Abstract

Our previous studies showed that bacterial heat shock protein 60 (hsp60) induces cultured epithelial cell proliferation within 24 h. Here we investigated the long-term effects of heat shock protein 60 isolated from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans on skin keratinocyte (HaCaT cell line) viability and the cell signaling involved. Prolonged incubation in the presence of hsp60 increased the rate of epithelial cell death. The number of viable cells in hsp60-treated culture was 37% higher than the number in the control at 24 h but 27% lower at 144 h. A kinetics study of the effect of hsp60 on the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) involving Western blotting with phospho-specific antibodies showed that in addition to a transient early increase in p38 levels, a second peak appeared in keratinocytes 24 h after the addition of hsp60. In contrast, prolonged incubation with hsp60 caused a decrease in the level of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) compared with that in the controls, possibly as a result of protein phosphatase activity. We found that hsp60 increased the levels of several phosphatases, including MAP-2, which strongly dephosphorylates ERK1/2. Moreover, hsp60 increased the level of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in culture medium in a dose-dependent manner. TNF-α added to culture showed a cytotoxic effect on epithelial cells, particularly with longer incubation periods. TNF-α also induced the phosphorylation of p38. Finally, our results show that bacterial hsp60 inhibited stress-induced synthesis of cellular hsp60. Therefore, several cell behavior changes caused by long-term exposure to bacterial hsp60 may lead to impaired epithelial cell viability.

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans has been identified as a major pathogenic bacterium in aggressive periodontal disease (13, 27). Several virulence factors have been identified in A. actinomycetemcomitans, including toxins and factors disturbing the host defense system (8). One consequence of bacterial infection in periodontal disease is the increased production of immune mediators, particularly proinflammatory cytokines (44). Thus, the destruction of periodontal tissues may result from the direct pathological effects of bacterial products and their indirect effects on the immune response. Among the cytokines most consistently found to be associated with periodontitis are tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-8, and prostaglandin E2 (33). TNF-α is produced by various cell types, including fibroblasts, monocytes, lymphocytes, and epithelial cells (36). A range of bacterial components, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), are involved in the induction of TNF-α production (32, 37). TNF-α has many biological activities and is involved in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases, including damage to connective tissue and bone loss (11). TNF-α stimulates the proliferation of many cell types through the activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (23). The effects of TNF-α on epithelial cells have not been well studied. One investigation showed that TNF-α has cytotoxic effects on intestinal epithelial cells through the activation of protein kinase C (3).

Heat shock protein 60 (hsp60) is a major bacterial antigen. It may play an important role in the pathogenesis of infection by mediating bacterial attachment to epithelial cells (9) and stimulating the host immune response (48). hsp60 derived from Yersinia enterocolitica and Helicobacter pylori induces the secretion of IL-8 from human gastric epithelial cells in culture, but hsp60 from Escherichia coli does not (43). It seems that the production and secretion of cytokines depend on both the cell type and the bacterial source of hsp60.

Our previous work showed that bacterial hsp60 stimulates epithelial cell proliferation after 24 h of incubation but that this effect is not observed for longer incubations (45). We hypothesize that hsp60 can stimulate epithelial cells to produce and secrete cytokines and/or negatively regulate the synthesis of cellular hsp60 and that these effects eventually result in increased epithelial cell death. In this study, we report the long-term effects of hsp60 on epithelial cell viability. The effects of bacterial hsp60 on the levels of TNF-α and intrinsic hsp60 in epithelial cells were also examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

GroEL-like heat shock protein (hsp60) was purified from A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 29522 by using ATP-agarose affinity chromatography and preparative sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The preparation was free of protein and LPS contaminants (15). Recombinant human hsp60 and antibodies against human hsp60 (with no cross-reactivity with bacterial hsp60) were obtained from StressGen Biotechnologies Corp. (Victoria, British Columbia, Canada). Anti-ACTIVE MAPK and Anti-ACTIVE p38 polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Promega (Madison, Wis.) 1-[3-(Amidinothio)propyl-1H-indoyl]-3-(1-methyl-1H-indoyl-3-yl)maleimide methane sulfonate (specific p38 inhibitor SB 203580) was purchased from Calbiochem (Ontario, Canada). TNF-α was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, N.Y.). The human TNF-α sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit was purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, Calif.). An RPN 2108 ECL Western blotting analysis system was purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, N.J.).

Cell culture.

The HaCaT cell line, comprising spontaneously transformed but nonmalignant human skin keratinocytes, was used in this study (2). Unless stated otherwise, HaCaT cells were cultured at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 IU of penicillin G/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml. Usually the cultures were allowed to grow to 80 to 90% confluence and were then switched to Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium without serum for 24 h prior to the cytotoxic assay or analysis of MAPK signaling pathways. For the MAPK inhibition experiments, cells were preincubated with SB 203580 (5 μM) at 37°C for 60 min prior to the addition of A. actinomycetemcomitans hsp60 (0.25 μg/ml, unless stated otherwise) or TNF-α (2 to 500 ng/ml).

Cytotoxic assay.

Five thousand HaCaT cells were seeded into each well of a 96-well culture plate and cultured to 80 to 90% confluence. To eliminate the interference of serum factors and to synchronize the cell cycle, the cells were starved of serum for 24 h before the test substances were added. The concentration of TNF-α used was between 2 and 200 ng/ml, and the period of TNF-α incubation was 24 to 148 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. In the TNF-α kinetics assay, the concentration of TNF-α was 2 ng/ml. The numbers of viable cells were determined with a CellTiter96 kit (Promega), with the absorbance of the color reaction being read at 570 nm with a Titertex Multiskan spectrophotometer. Six samples per product were evaluated.

Western blot analysis of MAPK activity.

Antibodies specific for phosphorylated, active forms of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and p38 were used in the Western blot analysis. After culture in 60-mm-diameter dishes, cells were collected into 600 μl of extraction buffer (25 mM HEPES, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 50 mM beta-glycerol phosphate, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate). Samples were heated at 95°C for 5 min, sonicated, and centrifuged for 10 min at 15,000 × g. Aliquots of 20 μl were mixed with 5 μl of 5× sample buffer and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Separated proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P transfer membranes (Millipore PLACE). Nonspecific binding was blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 5% skim milk for 90 min at room temperature. The filter was incubated with primary antibody for 3 h at room temperature. After washing in washing buffer three times (5 min each), the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin for 1 h at room temperature. After further washing (once for 15 min and four times for 5 min each), the bands were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. The levels of kinase bands were quantified by densitometric scanning and NIH image software analysis. To control for loading, the gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250.

Screening of protein phosphatases by Western blot analysis.

The levels of 24 protein phosphatases were analyzed in control and hsp60-treated samples by the commercial Kinetworks Phosphoprotein Screening (KPPS) 1.0 service offered by Kinexus Bioinformatics Corporation. The methodology involved in the Kinetworks immunoblotting analysis was published previously (30) and is available online at www.kinexus.ca. HaCaT cells were grown to 80% confluence and then deprived of serum for 24 h. After the addition of hsp60 (0.25 μg/ml) for 60 min, cells were collected and centrifuged. The cells were lysed by sonication in 1,000 μl of extraction buffer (25 mM HEPES, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 50 mM beta-glycerol phosphate, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate). Samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 15,000 × g at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined and adjusted to 1 mg/ml in sample loading buffer.

Western blot analysis of cellular hsp levels.

The effect of exogenous bacterial hsp60 on the heat shock-induced synthesis of cellular hsp was measured by Western blot analysis with specific antibody against human hsp60 (StressGen Biotechnologies). HaCaT cells were seeded in 60-mm-diameter dishes. At 70 to 80% confluence, cells were starved of serum for 24 h. Cells were incubated at 45°C for 30 min with or without bacterial hsp60 pretreatment for 60 min and were then incubated at 37°C (in 5% CO2 for 24 h). Western blotting was done as described above for MAPKs.

Human TNF-α sandwich ELISA.

The effect of bacterial hsp60 on TNF-α levels in epithelial cell culture supernatants was measured by using the human TNF-α sandwich ELISA kit (Chemicon). HaCaT cells in log phase were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 20,000 cells/well. At 70 to 80% confluence, the cells were starved of serum for 24 h. hsp60 was added to a final concentration of 0.02, 0.2, or 2 μg/ml, with six wells being used for each concentration. After incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h, cultured medium was collected and centrifuged (15,000 × g for 5 min).

The assay was conducted according to the Chemicon protocol. Briefly, 100 μl of culture supernatant was added to wells. Twenty-five microliters of diluted rabbit anti-human TNF-α antibody was dispensed into each well. The plate was incubated at room temperature for 3 h. After thorough washing of the wells, 50 μl of the diluted goat anti-rabbit-conjugated alkaline phosphatase was added. The plate was incubated at room temperature for 45 min. After the plate was washed, 200 μl of the prepared color reagent solution was added to each well and the plate was incubated at room temperature. Fifty microliters of stop solution was added to each well when the 1,000-pg standard well reached an optical density of 1.6. The color reaction was monitored at 490 nm on an ELISA reader.

Statistics.

For statistical analysis, Student's t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA; F test) was used for the effect of a single factor or multiple factors, respectively. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Bacterial hsp60 decreases viable numbers of keratinocytes in prolonged cultures.

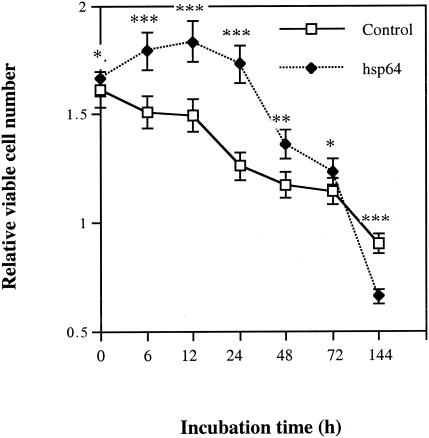

The viable cell number in the hsp60-treated group was higher than that in the control group until 72 h. In contrast, at 144 h of culture, the number of viable cells in the hsp60-treated group was 27% lower than that in the control group (Fig. 1). The effect was the same if the culture medium was changed and fresh hsp60 was added at each time point (data not shown). These data indicate that with a longer incubation period, one dose of bacterial hsp60 was sufficient to induce epithelial cell death.

FIG. 1.

Time course of hsp60 effect on keratinocyte viability. HaCaT cells at 70 to 80% confluence were deprived of serum for 48 h and then incubated with 0.25 μg of GroEL-like hsp (hsp60)/ml for different periods of time. The number of viable cells was determined by a colorimetric assay. Values shown are means ± standard deviations for six parallel cultures. *, P > 0.05; **, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 (Student's t test).

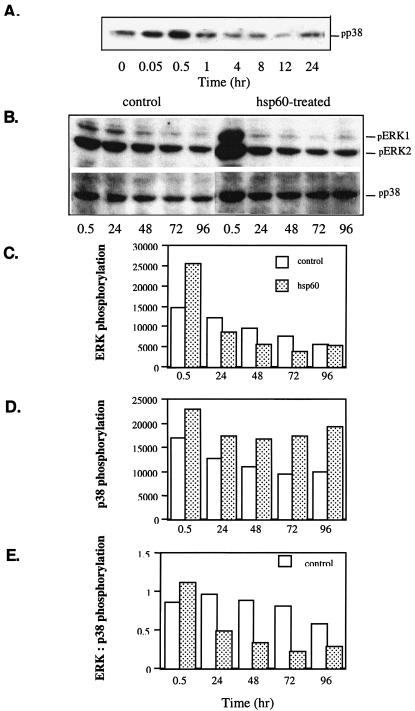

Prolonged treatment with bacterial hsp60 inhibits phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and stimulates phosphorylation of p38.

It is known that ERK1/2 is associated with cell proliferation and survival, and activation of p38 can be linked to cell death. We studied the levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and p38 in cells cultured in the presence of hsp60. hsp60 induced a transient phosphorylation of p38 that appeared at 3 min, reached its peak at 30 min, and then declined until 12 h. At 24 h, a secondary p38 phosphorylation peak appeared (Fig. 2A). Prolonged hsp60 exposure resulted in decreased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and increased phosphorylation of p38 compared to that for control cells (Fig. 2B to D). Thus, with prolonged exposure, the ratio of active ERK1/2 to active p38 MAPK was markedly lower in hsp60-treated cells than in control cells (Fig. 2E).

FIG. 2.

Effects of hsp60 on levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and p38 at different time points after addition of hsp60. (A and B) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated ERK1, ERK2, and p38; (C) scanned values of phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels in control and hsp60-treated groups; (D) scanned values of phosphorylated p38 levels in control and hsp60-treated groups; (E) comparison of ratios of ERK1/2 to p38 in control and hsp60-treated groups. The key given in panel C also applies to panels D and E.

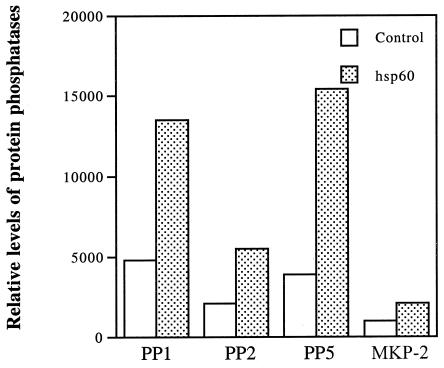

Bacterial hsp60 stimulation increases the levels of protein phosphatases in epithelial cell extract.

MAPK activity is regulated by the balance of phosphorylation, resulting in the activation of MAPKs and their dephosphorylation by protein phosphatases, leading to their inactivation. We showed previously that the rapid phosphorylation of three MAPKs by bacterial hsp60 is followed by the return of phosphorylation to the control level (45). For p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), this process takes only 2 h, but it requires 12 h for ERK1/2 (45). We hypothesized that activated protein phosphatases play a role in the decline of phosphorylated MAPK levels. The levels of 24 protein phosphatases in the hsp60-treated epithelial cell extracts were screened by the Kinetworks KPPS 1.0 immunoblotting analysis. Fourteen of 24 protein phosphatases were stimulated at least twofold after 60 min of hsp60 incubation. Two of 24 protein phosphatases showed decreased levels in hsp60-treated cells, and 5 protein phosphatases exhibited similar levels in both control and hsp60-treated cells. Figure 3 shows a comparison of the levels of four protein phosphatases in control and hsp60-treated groups.

FIG. 3.

Effects of hsp60 on the levels of protein phosphatases in keratinocytes. Protein phosphatase levels were measured by Western blot analysis and quantified by scanning densitometry.

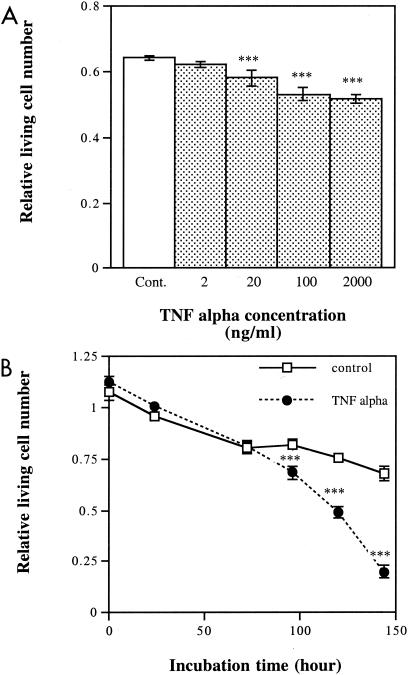

TNF-α reduces numbers of viable epithelial cells.

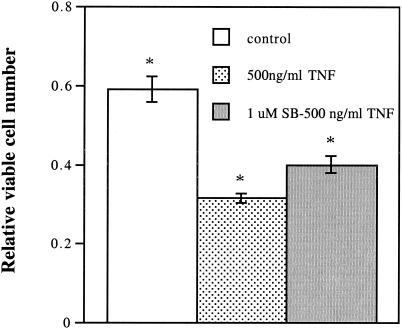

One possible reason for the reduction in cell viability by hsp60 is a secondary response leading to an increase in proapoptotic cytokine levels. We found that TNF-α exerted a cytotoxic effect on cultured keratinocytes (Fig. 4A and 5). The time and concentration studies showed that even low concentrations of TNF-α exerted strong toxic effects with incubation periods longer than 96 h (Fig. 4B). The number of viable cells in the TNF-α-treated group was 29% of that in control cultures at 144 h. The toxic effect of TNF-α was partially blocked by SB 203580, a specific inhibitor of p38 MAPK (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Dose- and time-dependent cytotoxic effects of TNF-α on keratinocytes. (A) Different concentrations of TNF-α were added to cultured keratinocytes starved of serum for 24 h, and numbers of viable cells were determined after 24 h of exposure. (B) The serum-starved keratinocytes were incubated with 2 ng of TNF-α/ml, and numbers of viable cells were determined at the indicated time points. Values shown are means ± standard deviations (optical density at 570 nm) for six parallel cultures. The difference between the results for the control treatment and those for the TNF-α treatment is significant at 20, 100, and 200 ng/ml (***, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Bartlett's posttest) and at 96, 120, and 144 h (***, P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni posttest). Cont., control.

FIG. 5.

Partial inhibition of TNF-α-induced cell death by SB 203580. Keratinocytes at 80% confluence were starved of serum for 24 h. The cells were preincubated with SB 203580, a p38-specific inhibitor, for 60 min and were then cultured with TNF-α for 24 h. Viable cells were determined by cell titer assay. Values shown are means ± standard deviations (optical density at 570 nm) for six parallel cultures. The difference between the results for the TNF-α treatment and those for the SB 203580-plus-TNF-α treatment is significant (*, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni posttests).

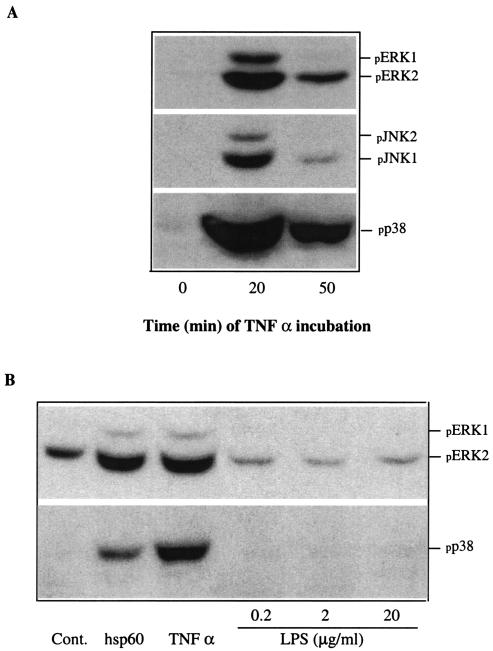

TNF-α strongly induces phosphorylation of MAPKs.

Since phosphorylation of JNK and p38 is involved in cell death, we tested the effects of TNF-α on the phosphorylation of MAPK. TNF-α moderately induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 and strongly induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (Fig. 6A). The p38 induction was clearly stronger than that caused by A. actinomycetemcomitans hsp60. E. coli LPS did not induce phosphorylation of either ERK1/2 or p38 at concentrations of 0.2 to 20 μg/ml (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Effects of TNF-α on the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK1/2, and p38 in keratinocytes. (A) HaCaT cells at 80% confluence were cultured in the absence of serum for 24 h and then in the presence TNF-α at 20 ng/ml for different times. (B) The effect of TNF-α treatment was compared to those of hsp60 (0.25 μg/ml) and E. coli LPS. The levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2, JNK1/2, and p38 were determined by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific antibodies. Cont., control.

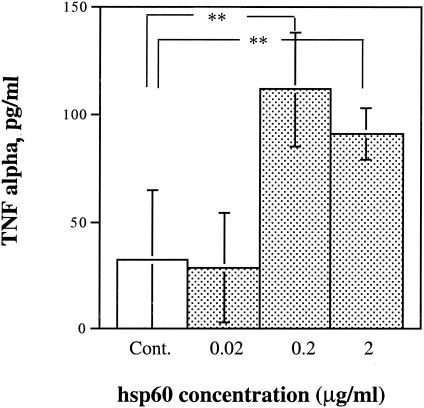

hsp60 induces keratinocytes to release TNF-α.

Keratinocytes produce constitutively small amounts of IL-1 and TNF-α, but their expression may be increased by bacterial exposure (24, 42). Bacterial hsp60 increased the level of TNF-α in the culture 2.5-fold (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Effect of hsp60 on levels of TNF-α in HaCaT cell culture medium. Keratinocytes deprived of serum for 24 h were cultured in the presence of different concentrations of hsp60 for 24 h. The TNF-α level in the cultured medium was determined with a human TNF-α sandwich ELISA kit. The color reaction was read at 490 nm. The values (means ± standard deviations) were calculated based on a standard curve. Elevated TNF-α levels are significant at 0.2 and 2 μg of hsp60/ml (**, P < 0.01, Student's t test). Cont., control.

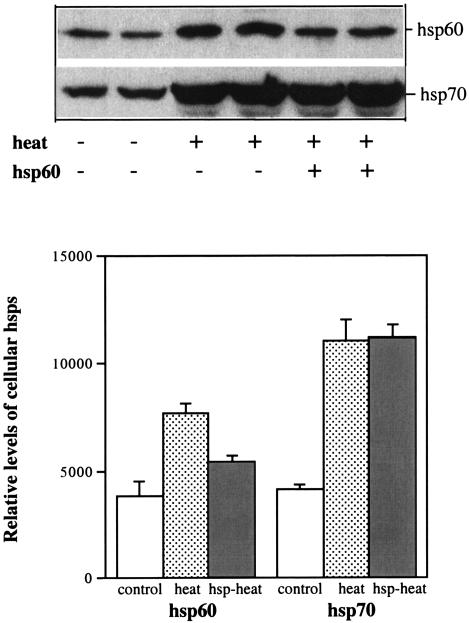

Exogenous hsp60 inhibits cellular hsp60 synthesis.

It is known that heat shock factor (HSF) is down-regulated by feedback through hsp binding to HSF. Activated ERK1/2 inhibits the transcriptional activity of HSF-1 through phosphorylation (5, 19). We tested the hypothesis that bacterial hsp has a negative effect on stress-induced cellular hsp synthesis in epithelial cells. First, we selected an appropriate temperature for studying the induction of the synthesis of cellular hsp60 and hsp70. Then, we pretreated the cells with hsp60 for 60 min and subjected them to heat shock. Heat shock incubation increased the level of cellular hsp60 twofold, and this increase was partially inhibited by bacterial hsp60 pretreatment. Heat shock also increased the level of cellular hsp70, but this increase was not inhibited by bacterial hsp60 pretreatment (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Effects of exogenous hsp60 on the heat shock-induced synthesis of cellular hsp60 and hsp70. Cultures of HaCaT cells at 80% confluence were starved of serum for 24 h and were then exposed to heat shock at 45°C for 30 min with or without hsp60 pretreatment. After heat shock, cells were cultured at 37°C for 24 h. Levels of cellular hsp60 and hsp70 were measured by Western blot analysis with anti-human hsp60 and hsp70 antibodies and quantified by scanning (lower panel).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that the short- and long-term responses of epithelial cells to bacterial hsp stimulation are quite different. Previously, we found that bacterial hsp60 stimulates epithelial cell proliferation, which peaks at 12 h after the addition of hsp60 (45). The maximum difference in viable cell numbers in the hsp60-treated group and the control group appears at 24 h; after that, the viable cell number declines much faster in the hsp60-treated group than in the control group. Since MAPKs ERK1/2 and p38 are involved in the regulation of cell survival or death, we studied the long-term hsp60 effect on the activation of these MAPKs. Our results showed that hsp60 strongly induces the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 relative to the control for 8 h. Further incubation resulted in a decline in ERK1/2 phosphorylation to below control values after 12 h of hsp60 stimulation. hsp60 also strongly induced a transient phosphorylation of p38. However, kinetic analysis shows that the level of phosphorylated p38 increased again 24 h after the addition of hsp60. The level of phosphorylated p38 was higher in the hsp60-treated group 24 h after hsp60 treatment than in the control group. This finding indicates that hsp60 had a short-term effect on epithelial cells involving the activation of ERK1/2 and increased cell proliferation. The long-term effect of hsp60, however, resulted in the sustained phosphorylation of p38 and an increased rate of cell death.

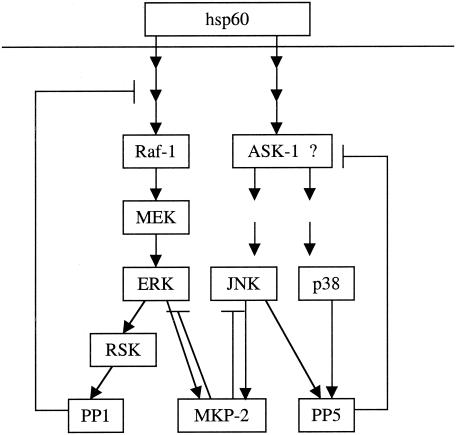

Biphasic activation of MAPK has been observed previously. For example, epidermal growth factor induces two peaks of ERK1/2 activation: one at 30 min and the other at 10.5 h (38). Nitric oxide induces a second peak of ERK1 activation 4 to 24 h after stimulation (16). TNF-α alone induces a transient activation of JNK, and pretreatment with actinomycin D or vanadate induces a second sustained JNK peak. This sustained JNK activation is associated with TNF-α-induced apoptosis (12). One possible factor involved in the change in kinetics of hsp60-induced MAPK activation is protein phosphatase activation. Our data show that hsp60 significantly increased the levels of several protein phosphatases, including PP1, PP2, PP5, and MAPK phosphatase 2 (MKP-2). It is reported that the Ras/MAPK/Rsk signaling pathway is involved in the activation of PP1 (31) and that ERK1/2 and JNK are strong activators of MKP-2 (4). PP1 and PP2 are both serine/threonine phosphatases and inhibitors of many kinases, including protein kinase C alpha, Akt, Bcl2, and Src (all upstream activators of the MAPK signaling pathway) and ERK (35, 40, 47). PP5 is also a serine/threonine phosphatase. PP5 inactivates apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (a MAPK kinase which strongly activates JNK and p38) through the dephosphorylation of an essential phosphothreonine residue (25). MKP-2 is a strong inhibitor of MAPK with a preference for ERK and JNK (4, 29, 46). Therefore, the decline in hsp60-induced activation of MAPKs can be attributed to hsp60-mediated negative feedback of activated protein phosphatases, as summarized in Fig. 9.

FIG. 9.

Proposed mechanism of hsp60-mediated activation and subsequent inactivation of MAPKs. hsp60 activates ERK1/2 through a Raf-1/MEK cascade, which in turn activates ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK). Activated ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 can increase the levels of protein phosphatases, including PP1, MKP-2, and PP5, which in turn negatively regulate the activity of MAPKs.

Another possible explanation for increased cell death during prolonged hsp60 exposure involves the induction of TNF-α. Our data show that bacterial hsp60 increased the level of TNF-α in the culture medium. Further, purified TNF-α strongly induced the phosphorylation of three MAPKs, particularly p38, and resulted in decreased numbers of epithelial cells in culture. These data indicate that the hsp60-induced increase in TNF-α production is partially responsible for the second activation of p38 and apoptotic cell death. We have found that the cell death caused by hsp60 in the long-term culture is at least partly apoptotic, supporting the idea that endogenous TNF-α might be responsible for the effect (unpublished data). The induced amounts of TNF-α, however, were small, and it is not known if they were large enough to cause a significant autocrine or paracrine effect.

Cell survival, proliferation, or death is regulated by levels of phosphorylated MAPK, especially by the ratio of ERK to p38. Earlier and present data show (i) that the ratio of phosphorylated ERK to p38 in log-phase-cultured keratinocytes was much higher than that in confluent keratinocytes deprived of serum for 24 h or longer (45), (ii) that hsp60 induced cell proliferation in a short-term culture through the activation of ERK1/2 and that this effect could be blocked through the inhibition of ERK1/2 activation by PD 98059 or promoted through the inhibition of p38 activation by SB 203580 (5) (in contrast, prolonged treatment with bacterial hsp60 resulting in increased cell death is also associated with a decrease in the ratio of phosphorylated ERK to p38), and (iii) that TNF-α strongly induced the phosphorylation of p38 and cell death and that the p38 inhibitor SB 203580 partially blocked these effects. Previous data showed that ERK1/2 and p38 exert positive and negative effects, respectively, on cyclin D1 expression, which controls cell proliferation through the transition from G0/G1 to S phase (21, 28).

It is well known that epithelial cells produce various cytokines and that these cytokines cause autocrine and paracrine effects. TNF-α is a proinflammatory cytokine that plays multiple roles, including the regulation of apoptosis. TNF-α induces apoptosis in human neutrophils and myelomonocytic leukemia cells (1, 26) but seems to play an antiapoptotic role in human eosinophils, cardiac myocytes, and rat hepatocytes (6, 34, 39). Therefore, it appears that the effect of TNF-α depends on cell type. The evidence presented here shows that TNF-α had a negative effect on keratinocyte viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner. High concentrations of TNF-α had toxic effects, and even low concentrations greatly increased cell death during prolonged treatment. This long-term toxic effect may result from an autocrine mechanism of TNF-α-induced production and the release of other cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (20, 22). We have observed that IL-1, like TNF-α, decreases epithelial cell viability in culture (L. Zhang et al., unpublished data). The phosphorylation of p38 may be involved in TNF-α-mediated epithelial cell death because the p38 inhibitor SB 203580 partially blocked TNF-α-mediated cell death. TNF-α-mediated p38 activation is involved in apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in some cells (41).

Cellular hsp60 is a crucial protein in the protection of cells against harmful effects of stress. The results of this study indicate that exogenous hsp may be involved in the down-regulation of the stress-induced synthesis of cellular hsp60. The mechanism behind this effect remains unclear. It is known that the activities of three MAPKs are involved in the phosphorylation of HSF-1, leading to inhibition of stress-induced hsp synthesis (7, 14, 18). We have found that PD 98059, an inhibitor of the ERK1/2 pathway, did not block bacterial hsp60-mediated inhibition of cellular hsp60 synthesis (data not shown). This finding indicates that the hsp60-induced activation of ERK1/2 may not be involved in the hsp60-mediated inhibition of cellular hsp synthesis. A body of evidence indicates that the synthesis of hsp's is negatively regulated by the accumulation of cellular hsp's through binding to HSF-1 and the inhibition of HSF-1 transactivation (17). The evidence from several studies indicates that exogenous hsp's can be internalized by cells. Because of a high homology to human hsp60, the exogenous hsp may inhibit cellular hsp synthesis through interaction with HSF-1. The inhibition of cellular hsp synthesis by bacterial hsp60 may sensitize the affected cells to stress and lead to decreased cell survival.

During chronic infections, such as periodontitis, long-lasting exposure to bacterial hsp60 may lead to increased amounts of epithelial cell death. Because A. actinomycetemcomitans may shed hsp60 in the membrane vesicles (10), it is possible that this protein is one of the important virulence determinants of the organism.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to D. Mayrand and D. Grenier (Groupe de Recherche en Ecologie Buccale, Universite Laval, Quebec, Canada) for providing hsp60. We also thank Jam Firth for his technical assistance and helpful discussion.

This study was supported by a grant from CIHR and Tonzetich Fellowship.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Avdi, N. J., J. A. Nick, B. B. Whitlock, M. A. Henson, G. L. Johnson, and G. S. Worthen. 2001. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathways in human neutrophils. Integrin involvement in a pathway leading from cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 276:2189-2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boukamp, P., R. T. Petrussevska, D. Breitkreutz, J. Hornung, A. Markham, and N. E. Fusening. 1988. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J. Cell Biol. 106:761-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang, Q., and B. L. Tepperman. 2001. The role of protein kinase C isozymes in TNF-alpha-induced cytotoxicity to a rat intestinal epithelial cell line. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 280:G572-G583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, P., D. Hutter, X. Yang, M. Gorospe, R. J. Davis, and Y. Liu. 2001. Discordance between the binding affinity of mitogen-activated protein kinase subfamily members for MAP kinase phosphatase-2 and their ability to activate the phosphatase catalytically. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29440-29449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu, B., F. Soncin, B. D. Price, M. A. Stevenson, and S. K. Calderwood. 1996. Sequential phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase and glycogen synthesis kinase 3 represses transcriptional activation by heat shock factor-1. J. Biol. Chem. 271:30847-30857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig, R., A. Larkin, A. M. Mingo, D. J. Thuerauf, C. Andrews, P. M. McDonough, and C. C. Glembotski. 2000. p38 MAPK and NF-kappa B collaborate to induce interleukin-6 gene expression and release. Evidence for a cytoprotective autocrine signaling pathway in a cardiac myocyte model system. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23814-23824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai, R., W. Frejtag, B. He, Y. Zhang, and N. F. Mivechi. 2000. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase targeting and phosphorylation of heat shock factor-1 suppress its transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18210-18218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fives-Taylor, P., D. Meyer, and K. Mintz. 1996. Virulence factors of the periodontopathogen Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Periodontol. 67:291-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garduño, R. A., E. Garduño, and P. S. Hoffman. 1998. Surface-associated Hsp60 chaperonin of Legionella pneumophila mediates invasion in a HeLa cell model. Infect. Immun. 66:4602-4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goulhen, F., A. Hafezi, V.-J. Uitto, D. Hinode, R. Nakamura, D. Grenier, and D. Mayrand. 1998. Subcellular localization and cytotoxic activity of the GroEL-like protein isolated from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 66:5307-5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graves, D. T. 1999. The potential role of chemokines and inflammatory cytokine in periodontal disease progression. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:482-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo, Y. L., K. Baysal, B. Kang, L. J. Yang, and J. R. Williamson. 1998. Correlation between sustained c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase activation and apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in rat mesangial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273:4027-4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gustke, C. J. 1998. A review of localized juvenile periodontitis (LJP): part I. Clinical features, epidemiology, etiology, and pathogenesis. Gen. Dent. 46:491-497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He, B., Y. H. Meng, and N. F. Mivechi. 1998. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta and extracellular signal-regulated kinase inactivate heat shock transcription factor 1 by facilitating the disappearance of transcriptionally active granules after heat shock. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6624-6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinode, D., R. Nakamura, D. Grenier, and D. Mayrand. 1998. Cross-reactivity of specific antibodies directed to heat shock protein from periodontopathogenic bacteria and of human origin. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 13:55-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huwiler, A., and J. Pfeilschifter. 1999. Nitric oxide stimulates the stress-activated protein kinase p38 in rat renal mesangial cells. J. Exp. Biol. 202:655-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, B. H., and F. Schoff. 2002. Interaction between arabidopsis heat shock transcription factor 1 and 70 kDa heat shock proteins. J. Exp. Bot. 53:371-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, J., A. Nueda, Y. H. Meng, W. S. Dynan, and N. F. Mivechi. 1997. Analysis of the phosphorylation of human heat shock transcription factor-1 by MAP kinase family members. J. Cell. Biochem. 67:43-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knauf, U., E. M. Newton, J. Kyriakis, and R. E. Kingston. 1996. Repression of human heat shock factor1 activity at control temperature by phosphorylation. Genes Dev. 10:2782-2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutsch, C. L., D. A. Norris, and W. P. Arend. 1993. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces interleukin-α and interkeukin-1 receptor antagonist production by cultured human keratinocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 101:79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavoie, J. N., G. L'Allemain, A. Brunet, R. Muller, and J. Pouyssegur. 1996. Cyclin D1 expression is regulated positively by the p42/p44 MAPK and negatively by the p38/HOG MAPK pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 271:20608-20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine, S. J., P. Larivee, C. Logun, C. W. Angus., and J. H. Shelhamer. 1993. Corticosteroids differentially regulate secretion of IL-6, IL-8, and G-CSF by a human bronchial epithelial cell line. Am. J. Physiol. 265:L360≽L368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, R. Y., C. Fan, G. Liu, N. E. Olashaw, and K. S. Zucherman. 2000. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for tumor necrosis factor-alpha-supported proliferation of leukemia and lymphoma cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 275:21086-21093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marionnet, A. V., Y. Chardonnet, J. Viac, and D. Schmitt. 1997. Differences in responses of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha production and secretion to cyclosporin-A and ultraviolet B-irradiation by normal transformed keratinocyte cultures. Exp. Dermatol. 6:22-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita, K., M. Saitoh, K. Tobiume, H. Matsuura, S. Enomoto, H. Nishitoh, and H. Ichijo. 2001. Negative feedback regulation of ASK1 by protein phosphatase 5(PP5) in response to oxidative stress. EMBO J. 20:6028-6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakada, S., T. Kawano, S. Saito-akita, S. Iwase, J. Horiguchi-Yamada, T. Ohno, and H. Yamada. 2001. MEK and p38 MAPK inhibitors potentiate TNF-alpha induced apoptosis in U937 cells. Anticancer Res. 21:167-171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nonnenmacher, C., R. Mutters, and L. F. de Jacoby. 2001. Microbiological characteristics of subgingival microbiota in adult periodontitis, localized juvenile periodontitis and rapidly progressive periodontitis subjects. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7:213-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page, K., J. Li, and M. B. Hershenson. 2001. p38 MAP kinase negatively regulates cyclin D1 expression in airway smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 280:L955-L964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paumelle, R., D. Tulasne, C. Leroy, J. Coll, B. Vandenbunder, and V. Fafeur. 2000. Sequential activation of ERK and repression of JNK by scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor in madin-darby canine kidney epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:3751-3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pelech, S., C. Sutter, and H. Zhang. 2003. Kinetworks protein kinase multiblot analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 218:99-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ragolia, L., and N. Begum. 1998. Protein phosphatase-1 and insulin action. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 182:49-58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddi, K., M. Wilson, S. Nair, and B. Henderson. 1996. Comparison of the pro-inflammatory cytokine-stimulating activity of the surface-associated proteins of periodontopathic bacteria. J. Periodontal Res. 31:120-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Research, Science, and Therapy Committee of the American Academy of Periodontology. 1999. The pathogenesis of periodontal diseases. J. Periodontol. 70:457-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts, R. A., N. H. James, and S. C. Cosulich. 2000. The role of protein kinase B and mitogen-activated protein kinase in epithermal growth factor and tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated rat hepatocyte survival and apoptosis. Hepatology 31:420-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruvolo, P. P. 2001. Ceramide regulates cellular homeostasis via diverse stress signaling pathways. Leukemia 15:1153-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandros, J., C. Karlsson, D. F. Lappin, P. N. Madianos, D. F. Kinane, and P. N. Papapanou. 2000. Cytokine responses of oral epithelial cells to Porphyromonas gingivalis infection. J. Dent. Res. 79:1808-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schytte Blix, I. J., K. Helgeland, E. Hvattum, and T. Lyberg. 1999. Lipopolysaccharide from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans stimulates production of interleukin-1beta, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in human whole blood. J. Periodontal Res. 34:34-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talarmin, H., C. Rescan, S. Cariou, D. Glaise, G. Zanninelli, M. Bilodeau, P. Loyer, C. Guguen-Guillouzo, and G. Baffet. 1999. The mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade activation is a key signalling pathway involved in the regulation of G1 phase progression in proliferating hepatocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6003-6011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsukahara, K., A. Nakao, M. Hiraguri, S. Miike, M. Mamura, Y. Saito, and I. Iwamoto. 1999. Tumor necrosis factor-α mediates antiapoptotic signals partially via p39 MAP kinase activation in human eosinophils. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 120:54-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ugi, S., T. Imamura, W. Ricketts, and J. M. Olefsky. 2002. Protein phosphatase 2A forms a molecular complex with Shc and regulates Shc tyrosine phosphorylation and downstream mitogenic signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2375-2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valladares, A., A. M. Alvarez, J. J. Ventura, C. Roncero, M. Benito, and A. Porras. 2000. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis in rat fetal brown adipocytes. Endocrinology 141:4383-4395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, B., N. Ruiz, A. Pentland, and M. Caparon. 1997. Keratinocyte proinflammatory responses to adherent and nonadherent group A streptococci. Infect. Immun. 65:2119-2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi, H., T. Osaki, N. Kurihara, M. Kitajima, M. Kai, M. Takahashi, and H. Taguchi. 1999. Induction of secretion of interlerkin-8 from human gastric epithelial cells by heat-shock protein 60 homologue of Helicobacter pylori. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:927-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zadeh, H. H., F. C. Nichols, and K. T. Miyasaki. 1999. The role of the cell-mediated immune response to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 20:239-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang, L., S. L. Pelech, D. Mayrand, D. Grenier, J. Heino, and V. J. Uitto. 2001. Bacterial heat shock protein-60 increases epithelial cell proliferation through the ERK1/2 MAP kinases. Exp. Cell Res. 266:11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, T., M. W. Wolfe, and M. S. Roberson. 2001. An early growth response protein (Egr)1 cis element is required for gonadotropin-releasing hormone-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 2 gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 276:45604-45613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou, B., Z. X. Wang, Y. Zhao, D. L. Brautigan, and Z. Y. Zhang. 2002. The specificity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 dephosphorylation by protein phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 277:31818-31825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zügel, U., and S. H. Kaufmann. 1999. Role of heat shock proteins in protection from and pathogenesis of infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:19-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]