Abstract

Drosophila melanogaster flies concentrate behavioral activity around dawn and dusk. This organization of daily activity is controlled by central circadian clock neurons, including the lateral ventral pacemaker neurons (LNvs) that secrete the neuropeptide PDF (Pigment Dispersing Factor). Previous studies have demonstrated the requirement for PDF signaling to PDF receptor (PDFR)-expressing dorsal clock neurons in organizing circadian activity. While LNvs also express functional PDFR, the role of these autoreceptors has remained enigmatic. Here we show that (1) PDFR activation in LNvs shifts the balance of circadian activity from evening to morning, similar to behavioral responses to summer-like environmental conditions and (2) this shift is mediated by stimulation of the Ga,s-cAMP pathway and a consequent change in PDF/neurotransmitter co-release from the LNvs. These results suggest a novel mechanism for environmental control of the allocation of circadian activity and provide new general insight into the role of neuropeptide autoreceptors in behavioral control circuits.

Introduction

Drosophila melanogaster flies concentrate their behavioral activity around dawn and dusk (Helfrich-Forster, 2000) and sleep mostly at night and in the middle of the day (Hendricks et al., 2000; Shaw et al., 2000). In 12hr:12hr light:dark (LD) conditions, their daily morning and evening activity bouts begin before the environmental transitions, and the the timing and amplitude of these activity bouts are influenced by daily dynamics of ambient temperature and light (Majercak et al., 1999; Vanin et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2010b). These morning and evening activity bouts persist in constant darkness (DD), indicating the sufficiency of the internal timekeeping system for their generation. Both entrained activity rhythms in LD and free-running rhythms in DD are driven by a network of central circadian clock neurons (Nitabach and Taghert, 2008).

Of the approximately 75 bilateral pairs of circadian neurons, only small and large lateral ventral circadian clock neurons (sLNvs and lLNvs; 9 bilateral pairs) secrete the neuropeptide PDF (Pigment Dispersing Factor) (Helfrich-Forster, 1995; Renn et al., 1999). lLNvs project to the optic lobes and the accessory medulla (AMe) and sLNvs project to the doral brain region (Helfrich-Forster et al., 2007), where PDF secretion is likely circadian, reaching a maximum at about dawn (Cao and Nitabach, 2008; Park et al., 2000). Secreted PDF acting on clock cells expressing the PDF receptor (PDFR) is required for normal circadian function (Hyun et al., 2005; Im and Taghert, 2010; Lear et al., 2005; Lear et al., 2009; Mertens et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2010a). PDFR is expressed more broadly than PDF in the circadian network: the receptor is expressed in the PDF-negative dorsal clock neurons (dorsal neuron groups (DNs) and dorsolateral neuron group (LNds)) as well as in the PDF-positive sLNvs and in some PDF-positive lLNvs (Im and Taghert, 2010; Kula-Eversole et al., 2010; Shafer et al., 2008). PDFR is a G protein-coupled receptor (Hyun et al., 2005; Lear et al., 2005; Mertens et al., 2007), which couples to adenylyl cyclase/cAMP in HEK293 cells and all clock neurons expressing PDFR but the lLNvs (Shafer et al., 2008). PDFR maintains some intracelluar signaling specificity by coupling to specific adenylyl cyclase isoforms that differ in different clock cell groups (Duvall and Taghert, 2012). PDF signaling is critical for normal circadian behavior, as genetic ablation of PDF or PDFR leads to loss of circadian morning activity and phase-advanced evening activity in LD as well as weakened free-running rhythms with short periods in DD (Hyun et al., 2005; Lear et al., 2005; Mertens et al., 2005; Renn et al., 1999). Interestingly, the circadian functions of PDF and PDFR are similar to those of VIP and VIPR (Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide and VIP Receptor), which are expressed by clock neurons in the mammalian suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and are required in mice for robust circadian wheel-running rhythms and synchronized rhythms of clock gene expression (Aton et al., 2005; Colwell et al., 2003; Harmar et al., 2002; Maywood et al., 2006).

Recent studies indicate that PDF secretion from sLNvs to the PDF-negative dorsal clock clock neurons is critical for generating circadian morning activity and robust free-running locomotor activity rhythms (Grima et al., 2004; Lear et al., 2009; Shafer and Taghert, 2009; Stoleru et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2010a). The phase of circadian morning activity is correlated with the phase of daily rhythmic PDF secretion (Wu et al., 2008b), suggesting that PDF rhythms encode timing information for circadian morning activity. In addition, the magnitude of PDF signaling to dorsal clock neurons can also influence the pace of free-running locomotor rhythms (Choi et al., 2009; Wulbeck et al., 2008). These studies indicate a key role of PDF signaling from LNvs to PDF-negative dorsal clock neurons in organizing daily activity.

What remains enigmatic is the function of PDFR autoreceptors in PDF-positive LNv clock neurons. It has been suggested that these autoreceptors contribute to stronger free-running rhythms in DD, as PDFR null-mutant flies with rescue of PDFR in all clock neurons exhibit more robust free-running rhythms than flies with PDFR rescue solely in PDF-negative clock neurons (Lear et al., 2009). Furthermore, there is evidence that lLNvs mediate light-induced phase-shifts in late night, and it has been suggested that PDF signals from lLNvs to sLNvs underlie these phase-shifts (Shang et al., 2008). However, direct evidence for a specific role of LNv PDFR autoreceptor activation has remained absent. Here, we show that sLNv PDFR activation determines the allocation of daily circadian activity between the morning and evening by engaging the Gα,s-cAMP pathway, depolarizing the sLNvs, and modulating secretion of PDF and classical synaptic neurotransmitter. These results not only resolve the question of a functional role for PDF autoreceptors in the control of circadian acitivity rhythms, but also provide general insight into neuropeptide autoreceptor modulation of behavioral control circuits.

Results

PDFR Activation In LNv Pacemaker Cells Increases “Morningness” of Daily Activity

In order to assess the role of PDFR autoreceptors in the PDF-positive LNv pacemaker neurons in organizing daily circadian activity, we cell-autonomously activated LNv PDFR by transgenic expression of membrane-tethered PDF (t-PDF) (Choi et al., 2009). t-PDF is a genetically encoded PDFR agonist with active PDF covalently linked to the cell surface via a C terminal GPI (glycophosphatidylinositol) anchor whose lipid chains are intercalated in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane (Choi et al., 2009). GPI-anchoring limits the action of t-PDF to the cell in which it is expressed, where it cell-autonomously activates native PDFR without affecting PDFR on neighboring cells (Choi et al., 2009). Using the GAL4-UAS expression system, t-PDF expression can be genetically targeted to specifically activate PDFR in selected cells in vivo (Choi et al., 2009). We combined the LNv-specific pdf-GAL4 driver (Renn et al., 1999) with UAS-t-PDF effector transgene to induce t-PDF expression specifically in the PDF-positive LNvs. Two, four or six independent chromosomal insertions of UAS-t-PDF transgene were combined with the pdf-GAL4 driver (pdf > 2x t-PDF, pdf > 4x t-PDF or pdf > 6x t-PDF) for examination of dose-dependent effects of PDFR activation. Flies with pdf-GAL4 and six copies of UAS-t-SCR, an inert isoform of UAS-t-PDF with the amino acid sequence of the PDF peptide moiety scrambled (Choi et al., 2009), were used as negative controls (pdf > 6x t-SCR).

In 12 hr/12hr light/dark (LD) conditions, LNv PDFR activation leads to increased morning anticipatory activity before lights-on, with greater t-PDF expression resulting in correspondingly greater increased morning anticipatory activity (Figure 1A and 1D). In contrast, the locomotor profile during the light phase is little affected (Figure 1A). Activity profiles during the first day after release into constant darkness (DD1) reveal free-running circadian rhythmic activity (Lear et al., 2009). Like in LD, flies in DD exhibit a dose-dependent effect of LNv PDFR activation, with greater t-PDF expression increasing the ratio of circadian activity in the subjective morning to that in the subjective evening (Figure 1B, 1F), even over multiple days in DD (Figure 1C). This increase in “morningness” of circadian activity is primarily due to increased morning activity in this experiment, but in some cases, it is mediated by a decrease in evening activity (see, e.g., Figure 2A, third panel, second row, Supplemental Table 1). LNv PDFR activation accelerates free-running rhythms in DD (Figure 1C, 1F), which may contribute to the increased morning anticipatory activity as a consequence of phase advance (Figure 1A, 1D). These results demonstrate that increased PDFR activation in LNvs has two effects: shifting the allocation of daily activity in favor of morning and advancing the phase of morning activity.

Figure 1. Activation of PDFR autoreceptors in LNvs increases morningness and accelerates free-running rhythms.

(A) Average LD locomotor histograms. Filled bars and unfilled bars represent 30 minute bin activity during light phase (ZT0-ZT12) and dark phase (ZT12-ZT0) respectively. Flies expressing t-PDF show greater morning anticipation with increasing numbers of UAS-t-PDF transgenes. Negative controls are flies expressing the inert t-PDF isoform, t-SCR, from six UAS-t-SCR transgenes (pdf > 6x t-SCR). See Supplemental Table 1 for Ns.

(B) Average locomotor histograms on the first day of DD (DD1, ZT15-CT18) for the same flies as in (A). The size of morning peak relative to the evening peak increases with increasing dose of t-PDF. See Supplemental Table 1 for Ns.

(C) Averaged actograms for 11 days in constant darkness (DD1 – DD11) for the same flies as in (A). Black bars indicate subjective night and grey bars indicate subjective day. See Supplemental Table 1 for Ns.

(D) LNv PDFR activation increases morning anticipatory activity during the 3 hours prior to lights-on (ZT21-ZT0) in LD in a dose-dependent manner. One-Way ANOVA indicates significant differences between genotypes (P < 0.0001), and Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple-Comparison test (α = 0.05) reveals significantly greater morning anticipatory activity in pdf > 4x t-PDF than in controls and pdf > 2x t-PDF flies, and even greater morning anticipatory activity in pdf > 6x t-PDF flies.

(E) LNv PDFR activation shifts circadian activity to the subjective morning, as revealed by comparisons of morning ratios, which is defined as the ratio of total activity during the morning peak to the total activity peak during the evening peak (see Methods). One-Way ANOVA indicate significant differences between genotypes (P < 0.0001), and Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple-Comparison Test (α = 0.05) reveal significantly greater morningness in pdf > 6x t-PDF flies.

(F) Average free-running periods during the first 11 days in DD. Free-running rhythms accelerate with increasing t-PDF copy number. One-way ANOVA indicate significant difference among genotypes (P < 0.0001), and Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple-Comparison Test (α = 0.05) indicate significantly shorter free-running periods in pdf > 4x t-PDF and pdf > 6x t-PDF compared to the control.

(D–G) Genotype labels at the top of each bar indicate significant differences from, a: pdf > 6x t-SCR, b: pdf > 2x t-PDF, c: pdf > 4x t-PDF, d: pdf > t-PDF, as detected by Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple Comparison Test (α = 0.05). Bars and error bars indicate mean and standard errors.

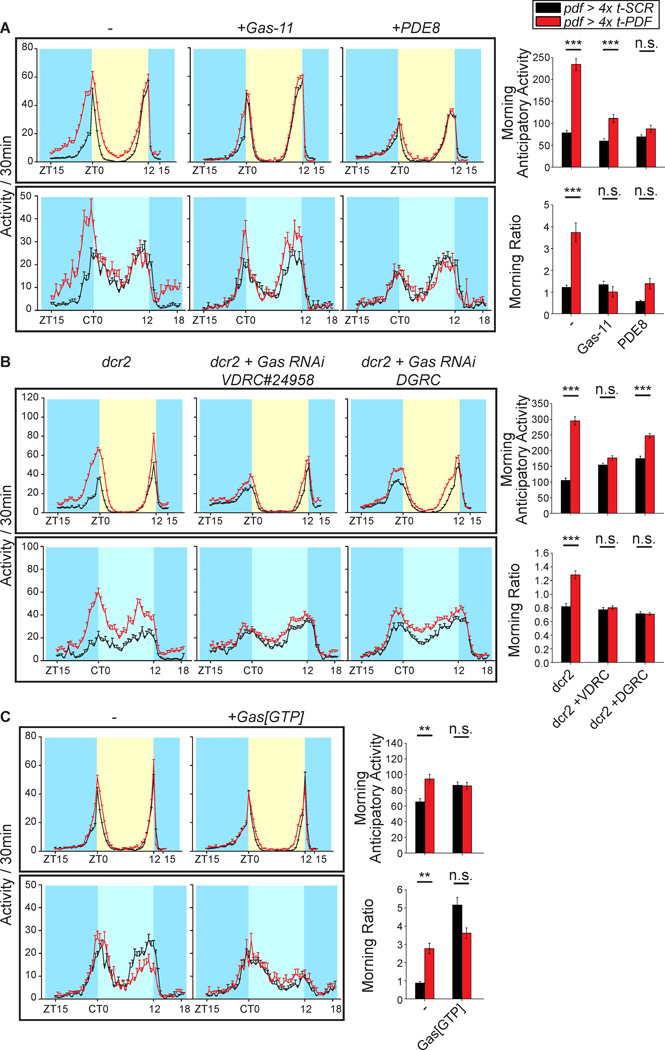

Figure 2. PDFR autoreceptor activation increases morningness through Gα,s-cAMP-pathway.

(A) Inhibition of Gα,s or phosphodiesterase-8 overexpression in LNvs suppress LNv PDFR activation induced morningness increase. Line graphs represent average LD and DD1 activity of flies expressing Gα,s peptide inhibitor (Gα,s-11) or phosphodiesterase 8 (PDE8) with either 4x t-PDF or 4x t-SCR. One-way ANOVA indicate significant differences in morning anticipatory activity (P < 0.0001) and morning ratio (P < 0.0001) among genotypes. Increase in morning anticipatory activity induced by t-PDF expression is partially suppressed by Gα,s-11 and fully suppressed by PDE8 co-expression. t-PDF expression induced increase in morning ratio is fully suppressed by Gα,s-11 or PDE8 co-expression. See Supplemental Table 1 for Ns.

(B) RNAi knockdown of Gα,s suppress morningness increase induced by PDFR activation in LNvs. Line graphs represent average LD and DD1 activity of flies expressing Dicer, transgenes for RNAi knockdown of Gα,s (Gαs RNAi VDRC#24958 and Gαs RNAi DGRC) and either 4x t-PDF or 4x t-SCR. One-way ANOVA indicate significant differences in morning anticipatory activity (P < 0.0001) and morning ratio (P < 0.0001) among genotypes. Increase in morning anticipatory activity and morning ratio induced by t-PDF expression is fully suppressed by Gαs RNAi VDRC#24958 co-expression. Co-expression of Ga,s RNAi DGRC also fully suppresses the t-PDF induced morning ratio increase, but only partially suppresses morning anticipatory activity increase, likely reflecting the less complete Gα,s knockdown by Gαs RNAi DGRC than by Gαs RNAi VDRC#24958. See Supplemental Table 1 for Ns.

(C) Activation of Gα,s pathway by expression of constitutively active Gα,s mutant (Gα,s[GTP]) increases morningness with or without PDFR activation. Line graphs represent average LD and DD1 activity of flies expressing Gα,s[GTP] with either 4x t-PDF or 4x t-SCR. One-way ANOVA indicate significant differences in morning anticipatory activity (P < 0.01) and morning ratio (P < 0.0001) among genotypes. Either t-PDF or Gα,s[GTP] expression significantly increased morning anticipatory activity or morning ratio, without no additive effects of t-PDF and Gα,s[GTP] co-expression on morningness. See Supplemental Table 1 for Ns.

(A–C) Yellow indicate day, blue indicate night and subjective night and light blue indicates subjective day. n.s., not significant; *, • = 0.05; **, • = 0.01; ***, • = 0.001; significant difference detected by Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple-Comparison Test. Bars and error bars indicate means and standard errors.

PDFR-mediated Increased Morningness Requres Gα,s-cAMP Signaling

PDFR activation increases intracellular cAMP in HEK293 cells and most clock neurons (including sLNvs), indicating that PDFR is coupled to Gα,s (Choi et al., 2009; Mertens et al., 2005; Shafer et al., 2008). In order to assess whether the increased morningness induced by LNv PDFR activation is mediated by Gα,s-cAMP, we co-expressed t-PDF with a number of different transgenes that modulate this pathway. Gα,s-11 is an eleven residue peptide that competitively inhibits receptor-Gα,s interaction (Yao and Carlson, 2010) and PDE8 is a cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase that reduces intracellular cAMP levels when overexpressed (Day et al., 2005). Co-expression of either of these transgenes inhibits the behavioral effects of t-PDF expression (Figure 2A). The t-PDF effect was inhibited also by RNAi knockdown of Gα,s (Figure 2B, Supplemental Figure 1). Gα,s[GTP] contains a point mutant that impairs GTPase activity and renders the G protein constitutively active (Connolly et al., 1996; Wolfgang et al., 1996). Expression of either 4x t-PDF or Gα,s[GTP] increases morningness, and there was no additive effect of co-expression of these transgenes (Figure 2C). These genetic interactions between t-PDF and the loss-of-function or gain-of-function Gα,s-cAMP pathway perturbations indicate that LNv PDFR activation engages the Gα,s-cAMP pathway to modulate circadian morningness. Because lLNv PDFR is not coupled to adenylyl cyclase/cAMP (Shafer et al., 2008), these results support the interpretation that increased morningness is mediated by PDFR activation in sLNvs and not lLNvs.

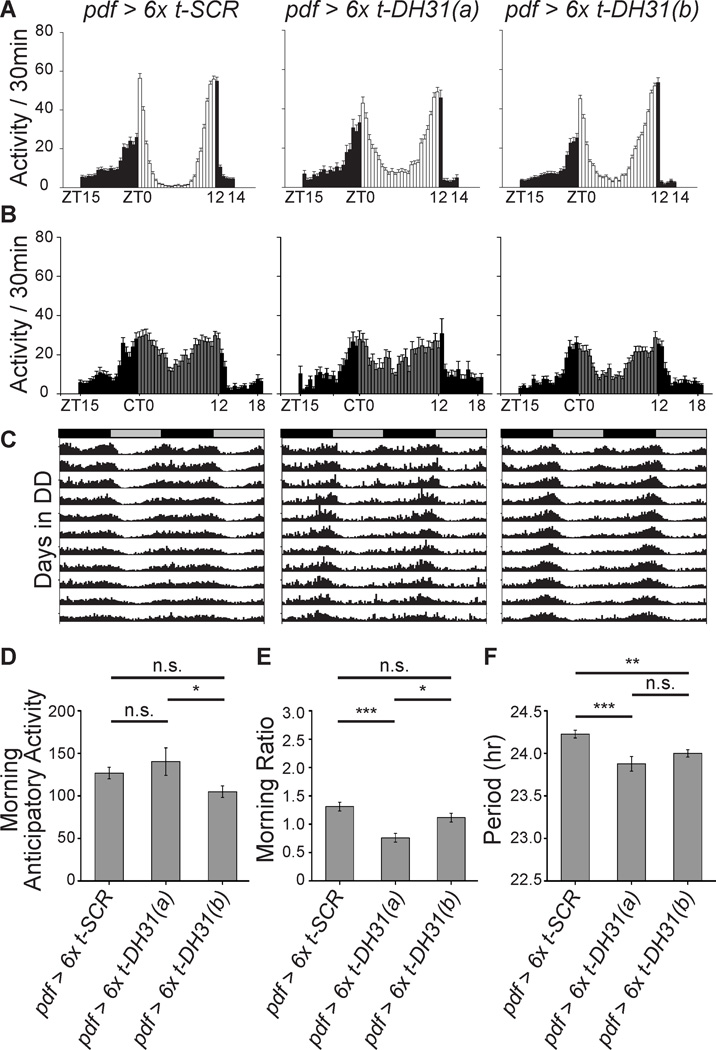

DH31R Activation In LNvs Does Not Increase Morningness

In addition to PDFR, LNvs express the receptor for the fly homologue of CGRP, DH31 (Shafer et al., 2008). DH31R (CG17415), like PDFR, is a class B1 neuropeptide receptor coupled to the Gα,s-cAMP pathway (Johnson et al., 2005), and LNvs respond to bath application of DH31 with increased intracellular cAMP (Shafer et al., 2008). In order to assess whether DH31R activation in LNvs also increases morningness, we expressed t-DH31 with two different insertion combinations of 6 copies of UAS-t-DH31 (pdf > 6x t-DH31). We have previously shown that t-DH31 strongly activates DH31R in cell culture (Choi et al., 2009). Unlike PDFR activation of LNvs, DH31R activation of LNvs increases neither morning anticipatory activity in LD nor morningness in DD and rather decreases morningness (Figure 3A, 3B, 3E). DH31R activation of LNvs does accelerate free-running rhythms but substantially less than PDFR activation (Figure 3C, 3F). This indicates that LNvs can distinguish activation of PDFR from DH31R, and that increased morningness is specific for activation of PDFR. This specificity could be in part due to the different sensitivity of LNvs to PDF and DH31, as revealed by studies showing cAMP increase to bath-applied DH31 in sLNvs and lLNvs, but cAMP increases to PDF only in sLNvs (Shafer et al., 2008). In addition, it has recently been shown that the adenylyl cyclase isoform AC3 and the AKAP (A-kinas anchoring protein) cAMP signaling pathway scaffolding protein nervy are both required for cAMP increases of sLNvs to bath-applied PDF but not to DH31 (Duvall and Taghert, 2012). This suggests that PDFR activation in LNvs modulates the daily allocation of circadian activity by intracellular signal transduction pathways that are segregated from those engaged by DH31R. Our in vivo results are consistent with these in vitro studies, and indicate that daily allocation of activity is specifically regulated by the PDF/PDFR signal transduction pathway and that LNvs can functionally distinguish between activation of the related PDFR and DH31R class B1 receptors.

Figure 3. Activation of DH31 receptors in LNvs does not increase morningness.

(A–C) Average LD (A) and DD1 (B) locomotor histograms and averaged actograms (C) of flies expressing t-DH31 in LNvs from either of two different combinations of six independent UAS-t-DH31 transgenes (6x t-DH31(a) or 6x t-DH31(b)). See Supplemental Table 1 for Ns.

(D) Mild decrease of morning anticipatory activity by LNv DH31R activation. One-way ANOVA reveals significant differences (P < 0.05), with only the pdf > 6x t-DH31(b) combination exhibiting significantly less morning anticipatory activity.

(E) Mild decrease in morningness by LNv DH31R activation. One-way ANOVA reveals significant differences (P < 0.001) with only the pdf > 6x t-DH31(a) combination exhibiting significantly less morning ratio.

(F) Free-running rhythms in DD are slightly shortened with LNv DH31R activation. One-way ANOVA, p < 0.0001.

(D–F) n.s., not significant; *, • = 0.05; **, • = 0.01; ***, • = 0.001; significant difference detected by Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple-Comparison Test. Bars and error bars indicate means and standard errors.

PDFR Activation Cell-Autonomously Depolarizes sLNvs

Previous studies show that LNv resting membrane potential (RMP) cycles over the course of the day with greatest depolarization around dawn (Cao and Nitabach, 2008; Sheeba et al., 2008b), and that altering the electrophysiological properties of LNvs leads to modified circadian locomotor rhythms (Nitabach et al., 2002; Nitabach et al., 2006; Sheeba et al., 2008a; Wu et al., 2008a; Wu et al., 2008b). These studies indicate that the electrical properties of the LNvs are integral to their role in circadian timekeeping and output. Also, the two LNv subsets play distinct roles in generating circadian rhythms and arousal, as shown in both prior studies and the results described above (Cusumano et al., 2009; Parisky et al., 2008; Shafer and Taghert, 2009; Shang et al., 2008; Sheeba et al., 2008a; Stoleru et al., 2005). Accordingly, we asked whether PDFR activation alters either lLNv or sLNv membrane activity around dawn and thereby modifies cellular output to increase morningness. To address this question, we performed whole-cell patch-clamp of the cell bodies of sLNvs and lLNvs, in pdf > 6x t-PDF and pdf > 6x t-SCR flies at ZT22–23, before dawn and around the time morning activity begins.

sLNvs of pdf > 6x t-SCR flies display regular ~1 Hz membrane potential oscillations driven by synchronous rhythmic synaptic inputs and exhibit average RMP of −55.9±4.57 mV (Figure 4A, 4B). lLNvs of these flies exhibit relatively less regular RMP oscillations at this circadian time with average RMP of −44.5±1.10 mV (Figure 4A, 4B). These observations of t-SCR-expressing control flies are consistent with eletrophysiological measurements of wild-type LNvs at this circadian time (Cao and Nitabach, 2008). There are no differences in the average RMP or the strength of membrane potential oscillations between the lLNvs of pdf > 6x t-PDF and pdf > 6x t-SCR flies (Figure 4A, 4B). However, the sLNvs of pdf > 6x t-PDF flies are significantly more depolarized than the sLNvs of pdf > 6x t-SCR flies (Figure 4A, 4B). To determine whether these changes in sLNv membrane properites are a cell-autonomous consequence of PDFR activation, we repeated these measurements in the presence of bath TTX, which blocks action potential-dependent network activity. Even in the absence of network activity, pdf > 6x t-PDF sLNvs were more depolarized than pdf > 6x t-SCR sLNvs, indicating that PDFR activation depolarizes sLNvs by altering their intrinsic membrane properties (Figure 4D, 4E). This depolarization of sLNvs in pdf > 6x t-PDF flies may in part reflect phase-advanced circadian RMP (and hence, PDF secretion) rhythms, since resting membrane potential of sLNvs progressively depolarizes from ZT16 to ZT0 (Cao and Nitabach, 2008), consistent with the behavioral phase advance in these flies (Figure 1C, 1F). However, it may also reflect a more depolarized sLNv potential and greater peak neural output, independent of phase. The depolarization of sLNvs induced by PDFR activation is an interesting parallel to the depolarization of mammalian SCN neurons induced by VIPR activation (Pakhotin et al., 2006).

Figure 4. Activation of PDFR autoreceptors in LNvs specifically depolarizes sLNvs.

(A) Representative 5 second traces of whole-cell current-clamp recordings of sLNv and lLNv clock neurons in pdf > 6x t-SCR and pdf > 6x t-PDF flies. Recordings were conducted at ZT22–23.

(B) Average resting membrane potential (RMP) of sLNv and lLNvs in pdf > 6x t-SCR and pdf > 6x t-PDF flies. t-PDF expression specifically depolarizes sLNvs, with no effect on lLNvs. There are no effects on lLNv RMP, but sLNvs are significantly depolarized with t-PDF expression. *, p < 0.03, n.s., not significant, unpaired t-test.

(C) Autocorrelation analysis of RMP oscillation of sLNv and lLNv cells in pdf > 6x t-SCR and pdf > 6x t-PDF flies. sLNv RMP oscillation is completely suppressed by t-PDF expression, while lLNvs are not affected. *, p < 0.02, n.s., not significant, Mann-Whitney U Test, See Methods.

(D) Representative 5 second traces of whole-cell current-clamp recordings of sLNv and lLNv clock neurons in pdf > 6x t-SCR and pdf > 6x t-PDF flies in the presence of bath TTX. Recordings were conducted at ZT22–23. Note the absence of regular RMP oscillations and action potentials.

(E) Average resting membrane potentials (RMP) of sLNvs and lLNvs in pdf > 6x t-SCR and pdf > 6x t-PDF flies in the presence of bath TTX. sLNvs are significantly depolarized by t-PDF expression, while lLNvs are not affected. *, p < 0.01, n.s., not significant, unpaired t-test.

(B, C, E) Bars and error bars indicate mean and standard errors. Number of recorded cells is indicated in the bars.

In addition to becoming depolarized, regular membrane potential oscillations seen in the sLNvs of pdf > 6x t-SCR flies are absent in the sLNvs of pdf > 6x t-PDF flies, as quantified by autocorrelation analysis (Figure 4A, 4C). These network dependent oscillations are a likely consequence of rhythmic synaptic activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), as has been established for lLNvs (McCarthy et al., 2011). Accordingly, depolarization towards the reversal potential for nAChR-mediated synaptic currents is predicted to decrease the magnitude of oscillation, consistent with our observations (Figure 4D). Cell-autonomous and sLNv-specific depolarization and suppression of membrane potential oscillation are PDFR-driven changes in sLNv cellular physiology that alter sLNv neural output to downstream targets controlling daily allocation of circadian activity.

PDF Output From LNvs Is Required For PDFR-Induced Morningness

What potential sLNv output pathways could be altered by PDFR-induced depolarization? PDF secretion by sLNvs is necessary for circadian morning activity (Grima et al., 2004; Renn et al., 1999; Shafer and Taghert, 2009; Stoleru et al., 2004; Stoleru et al., 2005). PDFR expression in only a restricted subset of dorsal clock neurons (DNs) is sufficient for circadian morning activity, while PDFR expression only in LNvs is not (Lear et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010a). This indicates that PDF signals from sLNvs to DNs are sufficient for circadian morning activity and suggest a possible modulatory role of PDF secretion by sLNvs to DNs for controlling morningness. To test this, we activated PDFR in LNvs using two or four copies of UAS-t-PDF in pdf01 null-mutants. This did not lead to any rescue of morning anticipation or robust circadian activity peaks (Figure 5A), indicating that PDF secretion by LNvs is a requirement for increased morningness induced by LNv PDFR activation. However, t-PDF expression and consequent cell-autonomous PDFR activation solely in PDF-negative clock neurons of pdf01 null-mutant flies rescues circadian morning activity (Figure 5B). This is consistent with the previous observation that PER rescue in per0 null-mutant flies solely in a subset of DNs rescues morning anticipation in LD, where the source of their PDF input is the clock-less LNvs (Zhang et al., 2010b). This rescue of circadian morning activity thus indicates that PDFR activation in PDF-negative clock neurons without LNv PDFR activation or LNv PDF secretion is sufficient for robust circadian morning activity. Furthermore, when we assessed PDF accumulation by immunocytochemistry in the sLNv dorsal terminals at dawn, we found higher levels of PDF accumulation in the sLNv dorsal terminals of pdf > 6x t-PDF flies than pdf > 6x t-PDF flies (Figure 5C). Since pdf > 6x t-PDF flies are more depolarized at this time (Figure 4B), it is likely that this greater PDF accumulation accompanies increased sLNv PDF output (see (Wu et al., 2008b)). Taken together, these results reinforce the idea that endogenous PDF signaling to DNs is necessary for the generation of circadian morning activity (Lear et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010a), and suggest that increased PDF output by sLNvs is involved in the PDFR autoreceptor-induced increase in morningness.

Figure 5. PDFR activation in PDF-negative clock neurons is necessary and sufficient for morning activity.

(A) PDFR activation in LNvs without PDF secretion from LNvs has no effect on circadian locomotor activity. Average LD and DD1 activity histograms of pdf01 null-mutant flies expressing 4x t-SCR, two transgene combinations of 2x t-PDF or 4x t-PDF. In LD, stereotypical lack of morning anticipation and phase-advanced evening anticipation of pdf01 null-mutant flies is seen for all genotypes with no differences in their circadian locomotor profiles. Morning anticipation phase scores indicate absent morning anticipation (phase score = 0.5) in all genotypes (One-way ANOVA, P > 0.85). In DD1, circadian activity peaks are severely dampened or absent in all genotypes. Bars and error bars indicate means and standard errors.

(B) PDFR activation in PDF-negative clock neurons is sufficient for circadian activity peaks. Average LD and DD1 activity histograms of pdf01 null-mutant flies expressing t-SCR or t-PDF from one or two transgenes in PDF-negative clock neurons, using the combination of tim-GAL4 driver active in all clock neurons and pdf-GAL80 to suppress GAL4 activity in PDF-positive LNvs. t-PDF expression in PDF-negative neurons of pdf01 null-mutant flies rescues robust morning anticipatory activity in LD as revealed by calculating morning anticipation phase scores. One-way ANOVA indicate significant differences among t-PDF expressing pdf01 null-mutants and their t-SCR expressing pdf01 null-mutant controls (P > 0.0001), and Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple-Comparison Test (*, α = 0.05) reveals significantly greater morning anticipation in t-PDF expressing pdf01 null-mutants compared to t-SCR expressing pdf01 null-mutant controls. In DD1, t-PDF expression in PDF-negative clock neurons of pdf01 null-mutant also rescues robust morning and evening circadian activity peaks that are severely damped in t-SCR-expressing controls. Bars and error bars indicate means and standard errors.

(C) Representative images of anti-PDF immunohistochemistry and average normalized PDF levels in sLNv dorsal terminals of pdf > 6x t-PDF and pdf > 6x t-SCR flies at ZT22. Bar graph shows pooled results from four independent experiments. PDF accumulation in sLNv dorsal terminals is greater in pdf > 6x t-PDF flies than in pdf > 6x t-SCR controls. ***, P < 0.0001, un-paired t-test. Bars and error bars indicate means and standard errors. Ns are indicated in the bars.

Classical Neurotransmitter Output From LNvs Is Required For PDFR-Induced Morningness

There is some evidence that classical neurotransmitters may also participate with PDF in LNv circadian output, although whether such signals are instructive to the daily allocation of activity remains unclear. Small clear vesicles (SCVs) that house classical neurotransmitters are co-localized with PDF-containing dense-core vesicles (DCVs) in the sLNv dorsal projections (Miskiewicz et al., 2004; Yasuyama and Meinertzhagen, 2010). Functionally, electrical hyperexcitation of LNvs enhances the robustness of behavioral rhythms in pdf01 null-mutants (Sheeba et al., 2008c), and blocking LNv classical neurotransmitters with tetanus toxin (TnTLC) partially rescues cellular and behavioral rhythms in constant light conditions (Umezaki et al., 2011), although it has no effect on free-running rhythms in constant darkness (Kaneko et al., 2000). To test whether classical non-peptide synaptic neurotransmitter secretion by LNvs also plays a role in PDFR-induced morningness, we used a 10x UAS-TnTLC transgene encoding tetanus toxin light chain with 10x UAS upstream promoter for improved expression (10x UAS-TnTLC, gift from Brian McCabe). TnTLC cleaves neuronal Synaptobrevin, a SNARE protein necessary for calcium-dependent classical neurotransmitter release (Sweeney et al., 1995). We co-expressed t-SCR or t-PDF with TnTLC in LNvs to block LNv synaptic output to determine whether LNv PDFR activation requires classical neurotransmission to increase morningness.

pdf > 4x t-SCR + TnTLC flies maintain robust daily circadian activity peaks and free-running rhythms (Figure 6), unlike pdf01 null-mutant flies (see controls in Figure 5 for example). This confirms the specificity of TnTLC for classical neurotransmitter secretion and lack of interference with PDF secretion. However, LNv TnTLC expression almost completely suppresses increased morningness induced by activation of PDFR in LNvs. While pdf > 4x t-PDF flies exhibit increased morning anticipatory activity and morningness compared to pdf > 4x t-SCR, identical to our earlier experiments (Figure 1), pdf > 4x t-PDF + TnTLC flies exhibit dramatically less morning anticipatory activity than pdf > 4x t-PDF flies (Figure 6A, 6D) as well as completely suppressed increase in morningness (Figure 6B, 6E). Free-running periods of pdf > 4x t-PDF + TnTLC flies are also shorter than pdf > 4x t-SCR + TnTLC flies and longer than pdf > 4x t-PDF flies (Figure 6C, 6F), suggesting an additional contribution to rhythm acceleration by classical neurotransmitter output induced by PDFR autoreceptor activation. These results indicate a key role for PDFR autoreceptor-regulated co-release of PDF and classical neurotransmitter by LNvs in the daily allocation of circadian activity.

Figure 6. Blocking classical synaptic transmission suppresses increased morningness induced by LNv PDFR autoreceptor activation.

(A–C) Average LD (A) and DD1 (B) locomotor histograms and averaged actograms (C) of flies co-expressing 4x t-PDF or 4x t-SCR with tetanus toxin light chain (TnTLC). Increased morningness induced by PDFR activation in LNvs is prevented when classical synaptic transmission is blocked by TnTLC co-expression. See Supplemental Table 1 for Ns.

(D) TnTLC co-expression strongly suppresses the increase in morning anticipatory activity induced by LNv PDFR activation. One-way ANOVA indicates significant differences in morning ratio between genotypes (P < 0.0001), and Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple-Comparison Test reveals significantly less morning anticipatory activity in pdf > 4x t-PDF + TnTLC flies than in pdf > 4x t-PDF flies.

(E) TnTLC co-expression completely inhibits the morningness increase induced by LNv PDFR activation. One-way ANOVA indicates significant differences in morning ratio between genotypes (P < 0.001), and Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple-Comparison Test reveals significant increase in morning ratio by t-PDF expression and no significant change in morning ratio by t-PDF expression when TnTLC is co-expressed.

(F) TnTLC co-expression partially suppresses the period shortening effect of LNv PDFR activation without affecting free-running period on its own. One-way ANOVA indicates significant differences in morning ratio between genotypes (p < 0.0001).

(D–F) **, p<0.01, ***, p < 0.001, significant differences detected by Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple-Comparison Test. n.s., not significant. Bars and error bars indicate means and standard errors.

Discussion

Studies of the Drosophila circadian control circuit over the past decade have revealed a critical role for neuropeptide signaling between PDF secreting LNvs and PDF-negative PDFR-expressing clock neurons for generation and maintenance of robust circadian activity rhythms. While PDF-secreting LNvs also express PDFR, little is known about the functional significance of these peptide autoreceptors, other than enhancing the robustness of free-running rhythms in DD (Lear et al., 2009). Here we show that PDFR autoreceptor activation in LNvs shifts the balance of daily circadian activity to the morning from the evening by engaging the Gα,s-cAMP pathway and thereby modulating secretion of PDF and co-released classical synaptic neurotransmitter.

While PDFR expression can be detected in both the sLNvs and lLNvs (Im and Taghert, 2010), our results suggest that PDFR-induced increased morningness is likely mediated by sLNvs rather than lLNvs. First, sLNvs respond robustly to bath-applied PDF with increased cAMP whereas lLNvs do not (Shafer et al., 2008), and downregulating Gα,s activity or cAMP levels suppresses the behavioral effects of LNv PDFR activation (Figure 2). Second, PDFR autoreceptor activation in LNvs cell-autonomously depolarizes the sLNvs while not affecting the lLNvs (Figure 4). Third, expression of t-PDF with the sLNv-specific R6-GAL4 driver induces a more robust increase in morningness than with the lLNv-specific c929-GAL4 driver (Supplemental Figure 2). Nevertheless, these findings do not rule out some contribution of PDFR autoreceptors expressed in lLNvs (Im et al., 2010) in the t-PDF induced shift of the balance of daily activity from evening to morning. While PDFR activation by bath-applied PDF does not induce a cAMP increase in lLNvs (Shafer et al., 2008), it is possible that lLNv PDFR couples to non-cAMP signaling pathways such as Ca2+ signaling (Mertens et al., 2005). However, the suppression of t-PDF induced increased morningness by disruption of Ga,s-cAMP signaling (Figure 2) indicates that any contribution of lLNv PDFR activation occurs upstream of the sLNvs.

We demonstrate that increased morningness induced by PDFR activation in LNvs requires not only PDF outputs (as expected from prior studies) but also classical synaptic neurotransmitter co-release by the LNvs (Figure 6). Other behaviors such as feeding also employ multiple co-released intercellular signals with different dynamics, with one signal instructing the behavior and the other modulating the sensitivity to the instructive signal (Root et al., 2011). There is also evidence that neuropeptide and inhibitory synaptic neurotransmitter co-secretion underlies unique behavioral adaptations (Tan and Bullock, 2008). Determining the identity of the co-released classical neurotransmitter required for PDFR autoreceptor-mediated increased morningness will provide insight into the question how sLNv outputs influence downstream circadian clock neurons to determine daily activity rhythms.

What is the physiological significance of the increased morningness induced by PDFR activation sLNvs? One clue is that this PDFR autoreceptor-induced increased morningness mimics the behavioral response of flies to summer-like lighting conditions, where morning activity is increased and/or phase advanced (Majercak et al., 1999; Stoleru et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2010b). This suggests that PDF signals to LNvs might be regulated by light conditions. Indeed, lLNvs are highly sensitive to light (Fogle et al., 2011; Sheeba et al., 2008a), contact sLNv post-synaptic sites (Helfrich-Forster et al., 2007), promote phase-advances to morning light (Shang et al., 2008), and their PDF secretion is important for entrainment by light (Cusumano et al., 2009). Thus, the lLNvs are well-situated to transfer illuminance information to the sLNvs via PDF to regulate allocation of circadian activity and phase as photoperiod changes throughout the year. Consistent with this hypothesis, hyperexcitation of lLNvs by expression of NaChBac (low threshold bacterial voltage-gated Na2+ channel) increases circadian morning activity (Supplemental Figure 3). This leads to the model of a homotypic PDF relay circuit, where summer conditions with lengthened and brighter dawn increase PDF secretion by lLNvs, thus increasing PDFR activation in sLNvs, thereby adaptively adjusting the allocation of circadian activity between morning and evening (Figure 7). Interestingly, a recent study has shown a strong temperature dependence of the timing of morning activity in natural light and temperature conditions and an induction of a prominent daytime activity bout at very high temperatures (Vanin et al., 2012), suggesting that temperature also regulates the distribution of daily activity (Zhang et al., 2010b). It is interesting to speculate that this temperature modulation of daily activity allocation relies on PDFR autoreceptors and the intra- and inter-celluar signaling pathways we have elucidated here.

Figure 7. Model of PDFR autoreceptor signaling in LNvs.

PDFR in sLNvs activates Gα,s and stimulates cAMP synthesis by adenylyl cyclase. The subsequent increase in intracellular cAMP leads to membrane depolarization, increased PDF secretion and altered secretion of an unknown neurotransmitter (NT). Increased PDF and neurotransmitter output from sLNvs induced by PDFR activation acts on secretion acts on dorsal clock neurons to increase circadian morning activity. PDFR in sLNvs is activated by increased PDF secretion by lLNvs in response to light.

There are many parallels between our model for PDFR autoreceptor signaling in the Drosophila circadian control network and VIP signaling in the mammalian circadian network of the SCN. They include the fact that VIP expressing cells in the SCN are innervated by the visual system (Tanaka et al., 1993) and that VIP secretion is stimulated by light (Francl et al., 2010). Moreover, there is evidence that VIP signals modulate SCN transcriptional responses to light (Dragich et al., 2010), mediate light-dependent phase-shifts of circadian locomotor rhythms (Colwell et al., 2003; Piggins et al., 1995), and control locomotor activity levels (Harmar et al., 2002). About 30% of all SCN VIP cells also express VIPR (Kallo et al., 2004), suggesting that VIPR autoreceptor signaling in the SCN plays a similar role to that of PDFR in modulating VIP/classical neurotransmitter co-release (Moore et al., 2002). Intriguingly, the possibility of mammalian VIPR autoreceptor signaling influencing light-dependent circadian behavior can be tested using the GPI-tethered peptide strategy we employed here in the fly. VIPR is a class B1 G protein coupled receptor (GPCR) (Dickson and Finlayson, 2009), and we have previously shown the GPI-tethered peptide design we developed in the context of the fly is generalizable to mammalian class B1 GPCR ligands (Fortin et al., 2009). Indeed, we have tested GPI-tethered VIP (t-VIP) in vitro in heterologous cells and found that it is a potent activator of VIPR (data not shown). By expressing t-VIP using the VIP promoter, analogous to our expression of t-PDF using the pdf promoter, one can test whether VIPR autoreceptor signaling modulates VIP-dependent circadian behaviors such as arousal and phase shifts. Further studies of this nature will elucidate the cellular mechanisms by which peptide autoreceptor signaling modulates sleep/wake and activity control circuits as well as reveal evolutionarily conserved principles for the modulation of daily behavioral rhythms by the environment.

Methods

Fly strains and Crosses

All crosses and behavioral experiments were performed at 25°C. UAS-t-PDF (described as UAS-t-PDF-ML in (Choi et al., 2009)), UAS-t-SCR (described as UAS-t-PDF-SCR in (Choi et al., 2009)) and UAS-t-DH31 are as described previously (Choi et al., 2009). Two independent insertions of each transgene were combined via homologous recombination to generate second and third chromosomes that contain two copies of each transgene. The 2x UAS-t-PDF or 2x UAS-t-SCR flies were further crossed to each other and the pdf-GAL4(II) driver (Renn et al., 1999) to generate flies with up to six copies of either transgene with a single copy of pdf-GAL4 (pdf-GAL4/2x UAS-t-PDF; 2x UAS-t-PDF/2x UAS-t-PDF or pdf-GAL4/2x UAS-t-SCR; 2x UAS-t-SCR/2x UAS-t-SCR).

For sLNv PDFR activation in pdf01 null background, a pdf-GAL4 insertion on the × chromosome was used. pdf-GAL4(X) was combined with 1x UAS-t-PDF or 2x UAS-t-PDF on the second chromosome and the pdf01-null third chromosome. Homozygous males with a total of 2 or 4 copies of t-PDF in the pdf-null background were used for behavioral assays (pdf-GAL4; 1x or 2x t-PDF; pdf01).

UAS-TnTLC is from Brian McCabe, UAS-Gas[GTP] gain of function mutant (Wolfgang et al., 1996), UAS-Gas-11 peptide inhibitor (Yao and Carlson, 2010) is from John Carlson, pde8EY enhancer trap line is from Justin Blau. Gas RNAi lines are obtained from Drosophila Genomics Resource Center and Vienna Drosophila Stock Center (stock numbers: 24958 and 105485).

Behavioral Assays

Locomotor activity monitoring

Individual 3–5 day old male flies were placed in locomotor activity monitor tubes and were entrained in 25°C, 12hr: 12hr light:dark condi tions (LD) for at least 5 days and then released into free running conditions of constant darkness (DD). All flies were monitored simultaneously with its respective controls. The automated TriKinetics (Waltham, MA) infrared beam-crossing monitor system was used to assay locomotor activity. 20 minute bin-size double-plotted actograms and Lomb-Scargle periodograms for assessment of free running period were generated using Actimetrics Clocklab software (Wilmette, IL), running on MATLAB. 30 minute bin averaged activity histograms in LD were generated by averaging 30 minute bin activity profiles over 4 days in LD, then averaging across animals. 30 minute bin first day of DD averaged activity histograms were generated by averaging the 30 minute bin activity profiles across animals.

Statistics of locomotor activity

Morning anticipatory activity in LD was defined as the average cumulative activity 3 hours prior to lights on (ZT22-ZT0) over four days in LD and averaged across animals within the same genotype. Morning anticipation phase score in LD was calculated to detect the presence incremental activity before lights-on, which is the ratio of activity 3 hours prior to lights-on to the activity 6 hours prior to lights-on(Harrisingh et al., 2007).

The morning peak, evening peak and morning ratio in the first day of DD for each animal was determined from moving averages of the average activities. From this smoothened activity profile, we determined the start of a peak as the starting point of a continuous increase of activity towards the peak maximum, allowing 1 step decrease in this duration. The end of a peak was determined as the end of a continuous decrease of activity from the peak maximum, allowing 1 step increase in this duration. Morning peak and evening peak were calculated as the sum of the activity in this duration, either in subjective dawn or subjective dusk, in individual animals and averaged across animals. Morning ratio was calculated as the activity during the morning peak over the activity during the evening peak, and averaged across animals. In a few animals, the evening activity was so low that the calculated morning ratio exceeded 20, and such animals were assigned a morning ratio of 20.

Free-running periods for each animal were determined using Lomb-Scargle periodograms for 11 days in constant darkness, starting on the first day of DD, and averaged for each genotype. Average actograms representing free-running behavior were generated using Actimetrics Clocklab software (Wilmette, IL), where 20 minute activities normalized to the daily activity of each animal is averaged across multiple animals of each genotype.

Statistical significance of the genotype-dependent effects on free-running period, morning activity and morning ratio were tested with One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni All-Pairwise Multiple Comparison Test with α = 0.05.

Immunocytochemistry

Adult male fly brains were dissected and processed for immunofluorescence with mouse anti-PDF (1:50) primary antibody and Cy2-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200), as described previously (citation). Anti-PDF fluorescence in the dorsal brain region was collected using a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera mounted on a Zeiss Axiophot epifluorescent photomicroscope with 64X optical lens and used for analysis. Average pixel value from the background was subtracted from the threshold-selected pixels from the dorsal PDF+ projections of that image. Integrated pixel values of the threshold-selected background subtracted images were normalized to the greatest integrated pixel value within each experiment.

Clock neuron electrophysiology

Adult Drosophila Whole-Brain Explant Preparation

Flies were maintained at 25°C in a 12hr/12hr light/ dark (LD) cycle. 7–10 days post-eclosion males of the genotypes, pdf-GAL4, UAS-DsRed/ 2x t-PDF; 2x t-PDF (6x t-PDF) or pdf-GAL4, UAS-DsRed/ 2x t-SCR; 2x t-SCR (6x t-SCR) were dissected at ZT21.5–22.5 for electrophysiological recordings. These flies express red fluorescent protein, DsRed, solely in ventral lateral clock neurons (LNV). Whole-cell recordings on small LNV (sLNVs) of fly brain explants were performed as described (Cao and Nitabach, 2008; Wu et al., 2008a)), and all recordings were done between ZT 22–23. Briefly, the fly brains were dissected in external recording solution, which consisted of (in mM): 101 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 4 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 5 Glucose, 20.7 NaHCO3, pH 7.2 with osmolarity of 250 mmol/kg. The brain was placed anterior side up, secured in a recording chamber with a mammalian brain slice “harp” holder, and was continuously perfused with external solution bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 at room temperature (22 °C). For tetrodotoxin (TTX) experiments, TTX (final concentration: 2µM) was added to the perfusion solution. sLNVs and lLNvs were visualized by DsRed fluorescence and distinguished by their sizes, and subsequently, the immediate area surrounding the sLNV or lLNv cell bodies was enzymatically digested with focal application of protease XIV (2 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich).

Whole Cell Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology

The voltage-gated and ligand-gated conductances of sLNvs – as for many adult Drosophila brain neurons – are electrotonically distant from the recording site at the soma, thus preventing voltage-clamp of those conductances. Accordingly, electrical properties of the sLNvs were assayed using current clamp, with the caveat that electrical properties measured at the soma reflect more distal properties filtered by the neuron’s cable properties.

Whole-cell recordings were performed using borosilicate standard wall capillary glass pipettes (Sutter Instrument Company, Novato, CA). Recording pipettes were filled with internal solution consisting of (in mM): 102 potassium gluconate, 17 NaCl, 0.085 CaCl2, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.5 Na-GTP, 0.94 EGTA and 8.5 HEPES, pH 7.2 and osmolarity of 235 mmol/kg. The resistance of filled pipettes was 8–12 MΩ. Gigaohm seals were achieved before breaking in to whole-cell configuration in voltage-clamp mode. To confirm maintenance of a good seal and absence of damage to the cell, a 40 mV hyperpolarizing pulse was imposed on each cell while in whole-cell voltage-clamp mode from a holding potential of −80 mV. Only if the resulting inward leak current was less than −100 pA was that cell used for subsequent measurements.

After switching from voltage-clamp to current-clamp mode, resting membrane potential (RMP) was determined after stabilization of the membrane potential (5 min after the transition). For cells with oscillating membrane potential, RMP was defined at the trough of the oscillation. Spontaneous activity was observed over the 10 min period after the transition to current-clamp configuration. All cells included in this study were capable of firing action potentials when injected with positive current. Only one sLNv or lLNv per animal was recorded.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Signals were measured using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices/Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA) and a Digidata 1440A analog/digital converter (Molecular Devices/Axon Instruments). The inward leak current and RMP were measured in Clampfit, which is part of the pClamp 10 software package. Cross-correlational analysis was also conducted in Clampfit on the last 100 s of the first 5 minutes after the transition from voltage-clamp to current-clamp mode. The signal was first filtered by a lowpass Gaussian filter with a −3 db cut off of 5 Hz. Cross-correlation was then run and the correlation was defined as the amplitude of the peak of correlation. If no peak was observed, the recording was assigned a correlation value of the minimum correlation found within the experiment. Since correlation values for some samples were not measured but assigned at a minimum, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the statistical significance of the differences in correlation. T-test was used to determine the statistical significance of the RMP.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Activation of PDF receptors in sLNv clock neurons increases circadian morning activity.

This phenotype is associated with sLNv depolarization and increased PDF secretion at dawn.

This phenotype requires the Gα,s-cAMP pathway and co-secretion of PDF and neurotransmitters.

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Taghert, L. Griffith, J. Blau, J. Carlson, and B. McCabe for fly stocks; M. Kunst for figure graphics and comments on the manuscript; M. Hughes and D. Raccuglia for advice on statistics and comments on the manuscript; and J. Duah, C. Drucker and G. Barnett for assistance in fly maintenance and assistance in behavioral experiments. Work in the laboratory of M.N.N. is supported in part by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01NS055035, R01NS058443, R21NS058330) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM098931), National Institutes of Health (NIH). C.C. is supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciencs, NIH (T32GM07527).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aton SJ, Colwell CS, Harmar AJ, Waschek J, Herzog ED. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide mediates circadian rhythmicity and synchrony in mammalian clock neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:476–483. doi: 10.1038/nn1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G, Nitabach MN. Circadian control of membrane excitability in Drosophila melanogaster lateral ventral clock neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6493–6501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1503-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C, Fortin JP, McCarthy E, Oksman L, Kopin AS, Nitabach MN. Cellular dissection of circadian peptide signals with genetically encoded membrane-tethered ligands. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell CS, Michel S, Itri J, Rodriguez W, Tam J, Lelievre V, Hu Z, Liu X, Waschek JA. Disrupted circadian rhythms in VIP- and PHI-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R939–R949. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00200.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly JB, Roberts IJ, Armstrong JD, Kaiser K, Forte M, Tully T, O'Kane CJ. Associative learning disrupted by impaired Gs signaling in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Science. 1996;274:2104–2107. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano P, Klarsfeld A, Chelot E, Picot M, Richier B, Rouyer F. PDF-modulated visual inputs and cryptochrome define diurnal behavior in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1431–1437. doi: 10.1038/nn.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JP, Dow JA, Houslay MD, Davies SA. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases in Drosophila melanogaster. The Biochemical journal. 2005;388:333–342. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson L, Finlayson K. VPAC and PAC receptors: From ligands to function. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121:294–316. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragich JM, Loh DH, Wang LM, Vosko AM, Kudo T, Nakamura TJ, Odom IH, Tateyama S, Hagopian A, Waschek JA, et al. The role of the neuropeptides PACAP and VIP in the photic regulation of gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:864–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall L, Taghert P. The circadian neuropeptide PDF signals preferentially through a specific adenylate cyclase isoform AC3 in M pacemakers of Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001337. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogle KJ, Parson KG, Dahm NA, Holmes TC. CRYPTOCHROME is a blue-light sensor that regulates neuronal firing rate. Science. 2011;331:1409–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.1199702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin JP, Zhu Y, Choi C, Beinborn M, Nitabach MN, Kopin AS. Membrane-tethered ligands are effective probes for exploring class B1 G protein-coupled receptor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8049–8054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900149106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francl JM, Kaur G, Glass JD. Regulation of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide release in the suprachiasmatic nucleus circadian clock. Neuroreport. 2010;21:1055–1059. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32833fcba4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grima B, Chelot E, Xia R, Rouyer F. Morning and evening peaks of activity rely on different clock neurons of the Drosophila brain. Nature. 2004;431:869–873. doi: 10.1038/nature02935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmar AJ, Marston HM, Shen S, Spratt C, West KM, Sheward WJ, Morrison CF, Dorin JR, Piggins HD, Reubi JC, et al. The VPAC(2) receptor is essential for circadian function in the mouse suprachiasmatic nuclei. Cell. 2002;109:497–508. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrisingh MC, Wu Y, Lnenicka GA, Nitabach MN. Intracellular Ca2+ regulates free-running circadian clock oscillation in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12489–12499. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3680-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich-Forster C. The period clock gene is expressed in central nervous system neurons which also produce a neuropeptide that reveals the projections of circadian pacemaker cells within the brain of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:612–616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich-Forster C. Differential control of morning and evening components in the activity rhythm of Drosophila melanogaster--sex-specific differences suggest a different quality of activity. J Biol Rhythms. 2000;15:135–154. doi: 10.1177/074873040001500208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich-Forster C, Shafer OT, Wulbeck C, Grieshaber E, Rieger D, Taghert P. Development and morphology of the clock-gene-expressing lateral neurons of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:47–70. doi: 10.1002/cne.21146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks JC, Finn SM, Panckeri KA, Chavkin J, Williams JA, Sehgal A, Pack AI. Rest in Drosophila is a sleep-like state. Neuron. 2000;25:129–138. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80877-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun S, Lee Y, Hong ST, Bang S, Paik D, Kang J, Shin J, Lee J, Jeon K, Hwang S, et al. Drosophila GPCR Han is a receptor for the circadian clock neuropeptide PDF. Neuron. 2005;48:267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im SH, Taghert PH. PDF receptor expression reveals direct interactions between circadian oscillators in Drosophila. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:1925–1945. doi: 10.1002/cne.22311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EC, Shafer OT, Trigg JS, Park J, Schooley DA, Dow JA, Taghert PH. A novel diuretic hormone receptor in Drosophila: evidence for conservation of CGRP signaling. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1239–1246. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallo I, Kalamatianos T, Wiltshire N, Shen S, Sheward WJ, Harmar AJ, Coen CW. Transgenic approach reveals expression of the VPAC2 receptor in phenotypically defined neurons in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus and in its efferent target sites. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2201–2211. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M, Park JH, Cheng Y, Hardin PE, Hall JC. Disruption of synaptic transmission or clock-gene-product oscillations in circadian pacemaker cells of Drosophila cause abnormal behavioral rhythms. J Neurobiol. 2000;43:207–233. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(20000605)43:3<207::aid-neu1>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kula-Eversole E, Nagoshi E, Shang Y, Rodriguez J, Allada R, Rosbash M. Surprising gene expression patterns within and between PDF-containing circadian neurons in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13497–13502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lear BC, Merrill CE, Lin JM, Schroeder A, Zhang L, Allada R. A G protein-coupled receptor, groom-of-PDF, is required for PDF neuron action in circadian behavior. Neuron. 2005;48:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lear BC, Zhang L, Allada R. The neuropeptide PDF acts directly on evening pacemaker neurons to regulate multiple features of circadian behavior. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majercak J, Sidote D, Hardin PE, Edery I. How a circadian clock adapts to seasonal decreases in temperature and day length. Neuron. 1999;24:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80834-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maywood ES, Reddy AB, Wong GK, O'Neill JS, O'Brien JA, McMahon DG, Harmar AJ, Okamura H, Hastings MH. Synchronization and maintenance of timekeeping in suprachiasmatic circadian clock cells by neuropeptidergic signaling. Curr Biol. 2006;16:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy E, Wu Y, deCarvalho T, Brandt C, Cao G, Nitabach MN. Synchornized Bilateral Synaptic Inputs to Drosophila melanogaster Neuropeptidergic Rest/Arousal Neurons. J Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2017-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens I, Husson SJ, Janssen T, Lindemans M, Schoofs L. PACAP and PDF signaling in the regulation of mammalian and insect circadian rhythms. Peptides. 2007;28:1775–1783. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens I, Vandingenen A, Johnson EC, Shafer OT, Li W, Trigg JS, De Loof A, Schoofs L, Taghert PH. PDF receptor signaling in Drosophila contributes to both circadian and geotactic behaviors. Neuron. 2005;48:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskiewicz K, Pyza E, Schurmann FW. Ultrastructural characteristics of circadian pacemaker neurones, immunoreactive to an antibody against a pigment-dispersing hormone in the fly's brain. Neuroscience letters. 2004;363:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY, Speh JC, Leak RK. Suprachiasmatic nucleus organization. Cell and tissue research. 2002;309:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitabach MN, Blau J, Holmes TC. Electrical silencing of Drosophila pacemaker neurons stops the free-running circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:485–495. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00737-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitabach MN, Taghert PH. Organization of the Drosophila circadian control circuit. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R84–R93. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitabach MN, Wu Y, Sheeba V, Lemon WC, Strumbos J, Zelensky PK, White BH, Holmes TC. Electrical hyperexcitation of lateral ventral pacemaker neurons desynchronizes downstream circadian oscillators in the fly circadian circuit and induces multiple behavioral periods. J Neurosci. 2006;26:479–489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3915-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakhotin P, Harmar AJ, Verkhratsky A, Piggins H. VIP receptors control excitability of suprachiasmatic nuclei neurones. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452:7–15. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-0003-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisky KM, Agosto J, Pulver SR, Shang Y, Kuklin E, Hodge JJ, Kang K, Liu X, Garrity PA, Rosbash M, et al. PDF cells are a GABA-responsive wake-promoting component of the Drosophila sleep circuit. Neuron. 2008;60:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Helfrich-Forster C, Lee G, Liu L, Rosbash M, Hall JC. Differential regulation of circadian pacemaker output by separate clock genes in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3608–3613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070036197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggins HD, Antle MC, Rusak B. Neuropeptides phase shift the mammalian circadian pacemaker. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5612–5622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-08-05612.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renn SC, Park JH, Rosbash M, Hall JC, Taghert PH. A pdf neuropeptide gene mutation and ablation of PDF neurons each cause severe abnormalities of behavioral circadian rhythms in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;99:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root CM, Ko KI, Jafari A, Wang JW. Presynaptic facilitation by neuropeptide signaling mediates odor-driven food search. Cell. 2011;145:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer OT, Kim DJ, Dunbar-Yaffe R, Nikolaev VO, Lohse MJ, Taghert PH. Widespread receptivity to neuropeptide PDF throughout the neuronal circadian clock network of Drosophila revealed by real-time cyclic AMP imaging. Neuron. 2008;58:223–237. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer OT, Taghert PH. RNA-interference knockdown of Drosophila pigment dispersing factor in neuronal subsets: the anatomical basis of a neuropeptide's circadian functions. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Griffith LC, Rosbash M. Light-arousal and circadian photoreception circuits intersect at the large PDF cells of the Drosophila brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19587–19594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809577105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJ, Cirelli C, Greenspan RJ, Tononi G. Correlates of sleep and waking in Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:1834–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeba V, Fogle KJ, Kaneko M, Rashid S, Chou YT, Sharma VK, Holmes TC. Large ventral lateral neurons modulate arousal and sleep in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008a;18:1537–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeba V, Gu H, Sharma VK, O'Dowd DK, Holmes TC. Circadian- and light-dependent regulation of resting membrane potential and spontaneous action potential firing of Drosophila circadian pacemaker neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2008b;99:976–988. doi: 10.1152/jn.00930.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeba V, Sharma VK, Gu H, Chou YT, O'Dowd DK, Holmes TC. Pigment dispersing factor-dependent and -independent circadian locomotor behavioral rhythms. J Neurosci. 2008c;28:217–227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4087-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoleru D, Nawathean P, Fernandez MP, Menet JS, Ceriani MF, Rosbash M. The Drosophila circadian network is a seasonal timer. Cell. 2007;129:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoleru D, Peng Y, Agosto J, Rosbash M. Coupled oscillators control morning and evening locomotor behaviour of Drosophila. Nature. 2004;431:862–868. doi: 10.1038/nature02926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoleru D, Peng Y, Nawathean P, Rosbash M. A resetting signal between Drosophila pacemakers synchronizes morning and evening activity. Nature. 2005;438:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature04192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney ST, Broadie K, Keane J, Niemann H, O'Kane CJ. Targeted expression of tetanus toxin light chain in Drosophila specifically eliminates synaptic transmission and causes behavioral defects. Neuron. 1995;14:341–351. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CO, Bullock D. Neuropeptide co-release with GABA may explain functional non-monotonic uncertainty responses in dopamine neurons. Neuroscience letters. 2008;430:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Ichitani Y, Okamura H, Tanaka Y, Ibata Y. The direct retinal projection to VIP neuronal elements in the rat SCN. Brain Res Bull. 1993;31:637–640. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90134-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezaki Y, Yasuyama K, Nakagoshi H, Tomioka K. Blocking synaptic transmission with tetanus toxin light chain reveals modes of neurotransmission in the PDF-positive circadian clock neurons of Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of insect physiology. 2011;57:1290–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanin S, Bhutani S, Montelli S, Menegazzi P, Green EW, Pegoraro M, Sandrelli F, Costa R, Kyriacou CP. Unexpected features of Drosophila circadian behavioural rhythms under natural conditions. Nature. 2012;484:371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature10991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang WJ, Roberts IJ, Quan F, O'Kane C, Forte M. Activation of protein kinase A-independent pathways by Gs alpha in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14542–14547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Cao G, Nitabach MN. Electrical silencing of PDF neurons advances the phase of non-PDF clock neurons in Drosophila. J Biol Rhythms. 2008a;23:117–128. doi: 10.1177/0748730407312984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Cao G, Pavlicek B, Luo X, Nitabach MN. Phase coupling of a circadian neuropeptide with rest/activity rhythms detected using a membrane-tethered spider toxin. PLoS Biol. 2008b;6:e273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulbeck C, Grieshaber E, Helfrich-Forster C. Pigment-dispersing factor (PDF) has different effects on Drosophila's circadian clocks in the accessory medulla and in the dorsal brain. J Biol Rhythms. 2008;23:409–424. doi: 10.1177/0748730408322699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao CA, Carlson JR. Role of G-proteins in odor-sensing and CO2-sensing neurons in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4562–4572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6357-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuyama K, Meinertzhagen IA. Synaptic connections of PDF-immunoreactive lateral neurons projecting to the dorsal protocerebrum of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:292–304. doi: 10.1002/cne.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Chung BY, Lear BC, Kilman VL, Liu Y, Mahesh G, Meissner RA, Hardin PE, Allada R. DN1(p) circadian neurons coordinate acute light and PDF inputs to produce robust daily behavior in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2010a;20:591–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu Y, Bilodeau-Wentworth D, Hardin PE, Emery P. Light and temperature control the contribution of specific DN1 neurons to Drosophila circadian behavior. Curr Biol. 2010b;20:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.