Abstract

Background

Radial artery access for coronary angiography and interventions has been promoted for reducing hemostasis time and vascular complications compared to femoral access, yet it can take longer to perform and is not always successful, leading to concerns about its cost. We report a cost-benefit analysis of radial catheterization, based on results from a systematic review of published randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Methods and results

The systematic review added five additional RCTs to a prior review, for a total of 14 studies. Meta-analyses, following Cochrane procedures, suggested that radial catheterization significantly increased catheterization failure (OR 4.92, 95% CI 2.69–8.98), but reduced major complications (OR 0.32, CI 0.24–0.42), major bleeding (OR 0.39, CI 0.27–0.57) and hematoma (OR 0.36, CI 0.27–0.48) compared to femoral catheterization. It added approximately 1.4 minutes to procedure time (CI −0.22 to 2.97), and reduced hemostasis time by about 13 minutes (CI −2.30 to −23.90). There were no differences in procedure success rates or major adverse cardiovascular events.

A stochastic simulation model of per-case costs took into account procedure and hemostasis time, costs of repeating the catheterization at the alternate site if the first catheterization failed, and the inpatient hospital costs associated with complications from the procedure. Using base-case estimates based on our meta-analysis results, we found the radial approach cost $275 (95% CI: −$374 to −$183) less per patient from the hospital perspective. Radial catheterization was favored over femoral catheterization under all conditions tested.

Conclusion

Radial catheterization was favored over femoral catheterization in our cost-benefit analysis.

Keywords: Coronary angiography, heart catheterization, radial artery, femoral artery, cost-benefit analysis, meta-analysis

Introduction

There is an increasing interest in the use of radial artery access for coronary angiography and interventions, with proponents arguing that the technique is associated with lower rates of bleeding and major vascular complications, improved patient comfort, and shorter times to hemostasis and ambulation than femoral access.

Despite these possible benefits, detractors have pointed to the longer procedure times and access failures associated with radial artery access. As a result, the use of radial access varies widely by practitioner, institution, and region. Radial artery access is the primary mode of access in several European countries, Canada and Japan, while used in the minority of catheterizations in the United States.1, 2

Using a systematic review of randomized studies comparing radial and femoral artery vascular access, we performed a cost-benefit analysis from the hospital perspective to evaluate whether the reduction in procedure-related complications and reduction in hemostasis times attributable to radial artery catheterization would offset the increased procedure time and failure rate of radial catheterization. This information can then be used to support a local decision to switch to radial catheterization or continue using femoral catheterization.

Methods

Overview

We updated a previously published systematic review3 to obtain the most up-to-date probability and cost estimates for our cost-benefit analysis. We then developed a stochastic simulation model to determine the incremental per-case cost of radial versus femoral catheterization. The component costs of radial and femoral catheterization were identified, and the incremental costs were calculated as the product of an estimated unit cost and an estimated frequency at which the cost would be incurred. So for example, the estimated cost per case of procedure time is the per-minute cost of procedure time (Cpt) multiplied by the procedure time difference between radial and femoral catheterization (Tpt); and the estimated per-case cost of major bleeding complications is the cost of a major bleed (Cmb) multiplied by the difference in the probability of a major bleed (Pmb) between radial and femoral catheterization. The model outcome, the incremental cost of radial versus femoral catheterization, is shown in Equation 1 and the component variables in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables included in cost-benefit model

| Variable | Definition | Baseline | Range | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Costs (US$ per event) | ||||

| Cpt | Cost of procedure time (US$/minute) | 15.55 | 15.55 to 62.20 | Local data |

| Cht | Cost of hemostasis time (US$/minute) | 1.75 | 0 to 15.55 | FAME4 |

| Cas | Cost of converting between radial and femoral access (catheterization at alternate site) | 35 | 0 to 120 | FAME4 |

| Cmc | Cost of a minor complication | 2,282 | 1,325 to 3,238 | ACUITY5 |

| Ch | Cost of a hematoma | 3,779 | 1,890 to 7,558 | GUSTO6 |

| Cvc | Cost of a vascular complication | 6,377 | 3,189 to 12,754 | Kugelmass7 |

| Cmb | Cost of a major bleeding event | 6,739 | 5,585 to 8,784 | Mean and range of 5 studies |

|

| ||||

| Durations (minutes) | ||||

| Tpt | Difference in procedure time with radial access | 1.38 | −0.22 to 2.97 | Meta-analysis |

| Tht | Difference in hemostasis time with radial access | 13.07 | −23.9 to −2.3 | Meta-analysis |

|

| ||||

| Complication Probabilities with Femoral Catheterization | ||||

| Pas | Probability of failed catheterization (catheterization at alternate site) | 1.89% | – | Meta-analysis |

| Pmc | Probability of minor complication | 5.70% | – | Meta-analysis |

| Ph | Probability of hematoma | 2.02% | – | Meta-analysis |

| Pvc | Probability of vascular complication | 2.53% | – | Meta-analysis |

| Pmb | Probability of major bleeding | 1.11% | – | Meta-analysis |

|

| ||||

| †Complication Probabilities with Radial Catheterization | ||||

| Pas | Probability of failed catheterization (catheterization at alternate site) | 9.30% | 5.08% to 16.97% | Meta-analysis |

| Pmc | Probability of minor complication | 2.22% | 1.54% to 3.25% | Meta-analysis |

| Ph | Probability of hematoma | 0.73% | 0.55% to 0.97% | Meta-analysis |

| Pvc | Probability of vascular complication | 0.81% | 0.61% to 1.06% | Meta-analysis |

| Pmb | Probability of major bleeding | 0.43% | 0.30% to 0.63% | Meta-analysis |

Cost values were varied in one-way sensitivity analyses; all other variables were modeled as triangular distributions

Meta-analysis used femoral catheterization times as baseline and calculated incremental time for corresponding radial times

| Equation 1 |

Systematic review and meta-analysis

To estimate the cost of complications in catheterization procedures and the cost of unsuccessful catheterizations, we first must have evidence-based estimates of rates for these events. A systematic review providing these estimates was published by Jolly et al.3 in 2009. We updated the systematic review and meta-analysis with data published from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing radial and femoral catheterization.

Our review followed procedures set out in the PRISMA statement. Systematic searches of the Medline, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases were carried out in May 2011. Search strategies combined various indexing terms for coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using an OR statement, and then combined those results with a term for the radial artery. The Medline search was limited to articles published since 2008.

Studies were included in the review if they assigned patients to catheterization groups randomly and reported any of the outcomes of interest, and included data from at least 25 patients per group. Studies were excluded if they selected for specific patient subgroups, as their results might not be representative of the whole. We did not exclude articles from consideration on the basis of language.

The literature searches yielded a total of 566 hits which was reduced to 43 after screening of titles and abstracts, and then reduced to 25 after elimination of duplicate records. All articles under consideration were successfully retrieved, and five met inclusion criteria. These were added to the 9 RCTs cited by Jolly to yield a total of 14 studies included in the meta-analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

PRISMA diagram of search results and article flow

We assessed the quality of each included trial using a nine-point scale based on scales from Jadad8 and Chalmers9 (see Supplemental Table 1). The overall quality of the evidence base for each outcome of interest was assessed using the GRADE system.10–12 Data from each trial was abstracted by an experienced research analyst and was not done in duplicate.

Meta-analyses were performed using Cochrane methods and RevMan version 5.1 software. For dichotomous outcome variables such as complication rates, summary odds ratios and confidence intervals were calculated. For continuous variables such as procedure time, we analyzed mean differences between radial and femoral groups. All analyses used fixed-effects models as the default, changing to random-effects if significant heterogeneity across studies was detected. Thresholds for use of random-effects methods were conservative: significant heterogeneity was defined as a Q statistic with a p-value less than 0.1 or an I2 statistic greater than 50%.

Predefined variables for subgroup analysis included year of publication (before or since 2008), quality rating (5 or greater), use of closure devices in femoral catheterization (all or some patients vs. no use), and trials involving only those undergoing PCI. We also tested the robustness of the conclusions by eliminating individual studies from the meta-analyses to determine if our conclusions were sensitive to an individual study.

Cost-benefit model

The stochastic simulation model was developed in TreeAge Pro 2009 (TreeAge Software Inc., Williamstown, MA) and Table 1 displays its inputs. Each patient entering the model had a risk of complications from their catheterization, depending on location (i.e., femoral or radial). The analysis was from the hospital perspective, and included the costs of catheterization lab and recovery room equipment and staffing (per minute), cost of a replacement catheter needed in the event access from the initial site failed, and the cost of added hospital stay, diagnosis, and treatment resulting from procedure complications. Input data for costs including those for catheterization procedure time (Cpt), hemostatis time in the recovery room (Ch), and cost of supplies needed for catheterization at the alternate site (Cas) were obtained from our local hospitals. These costs were in agreement with results of the FAME trial,4 a large-scale multicenter clinical trial of coronary artery catheterization and stenting. We found estimates for complication costs (Cmc, Ch, Cvc, and Cmb) in studies identified in our meta-analysis of procedure times and risks, and in a supplemental systematic Medline search limited to economic studies of coronary catheterization procedures published in English since 2007. These cost estimates include peri-procedure costs as well as costs of extended hospital stays, tests, and treatments associated with complications.

The systematic review yielded meta-estimates for Tpt and Tht: the differences in minutes for procedure time and hemostasis time respectively for radial catheterization versus femoral catheterization. It also provided summary risk ratios and confidence intervals comparing probability variables Pas: the access success rate at radial and femoral sites, and Pmc, Ph, Pvc, and Pmb: the risk of minor complications, hematoma, vascular complications and major bleeding, respectively. These risk ratios were applied as multipliers on the baseline probabilities of each type of femoral access complication to determine the corresponding probabilities of complications from radial access (Table 1).

Each simulation sent 1,000 patients through the model 1,000 times for a total of 1 million trials with unique outcomes to calculate the incremental cost per case. Monte Carlo probabilistic sensitivity analyses simultaneously varied the time and complication probability variables throughout the ranges listed in Table 1 (confidence intervals on the meta-analysis results were used as the range). In addition, one-way sensitivity analyses varied the cost of complications (Cmc, Ch, Cvc, and Cmb) and procedure costs (Cpt, Ch, and Cas) to determine the effect of each of these cost estimates on the incremental cost.

We used the mean cost across the studies as our baseline for each complication cost variable, and the maximum and minimum costs as the range for sensitivity analysis (Table 1). Since only one trial reported specific costs of hematomas,6 we multiplied and divided that cost by two to create a high and low range respectively for sensitivity analysis. For the procedure time cost and hemostasis time cost variables, we had to select arbitrary ranges for sensitivity analysis, ensuring we had at least a factor of two difference between baseline values and each extreme.

Results

Systematic review and meta-analysis

Nine RCTs were included in Jolly’s previous meta-analysis. Our systematic searches for additional trials (see PRISMA flow diagram, Figure 1) yielded five additional trials meeting the inclusion criteria for a total of fourteen. The trials are described in Table 2. Not all of the trials reported every outcome under consideration, and definitions of bleeding and other complications varied from trial to trial.

Table 2.

Table of studies

| Study | Quality (0–9) | Patients | Closure devices for femoral group | Major complication definition | Major bleeding definition | Other definitions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| † RIVAL 201113 | 7 | 2,361 diag 4,660 interv. |

*Some (26%) | Pseudoaneurysm requiring closure, AV fistula, “large” hematoma, or ischemia requiring surgery (major bleeding reported separately) | Death, transfusion of 2+ units, hypotension requiring inotropes, disability, hemoglobin decr. 5 g/dL, intracranial or intraocular bleed | |

| Hou 201014 | 4 | 100 interv. | None | Reported individually | Hemoglobin decrease ≥ 2 g/dL or transfusion | |

| Brueck 200915 | 5 | 654 diag. 370 interv. |

*Most (93%) | Transfusion, hemoglobin dec. 3 g/dL, pseudoaneurysm, hematoma, etc. | Hemoglobin decrease > 3 g/dL or transfusion | |

| Santas 200916 | 5 | 533 diag. 572 interv. |

None | Retroperitoneal bleed, transfusion, hemoglobin decrease 5 g/dL, vascular complication req. surgery |

Minor complications: pseudoaneurysm, ischemia, hematoma > 5 cm |

|

| Achenbach 200817 | 4 | 228 diag. 79 interv. |

None | Reported individually | Minor complications reported individually | |

| Lange 200618 | 2 | 195 diag. 102 interv. |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| † OUTCLAS 200519 | 5 | 644 interv. | None | Reported individually | Hemoglobin decrease > 3 g/dL or transfusion | |

| OCTOPLUS 200420 | 5 | 193 diag. 186 interv. |

*Some (7%) | Reported individually | Hemoglobin decrease ≥ 3 g/dL or transfusion | |

| Reddy 200421 | 4 | 75 diag. | Study variable | Reported individually | Transfusion | |

| CARAFE 200122 | 5 | 108 diag. 92 interv. |

Interventional patients only | Reported individually | Transfusion | |

| † Cooper 199923 | 5 | 200 diag. | None | Transfusion, pseudoaneurysm, ischemia | Transfusion | Hematoma defined as any measurable discoloration |

| Mann 199824 | 3 | 142 interv. | All | Reported individually | Transfusion | |

| BRAFE 199725 | 5 | ‡150 interv. | All | Reported individually | Not reported | |

| † ACCESS 199726 | 4 | 900 interv. | None | Reported individually | Hemoglobin decrease > 3 g/dL or transfusion |

–Closure devices used at physician’s discretion

–Authors report funding or sponsorship by device or drug manufacturer

–Female patients excluded

Quality of articles assessed using modified Jadad scale (see Supplemental Table 1) where scores can range from 0 (lowest quality) to 9 (highest quality)

Most trials, particularly the recent ones, combined patients undergoing purely diagnostic catheterization with those having PCI. Published results did not report outcomes separately in diagnostic and interventional procedures. Where femoral closure devices were included in study protocols, their use was usually at the discretion of the cardiologist performing the procedure, and outcomes were not separately reported for cases with and without the devices. The one exception was Reddy’s study21 where patients were randomized in three groups: radial catheterization, femoral catheterization with closure device, and femoral catheterization without closure device. However, results of that study were confounded by differences in the catheters used for the closure device and control patients.

Catheterization, procedure success, and cardiovascular events

Detailed results of our meta-analyses are presented in the online data supplement, while the results are summarized in Table 3. Meta-analysis of catheterization success rates (Supplemental figure 1A) found that patients randomized to radial catheterization were five times more likely to need conversion to the other access site than patients randomized to femoral catheterization (summary odds ratio [OR] 4.92, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.69–8.98). However, the higher failure rate for initial catheterization did not affect overall success rates for the diagnostic or interventional procedure (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.93–1.13, Supplemental figure 1B). Major adverse cardiovascular events also did not differ between radial and femoral catheterization groups (Supplemental figure 2).

Table 3.

Summary of meta-analysis results

| Outcome | N trials | N patients | Summary odds ratio [95% CI] | Favors | Significance | Effect of recent studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catheterization failure | 12 | 11,273 | 4.92 [2.69–8.98] | Femoral | p < 0.001 | No change |

| Procedure success | 11 | 10,579 | 0.97 [0.89–1.07] | No difference | NS | No change |

| MACE | 11 | 10,531 | 0.96 [0.77–1.21] | No difference | NS | No change |

| Major complications | 13 | 11,913 | 0.32 [0.24–0.42] | Radial | p < 0.001 | No change |

| Major bleeding | 12 | 10,908 | 0.39 [0.27–0.57] | Radial | p < 0.001 | No change |

| Hematoma | 10 | 9,661 | 0.36 [0.27–0.48] | Radial | p < 0.001 | No change |

| Minor complications | Insufficient data for meta-analysis | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Mean difference (min) [95% CI] | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Procedure time | 9 | 3,086 | 1.38 [−0.22–2.97] | Femoral | p = 0.09 | More uncertainty |

| Hemostasis time | 3 | 1,255 | 13.1 [2.3–23.9] | Radial | p = 0.02 | Smaller difference |

Complications

While definitions of “major complications” varied from study to study, and some included bleeding or hematoma in their figures for major complications, the meta-analyses showed remarkable consistency in the relative complication risks of radial and femoral catheterization (Supplemental figure 3). Complication rates were reduced 60 to 70 percent with radial catheterization compared to femoral catheterization, and the risk reduction had high statistical significance. We could not meta-analyze results for minor complication rates because one of the included studies16 reported only the percentage reduction and not the absolute number of minor complications in each group (it did report absolute numbers for the other types of complications). Therefore, to be conservative in our estimate of the safety benefits of radial catheterization, we chose the smallest summary effect size result from the other meta-analyses to use in the cost-benefit analysis for minor complications.

While significant heterogeneity was found in some of the variables meta-analyzed, the meta-analysis results were robust. None of our subgroup analyses, selecting more recent trials, higher-quality trials, trials involving only patients undergoing PCI, or trials where femoral closure devices were used, made any substantive changes in conclusions. In addition, none of the conclusions were dependent on a single trial.

Time-related variables

Many of the clinical trials reported mean times for completing the catheterization procedure as well as fluoroscopy time. Our meta-analysis (Supplemental figure 4) found a trend towards longer procedure times with the radial approach, but the statistical significance (p = 0.09) did not reach the standard threshold. However, the time difference was significant for fluoroscopy, supporting a hypothesis that the observed effect for procedure time is real and not a chance finding. Since the time results favor femoral catheterization, we presumed for the sake of our cost model that there was a real time cost for the radial approach.

Meta-analysis of hemostasis time data found a significant reduction in time with radial catheterization, though we are less certain of the magnitude of the effect due to heterogeneity of the study results.

Cost-benefit analysis

Using baseline figures for the costs of catheterization (Table 1), we estimated net hospital cost savings of $275 (95% CI: −$374 to −$183; negative values imply cost savings) per patient using radial catheterization instead of femoral catheterization. The large cost savings was driven primarily by complication costs as the procedure costs of radial catheterization were on average $1.52 (95% CI: $0.52 to $2.56) more than procedure costs of femoral catheterization.

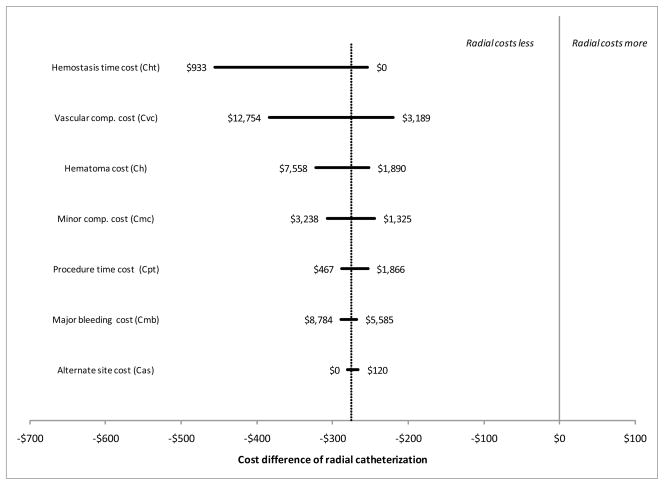

Figure 2 shows the results of our sensitivity analysis. None of the changes to the input variables tipped the balance of costs in favor of femoral catheterization (i.e., all 95% CIs were negative, implying cost savings for radial catheterization).

Figure 2. Sensitivity analysis.

Tornado diagram showing the effect of changes in each cost component variable on the net cost savings of radial catheterization as compared to femoral catheterization. Baseline values from our meta-analyses are indicated by the vertical dotted line. None of the changes to the component variables tip the balance of costs in favor of femoral catheterization.

Figure 3 shows the sensitivity of the net cost difference to changes in the time it takes to perform a radial catheterization. Our meta-analysis of clinical trials found that on average, the radial procedure takes 1.4 minutes longer than the femoral procedure (see dotted line in Figure 3). That difference would have to increase to approximately 20 minutes in order for the added cost of catheterization lab time to fully offset the other cost differences and make the overall cost of femoral catheterization less than the cost of radial catheterization.

Figure 3. Effect of radial access procedure time on cost savings.

Figure 3. Relationship of procedure time difference between radial and femoral catheterization and cost savings with radial catheterization. The dotted line represents the actual difference in procedure time as determined by the meta-analysis. If radial and femoral procedures take the same time, the model concludes that radial catheterization will be $297 less costly. The cost advantage of radial catheterization disappears only if it takes approximately 20 minutes longer than femoral catheterization.

Similarly, Figure 4 shows the effect of reducing complication rates in femoral catheterization on the net cost results. The left end of the graph represents our baseline rates for each of the four complication types modeled. Moving to the right on the x axis simultaneously reduces all four rates by the same proportion, with no change to the complication rates of radial catheterization. In order to overturn the finding that radial catheterization is less costly, the rates of all those complications of femoral catheterization would have to be reduced by approximately 60%.

Figure 4. Effect of reducing femoral access complication rate on cost-savings of the radial access strategy.

Figure 4. Using baseline risks of femoral and radial catheterization from the meta-analyses, radial catheterization saves $275 per patient. Risks of femoral catheterization must be reduced by approximately 60% with no corresponding change to radial risk in order for the net costs to be equal.

Discussion

Our cost-benefit analysis suggests that radial catheterization lowers hospital costs at the same time that it reduces adverse effects to patients. In addition, none of the changes to cost variables brought the net cost savings to a point which would favor femoral catheterization. Widespread adoption of radial catheterization could have substantial savings for the US health care system given that over a million coronary catheterizations are performed in the US annually.27, 28

Since the first cases were reported in the late 1980’s,29 radial artery access for diagnostic coronary angiography and PCI has gained momentum in many hospitals in Europe and Asia.2 Advocates of the radial approach argue that it reduces vascular complications and rates of major bleeding, which has been demonstrated clearly in a recently published large randomized clinical trial: RIVAL.13 In addition, without the need for lengthy post-procedural bedrest, earlier ambulation and therefore discharge are possible, potentially reducing hospital costs and improving patient satisfaction.30 They also report greater patient satisfaction with radial catheterization than with femoral.13, 26

In the United States, however, radial artery cases account for less than 10% of the diagnostic cases and approximately 1% of PCI cases.1 In addition, the radial approach is used less commonly in elderly patients, women and patients with acute coronary syndromes.1 This discrepancy appears to stem from concerns about increases in procedure time, radiation exposure, and access failure in patients undergoing radial artery catheterization offsetting the benefits of decreased vascular complications. We estimate that the procedure time would need to increase by 20 minutes per case to make a femoral artery access strategy less costly than radial access, while our meta-analysis found a difference of only 1 minute and 23 seconds between them. There was a small but statistically significant increase in fluoroscopy time associated with radial access, but the increase was less than 1 minute.

Due to the steeper learning curve for gaining proficiency with the radial approach, we recognize that the benefits we demonstrate may not be observed early as practitioners develop facility with radial arterial access. One trial has shown that procedural time for the radial approach was longer than for the femoral approach at an interim analysis, but that at the end of the learning curve, there were no significant differences in procedure time.26 Performing enough procedures to attain proficiency may pose a practical challenge for many cardiologists in the United States who have been trained to use the femoral artery approach, but do not have the opportunity to learn radial arterial access. Nevertheless, our systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that it would be to the benefit of patients for cardiologists to obtain training so they can use the radial approach over the long term.

Our study demonstrated that the savings from reduced vascular complications outweighed the increased costs of longer procedure times and access failure associated with radial artery access by a large margin. Although procedure outcomes as measured by major adverse cardiovascular events were equivalent between the two groups, radial artery access was associated with significantly reduced vascular access site complications and bleeding. Despite using procedure times and cost estimates unfavorable to radial artery access, a radial artery strategy was still superior due to the high cost of vascular complications associated with femoral access. Even if the difference in hemostasis time were equivalent between the techniques (such as if a femoral artery closure device were used on every case), the reduction in vascular complications would still make radial access less costly.

The pooled vascular event rate in the patients undergoing femoral access was 3.3% versus 1.0% for radial access. This estimation is somewhat higher than the major femoral vascular event rate of 2.1 to 2.8% published in a large clinical registry.31 In our study, a more than 60% reduction in all complications of femoral catheterization, with no corresponding reduction in complications of radial catheterization, would be needed to bring the net cost of femoral catheterization to that of radial catheterization. Recent retrospective studies have demonstrated a very low femoral vascular complication rate with the use of an arterial closure device,32 however no randomized studies have shown that femoral artery catheterization, with or without a vascular closure device, lower rates of vascular complications compared to radial access. If there were no differences at all between the vascular access site complications of radial versus femoral access, the increased cost for the radial artery strategy would only be $1.18 per patient, primarily due to the cost of access site failure. On the other hand, even if the absolute reduction in the rate of hematomas, major bleeding, and major vascular complications from radial access was only 0.1% for total events, there would still be a $18.07 per case cost savings from the radial artery access strategy. Therefore, even a slight reduction of vascular complications would result in a cost savings from using a radial artery access strategy.

Perspective

It needs to be emphasized that our cost study is analyzed from the hospital perspective, as costs were calculated based on reports of actual hospital expenditures to cover catheterization lab time, hospitalization, blood transfusions, and treatment of vascular complications. In particular, we considered major bleeding and vascular complications separately, therefore treating the costs as additive. While the extra cost to the hospital of a blood transfusion is independent of the cost for prolonged hospitalization, imaging studies, and vascular repair, from the payer’s perspective a blood transfusion would likely be subsumed under a diagnosis related group for a patient who undergoes a vascular repair. Since the cost of complications was the primary driver of increased costs of the femoral artery approach, the cost savings of a radial artery strategy to the payer and to society may not be as evident. Importantly, we did not consider the comfort or preference of patients and physicians, which could arguably be the primary reason a particular vascular access site is chosen.

Limitations

An important objection to the published literature comparing these access strategies is that many studies evaluate outcomes among operators who are already highly proficient with the procedure. The radial technique has a steeper learning curve than femoral artery access.33 Failed access and radial artery complications are high early on, and decrease as operators became more skilled at the procedure.13 Furthermore, the patients enrolled in clinical trials comparing these strategies must be suitable candidates for either procedure, which might exclude high risk patients with complicated access issues. Therefore our estimates of complication rates, procedure and recovery times may be vulnerable to a publication bias that favors the radial access strategy. While one early trial25 excluded female patients because of their smaller arteries, subsequent trials have included a broad range of patients.

Another limitation is the estimation of costs assigned to clinically-significant hematomas, which may necessitate vascular imaging, surgical consultation, possible intervention, and longer hospitalizations. It is unclear whether small or moderate sized hematomas that would not necessarily lead to these costly measures were counted in the clinical trials. But our conclusions are not solely dependent on the cost impact of hematomas. They contribute just $40 to $56 to the $275 per-case savings of radial versus femoral catheterization.

There are complications of radial access that did not factor into our analysis. Radial artery occlusions occur in approximately 5% of radial cases,34 but it is difficult to attribute a cost to this complication since there may be no immediate consequences. A radial occlusion, however, can limit vascular access and conduits for surgical bypasses, which could significantly affect the kinds of therapies available to patients in the future.

Finally there was significant heterogeneity of study results in some of the meta-analyses used to estimate procedure times and success rates for our cost-benefit analysis (see Supplemental figure 1 and Supplemental figure 4). To test whether or not heterogeneity could be driving our conclusions, we excluded the studies most favorable to radial catheterization in analyses with significant heterogeneity (p < 0.10 or I2 ≥ 50%) and repeated those analyses. The resulting changes to the meta-analytic results were small and did not change our conclusions. For example, excluding the Reddy and Santas trials from the meta-analysis of procedure time (Supplemental figure 4A) reduced I2 from 80% to 6%, but raised the summary time difference only from 1.38 minutes to 2.30. That change would reduce the net savings of radial catheterization from $275 to $251. Heterogeneity was not significant in the complication rate differences, which make the largest contribution to cost savings.

Conclusion

A strategy of routine radial artery access for coronary angiography is associated with an overall reduction in hospital costs and vascular complications if operators have the proficiency with radial artery access to approximate the outcomes of clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

What is Known

In the US, radial artery catheterization is performed in the minority of diagnostic angiograms and rarely in percutaneous coronary interventions.

Radial artery catheterization can reduce hemostasis time and vascular complications, but can take longer to perform and may require conversion to the femoral site.

What this Article Adds

Cost savings from reducing complications appear to outweigh additional direct procedure costs of radial catheterization.

On average, the radial approach saved $275 in direct hospital costs per patient as compared to the femoral approach.

None of the changes to cost variables brought the net cost savings to a point which would favor femoral catheterization.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

Funded under NIH/National Center for Research Resources grant RR025015

Dr. Don is supported by grant RR025015 from the National Center for Research Resources. The funding body had no role in the design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures

A preliminary version of this work was presented in poster form at the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research in Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke Scientific Sessions, Washington, May 2011

References

- 1.Rao SV, Ou FS, Wang TY, Roe MT, Brindis R, Rumsfeld JS, Peterson ED. Trends in the prevalence and outcomes of radial and femoral approaches to percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertrand OF, Rao SV, Pancholy S, Jolly SS, Rodes-Cabau J, Larose E, Costerousse O, Harmon M, Mann T. Transradial approach for coronary angiography and interventions: results of the first international transradial practice survey. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:1022–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jolly SS, Amlani S, Hamon M, Yusuf S, Mehta SR. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography or intervention and the impact on major bleeding and ischemic events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2009;157:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fearon WF, Bornschein B, Tonino PA, Gothe RM, Bruyne BD, Pijls NH, Siebert U Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation (FAME) Study Investigators. Economic evaluation of fractional flow reserve-guided percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with multivessel disease. Circulation. 2010;122:2545–2450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.925396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinto DS, Stone GW, Shi C, Dunn ES, Reynolds MR, York M, Walczak J, Berezin RH, Mehran R, McLaurin BT, Cox DA, Ohman EM, Lincoff AM, Cohen DJ ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) Investigators. Economic evaluation of bivalirudin with or without glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition versus heparin with routine glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition for early invasive management of acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1758–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao SV, Kaul PR, Liao L, Armstrong PW, Ohman EM, Granger CB, Califf RM, Harrington RA, Eisenstein EL, Mark DB. Association between bleeding, blood transfusion, and costs among patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2008;155:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kugelmass AD, Cohen DJ, Brown PP, Simon AW, Becker ER, Culler SD. Hospital resources consumed in treating complications associated with percutaneous coronary interventions. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalmers TC, Smith H, Jr, Blackburn B. A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials. 1981;2:31–49. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(81)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Vist GE, Liberati A, Schunemann HJ. GRADE: Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:1049–1051. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39493.646875.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ. GRADE: What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995–998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jolly SS, Yusuf S, Cairns J, Niemela K, Xavier D, Widimsky P, Budaj A, Niemela M, Valentin V, Lewis BS, Avezum A, Steg PG, Rao SV, Gao P, Afzal R, Joyner CD, Chrolavicius S, Mehta SR. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography and intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes (RIVAL): a randomised, parallel group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1409–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou L, Wei YD, Li WM, Xu YW. Comparative study on transradial versus transfemoral approach for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in Chinese patients with acute myocardial infarction. Saudi Med J. 2010;31:158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brueck M, Bandorski D, Kramer W, Wieczorek M, Höltgen R, Tillmanns H. A randomized comparison of transradial versus transfemoral approach for coronary angiography and angioplasty. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santas E, Bodí V, Sanchis J, Núñez J, Mainar L, Miñana G, Chorro FJ, Llácer A. The left radial approach in daily practice. a randomized study comparing femoral and right and left radial approaches. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62:482–490. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)71830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Achenbach S, Ropers D, Kallert L, Turan N, Krähner R, Wolf T, Garlichs C, Flachskampf F, Daniel WG, Ludwig J. Transradial versus transfemoral approach for coronary angiography and intervention in patients above 75 years of age. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72:629–635. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange HW, von Boetticher H. Randomized comparison of operator radiation exposure during coronary angiography and intervention by radial or femoral approach. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;67:12–16. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slagboom T, Kiemeneij F, Laarman GJ, van der Wieken R. Outpatient coronary angioplasty: Feasible and safe. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;64:421–427. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louvard Y, Benamer H, Garot P, Hildick-Smith D, Loubeyre C, Rigattieri S, Monchi M, Lefèvre T, Hamon M OCTOPLUS Study Group. Comparison of transradial and transfemoral approaches for coronary angiography and angioplasty in octogenarians (the OCTOPLUS study) Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1177–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy BK, Brewster PS, Walsh T, Burket MW, Thomas WJ, Cooper CJ. Randomized comparison of rapid ambulation using radial, 4 French femoral access, or femoral access with AngioSeal closure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;62:143–149. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louvard Y, Lefèvre T, Allain A, Morice M. Coronary angiography through the radial or the femoral approach: the CARAFE study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2001;52:181–187. doi: 10.1002/1522-726x(200102)52:2<181::aid-ccd1044>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper CJ, El-Shiekh RA, Cohen DJ, Blaesing L, Burket MW, Basu A, Moore JA. Effect of transradial access on quality of life and cost of cardiac catheterization: a randomized comparison. Am Heart J. 1999;138:430–436. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mann T, Cubeddu G, Bowen J, Schneider JE, Arrowood M, Newman WN, Zellinger MJ, Rose GC. Stenting in acute coronary syndromes: A comparison of radial versus femoral access sites. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:572–576. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benit E, Missault L, Eeman T, Carlier M, Muyldermans L, Materne P, Lafontaine P, De Keyser J, Decoster O, Pourbaix S, Castadot M, Boland J. Brachial, radial, or femoral approach for elective Palmaz-Schatz stent implantation: a randomized comparison. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1997;41:124–130. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0304(199706)41:2<124::aid-ccd3>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiemeneij F, Laarman GJ, Odekerken D, Slagboom T, van der Wieken R. A randomized comparison of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty by the radial, brachial and femoral approaches: the ACCESS study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1269–1275. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riley RF, Don CW, Powell W, Maynard C, Dean LS. Trends in coronary revascularization in the United States from 2001 to 2009: Recent declines in percutaneous coronary intervention volumes. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:193–197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.958744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas FL, Siewers AE, Malenka DJ, Wennberg DE. Diagnostic-therapeutic cascade revisited: Coronary angiography, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and percutaneous coronary intervention in the modern era. Circulation. 2008;118:2797–2802. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.789446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campeau L. Percutaneous radial artery approach for coronary angiography. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1989;16:3–7. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810160103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mann JT, Cubeddu MG, Schneider JE, Arrowood M. Right radial access for PTCA: a prospective study demonstrates reduced complications and hospital charges. J Invasive Cardiol. 1996;8:40D–44D. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marso SP, Amin AP, House JA, Kennedy KF, Spertus JA, Rao SV, Cohen DJ, Messenger JC, Rumsfeld JS National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Association between use of bleeding avoidance strategies and risk of periprocedural bleeding among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2010;303:2156–2164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smilowitz NR, Kirtane AJ, Guiry M, Gray WA, Dolcimascolo P, Querijero M, Echeverry C, Kalcheva N, Flores B, Singh VP, Rabbani L, Kodali S, Collins MB, Leon MB, Moses JW, Weisz G. Practices and complications of vascular closure devices and manual compression in patients undergoing elective transfemoral coronary procedures. Am J Cardiol. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.02.065. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agostoni P, Biondi-Zoccai GG, de Benedictis ML, Rigattieri S, Turri M, Anselmi M, Vassanelli C, Zardini P, Louvard Y, Hamon M. Radial versus femoral approach for percutaneous coronary diagnostic and interventional procedures; systematic overview and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stella PR, Kiemeneij F, Laarman GJ, Odekerken D, Slagboom T, van der Wieken R. Incidence and outcome of radial artery occlusion following transradial artery coronary angioplasty. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1997;40:156–158. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0304(199702)40:2<156::aid-ccd7>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.