Abstract

Objective

To synthesize findings from recent studies of strategies to deliver insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) at scale in malaria-endemic areas.

Methods

Databases were searched for studies published between January 2000 and December 2010 in which: subjects resided in areas with endemicity for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria; ITN delivery at scale was evaluated; ITN ownership among households, receipt by pregnant women and/or use among children aged < 5 years was evaluated; and the study design was an individual or cluster-randomized controlled design, nonrandomized, quasi-experimental, before-and-after, interrupted time series or cross-sectional without temporal or geographical controls. Papers describing qualitative studies, case studies, process evaluations and cost-effectiveness studies linked to an eligible paper were also included. Study quality was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias checklist and GRADE criteria. Important influences on scaling up were identified and assessed across delivery strategies.

Findings

A total of 32 papers describing 20 African studies were reviewed. Many delivery strategies involved health sectors and retail outlets (partial subsidy), antenatal care clinics (full subsidy) and campaigns (full subsidy). Strategies achieving high ownership among households and use among children < 5 delivered ITNs free through campaigns. Costs were largely comparable across strategies; ITNs were the main cost. Cost-effectiveness estimates were most sensitive to the assumed net lifespan and leakage. Common barriers to delivery included cost, stock-outs and poor logistics. Common facilitators were staff training and supervision, cooperation across departments or ministries and stakeholder involvement.

Conclusion

There is a broad taxonomy of strategies for delivering ITNs at scale.

Résumé

Objectif

Réaliser une synthèse des études récentes menées sur les stratégies permettant de fournir des moustiquaires imprégnées d’insecticide (MMI) à grande échelle dans les zones où le paludisme est endémique.

Méthodes

À partir de bases de données, on a recherché les études publiées entre janvier 2000 et décembre 2010, dans lesquelles: les sujets résidaient dans des zones où le paludisme à Plasmodium falciparum et à Plasmodium vivax était endémique; une distribution à grande échelle de MMI a été évaluée; la détention de MMI dans les foyers, la réception par les femmes enceintes et/ou l’utilisation chez les enfants âgés de moins de 5 ans a été évaluée; la conception de l’étude impliquait un contrôle individuel ou en grappes, était quasi expérimentale, avant et après, en séries temporelles interrompues, ou transversale sans contrôle temporel ou géographique. Les documents de travail décrivant les études qualitatives, les études de cas et les études d’évaluation des processus et de rentabilité, associés à un document de travail éligible, ont également été inclus. La qualité des études a été appréciée à l'aide de la liste de vérification des risques Cochrane et des critères de l'approche GRADE. On a relevé et évalué d’importantes influences sur l’augmentation de la distribution dans les différentes stratégies.

Résultats

Un total de 32 documents de travail décrivant 20 études africaines a été étudié. Bon nombre des stratégies de distribution impliquaient différents secteurs de la santé, ainsi que le réseau du commerce de détail (partiellement subventionné), les maternités (intégralement subventionnées) et les campagnes (intégralement subventionnées). Les stratégies qui ont obtenu une meilleure détention dans les foyers et une plus grande utilisation chez les enfants âgés de moins de 5 ans étaient les campagnes de distribution gratuite des MMI. Les coûts étaient largement comparables dans les stratégies étudiées, les MMI constituant le principal coût. Les estimations de rentabilité variaient surtout en fonction de la durée de vie et de la résistance présumée de la moustiquaire. Parmi les inconvénients les plus courants figuraient le coût, la rupture de stock et une mauvaise logistique. Les facteurs favorables les plus courants étaient la formation et la supervision du personnel, la coopération interdépartementale ou interministérielle, ainsi que l’implication des intervenants.

Conclusion

Il existe une vaste taxonomie de stratégies pour une distribution à grande échelle des MMI.

Resumen

Objetivo

Sintetizar los resultados de estudios recientes acerca de las estrategias para distribuir a escala mosquiteros tratados con insecticida (RTI) en zonas con malaria endémica.

Métodos

Se examinaron bases de datos en busca de estudios publicados entre enero de 2000 y diciembre de 2010 en los que: los sujetos residían en áreas en las que la malaria por Plasmodium falciparum y Plasmodium vivax es endémica; se evaluó la entrega de RTI a escala; se evaluó la propiedad de RTI en hogares, la recepción por parte de mujeres embarazadas y/o el uso por parte de niños menores de 5 años; y cuyo diseño del estudio era un estudio controlado individual o aleatorio sobre grupos, no aleatorio, cuasiexperimental, antes y después, de series de tiempo interrumpido o transversal sin controles temporales o geográficos. También se incluyeron artículos que describían estudios cualitativos, estudios de caso, evaluaciones de proceso y estudios de efectividad de costes vinculados a un artículo que cumplía con las condiciones. La calidad del estudio fue evaluada por medio de la herramienta Cochrane de riesgo de sesgo y los criterios GRADE. Se identificaron y evaluaron importantes influencias sobre el aumento progresivo en las estrategias de distribución.

Resultados

Se revisaron un total de 32 artículos que describían 20 estudios africanos. En muchas de las estrategias de distribución participaron sectores sanitarios y establecimientos de venta al por menor (subsidio parcial), clínicas de atención prenatal (subsidio completo) y campañas (subsidio completo). Las estrategias que consiguieron un grado de participación entre los hogares y un uso entre niños menores de 5 años elevados distribuyeron RTI de forma gratuita mediante campañas. Los costes de las diversas estrategias fueron en gran medida comparables; las RTI supusieron el coste principal. Los cálculos de efectividad de costes fueron sensibles sobre todo a la vida útil esperada del mosquitero y a las fugas. Entre las barreras frecuentes a la distribución figuraron el coste, la falta de existencias y una logística deficiente. Los facilitadores comunes fueron la formación y supervisión del personal, la cooperación entre departamentos o ministerios y la implicación de las partes implicadas.

Conclusión

Hay una amplia taxonomía de estrategias para distribuir RTI a escala.

ملخص

الغرض

استخلاص النتائج من الدراسات الحديثة للاستراتيجيات الرامية إلى إيتاء الناموسيات المعالجة بمبيدات الحشرات على نطاق واسع في المناطق التي تتوطنها الملاريا.

الطريقة

تم البحث في قواعد البيانات عن الدراسات المنشورة بين كانون الثاني/يناير 2000 وكانون الأول/ديسمبر 2010 التي تضمنت: الأشخاص المقيمين في مناطق تتوطنها ملاريا المتصورة المنجلية والمتصورة النشيطة؛ وتم تقييم إيتاء الناموسيات المعالجة بمبيدات الحشرات على نطاق واسع؛ ومعدل امتلاك الناموسيات المعالجة بمبيدات الحشرات بين الأسر، وتم تقييم تسلم السيدات الحوامل لها و/أو استخدامها بين الأطفال الذين تقل أعمارهم عن 5 سنوات؛ وكان تصميم الدراسة خاضعاً للمراقبة على نحو فردي أو عشوائي عنقودي أو غير عشوائي أو شبه تجريبي أو قبلي وبعدي أو سلاسل زمنية متقطعة أو متعددة القطاعات دون ضوابط زمنية أو جغرافية. وتم كذلك إدراج الأوراق التي تصف الدراسات النوعية ودراسات الحالة وتقييمات العملية ودراسات المردودية المرتبطة بورقة مؤهلة. وتم تقييم نوعية الدراسة باستخدام منهجية مخاطر كوكرين المعنية بالقائمة المرجعية للتحيز ومعايير GRADE. وتم تحديد التأثيرات الهامة على التعزيز وتقييمها عبر استراتيجيات الإيتاء.

النتائج

تم استعراض ما إجماليه 32 ورقة تصف 20 دراسة أفريقية. وتضمنت العديد من استراتيجيات الإيتاء قطاعات الصحة ومنافذ البيع بالتجزئة (الإعانة الجزئية) وعيادات الرعاية السابقة للولادة (الإعانة الكلية) والحملات (الإعانة الكلية). وأدت الاستراتيجيات التي تحقق معدل امتلاك مرتفع بين الأسر والاستخدام بين الأطفال الذين تقل أعمارهم عن 5 سنوات إلى إيتاء الناموسيات المعالجة بمبيدات الحشرات بالمجان عن طريق الحملات. وكانت التكاليف قابلة للمقارنة على نطاق واسع عبر الاستراتيجيات؛ وكانت الناموسيات المعالجة بمبيدات الحشرات هي التكلفة الرئيسية. وكانت تقديرات المردودية أكثر حساسية للعمر والتسرب المفترضين للناموسيات. وتضمنت الحواجز الشائعة أمام الإيتاء التكلفة ونفاد المخزون وضعف اللوجيستيات. وتمثلت أوجه التيسير الشائعة في تدريب العاملين والإشراف عليهم والتعاون عبر الإدارات أو الوزارات وإشراك أصحاب المصلحة.

الاستنتاج

ثمة تصنيف واسع للاستراتيجيات المعنية بإيتاء الناموسيات المعالجة بمبيدات الحشرات على نطاق واسع.

摘要

目的

综合在疟疾流行地区大规模发放驱虫蚊帐(ITN)战略的新近研究结果。

方法

在数据库中对在2000 年1 月至2010 年12 月发表的研究报告进行检索,入选条件:研究对象居住在恶性疟原虫和间日疟原虫疟疾流行地区;评估了大规模发放ITN;评估了家庭中ITN的所有权、由孕妇接收和/或在年龄<5 岁的儿童中使用的情况;研究设计采用单病例或群组随机对照,非随机、准实验、前后设计、间歇时间序列设计或无时间或地区对照的横断设计。描述入选论文相关的定性研究、个案研究、措施评价和成本效益研究的论文也纳入分析。使用Cochrane偏倚风险表和GRADE标准评估研究的质量。识别并评估在发放策略中对扩大干预的重要影响。

结果

总共纳入了涉及20 项非洲研究的32 篇论文。许多发放策略涉及卫生部门和零售网点(部分补贴)、产前保健诊所(全额补贴)和活动(全额补贴)。通过宣传免费发放ITN的策略实现了在家庭中的高所有权和在年龄<5 岁的儿童中的高利用率。各种策略的成本大体相同;ITN 是主要成本。成本效益估计对假设的净使用寿命和破损最为敏感。发放的常见障碍包括成本、缺货和不完善的物流。共同的促进因素是工作人员培训和监督、跨部门或部委合作和利益相关者的参与。

结论

大规模发放ITN具有多种策略。

Резюме

Цель

Обобщить результаты последних исследований стратегий масштабной поставки сеток, обработанных инсектицидом (ITN), в районах, для которых малярия является эндемическим заболеванием.

Методы

В базах данных производился поиск исследований, опубликованных с января 2000 г. по декабрь 2010 г., в которых: субъекты проживали в районах, для которых малярия, вызванная Plasmodium falciparum и Plasmodium vivax, является эндемическим заболеванием; оценивалась масштабная поставка ITN; оценивались использование ITN домашними хозяйствами и применение для защиты беременных женщин и/или детей в возрасте до 5 лет; при этом применялся план индивидуального или кластер-рандомизированного контролируемого исследования, нерандомизированного, квази-экспериментального, «до и после», прерванного временного ряда или перекрестного без временного или географического контроля. Также включались статьи, описывающие качественные исследования, ситуационные исследования, оценки процессов и исследования эффективности затрат, связанные с рассматриваемой работой. Качество исследований оценивалось с помощью Кокрановского контрольного списка для оценки риска систематической ошибки и критериев GRADE. Для стратегий поставки были выявлены и оценены факторы, оказывающие существенное влияние на увеличение масштаба.

Результаты

Всего рассмотрено 32 работы с описанием 20 исследований, проведенных в Африке. Во многих стратегиях поставки участвовали секторы здравоохранения и точки розничной торговли (частичное субсидирование), клиники дородовой помощи (полное субсидирование), а также практиковалось проведение кампаний (полное субсидирование). Наибольшее использование ITN в домашних хозяйствах и для защиты детей в возрасте до 5 лет достигалось с применением в ходе кампаний стратегий бесплатного распространения. Затраты при различных стратегиях были в значительной степени соизмеримы; основную часть затрат составляла стоимость ITN. Оценки эффективности затрат были наиболее чувствительны к предполагаемому сроку службы сеток и степени пропускания насекомых. Среди наиболее распространенных факторов, препятствующих поставке, были стоимость, дефицит и плохая логистика. Среди способствующих поставке факторов были обучение персонала и надзор за его деятельностью, сотрудничество между министерствами и ведомствами, а также вовлечение заинтересованных сторон.

Вывод

Имеется широкая систематика стратегий масштабных поставок ITN.

Introduction

Malaria continues to represent a major public health problem in areas of endemicity, with an estimated 225 million cases worldwide in 2009.1 The 2015 goals of the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Roll Back Malaria Partnership are to reduce global malaria cases by 75% from 2000 levels and to reduce malaria deaths to near zero through universal coverage by effective prevention and treatment interventions.1 Among other preventive interventions, WHO recommends the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), particularly long-lasting insecticidal nets, which have been shown to be cost-effective,2–4 to reduce malaria episodes among children < 5 years of age (hereafter, “children under 5”) by approximately 50% and all-cause mortality by 17%.5,6 Universal coverage with ITNs is defined as use by > 80% of individuals in populations at risk.6 WHO recommends supplying ITNs without charge or with a high subsidy and using a combination of periodic mass campaigns and routine delivery channels to deliver ITNs at scale.6 Other strategies include supporting the existing commercial sector and distributing vouchers exchangeable for partially subsidized ITNs through retailers.7

In response to the Roll Back Malaria Partnership’s targets for universal coverage, considerable efforts have been made recently to scale up ITN delivery. However, there is still low coverage in many countries and a need to understand the lessons learnt from experiences of scaling up ITN delivery. We therefore conducted a systematic review to synthesize recent evidence on the delivery of ITNs (including long-lasting insecticidal nets) at scale in malaria-endemic areas by documenting and characterizing the strategies for delivering ITNs at scale (at the district level or higher); summarizing ITN ownership among households and ITN use among children under 5, stratified by measures of equity when possible; summarizing the reported cost or cost-effectiveness of different strategies; and synthesizing information on reported factors influencing delivery of ITNs at scale.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted to identify studies that reported on the delivery of ITNs (including long-lasting insecticidal nets) at scale. The findings reported here form part of a larger systematic review on the scale-up of WHO-recommended malaria control interventions.8 We used a definition of “scaling up” that characterized this activity as the expansion of a health intervention beyond the initial geographical area or population group covered.9,10 We considered “at scale” to be ITN delivery in at least one district or the equivalent lowest level of health service administration in a given country.

Search strategy

Medline (Ovid), EMBASE, CAB Abstracts, Global Health and Africa Wide databases were searched using subject heading classification terms and free-text words. The following categories were combined using the AND Boolean logic operator: malaria terms, ITN and long-lasting insecticidal net terms and scaling-up terms (Box 1, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/9/11-094771). Filters were used to limit the search to humans and to publication dates from January 2000 to December 2010. Relevant papers from the grey literature were identified by searching Eldis and WHOLIS databases and Roll Back Malaria, Malaria Consortium, Africa Malaria Network Trust, and The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria web sites. Citation data for identified papers were exported to EndNote (Thomson Reuters, Carlsbad, USA), where duplicates were removed.

Box 1. Ovid Medline search.

1. (malaria* or severe malaria or plasmodium or Plasmodium falciparum or Plasmodium vivax).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

2. Malaria/ or exp Malaria, Falciparum/ or Malaria, Cerebral/ or Malaria, Vivax/

3. Plasmodium ovale/ or Plasmodium falciparum/ or Plasmodium/ or Plasmodium malariae/ or Plasmodium vivax/

4. exp Anopheles/

5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

6. Mosquito Control/

7. Insect Vectors/

8. “Bedding and Linens”/

9. Mosquito Nets/

10. Insecticide-Treated Bednets/

11. exp Insecticides/

12. exp Pyrethrins/

13. DDT/

14. Housing/

15. Larva/

16. exp Anopheles/

17. exp Chemoprevention/

18. Sulfadoxine/

19. Pyrimethamine/

20. pregnancy complications, infectious/ or pregnancy complications, parasitic/

21. Infant/

22. exp Anti-malarials/

23. Diagnosis/

24. exp Microscopy/

25. exp Laboratories/

26. Diagnostic Tests, Routine/

27. Point-of-Care Systems/

28. exp Therapeutics/

29. exp Drug Therapy/

30. Artemisinins/

31. Amodiaquine/

32. Mefloquine/

33. exp Chloroquine/

34. Primaquine/

35. Insect Repellents/

36. Community Health Aides/

37. 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36

38. (LLIN* or long-last* net or (long-lasting adj5 net)).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

39. (ITN* or insecticide-treat* net or insecticidal-treat* net or insecticide-net or insecticidal-net or bed-net or bednet or treated-net or mosquito-net).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

40. (IRS or indoor-residual spray* or indoor-spray*).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

41. (larvicid* or larval control or larvi* fish or environment* management or environment* control* or drain* or house-screen* or (mosquito-proof* adj5 house) or repellent* or insecticide-treat* veil or insecticide-treat* hammock or insecticide-treat* blanket or insecticide-treat* cloth*).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

42. (IPT or IPTp or IPTi or IPTc or intermittent preventive treatment*).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

43. (diagnosis or RDT* or rapid diagnos* test* or rapid test* or microscop* or laborator*).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

44. (treatment or antimalaria* or artemisinin-combination treat* or artemisinin-combination therap* or artemether lumefantrine or artesunate or amodiaquine or mefloquine or chloroquine or primaquine).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

45. (malaria control or malaria intervention* or vector control* or vector management).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

46. (community health worker* or village health worker* or (home manag* adj5 malaria)).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

47. 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46

48. 37 or 47

49. (scale-up or scaling-up or at-scale or go* to-scale or large-scale or roll-out or universal coverage).ot,tw,ab,fs,kw,ti,hw,nm.

50. 5 and 48 and 49

51. limit 50 to (humans and yr = ”2000 -Current”)

Text word search fields: ot, original title; tw, title word; ab, abstract; fs, floating subheading; kw, key word; ti, title; hw, heading word; nm, name of substance word; * = truncation; exp, explode subject heading term.

Eligibility criteria

Screening was a two-stage process. First, two authors (BW and LSP) independently screened titles and abstracts to determine which papers should undergo full-text assessment for eligibility. Retained papers underwent full-text review (performed independently by BW and LSP) to determine whether they described studies that satisfied the following criteria: subjects resided in areas where Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax are endemic; ITN delivery at scale was evaluated; ITN ownership among households, receipt by pregnant women and/or use among children under 5 was evaluated; and an individual or cluster-randomized controlled design, a nonrandomized design, a quasi-experimental design, a before-and-after design, an interrupted time series design or a cross-sectional design without temporal or geographical controls was used.11–13 Papers meeting these criteria were termed “index papers”. In addition to documenting and characterizing the strategies for delivering ITNs at scale and summarizing ITN ownership among households and ITN use among children under 5, this review also aimed to summarize the reported cost or cost-effectiveness of different strategies and to synthesize information on reported factors influencing delivery of ITNs at scale. As such, we also included papers that described qualitative studies, case studies, process evaluations and cost-effectiveness studies that were linked to an index paper.

The reference lists from eligible papers were hand-searched for additional relevant citations. All data relevant to the review were extracted from final included papers into an Access database (Microsoft, Redmond, United States of America).

Analysis

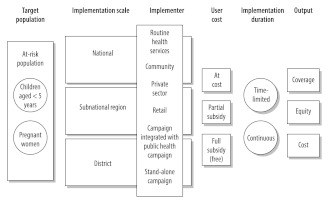

The first objective was to document and characterize the strategies for delivering ITNs at scale and was guided by a framework adapted from Kilian et al.14 Strategies were characterized by target population, implementation scale, implementer type, user cost and implementation duration (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of strategies for delivering insecticide-treated nets at scale

Source: Adapted from Kilian et al.14

The effectiveness of ITN delivery strategies was not compared using meta-analysis because study designs were too variable.15 Rather, narrative synthesis with a Best Evidence Synthesis approach was used to summarize findings and compare results across the different delivery strategies.16,17

The extent to which ITN ownership or use changed over time and whether such changes were attributable to the delivery strategy were assessed according to study quality. The quality of studies with a randomized or nonrandomized control group and of those using an interrupted time-series design was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias checklist15 and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria.18

All reported costs were adjusted for inflation by two authors (LSP and LM) and are presented as 2010 United States dollars (US$) using the consumer price indices available from the International Monetary Fund.19 When possible, costs are reported separately as financial (i.e. monetary) costs or economic costs (including opportunity costs and costs of donated goods and services).

Content analysis and narrative synthesis were used to identify important influences on delivering ITNs at scale and themes were assessed across the different ITN delivery strategies.16,17

Results

Fig. 2 details the literature search and screening process, performed according to guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Group.20 We included 32 papers that described 20 studies from 12 African nations (Burkina Faso, Eritrea, Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Niger, Nigeria, Togo, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania and Zambia) and one partially autonomous region (Zanzibar). Six studies were implemented on a national level, two on a regional scale and 12 at the district level (of which three took place in only one district). Fourteen studies delivered ITNs only to children under 5 and/or pregnant women (Table 1 and Table 2, both available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/9/11-094771).

Fig. 2.

Flow of selection process for inclusion of studies of strategies for scaling up delivery of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) for malaria control in areas with endemicity for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria

ACT, artemisinin combination treatment; IPTp, intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women; IVC, integrated vector control; LLIN, long-lasting insecticidal net.

Table 1. Characteristics of strategies to deliver insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) at scale in areas with endemicity for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malariaa.

| Implementation duration and implementer | User cost |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full subsidy (free) | Partial subsidy | At cost | |

| Continuous | |||

| Routine health services | |||

| Health facility | ITN to GP in 5 districts (Chipata, Lundazi, Chama, Chadiza, Petauka) of Zambia21 | ||

| Antenatal care and/or maternal and child health clinic | LLIN to PW in 1 district (Kossi) of Burkina Faso22–24 ITN to PW nationally in Eritrea25 ITN to PW in 35 districts of Kenya26 LLIN to PW and children < 5 in 2 districts (Adjumani and Jinja) of Uganda27 |

ITN to PW and children < 5 nationally in Kenya28 ITN or voucher to PW in 1 district (Lawra) of Ghana29,30 Voucher for ITN to PW in 1 region (Volta) of Ghanab,31 Voucher for ITN to PW and children < 5 nationally in the United Republic of Tanzaniab,32–35 Voucher for ITN to PW in 2 districts (Kilombero and Ulanga) in the United Republic of Tanzaniab,36–38 ITN to PW and children < 5 nationally in Malawi3,39,40 |

|

| Retail | ITN (via voucher) to PW in 1 district (Lawra) of Ghana29,30 ITN (via voucher) to PW in 1 region (Volta) of Ghana31 ITN (via voucher) to PW and children < 5 nationally in the United Republic of Tanzania32–35 |

||

| LLIN to GP in 1 district (Kossi) of Burkina Faso22–24 ITN to GP nationally in Kenya28 ITN to GP in 2 districts (Kilombero and Ulanga) of the United Republic of Tanzania36–38 |

|||

|

Community |

ITN to GP nationally in Eritrea after 200325

|

ITN to GP nationally in Malawi after 20033,39,40 ITN to GP in 5 districts (Chipata, Lundazi, Chama, Chadiza, Petauka) of Zambia21 |

ITN to GP nationally in Eritrea before 200325 |

| Time-limited | |||

| Stand-alone campaign | LLIN to children < 5 in 2 districts (Micheweni and North A) in Zanzibar41

LLIN to PW and children < 5 in 2 districts (Adjumani and Jinja) of Uganda27 |

||

| Campaign integrated with public health campaign | |||

| Measles vaccination | ITN/LLIN to children < 5 in 1 district (Lawra) of Ghana29,30 LLIN to children < 5 in 4 districts (Kwale, Bondo, Greater Kisii, Makueni) of Kenya42,43 LLIN to children < 5 in 59 districts of Madagascar44 ITN to children < 5 in region (Lindi) of the United Republic of Tanzania45 ITN to children < 5 in 1 district (Rifiji) of the United Republic of Tanzania46 LLIN to children < 5 nationally in Togo47,48 LLIN to children < 5 in 4 rural districts (Chilubi, Kaputa, Mambwe, Nyimba) of Zambia49 Voucher for ITN to children < 5 in 1 urban district (Kalalushi) of Zambia49 |

||

| Polio vaccination | LLIN to children < 5 nationally in Niger50 | ||

| MDA for lymphatic filariasis | ITN to PW and children < 5 in 2 districts (Kanke, Akwanga) of Nigeria51 | ||

GP, general population; LLIN, long-lasting insecticidal nets; MDA, mass drug administration; PW, pregnant women.

a Studies may appear in more than one category if multiple strategies were used to deliver ITNs at scale or if strategies changed over time.

b Used voucher-based distribution of partially subsidised ITNs, in which vouchers were distributed in antenatal care clinics and exchanged for a partially subsidised ITN in retail outlets.

Table 2. Summary of 20 studies on the delivery of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) at scale in areas with endemicity for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, by delivery strategya.

| Delivery strategy | Country, scale | Evaluation method | Outcome | Equity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Outcomeb | ||||

| Continuous | |||||

| Full subsidy; routine health services (ANC clinic) and/or community-based | |||||

| ANC clinics to PW (free) and retail to GP (partial subsidy), implemented 2006 in 24 health centre catchment areas | Burkina Faso, 1 district (Kossi)22–24 | cRCT of SM versus SM and ANC distribution via HH surveys in 2007 (1049 HH) | Comparison area: HH LLIN ownership, 23%; social marketing only Intervention area: HH LLIN ownership, 35%; SM and ANC; P < 0.001 |

Not reported | Not reported |

| From 2001, ANC clinics to PW (free) and HF and CHW to GP (full cost; free after 2003) | Eritrea, national25 | 2004 NMCP survey in 4 of 6 regions; uncontrolled cross-sectional studyc | HH ITN ownership, 62%; ITN use among children < 5, 59% | Not reported | Not reported |

| ANC clinics to PW (free in Adjumani only) and stand-alone net campaign to children < 5 (free in both districts) in 2007 | Uganda, 2 districts (Adjumani, Jinja)27 | HH survey in 2007 (378 HH in the ANC study); no controld | ITN use among children < 5, 94% (ANC study: Adjumani) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Partial subsidy; routine health services (HFs; ANC and/or MCH clinics) and/or retailers and/or community-based | |||||

| From 2002, ANC clinics to PW (partial subsidy via voucher); this followed an integrated campaign to children < 5 (free) earlier in 2002 | Ghana, 1 district (Lawra)29,30 | HH survey in 2006 (475 HH, 674 children < 5); uncontrolled cross-sectional study | After campaign and ANC delivery, 2006: HH ITN ownership, 74%; ITN use among children < 5, 60% | HH asset index; equity ratio | Household ITN ownership: equity ratio, 0.95; ITN use among children < 5: equity ratio, 1.08 |

| From 2000, retail to GP; after 2004, MCH clinics to PW and children < 5 in rural areas (partial subsidy) | Kenya, national28 | National survey in 2003; monitoring of net sales for MCH sales in 2005c | 2003: HH ITN ownership, 31%; 24% ITN use in < 5, 24%; 2005: 90% of ITNs sold via MCH | Urban/rural residence | 2003 HH survey: ITN use among children < 5 of 51% in urban areas and 17% in rural areas |

| From 2002, MCH clinics to PW and children < 5; after 2003, to GP by community-based groups (partial subsidy) | Malawi, national3,39,40 | DHS in 2000 and 2004c | Before campaign, 2000: HH ITN ownership, 13%; ITN use among children < 5, 8% After campaign, 2004: HH ITN ownership, 43%; ITN use among children < 5, 38% |

Not reported | Not reported |

| From 1997, HF, community-based and retailers to GP (partial subsidy) | United Republic of Tanzania, 2 districts (Kilombero, Ulanga)36–38 | Demographic Surveillance System in 1997 (10 313 HH, 240 children < 2), 1998 (646 children < 1), 2000 (101 children < 1); cluster survey in 1999 (757 HH with children < 5) | Before campaign, 1997: HH ITN ownership, 37%; ITN use among children < 2, 10% After campaign, 1998: ITN use among children < 1, 45%; 2000: ITN use among children < 1, 54%; 1999: ITN use among children < 5, 18% |

Not reported | Not reported |

| From 2004, ANC clinics to PW (partial subsidy via voucher at retailer) | United Republic of Tanzania, national32–35 | HH survey in 2005 (6199 HH, 5567 children < 5), 2006 (6260 HH, 5815 children < 5), 2007 (6198 HH, 6186 children < 5) | HH ITN ownership, 18% in 2005, 29% in 2006 and 36% in 2007; ITN use among children < 5, 12% in 2005, 21% in 2006 and 26% in 2007 | Asset index | ITN use among children < 5; equity ratio, 0.11 in 2005 and 0.29 in 2007 |

| HF and community volunteers to GP (partial subsidy) from 1998 in 3 intervention districts |

Zambia, 5 districts (Chipata, Lundazi, Chama, Chadiza, Petauka)21

|

Quasi-experimental study (nonrandomized), HH survey in 2000 (2986) |

Comparison districts: HH ITN ownership, 1.3% Intervention districts: HH ITN ownership, 14%; P < 0.001 |

Asset index |

Comparison districts: concentration index of HH ITN ownership, 0.71 Intervention districts: concentration index of HH ITN ownership, 0.34 |

| Time-limited | |||||

| Full subsidy (free); stand-alone campaign | |||||

| ANC clinics to PW (free) and stand-alone net campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2007 | Uganda, 2 districts (Adjumani, Jinja)27 | HH survey in 2007 (Adjumani: 520 HH; Jinja: 547 HH); uncontrolled cross-sectional studyd | After campaign: ITN use among children < 5, 93% in Adjumani and 56% in Jinja | Asset index | ITN use among children under 5: concentration index, 0.08 |

| ITN only campaign to children < 5 and PW (free) 2005–2006 | Zanzibar, 2 districts (Micheweni, North A)41 | HH survey in 2006 (Micheweni: 245 HH, 380 children < 5; North A: 264 HH, 389 children < 5); uncontrolled cross-sectional study | After campaign, 2006: ITN use in children < 5, 57% in Micheweni and 87% in North A | Asset index | ITN use among children under 5: equity ratio, 1 in North A and 0.69 in Micheweni |

| Full subsidy (free); integrated with public health campaign | |||||

| Distribution integrated with measles vaccination campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2002 and ANC to PW (partial subsidy via voucher) later in 2002 | Ghana, 1 district (Lawra)29,30 | HH survey in 2003 (475 HH, 674 children < 5) (uncontrolled cross-sectional study) | After campaign, 2003: HH ITN ownership, 90%; ITN use among children < 5, 60% | HH asset index | ITN use among children < 5: equity ratio, 1 (similar across quintiles) |

| Distribution integrated with measles vaccination campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2006 | Kenya, 4 districts (Kwale, Bondo, Greater Kisii, Makueni)42,43 | Before-and-after survey in 2004 (2687 HH, 3719 children < 5), 2006 (2589 HH, 3257 children < 5) | Before campaign, 2004: HH ITN ownership, 24.5%; ITN use among children < 5, 7% After campaign, 2006: HH ITN ownership, 79%; ITN use among children < 5, 67% |

Asset index | HH ITN ownership in 2006: equity ratio, 1.1 (equal across quintiles) v. 1.2 in 2004. |

| Distribution integrated with measles vaccination campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2007 | Madagascar, 59 districts44 | HH survey in 2008 (2860 HH, 2369 children < 5); uncontrolled cross-sectional study | After campaign, 2008: HH LLIN ownership, 77%; LLIN use among children < 5, 81% | Asset index | HH LLIN ownership: equity ratio, 1.05 |

| Distribution integrated with polio vaccination campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2005 and 2006 | Niger, national50 | HH survey in 2006 (2450 HH); uncontrolled cross-sectional studyd | After campaign, 2006: HH ITN ownership, 65%; ITN use among children < 5, 56% | Asset index | HH ITN ownership: equity ratio, 0.79 |

| Distribution integrated with MDA for LF campaign to PW and children < 5 (free) in 2004 | Nigeria, 2 districts (Kanke, Akwanga)51 | HH survey in 2005 (290 HH, 473 children < 5); uncontrolled cross-sectional study | After campaign, 2005: HH ITN ownership, 74%; ITN use among children < 5, 39% | Not reported | Not reported |

| Distribution integrated with measles vaccination campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2004 | Togo, national47,48 | Before-and-after survey in 3 districts in 2004 (Yoto: 495 HH, 718 children < 5; Ogou: 564 HH, 798 children < 5; Tone: 645 HH, children < 5), 2005 (Yoto, 648 HH, 998 children < 5; Ogou: 594 HH, 893 children < 5; Tone: 586 HH, 922 children < 5) | Before campaign, 2004: HH ITN ownership, < 1% in 3 surveyed districts (Yoto, Ogou and Tone) After campaign, 2005: HH ITN ownership, 55%, 59% 70% in Yoto, Ogou and Tone, respectively; ITN use among children < 5, 36%, 44% and 81% in Yoto, Ogou and Tone, respectively |

Asset index | HH ITN ownership in 2005: equity ratio, 1.00, 1.31 and 1.05 in Yoto, Ogou and Tone districts, respectively; 2004: equity ratio, not available |

| Distribution integrated with measles vaccination campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2005 | United Republic of Tanzania, 1 region (Lindi)45 | HH survey in 2005 (574 HH, 354 children < 5); uncontrolled cross-sectional study | After campaign, 2005: HH ITN ownership, 37%; ITN use among children < 5, 21.5% | Asset index | HH ITN ownership equity ratio, 0.86 |

| Distribution integrated with measles vaccination campaign to children < 5 (free) and ANC to PW (partial subsidy via voucher at retailer) in 2004–2005 | United Republic of Tanzania, 1 district (Rufiji)46 | HH survey in 2006 (1752 HH, 732 children < 5); uncontrolled cross-sectional study | After campaign, 2006: ITN use among children < 5, 40% | Asset index | Overall HH ITN ownership: concentration index, 0.13; free nets campaign: concentration index, 0.02 |

| Distribution integrated with measles vaccination campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2003 | Zambia, 5 districts (Chilubi, Kaputa, Mambwe, Nyimba, Kalalushi)49 | HH survey in 2003 (1705 rural HH, 369 urban HH); uncontrolled cross-sectional studye | After campaign, 2003: HH ITN ownership, 88% in rural areas and 82% in urban areas; ITN use among children < 5, 56% in rural areas and 77% in urban areas | Asset index | HH ITN ownership: equity ratio, 0.88 in rural areas and 1.19 in urban areas |

ANC, antenatal care; CHW, community health worker; cRCT, cluster randomized controlled trial; DHS, demographic and health survey; GP, general population; HF, health facility; HH, household; LF, lymphatic filariasis; LLIN, long-lasting insecticidal nets; MCH, maternal and child health; MDA, mass drug administration; NMCP, national malaria control programme; PW, pregnant women; SM, social marketing.

a Studies may appear in more than one category if multiple strategies were used to deliver ITNs at scale or if strategies changed over time.

b For concentration indexes, values of 0 indicate equitable distribution; values > 0 indicate inequitable distribution benefiting the least poor group. For equity ratios, values of 1 indicate equitable distribution; ratios > 1 suggest that the poorest quintiles were favoured.

c Total no. of households included in the study was not reported.

d Total no. of children under 5 included in the study was not reported.

e Denominators for households and children under 5 are equal because the index child (i.e. youngest child in household who was aged ≥ 6 months at time of the campaign) was included in the calculation.

Strategies for delivering ITNs at scale

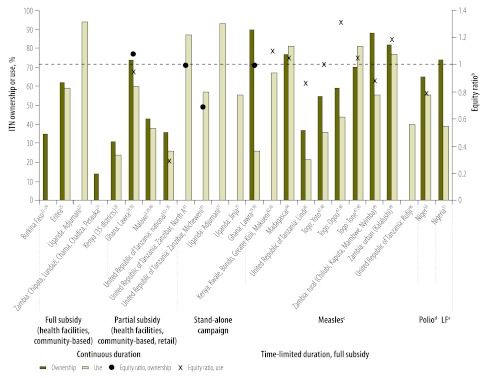

Fig. 3 summarizes the characteristics of the strategies used to deliver ITNs at scale using the categories presented by Kilian et al.14 Routine health services, retailers and community-based agents were used to deliver ITNs on a continuous basis. Time-limited strategies either integrated the distribution of ITNs with a public health campaign or delivered ITNs through a stand-alone campaign. Most continuous strategies partially subsidized the delivery of ITNs, whereas all time-limited strategies fully subsidized delivery of ITNs. Most strategies that used routine health services targeted pregnant women or children under 5. All strategies involving time-limited integrated campaigns and stand-alone campaigns targeted children under 5, whereas strategies using retailers and community-based delivery provided ITNs to the general population. Seven studies used a combination of strategies.

Fig. 3.

Equity ratios and prevalence of household ownership of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and use among children aged < 5 years in areas with endemicity for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria, by delivery strategya,3,21–25,27–30,32–35,39–51

a Studies may appear in more than one category if multiple strategies were used to deliver ITNs at scale or if strategies changed over time.

b Value of 1 indicated equitable distribution, marked on figure by a red dashed line. Ratios > 1 suggest that the poorest quintiles were favoured.

c Campaign integrated with measles vaccination campaign.

d Campaign integrated with polio vaccination campaign.

e Campaign integrated with mass drug administration for lymphatic filariasis (LF) campaign.

Studies with high ITN ownership or use

Eighteen studies reported ITN ownership among households and/or ITN use among children under 5 (Table 2). ITN ownership among households ranged from 1.3% to 94% and ITN use among children under 5, which is typically lower than the prevalence of household ITN ownership, ranged from 12% to 94%. Ten studies reported a high prevalence of ITN ownership or use during at least one survey conducted after initiation of the ITN delivery strategy. Six reported ownership by > 60% of households,25,42–44,47,48,50,51 two reported ownership by > 80% of households29,30,49 and two reported use by ≥ 87% of children under 5.27,41

Of the six studies reporting ownership by > 60% of households, four used an uncontrolled cross-sectional survey design, surveying 300–3000 households 1–3 years after delivery began.25,44,50,51 The other two used a before-and-after design in which approximately 2500 households were surveyed before and one year after ITN delivery during campaigns integrated with measles vaccination.42,43,47,48 During the 1–2-year period between baseline and endline surveys, ITN ownership among households increased from 24.5% to 79% in one study and from < 1% to 55–70% in the other.

The two studies reporting ITN ownership by > 80% of households were uncontrolled cross-sectional surveys. A total of 475 households in Ghana29,30 and 2074 households in Zambia49 were surveyed five months and six months, respectively, after ITN delivery campaigns. ITN ownership in Ghana was 90%, whereas ownership in Zambia was 88% in rural areas and 82% in urban areas. In Ghana, a follow-up survey conducted 38 months after the initial survey revealed that ownership among households had decreased by 18%, to 74%.

Both studies reporting a high prevalence of ITN use among children under 5 also had an uncontrolled cross-sectional design. A total of 378 households in the Adjumani district of Uganda were surveyed 5–7 months after distribution of partially subsidized ITNs to pregnant women through antenatal care clinics27 and 264 households in the North A district of Zanzibar were surveyed 5 months after ITN delivery during a stand-alone ITN campaign.41 Responses revealed use by 94% of children under 5 in households surveyed in the Adjumani district and by 87% of children under 5 in the North A district.

All 10 studies that reported a high prevalence of ITN ownership or use provided fully subsidized ITNs through at least one component of their delivery strategy (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Seven studies provided fully subsidized ITNs through a stand-alone campaign only (in one41) or through an integrated campaign only (in six42–44,47–51). One study considered the continuous delivery of free ITNs through antenatal clinics.25 Two studies evaluated combined strategies.27,29,30 In one, ITNs were delivered to pregnant women through antenatal clinics on a continuous basis by use of a partially subsidized voucher system and to children under 5 through a campaign integrated with measles vaccination, at full subsidy.29,30 In the other, ITNs were delivered under a full subsidy to pregnant women through antenatal clinics on a continuous basis and for free to children under 5 during a stand-alone campaign on a time-limited basis.27

Equity of ITN ownership and use

Thirteen studies reported coverage stratified according to socioeconomic status as a measure of equity (Table 2). One study evaluated equity on the basis of urban and rural residence and twelve studies evaluated it on the basis of a household asset index. Of the latter studies, three reported a concentration index and nine reported an equity ratio. A concentration index ranges from −1 to 1, with a value of 0 indicating equitable distribution and values > 0 indicating inequitable distribution benefiting the least poor group. An equity ratio measures the equity of distribution in the poorest quintile relative to that in the least poor quintile, with a value of 1 indicating equitable distribution and values between 0 and 1 indicating inequitable distribution benefiting the least poor group.

The study that evaluated equity in terms of urban and rural residence was based on data from a national survey performed after partially subsidized delivery of ITNs to pregnant women and children under five at health centres.28 The survey found greater use among children under 5 in urban areas, compared with those in rural areas (51% versus 17%).

Three studies presented the concentration index of ITN ownership among households or ITN use among children under 5. The concentration index in each revealed higher ITN ownership or use among the least poor groups. One study had a quasi-experimental design and evaluated continuous delivery of partially subsidized ITNs through health care facilities.21 The other two used a cross-sectional design to assess the fully subsidized delivery of ITNs during a stand-alone campaign27 or during a campaign integrated with measles vaccination.46

Nine studies presented the equity ratio, or sufficient data for its calculation, of ITN ownership among households or ITN use among children under 5 (Fig. 3). The highest ownership was reported in the poorest quintile in four campaigns that integrated the delivery of free ITNs with measles vaccination. Two of the four used a cross-sectional design to evaluate strategies at either the national or district levels.44,49 The other two used a before-and-after design and also reviewed delivery at the district or national levels.42,43,47,48 The change in equity index was available only for one of the before-and-after studies and involved a decrease from 1.2 to 1.1.42,43

ITN use was similar across quintiles in two studies, both of which used an uncontrolled cross-sectional survey design of delivery at the district level. The strategy evaluated in one delivered ITNs during a stand-alone campaign.41 The other investigated a combined strategy involving delivery of fully subsidized ITNs to children under 5 through a campaign integrated with measles vaccination and partially subsidized ITNs to pregnant women through antenatal clinics.29,30

In five studies, ITN ownership or use was higher in the least poor quintile. Three studies evaluated the delivery of free ITNs to children under 5 through a campaign integrated with polio or measles vaccination in Niger, in Lindi region of the United Republic of Tanzania, and four rural districts of Zambia (Chilubi, Kaputa, Mambwe and Nyimba).45,49,50 In the fourth study, the delivery of partially subsidized ITNs to pregnant women via antenatal care clinics in the United Republic of Tanzania was examined.32–35 The fifth study reviewed a stand-alone ITN campaign involving distribution of fully subsidized nets to children under 5 in the Micheweni district of Zanzibar.41

Study quality

Table 2 shows the variety of study designs used to assess ITN delivery strategies. Of the 18 studies reporting data on ITN ownership among households and ITN use among children under 5, the study design in two (a cluster-randomized controlled trial22–24 and a quasi-experimental study without randomization21) involved comparison areas, and the study design in four involved a temporal comparison. Two of the studies with a temporal comparison evaluated time-limited delivery of fully subsidized ITNs42,43,47,48 and two analysed continuous delivery of partially subsidized ITNs.3,36,38–40 As such, the interpretation of ITN ownership among households and ITN use among children under 5 between survey years varies by study design and delivery strategy.

Only the cluster-randomized controlled trial directly compared different delivery strategies.22–24 One strategy involved subsidized sale, promoted by social marketing, of ITNs to the general population plus free distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets to pregnant women at antenatal care clinics. The other strategy involved only subsidized sale, promoted by social marketing, of ITNs to the general population through retailers. Ownership of ITNs was 35% in the dual-intervention arm and 23% in the retail-only arm (P < 0.001). Although the risk of bias was low in this study, the quality of the evidence was downgraded from high to moderate on the basis of the GRADE criteria because it was unclear whether analyses adjusted for the clustered design and because no relative measure of effect was provided.

One study described the delivery of partially subsidized ITNs at the district level through sales by health facility staff.21 ITN ownership was 14% in three intervention districts, compared with 1.3% in two comparison districts (P < 0.001). The risk of bias in this study was moderate principally because of the lack of randomization. The quality of evidence was very low on the basis of the GRADE criteria because there were important differences between intervention and comparison areas at baseline (e.g. socioeconomic status) that were not adjusted for in the analysis and because no relative measure of effect was provided.

In nonrandomized studies, identification of the channel through which the ITN is delivered (i.e. antenatal clinics or retail shops) may help determine whether the change in coverage achieved can be allocated to the delivery strategy.12 Studies in three countries did not stratify ITN ownership by delivery channel.3,36–40,47,48 However, elsewhere, a decline in the proportions of unsubsidized ITNs sourced from retailers and partially subsidized ITNs sourced from maternal and child health clinics was seen among children under 5.42,43 Both decreases occurred after initiation of an integrated campaign in 2006 to distribute fully subsidized ITNs, with the campaign contributing almost half of the ITNs used by children under 5 surveyed during 2006–2007.

Costs

Ten studies reported on the cost or cost-effectiveness of ITNs (Table 3). Of these, seven described only cost per ITN delivered or cost per treated-net–year. The remaining three were cost-effectiveness studies that also presented cost per death or per disability-adjusted life year averted. All except one of the economic evaluation studies conducted sensitivity analyses around the major cost and outcome parameters.

Table 3. Characteristics associated with financial and economic costs of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) in areas with endemicity for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria, by delivery strategya.

| Delivery strategy | Country, scale | Perspective, interval | Cost |

Net lifespanc | Sensitivity analysis | Outcomed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial | Economic | Distributionb | ||||||

| Continuous | ||||||||

| Full subsidy (free); routine health services (ANC clinic) and/or community-based | ||||||||

| ANC clinics to PW (free); implemented in 2006 | Burkina Faso, 1 district (Kossi)22 | Societal, 2006–2007 | ANC clinic: provider costs for MoH, including training, supervision, LLIN transport | Capital costs annualized (LLINs over 5 y, vehicles over 7 y) and discounted (3%); all prices at 2006 levels were converted to US dollars; detailed opportunity costs were calculated for space and personnel on project | ANC clinic: ITNs, 23%; transport, 15%; staff, 54% | LLIN, 5 years (physical and treatment) | Discount rate; LLIN lifespan; costs of transport, personnel, rent and IEC materials; leakage of LLINs | Financial cost per LLIN delivered, US$ 8.20; economic cost per LLIN delivered, US$ 5.47 (range: 5.38–6.83); all outcomes were most sensitive to LLIN lifespan and leakage |

| From 2001, ANC clinics to PW (free) and in HF and CHW to GP (full cost; free after 2003) | Eritrea, national (Stevens)25 | Provider, 2001–2005 | All direct costs to provider, including commodities, delivery, IEC activities, staff, taxes | Capital costs were annualized and discounted (3%); all prices at 2005 levels converted to US dollars; Shared costs for personnel and space on project calculated | ITNs and insecticide, 64%; staff, 21% | ITN, 3-year physical lifespan; new ITN or retreatment provide 1 TNY | Discount rate; ITN cost, use, lifespan and effectiveness; proportion of shared costs | Outcomes most sensitive to ITN costs and shared cost allocation: financial cost per ITN delivered, US$ 10.67; financial cost per TNY, US$ 3.23; economic cost per ITN delivered, US$ 9.00 (range: 7.44–23.29); economic cost per TNY, US$ 2.74 Outcomes most sensitive to ITN effectiveness and use: cost per child death averted, US$ 3276 (range: 1637–13 104); cost per DALY averted, US$ 100 (range: 81–398) |

| ANC clinics to PW (free) in 2001 | Kenya, 35 districts26 | Provider, 2001 | ITNs and transport (international, to district, to ANC facilities) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Financial cost per ITN delivered to ANC clinics, US$ 7.64; financial cost per ITN delivered to PW, US$ 10.54 |

| ANC clinics to PW (free) in 2007 | Uganda, 2 districts (Adjumani, Jinja)27 | Provider, 2007 | Detailed costs of LLINs, transport, storage, distribution, IEC activities, training, personnel | Capital costs annualized (ITNs over 3 y, vehicles over 7.5 y); shared costs of personnel time and overhead; all costs were incurred in 2007, so no inflation adjustment was made; prices converted to US dollars | LLIN transport, 33%; IEC, 23%; training, 23%; and management, 12%e | LLIN, 3 years (physical and treated) | Discount rate; LLIN lifespan and cost; net use and retention | Financial cost per LLIN delivered, US$ 8.83; economic cost per LLIN delivered, US$ 5.89 (range: 4.93–7.08); economic cost per TNY, US$ 1.96; all outcomes were most sensitive to LLIN lifespan |

| Partial subsidy; routine health services (HFs; ANC and/or MCH clinics) and/or retailers and/or community-based | ||||||||

| Retail to GP (partial subsidy); implemented in 2006 | Burkina Faso, 1 district (Kossi)22 | Societal, 2006–2007 | Retailer: provider costs incurred by NGO, wholesalers and shopkeepers, including transport, storage, labour, profit, IEC materials | Capital costs annualized (LLINs over 5 y, vehicles over 7 y) and discounted (3%); all prices at 2005 levels were converted to US dollars; detailed opportunity costs for space and personnel; user contribution calculated difference between provider’s financial costs and actual costs recovered | Retail: ITNs, 23%; wholesaler/retailers, 25%; staff 22% | LLIN, 5 years (physical and treatment) | Discount rate; LLIN lifespan; costs of transport, personnel, rent and IEC materials; leakage of LLINs | Financial cost per LLIN delivered, US$ 9.19; economic cost per LLIN delivered, US$ 5.47 (range: 5.38–6.83); all outcomes were most sensitive to LLIN lifespan and leakage |

| From 2002, MCH clinics to PW and children < 5; after 2003, to GP by community-based groups (partial subsidy) | Malawi, national3 | Provider, 1999–2003 | Capital and recurrent costs, including ITNs, vehicles, staff, brand creation, advertising, promotion | Capital costs annualized (ITNs over 5 y, brand over 7 y, vehicles over 8 y) and discounted (3%); all prices at 1999 levels converted to US dollars | ITNs, 55%; staff, 10%; supplies/ overhead, 10%; fuel, 9% | ITN, 5-year physical lifespan; treatment provides 0.5 TNY | Not reported | Average economic cost per ITN delivered, US$ 11.16 (decreased from US$ 21.39 in 1999 to US$ 8.15 in 2003 as number of ITNs distributed increased, suggesting economies of scale); average economic cost per TNY, US$ 18.72 (decreased from US$ 32.64 in 1999 to US$ 14.60 in 2003) |

| From 1997; HF, community-based delivery and retailers to GP (partial subsidy) | United Republic of Tanzania, 2 districts (Kilombero, Ulanga)36 | Provider, user, 1996–2000 | Capital and recurrent costs divided into set-up (branding, sensitization) and ongoing supply (ITNs, personnel, transport, training, promotion) | Capital costs annualized (ITNs over 5 y, brand over 7 y, vehicles over 10 y) and discounted (3%); opportunity costs providers and users (including price for ITN); all prices at 2000 levels converted to US dollars | ITNs and insecticide, 31%; staff, 28%; other recurrent costs, 32% | ITN, 5-year physical lifespan; treatment provides 0.5 TNY | Health measures (ITN coverage, inclusion of untreated nets, duration of effectiveness) | Economic cost per TNY, US$ 25.09 and US$ 12.57 if insecticide lasts 6 and 12 months, respectively; economic cost per child death averted, US$ 2924 (range: 1101–1909); economic cost per DALY averted, US$ 107 (range: 41–69); all outcomes were sensitive to all measured assumptions |

| From 2004, ANC clinics to PW (partial subsidy via voucher at retailer) |

United Republic of Tanzania, national35

|

Provider, user, 2004–2006 |

Capital and recurrent costs, including formative research, planning, training, vehicles, ITNs, IEC, personnel, overhead |

Capital costs annualized (ITNs over 3 y, vehicles over 8 y) and discounted (3%); opportunity costs for providers and users (including top up paid for ITN); all prices at 2006 levels converted to US levels |

ITN: 20% subsidised, 8% to user 8%; staff, 25%; promotion activities, 16% |

ITN, 3-year physical lifespan; new ITN or retreatment provide 1 TNY |

Discount rate; user top up; ITN price, effective lifespan and re-treatment use; LLINs |

Financial cost per ITN delivered, US$ 12.09; economic cost per ITN delivered, US$ 10.77 (range: 10.53–12.23); economic cost per TNY, US$ 6.02 (range: 5.88–12.03]; economic cost per child death averted, US$ 1 242 (range: 1 219–2496); all outcomes were most sensitive to ITN lifespan and use |

| Time-limited | ||||||||

| Full subsidy (free); stand-alone campaign | ||||||||

| Stand-alone net campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2007 | Uganda, 2 districts (Adjumani, Jinja)27 | Provider, 2007 | Detailed costs of LLINs, transport, storage, distribution, IEC activities, training, personnel | Capital costs annualized (ITNs over 3 y, vehicles over 7.5 y); Shared costs of personnel time and overheads; all costs were incurred in 2007, so no inflation adjustment was made; prices converted to US dollars | Distribution, 30%; LLIN transport, 15%; registration, 16%; IEC, 13%e | LLIN, 3 years (physical and treated) | Discount rate, LLIN lifespan and cost; net use and retention | Financial cost per LLIN delivered, US$ 8.30 (Jinja) and US$ 9.49 (Adjumani); economic cost per LLIN delivered, US$ 3.86 (Jinja) and US$ 4.76 (Adjumani) (range: 2.91–6.06); economic cost per TNY, US$ 1.29 (Jinja) and US$ 1.58 (Adjumani); all outcomes were most sensitive to LLIN lifespan |

| Full subsidy (free); integrated with public health campaign | ||||||||

| Distribution integrated with measles vaccination campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2002 | Ghana, 1 district (Lawra)30 | Provider, 2002 | ITNs, transportation, training, supervision, social mobilization; campaign costs that would have been incurred for measles vaccination without inclusion of ITNs were excluded | Not reported | Financial costs only; ITNs, 91%; other elements of delivery, 9% | Not reported | Not reported | Financial cost per ITN delivered, US$ 11.53 |

| Distribution integrated with measles vaccination campaign to children < 5 (free) in 2005 | United Republic of Tanzania, 1 region (Lindi)45 | Provider, 2005 | ITNs, transport to district, IEC activities, NMCP staff | Not included | Financial costs only: ITNs 88%; other elements of delivery, 12% | Not reported | Not reported | Financial cost per ITN delivered, US$ 3.71 |

| Distribution integrated with measles vaccination campaign to children < 5 | Zambia, 5 districts (Chilubi, Kaputa, Mambwe, Nyimba, Kalalushi49 | Provider, 2003 | ITNs, transport, training, IEC activities; campaign costs that would have been incurred for measles vaccination without inclusion of ITNs were excluded | Not reported | Financial costs only: ITNs, 94%; other elements of delivery, 6% | Not reported | Not reported | Financial cost per ITN delivered, US$ 10.88 in rural areas and US$ 11.79 in urban areas |

ANC, antenatal care; CHW, community health worker; DALY, disability-adjusted life year; GP, general population; HF, health facility; IEC, information education communication; LLIN, long-lasting insecticide-treated net; MCH, maternal and child health; MoH, ministry of health; NGO, nongovernmental organization; NMCP, national malaria control programme; PW, pregnant women; TNY, treated-net-year (incorporates ITNs and retreatment kits distributed); US$, United States dollars.

a Studies may appear in more than one category if multiple strategies were used to deliver ITNs at scale or if strategies changed over time.

b Reported as the percentage of total economic costs (unless specified otherwise). Only main costs are reported.

c Defined as physical viability and duration of insecticide protection.

d Adjusted for inflation and reported in 2010 US dollars to allow comparison across different countries and years.

e Reported as the percentage of total costs, excluding LLIN cost.

Four studies investigated the cost of delivering free ITNs through antenatal care clinics, with three at the district level and one at the national level. In the district-level studies, financial costs ranged from US$ 8.20 to US$ 10.54 per ITN delivered22,26,27 and economic costs ranged from US$ 5.47 to US$ 5.89 per ITN delivered.22,27 The study at the national scale reported an economic cost of US$ 10.77 per ITN delivered.25,35

Of the four studies that evaluated the delivery cost of partially subsidized ITNs, three investigated delivery through the retail sector and one investigated voucher use. Studies of retail-based delivery reported financial costs of US$ 5.47 and US$ 11.16 per ITN delivered in Burkina Faso and Malawi, respectively, and of US$ 12.57 and US$ 18.72 per treated-net–year in the United Republic of Tanzania and Malawi, respectively.3,22,36 The studies in Burkina Faso and the United Republic of Tanzania were at the district level and the study in Malawi was at the national level; the length of protection afforded by ITNs in calculations of cost per ITN delivered was assumed to be 12 months in Burkina Faso and 6 months in Malawi. The fourth study investigated the Tanzanian National Voucher Scheme and found economic costs of US$ 10.77 per ITN delivered and US$ 6.02 per treated-net–year, with the latter calculation assuming 12-month protection from a treated net.35

The four studies that evaluated fully subsidized campaigns found financial costs per ITN delivered of US$ 3.71 to US$ 11.79 for those integrated with vaccination campaigns30,45,49 and US$ 9.48 for a stand-alone campaign.27 The stand-alone campaign considered in one of the studies had an economic cost per ITN delivered of US$ 4.76.27

Three studies presented some measure of health impact. The economic cost per child death averted was US$ 1242 for a national voucher scheme35 and US$ 2924 for a retail sector programme involving partially subsidized delivery.36 The economic cost per disability-adjusted life year averted was similar, at US$ 100 and US$ 107.25,36

Cost or cost-effectiveness estimates were most sensitive to the assumed ITN lifespan (i.e. physical viability and duration of insecticide protection) and the proportion of ITNs actually used (leakage). The main cost associated with ITN delivery programmes was the ITNs themselves, most often followed by staff and transport.

Factors influencing ITN delivery

Information on factors influencing delivery of ITNs at scale was available for 12 of 20 studies (Table 4). Important perceived influences on the delivery of ITNs at scale, from the perspective of actors involved, were categorized into those at the user level, the implementer or health system level and the policy level.52

Table 4. Barriers to and facilitators of scaling up delivery of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) in areas with endemicity for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria, by delivery strategy and implementation level.

| Variable | Continuous |

Time-limited |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At cost, partial subsidy or no subsidy; community-based21,24 | Full subsidy; ANCa,25–27 | Partial subsidy; ANC and MCH clinicsa,3,31,33,39,40 | Partial subsidy; retail3,23,28,31,33,39,40 | Free; stand-alone campaign27,41 | Free; campaign integrated with public health campaigna,48,49 | ||

| User level | |||||||

| Cost | Barrierb | – | Barrier | Barrier | – | – | |

| Implementer/health system level | |||||||

| Functioning outreach system | Facilitator | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lack of clarity of guidelines | – | Barrier | – | – | Barrier | – | |

| Training and supervision | – | Facilitator | Facilitator | Facilitator | Facilitator | Facilitator | |

| Implementation by provider not according to guidelines | – | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | – | Barrier | |

| Health staff overburdened | – | – | – | – | – | Barrier | |

| Record keeping | – | Facilitator | Facilitator | – | – | – | |

| Stock-out of nets or vouchers | – | – | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | |

| Poor logistics for procurement or transport of nets | – | – | Barrier | – | Barrier | Barrier | |

| Policy level | |||||||

| Stakeholder involvement | – | Facilitator | Facilitator | Facilitator | Facilitator | Facilitator | |

| Cooperation between departments and ministries | – | Facilitator | Facilitator | Facilitator | Facilitator | Facilitator | |

| Instability of financing | Barrier | Barrier | – | Barrier | – | – | |

| Regulation amendment | – | – | – | Facilitator | – | – | |

ANC, antenatal care; MCH, maternal and child health.

a Information was principally from discussion sections of papers, with the following exceptions: stakeholder interviews in Ghana,31 Kenya26 and Nigeria51 and case study of scaling up ITNs in the United Republic of Tanzania.33

b For partially subsidised delivery by community volunteers in Zambia.21

Facilitators at the implementation level included provision of training and appropriate supervision and support. At the policy level, facilitators included involvement of relevant stakeholders during planning and implementation and cooperation across ministries, departments and sectors (e.g. health and retail). Several barriers were identified, including costs to users for partially subsidized strategies, variation in implementation due to insufficient supplies of ITNs and vouchers and to poor communication and adherence to distribution procedures, and, at the policy level, financial resources to sustain current and future distribution strategies.

Discussion

Strategies frequently used to deliver ITNs at scale reported in the published and grey literature include continuous delivery of partially subsidized ITNs through the health sector and retail outlets, continuous delivery of free ITNs though antenatal care clinics and time-limited delivery of free ITNs, either alongside other public health goods (usually vaccines) during integrated campaigns or through stand-alone ITN campaigns. Few experiences with continuous delivery by community-based agents were recorded. The majority of strategies delivered to a targeted population of children under 5 or pregnant women. Seven studies from six countries described multiple concurrent or sequential delivery strategies, particularly continuous strategies in combination with a time-limited campaign.

These studies showed wide variability in ITN ownership among households and ITN use among children under 5. Although findings of high ownership or use were largely drawn from uncontrolled studies, strategies reviewed in the majority of studies included at least one component that delivered ITNs at a full subsidy. The majority of equity evidence was from uncontrolled studies: in general, strategies that used time-limited delivery of fully subsidized ITNs were equitable or pro-poor, in contrast to strategies that used continuous delivery of partially subsidized ITNs. No equity evidence from fully subsidized continuous strategies was available.

Comparisons of costs and cost-effectiveness across these strategies are challenging because of variations in the methods of economic analysis used and in the scale of delivery, as emphasized previously.53 Nonetheless, the cost of delivering ITNs across the strategies was reasonably comparable. The main cost was the ITNs themselves, a cost frequently supported by donor funding, and all of the cost-effectiveness estimates were most sensitive to ITN lifespan and proportion of ITNs actually used.

This review aimed to synthesize details on the context of, barriers to and facilitators of strategies to deliver ITNs at scale, some of which were implemented under near-programmatic conditions. Important factors influencing the delivery of ITNs at scale were similar across delivery strategies. Barriers involving cost were common at the user level, whereas barriers involving stock-outs and poor logistics for ITN procurement and transport were common at the implementer level. Training and supervision of staff was often highlighted as a facilitator at the implementer level and cooperation across departments or ministries and stakeholder involvement were highlighted at the policy level.

The evaluation of large-scale health programmes has been highlighted as a “top priority in global health”54 and researchers have emphasized that the use of randomized designs for such evaluation may be inappropriate because of low external validity.11,55 Therefore, to characterize the full breadth of ITN delivery strategies and to synthesize evidence that corresponded to the conditions under which large-scale ITN delivery may occur in practice, we included a variety of study designs.56 However, this made interpretation of findings challenging, particularly because a before-and-after study of a campaign conducted at a single time point is qualitatively different from annual surveys conducted during a continuous distribution strategy.

The Medical Research Council recommends that the evaluation of complex interventions include information on the context and implementation of interventions. Our experience in conducting this review suggests that future synthesis of evidence involving large-scale delivery of complex public health interventions would benefit from improved consistency of reporting of the implementation process by included studies.57,58 Recommendations for reporting are available from the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) statement.59

It is simplistic to interpret the findings of this review as providing a single recommendation to policy-makers on which ITN delivery strategy to adopt. Rather, the review highlights that choosing among alternatives depends on contextual factors, such as the epidemiologic characteristics of malaria, attributes of health systems and contextual constraints. Moreover, the review demonstrates how a framework for characterizing delivery strategies can prove useful in synthesizing evidence, which may help policy-makers formulate implementation strategies to deliver ITNs to populations in their local settings.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark Petticrew and Neil Spicer (Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) and Rifat Atun (Imperial College London, formerly with The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria) for helpful comments.

Funding:

This review was supported by the Alliance for Health Services and Policy Research, World Health Organization, which commissioned this work as a background paper for the First Global Symposium on Health Systems Research.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.World malaria report Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller DH, Wiseman V, Bakusa D, Morgah K, Dare A, Tchamdja P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of insecticide-treated net distribution as part of the Togo Integrated Child Health Campaign. Malar J. 2008;7:73. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens W, Wiseman V, Ortiz J, Chavasse D. The costs and effects of a nationwide insecticide-treated net programme: the case of Malawi. Malar J. 2005;4:22. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiseman V, Hawley WA, ter Kuile FO, Phillips-Howard PA, Vulule JM, Nahlen BL, et al. The cost-effectiveness of permethrin-treated bed nets in an area of intense malaria transmission in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68(Suppl):161–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lengeler C. Insecticide-treated bed nets and curtains for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD000363. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000363.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global strategic plan: roll back malaria 2005–2015 Geneva: Roll Back Malaria Partnership; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Targeted subsidy strategies for national scaling up of insecticide-treated netting programmes – principles and approaches Geneva: Global Malaria Programme, World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willey B, Smith L, Armstrong Schellenberg J. How to scale up delivery of malaria control interventions: a systematic review using insecticide-treated nets, intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy, and artemisinin combination treatment as tracer interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010 (background paper for the First Global symposium on Health Systems Research). Available from: http://www.hsr-symposium.org/images/stories/5scale_up_delivery_malaria_control.pdf [accessed 4 July 2012].

- 9.Mangham LJ, Hanson K. Scaling up in international health: what are the key issues? Health Policy Plan. 2010;25:85–96. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scaling up health service delivery: from pilot innovations to policies Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habicht JP, Victora C, Vaughan J. Evaluation designs for adequacy, plausibility and probability of public health programme performance and impact. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:10–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webster J, Chandramohan D, Hanson K. Methods for evaluating delivery systems for scaling-up malaria control intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:S8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-S1-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webster J, Kweku M, Dedzo M, Tinkorang K, Bruce J, Lines J, et al. Evaluating delivery systems: complex evaluations and plausibility inference. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:672–7. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilian A, Wijayanandana N, Ssekitoleeko J. Review of delivery strategies for insecticide treated mosquito nets: are we ready for the next phase of malaria control efforts? TropIKA Net J. 2010;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/ [accessed 20 August 2012]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Britten N, Arai L, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:A7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pope M. Synthesising qualitative research. In: Pope C, Mays N, Popay J, editors. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative health evidence: a guide to methods. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2007. pp 142-152. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Monetary Fund [Internet]. World Economic Outlook Database April 2011. Washington: IMF; 2012. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/01/index.htm [accessed 16 August 2012].

- 20.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff JGAD, The PRISMA Group The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agha S, Van Rossem R, Stallworthy G, Kusanthan T. The impact of a hybrid social marketing intervention on inequities in access, ownership and use of insecticide-treated nets. Malar J. 2007;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Allegri M, Marschall P, Flessa S, Tiendrebeogo J, Kouyate B, Jahn A, et al. Comparative cost analysis of insecticide-treated net delivery strategies: sales supported by social marketing and free distribution through antenatal care. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25:28–38. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beiersmann C, De Allegri M, Sanon M, Tiendrebeogo J, Jahn A, Mueller O. Community perceptions on different delivery mechanisms for insecticide-treated bed nets in rural Burkina Faso. Open Public Health J. 2008;1:17–24. doi: 10.2174/1874944500801010017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müller O, De Allegri M, Becher H, Tiendrebogo J, Beiersmann C, Ye M, et al. Distribution systems of insecticide-treated bed nets for malaria control in rural Burkina Faso: cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yukich JO, Zerom M, Ghebremeskel T, Tediosi F, Lengeler C. Costs and cost-effectiveness of vector control in Eritrea using insecticide-treated bed nets. Malar J. 2009;8:51. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyatt HL, Gotink MH, Ochola SA, Snow RW. Free bednets to pregnant women through antenatal clinics in Kenya: a cheap, simple and equitable approach to delivery. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:409–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolaczinski JH, Kolaczinski K, Kyabayinze D, Strachan D, Temperley M, Wijayanandana N, et al. Costs and effects of two public sector delivery channels for long-lasting insecticidal nets in Uganda. Malar J. 2010;9:102. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tilson D. The social marketing of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) in Kenya. Cases Public Health Comm Mark 2007;1:1-20. Available from: http://www.gwumc.edu/sphhs/departments/pch/phcm/casesjournal/volume1/commissioned/cases_1_12.pdf [accessed 26 June 2012]

- 29.Grabowsky M, Nobiya T, Selanikio J. Sustained high coverage of insecticide-treated bednets through combined catch-up and keep-up strategies. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:815–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grabowsky M, Nobiya T, Ahun M, Donna R, Lengor M, Zimmerman D, et al. Distributing insecticide-treated bednets during measles vaccination: a low-cost means of achieving high and equitable coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:195–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kweku M, Webster J, Taylor I, Burns S, Dedzo M. Public-private delivery of insecticide-treated nets: a voucher scheme in Volta Region, Ghana. Malar J. 2007;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]