SUMMARY

The ligand recognition site of A2a-adenosine receptors in rabbit striatal membranes was probed using non-site-directed labeling reagents and specific affinity labels. Exposure of membranes to diethylpyrocarbonate at a concentration of 2.5 mm, followed by washing, was found to inhibit the binding of [3H]CGS 21680 and [3H]xanthine amine congener to A2a receptors, by 86 and 30%, respectively. Protection from diethylpyrocarbonate inactivation by an adenosine receptor agonist, 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine, and an antagonist, theophylline, suggested the presence of two histidyl residues on the receptor, one associated with agonist binding and the other with antagonist binding. Binding of [3H]CGS 21680 or [3H]xanthine amine congener was partially restored after incubation with 250 mm hydroxylamine, further supporting histidine as the modification site. Preincubation with disulfide-reactive reagents, dithiothreitol or sodium dithionite, at >5 mm inhibited radioligand binding, indicating the presence of essential disulfide bridges in A2a receptors, whereas the concentration of mercaptoethanol required to inhibit binding was >50 mm. A number of isothiocyanate-bearing affinity labels derived from the A2a-selective agonist 2-[(2-aminoethylamino)carbonylethylphenylethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (APEC) were synthesized and found to inhibit A2a receptor binding in rabbit and bovine striatal membranes. Binding to rabbit A1 receptors was not inhibited. Preincubation with the affinity label 4-isothiocyanatophenylaminothiocarbonyl-APEC (100 nm) diminished the Bmax for [3H]CGS 21680 binding by 71%, and the Kd was unaffected, suggesting a direct modification of the ligand binding site. Reversal of 4-isothiocyanatophenylaminothiocarbonyl-APEC inhibition of [3H]CGS 21680 binding with hydroxylamine suggested that the site of modification by the isothiocyanate is a cysteine residue. A bromoacetyl derivative of APEC was ineffective as an affinity label at submicromolar concentrations.

Adenosine acts as a neuromodulator in the central and peripheral nervous systems and as a homeostatic regulator in a variety of other systems, including the heart, kidneys, and immune system (1). The biological actions of adenosine are mediated through two adenosine receptor subtypes, A1 and A2. A2 receptors are further divided into high affinity (A2a) and low affinity (A2b) sites. Pharmacologically, the A2 receptor is associated with hypotensive (2), immunosuppressive (3), platelet antiaggregatory (4), and locomotor depressant effects (5) of adenosine agonists. An A2 receptor was recently cloned (6) and, when expressed in COS-7 cells (7), the pharmacological characteristics of the A2a site were observed, i.e., high affinity binding by the A2a selective agonist [3H]CGS 21680 (8, 9) and the stimulation of adenylate cyclase activity by adenosine analogs.

We have attempted to characterize adenosine receptors through the design and use of novel ligand probes, including radioligands (10), photoaffinity probes (10), biotinylated probes (11, 12), fluorescent labels (12), and affinity labels (13, 14), synthesized using a “functionalized congener” approach. An insensitive site on a ligand is derivatized as a chemically functionalized chain (typically terminating in an amino group), to which may be attached a variety of reporter groups that do not preclude high affinity receptor binding. The prototypical A2a-selective amine-functionalized agonist probe is APEC (12), which led to the photoaffinity label 125I-PAPA-APEC (10). This reagent has enabled the identification and characterization of molecular weight and regulatory mechanisms (15) of this receptor in a variety of tissues and cell lines.

A model (16) featuring seven transmembrane helices characteristic of G protein-linked receptors and based on structural analysis of the canine A2 receptor has been proposed. This model predicts a number of possible sites within the central ligand-binding cavity of A2 receptors for its covalent modification. In this report, we have probed the receptor using both affinity labeling by site-directed reactive ligands (12) and chemical modification by non-site-directed reactive agents. Klotz et al. (17) previously reported evidence for the presence of two histidyl residues in the binding site of the A1 receptor, based on inhibition of ligand binding by DEP.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

2-Chloroadenosine and CPX were obtained from Research Biochemicals, Inc. (Natick, MA). The A2 agonists APEC, its derivative PAPA-APEC, and other derivatives were prepared as described (10, 12). [3H] XAC, [3H]PIA, and [3H]CGS 21680 were obtained from DuPont NEN (Boston, MA).

Chemical Synthesis

New compounds were characterized (and resonances assigned) by 300-MHz proton NMR spectroscopy, using a Varian XL-300 NMR spectrometer. Unless noted, chemical shifts are expressed as ppm downfield from trimethylsilane. FAB-MS (positive ions) was measured on a JEOL SX102 high resolution mass spectrometer, using a matrix of glycerol.

Thiourea derivatives of APEC

APEC, 3-isothiocyanatophenylaminothiocarbonyl-APEC (1), 4-isothiocyanatophenylaminothiocarbonyl-APEC (4), and bromoacetyl-APEC, (5) were synthesized as described (12).

Synthesis of 5-aminocarbonyl-3-isothiocyanatophenylaminothiocarbonyl-APEC (2)

3,5-Diisothiocyanatobenzamide (18) (4.7 mg, 20 μmol) was dissolved in 0.5 ml of dry N,N-dimethylformamide and treated with APEC (12) (5.6 mg, 10 μmol), added as a solid. The mixture was sonicated for 5 mm, and the product was purified by HPLC. Aliquots of the reaction mixture were applied to a Vydac C4 protein column (1 × 25 cm), using a mobile phase gradient (20 min) of 20–80% acetonitrile in water, containing 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid, at a flow rate of 3 ml/min. The combined purified fractions (retention time, 13 mm) were reduced in volume by evaporation under a stream of nitrogen and were lyophilized, to provide a 62% recovery of pure product as a white solid. FAB-MS gave peaks at m/z 777 (M + 1), 737, 645, 575, 461, and 369.

Synthesis of 3,5-diisothiocyanatophenylaminothiocarbonyl-APEC (3)

1,3,5-Triisothiocyanatobenzene (4.5 mg, 18 μmol) and APEC (4.8 mg, 8.9 μmol) were combined in 0.5 ml of N,N-dimethylformamide, with sonication until dissolved, and were stirred for 0.5 hr. Dry ether was added, and an oily residue precipitated after remaining refrigerated overnight. The liquid was removed by pipette, and the residue was treated with a minimum of acetonitrile. A solid formed, the acetonitrile was removed with a pipette, and the solid was dried at room temperature under vacuum. The product (yield, 4.5 mg; 64%) was pure by thin layer chromatography (silica plates; chloroform/methanol/acetic acid, 70:25:5, by volume); FAB-MS gave peaks at m/z 791, 737, 705, 645, 584, 553, 461, and 369.

Attempted reaction of 4-methylphenylisothiocyanate with imidazole

Imidazole (0.32 g, 4.7 mmol), dried under high vacuum, was dissolved in 20 ml of methylene chloride and treated with 4-methylphenylisothiocyanate (0.7 g, 4.7 mmol; Fluka). After 2-day storage at room temperature, there was no indication of a reaction by thin layer chromatography (silica plates; ethyl acetate/hexanes, 1:1, by volume). Addition of 5 ml of dry pyridine and heating of the mixture at 50° failed to produce a product distinguishable by thin layer chromatography.

Synthesis of N-acetyl-S-(4-methylphenylaminothiocarbonyl)-l-cysteine

N-Acetyl-S-(4-methylphenylaminothiocarbonyl)-l-cysteine (6) was prepared as a model for the reaction of an aryl isothiocyanate with a cysteine residue. N-Acetyl-l-cysteine (0.41 g, 2.5 mmol; Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee WI) and 4-methylphenylisothiocyanate (0.50 g, 3.3 mmol) were dissolved in 3 ml of dry pyridine and heated at 50° for 1 hr. After cooling, excess aqueous phosphate buffer (pH 7) was added and the neutral solution was extracted with ether. The aqueous layer was separated, acidified with 1 N HC1, and extracted two times with ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate fractions were dried (Na2SO4), and the solvent was evaporated. The amorphous solid residue was identified as the product and was shown to be pure by thin layer chromatography (silica plates; chloroform/methanol/acetic acid, 70:25:5; RF = 0.61), Chemical ionization MS peaks were observed at m/z 313 (M + 1), 181, and 164; NMR in dimethylsulfoxide-d6: δ 8.35 (1 H, d, 7.0 Hz), 7.2–7.5 (4 H), 4.44 (1 H, m), 3.81 (1 H, dd, J = 4.8, 13.6 Hz), 3.4 (1 H), 2.29 (3 H, s), 1.83 (3 H, s); analysis (C13H16N2O3S2): calculated 49.98% C, 5.16% H, 8.97% N; found 49.83% C, 5.21% H, 8.87% N.

Investigation of stability of the dithiocarbamate linkage

N-Acetyl-S-(4-methylphenylaminothiocarbonyl)-l-cysteine (6) was exposed to nucleophiles in stability studies. Although compound 6 is stable in pure form, such dithiocarbamates have been reported to decompose thermally to the starting materials (19). Compound 6 was found to decompose to form more polar products when treated at room temperature with 1 n sodium hydroxide or with hydroxylamine at pH 7. The reaction was followed by HPLC (Altex Ultrasphere-ODS column, 0.46 × 15 cm; using a mobile phase consisting of a mixture of 63% aqueous 60 mm ammonium phosphate monobasic and 5 mm tetrabutylammonium phosphate and 37% 5 mm tetrabutylammonium phosphate in methanol, at a flow rate of 1 ml/min), using a Hewlett-Packard 1090 Series II chromatography system with diode array detection. The retention times were 0.4 mm for N-acetylcysteine and 4.8 min for compound 6.

Biochemical Assays

Preparation of striatal membranes

Striatal tissue was isolated by dissection from rabbit brains obtained frozen from Pel-Freeze Biologicals Co. (Rogers, AR). Membranes were homogenized in the presence of protease inhibitors (5 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin A) in 20 volumes of ice-cold 50 mm Tris·HC1 (pH 7.4), using a Polytron (Kinematica, Gmbh, Luzern, Switzerland) at a setting of 6, for 10 sec. The membrane suspension was then centrifuged at 37,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended (20 mg of tissue/ml) in the aforementioned buffer solution and preincubated at 30° for 30 min with 3 IU/ml adenosine deaminase, and the membranes were again homogenized and centrifuged. Finally, the pellet was suspended in buffer (100 mg of wet weight/ml) and stored frozen for no longer than 2 weeks, at −70°. Protein was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagents (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL).

Treatment of striatal membranes with inhibitors

Membranes were suspended in 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer solution, pH 7.0, and treated with the appropriate amount of DEP (0.2 m stock solution in ethanol) or a disulfide-reactive reagent. The mixture was incubated for 20 min at 25° and either washed by centrifugation (three times, each 8 min at 20,000 × g) in Tris buffer (pH 7.4) or quenched with imidazole (2 mm) for 20 min, as indicated. Adenosine deaminase (3 IU/ml) was present throughout the entire incubation period.

Alternately, the affinity labels derived from APEC (compounds 1–5), at the indicated concentrations, were incubated with the membranes in Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing adenosine deaminase for 1 hr at 25°, and resuspended in Tris buffer and were washed (three times) before radioligand binding. For kinetic experiments with affinity labels, aliquots were removed periodically and quenched with a large volume of buffer solution (15 volumes) before radioligand binding.

Washing cycles for inhibition experiments required resuspending the membrane pellet by gentle vortex mixing, not by stirring or homogenization using the Polytron. At the final step, before radioligand binding, the membranes were homogenized using a glass tissue grinder.

Reversal of inhibition (see text) was studied using successive treatment of the membranes with imidazole (2 mm final concentration in each tube after treatment with the inhibitor) and either hydroxylamine (0.25 m, neutral) or mercaptoethanol (50 mm), during a 20-min incubation in Tris buffer.

Radioligand binding

[3H]CGS 21680 binding was carried out as described (8), using 20 μm 2-chloroadenosine to determine nonspecific binding. Adenosine deaminase was present (3 IU/ml) during the incubation with radioligand. The binding of [3H]XAC to rabbit striatal A2a receptors was measured by the method described (20), which includes 50 nm CPX in the medium to eliminate binding to A1-adenosine receptors For saturation by both agonist and antagonist radioligands, Bmax and Kd values were determined using the Biosoft (Ferguson, MO) computer program for Scatchard analysis, using a linear regression formula. Competition curves were analyzed using Inplot (GraphPAD, San Diego, CA). Binding of 125I-PAPA-APEC to bovine brain A2a receptors was carried out as described (10). Binding of [3H]PIA was carried out as described (12).

Results

The effects of DEP, a reagent for protein covalent modification, on radioligand binding at A2a receptors was examined. Rabbit striatal membranes (prepared in the presence of adenosine deaminase and protease inhibitors, as in all experiments) were preincubated with millimolar concentrations of DEP and washed exhaustively before radioligand binding. Fig. 1 shows that binding of both the antagonist [3H]XAC (in the presence of 50 nm CPX, to eliminate A1 receptor binding) and the agonist [3H]CGS 21680, at fixed concentrations of 1 nm and 5 nm, respectively, to A2a receptors was inhibited irreversibly and in a dose-dependent manner. IC50 values (three experiments) were found to be 4.8 ± 1.0 mm DEP for inhibition of [3H]XAC binding and 0.58 ± 0.08 mm DEP for inhibition of [3H]CGS 21680 binding. The presence of sodium chloride (150 mm) facilitated slightly the inhibition of [3H]XAC binding by DEP, shifting the EC50 value to 3.7 mm DEP.

Fig. 1.

Dose-dependent inhibition by DEP of radioligand binding at A2- adenosine receptors in rabbit striatal membranes. Membranes were incubated (three experiments) with 5 nm [3H]CGS 21680 (●) or 1 nm [3H] XAC in the presence of 50 nm CPX (0). The preincubation was carried out for 15 min at 25°, and the subsequent binding assay involved a 60-min incubated by rapid filtration. The effect on [3H]XAC binding of 150 mm sodium chloride (×) present during the DEP preincubation is also shown.

The Kd value for [3H]CGS 21680 binding at rabbit striatal A2a receptors in control membranes after incubation in the absence of DEP was determined to be 16.0 ± 3.2 nm, with a Bmax value of 219 ± 14 fmol/mg of protein. When 2.5 mm DEP was present during preincubation, Scatchard analysis of binding of [3H]CGS 21680 (Fig. 2) showed that the Bmax of the A2a sites was diminished, with no significant change in the affinity for the radioligand. Kd values for [3H]CGS 21680 binding were 15.2 and 13.4 nm, and Bmax values were 156 and 38 fmol/mg of protein, for 1.0 and 2.5 mm DEP, respectively. The Kd value for [3H]XAC at rabbit striatal A2a receptors was previously found to be 3.8 nm (20). At this concentration, the Kd value of [3H]XAC was unchanged with (4.26 ± 0.08 nm) or without (4.44 ± 0.61 nm) DEP being present during the preincubation, as indicated by Scatchard analysis (Fig. 3), but the Bmax value diminished from 1263 ± 28 to 676 ± 80 fmol/mg of protein with 5 mm DEP.

Fig. 2.

Representative saturation curve (A) and Scatchard plot (B) for the binding of [3H]CGS 21680 to A2-adenosine receptors in rabbit striatal membranes, in the absence (○) or presence (●) of DEP (2.5 mm) in a 20-min preincubation at 25°. Membranes were washed three times with buffer (Tris, pH 7.4) at 4° before radioligand binding. Membranes were incubated with radioligand at 25° for 90 min.

Fig. 3.

Representative saturation curve (A) and Scatchard plot (B) for the binding of [3H]XAC, in the presence of 50 nm CPX, to A2-adenosine receptors in rabbit striatal membranes, in the absence (○) or presence (●) of DEP (5.0 mm) in a 20-min preincubation at 25°. Membranes were washed three times with buffer (Tris, pH 7.4) at 4° before radioligand binding. Membranes were incubated with radioligand at 25° for 1 hr.

The inhibition of radioligand binding by DEP was prevented by the addition of specific adenosine receptor ligands, 1 μM NECA or 1 mm theophylline, to the preincubation medium (Table 1). This indicates that the DEP inhibition is occurring either at the ligand binding site, as proposed for the A1 receptor (17), or at a site that is closely coupled conformationally to the ligand-binding event. As in analogous experiments in which A1 receptors were inhibited by DEP (17), the protection by specific ligands was not of equal magnitude for agonists and antagonists (statistically significant, paired t test). Protecting ligands were more effective at preserving specific binding by the A2a radioligand of the same type, either agonist or antagonist. Thus, during a preincubation with 2.5 mm DEP, NECA protected [3H]CGS 21680 binding to a greater degree than did theophylline, and [3H]XAC binding was preserved in the presence of theophylline to a greater degree than with NECA. Addition of NECA or theophylline during preincubation of membranes with other concentrations of DEP (1 or 5 mm) gave similar findings (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Percentage of protection from DEP inactivation of rabbit A2-adenosine receptors by theophylline and NECA, at different concentrations of DEP.

Data are means ± standard errors of three experiments. Membranes were incubated with 5 nm [3H]CGS 21680 (8) or 1 nm [3H]XAC in the presence of 50 nm CPX (20).

| Concentration of DEP |

Protectiona |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]CGS 21680 |

[3H]XAC |

|||

| NECA (1 μm) |

Theophyine (1 mm) |

NECA (1 μm) |

Theophylline (1 mm) |

|

| mm | % | |||

| 1.0 | 20 ± 2 | 11 ± 2 | NDb | ND |

| 2.5 | 32 ± 3 | 17 ± 2 | 42 ± 1 | 79 ± 1 |

| 5.0 | ND | ND | 38 ± 2 | 67 ± 6 |

100% protection corresponds to the amount of specific binding in untreated control membranes; 0% is defined as residual binding after DEP incubation at each indicated concentration.

ND, not determined.

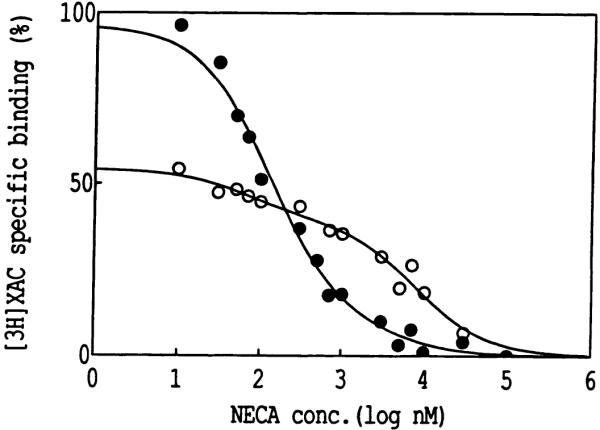

The inhibitory effects of DEP on agonist binding might conceivably occur through uncoupling of receptor-G protein complexes. In principle, a chemical modification that destabilizes the complex would decrease the fraction of receptors in the high affinity state, with respect to agonist binding. Fig. 4 shows the inhibition of [3H]XAC binding by NECA before and after treatment with 5 mm DEP. First, after treatment with DEP the maximum specific binding of [3H]XAC was diminished, consistent with the partial loss of a histidyl residue essential for antagonist binding. Also, it is clear that the shape of the displacement curve was altered by the DEP treatment. The displacement from nontreated membranes occurred with an IC50 of 150 nm (a single high affmity state). After exposure to DEP, a biphasic displacement was evident, corresponding to 27% high affinity sites (IC50, 70 nm) and 73% low affinity sites (IC50, 7600 nm). Thus, DEP not only decreased antagonist binding but also diminished the ability of agonists to form the high affinity state. At very high concentrations (>100 μm) of NECA, the displacement of [3H]XAC from both DEP-treated and untreated membranes, as indicated by residual counts, was similar, so that there was not a pool of [3H]XAC binding that was absolutely undisplaced by the agonist. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

Fig. 4.

Representative inhibition curves for the displacement by NECA of [3H]XAC in the presence of 50 nm CPX binding to rabbit striatal A2-adenosine receptors. Binding was carried out after a 20-min preincubation at 25° in the presence of 5.0 mm DEP (○) and in control membranes (●). Membranes were washed three times with buffer (Tris, pH 7.4) at 4° before radioligand binding. Membranes were incubated with radioligand at 25° for 1 hr.

In addition to DEP, other chemical reagents for protein modification were examined as inhibitors of radioligand binding in rabbit striatal membranes. In particular, the disulfide-reactive reagents (21) dithiothreitol, 2-mercaptoethanol, and sodium dithionite were used. In the model proposed by van Galen et al. (16), one or more disulfide bridges are likely present in extracellular loops of A2a receptors. Thus, there is reason to expect that reducing reagents might inactivate the receptor by opening structurally important disulfide bridges. A preliminary screening of the effects of these reagents was carried out by preincubation followed immediately by radioligand binding, during which time the chemical agent was still present. It was hypothesized that any loss of specific binding by the radioligand would be associated with either covalent modification of amino acid residues of the receptor protein or noncovalent effects on the receptor or its immediate environment. If the modification were covalent, the effects would persist after washing of the membranes, as was the case with DEP.

The results of exposure of rabbit striatal membranes to disulfide-reactive reagents at neutral pH are shown in Fig. 5. Preincubation with dithiothreitol or sodium dithionite inhibited binding at concentrations of >5 mm, whereas the concentrations of mercaptoethanol and hydroxylamine required to inhibit binding were >50 mm. Above these concentrations, the degree of inhibition of binding of [3H]XAC was concentration dependent and nearly complete at the higher concentrations of the reducing reagents tested. The IC50 values were dithionite, 120 mm; dithiothreitol, 220 mm; and mercaptoethanol, 330 mm.

Fig. 5.

Effects of exposure of rabbit striatal membranes to chemical agents. Varying concentrations of sodium dithionite(●), dithiothreitol ○, mercaptoethanol (×), and hydroxylamine ■ were present during a 20-min preincubation at 25°, followed immediately by [3H]XAC(l nm)binding at A2 -adenosine receptors (in the presence of 50 nm CPX).

Because the strongly nucleophilic reagent hydroxylamine is known to reverse the modification of histidyl residues in proteins by DEP (22, 23), we attempted to reverse the DEP effects on A2 receptors at concentrations of hydroxylamine that have a minimal effect on the native receptor, as indicated by radioligand binding. First, it was necessary to show in what concentration range hydroxylamine alone has no effect on radioligand binding. Fig. 5 shows that below 100 mm there was little effect of hydroxylamine on [3H]XAC binding and that the IC50 value for inhibition by hydroxylamine was >500 mm.

Table 2 shows the effect on radioligand binding of DEP treatment followed by quenching with imidazole and then exposure to hydroxylamine (0.25 m). Although treatment of control membranes (not DEP-treated) with the reversal conditions alone (2 mm imidazole followed by 250 mm hydroxylamine) diminished the binding of [3H]CGS 21680 to rabbit A2 receptors by approximately 30%, there was still a reversal of DEP inactivation by hydroxylamine consistently throughout a concentration range of DEP of 1.0–5.0 mm. The results were essentially the same when a washing step was included between treatment with DEP and hydroxylamine. The reversal was more effective when the post-DEP incubation was carried out at 25° for 1 hr, compared with 4° for 24 hr, conditions that were used previously to reverse DEP effects on ADP-ribosyltransferase (22). The restoration of [3H]XAC binding to rabbit A2 receptors after DEP treatment was also observed under these conditions, especially at the lower concentrations of DEP and with the hydroxylamine incubation at 25° for 1 hr (Table 2). [3H]XAC binding after DEP treatment was also completely restored using 50 mm mercaptoethanol (Table 3), but the same reagent failed to restore binding of [3H]CGS 21680.

TABLE 2. Effects of hydroxylamine (pH 7) on the inactivation by DEP of radioligand binding to rabbit A2-adenosine receptors, expressed as percentage of binding relative to control.

Membranes were suspended in 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer solution treated with DEP. The mixture was incubated for 20 min at 25° and quenched with imidazole (2 mm) for 20 min. Adenosine deaminase (3 IU/ml) was present throughout the entire incubation period. This was followed by a 20-min incubation with hydroxylamine (0.25 m) in Tris buffer. Membranes were then subjected to radioligand binding with 5 nm [3H]CGS 21680 or with 1 nm [3H]GAC in the presence of 50 nm CPX, as described (8, 20). Percentages given are the mean or mean ± standard deviation for one to four experiments.

| Concentration of DEP | Binding |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25°, 1 hra |

4°, 24 hra |

|||

| −NH2OH | +NH2OH | −NH2OH | +NH2OH | |

| mm | % of control | |||

| [3H]CGS 21680 | ||||

| 0 | 100 | 64 ± 3 | 100 | 70 ± 1 |

| 1.0 | 63 ± 1 | 76 ± 2b | 61 ± 1 | 68 ± 3 |

| 1.5 | 52 ± 4 | 73 ± 1b | 45 ± 2 | 66 ± 4b |

| 2.0 | 54 ± 1 | 68 ± 2b | 23 ± 3 | 57 ± 4b |

| 2.5 | 39 ± 5 | 54 ± 3 | 15 ± 7 | 39 ± 7 |

| 5.0 | 29 | 42 | 13 | 24 |

| [3H]XAC | ||||

| 0 | 100 | 94 ± 4 | 100 | 90 ± 15 |

| 1.0 | 63 ± 13 | 86 ± 6 | 78 ± 11 | 92 ± 17 |

| 1.5 | 58 ± 8 | 77 ± 4 | 73 ± 13 | 85 ± 16 |

| 2.0 | 45 ± 0 | 57 ± 3b | 61 ± 9 | 80 ± 17 |

| 2.5 | 56 ± 16 | 62 ± 19 | 60 ± 18 | 90 ± 20 |

| 5.0 | 25 | 35 | 25 | 40 |

Condtions during post-DEP incubation.

Difference between control and hydroxytamine-treated values is statistically significant, paired t test (p < 0.05).

TABLE 3. Reversal by mercaptoethanol of A2-edenoslne receptor inactivation by DEP.

Data are means ± standard deviations of three experiments. Membranes were incubated with 5 nm [3H]CGS 21680 (8) or 1 nm [3H]XAC in the presence of 50 nm CPX (20).

| Concentration of mercaptoethanol |

Specific binding |

|

|---|---|---|

| [3H]CGS 21680 | [3H]XAC | |

| mm | % of control | |

| 0 | 28 ± 1 | 55 ± 9 |

| 50 | 18 ± 6 | 113 ± 5 |

Binding site-directed affinity labels for A2a receptors have been synthesized based on a functionalized congener approach (12). The A2a receptor agonist APEC contains a distal amino group located at the terminal position of a chain that is linked to the pharmacophore. The amino group constitutes a site for derivatization by a wide variety of chemical species for the purpose of probing the receptor by radioactive, spectroscopic, or affinity methods. Although several putative affinity labels in this series of APEC derivatives have been reported (12), their efficacy as irreversible inhibitors of A2a receptors has been unexplored until now. We have examined the previously reported potential affinity labels and have modified the structures through chemical synthesis of new analogs.

The cross-linking reagent (13) m-DITC was coupled to APEC, and the product, m-DITC-APEC (compound 1; Table 4), was examined for the ability to inhibit A2a receptors irreversibly. The para-isomer (compound 4) was also prepared. Preincubation of rabbit striatal membranes with a concentration of 100 nm m-DITC-APEC (Fig. 6) resulted in the loss of 68% of the specific binding of 5 nm [3H]CGS 21680 and the loss of 38% of the specific binding of 1 nm [3H]XAC at A2 receptors. At A1-adenosine receptors in rabbit striatal membranes, m-DITC-APEC at 100 nm was ineffective as an affinity label. This selectivity is consistent with the previously determined A2a selectivity (9, 12) of this derivative and its precursor, APEC. This is also in contrast to receptor binding inhibition by DEP (Fig. 6), which is a non-site-directed agent and, as such, affects A1 and A2 receptors indiscriminately.

Table 4. Inhibition of binding of [3H]CGS 21680 at rabbit A2-adenosine receptors by affinity labels derived from the A2-selective agonist APEC.

Control values were, before incubation with affinity labels, Kd = 28.6 ± 2.57 nm and Bmax = 237 ± 3.3 fmol/mg of protein (three experiments) and, after incubation with inhibitor buffer alone, Kd = 24.5 ± 1.81 nm and Bmax = 220 ± 9.7 fmol/mg of protein (three experiments). Percentages given are the mean or mean ± standard deviation for one to three experiments, (n)

| Compound | R | Concentration | K d a | B max a | Decrease in Bmax | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | nm | fmol/mg of protein | % | |||

| 1 |

|

20 100 |

22.1 23.0 ± 0.2 |

178 134 ± 24 |

19 39 |

1 3 |

| 2 |

|

100 | 25.6 ± 0.4 | 74.6 ± 3.5 | 66 | 2 |

| 3 |

|

100 | 23.9 ± 2.1 | 51.0 ± 1.5 | 77 | 2 |

| 4 |

|

100 250 |

28.5 ± 0.2 29.2 ± 4.6 |

72.2 ± 17.5 45.3 ± 9.4 |

71 80 |

2 2 |

| 5 | NHCSNHCOCH2Br | 100 250 |

25.7 ± 1.1 22.5 ± 0.4 |

239 ± 13 213 ± 8 |

0 0 |

2 2 |

Treated membranes.

Fig. 6.

Radioligand binding at A1 ([3H]PIA) and A2 ([3H]XAC and [3H]CGS 21680) adenosine receptors in rabbit striatal membranes after a 20-min treatment at 25° with 2.5 mm levels of a non-site-directed inhibitor, DEP (■), or 100 nm levels of an A2-selective site-directed affinity label, m-DITC-APEC (1) (■) [3H]XAC and [3H]PIA were present at a concentration of 1 nm and [3H]CGS 21680 was present at a concentration of 5 nm(three experiments).

The irreversible nature of inhibition by the isothiocyanate derivatives was further demonstrated by the failure of repeated washing to regenerate the A2a receptor binding site. Incubation of rabbit striatal membranes with 100 nm p-DITC-APEC (4) resulted in inhibition of 77% of [3H]CGS 21680 binding after centrifugation and two additional washing steps). After three to six washes, the level of inhibition remained constant at 76 ± 1%. Exposure of the p-DITC-APEC-treated striatal membranes to 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine overnight also did not regenerate A2a receptor binding.

Saturation of binding of [3H]CGS 21680 to rabbit striatal receptors after treatment with m-DITC-APEC (1), at 20 nm (Fig. 7, upper) or 100 nm (Fig. 7, lower), and washing indicated a reduction in the Bmax values, relative to control membranes, without a major effect on the Kd value at the remaining sites. For 100 nm m-DITC-APEC, the Kd value for [3H]CGS 21680 binding was 23 nm and the Bmax value was 134 fmol/mg of protein, compared with 24.5 nm and 220 fmol/mg of protein for control. The fraction of receptors inactivated by this isothiocyanate derivative increased as the concentration of m-DITC-APEC was raised.

Fig. 7.

Saturation curves for the binding of [3H]CGS 21680 to A2-adenosine receptors in rabbit striatal membranes, in control membranes and after treatment (1-hr preincubation at 25°) with 20 nm (upper) or 100 nm (lower) m-DITC-APEC. The volume of incubation for radioligand binding (approximately 150 μg of protein/tube) was 1 ml. Membranes were incubated with radioligand at 25° for 90 min. Total binding in control (●) and treated ○ membranes is shown. Nonspecific binding in control (×) and treated (Δ) membranes was nearly identical.

Inhibition of binding of [3H]CGS 21680 or [3H]XAC at A2a receptors by m-DITC-APEC, at 20 nm or 100 nm (Fig. 8), could be prevented by specific adenosine receptor ligands. The receptor was protected in the presence of either 1 μm NECA or 1 mm theophylline, with degrees of protection of 60–80% for 20 nm m-DITC-APEC and 30–50% for 100 nm m-DITC-APEC. However, unlike the case of DEP inactivation, saturating concentrations of these agonist and antagonist ligands had nearly identical effects on [3H]CGS 21680 or [3H]XAC binding (for the same concentration of m-DITC-APEC).

Fig. 8.

Protection by NECA and theophylline of A2a-adenosine receptors in rabbit striatal membranes during a 20-min preincubation at 25° with 20 nm ○ or 100 nm 4 concentrations of the affinity label m-DITC-APEC (1), as indicated by binding of [3H]CGS 21680 (5 nm) and [3H]XAC (1 nm).

Based on these findings of selective and irreversible inhibition by m-DITC-APEC, other affinity labels were prepared. The 5-position of the isothiocyanate ring was substituted in compounds 2 and 3. Compound 2 contains a 5-carboxamido group, and compound 3 contains an additional chemically reactive isothiocyanate group, a “trifunctional” reagent (18). Both modifications resulted in enhanced irreversible inactivation of rabbit A2 receptors (Table 4). Compound 4, the para-isomer of DITC-APEC, was also particularly potent as an irreversible inhibitor of the receptor, and the time course for inactivation that was not reversed by washing was rapid (Fig. 9). At 100 nm, approximately 13 min was required for inhibition of 50% of the receptor sites. This concentration is only 10-fold greater than the apparent Ki value for p-DITC-APEC (9.9 ± 4.0 nm; five experiments) in a “competitive” binding assay versus [3H]CGS 21680. Curiously, the presence of the electrophilic group on N-bromoacetyl-APEC, (5) failed to produce irreversible inhibition of the receptor. Thus, compound 5, being a high affinity, reversibly binding ligand in the same chemical series, served as an additional control for demonstrating irreversible inactivation by the closely structurally related compounds 1–4.

Fig. 9.

Time course for inhibition of rabbit striatal A2a-adenosine receptors, at 25° by 100 nm p-DITC APEC (4). [3H]CGS 21680 was used at a concentration of 5 nm. This curve is representative of data from four separate experiments.

A2a receptors in bovine striatum have been studied thoroughly in binding and functional assays (10, 12). Compounds 1 and 4 were also found to inhibit irreversibly the binding of 125I-PAPA-APEC to A2a receptors in bovine striatum (Table 5). As in the rabbit brain, only the Bmax value was substantially diminished by preincubation with the isothiocyanate derivative. Unlike in the rabbit brain, there was no clear difference between meta- (1) and para- (4) isomers in the ability to inhibit bovine A2a receptors irreversibly.

TABLE 5. Inhibition of 125I-PAPA-APEC binding to A2-adenosine receptors in bovine brain after preincubation with adenosine isothiocyanate derivatives (20 nm).

Data are from saturation experiments using 125I-PAPA-APEC, as described (10, 28). Bmax values are given as percentage decrease from control.

| Compound |

Kd

|

Decrease in Bmax |

n a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Treated | |||

| mm | % | |||

| 1 | 2.3 ± 0.0 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 38.7 ± 4.9 | 6 |

| 4 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.67 ± 0.4 | 46.8 ± 3.2 | 5 |

n, number of experiments.

We attempted to reverse the inhibition by the isothiocyanate-bearing affinity labels using chemical reagents, to determine the identity of the receptor residue covalently modified. A number of neurotransmitter receptors have been modified using affinity ligands bearing isothiocyanate groups, but it is uncommon for the site of reaction on the receptor protein to be identified. Model compounds for the reaction of an isothiocyanate group with nucleophiles (19, 24) were prepared for the purposes of comparison and prediction (see Discussion).

Table 6 shows that hydroxylamine (0.25 m) partially restored the binding of the agonist [3H]CGS 21680 to rabbit A2a receptors, after inhibition with p-DITC-APEC (4). In contrast, hydroxylamine treatment failed to reverse the inhibition of antagonist ([3H]XAC) binding by this adenosine agonist affinity label.

TABLE 6. Reversal by hydroxylamine of A2-adenosine receptor inactivation by p-DITC-APEC (100 nm).

Data are means ± standard deviations of three experiments. After treatment with DEP, the membrane suspensions were quenched with 2 mm imidazole for 20 min, followed by hydroxylamine. For radioligand binding, membranes were incubated with 5 nm [3H]CGS 21680 (8) or 1 nm [3H]XAC in the presence of 50 nm CPX (20).

| Concentration of NH2OH |

Specific binding |

|

|---|---|---|

| [3H]CGS 21680 | [3H]XAC | |

| mm | % of control | |

| 0 | 22 ± 3 | 66 ± 4 |

| 250 | 62 ± 5 | 70 ± 4 |

Discussion

Klotz et al. (17) reported that the A1-adenosine receptor is subject to irreversible inhibition by the histidine-modifying reagent DEP. This effect was found to be enhanced by sodium ions (25). Inhibition of binding of both agonist and antagonist radioligands was observed. Protection from this inhibition by adenosine receptor ligands in the presence of DEP was skewed towards higher effectiveness of antagonists to preserve binding of the antagonist [3H]CPX and of agonists to preserve binding of [3H]PIA, an agonist radioligand. This suggested the presence of two histidine residues in the receptor binding cavity, one having greater influence over agonist binding and the other being more closely associated with antagonist binding. DEP is also known to react with tyrosyl residues (23), although not as readily as with histidyl residues, and to a lesser degree with other nucleophilic side chains.

With the development of an antagonist binding assay (20) for striatal A2a receptors in the rabbit brain (using [3H]XAC in the presence of 50 nm CPX), we were able to examine the ability of DEP to inhibit the binding site of A2a receptors. The inhibition results with A2a receptors were very similar to those observed for DEP inhibition of A1 receptors (17).

A provisional conformational model for A1 and A2a receptors proposed by van Galen et at. (16) predicts that two histidyl residues in the transmembrane helical regions are important for ligand binding. These histidyl residues are conserved between A1 and A2a receptors and across species (at least for A1 receptors) and do not occur in the G protein-linked biogenic amine receptors. Because rabbit and bovine A2a receptor sequences are not known, we have analyzed the canine sequences (the transmembrane regions of adenosine receptors are nearly entirely conserved across species). For the canine A1 receptor, these correspond to His250 on transmembrane helix VI and His278 on transmembrane helix VII; on the canine A2a receptor sequence (Fig. 10), the homologous residues are His250 and His278. These residues may be the sites of modification by DEP (16), as shown previously for the A1 receptor (17) and in this work for the A2a receptor. Results with both receptors are parallel; the binding of agonist and antagonist radioligands is inhibited by exposure to millimolar concentrations of DEP, and selective protection by competing agonists and antagonists is observed.

Fig. 10.

Transmembrane model of the canine A2-adenosine receptor, as proposed by van Galen et al. (figure reproduced from Ref. 16 with permission from authors).

An alternate hypothesis is that there is another histidine residue, not located in the transmembrane region, that is modified by DEP and this modification affects agonist ligand binding by interfering with the G protein coupling of the receptor. In the canine A2a receptor, His230 occurs on the third intracellular loop (Fig. 10). The involvement of the histidines conserved in helices VI and VII, and of other histidines, will be best addressed by site-directed mutagenesis studies.

Hydroxylamine has been shown to reverse the acylation by DEP of histidine in proteins (22, 23). The reversal by hydroxylamine of DEP-induced (1–2 mm) inactivation of A2 receptors (Table 2) further supports of the involvement of two histidine residues associated with ligand binding in rabbit A2a receptors. Although hydroxylamine may potentially cleave the peptide backbone of proteins, no major loss of [3H]CGS 21680 binding ability in unmodified A2a receptors was observed upon application of hydroxylamine in the millimolar range. At higher DEP concentrations reversal was less pronounced, especially in the case of [3H]XAC binding. The incomplete reversal by hydroxylamine may be a result of 1) modification of other residues of the receptor protein that are essential for antagonist but not agonist binding or 2) the occurrence of a truly irreversible side reaction of DEP on imidazoles, in which the imidazole ring of histidine would be opened to an acyclic form. The latter reaction, known as the Bamberger reaction (26), is a result of the concurrent acylation of both the τ and π-nitrogens of the imidazole group. Both possible mechanisms to explain the incomplete reversal by hydroxylamine would be expected to be dependent on higher concentrations of DEP, as is the case for [3H]XAC binding. Even for [3H]CGS 21680 binding, the reversal by hydroxylamine of receptor inhibition is more effective at 1 mm DEP than at higher DEP concentrations.

Based on the selective protection from DEP-induced inactivation of [3H]CGS 21680 and [3H]XAC binding, by NECA and theophylline, respectively (Table 1), it appears that agonists and antagonists interact with different histidyl residues at the A2a receptor binding site. The ability of mercaptoethanol to reverse the DEP inhibition of [3H]XAC binding alone further emphasizes that there is selective accessibility and/or reactivity of the antagonist- versus agonist-related histidyl residues.

Using a membrane preparation containing native A2a receptors, it has not been possible to establish whether the site of histidine modification that affects agonist binding is located in the immediate vicinity of the ligand binding region (i.e., on one of the transmembrane helices) or on the third intracellular loop (Fig. 10). Chemical modification of either of these sites might potentially affect receptor-G protein coupling and, thus, agonist binding. The degrees of protection by theophylline and by NECA (from inhibition by DEP of radioligand binding) (Table 1) are qualitatively similar to the results obtained for the rat A1 receptor (17), which has no histidyl residue in the third intracellular loop (27). Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that both DEP-modified histidyl residues, in the A2a receptor as well as in the A1 receptor, are likely in the transmembrane region.

The ability of reducing reagents such as mercaptoethanol, dithiothreitol, and sodium dithionite, at high concentrations, to inactivate the A2a receptor suggests that there are structurally important disulfide bridges on the receptors protein. Possible sites for such disulfide linkages have been discussed in the sequence analysis (16). Perhaps even more significant, in relation to the design of new affinity probes, is the finding that lower concentrations of mercaptoethanol (in the millimolar range) do not disrupt receptor binding. Cross-linking reagents containing thiol-cleavable or dithionite-cleavable spacer groups are used commonly and, thus, such reagents may now be applied to the study of A2a receptors.

Chemical affinity labels for A1 receptors (14, 18) have been synthesized by using a functionalized congener approach to the design of adenosine agonists and antagonists. In previous work, the homobifunctional reagents m- and p-DITC gave rise to XAC conjugates that covalently labeled bovine A1 receptors to the extent of 94 and 73%, for meta- and para-isomers, respectively, after incubation at 500 nm (13). We have now extended this approach to A2a receptors and have introduced the first chemical affinity labels for this receptor subtype. The APEC derivatives (Table 4) that were shown to inhibit radioligand binding irreversibly are selective for this subtype, and the irreversible receptor modification occurs at relatively low concentrations. The density of A2a binding sites in the membrane was diminished, without affecting the affinity of [3H]CGS 21680 for the remaining A2 receptors. This is consistent with the uniform and total inhibition by the affinity label of a fraction of the A2a receptors that increases with the concentration of the affinity label, without modification of the remaining sites. The parallel behavior of theophylline and NECA to prevent this inhibition for agonists and antagonists suggests that the APEC-derived affinity labels effectively block the entire ligand-binding region of the receptor. This is in contrast to inhibition by the small molecule DEP, which blocks both agonist and antagonist sites, but these sites may be distinguished partially with the addition of structurally simple purine ligands, such as NECA or theophylline.

Isothiocyanates can react with alkyl amino groups to produce stable thioureas (24). The site for modification by the isothiocyanate group of compound 4 is likely not a primary amino group, because the linkage is labile to hydroxylamine treatment. The binding site for [3H]CGS 21680 was regenerated chemically (Table 6). Thus, the site on the receptor protein for covalent attachment of the isothiocyanate group appears not to be at the amino terminus or at a lysine residue.

Alternately, isothiocyanates may react with other nucleophilic amino acid side chains. First, we attempted to couple an isothiocyanate (4-methylphenylisothiocyanate) to imidazole (see Experimental Procedures), as a model for the reaction with a histidine residue. A stable product could not be isolated or observed by thin layer chromatography, even in the presence of pyridine; thus, histidine is not a likely site for reaction of compound 4.

Finally, isothiocyanates are known to react with thiols (19, 24). The product of reaction with an amine, i.e., a thiourea, is expected to be stable to hydroxylamine treatment (24). However, a dithiocarbamate, such as would result from modification of a cysteine residue, is less stable. Indeed, a model compound, resulting from the reaction of N-acetylcysteine with p-methylphenyliosothiocyanate, was unstable to treatment with hydroxylamine at neutral pH. If a cysteine residue is the site of modification, it is unknown whether a native thiol group is regenerated or another product is formed in the presence of hydroxylamine. Cysteine residues are present on the transmembrane helices of canine A2a receptors (6, 16). Because hydroxylamine treatment after exposure of rabbit striatal membranes to compound 4 restored the binding of [3H]CGS 21680 but did not restore [3H]XAC binding (Table 6), it is possible that the integrity (in the native form) of the residue that is the site of modification by compound 4 is more essential for antagonist binding than for agonist binding.

It is now possible to design trifunctional affinity labels (18) for A2a receptors, because substitution is tolerated at the 5-position of the isothiocyanate-bearing ring, as in compounds 2 and 3. Compound 3, an APEC derivative in which two isothiocyanate groups are present, is a very potent irreversible inhibitor of A2a receptors. After covalent binding, if the second isothiocyanate group remains intact, a chemically “functionalized receptor” will have resulted. Such an affinity-labeled and reactive receptor is potentially useful for cross-linking to other nucleophilic moieties or possibly for forming intramolecular linkages within the protein. Other trifunctional reagents derived from APEC could be used for the introduction of a label, such as fluorescent dye, or a biotin moiety (18).

The advantage of using a binding site-directed chemical label is seen in Fig. 5, in which it was shown that the residue-selective but non-binding site-directed agent DEP inactivates both A1 and A2a receptors indiscriminately. In contrast, the affinity label m-DITC-APEC, derived from an A2a-selective functionalized congener, substantially inhibits binding to A2a receptors at a concentration at which A1 receptor binding was unaffected.

We have selected the rabbit striatum for this study due to the availability of both agonist and antagonist (20) radioligand binding assays in this tissue. It is understood that species differences likely exist in ligand affinity, selectivity, and the concentrations at which the irreversible inhibitors of A2 receptors are effective. In bovine brain, the APEC derivatives 1 and 4 were, indeed, effective irreversible inhibitors at concentrations comparable to those used with rabbit striatal membranes. It was shown that the rabbit brain A2 receptor is subject to proteolytic cleavage during handling (28), thus, we have included a mixture of proteolytic inhibitors known to prevent this breakdown.

With the long chain of the functionalized congener, it is conceivable that the site of labeling would occur at a distal site on the receptor or even on a membrane component other than the receptor but in proximity to it. This is unlikely, for several reasons. Preincubation with electrophilic derivatives of APEC diminished the Bmax for [3H]CGS 21680 binding but did not affect the Kd, suggesting a direct modification of the ligand binding site. By analogy, the isomers of DITC-XAC are functionalized congeners bearing long chains with a span of ≥17 bonds from the pharmacophore to the isothiocyanate, yet the site of labeling was shown to occur on the receptor binding subunit (14).

Such selective inhibitors are potentially of interest in physiological studies, before which it will be necessary to study the selective inhibitory and reversing effects on adenylate cyclase stimulation by A2 receptors. Also, the APEC derivatives and other inhibitors are of potential utility in the characterization of both the receptor and receptor fragments, possibly in conjunction with site-directed mutagenesis experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. P. J. M. van Galen for helpful discussions concerning adenosine receptor models. We acknowledge the technical assistance of Garnet Pinder, Dr. L. Pu, and Marc Glashofer.

ABBREVIATIONS

- APEC

2-[(2-aminoethylamino)carbonylethylphenylethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- CGS 21680

2-(carboxyethylphenylethylamino)adenosine-5′-carboxamide

- CPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- DEP

diethylpyrocarbonate

- DITC

phenylenediisothiocyanate

- NECA

5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- PAPA

p-aminophenylacetyl

- PIA

N6-phenylisopropyladenosine

- XAC

xanthine amine congener (8-[4-[[[[(2-aminoethyl)-amino]carbonyl]methyl]oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthmne)

- G protein

guanine nucleotide-binding protein

- MS

mass spectrometry

- FAB

Fast atom bombardment

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

Contributor Information

KENNETH A. JACOBSON, Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892

GARY L. STILES, Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27710

XIAO-DUO JI, Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892.

References

- 1.Williams M, editor. Adenosine Receptors. Humana Press; Clifton, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsson RA, Pearson JD. Cardiovascular purinoceptors. Physiol. Rev. 1990;70:761–845. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cronstein BN, Daguma L, Nichols D, Hutchison AJ, Williams M. The adenosine/neutrophil paradox resolved: human neutrophils possess both A1, and A2 receptors that promote chemotaxis and inhibit O2 generation, respectively. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;85:1150–1157. doi: 10.1172/JCI114547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohse MJ, Elger B, Lindenborn-Fotinos J, Klotz KN, Schwabe U. Separation of solubilized A2 adenosine receptors of human platelets from non-receptor [3H]NECA binding sites by gel filtration. Naunyn-Schmiede-bergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1988;337:64–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00169478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikodijevic O, Sarges R, Daly JW, Jacobson KA. Characterization of A1- and A2-adenosine receptor-mediated components in locomotor depression elicited by adenosine agonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;259:286–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libert F, Parmentier M, Lefort A, Dinsart C, van Sande J, Maenhaut C, Simons MJ, Dumont JE, Vassart G. Selective amplification and cloning of four new members of the G protein-coupled receptor family. Science (Washington D. C.) 1989;244:569–572. doi: 10.1126/science.2541503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maenhaut C, van Sande J, Libert F, Abramowicz M, Parmentier M, Vanderhaegen J-J, Dumont JE, Vassart G, Schiffmann S. RDC8 codes for an adenosine A2 receptor with physiological constitutive activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;173:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80909-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarvis MF, Schutz R, Hutchison AJ, Do E, Sills MA, Williams M. [3H]CGS 21680, a selective A2 adenosine receptor agonist, directly labels A2 receptors in rat brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;251:888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hide I, Padgett WL, Jacobson KA, Daly JW. A2a-Adenosine receptors from rat striatum and rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells: characterization with radioligand binding and by activation of adenylate cyclase. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;41:352–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrington WW, Jacobson KA, Williams M, Hutchison AJ, Stiles GL. Identification of the A2 adenosine receptor binding subunit by photoaffinity cross-linking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:6572–6576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson KA, Kirk KL, Padgett W, Daly JW. Probing the adenosine receptor with adenosine and xanthine biotin conjugates. FEBS Lett. 1985;184:30–35. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80646-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson KA, Barrington WW, Pannell LK, Jarvis MF, Ji X-D, Williams M, Hutchison AJ, Stiles GL. Agonist derived molecular probes for A2 adenosine receptors. J. Mol. Recognition. 1989;2:170–178. doi: 10.1002/jmr.300020406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson KA, Barone S, Kammula U, Stiles GL. Electrophilic derivatives of purines as irreversible inhibitors of A1 adenosine receptors. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:1043–1051. doi: 10.1021/jm00125a019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. High affinity acylating antagonists for the A1 adenosine receptor: identification of binding subunit. Mol. Pharmacol. 1988;34:724–728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramkumar V, Olah ME, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Distinct pathways of desensitization of A1- and A2-adenosine receptors in DDT1MF-2 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991;40:639–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Galen PJM, Stiles GL, Michaels G, Jacobson KA. Adenosine A1 and A2 receptors: structure-function relationships. Med. Res. Rev. 1992;12:423–471. doi: 10.1002/med.2610120502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klotz K-N, Lohse MJ, Schwabe U. Chemical modification of A1, adenosine receptors in rat brain membranes: evidence for histidine in different domains of the ligand binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:17522–17526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boring DL, Ji X-D, Zimmet J, Taylor KE, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. Trifunctional agents as a design strategy for tailoring ligand properties: irreversible inhibitors of Al adenosine receptors. Bioconjugate Chem. 1991;2:77–88. doi: 10.1021/bc00008a002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen C, Jakobsen P. Thermal fragmentations. VI. The preparation of aryl N-monoalkyldithiocarbamates and their behaviour upon heating. Acta Chem. Scand. 1973;27:2001–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji X-D, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. [3H]XAC (xanthine amine congener) is a radioligand for A2-adenosine receptors in rabbit striatum. Neurochem. Int. 1991;18:207–213. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(91)90187-i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fonseca MI, Lunt GG, Aguilar JS. Inhibition of muscarinic cholinergic receptors by disulfide reducing agents and arsenicals: differential effect on locust and rat. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1991;41:735–742. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90074-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer PI, Buki KG, Kun E. Evidence for the participation of histidine residues located in the 56 kDa C-terminal polypeptide domain of ADP-ribosyl transferase in its catalytic activity. FEBS Lett. 1990;273:6–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81038-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miles E. Modification of histidine residues in proteins by diethylpyrocarbonate. Methods Enzymol. 1977;48:431–443. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(77)47043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walter W, Bode K-D. Neuere Methoden der präparatativen organischen Chemie. VI. Synthesen von Thiourethanen. Angew. Chem. 1967;79:285–328. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garritsen A, Ijzerman AP, Beukers MW, Soudijn W. Chemical modification of adenosine A1 receptors: implications for the interaction with R-PIA, DPCPX and amiloride. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1990;40:835–842. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90324-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grace ME, Loosemore MJ, Semmel ML, Pratt RF. Kinetics and mechanism of the Bamberger cleavage of imidazole and of histidine derivatives by diethyl pyrocarbonate in aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:6784–6789. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahan LC, McVittie LD, Smyk-Randall EM, Nakata H, Monsma FJ, Gerfen CR, Sibley DR. Cloning and expression of an A1, adenosine receptor from rat brain. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991;40:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nanoff C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. The A2 adenosine receptor: guanine nucleotide modulation of agonist binding is enhanced by proteolysis. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991;39:130–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]