ABSTRACT

Termites and their gut microbes engage in fascinating dietary mutualisms. Less is known about how these complex symbioses have evolved after first emerging in an insect ancestor over 120 million years ago. Here we examined a bacterial gene, formate dehydrogenase (fdhF), that is key to the mutualism in 8 species of “higher” termite (members of the Termitidae, the youngest and most biomass-abundant and species-rich termite family). Patterns of fdhF diversity in the gut communities of higher termites contrasted strongly with patterns in less-derived (more-primitive) insect relatives (wood-feeding “lower” termites and roaches). We observed phylogenetic evidence for (i) the sweeping loss of several clades of fdhF that may reflect extinctions of symbiotic protozoa and, importantly, bacteria dependent on them in the last common ancestor of all higher termites and (ii) a radiation of genes from the (possibly) single allele that survived. Sweeping gene loss also resulted in (iii) the elimination of an entire clade of genes encoding selenium (Se)-independent enzymes from higher termite gut communities, perhaps reflecting behavioral or morphological innovations in higher termites that relaxed preexisting environmental limitations of Se, a dietary trace element. Curiously, several higher termite gut communities may have subsequently reencountered Se limitation, reinventing genes for Se-independent proteins via convergent evolution. Lastly, the presence of a novel fdhF lineage within litter-feeding and subterranean higher (but not other) termites may indicate recent gene “invasion” events. These results imply that cascades of perturbation and adaptation by distinct evolutionary mechanisms have impacted the evolution of complex microbial communities in a highly successful lineage of insects.

IMPORTANCE

Since patterns of relatedness between termite hosts are broadly mirrored by the relatedness of their symbiotic gut microbiota, coevolution between hosts and gut symbionts is rightly considered an important force that has shaped dietary mutualism since its inception over 120 million years ago. Apart from that concerning lateral gene or symbiont transfer between termite gut communities (for which no evidence yet exists), there has been little discussion of alternative mechanisms impacting the evolution of mutualism. Here we provide strong gene-based evidence for past environmental perturbations creating significant upheavals that continue to reverberate throughout the gut communities of species comprising a single termite lineage. We suggest that symbiont extinction events, sweeping gene losses, evolutionary radiations, relaxation and reemergence of key nutritional pressures, convergent evolution of similar traits, and recent gene invasions have all shaped gene composition in the symbiotic gut microbial communities of higher termites, currently the most dominant and successful termite family on Earth.

Introduction

Identifying factors associated with changing genetic diversity in natural microbial populations is crucial for understanding past and present ecology. Host-associated microbial populations have garnered much interest, as principles of evolution uncovered in the context of host-microbe interactions have wide-ranging applications (e.g., human health, animal development, agriculture) (1–3). In particular, studies of animal-microbe mutualism have revealed that microbial symbionts exert an important selective force for evolution in their eukaryotic hosts (3). Equally intriguing are the pressures that symbiosis imparts on the evolution of the hosts’ microbial counterparts.

Many evolutionary studies on microbial symbiosis have explored the highly intimate mutualisms existing between insects and the microbial endosymbionts that live inside host insect cells (e.g., aphid [Buchnera] and tsetse fly [Wigglesworthia]) (4–6). These nutritional symbioses are obligate and characterized by low species complexity (typically, 1 symbiont species is present) (7–9). As such, they have been useful model systems for identifying the major evolutionary consequences of symbiosis in the microbial partners of mutualism: cospeciation with the host, genome reduction, low genomic GC content, and accelerated sequence evolution (10–14). However, such studies have limited potential for revealing the consequences of symbiosis between animal hosts and their extracellular symbionts, a category that includes gut tract microbes. As these symbioses can involve multiple microbial partners functioning as a “community bioreactor” to affect health or disease in their host, determining how interactions between different symbiont species have evolved is necessary to understanding host-symbiont synergisms.

The obligate nutritional mutualism occurring between wood-feeding termites and their specific and complex hindgut microbiota offers an enticing subject for studies of evolutionary themes in polymicrobial, extracellular symbiont communities. Remarkably, mutualism, which underpins the insect’s ability to access lignocellulose as a food source, predates the evolution of termites from their wood-feeding roach ancestors over 120 million years ago (15). Similar to endosymbioses, this long-term association has been facilitated by symbiont transfer between host generations (16), allowing coevolution between hosts and the symbiont community. Cospeciation as an evolutionary theme has indeed emerged over the past decade (e.g., 17–23); however, factors like diet, gut anatomy, and geography are also potential determinants of gene diversity in gut communities. Compared to endosymbionts, gut symbionts are exposed to considerably more environmental influence as food and environmental microbes continually pass through the gut tract. Under certain conditions, these microbes may establish as new symbionts or may horizontally transfer their genes to preexisting symbionts. Thus, termites and their rich diversity of gut microbial partners, which can number over 300 bacterial phylotypes (24, 25), provide exceptional opportunities for studying factors affecting evolution in symbiont communities.

Comparing symbiont genes in a wide range of termite host species is one way to learn about factors influencing symbiont evolution. Previously, we applied this comparative approach to symbiont metabolic genes encoding hydrogenase-linked formate dehydrogenase (fdhF) (37), important for CO2 reductive acetogenesis, a key mutualistic process in lignocellulose degradation (26, 27). In all wood-feeding termites and roaches, CO2 reductive acetogenesis is the major means of recycling the energy-rich H2 derived from wood-polysaccharide fermentations into acetate, the insect’s primary fuel source (28, 29). Study of fdhF in evolutionary less derived wood-feeding insects (the so-called primitive, “lower” termites and their wood-feeding roach relatives) implied that the trace element selenium has shaped the gene content of gut symbionts since termites diversified from roaches ~150 million years ago (15). More broadly, results suggested that, within related insect hosts that feature the same type of gut tract architecture and similar gut communities and diets, acetogenic symbionts as a metabolic subgroup of the greater gut community have maintained remarkably similar strategies to deal with changes in a key nutrient. But how have these symbionts (more precisely, their genes) responded to drastic changes in the termite gut, for example, to major alterations in gut tract architecture and to restructuring of the gut community itself?

To address this question, a comparison of fdhF genes present in extant insect species possessing gut communities representing “before” and “after” snapshots of drastic change is needed. The gut communities of lower termites represent the “before” condition. Gut communities in higher termites, which form the most recently evolved termite lineage (Termitidae), represent the “after” snapshot (30). Higher termites are known for highly segmented gut tracts and their lack of symbiotic gut protozoa (31), the primary sources of H2 within the guts of earlier-evolved wood-feeding insects. Gut segmentation and the extinction of lignocellulose-fermenting protozoa are events that are thought to have occurred early during the emergence of this lineage, possibly in the late Cretaceous era (80 million years ago) to early Cenozoic era (50 million years ago) (15). Since then, higher termites with their gut symbionts have found ways to access polysaccharides bound in forms other than wood (e.g., dry grass, leaf litter, organic compounds in soil) and have become the most abundant and diverse termite group on Earth.

Here we investigated whether the dramatic shifts in termite biology and microbiology marking the diversification of higher termites into their extant forms have had lasting effects on the H2-consuming symbiont community. To accomplish this, we analyzed the phylogeny of fdhF from the symbiotic gut communities of 8 higher termite species. The specimens belonged to the Nasutiterminae and Termitinae subfamilies, the two most numerically abundant and species-rich subfamilies within Termitidae (generally recognized as comprising four subfamilies [15, 32–34]), and were sampled from rainforest, beach, and desert environments in Central America and the southwestern United States. We compared higher termite fdhF sequences to each other and to previous data from less-derived wood-feeding insects. Our results indicate that the H2-consuming bacterial community in higher termites experienced early evolutionary extinctions, possibly due to extinction of H2-producing protozoa, followed by evolutionary radiation, convergent evolution, and even invasion. The latter three outcomes may have been influenced by trace element bioavailability. Together, the data provide a clear example of an extinction propagating through a chain of microbial mutualism, emphasizing the connectivity of symbiosis involving complex extracellular microbial communities such as those in the termite gut.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

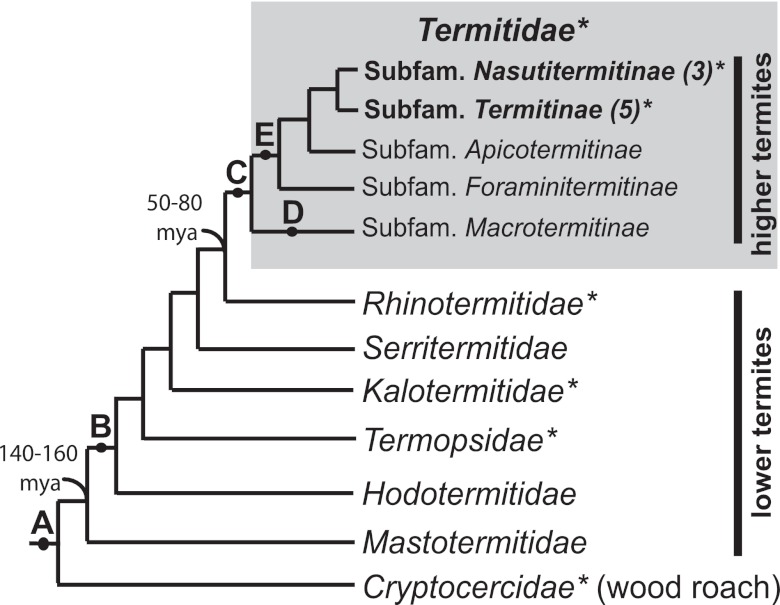

To profile fdhF in the whole-gut microbial communities of higher termites with different species affiliations (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), habitats, and lifestyles, we constructed fdhF gene inventories (30 to 107 clones per species [total, 684]) from the whole-gut tracts of six higher termite species from Costa Rica and two higher termite species from California (Table 1). The broader taxonomic affiliations for higher termite specimens are indicated in a schematic termite cladogram (Fig. 1). Multiple genotypes (8 to 59) and phylotypes (4 to 12 operational taxonomic units, or OTUs, at a 97% protein sequence similarity cutoff) were recovered from the guts of each termite sample (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). This represents significantly more diversity than that discovered by metagenomic analysis of a wood-feeding higher termite’s gut microbiota (35). In total, 62 novel FDHH OTUs were documented in higher termites. To stringently estimate sampling completeness, we compared the number of observed OTUs to that predicted by the 95% higher confidence interval for mean Chao1 values (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), calculated using EstimateS (36). On average, 4.9 ± 4.5 (1 standard deviation [SD]) more OTUs were missing per inventory. However, by comparing the observed number of OTUs with mean Chao1 values, on average, less than 1 OTU remained undiscovered per inventory.

TABLE 1 .

Characteristics of higher termites examined in this study

| Insect | Family (subfamily)a | Nest, locationb | Ecosystemc | Foodd | Soile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasutitermes sp. Cost003 | Termitidae (Nasutitermitinae) | Arboreal, forest (CR) | Premontane-wet rainforest transition | Wood | Low |

| Nasutitermes corniger Cost007 | Termitidae (Nasutitermitinae) | Arboreal, forest-beach transition (CR) | Lowland moist forest | Palm | Low |

| Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004 | Termitidae (Nasutitermitinae) | Arboreal, forest (CR) | Premontane-wet rainforest transition | Leaf litter | Medium |

| Microcerotermes sp. Cost006 | Termitidae (Termitinae) | Arboreal, forest-beach transition (CR) | Lowland moist forest | Palm | Low |

| Microcerotermes sp. Cost008 | Termitidae (Termitinae) | Arboreal, forest-beach transition (CR) | Lowland moist forest | Palm | Low |

| Amitermes sp. Cost010 | Termitidae (Termitinaef) | Subterranean, root zone (CR) | Premontane-wet forest | Roots/soil | High |

| Amitermes sp. JT2 | Termitidae (Termitinaef) | Subterranean galleries, desert (JT) | Warm temperate desert | Dry grass/soil | High |

| Gnathamitermes sp. JT5 | Termitidae (Termitinaef) | Subterranean galleries, desert (JT) | Warm temperate desert | Dry grass/Yucca/soil | High |

Termite family classifications are based on references 15 and 55.

Data represent nest type, collection site. CR, Costa Rica; JT, Joshua Tree National Park, CA.

Ecosystem terminology is based on the Holdridge life zone classification of land areas (58). Life zone categories for collection sites are based on maps in Holdridge et al. (58) and Enquist (59).

Possible food source based on vegetation near collection location, insect trails, and/or laboratory feeding.

Predicted level of soil exposure based on nest location (subterranean or above ground), food substrate, and foraging style.

It is unclear whether Amitermes spp. affiliate within the subfamily Termitinae or rather constitute their own subfamily.

FIG 1 .

Schematic cladogram of major termite families and higher termite subfamilies showing major events in gut habitat evolution. Key events were (A) hindgut fermentation of lignocellulose; (B) loss of Blattabacterium fat body endosymbionts; (C) loss of mutualistic gut protists; (D) gain of mutualism with Termitomyces fungus; and (E) development of diverse feeding habits (e.g., soil feeding [15, 30]). Estimated timings (in millions of years ago [mya]) for the divergence of termites from wood roaches and of higher from lower termites are indicated. Family and subfamily associations of higher termites examined in this study are indicated in bold. Numbers of species examined are indicated in parentheses. This study analyzed gut community fdhF in the insect groups marked by asterisks.

Broad-scale diversity of higher termite fdhF.

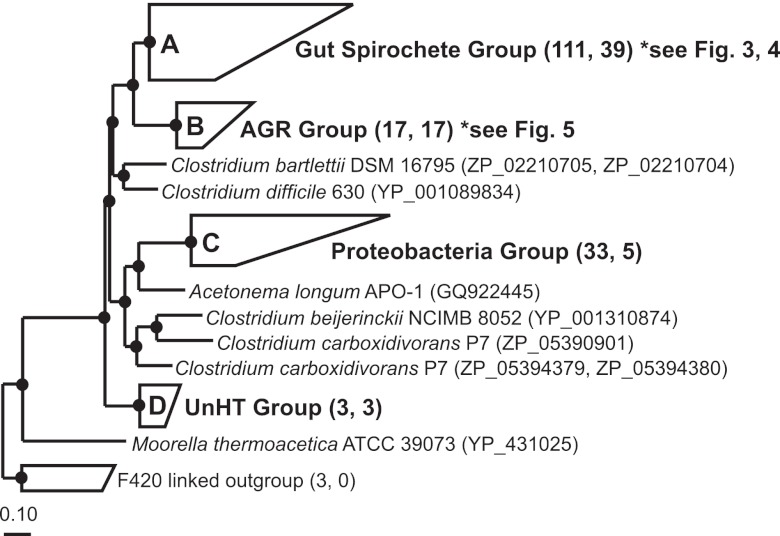

Our previous studies of fdhF (37, 38) have shown that genes for hydrogenase-linked formate dehydrogenase enzymes (FDHH [EC 1.2.1.2], encoded by enteric Gammaproteobacteria, Spirochaetes, and Firmicutes) are widespread in the guts of lower termites and wood roaches. Almost all fdhF recovered from these insects grouped most closely with genes from the Treponema primitia termite gut acetogenic spirochete isolate, earning that phylogenetic clade the name “gut spirochete group.” To determine the relationship between the sequence of higher termite fdhF and previously published sequences (and to guide detailed phylogenetic analyses), we constructed a phylogenetic “guide” tree (Fig. 2) based on 542 aligned amino acids in FDHH, the catalytic subunit responsible for CO2 reduction/formate oxidation in formate hydrogen lyase complexes (39).

FIG 2 .

Protein phylogeny of hydrogenase-linked formate dehydrogenases (FDHH). Sequences from the gut microbial communities of higher termites, lower termites, and wood-feeding roaches and from pure microbial cultures form four major clades (clades A, B, C, and D). Numbers in parentheses next to grouped clades denote the total number of sequences within a clade and the number of sequences recovered from higher termites. The tree was constructed with 542 ClustalW-aligned amino acids (61) and Phylip PROML (66) within the ARB software environment (65). A metagenomic sequence (IMG gene object identity no. 2004163507) from a Nasutitermes higher termite (31) was added by parsimony (253 amino acids); this fragment affiliates with the Gut Spirochete Group (clade A). Filled circles indicate nodes supported by maximum-likelihood, parsimony (PROTPARS; >60 of 100 bootstrap resamplings), and distance (Fitch) tree construction methods. The tree was out-grouped with F420-linked FDH from methanogenic Archaea (GenBank accession no. P6119, CAF29694, and ABR54514). The scale bar indicates 0.1 amino acid changes per alignment position. Accession numbers for sequences comprising grouped clades are in Table S4 in the supplemental material.

Based on 3 tree construction methods (maximum likelihood, parsimony, and distance), higher termite sequences consistently clustered into 4 major clades (labeled A to D in Fig. 2). Sequences from higher termites with diets likely predominantly consisting of lignocellulosic substrates such as wood, palm, and dried grass (74% to 100%; Table 2) grouped into the Gut Spirochete Group (clade A; Fig. 2). Similar to other environmental sequences in the Gut Spirochete Group, higher termite sequences (37 phylotypes) most probably belonged to those of uncultured acetogenic Spirochetes. The presence of a diagnostic amino acid character uniquely shared among gut spirochete group sequences supported this phylogenetic inference (37). Interestingly, sequences from litter-feeding and subterranean higher termites (8% to 51%; Table 2) formed a novel cluster, designated the “AGR group” (for Amitermes-Gnathamitermes-Rhynchotermes) (clade B [17 phylotypes]; Fig. 2). Relatively few sequences (0% to 18%; Table 2) affiliated with clade C (as shown in Fig. 2) (5 phylotypes), a group defined by proteobacterial sequences and accordingly named the “Proteobacteria group.” Clade D in Fig. 2 (3 phylotypes) was the least represented in inventories (0% to 7%; Table 2) and (like the AGR group) lacked pure culture representatives. This clade was named the “UnHT group” (for unclassified higher termite).

TABLE 2 .

Distribution of higher termite inventory sequences among four major FDHH clades (Fig. 2)

| Source insect (number of clones) |

No. of samples in indicated category |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gut spirochete | AGR | Proteobacteria | UnHT | |

| Nasutitermes sp. Cost003a (104) | 99 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Nasutitermes corniger Cost007 (30) | 86 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004a (107) | 47 | 51 | 2 | 0 |

| Microcerotermes sp. Cost006 (74) | 96 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Microcerotermes sp. Cost008 (84) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Amitermes sp. Cost010a(100) | 85 | 13 | 0 | 2 |

| Amitermes sp. JT2 (101) | 92 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Gnathamitermes sp. JT5 (84) | 74 | 8 | 18 | 0 |

Genetic extinction and evolutionary radiation within higher termite gut communities.

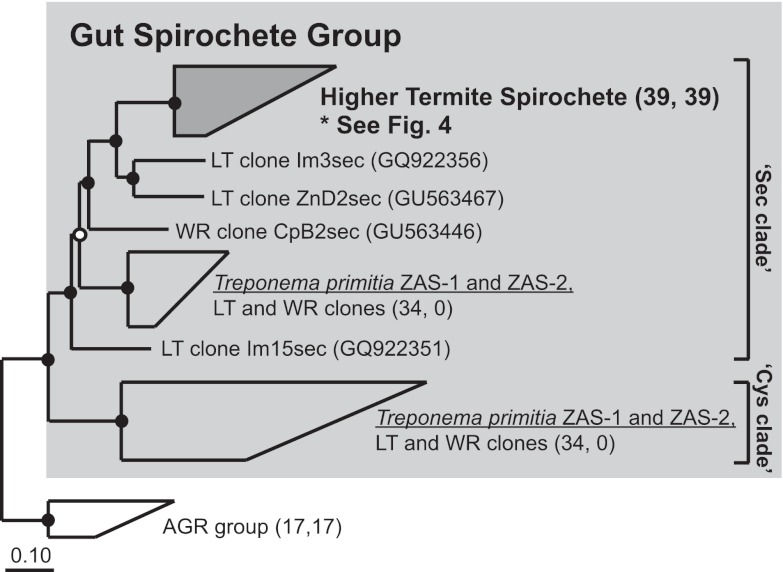

As higher termite sequences predominantly clustered into the gut spirochete group, we performed a phylogenetic analysis using 3 different treeing methods that focused on gut spirochete group sequences (Fig. 3). Unexpectedly, every higher termite sequence in this major clade group fell into a single subclade, the “higher termite spirochete” clade. This stood in striking contrast to our prior observations that fdhF genes from lower termites and wood roaches tend to form multiple, deeply branching but interspersed clades throughout the gut spirochete group. These results indicate that a large swath of fdhF diversity previously present in the guts of lower termite-like ancestors was lost from gut communities during higher termite evolution, consistent with a genetic bottleneck in the fdhF gene pool.

FIG 3 .

Protein phylogeny of Sec and Cys clade sequences within the Gut Spirochete Group of FDHH (light gray [previously clade A], Fig. 2). Higher termite sequences grouped with a metagenomic sequence from Nasutitermes (IMG gene object identity no. 2004163507) to form the “Higher Termite Spirochete” group, highlighted in dark gray. “LT” and “WR” in sequence names denote clone sequences from lower termites and wood roaches, respectively. Insect sources are denoted in the sequence name by “Zn,” “Im,” and “Cp” (Zootermopsis nevadensis, Incisitermes minor, and Cryptocercus punctulatus, respectively). Numbers of sequences within grouped clades are indicated in parentheses as described for Fig. 2. The tree was constructed with 604 ClustalW-aligned amino acids and Phylip PROML. The metagenomic sequence was added in by parsimony methods. Filled circles indicate nodes supported by maximum-likelihood, parsimony (PROTPARS; >60 of 100 bootstrap resamplings), and distance (Fitch) tree construction methods. Unfilled circles indicate nodes supported by only 2 tree construction methods. The scale bar indicates 0.1 amino acid changes per alignment position. Accession numbers for sequences in grouped clades are in Table S4 in the supplemental material.

To substantiate phylogenetic observations of genetic bottlenecking and the accompanying hypothesis of gene extinction during higher termite gut community evolution, we assayed higher termite guts for the presence of “Cys” clade fdhF, a major phylogenetic group which comprised roughly half of all fdhF variants in the guts of lower termites and wood roaches (37). Using Cys clade-specific primers (Cys499F1b, 1045R; see Text S1 in the supplemental material), we screened the gut DNA of all higher termite samples, 3 lower termite species from Southern California representing 3 termite families, and a wood-feeding roach for Cys clade genes by PCR. No product (or correctly sized product) was detected from any higher termite templates after 30 cycles of PCR amplification (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast, all amplifications from lower termite and roach gut templates yielded robust products. Bearing in mind the inherent limitations of primer-based assays, the results independently corroborate inventory data which pointed to unique sweeping losses of fdhF diversity having occurred in higher termite gut communities.

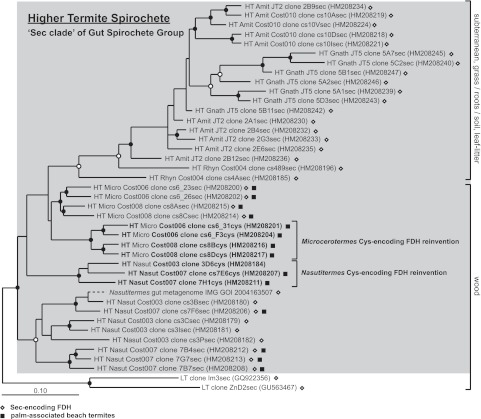

To gain insight on when such drastic culling of fdhF gene diversity might have occurred, we analyzed the phylogeny of Higher Termite Spirochete clade sequences (Fig. 4). Sequences from the most closely related higher termites clustered into shallow clades, suggesting recent coevolution between host and fdhF encoded by gut symbionts. However, sequences from higher termite species representing different subfamilies formed deeply branching clades whose branching order could not be resolved. This type of “spoke” topology in phylogenetic trees, wherein clades radiate with no resolvable order like spokes from a wheel, is typical of adaptive (or “ecological”) radiations (40). Based on uncertainties in branching order at the subfamily level, the radiation may have occurred sometime during the emergence of higher termite subfamilies. Since adaptive radiations commonly occur after massive extinctions, the major loss in fdhF diversity observed in both inventory and PCR data may have taken place earlier than subfamily diversification, possibly during the evolution of the last common ancestor (LCA) of all higher termites over 50 million years ago (15). The earliest evolved higher termites belong to the fungus-feeding subfamily Macrotermitinae (15, 33). Examining fdhF in a fungus-feeding termite should help clarify the timing of fdhF extinction.

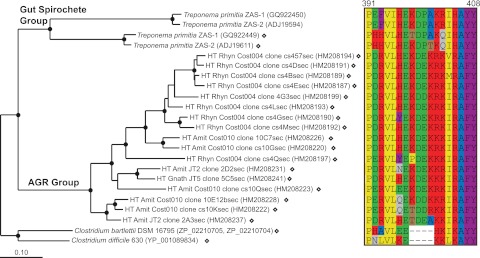

FIG 4 .

Protein phylogeny of Higher Termite Spirochete Group sequences (gray box [dark gray clade in Fig. 3]) within the Sec clade of the Gut Spirochete Group (light gray clade in Fig. 3). “HT,” “LT,” and “WR” in sequence names indicate the insect source (higher termite, lower termite, wood roach); “Cost” and “JT” refer to higher termite species from Costa Rica and California, respectively (see Table 1). Open diamonds next to sequences and “sec” in the sequence name denote selenocysteine FDHH; “cys” in the sequence name denotes a cysteine-encoding variant. Filled squares indicate sequences derived from higher termites collected at Costa Rican beaches. Sequences predicted to result from evolutionary reinventions and the likely food substrates for insects are also indicated. The tree was constructed with 604 ClustalW-aligned amino acids and Phylip PROML. The branching position of a Nasutitermes metagenomic FDHH fragment (added by parsimony using 250 amino acids) is indicated with a dashed line; thus, the phylogenetic distance represented by this dashed line is not comparable to that corresponding to any other sequence. Filled circles indicate nodes supported by PROML, parsimony (Phylip PROTPARS), and distance (Fitch) methods of tree construction. Unfilled circles indicate nodes supported by 2 of 3 tree construction methods. The scale bar corresponds to 0.1 amino acid changes per alignment position. GenBank accession numbers are in parentheses.

“Chain of extinction” hypothesis: disappearance of H2-producing protists and H2-consuming dependents.

Given that the fdhF gene extinction event (or events) occurred during time periods relevant to the LCA of higher termites, the most plausible cause of fdhF extinction would seem to relate to another extinction that transpired in the same time period: the extinction of H2-producing gut protozoa. While these links are circumstantial, the link between fdhF and protozoa also makes functional sense. A dramatic extinction of primary H2 producers (leading to a shift in niche occupancy) in the lower termite-like LCA would undoubtedly propagate down the microbial “food chain” to H2-consuming symbionts such as H2-consuming acetogens that possess fdhF. The result of this propagation could manifest itself in extant higher termites in one of two ways: (i) a dramatic shift in the abundance of H2-consuming symbionts (and their fdhF genes) relative to that found in less-derived termites or (ii) a dramatic loss of diversity. Our results support the latter scenario, implying that the consequences of protozoon extinction for symbionts (and their genes) lying “downstream” in H2 metabolism were more wave-like than ripple-like.

Not all genes, however, went extinct. Those that survived waves of extinction underwent an explosive radiation to fill out previously occupied niches. We posit that their genetic descendants form the Higher Termite Spirochete Group.

The data also provide circumstantial support for a previous hypothesis on the nature of association between certain protozoa and ectosymbiotic Spirochetes. Leadbetter et al. (41) proposed an H2-based symbiosis to explain the presence of Spirochetes attached to protozoon surfaces. The results described here strengthen the consequent implication that some ectosymbiotic Spirochetes may be acetogenic and also draw attention to unexplored metabolic dependencies between protists and free-living Spirochetes that may not require physical proximity.

Selenium dynamics: sweeping gene extinction followed later by occasional convergent evolution.

Our previous study of Gut Spirochete Group FDHH from the guts of less-derived wood-feeding insects revealed two functional enzyme variants differing in a key catalytic residue (Fig. 3) (37). “Sec” clade sequences have been predicted to encode enzymes that contain the trace element selenium in the form of selenocysteine at the active site. In contrast, Cys clade sequences generally encode selenium-independent variants containing cysteine, instead of selenocysteine, at the active site. Study of T. primitia (38) and other organisms (42–44) that possess dual-enzyme variants indicates that organisms switch to using their selenium-independent enzymes under conditions of selenium limitation.

In higher termites, the striking absence of Cys clade gene variants implied that some selective pressure related to selenium limitation was relaxed in higher termite gut communities, such that genes for selenium-independent enzymes were lost by genome reduction from symbiont genomes. An alternative explanation was that the characteristic absence of Cys clade genes in higher termites related to sampling differences between studies. To address this concern, we collected 2 lower termite species from the same habitats as a subset of higher termites (Costa Rican lower termite Coptotermes sp. Cost009 collected near Microcerotermes sp. Cost006 and Cost008; desert-adapted lower termite Reticulitermes tibialis JT1 collected near higher termite species Amitermes sp. JT1 and Gnathamitermes sp. JT5) and performed PCR screening on whole-gut community DNA with Cys clade-specific primers. Correctly sized PCR amplicons were observed for all lower termites, regardless of where they were collected (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), to independently support inventory data. Thus, the absence of Cys clade genes is a characteristic feature of higher termite gut microbial communities, rather than a result of sampling differences.

To further explore the dependence of higher termite FDHH on selenium (a trace nutrient whose bioavailability varies with redox state [45, 46]), we inspected every higher termite Sec clade FDHH sequence for the selenocysteine amino acid. We discovered that several sequences from Costa Rican higher termites actually include selenium-independent FDHH (clones cs6_31cys, cs6_F3cys, cs8Bcys, cs8Dcys, 3D6cys, cs7E6cys, and 7H1cys). Since these cysteine-containing FDHH variants were nested within the Sec clade, they must have originated from the duplication of a selenium-dependent FDHH gene followed by mutational modification of the active site selenocysteine into cysteine. Also of note is the clustering of instances of Microcerotermes cysteine-containing FDHH with each other (Fig. 4), to the exclusion of cysteine FDHH from Nasutitermes. This result points to two independent gene duplication events, each of which has resulted in the “reinvention” (or convergent evolution) of a selenium-independent FDHH gene from Sec clade FDHH gene stock in termites. To our knowledge, these data provide the first examples of convergent evolution by symbiotic gut microbes in the termite gut.

The forces that have selected for convergent evolution are intriguing. One possibility is that the selenium content of the termite’s diet may vary enough to affect selenium bioavailability in the gut tract and thus select for one or the other gene variant. This hypothesis stems from the observation that the majority of reinvented cysteine variants (Fig. 4) were identified in termites collected from palm trees in beach areas where plants are regularly submerged in seawater. Estimates of total selenium concentrations in the surface mixed layers of the ocean are 4 orders of magnitude lower than estimates of concentrations in surface soils (47). Thus, seawater may flush selenium from beach soil, reducing selenium levels in plants and consequently in the diet of termites. But even if dietary selenium levels drove convergent evolution, the larger question of why selenium-dependent FDHH genes are favored over selenium-independent variants in higher termites remains unanswered. Perhaps a structural aspect of the gut tract in higher termites makes the same amount of selenium more easily bioavailable in higher termite than in lower termite guts. Perhaps behavioral innovations relating to, e.g., increased and more effective grazing for nutrients are at play. The continued study of selenium biology and chemistry in termite guts, and of the termites in which they reside, should provide further insight into such possibilities.

Recent gene invasion into subterranean and litter-feeding higher termite gut communities.

Gut preparations from subterranean (Amitermes sp. Cost010, Amitermes sp. JT2, and Gnathamitermes sp. JT5) and litter-feeding (Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004) higher termites featured a novel clade of FDHH absent in other termites (clade B in Fig. 2). Figure 5 shows the detailed phylogeny of AGR group sequences. Since we could not infer the identity of uncultured organisms encoding these sequences from phylogeny, we inspected the sequences for possible indel signatures. Indeed, AGR sequences contained an amino acid indel (Fig. 5, right panel) similar to that previously observed in Gut Spirochete Group sequences, weakly suggesting a spirochetal origin for AGR group genes (or for that indel).

FIG 5 .

Protein phylogeny (left panel) and amino acid character (right panel) analysis of AGR group sequences (clade B, Fig. 2). In the left panel, sequences from T. primitia represent the gut spirochete group (clade A, Fig. 2). Open diamonds located next to sequences and clone names containing “sec” denote selenocysteine FDHH; unmarked sequences denote cysteine-encoding FDHH. The tree was constructed with 595 ClustalW-aligned amino acids using Phylip PROML. Filled circles indicate nodes supported by PROML, parsimony (Phylip PROTPARS), and distance (Fitch) methods of analyses. The scale bar indicates 0.1 amino acid changes per alignment position. In the right panel, numbers above the alignment refer to amino acid positions in the selenocysteine FDHH of T. primitia sp. ZAS-2 (ADJ19611). Canonical amino acid one-letter coding applies. Amino acids are colored based on shared physical-chemical characteristics: yellow/hydrophobic, blue/small, brown/nucleophilic, purple/aromatic, green/acidic, red/basic, gray/amide.

We hypothesized that AGR group genes might be diagnostic markers for subterranean and litter-feeding higher termite diets and behaviors. To test this hypothesis, we designed AGR clade-specific primers (AGR193F, 1045R; see Text S1 in the supplemental material). We screened lower and higher termite gut DNA templates using nested PCR methods (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Robust amplicons were consistently detected in every subterranean and litter-feeding higher termite but not in arboreal higher termites, lower termites, or Cryptocercus punctulatus, supporting the conjecture that AGR group alleles are characteristic of subterranean and litter-feeding higher termite gut communities.

To understand why AGR group sequences would be present in only a subset of higher termites, we compared the relative abundances of AGR sequences (Table 2) with the host’s predicted diet (Table 1). AGR sequences represented the most abundant phylotype in leaf litter-feeding termites (51%; Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004) but appeared at lower frequencies (8% to 13%) in subterranean termites with diets containing monocots (such as sugarcane roots, grass, and Yucca) and were not recovered from termites feeding on wood. Based on tannin levels reported for bark, leaves, and wood (48), the presence of AGR group sequences may positively relate to dietary tannin levels and represent a novel marker for an as-yet-unappreciated group of uncultured acetogens, perhaps ones that exhibit greater tolerance to phenolic compounds such as tannin. Alternatively, they may represent a group of nonacetogenic, tannin-tolerant, heterotrophic bacteria that ferment residual sugars in decaying leaves and employ the enzyme in direction of formate oxidation, perhaps in concert with nonacetogenic formyl-tetrahydrofolate synthetase genes inventoried from the guts of litter and subterranean higher termites (49). In any case, the phylogenetic remoteness of the AGR group from other major FDH clades suggests that a niche that was previously small (or absent) in wood-feeding termites gained importance in higher termites that feed on decaying plant materials that have substantial contact with soil.

The basal location of subterranean termite sequences (Fig. 5) hints that the influx of AGR-type gene stock into gut communities occurred in a termite belonging to the Termitinae subfamily and that such genes may have been laterally transferred into the Nasutitermitinae. It remains to be determined whether the initial influx manifested itself as the lateral transfer of AGR genes from an organism passing through the gut to an established gut symbiont or as the invasive establishment of a novel group of gut symbionts. Indeed, complex phylogenetic relationships between spirochete rRNA genes and host termites (50, 51) which are not strictly cocladogenic imply that acquisition of gut symbionts has been ongoing during termite evolution, a concept outlined previously (52, 53). However, these events most likely occurred in the very distant past, as there is also strong evidence in support of the idea of broad levels of spirochete coevolution with lower termites (21). The select presence of AGR-type genes in litter and subterranean higher termite guts suggests a more recent acquisition in the evolutionary history of this successful lineage of termite hosts.

PCA: the past shapes most of the present.

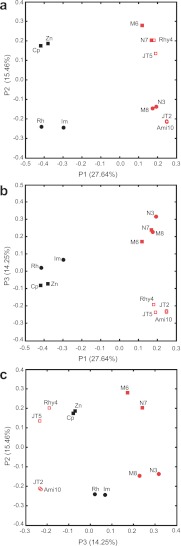

To quantify the importance of different factors associated with FDHH phylogeny, we performed a principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig. 6) using UniFrac phylogeny statistics software (54). The first principal component (P1 [27.64% of total variance]; Fig. 6a and b) clearly separates lower termite and wood roach inventories from the higher termite inventories, a result consistent with P1 tracking the presence (lower termite, wood roach) or absence (higher termite) of flagellate protozoa in gut communities. This result supports our hypothesis that fdhF gene extinction results from protozoal extinctions. The second (Fig. 6a and c) and third (Fig. 6b and c) principal components accounted for similar levels of variance (15.46% and 14.25%). P2 clustered inventories containing Protobacteria clade sequences, whereas P3 grouped those containing AGR clade sequences. The latter grouping supports the idea that dietary variables (amount of soil and form of lignocellulose in diet) also play roles in shaping gut communities (55–57). PCA did not appear to cluster the data on the basis of geography, nest type, or habitat—the diversity of which was considerable in the sampled species. Based on these data, the transition from lower termite body and gut community plans to the higher termite forms seems to far outweigh in importance other variables for shaping fdhF diversity in higher termites. This is consistent with the notion that the signal imprinted long ago in fdhF sequence diversity in higher termites was the mass extinction of protozoa during their transition.

FIG 6 .

UniFrac principal component analysis of FDHH phylogeny associated with the gut microbial communities of termites and related insects. For species of wood roach and lower termites, Cp represents C. punctulatus; Zn, Z. nevadensis; Rh, R. hesperus; and Im, I. minor. For species of higher termites, N3 represents Nasutitermes sp. Cost003; N7, Nasutitermes corniger Cost007; M6, Microcerotermes sp. Cost006; M8, Microcerotermes sp. Cost008; Rhy4, Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004; A10, Amitermes sp. Cost010; Jt2; Amitermes sp. JT2; and Jt5, Gnathamitermes sp. JT5. Black shapes represent lower termite and wood roach inventories; red shapes, higher termite inventories; squares, inventories containing Proteobacteria group sequences; open shapes, inventories containing AGR group sequences. The tree in Fig. 2 was analyzed with UniFrac (termite species as the environment variable; 100 permutations).

Model for fdhF evolution in wood-feeding dictyopteran insects.

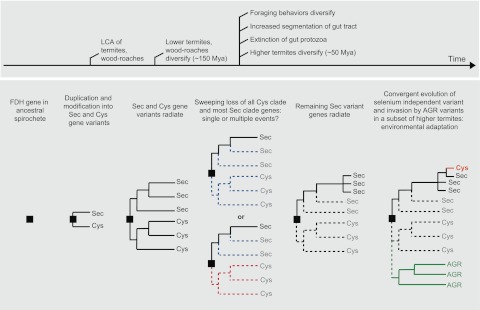

Based on our findings, we constructed a schematic modeling the evolutionary trajectory of fdhF in the guts of wood-feeding insects, beginning with fdhF in the LCA of termites and wood-feeding cockroaches and continuing to the present day (Fig. 7). The evolutionary sequence highlights the importance of past extinction events as key determinants of present diversity. Previous data (37) imply that a spirochete member of the gut community within the LCA of termites and roaches possessed an ancestral fdhF gene, which underwent duplication and mutational modification into selenocysteine- and cysteine-encoding forms. These two functional variants of fdhF then coradiated with gut communities and the host insects as wood-feeding insects were diversifying into termite and roach forms to create the “Sec” and “Cys” clades. Here we have documented a severe trimming of Sec clade diversity and complete loss of all Cys clade genes. We estimate that this occurred during the emergence of the higher termite line, when guts became segmented, foraging behaviors diversified, and cellulolytic protozoa went extinct from the gut community. It is unclear whether losses of Sec and Cys clade genes represent single or multiple extinction events. In any case, genes surviving extinction radiated to fill the newly emptied (or created) niches within higher termite guts. In particular, the convergent evolution of selenium-independent fdhF suggests an adaptive radiation into selenium-limited niches that have recently become available in a subset of higher termites. It also appears that some aspect of litter-feeding and subterranean lifestyles has allowed the more recent establishment of a novel clade of fdhF, possibly reflecting an invasion by non-gut-adapted species.

FIG 7 .

Inferred evolutionary history for fdhF in the symbiotic gut microbial communities of lignocellulose-feeding insects.

Conclusions.

The overarching goal of this study was to understand how symbiont communities and their genes have been impacted by drastic change and other perturbations over evolutionary time scales. We accomplished this goal using the obligate nutritional mutualism between termites and their hindgut microbial communities as a “backdrop” for an evolutionary case study of symbiosis. Comparative analysis of a symbiont metabolic gene unveiled a striking implication for evolutionary biology in complex microbial communities wherein the metabolisms of community members form a network of dependent interactions: collapse of a functional population (or network node) within a symbiont community can have dramatic and long-lasting effects on the genes carried by symbionts occupying niches downstream in the chain of community metabolism.

Connectivity and adaptation are themes that have emerged from this study of symbiont communities. The challenge now is to understand the specific interactions on which connectivity was based in the distant past. Studying the genes and organisms involved in present-day interactions between specific microbes within termite gut communities should give us clues to how the past has shaped and continues to shape the present.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Insect collection and classification.

Details on insect collection can be found in Ottesen and Leadbetter (49). Briefly, termite species obtained by permit in Costa Rica were Nasutitermes sp. Cost003, collected from the National Biodiversity Institute of Costa Rica (INBio) forest; Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004, from leaf litter within INBio; Amitermes sp. Cost010, from soil-encrusted decayed sugar cane at a sugar cane plantation in Grecia; Nasutitermes corniger Cost007, Microcerotermes spp. Cost006 and Cost008, from unidentified species of palm growing at a beach in Cahuita National Park (CNP); and Coptotermes sp. Cost009 (lower termite, family Rhinotermitidae), from wood near CNP’s Kelly Creek Ranger Station. Termites species obtained under a U.S. Park Service research permit from Joshua Tree National Park, CA, were Amitermes sp. JT2 and Gnathamitermes sp. JT5, collected from subterranean nests, and Reticulitermes tibialis JT1 (lower termite, family Rhinotermitidae), collected from a decayed log in a dry stream bed.

Termites were identified based on the gene sequence of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase 2 (COII; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and on morphology. In general, inadequate COII sequence data prevented taxonomic assignments past the genus level. Genus names for Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004 and Gnathamitermes sp. JT5 specimens were assigned based on head and mandible morphology and collection location. COII analyses confirmed that the 8 termite species examined in this study represented distinct lineages in the subfamilies Nasutitermitinae and Termitinae. Classification of termite habitats was based on the Holdridge life zone classification of land areas (58) and life zone maps in references 59 and 60.

DNA extraction.

For each termite species, the entire hindguts of 20 worker termites were extracted within 48 h of collection, pooled into 500 µl 1× Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8), and stored at −20°C until DNA extraction. Whole-gut community DNA was obtained using the method described in reference 61.

fdhF amplification and cloning.

PCR mixtures containing universal fdhF primers (1 µM of each degenerate form) (37) were assembled with 1× FAILSAFE Premix D (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI). Polymerase (EXPAND High Fidelity polymerase; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) (0.07 to 0.14 U µl−1) and gut DNA template (0.05 to 1 ng µl−1) concentrations were adjusted so that reactions would yield similar amounts of PCR product. Thermocycling conditions for PCR performed using a Mastercycler Model 5331 thermocycler (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY) were 2 min at 94°C, 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 51°C, 53.6°C, or 55°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 2 min 30 s, and 10 min at 68°C. Details on PCR are presented in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Annealing amplifications at 51°C yielded products of multiple sizes upon gel electrophoresis with 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The correctly sized bands were excised and gel purified with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). To ensure product specificity, PCR was performed at higher annealing temperatures (53.6°C for Microcerotermes sp. Cost008 and Amitermes sp. Cost010 and 55°C for Nasutitermes sp. Cost003 and Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004). These reactions yielded single product bands upon electrophoresis. All PCR products were cloned using a TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Clones (30 to 107 per termite species) were screened for the presence of the correctly sized insert by PCR and gel electrophoresis. PCR mixtures contained T3 (1 µM) and T7 (1 µM) primers, 1× FailSafe PreMix D (Epicentre), 0.05 U µl−1 Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), and 1 µl of cells in 1× TE buffer as the template. Thermocycling conditions were 2 min at 95°C, 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min 30 s, and 10 min at 72°C. Primer design and PCR amplifications of Cys and AGR group fdhF genes are described in Text S1 in the supplemental material.

RFLP analysis, sequencing, and diversity assessment.

Most inventories were subjected to restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) typing, wherein correct-sized products generated by screening PCRs were digested with the restriction enzyme RsaI (New England Biolabs) and electrophoresed on a 2.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel (Invitrogen). Plasmids from clones with unique RFLP patterns were purified using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen). For Nasutitermes sp. Cost003, Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004, and Amitermes sp. Cost010 inventories, generated at an annealing temperature of 51°C, plasmids from clones having the correct-sized products were purified for sequencing without RLFP typing. Plasmids were sequenced with T3 and T7 primers at Laragen, Inc. (Los Angeles, CA) using an Applied Biosystems Incorporated ABI3730 automated sequencer. Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, WI) was used to assemble and edit sequences. Sequences were aligned with ClustalW (62), manually adjusted, and grouped into operational taxonomic units at a 97% protein similarity level based on distance calculations (Phylip Distance Matrix, Jones-Thornton-Taylor correction) and DOTUR (63). The program EstimateS v8.2.0 (36) was used to assess inventory diversity and completeness.

COII amplification for termite identification.

Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit II (COII) gene fragments from Costa Rican termites were amplified from DNA containing both insect and gut community material using primers A-tLEU and B-tLYS and the protocol described by Miura et al. (64, 65). COII gene fragments from Californian termites were amplified using the supernatant of a mixture containing an individual termite head crushed in 1× TE buffer as the template. Primers and PCR conditions were identical to those employed for Costa Rican termite COII. PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), sequenced, and analyzed to verify the identity of termite specimens.

Phylogenetic and principal component analysis.

Phylogenetic analyses of protein and nucleotide sequences were performed with ARB version 09.08.29 (66). Details of tree construction can be found in the figure legends. In general, the trees show results from Phylip PROML analysis; node robustness was analyzed with PROTPARS and Fitch distance methods as well (67). The same filter and alignments were employed when additional tree algorithms were used to infer node robustness. All phylogenetic inference models were run while assuming a uniform rate of change for each nucleotide or amino acid position. Principal component analysis of FDHH phylogeny and environment data was performed using Unifrac software (54).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

GenBank accession numbers for sequences determined during this study are listed in Table S4 in the supplemental material.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental methods.Text S1, DOCX file, 0.1 MB.

Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase II (COII) phylogeny of termites and related roaches. Family names and other descriptions are located on the right side of the tree. Only two of four subfamilies (Macrotermitinae, Apicotermitinae, Nasutitermitinae, and Termitinae) in the Termitidae higher termite family are shown. Subfamily Termitinae is paraphyletic (1). The gut communities of insect species highlighted in red have been examined for fdhF using inventory and/or PCR screening techniques. The tree was constructed with 393 aligned nucleotides using the maximum-likelihood phylogenetic algorithm AxML (2). Filled circles at nodes indicate support from PHYML, parsimony (Phylip DNAPARS), and Fitch distance methods. The scale bar corresponds to 0.1 nucleotide changes per alignment position. Download Figure S1, PDF file, 1.1 MB.

Targeted PCR assays on termite and roach gut DNA using Cys-clade specific fdhF primers (Cys499F1b, 1045R), which yield a ca. 600-bp product (ladder in left lane, NEB 2-log). The templates were ZAS-2, corresponding to T. primitia sp. strain ZAS-2 genomic DNA; Zn, Z. nevadensis; Rh, R. hesperus; Im, I. minor; Cp, C. punctulatus; JT1, R. tibialis; cs9, Coptotermes sp. Cost009; cs3, Nasutitermes sp. Cost003; cs4, Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004; cs6, Microcerotermes sp. Cost006; cs7, Nasutitermes corniger Cost007; cs8, Microcerotermes sp. Cost008; cs10, Amitermes sp. Cost010; JT2, Amitermes sp. JT2; and JT5, Gnathamitermes sp. JT5. Numbers in ZAS-2 genomic lanes refer to the number of genome copies per reaction. Copy numbers (106 copies/gut) from the lower termite Z. nevadensis were estimated from band strength in dilution-to-extinction PCR of T. primitia ZAS-2 DNA (assuming a yield of 1 μg total DNA/gut as typically observed in Qiagen DNA extractions, 10% derived from prokaryotes, and 104 copies/ng gut DNA in Z. nevadensis). As correctly sized Cys bands were not present in the higher termites, the detection limit (100 copies/ng gut DNA) was used to estimate a maximum abundance of 103 copies/gut for lower termite Cys clade FDH genes in higher termites (assuming a yield of 0.25 μg total DNA/gut, 100% derived from prokaryotes). Download Figure S2, PDF file, 0.2 MB.

Products from nested PCRs using (i) universal fdhF primers followed by (ii) Amitermes-Gnathamitermes-Rhychotermes clade-specific primers on gut templates. A NEB 2-log ladder was used. See Fig. S2 for template designations. A slight band in lane Zn was observed inconsistently and infrequently and is attributed to contamination during nested PCR. Download Figure S3, PDF file, 0.2 MB.

fdhF inventories constructed in this study.

PCR conditions for clone library construction.

Composition of higher termite fdhF inventories.

Sequences used in phylogenetic analyses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant EF-0523267 and Department of Energy grant DE-FG02-07ER64484 to J.R.L. and a National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship to X.Z.

We thank members of the Leadbetter laboratory for their helpful discussions and comments. We are grateful for the aid of Myriam Hernández, Luis G. Acosta, Giselle Tamayo, and Catalina Murillo of the Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (Santo Domingo de Heredia, Costa Rica) and Brian Green, Cathy Chang, and Eric J. Mathur, formerly of Verenium, Inc., in termite collection and site access. Termites from Joshua Tree National Park were collected under permit JOTR-2008-SCI-0002.

All authors participated in insect collection. X.Z. and J.R.L. conceived of the experiments. X.Z. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. X.Z. and J.R.L. wrote the manuscript.

The authors have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Citation Zhang X, Leadbetter JR. 2012. Evidence for cascades of perturbation and adaptation in the metabolic genes of higher termite gut symbionts. mBio 3(4):e00223-12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00223-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai MJ, Relman DA. 2007. An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human–microbe mutualism and disease. Nature 449:811–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Wees SC, Van der Ent S, Pieterse CM. 2008. Plant immune responses triggered by beneficial microbes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11:443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McFall-Ngai MJ. 2002. Unseen forces: the influence of bacteria on animal development. Dev. Biol. 242:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moran NA, Telang A. 1998. Bacteriocyte-associated symbionts of insects. Bioscience 48:295–304 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen X, Li S, Aksoy S. 1999. Concordant evolution of a symbiont with its host insect species: molecular phylogeny of genus Glossina and its bacteriome-associated endosymbiont, Wigglesworthia glossinidia. J. Mol. Evol. 48:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moran NA, Baumann P. 2000. Bacterial endosymbionts in animals. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:270–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baumann P, Moran NA, Baumann L. 2006. Bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts of insects, p. 403–438 In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E, The prokaryotes, vol. 1 Springer Verlag, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu D, et al. 2006. Metabolic complementarity and genomics of the dual bacterial symbiosis of sharpshooters. PLoS Biol. 4:e188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buchner P. 1965. Endosymbiosis of animals with plant microorganisms. Interscience, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mira A, Ochman H, Moran NA. 2001. Deletional bias and the evolution of bacterial genomes. Trends Genet. 17:589–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moran NA. 2002. Microbial minimalism: genome reduction in bacterial pathogens. Cell 108:583–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wernegreen JJ. 2002. Genome evolution in bacterial endosymbionts of insects. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3:850–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moran NA, McLaughlin HJ, Sorek R. 2009. The dynamics and time scale of ongoing genomic erosion in symbiotic bacteria. Science 323:379–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shigenobu S, Watanabe H, Hattori M, Sakaki Y, Ishikawa H. 2000. Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS. Nature 407:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grimaldi D, Engel MS. 2005. Evolution of the insects. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nalepa C, Bandi C. 2000. Characterizing the ancestors: paedomorphosis and termite evolution, p. 53–77 In Abe T, Bignell DE, Higashi M, Termites: evolution, sociality, symbioses, ecology. Kluwer Publishers Academic, Dordrecht, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lo N, Eggleton P. 2011. Termite phylogenetics and co-cladogenesis with symbionts, p. 27–50 In Bignell DE, Roisin Y, Lo N., Biology of termites: a modern synthesis. Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brune A, Stingl U. 2006. Prokaryotic symbionts of termite gut flagellates: phylogenetic and metabolic implications of a tripartite symbiosis. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 41:39–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ohkuma M, Noda S, Hongoh Y, Nalepa CA, Inoue T. 2009. Inheritance and diversification of symbiotic trichonymphid flagellates from a common ancestor of termites and the cockroach Cryptocercus. Proc. Biol. Sci. 276:239–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noda S, Kitade O, Inoue T, Kawai M, Kanuka M. 2007. Cospeciation in the triplex symbiosis of termite gut protists (Pseudotrichonympha spp.), their hosts, and their bacterial endosymbionts. Mol. Ecol. 16:1257–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berlanga M, Paster BJ, Guerrero R. 2007. Coevolution of symbiotic spirochete diversity in lower termites. Int. Microbiol. 10:133–139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hongoh Y, et al. 2005. Intra- and interspecific comparisons of bacterial diversity and community structure support coevolution of gut microbiota and termite host. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6590–6599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Desai MS, et al. 2010. Strict cospeciation of devescovinid flagellates and Bacteroidales ectosymbionts in the gut of dry-wood termites (Kalotermitidae). Environ. Microbiol. 12:2120–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hongoh Y, Ohkuma M, Kudo T. 2003. Molecular analysis of bacterial microbiota in the gut of the termite Reticulitermes speratus (Isoptera; Rhinotermitidae). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 44:231–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang H, Schmitt-Wagner D, Stingl U, Brune A. 2005. Niche heterogeneity determines bacterial community structure in the termite gut (Reticulitermes santonensis). Environ. Microbiol. 7:916–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Odelson DA, Breznak JA. 1983. Volatile fatty acid production by the hindgut microbiota of xylophagous termites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45:1602–1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Breznak JA, Switzer JM. 1986. Acetate synthesis from H2 plus CO2 by termite gut microbes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:623–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brauman A, Kane MD, Labat M, Breznak JA. 1992. Genesis of acetate and methane by gut bacteria of nutritionally diverse termites. Science 257:1384–1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pester M, Brune A. 2007. Hydrogen is the central free intermediate during lignocellulose degradation by termite gut symbionts. ISME J. 1:551–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eggleton P. 2006. The termite gut habitat: its evolution and co-evolution, p. 373–404 In König H, Varma A, Intestinal microorganisms of termites and other invertebrates. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brugerolle G, Radek R. 2006. Symbiotic protozoa of termites, p. 244–269 In König H, Varma A, Intestinal microorganisms of termites and other invertebrates. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eggleton P, et al. 1996. The diversity, abundance and biomass of termites under differing levels of disturbance in the Mbalmayo forest reserve, Southern Cameroon. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 351:51–68 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Engel MS, Grimaldi DA, Krishna K. 2009. Termites (Isoptera): their phylogeny, classification, and rise to ecological dominance. Am. Mus. Novit. 3650:1–27 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kambhampati S, Eggleton P. 2000. Taxonomy and phylogeny of termites, p. 1–24 In Abe T, Bignell DE, Higashi M, Termites: evolution, sociality, symbioses, ecology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 35. Warnecke F, et al. 2007. Metagenomic and functional analysis of hindgut microbiota of a wood-feeding higher termite. Nature 450:560–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Colwell RK. 2009. EstimateS: statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples, version 8.2.0. http://viceroy.eeb.uconn.edu/EstimateS

- 37. Zhang X, Matson EG, Leadbetter JR. 2011. Genes for selenium dependent and independent formate dehydrogenase in the gut microbial communities of three lower, wood-feeding termites and a wood-feeding roach. Environ. Microbiol. 13:307–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Matson EG, Zhang X, Leadbetter JR. 2010. Selenium controls transcription of paralogous formate dehydrogenase genes in the termite gut acetogen, Treponema primitia. Environ. Microbiol. 12:2245–2258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zinoni F, Birkmann A, Stadtman TC, Böck A. 1986. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the selenocysteine-containing polypeptide of formate dehydrogenase (formate-hydrogen-lyase-linked) from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:4650–4654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sudhaus W. 2004. Radiation within the framework of evolutionary ecology. Org. Divers. Evol. 4:127–134 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Leadbetter JR, Schmidt TM, Graber JR, Breznak JA. 1999. Acetogenesis from H2 plus CO2 by spirochetes from termite guts. Science 283:686–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jones JB, Stadtman TC. 1981. Selenium-dependent and selenium-independent formate dehydrogenases of Methanococcus vannielii. Separation of the two forms and characterization of the purified selenium-independent form. J. Biol. Chem. 256:656–663 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Valente FM, et al. 2006. Selenium is involved in regulation of periplasmic hydrogenase gene expression in Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J. Bacteriol. 188:3228–3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vorholt JA, Vaupel M, Thauer RK. 1997. A selenium-dependent and a selenium-independent formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase and their transcriptional regulation in the hyperthermophilic Methanopyrus kandleri. Mol. Microbiol. 23:1033–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fishbein L. 1983. Environmental selenium and its significance. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 3:411–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Masscheleyn PH, Delaune RD, Patrick WH. 1990. Transformations of selenium as affected by sediment oxidation-reduction potential and pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 24:91–96 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nriagu JO. 1989. Global cycling of selenium, p. 327–340 In Ihnat M, Occurrence and distribution of selenium. CRC Press, Boca Baton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hernes PJ, Hedges JI. 2004. Tannin signatures of barks, needles, leaves, cones, and wood at the molecular level. Geochem. Cosmochem. Acta 68:1293–1307 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ottesen EA, Leadbetter JR. 2011. Formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase gene diversity in the guts of higher termites with different diets and lifestyles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:3461–3467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ohkuma M, Iida T, Kudo T. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships of symbiotic spirochetes in the gut of diverse termites. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 181:123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lilburn TG, Schmidt TM, Breznak JA. 1999. Phylogenetic diversity of termite gut spirochaetes. Environ. Microbiol. 1:331–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ohkuma M, Hongoh Y, Kudo T. 2006. Diversity and molecular analyses of yet-uncultivated microorganisms, p. 303–317 In König H, Varma A, Intestinal microorganisms of termites and other invertebrates. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 53. Breznak JA, Leadbetter JR. 2006. Termite gut spirochetes, p. 318–329 In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenber E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E, The prokaryotes, vol. 7 Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lozupone C, Knight R. 2005. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8228–8235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Miyata R, et al. 2007. Influence of feed components on symbiotic bacterial community structure in the gut of the wood-feeding higher termite Nasutitermes takasagoensis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71:1244–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brauman A, et al. 2001. Molecular phylogenetic profiling of prokaryotic communities in guts of termites with different feeding habits. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 35:27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yamada A, Inoue T, Noda S, Hongoh Y, Ohkuma M. 2007. Evolutionary trend of phylogenetic diversity of nitrogen fixation genes in the gut community of wood-feeding termites. Mol. Ecol. 16:3768–3777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Holdridge LR, Grenke WC, Hatheway WH, Tosi JA. 1971. Forest environments in tropical life zones. A pilot study. Pergamon Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Enquist CAF. 2002. Predicted regional impacts of climate change on the geographical distribution and diversity of tropical forests in Costa Rica. J. Biogeogr. 29:519–534 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lugo AE, Brown SL, Dodson R, Smith TS, Shugart HH. 1999. The Holdridge life zones of the conterminous United States in relation to ecosystem mapping. J. Biogeogr. 26:1025–1038 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Matson EG, Ottesen E, Leadbetter JR. 2007. Extracting DNA from the gut microbes of the termite (Zootermopsis nevadensis). J. Vis. Exp. 4:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Larkin MA, et al. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schloss PD, Handelsman J. 2005. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1501–1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Miura T, Roisin Y, Matsumoto T. 2000. Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of the nasute termite genus Nasutitermes (Isoptera: Termitidae) in the Pacific tropics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 17:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Miura T, Maekawa K, Kitade O, Abe T, Matsumoto T. 1998. Phylogenetic relationships among subfamilies in higher termites (Isoptera: Termitidae) based on mitochondrial COII gene sequences. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 91:515–521 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ludwig W, et al. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Felsenstein J. 1989. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2). Cladistics 5:164–166 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental methods.Text S1, DOCX file, 0.1 MB.

Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase II (COII) phylogeny of termites and related roaches. Family names and other descriptions are located on the right side of the tree. Only two of four subfamilies (Macrotermitinae, Apicotermitinae, Nasutitermitinae, and Termitinae) in the Termitidae higher termite family are shown. Subfamily Termitinae is paraphyletic (1). The gut communities of insect species highlighted in red have been examined for fdhF using inventory and/or PCR screening techniques. The tree was constructed with 393 aligned nucleotides using the maximum-likelihood phylogenetic algorithm AxML (2). Filled circles at nodes indicate support from PHYML, parsimony (Phylip DNAPARS), and Fitch distance methods. The scale bar corresponds to 0.1 nucleotide changes per alignment position. Download Figure S1, PDF file, 1.1 MB.

Targeted PCR assays on termite and roach gut DNA using Cys-clade specific fdhF primers (Cys499F1b, 1045R), which yield a ca. 600-bp product (ladder in left lane, NEB 2-log). The templates were ZAS-2, corresponding to T. primitia sp. strain ZAS-2 genomic DNA; Zn, Z. nevadensis; Rh, R. hesperus; Im, I. minor; Cp, C. punctulatus; JT1, R. tibialis; cs9, Coptotermes sp. Cost009; cs3, Nasutitermes sp. Cost003; cs4, Rhynchotermes sp. Cost004; cs6, Microcerotermes sp. Cost006; cs7, Nasutitermes corniger Cost007; cs8, Microcerotermes sp. Cost008; cs10, Amitermes sp. Cost010; JT2, Amitermes sp. JT2; and JT5, Gnathamitermes sp. JT5. Numbers in ZAS-2 genomic lanes refer to the number of genome copies per reaction. Copy numbers (106 copies/gut) from the lower termite Z. nevadensis were estimated from band strength in dilution-to-extinction PCR of T. primitia ZAS-2 DNA (assuming a yield of 1 μg total DNA/gut as typically observed in Qiagen DNA extractions, 10% derived from prokaryotes, and 104 copies/ng gut DNA in Z. nevadensis). As correctly sized Cys bands were not present in the higher termites, the detection limit (100 copies/ng gut DNA) was used to estimate a maximum abundance of 103 copies/gut for lower termite Cys clade FDH genes in higher termites (assuming a yield of 0.25 μg total DNA/gut, 100% derived from prokaryotes). Download Figure S2, PDF file, 0.2 MB.

Products from nested PCRs using (i) universal fdhF primers followed by (ii) Amitermes-Gnathamitermes-Rhychotermes clade-specific primers on gut templates. A NEB 2-log ladder was used. See Fig. S2 for template designations. A slight band in lane Zn was observed inconsistently and infrequently and is attributed to contamination during nested PCR. Download Figure S3, PDF file, 0.2 MB.

fdhF inventories constructed in this study.

PCR conditions for clone library construction.

Composition of higher termite fdhF inventories.

Sequences used in phylogenetic analyses.