type glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2682–2686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4834-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soto D, Coombs ID, Kelly L, Farrant M, Cull-Candy SG. Stargazin attenuates intracellular polyamine block of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1260–1267. doi: 10.1038/nn1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomita S, et al. Stargazin modulates AMPA receptor gating and trafficking by distinct domains. Nature. 2005;435:1052–1058. doi: 10.1038/nature03624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turetsky D, Garringer E, Patneau DK. Stargazin modulates native AMPA receptor functional properties by two distinct mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7438–7448. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1108-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kott S, Sager C, Tapken D, Werner M, Hollmann M. Comparative analysis of the pharmacology of GluR1 in complex with transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory proteins gamma2, gamma3, gamma4, and gamma8. Neuroscience. 2009;158:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukaya M, Yamazaki M, Sakimura K, Watanabe M. Spatial diversity in gene expression for VDCCgamma subunit family in developing and adult mouse brains. Neurosci Res. 2005;53:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cull-Candy S, Kelly L, Farrant M. Regulation of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors: synaptic plasticity and beyond. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2006;16:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isaac JT, Ashby M, McBain CJ. The role of the GluR2 subunit in AMPA receptor function and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu SJ, Zukin RS. Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors in synaptic plasticity and neuronal death. Trends in Neurosciences. 2007;30:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellone C, Luscher C. Cocaine triggered AMPA receptor redistribution is reversed in vivo by mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:636–641. doi: 10.1038/nn1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chavez AE, Singer JH, Diamond JS. Fast neurotransmitter release triggered by Ca influx through AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Nature. 2006;443:705–708. doi: 10.1038/nature05123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardner SM, et al. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptor plasticity is mediated by subunit-specific interactions with PICK1 and NSF. Neuron. 2005;45:903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu SQJ, Cull-Candy SG. Synaptic activity at calcium-permeable AMPA receptors induces a switch in receptor subtype. Nature. 2000;405:454–458. doi: 10.1038/35013064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rozov A, Burnashev N. Polyamine-dependent facilitation of postsynaptic AMPA receptors counteracts paired-pulse depression. Nature. 1999;401:594–598. doi: 10.1038/44151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwak S, Weiss JH. Calcium-permeable AMPA channels in neurodegenerative disease and ischemia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashimoto K, et al. Impairment of AMPA receptor function in cerebellar granule cells of ataxic mutant mouse stargazer. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6027–6036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06027.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamazaki M, et al. TARPs gamma-2 and gamma-7 are essential for AMPA receptor expression in the cerebellum. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;31:2204–2220. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, et al. A single fear-inducing stimulus induces a transcription-dependent switch in synaptic AMPAR phenotype. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:223–231. doi: 10.1038/nn.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossi B, Maton G, Collin T. Calcium-permeable presynaptic AMPA receptors in cerebellar molecular layer interneurones. J Physiol. 2008;586:5129–5145. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.159921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly L, Farrant M, Cull-Candy SG. Synaptic mGluR activation drives plasticity of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:593–601. doi: 10.1038/nn.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu SQJ, Cull-Candy SG. Activity-dependent change in AMPA receptor properties in cerebellar stellate cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:3881–3889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-03881.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowie D, Lange GD, Mayer ML. Activity-dependent modulation of glutamate receptors by polyamines. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8175–8185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08175.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu SJ, Cull-Candy SG. Subunit interaction with PICK and GRIP controls Ca2+ permeability of AMPARs at cerebellar synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:768–775. doi: 10.1038/nn1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiszman ML, et al. NMDA receptors increase the size of GABAergic terminals and enhance GABA release. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2024–2031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4980-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leitch B, Shevtsova O, Kerr JR. Selective reduction in synaptic proteins involved in vesicle docking and signalling at synapses in the ataxic mutant mouse stargazer. J Comp Neurol. 2009;512:52–73. doi: 10.1002/cne.21890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark BA, Cull-Candy SG. Activity-dependent recruitment of extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activation at an AMPA receptor-only synapse. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4428–4436. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04428.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toth K, McBain CJ. Afferent-specific innervation of two distinct AMPA receptor subtypes on single hippocampal interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:572–578. doi: 10.1038/2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feldmeyer D, et al. Neurological dysfunctions in mice expressing different levels of the Q/R site-unedited AMPAR subunit GluR-B. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:57–64. doi: 10.1038/4561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swanson GT, Kamboj SK, Cull-Candy SG. Single-channel properties of recombinant AMPA receptors depend on RNA editing, splice variation, and subunit composition. J Neurosci. 1997;17:58–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00058.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tardin C, Cognet L, Bats C, Lounis B, Choquet D. Direct imaging of lateral movements of AMPA receptors inside synapses. EMBO J. 2003;22:4656–4665. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun L, June Liu S. Activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors induces a PKC-dependent switch in AMPA receptor subtypes in mouse cerebellar stellate cells. J Physiol. 2007;583:537–553. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.136788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menuz K, Stroud RM, Nicoll RA, Hays FA. TARP auxiliary subunits switch AMPA receptor antagonists into partial agonists. Science. 2007;318:815–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1146317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Menuz K, O’Brien JL, Karmizadegan S, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. TARP redundancy is critical for maintaining AMPA receptor function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8740–8746. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1319-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cathala L, Holderith NB, Nusser Z, DiGregorio DA, Cull-Candy SG. Changes in synaptic structure underlie the developmental speeding of AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1310–1318. doi: 10.1038/nn1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meng H, Walker N, Su Y, Qiao X. Stargazin mutation impairs cerebellar synaptogenesis, synaptic maturation and synaptic protein distribution. Brain Res. 2006;1124:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richardson CA, Leitch B. Phenotype of cerebellar glutamatergic neurons is altered in stargazer mutant mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA expression. J Comp Neurol. 2005;481:145–159. doi: 10.1002/cne.20386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gill MB, et al. Cornichon-2 modulates AMPA receptor-transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory protein assembly to dictate gating and pharmacology. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6928–6938. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6271-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson AC, Nicoll RA. Stargazin (TARP gamma-2) is required for compartment-specific AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity in cerebellar stellate cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3939–3952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5134-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.López-Bendito G, et al. Preferential origin and layer destination of GAD65-GFP cortical interneurons. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:1122–1133. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Letts VA, et al. The mouse stargazer gene encodes a neuronal Ca2+-channel gamma subunit. Nat Genet. 1998;19:340–347. doi: 10.1038/1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kudoh SN, Taguchi T. A simple exploratory algorithm for the accurate and fast detection of spontaneous synaptic events. Biosens Bioelectron. 2002;17:773–782. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(02)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chung C, Deak F, Kavalali ET. Molecular substrates mediating lanthanide-evoked neurotransmitter release in central synapses. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2089–2100. doi: 10.1152/jn.90404.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Traynelis SF, Silver RA, Cull-Candy SG. Estimated conductance of glutamate receptor channels activated during EPSCs at the cerebellar mossy fiber-granule cell synapse. Neuron. 1993;11:279–289. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90184-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.