Abstract

Background

Skin antisepsis is a simple and effective measure to prevent infections. The efficacy of chlorhexidine is actively discussed in the literature on skin antisepsis. However, study outcomes due to chlorhexidine-alcohol combinations are often attributed to chlorhexidine alone. Thus, we sought to review the efficacy of chlorhexidine for skin antisepsis and the extent of a possible misinterpretation of evidence.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature review of clinical trials and systematic reviews investigating chlorhexidine compounds for blood culture collection, vascular catheter insertion and surgical skin preparation. We searched PubMed, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website, several clinical trials registries and a manufacturer website. We extracted data on study design, antiseptic composition, and the following outcomes: blood culture contamination, catheter colonisation, catheter-related bloodstream infection and surgical site infection. We conducted meta-analyses of the clinical efficacy of chlorhexidine compounds and reviewed the appropriateness of the authors′ attribution.

Results

In all three application areas and for all outcomes, we found good evidence favouring chlorhexidine-alcohol over aqueous competitors, but not over competitors combined with alcohols. For blood cultures and surgery, we found no evidence supporting chlorhexidine alone. For catheters, we found evidence in support of chlorhexidine alone for preventing catheter colonisation, but not for preventing bloodstream infection. A range of 29 to 43% of articles attributed outcomes solely to chlorhexidine when the combination with alcohol was in fact used. Articles with ambiguous attribution were common (8–35%). Unsubstantiated recommendations for chlorhexidine alone instead of chlorhexidine-alcohol were identified in several practice recommendations and evidence-based guidelines.

Conclusions

Perceived efficacy of chlorhexidine is often in fact based on evidence for the efficacy of the chlorhexidine-alcohol combination. The role of alcohol has frequently been overlooked in evidence assessments. This has broader implications for knowledge translation as well as potential implications for patient safety.

Introduction

Skin antisepsis has been an indispensable part of medical practice for more than a century. After a period of increased attention in the 1970s and 1980s that temporarily waned, there is now renewed interest in its role as a simple and effective measure for preventing healthcare-acquired infections.

The most commonly used substances for skin antisepsis are (1) alcohols (ethanol, isopropanol and n-propanol), (2) chlorhexidine, commonly available as chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG), and (3) povidone-iodine (PVI), an organic iodine complex. Among these antiseptics, alcohols are microbiologically most active but have no appreciable residual activity [1]–[3]. CHG and PVI are less effective, but have residual activity on skin, which is pronounced for CHG but small for PVI. The usual active concentrations are about 70–90% (v/v) for alcohols, 0.5–4% (w/v) for CHG, and 5–10% (w/v) for PVI (or, instead of total PVI, 0.5–1% “available” iodine). Both CHG and PVI are available as aqueous solutions where they are the sole active ingredients, and they can be combined with alcohols, thereby creating enhanced antiseptics with two active components. There is also iodine tincture, which is an alcoholic solution of elemental iodine and potassium iodide.

Among the antiseptics, CHG has attracted considerable attention through several prominent clinical studies concerning vascular catheters and surgery [4]–[6]. CHG became a topic of discussion and a subject of keynote presentations at conferences. Preference for CHG, in particular over its main competitor, PVI, was expressed in several practice recommendations and evidence-based guidelines for skin antisepsis [7]–[10].

We noticed an inconsistent interpretation of findings in some primary studies and subsequent reviews. Several articles that evaluated the efficacy of the combination of alcohols plus CHG attributed the study outcomes solely to the CHG component [11]–[13]. These articles effectively concluded that CHG was the only agent responsible for positive outcomes and that CHG per se was superior to PVI per se when in fact CHG-alcohol versus PVI alone had been tested.

This apparent misinterpretation of evidence and an increasing number of recommendations that were focussing prominently or exclusively on the efficacy of the CHG component prompted us to reassess the evidence by way of systematic review. We posed the following questions: (1) What is the evidence for the efficacy of CHG alone or combination antiseptics containing it for blood culture collection, vascular catheter insertion, and surgical skin preparation? (2) How common is the attribution of efficacy from a combination of antiseptics to CHG alone in the primary literature and in systematic reviews? (3) Has this misattribution had an effect on practice recommendations and evidence-based guidelines?

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

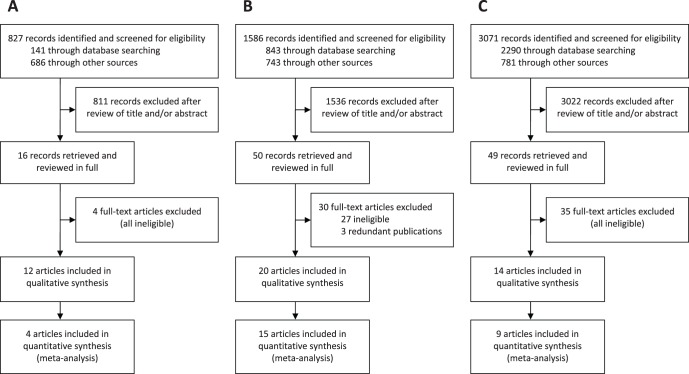

Exhaustive searches for primary and secondary literature were performed in three areas of skin antisepsis: (1) blood culture collection, (2) vascular catheter insertion, and (3) surgical skin preparation. For the purpose of this review, primary literature was defined as randomised clinical trials (RCTs) and non-randomised clinical studies, and secondary literature was defined as systematic reviews. Searches were performed using PubMed, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website, several clinical trials registries, and a CHG product manufacturer’s website (CareFusion, San Diego, CA, USA). Apart from the selection of databases, no specific limits on publication dates and language were applied. The full literature search strategy is provided in Text S1, and a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1. A PRISMA Checklist is provided in Checklist S1.

Figure 1. Flow diagrams of literature search and study selection in three areas of skin antisepsis.

(A) blood culture collection; (B) vascular catheter insertion; (C) surgical skin preparation. Reasons for exclusion at the full-text article stage are provided in Text S1.

Selection Criteria

All included primary and secondary articles had to have evaluated any CHG-containing antiseptic against any other antiseptic in one of the three areas of interest. The following outcomes had to be reported: (1) for blood culture studies, the rate of blood culture contamination, (2) for vascular catheter studies, the rates of microbial catheter colonisation and/or catheter-related bloodstream infection (CR-BSI), and (3) for surgery articles, the rate of surgical site infections. The following interventions were excluded: antiseptic cloth wiping or bathing in the preoperative phase, antisepsis only during catheter maintenance but not at insertion, non-superficial skin antisepsis, and where skin antisepsis was only part of a multifactorial intervention. Further information on eligibility criteria is provided in Text S1.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data were extracted on study design, antiseptics compared and their composition, main outcomes, and the authors’ interpretation of the study results. All primary (RCTs and non-RCTs) and secondary articles were rated to assess the authors’ attribution of study outcomes from CHG-containing antiseptics (qualitative synthesis), while only RCTs were selected for subsequent meta-analyses (quantitative synthesis). All RCTs were appraised for risk of bias using a domain-based approach recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration [14]. Further details and the results of risk of bias assessment are provided in Text S1 and Tables S1, S2 and S3.

Assessment of Authors’ Attribution (Qualitative Synthesis)

Attribution was rated as “correct” if study authors recognised that the combination of both CHG and alcohol was used and therefore responsible for the outcomes. It was rated as “incorrect” if authors clearly attributed study outcomes derived from the combination of CHG and alcohol to CHG alone. It was rated as “intermediate” if there were ambiguous statements, such as when authors recognised the antiseptic properties of alcohols but also made statements suggesting that CHG alone might be responsible. It was rated as “not applicable” if CHG alone without alcohol had been used.

Meta-analyses of Clinical Efficacy (Quantitative Synthesis)

Meta-analyses to quantify the clinical efficacy of CHG compounds were performed using the RevMan software [15] by computing relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Only RCTs that were clinically homogenous and had tested the same basic antiseptic components were pooled together. In the absence of statistical heterogeneity, a fixed-effects model was used for analysis, and in the presence of statistical heterogeneity (I2≥50%; p≤0.1), both fixed-effects and random-effects models were used in a sensitivity analysis.

Survey of Tertiary Literature

The impact of the conclusions in the primary and secondary literature on perceptions in the medical community and on practice recommendations was gleaned from a non-exhaustive survey of the tertiary literature. Tertiary literature was defined as any other articles commenting on the role of CHG in skin antisepsis, including narrative reviews, professional websites and e-mail discussion forums, clinical practice recommendations, and evidence-based guidelines.

Results

Skin Antisepsis for Blood Culture Collection

A total of 12 articles met the inclusion criteria for blood culture collection; this included 10 primary studies [11], [16]–[24] and two systematic reviews [25], [26] (Table 1). Among the primary studies, four were RCTs. All of the articles evaluated CHG-alcohol combinations, none evaluated aqueous CHG.

Table 1. Primary studies and systematic reviews evaluating chlorhexidine-containing antiseptics for the prevention of blood culture contamination.

| Referencea | Study design | Antiseptics comparedb | Main outcomesc | Comments | Attributiond |

| Mimoz et al. 1999 [16] (M, C) | RCT | A: CHG 0.5% + ALC (?%); B: PVI aq 10% | A: 14/1019; B: 34/1022; p<0.05 | Advantage of CHG + ALC over PVI aq | Incorrect |

| Trautner et al. 2002 [17] (M, C) | RCTe | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: IPA 70% seq IT (I2 2%, ETH 47%) | A: 1/215; B: 3/215; NS | Study design equivalent to RCT | Correct |

| Barenfanger et al. 2004 [18] | Non-RCTf | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: IT (composition?) | A: 158/5802; B: 186/5936; NS | Composition of IT could not be clarified | Incorrect |

| Madeo et al. 2008 [19] | Non-RCTf | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: Unknown | A: 40/1870; B: 304/4072; p<0.05 | Weak study design, comparator unknown | Correct |

| McLellan et al. 2008 [20] | Non-RCTf | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: IPA 70% | Complex outcomesg | Weak study design, thoughtful analysis | Correct |

| Stonecypher 2008 [21] | Non-RCTf | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: PVI aq 10% | A: 23/687; B: 37/612; p<0.05 | Alcohol in arm A only revealed by correspondence | Incorrect |

| Suwanpimolkul et al. 2008 [22] (C) | RCT | A: CHG 0.5% + ETH 70%; B: PVI aq 10% | A: 34/1068; B: 74/1078; p<0.05 | Advantage of CHG + ALC over PVI aq | Correct |

| Tepus et al. 2008 [23] | Non-RCTf | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: IPA 70% seq IT (I2 2%, ETH 47%) | A: 169/7606; B: 251/7158; p<0.05 | Confounder: staff training before CHG + IPA study arm | Intermediate |

| Marlowe et al. 2010 [11] | Non-RCTf | A: CHG 3.15% + IPA 70%; B: PVI aq 10% | A: 72/4274; B: 122/4942; p<0.05 | Attribution criticised in letter to the editor | Incorrect |

| Washer et al. 2010 [24] | Cluster-randomised cross-over trial | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: IPA 70% seq PVI aq 10% ; C: IPA 70% seq IT (I2 2%, ETH 50%) | A: 41/4347; B: 25/4261; C: 32/4198; all NS | Use of IPA before PVI and IT in arms B and C, clarified by author | Correct |

| Malani et al. 2007 [25] | Systematic review | 4 eligible trials, 2 with CHG-containing antiseptics | No clear evidence; possible benefits from packaged kits and alcohol-based antiseptics | Results overall inconclusive | Correct |

| Caldeira et al. 2011 [26] | Systematic review | 6 eligible trials, 3 with CHG-containing antiseptics | Alcoholic products > non-alcoholic ones; ALC + CHG > PVI aq; CHG compounds vs iodine compounds inconclusive; ALC alone not inferior to iodine products | Article appropriately analyses different ingredients and compositions of antiseptics | Correct |

ALC, alcohol (when alcohol type not known); aq, aqueous; CHG, chlorhexidine gluconate; ETH, ethanol; IPA, isopropanol; IT, iodine tincture; PVI, povidone iodine; RCT, randomised clinical trial; seq, sequential application; vs, versus; ?%, percentage not specified; > (in systematic reviews), performing better than.

Annotation with (M) or (C) denotes whether original studies were included in the systematic reviews of Malani et al [25] (M) or Caldeira et al [26] (C).

A, B, and C denote different study arms.

Outcome: number of contaminated blood cultures per cultures obtained in each study arm. Significance is indicated either by NS (not significant) or p<0.05 (when significant).

Attribution: assesses whether study outcomes derived from alcohol plus CHG were attributed to CHG alone by authors.

In this trial, all subjects received both antiseptics at the same time, outcomes were assessed blindly.

These studies were classified as non-randomised cluster cross-over trials. Some had been conducted by prospective sequential implementation of different antiseptic regimens in clinical units [18], [20], [21], some by retrospective comparison of antiseptic regimens [11], [19], [23].

This study had complex outcomes from several pre- and post-intervention intervals showing that rigorous training and application may be more important than the choice of antiseptic.

Correct attribution was found in seven articles (58%), ambiguous statements (intermediate ranking) in one (8%), and incorrect attribution in four (33%). Among the ones with incorrect attribution, three noted the presence of alcohol in the CHG-containing preparation but did not associate it with the efficacy of the antiseptic, while one published abstract listed and discussed CHG alone, and the presence of alcohol was found out through correspondence. Both systematic reviews recognised the importance of alcohols.

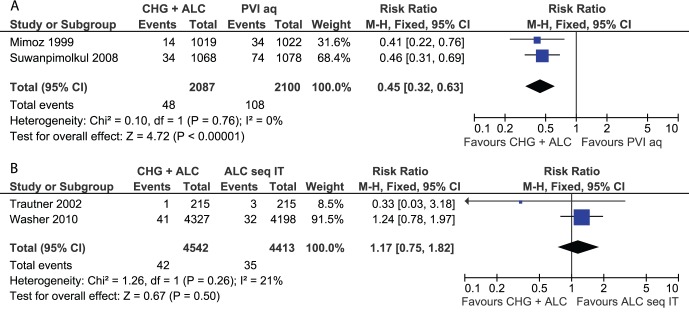

Two parallel-group RCTs 16,22, one within-subject trial with each subject experiencing both interventions [17] and a cluster-randomised cross-over trial [24] were subjected to meta-analyses (Figure 2). The results showed that the combination of CHG plus alcohol was significantly better than aqueous PVI alone (RR: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.32–0.63) and that there was no significant difference between CHG-alcohol versus sequential isopropanol and iodine tincture (RR: 1.17; 95% CI: 0.75–1.82). A single comparison of CHG-alcohol versus sequential isopropanol and PVI [24] also showed no significant difference (RR: 1.61; 95% CI: 0.98–2.64). The results of the non-RCTs are listed in Table 1 but were not included in meta-analyses.

Figure 2. Meta-analyses of skin antiseptics for the prevention of blood culture contamination.

(A) CHG plus alcohol versus aqueous PVI. (B) CHG plus alcohol versus sequential alcohol followed by iodine tincture. References and abbreviations are as provided in Table 1.

The Malani et al systematic review [25] included four trials, two examining CHG-containing antiseptics. The authors found no clear evidence favouring any particular type of antiseptic, however, they identified possible benefits from prepackaged kits and alcohol-containing antiseptics. The Caldeira et al review [26] included six trials, three examining CHG-containing antiseptics. Several conclusions were made: (1) alcoholic iodine tincture was better than aqueous PVI, (2) alcoholic CHG was better than aqueous PVI, (3) alcoholic products were better than non-alcoholic ones, and (4) alcohol alone was not inferior to any iodine products. The authors commented that alcohol alone may be sufficient.

We identified several tertiary sources that contained unsubstantiated statements concerning the efficacy of CHG. A Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guideline for blood culture collection [7] stated: “chlorhexidine gluconate [without reference to the presence of alcohol]... is the recommended skin disinfectant for older infants, children, and adults”. A standard textbook on phlebotomy [27] contained similar statements. Several contributions to the discussion forum ClinMicroNet (American Society for Microbiology) discussed “chlorhexidine” (without reference to alcohols) and its benefits for blood culture collection.

In contrast, we did not find any relevant evidence supporting the use of CHG alone prior to blood culture collection.

Skin Antisepsis for Vascular Catheter Insertion

A total of 20 articles met the inclusion criteria for vascular catheter insertion; this included 18 primary studies [28]–[45] and two systematic reviews [46], [47] (Table 2). Among the primary studies, 15 were RCTs. Four studies evaluated aqueous CHG, 13 evaluated CHG-alcohol combinations, and two evaluated a triple combination of CHG, benzalkonium chloride and benzyl alcohol. There were four studies with three study arms.

Table 2. Primary studies and systematic reviews evaluating chlorhexidine-containing antiseptics for the prevention of intravascular catheter-associated infections.

| Referencea | Study designb | Antiseptics comparedc | Outcomes catheter colonisationd | Outcomes CR-BSId | Comments | Attributione |

| Maki et al. 1991 [28] (C) | RCT; CVCs, ACs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG aq 2%; B: PVI aq 10%; C: IPA 70% | A: 5/214; B: 21/227; C: 11/227; only A:B p<0.05 | A: 1/214; B: 6/227; C: 3/227; all NS | Seminal study; only arms A vs B in colonisation significant | Not applicable |

| Sheehan et al. 1993 [29] (C) | RCT; CVCs, ACs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG aq 2%; B: PVI aq 10% | A: 3/169; B: 12/177; p<0.05 | A: 1/169; B: 1/177; NS | Conference abstract; colonisation significant | Not applicable |

| Garland et al. 1995 [30] | Non-RCT; PVCs; only insertion, not maintenancef | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: PVI aq 10% | A: 20/418; B: 38/408; p<0.05 | A: 2/418; B: 0/408; NS | Only colonisation significant | Incorrect |

| Meffre et al. 1996 [31] (C) | RCT; PVCs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG 0.5% + ALC (?%); B: PVI aq 10% | A: 9/568; B: 22/549; p<0.05 | A: 3/568; B: 3/549; NS | Conference abstract; colonisation significant | Correct |

| Mimoz et al. 1996 [32] (C) | RCT; CVCs, ACs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG 0.25% + BAK 0.025% + BALC 4%; B: PVI aq 10% | A: 12/170; B: 24/145; p<0.05 | A: 3/170; B: 3/145; NS | Synergistic combination of three antiseptics in arm A | Correct |

| Legras et al. 1997 [33] (C) | RCT; CVCs, ACs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG 0.5% + ALC (?%); B: PVI aq 10% | A: 19/179; B: 31/224; NS | A: 0/208; B: 4/249; NS | Differences non-significant | Intermediate |

| Cobbett and LeBlanc 2000 [34] (C) | RCT; PVCs; insertion yes, maintenance not specified | A: CHG 0.5% + IPA 70%; B: ALC (?%) seq PVI aq 10%; C: PVI aq 10% seq ALC (?%) | A: 6/83; B: 12/80; C: 11/81; All NS | ND | Differences non-significant, also when B and C pooled vs A | Correct |

| Humar et al. 2000 [35] (C) | RCT; CVCs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG 0.5% + ALC (?%); B: PVI aq 10% | A: 36/116; B: 27/116; NS | A: 4/193; B: 5/181; NS | Differences non-significant; sole study with slight disadvantage of CHG + ALC vs PVI aq | Intermediate |

| Maki et al. 2001 [36] (C) | RCT; CVCs, PICCs, ACs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG 1% + ALC 75%; B: PVI aq 10% | A: 43/422; B: 192/617; p<0.05 | A: 4/422; B: 23/617; p<0.05 | Largest study; biggest difference between study arms | Intermediate |

| Langgartner et al. 2004 [37] (R) | RCT; CVCs; insertion was studied; maintenance all with CHG + ALC | A: CHG 0.5% + IPA 70%; B: PVI aq 10%; C: CHG 0.5% + IPA 70% seq PVI aq 10% | A: 11/45; B: 16/52; C: 2/43; A:C, B:C p<0.05 | ND | Arm C (sequential protocol) significantly better than A or B | Correct |

| Astle and Jensen 2005 [38] (R) | RCT; CVCs (hemodialysis); insertion and maintenance | A: CHG 0.5% + IPA 70%; B: ExSept | ND | A: 1/64; B: 1/57; NS | Study did not report catheter colonisation | Incorrect |

| Kelly et al. 2005 [39] | RCT; CVCs, ACs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: PVI aq 10% | A: 4/82; B: 15/82; p<0.05 | A: 1/82; B: 8/82; p<0.05 | Conference abstract; alcohol in arm A only revealed by correspondence | Incorrect |

| Balamongkhon et al. 2007 [40] | Non-RCT; insertion and maintenancef | A: CHG 2% + ETH 70%; B: PVI aq 10% | ND | A: 3/120; B: 7/192; NS | Weak study design, difference non-significant | Intermediate |

| Mimoz et al. 2007 [41] (R) | RCT; CVCs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG 0.25% + BAK 0.025% + BALC 4%; B: PVI 5% + ETH 70% | A: 28/242; B: 53/239; p<0.05 | A: 4/242; B: 10/239; NS | Rare study with PVI-alcohol; difference for colonisation significant | Intermediate |

| Small et al. 2008 [42] (R) | RCT; PVCs; only insertion, not maintenance | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: IPA 70% | A: 18/91; B: 39/79; p<0.05 | ND | Significant difference; but mean colony counts lower in IPA alone group | Correct |

| Vallés et al. 2008 [43] (R) | RCT; CVCs, ACs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG 2% + ALC (?%); B: CHG 2% aq; C: PVI aq 10% | A: 34/226; B: 38/211; C: 48/194; only A:C p<0.05 | A: 9/226; B: 9/211; C: 9/194; all NS | Only difference in arms A vs C in colonisation significant | Correct |

| Garland et al. 2009 [44] | RCT; PICCs; insertion and maintenance | A: CHG 0.5% + ALC (?%); B: PVI aq 10% | A: 3/24; B: 1/24; NS | A: 0/24; B: 0/24; NS | Small study; focus on skin tolerability in neonates | Incorrect |

| Ishizuka et al. 2009 [45] | Non-RCT; CVCs; insertion studied; maintenance all PVI aqf | A: CHG aq 0.05%; B: PVI aq 10% | ND | A: 14/286; B: 6/298; NS | CHG concentration very unusually low | Not applicable |

| Chaiyakunapruk et al. 2002 [46] | Systematic review | 8 eligible trials, 2 with CHG aq, 1 with CHG plus other compounds, 5 with CHG + ALC; comparator for all PVI aq 10% | Relative risk for CHG-containing vs PVI aq was about 0.5 (50%) for colonisation and CR-BSI | See comments under colonisation | Seminal review; basis for multiple recommendations; only CHG + ALC but not CHG aq significant in CR-BSI | Incorrect |

| Rickard and Ray-Barruel 2010 [47] | Systematic review | 7 eligible trials, 5 examined any CHG-containing antiseptic prior to catheter insertion | Any CHG vs any others performed significantly better in colonisation but not in CR-BSI; same for any CHG vs any PVI | See comments under colonisation | Article available on internet; part of Australian national infection control guidelines | Intermediate |

ACs, arterial catheters; ALC, alcohol (when alcohol type not known); aq, aqueous; BAK, benzalkonium chloride; BALC, benzyl alcohol; CHG, chlorhexidine gluconate; CR-BSI, catheter-related bloodstream infection; CVCs, central venous catheters; ETH, ethanol; IPA, isopropanol; ND, not determined; PICCs, peripherally inserted central venous catheters; PVCs, peripheral venous catheters; PVI, povidone iodine; RCT, randomised clinical trial; seq, sequential application; vs, versus; ?%, percentage not specified.

Annotation with (C) or (R) denotes whether original studies were included in the systematic reviews of Chaiyakunapruk et al [46] (C) or Rickard and Ray-Barruel [47] (R).

Mention of insertion and maintenance refers to whether the assigned study antiseptic was used prior to catheter insertion only, or both, for insertion and maintenance.

A, B, and C denote different study arms.

Outcome: number of catheters colonised or CR-BSIs per catheters inserted in each study arm. Significance is indicated either by NS (not significant) or p<0.05 (when significant).

Attribution: assesses whether study outcomes derived from alcohol plus CHG were attributed to CHG alone by authors.

These studies were classified as non-randomised cluster cross-over trials. They had been conducted by prospective sequential implementation of different antiseptic regimens in clinical units.

Judgement of attribution was not applicable to three studies, as they used aqueous CHG only. Among the remaining 17 articles, correct attribution was found in six articles (35%), ambiguous statements (intermediate ranking) in another six articles (35%), and incorrect attribution in five articles (29%). Three original articles correctly listed the presence of alcohol but did not associate it with antiseptic efficacy, while for one abstract, the presence of alcohol was found out through correspondence.

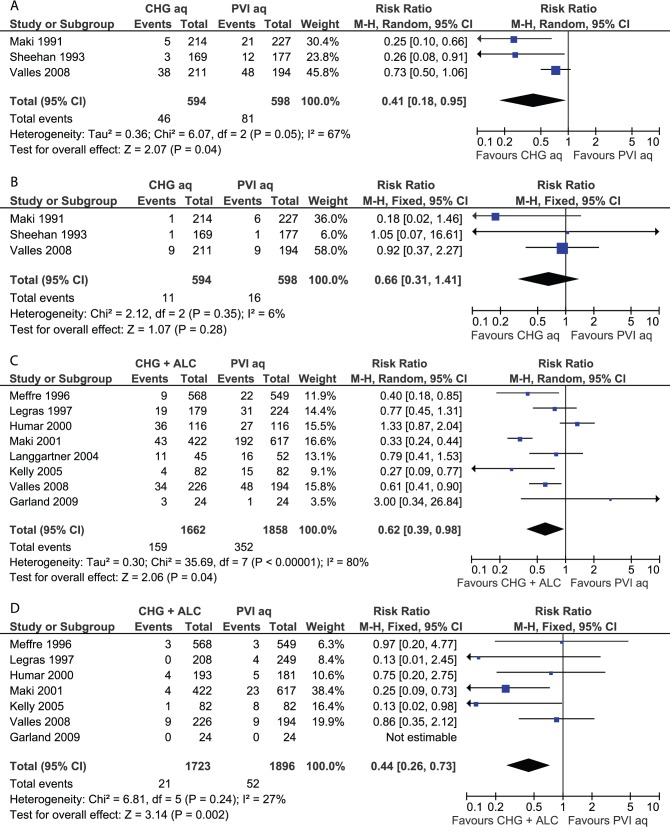

Four meta-analyses were performed (Figure 3); this included two analyses (catheter colonisation and CR-BSI) on aqueous CHG versus aqueous PVI (3 trials each) and two analyses on CHG-alcohol versus aqueous PVI (7 and 8 trials, respectively). The comparison of aqueous CHG with aqueous PVI indicated a significantly lower risk of catheter colonisation in the CHG group (RR 0.41; 95% CI: 0.18–0.95), but lacked significance for CR-BSI (RR 0.66; 95% CI: 0.31–1.41). The comparison of CHG-alcohol with PVI alone indicated significant benefits for CHG plus alcohol for both catheter colonisation (RR 0.62; 95% CI: 0.39–0.98) and CR-BSI (RR 0.44; 95% CI: 0.26–0.73). Statistical heterogeneity was detected in both groupings for the outcome of catheter colonisation. For aqueous CHG versus aqueous PVI (Figure 3A), the source of heterogeneity appeared to be the trial of Vallés et al [43], for CHG-alcohol versus aqueous PVI (Figure 3C), potential sources were the trials of Humar et al [35] and Maki et al [36].

Figure 3. Meta-analyses of skin antiseptics for the prevention of vascular catheter-related infection.

(A) Aqueous CHG versus aqueous PVI, outcome catheter colonisation. (B) Aqueous CHG versus aqueous PVI, outcome catheter-related bloodstream infection. (C) CHG plus alcohol versus aqueous PVI, outcome catheter colonisation. (D) CHG plus alcohol versus aqueous PVI, outcome catheter-related bloodstream infection. References and abbreviations are as provided in Table 2.

Additional single-trial comparisons included (1) the combination of CHG, benzalkonium chloride and benzyl alcohol versus aqueous PVI [32], showing a benefit for the CHG preparation for catheter colonisation (RR 0.43; 95% CI: 0.22–0.82) but not for CR-BSI (RR 0.85; 95% CI: 0.17–4.16), (2) the same combination versus PVI plus alcohol [41], showing a benefit for the CHG preparation for colonisation (RR 0.52; 95% CI: 0.34–0.80) but not CR-BSI (RR 0.40; 95% CI: 0.13–1.24), and (3) a trial of CHG-alcohol versus sequential alcohol and aqueous PVI [34] being insignificant for colonisation (RR 0.51; 95% CI: 0.21–1.19). Again, the results of the non-RCTs are listed individually in Table 2 but were not included in meta-analyses.

The first systematic review [46] included eight trials, two examining 2% aqueous CHG, one a triple combination with CHG, and five examining CHG-alcohol combinations. The comparator for all was 10% aqueous PVI. The authors pooled all studies and found a significant risk reduction for colonisation and CR-BSI in the CHG-containing group. However, all study outcomes were solely attributed to CHG. Only a brief passage in the Discussion mentioned that only the subset of studies testing alcoholic CHG had produced a significant reduction in CR-BSI, but not the ones testing aqueous CHG. It was concluded that this may have been due to inadequate statistical power from the smaller number of studies with aqueous CHG. The second systematic review [47] included seven trials, five examining CHG-containing antiseptics against different competitors. It compared both aqueous CHG and CHG-alcohol combinations versus different antiseptics in a non-CHG group. It found a benefit of CHG-containing solutions for preventing device colonisation.

Again, we found several examples in the tertiary literature that referred to CHG alone where the CHG-alcohol combination would have been relevant. A follow-up article [48] on the 2002 systematic review of Chaiyakunapruk et al [48] examined the clinical and economic benefits of CHG for vascular catheter site care. It commented on the benefits of CHG in preventing CR-BSI, even though that had only been demonstrated for the CHG-alcohol combination. A seminal article on the Keystone Project [4] that described evidence-based procedures to decrease CR-BSIs in 108 intensive care units mentioned skin preparation with “chlorhexidine” without referring to alcohol. In fact, almost all units had used a CHG-alcohol combination from one company (CareFusion, correspondence). Both the 2002 Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines for intravascular catheters [8] and the draft of the 2011 guidelines [9] recommended preparing the skin with a 2% chlorhexidine-based preparation for central venous catheters. This was classified as Category IA evidence. The draft was followed by a public comment phase, and the final 2011 guideline [49] recommended a >0.5% chlorhexidine skin preparation with alcohol. The final guideline also stated that the relative efficacy of CHG-alcohol versus PVI-alcohol was unresolved.

Overall, we found strong evidence supporting the efficacy of CHG-alcohol antisepsis for catheter insertion and maintenance, particularly when compared with aqueous PVI. We also found evidence favouring aqueous CHG over aqueous PVI, but this was limited to the outcome catheter colonisation. In single trials, a CHG-containing triple combination was better than PVI-alcohol [41], and CHG-alcohol was better than alcohol alone [42], both in terms of catheter colonisation.

Skin Antisepsis before Surgery

A total of 14 articles met the inclusion criteria for surgical skin antisepsis; this included 11 primary studies [6], [50]–[59] and three systematic reviews [12], [13], [60] (Table 3). Among the primary studies, 9 were RCTs. All primary articles evaluated CHG-alcohol combinations, none aqueous CHG.

Table 3. Primary studies and systematic reviews evaluating chlorhexidine-containing antiseptics for the prevention of surgical site infections.

| Referencea | Study design | Antiseptics comparedb | Main outcomesc | Comments | Attributiond |

| Berry et al. 1982 [50] (E, L, N) | RCT; mixed surgery, including abdominal | A: CHG 0.5% + ALC (?%); B: PVI 10% + ALC (?%) | A: 44/453; B: 61/413; p<0.05 | ALC type and content in both study arms unknown; difference significant | Incorrect |

| Brown et al. 1984 [51] (L, N) | RCT; mixed surgery, including obstetric, abdominal | A: CHG 0.5% + IPA 70%; B: PVI aq (0.7% av I2) seq PVI aq (?%) | A: 23/378; B: 29/359; NS | Difference non-significant | Incorrect |

| Ostrander et al. 2005 [52] (L) | RCT; clean foot and ankle surgery | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: IPOV (0.7% av I2) + IPA 74%; C: Chloroxylenol 3% | A: 1/40; B: 0/40; C: 2/40; all NS | Also skin microbial counts studied, but methodology not adequately described | Intermediate |

| Veiga et al. 2008 [53] (L) | RCT; elective clean plastic surgery | A: CHG 0.5% + ALC (?%); B: PVI 10% + ALC (?%) | A: 0/125; B: 4/125; NS | Difference non-significant; ALC type and content unknown | Incorrect |

| Cheng et al. 2009 [54] | RCT; clean forefoot surgery | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: PVI 10% + IPA 23% | A: 0/25; B: 0/25; NS | Small study; focus on skin counts; IPA content in arm B far below active range | Intermediate |

| Paocharoen et al. 2009 [55] (L, N) | RCT; general surgery, including clean, clean-contaminated and contaminated cases | A: CHG 4% + IPA 70%; B: PVI aq (?%) | A: 5/250; B: 8/250; NS | Difference non-significant | Incorrect |

| Saltzman et al. 2009 [56] (L) | RCT; clean shoulder surgery, including arthroscopic | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: IPOV (0.7% av I2) + IPA 74%; C: PVI aq scrub & paint (0.75% & 1.0% av I2) | A: 0/50; B: 0/50; C: 0/50; NS | Small study; focus on skin counts; microbiological methods potentially inadequate | Correct |

| Swenson et al. 2009 [57] (N) | Non-RCT; mixed general surgerye | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: PVI aq 7.5% seq IPA 70% seq PVI aq 10%; C: IPOV (0.7% av I2) + IPA 74% | A: 68/827; B: 72/1514; C: 38/794; A:B, A:C p<0.05 | Significantly more infections in CHG + ALC arm, but only superficial ones | Correct |

| Darouiche et al. 2010 [6] (L, N) | RCT; mixed clean-contaminated surgery, including abdominal | A: CHG 2% + IPA 70%; B: PVI aq 10% scrub & paint | A: 39/409; B: 71/440; p<0.05 | Seminal study; significant difference in favour of CHG + ALC over PVI aq | Correct |

| Sistla et al. 2010 [58] | RCT; elective clean inguinal hernia surgery | A: CHG 2.5% + ETH 70%; B: PVI aq 10% | A: 14/200; B: 19/200; NS | Difference non-significant | Correct |

| Levin et al. 2011 [59] | Non-RCT; elective gynaecological laparotomy surgerye | A: CHG aq 2% seq IPA 70%; B: PVI aq 10% seq PVI 10% + ETH 65% | A: 5/111; B: 21/145; p<0.05 | Weak study design; significant difference | Correct |

| Edwards et al. 2004 [60] | Systematic review | 7 eligible trials, only 1 with a CHG-containing arm [50] | Overall inconclusive due to lack of well-designed studies | Review from 2004, updated 2009; lack of studies at the time | Intermediate |

| Lee et al. 2010 [12] | Systematic review | 9 eligible trials, 5 studied CHG + ALC vs PVI aq, 4 studied CHG + ALC vs PVI + ALC (including 1 both), 1 studied CHG aq vs PVI aq for mucous membranes | “Chlorhexidine” superior to iodine, based on majority CHG + ALC vs PVI aq outcomes | Analysed both infection rates and microbial skin counts; criticised in letters to the editor | Incorrect |

| Noorani et al. 2010 [13] | Systematic review | 6 eligible trials, 3 studied CHG + ALC vs PVI aq, 2 CHG + ALC vs PVI + ALC, 1 CHG aq vs PVI aq for mucous membranes | “Chlorhexidine” superior to iodine, based on majority CHG + ALC vs PVI aq outcomes | Attribution criticised in letters to the editor | Incorrect |

ALC, alcohol (when alcohol type not known); aq, aqueous; av, available (referring to available iodine as opposed to total iodine complex); CHG, chlorhexidine gluconate; ETH, ethanol; IPA, isopropanol; IPOV, iodine povacrylex; PVI, povidone iodine; RCT, randomised clinical trial; seq, sequential application; vs, versus; ?%, percentage not specified.

Annotation with (E), (L), or (C) denotes whether original studies were included in the systematic reviews of Edwards et al [60] (E), Lee et al [12] (L), or Noorani et al [13] (N).

A, B, and C denote different study arms.

Outcome: surgical site infections per number of surgical procedures in each study arm. Significance is indicated either by NS (not significant) or p<0.05 (when significant).

Attribution: assesses whether study outcomes derived from alcohol plus CHG were attributed to CHG alone by authors.

Among all primary and secondary articles, correct attribution to both CHG and alcohol was found in five articles (36%), ambiguous statements (intermediate ranking) in three articles (21%), and incorrect attribution in six articles (43%).

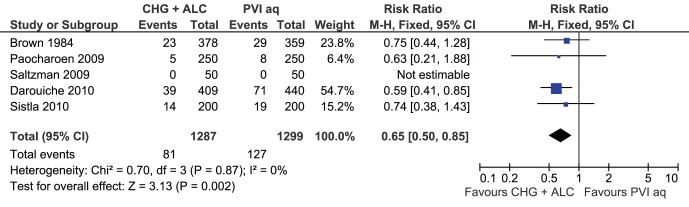

Five RCTs evaluated CHG-alcohol versus aqueous PVI and were included in a meta-analysis (Figure 4). This showed a significant advantage of CHG-alcohol in reducing surgical site infections (RR 0.65; 95% CI: 0.50–0.85). The remaining RCTs evaluated various CHG-alcohol against various iodine-alcohol combinations, but these studies were very heterogeneous. For two larger trials [50], [53], the types and concentrations of alcohol could not be clarified. Two smaller trials [52], [56] had satisfactory alcohol concentrations but had few outcomes only, and one trial [54] used an alcohol concentration (23%) far below the antimicrobially active range in the PVI-containing arm. Given that different alcohol types and concentrations can easily tip the efficacy in favour of one or another preparation [61], we elected not to perform additional meta-analyses. Again, the non-RCT studies are listed in Table 3 but were not included in meta-analyses.

Figure 4. Meta-analysis of skin antiseptics for the prevention of surgical site infection.

CHG plus alcohol versus aqueous PVI. References and abbreviations are as provided in Table 3.

The first systematic review [60] included 7 trials, of which only one had a CHG-containing arm. It concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support a particular antiseptic over another. Another systematic review [12] included 9 trials comparing CHG-containing versus iodine-containing antiseptics. The authors examined two outcomes, surgical site infections and microbial skin cultures. The majority of studies (5 trials) compared CHG-alcohol with aqueous PVI. The authors pooled all CHG-containing versus all iodine-containing trials – without accounting for other ingredients – and found a significant risk reduction for both outcomes in favour of the CHG-containing preparations. The conclusion was that skin antisepsis with CHG is more effective than with iodine. We further examined the included articles that assessed microbial skin cultures and found that none reported whether neutralisers were used in the testing. However, suitable neutralisers are essential for antimicrobial efficacy assessment [62], [63]. The third systematic review [13] examined six trials; the authors pooled any CHG-containing versus any PVI-containing antiseptics without accounting for other ingredients and concluded that CHG per se was superior to povidone-iodine per se.

Again, we found examples of tertiary publications that contained unsubstantiated statements about the role of CHG. A narrative Current Concepts review on the prevention of perioperative infection [64] concluded: “chlorhexidine gluconate is superior to povidone-iodine for preoperative antisepsis”. A surgical care initiative by Washington State hospitals [65] announced that it would mandate that skin preparation should be done with “chlorhexidine”, citing the study of Darouiche et al [6]. The 2010 national Australian infection control guidelines [10] state that “chlorhexidine” (without reference to alcohol) should preferably be used for skin preparation in surgery. The UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued a public review proposal for its surgical guidelines [66], citing new evidence of benefits of CHG over PVI for surgical skin preparation.

As for blood cultures, we did not find any relevant evidence supporting CHG alone for pre-incisional preparation of superficial skin in surgery. In fact, aqueous CHG commonly fails US regulatory requirements for patient preoperative skin preparation [67], [68].

Discussion

We found a high proportion of primary and secondary literature and some prominent tertiary sources that attributed the efficacy of the combination of CHG and alcohol to CHG alone. The rates of incorrect attribution among the articles that we assessed ranged from 29% for catheters to 43% for surgery. The rates of incorrect and ambiguous attribution combined ranged from 42% for blood cultures to 65% for catheters. For surgery, there were more articles with incorrect (43%) than with correct attribution (36%). These conclusions were found at all levels of evidence gathering and knowledge translation, including primary clinical trials, systematic reviews, clinical practice recommendations and evidence-based guidelines.

The omission of alcohols in the process of evidence assessment can be seen, for example, in the draft CDC catheter guidelines [9] which initially recommended CHG alone for central venous catheter insertion and maintenance. This was subsequently changed to CHG-alcohol in the final guidelines [49]. We are unaware of the sequence of events, but assume that the change may have come through external submissions during the public comment phase. This change effectively rectified the section on skin antisepsis in the final guidelines. Another area of impact is a potentially mistaken rejection of alternatives or competitor products on the basis that they do not contain CHG, even if they have not been sufficiently tested in clinical trials. This appears to be affecting PVI plus alcohol in surgery, by way of negative implication [10], [12], [13], [65], [66].

In our analyses, we found good evidence favouring CHG-alcohol combinations over aqueous PVI, the most commonly tested alternative, in all three areas of skin antisepsis. This is a comparison of two active agents against one. However, this superiority does not hold against PVI plus alcohol or other competitors combined with alcohol, either due to equivalent performance in meta-analyses (for blood cultures) or a lack of relevant studies (for catheters and surgery). For blood cultures, alcohols alone may be effective, according to another analysis [26]. For surgery, the question of CHG-alcohol versus iodine-alcohol is unresolved. For both blood cultures and surgery, we found no evidence that CHG alone is effective. For vascular catheters, the situation is more complex. There is evidence that CHG alone is superior to PVI alone for preventing colonisation, but its effect did not reach significance for CR-BSI. In contrast, CHG-alcohol was superior to PVI alone for both outcomes, colonisation and CR-BSI.

Each of the three applications has different biological and functional requirements. Blood culture collection requires immediate activity at the venipuncture site, but no prolonged action. Alcohols, with their strong immediate activity that typically exceeds those of CHG and PVI by about a factor of 10 [1], [2], [61], fulfill this requirement well. Surgery requires significant immediate activity before incision and some persistent activity during the operation for several hours. Thus, surgical skin preparation is expected to benefit from the immediate action of alcohols plus persistent or enhanced activity from added CHG or PVI [67], [69]. Vascular catheter sites also require good immediate activity before insertion, but since catheters often stay in place for a week or more, good persistent action is also required. This requirement is fulfilled well by CHG [1], [2], [67].

Another fact deserves consideration. Most catheter studies used the antiseptics both before insertion and during maintenance (Table 2). Thus, when viewed strictly, it is not known exactly from the study results whether the antiseptics were more effective at the point of insertion or during maintenance, and which component would be better suited to which phase.

Our review has several limitations. First, it is partially hypothesis-driven, as indicated at the end of the Introduction section. This is unusual for systematic reviews, but nevertheless we used an explicit and rigorous systematic review methodology, including adherence to the PRISMA Statement [70]. Second, our assessment of authors’ attribution is partially based on subjective judgement. This judgement was straightforward in virtually all articles classified as “incorrect”. We tried to err on the side of caution and assigned all articles in which this was less clear to the “intermediate” category. Third, since our search and assessment strategy focussed on any chlorhexidine-containing versus any other antiseptics, our review is not comprehensive in terms of capturing relevant comparisons between different non-CHG-based antiseptics in the three areas. Fourth, we faced limitations from heterogeneity in study design, differences in antiseptic compositions, and a lack of other relevant information while performing our analyses. Attribution was assessed for all RCTs, non-RCTs and systematic reviews, because this was not affected by study design. However, only RCTs were included in meta-analyses, in which only studies with the same basic antiseptic components were pooled together. Nevertheless, due to inherent differences between antiseptic products, we had to retain some variability of antiseptic concentrations and alcohol types in our analyses.

We were unable to trace the exact origins of the CHG misattribution. However – even though this is speculative – some observations in the literature provide a few potential reasons. First, some authors may regard alcohol simply as a solvent for CHG. This is reflected by the commonly-used term “chlorhexidine in alcohol” and references to alcohol as a “base solution” for CHG. Second, alcohol may not be universally regarded as an effective antiseptic. For example, wording in the CLSI blood culture guideline [7] suggests that it is viewed as a cleansing agent at the venipuncture site. Third, some authors may be using the term “chlorhexidine” to actually mean the CHG-alcohol combination. This is suggested by some text passages in the draft CDC catheter guidelines [9]. In any case, this would constitute incorrect usage of the term.

Our findings have broader implications. An important scientific principle – the fact that it is generally not possible to attribute effects to only one factor when several factors have been tested together – has frequently been overlooked. The individual published analyses may have been done correctly at a technical level of evidence assessment [14], but the conclusions appear incorrect. What are possible causes, and what are further implications?

First, it may be a matter of subjective views held by authors. If, for example, alcohol is regarded as a mere solvent for CHG, then authors are unable to draw appropriate conclusions. This means that the assessment of evidence remains susceptible to subjective influences, and this will continue to require attention in this area as well as in other subject areas. Second, this highlights the principle of biological plausibility. In the CHG example, plausibility could have been checked by what is known from microbiological studies of antiseptics [1], [2], [61], [67], [69]; this would have indicated that alcohol is a key component. While biological plausibility is part of the Bradford-Hill Criteria in epidemiological studies [71], there is currently no explicit requirement to address this in clinical trials and systematic reviews [14], [72]. However, we think this should become a requirement.

Our findings also have potential implications for patient safety. When following recommendations to use “chlorhexidine”, caregivers may inappropriately use CHG on its own, in aqueous solution, as this is readily available. The clinical impact from blood cultures and vascular catheterisation may be small, because contaminated blood cultures do not directly harm patients and CHG alone appears to exert some protective effect in vascular catheterisation. However, tangible negative consequences may arise in surgery, because marked differences in surgical infection rates have been observed between different antiseptic regimens [6], [57]. Conversely, if caregivers are unaware of the presence and significance of alcohols, they might accidentally use alcohol compounds for antisepsis on mucous membranes, where they are contraindicated.

In summary, there is good evidence that CHG-alcohol is superior to aqueous PVI – an important competitor – in all three areas of skin antisepsis. However, this does not apply to competitors combined with alcohols. The perceived efficacy of CHG in skin antisepsis is often in fact based on evidence for the efficacy of the CHG-alcohol combination. In conjunction, the role of alcohol has frequently been overlooked in evidence assessments. This has broader implications for knowledge translation as well as potential implications for patient safety.

Supporting Information

Results of risk of bias assessment for studies evaluating antiseptics for blood culture collection.

(PDF)

Results of risk of bias assessment for studies evaluating antiseptics for vascular catheter insertion.

(PDF)

Results of risk of bias assessment for studies evaluating antiseptics for surgical skin preparation.

(PDF)

Eligibility criteria, literature search strategy and risk of bias assessment.

(PDF)

PRISMA Checklist.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We like to thank Andreas F. Widmer (University of Basel, Switzerland) and Manfred L. Rotter (University of Vienna, Austria) for useful information in the planning phase of the article and for helpful comments on the manuscript, Trevor N. Petney (University of Karlsruhe, Germany) for advice in statistical matters, Dianne T. Bautista (Singapore Clinical Research Institute) for additional information concerning the systematic review process, Peggy B. Y. Fong (KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore) for help and advice in the process of literature searching, and all article authors who provided additional information for doing so.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1. Larson E (1988) Guideline for use of topical antimicrobial agents. Am J Infect Control 16: 253–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotter ML (1997) Hand washing, hand disinfection, and skin disinfection. In: Wenzel RP, editor. Prevention and control of nosocomial infections. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams &Wilkins. 691–709.

- 3. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR (1999) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (1999) Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 20: 250–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, Sinopoli D, Chu H, et al. (2006) An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 355: 2725–2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bode LG, Kluytmans JA, Wertheim HF, Bogaers D, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, et al. (2010) Preventing surgical-site infections in nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus . N Engl J Med 362: 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, Otterson MF, Webb AL, et al. (2010) Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med 362: 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson ML, Mitchell M, Morris AJ, Murray PR, Reimer LG, et al.. (2007) Principles and procedures for blood cultures; approved guideline. CLSI document M47-A. Vol. 27 No. 17. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

- 8. O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP, Gerberding JL, Heard SO, et al. (2002) Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. MMWR Recomm Rep 51 (RR-10): 1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, et al. (2009) Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections (public draft). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/ncpdcid/pdf/Draft_BSI_guideline_v15_2FR.pdf. Accessed 3 Feb 2012.

- 10.National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (2010) Australian guidelines for the prevention and control of infection in healthcare. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Available: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/cd33. Accessed 3 Feb 2012.

- 11. Marlowe L, Mistry RD, Coffin S, Leckerman KH, McGowan KL, et al. (2010) Blood culture contamination rates after skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone-iodine in a pediatric emergency department. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 31: 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee I, Agarwal RK, Lee BY, Fishman NO, Umscheid CA (2010) Systematic review and cost analysis comparing use of chlorhexidine with use of iodine for preoperative skin antisepsis to prevent surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 31: 1219–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Noorani A, Rabey N, Walsh SR, Davies RJ (2010) Systematic review and meta-analysis of preoperative antisepsis with chlorhexidine versus povidone-iodine in clean-contaminated surgery. Br J Surg 97: 1614–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Green S (2008) Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- 15.Nordic Cochrane Centre (2011) Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration.

- 16. Mimoz O, Karim A, Mercat A, Cosseron M, Falissard B, et al. (1999) Chlorhexidine compared with povidone-iodine as skin preparation before blood culture. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 131: 834–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trautner BW, Clarridge JE, Darouiche RO (2002) Skin antisepsis kits containing alcohol and chlorhexidine gluconate or tincture of iodine are associated with low rates of blood culture contamination. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 23: 397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barenfanger J, Drake C, Lawhorn J, Verhulst SJ (2004) Comparison of chlorhexidine and tincture of iodine for skin antisepsis in preparation for blood sample collection. J Clin Microbiol 42: 2216–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Madeo M, Barlow G (2008) Reducing blood-culture contamination rates by the use of a 2% chlorhexidine solution applicator in acute admission units. J Hosp Infect 69: 307–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McLellan E, Townsend R, Parsons HK (2008) Evaluation of ChloraPrep (2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% isopropyl alcohol) for skin antisepsis in preparation for blood culture collection. J Infect 57: 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stonecypher K (2008) Decreasing blood culture contamination: chlorhexidine vs. povidone-iodine [abstract]. Southern Nursing Research Society 2008 Annual Conference, Birmingham, AL, USA. South Online J Nurs Res 8 (4): 12. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Suwanpimolkul G, Pongkumpai M, Suankratay C (2008) A randomized trial of 2% chlorhexidine tincture compared with 10% aqueous povidone-iodine for venipuncture site disinfection: Effects on blood culture contamination rates. J Infect 56: 354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tepus D, Fleming E, Cox S, Hazelett S, Kropp D (2008) Effectiveness of Chloraprep in reduction of blood culture contamination rates in emergency department. J Nurs Care Qual 23: 272–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Washer L, Chenoweth C, Kim HW, Malani A, Riddell J, et al.. (2010) Blood culture contamination: a cluster-randomized cross-over trial evaluating the comparative effectiveness of three skin antiseptic interventions [abstract]. Abstract 394. Fifth Decennial International Conference on Healthcare-Associated Infections; 18–22 March 2010; Atlanta, GA, USA.

- 25. Malani A, Trimble K, Parekh V, Chenoweth C, Kaufman S, et al. (2007) Review of clinical trials of skin antiseptic agents used to reduce blood culture contamination. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 28: 892–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Caldeira D, David C, Sampaio C (2011) Skin antiseptics in venous puncture-site disinfection for prevention of blood culture contamination: systematic review with meta-analysis. J Hosp Infect 77: 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCall RE, Tankersley CM (2008) Phlebotomy essentials. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- 28. Maki DG, Ringer M, Alvarado CJ (1991) Prospective randomised trial of povidone-iodine, alcohol, and chlorhexidine for prevention of infection associated with central venous and arterial catheters. Lancet 338: 339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheehan G, Leicht K, O’Brien M, Taylor G, Rennie R (1993) Chlorhexidine versus povidone-iodine as cutaneous antisepsis for prevention of vascular-catheter infection [abstract]. Abstract 1616. In: Program and Abstracts - Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; 17–20 October 1993; New Orleans, LA, USA; American Society for Microbiology. p. 414.

- 30. Garland JS, Buck RK, Maloney P, Durkin DM, Toth-Lloyd S, et al. (1995) Comparison of 10% povidone-iodine and 0.5% chlorhexidine gluconate for the prevention of peripheral intravenous catheter colonization in neonates: a prospective trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 14: 510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meffre C, Girard R, Hajjar J, Fabry J (1996) Povidone-iodine vs. alcoholic chlorhexidine for disinfection of the insertion site of peripheral venous catheters: results of a multicenter randomized trial [abstract]. Abstract 64. In: Proceedings and abstracts of the 6th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Washington, DC, USA. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 17 (No 5 Suppl Part 2): 26. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mimoz O, Pieroni L, Lawrence C, Edouard A, Costa Y, et al. (1996) Prospective, randomized trial of two antiseptic solutions for prevention of central venous or arterial catheter colonization and infection in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med 24: 1818–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Legras A, Cattier B, Dequin PF, Boulain T, Perrotin D (1997) Etude prospective randomisée pour la prévention des infections liées aux cathéters: chlorhexidine alcoolique contre polyvidone iodée [Prospective randomised trial for prevention of vascular-catheter infection: alcohol chlorhexidine versus povidone-iodine]. Reanimation et Urgences 6: 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cobbett S, LeBlanc A (2000) Minimising IV site infection while saving time and money. Australian Infection Control 5: 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Humar A, Ostromecki A, Direnfeld J, Marshall JC, Lazar N, et al. (2000) Prospective randomized trial of 10% povidone-iodine versus 0.5% tincture of chlorhexidine as cutaneous antisepsis for prevention of central venous catheter infection. Clin Infect Dis 31: 1001–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maki DG, Knasinski V, Narans LL, Gordon BJ (2001) A randomized trial of a novel 1% chlorhexidine-75% alcohol tincture versus 10% povidone iodine for cutaneous disinfection with vascular catheters [abstract]. Abstract 142. 11th Annual Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Meeting; 1–3 April 2001; Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 37. Langgartner J, Linde HJ, Lehn N, Reng M, Schölmerich J, et al. (2004) Combined skin disinfection with chlorhexidine/propanol and aqueous povidone-iodine reduces bacterial colonisation of central venous catheters. Intensive Care Med 30: 1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Astle CM, Jensen L (2005) A trial of ExSept for hemodialysis central venous catheters. Nephrol Nurs J 32: 517–525. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly JW, Usry G, Blackhurst D, Bushey M, Steed C (2005) Prevention of infections related to central venous catheters and arterial catheters in intensive care patients: a prospective randomized trial of chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) versus povidone iodine (PI) [abstract]. Abstract 165. 15th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; 9–12 April 2005; Los Angeles, CA, USA.

- 40. Balamongkhon B, Thamlikitkul V (2007) Implementation of chlorhexidine gluconate for central venous catheter site care at Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand. Am J Infect Control 35: 585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mimoz O, Villeminey S, Ragot S, Dahyot-Fizelier C, Laksiri L, et al. (2007) Chlorhexidine-based antiseptic solution vs alcohol-based povidone-iodine for central venous catheter care. Arch Intern Med 167: 2066–2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Small H, Adams D, Casey AL, Crosby CT, Lambert PA, et al. (2008) Efficacy of adding 2% (w/v) chlorhexidine gluconate to 70% (v/v) isopropyl alcohol for skin disinfection prior to peripheral venous cannulation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 29: 963–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vallés J, Fernández I, Alcaraz D, Chacón E, Cazorla A, et al. (2008) Prospective randomized trial of 3 antiseptic solutions for prevention of catheter colonization in an intensive care unit for adult patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 29: 847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Garland JS, Alex CP, Uhing MR, Peterside IE, Rentz A, et al. (2009) Pilot trial to compare tolerance of chlorhexidine gluconate to povidone-iodine antisepsis for central venous catheter placement in neonates. J Perinatol 29: 808–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, Kubota K (2009) Comparison of 0.05% chlorhexidine and 10% povidone-iodine as cutaneous disinfectant for prevention of central venous catheter-related bloodstream infection: a comparative study. Eur Surg Res 43: 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chaiyakunapruk N, Veenstra DL, Lipsky BA, Saint S (2002) Chlorhexidine compared with povidone-iodine solution for vascular catheter-site care: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 136: 792–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rickard C, Ray-Barruel G (2010) Systematic review of infection control literature relating to intravascular devices. In: National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Australian guidelines for the prevention and control of infection in healthcare. Appendix 2: Process Report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Available: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/cd33. Accessed 3 Feb 2012.

- 48. Chaiyakunapruk N, Veenstra DL, Lipsky BA, Sullivan SD, Saint S (2003) Vascular catheter site care: the clinical and economic benefits of chlorhexidine gluconate compared with povidone iodine. Clin Infect Dis 37: 764–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, et al. (2011) Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis 52: e162–e193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Berry AR, Watt B, Goldacre MJ, Thomson JW, McNair TJ (1982) A comparison of the use of povidone-iodine and chlorhexidine in the prophylaxis of postoperative wound infection. J Hosp Infect 3: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brown TR, Ehrlich CE, Stehman FB, Golichowski AM, Madura JA, et al. (1984) A clinical evaluation of chlorhexidine gluconate spray as compared with iodophor scrub for preoperative skin preparation. Surg Gynecol Obstet 158: 363–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ostrander RV, Botte MJ, Brage ME (2005) Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in foot and ankle surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87: 980–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Veiga DF, Damasceno CA, Veiga-Filho J, Figueiras RG, Vieira RB, et al. (2008) Povidone iodine versus chlorhexidine in skin antisepsis before elective plastic surgery procedures: a randomized controlled trial. Plast Reconstr Surg 122: 170e–171e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cheng K, Robertson H, St Mart JP, Leanord A, McLeod I (2009) Quantitative analysis of bacteria in forefoot surgery: a comparison of skin preparation techniques. Foot Ankle Int 30: 992–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Paocharoen V, Mingmalairak C, Apisarnthanarak A (2009) Comparison of surgical wound infection after preoperative skin preparation with 4% chlorhexidine [correction of chlohexidine] and povidone iodine: a prospective randomized trial. J Med Assoc Thai 92: 898–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Saltzman MD, Nuber GW, Gryzlo SM, Marecek GS, Koh JL (2009) Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91: 1949–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Swenson BR, Hedrick TL, Metzger R, Bonatti H, Pruett TL, et al. (2009) Effects of preoperative skin preparation on postoperative wound infection rates: a prospective study of 3 skin preparation protocols. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 30: 964–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sistla SC, Prabhu G, Sistla S, Sadasivan J (2010) Minimizing wound contamination in a ‘clean’ surgery: comparison of chlorhexidine-ethanol and povidone-iodine. Chemotherapy 56: 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Levin I, Amer-Alshiek J, Avni A, Lessing JB, Satel A, et al. (2011) Chlorhexidine and alcohol versus povidone-iodine for antisepsis in gynecological surgery. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 20: 321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Edwards PS, Lipp A, Holmes A (2004) Preoperative skin antiseptics for preventing surgical wound infections after clean surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD003949. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61. Reichel M, Heisig P, Kohlmann T, Kampf G (2009) Alcohols for skin antisepsis at clinically relevant skin sites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53: 4778–4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kampf G, Shaffer M, Hunte C (2005) Insufficient neutralization in testing a chlorhexidine-containing ethanol-based hand rub can result in a false positive efficacy assessment. BMC Infect Dis 5: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rittle KH (2006) Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in foot and ankle surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88: 1160–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fletcher N, Sofianos D, Berkes MB, Obremskey WT (2007) Prevention of perioperative infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89: 1605–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program (SCOAP) (2010) SCOAP Community speaks up: chlorhexidine use. Available: http://scoap.wordpress.com/2010/03/17/chlorhexidine. Accessed 3 Feb 2012.

- 66.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2011) Review proposal consultation of clinical guideline CG74 Surgical Site Infection. Available: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG74/ReviewProposal. Accessed 3 Feb 2012.

- 67. Hibbard JS (2005) Analyses comparing the antimicrobial activity and safety of current antiseptic agents: a review. J Infus Nurs 28: 194–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (1994) Tentative final monograph for health-care antiseptic drug products; proposed rule. 21 CFR Parts 333 and 369. Federal Register 59 (116): 31402–31452. Available: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-1994-06-17/html/94-14503.htm. Accessed 3 Feb 2012.

- 69. Art G (2007) Comparison of the safety and efficacy of two topical antiseptic products: chlorhexidine gluconate + isopropyl alcohol and povidone-iodine + isopropyl alcohol. Journal of the Association for Vascular Access 12: 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, et al. (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6 (7): e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bradford-Hill A (1965) The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med 58: 295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mahid SS, Hornung CA, Minor KS, Turina M, Galandiuk S (2006) Systematic reviews and meta-analysis for the surgeon scientist. Br J Surg 93: 1315–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Results of risk of bias assessment for studies evaluating antiseptics for blood culture collection.

(PDF)

Results of risk of bias assessment for studies evaluating antiseptics for vascular catheter insertion.

(PDF)

Results of risk of bias assessment for studies evaluating antiseptics for surgical skin preparation.

(PDF)

Eligibility criteria, literature search strategy and risk of bias assessment.

(PDF)

PRISMA Checklist.

(PDF)