Background: Polyubiquitination of misfolded proteins is tightly associated with protein aggregation in neurodegenerative disease.

Results: Ataxin-3 regulates mutant SOD1 aggresome formation by trimming K63-linked polyubiquitin chains.

Conclusion: Deubiquitination by ataxin-3 plays a role in aggresome formation.

Significance: Our study provides a previously unrecognized mechanism for the formation of mutant SOD1 aggresomes through the deubiquitination of K63-linked polyubiquitin.

Keywords: Molecular Cell Biology, Neurodegenerative Diseases, Protein Aggregation, Protein Misfolding, Ubiquitination, SOD1, Aggresome, Ataxin-3

Abstract

Polyubiquitination of misfolded proteins, especially K63-linked polyubiquitination, is thought to be associated with the formation of inclusion bodies. However, it is not well explored whether appropriate editing of the different types of ubiquitin linkages by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) affects the dynamics of inclusion bodies. In this study, we report that a specific DUB, ataxin-3, is required for the efficient recruitment of the neurodegenerative disease-associated protein copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) to aggresomes. The overexpression of ataxin-3 promotes mutant SOD1 aggresome formation by trimming K63-linked polyubiquitin chains. Moreover, knockdown of ataxin-3 decreases mutant SOD1 aggresome formation and increases cell death induced by mutant SOD1. Thus, our data suggest that the sequestration of misfolded SOD1 into aggresomes, which is driven by ataxin-3, plays an important role in attenuating protein misfolding-induced cell toxicity.

Introduction

The diseases associated with protein misfolding and aggregation are recognized as “conformational diseases” and include neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer disease (AD), Parkinson disease (PD), Huntington disease (HD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The common feature of these diseases is the tendency of misfolded protein to form aggregates (1).

Misfolded proteins can be refolded by molecular chaperones or cleared by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) or by macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) (2). However, if the protein quality control system fails to repair or clear the abnormal polypeptides and aggregated proteins, cells have an alternative deposition method: they can sequester aggregates by collecting them at the microtubule organizing center (MTOC).3 This process is dependent on microtubule-based transport to generate a large inclusion body called an aggresome at the perinuclear region (3, 4). Aggresome formation is considered to be a protective process by which the cell handles unwanted toxic species (2, 4). Interestingly, inclusion bodies that are associated with certain of the above-mentioned diseases, such as Lewy bodies in PD and inclusions of copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) in ALS, appear likely to form aggresomes (5–9). SOD1 is a ubiquitously expressed protein whose mutation is linked to the development of ALS (10). Studies have shown that mutant SOD1 can be delivered to aggresomes through a microtubule-dependent pathway (9, 11). Moreover, interactions between mutant SOD1 and the dynein motor complex play an important role in aggresome formation (12, 13).

Post-translational modification with polyubiquitin serves diverse cellular roles. Linking adjacent ubiquitin molecules through different lysine residues creates different forms of polyubiquitin, and those forms have different roles. The lysine 48 (K48)-linked polyubiquitin chain, the best understood form of polyubiquitin, is employed by UPS degradation; other linkages have distinct functions independent of proteolysis. For example, K63-linked polyubiquitin has been shown to mediate protein kinase activation, DNA repair, vesicle trafficking and autophagy (14–18). Interestingly, K63-linked polyubiquitin is associated with aggresome formation in PD. It was shown that the E3 ubiquitin ligase parkin can promote K63-linked polyubiquitination of synphilin-1 and mutant DJ-1, increasing their recruitment to aggresomes (19–21).

Ubiquitination is a reversible covalent modification, and the state of substrate ubiquitination depends on the balance between the effects of ubiquitinating enzymes and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) (22, 23). There are nearly 100 DUBs with multiple roles in human cells. One of these, the polyglutamine (polyQ)-containing protein ataxin-3, is a ubiquitin-specific cysteine protease belonging to the Josephin family (24). Ataxin-3 deubiquitinates proteins by binding to polyubiquitin chains containing four or more ubiquitin molecules through the ubiquitin interaction motif (UIM) near its polyQ tract; it then edits the chains using its N-terminal catalytic Josephin domain (25, 26). Ataxin-3 was first reported to bind to K48-linked polyubiquitin chains and to act as a component in the delivery of ubiquitinated substrates to the proteasome (24, 27). Later, it was shown that ataxin-3 could regulate aggresome formation and bind to dynein motor complexes (28). Interestingly, it was reported recently that ataxin-3 preferentially edits K63-linked polyubiquitin chains (29). Although the editing of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains might be an important cellular process associated with aggresome formation in neurodegenerative diseases, the role of ataxin-3 in this process is still largely unknown.

In this study, we show that ataxin-3 promotes the recruitment of mutant SOD1 to the aggresome. The formation of SOD1 aggresomes depends on ataxin-3 DUB activity and is mediated by ataxin-3 editing of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains on mutant SOD1 proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Constructs

Ataxin-3 (ataxin-3–20Q), SOD1, ubiquitin, p62, and LC3 constructs were described previously (30–33). The point mutation in Flag-tagged ataxin-3 (C14A) was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the MutanBEST kit (Takara) and the following primers: 5′-gctgctcaacattgcctgaataac-3′ and 5′-aagtgagccttcttgtttctcgtg-3′. Flag-HDAC6 was obtained from Dr. Zhou Wang (University of Pittsburgh). All of the constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human embryonic kidney 293 (293) cells, mouse neuroblastoma (N2a) cells or mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) containing 10% newborn calf serum (Invitrogen). The cells were transfected with either expression vectors or siRNAs using Lipofectamine 2000 or Oligofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) at ∼40% confluence in DMEM without serum. MG132 was purchased from Calbiochem. Bafilomycin A1 (Baf) was purchased from Fermentek Ltd. Nocodazole and 3-methyladenine (3-MA) were purchased from Sigma.

Immunoblot Analysis and Antibodies

Cells were lysed in a lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitor (Roche), and then the proteins were separated by either 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore). To prepare the detergent-soluble and insoluble fractions, the cell lysates were centrifuged at 14,500 × g for 30 min at 4 °C.

The following primary antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal antibodies against FLAG (Sigma), GAPDH (Chemicon), GFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), HA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), tubulin (Sigma), and γ-tubulin (Sigma), as well as rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Beclin-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and LC3 (Novus Biologicals, Inc.). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against GFP and SOD1 were described previously (31, 34). A mouse monoclonal antibody against dynein was kindly provided by Dr. Jiawei Zhou (Institute of Neuroscience, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China). The secondary antibodies used were sheep anti-mouse IgG-HRP and anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Amersham Biosciences). The proteins were visualized using an ECL detection kit (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunoprecipitation

Crude cell lysates were sonicated in lysis buffer, and then the cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,500 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibodies in 0.01% BSA for 4 h at 4 °C. After incubation, protein G-Sepharose (Roche) was used for precipitation. The beads were washed with lysis buffer four or five times, and the proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer for immunoblot analysis.

Immunofluorescence

293 cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were treated with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 15 min, blocked using 4% FBS in PBS, incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody and then incubated with FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or Alexa Fluor-350-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen). The nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma). The cells were visualized using an IX71 inverted system microscope (Olympus).

RNA Interference

Double-stranded oligonucleotides designed against the region starting from nucleotide 143 of human or mouse ataxin-3 cDNA were synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The sequences of human ataxin-3 siRNA are 5′-TGGCAGAAGGAGGAGTTAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTAACTCCTCCTTCTGCCA-3′ (antisense). The sequences of mouse ataxin-3 siRNA are 5′-TGGCAGAAGGGGGAGTCAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTGACTCCCCCTTCTGCCA-3′ (antisense). A non-targeting oligonucleotide was used as a negative control. The transfection was performed with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Ataxin-3 Interacts with Mutant SOD1 and Promotes SOD1 Aggregation

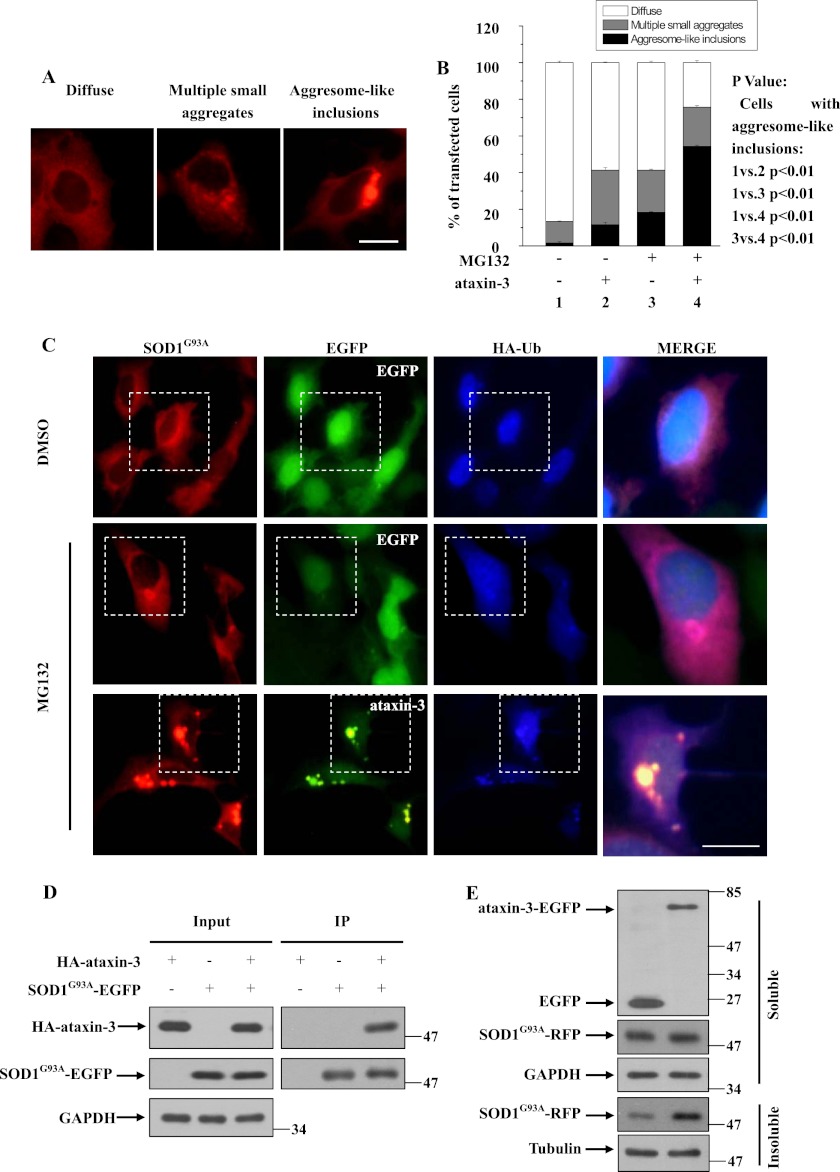

The DUB protein ataxin-3 can regulate aggresome formation (28), and mutant SOD1 can be recruited to aggresomes (9, 11). We wanted to determine whether ataxin-3 has a role in SOD1-associated aggresome formation. As we found that the aggregation of ALS-linked G93A mutant SOD1 (SOD1G93A) is stronger than wild type SOD1 (data not shown), we used SOD1G93A as a model protein. Overexpressed RFP-tagged SOD1G93A showed three distinct distribution patterns in 293 cells: diffusive cytoplasmic distribution, multiple small aggregates, and a few large inclusions (Fig. 1A). When the cells expressing SOD1G93A were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, the numbers of SOD1G93A multiple aggregates and aggresome-like inclusions were both increased. Interestingly, co-expression of EGFP-tagged ataxin-3 resulted in a dramatic increase in the formation of aggresome-like inclusions of RFP-tagged SOD1G93A (Fig. 1, B and C), but not RFP tag alone (data not shown). Using HA-tagged ataxin-3, we obtained similar results (data not shown). Notably, in 293 cells co-transfected with SOD1G93A, ataxin-3 and ubiquitin, SOD1 aggregates or aggresome-like inclusions were colocalized with ataxin-3 and ubiquitin (Fig. 1C). Because ataxin-3 co-localizes with mutant SOD1 aggregates and increases SOD1 aggregate formation, we performed co-immunoprecipitation assays to examine whether ataxin-3 interacts with mutant SOD1. In 293 cells co-transfected with HA-tagged ataxin-3 and EGFP-tagged SOD1G93A, HA-tagged ataxin-3 was co-immunoprecipitated with EGFP-tagged SOD1G93A but not with EGFP alone (Fig. 1D), suggesting that ataxin-3 can interact with mutant SOD1. Consistent with our observation that ataxin-3 increases SOD1 aggregate formation (Fig. 1C), we found that ataxin-3 selectively promoted the accumulation of SOD1G93A in the detergent-insoluble fraction but not in the soluble fraction (Fig. 1E).

FIGURE 1.

The effect of ataxin-3 on mutant SOD1 accumulation. A, 293 cells were transfected with SOD1G93A-RFP. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were visualized using an IX71 inverted system microscope. The scale bar indicates 10 μm. B, 293 cells were co-transfected with SOD1G93A-RFP and EGFP or EGFP-tagged ataxin-3. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were incubated for 12 h in the presence of DMSO or 10 μm MG132. The percentages of positively transfected cells containing diffuse distribution, small multiple aggregates and large inclusion bodies of SOD1G93A were quantified. The results are indicated as the means ± S.E. values from three independent transfection experiments. C, co-transfection was performed as in B, except that cells were additionally co-transfected with HA-ubiquitin. The cells were then subjected to immunofluorescence analysis using an HA antibody (blue). The colocalization of SOD1G93A, ataxin-3, and ubiquitin is indicated by the dotted white boxes. The right panel is a merged high-magnification view of the area boxed in dotted white. The scale bar indicates 10 μm. D, 293 cells were co-transfected with EGFP or SOD1G93A-EGFP and HA or HA-tagged ataxin-3 and, then treated with 10 μm MG132 for 12 h. The supernatants of the cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation analysis using rabbit polyclonal antibodies against GFP. The inputs (supernatant samples) and immunoprecipitants were then subjected to immunoblot analysis using antibodies to GAPDH, HA, and GFP. GAPDH served as a loading control. E, N2a cells were co-transfected with RFP-tagged SOD1G93Aand EGFP or EGFP-tagged ataxin-3 and then incubated with 10 μm MG132 for 12 h. The lysates from the cells were separated into detergent-soluble and detergent-insoluble fractions and subjected to immunoblot analysis using antibodies to GAPDH, GFP, SOD1, and tubulin.

Ataxin-3-driven Mutant SOD1 Aggresome Formation Is Microtubule-dependent

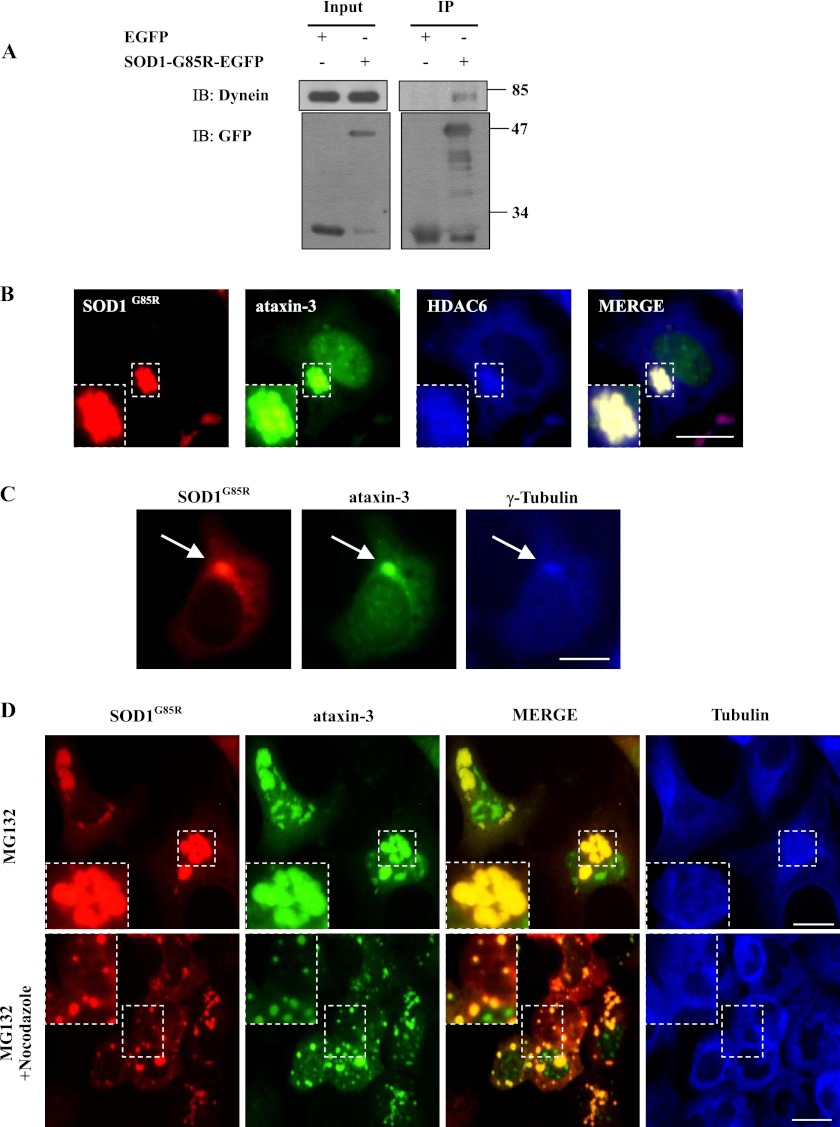

It is well known that histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) regulates aggresome formation by anchoring ubiquitinated proteins to the dynein motor complex, which transports proteins on microtubules to the MTOC to form aggresomes (35). As the morphology of the perinuclear SOD1 inclusions resembled that of aggresomes (Fig. 1, A and C), we performed immunoblot and immunofluorescence analyses to examine whether these large ataxin-3-driven SOD1 inclusions are aggresomes. In 293 cells treated with MG132, we found that another ALS-linked G85R mutant SOD1 (SOD1G85R) interacted with dynein (Fig. 2A). Moreover, SOD1G85R, ataxin-3 and HDAC6 as well as γ-tubulin were co-localized onto these large inclusions (Fig. 2, B and C), suggesting that these inclusions are aggresomes. In cells treated with MG132, ataxin-3 and SOD1G85R-containing inclusions were surrounded by tubulin, indicating that they localized at the microtubule organizing center. To determine whether ataxin-3 associates with mutant SOD1 before moving to the MTOC, we used nocodazole to depolymerize microtubule network. Depolymerizing microtubule led to a wide dispersion of the inclusions into multiple small aggregates, considered to be pre-aggresomal particles, and to the co-localization of ataxin-3 and SOD1G85R (Fig. 2D). The latter observation suggests that ataxin-3 targets mutant SOD1 prior to its transport to aggresomes at the MTOC.

FIGURE 2.

Colocalization of mutant SOD1 and ataxin-3 in aggresomes. A, 293 cells were transfected with EGFP or SOD1G85R-EGFP and treated with 10 μm MG132 for 12 h. The supernatants of the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against GFP. The inputs and immunoprecipitants were then subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. B, 293 cells were co-transfected with RFP-tagged SOD1G85R, EGFP-tagged ataxin-3, and Flag-tagged HDAC6. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were incubated with 10 μm MG132 for 12 h. The cells were then subjected to immunofluorescence analysis using a Flag antibody (blue). The scale bar indicates 10 μm. C, 293 cells were co-transfected with RFP-tagged SOD1G85R and EGFP-tagged ataxin-3. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were incubated with 10 μm MG132 for 12 h and then subjected to immunofluorescence analysis using a γ-tubulin antibody (blue). The scale bar indicates 10 μm. D, 293 cells were co-transfected with SOD1G85R-RFP and EGFP-tagged ataxin-3. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were treated with 10 μm MG132 or a combination of 10 μm MG132 and 5 μg/ml nocodazole for 12 h. The cells were subsequently processed for immunofluorescence with an anti-α-tubulin antibody. The scale bar indicates 10 μm.

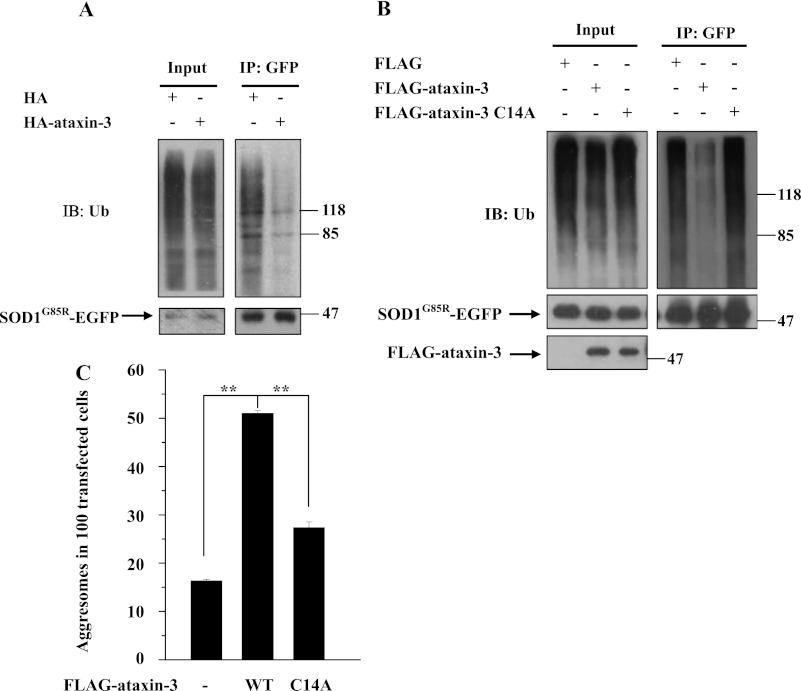

DUB Activity of Ataxin-3 Is Critical for Mutant SOD1 Aggresome Formation

As ataxin-3 functions as a DUB, to determine whether ataxin-3 could remove polyubiquitin from mutant SOD1, we transfected 293 cells with ataxin-3 and SOD1G85R and then used immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting to detect ubiquitination of SOD1G85R. In cells co-expressing ataxin-3, the SOD1 polyubiquitination level was dramatically decreased (Fig. 3A). However, the SOD1 polyubiquitination level was increased in cells co-expressing a catalytic cysteine residue mutant ataxin-3 (C14A) that has diminished DUB activity compared with cells co-expressing wild-type ataxin-3 (Fig. 3B). Using immunofluorescence, we observed that the C14A mutant failed to promote SOD1 aggresome formation (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these data suggest that ataxin-3 promotes mutant SOD1 aggresome formation by editing the ubiquitin chains of mutant SOD1 in a DUB activity-dependent manner.

FIGURE 3.

Ataxin-3-mediated aggresome formation by mutant SOD1 depends on ataxin-3 DUB activity. A, 293 cells were co-transfected with SOD1G85R-EGFP and HA or HA-ataxin-3, then treated with 10 μm MG132 for 12 h. The supernatants of the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against GFP. The inputs and immunoprecipitants were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-GFP or anti-Ub (ubiquitin) antibodies. B, 293 cells were co-transfected with SOD1G85R-EGFP and Flag tag, Flag-tagged ataxin-3 or Flag-tagged ataxin-3-C14A. After incubation with 10 μm MG132 for 12 h, the supernatants of the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against GFP. The inputs and immunoprecipitants were subjected to immunoblot analysis using antibodies to Flag, GFP, and Ub (ubiquitin). C, 293 cells were co-transfected with RFP-tagged SOD1G93A and Flag-BAP (as a control), Flag-ataxin-3 or Flag-ataxin-3-C14A. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were incubated with 10 μm MG132 for 12 h. The cells were then subjected to immunofluorescence analysis using a Flag antibody, and the percentages of positively transfected cells containing SOD1G93A aggresomes in Fig. 3C were quantified. The results are indicated as the means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA.

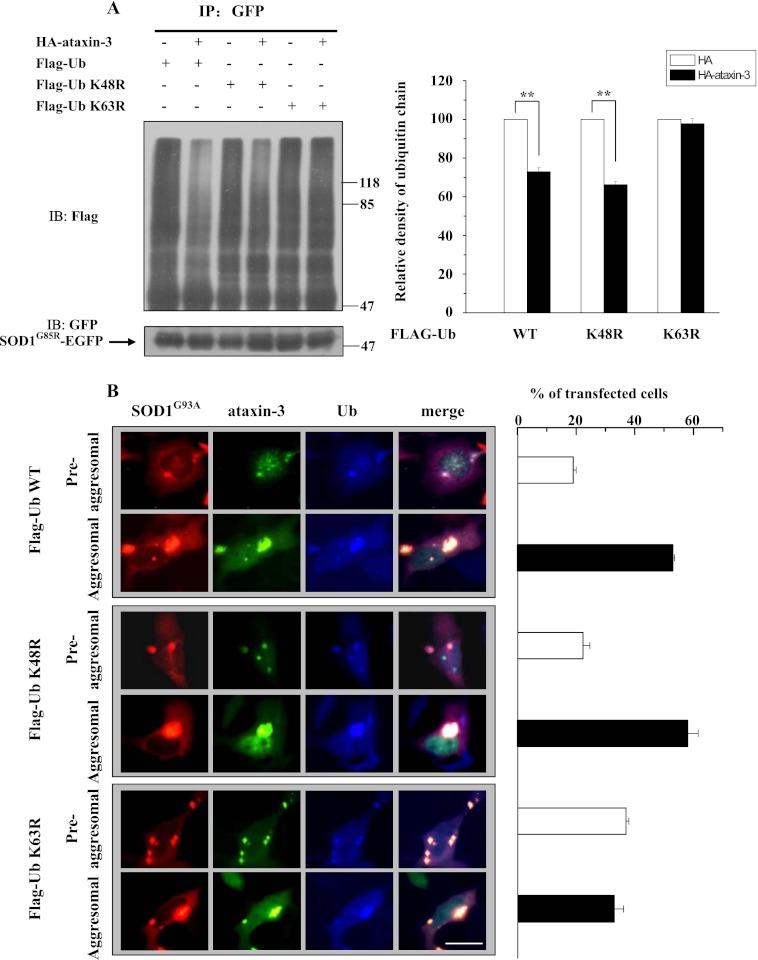

Ataxin-3 Promotes the Formation of Mutant SOD1 Aggresomes by Editing K63-linked Polyubiquitin Chains

To determine which type of ubiquitin linkages on mutant SOD1 are regulated by ataxin-3, we examined K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitin levels of mutant SOD1 in the presence of ataxin-3. We created two Flag-tagged mutant ubiquitins (K48R and K63R) and transfected them, along with EGFP-tagged SOD1G85R and HA-tagged ataxin-3, respectively, into 293 cells. The cells were treated with MG132, and then the cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analyses. Ataxin-3 edited wild-type and K48R ubiquitin-linked polyubiquitin chains that were conjugated to SOD1G85R (Fig. 4A). However, ataxin-3 failed to change the SOD1G85R conjugated polyubiquitin levels when K63 was mutated (Fig. 4A), indicating that ataxin-3 preferentially cleaves K63-linked polyubiquitin chains on SOD1.

FIGURE 4.

Ataxin-3 regulates aggresome formation by mutant SOD1 through editing K63-linked polyubiquitin chains. A, lysates from 293 cells co-transfected with SOD1G85R-EGFP, Flag-tagged ubiquitin mutants and HA or HA-ataxin-3 were subjected to immunoprecipitation and then analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. The quantified data are shown on the right side. The results are indicated as the means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA. B, 293 cells co-expressing RFP-tagged SOD1G93A, GFP-tagged ataxin-3, and Flag-tagged ubiquitin mutants were incubated with 10 μm MG132 for 12 h. The cells were then fixed and immunostained with an antibody against Flag (blue). The scale bar indicates 10 μm. The percentages of positively transfected cells containing mutant SOD1 aggresomes and aggregates were quantified. The results are indicated as the means ± S.E.

To determine the relative contributions of various ubiquitin linkages to ataxin-3-mediated SOD1 aggresome formation, we examined the aggresome formation in cells co-transfected with SOD1G93A, ataxin-3, and K48R or K63R mutant ubiquitin. In positively transfected cells expressing K48R mutant ubiquitin, ∼58% of the cells contained aggresomes, whereas 22% contained aggregates, which is similar to the percentages in cells co-transfected with wild-type ubiquitin (∼53% contain aggresomes and 19% contain aggregates). However, cells positively co-transfected with K63R mutant ubiquitin exhibited dramatically reduced aggresome formation and increased aggregate formation (∼33% of the cells contained aggresomes, whereas 37% contained aggregates) (Fig. 4B). The quantification of the percentages of visible aggresome- and aggregate-containing cells is shown in the right panel of Fig. 4B. These results suggest that ataxin-3 promotes misfolded SOD1 aggresome formation by specifically editing K63-linked polyubiquitin chains on SOD1.

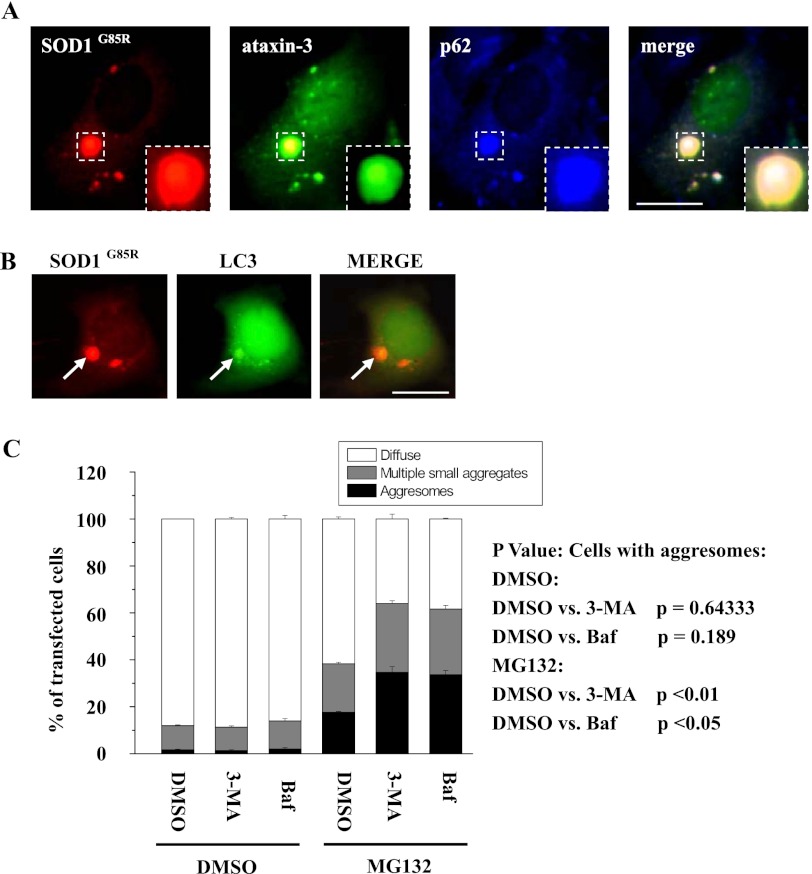

Autophagic Recognition of Ataxin-3-induced Mutant SOD1 Aggresomes

Growing evidence suggests that aggresomes can potentially be disposed of through autophagy (4). To determine whether ataxin-3-induced mutant SOD1 aggresomes are susceptible to autophagy, we performed immunofluorescence analysis to assess whether these aggresomes could be recognized by the autophagy receptor p62 (also called SQSTM1) and whether they are co-localized with the autophagosomal marker LC3. In transfected 293 cells, SOD1G85R aggresomes indeed colocalized with p62 and LC3 (Fig. 5, A and B). Moreover, in cells treated with MG132 in combination with the autophagy inhibitors 3-MA or Baf, aggresome formation by mutant SOD1 was significantly increased (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Ataxin-3 targets mutant SOD1 to aggresomes to with autophagic activity. A, 293 cells co-expressing RFP-tagged SOD1G85R, EGFP-tagged ataxin-3 and Flag-tagged p62 were incubated in 10 μm MG132 for 12 h. The cells were then fixed and stained with an antibody against Flag (blue). The scale bar indicates 10 μm. B, 293 cells were co-transfected with SOD1G85R-RFP and GFP-tagged LC3. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were stained with 0.05 mm MDC for 10 min and visualized using a microscope. The scale bar indicates 10 μm. C, 293 cells were transfected with SOD1G85R-RFP. Twelve hours after transfection, the cells were treated with 10 mm 3-MA or DMSO, then after 60 h, the cells were incubated with or without 10 μm MG132 or 0.1 μm Baf for another 12 h. The percentages of positively transfected cells containing diffuse distribution, small multiple aggregates, and aggresomes of SOD1G93A were quantified. The results are indicated as the means ± S.E. values from three independent transfection experiments.

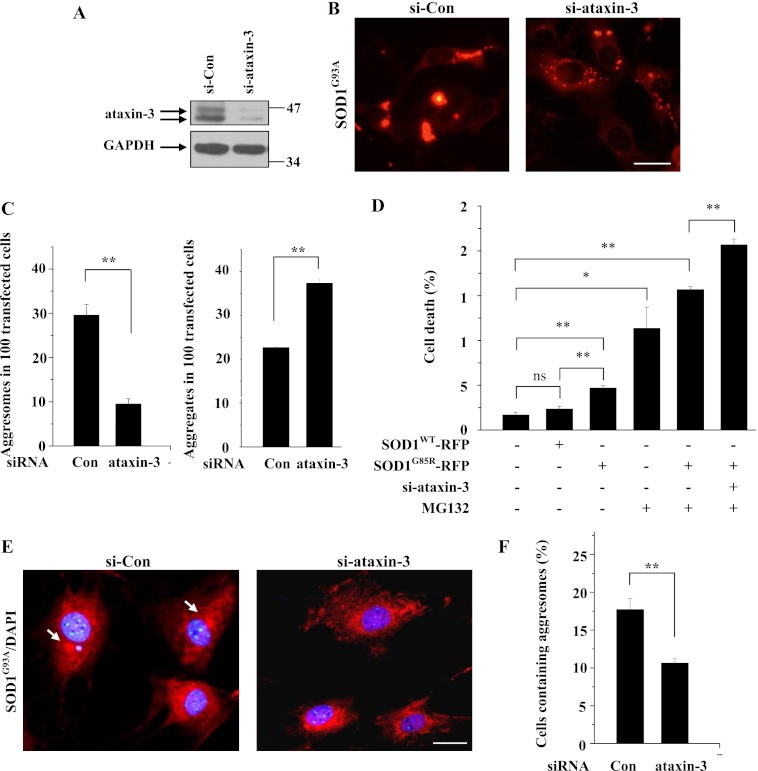

Endogenous Cellular Ataxin-3 Targets Mutant SOD1 to Aggresomes and Protects Cells against Mutant SOD1-triggered Cell Death

To further explore the role of ataxin-3 in SOD1 aggresome formation, we performed knockdown experiments to examine the effects of endogenous ataxin-3 on mutant SOD1 aggresome formation. We first examined the knockdown efficiency of ataxin-3 siRNA, showing that endogenous ataxin-3 levels were dramatically decreased after transfection of si-ataxin-3 in 293 cells (Fig. 6A). In ataxin-3-knockdown cells, SOD1G93A formed many fewer aggresomes but many more widely dispersed small pre-aggresomal aggregates after MG132 treatment (Fig. 6, B and C). Moreover, under MG132 treatment, knockdown of ataxin-3 increased the cell death in cells transfected with SOD1G93A (Fig. 6D), whereas overexpression of ataxin-3decreased the cell death induced by SOD1G93A (data not shown), indicating that ataxin-3 protects cells against mutant SOD1-induced cytotoxicity. We next tested the effect of ataxin-3-knockdown on SOD1 aggresome formation in MEF cells from SOD1G93A transgenic mice (E14). In those cells, knockdown efficiency of ataxin-3 was confirmed similarly as that in 293 cells (data not shown). Knockdown of ataxin-3 resulted in a decrease in mutant SOD1G93A aggresomes (Fig. 6, E and F), further suggesting that ataxin-3 is critical for mutant SOD1 aggresome formation in cultured cells from ALS mice.

FIGURE 6.

Endogenous ataxin-3 regulates SOD1 aggresome formation and protects cells against toxicity induced by mutant SOD1. A, 293 cells were transfected with siRNA against human ataxin-3 or with negative control siRNA for 72 h. The cells were then incubated in 10 μm MG132 for 12 h. The supernatants of the cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. B, 293 cells were co-transfected with SOD1G93A-RFP and siRNA against human ataxin-3 or negative control siRNA. Seventy-two hours after transfection, the cells were treated with 10 μm MG132 for 16 h, after which the cells were fixed and visualized. The scale bar indicates 10 μm. C, percentages of positively transfected cells containing mutant SOD1 aggresomes and aggregates were quantified. The results are indicated as the means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA. D, 293 cells were co-transfected with SOD1WT-RFP or SOD1G85R-RFP and si-ataxin-3 or negative control siRNA for 72 h. The cells were then incubated for 12 h in the presence or absence of 10 μm MG132 and subsequently stained with DAPI to visualize the nuclear morphology. Cell death was revealed by nuclear condensation and fragmentation with DAPI staining. The dead cells were counted and quantified. The results are indicated as the means ± S.E. ns, not significantly different; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA. E, MEF cells from SOD1G93A transgenic mice (E14) were subjected to an ataxin-3-knockdown experiment using siRNA against mouse ataxin-3. Seventy-two hours later, the cells were treated with 10 μm MG132 for 12 h and then subjected to immunofluorescence using SOD1 antibodies and stained with DAPI. The arrows in the merged pictures show the aggresomes. The scale bar indicates 10 μm. F, percentages of positively transfected cells containing mutant SOD1 aggresomes were quantified. The results are indicated as the means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA.

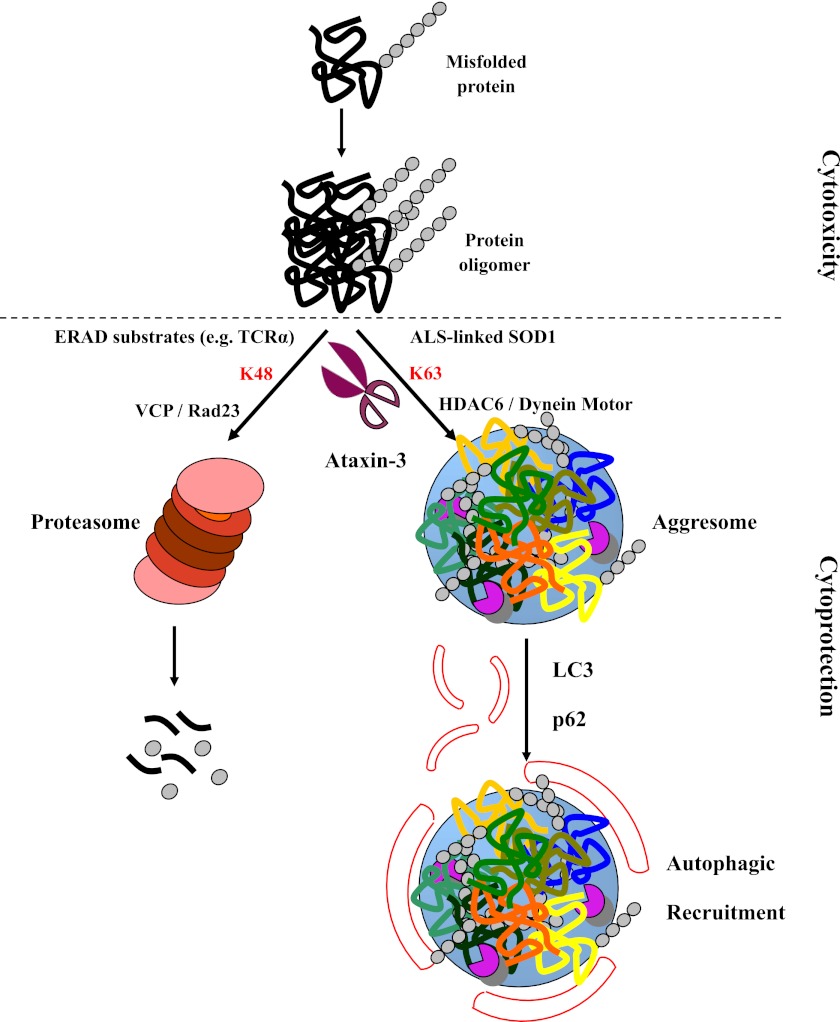

DISCUSSION

The quality control of proteins that are mediated by different types of ubiquitin chains is important for cells to maintain homeostasis. In our study, we show that the cleavage of K63-linked ubiquitin chains by the DUB enzyme ataxin-3 can promote aggresome formation, thus protecting cells against toxic effects induced by protein misfolding (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

A schematic model of ataxin-3-mediated deubiquitination for the deposit of misfolded proteins. Normally, misfolded proteins are polyubiquitinated by K48-linked ubiquitin chains and targeted to the proteasome. Ataxin-3 edits the K48 linkages to ensure the proteasome-mediated clearance of these misfolded proteins. When the proteasome is impaired, ataxin-3 participates in the K63-linked polyubiquitination of misfolded proteins, such as mutant SOD1, after which the misfolded proteins are retro-transported to aggresomes that are recognized by the autophagy machinery.

Misfolded SOD1 was shown to be ubiquitinated by several E3 ubiquitin ligases and degraded by the proteasome (31, 36, 37). This process is thought to be mediated mainly by the K48-linked polyubiquitination signal. However, when we provided MG132 treatment to mimic proteasomal impairment under pathological conditions, misfolded SOD1 was transported to aggresomes in association with a K63-linked ubiquitin signal. This finding indicates that under pathological conditions, when the ubiquitin-proteasome route is overwhelmed, K63-linked polyubiquitination may direct misfolded proteins to the ubiquitin-aggresome route.

Recent studies showed that aggresome or inclusion body formation of other neurodegenerative disease-associated proteins, such as synphilin-1 and tau, depends on K63-linked polyubiquitination (17, 20, 21). It is likely that the formation of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains acts as a signal for interaction with the key regulator HDAC6 and thus couples the misfolded proteins to the dynein motor complex for transport to aggresomes (19). Interestingly, whereas previous studies showed that increasing K63-linked polyubiquitination promotes aggresome formation, our data indicate that deubiquitination of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains by ataxin-3 has similar effects. It is therefore possible that DUB enzymes, such as ataxin-3, may edit K63-linked polyubiquitin chains to the exact levels that allow them to associate with crucial components in the aggresome formation pathway. As completely deubiquitinated misfolded substrates have no ability to interact with K63-linked polyubiquitin binding proteins, this idea suggests that ataxin-3 may function as an “editing barber” to shorten the long polyubiquitin chains rather than to merely remove those chains, consistent with the fact that ataxin-3-mediated ubiquitin chain removal is preferential for longer ubiquitin chains (28).

Similarly, as shown in Fig. 6, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) substrates are polyubiquitinated and subsequently deubiquitinated by ataxin-3 to ensure their degradation by the proteasome (27), suggesting that DUBs such as ataxin-3 could act as a “barber” to maintain the proper length of the polyubiquitin chains on client proteins and thereby determine their fates. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that a balance of chain-extending (ubiquitination) and chain-trimming (deubiquitination) activities is required for proper proteasomal quality control (38, 39), further supporting the notion that the balance of ubiquitination and deubiquitination might be critical for many cellular pathways.

Notably, we did not observe a difference between wild-type and pathogenic polyQ-expanded ataxin-3 on the regulation of SOD1 aggresome formation (data not shown). As polyQ-containing proteins, wild-type and polyQ-expanded ataxin-3 exhibit no obvious difference in binding to the polyubiquitinated substrates (25). Although pathogenic ataxin-3 cleaves short ubiquitin chains more efficiently (28), wild-type and pathogenic ataxin-3 show no difference in the ability to cleave K63-linked polyubiquitin chains (29). Taken together with our other observations, we hypothesize that the role of ataxin-3 in SOD1 aggresome formation is polyQ-length independent.

Increasing evidence indicates that aggresome formation promotes the delivery of pathological protein aggregates to autophagy machinery (40). In our observations, ataxin-3-mediated selective sequestration of misfolded SOD1 to aggresomes allows for selective autophagic recognition of mutant SOD1 by p62 and LC3, similar to the observations in a previous mutant Htt study by Iwata et al. (41); this result suggests that aggresomes of ALS-linked mutant SOD1, as well as those of other neurodegenerative disease-associated proteins, including HD-linked mutant Htt and AD-linked mutant tau (40), are targeted by the autophagy pathway.

More than 100 mutations in the SOD1 gene have been found in familial ALS, and it is widely believed that mutant SOD1 has a toxic gain-of-function rather than a loss-of function effect in ALS. A common feature, shared by studies in cultured cells, transgenic animals and human patients, is the appearance of ubiquitinated detergent-insoluble SOD1 inclusions. Whether protein inclusions in ALS and other neurodegenerative disorders are protective or toxic is still an open question. Studies suggest that the micro-intermediate aggregates/oligomers generated during the dynamic process of protein aggregation potentially exert toxic effects and that the sequestration of these oligomers into inclusion bodies, such as aggresomes, may protect cells against these toxic species, potentially through autophagic recognition (2, 42–44). Our data show that co-expression of ataxin-3 robustly promotes mutant SOD1 aggresome formation and causes a decrease in cell toxicity, whereas knockdown of ataxin-3 results in the disruption of mutant SOD1 aggresomes but the formation of small aggregates (considered to be pre-aggresomal structures), and causes an increase in cell toxicity (Figs. 1 and 6). This observation suggests that ataxin-3 exerts a protective role against misfolded SOD1-induced toxicity by sequestering SOD1 to aggresomes. As aggresome-like SOD1 inclusions have been found in an ALS mouse model (8), it would be beneficial to investigate the role of ataxin-3 in SOD1 aggresome formation using ALS mice and ataxin-3 transgenic mice in future studies.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that ataxin-3 is a DUB enzyme that edits K63-linked polyubiquitin chains conjugated to mutant SOD1 and regulates mutant SOD1 aggresome formation. Thus, our study provides a previously unrecognized mechanism for the formation of mutant SOD1 aggresomes through the deubiquitination of K63-linked polyubiquitin.

This work was supported in part by the National High-tech Research and Development Program of China 973 (Project 2011CB504102), the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (No. 30970921 and 31000473), and a Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

- MTOC

- deubiquitinating enzyme

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- siRNA

- small interference RNA

- ERAD

- endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

- DUB

- deubiquitinating enzyme

- SOD

- superoxide dismutase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kopito R. R., Ron D. (2000) Conformational disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, E207–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ross C. A., Poirier M. A. (2005) Opinion: What is the role of protein aggregation in neurodegeneration? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 891–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnston J. A., Ward C. L., Kopito R. R. (1998) Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1883–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kopito R. R. (2000) Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 524–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olanow C. W., Perl D. P., DeMartino G. N., McNaught K. S. (2004) Lewy-body formation is an aggresome-related process: a hypothesis. Lancet Neurol. 3, 496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miki Y., Mori F., Tanji K., Kakita A., Takahashi H., Wakabayashi K. (2011) Neuropathology 31, 561–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Waelter S., Boeddrich A., Lurz R., Scherzinger E., Lueder G., Lehrach H., Wanker E. E. (2001) Accumulation of mutant huntingtin fragments in aggresome-like inclusion bodies as a result of insufficient protein degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 1393–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bruijn L. I., Becher M. W., Lee M. K., Anderson K. L., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G., Sisodia S. S., Rothstein J. D., Borchelt D. R., Price D. L., Cleveland D. W. (1997) ALS-linked SOD1 mutant G85R mediates damage to astrocytes and promotes rapidly progressive disease with SOD1-containing inclusions. Neuron 18, 327–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corcoran L. J., Mitchison T. J., Liu Q. (2004) A novel action of histone deacetylase inhibitors in a protein aggresome disease model. Curr. Biol. 14, 488–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosen D. R., Siddique T., Patterson D., Figlewicz D. A., Sapp P., Hentati A., Donaldson D., Goto J., O'Regan J. P., Deng H. X. (1993) Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 362, 59–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnston J. A., Dalton M. J., Gurney M. E., Kopito R. R. (2000) Formation of high molecular weight complexes of mutant Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase in a mouse model for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 12571–12576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ström A. L., Shi P., Zhang F., Gal J., Kilty R., Hayward L. J., Zhu H. (2008) Interaction of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-related mutant copper-zinc superoxide dismutase with the dynein-dynactin complex contributes to inclusion formation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22795–22805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gamerdinger M., Kaya A. M., Wolfrum U., Clement A. M., Behl C. (2011) EMBO Rep. 12, 149–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deng L., Wang C., Spencer E., Yang L., Braun A., You J., Slaughter C., Pickart C., Chen Z. J. (2000) Activation of the IκB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell 103, 351–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiu R. K., Brun J., Ramaekers C., Theys J., Weng L., Lambin P., Gray D. A., Wouters B. G. (2006) Lysine 63-polyubiquitination guards against translesion synthesis-induced mutations. PLoS Genet 2, e116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lauwers E., Jacob C., André B. (2009) K63-linked ubiquitin chains as a specific signal for protein sorting into the multivesicular body pathway. J. Cell Biol. 185, 493–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tan J. M., Wong E. S., Kirkpatrick D. S., Pletnikova O., Ko H. S., Tay S. P., Ho M. W., Troncoso J., Gygi S. P., Lee M. K., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M., Lim K. L. (2008) Lysine 63-linked ubiquitination promotes the formation and autophagic clearance of protein inclusions associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Adhikari A., Chen Z. J. (2009) Diversity of polyubiquitin chains. Dev. Cell 16, 485–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Olzmann J. A., Li L., Chudaev M. V., Chen J., Perez F. A., Palmiter R. D., Chin L. S. (2007) Parkin-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination targets misfolded DJ-1 to aggresomes via binding to HDAC6. J. Cell Biol. 178, 1025–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lim K. L., Chew K. C., Tan J. M., Wang C., Chung K. K., Zhang Y., Tanaka Y., Smith W., Engelender S., Ross C. A., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M. (2005) Parkin mediates nonclassical, proteasomal-independent ubiquitination of synphilin-1: implications for Lewy body formation. J. Neurosci. 25, 2002–2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lim K. L., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M. (2006) Parkin-mediated lysine 63-linked polyubiquitination: a link to protein inclusions formation in Parkinson's and other conformational diseases? Neurobiol. Aging 27, 524–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Komander D., Clague M. J., Urbé S. (2009) Breaking the chains: structure and function of the deubiquitinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 550–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reyes-Turcu F. E., Ventii K. H., Wilkinson K. D. (2009) Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 363–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chai Y., Berke S. S., Cohen R. E., Paulson H. L. (2004) Poly-ubiquitin binding by the polyglutamine disease protein ataxin-3 links its normal function to protein surveillance pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3605–3611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burnett B., Li F., Pittman R. N. (2003) The polyglutamine neurodegenerative protein ataxin-3 binds polyubiquitylated proteins and has ubiquitin protease activity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 3195–3205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berke S. J., Chai Y., Marrs G. L., Wen H., Paulson H. L. (2005) Defining the role of ubiquitin-interacting motifs in the polyglutamine disease protein, ataxin-3. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32026–32034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Q., Li L., Ye Y. (2006) Regulation of retrotranslocation by p97-associated deubiquitinating enzyme ataxin-3. J. Cell Biol. 174, 963–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burnett B. G., Pittman R. N. (2005) The polyglutamine neurodegenerative protein ataxin 3 regulates aggresome formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 4330–4335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Winborn B. J., Travis S. M., Todi S. V., Scaglione K. M., Xu P., Williams A. J., Cohen R. E., Peng J., Paulson H. L. (2008) The deubiquitinating enzyme ataxin-3, a polyglutamine disease protein, edits Lys63 linkages in mixed linkage ubiquitin chains. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26436–26443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu C., Fei E., Jia N., Wang H., Tao R., Iwata A., Nukina N., Zhou J., Wang G. (2007) Assembly of lysine 63-linked ubiquitin conjugates by phosphorylated alpha-synuclein implies Lewy body biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14558–14566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ying Z., Wang H., Fan H., Zhu X., Zhou J., Fei E., Wang G. (2009) Gp78, an ER associated E3, promotes SOD1 and ataxin-3 degradation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 4268–4281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fei E., Jia N., Yan M., Ying Z., Sun Q., Wang H., Zhang T., Ma X., Ding H., Yao X., Shi Y., Wang G. (2006) SUMO-1 modification increases human SOD1 stability and aggregation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347, 406–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ren H., Fu K., Mu C., Li B., Wang D., Wang G. (2010) Cancer Lett. 297, 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ying Z., Wang H., Fan H., Wang G. (2011) The endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation system regulates aggregation and degradation of mutant neuroserpin. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20835–20844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kawaguchi Y., Kovacs J. J., McLaurin A., Vance J. M., Ito A., Yao T. P. (2003) The deacetylase HDAC6 regulates aggresome formation and cell viability in response to misfolded protein stress. Cell 115, 727–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Niwa J., Ishigaki S., Hishikawa N., Yamamoto M., Doyu M., Murata S., Tanaka K., Taniguchi N., Sobue G. (2002) Dorfin ubiquitylates mutant SOD1 and prevents mutant SOD1-mediated neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36793–36798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Urushitani M., Kurisu J., Tateno M., Hatakeyama S., Nakayama K., Kato S., Takahashi R. (2004) CHIP promotes proteasomal degradation of familial ALS-linked mutant SOD1 by ubiquitinating Hsp/Hsc70. J. Neurochem. 90, 231–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Crosas B., Hanna J., Kirkpatrick D. S., Zhang D. P., Tone Y., Hathaway N. A., Buecker C., Leggett D. S., Schmidt M., King R. W., Gygi S. P., Finley D. (2006) Ubiquitin chains are remodeled at the proteasome by opposing ubiquitin ligase and deubiquitinating activities. Cell 127, 1401–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ernst R., Mueller B., Ploegh H. L., Schlieker C. (2009) The otubain YOD1 is a deubiquitinating enzyme that associates with p97 to facilitate protein dislocation from the ER. Mol. Cell 36, 28–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wong E. S., Tan J. M., Soong W. E., Hussein K., Nukina N., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M., Cuervo A. M., Lim K. L. (2008) Autophagy-mediated clearance of aggresomes is not a universal phenomenon. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 2570–2582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Iwata A., Riley B. E., Johnston J. A., Kopito R. R. (2005) HDAC6 and microtubules are required for autophagic degradation of aggregated huntingtin. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40282–40292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Taylor J. P., Tanaka F., Robitschek J., Sandoval C. M., Taye A., Markovic-Plese S., Fischbeck K. H. (2003) Aggresomes protect cells by enhancing the degradation of toxic polyglutamine-containing protein. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 749–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tanaka M., Kim Y. M., Lee G., Junn E., Iwatsubo T., Mouradian M. M. (2004) Aggresomes formed by α-synuclein and synphilin-1 are cytoprotective. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4625–4631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smith W. W., Liu Z., Liang Y., Masuda N., Swing D. A., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G., Troncoso J. C., Pletnikov M., Dawson T. M., Martin L. J., Moran T. H., Lee M. K., Borchelt D. R., Ross C. A. (2010) Synphilin-1 attenuates neuronal degeneration in the A53T α-synuclein transgenic mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 2087–2098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]