Background: Cysteine biosynthesis is the exclusive entry point for reduced sulfur in cellular metabolism.

Results: The mitochondrial cysteine synthase complex (mCSC) regulates serine acetyltransferase activity in response to cysteine availability.

Conclusion: The mCSC is a sensor of sulfur availability and regulates cysteine synthesis.

Significance: The integration of cysteine in the regulatory model of the CSC establishes a new sensory function for the mCSC.

Keywords: Amino Acid Transport, Plant Biochemistry, Plant Physiology, Protein-Protein Interactions, Serine, Cysteine, Cysteine Synthase Complex, O-Acetylserine, Serine Acetyltransferase

Abstract

Cysteine synthesis is catalyzed by serine acetyltransferase (SAT) and O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase (OAS-TL) in the cytosol, plastids, and mitochondria of plants. Biochemical analyses of recombinant plant SAT and OAS-TL indicate that the reversible association of the proteins in the cysteine synthase complex (CSC) controls cellular sulfur homeostasis. However, the relevance of CSC formation in each compartment for flux control of cysteine synthesis remains controversial. Here, we demonstrate the interaction between mitochondrial SAT3 and OAS-TL C in planta by FRET and establish the role of the mitochondrial CSC in the regulation of cysteine synthesis. NMR spectroscopy of isolated mitochondria from WT, serat2;2, and oastl-C plants showed the SAT-dependent export of OAS. The presence of cysteine resulted in reduced OAS export in mitochondria of oastl-C mutants but not in WT mitochondria. This is in agreement with the stronger in vitro feedback inhibition of free SAT by cysteine compared with CSC-bound SAT and explains the high OAS export rate of WT mitochondria in the presence of cysteine. The predominant role of mitochondrial OAS synthesis was validated in planta by feeding [3H]serine to the WT and loss-of-function mutants for OAS-TLs in the cytosol, plastids, and mitochondria. On the basis of these results, we propose a new model in which the mitochondrial CSC acts as a sensor that regulates the level of SAT activity in response to sulfur supply and cysteine demand.

Introduction

Cysteine biosynthesis is catalyzed by a two-step process in plants. In the first step, serine acetyltransferase (SAT4; EC 2.3.1.30) transfers an acetyl moiety from acetyl coenzyme A to serine and forms O-acetylserine (OAS). Subsequently, OAS (thiol) lyase (OAS-TL; EC 2.5.1.47) replaces the acetyl group of OAS with sulfide and releases cysteine (1). Reverse genetic approaches and biochemical studies of Arabidopsis OAS-TL isoforms demonstrated that cysteine biosynthesis in plants is limited by OAS supply (2–4). The transcript abundance, protein level, and extractable activity of SAT and OAS-TLs are not significantly altered by sulfur limitation or genetic manipulation of the sulfur assimilation pathway. However, exposure to toxic compounds or harsh stress treatments can induce significant transcription of particular SAT and OAS-TL isoforms in Arabidopsis (5, 6). This led to a model based on kinetic studies of free SATs in which SAT activity is regulated mainly at the metabolic level by the cysteine feedback inhibition of SATs (7). Subsequently, a regulatory model for SAT activity based on the reversible interaction of SAT and OAS-TL in the hetero-oligomeric cysteine synthase complex (CSC) was proposed (reviewed in Refs. 8 and 9). In this model, SAT present in the CSC is activated, whereas OAS-TL is catalytically inactive and acts as a regulatory subunit for the SAT (9). As a result of OAS-TL inactivation, OAS leaves the CSC and is converted to cysteine by a large excess of free OAS-TL dimers. Upon sulfur limitation, sulfide availability limits cysteine biosynthesis, which results in an accumulation of OAS. Sulfide stabilizes the CSC, but in its absence, the increase in OAS causes the CSC to dissociate (8). The impact of OAS and sulfide on CSC formation in turn defines this complex as a sensor of sulfur availability that adjusts the SAT activity to the actual sulfur status of the cell.

The CSC is present in the cytosol, plastids, and mitochondria of plant cells, but the activities and amount of SAT and OAS-TL differ significantly between these subcellular compartments (10–12). In Arabidopsis leaves, ∼90% of OAS-TL activity is provided by OAS-TL A in the cytosol and OAS-TL B in chloroplasts. The remaining activity comes from mitochondrial OAS-TL C (10, 12). In contrast, ∼80% of total SAT activity is found to originate from the mitochondrial isoform SAT3 (serat2;2) (11, 13). The residual SAT activity is contributed by plastid-localized SAT1 (serat2;1) and three cytosolic SATs, of which SAT5 (serat1;1) is the most abundant. T-DNA insertion mutants for each of the SAT genes are viable, demonstrating that individually OAS synthesis in the cytosol, plastid, or mitochondria is not essential (11, 13). Knockdown of mitochondrial SAT3 causes significant growth retardation, suggesting a major role for the mitochondria in supplying OAS for cysteine synthesis (2). A prominent role of the mitochondrial CSC (mCSC) in regulation of SAT3 activity and thereby cellular cysteine is also indicated by the growth retardation phenotype of oastl-C, whereas oastl-A and oastl-B mutants are unaffected (12). However, in vitro CSC formation has only minor impact on SAT3 affinities for serine and acetyl coenzyme A, but CSC-bound SAT3 is less sensitive to feedback inhibition by cysteine compared with free SAT3 (14). The question arises of how the constitutively expressed and most abundant SAT of Arabidopsis is regulated in vivo. Here, we used FRET of CSC subunits in mitochondria of plants, NMR spectroscopy of isolated mitochondria, and [3H]serine labeling to unequivocally demonstrate the significance of mitochondria for cellular cysteine synthesis and to merge the two existing concepts for the metabolic regulation of SAT3 in an advanced model of CSC function.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of Vectors

PCR and cloning of DNA fragments were performed as described (15). SAT3 and OAS-TL C cDNAs were fused with restriction and attb sites for cloning by PCR amplification using the primers shown in supplemental Fig. 1. The SAT3 cDNA was cloned into pB7WGY2 for fusion with enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) using GatewayTM technology. Then eYFP-SAT3 cDNA was re-amplified by PCR and introduced in the vector pBinAr-SHMT by conventional cloning of a BamHI/SalI restriction fragment. The resulting construct (pBinAr-SHMT/YFP-SAT3) codes for eYFP fused to the N terminus of SAT, which is targeted to mitochondria by the transit peptide of serine hydroxymethyltransferase. The full-length OAS-TL cDNA sequence, including the endogenous mitochondrial transit peptide, was cloned in pB7CWG2 using GatewayTM technology. pB7CWG2-OAS-TL C codes for full-length OAS-TL C fused to the N terminus of enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (eCFP). Expression of OAS-TL C-eCFP and eYFP-SAT in Escherichia coli and purification of recombinant proteins were performed as described (15). The respective cDNAs were PCR-amplified and cloned in the pETM20 vector as described in the legend to supplemental Fig. 2. The identity of all constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing and restriction analysis (supplemental Figs. 1 and 2).

Transient Expression in Leaves

Binary vectors for expression of eYFP in fusion with SAT (eYFP-SAT) and OAS-TL C fused with eCFP (OAS-TL C-eCFP) were transformed in Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1 and selected with the appropriate antibiotic for presence of the binary and auxiliary vectors. Leaves of 4-week-old soil-grown Nicotiana tabacum plants were infiltrated as described (16) with a 1:1 mixture of A. tumefaciens strain C58C1 harboring the respective binary vectors (A600 nm = 0.5) suspended in LB medium.

FRET

Three days after infiltration, 1-cm2 leaf discs were analyzed for FRET between eYFP-SAT and OAS-TL C-eCFP using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Axiovert 200M connected to an LSM 510 Meta confocal module, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) at 512 × 512 pixel resolution. The integrity of the plasma membrane was tested by propidium iodide (0.05 mm) staining. Localization of eYFP-SAT and OAS-TL C-eCFP in mitochondria of N. tabacum cells was assessed by co-staining with 0.01 mm MitoTracker OrangeTM (Molecular Probes). FRET emission signals were detected at 485 ± 15 nm upon excitation at 405 nm. FRET efficiency was calculated after photo acceptor bleaching of OAS-TL C-eCFP protein with maximum laser intensity at 514 nm as described (17). Recombinant OAS-TL C-eCFP (0.5 μm) and eYFP-SAT (0.5 μm) were tested for positive FRET with the confocal laser scanning microscope using the same settings.

Isolation of Mitochondria

Mitochondria were isolated at 4 °C from 20–30 g (fresh weight) of 14-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings using a procedure that was based largely on published protocols (18, 19). Seedlings were ground using a mortar and pestle in a total of 600 ml of grinding medium (0.25 m sucrose, 15 mm MOPS, 0.4% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, 0.6% (w/v) polyvinylpyrolidone-40, 1.5 mm EDTA, 100 mm ascorbate, and 10 mm dithiothreitol, pH 7.4). The filtered cell extract was separated by differential centrifugation, and the mitochondria were purified on a 0–4.4% PVP/Percoll gradient. The isolated mitochondria were washed twice with 0.3 m sucrose and 10 mm TES, pH 7.5, and then resuspended in the same buffer. All buffers were supplemented with cysteine (0.5 or 1 mm) for experiments in which mitochondria were used to examine the effect of cysteine on serine metabolism.

NMR Analysis of [3-13C]Serine Metabolism

The metabolism of labeled serine was monitored continuously under conditions of state 3 respiration using procedures similar to those described before (20, 21). Coupled mitochondria from WT, serat2;2, and oastl-C seedlings (typically 1–2 mg of mitochondrial protein in 1 ml of wash buffer) were diluted in 4 ml of buffer containing 0.2 m mannitol, 0.1 m MOPS, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.1% (w/v) BSA, 20 mm KH2PO4, 20 mm glucose, 10 mm pyruvate, 2.1 mm citrate, 1.3 mm succinate, 0.6 mm malate, 0.3 mm NAD+, 0.1 mm ADP, 0.1 mm TPP, 0.02 mm fumarate, 0.02 mm isocitrate, 0.15 units/ml hexokinase, and 10 mm [3-13C]serine (99%; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.) in 10% D2O, pH 7.2. The mitochondrial suspension was oxygenated and stirred continuously in a 10-mm diameter NMR tube using an airlift system (22), and proton-decoupled 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 150.9 MHz on a Varian Unity Inova 600 spectrometer using a broadband probe. Twenty spectra were recorded in 15-min blocks over a period of 5 h using a 90° pulse angle, a 1.016-s acquisition time, and a 6-s relaxation delay. Low power frequency-modulated decoupling was applied during the relaxation delay to maintain the nuclear Overhauser effect, and this was switched to higher power Waltz decoupling during the acquisition time to remove the proton couplings. Chemical shifts are cited relative to the mannitol signal at 63.90 ppm, and the signal intensities of 13C-labeled OAS, N-acetyl[3-13C]serine (NAS), and serine were measured relative to the intensity of this peak. The protein content, respiratory coupling ratio, and outer membrane integrity of the mitochondria were measured for every replicate, and the amounts of OAS and NAS were expressed as relative peak area/mg of protein.

In Vivo Analysis of Serine Fluxes

Incorporation of [3H]serine into OAS in leaves of 7-week-old WT and oastl knock-out mutants was performed as described (12). The feeding solution (0.5 × Murashige and Skoog medium) contained 2.5 μm [2,3-3H]serine (specific activity, 20 Ci/mmol; Hartmann Analytic GmbH).

Statistical Analysis

Means from different data sets was analyzed for statistical significance with the unpaired t test. Constant variance and normal distribution of data were checked with SigmaStat 3.0 prior to statistical analysis. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to analyze samples that did not follow normal Gaussian distribution.

RESULTS

Formation of the mCSC in Vivo

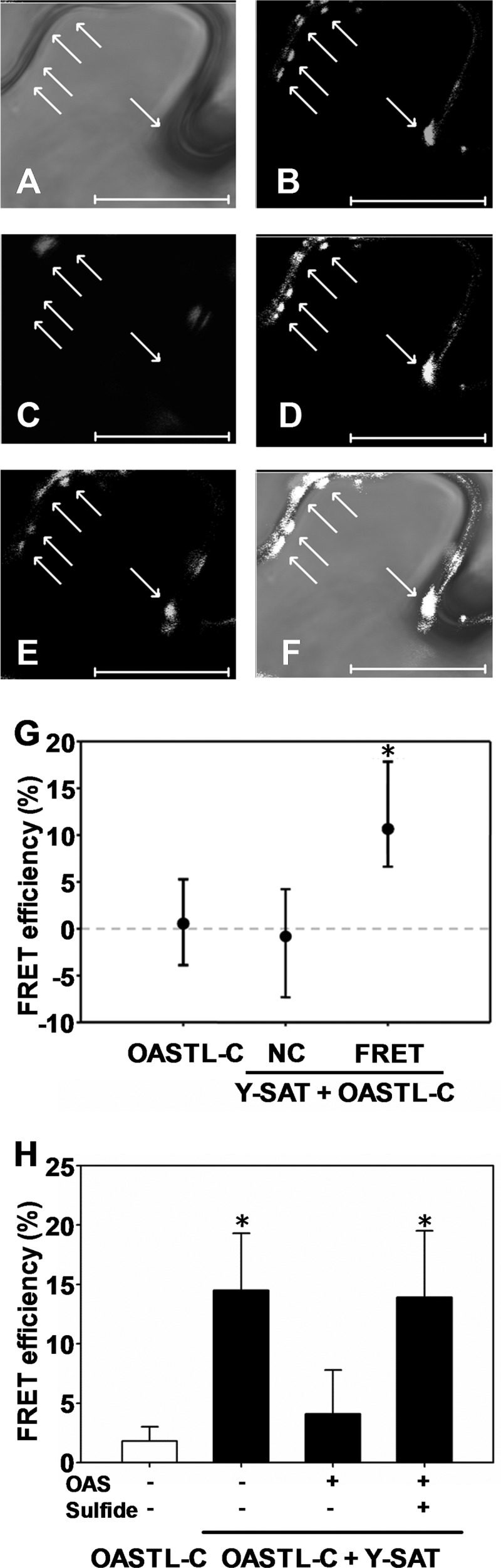

The interaction of purified SAT3 and OAS-TL C has been demonstrated to occur spontaneously in vitro (14, 23) in the absence of OAS. Mitochondria are the main site of OAS production, so evidence was sought for the formation of the mCSC in vivo. To this end, SAT3 and OAS-TL C were fused with eYFP (eYFP-SAT) and eCFP (OAS-TL C-eCFP), respectively. eYFP-SAT and OAS-TL C-eCFP were transiently expressed in epidermal cells of N. tabacum, and the localization of both eYFP-SAT and OAS-TL C-eCFP to the mitochondria was verified by co-staining with MitoTracker Orange (Fig. 1, A–E). The interaction of eYFP-SAT and OAS-TL C-eCFP was assessed in vivo by quantification of FRET between the donor eYFP and acceptor eCFP using the photo acceptor bleaching technique. FRET efficiency in bleached areas of tobacco cells expressing eYFP-SAT and OAS-TL C-eCFP was significantly higher than the control efficiency in non-bleached areas. As a control for the impact of acceptor bleaching on the donor, the FRET efficiency in bleached areas of tobacco cells expressing only OAS-TL C-eCFP was determined and found to be negligible (Fig. 1G), confirming the validity of the FRET signal between eYFP-SAT and OAS-TL C-eCFP. Note that eYFP was fused to the N terminus of SAT because the C terminus of SAT is responsible for the interaction with OAS-TL. Fusion of YFP to the C terminus of SAT abolished the FRET signal between SAT-eYFP and OAS-TL C-eCFP (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Quantification of CSC formation in tobacco mitochondria by FRET. A, light microscopy of N. tabacum epidermal cells transiently expressing OAS-TL C-eCFP and eYFP-SAT. B, staining of mitochondria with MitoTracker Orange. C, autofluorescence of plastids in N. tabacum cells. D, YFP fluorescence. E, CFP fluorescence. F, overlay of A–E. Arrows indicate mitochondria. Scale bars = 20 μm. G, FRET efficiency for protein-protein interaction of OAS-TL C-eCFP (OASTL-C) and eYFP-SAT (Y-SAT) as determined by photo acceptor bleaching of YFP in mitochondria of transiently transformed N. tabacum epidermal cells. As a negative control (NC), the FRET efficiency was also determined in a non-bleached area of the same cell. FRET efficiency was also quantified in N. tabacum cells expressing only OAS-TL C-eCFP as an independent negative control. Data represent the median for efficiency of FRET (n = 69), the negative control (n = 157), and the OAS-TL C-eCFP control (n = 57). The upper and lower error bars indicate the 75 and 25% percentile of the data set, respectively. H, the FRET efficiency of purified recombinant OAS-TL C-eCFP and eYFP-SAT was tested in the absence (−) and presence (+) of 1 mm sulfide and 25 mm OAS, respectively. The FRET efficiency of OAS-TL C-eCFP in the absence of eYFP-SAT served as a negative control. *, p < 0.01 (statistically significant differences between samples as determined by the Mann-Whitney rank test).

Characterization of the mCSC in Vitro

To characterize the interaction of recombinant OAS-TL C-eCFP and eYFP-SAT with respect to the effectors sulfide and OAS, eYFP-SAT and OAS-TL C-eCFP were expressed in E. coli, and the purified proteins were tested for FRET efficiency. eYFP-SAT and OAS-TL C-eCFP spontaneously formed the CSC in the absence of both effectors, which is in agreement with previous studies of untagged recombinant SAT and OAS-TL (15, 23). Application of OAS resulted in a significant lower FRET efficiency, demonstrating that OAS can dissociate the recombinant CSC formed by eYFP-SAT and OAS-TL C-eCFP. Preincubation of the CSC with sulfide prevented dissociation by OAS (Fig. 1H). These results strongly indicate that eYFP-SAT interacts with OAS-TL C-eCFP via its C-terminal tail, as shown for native SAT and OAS-TLs, and explain why fusion of YFP to the C terminus of SAT abolished the FRET signal.

Mitochondrial Synthesis and Export of OAS

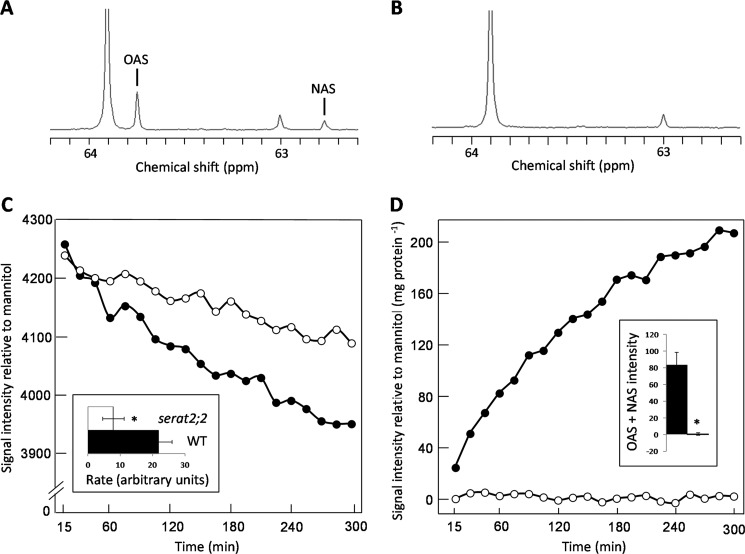

The metabolism of [3-13C]serine by isolated mitochondria was followed in situ by recording 13C NMR spectra from a dilute suspension of mitochondria maintained in state 3 respiration. Control experiments have shown that the NMR signals originate entirely from the suspending medium in these experiments, reflecting the very small fraction of the sample volume occupied by the mitochondria (24). Incubating WT mitochondria with [3-13C]serine led to the detection of signals that could be assigned to O-acetyl[3-13C]serine and NAS (Fig. 2A), as confirmed by comparison with spectra of authentic standards (data not shown). NAS originates from OAS by a known spontaneous intramolecular shift of the acetyl moiety from the hydroxyl to the amino group (25). Labeled OAS and NAS were undetectable in the spectra recorded from suspensions of serat2;2 mitochondria (Fig. 2B), and time courses showed faster metabolism of serine by WT mitochondria (Fig. 2C) and negligible production of OAS by the mutant (Fig. 2D). Glucose phosphorylation was observed in all experiments, confirming state 3 respiration of the mitochondria and demonstrating that the absence of OAS accumulation in the serat2;2 experiments was not due to a failure of mitochondrial respiration (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Metabolism of [3-13C]serine by isolated Arabidopsis mitochondria. Shown are 13C NMR spectra of WT (A) and serat2;2 (B) mitochondria recorded after a 5-h incubation with [3-13]serine. Labeled OAS was detectable only in the WT mitochondrial suspension, and a small proportion of the signal is present as NAS. The peaks at 63.9 and 63.0 ppm are natural abundance signals from mannitol and sucrose, respectively. Shown are averaged time courses for the [3-13C]serine signal at 60.9 ppm (n = 3) (C) and the total acetyl[3-13C]serine (OAS + NAS) signal (n = 3) (D). Error bars were omitted because the shape of the time courses differed between replicates. ●, WT; ○ serat2;2. The inset in C shows that the WT mitochondria metabolized serine faster than the serat2;2 mitochondria over the first 2.5 h of the time course (expressed as the change in signal intensity relative to the mannitol signal per 15 min/mg if protein). *, p = 0.010. The inset in D shows that the production of total acetyl[3-13C]serine (OAS + NAS) over the first 2.5 h of the time course (expressed as signal intensity relative to the mannitol signal per mg of protein) was negligible in the serat2;2 mitochondria compared with the WT mitochondria. *, p = 0.011.

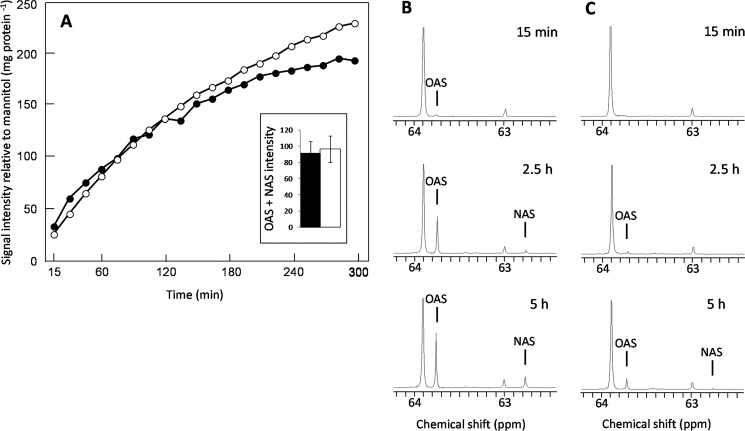

SAT Is under the Feedback Control of Cysteine

The metabolism of [3-13C]serine was compared in suspensions of WT and oastl-C mitochondria in the presence and absence of cysteine to test the functional significance of the interaction between SAT and OAS-TL. There was no difference in the production of labeled acetylserine (OAS + NAS) in the absence of cysteine between WT and oastl-C mitochondria (Fig. 3A), but the addition of 0.5 mm cysteine to the medium greatly reduced the accumulation of OAS and NAS in the oastl-C mitochondria (Fig. 3, B and C, and supplemental Fig. 3), showing that the interaction between SAT and OAS-TL in the CSC prevented feedback inhibition of SAT by cysteine.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of cysteine on metabolism of [3-13C]serine by isolated Arabidopsis mitochondria. A, averaged time course for the total acetyl[3-13C]serine 13C NMR signal observed during the metabolism of [3-13C]serine by WT (●) and oastl-C (○) mitochondria (n = 3). The inset shows that there was no difference (p = 0.72) between the WT and oastl-C mitochondria in the total acetyl[3-13C]serine (OAS + NAS) signal observed over the first 2.5 h of the time course (expressed as signal intensity relative to the mannitol signal per mg of protein). Shown are the 13C NMR spectra of WT (B) and oastl-C (C) mitochondria recorded after 15 min, 2.5 h, and 5 h of incubation with [3-13]serine in medium containing 0.5 mm cysteine.

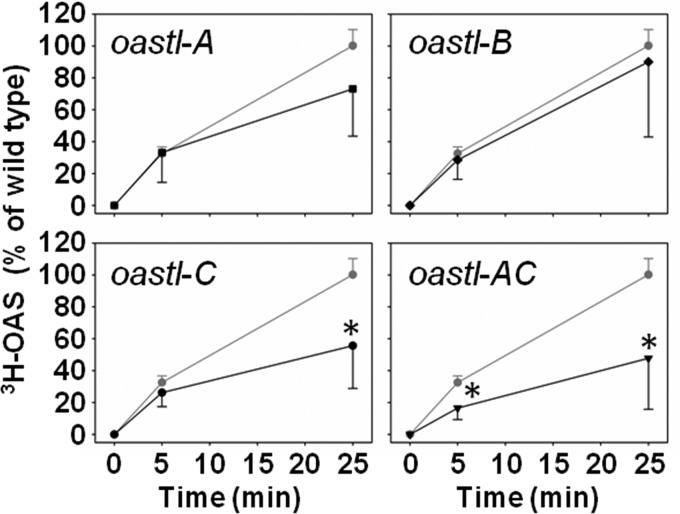

Cellular OAS Synthesis Is Regulated by CSC Formation in Mitochondria

The significant export of OAS from mitochondria of WT Arabidopsis plants, together with the importance of mitochondrial SAT in the control of cysteine synthesis (2), prompted us to test whether disruption of the CSC in Arabidopsis loss-of-function mutants for OAS-TLs in different subcellular compartments affects the in vivo activity of SAT. Leaves of soil-grown WT, oastl-A, oastl-B, oastl-C, and oastl-AC plants were incubated in the light for 5 and 25 min with radioactively labeled [3H]serine. The incorporation capacity of serine was significantly decreased to ∼50% of the WT capacity in leaves of oastl-C mutants after 25 min (Fig. 4). This decrease was already apparent after 5 min of [3H]serine treatment in oastl-C plants, although the change was not significant. In contrast, the short-term incorporation capacity of serine was not affected by disruption of the plastidic CSC in oastl-B plants and was only marginally affected in oastl-A plants after 25 min. The double mutant oastl-AC showed the same reduction in the incorporation capacity of serine into OAS as the oastl-C mutant, but it was already significantly affected after 5 min (Fig. 4). These results are in agreement with the minor contribution of plastidic and cytosolic SATs to the total SAT activity in leaves (11).

FIGURE 4.

Serine incorporation rates by WT and oastl loss-of-function mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. WT (gray circles) and cytosolic (oastl-A; black squares), plastidic (oastl-B; black diamonds), mitochondrial (oastl-C; black circles), and oastl-AC (inverted black triangles) loss-of-function mutants were grown for 7 weeks on soil under short day conditions and tested for incorporation of [3H]serine as described (12). Incorporation of [3H]serine into OAS by SAT was determined after 5 and 25 min of incubation in the light. Error bars represent S.D. (n = 6). Asterisks indicate significant differences. * = p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Formation of the CSC in Mitochondria

We have demonstrated that SAT3 and OAS-TL C can interact in plant mitochondria to form the CSC. This occurs even though SAT3 produces the bulk of the cellular OAS, which in vitro has the ability to dissociate the CSC (Fig. 1H) (2, 11, 13). Formation of the mCSC might be promoted by the stabilizing effect of sulfide (Fig. 1H) (8), by efficient export of OAS from mitochondria (Figs. 2 and 3), or by a combination of both. The bulk of cellular sulfide is produced in plastids by the activity of sulfite reductase, which results in a sulfide gradient between compartments of the plant cell (13, 26). Furthermore, sulfide efficiently inhibits cytochrome c oxidase-dependent respiration, and it can be scavenged in mitochondria in an OAS-TL C-independent manner (27). These observations suggest that the steady-state level of sulfide is low in mitochondria, making it unlikely that sulfide alone accounts for an efficient stabilization of the mCSC.

Reverse genetic approaches indicated significant export of OAS from mitochondria to support synthesis of cysteine in the cytosol and plastids (2, 11, 12). In both compartments, sulfide and OAS encounter a high excess of the free catalytically active OAS-TL dimer (12) that is necessary for full conversion of OAS to cysteine (28, 29). In contrast to plastids, which have a >300-fold excess of OAS-TL over SAT activity, the excess of free OAS-TL in mitochondria is ∼4-fold (10, 12, 29). The low sulfide level and the ratio of OAS-TL to SAT activity in mitochondria indicate that the major function of OAS-TL C is regulation of SAT in the CSC rather than conversion of OAS to cysteine. In agreement with this proposal, the NMR studies of isolated mitochondria provide direct evidence for the export of OAS from mitochondria. Neutral amino acids have been shown to permeate across the mitochondrial membranes by carrier- and/or channel-mediated processes (30, 31). To date, however, the identities of the mitochondrial OAS exporter and the transporters for serine and most other amino acids remain unknown in plants (32).

Cysteine is essential in mitochondria to meet demands for efficient biosynthesis of mitochondrially encoded proteins and iron-sulfur clusters. A high demand of cysteine could be the cause of the high mitochondrial OAS synthesis rate if cysteine is predominantly formed in the mitochondria by OAS-TL C. In contrast to this idea, the abundance of mitochondrially encoded proteins and iron-sulfur cluster-containing proteins is found to be unaltered in the oastl-C mutant, indicating sufficient cysteine transport from the cytosol to the mitochondria to meet the cysteine demand in oastl-C mitochondria (27).

Predominant synthesis of OAS in mitochondria implies co-regulation with plastidic sulfide production for efficient cysteine synthesis. Transport of OAS from the mitochondria to the cytosol allows mitochondrial OAS to control transcription of the nuclear encoded adenosine-phosphosulfate reductase, which is the enzyme with the greatest control over sulfide production in plastids (Refs. 33 and 34; reviewed in Ref. 35).

Regulation of SAT Activity by CSC Formation

Formation of the CSC in mitochondria provides the molecular basis for regulation of the major SAT activity in Arabidopsis in response to OAS and sulfide supply (14, 23). Recently, in vitro studies of a soybean CSC and the mCSC of Arabidopsis indicated that modulation of SAT cysteine feedback inhibition by CSC formation is part of this regulatory circle (14, 36). Remarkably, the cysteine feedback sensitivity of SAT5 and SAT of E. coli is not controlled by formation of the cytosolic CSC from Arabidopsis and the bacterial CSC, respectively (14). Here, we have provided evidence for the CSC-dependent regulation of the feedback inhibition of SAT3 by cysteine with in situ NMR studies of isolated mitochondria. Whether the cysteine-dependent regulation of the mCSC also applies to cytosolic and plastidic CSCs in Arabidopsis is questionable because cytosolic, plastidic, and mitochondrial SATs are subject to different cysteine feedback inhibition sensitivities (37). The 50% decrease in the incorporation capacity of serine into OAS in oastl-C and oastl-AC is in agreement with the expected predominant role of the mCSC in regulation of total SAT activity (2, 11, 13) and provides a molecular explanation for the observed growth phenotype of the oastl-C mutant (12). The decrease in the total serine incorporation capacity in the oastl-A mutant after 25 min points to a role for the cytosolic CSC in regulation of cellular SAT activity, although to a minor extent compared with the mCSC. Modulation of the cysteine feedback sensitivity of SAT3 by CSC formation provides an elegant explanation for the so far unexplained biochemical phenotype of the sulfite reductase knockdown mutant (sir1-1). The leaf OAS level only doubled in sir1-1, even though the sulfate incorporation rate was 18-fold lower than in the WT (23), demonstrating a significant down-regulation of the in vivo SAT activity. Nevertheless, total SAT activity and transcript levels of all SATs were unaffected in sir1-1. Moreover, the cysteine steady-state level in sir1-1 was unchanged or even higher than in the WT (26). In light of the results presented here, it appears that dissociation of the mCSC by the doubled OAS level in the presence of cysteine would efficiently inhibit SAT3 and thereby adjust mitochondrial OAS synthesis to decreased sulfide production in sir1-1 plastids, without the need to reduce SAT3 expression or protein level.

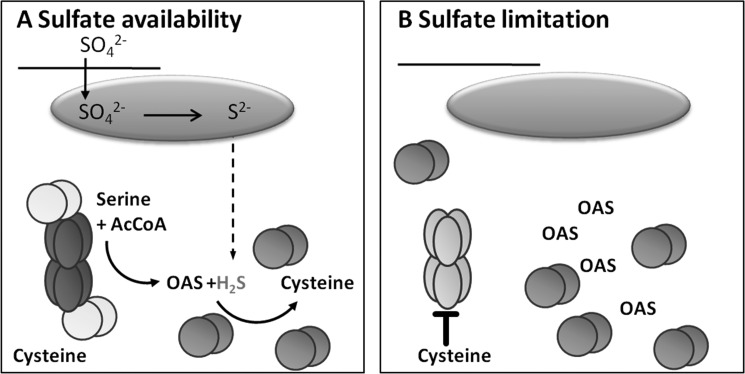

The incorporation of cysteine into the regulatory model of the CSC establishes a new sensory function for the mCSC. OAS and sulfide are primary readouts for the sulfur supply of the cell. In contrast, cysteine is widely accepted to serve as a signal for the sulfur demand of the cell (1). In the updated model for regulation of SAT activity by CSC formation proposed here, sensing of sulfur demand via cysteine allows specification of the consequences of CSC dissociation. The increase in OAS that leads to dissociation of the CSC could occur for two reasons: (i) as a result of sulfide limitation (sulfur starvation response) and (ii) to meet a high demand for cysteine synthesis (e.g. upon oxidative stress). In the first scenario, SAT activity will be shut down as a result of the maintained cysteine levels (sir1-1), whereas in the second scenario, the cysteine level will drop due to increased cysteine consumption. The lower cysteine level will allow sufficient SAT activity to ensure an adequate flux from serine to cysteine, even when the SAT is not fully incorporated into the CSC (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Updated model for regulatory function of the CSC. The model concentrates on the regulatory impact of OAS and cysteine on SAT3 by CSC dissociation. A, under normal sulfur supply, sulfate is transported from the extracellular space via the cytosol into the plastids (green oval), where it is reduced to sulfide. Sulfide can leave the plastids to serve in other subcellular compartments as a substrate for cysteine synthesis by free OAS-TL dimers (orange spheres). The bulk of OAS is synthesized by CSC-associated SAT3 (dark blue ellipses). OAS leaves the CSC because complex-associated OAS-TL dimers (yellow spheres) are catalytically inactive. B, limitation of sulfate results in a decrease in sulfide and an increase in OAS concentrations, resulting in dissociation of the CSC. SAT activity decreases upon dissociation of the CSC because free SAT3 hexamers (light blue ellipses) are sensitive to inhibition by cysteine.

In summary, we have provided evidence for the predominant role of the mCSC in regulating SAT3 activity and consequently cysteine production in leaves of Arabidopsis. This regulation is based on the OAS- and sulfide-dependent dissociation state of the mCSC and on the availability of cysteine that regulates free SAT3 by feedback inhibition. These results are integrated into an updated model for the regulatory function of the CSC.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the Landesgraduiertenförderung Baden-Württemberg (Hartmut Hoffmann-Berling International Graduate School of Molecular and Cellular Biology, BioQant Graduate School Molecular Machines), the Schmeil-Stiftung (Heidelberg), and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants He1848/5-2 and He1848/13-1) (to C. H.); a UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council CASE studentship and Advanced Technologies (Cambridge, United Kingdom) (to K. F. M. B.); and a New College Oxford Weston junior research fellowship (to M. S.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- SAT

- serine acetyltransferase

- OAS

- O-acetylserine

- OAS-TL

- OAS (thiol) lyase

- CSC

- cysteine synthase complex

- mCSC

- mitochondrial CSC

- eYFP

- enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- eCFP

- enhanced cyan fluorescent protein

- TES

- 2-{[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]amino}ethanesulfonic acid (systematic)

- NAS

- N-acetyl[3-13C]serine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hell R., Wirtz M. (2011) Molecular biology, biochemistry, and cellular physiology of cysteine metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Arabidopsis Book 9, e0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haas F. H., Heeg C., Queiroz R., Bauer A., Wirtz M., Hell R. (2008) Mitochondrial serine acetyltransferase functions as a pacemaker of cysteine synthesis in plant cells. Plant Physiol. 148, 1055–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sirko A., Błaszczyk A., Liszewska F. (2004) Overproduction of SAT and/or OASTL in transgenic plants: a survey of effects. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1881–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wirtz M., Droux M., Hell R. (2004) O-Acetylserine (thiol) lyase: an enigmatic enzyme of plant cysteine biosynthesis revisited in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1785–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lehmann M., Schwarzländer M., Obata T., Sirikantaramas S., Burow M., Olsen C. E., Tohge T., Fricker M. D., Møller B. L., Fernie A. R., Sweetlove L. J., Laxa M. (2009) The metabolic response of Arabidopsis roots to oxidative stress is distinct from that of heterotrophic cells in culture and highlights a complex relationship between the levels of transcripts, metabolites, and flux. Mol. Plant 2, 390–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawashima C. G., Berkowitz O., Hell R., Noji M., Saito K. (2005) Characterization and expression analysis of a serine acetyltransferase gene family involved in a key step of the sulfur assimilation pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 137, 220–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saito K. (2000) Regulation of sulfate transport and synthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3, 188–195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wirtz M., Hell R. (2006) Functional analysis of the cysteine synthase protein complex from plants: structural, biochemical, and regulatory properties. J. Plant Physiol. 163, 273–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feldman-Salit A., Wirtz M., Hell R., Wade R. C. (2009) A mechanistic model of the cysteine synthase complex. J. Mol. Biol. 386, 37–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wirtz M., Heeg C., Samami A. A., Ruppert T., Hell R. (2010) Enzymes of cysteine synthesis show extensive and conserved modification patterns that include Nα-terminal acetylation. Amino Acids 39, 1077–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Watanabe M., Mochida K., Kato T., Tabata S., Yoshimoto N., Noji M., Saito K. (2008) Comparative genomics and reverse genetic analysis reveal indispensable functions of the serine acetyltransferase gene family in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20, 2484–2496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heeg C., Kruse C., Jost R., Gutensohn M., Ruppert T., Wirtz M., Hell R. (2008) Analysis of the Arabidopsis O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase gene family demonstrates compartment-specific differences in the regulation of cysteine synthesis. Plant Cell 20, 168–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krueger S., Niehl A., Lopez Martin M. C., Steinhauser D., Donath A., Hildebrandt T., Romero L. C., Hoefgen R., Gotor C., Hesse H. (2009) Analysis of cytosolic and plastidic serine acetyltransferase mutants and subcellular metabolite distributions suggests interplay of the cellular compartments for cysteine biosynthesis in Arabidopis. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 349–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wirtz M., Birke H., Heeg C., Müller C., Hosp F., Throm C., König S., Feldman-Salit A., Rippe K., Petersen G., Wade R. C., Rybin V., Scheffzek K., Hell R. (2010) Structure and function of the hetero-oligomeric cysteine synthase complex in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32810–32817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wirtz M., Berkowitz O., Droux M., Hell R. (2001) The cysteine synthase complex from plants. Mitochondrial serine acetyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana carries a bifunctional domain for catalysis and protein-protein interaction. Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 686–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sparkes I. A., Runions J., Kearns A., Hawes C. (2006) Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2019–2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karpova T. S., Baumann C. T., He L., Wu X., Grammer A., Lipsky P., Hager G. L., McNally J. G. (2003) Fluorescence resonance energy transfer from cyan to yellow fluorescent protein detected by acceptor photobleaching using confocal microscopy and a single laser. J. Microsc. 209, 56–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Day D. A., Neuburger M., Douce R. (1985) Biochemical characterization of chlorophyll-free mitochondria from pea leaves. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 12, 219–228 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sweetlove L. J., Taylor N. L., Leaver C. J. (2007) Isolation of intact, functional mitochondria from the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Methods Mol. Biol. 372, 125–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith A. M., Ratcliffe R. G., Sweetlove L. J. (2004) Activation and function of mitochondrial uncoupling protein in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51944–51952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morgan M. J., Lehmann M., Schwarzländer M., Baxter C. J., Sienkiewicz-Porzucek A., Williams T. C., Schauer N., Fernie A. R., Fricker M. D., Ratcliffe R. G., Sweetlove L. J., Finkemeier I. (2008) Decrease in manganese superoxide dismutase leads to reduced root growth and affects tricarboxylic acid cycle flux and mitochondrial redox homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 147, 101–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fox G. G., Ratcliffe R. G., Southon T. E. (1989) Airlift systems for in vivo NMR spectroscopy of plant tissues. J. Magn. Reson. 82, 360–366 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Berkowitz O., Wirtz M., Wolf A., Kuhlmann J., Hell R. (2002) Use of biomolecular interaction analysis to elucidate the regulatory mechanism of the cysteine synthase complex from Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30629–30634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith A. M. (2004) Investigating the TCA Cycle in Isolated Plant Mitochondria Using NMR. Ph.D. thesis, University of Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 25. Flavin M., Slaughter C. (1965) Synthesis of the succinic ester of homoserine, a new intermediate in the bacterial biosynthesis of methionine. Biochemistry 4, 1370–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khan M. S., Haas F. H., Samami A. A., Gholami A. M., Bauer A., Fellenberg K., Reichelt M., Hänsch R., Mendel R. R., Meyer A. J., Wirtz M., Hell R. (2010) Sulfite reductase defines a newly discovered bottleneck for assimilatory sulfate reduction and is essential for growth and development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22, 1216–1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Birke H., Haas F. H., De Kok L. J., Balk J., Wirtz M., Hell R. (2012) Cysteine biosynthesis, in concert with a novel mechanism, contributes to sulfide detoxification in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. J. 445, 275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Droux M., Ruffet M. L., Douce R., Job D. (1998) Interactions between serine acetyltransferase and O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase in higher plants–structural and kinetic properties of the free and bound enzymes. Eur. J. Biochem. 255, 235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ruffet M. L., Droux M., Douce R. (1994) Purification and kinetic properties of serine acetyltransferase free of O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase from spinach chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 104, 597–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cybulski R. L., Fisher R. R. (1977) Mitochondrial neutral amino acid transport: evidence for a carrier mediated mechanism. Biochemistry 16, 5116–5120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cavalieri A. J., Huang A. H. (1980) Carrier protein-mediated transport of neutral amino acids into mung bean mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 66, 588–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Linka N., Weber A. P. (2010) Intracellular metabolite transporters in plants. Mol. Plant 3, 21–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hirai M. Y., Fujiwara T., Awazuhara M., Kimura T., Noji M., Saito K. (2003) Global expression profiling of sulfur-starved Arabidopsis by DNA macroarray reveals the role of O-acetyl-l-serine as a general regulator of gene expression in response to sulfur nutrition. Plant J. 33, 651–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koprivova A., Suter M., den Camp R. O., Brunold C., Kopriva S. (2000) Regulation of sulfate assimilation by nitrogen in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 122, 737–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kopriva S., Koprivova A. (2004) Plant adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase: the past, the present, and the future. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1775–1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kumaran S., Yi H., Krishnan H. B., Jez J. M. (2009) Assembly of the cysteine synthase complex and the regulatory role of protein-protein interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10268–10275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Noji M., Inoue K., Kimura N., Gouda A., Saito K. (1998) Isoform-dependent differences in feedback regulation and subcellular localization of serine acetyltransferase involved in cysteine biosynthesis from Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32739–32745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.