Abstract

A fundamental step in the life cycle of F. tularensis is bacterial entry into host cells. F. tularensis activates complement, and recent data suggest that the classical pathway is required for complement factor C3 deposition on the bacterial surface. Nevertheless, C3 deposition is inefficient and neither the specific serum components necessary for classical pathway activation by F. tularensis in nonimmune human serum, nor the receptors that mediate infection of neutrophils has been defined. Herein human neutrophil uptake of GFP-expressing F. tularensis strains LVS and Schu S4 was quantified with high efficiency by flow cytometry. Using depleted sera and purified complement components we demonstrated first that C1q and C3 were essential for F. tularensis phagocytosis whereas C5 was not. Second, we used purification and immuno-depletion approaches to identify a critical role for natural IgM in this process, and then used a wbtA2 mutant to identify LPS O-antigen and capsule as prominent targets of these antibodies on the bacterial surface. Finally, we demonstrate using receptor-blocking antibodies that CR1 (CD35) and CR3 (CD11b/CD18) acted in concert for phagocytosis of opsonized F. tularensis by human neutrophils, whereas CR3 and CR4 (CD11c/CD18) mediated infection of human monocyte-derived macrophages. Altogether, our data provide fundamental insight into mechanisms of F. tularensis phagocytosis and support a model whereby natural IgM binds to surface capsular and O-antigen polysaccharides of F. tularensis and initiates the classical complement cascade via C1q to promote C3-opsonization of the bacterium and phagocytosis via CR3 and either CR1 or CR4 in a phagocyte-specific manner.

Keywords: tularemia, phagocytosis, opsonization, classical complement pathway, receptor

INTRODUCTION

Francisella tularensis is a highly infectious Gram-negative bacterium and the causative agent of tularemia, a vector-borne zoonotic disease that affects a variety of small mammals and humans (1–3). The clinical presentation and severity of human tularemia is largely dependent upon the bacterial strain, dose and route of infection, and severe morbidity and mortality can follow this disease if untreated (1, 4). F. tularensis is most often transmitted by arthropod bites or by direct contact with infected animal tissues (4) but is most dangerous when acquired via the respiratory route, whereby inhalation of as few as 10 CFU can cause fulminant pneumonic disease, sepsis, and death (1). Consequently, F. tularensis was developed for use as a biological weapon and is currently classified as a category A Select Agent by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2, 4).

Two subspecies of this organism, Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis (type A) and Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica (type B) account for nearly all cases of human tularemia. Type A strains are highly virulent and are endemic to North America, whereas type B strains cause milder disease and are found throughout the Northern Hemisphere (5). Given the infectious nature of wild-type F. tularensis, the human-attenuated live vaccine strain (LVS) of F. tularensis subsp. holarctica has been widely utilized as a model organism for tularemia research. LVS is virulent in mice and retains many of the pathogenic phenotypes observed with virulent F. tularensis during in vitro infections of eukaryotic cells (2, 6–9).

Binding and entry into host cells is a fundamental step in the life cycle of an intracellular pathogen such as F. tularensis. Phagocytes express a repertoire of receptors that contribute to pathogen recognition and internalization. Depending on which receptors are engaged, phagocytosis can trigger different signaling pathways that ultimately influence trafficking of phagosomes, activation of microbial killing mechanisms, production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and the induction of cell death (10). Accordingly, Geier and Celli demonstrated that entry of the type A F. tularensis strain Schu S4 through different phagocytic receptors on murine macrophages affects the efficiency of phagosome escape and intracellular growth (11). Multiple receptors have been implicated in F. tularensis infection of macrophages including the mannose receptor (11–13), complement receptor 3 (CR3, CD11b/CD18) (11–14), scavenger receptor A (15), and nucleolin (16). Furthermore, CR3 and CR4 (CD11c/CD18) mediate F. tularensis LVS entry into human dendritic cells (17). Conversely, the receptors required for F. tularensis phagocytosis by neutrophils have not been characterized.

The complement system is comprised of more than 30 soluble and cell-surface proteins and has multiple effector functions in host defense, including opsonization of microbes to facilitate phagocytosis, the release of anaphylotoxins to promote inflammation, and direct damage or killing of microbes via the membrane attack complex (18, 19). Complement activation occurs through three distinct pathways. The classical pathway is typically activated in an immune host when complement protein C1q binds to IgM or IgG on microbe surfaces. C1q can also bind directly to some bacteria in the absence of Abs (20–25), to the acute-phase reactant C-reactive protein attached to bacterial phospholipids (26) or to natural IgM (27) , germline encoded Abs that comprise an inherited IgM repertoire and contribute to innate defense. On the other hand, the lectin pathway is initiated when mannose-binding lectin or ficolins engage certain carbohydrate structures on microbe surfaces (18, 19). Finally, the alternative pathway is activated directly when spontaneously generated C3b attaches to the surfaces of microbes that lack the necessary factors to inhibit this pathway once initiated (18, 19).

Previous studies indicate that complement opsonization enhances F. tularensis phagocytosis by macrophages (6, 11, 12, 14) and dendritic cells (17), and may be essential for infection of neutrophils (28). Despite this, some studies did not detect C3 on the bacterial surface or infection of neutrophils in the absence of immune serum (29, 30), whereas others reported infection of neutrophils when concentrations of nonimmune serum were increased to 10–20% (28, 31). More recently, Clay et al. detected C1q-dependent C3 deposition on wild-type F. tularensis, and identified a role for the LPS O-antigen in C3b inactivation (32). A role for the classical pathway in C3 deposition on F. tularensis was also reported by Ben Nasr and Klimpel (33). In addition, we reported limited C3 deposition on F. tularensis LVS relative to the related organism F. novicida (34). All these data are in keeping with the antiphagocytic nature of bacterial capsules (35), and a large body of data indicates that LPS O-antigen and capsular polysaccharides protect F. tularensis from the lytic effects of serum complement (2, 32, 33, 36–39). At the same time, how limited amounts of C3 confer uptake by neutrophils is not completely understood, and neither the specific serum components necessary for C1q-dependent complement activation by F. tularensis nor the phagocytic receptors engaged has been defined.

We undertook this study to define better the components of normal (nonimmune) human serum that augment F. tularensis infection of human neutrophils and to identify phagocytic receptors that are required for infection of these cells. Our data reveal a key role for natural IgM, but not IgG, in this process, which initiates the classical complement cascade via C1q to promote C3-dependent opsonization of F. tularensis LVS and Schu S4. We also show using a wbtA2 mutant that LPS O-antigen and capsule are prominent targets of natural IgM. Finally, we demonstrate that CR1 and CR3 act in concert during phagocytosis of opsonized F. tularensis by human neutrophils whereas CR4 is dispensable, and as such define additional differences between neutrophils and mononuclear phagocytes in their response to this organism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Cysteine heart agar and Bacto™ brain heart infusion were obtained from Becton, Dickinson and Company (Sparks, MD). Defibrinated sheep blood was from Remel (Lenexa, KS). Endotoxin-free Dulbecco’s PBS, HBSS, and HEPES buffer were acquired from Mediatech Incorporated (Manassas, VA). Spectinomycin and anti-human IgM agarose were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Clinical grade dextran (m.w. 500,000 Da) was purchased from Pharmacosmos A/S (Holbaek, Denmark). Ficoll-Paque Plus was obtained from GE Healthcare Bio-sciences (Uppsala, Sweden). Endotoxin-free HEPES-buffered RPMI-1640 medium (with and without phenol red) was from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). Human serum albumin (HSA), 25% was from Talecris Biotherapeutics (Research Triangle Park, NC). LEAF™ purified anti-CD11a (clone HI111), LEAF™ purified anti-CD11b (clone M1/70), LEAF™ purified anti-CD11c (clone 3.9), LEAF™ purified mouse IgG1 isotype control (clone MOPC-21), and LEAF™ purified rat IgG2b isotype control (clone RTK4530) were purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Anti-CD35 (clone J3D3) was from Acris Antibodies (San Diego, CA). Anti-F. tularensis antiserum was from BD Diagnostics (Sparks, MD). DyLight™ 488- and rhodamine-conjugated F(ab’)2 secondary Abs were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). DAPI and Pierce SuperSignal West Pico Enhanced Chemiluminescence substrate were from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL). Alexa Fluor®-488 E. coli BioParticles were from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR). C3-, C5-, and C1q-depleted human sera and purified C3, C3b, iC3b, C5, and C1q proteins were purchased from Complement Technology, Inc. (Tyler, TX). All chromatography matrices were acquired from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). Gel filtration standards and unlabeled control agarose were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris gels and Precision Plus molecular weight markers were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad,CA). Acqua Protein Gel stain was from Bulldog Bio (Portsmouth, NH). Purified human IgG and IgM electrophoresis standards were from Sigma-Aldrich and MP Biomedicals, LLC (Santa Ana, CA), respectively. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgM was from US Biological (Swampscott, MA). IRDye 680LT Donkey anti-Goat IgG was from LiCor Biosciences (Lincoln, NE). The MicroVue C3a Plus Enzyme Immunoassay was from Quidel (San Diego, CA).

Construction of sGFP plasmid

The “superfolder” GFP (sGFP) sequence was kindly provided by Dr. Alexander Horswill (University of Iowa) (40). The sGFP was PCR amplified using oligonucleotide primers designed with KpnI and PstI tails to facilitate cloning into the KpnI-PstI restriction sites of pTrc99A (41). Cloning resulted in the placement of sGFP downstream of the F. tularensis groES promoter in pTrc99A. The entire groES-sGFP expression cassette was PCR amplified using oligonucleotide primers with EcoRV and EcoRI tails and the amplicon was cloned into the EcoRV-EcoRI sites of pBB103 (41). The resulting plasmid was verified by restriction analysis and sequencing and was designated pBB103-sGFP.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Fully virulent, wild-type F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (type A) strain Schu S4 and the attenuated F. tularensis subsp. holarctica live vaccine strain (LVS) (ATCC 29684) have been described (7). An LVS Himar transposon mutant lacking functional wbtA2 (37) was the generous gift of Dara Frank (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI). All studies of the virulent type A strain were performed in a Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) facility with Select Agent approval and in accordance with all Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health regulatory and safety guidelines. F. tularensis LVS and Schu S4 constitutively expressing sGFP were generated by cryotransformation with pBB103-sGFP, and were designated LVS-sGFP and Schu S4-sGFP. Brain Heart Infusion Broth (BHIB) was prepared as described (42). Briefly, BHIB powder was dissolved in water, adjusted to pH 6.8, and sterile filtered. Where necessary to maintain the sGFP plasmid, 25 μg/ml spectinomycin was added to the medium. Wild-type and mutant bacteria were inoculated from frozen glycerol stocks onto cysteine heart agar supplemented with 9% defibrinated sheep blood (CHAB) and grown for 24–48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Bacteria were harvested from CHAB plates and resuspended in HBSS containing divalent cations Ca2+ and Mg2+ (HBSS++), and cultures were generated by diluting an aliquot of the bacterial suspension to an OD600 of 0.01 in 7 ml of BHIB. The cultures were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. The next day, overnight cultures were diluted 1:5 with fresh BHIB and grown to midlogarithmic phase (OD600= 0.4–0.6). Bacteria were recovered by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 3 min in a tabletop microcentrifuge, washed twice with HBSS++, and quantified by measurement of absorbance at 600 nm. For 10 bacteria grown in this way, an OD600 of 1 corresponded to a bacterial concentration of ~1 × 10 CFU/ml.

Neutrophil and macrophage isolation

Heparinized venous blood was obtained from healthy adult volunteers in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects at the University of Iowa. PMNs were isolated using dextran sedimentation followed by density gradient separation as described (43). Neutrophils were suspended in HBSS without divalent cations, counted, and diluted to 2x107/ml. Purity of the neutrophil suspensions was assessed by HEMA-3 staining followed by microscopic analysis, and the suspensions were routinely ≥95% PMNs. Monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs)were prepared from blood using standard procedures (12). Briefly, PBMCs were isolated by density gradient separation using Ficoll-Hypaque, washed twice in HEPES-buffered RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with L-glutamine, resuspended to a concentration of 2 × 106 PBMCs/ml in medium supplemented with 20% autologous serum (AS) as well as L-glutamine, and differentiated into MDMs by incubation in Teflon jars for 5-7 days at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Preparation of autologous and pooled human sera

To obtain AS nonheparinized whole blood from each donor was incubated at 37°C for 30 min to permit clot formation, followed by 30 min on ice to allow clot contraction. The blood was centrifuged at 500 g for 15 min at 4°C to pellet the clot and the serum fraction was collected. Agglutination assays using F. tularensis LVS were performed using each AS as previously described (34), and all donors were confirmed to have nonimmune Ab titers (a diagnostic titer is typically ≥1:40, and no donor had agglutination at 1:10). Pooled human serum (PHS) was prepared by combining AS from 14 healthy donors with no reported history of tularemia. AS and PHS were filter sterilized, and either used immediately or stored in aliquots at −80°C. Heat-inactivation (HI) was performed by incubation at 56°C for 30 min.

Serum adsorption assays

To deplete PHS of Abs capable of binding F. tularensis, mid-logarithmic phase wild-type LVS or the wbtA2 mutant were harvested and then incubated on ice for 30 min at a concentration of 1x1010 bacteria in 1.0 ml of 100% PHS. The bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 4°C, and the depletion was repeated on ice with a new aliquot of 1x1010 bacteria. Each depleted serum (designated LVS-depleted or wbtA2-depleted PHS) was filter sterilized using a 0.22 μm syringe filter, chilled to 4°C and used immediately or frozen at −80°C. Mock-depleted PHS was processed in parallel in the absence of bacteria. C3a ELISAs were performed on depleted sera to confirm that the depletion procedure itself did not activate complement (data now shown).

Anti-human IgM agarose (capacity 2–3 mg IgM/ml packed gel) was used to specifically deplete HI-PHS of IgM Abs. Prechilled agarose (0.75 ml packed) equilibrated in cold PBS was mixed with 0.75 ml HI-PHS and the suspension was tumbled at 4°C for 60 min. The agarose was pelleted by centrifugation and the serum was sterilized using a 0.22 μm syringe filter. Due to residual PBS in the agarose, this procedure diluted the serum approximately 50% based on total protein determined by measurement of the OD at 280 nm. Control agarose lacking bound ligands was used to control for nonspecific binding of serum components and for serum dilution. Depletion of IgM from the serum was confirmed by immunoblotting (described below).

Purification of IgG and IgM from PHS using affinity and gel filtration chromatography

All column chromatography was performed using an Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences FPLC at room temperature. IgG was purified from PHS using HiTrap Protein G HP affinity columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 2 ml of PHS were diluted in sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 and passed through two 1.0 ml HiTrap Protein G HP columns connected in series. Bound IgG was eluted using glycine (pH 2.7) into 1 M Tris (pH 9.0) to avoid denaturation of the Ab. Fractions containing 280 nm absorbing material were pooled and buffer replacement into RPMI-1640 medium was performed using a 10,000 M.W. Centricon (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The purified IgG was sterile filtered and stored at 4°C. A three-step purification procedure was performed to purify IgM from PHS. First, IgM was isolated from PHS using HiTrap IgM Purification HP columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Ten milliliters of PHS were diluted in sodium phosphate buffer containing 1.0 M ammonium sulfate (pH 7.5) to obtain a final ammonium sulfate concentration of 0.8 M. To ensure maximal depletion of IgM from the serum, the diluted PHS was passed through three 1.0 ml HiTrap IgM columns connected in series. The Ab was eluted from the columns using sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) and fractions containing 280 nm-absorbing material were combined. Next, the IgM was passed through two HiTrap Protein G columns to deplete contaminating IgG from the sample, and the flow through containing IgM was collected and concentrated to 1.5 ml using a 10,000 M.W. Centricon. Finally, the IgM preparation was further purified by gel filtration chromatography using a Sephacryl HR S300 (1.6 × 70 cm, equilibrated in PBS, pH 7.4) column. The column was calibrated using Bio-Rad gel filtration standards that included thyroglobulin (Vo), γ-globulin, ovalbumin, myoglobin, vitamin B12 (Vi) and HSA. Fractions (1.0 ml each) were collected at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, and those containing 280 nm absorbing material were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris gels and staining with Acqua protein gel stain. Selected fractions containing IgM were pooled and the buffer replaced with RPMI-1640 medium using a 10,000 M.W. Centricon. The purified IgM was sterile filtered and stored at 4°C. Immunoblot analysis confirmed the absence of IgG in the purified IgM preparation.

Phagocytosis assays

In all cases, replicate experiments were performed using PMNs and MDMs from different donors. PMNs (5x107/ml) in 5 ml round-bottomed polypropylene tubes were diluted in RPMI- 1640 medium supplemented with 0.1% HSA and 0–20% PHS as indicated. PMNs were challenged with sGFP-expressing F. tularensis at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI), although a ratio of 10 bacteria per cell was used for most infections. Some experiments included Alexa Fluor®-488 E. coli BioParticles as controls. All samples were tumbled for 5-60 min at 37°C. At specific time points, phagocytosis was stopped by diluting the infection mix 1:1 with ice-cold PBS and placing the cells on ice. Samples were analyzed immediately using an Accuri C6 flow cytometry system (BD Accuri Cytometers, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI) or, for the virulent Schu S4 infection samples, were fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h and then stored in 1% formalin for 4 days at 4°C to ensure sample sterility prior to removal from BSL-3 facility and analysis by flow cytometry. In addition, uninfected PMNs and cells incubated with bacteria at 4°C were used as controls and analayzed to determine the GFP-negative population and to establish the extent of F. tularensis binding to the PMN surface, respectively. By this assay, F. tularensis did not bind to PMNs at 4°C, and these samples were indistinguishable from the uninfected controls. Cells that shifted to higher fluorescence than the GFP-negative gate were considered GFP-positive. For each sample, a phagocytic index (PI) was calculated as previously described (44) using the following equation: (percentage of positive cells × mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) at 37°C) - (percentage of positive cells × MFI at 4°C).

To confirm the flow cytometry results by another method, parallel samples were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy as previously described (8). In brief, PMNs were washed twice with cold PBS and cytocentrifuged onto acid-washed coverslips. Cells were fixed with 10% formalin, permeabilized in cold (1:1) methanol-acetone, blocked in PBS supplemented with 0.5 mg/ml NaN3 and 5 mg/ml BSA and mounted onto glass slides using our established methods (8, 45). sGFP-expressing bacteria in PMNs were either photographed directly, or when DAPI was used to counterstain PMN nuclei, LVS was detected using anti-F. tularensis antiserum and secondary Abs conjugated to DyLight™ 488. This latter staining strategy facilitated imaging of bacteria as the DAPI fluorescence tended to cause rapid bleaching of sGFP (data not shown). Images were obtained using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 epifluorescence microscope using Axiovision 4.1 imaging software (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY).

In addition, ingestion of PMN-associated bacteria was assessed directly using a modification of our established differential staining protocol (12). PMN were infected with sGFP-expressing F. tularensis as described above for flow cytometry, pelleted by centrifugation at 200 × g for 7 min at 4°C, and then resuspended in ice-cold blocking buffer containing F. tularensis antiserum (which has access only to extracellular bacteria on the surface of live, intact PMNs). After incubation for 30 min on ice, PMNs were washed once, cytocentrifuged onto acid washed coverslips and then fixed for 30 min in 10% formalin. Cells were then incubated with rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit F(ab)’2 secondary Abs, washed and mounted onto glass coverslips. By this assay, intracellular bacteria are green (sGFP-positive) whereas attached/extracellular bacteria are both red (rhodamine-positive) and green (sGFP-positive) and thus appear yellow in merged images.

To quantify macrophage uptake of F. tularensis Schu S4, MDMs were plated at 40,000 cells/well in Nunc Lab-Tek® glass chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY.) in RMPI-1640 medium containing 10% PHS and allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C. MDMs were rinsed three times with PBS to remove non-adherent cells and then infected with Schu S4-sGFP or LVS-sGFP at a MOI of 20:1 in RPMI-1640 medium in the absence of serum, or in medium containing 20% normal or modified PHS, as indicated. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, uningested bacteria were removed by washing MDM monolayers three times with PBS.

Samples were fixed in 10% formalin for 25 min and then permeabilized in cold methanol:acetone (1:1) for 15 min. Samples were analyzed using epifluorescence microscopy as we described (12). Both the percentage of infected MDMs in the monolayer and PIs (total bacteria per 100 cells) were determined by analysis of random fields of view (12).

Blocking PMN and MDM surface receptors

Isolated neutrophils (5x106/ml) were diluted in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 0.1% HSA and 15 or 30 μg/ml blocking or isotype control Abs at 4°C for 15 min. Thereafter, PHS was added to a concentration of 10%, and the cells were challenged with sGFP-expressing F. tularensis at an MOI of 10:1. Samples were then tumbled for 30 min at 37°C. Phagocytosis was stopped by diluting the samples 1:1 with ice-cold PBS and transferring the cells to ice. Phagocytosis was measured by flow cytometry as described above. MDMs attached to glass chamber slides (40,000 cells/well) were preincubated with blocking Abs (30 μg/ml) and then infected in a similar manner with sGFP-expressing LVS and Schu S4, except that bacteria were added at MOI 20:1 and cells were incubated for 60 min at 37°C prior to processing for microscopy as described above.

Immunoblotting

We used immunoblotting to demonstrate IgM binding to and C3 deposition on F. tularensis LVS. In the course of these studies we determined that LVS-reactive IgM was limiting in PHS, and that opsonization of LVS did not occur if very large numbers of bacteria were incubated in small volumes of serum, even when serum concentrations were increased to 50%. To demonstrate this directly, bacteria at 4x108/ml–7.2 x109/ml in 50% serum were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and then washed four times in PBS. Next, 1.2 × 109 bacteria from each sample were transferred to a fresh tube, pelleted, and raised in water with protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). Thereafter 4x NuPAGE® SDS sample buffer and 10x reducing agent (Invitrogen) were added, and samples were heated at 75°C for 10 min. The final volume of each sample was 100 μl, and in order to reduce viscosity, each was sonicated for one second. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using NuPAGE Novex 4 12% BisTris gels using MOPS running buffer (Invitrogen). In order to increase the resolution of larger proteins, gels were run at 200 volts for ~ 3 h such that the smallest protein remaining in the gel was ~ 35 kDa. Proteins were transferred to an Immobilon®-FL polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore) using an XCell II blot apparatus and NuPAGE transfer buffer (Invitrogen). For detection of IgM, membranes were blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline for 1 hour and incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgM (US Biological). Bands were detected using WestPico enhanced chemiluminescence substrate and film. For detection of C3 fragments, membranes were blocked in LiCor Odyssey® blocking buffer and then incubated with goat anti-human C3 Ab (Quidel) followed by LiCor IRDye 680LT Donkey anti-Goat IgG. Blots were imaged using a LiCor Odyssey® Fc infrared imaging system.

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-test. All statistical comparisons were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 software. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Phagocytosis of F. tularensis LVS by human neutrophils is markedly enhanced by nonimmune serum

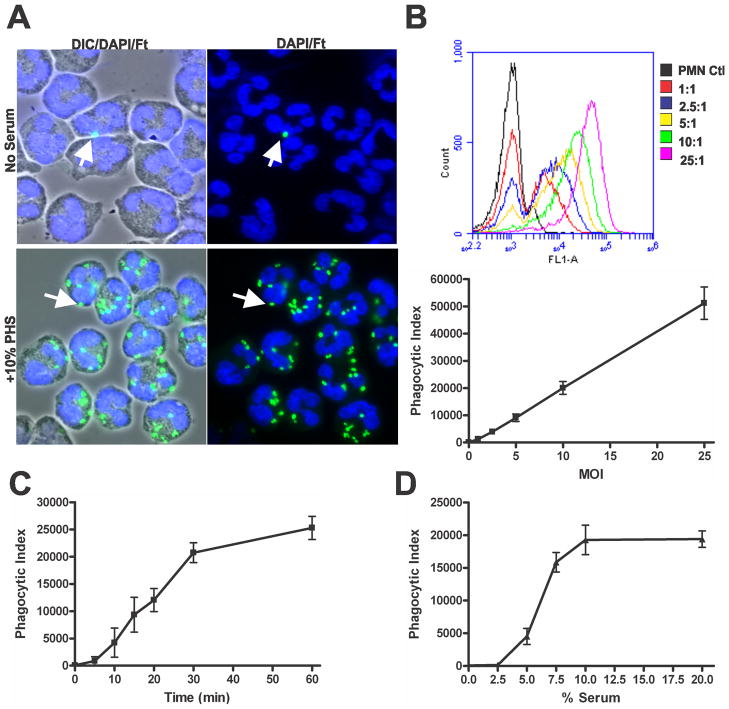

In our first series of experiments we utilized flow cytometry to quantify phagocytosis of F. tularensis by human neutrophils. To this end, we generated LVS that stably expressed sGFP, and used sera pooled from 14 healthy donors who had no history of tularemia and who had agglutination titers < 1:10 (data not shown). To verify that PHS could enhance phagocytosis as previously reported by Löfgren et al. (28), neutrophils were incubated with LVS at an MOI of 10:1 in media alone or in media supplemented with 10% PHS and then analyzed by microscopy and flow cytometry. In the absence of serum, LVS phagocytosis was inefficient as judged by microscopy (Fig 1A), and <5% of PMNs shifted to the infected (GFP-positive) gate when analyzed by flow cytometry (Supplemental Fig. 1A). In contrast, PHS markedly enhanced LVS phagocytosis (Fig 1A), and >90% of the PMN population was GFP-positive (Supplemental Fig. 1A). To evaluate flow cytometry as a quantitative measure of F. tularensis phagocytosis, PMNs were incubated with increasing doses of LVS (MOI 1:1-25:1) in the presence of 10% PHS for 60 min. GFP-positive PMNs were detectable at MOIs as low as 1:1 and increased in a dose-dependent manner at all MOI tested (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Fig. S1B), and the MFI of the GFP-positive population correlated directly with the bacterial dose (Supplemental Fig. S1B). Using these data, an overall phagocytic index (PI) was calculated for the PMN population (see Methods for details). In additional experiments the effects of incubation time and serum concentration on LVS uptake were examined. Phagocytosis of LVS was rapid in medium containing 10% serum, with most bacteria being internalized within 30 min (Fig 1C). Serum concentrations as low as 5% enhanced LVS uptake over baseline, with optimal results obtained using 10-20% PHS (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Nonimmune serum enhances phagocytosis of F. tularensis LVS by PMNs. A, Microscopy images of PMNs infected with sGFP-LVS (MOI 10:1) in the absence and presence of 10% PHS for 30 min at 37°C. Bacteria are shown in green and PMNs are shown by differential interference contast (DIC) optics and DAPI-staining of nuclear DNA (blue). Arrows indicate representative bacteria. B-D, Quantitation of phagocytosis using flow cytometry. B, Neutrophils were challenged with increasing MOIs (1:1-25:1) of sGFP-LVS in medium with 10% serum for 60 min at 37°C. Upper panel, representative histograms show that fluorescence is proportional to LVS dose. Lower panel, graph shows phagocytic index at each MOI. Data are the mean ± SEM from three experiments. C, Phagocytosis is time-dependent. PMNs were infected at MOI 10:1 in medium containing 10% PHS. Phagocytic indices were determined at the indicated time points. Pooled data are the mean ± SEM of three experiments. D, Effects of serum concentration. PMNs were infected at MOI 10:1 for 30 min in medium containing 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 or 20% PHS. Pooled data from four independent experiments show phagocytic indices as mean ± SEM.

Differential staining of cells infected in medium with 10% PHS confirmed that at least 90% of PMN-associated LVS were intracellular (Supplemental Fig. S1C and data not shown). Furthermore, as the flow cytometry data suggests that as few as 1-2 bacteria could shift PMNs to the GFP-positive gate (Fig. 1B), we sought to confirm the sensitivity of this assay by directly comparing by flow cytometry and microscopy PMNs infected with GFP-LVS at low MOI. The results of three experiments indicate that PMNs infected at MOI of 1:1 or 2:1 contained an average of 1.8 ± 0.4 and 2.8 ± 1.0 LVS, respectively as judged by fluorescence microscopy (not illustrated), and as shown in Supplemental Figures S1D-E, the percentage of infected PMNs and the normalized PIs determined by each method were indistinguishable. Altogether, these data indicate that flow cytometry is a sensitive and quantitative method that can be used to quantify F. tularensis uptake by PMNs and confirm the ability of PHS to enhance this process.

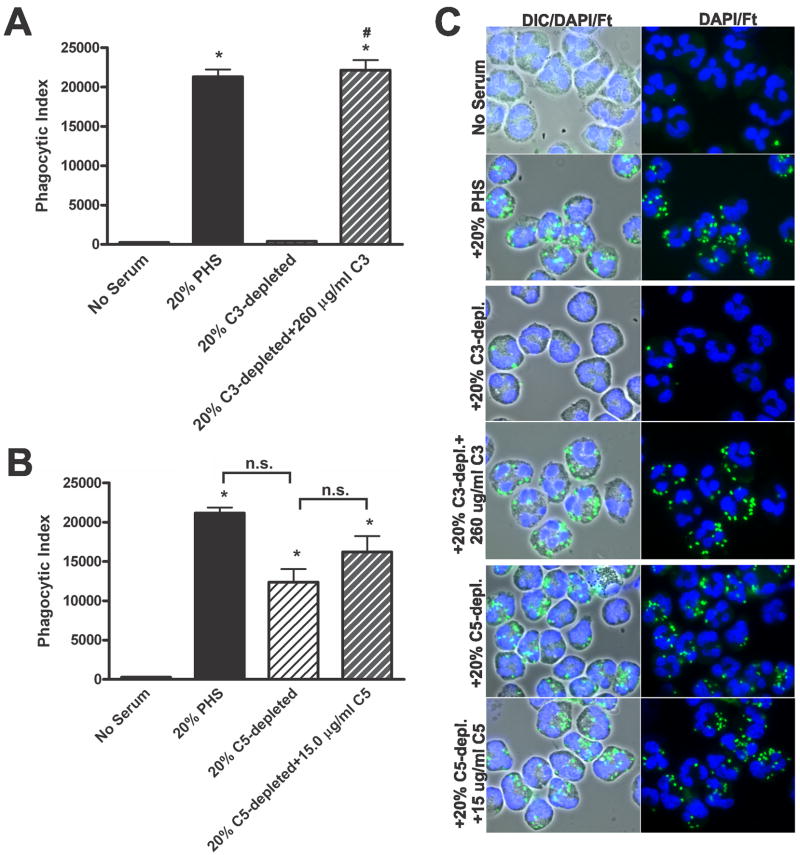

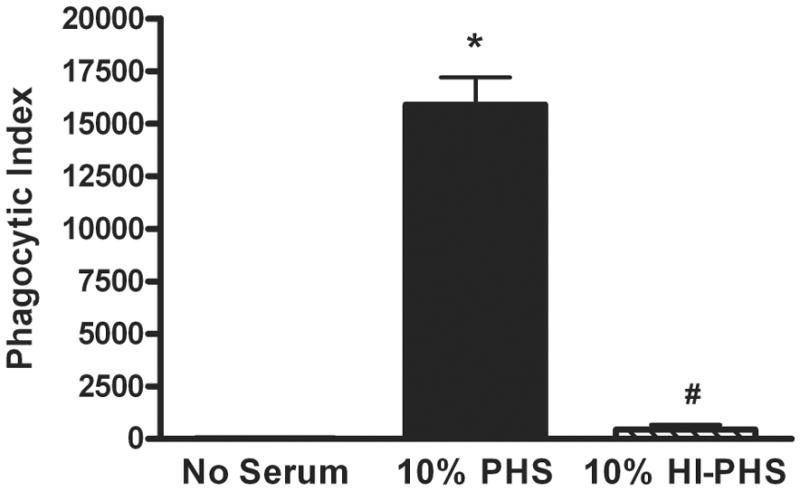

Serum-enhanced uptake of F. tularensis LVS by PMNs requires complement factor C3, but not C5

To validate a role for complement in phagocytosis, PHS was incubated at 56°C for 30 min to irreversibly inactivate the complement system. Consistent with the data shown above, PHS significantly enhanced phagocytosis of LVS compared to the no-serum control, whereas HI-PHS did not (no serum 230 ± 8, +10% PHS 15,902 ± 285, +10% HI-PHS 437 ± 225, P< 0.001; Fig 2). To further define the role of complement in PMN phagocytosis of F. tularensis, we utilized sera depleted of complement factors C3 or C5. C3 plays a central role in the complement pathway, such that C3-derived fragments function both as integral components of complement amplification (e.g. C3b) and as opsonins (e.g. C3b and iC3b). Although not directly involved in opsonization, C5a can promote phagocytosis indirectly by stimulating upregulation of CR3 on PMNs (46). We therefore evaluated phagocytosis of LVS by neutrophils in the presence of 20% PHS, 20% C3-depleted PHS or 20% C5-depleted PHS. C3 depletion ablated the serum-enhanced uptake of LVS such that there was no distinguishable difference between the no-serum control and cells incubated in C3-depleted serum (Figs 3A and 3C). Replenishment of C3-depleted serum using physiological amounts of purified C3 (260 μg/ml) (47) restored phagocytosis of LVS to levels similar to the 20% PHS control, confirming specificity. In contrast, C5 was not essential, as C5-depleted serum retained the ability to significantly augment LVS phagocytosis significantly compared to the no serum control (P< 0.001; Figs. 3B-3C), and addition of purified C5 (15 μg/ml) (47) at physiological levels to the C5-depleted serum had no significant effect. Altogether, these data demonstrate that uptake of F. tularensis LVS by human PMNs in the presence of nonimmune serum is critically dependent upon C3, but not C5.

FIGURE 2.

Serum-enhanced uptake of F. tularensis LVS is abrogated by heat-inactivation of PHS. Neutrophils were infected for 30 min with sGFP-LVS (MOI 10:1) in media containing no serum, 10% PHS or 10% HI-PHS. Phagocytic indices are the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. *P <0.001 vs. no serum, #P <0.001 vs. 10% PHS.

FIGURE 3.

F. tularensis LVS phagocytosis requires C3, but not C5. PMNs were infected with sGFP-LVS at MOI 10:1 for 30 min in medium containing no serum, 20% PHS, 20% C3-depleted serum, 20% C3-depeleted serum reconstituted with 260 μg/ml purified C3, 20% C5-depleted serum, or 20% C5-depleted serum reconstituted with 15 μg/ml purified C5, as indicated. Phagocytosis was quantified by flow cytometry and microscopy. A, Enhanced phagocytosis requires C3. Flow cytometry data are the mean ± SEM (n=4). *P <0.001 vs. no serum, and #P <0.001 vs. 20% C3-depleted PHS. B, Complement protein C5 is not essential. Flow cytometry data are the mean ± SEM (n=4). *P <0.001 vs. no serum; n.s., not statistically significant. C, Representative microscopy images show LVS in green and PMN are shown by DIC optics and/or DAPI-staining of nuclear DNA (blue).

Complement-mediated phagocytosis of F. tularensis LVS is dependent upon the classical pathway protein C1q

Our previous work demonstrates that LVS does not bind mannose-binding lectin (12), results which argue against a role for the lectin pathway in complement activation by this organism. Rather, others have shown that C3 deposition on LVS is diminished upon depletion of C1q or chelation of calcium (32, 33), implicating the classical pathway in complement activation by F. tularensis. Initiation of the classical pathway requires recruitment of C1q, C1r, and C1s to the microbe surface, typically via recognition of IgM or IgG bound to the organism (18, 19). To determine if the classical pathway was essential for PMN phagocytosis of LVS, we directly compared uptake of LVS in 20% PHS or C1q-depleted serum. As shown in Figures 4A and 4B, depletion of C1q ablated uptake of LVS by PMNs, and phagocytosis was restored by the addition of purified C1q (40 μg/ml, (47)) to the depleted serum. These data extend previous work to demonstrate that C1q is essential for serum-mediated phagocytosis of LVS by human PMNs, and as such suggest that the classical pathway plays a major role in promoting complement-mediated uptake of F. tularensis.

FIGURE 4.

Phagocytosis of F. tularensis LVS requires complement protein C1q. PMNs were challenged with sGPF-LVS (MOI 10:1) for 30 in medium without serum or with 20% PHS, 20% C1q-depleted serum, or 20 % C1q-depleted serum reconstituted with 40 μg/ml purified C1q protein. A, Pooled flow cytometry data indicate phagocytic indices as the mean ± SEM (n=3). *P <0.001 vs. no serum and #P <0.001 vs. 20% C1q-depleted PHS. B, Representative immunofluorescence images confirm the importance of C1q for the phagocytosis of LVS. Bacteria are shown in green and PMNs were detected using DIC optics and DAPI-staining of nuclear DNA (blue).

Classical pathway activation by F. tularensis LVS is mediated by natural IgM in nonimmune serum

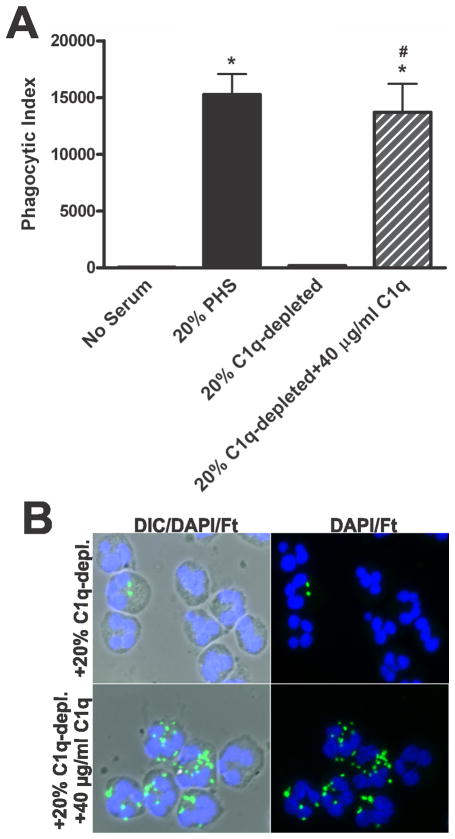

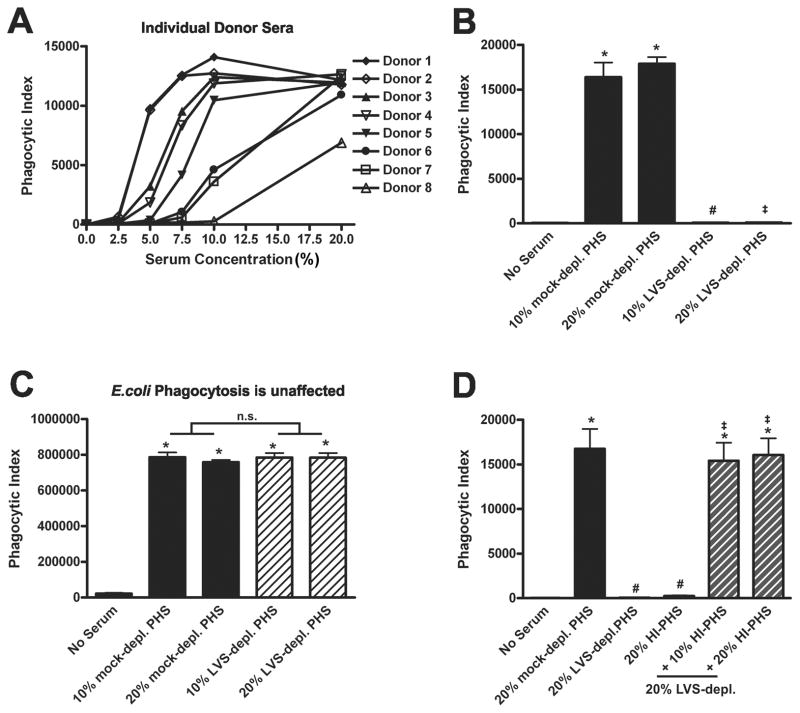

Although the classical pathway is typically activated by C1q binding to Abs on microbe surfaces, direct interactions between C1q and bacteria have also been reported (20–25). In the course of our studies we noticed that when assayed separately, sera from individual donors within our pool differed in their ability to enhance LVS phagocytosis. For these experiments, neutrophils from a single donor were infected in parallel with LVS in media supplemented with increasing concentrations of serum from eight different donors. As illustrated in Figure 5A, serum from some donors enhanced uptake at concentrations as low as 2.5–5% (donors 1 and 2), whereas other donor sera failed to promote phagocytosis at concentrations below 10% (donors 6 and 7). In one case (donor 8), phagocytosis remained below maximum even in 20% PHS. These data suggest that individual sera contained different concentrations of a component or components necessary to enhance LVS phagocytosis. As none of our donors was immune to F. tularensis and levels and specificities of Abs can vary among healthy individuals, we hypothesized that natural Abs may be involved in classical pathway activation by LVS.

FIGURE 5.

Phagocytosis of F. tularensis LVS requires heat-stable factor(s) in normal donor sera that bind to LVS at 4°C. A, Individual donor sera vary in their ability to enhance LVS uptake by PMNs. Neutrophils from a single donor were incubated with sGFP-LVS at MOI 10:1 in the presence of increasing concentrations of sera from eight different individuals in our donor pool. Phagocytic indexes were quantified by flow cytometry at 30 min. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. B-C, LVS can adsorb and deplete factors from PHS at 4°C that are required for serum-dependent phagocytosis of LVS, but not E. coli. LVS-and mock-depleted sera were generated as described in the Methods. PMNs were challenged for 30 min with LVS-sGFP at MOI 10:1 (B) or Alexa Fluor®-488 E. coli BioParticles at MOI 10:1 (C) in media containing no serum, 10% or 20% PHS, or 10% or 20% LVS-depleted (depl.) serum as indicated. Phagocytic indices were determined by flow cytometry and are the mean ± SEM (n≥3). *P <0.001 vs. no serum; #P <0.001 vs. 10% PHS; ‡P <0.001 vs. 20% PHS, n.s., not significant. D, A combination of HI-PHS and LVS-depleted serum restores serum-enhanced uptake of LVS. PMNs were incubated with sGFP-LVS at MOI 10:1 for 30 min in the absence of serum or with 20% PHS, 20% LVS-depleted serum, 20% HI-PHS, or 20% LVS-depleted serum supplemented with 10% or 20% HI-PHS. Pooled data indicate phagocytic indices as the mean ± SEM (n=3). *P <0.001 vs. no serum; #P <0.001 vs. 20% PHS; ‡P <0.001 vs. 20% LVS-depleted PHS.

To test our hypothesis, we performed a series of serum adsorption assays using LVS to deplete PHS of any LVS-reactive Abs. These incubations were performed at 4°C to prevent activation and consumption of complement. Although mock-depleted PHS at 10 or 20% final concentration markedly enhanced LVS phagocytosis relative to the no-serum control (P< 0.001; Fig. 5B), this was not true for LVS-depleted PHS. Neutrophils challenged with LVS in either 10% or 20% LVS-depleted PHS failed to internalize bacteria, suggesting that prior adsorption of opsonins was sufficient to ablate uptake (Figs. 5B and Supplemental Fig. S2). Indeed, even at concentrations as high as 50% LVS-depleted serum, no phagocytosis was observed (data not shown). To determine if LVS-depleted PHS could still promote phagocytosis of other particles, we quantified PMN uptake of E. coli in mock- or LVS-depleted PHS. Both sera markedly enhanced phagocytosis of E. coli as judged by flow cytometry (Fig. 5C) and fluorescence microscopy (Supplemental Figure S2), and similar results were also obtained using yeast zymosan particles (data not shown). These data suggest that prior incubation with LVS depleted PHS of opsonins required specifically for phagocytosis of F. tularensis without generally impacting its ability to promote uptake of other particles by neutrophils.

To further investigate a possible role for Abs in serum-mediated phagocytosis of LVS, we reconstituted LVS-depleted PHS with HI-PHS. We predicted that heat-stable proteins (such as Abs) in HI-PHS could replenish the Abs lost by adsorption to LVS, and thereby act in concert with complement factors in the depleted serum to restore classical pathway activation and phagocytosis. To test this, neutrophils incubated with LVS in media containing 20% mock-depleted PHS, 20% LVS-depleted PHS, 20% HI-PHS, or 20% LVS-depleted PHS reconstituted with 10% or 20% HI-PHS were directly compared. Consistent with our earlier results, LVS phagocytosis was significantly diminished in both the LVS-depleted and HI-PHS samples compared to the mock-depleted PHS control (Fig. 5D). Addition of HI-PHS (10% or 20%) to the LVS-depleted serum completely restored LVS uptake. These data strongly suggest a role for heat-stable opsonins, such as Abs, in serum-mediated phagocytosis of LVS.

The classical pathway is typically activated by IgG and/or IgM on microbe surfaces. To determine if either Ab isotype was involved in serum-mediated phagocytosis of LVS, we purified IgG and IgM from PHS using a combination of affinity and gel filtration chromatography as described in the Methods. The purified fractions were highly enriched for their respective Abs type as indicated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6A). Western analysis of the IgM sample confirmed the absence of IgG in this preparation (data not shown). Physiological levels of purified IgG or IgM (http://www.merckmanuals.com/media/professional/pdf/Appendix_II-Table-1.pdf) were added to LVS-depleted PHS and neutrophil phagocytosis of LVS was assessed. IgG at concentrations of 125 μg/ml, 750 μg/ml, and 1500 μg/ml (normal range of IgG in 20% PHS: 1,280-2,860 μg/ml) failed to stimulate phagocytosis of LVS in LVS-depleted serum (Fig 6B, upper panel). Conversely, supplementation of LVS-depleted PHS with 25 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, 75 μg/ml or 100 μg/ml of purified IgM (normal range of IgM in 20% serum: 40-280 μg/ml) significantly enhanced phagocytosis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6B, lower panel). To confirm that IgM was essential for serum-dependent uptake of LVS, we specifically depleted IgM from HI-PHS using anti-IgM agarose, and confirmed this depletion by immunoblotting (Supplemental Figure S3). In addition, HI-PHS was incubated with unconjugated agarose to control for nonspecific binding. Similar to the studies performed in Fig. 5D, we reconstituted 20% LVS-depleted PHS with an equal concentration of unmodified HI-PHS, control-depleted HI-PHS, or IgM-depleted HI-PHS. Consistent with our previous results, addition of unmodified HI-PHS to LVS-depleted serum restored neutrophil phagocytosis of LVS (Fig 6C). Reconstitution of LVS-depleted serum with control agarose-depleted HI-PHS also rescued LVS phagocytosis. In contrast, IgM-depleted HI-PHS failed to reconstitute the ability of LVS-depleted serum to support bacterial uptake, providing definitive evidence that IgM is essential for serum-mediated phagocytosis of LVS by neutrophils.

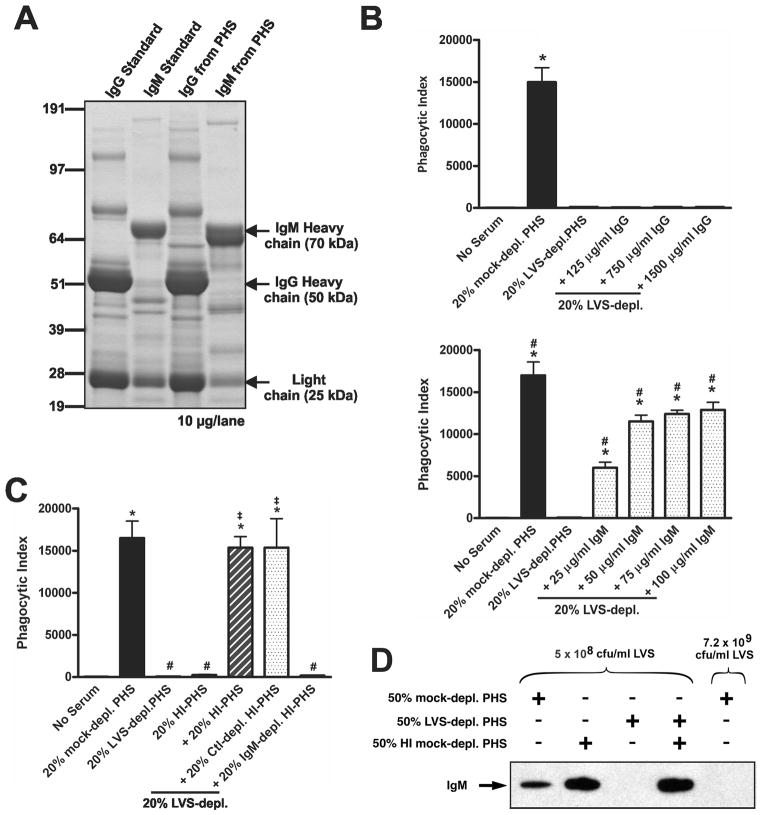

FIGURE 6.

IgM in nonimmune PHS binds F. tularensis LVS and is required for serum-enhanced phagocytosis. A, IgG and IgM were purified from PHS, and 10 μg of each sample was analyzed alongside human IgG and IgM standards using NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris gradient gel electrophoresis and Acqua protein gel staining. B, Purified IgM, but not IgG, restores the ability of LVS-depleted PHS to support bacterial uptake. Neutrophils were challenged with sGFP-LVS at MOI 10:1 in media without serum or with 20% mock-depleted PHS, 20% LVS-depleted PHS, or 20% LVS-depleted PHS supplemented with the indicated concentrations of purified IgG or IgM. Pooled data indicate phagocytic indices and are the mean ± SEM (n≥3). *P <0.001 vs. no serum; #P <0.05, ##P <0.01, ###P <0.001 vs. 20% PHS. C, Immunodepletion of IgM abrogates LVS uptake. IgM was removed from HI-PHS by immunoprecipitation. PMNs were infected with sGFP-LVS at MOI 10:1 for 30 min in media without serum or in media supplemented with 20% mock-depleted PHS, 20% LVS-depleted PHS, 20% HI-PHS, or 20% LVS-depleted PHS supplemented with 10% or 20% HI-PHS, 10% or 20% control agarose-depleted (Ctl-depl.) HI-PHS, or 10% or 20% IgM-depleted HI-PHS. Phagocytic indices were determined using flow cytometry. Data are the mean ± SEM (n=3). *P <0.001 vs. no serum; #P <0.001 vs. 20% PHS; n.s., not statistically significant. D, LVS-reactive IgM is limiting in PHS. LVS was incubated for 30 min in 50% LVS-depleted PHS, 50% mock-depleted PHS, or 50% heat-inactivated (HI) mock-depleted PHS, or a combination of 50% LVS-depleted and 50% HI mock-depleted PHS at a concentration of 5x108 or 7.2x109 CFU/ml as indicated and then washed with PBS. 1.2x109 bacteria from each sample were loaded per lane, and human IgM on the bacterial surface was detected by immunoblotting. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments of similar design.

Finally, to demonstrate that IgM was indeed binding to LVS, we subjected washed, opsonized bacteria to SDS-PAGE with immunoblotting for IgM. To maintain a similar ratio of serum opsonins to bacteria as in our optimal phagocytosis conditions, we incubated LVS in 50% serum at 5x108 CFU/ml. IgM was readily detected after opsonization of LVS with mock-depleted PHS or HI mock-depleted PHS, yet was undetectable when bacteria were opsonized with LVS-depleted serum (Fig. 6D). Moreover, binding of IgM to LVS was clearly restored on bacteria opsonized in LVS-depleted PHS supplemented with HI mock-depleted PHS. However, it is important to note that if opsonization was conducted using a higher concentration of LVS (7.2 × 109 CFU/ml), IgM deposition per organism was markedly reduced (each lane in Fig. 6D contains 1.2 x109 LVS) and was only detectable after prolonged exposure of the blotting membrane (not shown). Thus, IgM levels can be limiting when very large numbers of bacteria are incubated in small volumes of serum, which in turn diminishes opsonization and impairs phagocytosis efficiency. Collectively, these data demonstrate that serum-enhanced uptake of F. tularensis LVS by human neutrophils in nonimmune serum is dependent upon IgM.

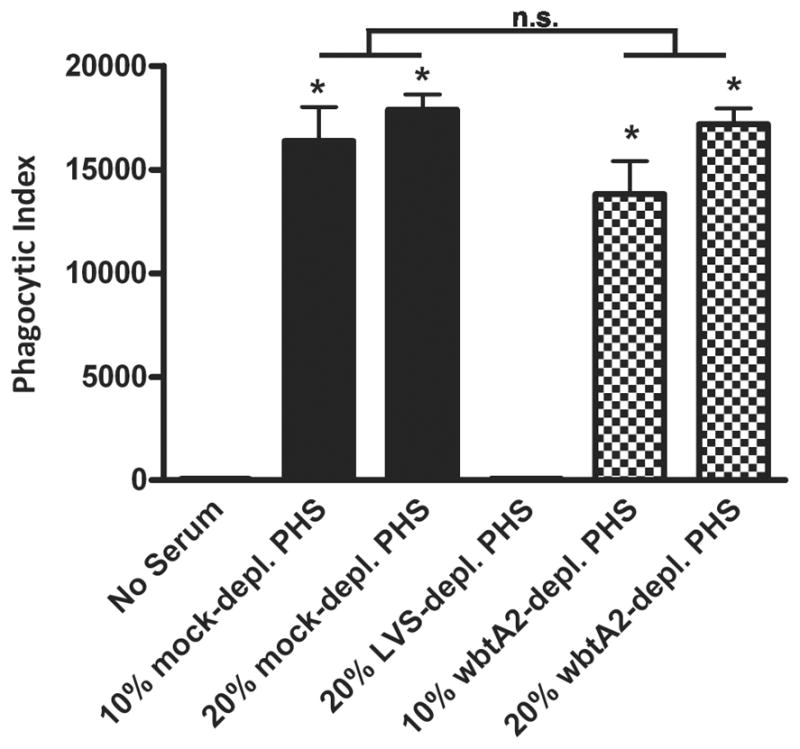

Depletion of serum opsonins by F. tularensis LVS requires O-antigen and/or capsule

Given the importance of IgM to phagocytosis of LVS by human neutrophils, we wanted to identify potential targets of IgM on the bacterial surface. Since capsule and LPS O-antigen are likely the most prominent molecules exposed to the environment, we hypothesized that the opsonizing IgM in serum may recognize these sugars of F. tularensis. To test this hypothesis, we utilized the wbtA2 LVS mutant shown previously (37, 48) and confirmed by us (8) to be devoid of LPS O-antigen and capsule. We predicted that this mutant may lack targets for IgM binding and consequently fail to deplete PHS of LVS-reactive Abs in the serum adsorption assay. PHS was serially adsorbed with wild-type LVS or the wbtA2 mutant at 4°C as previously described. Neutrophils were incubated with LVS in 10% or 20% mock-depleted, LVS-depleted, or wbtA2-depleted PHS, and phagocytosis was quantified. In contrast to the LVS-depleted PHS, wbtA2-depleted PHS enhanced phagocytosis to the same extent as mock-depleted serum (Fig. 7 and Supplemental Fig. S2), indicating that the wbtA2 mutant did not deplete PHS of opsonins essential for wild-type LVS uptake. These data suggest that natural IgM found in nonimmune serum binds the O-antigen or capsular sugars on the bacterial surface, resulting in efficient phagocytosis of F. tularensis LVS.

FIGURE 7.

The wbtA2 mutant does not deplete serum of factors required to enhance wild-type LVS uptake. PHS was adsorbed with 1x1010/ml wild-type LVS or the wbtA2 mutant as described in the Methods. Mock-depleted, LVS-depleted or wbtA2-depleted sera at 10 or 20% concentration were tested for the ability to enhance sGFP-LVS (MOI 10:1) uptake relative to the no serum control. Phagocytic indices were determined after 30 min at 37°C. Data are the mean ± SEM (n=3). *P <0.001 vs. no serum; #P <0.001 vs. 10% PHS; ‡P <0.001 vs. 20% PHS.

Depletion of PHS using F. tularensis LVS impairs its ability to mediate C3 deposition

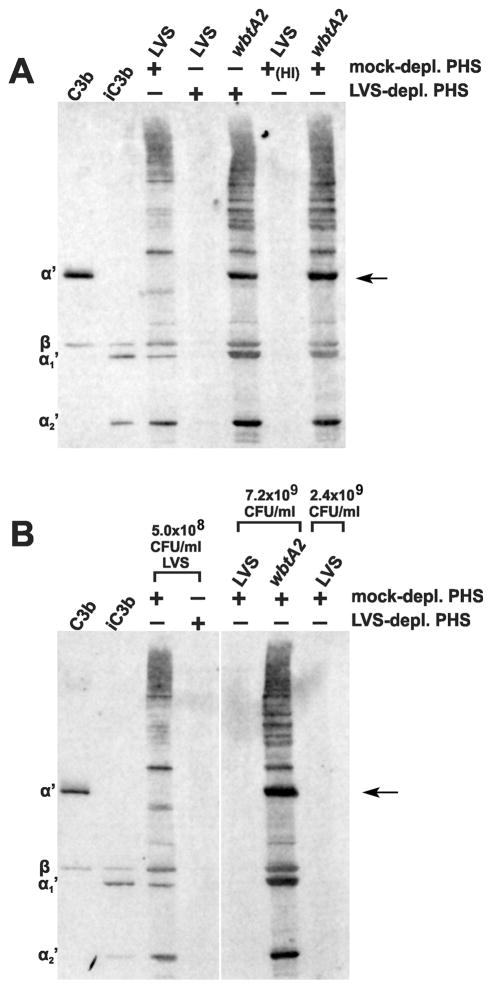

IgM initiates complement activation and opsonization with great efficiency (49), and can be particularly important for serum-mediated phagocytosis of encapsulated bacteria (50). We hypothesized that LVS-depleted serum failed to confer uptake of LVS due to its impaired ability to support C3 deposition on the bacterial surface. C3 consists of a 113 kDa α chain linked to a 75 kDa ß chain by a disulfide bond (51). Cleavage of a 12 kDa C3a fragment from the α chain results in formation of C3b, which has an exposed labile thiolester on the remaining α’ chain that can bind targets via an ester or amide bond. C3b can be inactivated by factor I, which cleaves the α’ chain, leaving iC3b, which consists of α1’ and α2’ chains (67 kDa and 40 kDa, respectively) that remain attached to the ß chain via disulfide bonds (51). We opsonized F. tularensis LVS in mock- or LVS-depleted PHS for 30 min, washed the bacteria thoroughly, and subjected them to SDS-PAGE in reducing conditions with immunoblotting for C3 (Fig. 8). Ample C3 deposition was observed on LVS incubated at 4 × 108 CFU/ml in mock-depleted PHS, but was undetectable on bacteria incubated in LVS-depleted PHS or in HI-PHS (Fig. 8A). The 75 kDa ß-chain common to both iC3b and C3b migrates at its native size since it does not covalently bind a target on the bacterium. The bands running at greater than 104 kDa are α’ and α1’ chains bound to targets via the thiolester bond. The 40 kDa α2’ fragment runs at its native molecular weight and is indicative of iC3b formation. C3 deposition on wbtA2 was ample and was unaffected by LVS-depletion, confirming intact complement activity. Our comparison of LVS and the wbtA2 mutant is notable for the lack of a 104 kDa band on LVS opsonized by mock-depleted PHS (Fig. 8, arrows), consistent with a relative paucity of intact C3b on wild-type bacteria, as reported by Clay et al. (32).

FIGURE 8.

LVS-depleted PHS does not mediate C3 deposition on LVS. A. LVS (4 × 108 CFU/ml) was incubated in a 33% concentration of the indicated sera for 30 min. To confirm complement activity in the depleted serum, wbtA2 (7.2 × 109 CFU/ml) was incubated in a 50% concentration of the indicated sera. Bacteria were washed and identical quantities of each were analyzed by immunoblotting for human C3. B, Higher concentrations of LVS are not efficiently opsonized. The indicated concentrations of bacteria were incubated in a 50% concentration of the indicated sera for 30 min and analyzed by immunoblotting as above. Despite loading 50% more bacteria in the rightmost three lanes, no C3 is detected on LVS. The wbtA2 mutant fixes ample quantities of C3 at this concentration. Results in this figure are representative of at least four experiments of similar design. The C3 fragments identified on the left of each image have molecular weights of ~104 kDa, ~75 kDa, ~67 kDa, and ~40 kDa.

In keeping with the data shown in Figure 6D, we detected C3 on LVS that were opsonized at 5 x108 CFU/ml in 50% mock-depleted PHS, but not on bacteria that were opsonized at 2.4 or 7.2 x109 CFU/ml (Fig. 8B). In contrast, C3 was abundant on wbtA2 organisms that were opsonized at high density (Fig. 8B). Taken together, our data indicate that F. tularensis LVS can be efficiently opsonized with C3 fragments, but complement activation is impaired by depletion of LVS-binding opsonins or experimental conditions in which IgM is limiting.

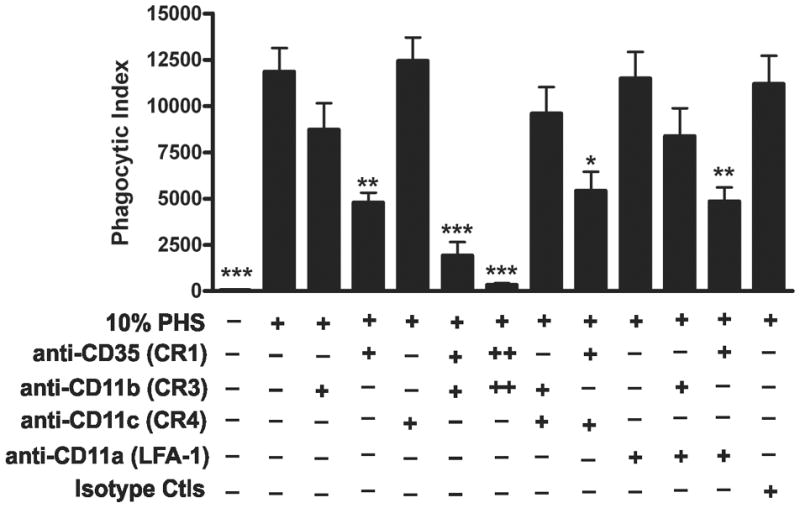

CR1 and CR3, but not CR4, are critical for serum-mediated uptake of F. tularensis LVS by PMNs

Although receptors involved in phagocytosis of F. tularensis by macrophages and dendritic cells have been described, similar data are not available for PMNs. As C3 deposition was detected on LVS, we hypothesized that complement receptors may be essential for uptake. Neutrophils express CR1 (CD35) as well as the β2 integrins CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and CR4 (CD11c/CD18) (52). To evaluate the role of these receptors in serum-mediated uptake of LVS, we pretreated neutrophils with receptor-blocking Abs, either alone or in combination, added bacteria in 10% PHS, and 30 min later assayed phagocytosis using flow cytometry (Fig. 9). To control for potential nonspecific effects due to Ab binding the PMN surface, we also included an LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18)-blocking Ab, as this integrin plays a role in PMN adhesion, but not phagocytosis (53, 54). When CR3 alone was blocked using anti-CD11b, LVS phagocytosis was consistently diminished by ~25% compared to the PHS control, but this was not statistically significant. On the other hand, blocking CR1 with anti-CD35 diminished LVS uptake by 55%, which was highly statistically significant (P< 0.01), and simultaneous blockade of both CR1 and CR3 profoundly inhibited LVS uptake in a dose-dependent manner, with 84% and 97% inhibition achieved using 15 or 30 μg/ml of each Ab, respectively (P< 0.001). Blocking CR4 with anti-CD11c had no apparent effect when tested alone or in combination with anti-CD35 or anti-CD11b. Finally, neither the isotype control Abs nor blockade of LFA-1 with anti-CD11a impaired LVS internalization. Collectively, these data demonstrate that serum-mediated uptake of F. tularensis LVS by human neutrophils is dependent on CR1 and CR3, but not CR4.

FIGURE 9.

CR1 and CR3, but not CR4, are critical for serum-mediated phagocytosis of F. tularensis LVS. Neutrophils were preincubated for 15 min at 4°C without blocking Abs or with 15 μg/ml (+) or 30 μg/ml (++) of anti-CD35 (CR1), anti-CD11b (CR3), anti-CD11c (CR4), anti-CD11a (LFA-1) or isotype control Abs as indicated. Thereafter, sGFP-LVS at MOI 10:1 and 10% PHS were added. After 30 min at 37°C, samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. Phagocytic indices are shown as the mean ± SEM (n≥3). *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001 vs. 10% PHS.

Serum-enhanced phagocytosis of virulent F. tularensis Schu S4 by human PMNs requires IgM and complement and is mediated by CR1 and CR3

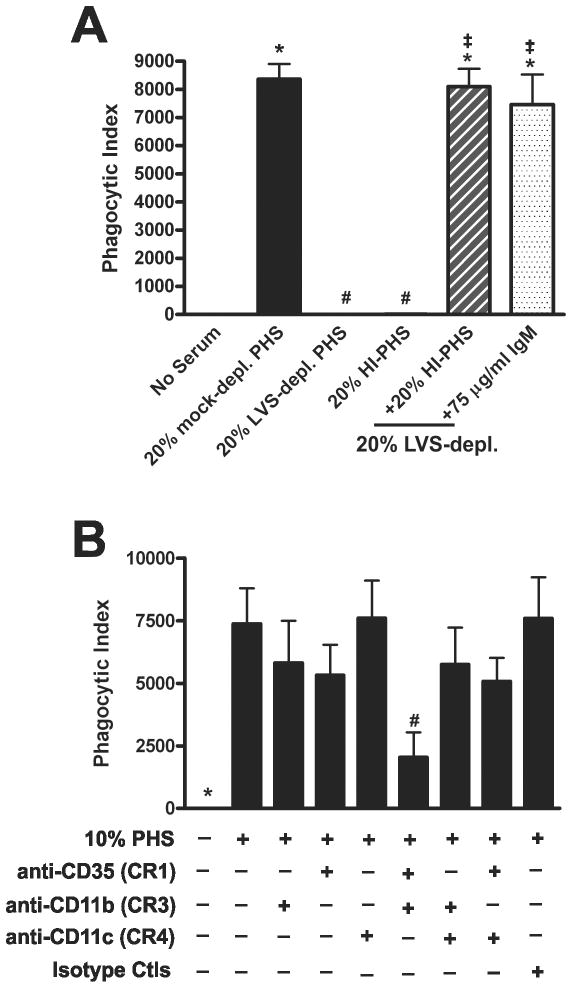

Our data suggest a model in which uptake of LVS by human neutrophils is markedly enhanced by IgM binding to the bacterial surface and subsequent activation of the complement cascade to promote C3-dependent opsonization and phagocytosis via complement receptors CR1 and CR3. To determine whether this was also true for virulent type A F. tularensis, we challenged neutrophils with sGFP-expressing Schu S4 in the absence of serum or in media containing 20% mock-depleted PHS, 20% LVS-depleted PHS, or 20% HI-PHS. We now show that intact serum also significantly enhanced neutrophil phagocytosis of Schu S4 relative to the no serum control (Fig. 10A). Furthermore, neither LVS-depleted PHS nor HI-PHS enhanced phagocytosis of Schu S4 above background, suggesting a role for Ab and complement in Schu S4 internalization. Indeed, when Abs were restored by supplementation of LVS-depleted PHS with HI-PHS or purified IgM, uptake of Schu S4 was markedly enhanced and was similar to the mock-depleted PHS. We conclude that serum-enhanced neutrophil phagocytosis of F. tularensis strain Schu S4 is complement-dependent and can be mediated by IgM in nonimmune serum.

FIGURE 10.

Phagocytosis of F. tularensis Schu S4 by human neutrophils also requires nonimmune IgM, complement, CR1 and CR3. A, Complement and IgM enhance Schu S4 uptake by PMNs. PMNs were incubated with Schu S4-sGFP (MOI 10:1) for 30 min in the absence of serum or with 20% PHS, 20% LVS-depleted serum, 20% HI-PHS, or 20% LVS-depleted serum supplemented with 20% HI-PHS or 75 μg/ml purified IgM. Cells were stored in fixative for 5 days prior to removal from BSL-3 and analysis by flow cytometry. Phagocytic indices are shown as the mean ± SEM (n=3). *P <0.001 vs. no serum; #P <0.001 vs. 20% mock-depleted PHS; ‡P <0.001 vs. 20% LVS-depleted PHS. B, CR1 and CR3 are critical for serum-mediated phagocytosis of Schu S4. Neutrophils were preincubated for 15 min at 4°C without Abs or with 15 μg/ml of anti-CD35 (CR1), anti-CD11b (CR3), anti-CD11c (CR4), anti-CD11a (LFA-1) blocking Abs or isotype control Abs. Thereafter, Schu S4-sGFP at an MOI 10:1 and 10% PHS were added and samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were stored in 4°C formalin for 5 days prior to analysis by flow cytometry. Phagocytic indices are shown as the mean ± SEM (n=3). * P <0.001 vs. 10% PHS; all other samples were not statistically significant by ANOVA. #P<0.05 vs. 10% PHS by Student’s t test.

To evaluate the roles of CR1, CR3, and CR4 in the serum-dependent uptake of Schu S4 by neutrophils, we repeated the receptor blocking experiments and measured phagocytosis by flow cytometry. Similar to data we obtained using LVS, blocking CR4 had no effect. On the other hand, blocking CR1 and CR3 individually reduced Schu S4 uptake in 10% PHS by 22% and 28%, respectively, and simultaneous blockade of both receptors diminished Schu S4 phagocytosis by more than 72% (Fig. 10B). Although analysis of all the data in Fig. 10B by ANOVA did not reveal statistically significant differences, a direct comparison of the PHS controls and cells treated with both CR1 and CR3 blocking Abs was significant by a two-tailed Student’s t-test (P= 0.0375). In this regard it is important to note that PMNs infected with Schu S4 were stored in fixative for 5 days prior to removal from BSL-3 and analysis by flow cytometry. This was necessary to ensure sample sterility but diminished GFP intensity, which likely contributes to the lower significance of this data set. Indeed, we found using sGFP-LVS that after 5 days in formalin, the MFI decreased by 50% relative to the original unfixed samples, whereas the percentage of infected PMNs was essentially unchanged (89% vs. 92%, respectively, data not shown). Similarly, the data in Figure 10 indicate that 84.4 ± 5.1% of PMNs were infected with Schu S4. Altogether, these data demonstrate that serum-enhanced phagocytosis of virulent F. tularensis strain Schu S4 is mediated by CR1 and CR3 on human neutrophils.

Human macrophage phagocytosis of F. tularensis Schu S4 and LVS is enhanced by nonimmune serum via IgM and complement, and is mediated by CR3 and CR4

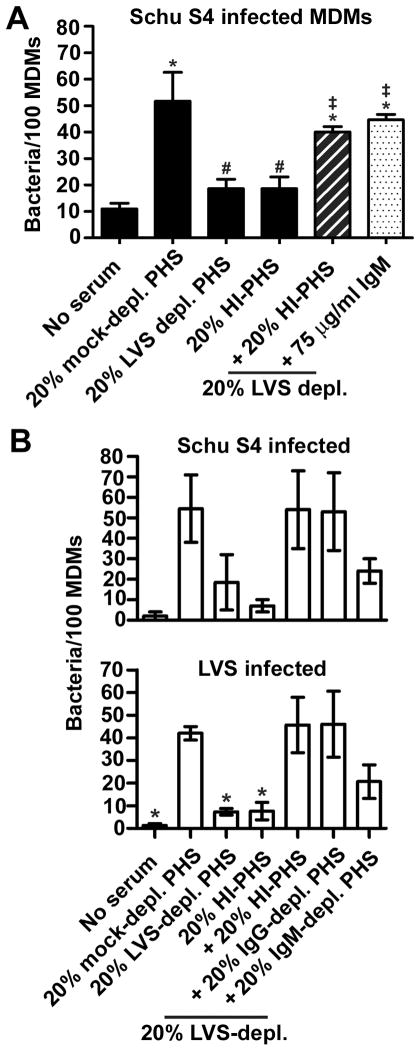

As serum also enhances uptake of F. tularensis by human macrophages and monocytes (6, 11, 12), we determined the role of natural IgM in this process. To this end, MDMs were incubated with Schu S4-sGFP at an MOI of 20:1 in serum-free medium or medium containing 20% mock-depleted PHS, 20% LVS-depleted PHS, 20% HI-PHS, or 20% LVS-depleted PHS supplemented with either 20% HI-PHS or 75 μg/ml purified IgM. At 60 min, the MDMs were washed and fixed, and PIs (number of bacteria/100 macrophages) were quantified by microscopy, using established methods for this cell type (12). As shown in Figure 11A, infection of MDMs in the absence of serum was inefficient and resulted in only 11.0 ± 2.0 Schu S4/100 macrophages. Conversely, phagocytosis was significantly more efficient in the presence of 20% PHS, and the number of bacteria internalized by MDMs increased fivefold (51.7 ± 10.9 Schu S4/100 cells). In contrast, neither LVS-depleted PHS nor HI-PHS significantly enhanced Schu S4 uptake relative to the no serum control (18.7 ± 3.5 and 18.7 ± 4.4 Ft/100 MDMs, respectively). However, supplementation of LVS-depleted PHS with HI-PHS or purified IgM restored Schu S4 uptake (40.0 ± 2.1 Ft/100 cells and 44.7 ± 2.0 Ft/100 cells, respectively). In another series of experiments we directly compared LVS and Schu S4 and tested the ability of IgG- or IgM-depleted PHS to reconstitute F. tularensis uptake by MDMs in 20% LVS-depleted PHS. Similar data were obtained for both bacterial strains, and the data shown in Figure 11B indicate that IgG-depleted PHS restored phagocytosis to the level seen with 20% mock-depleted PHS, whereas IgM-depleted serum did not.

FIGURE 11.

Phagocytosis of F. tularensis Schu S4 by MDMs is also enhanced by nonimmune serum via complement and IgM. A, MDMs were incubated with Schu S4-sGFP (MOI 20:1) at 37°C in media alone or in media supplemented with 20% PHS, 20% LVS-depleted serum, 20% HI-PHS, or 20% LVS-depleted serum supplemented with 20% HI-PHS or 75 μg/ml purified IgM as indicated. At 60 min, the MDMs were washed and fixed. Phagocytic indices were determined using confocal microscopy and are reported as the number of bacteria per 100 MDMs. Data shown are the mean ± SEM (n=3). *P <0.001 vs. no serum; #P <0.001 vs. 20% PHS; ‡P <0.001 vs. 20% LVS-depleted PHS. B, MDMs were infected with either Schu S4-GFP (n=2, top graph) or LVS-GFP (n=3, bottom graph) as described above except the 20% LVS-depleted PHS was supplemented with 20% HI-PHS, 20% IgG-agarose depleted PHS, or 20% IgM-agarose depleted PHS as indicated. *P<0.05 vs. 20% mock-depleted PHS.

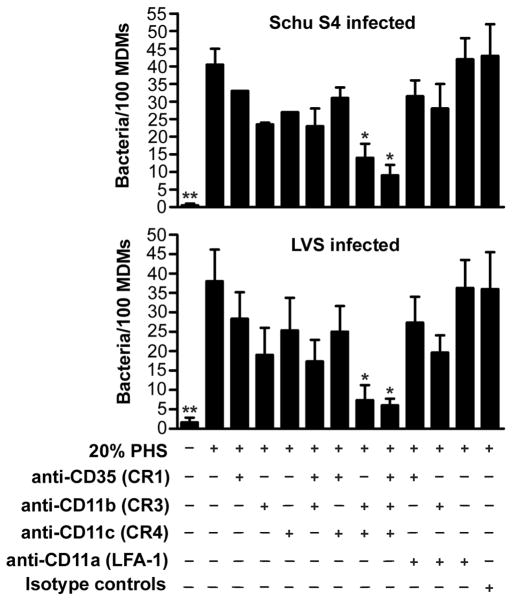

Our published data indicate a role for CR3, but not CR1 or LFA-1 in uptake of opsonized LVS by MDMs (12). We extended these studies here to include Schu S4 and also examined the role of CR4 in this process. The data in Figure 12 demonstrate that anti-CD11b and anti-CD11c Abs diminished F. tularensis phagocytosis in an additive manner. Thus, simultaneous blockade of CR3 and CR4 inhibited MDM uptake of Schu S4 and LVS by 71% and 81%, respectively (P<0.05). In contrast, blockade of CR1 alone reduced phagocytosis by only 15-27% and had little or no effect when tested in combination with Abs to CR3 or CR4. F. tularensis uptake was not affected by Abs to LFA-1 or the isotype controls. The same pattern of inhibition was obtained when we quantified the percentage of infected MDMs (data not shown). Collectively, our data indicate that distinct complement receptors are utilized during phagocytosis of opsonized F. tularensis by human macrophages and neutrophils.

FIGURE 12.

CR3 and CR4 mediate phagocytosis of opsonized F. tularensis by human macrophages. MDMs were preincubated with or without the indicated receptor-blocking or isotype control Abs (each at 30 μg/ml) for 15 min and then infected with sGFP-expressing Schu S4 (n=2, top graph) or LVS (n=3, bottom graph) at MOI of 20:1. After 1 h at 37°C, phagocytic indices were determined by microscopy. Data are the mean ± SEM and indicate bacteria per 100 MDMs. Statistical analyses were performed by ANOVA with a Dunnett’s post-test. **P<0.01 and *P<0.05 vs. 20% PHS.

DISCUSSION

Neutrophils play an important role in the severity and lethality of pneumonic tularemia as blockade of PMN influx into the lung significantly improves the survival of mice infected with LVS or Schu S4 (55). Nevertheless, our understanding of F. tularensis-neutrophil interactions is relatively rudimentary. To evade oxidative host defense this organism interferes with NADPH oxidase assembly and activation on forming phagosomes, and thereafter disrupts the phagosome membrane and replicates in PMN cytosol (7, 8, 31). Recent data indicate that F. tularensis also inhibits PMN apoptosis and profoundly prolongs cell lifespan (8), a phenotype that is indicative of a dysregulated and ineffective inflammatory response. Despite these advances, many aspects of infection are incompletely defined. We undertook this study to better define the mechanisms of F. tularensis phagocytosis by human neutrophils. We showed first that flow cytometry can be used to quantify bacterial uptake with high efficiency and sensitivity and then utilized a combination of depletion, purification and reconstitution strategies to confirm a role for the classical complement pathway, including C1q and C3, in F. tularensis opsonization by nonimmune serum. Most importantly, we extended previous work to define an essential role for natural IgM (but not IgG) in this process, and present evidence to suggest that LPS O-antigen and/or capsule are prominent targets of these antibodies on the bacterial surface. Finally, we demonstrated using specific blocking antibodies that distinct complement receptors are utilized for opsonophagocytosis of F. tularensis by human macrophages and neutrophils.

The central finding of this study is our demonstration that natural IgM in nonimmune serum from normal healthy donors is essential for classical pathway activation and C3 deposition on F. tularensis. Natural Abs are germline-encoded, are present in neonates as well as germ-free animals, and account for nearly all IgM in serum (27). In mice, natural Abs are produced by B-1a lymphocytes that reside in the pleural and peritoneal cavities as well as the spleen and accumulate in the draining lymph nodes in response to certain infections, such as influenza (27, 56). Although the equivalent cell population in humans is less well defined, the results of several studies indicate that these cells are self-renewing, and that Ab secretion occurs in the absence of exogenous antigenic stimulation but can be enhanced by cytokines such as IL-6 and exposure to Toll-like receptor ligands (27, 57). Due to their low affinity and high valency, most natural IgM exhibit polyreactive binding to targets of host and microbe origin that contain multiple repeating epitopes, including carbohydrates. As B-1a cells are excluded from germinal centers, natural Abs do not undergo affinity maturation, and this is thought to be essential for prevention of autoimmune disease (27, 57).

Although our data demonstrate that IgM is essential for F. tularensis opsonization, our results also suggest that Abs specific for this organism are limiting in PHS. In our hands, optimal infection of PMNs with LVS and Schu S4 was observed in medium containing 10-20% PHS, similar to published data which indicate that ≥10% serum was sufficient for neutrophil uptake of a virulent type B strain of F. tularensis as well as LVS (28). Yet at the same time we also noticed that when tested separately, sera from individual donors on our pool supported F. tularensis infection of PMNs to different extents, with maximal uptake achieved at concentrations of 2.5%-20% (Fig. 5A). Consistent with this, Li et al., have shown that among normal individuals the concentration of natural IgM in serum that is specific for a given antigen is highly variable and can differ at least tenfold (58). This normal variability of donor sera also provides a potential explanation to account for the failure of some previous studies to detect opsonophagocytosis of F. tularensis in nonimmune serum (28, 30). In keeping with this, we also noticed that F. tularensis opsonization and phagocytosis was strictly dependent upon bacterial concentration. Specifically, we find that infection was favored using F. tularensis at 5 × 107 CFU/ml in media containing 10–20% PHS (our standard conditions), or at 5 × 108 CFU/ml in medium containing 50% PHS, but in marked contrast, both IgM binding and C3 deposition were markedly reduced even in 50% PHS when F. tularensis was increased to 7.2 × 109 CFU/ml (Figs. 6D and 8B). Although we did not precisely define a “critical” bacterial concentration at which IgM is limiting in human serum (and we expect this to vary from donor to donor), our data indicate that there is a threshold below which the amount of IgM per bacterium is too low to support classical pathway activation, and we propose that in vitro experiments should account for potentially limiting concentrations of opsonins in future studies of complement activation by this pathogen.

There is ample evidence that LPS O-antigen and capsule allow Francisella to evade lysis by terminal complement components (2, 32, 33, 36–39). Recently, Apicella et al., used a combination of electron microscopy, genetics and biochemical fractionation to demonstrate that F. tularensis O-antigen and capsule are antigenically and biochemically distinct (48). Nevertheless, the same sugars are found in both of these structures, and there is considerable overlap in the genes required for capsule and O-antigen biosynthesis (36, 48). Consequently, some O-antigen mutants are also capsule-deficient, whereas others are not. For example, Schu S4 FTT1237 mutants are capsule-positive and O-antigen negative (36). wbtA is the first gene in an operon that is essential for synthesis of both O-antigen and capsule (37). We chose the LVS wbtA2 mutant for our current studies because data from several research groups indicate that strain lacks both these structures (8, 37, 48). The fact that wbtA2-depleted PHS did not impair phagocytosis of wild-type LVS strongly suggests that O-antigen and/or capsule are major targets of natural IgM on the bacterial surface that support classical pathway activation and opsonophagocytosis, results consistent with the propensity of natural IgM to target polymeric carbohydrates. These results are also of interest as the O-antigen and capsular polysaccharides of F. tularensis and F. novicida are antigenically and structurally distinct (2, 34, 59, 60), and our published data indicate that F. novicida binds IgG in PHS and fixes more C3 than LVS (34). Although this issue merits further study, the available data suggest that F. novicida may bind different or additional natural Abs that result in quantitative and/or qualitative changes in bacterial opsonization. The extent to which differences in opsonization of F. novicida and F. tularensis affect their relative virulence for humans remains unknown.

Complement opsonization is particularly important for the recognition, binding, and internalization of particles by neutrophils, including encapsulated bacteria. Phagocytes recognize complement opsonized particles using CR1 (CD35) which binds C3b, C4b, and C1q, and the integrins CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and CR4 (CD11c/CD18) that specifically bind iC3b. The results of this study demonstrate that these receptors are differentially utilized by human macrophages and neutrophils for uptake of opsonized F. tularensis. Specifically, we show that complement-dependent uptake of F. tularensis LVS and Schu S4 by human PMNs required both CR1 and CR3, whereas CR4 was dispensable. In contrast, CR3 and CR4 played dominant roles in F. tularensis infection of MDMs, and appeared to contribute equally to this process. These data confirm the ability of neutrophils use both CR1 and CR3 for phagocytosis (61), and extend previous work to show that, similar to dendritic cells (17), macrophages use CR4 as well as CR3 for uptake of opsonized F. tularensis (12, 14). Precisely what accounts for these preferences is unknown, but differential receptor expression likely plays a role as CR4 is tenfold less abundant on neutrophils than CR1 and CR3, whereas both CR3 and CR4 are highly enriched on macrophages and dendritic cells (62). At the same time, additional macrophage receptors that are known to contribute to F. tularensis uptake including the mannose receptor, nucleolin and scavenger receptor A likely contribute to the greater phagocytosis of F. tularensis by this cell type that occurs in the presence of LVS-depleted or IgM-depleted PHS that is not observed in PMNs (for example, compare Fig. 11 to Figs. 6C and 10A).

Although signaling through CR3 has been relatively well studied, less is known about the signaling events downstream of CR1 in PMNs, and the consequences of CR1 ligation are not well defined. Consistent with our data, other studies have reported that complement-mediated phagocytosis of certain target particles by neutrophils can be inhibited more efficiently when both CR1 and CR3 are blocked (61, 63, 64), but the mechanism by which CR1 and CR3 cooperate to facilitate uptake remains unclear. CR1 directly binds C3b-opsonzied bacteria (10), can act as a cofactor for factor I to facilitate conversion of C3b to iC3b (35, 65), and may participate in signaling required for particle uptake, including activation of phospholipase D (35, 61). Whether any of these interactions is required for F. tularensis phagocytosis remains to be determined, and the PMN receptors that mediate inefficient uptake of F. tularensis in the absence of serum opsonins also remain obscure.

In summary, the results of this study provide fundamental insight into the mechanism of F. tularensis opsonization and phagocytosis by human neutrophils. We demonstrate that natural IgM in nonimmune human serum is essential for phagocytosis of F. tularensis in a complement-dependent manner. Moreover, our data support a model in which natural IgM binding to O-antigen and/or capsular polysaccharides on the bacterial surface activates the classical complement pathway through C1q to enhance C3 deposition on the bacterial surface, which subsequently enhances phagocytosis via CR3 in combination with CR1 or CR4 on neutrophils and MDMs, respectively. These findings advance our understanding of the innate immune response to F. tularensis and set the stage for additional studies to elucidate the role these interactions may play in tularemia pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funds from the NIH/NIAID: R01AI073835-05 to L-.A.H.A, T32-AI007511 to J.T.S., and U54 AI057160-08 to L-A.H.A. and J.H.B. via the Midwest Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research (MRCE).

We are grateful to Dr. Alexander Horswill (University of Iowa) for providing the superfolder GFP gene and for assistance in generating the sGFP plasmid, to Dr. Theresa Gioannini (University of Iowa) for assistance with the purification of antibodies from serum, to Dr. Dara Frank (Medical College of Wisconsin) for sharing the LVS wbtA2 mutant, and to Dr. William Nauseef (University of Iowa) and Dr. Larry Schlesinger (The Ohio State University) for helpful discussions and advice. Drs. Allen and Barker also acknowledge support from the Midwest Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research.

Abbreviations

- AS

autologous serum

- BHIB

brain heart infusion broth

- CHAB

cysteine heart agar supplemented with sheep blood

- CR

complement receptor

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- HI

heat-inactivated

- HSA

human serum albumin

- LVS

live vaccine strain

- MDMs

monocyte-derived macrophages

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- PHS

pooled human serum

- PI

phagocytic index

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocyte

- sGFP

superfolder GFP

- subsp

subspecies

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors has a conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

J.T.S. and J.H.B. contributed equally to this work and designed and performed experiments, interpreted data and co-wrote the manuscript. J.K., designed and performed experiments and interpreted data. M.E.L., and J.M.M. designed and performed experiments, interpreted data and edited the manuscript. L.-A.H.A. designed experiments, interpreted data and co-wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ellis J, Oyston PCF, Green M, Titball RW. Tularemia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:631–646. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.4.631-646.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLendon MK, Apicella M, Allen LAH. Francisella tularensis: taxomony, genetics and immunopathogenesis of a potenial agent of biowarfare. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006;60:167–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pechous RD, McCarthy TR, Zahrt TC. Working toward the future: insights into Francisella tularensis pathogenesis and vaccine development. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:684–711. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00028-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oyston PCF, Sjostedt A, Titball RW. Tularemia: bioterrorism defence renews interest in Francisella tularensis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:967–978. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogler AJ, Birdsell D, Price LB, Bowers JR, Beckstrom-Sternberg SM, Auerbach RK, Beckstrom-Sternberg JS, Johansson A, Clare A, Buchhagen JL, Petersen JM, Pearson T, Vaissaire J, Dempsey MP, Foxall P, Engelthaler DM, Wagner DM, Keim P. Phylogeography of Francisella tularensis: Global Expansion of a Highly Fit Clone. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2474–2484. doi: 10.1128/JB.01786-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemens DL, Lee BY, Horwitz MA. Virulent and avirulent strains of Francisella tularensis prevent acidification and maturation of their phagosomes and escape into the cytoplasm in human macrophages. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3204–3217. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3204-3217.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCaffrey RL, Schwartz JT, Lindemann SR, Moreland JG, Buchan BW, Jones BD, Allen LAH. Multiple mechanisms of NADPH oxidase inhibition by type A and type B Francisella tularensis. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:791–805. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1209811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz JT, Barker JH, Kaufman J, Fayram DC, McCracken JM, Allen LAH. Francisella tularensis inhibits the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways to delay constitutive apoptosis and prolong human neutrophil lifespan. J Immmunol. 2012;188:3351–3363. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong A, Celli J. The Francisella intracellular life cycle: towards molecular mechanisms of intracellular survival and proliferation. Front Microbiol. 2010:1. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2010.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Underhill DM, Ozinsky A. Phagocytosis of microbes: complexity in action. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:825–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.103001.114744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geier H, Celli J. Phagocytic receptors dictate phagosomal escape and intracellular proliferation of Francisella tularensis. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2204–2214. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01382-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulert GS, Allen LAH. Differential infection of mononuclear phagoctyes by Francisella tularensis: role of the macrophage mannose receptor. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:563–571. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balagopal A, MacFarlane AS, Mohapatra N, Soni S, Gunn JS, Schlesinger LS. Characterization of the receptor-ligand pathways important for entry and survival of Francisella tularensis in human macrophages. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5114–5125. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00795-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemens DL, Lee BY, Horwitz MA. Francisella tularensis enters macrophages via a novel process involving pseudopod loops. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5892–5902. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5892-5902.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierini LM. Uptake of serum-opsonized Francisella tularensis by macrophages can be mediated by class A scavenger receptors. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1361–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barel M, Hovanessian AG, Meibom K, Briand JP, Dupuis M, Charbit A. A novel receptor-ligand pathway for entry of Francisella tularensis into monocyte-like THP-1 cells: interaction between surface nucleolin and bacterial elongation factor Tu. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]