Abstract

Legionella pneumophila is an opportunistic intracellular pathogen that causes sporadic and epidemic cases of Legionnaires’ disease. Emerging data suggest that Legionella infection involves the subversion of host phosphoinositide (PI) metabolism. However, how this bacterium actively manipulates PI lipids to benefit its infection is still an enigma. Here, we report that the L. pneumophila virulence factor SidF is a phosphatidylinositol polyphosphate 3-phosphatase that specifically hydrolyzes the D3 phosphate of PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3. This activity is necessary for anchoring of PI(4)P-binding effectors to bacterial phagosomes. Crystal structures of SidF and its complex with its substrate PI(3,4)P2 reveal striking conformational rearrangement of residues at the catalytic site to form a cationic pocket that specifically accommodates the D4 phosphate group of the substrate. Thus, our findings unveil a unique Legionella PI phosphatase essential for the establishment of lipid identity of bacterial phagosomes.

Keywords: phosphoinositide signaling, phagocytosis, membrane trafficking, type IV secretion system, virulence factor

The Legionella genus is mainly constituted by environmental bacteria. Several species, in particular Legionella pneumophila and Legionella longbeachae, are pathogenic to humans (1–3). Because of the development of artificial water systems, such as air conditioning, Legionnaires’ disease has emerged as a significant health threat in modern societies (4). Inhalation of L. pneumophila in contaminated aerosols allows the pathogen to reach the alveoli of the lung, where they can be phagocytosed by host macrophages. Once engulfed by macrophages, L. pneumophila delivers a large array of effector proteins into host cell through a specialized secretion system called defective organelle trafficking (Dot)/ intracellular multiplication (Icm) type IV secretion system (T4SS) (5, 6). The translocated Dot/Icm substrates hijack host cellular processes, particularly the membrane trafficking pathways to bypass the default phagosome maturation pathway. In fact, several Dot/Icm substrates mediate the recruitment of secretory vesicles derived from endoplasmic reticulum to establish a replication-permissive compartment called the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV) (7, 8). Because membrane trafficking is extensively regulated by phosphoinositides (PIs), studies on how host cell PI signaling and metabolism pathways are exploited by intracellular bacterial pathogen have recently been placed on the center of focus.

PIs are a collection of several lipid species that can be reversibly phosphorylated at the 3′, 4′, and 5′ positions of their inositol headgroup. PIs localize at the membrane–cytosol interfaces and achieve their functions through the recruitment of effector proteins to their cytoplasmic exposed headgroups. Although comprising less than 10% of total phospholipids, PIs are pivotal cellular regulators and play essential roles in a broad spectrum of cellular processes including defining intracellular organelle identity, cell signaling, proliferation, cytoskeleton organization, and membrane trafficking (9–11). Interference of the temporal and spatial distribution of intracellular PIs often leads to abnormal cellular functions, which has been capitalized by virulent invaders (12, 13). Bacterial pathogens have evolved a variety of mechanisms to subvert PI metabolism in host cells. For examples, Shigella flexneri, the causative agent of human dysentery, modifies PI metabolism in host cells to favor its internalization through the PI-4-phosphatase activity of the virulent factor IpgD (14). Salmonella typhimurium, which is responsible for most food-borne gastroenteritis (15), delivers the PI phosphatase SigD/SopB into the host. By hydrolyzing PI(3,4,5)P3, SopB contributes to the localized membrane ruffling that leads to bacterial internalization in nonphagocytic cells (16, 17).

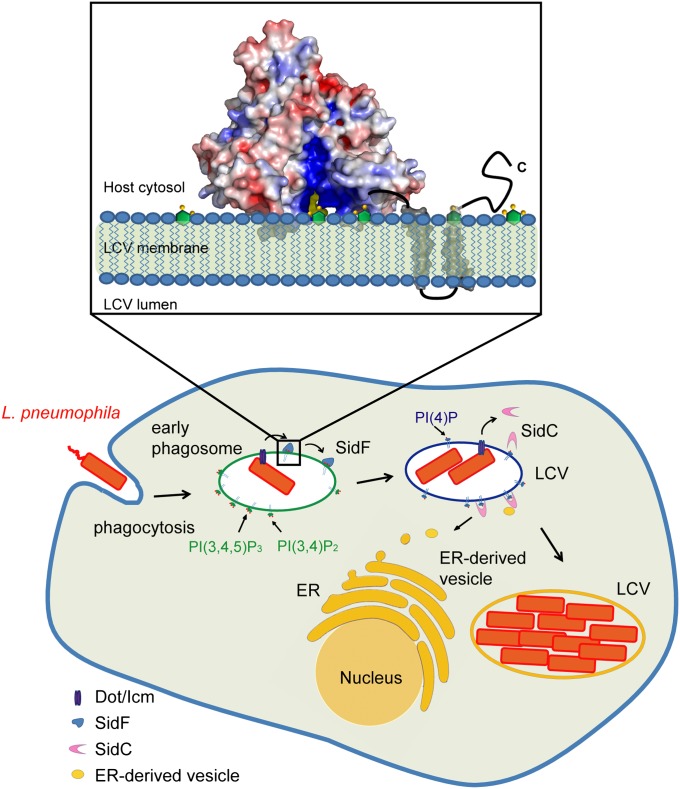

Modulation of host PI metabolism by Legionella is important for the establishment of the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV) within which the bacterium replicates (8, 12, 13). It has been suggested that PI(4)P is enriched on the LCV membrane, which among other functions, anchors effectors such as SidM/DrrA, SidC, and SdcA to promote the recruitment and fusion of the endoplasmic reticulum derived vesicles with the LCV (18, 19). In the amoebae host Dictyostelium discoideum, the Legionella effector protein LpnE appears to recruit the host PI-5-phosphatase OCRL to the LCV, leading to restriction of intracellular bacterial growth (20). Although significant progress has been made toward our understanding of the roles of PI metabolism in bacterial pathogenesis, our knowledge on how bacterial pathogens actively exploit host cell PI metabolism and signaling is still in its infancy. Currently, no virulence factors that directly modify host PIs have been identified in Legionella. Hence, we performed bioinformatic and biochemical studies on Legionella effector proteins. We identified the Legionella effector SidF as a unique PI phosphatase that specifically hydrolyzes PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3. In agreement with this enzymatic activity, we found that deletion of SidF results in the reduced recruitment of effector proteins that anchor on the LCV via binding to PI(4)P. We further report the crystal structures of SidF and its complex with bound short-chain (dibutanoyl) derivative of PI(3,4)P2. The structures show that the conserved “CX5R” catalytic motif is located in a large cationic groove. Remarkably, structural analysis reveals key features responsible for substrate specificity. Residue His233, located in a loop region between α6 and β5, translocates approximately 20 Å to the catalytic site and together, with a serine and three lysine residues, forms a pocket that specifically accommodates the D4 phosphate group of the substrate. Our findings uncover a family of bacterial PI phosphatases and establish a role of SidF in the maintenance of the lipid composition of LCV.

Results

Legionella Effector SidF Is a Phosphoinositide 3-Phosphatase.

To search for Legionella effector proteins that may directly modify host PIs, we used a sequence pattern based method to retrieve proteins containing the “CX5R” motif, a signature sequence of the catalytic residues in PI phosphatases (21), in the genome of L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1. More than 400 hypothetical proteins were found to possess this motif. Among these candidates, 29 proteins have been identified as substrates of the Dot/Icm transporter (22) (Table S1). Some of these proteins were then expressed, purified, and examined for in vitro PI phosphatase activities by a malachite green-based assay (23). SidF, a Dot/Icm substrate shown to be involved in modulating host cell death (24), was found to possess PI phosphatase activity (Fig. 1A). Mutation of the catalytic cysteine to serine (C645S) abolishes SidF PI phosphatase activity (Fig. 1A). SidF is comprised of 912 residues with a large N-terminal domain (1–760) of unknown function and two predicted transmembrane motifs at the C terminus (Fig. S1). Ectopically expressed GFP-SidF localizes to the ER membrane in mammalian cells (Fig. S2 A–C). Interestingly, deletion of the C-terminal portion of SidF including the two transmembrane motifs changes its localization to the cell periphery (Fig. S2 D–F), suggesting that the N-terminal cytosolic portion of SidF has the propensity to associate with membranes (discussed below). In agreement with the prediction of SidF as a membrane protein, endogenous SidF delivered into the host cell associates with the LCV membrane during Legionella infection (Fig. S3 A and B). These observations imply a role of SidF in controlling the lipid composition of the LCV membrane.

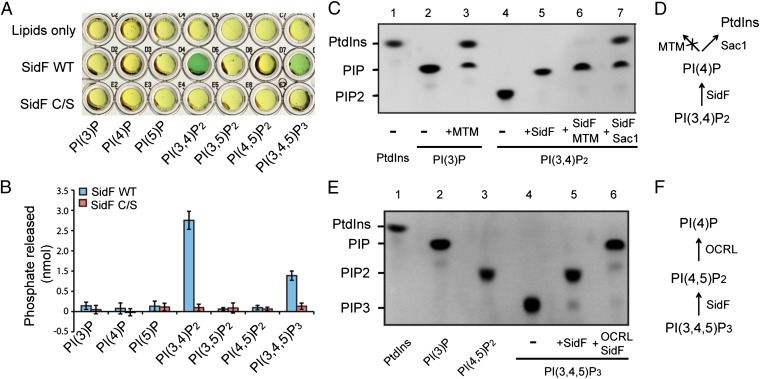

Fig. 1.

Legionella effector SidF is a phosphoinositide phosphatase. (A) Phosphoinositide substrate specificity of purified wild-type and C645S mutant SidF as determined by the malachite green assay (green color indicates the release of free phosphate). PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 are the preferred substrates. (B) Quantification of the amount of released phosphates. Data are from three replicate experiments (mean ± SEM). (C) Determination of SidF substrate specificity by fluorescent lipids. Phosphatase reactions were carried out with di-C8- Bodipy-FL-PI(3,4)P2 and PI phosphatases as labeled. In lane 6 and 7, the reactions were first carried out with SidF, and the products were further hydrolyzed by the addition of a specific 3-phosphatase MTM (lane 6) or Sac1 (lane 7), that hydrolyzes both PI(3)P and PI(4)P. (D) Schematic diagram to illustrate the enzymatic reactions shown in C. (E) TLC results of the hydrolysis of PI(3,4,5)P3 by SidF. In lane 6, the reaction was first carried out with SidF, and the products were further hydrolyzed by the addition of OCRL, a 5-phosphatase that hydrolyzes PI(4,5)P2. (F) Schematic illustration of the reactions in E.

Although SidF is a membrane protein, deletion of the putative transmembrane domains did not affect its enzymatic activity and, thus, the N-terminal portion (1–760) of SidF was used in our in vitro activity assays. SidF exhibited phosphatase activities against PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 with a preference for PI(3,4)P2 (Fig. 1 A and B). To further investigate the enzymatic function of SidF, a fluorescent phosphoinositide-based TLC method (25) was used to determine the specific phosphate group hydrolyzed by SidF (Fig. 1 C–F). SidF hydrolyzed PI(3,4)P2 to a single phosphorylated PI product (Fig. 1C, lane 5), and this product could not be further digested by the specific PI-3-phosphatase MTM (26). However, it could be hydrolyzed to phosphotidylinositol (PtdIns) by the Sac domain of yeast Sac1, a phosphatase that hydrolyzes both PI(3)P and PI(4)P (27) (Fig. 1C, lanes 6 and 7). This result suggests that SidF can specifically dephosphorylate PI(3,4)P2 at the D3 position of the inositol ring. Similarly, when PI(3,4,5)P3 was used as the substrate, double phosphorylated PI species were generated and this species could be further hydrolyzed by OCRL, a PI-5-phosphatase that hydrolyzes the D5 phosphate of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 (28) (Fig. 1E, lanes 5 and 6). Therefore, these results demonstrate that SidF is a PI-3-phosphatase that specifically hydrolyzes PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(4)P and PI(4,5)P2, respectively.

SidF Facilitates the Anchoring of Effector Proteins to Bacterial Phagosomes.

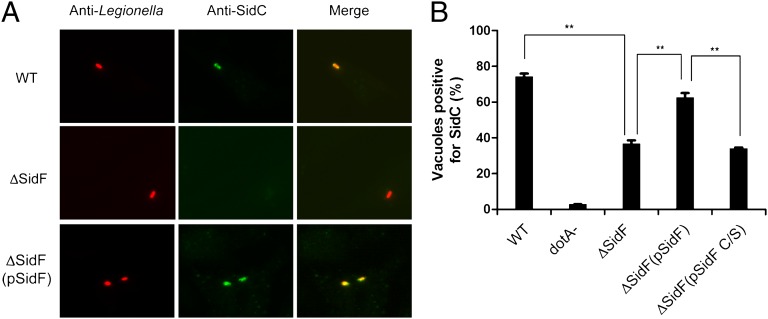

The identification of a PI phosphatase from L. pneumophila has addressed the long-standing hypothesis that this bacterium employs its own PI phosphatase(s) to actively modify the PI composition on bacterial phagosomes. Indeed, SidF converts PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3, which are two PI species generated on phagosomes at early stages of phagocytosis (29, 30), to PI(4)P and PI(4,5)P2, respectively. Intriguingly, PI(4,5)P2 may be further converted to PI(4)P by the host PI-5-phosphatase OCRL (20). Thus, one plausible hypothesis is that SidF plays a role in the establishment of LCVs with a lipid composition enriched in PI(4)P. It has been suggested that PI(4)P provides specific anchors on the LCV for Legionella effectors, such as SidC/SdcA (18) and SidM(DrrA) (31). Through binding to PI(4)P, these effectors presumably facilitate the fusion of ER-derived vesicles with the LCV. Hence, we examined the role of SidF in the association of SidC with LCVs. Strikingly, compared with the wild-type strain, the association of SidC with phagosomes formed by the sidF deletion mutant was significantly reduced, and such defect can be almost fully restored by expressing wild-type SidF from a plasmid but not the catalytically inactive SidF C645S mutation (Fig. 2 A and B). These observations are not due to the changes in total protein levels of SidC (Fig. S4). Instead, our data suggest that SidF facilitates the anchoring of PI(4)P binding effectors, such as SidC to the LCV membrane through the generation of PI(4)P.

Fig. 2.

SidF is required for anchoring SidC to the bacterial phagosomes. (A) Representative images of SidC immuno-staining of mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages infected with indicated L. pneumophila strains at an MOI of 1 for 1 h. (B) Quantitation of SidC positive bacterial phagosomes. Phagosomes positive for SidC staining are normalized against total phagosomes. Data shown are from two independent experiments performed in triplicate in which at least 100 phagosomes were scored per coverslip. **P < 0.01, paired Student t test. WT: L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 wild type strain Lp02; dotA-: the type IV secretion system defective strain Lp03(dotA-); ΔSidF: the sidF deletion mutant Lp02 strain; ΔSidF(pSidF): the sidF deletion Lp02 strain complemented with a plasmid expressing SidF and ΔSidF(pSidF C/S): the sidF deletion Lp02 strain complemented with a plasmid expressing SidF C/S catalytically dead mutant.

Crystal Structure of SidF.

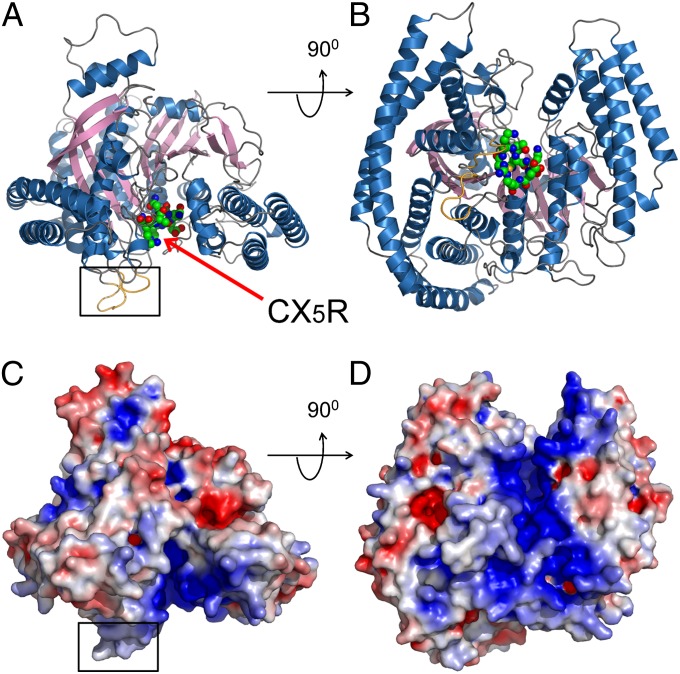

To understand the molecular mechanism of the catalytic function of SidF, the cytosolic portion (residues 1–760) of SidF (Fig. S5) was purified and crystallized. The crystal structure of SidF was determined by Single Isomorphous Replacement with Anomalous Scattering (SIRAS) method (Fig. S6 and Table S2). The crystal structure revealed that the entire N-terminal portion of SidF is folded into one large single domain (Fig. 3). This domain is comprised of 19 α-helices with lengths ranging from 6 to 60 amino acids surrounding a 10-pleated β-sheet core (Fig. S7). The overall shape of the phosphatase domain resembles a cowboy hat. The bottom of the hat has a flat surface with two protrusion loops (Fig. 3 A and C colored in gold and highlighted with a square). Interestingly, these two loops are mainly comprised of hydrophobic residues (Figs. S5 and S8). The catalytic CX5R motif (shown in spheres) resides in the middle of a groove that nearly bisects the bottom surface (Fig. 3 B and D). Like other PI phosphatases (32), this groove is enriched with positively charged residues, which contribute a highly basic character to the groove. These architectural arrangements suggest a molecular mechanism for PI hydrolysis by SidF at the membrane interface. The flat bottom surface of SidF may associate with the membrane with the two hydrophobic loops penetrating into the bilayer. When scooting on the membrane surface, the overall positive charge in the groove may facilitate the loading of negatively charged PI lipids into the catalytic site. Structural homology search by the DALI program (33) indicated that SidF has no overall structural homologs in the PDB database; however, the catalytic core of SidF bears similar topological fold with other PI phosphatases. Among these PI phosphatases, Sac1 has a highest Z-score of 8.6 and a rmsd of 4.1 Å for 240 aligned residues. The other phosphatase PTEN has a Z-score of 7.3 and an rmsd of 2.7 Å for 111 aligned residues (further discussed below).

Fig. 3.

Crystal structure of SidF. (A and B) Two orthogonal views of the crystal structure of SidF represented in ribbons. The catalytic “CX5R” motif is shown in spheres and indicated by an arrow. Two loops that protrude out from a flat surface (the bottom surface in A and C) are highlighted with a square and colored in gold. (C and D) Two orthogonal views of the crystal structure of SidF represented in surface. The surfaces are colored based on electrostatic potential with positively charged regions in blue (+4 kcal per electron) and negatively charged surface in red (−4 kcal per electron). C and D have an identical orientation as in A and B, respectively. Note that the catalytic motif is localized in a highly basic groove.

Structure of SidF-PI(3,4)P2 Complex.

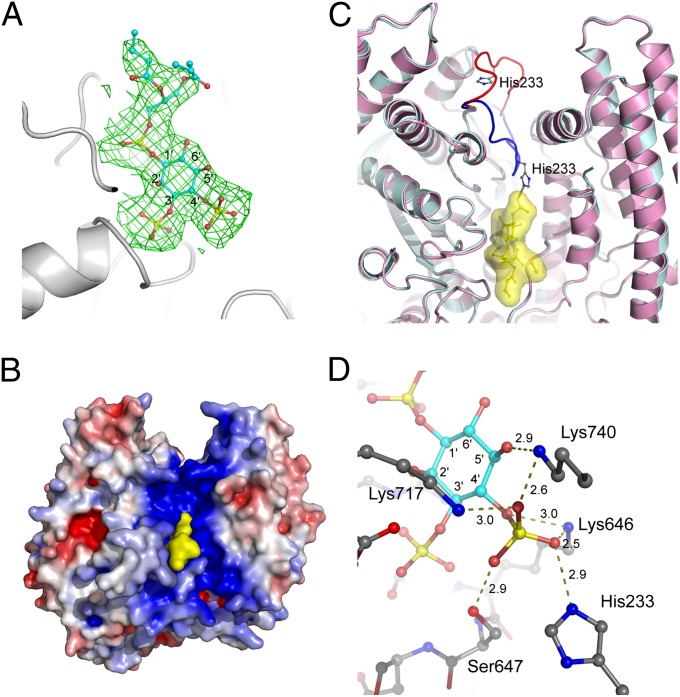

To address how SidF can specifically hydrolyze PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3, catalytically inactive (C645S) recombinant SidF (1–760) proteins were prepared. The mutant proteins were mixed with substrate diC4-PI(3,4)P2 [a dibutanoyl derivative of PI(3,4)P2] and screened for crystals of the protein–lipid complex. Diffraction data were processed and used in the refinement against the apo protein structure. After the first round of refinement, the difference Fourier electron density clearly revealed a well-defined substrate molecule diC4-PI(3,4)P2 bound at the catalytic site (Fig. 4 A and B). Remarkably, the binding of PI(3,4)P2 to SidF induces a large conformational change of the loop connecting α6 and β5. His233 on this loop shifts approximately 20 Å to the substrate binding site (Fig. 4C), where His233, together with Ser647 and three lysines (Lys646, Lys717, and Lys740), forms a highly cationic pocket that selectively accommodates the D4 phosphate group of the substrate (Fig. 4D). The phosphate group at the D3 position of PI(3,4)P2 is also heavily involved in the interaction with SidF. The D3 phosphate group subject to hydrolysis forms intensive hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions with five main chain amide groups of the catalytic CX5R loop and the guanidinium group of the CX5R arginine Arg651 (Figs. S8 and S9). The D1 phosphate group of the substrate is less involved in the interaction with the enzyme. It forms electrostatic interactions with Arg651 and one hydrogen bond with the amido group of Asn419 (Figs. S8 and S9). It is also notable that the diacylglycerol moiety of the substrate molecule makes significant contact with several hydrophobic residues, including Trp420 and Phe421 (Figs. S5 and S10). These hydrophobic residues are located within the two hydrophobic protrusion loops and may penetrate into the lipid bilayer during hydrolysis.

Fig. 4.

Substrate recognition by SidF. (A) Difference electron density map (Fo−Fc at 3σ, green mesh) calculated near the catalytic site. The substrate diC4-PI(3,4)P2 molecule shown in sticks fits nicely in the electron density. (B) A view of the SidF–substrate complex represented in surface. The substrate colored in yellow binds deeply in the positively charged groove at the catalytic site. (C) The binding of substrate induces a large conformation change of a loop containing residue His233. The apo structure is shown in pink with the His233 loop shown in red. The complex structure is colored in cyan with the corresponding loop in blue. The diC4-PI(3,4)P2 molecule is shown in sticks and enveloped in a yellow surface. His233 forms a hydrogen bond with the D4 phosphate group of the substrate. (D) Specific recognition of the D4 phosphate group of the substrate. Five residues (Lys717, Lys740, Lys466, Ser647, and His233) form a basic pocket that holds the D4 phosphate through an intensive hydrogen bond network and electrostatic interactions. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines, and the distance in Å is labeled.

SidF also hydrolyzes PI(3,4,5)P3 but with less efficiency compared with PI(3,4)P2. Based on our complex structure, it can be predicted that the D5 phosphate will be exposed to solvent and no significant interactions can be formed with the protein (Fig. S11). Instead, the presence of a glutamate residue (Glu370) near the D5 position may repel the binding of D5 phosphate of PI(3,4,5)P3, which may explain the lower activity of SidF against PI(3,4,5)P3 (Fig. 1A).

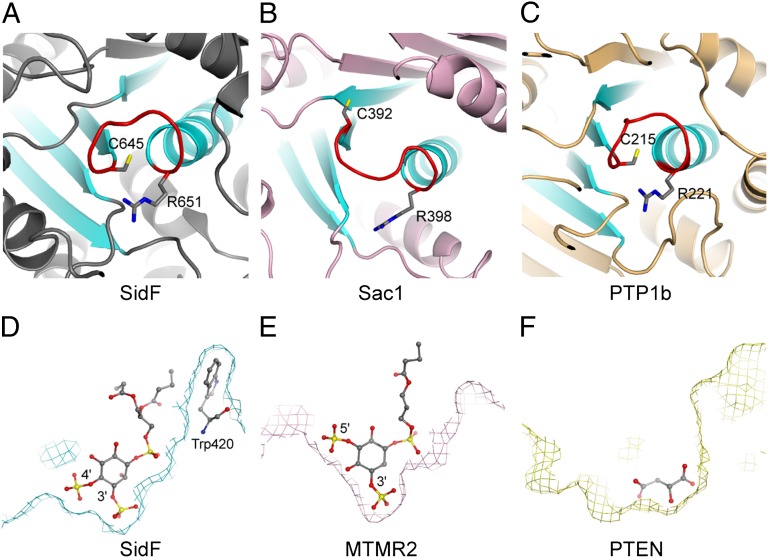

Structure Comparison of SidF to Other Phosphatases.

Despite the lack of detectable overall sequence and structural fold similarity, comparison of the structure of SidF with other CX5R motif-based protein and lipid phosphatases reveals that the topology of the catalytic core of SidF is conserved with other phosphatases. All CX5R motif-based phosphatases share a common architecture of a central β-sheet consisting of four parallel β strands and one α helix. The peptide containing the catalytic CX5R motif connects the carboxyl end of one of the β strands with the amino terminus of the α helix in the structural core (Fig. 5 A–C) (32, 34–36). It is interesting to note that the electric dipole of this α helix contributes net-positive electrostatic potentials to its amino terminus, where the catalytic site resides. Hence, this structural organization may facilitate the docking of negatively charged phosphate group of the substrate.

Fig. 5.

Structure comparison of SidF with other phosphoinositide phosphatases. (A) Ribbon diagram showing the topology of the SidF active site. This conserved structural core contains four parallel β strands and one α helix (colored in cyan). The catalytic CX5R motif (colored in red and the conserved cysteine and arginine residues shown in sticks) is located between the C terminus of one of β strands and the first turn of the α helix. (B and C) The active site topology of Sac1 (32) and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1b (PTB1b) (42). (D) Slice of the active site surface showing the docking of substrate diC4-PI(3,4)P2 at the active site. diC4-PI(3,4)P2 is shown in sticks. In this particular slice, Trp420 can be seen to form hydrophobic interactions with the lipid tails of the substrate. (E) Slice of the active site surface of MTMR2 (37, 38) with a diC4-PI(3,5)P2 molecule shown in sticks bound at the active site. (F) Slice of the active site surface of PTEN (36). The active site pocket is occupied by a tartrate molecule. Comparison of these three PI phosphatases suggests the overall shape of the catalytic site pocket may also play a role in substrate selectivity.

Structural comparison of SidF with other PI phosphatases, such as the myotubularin phosphatases (37, 38) and the tumor suppressor PTEN (36), further reveals the difference in the overall shape of the active site pocket, which is one of the key determinants for substrate specificity. In SidF, the active site pocket is deep and wide at the bottom to fit the two adjacent phosphate groups at D3 and D4 position (Fig. 5D). However, in MTMR2, which hydrolyzes both PI(3)P and PI(3,5)P2, the width of the active site pocket is much narrower at the bottom region that limits the hydrolysis of substrates with two consecutive phosphate groups attached. Steric clashes between the protein and the lipid prohibit the binding of PI molecules phosphorylated at the D4 position to MTMR2 (Fig. 5E). The active site in PTEN is much wider, consistent with the larger size of its preferred substrate PI(3,4,5)P3 (Fig. 5F).

Discussion

Although PI phosphatases have been reported from other bacterial pathogens, such as the PI-4-phosphatases IpgD from Shigella flexneri (14), SigD/SopB from S. typhimurium (16, 17), no such enzymes have been reported from Legionella species. Our discovery of a PI phosphatase in L. pneumophila not only establishes an archetypal family of PI phosphatase, but also opens a new avenue toward the understanding of the roles of PI signaling and metabolism in L. pneumophila infection.

Our results further demonstrated a role of SidF in maintaining the PI composition of LCV. By hydrolyzing PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 that are generated on phagosomes at their early stage (29, 30), SidF (possibly in coordination with other possible PI metabolizing enzymes either from host or bacterium) converts the LCV into a PI(4)P enriched organelle. As a result, the lipid composition of LCV would resemble that of the cis-Golgi compartment and may render the LCV a better recipient site for secretory vesicles originating from ER. PI(4)P enrichment at the LCV also provides specific membrane anchors for PI(4)P binding effector proteins. Deletion of SidF from L. pneumophila significantly reduced the anchoring of PI(4)P binding effectors such as SidC on LCV compartments (Fig. 2). The residual association of SidC with the LCVs may result from additional bacterial effectors with activity similar to that of SidF, or host proteins involved in the production of PI(4)P, or a combination of both.

The hydrolysis of PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 by SidF at the D3 position may also play a role in preventing the conversion of these two lipids into PI(3)P by other 4- or 5-phosphatases, such as SHIP-1 and Inpp4A during endocytic processes (39). It has been shown that the accumulation of PI(3)P at the phagosome membrane facilitates the fusion of phagosome with endosomes and lysosomes (40, 41) and promotes the degradation of phagosomal contents. However, the precise lipid composition of LCV is not known. A thorough understanding of the role of SidF in controlling the PI composition and the fate of LCV would require lipid composition analysis on purified LCVs under a variety of genetic backgrounds and infection stages.

SidF has been shown to play a role in conferring cell death resistance in infected macrophages by interacting through its C-terminal portion with BNIP3 and Bcl-rambo, two prodeath members of the Bcl2 protein family (24). Here, we further show that the N-terminal part of SidF is a specific PI-3-phosphatase. Given the pleiotropic effects of PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 on cellular physiology, including the cell surviving process (9–11), it is clear that SidF is a multifunctional protein that may be involved in diverse biological processes of the host by distinct mechanisms. Future investigations are required to elucidate the role of SidF in host PI3K signaling pathways and their potential interplays with the host cell-death process under infection conditions.

Our findings led us to propose a functional model of SidF on the bacterial phagosome (Fig. 6). In this model, SidF is delivered into the host through the Dot/Icm complex and anchors on the LCV membrane via two C-terminal transmembrane domains. The flat surface of the catalytic domain is interfaced with the LCV membrane, and the two hydrophobic loops are inserted into the hydrophobic lipid bilayer. SidF then hydrolyzes PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3, which may cause the accumulation of PI(4)P on LCV and the subsequent recruitment of other effectors that anchor on the LCV membrane through the binding to PI(4)P. By controlling the lipid composition of LCV, SidF may facilitate the programming of LCV to an amenable niche for bacterial growth to escape from the default degradative phagolysosomal pathway.

Fig. 6.

Functional model of SidF. The Legionella effector protein SidF is a PI-3-phosphatase that specifically hydrolyzes PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3. By the action of SidF and/or other unknown mechanisms, a PI(4)P enriched LCV membrane is established. PI(4)P enrichment may allow specific anchoring of Dot/Icm effectors, such as SidC, to the LCV, thus facilitates the recruitment and fusion of ER-derived vesicles with the LCV. (Inset) Molecular mechanisms of SidF. SidF anchors on the LCV membrane through its C-terminal double transmembrane motifs. The flat surface of the cytosolic domain of SidF interfaces with the LCV membrane and the two hydrophobic loops protruding out from the flat surface penetrate into the bilayer. The basic charges in the catalytic groove facilitate the loading of substrate into the catalytic site.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and Mutagenesis.

PCR products for SidF amplified from L. pneumophila genomic DNA was digested and inserted into a pET28a-based vector in frame with an N-terminal His-SUMO tag. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Point mutations were generated by site directed mutagenesis.

Protein Expression and Purification.

For protein expression, Escherichia coli Rosetta strains harboring the expression plasmids were grown in Luria–Bertani medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin to midlog phase. Protein expression was induced for overnight at 18 °C with 0.1 mM isopropyl-B-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Harvested cells were resuspended in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris⋅HCl at pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) and were lysed by sonication. Soluble fractions were collected by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C and incubated with cobalt resins (Clontech) for 1 h at 4 °C. Protein bound resins were extensively washed with lysis buffer. The SUMO-specific protease Ulp1 was then added to the resin slurry to release SidF from the His-SUMO tag. Eluted protein samples were further purified by FPLC size exclusion chromatography. The peak corresponding to SidF was pooled and concentrated to 10 mg/mL in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris at pH 7.4 and 150 mM NaCl. To express recombinant OCRL proteins, OCRL gene was cloned into a pFAST-based vector in frame with an N-terminal His-GST tag. Baculovirus was generated by using standard protocols (Invitrogen). Tni cells at 2 × 106 cells per mL were infected with baculovirus for 2 d. Cells were harvested and lysed as described above. Recombinant OCRL proteins were affinity purified with glutathione Sepharose resins (GE). Other materials and methods used are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. P. Bretscher, S. D. Emr, F. Hu, S. Qian, and Z. Gu for discussions and S. E. Ealick for reagents. This work was supported by a Cornell startup fund (to Y.M.) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01-GM094347 (to Y.M.), K02AI085403 (to Z.-Q.L.), and R21AI092043 (to Z.-Q.L.). The X-ray data were collected at MacChess beamline A1 and National Synchrotron Light Source beamline X4C. Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source is supported by the National Science Foundation and NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences via National Science Foundation Award DMR-0225180, and the MacCHESS resource is supported by NIH/National Center for Research Resources Award RR-01646.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 4FYE (native apo SidF), 4FYF (Hg-bound form), and 4FYG (C645S mutant in complex with diC4-PI(3,4)P2)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1207903109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.McDade JE, et al. Legionnaires’ disease: Isolation of a bacterium and demonstration of its role in other respiratory disease. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1197–1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197712012972202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraser DW, et al. Legionnaires’ disease: Description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1189–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197712012972201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKinney RM, et al. Legionella longbeachae species nova, another etiologic agent of human pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:739–743. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-94-6-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fields BS, Benson RF, Besser RE. Legionella and Legionnaires’ disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:506–526. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.3.506-526.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segal G, Purcell M, Shuman HA. Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1669–1674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel JP, Andrews HL, Wong SK, Isberg RR. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science. 1998;279:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isberg RR, O’Connor TJ, Heidtman M. The Legionella pneumophila replication vacuole: Making a cosy niche inside host cells. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubber A, Roy CR. Modulation of host cell function by Legionella pneumophila type IV effectors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:261–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odorizzi G, Babst M, Emr SD. Phosphoinositide signaling and the regulation of membrane trafficking in yeast. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Matteis MA, Godi A. PI-loting membrane traffic. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:487–492. doi: 10.1038/ncb0604-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ham H, Sreelatha A, Orth K. Manipulation of host membranes by bacterial effectors. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:635–646. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pizarro-Cerdá J, Cossart P. Subversion of phosphoinositide metabolism by intracellular bacterial pathogens. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1026–1033. doi: 10.1038/ncb1104-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niebuhr K, et al. Conversion of PtdIns(4,5)P(2) into PtdIns(5)P by the S.flexneri effector IpgD reorganizes host cell morphology. EMBO J. 2002;21:5069–5078. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.House D, Bishop A, Parry C, Dougan G, Wain J. Typhoid fever: Pathogenesis and disease. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2001;14:573–578. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200110000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakowski MA, Braun V, Brumell JH. Salmonella-containing vacuoles: Directing traffic and nesting to grow. Traffic. 2008;9:2022–2031. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel JC, Hueffer K, Lam TT, Galán JE. Diversification of a Salmonella virulence protein function by ubiquitin-dependent differential localization. Cell. 2009;137:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber SS, Ragaz C, Reus K, Nyfeler Y, Hilbi H. Legionella pneumophila exploits PI(4)P to anchor secreted effector proteins to the replicative vacuole. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ragaz C, et al. The Legionella pneumophila phosphatidylinositol-4 phosphate-binding type IV substrate SidC recruits endoplasmic reticulum vesicles to a replication-permissive vacuole. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2416–2433. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber SS, Ragaz C, Hilbi H. The inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase OCRL1 restricts intracellular growth of Legionella, localizes to the replicative vacuole and binds to the bacterial effector LpnE. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:442–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norris FA, Wilson MP, Wallis TS, Galyov EE, Majerus PW. SopB, a protein required for virulence of Salmonella dublin, is an inositol phosphate phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14057–14059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu W, et al. Comprehensive identification of protein substrates of the Dot/Icm type IV transporter of Legionella pneumophila. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maehama T, Taylor GS, Slama JT, Dixon JE. A sensitive assay for phosphoinositide phosphatases. Anal Biochem. 2000;279:248–250. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banga S, et al. Legionella pneumophila inhibits macrophage apoptosis by targeting pro-death members of the Bcl2 protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5121–5126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611030104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor GS, Dixon JE. An assay for phosphoinositide phosphatases utilizing fluorescent substrates. Anal Biochem. 2001;295:122–126. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor GS, Maehama T, Dixon JE. Myotubularin, a protein tyrosine phosphatase mutated in myotubular myopathy, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8910–8915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160255697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo S, Stolz LE, Lemrow SM, York JD. SAC1-like domains of yeast SAC1, INP52, and INP53 and of human synaptojanin encode polyphosphoinositide phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12990–12995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erdmann KS, et al. A role of the Lowe syndrome protein OCRL in early steps of the endocytic pathway. Dev Cell. 2007;13:377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamen LA, Levinsohn J, Swanson JA. Differential association of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, SHIP-1, and PTEN with forming phagosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2463–2472. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vieira OV, et al. Distinct roles of class I and class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases in phagosome formation and maturation. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:19–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brombacher E, et al. Rab1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor SidM is a major phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate-binding effector protein of Legionella pneumophila. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4846–4856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807505200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manford A, et al. Crystal structure of the yeast Sac1: Implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase function. EMBO J. 2010;29:1489–1498. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holm L, Sander C. Dali: A network tool for protein structure comparison. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:478–480. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barford D, Flint AJ, Tonks NK. Crystal structure of human protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Science. 1994;263:1397–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuckey JA, et al. Crystal structure of Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase at 2.5 A and the complex with tungstate. Nature. 1994;370:571–575. doi: 10.1038/370571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee JO, et al. Crystal structure of the PTEN tumor suppressor: Implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity and membrane association. Cell. 1999;99:323–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Begley MJ, et al. Molecular basis for substrate recognition by MTMR2, a myotubularin family phosphoinositide phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:927–932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510006103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Begley MJ, et al. Crystal structure of a phosphoinositide phosphatase, MTMR2: Insights into myotubular myopathy and Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1391–1402. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin HW, et al. An enzymatic cascade of Rab5 effectors regulates phosphoinositide turnover in the endocytic pathway. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:607–618. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vergne I, Chua J, Deretic V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome maturation arrest: Selective targeting of PI3P-dependent membrane trafficking. Traffic. 2003;4:600–606. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flannagan RS, Cosío G, Grinstein S. Antimicrobial mechanisms of phagocytes and bacterial evasion strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:355–366. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puius YA, et al. Identification of a second aryl phosphate-binding site in protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B: A paradigm for inhibitor design. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13420–13425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.