Tuberculosis remains a worldwide threat despite the availability of the BCG vaccine and antibiotic treatment. It is estimated that its etiologic agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, infects almost a third of the human population and kills two million people every year (27). The recent human immunodeficiency virus pandemic, the selection of multidrug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis, and the increased immigration from countries with a high tuberculosis incidence, coupled with increasing poverty and homelessness in these countries, have awakened the developed nations from the widespread apathy toward tuberculosis (36). Indeed, recent years have seen great progress in the molecular characterization of this efficient human pathogen (26, 61). However, much work is still needed to understand how M. tuberculosis copes with the numerous environments it encounters in the course of a successful infection. Adaptation to such conditions must require a complex regulation of gene expression.

The main stresses faced during infection can be summarized as follows. The first stress is exposure to oxidizing agents, principally represented by the reactive oxygen intermediates and reactive nitrogen intermediates, produced by activated macrophages. The second is exposure to low pH. Even if M. tuberculosis is able to block phagosome acidification, this block is not complete as the mycobacterial phagosome undergoes a slight decrease in pH (21). The third is damage of surface structures. Alveolar surfactant is a mild detergent with antibacterial activity and could damage the structure of its fatty acid-rich cell envelope. In addition, toxic peptides and proteins like granulysin, thought to act at the level of the bacterial surface, are released by activated macrophages and NK cells. Specifically, granulysin has been recently shown to be essential for M. tuberculosis killing after apoptosis of infected macrophages induced by NK cells (22). Finally, toxic free fatty acids, secreted from macrophages both inside the mycobacterial phagosome and in the external environment, exhibit their toxicity when interacting with the mycobacterial surface (2). The fourth is hypoxia, especially inside granulomas but also inside the phagosome. This environmental condition is actually the best candidate for the induction of persistence (also called dormancy or latency), a phenomenon of great importance in M. tuberculosis pathogenesis but still not well understood at the molecular level (68). Recent experiments have implicated the transcriptional regulator DosR (dormancy survival regulator) (10, 51, 71), also known as DevR (18), and the response regulator MprA (72) in mycobacterial persistence. Interestingly, Voskuil et al. (67) recently showed that the DosR regulon is induced following NO-dependent inhibition of aerobic respiration. The fifth is nutrient and essential-element starvation. Inside phagosomes and granulomas, the availability of nutrients and essential elements may be reduced, as was recently shown for iron (31; J. Timm et al., unpublished data) and Mg2+ (12; S. Walters and I. Smith, unpublished data). Also, during transmission (between expulsion from an infected patient and inhalation by a new host), M. tuberculosis must face other environmental stresses such as nutrient starvation, exposure to UV light, dehydration, and low temperature.

The M. tuberculosis genome (14, 29) encodes about 190 transcriptional regulators: 13 σ factors, 11 two-component systems, 5 unpaired response regulators, 11 protein kinases (3), and more than 140 other putative transcriptional regulators (9). Several of these regulators have been characterized; some of them respond to environmental stresses such as cold shock (60), heat shock (41, 63), hypoxia (18, 51, 59), iron starvation (56), surface stress (41), and oxidative stress (42, 55), while others respond to still unknown environmental conditions (28, 52, 72). The resulting picture is still incomplete, but it suggests very complex regulatory systems with overlapping functions and redundancies. For example, the heat shock response is determined by the activation of five overlapping regulons under the transcriptional control of three σ factors (SigB, SigE, and SigH) (41, 42, 43) and two other transcriptional regulators (HspR and HrcA) (63).

In this review, we will principally discuss σ factors. Prokaryotic core RNA polymerase (RNAP) is composed of four distinct subunits: β, β′, ω, and an α dimer. A fifth subunit, the σ factor, reversibly associates with RNAP, forming the RNAP holoenzyme, and provides the promoter recognition function. The number of σ factors encoded in a genome is quite variable and ranges from a minimum of one in Mycoplasma sp. (30, 37) to a maximum of 65 in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) (6). M. tuberculosis encodes 13 different putative σ factors (14, 32, 34). It is generally observed that every σ factor has its own specificity, allowing the initiation of transcription of different subsets of genes. Genes belonging to a defined regulon often participate in related cellular functions. Therefore, temporal variation in active σ factor populations may represent a powerful way for M. tuberculosis to modulate its gene expression profiles in accordance with physiological requirements and thus achieve a successful infection.

CLASSIFICATION OF σ FACTORS

σ factors can be divided in two groups that are phylogenetically distinct: those related to σ70 and those related to σ54 (70). While all eubacteria encode at least one σ factor belonging to the σ70 class, not all of them encode one belonging to the σ54 class. Since the latter family of σ factors is not represented in mycobacteria, it will not be discussed any further. The σ70 family can be further divided into three groups, depending on their structure and function: (i) primary σ factors, (ii) nonessential primary factor-like σ factors, and (iii) alternative σ factors (70). All eubacterial genomes encode one primary σ factor. It is usually essential and allows the transcription of housekeeping genes. Escherichia coli σ70 and Bacillus subtilis σA are part of this category, and in M. tuberculosis, this group is represented by σA (23, 33).

The σ factors belonging to the second group (primary factor-like σ factors) are nonessential under standard physiologic growth conditions and are highly similar to primary σ factors. They can be involved in different functions. In enterobacteria, they are usually involved in stationary-phase survival (RpoS); in cyanobacteria, they are involved in the circadian cycle and in carbon and nitrogen utilization (σB and σC of Synechococcus sp.); and they are involved in antibiotic biosynthesis in streptomycetes (HrdD) (70). In M. tuberculosis, they are represented by σB (23).

The third group, that of alternative σ factors, is the most heterogeneous and can be divided into numerous subgroups. In M. tuberculosis, they are represented by σF (20), belonging to the subgroup that also contains the stress response-sporulation σ factors in bacilli and streptomycetes, and by σC, σD, σE, σG, σH, σI, σJ, σK, σL, and σM, belonging to the subgroup of the extracellular function (ECF) σ factors. ECF σ factors are environmentally responsive regulators, and bacteria usually contain several members of the ECF family that control a variety of functions in response to specific extracellular environmental signals, such as the presence of misfolded proteins in the periplasm, the presence of light, changes in osmolarity or barometric pressure, and the presence of toxic molecules in the external environment (45, 70). Examples are E. coli σE, which controls the response to extreme heat shock (1); AlgU, which controls alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa; FecI, which controls iron uptake in E. coli; CarQ, which controls carotenoid biosynthesis in Myxococcus xanthus; and P. syringae HrpL, which controls the synthesis of a virulence factor that functions during plant infections (45, 70).

MYCOBACTERIAL σ FACTOR GENOMICS

In addition to the annotated M. tuberculosis H37Rv and CDC1551 genomes (14, 29), almost complete DNA sequence data are now available for several mycobacterial species. Examination of these genomes shows that σ factor genes and their loci are well conserved across the genus, even though there are some exceptions. In Table 1 are listed the orthologs of the 13 M. tuberculosis σ factors in other mycobacterial species.

TABLE 1.

Sigma factor genes in mycobacteriaa

| Gene | Presence in:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis | M. bovis | M. bovis BCG Pasteur | M. leprae | M. avium | M. paratuberculosis | M. marinum | M. smegmatis | |

| sigA | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| sigB | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| sigC | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| sigC like | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| sigD | + | + | + | P | + | + | + | + |

| sigE | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| sigF | + | + | + | P | + | + | + | + |

| sigF like | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| sigG | + | + | + | P | + | + | + | + |

| sigH | + | + | 2+ | P | + | + | + | + |

| sigI | + | + | − | P | − | − | − | − |

| sigJ | + | + | + | P | + | + | + | + |

| sigK | + | + | + | P | − | − | + | − |

| sigL | + | + | + | − | P? | + | + | + |

| sigM | + | P? | 2+ | P | + | + | + | + |

| Other ECFs | − | − | − | − | 4+ | 4+ | 4+ | 8+? |

+, presence of the gene; −, absence of the gene; P, pseudogene. The analysis was performed by using BLASTX nework services. Genes listed as present were located in the same genetic locus as their M. tuberculosis orthologs and encoded putative proteins at least 68% similar to their M. tuberculosis counterparts.

The locus containing the genes encoding the principal and principal factor-like σ factors (sigA and sigB) is well conserved in the completely sequenced mycobacterial genomes available for analysis (23; R. Provvedi, unpublished data).

Interestingly, M. leprae sigF is a pseudogene and M. avium and M. paratuberculosis have two genes encoding a σF-like protein in different chromosomal loci. Of the two sigF-like genes, only the one encoding a σF-like protein with greater similarity to M. tuberculosis σF is preceded by the gene encoding its own putative negative regulator (anti-σ factor), UsfX, as in M. tuberculosis (Provvedi, unpublished).

The genes encoding the ECF σ factors show more variability. As previously reported, massive gene decay has occurred in M. leprae, in which only sigC and sigE have functional homologs. All of the other ECF σ genes are pseudogenes, with the exception of sigL, whose locus is deleted (15). It has recently been proposed that the loss of functional σ factors initiated pseudogene accumulation in this bacterium (4). In contrast, all M. tuberculosis ECF σ factor genes have an ortholog in M. bovis. The annotated sigM locus is a pseudogene, but this could be due to a mistake in the available sequence, which is not yet completely assembled. However, M. bovis BCG Pasteur lacks sigI as this locus is deleted, while in its genome, the sigH and sigM loci are duplicated (11).

Other differences we noted in the M. avium and M. paratuberculosis genomes are the lack of clear orthologs of sigK and sigI and the presence of four ECF σ factor genes encoding putative proteins similar to SigI/SigJ, suggesting that these species have more ECF σ factors than M. tuberculosis (Provvedi, unpublished). In M. avium, sigL has a frameshift, but as is the case for sigM in M. bovis, this could also be due to a mistake in the available sequence. In M. marinum, we could find clear orthologs for all of the 13 M. tuberculosis σ factors, with the exception of sigI. As in M. avium and M. paratuberculosis, we also found four additional ECF σ factors genes. One of these encodes a protein very similar to σC (Provvedi, unpublished).

The genome that shows the ECF σ factor gene pattern that is the most different from that of M. tuberculosis is that of the fast-growing mycobacterium M. smegmatis. It was not possible to find orthologs of sigC, sigI, and sigK, but there are at least seven or eight additional open reading frame showing similarity to ECF σ factor genes in this genome (Provvedi, unpublished). Also in this case, the genome sequence data, reportedly complete, are not yet assembled, preventing a complete and accurate analysis. The data extracted from these genomes support a rough correlation between the number of σ factors encoded in a genome and the diversity of possible niches for a given bacterium.

EXPRESSION OF M. TUBERCULOSIS σ FACTORS

All of the 13 M. tuberculosis σ factors are expressed during exponential growth (38, 41). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR showed that the amount of sigA-specific mRNA is constant during exponential growth and that it can be used as an internal invariant standard for mRNA quantitation when cells are growing either in broth or in macrophages (25). The mRNA levels of some σ factors change when the cells are subjected to stress; e.g., both sigB and sigE mRNA levels increase when the cells are exposed to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-induced surface stress (41, 43). Levels of the same two mRNAs and that of sigH also increase after heat shock and exposure to diamide (a thiol-specific oxidizing agent) (41, 42). It is interesting that sigF, sigE, and sigH were induced during infection of macrophages, suggesting their involvement in virulence (35). Other studies have recently shown that sigB, sigF, sigE, and sigD were induced after prolonged nutrient starvation (8). Finally, sigJ was recently shown to be induced in stationary-phase cultures, and the high level of sigJ mRNA was maintained after a 5-day treatment with rifampin (38).

σ FACTOR POSTTRANSLATIONAL REGULATION IN M. TUBERCULOSIS

Even though mRNA levels of σ factor genes are frequently induced under a given condition, the activity at the protein level may also be regulated by a family of proteins called anti-σ factors. These proteins can bind to a specific σ factor, keeping it in an inactive form. In the presence of a specific stimulus, the anti-σ factor releases the σ factor, which becomes active. Moreover, another class of proteins, the anti-anti-σ factors, can inhibit anti-σ factor activity (39). M. tuberculosis alternative σ factors σE, σF, σH, and σL are each closely linked to a gene encoding a putative anti-σ factor. The M. tuberculosis genome contains another putative anti-σ factor-encoding gene (Rv0093c), not associated with any σ factor gene, and seven genes encoding putative anti-anti-σ factors. The function of some of these molecules will be discussed later.

σA, THE PRIMARY σ FACTOR

σA (also known as RpoV) is believed to be the principal σ factor of M. tuberculosis because inactivation of its genetic determinant, sigA, has not been possible in both M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis (33; J. Timms and I. Smith, unpublished data). Its consensus promoter sequence is shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Consensus promoter sequences of M. tuberculosis sigma factors

| Sigma factor | Consensus sequencea | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| SigA | TTGACW-N17-TATAMT | 66 |

| SigF | GTTT-N17-GGGTAT | 5, 13 |

| SigC | SSSAAT-N16-20-CGTSSS | W. R. Bishai, personal comunication |

| SigE | GGRMC-N18-SGTTG | 43 |

| SigH | SGGAAC-N17-22-SGTTS | 40, 42, 55 |

W = A/T; S = G/C; R = A/G; M = A/C.

It was the first mycobacterial σ factor to be associated with virulence. An arginine-to-histidine substitution at amino acid residue 515 (R515H) caused attenuation of M. bovis virulence in a guinea pig model of infection (16). This mutation was localized to the C terminus of the protein, in a conserved domain known to interact with transcriptional activators in other bacteria (24). Since the mutant strain grew normally in vitro, it was suggested that the mutant protein was still able to drive the expression of the housekeeping genes but was deficient for binding to some virulence-specific transcriptional activators. It was recently shown that σA interacts with the putative transcriptional regulator WhiB3 and that this interaction is lost in the R515H mutant (64). Interestingly, a deletion of whiB3 in M. bovis resulted in attenuation of M. bovis virulence as in the original sigA R515H mutant, but an M. tuberculosis whiB3 mutant was only partially attenuated for virulence. Since σA is the same in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, this different phenotype is probably due to their different genetic backgrounds (64). The WhiB family in M. tuberculosis includes seven members. Related proteins in Streptomyces coelicolor are involved in sporulation, septation, and cell wall deposition (62).

σB, A PRIMARY FACTOR-LIKE σ FACTOR

sigB, the gene encoding σB, is almost identical to the last 600 bp of sigA and is localized approximately 3 kb downstream of sigA in all of the mycobacterial species thus far analyzed (23). In contrast to the latter, sigB is dispensable for growth both in M. smegmatis and in M. tuberculosis (M. Gomez and I. Smith, unpublished data). An M. tuberculosis sigB knockout mutant is more sensitive to various environmental stresses, such as SDS-induced surface stress, heat shock, and oxidative stress, but it is still able to grow normally in human macrophages and is not attenuated in mice (Gomez and Smith, unpublished). sigB regulation is complex; it is induced following exposure to surface or oxidative stress and after heat shock (41). Moreover, its transcription under physiological conditions and its induction after surface stress are dependent on σE, while during heat shock or oxidative stress, its induction is dependent on σH (42, 55). In vitro transcription experiments recently showed that the sigB promoter can be transcribed by RNAP containing σE, σH, or σL, suggesting the necessity for its induction under very different stress conditions (S. Rodrigue et al., unpublished data).

The subdomains of σB that are responsible for promoter recognition are almost identical to those of σA (23, 53). It is thus tempting to speculate that σA and σB recognize similar promoter sequences and that their respective regulons partially overlap, as is the case with RpoS and σ70 in E. coli (65). σB could function as a “backup” to maintain the transcription of essential housekeeping genes during exposure to stress, when σA could be inactive or its levels could be lowered. The role of σB will be clarified when more genes that require it for their transcription are identified. In this regard, it was reported that overexpression of σB in M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG caused an increase in katG expression, but it is not known whether this is a direct transcriptional effect (46). To generate a better σB consensus sequence, we are currently using DNA microarrays to find more genes in the σB regulon and preliminary results indicate that several heat shock genes require σB for their expression (P. Fontan and I. Smith, unpublished data).

σF, A σ FACTOR REQUIRED FOR FULL VIRULENCE

sigF, encoding σF, is part of a gene cluster with an organization similar to that of the B. subtilis sigF and sigB operons. In this locus, the anti-sigma factor-encoding gene usfX (originally annotated rsbW like in the Tuberculist database; RsbW is the B. subtilis ortholog) is directly upstream of the σ factor gene (19). In B. subtilis, σF is involved in sporulation, while σB is a general stress response σ factor whose expression is activated by heat, alcohol, osmotic stress, and entry into stationary phase (70). The M. tuberculosis gene encoding σF is induced in M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG after exposure to several antibiotics, hypoxia, cold shock, oxidative stress, and entry into stationary phase (20, 44). However, its induction was not observed in M. tuberculosis after cold shock, hypoxia, oxidative stress, or entry into stationary phase (38, 41). This suggests that sigF is regulated differently in M. bovis and M. tuberculosis, despite the similarity of these organisms. These findings, together with those regarding the difference between the effects of whiB3 inactivation in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, discussed above, suggest that caution should be used when extrapolating results obtained in one species when coping with phenomena as complex as global gene regulation and virulence.

usfX and sigF are transcribed from the σF-dependent promoter usfXP1 (Table 2), located directly upstream of usfX. The activity of σF is posttranslationally regulated by its cognate anti-sigma factor, UsfX. The latter protein is in turn posttranslationally regulated by two anti-anti-sigma factors, RsfA and RsfB. Both are able to disrupt the UsfX-σF complex, releasing σF to allow its association with RNAP. The function of RsfA is regulated by redox potential, while it is postulated that the activity of RsfB is controlled by phosphorylation (5).

An M. tuberculosis CDC1551 mutant lacking sigF was produced to investigate its role in virulence and stress response. Interestingly, the mutant strain reached stationary phase later than the wild-type (WT) parental strain and did not exhibit the typical lag phase after dilution of a dense culture into fresh medium. The mutant had the same sensitivity as the WT parent strain to heat shock, cold shock, hypoxia, and long-term stationary-phase growth; however, it was more sensitive than the WT to rifampin. Also, when used to infect human monocytes, the mutant did not show any difference from the WT. However, it was attenuated for virulence in mice when death was used as a criterion (13).

The σF regulon was studied by using DNA arrays in order to identify genes that require σF for their expression (W. R. Bishai, personal communication), and a consensus sequence was formulated that closely resembles the usfX promoter previously shown to be transcribed by σF-RNAP (5).

σC, AN ECF σ FACTOR REQUIRED FOR MOUSE LETHALITY

σC was recently inactivated in M. tuberculosis (Bishai, personal communication). The resulting strain was more susceptible to hydrogen peroxide and diamide stress but was not altered for survival in activated mouse macrophages. However, it was significantly attenuated in time-to-death experiments in the mouse model. Functional genomic studies with DNA arrays showed that at least 38 genes are repressed in the sigC mutant at different point of the growth curve. Those genes encode proteins involved in a broad range of cellular processes like fatty acids biosynthesis, phospholipid and cell wall biosynthesis, energy metabolism, and general stress response. A σC consensus sequence has been proposed from microarray data (Table 2) (Bishai, personal communication).

σE, AN ECF σ FACTOR ESSENTIAL FOR VIRULENCE INVOLVED IN RESPONSE TO SURFACE STRESS

The gene encoding σE is induced after exposure to various environmental stresses, such as heat shock and detergent-induced surface stress (41), as well as during M. tuberculosis growth in human macrophages (35). Interestingly, Schnappinger et al. (58) recently showed by functional genomics that a set of σ-dependent genes are induced in the phagosomal environment. A mutant of M. tuberculosis H37Rv lacking a functional sigE gene is more sensitive than the WT parent strain to detergent, high temperature, and oxidative stress. This mutant is attenuated for growth in THP-1-derived macrophages and is more sensitive than the WT strain to the killing activity of activated murine macrophages (43). Moreover, the sigE mutant has reduced virulence both in BALB/C and in SCID mice (R. Manganelli et al., submitted for publication). DNA array experiments comparing the transcriptome of the sigE mutant with that of the WT strain showed that 38 genes require σE for their full expression during exponential growth, while 13 putative transcriptional units containing 23 genes required σE for their induction after exposure to a subinhibitory concentration of SDS (43). Nine of the 13 putative transcriptional units were preceded by a conserved ECF σ factor-like promoter (Table 2), suggesting their direct transcriptional dependence on σE. The genes whose expression during exponential growth require σE include genes encoding proteins involved in translation, transcriptional control, mycolic acid biosynthesis, electron transport, and oxidative stress response. Interestingly, one of these genes is sigB, whose transcription under unstressed conditions is almost totally due to σE. Since sigB is the only gene of this group to be preceded by an ECF σ factor-like promoter, this suggests that at least some of the other 37 genes downregulated in the sigE mutant are in the σB regulon. Most of them are housekeeping genes, supporting the hypothesis that σB and σA have overlapping regulons. This question is currently being investigated.

Genes requiring σE for SDS-mediated induction encode heat shock proteins, proteins involved in fatty acid degradation, transcriptional regulators (including σB), and surface-exposed proteins with unknown function. The presence in this group of fadE23 and fadE24 is of particular interest. They were previously found to be induced after exposure to isoniazid, and it was hypothesized that their protein products could be involved in the degradation of the fatty acids accumulating on the surface as a consequence of the block of mycolic acid biosynthesis (69). The σE-dependent induction of these genes (together with others encoding fatty acid degradation enzymes) after exposure to a detergent supports the hypothesis of their role (and that of σE) in cell wall physiology and structure.

The gene encoding σE is followed by an operon including three genes. The first, Rv1222, encodes a σE-specific anti-σ factor (RseA) (Rodrigue et al., unpublished). The second, htrA, encodes a putative membrane serine protease; the third, tatB, encodes a putative protein belonging to the Tween arginine translocator (Tat) secretion system. The Tat secretion system translocates proteins showing at the N terminus a typical signal sequence containing a couple of adjacent arginine residues (7). TatB was suggested to be responsible for the association of the proteins secreted by the Tat system to the membrane (57).

In E. coli, the anti-σ factor regulating σE is a transmembrane protein and it is degraded by a membrane-located serine protease in the presence of misfolded proteins in the periplasmic space (54). In M. tuberculosis, RseA is predicted to be a soluble protein. We recently found that it has a putative Tat consensus sequence at its N terminus. The fact that rseA is in the same operon with tatB suggests that their protein products could interact and that RseA could be secreted or associated to the membrane through TatB. The presence in the same operon of the gene encoding a membrane-located serine protease (HtrA) suggests that HtrA, with its proteolytic activity, could represent the molecular switch acting (directly or indirectly) on RseA activity. The interactions among RseA, HtrA, and TatB are currently being investigated to better understand the mechanism of posttranslational regulation of σE.

σH, AN ECF σ FACTOR INVOLVED IN RESPONSE TO HEAT SHOCK AND OXIDATIVE STRESS

σH is very similar to the ECF σ factor σR of S. coelicolor. The latter responds to intracellular formation of disulfide bonds due to oxidation of cysteine thiol groups (49). σR activity is regulated at the posttranslational level by a cysteine-containing anti-σ factor (RsrA) whose gene is adjacent to sigR. In a reducing environment, RsrA binds σR, keeping it inactive; however, in oxidizing environments, disulfide bonds can form between RsrA cysteine residues and, as a consequence, σR is released in its active form from the σR-RsrA complex (48). Among the genes recognized by the σR-RNAP are sigR and the trx operon, which encodes thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase, two proteins involved in disulfide bond reduction. Usually, cells have a second pathway by which to reduce intracellular disulfide bonds, based on glutathione. Actinomycetes are an exception, as they do not synthesize glutathione but use a different compound, mycothiol, for similar functions (47). A sigR mutant of S. coelicolor produces less mycothiol than the WT parental strain, even if it is not known if this is due to the direct control of mycothiol biosynthetic genes by σR-RNAP (50).

The M. tuberculosis sigH gene is induced after heat shock, after treatment with the thiol-specific oxidizing agent diamide (42, 55), and during macrophage infection (35). Similar to sigR in S. coelicolor, the M. tuberculosis sigH gene is followed by a gene encoding an anti-σ factor whose activity is regulated by redox potential (Rodrigue et al., unpublished). The gene encoding σH was inactivated in three different laboratories (40, 42, 55). The mutants are more sensitive than the WT to high temperature and to diamide exposure. However, they are not restricted for growth in THP-1-derived macrophages and were as sensitive as the WT parental strain to the killing activity of activated murine macrophages (42). Interestingly, the sigH mutant has a very subtle phenotype in a mouse model of infection: it is able to reach the same bacterial load as the WT parent strain in mouse organs (40, 42), but there are differences in lung histopathology, including fewer granulomas and a generally decreased pulmonary inflammatory response in mice infected with the sigH mutant (40).

DNA array experiments comparing the transcriptome of the sigH mutant with that of the WT parent strain do not show any gene requiring σH for its expression during exponential growth, while 26 putative transcriptional units including 39 genes require σH for their induction after exposure to a subinhibitory concentration of diamide (42). Sixteen of the 26 putative transcriptional units were preceded by a conserved ECF σ factor-like promoter, suggesting their direct transcriptional dependence on σH, while 4 were preceded by a potential consensus sequence for an unknown regulatory protein. The genes under σH control included some encoding transcriptional regulators (σB, σE, and σH); enzymes involved in thiol metabolism, such as thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase, and a protein of unknown function with a glutaredoxin active site; and enzymes involved in cysteine and molybdopterin biosynthesis (42). Work from two other laboratories (40, 55) also derived a similar consensus sequence for genes requiring σH for their expression (Table 2).

OTHER ECF σ FACTORS

Little information is available about the other seven ECF σ factors encoded by the M. tuberculosis genome. sigD is induced following total nutrient starvation (8) and in the M. tuberculosis Rel mutant (17). The Rel protein has been well studied in E. coli and is known to be a key enzyme in the stringent response, a transition process believed to shut down active metabolism. sigJ is induced in stationary-phase cultures (38). Of particular interest is sigL. Its gene product, σL, is the closest M. tuberculosis homolog of S. coelicolor σE This protein in S. coelicolor controls cell wall structure, and its activity is posttranslationally regulated by a two-component system encoded by an operon immediately downstream of its structural gene. In M. tuberculosis, however, this gene is followed by a gene encoding a transmembrane anti-σ factor, which specifically binds to and reversibly inactivates σL (Rodrigue, unpublished data), suggesting its involvement with surface processes.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

σ factors, with their plethora of anti-σ factors and anti-anti-σ factors, are among the major and more complex players in the regulation of gene expression in bacteria. In the last few years, after the publication of the M. tuberculosis genome, the 13 σ factors of M. tuberculosis have become an important subject of investigation. Mutations in six of the σ factor genes were either made (sigB, -C, -E, -F, and -H) or identified (sigA), and a role in virulence for five of them (all except sigB) was demonstrated.

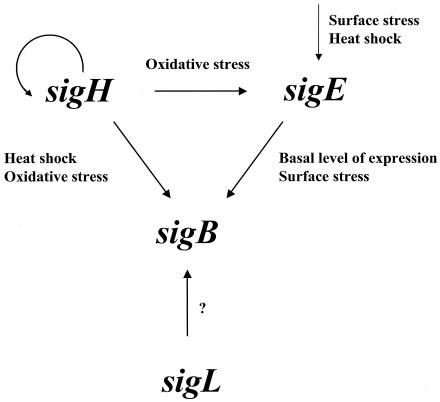

The regulons of four of these σ factors, σC, σE, σF, and σH, were characterized by DNA array technology, and this analysis showed that many genes were represented only in one regulon. However, there was some overlap, which is typical in ECF σ factor regulons. As an example of this overlap, some of the sig genes are in the regulon of other σ factors: sigE induction is σH dependent following oxidative stress but not after surface stress or heat shock (42, 55); sigB expression, however, is σE dependent under standard (unstressed) growth conditions. σE is also required for sigB induction after surface stress (43), but sigB induction after oxidative stress and heat shock is dependent on σH (42, 55) (Fig. 1). Our observations, which indicate that sigB expression is controlled by RNAPs containing different σ factors, suggest an important role for σB in M. tuberculosis physiology and perhaps virulence. Otherwise, why would this bacterium go through so much trouble to make sure that this protein is available to control transcription in different environments? However, we have not seen any diminution of pathogenicity in sigB mutants, as yet. It is possible that there is a subtle change in virulence that has been missed so far, and these studies are currently being pursued.

FIG. 1.

σ factor regulatory network. Arrows indicate the transcriptional relationships among σ factors. sigB can be transcribed by an RNAP containing σH, σE, or σL, depending on the environmental conditions. σH also promotes the transcription of its own structural gene and the induction of sigE after oxidative stress. The environmental signal activating σL is not known.

The whole question of posttranslational regulation by anti- and anti-anti-σ factors makes the matter even more complicated. The resulting picture is that of a very intricate regulatory network that will become even more complex as other σ factors and other transcriptional regulators are characterized with their regulons. We predict that the understanding of global gene regulation in M. tuberculosis will help us to understand its physiology and virulence mechanisms and will help to design new strategies to fight tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

Our work cited in this article was supported by grants from the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (Progetto Nazionale AIDS 50D.20), from the Università di Padova (Assegni di ricerca CPDR027593), from MIUR (PRIN 2001 2001053855 and PRIN 2002 2002067349) (awarded to R.M.), from the NSERC (awarded to L.G.), and from the NIH (grants AI-44856 and HL-68513) (awarded to I.S.).

We thank W. R. Bishai for sharing unpublished data and Patricia Fontan, Ryzsard Brzezinski, and Pierre-Étienne Jacques for valuable discussions. The literature survey for this article was completed in September 2003.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ades, S. E., I. L. Grigorovna, and C. A. Gross. 2003. Regulation of the alternative sigma factor σE during initiation, adaptation, and shutoff of the extracytoplasmic heat shock response in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:2512-2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akaki, T., H. Tomioka, T. Shimizu, S. Dekio, and K. Sato. 2000. Comparative roles of free fatty acids with reactive nitrogen intermediates and reactive oxygen intermediates in expression of the anti-microbial activity of macrophages against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 121:302-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Av-Gay, Y., and M. Everett. 2000. The eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 8:238-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babu, M. M. 2003. Did the loss of sigma factors initiate pseudogene accumulation in M. leprae? Trends Microbiol. 11:59-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaucher, J., S. Rodrigue, P.-E. Jacques, I. Smith, R. Brzezinski, and L. Gaudreau. 2002. Novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis anti-σ factor antagonists can control σF activity by distinct mechanisms. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1527-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentley, S. D., K. F. Chater, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, G. L. Challis, N. R. Thomson, K. D. James, D. E. Harris, M. A. Quail, H. Kieser, D. Harper, A. Bateman, S. Brown, G. Chandra, C. W. Chen, M. Collins, A. Cronin, A. Fraser, A. Goble, J. Hidalgo, T. Hornsby, S. Howarth, C. H. Huang, T. Kieser, L. Larke, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, S. O'Neil, E. Rabbinowitsch, M. A. Rajandream, K. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, D. Saunders, S. Sharp, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Taylor, T. Warren, A. Wietzorrek, J. Woodward, B. G. Barrell, J. Parkhill, and D. A. Hopwood. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berks, B. C., F. Sargent, and T. Palmer. 2000. The Tat protein export pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 35:260-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betts, J. C., P. T. Lukey, L. C. Robb, R. A. McAdam, and K. Duncan. 2002. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol. Microbiol. 43:717-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishai, W. R. 1998. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis genomic sequence: anatomy of a master adaptor. Trends Microbiol. 6:464-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boon, C., and T. Dick. 2002. Mycobacterium bovis BCG response regulator essential for hypoxic dormancy. J. Bacteriol. 184:6760-6767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brosch, R., A. S. Pym, S. V. Gordon, and S. T. Cole. 2001. The evolution of mycobacterial pathogenicity: clues from comparative genomics. Trends Microbiol. 9:452-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchmeier, N., A. Blanc-Potard, S. Ehrt, D. Piddington, L. Riley, and E. A. Groisman. 2000. A parallel intraphagosomal survival strategy shared by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1375-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, P., R. E. Ruiz, Q. Li, R. F. Silver, and W. R. Bishai. 2000. Construction and characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking the alternate sigma factor gene, sigF. Infect. Immun. 68:5575-5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagles, A. Krogh, J. McLean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, J. Osborne, M. A. Quail, M.-A. Rajandream, J. Rogers, S. Rutter, K. Seegar, J. Skelton, R. Squares, J. E. Sulston, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrel. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cole, S. T., K. Eiglmeier, J. Parkhill, K. D. James, N R. Thomson, P. R. Wheeler, N. Honore, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, K. Mungall, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. M. Davies, K. Devlin, S. Duthoy, T. Feltwell, A Fraser, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, C. Lacroix, J. Maclean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, K. M. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, S. Simon, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Stevens, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, J. R. Woodward, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409:1007-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins, D. M., R. P. Kawakami, G. W. de Lisle, L. Pascopella, B. R. Bloom, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1995. Mutation of the principal sigma factor causes loss of virulence in a strain of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:8036-8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahl, J. L., C. N. Kraus, H. I. M. Boshoff, B. Doan, K. Foley, D. Avarbock, G. Kaplan, V. Mizrahi, H. Rubin, and C. E Barry III. 2003. The role of RelMtb-mediated adaptation to stationary phase in long-term persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:10026-10031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasgupta, N., V. Kapur, K. K. Singh, T. K. Das, S. Sachdeva, K. Jyothisri, and J. S. Tyagi. 2000. Characterization of a two-component system, devR-devS, of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber. Lung Dis. 80:141-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeMaio, J., Y. Zhang, C. Ko, and W. R. Bishai. 1997. Mycobacterium tuberculosis sigF is part of a gene cluster with similarity with the Bacillus subtilis sigF and sigB operons. Tuber. Lung Dis. 78:3-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeMaio, J., Y. Zhang, C. Ko, D. B. Young, and W. R. Bishai. 1996. A stationary-phase stress-response sigma factor from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2790-2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deretic, V., and R. A. Fratti. 1999. Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1603-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dieli, F., M. Troye-Blomberg, J. Ivanyi, J. J. Fournié, A. M. Krensky, M. Bonneville, M. A. Peyrat, N. Caccamo, G. Sireci, and A. Salerno. 2001. Granulysin-dependent killing of intracellular and extracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis by Vγ9/Vδ2 T lymphocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1082-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doukhan, L., M. Predich, G. Nair, O. Dussurget, I. Mandic-Mulec, S. T. Cole, D. R. Smith, and I. Smith. 1995. Genomic organization of the mycobacterial sigma gene cluster. Gene 165:67-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dove, S. L., S. A. Darst, and A. Hochschild. 2003. Region 4 of σ as a target for transcriptional regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 48:863-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubnau, E., P. Fontan, R. Manganelli, S. Soares-Appel, and I. Smith. 2002. Mycobacterium tuberculosis genes induced during infection of human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 70:2787-2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dubnau, E., and I. Smith. 2003. Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene expression in macrophages. Microb. Infect. 5:629-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dye, C., S. Scheele, P. Dolin, V. Pathania, and M. Raviglione. 1999. Global burden of tuberculosis. JAMA 282:677-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ewann, F., M. Jackson, K. Pethe, A. Cooper, N. Mielcarek, D. Ensergueix, B. Gicquel, C. Locht, and P. Supply. 2002. Transient requirement of the PrrA-PrrB two-component system for early intracellular multiplication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 70:2256-2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleischmann, R. D., D. Alland, J. A. Eisen, L. Carpenter, O. White, J. Peterson, R. DeBoy, R. Dodson, M. Gwinn, D. Haft, E. Hickey, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, L. A. Umayam, M. Ermolaeva, S. L. Salzberg, A. Delcher, T., Utterback, J. Weidman, H. Khouri, J. Gill, A. Mikula, W. Bishai, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Whole-genome comparison of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical and laboratory strains. J. Bacteriol. 184:5479-5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser, C. M., S. Casjens, W. M. Huang, G. G. Sutton, R. Clayton, R. Lathigra, O. White, K. A. Ketchum, R. Dodson, E. K. Hickey, M. Gwinn, B. Dougherty, J. F. Tomb, R. D. Fleischmann, D. Richardson, J. Peterson, A. R. Kerlavage, J. Quackenbush, S. Salzberg, M. Hanson, R. van Vugt, N. Palmer, M. D. Adams, J. Gocayne, J. C. Venter, et al. 1995. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science 270:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gold, B., G. M. Rodriguez, S. A. Marras, M. Pentecost, and I. Smith. 2001. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis IdeR is a dual functional regulator that controls transcription of genes involved in iron acquisition, iron storage and survival in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 42:851-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gomez, J. E., J. M. Chen, and W. R. Bishai. 1997. Sigma factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber. Lung Dis. 78:175-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomez, M., G. Nair, L. Doukhan, and I. Smith. 1998. sigA is an essential gene in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 29:617-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez, M., and I. Smith. 2000. Determinants of mycobacterial gene expression, p. 111-129. In H. F. Hatfull and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. (ed.), Molecular genetics of mycobacteria. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 35.Graham, J. E., and J. E. Clark-Curtiss. 1999. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNAs synthesized in response to phagocytosis by human macrophages by selective capture of transcribed sequences (SCOTS). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11554-11559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grange, J. M., and A. Zumia. 1999. Paradox of the global emergency of tuberculosis. Lancet 353:996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Himmelreich, R., H. Hilbert, H. Plagens, E. Pirkl, B. C. Li, and R. Herrmann. 1996. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:701-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu, Y., and A. R. M. Coates. 2001. Increased levels of sigJ mRNA in late stationary phase cultures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis detected by DNA array hybridisation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 202:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes, K. T., and K. Mathee. 1998. The anti-sigma factors. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:231-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaushal, D., B. J. Schroeder, S. Tyagi, T. Yoshimatsu, C. Scott, C. Ko, L. Carpenter, J. Mehrotra, Y. C. Manabe, R. D. Fleischmann, and W. R. Bishai. 2002. Reduced immunopathology and mortality despite tissue persistence in a Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking alternative σ factor, SigH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:8330-8335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manganelli, R., E. Dubnau, S. Tyagi, F. R. Kramer, and I. Smith. 1999. Differential expression of 10 sigma factor genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 31:715-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manganelli, R., M. I. Voskuil, G. K. Schoolnik, E. Dubnau, M. Gomez, and I. Smith. 2002. Role of the extracytoplasmic-function σ factor σH in Mycobacterium tuberculosis global gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 45:365-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manganelli, R., M. I. Voskuil, G. K. Schoolnik, and I. Smith. 2001. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis ECF sigma factor σE: role in global gene expression and survival in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 41:423-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michele, T. M., C. Ko, and W. R. Bishai. 1999. Exposure to antibiotics induces expression of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis sigF gene: implications for chemotherapy against mycobacterial persistors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:218-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Missiakas, D., and S. Raina. 1998. The extracytoplasmic function sigma factors: role and regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1059-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mulder, N. J., R. E. Powels, H. Zappe, and L. M. Steyn. 1999. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis mysB gene product is a functional equivalent of the Escherichia coli sigma factor, KatF. Gene 240:361-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newton, G. L., K. Arnold, M. S. Price, C. Sherril, S. B. Delcardayre, Y. Aharonowitz, G. Cohen, J. Davies, R. C. Fahey, and C. Davis. 1996. Distribution of thiols in microorganisms: mycothiol is a major thiol in most actinomycetes. J. Bacteriol. 178:1990-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paget, M. S. B., J.-B. Bae, M.-Y. Hahn, W. Li, C. Kleanthous, J.-H. Roe, and M. J. Buttner. 2001. Mutational analysis of RsrA, a zinc-binding anti-sigma factor with a thiol-disulphide redox switch. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1036-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paget, M. S. B., J.-G. Kang, J.-H. Roe, and M. J. Buttner. 1998. σR, an RNA polymerase sigma factor that modulates expression of the thioredoxin system in response to oxidative stress in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). EMBO J. 19:5776-5782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paget, M. S. B., V. Molle, G. Cohen, Y. Aharonowitz, and M. J. Buttner. 2001. Defining the disulphide stress response in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): identification of the σR regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1007-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park, H.-D., K. M. Guinn, M. I. Harrel, R. Liao, M. I. Voskuil, M. Tompa, G. K. Schoolnik, and D. R. Sherman. 2003. Rv3133c/dosR is a transcription factor that mediates the hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 48:833-843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pérez, E., S. Samper, Y. Bordas, C. Guilhot, B. Gicquel, and C. Martín. 2001. An essential role for phoP in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 41:179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Predich, M., L. Doukhan, G. Nair, and I. Smith. 1995. Characterization of RNA polymerase and two sigma-factors genes from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 15:355-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raivio, T. L., and T. J. Silhavy. 2001. Periplasmic stress and ECF sigma factors. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:591-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raman, S., T. Song, X. Puyang, S. Bardarov, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., and R. N. Husson. 2001. The alternative sigma factor SigH regulates major components of oxidative and heat stress response in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 183:6119-6125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodriguez, G. M., and I. Smith. 2003. Mechanism of iron regulation in mycobacteria: role in physiology and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1485-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sargent, F., R. G. Bogsch, N. R. Stanley, M. Wexler, C. Robinson, B. C. Berks, and T. Palmer. 1998. Overlapping functions of components of a bacterial Sec-independent protein export pathway. EMBO J. 17:3640-3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schnappinger, D., S. Erth, M. I. Voskuil, Y. Liu, J. A. Mangan, I. M. Monahan, G. Dolganov, B. Efron, P. D. Butcher, C. Nathan, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2003. Transcriptional adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within macrophages: insights into the phagosomal environment. J. Exp. Med. 198:693-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sherman, D. R., M. I. Voskuil, D. Schnappinger, R. Liao, M. I. Harrell, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2001. Regulation of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis hypoxic response gene encoding α-crystallin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7534-7539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shires, K., and L. Steyn. 2001. The cold-shock stress response in Mycobacterium smegmatis induces the expression of a histone-like protein. Mol. Microbiol. 39:994-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith, I. 2003. Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis and molecular determinants of virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 16:463-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Soliveri, J. A., J. Gomez, W. R. Bishai, and K. F. Chater. 2000. Multiple paralogous genes related to the Streptomyces coelicolor developmental regulatory gene whiB are present in Streptomyces and other actinomycetes. Microbiology 146:333-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stewart, G. R., L. Wernisch, R. Stabler, J. A. Mangan, K. J. Hinds, D. B. Young, and P. D. Butcher. 2002. Dissection of heat-shock response in Mycobacterium tuberculosis using mutants and microarrays. Microbiology 148:3129-3138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steyn, A. J. C., D. M. Collins, M. K. Hondalus, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., R. P. Kawakami, and B. R. Bloom. 2002. Mycobacterium tuberculosis WhiB3 interacts with RpoV to affect host survival but is dispensable for in vivo growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3147-3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tanaka, K., Y. Takayanagi, N. Fujita, A. Ishihama, and H. Takahashi. 1993. Heterogeneity of the principal σ factors in Escherichia coli: the rpoS gene product, σ38, is a second principal σ factor of RNA polymerase in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:3511-3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Unniraman, S., M. Chatterji, and V. Nagaraja. 2002. DNA gyrase genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a single operon driven by multiple promoters. J. Bacteriol. 184:5449-5456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Voskuil, M. I., D. Schnappinger, K. C. Visconti, M. I. Harrel, G. M. Dolganov, D. R. Sherman, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2003. Inhibition of respiration by nitric oxide induces a Mycobacterium tuberculosis dormancy program. J. Exp. Med. 198:705-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wayne, L. G., and C. Sohaskey. 2001. Nonreplicating persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:139-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilson, M., J. DeRisi, H.-H. Kristensen, P. Imboden, S. Rane, P. O. Brown, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1999. Exploring drug-induced alteration in gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by microarray hybridization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12833-12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wösten, M. M. S. M. 1998. Eubacterial sigma-factors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:127-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zahrt, T. C. 2003. Molecular mechanisms regulating persistent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Microb. Infect. 5:159-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zahrt, T. C., and V. Deretic. 2001. Mycobacterium tuberculosis signal transduction system required for persistent infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:12706-12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]