Summary

Bacteria isolated from marine sponges, including the Silicibacter-Ruegeria (SR) subgroup of the Roseobacter clade, produce N-acylhomoserine lactone (AHL) quorum sensing signal molecules. This study is the first detailed analysis of AHL quorum sensing in sponge-associated bacteria, specifically Ruegeria sp. KLH11, from the sponge Mycale laxissima. Two pairs of luxR and luxI homologues and one solo luxI homologue were identified and designated ssaRI, ssbRI, and sscI (sponge-associated symbiont locus A, B, and C, luxRI or luxI homologue). SsaI produced predominantly long-chain 3-oxo-AHLs and both SsbI and SscI specified 3-OH-AHLs. Addition of exogenous AHLs to KLH11 increased the expression of ssaI but not ssaR, ssbI or ssbR, and genetic analyses revealed a complex interconnected arrangement between SsaRI and SsbRI systems. Interestingly, flagellar motility was abolished in the ssaI and ssaR mutants, with the flagellar biosynthesis genes under strict SsaRI control, and active motility only at high culture density. Conversely, ssaI and ssaR mutants formed more robust biofilms than wild type KLH11. AHLs and transcript of the ssaI gene were detected in M. laxissima extracts suggesting that AHL signaling contributes to the decision between motility and sessility and that it also may facilitate acclimation to different environments including the sponge host.

Keywords: quorum sensing, acyl-homoserine lactones, LuxI-LuxR type regulation, sponge symbionts, motility, biofilm

Introduction

Over the past decade, culture-based and culture-independent techniques have frequently and consistently identified alpha-proteobacteria among the diverse bacteria from marine environments (Buchan et al., 2005; Rusch et al., 2007), including in association with marine sponges (Webster and Hill, 2001; Rusch et al., 2007; Mohamed et al., 2008a). More specifically, the Roseobacter clade, is estimated to account for 20-30% of the bacterial 16S rDNA in the ocean surface waters (Buchan et al., 2005). Although a significant number of roseobacters are apparently free-living, many have been found associated with eukaryotic hosts, such as dinoflagellates and sponges (Miller and Belas, 2006; Mohamed et al., 2008b; Slightom and Buchan, 2009), and in some cases, the symbiotic bacteria are essential for host survival. When nutrients are plentiful, roseobacters can associate with particulate organic matter or algal particles to form aggregates (Fenchel, 2001). For roseobacters the switch from a free-living state to a multicellular aggregate may involve chemical signaling (Gram et al., 2002).

Marine sponges harbor complex and diverse bacterial communities, which in some cases is estimated as 30-40% of the sponge biomass (Vacelet, 1975; Vacelet and Donadey, 1977; Hentschel et al., 2006). Although some bacteria serve as nutrients, there is evidence for stable symbionts, including several that are vertically transmitted (Enticknap et al., 2006, Sharp et al., 2007; Schmitt et al., 2008). Within the densely colonized sponge, there is also ample opportunity for both inter-species and intra-species signaling (Zan et al., 2011b).

Microbial signaling is common among dense microbial populations, such as those found within sponges. Quorum sensing (QS) allows bacteria to sense and perceive their population density through the use of diffusible signals. The acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs), that are widespread among Proteobacteria, are most often synthesized by enzymes of the LuxI family (Churchill and Chen, 2011). In the AHL-based QS model initially described for control of Vibrio fischeri bioluminescence (lux) gene expression, each cell produces a small amount of a signal that can be dissipated by passive diffusion and is therefore incapable of eliciting a response. As the population density and AHL concentration reaches a threshold concentration within the cell, AHL receptors, usually LuxR homologues, bind to the AHLs. The LuxR-AHL complexes typically activate a specific suite of target genes, although a small number of LuxR-type proteins act to repress target gene expression and are inhibited by AHLs (Fuqua and Greenberg, 2002; Minogue et al., 2002). Many LuxR type proteins recognize an 18-20 bp “lux-type” box (often an inverted repeat), which, in the case of the V. fischeri lux operon, is centered -42.5 base pairs (bp) upstream of the transcriptional start site of the lux operon, overlapping with the presumptive -35 element (Devine et al., 1989; Egland and Greenberg, 1999). Liganded LuxR-type proteins typically activate transcription, via interactions with RNA polymerase. Activated genes often include the gene encoding the cognate LuxI-type AHL synthase, thereby creating a positive feedback loop (Egland and Greenberg, 1999).

AHLs have been identified in greater than a hundred different species and are among the best-studied signaling molecules in Proteobacteria (Ahlgren et al., 2011). QS regulates a variety of cellular processes including bioluminescence, conjugal transfer, symbioses, virulence, and biofilm formation (Fuqua and Greenberg, 2002; Daniels et al., 2004). Various sponge-associated roseobacters have been shown to synthesize AHLs (Taylor et al.,2004; Mohamed et al., 2008b). Ruegeria sp. KLH11, a sponge-associated member of the Silicibacter–Ruegeria subgroup of Roseobacter clade, produces at least six different AHLs detected using AHL-responsive biosensors (Mohamed et al., 2008b). Examination of the QS circuits in KLH11 provides a window into the complex interbacterial signaling that is potentially at play within sponges. In this study, we report (i) the types and relative amounts of KLH11 AHLs (ii) isolation and genetic analyses of multiple genetically-linked luxR and luxI homologues, their cognate AHLs, and their quorum sensing networks, (iii) the detection of AHL synthase expression and AHL bioactivity from native sponge extracts, and (iv) the control of flagellar swimming motility and biofilm formation by QS. This study represents the first detailed chemical and genetic analyses of QS in the Roseobacter clade.

Results

AHL synthesis and genetic isolation of luxI and luxR homologues from KLH11

The sponge symbiont Ruegeria sp. KLH11 has a very complex profile of AHLs as evaluated by bioassays and fractionation by thin layer chromatography (Fig. 1; Mohamed et al., 2008b). This bioassay is highly sensitive, but has a bias towards short chain AHLs similar to the A. tumefaciens cognate 3-N-oxo-octanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C8-HSL) (Zhu et al., 1998). A less biased semi-quantitative chemical analysis of the KLH11 whole culture organic extracts was performed using high performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS; Gould et al., 2006). The dominant AHLs were found to be hydroxylated forms of tetradecanoyl (C14) species, saturated (3-OH-C14-HSL) and unsaturated (3-OH-C14:1-HSL), and hydroxylated dodecanoyl species (3-OH-C12-HSL) (Fig. 2A, Fig. S1A, Table 1). The shorter chain AHLs detectable in bioassays (Fig. 1), were not observed with this chemical analysis suggesting that they are in low relative abundance.

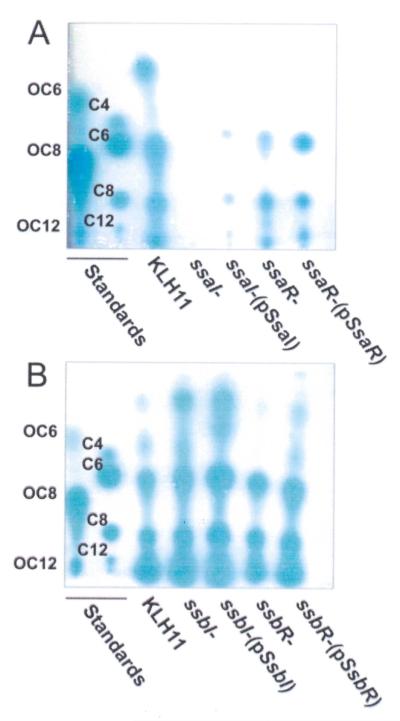

Figure 1. RP-TLC analysis of AHLs from KLH11 and quorum sensing mutants.

TLC plates were overlaid with the A. tumefaciens ultrasensitive AHL reporter strain (Zan et al. 2003). Mixtures of synthetic 3-oxo- and fully reduced AHL standards were run on each plate in lanes 1 and 2 (labeled on plate). (A) KLH11 SsaRI mutants. KLH11, ssaI- and ssaR-mutants and the plasmid-complemented mutants are labeled. (B) KLH11 SsbRI mutants. KLH11, ssbI- and ssbR-mutants and the plasmid-complemented mutants are labeled. AHL standard concentrations are: Fully reduced, C4, 1 mM; C6, 500 μM; C8, 50 nM; C10, 125 μM. 3-oxo derivatives, 3-oxo-C6, 50 nM; 3-oxo-C8, 42 nM; 3-oxo-C12, 68 μM.

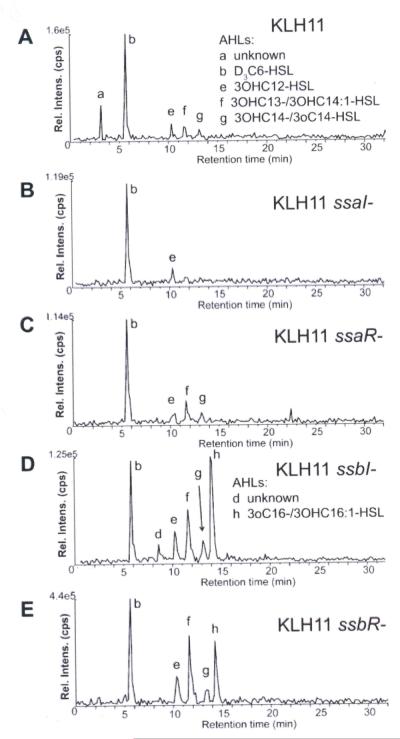

Figure 2. Mass spectrometry analysis of purified samples from KLH11 derivatives.

The products of reverse-phase chromatographic separation of AHLs extracted and purified from wild type KLH11 and mutants were examined using the precursor ion-scanning mode (transitions were monitored for precursor [M + H]+ -> m/z 102). The peaks in the chromatograms, (A) wt KLH11. (B) KLH11 ssaI–, (C) KLH11 ssaR–, (D) KLH11 ssbI–, and (E) KLH11 ssbR– are labeled with lowercase lettering and include species defined in Table 1 and the AHLs noted.

Table 1.

AHLs: Retention times, identification and relative abundances based on tandem mass spectrometry.

| Peak Label |

Retention time ± 0.6 (min) |

[M+H] +m/z |

[M+NH4] +m/z |

AHLa | Ratio to internal standard (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KLH11 |

E. coli |

KLH11ssaI-ssbI- |

||||||||||||

| WT | ssaI- | ssaR- | ssbI- | ssbR- | pSsaI | pSsbI | - | pSsaI | pSsbI | |||||

| a | 3.0 | unk | + | |||||||||||

| b | 5.6 | 203 | 220 | d3C6-HSL | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ |

| c | 7.6 | unk | + | + | ||||||||||

| d | 8.9 | unk | + | + | + | |||||||||

| e | 10.4 | 300 | 317 | OH-C12-HSL* | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.29 | 0.26 | <0.01 | 25.39 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 2.6 |

| f | 11.8 | 314 | 331 | OH-C13-HSL* | 0.20 | 0.61 | 94.0 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 1.75 | ||||

| 326 | 343 | OH-C14:1-HSL* | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.53 | 77.0 | 82.8 | |||||

| g | 13.5 | 328 | 345 | OH-C14-HSL* | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 1.94 | 147.6 | 0.07 | 1.13 | 148.0 | |

| 326 | 343 | oxo-C14-HSL§ | 11.88 | 0.33 | ||||||||||

| h | 14.5 | 354 | 371 | oxo-C16-HSL§ | 1.4 | 0.80 | 1.87 | 2.60 | ||||||

| OH-C16:1-HSL* | 28.1 | 9.07† | ||||||||||||

| i | 15.8 | unk | + | + | ||||||||||

| j | 16.4 | unk | + | + | ||||||||||

| k | 18.3 | unk | + | + | ||||||||||

Peak Label-Reversed phase LC/MS/MS separation and AHL detection based on precursors of m/z 102.1 as labeled in Figures 2,3 and supplemental Figure 3.

all confirmed AHLs modified at the 3 position, 3-oxo or 3-OH. Unk corresponds to an unknown component that generated m/z 102 upon collisional activation but could not be assigned a specific AHL structure.

detected, but could not be quantitated

confirmed by silylation for E. coli samples

confirmed by methoxymation for E. coli samples

internal standard

oxo-C16 and OH-C16 could not be distinguished from KLH11, but the value is included in this row based on the trend for E. coli MC4100 in which they can be distinguished

A genetic approach was employed to isolate KLH11 AHL synthase genes. Two plasmid-borne gene libraries, with KLH11 genomic DNA digested to completion with HindIII or SalI, both with cleavage products averaging 4 kb, were ligated into the expression (Plac) vector pBBR1-MCS5 (Kovach et al., 1995) and then transformed en masse into an A. tumefaciens strain that does not synthesize AHLs (Mohamed et al., 2008b). This AHL sensitive strain responds to introduction of plasmid-borne AHL synthase genes and expresses an AHL-dependent lacZ fusion. A pool of several thousand transformants was screened on selective medium with no exogenous AHL and X-Gal. Of the 16 blue colonies isolated, several produced a diffusible activity, which induced lacZ expression in closely adjacent colonies after extended incubation. From these presumptive AHL+ transformants, insert fragments were isolated and sequenced, identifying two separate loci with similarity to luxI from V. fischeri, each adjacent and in tandem arrangement downstream of a luxR homologue (Fig. S2A and B). We designated these genes ssaRI and ssbRI (Sponge-associated symbiont locus A and locus B, respectively). The draft genome of KLH11 was completed during the course of this study (Zan et al., 2011a) and 100% identical loci were identified; thus we refer to these Genbank Accession numbers for ssaRI, ssbRI and flanking genes (Fig. S2).

The KLH11 ssaR-ssaI and ssbR-ssbI genes are highly similar to the silR1-silI1 and silR-silI2 genes from R. pomeroyi DSS-3 (Moran et al., 2004). SsaI is 71% identical to SilI1, and each has an unusual C-terminal extension (~60 aa) relative to other LuxI-type proteins. SsaR and SilR1 share 79% identity. SsbI shares 82% identity with SilI2 and SsbR is 74% identical to SilR2. Thus, it appears that SsaRI and SilRI1, and SsbRI and SilRI2, are orthologous, whereas the SsaRI and SsbRI systems are paralogous,

After completing the KLH11 genome sequence, a third presumptive AHL synthase was identified and named sscI. Although sscI had escaped our genetic screen, it shares 81% identity to SsbI on the amino acid level (Fig S3), is of similar size and is likely to be a recent gene duplication. The sscI gene is not genetically linked to a luxR homologue, and is absent in the related R. pomeroyi DSS-3 genome.

SsaI and SsbI synthesize long chain–length AHLs when expressed in E. coli

Each presumptive AHL synthase gene was expressed from the Plac promoter carried on a low copy number plasmid in E. coli MC4100 for mass spectrometry analysis. E. coli does not produce AHLs and thus those produced will generally reflect the intrinsic specificity of the enzyme in the E. coli background (Fig. 3A, Table 1, Fig. S1B). Trimethylsilylation and methoximation of these samples (Clay and Murphy, 1979; Maclouf et al., 1987) revealed that SsaI produces 3-oxo-AHLs, the most abundant species of which is 3-oxo-C14-HSL (Table 1, Fig. S1B), but also including a C16 derivative, that was shown by methoxymation to be a 3-oxo-C16 derivative. No 3-oxo-AHLs were observed for E. coli expressing SsbI, but rather 3-hydroxy-HSLs were identified, with predominant 3-OH-C14-HSL, 3-OH-C14:1-HSL and 3-OH-C13-HSL (Fig. 3B, Fig. S1B, Table 1). For both AHL synthases, putative AHL derivatives were also detected, but their identity was not confirmed due to a lack of reference standards (Table 1). Overall, SsaI and SsbI drive the synthesis of long chain (lc) AHLs that differ in their modification at the 3-position of the acyl chain, 3-oxo and 3-OH, respectively. Expression of sscI in E. coli revealed the same pattern of AHLs as did ssbI (compare Figures 2B, S1B, S4A and S4B).

Figure 3. Mass spectrometric analysis of plasmid-expressed SsaI and SsbI-directed AHLs from E. coli and KLH11.

Cultures of E. coli MC4100 and a KLH11 derivative with in-frame deletions of ssaI and ssbI expressing plasmid-borne ssaI or ssbI were extracted and subjected to reverse-phase chromatographic separation prior to tandem MS analysis using the precursor ion-scanning mode (transitions were monitored for precursor [M + H]+ -> m/z 102) for (A) MC4100 + SsaI, (B) MC4100 + SsbI, (C). KLH11 ssaI–ssbI–, (D) KLH11 ssaI–ssbI + Plac-ssaI, (E) KLH11 ssaI–ssbI + Plac-ssbI. The peaks in the chromatograms are labeled with lowercase lettering and include species defined in Table 1 and the AHLs noted.

Mutational analysis of ssaRI and ssbRI in KLH11

Campbell-type plasmid insertions were generated in the ssaI, ssaR, ssbI and ssbR genes in KLH11 using pVIK112, which generates lacZ transcriptional fusions to the disrupted gene (Kalogeraki and Winans, 1997). Mutation of ssaI resulted in complete loss of AHLs using the biosensor assay (Fig. 1A). Consistently, mass spectrometry analyses of organic extracts from the ssaI mutant reveal a dramatic decrease in AHL abundance, although trace levels of 3-OH-C12-HSL were observed (Fig. 2B, Fig. S1A, Table 1). The loss of ssaR (Fig. 2C) did not significantly alter the pattern of AHLs observed in the wt KLH11, consistent with the bioassays (Fig. 1A). In contrast, chemical analysis of the ssbI mutant surprisingly revealed an overall increase in AHL levels (Fig. 1B, Fig. 2D), but also a shift in the spectrum of AHLs produced, including the presence of C16 derivatives (3-oxo-C16-HSL or 3-OH-C16:1, low levels precluded their distinction) as major species, but also hydroxylated derivatives, 3-OH-C14, 3-OH-C14:1, and 3-OH-C12 (Table 1, Fig. S1A). Paradoxically, this indicates that although SsbI is clearly capable of driving AHL synthesis when expressed in E. coli, its presence in Ruegeria sp. KLH11 significantly repressed overall AHL production, dictating the range of AHLs synthesized. The loss of SsbR resulted in increased abundance of the AHL signals (Table 1, Fig. 2E), similar to the ssbI mutant, although this was not clear from the bioassays (Fig. 1B).

Ectopic expression of AHL synthases in a KLH11 QS mutant

A double mutant with in-frame deletions of both ssaI and ssbI was generated in KLH11. In contrast to the ssaI mutant, this double mutant surprisingly retained low-level synthesis of several AHLs (Fig. 3C), suggesting the presence of an additional unidentified AHL synthase. Indeed, we now know that the sscI gene is still present in this strain and is likely to be responsible. The introduction of Plac-ssaI or Plac-ssbI plasmids into the ssaI ssbI double mutant (Fig. 3D and 3E) was consistent with the E. coli experiments in that both enzymes drove synthesis of several different long chain signals. SsaI directed synthesis of C16 derivatives 3-oxo-C16 (or possibly 3-OH-C16:1-HSL, again too low level to distinguish) and SsbI directed synthesis of 3-OH-C14:1 and 3-OH-C14-HSL (Table 1, Fig. S1C). The mutant expressing ssaI produced longer chain length AHLs with greater hydrophobicity than it did with ssbI, but as in E. coli the Plac-ssbI plasmid resulted in much greater overall amounts of AHLs.

Alignment of SsaI and SsbI sequences with several other LuxI homologues (Fig. S3) shows good conservation of their N-terminal halves (Watson et al., 2002; Gould et al., 2004). Previous studies have found that a threonine residue at position 143 (LuxI numbering) correlates well with the production of 3-oxo-AHLs (Watson et al. 2002). Interestingly, SsaI has a threonine at the equivalent position (SsaI 145), whereas SsbI has a glycine (SsbI 136) at this position (Fig. S3), consistent with the observed AHL profiles (Fig. 3, Table 1). The SsaI C-terminal half is significantly longer than typical for LuxI-type proteins. Additionally, SsbI and SsaI vary considerably in a conserved sequence block (126-157, LuxI numbering), as well as more C-terminal to this block. This region of the enzyme is important for acyl-chain recognition and both SsaI and SsbI clearly deviate here from other better-studied AHL synthases (Watson et al., 2002; Gould et al., 2004).

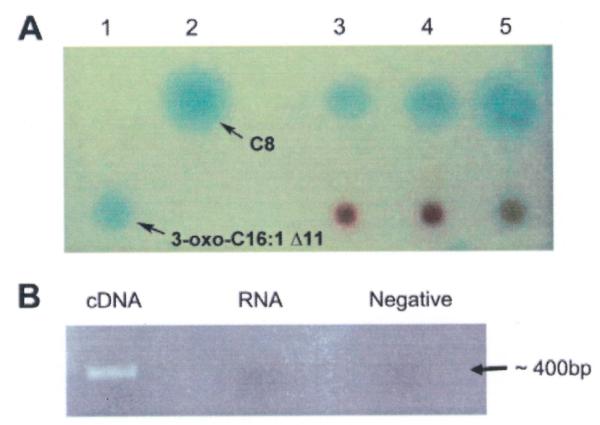

Sponge tissues contain AHLs and detectable levels of ssaI transcripts

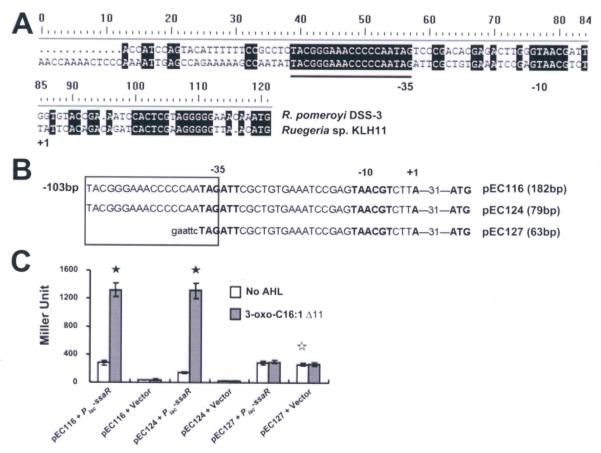

Sponge tissues were extracted with a modified Bligh-Dyer procedure (Bligh and Dyer, 1959) and these samples were fractionated by reverse phase TLC. TLC Plates were overlaid with the highly sensitive A. tumefaciens AHL biological reporter (Zhu et al., 2003) and this revealed the presence of AHL-type compounds in the extracts (Fig. 4A), one with migration similar to octanoyl-HSL (C8-HSL). In addition, two of three extracts also had an activity (somewhat obscured due to co-extracted pigments) that barely migrated from the point of application (Fig. 4A, Lanes 4 and 5), similarly to a synthetic 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11 standard.

Figure 4. Detection of ssaI gene expression and AHLs in sponge tissue.

A) Reverse phase C18 thin layer chromatography plates overlayed with A. tumefaciens AHL reporter for detecting AHLs from sponge tissues. Lane 1: 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11, lane 2: C8-HSL, lanes 3-5: M. laxissima individuals 1-3. B) RT-PCR detection of expression of ssaI gene in sponge tissue. The PCR amplicon is about 400 bp. The first lane used cDNA as template, the second lane used RNA as template to test for DNA contamination (RNA control) and the last lane was a no template negative control.

M. laxissima tissues were used to extract RNA from which cDNA was synthesized, and RT-PCR revealed that ssaI was actively expressed in these tissues (Fig. 4B). No amplification was detected in the control RNA sample of M. laxissima without the RT reaction step. The PCR amplicons were sequenced and of 13 clones sequenced all were greater than 98.5% identical to the KLH11 ssaI gene on the nucleotide level. The same approach failed to detect ssbI gene expression in sponge tissue.

Expression of ssaI is stimulated in response to KLH11 AHLs

LuxI-type genes often are regulated in response to their own cognate AHL(s) (Fuqua and Greenberg, 2002). Cultures of each of the KLH11 Campbell insertion mutations for ssaI and ssbI which created lacZ fusions to the disrupted genes were assayed for β-galactosidase activity grown in the presence and in the absence of exogenous KLH11 culture extracts. KLH11 has no significant endogenous β-galactosidase activity (Miller Units <1). The ssaI-lacZ fusion exhibited close to 16-fold induction (Table 2) when cultures were incubated in the presence of KLH11 extracts (2.5% v/v). Given that the dominant SsaI-directed are C16-AHLs, we also tested ssaI expression of the mutant with synthetic 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11. In the presence of the synthetic AHL at 2 μM, the ssaI-lacZ fusion was induced 40 fold (P <0.001, Table 2). In contrast, the expression of the ssbI-lacZ fusion in the ssbI null mutant was low and was not increased by addition of culture extracts or by 20 μM 3-OH-C14-HSL (P>0.05), the dominant long chain hydroxylated AHL produced via SsbI. However, the ssaI-lacZ fusion was induced roughly 30% (P<0.01) by addition of 20 μM 3-OH-C14-HSL, suggesting limited cross-recognition of this AHL. The ssbI-lacZ fusion was not activated by addition of 2 μM 3-oxo-c16:1 Δ11.

Table 2.

QS regulator expression in KLH11 null mutants

| β-Galactosidase Sp. Act.1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KLH11 Extracts |

Synthetic AHLs |

||||

| Mutants2 | Relevant Genotype |

No Extract | 2.5% | No AHL | + AHL3 |

| EC2 | ssaI-lacZ, null | 6 (1.7) | 95 (10.6) | 6.3 (0.7) | 213.3 (9.2) |

| EC3 | ssbI-lacZ, null | 1 (<1) | <1 (<0.1) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.1(<0.1) |

| JZ1 | ssaR-lacZ, WT | 107.1(0.8) | 105.0 (4.4) | 93.7 (8.3) | 99.3 (2.8) |

| EC4 | ssaR-lacZ, null | 23 (3) | 19 (1.4) | 26.7 (1.3) | 28.6 (2.4) |

| JZ2 | ssbR-lacZ, WT | 11.6 (2.8) | 10.8 (3.1) | 12.0 (0.5) | 12.6 (0.5) |

| EC5 | ssbR-lacZ, null | 15 (<) | 10 (4.6) | 27.6 (4.5) | 26.0 (4.2) |

Specific activity in Miller Units, averages of assays in triplicate (standard deviation)

All strains are derived from EC1, spontaneous RifR mutant. Strains EC2, EC3. JZ1 and JZ2 carry Campbell insertions and lacZ transcriptional fusions;

2 μM 3-oxo-c16:1 Δ11 was added for ssaIR and 20 μM 3-OH-C14 was added for ssbIR.

We also created similar Campbell insertion mutants of the ssaR and ssbR genes. For each gene one derivative was created in which the plasmid was integrated to generate the lacZ fusion with the wild type coding sequence intact (JZ1 and JZ2), and a second derivative in which the gene was disrupted by integration of the plasmid (EC4 and EC5). Although ssaR was expressed more strongly than ssbR (based on β-galactosidase activity), there was no effect of crude culture extracts or synthetic AHLs on the expression of these genes in the wild type or the null mutant background (Table 2). Disruption of the ssaR gene expression resulted in an approximately 4-fold decrease of ssaR expression, but this was independent of AHL.

SsaR activates expression of its cognate AHL synthase gene ssaI

It was unclear whether AHL-activated ssaI expression also required the SsaR protein and whether the Ssa system might directly influence ssbI expression. Plasmid-borne copies of each luxR-type protein paired with compatible plasmids carrying either a PssaI-lacZ fusion or a P -lacZ fusion, were introduced into the AHL− ssbI, plasmidless derivative A. tumefaciens NTL4. Cultures of these A. tumefaciens derivatives were grown in the presence or absence of 2 μM 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11 HSL. The presence of ssaR activates ssaI in the absence of exogenous AHLs (~7-fold induction; P<0.001) (Table 3). This SsaR-dependent activation was stimulated a total of 30-fold (P<0.001) by the addition of 2 μM 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11 HSL (Table 3). Several C14-HSLs were also tested, but only weakly influenced ssaI expression (Fig. S5A). Activation of the ssaI-lacZ fusion by SsaR exhibited a dose-dependent response to 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11 HSL that paralleled the response to crude culture extracts (Fig. S5B). In contrast, the PssbI-lacZ (pEC121) was not activated by Plac-ssbR (pEC123) irrespective of the presence of synthetic AHLs (<1 Miller Unit, P>0.05) or crude KLH11 extracts (Table 2, Table S1). Likewise, SsaR failed to activate ssbI and SsbR failed to activate ssaI in the presence of culture extracts and synthetic AHLs (Table S1).

Table 3.

Expression of KLH11 PssaI and PssbI promoters in an AHL- host1

| β-Galactosidase Sp. Act.2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression plasmid | Fusion plasmid | No AHL | + AHL3 |

| Vector (pBBR1-MCS5) | ssaI-lacZ (pEC116) | 51 (5) | 52 (5) |

| Plac-ssaR (pEC112) | ssaI-lacZ (pEC116) | 341 (15) | 1435 (67) |

| Vector (pBBR1-MCS5) | ssbI-lacZ (pEC121) | <1 (<0.1) | <1 (<0.1) |

| Plac-ssbR (pEC123) | ssbI-lacZ (pEC121) | <1 (<0.1) | <1 (<0.1) |

All strains derived from Ti-plasmidless A. tumefaciens NTL4

Specific activity in Miller Units, averages of assays in triplicate (standard deviation)

2 μM 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11 was added for ssaI and 20 μM 3-OH-C14 was added for ssbI

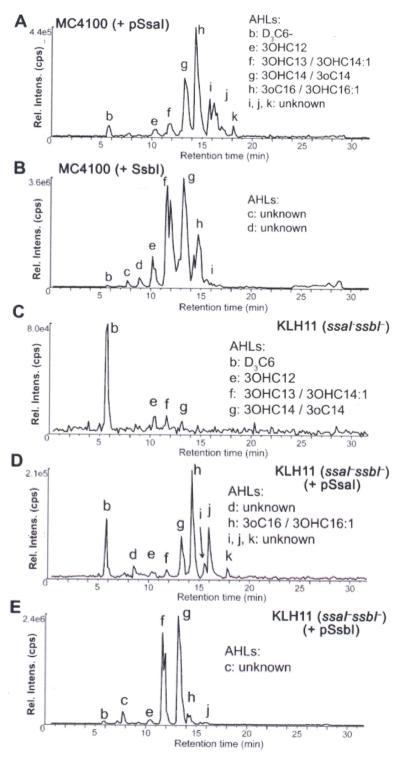

Conserved sequences upstream of ssaI are required for activation by SsaR

LuxR homologs often recognize conserved sequence elements, called lux-type boxes located upstream of target promoters, including those of luxI homologues (Devine et al., 1989; Egland and Greenberg, 1999). The ssaI gene is downstream of the ssaR gene in a tandem arrangement, with an intergenic region of 118 bp but reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR assays demonstrated that ssaI and ssaR are not in the same operon (Fig. S2A; similarly, ssbI and ssbR are also in separate operons, Fig. S2B). Inspection of the sequence upstream of ssaI revealed no inverted repeats and no motifs with primary sequence similarity to bona fide lux-type boxes. Comparison of this region between ssaR and ssaI and the homologous region between silR1 and silI1 from R. pomeroyi DSS-3 (Moran et al., 2004) revealed only 60% identity, except for a 19 bp fully conserved segment (TACGGGAAACCCCCAATAG), located 60 bp upstream of the ssaI start codon (Fig. 5A). Although it is not an inverted repeat and shares limited primary sequence similarity with known lux-type boxes, we reasoned the sequence might be a regulatory element given its appropriate size and location, and tentatively designated this a ssa box. Deletions were generated in the AHL and SsaR-responsive PssaI-lacZ plasmid (pEC116), one to just upstream of the ssa box (pEC124) and a larger deletion (pEC127) that almost completely removes the element (Fig. 5B). In A. tumefaciens NTL4 the deletion construct retaining the ssa box (pEC124) was inducible by ssaR and 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11-HSL to the same extent as the plasmid with the complete intergenic region. Deletion of the ssa box abolished this induction, although it increased basal expression levels. These results reveal a role for the presumptive ssa box in AHL-dependent activation of ssaI.

Figure 5. Deletion analysis of the ssaI promoter.

(A) Putative promoter elements are indicated in boldface and putative -35 and -10 regions are indicated below the sequences; +1 indicates the predicted transcription start site. Presumptive Ssa box is underlined. (B) The presumptive ssa box is indicated within the rectangle. Plasmid name and size of insert are indicated adjacent to the translational start site. For the plasmid pEC116, it also included 103 bp upstream of the Ssa box. Lower case sequence indicates an EcoRI restriction site. (C) β-Galactosidase activity of the three deletion constructs fused with the lacZ reporter. All strains derived from Ti-plasmidless A. tumefaciens NTL4. Bars represent the average of three biological replicates and the error bars are standard deviation. The filled asterisks show the statistical significance between samples, with and without 3-oxo-C16:1 (Δ11), in the strains that have SsaR (P<0.001). The unfilled asterisk shows the statistical significance of the basal expression levels between pEC127 and each of pEC116 and pEC127 (P<0.001). The result presented is a representative of several independent experiments each with three biological replicates.

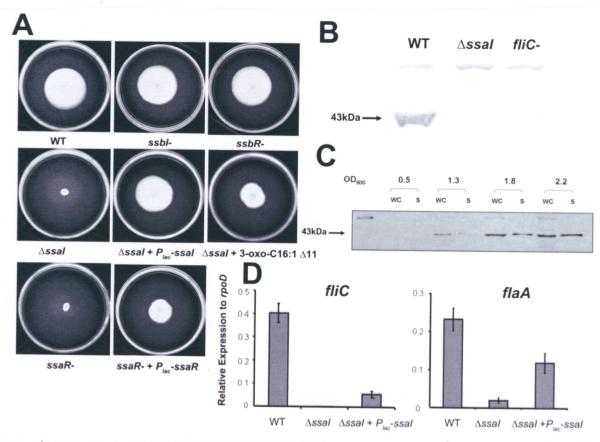

SsaRI controls swimming motility and flagellar biosynthesis

For several different bacteria, QS regulates bacterial motility and flagellar synthesis (Kim et al., 2007; Ng and Bassler, 2009). KLH11 swims under laboratory conditions but does not exhibit swarming (data not shown). All four KLH11 mutants (ΔssaI, ssbI-, ssaR-, and ssbR-) were tested for their motility on MB 2216 swim agar plates (Fig. 6A). The ΔssaI and ssaR-mutants did not migrate from the site of inoculation, whereas the ssbI- and ssbR-mutants migrated through the motility agar similar to wild type. The swimming deficiency of the ΔssaI mutant was fully complemented with a plasmid-borne copy of the gene, and the ssaR-mutant was partially complemented by similar provision of ssaR. Addition of 2 μM 3-oxo-c16:1 Δ11-HSL into swim agar can partially restore motility in the ΔssaI strain, albeit less efficiently than through complementation (Fig. 6A). As expected, motility was not restored in the ssaR-mutant in the media with 2 μM 3-oxo-c16:1 Δ11-HSL (unpublished results). The observed differences in migration through swim agar were not likely due to growth effects as the ssaI and ssaR mutants grow at the same rate as wild type (Fig. S6).

Figure 6. Regulation of swimming motility and flagellar biosynthesis by the SsaRI QS system.

(A) Swimming motility assays for QS mutants on 0.25% Marine Agar 2216 after 8 days at 28°C. 2 μM 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11 was added for the ΔssaI mutant and pEC108 (Plac-ssaI) and pEC112 (Plac-ssaR) were used to complement ΔssaI and ssaR-mutants, respectively. (B) Antiserum raised against whole flagella from C. crescentus also recognizes KLH11 flagella. Estimated size of KLH11 flagellin is 43 kDa. (C) Flagellin synthesis during late culture stages requires ssaI. Wild type cultures were harvested at various time points along the growth curve. WC, whole culture; S, supernatant. (D) qRT-PCR results of genes fliC and flaA in wt, the ssaI deletion strain and complementation strains. Error bars are the standard deviations and results are representative of two independent experiments with triplicates.

In order to visualize the presence of flagella, the wild type and mutant strains were observed by phase contrast microscopy using both wet mounts and flagellar stains. Interestingly, early stage wild type cultures did not have flagella, and no swimming cells were observed, whereas in late stage cultures flagella were clearly assembled (Fig. S7) and cells were visibly motile. Both the ssaI- and the ssaR-mutants lacked flagella and were never observed to swim, irrespective of culture stage. The cells also appeared to clump more readily. The ssbI- and ssbR-mutants were as motile as wild type and had abundant flagella in late stage cultures (Fig. S7). The presence of flagellar proteins in KLH11 cultures was examined using immunoblotting with antisera raised against whole flagella from Caulobacter crescentus, a related alpha-proteobacterium. In western blots from KLH11 late stage cultures, supernatants contained a protein of approximately 43 kDa (Fig. 6B) that was also present from pelleted cells. This protein matches the predicted 41.5 kDa size of the only flagellin homologue in KLH11, fliC gene product (Zan et al., 2011a). A site-specific disruption of the KLH11 fliC homologue abolished swimming motility (unpublished results) and caused loss of the 43 kDa protein, the same presumptive flagellin protein was also absent from the ΔssaI mutant (Fig. 6B).

To determine when flagellar biosynthesis occurs during culture growth, samples were harvested along the growth curve at four different time points; mid-exponential, early stationary, mid-stationary, and late stationary phase from the parent strain and the ssaI-mutant. At an OD600 of 0.5, the parent strain had no detectable flagellin in either the whole cell or supernatant fraction, but as the culture density increased (OD600 >1.3), flagellin was detected in the whole culture fractions and weakly in the culture supernatant and continued to increase as the culture grew (Fig. 6C). Flagellin was never detected in samples of the ssaI-mutant, irrespective of culture density.

To determine if the SsaRI system regulates the transcription of the flagellin gene (fliC), quantitative Real–Time PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to measure fliC expression. Late stage cultures grown to an OD600 at which KLH11 produces visible flagella have approximately 2 orders of magnitude higher fliC expression in wt KLH11 compared to the ΔssaI mutant (Fig. 6D, P<0.001). The Plac-ssaI plasmid (pEC108) complemented fliC expression compared to the ΔssaI mutant (P<0.05), although not to full wild type levels (Fig. 6D). Silicibacter sp. TM1040 is well studied for motility (Belas et al., 2009), and flaA is a required motor-associated protein in a putative Class II flagellar operon. Examination of the KLH11 flaA homologue by qRT-PCR revealed a 10-fold decrease of flaA expression in the ssaI deletion mutant (P<0.001). A plasmid-borne ssaI copy was able to partially restore flaA expression (Fig. 6D, P<0.05). These results suggest that an intact SsaRI system is required for swimming through regulation expression of flagellar genes.

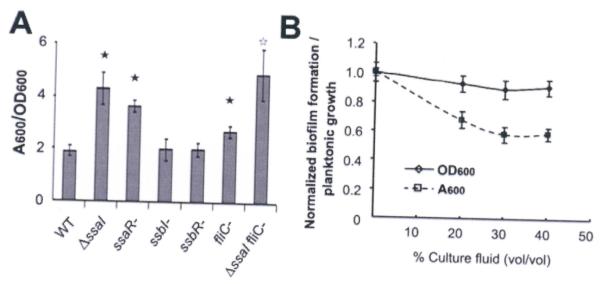

SsaRI mutants exhibit increased biofilm formation

QS can also regulate bacterial biofilm formation (Hammer and Bassler, 2003; Shrout et al., 2006). Given the importance of the SsaRI system to swimming motility, we questioned if QS might influence KLH11 biofilm formation. A static coverslip biofilm assay was performed for the ssa and ssb mutants compared to the wild type. Crystal violet stained biofilms on PVC coverslips were solubilized in 33% acetic acid, and the absorbance at 600 nm (A600) was measured. Relative to wild type, the ΔssaI and ssaR-mutants clearly have increased biofilm formation, most pronounced by 48 h post-inoculation (Fig. 7A, P<0.01). It was plausible that increased biofilm formation was due to the loss of motility in these mutants, limiting emigration of bacteria from biofilms. Indeed, biofilm formation in the non-motile fliC mutant was also modestly increased compared to wild type (Fig. 7A, P<0.01). However, biofilm formation in the ΔssaI fliC-mutant was even stronger than the non-motile fliC mutant (P<0.05). This suggests that the increased biofilm formation in the ΔssaI mutant is not entirely due to the lack of motility. The ssbI and ssbR mutants formed biofilms that were indistinguishable from wild type KLH11 (Fig. 7A, P>0.05).

Figure 7. Increased biofilm formation by KLH11 in ssaI and ssaR mutants.

(A) Standard 48 hr coverslip biofilm assays measuring A600 of solubilized crystal violet normalized to the culture density (OD600) for the different KLH11 strains were performed. Filled asterisks indicate statistical significance between wt KLH11 and indicated strains (P<0.01). Open asterisk indicates statistical significance between fliC- and ΔssaI fliC-mutants (P<0.05). Error bars are standard deviation of three biological replicates. (B) Inhibition of biofilm formation for ΔssaI mutant by wt KLH11 culture fluids. Different % (v/v) wt KLH11 culture fluids were added into ΔssaI culture at the time of inoculation. Solubilized crystal violet stain of adherent biomass (A600) and the optical density of the cultures (OD600) were measured as a function of percent culture fluid addition. Data were normalized to the cultures with no added wt KLH11 culture fluids. Values are averages of assays performed in triplicate and error bars are standard deviations.

Addition of KLH11 late stage culture fluids (40% v/v) into biofilm assays with the ΔssaI mutant reduced biofilm formation to 60% the level of untreated cultures (P<0.05) whereas planktonic growth is unaffected (Fig. 7B, P>0.05). This inhibition effect is not due to nutrient depletion because 1X MB2216 was provided in addition to the nutrients remaining in the supernatant. The inhibition is also not due to pH changes as there was <0.1 pH unit difference between normal MB2216 and MB2216 conditioned with wt KLH11 culture fluids.

Discussion

There is limited understanding of QS mechanisms in the diverse and abundant bacteria living in the marine environment (Cicirelli et al., 2008). In this study we have demonstrated the production of AHLs from tissues of the soft-bodied, shallow water sponge M. laxissima, similar to those produced by abundant cultivatable, AHL+ sponge-associated bacteria. Likewise we also detect expression of the ssaI AHL synthase gene directly in total RNA from the sponge, effectively connecting our laboratory findings on QS in these symbiotic bacteria, with their native host environment.

Our studies on sponge symbionts initiated with the use of AHL responsive bioassays (Mohamed et al., 2008b). We have developed Ruegeria sp. KLH11, a member of the Silicibacter–Ruegeria group of the Roseobacter clade, as a quorum sensing model. KLH11 AHLs are readily detectable using the A. tumefaciens bioreporter, ranging from non-polar, long chain AHLs to more polar, short chain AHLs (Fig. 1; Mohamed et al., 2008b). However, even the broadly responsive A. tumefaciens system is biased towards AHLs structurally similar to its cognate 3-oxo-C8-HSL, and often cannot distinguish between related AHLs. We therefore employed mass spectrometric analysis to provide unbiased AHL identification that also provides information on relative abundance for at least a subset of AHLs. This approach detected AHLs with acyl chains greater than C12 from KLH11, but AHLs with shorter acyl chains revealed in bioassays were below the effective detection threshold for our technique. This finding highlights the strengths and weakness of each detection system; the AHL-responsive bioassays are extremely sensitive, but difficult to quantitate, whereas direct chemical detection can identify and quantitate AHLs, but at lower sensitivity. In the end, the combined approach provided the best insights into this complex system.

KLH11 AHLs were predominantly 12-16 carbons, some with unsaturated bonds, with either 3-OH or 3-oxo substituents. Although SsaI-directed oxo-AHLs were not detectable in wild type KLH11 extracts by the mass spectrometric approach (Fig. 2; Table 1), they are clearly present in the TLC assays (Fig. 1). The relatively abundant 3-OH-C14-HSL and 3-OH-C14:1-HSLs likely originate from SsbI or the closely related SscI. The hydroxy-, oxo- and double bonded character of the long chain AHLs would be beneficial for maintaining their solubility, and longer acyl chains are more stable in moderately alkaline marine environments (Riebesell et al., 2000; Yates et al., 2002), consistent with other studies from marine systems (Wagner-Dobler et al., 2005).

The pattern of AHLs specified by SsaI and SsbI, 3-oxo-AHLs and 3-OH-AHLs, respectively, vary in their chain length depending on the bacterial species in which they are expressed. For example, in E. coli harboring the Plac-ssaI plasmid, 3-oxo-C14 was the most abundant AHL, and 3-oxo-C16 was present at 15% (Table 1). This relationship reversed when the same plasmid was expressed in the KLH11ΔssaIΔssbI mutant, resulting in high relative levels of 3-oxo-C16:1, with 3-oxo-C14 at roughly 4% those levels. Likewise, E. coli harboring the Plac-ssbI plasmid resulted in high levels of 3-OH-C12-HSL and detectable 3-OH-C13-HSL among the other OH-AHLs, whereas these AHLs were much less abundant when the same plasmid was expressed in the KLH11ΔssaIΔssbI mutant (Table 1). This shift toward increased acyl-chain lengths in KLH11 relative to those in E. coli may be explained by the differences in acyl-ACP substrate pools available in the different strains. Indeed, this has been observed in cases of AHL synthase over-expression in E. coli, where unusual AHLs including those with odd-chain lengths have been observed (Gould et al., 2006). Differences in growth temperature may also influence the levels and distribution of AHLs (Yates et al., 2002) However, expression in E. coli enables analysis of the intrinsic specificity of each AHL synthase and was important in some cases for AHL identification.

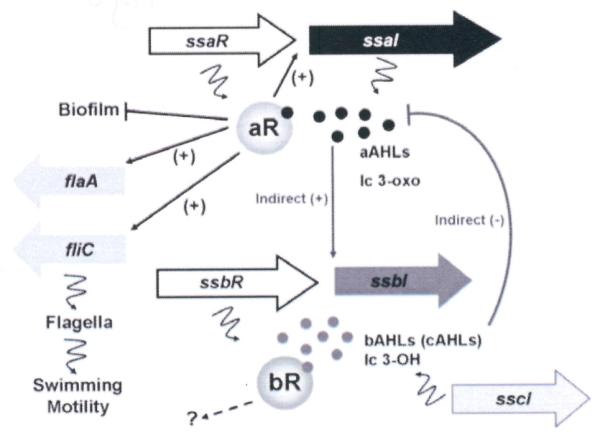

Bacteria that have multiple AHL-based QS systems can organize these systems in interconnected regulatory networks (Atkinson et al., 2008). The results of our AHL chemistry, genetic analysis, and gene expression experiments reveal a complex network of signal production and regulation in KLH11 (Fig. 8). The ssaI null mutant loses the majority of detectable AHLs, as evaluated by bioassays and mass spectrometry (Figs. 1 and 2, Table 1). The AHLs produced by wild type KLH11 are dominated by OH-AHLs, those synthesized by SsbI (and perhaps SscI), but the ssaI mutant phenotype suggests that it influences production of these AHLs. Surprisingly, and in contrast to the ssaI null phenotype, mutation of ssbI increases the overall AHL activity. Mass spectrometry reveals a large increase in an oxo-C16 AHL, correlated with SsaI activity, which is lost in the ssbIssaI double mutant (Table 1). These findings suggest that SsbI exerts a suppressive effect on the Ssa system, and this is relieved by mutation of ssbI (and perhaps also ssbR).

Figure 8. A simplified model for the complex regulatory control of QS circuits in KLH11.

Model depicts a presumptive role of QS in KLH11 dispersal during the interaction between sponge host and symbiont. The ssaRI, ssbR, and sscI genes are drawn according to scale while fliC and flaA are not. The black dots represent the AHLs synthesized by SsaI, mainly long chain (lc) 3-oxo-HSL. The grey dots represent the AHLs synthesized by SsbI, mainly long chain (lc) 3-OH-HSL. The lines with bars indicate inhibition while the arrows indicate activation. Squiggly lines indicate translation of genes or products of enzyme action.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the connections between the Ssa and Ssb pathways are not directly through transcriptional control. Neither system appears to directly influence expression of the other AHL synthase genes. In fact, although SsbI-directed AHLs are lost in the ssaI-mutant, the ssaR-mutation does not affect their level, indicating that Ssb control is independent of SsaR. In contrast, both SsaR and the SsaI-specified AHLs are required to autoregulate ssaI expression, activate motility and inhibit biofilm formation. It is plausible that an unidentified LuxR-type protein regulates the Ssb system in response to SsaI-produced AHLs, similar to the P. aeruginosa QscR protein, a LuxR-type transcription factor that responds to AHLs produced via the LasI-LasR system to control its target genes (Fuqua, 2006; Lequette et al., 2006). The genome sequences of KLH11 and R. pomeroyi DSS-3 reveal several additional solo-type LuxR-type proteins that might be functioning in response to SsaI-directed AHLs to influence the Ssb pathway.

Inhibition of Ssa activity by the Ssb system is potentially due to competition for common substrates. Our findings demonstrate that both AHL synthases catalyze production of long chain AHLs and may be in competition for long chain acyl-acyl carrier protein conjugates (Churchill and Chen, 2011), In P. aeruginosa, AHLs derived from LasI can directly block the activation of another LuxR homologue RhlR by its own cognate AHL (Pesci et al., 1997). It was plausible that Ssb-derived AHLs may have had an inhibitory effect on SsaI activity, however addition of 3-OH-C14-HSL to KLH11 resulted in a modest activation of ssaI expression, and thus this is not likely.

Our experiments implicate a non-symmetrical sequence element immediately upstream of ssaI that is required for SsaR activation (Fig. 5C). LuxR homologs have been shown to bind to symmetric (Zhang et al., 2002) as well as asymmetric R-boxes (Schuster et al., 2004). In contrast, there is no indication of AHL-responsive autoregulation for ssbI (Table 2) nor when SsbR and an ssbI-lacZ fusion are tested in A. tumefaciens (Table 3). The ssbI gene joins a small list of LuxI homologues that are not positively autoregulated (Beck von Bodman and Farrand, 1995).

A growing number of bacteria including Rhizobium etli, Serratia liquefaciens and P. aeruginosa are recognized to control motility via quorum sensing, including swarming, twitching and swimming (Eberl et al., 1996; Daniels et al., 2004; Shrout et al., 2006). Many of these systems are inhibited by AHLs, whereas a smaller number are activated. In S. meliloti QS inhibits swimming motility, whereas for the β-proteobacteria Burkholderia glumae QS activates flagellar biosynthesis and thereby swimming and swarming motility (Kim et al., 2007; Honag et al., 2008). In KLH11 flagellar biosynthesis is under tight, positive SsaRI control (Fig. 6). Despite their low abundance, the SsaI-derived oxo-AHLs are clearly important to activate swimming in late stage cultures, mutation of ssaI leads to loss of swimming motility, and provision of AHLs alone can rescue the mutant’s swimming deficiency. Clearly, the SsaI-directed AHLs function below our mass spectrometry detection threshold. Some AHL QS systems are tuned to exceptionally low AHL levels, such as the ExpR system from Sinorhizobium meliloti (Pellock et al., 2002). Reconstructing SsaR-dependent gene regulation in A. tumefaciens suggests that as little as 10 nM 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11 is saturating (Fig S5B), and this may be even lower at native ssaR expression levels.

Our observations suggest that the influence of the SsaRI system on motility may be needed to limit aggregation. Interestingly, although the KLH11 and R. pomeroyi DSS-3 genomes encode flagellar motility functions, neither have genes for chemotaxis, including Che regulatory proteins and methyl-dependent chemotaxis proteins (Moran et al., 2004; Zan et al., 2011a). For KLH11, and perhaps R. pomeroyi DSS-3, motility may function to promote dispersal from aggregates instead of chemotaxis, employing QS control to provide a population density response. A similar function was proposed for QS in the photosynthetic microbe Rhodobacter sphaeroides (Puskas et al., 1997).

How does SsaR control flagellar assembly and function in KLH11? Both flaA, and fliC, class II and class III flagellar genes, respectively, require SsaI for significant expression (Fig. 6D), which suggests that in KLH11 QS controls motility at an early step in flagellar gene expression. In most flagellated bacteria there is a primary regulator that initiates expression of the flagellar gene cascade (Macnab, 1996). Although it is conceivable that SsaR could be this master regulator in KLH11, it is more likely that it controls expression of another regulator. In E. coli and several other bacteria FlhDC proteins serve as the primary regulators of flagellar assembly (Soutourina and Bertin, 2003), but there are no FlhDC homologues in the KLH11 or R. pomeroyi DSS-3 genomes (Moran et al., 2004; Zan et al., 2011a). For C. crescentus, the essential cell cycle master regulator CtrA initiates flagellar assembly (Muir and Gober, 2004). KLH11 encodes a ctrA homologue, and in its relative Silicibacter sp. TM1040, this gene is also required for flagellar activity (Belas et al., 2009).

It is well established that bacterial motility can have a profound impact on surface adherent biofilm formation (O’Toole et al., 1998; Merritt et al., 2007). In P. aeruginosa, QS promotes biofilm maturation and QS mutants can attach but do not differentiate into mature biofilm structures (Davies et al., 1998). In contrast, in V. cholerae QS inhibits biofilm formation by decreasing the expression of exopolysaccharide (EPS) genes, and may also promote dispersal from biofilms and in late infection stages (Hammer and Bassler, 2003; Waters et al., 2008; Krasteva et al., 2010).

Accumulation of bacteria on a surface is the net sum of attachment, growth, and emigration. Decreased motility may reduce biofilm formation by limiting initial surface contact, but it also reduces migration from biofilms, thereby increasing biofilm formation. For KLH11, the ssaI and ssaR mutants are non-motile, and have increased biofilm formation (Fig. 7A), which is clearly due to QS as KLH11 supernatants antagonize biofilm formation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig.7B). The ΔssaI mutant has a much more pronounced deficiency than the equally non-motile fliC (flagellin) mutant and the ΔssaI fliC-double mutant has a biofilm phenotype indistinguishable from ΔssaI itself. These findings suggest that the increased biofilm formation in ssaI and ssaR mutants is not only due to a loss of motility. Any additional relevant SsaRI target(s) remains to be determined but might include genes involved in surfactant synthesis or modulation of internal signaling molecules such as cyclic di-guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) (Davey et al., 2003; Hengge, 2009). Searches of the KLH11 genome for matches to the ssa box identified here have failed to yield potential targets. Overall, the QS activation of motility and inhibition of adherence in KLH11 dictates the transition between free-living and sessile modes of growth and may limit aggregation within the sponge.

Experimental procedures

Reagents, strains, plasmids, growth conditions and DNA introduction

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2 and all the primers used are listed in Table S3. Antibiotics were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Standards used for AHL analysis; D3C6-HSL (N-[(3S)-tetrahydro-2-oxo-3-furanyl]-hexanamide-6,6,6-d3 ≥99% deuterated product), 3-oxo-C14-HSL and 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11cis-(L)-HSL were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, Michigan). 3-OH-C12-HSL, 3-OH-C13-HSL and 3-OH-C14-HSL were synthesized as described previously (Gould et al., 2006). Reagents used for sample derivatization and mass spectrometry analysis were: methoxyamine hydrochloride (MP Biomedicals, Solon, Ohio), bis (trimethylsily) tri-fluroacetamide (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA). HPLC grade acetonitrile, HPLC grade methanol, and sodium acetate trihydrate were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, New Jersey). The solid phase extraction cartridges were Strata-x 33u polymeric reversed phase 60 mg ml−1 from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA) or Sep-Pak plus, silica cartridges (Waters WAT020520).

DNA manipulations were performed by standard techniques (Sambrook et al., 1989) and restriction enzymes and PhusionTM High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase were obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Oligonucleotides were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and DNA sequencing was performed on an ABI3700 automated sequencer at the Indiana Molecular Biology Institute (Bloomington, IN). Sequence analysis was performed with Vector NTI Advance 10 (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). KLH11 and KLH11-EC1 derivatives were grown in Marine Broth 2216 (MB2216) (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at 28°C. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. A. tumefaciens strains were grown in AT minimal medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose and 15 mM (NH4)2SO4 (ATGN) (Tempé et al., 1977). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (μg ml−1): (i) E. coli (ampicillin, Ap, 100; gentamycin, Gm, 25; kanamycin, Km 25; spectinomycin, Sp, 100), (ii) KLH11 (Km, 100; Rifampicin, Rif, 200; Gm 25, Sp, 100) (iii), A. tumefaciens (Gm, 3000; Sp 200).

Plasmids were introduced into KLH11 using either electroporation or conjugation, into E. coli using standard methods of transformation or electroporation (Sambrook et al., 1989) and into A. tumefaciens using a standard electroporation method (Mersereau et al., 1990).

Preparation of AHL samples and analysis by RP-HPLC and ESI mass spectrometry

KLH11 derivatives were grown in MB 2216 with appropriate antibiotics at 28° C to stationary phase (OD600 ~2.0) in the presence of 5 g l−1 of Amberlite XAD 16 resin for 36 h. E. coli MC4100 expressing ssaI or ssbI was grown in LB at 37° C with 5 g l−1 of Amberlite XAD 16 resin to an OD600 of 0.6-0.8 and expression was induced 24 h by addition of 1 mM IPTG. Cells and resin were separated by centrifugation and extracted with 50 ml methanol and dried to 2 ml. 3 nanomoles of D3-C6-HSL was added to each sample as an internal standard and a volume of 0.2 ml was purified using solid phase extraction methods as described previously (Gould et al., 2006).

The purified sample was dried down and resuspended in 38 μl solvent A (8.3 mM acetic acid-NH4 pH 5.7) and 2 μl solvent B (methanol). This solution was injected on to a 50 × 3.00 mm 2.6μ C18 Kinetex Phenomenex column. A mobile phase gradient was generated from 5% B to 65% B in 5 min, then B was increased to 95% in 15 min and held for 8 min at a flow rate of 250 μl min−1. The HPLC system was interfaced to the electrospray source of a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Sciex API2000, PE Sciex, Thornhill, Ontario, CA). Precursor ion-scanning experiments were performed in positive-ion mode with the third quadrupole set to monitor m/z 102.3 and the first quadrupole set to scan a mass range of 170 to 700 over 9 s. The collision cell and instrument parameters were as follows: ion spray voltage of 4200 V, declustering potential of 50 V and collision energy of 25 V with nitrogen as the collision gas.

Qualitative analysis and estimation of AHL quantities

The identification of AHL molecular species was carried out at the first level using the HPLC retention times for the specific [M+NH4]+ ions that gave rise to m/z 102.1 (precursor ion scanning) corresponding to the available AHL reference standards. In all cases, co-injection of the authentic reference standard gave rise to an increase in the single HPLC peak corresponding to the correct AHL. For those AHLs for which reference material was not available, the observed precursor ion of m/z 102.1 was used to determine the [M+NH ]+ 4 and therefore the molecular weight of a putative AHL. If this molecular weight corresponded to a saturated or monounsaturated AHL, then the retention time was compared to predicted retention time for this molecular species based on retention times of the reference AHLs. If the molecular weight corresponded to addition of an oxygen atom (keto or hydroxyl substituent, 14 and 16 u higher) to the saturated HSL series, then derivatization by trimethylsilylation (Clay and Murphy, 1979) and methoximation (Maclouf et al., 1987) and reanalysis was performed to confirm the presence of an oxidized AHL molecular species (See Supplementary Methods). An increase in 72 u or 29 u in the observed [M+NH ]+ 4 would correspond to the formation of a trimethylsilyl ether or methoxylamine derivative of a hydroxylated-AHL or keto-AHL, respectively.

The relative amount of each AHL species was estimated based on the ratio of the abundance of the transition [M+NH ]+ 4 to m/z 102.1 divided by the abundance of the ion transition derived from the added internal standard (m/z 220.3 –>102.1), as previously described (Gould et al., 2006). In separate experiments this resulted in a linear relationship between the abundance ion ratios for the precursor ions of m/z 102.1 and quantity of AHL reference standards.

Genomic library screen of KLH11 QS genes

KLH11 genomic DNA was obtained using the BactozolTM DNA Isolation Kit from Molecular Research Center Inc. (Cincinnati, OH). The DNA was independently digested to completion by restriction enzymes HindIII and SalI and the fragments were ligated into expression vector pBBR1-MCS5 (Kovach et al., 1995) followed by electroporation into E. coli Electro-Ten Blue competent cells. Cells were plated onto LB plates with gentamycin selection and incubated at 37°C overnight. Plasmids were extracted from colonies pooled from a large number of plates. The mixed plasmids preparations from the HindIII and SalI libraries, were independently electroporated en masse into A. tumefaciens NTL4 (Zhu et al., 1998). Transformants were plated on ATGN media plus appropriate antibiotics and X-gal (40 μg ml−1). Blue colonies (harboring putative AHL synthases) were chosen for further analysis after growth at 28°C for 2-3 days.

The plasmids pECH100, pECH101, and pECS102 were identified as AHL+ transformants in the KLH11 genomic library screen and were used as the template for PCR amplification of ssaI, ssbI, and ssaR. To PCR amplify ssbR, the oligonucleotide specific for the 3′ end of ssbR was designed from de novo sequence obtained from pECH101, isolated from the HindIII genomic library. However, only 62 bp of the ssbR sequence was carried on pECH101, due to a HindIII site at this position. R. pomeroyi DSS-3 has silR2 homologous to ssbR (Moran et al., 2004) and based on this sequence a primer designed to the gene presumptively flanking ssbR was generated, and used to PCR amplify the complete ssbR sequence from KLH11.

Directed mutation, lacZ fusions and complementation

For Campbell-type, recombinational mutagenesis internal gene fragments were generated and used to disrupt target genes (Kalogeraki and Winans, 1997). An internal portion of the ssaI gene, was amplified from the pECH100 template using primers designated as 1 and 2 of ssaI. The partial ssaI fragment was gel purified and cloned into pGEM®-T Easy (Promega, Madison, WI), creating pEC103, which was confirmed through sequencing. For recombinational mutagenesis, pEC103 was digested with EcoRI and KpnI, and the resulting ssaI fragment was ligated to a similarly digested R6K replicon, the pVIK112 suicide vector (Kalogeraki and Winans, 1997), creating pEC113. pEC113 was conjugated into KLH11 and transconjugants resistant to kanamycin (Km) were selected and confirmed by sequencing. The ssbI null mutant, designated as EC3, the ssaR null mutant EC4, and the ssbR null mutant EC5 were created similarly to EC2, each using the primers 1 and 2 of these genes and confirmed by sequencing. These plasmid insertions also create lacZ transcriptional fusions in the genes they disrupt. To study the effect of AHL on the luxR-type genes, a fragment of ssaR gene, about 500 bp ending at the stop codon was PCR amplified using primers ssaRintact F and ssaRintact R. The PCR amplicon was cloned into pGEM®-T Easy (Promega, Madison, WI) first and then subcloned into pVIK112, creating pJZ001. The pJZ001 conjugated into KLH11 and transconjugants were selected and confirmed as described above. Thus, the lacZ was fused into the 3′ end of the ssaR gene, keeping ssaR intact. The same approach was used to fuse lacZ into the 3′ end of the ssbR gene while retaining ssbR intact.

To generate in-frame deletions, a standard approach was utilized (Merritt et al. 2007). For the ssaI gene, about 600 bp upstream of ssaI gene was PCR-amplified using primers ssaI D1and ssaI D2 and approximately 400 bp including 206 bp of ssaI encoding sequences and about 200 bp downstream of ssaI was PCR-amplified using primers ssaI D3 and ssaI D4 (Table S3). Primers ssaI D2 and ssaI D3 had complementary sequence at the 5′ end to allow Splicing by Overlapping Extension (SOEing), as described previously (Merritt et al., 2007). In brief, these two fragments were gel purified, followed by PCR amplification with primers ssaI D1 and ssaI D4 using an equal amount of the two fragments as templates. The PCR product of this amplification was gel purified and digested using restriction enzymes SpeI and SphI. The digested PCR product was ligated into the sacB counter-selectable vector pNPTS138 (Hibbing and Fuqua, 2011), which was digested with the same combination of restriction enzymes. Derivatives of pNPTS138 were conjugated into Ruegeria sp. KLH11. The selection of the first crossover was performed by plating transconjugants onto MA 2216 plates with Rif and Km. The colonies that grew on this selective medium, but not on the same plates supplemented with 5% (w/v) sucrose were chosen and subcultured in MB 2216 without Km to allow for excision of the integrated plasmid, followed by plating on 5% sucrose MA2216 plates without Km. Sucrose resistant (SucR) KmS colonies were selected. Deletion of the targeted region was confirmed by PCR. Deletion of ssbI was performed in the same way using primers ssbI D1-ssbI D4. The double deletion of ssaI and ssbI was performed by deleting ssbI in the ssaI deletion strain using the same method as described above.

Controlled expression constructs of ssaI, ssaR, ssbI and ssbR were generated by PCR amplification of the coding regions of each gene using primers designated as 3 and 4 for each specific gene and genomic DNA of KLH11 as template (Table S3). The E. coli lacZ ribosomal binding site was engineered into the 5′ primer of each gene. The PCR products were digested with the appropriate restriction enzyme(s) and ligated into the vector pBBR1-MCS5 (Kovach et al., 1995). The insert carried by each construct was confirmed by sequencing.

Plasmid-borne promoter fusions and expression plasmids

The intergenic region upstream of the ssaI coding sequence and downstream of ssaR contains the presumptive ssaI promoter region and was PCR amplified from pECS102 using primers ssaI P1 and ssaI P4. The upstream and downstream oligos anneal 182 bp upstream, and 3 bp downstream of the ssaI translational start site, respectively. In addition, several plasmid-borne ssaI promoter deletions were also generated using PCR amplification to truncate the 5′ sequences, at positions 79 bp and 63 bp upstream of the ssaI translational start site. These PCR products were cloned into pCR®2.1-TOPO® and their content was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The pCR®2.1-TOPO® derivatives were digested with EcoRI and PstI, and the resulting fragments were ligated with equivalently digested pRA301 vector (Akakura and Winans, 2002). Similarly, the ssbI promoter and translational start site were amplified from KLH11 genomic DNA using primers ssbI P1 and ssbI P4 to generate an amplicon that extends 229 bp upstream and 3 bp downstream of the ssbI predicted translational start site. This amplicon was subsequently used to generate a plasmid-borne PssbI-lacZ fusion on pRA301. Plasmids Plac-ssaR (pEC112) and Plac-ssbR (pEC123) were introduced into the AHL-A. tumefaciens NTL4 in combination with the compatible PssaI-lacZ and PssbI-lacZ plasmids to examine gene regulation patterns in a heterologous, AHL-host.

Preparation of log phase cell concentrates and β-galactosidase assays

β-galactosidase assays for both A. tumefaciens and KLH11 derivatives were performed as described previously (Miller, 1972). Mid-log phase A. tumefaciens cultures were diluted at 1:100 dilution to an OD600~0.01 and were supplemented with different concentration of 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11-HSL. The cell suspension was thoroughly mixed and then aliquoted into 15 ml test tubes, incubated at 28°C for 24 h to an OD600~0.4. Mid-log phase cultures were measured for OD600 and frozen at -20°C and used for subsequent β-galactosidase assays. Cultures of Ruegeria sp. KLH11 were prepared in a similar way. KLH11 was grown in MB 2216 supplemented with Km as required overnight and was diluted at 1:100 dilution to an OD600~0.01. 3-OH-C14 and 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11 were added at the concentration of 20 μM and 2 μM, respectively. Mid-log phase of KLH11 cultures was sampled and β-galactosidase assays were performed immediately.

AHL detection using an ultrasensitive A. tumefaciens reporter for KLH11 derivatives and sponge tissues

AHLs were extracted from KLH11 cultures using dichloromethane, fractionated by reverse phase TLC, and detected using an ultrasensitive AHL bioreporter derived from A. tumefaciens (Zhu et al., 2003, Mohamed et al., 2008b; see Supplementary Methods). Whole M. laxissima individuals were harvested in Key Largo and immediately frozen on dry ice upon surfacing from collection dives. AHLs were extracted using a modified Bligh Dyer procedure (Bligh and Dyer, 1959). Frozen tissue was ground to a powder in liquid nitrogen. To 10 grams of the powder-like tissue, 10 ml of methanol was added and the tube vortexed vigorously prior to overnight incubation. The sample was then vortexed with each addition of 5 ml of chloroform followed by 2.5 ml water and finally 5 ml of chloroform. The chloroform layer was separated and evaporated to dryness. The residue was resuspended in 6 ml of 1:1 isooctane:ethyl ether for solid phase solid phase extraction, as described previously (Gould et al., 2006)

Organic extract from ca. 10.0 g tissues of each of three sponge individuals were dissolved in 40 μl methanol, and 20 μl was loaded onto a C18 RP-TLC plate (Mallinckrodt Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). AHLs were again detected using the A. tumefaciens ultrasensitive reporter (Zhu et al., 2003).

Motility assay, flagellar stain and immunodetection of flagellin

Bacterial swimming assays were performed using MB2216 with 0.25 % (w/v) agar. No antibiotics were added to the medium. Plates were inoculated at the center with freshly isolated colonies. 3-oxo-C16:1 Δ11-HSL was added to MB 2216 agar to 2 μM. Plates were placed in an air-tight container with a beaker containing 15 ml of K2SO4 to maintain constant humidity, and incubated 8 days at 28°C.

Flagellar stains were performed based on methods described by Mayfield and Inniss (1977) and were viewed by phase contrast microscopy. For immunoblotting with anti-flagellin antibodies 5 ml MB2216 cultures (wild type, ssaI-and ssaR-) were grown to late stationary phase. Culture volumes were normalized to an OD600 of 0.6, and portions of these were centrifuged at 716 × g for 12 min to gently separate cells and supernatant. Protein from the whole culture and supernatant fractions was precipitated with an equal volume of 100% trichloroacetic acid. Following vortexing and 15 min incubation on ice, samples were centrifuged (8,765 × g; 20 min) and washed with 1 ml of acetone. The whole culture, pellet, and supernatant fractions were resuspended in 1x SDS lysis buffer, boiled 10 min, and used in subsequent immunoblotting analysis.

Immunoblotting with anti-flagellin polyclonal antibodies raised against C. crescentus whole flagella (a gift from Y.V. Brun) was performed using a standard technique on 15% SDS-PAGE gels transferred to nitrocellulose membranes by electroblotting (see Supplementary Methods). To analyze flagellin biosynthesis across the KLH11 growth curve, samples were taken at a range of times between mid-exponential phase through late stationary phase. 100 ml cultures were grown at 28°C and samples were taken for EC1 (wt KLH11) at OD600 of 0.5, 1.3, 1.8, and 2.2; strain EC2 (ssaI-) OD600 of 0.8, 1.3, 1.7, and 2.4. All samples were processed and analyzed by western blotting and culture samples were also viewed under phase contrast microscopy to evaluate swimming at these time points.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Expression levels of fliC and flaA were measured using q-RT-PCR with specific primers (Table S3). KLH11 and derivatives were grown in MB2216 to an OD600 of 1.8 and 0.5 ml culture was collected and stored in 1 ml RNA Protect Bacterial Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) at -20°C for RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy miniprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), with genomic DNA removed by TURBO DNase (Ambion, Austin, TX), and cDNA synthesized using qScriptTM cDNA SuperMix according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithersburg, MD). The RT-PCR was carried with PerfeCTaTM SYBR® Green FastMixTM Low ROX. Reactions were performed on an Mx3000P qPCR system (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA) using the following cycling parameters: 2 min at 95°C for initial denaturation, 40 cycles for 10 s cycles at 95°C, and 60°C for primer annealing, and a 30 s extension at 72°C. Melt curves were performed to confirm the specificity of primers and the absence of primer dimers. Expression levels of fliC and flaA genes were normalized to the KLH11 vegetative sigma factor 70 gene (rpoD).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR from sponge tissue

Samples of M. laxissima were collected by SCUBA diving at Conch Reef, Key Largo, Florida in late October 2008 at a depth of ca. 20 m as described by Zan et al., (2011). Sponge samples were rinsed 3x with sterile artificial seawater (ASW) and were stored in RNAlater solution (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) immediately for RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted from sponge samples using the TissueLyser system (Qiagen,) and the AllPrep DNA/RNA mini kit (Qiagen). RNAase-free DNAase (Qiagen) was added to RNAeasy mini columns in order to totally remove any DNA. Reverse transcription (RT) reactions were performed by using ssaI specific primer RtaR (Table S3) and ThermoScript RT-PCR system (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). The conditions recommended by the manufacturer were used for the reverse transcription reaction. Primer set RtaF and RtaR were used to amplify the ssaI gene from M. laxissima sponge cDNA. RNA samples without the RT step were used as negative controls to test for contaminating DNA.

Biofilm assays

A standard coverslip biofilm assay was used to evaluate the impact of KLH11 QS on biofilm formation (Tomlinson et al., 2010). Briefly, overnight cultures of different strains were inoculated at OD600~0.06 in 3 ml MB 2216 in UV-sterilized 12-well polystyrene plates and biofilms were grown on sterile PVC coverslips suspended vertically in the wells. The 12-well plates were incubated statically at 28°C over three days. At specific time points, 200 μl of culture was removed to measure the turbidity. The adherent biomass was stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet (CV) solution for 5-10 min and then rinsed gently with DI water to remove loosely attached cells. CV adsorbed to the biofilms was extracted with 33% acetic acid and its absorbance at 600 nm (A600) was measured. These values were normalized by the OD600 of planktonic growth.

To examine inhibition of biofilm formation, wt KLH11 was grown in MB2216 at 28 °C with shaking (200 rpm) to late stationary phase (55–60 h). Bacterial cells were removed from culture volumes of 300 ml by 2 rounds of centrifugation at 5000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μM filter and stored at -80 °C until ready for use. For the biofilm assays to which culture fluids were added the ΔssaI mutant was grown in MB2216 overnight and then diluted to an OD600 ~ 0.06. 2X MB2216 was diluted with the appropriate amounts of culture fluids and water to ensure that there was always at least a 1x concentration of nutrient in the initial biofilm inoculum. Biofilm formation was detected at 48 h as described above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jake Herman for help in the initial stages of this study. The mass spectrometry equipment is supported by the Lipid Maps Large Scale Collaborative Grant (NIH GM069338 to R.C.M.). We acknowledge the National Undersea Research Center (NURC), University of North Carolina at Wilmington for providing sampling opportunities in Key Largo, FL, USA. Dr. Yue Liu is thanked for her assistance in making figures. This study was supported by Grants from the National Science Foundation (MCB #0703467) to C.F. et al., (#0821220) to M.E.A.C., and (#IOS-0919728) to R.T.H.

References

- Ahlgren NA, Harwood CS, Schaefer AL, Giraud E, Greenberg EP. Aryl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing in stem-nodulating photosynthetic bradyrhizobia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17183–17188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103821108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akakura R, Winans SC. Mutations in the occQ operator that decrease OccR-induced DNA bending do not cause constitutive promoter activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15883–15780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson S, Chang CY, Patrick HL, Buckley CMF, Wang Y, Sockett RE, et al. Functional interplay between the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis YpsRI and YtbRI quorum sensing systems modulates swimming motility by controlling expression of flhDC and fliA. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:137–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck von Bodman S, Farrand SK. Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis and pathogenicity in Erwinia stewartii require induction by an N-acylhomoserine lactone autoinducer. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5000–5008. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.5000-5008.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belas R, Horikawa E, Aizawa S, Suvanasuthi R. Genetic determinants of Silicibacter sp. TM1040 motility. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:4502–4512. doi: 10.1128/JB.00429-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–7. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan A, Gonzalez JM, Moran MA. Overview of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:5665–5677. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5665-5677.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicirelli EM, Williamson H, Tait K, Fuqua C. Acylated homoserine lactone signaling in marine bacterial systems. In: Winans SC, Bassler BL, editors. Chemical Communication Among Bacteria. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2008. pp. 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill MEA, Chen LL. Structural basis of acyl-homoserine lactone-dependent signaling. ACS Chemical Reviews. 2011;111:68–85. doi: 10.1021/cr1000817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay KL, Murphy RC. New procedure for isolation of amino acids based on selective hydrolysis of trimethylsilyl derivatives. J Chromatogr. 1979;164:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels R, Vanderleyden J, Michiels J. Quorum sensing and swarming migration in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:261–289. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DG, Parsek MR, Pearson JR, Iglewski BH, Costerton JW, Greenberg EP. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey ME, Caiazza NC, O’Toole GA. Rhamnolipid surfactant production affects biofilm architecture in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1027–1036. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.1027-1036.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine JH, Shadel GS, Baldwin TO. Identification of the operator of the lux regulon from the Vibrio fischeri strain ATCC7744. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5688–5692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl L, Winson MK, Sternberg C, Stewart GSAB, Christiansen G, Chhabra SR, et al. Involvement of N-acyl-L-homoserine lactone autoinducers in control of multicellular behavior of Serratia liquefaciens. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;20:127–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egland KA, Greenberg EP. Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: elements of the luxI promoter. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1197–1204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enticknap JJ, Kelly M, Peraud O, Hill RT. Characterization of a culturable alphaproteobacterial symbiont common to many marine sponges and evidence for vertical transmission via sponge larvae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3724–3732. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3724-3732.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenchel T. Eppur si muove: many water column bacteria are motile. Aquat Microbial Ecol. 2001;24:197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C. The QscR quorum-sensing regulon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: an orphan claims its identity. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3169–3171. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3169-3171.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C, Greenberg EP. Listening in on bacteria: acylhomoserine lactone signalling. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:685–695. doi: 10.1038/nrm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TA, Herman J, Krank J, Murphy RC, Churchill MEA. Specificity of acyl-homoserine lactone synthases examined by mass spectrometry. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:773–783. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.773-783.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TA, Schweizer HP, Churchill MEA. Structure of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa acyl-homoserinelactone synthase LasI. Mol Micro. 2004;53:1135–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gram L, Grossart HP, Schlingloff A, Kiorboe T. Possible quorum sensing in marine snow bacteria: production of acylated homoserine lactones by Roseobacter strains isolated from marine snow. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4111–4116. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.8.4111-4116.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer BK, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:101–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengge R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentschel U, Usher KM, Taylor MW. Marine sponges as microbial fermenters. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2006;55:167–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbing ME, Fuqua C. Antiparallel and interlinked control of cellular iron levels by the Irr and RirA regulators of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:3461–3472. doi: 10.1128/JB.00317-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honag HH, Gurich N, González JE. Regulation of motility by the ExpR/Sin quorum - sensing system in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:861–871. doi: 10.1128/JB.01310-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalogeraki VS, Winans SC. Suicide plasmids containing promoterless reporter genes can simultaneously disrupt and create fusions to target genes of diverse bacteria. Gene. 1997;188:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00778-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kang Y, Choi O, Jeong Y, Jeong JE, Lim JY, et al. Regulation of polar flagellum genes is mediated by quorum sensing and FlhDC in Burkholderia glumae. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:165–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, II, Peterson KM. Four new derivatives of the broad host range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Genes and Dev. 1995;166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasteva PV, Fong JCN, Shikuma NJ, Beyhan S, Navarro MVAS, Yildiz FH, Sondermann H. Vibrio cholerae VpsT regulates matrix production and motility by directly sensing cyclic di-GMP. Science. 2010;327:866–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1181185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]