Background: The mechanism underlying the anabolic effect of estrogen on the skeleton is unclear.

Results: We report that estrogen-induced bone formation in mice occurs through oxytocin (OT) produced by osteoblasts in bone marrow.

Conclusion: Feed-forward OT release in bone marrow by a rising estrogen level may facilitate rapid skeletal recovery after lactation.

Significance: The study highlights a novel mechanism for estrogen action on bone.

Keywords: Bone, Estrogen, Lactation, Osteoporosis, Pituitary Gland, Bone Remodeling, Oxytocin

Abstract

Estrogen uses two mechanisms to exert its effect on the skeleton: it inhibits bone resorption by osteoclasts and, at higher doses, can stimulate bone formation. Although the antiresorptive action of estrogen arises from the inhibition of the MAPK JNK, the mechanism of its effect on the osteoblast remains unclear. Here, we report that the anabolic action of estrogen in mice occurs, at least in part, through oxytocin (OT) produced by osteoblasts in bone marrow. We show that the absence of OT receptors (OTRs) in OTR−/− osteoblasts or attenuation of OTR expression in silenced cells inhibits estrogen-induced osteoblast differentiation, transcription factor up-regulation, and/or OT production in vitro. In vivo, OTR−/− mice, known to have a bone formation defect, fail to display increases in trabecular bone volume, cortical thickness, and bone formation in response to estrogen. Furthermore, osteoblast-specific Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice, but not TRAP-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice, mimic the OTR−/− phenotype and also fail to respond to estrogen. These data attribute the phenotype of OTR deficiency to an osteoblastic rather than an osteoclastic defect. Physiologically, feed-forward OT release in bone marrow by a rising estrogen concentration may facilitate rapid skeletal recovery during the latter phases of lactation.

Introduction

Oxytocin (OT)4 is a nonapeptide synthesized in the hypothalamus and released into the circulation by the posterior pituitary. Its primary function is to mediate the milk ejection reflex in nursing mammals (1). It also augments uterine contraction during parturition (2). Serum OT levels peak during late pregnancy and are maintained during lactation. These periods correspond, respectively, to maximal fetal and postnatal bone growth, which in turn leads to maternal losses from the skeleton of ∼120 g of calcium (3, 4). Hormonal adaptations, including low estrogen and persistently elevated parathyroid hormone-related protein levels, as well as increased sympathetic tone, all lead to a state of maternal hyper-resorption and intergenerational calcium transfer (3–5). However, the profound bone loss of lactation recovers fully within a relatively short period even as estrogen levels are slowly returning to normal (5). The mechanism(s) responsible for this dramatic anabolic skeletal recovery remain poorly understood.

To determine whether OT mediates any or all of these functions during pregnancy and/or lactation, we studied whether OT directly affects the skeleton. Although intracerebroventricular OT does not affect bone remodeling, peripheral administration does affect bone remodeling and bone mass (6). However, instead of recapitulating the elevated resorption and bone loss that occur during pregnancy and lactation, peripherally injected OT markedly increases bone mass in both wild-type and ovariectomized mice (6, 7). In line with its peripheral effect, we found that osteoblasts possess abundant OT receptors (OTRs) and that OT triggers osteoblast differentiation to a mature mineralizing phenotype (6). Consistent with this anabolic action, the genetic deletion of OT or the OTR in mice decreases osteoblast differentiation and bone formation, resulting in osteopenia (6). Furthermore, the increased bone formation noted normally during pregnancy is attenuated in OT−/− mice, as is fetal skeletal mineralization in OT−/− pups (8). Together, these findings suggest that the anabolic action of OT may, in fact, facilitate maternal skeletal recovery and fetal skeletogenesis.

OT is known to be produced in peripheral tissues, such as the testes, ovaries, heart, lungs, and vascular tissue (9–14). In certain of these organs, estrogen regulates OT and/or OTR expression (15, 16). Likewise, we found that OT is produced in abundance by bone marrow osteoblasts in response to estrogen, with the potential of exerting an anabolic effect on the skeleton (17). Estrogen at high doses is a skeletal anabolic (18), but its precise mechanism remains unknown. Here, we show that the osteoblastic OTR is required for the full anabolic action of estrogen. We postulate that an autocrine feed-forward OT/OTR loop exists in which estrogen releases OT from osteoblasts, which then acts upon osteoblastic OTRs to further amplify estrogen action. This could be particularly advantageous for maternal skeletal replenishment during the postpartum period, when estrogen levels are returning to normal and OT is high (19).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mouse Models

OTR−/− mice, originally created on a C57BL/6J×129Sv background (6), have been backcrossed with C57BL/6J mice for >15 generations. OTRfl/fl mice were developed as described previously on a C57BL/6J background (33); the mice have subsequently been backcrossed further with C57BL/6J mice for >10 generations. All mice were group-housed (five mice per cage) upon weaning at ∼3 weeks of age. Col2.3-Cre and TRAP-Cre mice were generous gifts from Drs. Simon Mendez-Ferrer (Mount Sinai School of Medicine) and David Roodman (University of Pittsburgh), respectively. The two Cre transgenic lines were crossed initially with OTRfl/fl mice, following which the Cre+/OTRfl/+ genotypes were crossed with OTRfl/fl mice to yield the respective osteoblast- and osteoclast-specific Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice. The absence of the OTR was confirmed by PCR and Western blotting in isolated cells as described (34).

Skeletal Phenotyping

Protocols approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the University of Bari Animal Welfare Committee were used for injecting, bleeding, ovariectomizing, and killing female mice. Areal bond mineral density (BMD) was measured at various sites representing trabecular and cortical bone (Lunar PIXImus, GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI). Micro-computed tomography was performed on trabecular bone (μCT 40, SCANCO Medical). For histomorphometry, groups of female mice received either calcein (15 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) 10 and 2 days prior to death or, for specific experiments, calcein and xylenol orange (90 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) 6 and 1 days prior to death. Standard protocols were utilized for sectioning the spine and femur and for dynamic and static histomorphometry (24, 35). In separate experiments, female mice were injected intraperitoneally either with a single dose or biweekly with 50 μg/kg 17β-estradiol or 0.9% (w/v) NaCl (vehicle) (cumulative weekly dose of 100 μg/kg). In certain instances, blood (∼1 ml) was collected by intracardiac puncture. Osteocalcin and OT were measured using mouse-based osteocalcin (DRG Inc.) and OT (Enzo Life Sciences) ELISA kits, respectively.

Cell Experiments

Osteoblasts were isolated from OTR−/− and wild-type female mouse bone marrow-adherent fractions or from calvarias of 5-day-old pups (gender unknown). Cells were cultured in phenol red-free α-minimal essential medium (Invitrogen) with 10% charcoal-stripped FCS in the presence of 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid and 10 mm β-glycerophosphate (Sigma) for mRNA and protein extraction and Von Kossa staining. MC3T3-E1 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Anna Teti (University of L'Aquila). These cells were transfected with OTR siRNA or vector-only duplexes (50 nm) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Western blotting and quantitative PCR (qPCR) were performed as described (6).

It is difficult to determine the sex of mice before 2–3 weeks. However, we utilized 5-day-old pups to isolate calvarial osteoblasts for PCR and Western blotting rather than bone marrow-derived osteoblasts because of the possible contamination of these cultures. Older mice cannot be used for calvarial osteoblast cultures due to difficulties in obtaining highly pure osteoblast fractions. We also show that estrogen induced robust OT and OTR expression in male osteoblasts (supplemental Fig. 1); the time course of the effect is concordant with that seen in female cells (17).

RESULTS

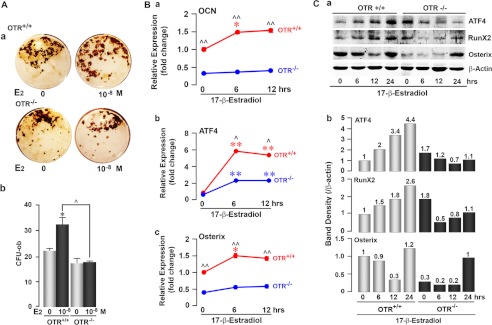

Estrogen is known to exert its anabolic action in rodents by enhancing osteoblast differentiation, although an effect on apoptosis has also been described (20). To study whether OT mediates estrogen effects on osteoblastogenesis, we questioned whether OTR−/− calvarial osteoblasts were less sensitive to estrogen-induced differentiation. We found that 17β-estradiol increased mineralizing osteoblast colony (osteoblast colony-forming units) formation in wild-type bone marrow stromal cell cultures, but not in cultures from OTR−/− mice (Fig. 1A). Likewise, 17β-estradiol-induced expression of the differentiation gene osteocalcin in wild-type osteoblasts, albeit modest, was abolished in OTR−/− cells (Fig. 1B, panel a). These data show that the augmentation of osteoblast differentiation by estrogen requires OTRs.

FIGURE 1.

Estrogen-induced osteoblastogenesis is attenuated in OTR−/− cells. A, representative images (panel a) and colony counts (panel b) of ex vivo Von Kossa-positive mineralizing colonies (osteoblast colony-forming units (CFU-ob)) arising from wild-type (OTR+/+) or OTR−/− bone marrow stromal cells with either 17β-estradiol (E2; 10−8 m) or vehicle for 21 days. For panel b, zero dose versus 17β-estradiol (10−8 m) (*, p < 0.05) and wild-type versus OTR−/− (^, p < 0.05) (in duplicate). B, panel a, qPCR for osteocalcin (OCN) gene expression in OTR+/+ and OTR−/− osteoblasts for 0, 6, and 12 h. Expression was normalized to GAPDH and is plotted as -fold increase from the 0-h wild-type sample. Panels b and c, qPCR of wild-type (red) and OTR−/− (blue) calvarial osteoblasts showing changes in the expression of ATF4 (panel b) and Osterix (panel c) mRNA levels after treatment with 17β-estradiol (10−8 m) for 0, 6, or 12 h. Expression was normalized to GAPDH and plotted as -fold increase from the 0-h wild-type sample. Statistics were as follows: Student's t test with the Bonferroni correction, comparing 6- and/or 12-h time points each versus 0 h (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01), as well as wild-type versus OTR−/− cells at all time points (^, p < 0.05; ^^, p < 0.01) (done twice in triplicate). C, panel a, OTR+/+ and OTR−/− calvarial osteoblasts were evaluated for changes in their expression of the osteoblast transcription factors ATF4, Runx2, and Osterix by Western blotting after treatment with 17β-estradiol (10−8 m) for 6, 12, and 24 h. Panel b, the band density was quantitated after normalizing to the loading control β-actin.

To understand why estradiol failed to increase the differentiation of OTR−/− osteoblasts, we studied the expression of the critical transcription factors Runx2, ATF4, and Osterix in cultures of calvarial osteoblasts isolated from 5-day-old male and female pups. Western blotting revealed that 17β-estradiol significantly increased Runx2 and ATF4 protein expression in wild-type cells, whereas these increases were blunted in OTR−/− cells for up to 12 h (Fig. 1C). qPCR confirmed the up-regulation of ATF4 mRNA (Fig. 1B, panel b). Likewise, 17β-estradiol modestly but significantly increased Osterix mRNA at both 6 and 12 h in wild-type osteoblasts, but not in OTR−/− cells (Fig. 1B, panel c). We did not observe parallel changes in Osterix protein with estrogen. However, levels remained lower in OTR−/− cells for up to 12 h after 17β-estradiol treatment (Fig. 1C).

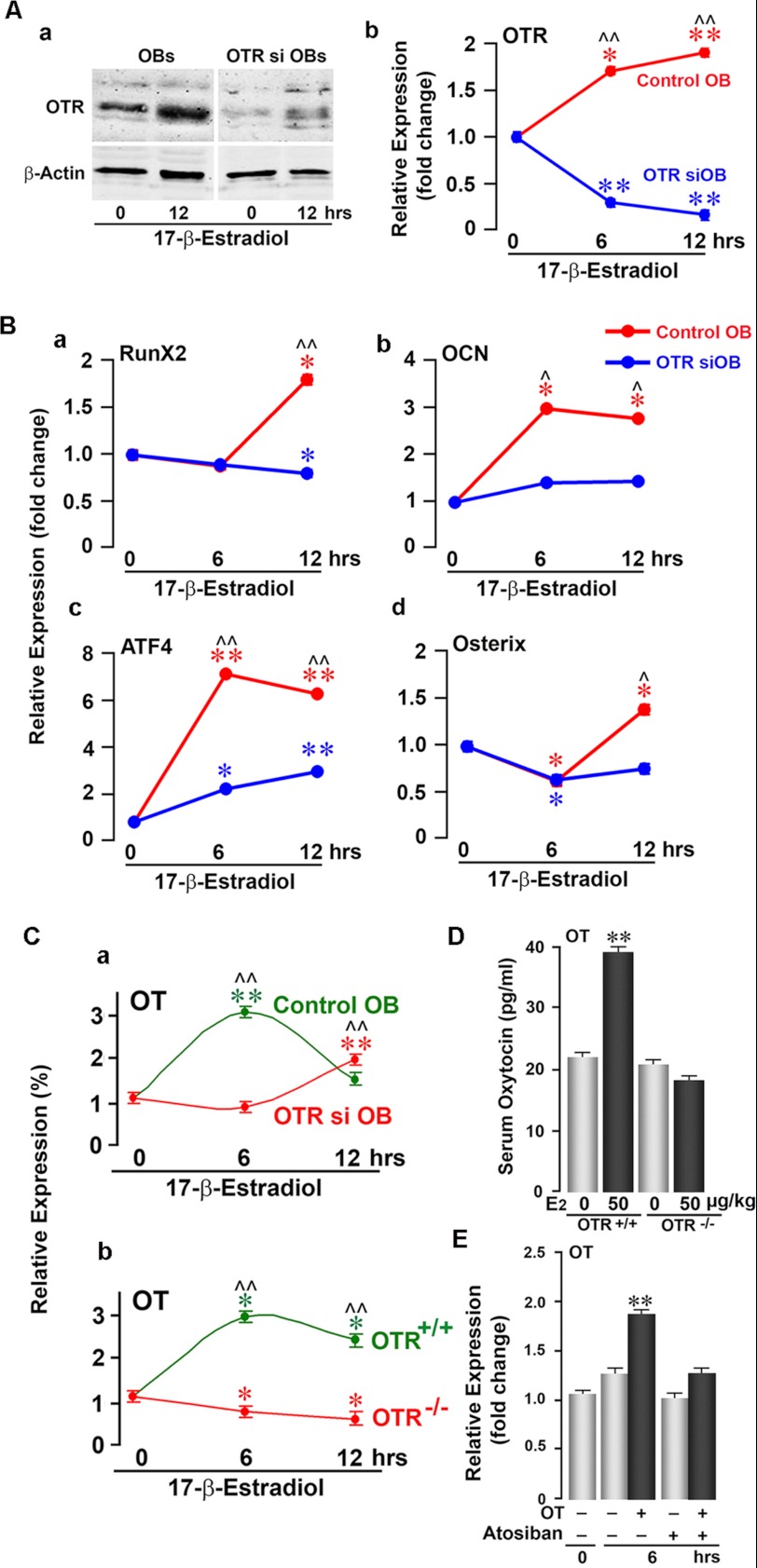

To confirm these ex vivo findings from primary bone marrow and calvarial osteoblast cultures, we used siRNA to knock down OTR expression in a pre-osteoblastic cell line, MC3T3-E1. Western blotting and qPCR showed a dramatic reduction in OTR protein and mRNA, respectively, in OTR-silenced cells (Fig. 2A). Whereas 17β-estradiol significantly increased Runx2, Osterix, ATF4, and osteocalcin mRNAs in vector-treated cells, this effect was profoundly attenuated in OTR-silenced cells (Fig. 2B). The data suggest that the pro-osteoblastic actions of 17β-estradiol require OTR expression and occur mainly through the up-regulation of Runx2 and ATF4, although other pathways may also be involved.

FIGURE 2.

OTR knockdown attenuates estrogen-induced osteoblast differentiation. A, Western blotting (panel a) and qPCR (panel b) of MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts (OBs) showing effective siRNA-mediated knockdown of the OTR. A 12-h time course was performed to demonstrate that OTR mRNA remained knocked down following 17β-estradiol (10−8 m) addition. B, qPCR of MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblastic cells expressing either the OTR siRNA (OTR siOB) or empty vector (control OB) showing 17β-estradiol-induced changes in the expression of Runx2 (panel a), osteocalcin (OCN; panel b), ATF4 (panel c), and Osterix (panel d) mRNAs at 0, 6, and 12 h. Expression was normalized to GAPDH. C, effects of 17β-estradiol (10−8 m) on OT mRNA expression in OTR siRNA-silenced (OTR si OB; red) or vector-treated (Control OB; green) MC3T3-E1 cells (panel a) and in OTR−/− (red) or wild-type (green) osteoblasts (panel b) at 0, 6, and 12 h. mRNA expression is plotted as a percentage of 0 h and normalized to GAPDH. D, serum OT (by ELISA) in wild-type and OTR−/− mice after a 12-h treatment with either 17β-estradiol (E2; 50 μg/kg; black bars) or a control (gray bars). E, qPCR for OT mRNA showing that treatment of MC3T3-E1 cells with OT (10−8 m) increased OT mRNA at 6 h. To evaluate the specificity of OT-induced OT mRNA up-regulation, the OTR antagonist atosiban (10−8 m) was applied 20 min prior to OT addition. OT mRNA expression was normalized to GAPDH and is plotted as -fold increase from the 0-h non-treated sample. Statistics were as follows: Student's t test with the Bonferroni correction, comparing 6- and/or 12-h time points each versus 0 h (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01), as well as wild-type versus OTR siRNA cells at all time points (^, p < 0.05; ^^, p < 0.01) (in triplicate). For D, comparisons between zero-dose and 17β-estradiol injections as described above (**, p < 0.01) (in duplicate).

As is evident, all genes are not equally responsive to estrogen. Furthermore, estrogen responsiveness can vary depending on osteoblast source, differentiation state, and culture conditions. However, it is important to note that the results from bone marrow osteoblast cultures showed overall concordance with the results from calvarial osteoblast cultures in terms of the lack of responsiveness of OTR−/− cells to 17β-estradiol.

Our previous data showing that 17β-estradiol induces OT and OTR expression in osteoblasts (17) prompted us to further determine whether the effects of estrogen on osteoblast OT expression were dependent on OTRs. We found that OT mRNA expression in response to 17β-estradiol was abrogated in OTR−/− (female) and OTR-silenced MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts (Fig. 2C), suggesting that OTRs are required for estrogen-induced OT production. In line with this, OTR−/− mice failed to show an increase in serum OT levels in response to 17β-estradiol (Fig. 2D). Knowing that OTRs are required for estrogen-induced OT expression, we further hypothesized that OT acts on its receptor to induce its own production. By using qPCR, we found that OT did induce OT mRNA in MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts at 6 h (Fig. 2E). This putative autocrine stimulation was abolished by the OTR antagonist atosiban (Fig. 2E), establishing that the OT-induced OT expression requires OTR activation.

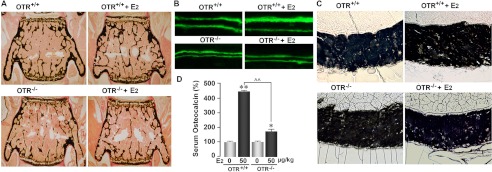

Data from this and our previous study (17) support a hypothesis whereby estrogen induces the expression of both OT and the OTR. The induced OT then acts upon the OTR in an autocrine loop to amplify the anabolic effects on estrogen. To test this hypothesis in vivo, we treated 2-month-old female OTR−/− mice or wild-type littermates with 17β-estradiol (50 μg/kg) or vehicle biweekly for 30 days (cumulative weekly dose of 100 μg/kg). This is consistent with the cumulative weekly dose of between 70 and 280 μg/week (10–40 μg/kg/day) used by others (21, 22). Histomorphometry showed lower bone volume/trabecular volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness, mineral apposition rate (MAR), and bone formation rate (BFR) in placebo-treated OTR−/− mice compared with placebo-treated wild-type littermates (Fig. 3), confirming previous results (6). 17β-Estradiol significantly increased trabecular and cortical bone parameters (BV/TV, trabecular number (Tb.N), MAR, BFR, trabecular osteoblast number (Tb.N.Ob/B.Pm), cortical thickness, and cortical osteoblast number (Ct.N.Ob/B.Pm) (periosteal)) in wild-type mice, but not in OTR−/− mice (Table 1). Interestingly, Tb.N, MAR, and cortical thickness further declined in OTR−/− mice despite 17β-estradiol treatment. Osteoclast parameters in trabecular and cortical bone were not significantly different between wild-type and OTR−/− mice, consistent with previous results (6), and did not significantly change in either group upon 17β-estradiol treatment (Table 1). Concordant with a bone formation defect, although 17β-estradiol elevated serum osteocalcin, a bone formation marker in OTR−/− and wild-type mice, the response was significantly (p < 0.01) attenuated in OTR−/− mice (Fig. 3D). In sum, the overall failure of OTR−/− mice to display a full anabolic response to 17β-estradiol suggests that the bone-forming action of estrogen is, at least in large part, OTR-dependent.

FIGURE 3.

Ability of estrogen to increase bone mass in wild-type mice requires functional OTRs. Two-month-old OTR−/− mice or wild-type (OTR+/+) littermates were treated with 17β-estradiol (E2; 50 μg/kg) or placebo biweekly (cumulative dose of 100 μg/kg/week). Representative images show the effect of 17β-estradiol on trabecular bone volume (A), double-labeled surfaces (B), and cortical thickness (C) in wild-type and OTR−/− mice. D, serum osteocalcin (by ELISA) 12 h after a single 17β-estradiol injection of 50 μg/kg. Statistics were as follows: Student's t test with the Bonferroni correction, comparing 17β-estradiol treatment versus zero dose (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01), as well as wild-type versus OTR−/− mice (^^, p < 0.01).

TABLE 1.

Static and dynamic estimates from bone histomorphometry, namely BV/TV, Tb.N, trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp), MAR, BFR, trabecular osteoblast numbers (Tb.N.Ob/B.Pm), trabecular osteoclast numbers (Tb.N.Oc/B.Pm), cortical thickness (Ct.Th), cortical osteoblast numbers (Ct.N.Ob/B.Pm), and cortical osteoclast numbers (Ct.N.Oc/B.Pm) (units as shown)

Results are represented as mean ± S.E. (n = 3–10). Statistics were as follows: Student's t test with the Bonferroni correction, comparing 17β-estradiol (E2) treatment versus zero dose, as well as wild-type versus OTR−/− mice (p values as shown).

| OTR+/+ |

OTR−/− |

WT p vs. knockout p | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 μg/kg E2 | 50 μg/kg E2 | Change | p | 0 μg/kg E2 | 50 μg/kg E2 | Change | p | ||

| % | % | ||||||||

| BV/TV (%) | 8.17 ± 0.09 | 8.93 ± 0.19 | +9.3 | <0.001 | 5.74 ± 0.17 | 5.62 ± 0.09 | −1.97 | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Tb.N (1/μm) | 1.34 ± 0.02 | 1.53 ± 0.08 | +13.8 | <0.01 | 1.37 ± 0.03 | 1.24 ± 0.04 | −9.17 | 0.012 | 0.231 |

| Tb.Th (μm) | 6.13 ± 0.12 | 6.08 ± 0.34 | −0.8 | 0.875 | 4.18 ± 0.08 | 4.58 ± 0.16 | +9.57 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| Tb.Sp (μm) | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.69 ± 0.04 | −0.9 | 0.71 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.82 ± 0.03 | +9.99 | 0.015 | 0.348 |

| MAR (μm/day) | 2.15 ± 0.06 | 2.33 ± 0.05 | +7.9 | <0.001 | 1.47 ± 0.07 | 1.42 ± 0.05 | −3.81 | 0.031 | <0.001 |

| BFR (μm3/μm2/day) | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | +66.4 | <0.001 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | −4.34 | 0.179 | 0.03 |

| Tb.N.Ob/B.Pm (per μm) | 3.20 ± 0.06 | 3.93 ± 0.11 | +22.8 | <0.001 | 3.25 ± 0.06 | 3.30 ± 0.12 | +1.54 | 0.401 | 0.388 |

| Tb.N.Oc/B.Pm (per μm) | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | −2.37 | 0.140 | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | −18.9 | 0.160 | 0.190 |

| Ct.Th (μm) | 120 ± 4.77 | 143 ± 14.3 | +29.9 | <0.001 | 119 ± 13.8 | 86.3 ± 19.3 | −27.3 | <0.001 | 0.448 |

| Ct.N.Ob/B.Pm (per μm) | 2.75 ± 0.09 | 3.46 ± 0.23 | +57.3 | <0.001 | 2.70 ± 0.10 | 2.63 ± 0.03 | −2.47 | 0.186 | 0.339 |

| Ct.N.Oc/B.Pm (per μm) | 2.24 ± 0.47 | 2.05 ± 0.36 | −8.36 | 0.32 | 2.23 ± 0.15 | 2.03 ± 0.27 | −9.11 | 0.253 | 0.492 |

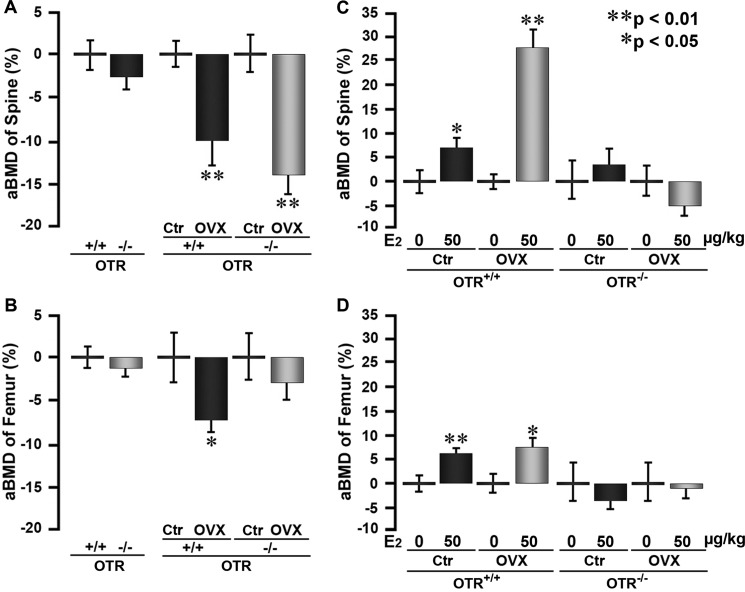

We next tested whether OT signaling also plays a role in mediating the effect of estrogen on bone mass in hypogonadal mice. For this, mice were ovariectomized or sham-operated and given either 17β-estradiol or vehicle as described above. Areal BMD measurements 30 days after ovariectomy revealed significant decrements in wild-type and OTR−/− mice at the lumbar spine and femur (Fig. 4, A and B). However, compared with zero-dose controls, both sham-operated and wild-type mice treated with 17β-estradiol showed increases in BMD, whereas the respective OTR−/− mice did not (Fig. 4, C and D). This suggests that, as in the eugonadal state, an intact OTR axis contributes to the action of estrogen in hypogonadism.

FIGURE 4.

Ability of estrogen to increase bone mass in ovariectomized mice is dependent on OTRs. Shown are areal BMD (aBMD; PIXImus) measurements at the spine and femur of sham-operated (control (Ctr)) and ovariectomized (OVX) OTR−/− and wild-type (OTR+/+) mice that were injected with 17β-estradiol (E2; 50 μg/kg) or placebo biweekly (cumulative dose of 100 μg/kg/week). A and B, effect of ovariectomy versus sham operation in the two genotypes. C and D, effect of 17β-estradiol versus placebo within the various groups. Statistics were as follows: means ± S.E. of the percent change shown using the respective controls (n = 5–6/group) and Student's t test with the Bonferroni correction, comparing ovariectomized versus control mice (A and B) and 17β-estradiol versus zero dose (C and D) (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

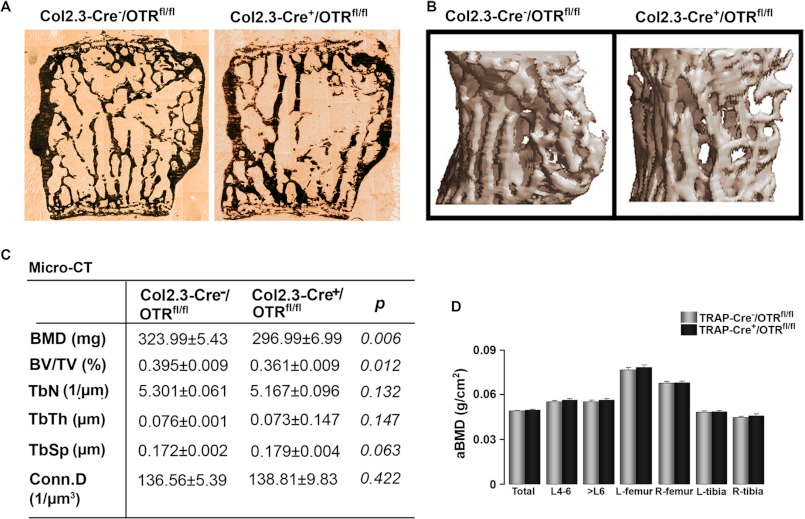

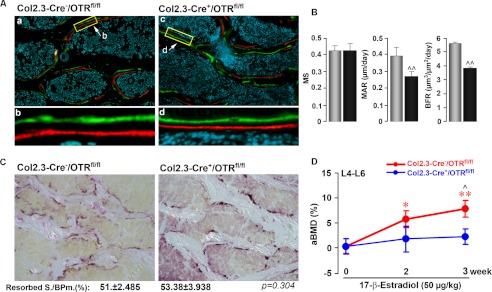

We sought to determine definitively whether the effect of 17β-estradiol in increasing bone mass is osteoblast-mediated or whether there is an osteoclastic component. For this, we generated osteoblast- or osteoclast-specific OTR-deficient mice by crossing OTRfl/fl mice with Col2.3-Cre or TRAP-Cre mice, respectively (see “Experimental Procedures”). The absence of the OTR in osteoblasts, but not in osteoclasts, in Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice resulted in a significant reduction in BMD and BV/TV, with a trend toward reduced Tb.N and increased trabecular spacing (Fig. 5, A–C). That the phenotype of the osteoblast-specific Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mouse recapitulated, in full, the global OTR−/− phenotype suggests that an osteoblast defect is the predominant, if not the sole, determinant of the osteopenia of OTR deficiency. Fig. 5D shows that osteoclast-selective TRAP-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice did not display osteopenia at either trabecular or cortical sites, confirming that OTR deficiency in the osteoclast does not alter bone mass (6). These mice were therefore not further phenotyped using micro-computed tomography or histomorphometry. Reduced bone formation was confirmed, however, in Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice by dynamic histomorphometry. Both MAR and BFR were reduced significantly, as expected, without effects on mineralizing surface or resorbed surface (Fig. 6, A–C).

FIGURE 5.

Osteoblast-specific deletion of OTRs recapitulates global OTR deficiency. The skeletons of 16-week-old osteoblast-specific Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice or control Col2.3-Cre−/OTRfl/fl littermates were phenotyped for differences in static and dynamic histomorphometry parameters. Representative images show von Kossa-stained trabecular bone (A) and micro-computed tomography of trabecular bone (B). C, micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT)-derived estimates of volumetric BMD, BV/TV, Tb.N, trabecular thickness (TbTh), trabecular spacing (TbSp), and connectivity density (Conn.D) in the two genotypes (units as shown). D, areal BMD (aBMD) using PIXImus of the osteoclast-specific TRAP-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice or control TRAP-Cre−/OTRfl/fl littermates recorded at the stated sites. Statistics were as follows: Student's t test with the Bonferroni correction, comparing Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl versus Col2.3-Cre−/OTRfl/fl mice (C) (p values as shown) and TRAP-Cre+/OTRfl/fl versus TRAP-Cre−/OTRfl/fl mice (D). L, left; R, right.

FIGURE 6.

Osteoblast OTR mediates the anabolic action of estrogen on the skeleton. Representative images show double labeling with calcein (green) and xylenol orange (red) (see “Experimental Procedures”) (A) together with estimates of mineralizing surface (MS), MAR, and BFR (B) in Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl and Col2.3-Cre−/OTRfl/fl mice. C, TRAP staining to show resorption areas, together with estimates of resorbed surface (Resorbed S./BPm.) in the two respective genotypes. D, effect of 17β-estradiol (50 μg/kg) or placebo biweekly (cumulative dose of 100 μg/kg/week) on areal BMD in Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl and Col2.3-Cre−/OTRfl/fl (control) mice. Statistics were as follows: mean ± S.E. (n = 6–19/group) and Student's t test with the Bonferroni correction, comparing Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl versus Col2.3-Cre−/OTRfl/fl mice (B and D) (^, p < 0.05; ^^, p < 0.01) and 17β-estradiol versus zero dose (D) (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

We used 16-week-old Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice to determine whether osteoblast rather than osteoclast OTRs mediate the skeletal anabolic effect of 17β-estradiol. Serial BMD measurements revealed that although 17β-estradiol expectedly increased BMD over 3 weeks of treatment in Col2.3-Cre−/OTRfl/fl (control) mice, it did not do so in Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice (Fig. 6D). At the 3-week time point, there was a significant BMD difference between 17β-estradiol-treated Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl and control mice (Fig. 6D). That the anabolic effect of 17β-estradiol on bone mass was abolished in mice selectively lacking OTRs in osteoblasts suggests that neither the osteoclast nor the nervous system contributes to the effect, at least in large part.

DISCUSSION

We hypothesize that estrogen acts to enhance osteoblast differentiation and bone formation, at least in part, by stimulating the production of OT, which then acts on its own receptor to trigger further OT release. This, we hypothesize, constitutes a local autocrine circuit that amplifies bone formation triggered by estrogen.

Our hypothesis is based upon several observations. First, our own evidence (6) and that from others (7) indicates that OT enhances osteoblastogenesis, bone formation, and/or bone mass through a peripheral action on osteoblast OTRs. In this respect, OT mimics estrogen, which, at higher than antiresorptive doses, stimulates osteoblastogenesis with some effects on osteoblast apoptosis (20). Second, this study provides in vitro evidence that OT is downstream of estrogen. Thus, the deficiency of OTRs in OTR−/− osteoblasts or OTR-silenced cells markedly reduces the effect of 17β-estradiol on mineralized colony formation, as well as the expression of certain osteoblast differentiation genes and transcription factors. Third, we have shown that OT is produced by osteoblasts and that 17β-estradiol stimulates OT expression within 2 h (17). 17β-Estradiol also stimulates OTR expression, but with a slower time course (17). Here, we have shown that estrogen action on OT production is dependent upon OTR expression; the absence of OTRs in OTR−/− osteoblasts or OTR down-regulation in silenced cells thus abolishes estrogen-induced OT expression. Finally, the effects of 17β-estradiol on bone mass and bone formation are abolished/attenuated in OTR−/− mice and, importantly, in osteoblast-specific Col2.3-Cre+/OTRfl/fl mice. In both models, no appreciable effects on osteoclast (resorption) parameters were noted.

Several implications arise from these studies. First, is the recurring notion that not only do primitive pituitary hormones (such as thyrotropin, FSH, and ACTH) have receptors in extra-endocrine targets, such as bone (23–25), but also that certain of these ligands (including thyrotropin-β, ACTH, and OT) themselves can be expressed in a host of tissues (17, 26, 27). We suggest that estrogen stimulates an autocrine OT circuit in which locally produced OT activates its own receptor. This role appears consistent with the historic function of OT in mineral homeostasis observed in lower mammals (9, 28).

Second, we have injected 17β-estradiol at a dose of 50 μg/kg biweekly, which corresponds to a cumulative dose of 100 μg/kg/week. This is consistent with doses between 10 and 40 μg/kg/day (or cumulative weekly doses of 70–280 μg/kg) used by others to prevent bone loss due to aging or ovariectomy (21, 22). Ovariectomy is associated with increased resorption and formation at least in the acute setting, and the effects of estrogen in restoring bone mass arise mainly from its anti-osteoclastic action (29) in a hyper-resorptive state. Here, we have shown that the effects of 17β-estradiol on bone mass in ovariectomized mice are also dependent on an intact OTR axis. However, to obviate confounding effects of elevated resorption and its inhibition by estrogen, and short of using chronically estrogen-deprived rodents (30), we have instead used wild-type mice with normal bone resorption and bone formation. As has been noted by others (21) in non-ovariectomized settings, we found that 17β-estradiol does not affect osteoclast parameters, whether or not the mice are devoid of OTRs. In contrast, osteoblast numbers, bone formation, and cortical and trabecular bone mass are all enhanced significantly with 17β-estradiol in wild-type mice. This anabolic action is attenuated in OTR−/− mice, suggesting that the effects of estrogen on bone mass are, at least in part, dependent on OTRs.

Third, our study definitively rules out mediation of OT effects on the skeleton through the osteoclast or central nervous system. We have shown previously that intracerebroventricular OT does not affect certain acute bone formation parameters (6), despite the known presence of OT-ergic neurons. We have now shown that the osteopenia of global OTR deficiency in OTR−/− mice is mimicked in its entirety by osteoblastic OTR deficiency in Col2.3-Cre−/OTRfl/fl mice. Furthermore, Col2.3-Cre−/OTRfl/fl mice fail to display increases in bone mass in response to 17β-estradiol. This confirms not only that the osteoblastic OTR is critical for skeletal homeostasis, but that it mediates selectively and solely the anabolic action of estrogen on the mouse skeleton.

Overall, our findings may have implications both biologically and clinically. The parallel actions of estrogen and OT on bone formation and particularly a feed-forward loop for estrogen-mediated OT release from the osteoblast may be of significance. For example, OT levels are high late in pregnancy, during parturition, and postpartum (19). These time periods also correspond to a period of relentless pressure on the maternal skeleton for bioavailable calcium, initially to support prenatal fetal mineralization and subsequently for postnatal nutrition from lactation (3, 4). Not surprisingly, significant cortical and trabecular bone loss is a consequence of lactation, as well as suppressed estrogen concentrations (4). However, with the onset of menses and immediately post-weaning, there is a rapid restoration of bone mass. This “anabolic” phase is likely to be multifactorial in origin and has been attributed to return of pre-pregnancy estrogen levels, a change in parathyroid hormone-related protein expression locally and/or systemically, and a reduction in osteocyte osteolysis (31). However, skeletal recovery is relatively quick, suggesting that estrogen restoration alone cannot be the sole explanation. Similarly, although skeletal parathyroid hormone-related protein is up-regulated with weaning, it is not essential for bone mass recovery (4). On the other hand, in the postpartum period during lactation, as estrogen production gradually returns, OT levels remain elevated, probably due to chronic suckling. A feed-forward autocrine network in the marrow niche, whereby rising estrogen levels enhance local OT production, ultimately leading to greater bone formation through the OTR, appears to be a plausible additional mechanism that could explain the bone-forming phase of skeletal recovery post-lactation.

Finally, the repletion of osteoblast OT signaling may represent a non-estrogenic means of restoring bone in those forms of bone loss that are characterized mainly by osteoblast dysfunction (32). Indeed, human OT is in use for inducing labor, and it is not inconceivable that bone-specific OT analogs may spare the reproductive organs. Finally and more broadly, future studies are needed to evaluate if the feed-forward OT loop, as well as short loops of other pituitary hormones, operates in tissues other than the skeleton and traditional endocrine targets.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AG023176 and AG040132 from NIA (to M. Z.) and DK080459 from NIDDK (to M. Z. and L. S.) and by National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Program Grant Z01-MH-002498-23 (to H.-J. L. and W. S. Y.). This work was also supported by grants from the Italian Space Agency (Osteoporosis and Muscular Atrophy Project), the European Space Agency (European Research in Space and Terrestrial Osteoporosis Microgravity Application Promotion Project), and the Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università della Ricerca (to A. Z.); by United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service Current Research Information System Program Grant 5450-51000-046-00D (to J. C.); and by the American Federation for Aging Research (to J. I.).

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- OT

- oxytocin

- OTR

- OT receptor

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

- BMD

- bone mineral density

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- BV/TV

- bone volume/trabecular volume

- MAR

- mineral apposition rate

- BFR

- bone formation rate

- Tb.N

- trabecular number.

REFERENCES

- 1. Breton C., Di Scala-Guenot D., Zingg H. H. (2001) Oxytocin receptor gene expression in rat mammary gland: structural characterization and regulation. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 175–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blanks A. M., Thornton S. (2003) The role of oxytocin in parturition. BJOG 110, 46–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kovacs C. S. (2001) Calcium and bone metabolism in pregnancy and lactation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 2344–2348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. VanHouten J. N., Wysolmerski J. J. (2003) Low estrogen and high parathyroid hormone-related peptide levels contribute to accelerated bone resorption and bone loss in lactating mice. Endocrinology 144, 5521–5529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Michalakis K., Peitsidis P., Ilias I. (2011) Pregnancy- and lactation-associated osteoporosis. Endocr. Regul. 45, 43–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tamma R., Colaianni G., Zhu L. L., DiBenedetto A., Greco G., Montemurro G., Patano N., Strippoli M., Vergari R., Mancini L., Colucci S., Grano M., Faccio R., Liu X., Li J., Usmani S., Bachar M., Bab I., Nishimori K., Young L. J., Buettner C., Iqbal J., Sun L., Zaidi M., Zallone A. (2009) Oxytocin is an anabolic bone hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 7149–7154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elabd C., Basillais A., Beaupied H., Breuil V., Wagner N., Scheideler M., Zaragosi L. E., Massiéra F., Lemichez E., Trajanoski Z., Carle G., Euller-Ziegler L., Ailhaud G., Benhamou C. L., Dani C., Amri E. Z. (2008) Oxytocin controls differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells and reverses osteoporosis. Stem Cells 26, 2399–2407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu X., Shimono K., Zhu L. L., Li J., Peng Y., Imam A., Iqbal J., Moonga S., Colaianni G., Su C., Lu Z., Iwamoto M., Pacifici M., Zallone A., Sun L., Zaidi M. (2009) Oxytocin deficiency impairs maternal skeletal remodeling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 388, 161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kiss A., Mikkelsen J. D. (2005) Oxytocin–anatomy and functional assignments: a minireview. Endocr. Regul. 39, 97–105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zingg H. H., Laporte S. A. (2003) The oxytocin receptor. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 14, 222–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thibonnier M., Conarty D. M., Preston J. A., Plesnicher C. L., Dweik R. A., Erzurum S. C. (1999) Human vascular endothelial cells express oxytocin receptors. Endocrinology 140, 1301–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Péqueux C., Breton C., Hagelstein M. T., Geenen V., Legros J. J. (2005) Oxytocin receptor pattern of expression in primary lung cancer and in normal human lung. Lung Cancer 50, 177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Assinder S. J., Carey M., Parkinson T., Nicholson H. D. (2000) Oxytocin and vasopressin expression in the ovine testis and epididymis: changes with the onset of spermatogenesis. Biol. Reprod. 63, 448–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jankowski M., Danalache B., Wang D., Bhat P., Hajjar F., Marcinkiewicz M., Paquin J., McCann S. M., Gutkowska J. (2004) Oxytocin in cardiac ontogeny. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 13074–13079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feng M., Qin J., Wang C., Ye Y., Wang S., Xie D., Wang P. S., Liu C. (2009) Estradiol up-regulates the expression of oxytocin receptor in colon in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 296, E1059–E1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stedronsky K., Telgmann R., Tillmann G., Walther N., Ivell R. (2002) The affinity and activity of the multiple hormone response element in the proximal promoter of the human oxytocin gene. J. Neuroendocrinol. 14, 472–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Colaianni G., Di Benedetto A., Zhu L. L., Tamma R., Li J., Greco G., Peng Y., Dell'Endice S., Zhu G., Cuscito C., Grano M., Colucci S., Iqbal J., Yuen T., Sun L., Zaidi M., Zallone A. (2011) Regulated production of the pituitary hormone oxytocin from human and murine osteoblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 411, 512–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Albright F., Bloomberg E., Smith P. H. (1940) Postmenopausal osteoporosis. Trans. Assoc. Am. Phys. 55, 298–305 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Soloff M. S., Alexandrova M., Fernstrom M. J. (1979) Oxytocin receptors: triggers for parturition and lactation. Science 204, 1313–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kousteni S., Bellido T., Plotkin L. I., O'Brien C. A., Bodenner D. L., Han L., Han K., DiGregorio G. B., Katzenellenbogen J. A., Katzenellenbogen B. S., Roberson P. K., Weinstein R. S., Jilka R. L., Manolagas S. C. (2001) Non-genotropic, sex-nonspecific signaling through the estrogen or androgen receptors: dissociation from transcriptional activity. Cell 104, 719–730 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Syed F. A., Mödder U. I., Roforth M., Hensen I., Fraser D. G., Peterson J. M., Oursler M. J., Khosla S. (2010) Effects of chronic estrogen treatment on modulating age-related bone loss in female mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 25, 2438–2446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Modder U. I., Riggs B. L., Spelsberg T. C., Fraser D. G., Atkinson E. J., Arnold R., Khosla S. (2004) Dose response of estrogen on bone versus the uterus in ovariectomized mice. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 151, 503–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abe E., Marians R. C., Yu W., Wu X. B., Ando T., Li Y., Iqbal J., Eldeiry L., Rajendren G., Blair H. C., Davies T. F., Zaidi M. (2003) TSH is a negative regulator of skeletal remodeling. Cell 115, 151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun L., Peng Y., Sharrow A. C., Iqbal J., Zhang Z., Papachristou D. J., Zaidi S., Zhu L. L., Yaroslavskiy B. B., Zhou H., Zallone A., Sairam M. R., Kumar T. R., Bo W., Braun J., Cardoso-Landa L., Schaffler M. B., Moonga B. S., Blair H. C., Zaidi M. (2006) FSH directly regulates bone mass. Cell 125, 247–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zaidi M., Sun L., Robinson L. J., Tourkova I. L., Liu L., Wang Y., Zhu L. L., Liu X., Li J., Peng Y., Yang G., Shi X., Levine A., Iqbal J., Yaroslavskiy B. B., Isales C., Blair H. C. (2010) ACTH protects against glucocorticoid-induced osteonecrosis of bone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8782–8787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vincent B. H., Montufar-Solis D., Teng B. B., Amendt B. A., Schaefer J., Klein J. R. (2009) Bone marrow cells produce a novel TSHβ splice variant that is up-regulated in the thyroid following systemic virus infection. Genes Immun. 10, 18–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Isales C. M., Zaidi M., Blair H. C. (2010) ACTH is a novel regulator of bone mass. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1192, 110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blair H. C., Robinson L. J., Sun L., Isales C., Davies T. F., Zaidi M. (2011) Skeletal receptors for steroid family regulating glycoprotein hormones: a multilevel, integrated physiologic control system. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1240, 26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shevde N. K., Bendixen A. C., Dienger K. M., Pike J. W. (2000) Estrogens suppress RANK ligand-induced osteoclast differentiation via a stromal cell-independent mechanism involving c-Jun repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 7829–7834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun L., Vukicevic S., Baliram R., Yang G., Sendak R., McPherson J., Zhu L. L., Iqbal J., Latif R., Natrajan A., Arabi A., Yamoah K., Moonga B. S., Gabet Y., Davies T. F., Bab I., Abe E., Sampath K., Zaidi M. (2008) Intermittent recombinant TSH injection prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4289–4294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qing H., Ardeshirpour L., Pajevic P. D., Dusevich V., Jähn K., Kato S., Wysolmerski J., Bonewald L. F. (2012) Demonstration of osteocytic perilacunar/canalicular remodeling in mice during lactation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1018–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Syed F. A., Iqbal J., Peng Y., Sun L., Zaidi M. (2010) Clinical, cellular, and molecular phenotypes of aging bone. Interdiscip. Top. Gerontol. 37, 175–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee H. J., Caldwell H. K., Macbeth A. H., Tolu S. G., Young W. S., 3rd (2008) A conditional knockout mouse line of the oxytocin receptor. Endocrinology 149, 3256–3263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mistry P. K., Liu J., Yang M., Nottoli T., McGrath J., Jain D., Zhang K., Keutzer J., Chuang W. L., Mehal W. Z., Zhao H., Lin A., Mane S., Liu X., Peng Y. Z., Li J. H., Agrawal M., Zhu L. L., Blair H. C., Robinson L. J., Iqbal J., Sun L., Zaidi M. (2010) Glucocerebrosidase gene-deficient mouse recapitulates Gaucher disease displaying cellular and molecular dysregulation beyond the macrophage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 19473–19478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parfitt A. M., Drezner M. K., Glorieux F. H., Kanis J. A., Malluche H., Meunier P. J., Ott S. M., Recker R. R. (1987) Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2, 595–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]