Abstract

Objective To assess the impact of leaflets encouraging patients to raise concerns and to discuss symptoms or other health related issues in the consultation.

Design Randomised controlled trial.

Setting Five general practices in three settings in the United Kingdom.

Participants 636 consecutive patients, aged 16-80 years, randomised to receive a general leaflet, a depression leaflet, both, or neither.

Main outcomes Mean item score on the medical interview satisfaction scale, consultation time, prescribing, referral, and investigation.

Results The general leaflet increased patient satisfaction and was more effective with shorter consultations (leaflet 0.64, 95% confidence interval 0.19 to 1.08; time 0.31, 0.0 to 0.06; interaction between both -0.045, -0.08 to—0.009), with similar results for subscales related to the different aspects of communication. Thus for a 10 minute consultation the leaflet increased satisfaction by 7% (seven centile points) and for a five minute consultation by 14%. The leaflet overall caused a small non-significant increase in consultation time (0.36 minutes, -0.54 to 1.26). Although there was no change in prescribing or referral, a general leaflet increased the numbers of investigations (odds ratio 1.43, 1.00 to 2.05), which persisted when controlling for the major potential confounders of perceived medical need and patient preference (1.87, 1.10 to 3.19). Most of excess investigations were not thought strongly needed by the doctor or the patient. The depression leaflet had no significant effect on any outcome.

Conclusions Encouraging patients to raise issues and to discuss symptoms and other health related issues in the consultation improves their satisfaction and perceptions of communication, particularly in short consultations. Doctors do, however, need to elicit expectations to prevent needless investigations.

Introduction

Effective doctor-patient communication probably improves patient satisfaction and health outcomes.1 Modifying doctors' behaviour and empowering patients (patient “activation”) are two ways that patients can be encouraged to bring their concerns and agenda to the consultation. In patients with particular chronic diseases this can be by intensive counselling and for most other conditions by leaflets.1 Patient satisfaction and consultation time have generated mixed results when patients have been encouraged to write lists or to use patient activation leaflets before a consultation.2-10 Few of these studies, however, were from typical UK primary care settings, most were small (< 200 patients), some were not randomised, and few reported changes in number of investigations or referrals. Patient activation might help bring difficult issues such as depression to the consultation, where detection rates are low, where training of doctors does not help, and where outcomes vary when doctors are informed about a patient with depression.11-18

General practitioners have concerns about the effects of patient activation on time and patients' introspection and anxiety.1,3,4,7,8,19 Pressures may also be increased on the doctor to prescribe, refer, or investigate. We aimed to assess in the range of patients presenting in primary care whether patient activation leaflets improve patient satisfaction and health outcomes and whether they increase consultation time and the number of prescriptions, referrals, and investigations and help doctors to detect depression.

Methods

Our study sample comprised 636 patients, aged 16-80 years, consulting at one of five general practices in the United Kingdom (two in deprived urban areas, two in market towns, and one in a city). Patients were excluded if they were receiving specialist psychiatric treatment (for example, for schizophrenia), had dementia, were too unwell to consent, were receiving treatment for depression, or were only collecting a prescription.

Patient satisfaction was measured on the medical interview satisfaction scale and its subscales. Scores reflect aspects of doctor-patient communication (relieving distress, intention to comply with management decisions, communication, and rapport) and correlate strongly with a patient centred approach.20

Sample size calculation

Patient satisfaction

To achieve a 0.30 standard deviation change in satisfaction or any other continuous outcome, we required 350 patients or a minimum of 500, allowing for 30% loss to follow up. The probability of an α error was 0.05 and of a β error was 0.2.

Detection of depression

Assuming that 20% of the patients were depressed and that 75% of these in the intervention arm and 50% in the control arm had previously undiagnosed depression detected, then we needed 116 depressed patients or 580 patients in the intervention arm (assuming 20% were depressed) and 610 in the control arm, allowing for 5% loss to follow up.

Randomisation

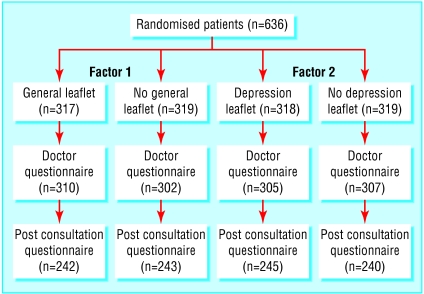

Recruitment occurred mostly in short periods (4-6 weeks) in the winter months during 2000-2 according to the availability of research staff. Patients were given information about the study on arrival for consultation and gave written consent. To ensure similar numbers of participants in each group, randomisation was by number tables in blocks of four (figure). Treatment allocation was concealed in sealed opaque numbered envelopes, prepared at the study centre. The envelopes contained questionnaires and a blank slip of paper or a leaflet. Patients were randomised to one of four groups, defined by two factors: factor 1, general leaflet and no leaflet; factor 2, depression leaflet and no leaflet. Patients in the first group received a general leaflet, asking them to list issues they wanted to raise and explaining that the doctor wanted them to be able to talk, discuss, and ask questions about any problems they were concerned about. Patients in the second group received a leaflet on depression, listing symptoms of depression (without labelling them as such) and asking whether they had had any of these and, if so, that the doctor would like to discuss them. Patients in the third group received both leaflets, and patients in the fourth group received no leaflets (control group).

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through trial

Data collection

Patients completed a questionnaire before the consultation, recording what they wanted in terms of examination, prescription, investigation, or referral.21-23 They also completed the hospital anxiety and depression scale.24,25

After the consultation the patients completed a questionnaire for age, marital status, number of children, employment status, medical problems, general health (World Organization of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians scale), resolution of symptoms (measure yourself medical outcome profile score, a patient generated measure), satisfaction, and “enablement”—the extent to which patients feel helped to manage their illness.25-27 Doctors recorded the duration of the consultation (time between patient being called and patient leaving consultation), whether they thought the patient was depressed, whether they prescribed, investigated, or referred, how much they thought these interventions were medically needed, and the pressure they felt from patients to undertake these.

Analysis

Data were analysed on an intention to treat basis with SPSS and STATA for Windows, estimating robust standard errors by controlling for clustering by doctor. We used logistic regression to determine whether leaflets increased the detection of depression or increased the number of referrals or investigations and multiple linear regression to assess whether leaflets affected patient satisfaction (primary outcome) or other secondary outcomes (enablement, consultation time, and symptom resolution). Given the dangers of type I errors with multiple statistical tests, we report significant results among secondary outcomes with caution. In each model we first assessed interaction between leaflets. If no interaction was found, we presented the main effects. Because we recruited few patients for doctors with shorter consultation times, we assessed the interaction between consultation time and the effect of leaflets.

Results

We recruited fewer patients from doctors with short (< 9 minutes) consultation times (14 v 30) because we had less time in which to comply with study protocols before the consultation. We obtained information on 45 consecutive patients booked to see doctors with long consultation times (where nearly all eligible patients could be approached): 14 (31%) were excluded (six were receiving treatment for anxiety or depression, four were out of our age range, two were too ill, and two only collected prescriptions). Seventeen of the 31 eligible patients (55%) agreed to participate. They had similar characteristics to those who did not agree to participate. The whole study population was similar to previous national samples for age, and for being male, in paid work, and married (table 1).28

Table 1.

Characteristics of groups. Values are numbers (percentages) of patients unless specified otherwise

| Characteristic | General leaflet | No general leaflet | Depression | No depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) consultation time | 10.64 (1.85) | 10.67 (1.94) | 10.57 (1.81) | 10.74 (1.97) |

| Male | 135 (43) | 134 (42) | 136 (43) | 133 (42) |

| New problem | 133 (43) | 145 (47) | 134 (43) | 144 (47) |

| Longstanding problem | 138 (45) | 129 (42) | 133 (43) | 134 (44) |

| Doctor asked patient to attend the practice | 73 (24) | 78 (25) | 81 (26) | 70 (23) |

| Wanting investigation | 72 (23) | 79 (25) | 74 (24) | 77 (25) |

| Wanting referral | 51 (16) | 64 (21) | 57 (18) | 60 (19) |

| Investigation medically needed | 86 (29) | 80 (26) | 86 (25) | 90 (30) |

| Referral medically needed | 48 (19) | 57 (24) | 64 (21) | 68 (23) |

| Married | 174 (73) | 166 (68) | 175 (72) | 165 (69) |

| Having sickness certificate | 19 (8) | 18 (8) | 20 (8) | 17 (7) |

| Having disability benefit | 11 (5) | 9 (4) | 10 (4) | 10 (5) |

| In paid work | 132 (55) | 127 (52) | 138 (56) | 121 (50) |

| Seeing usual doctor | 220 (71) | 224 (72) | 223 (72) | 221 (71) |

Denominators vary owing to missing values.

We received all questionnaires completed before the consultation, 418 (76%) of those completed after the consultation, and 612 (96%) completed by the doctors. Non-responders to the post consultation questionnaire were equally distributed between groups (general leaflet 75/317 (24%), depression leaflet 72/318 (23%)), similar to those who completed the study.

Satisfaction and perceived communication

We found no significant interactions between the two leaflets for any outcome and thus present the main effects (table 2). No significant changes were found in any of the outcomes for either of the leaflets, except for satisfaction: 0.17 represents a 6% (six centile point) increase in satisfaction. Both consultation time and the general leaflet were significantly associated with improved satisfaction, and the leaflet was significantly more effective when consultations were short, even after clustering by doctor was allowed for (leaflet 0.64, 95% confidence interval 0.19 to 1.08; time 0.31, 0.0 to 0.06; interaction between both -0.045, -0.08 to -0.009). This meant that for consultations lasting five, eight, and 10 minutes, satisfaction increased by 14%, 10%, and 7%, respectively. The effect of the leaflet on subscales for satisfaction was similar when the interaction with time was allowed for: comfort from communication 1.02 (0.36 to 1.68), relief of distress 0.74 (0.0 to 1.49), intention to comply with management decisions 0.65 (0.06 to 1.23), and rapport 0.81 (0.16 to 1.45).

Table 2.

Effect of leaflets on outcomes. Values are means (95% confidence intervals) for control arms and mean differences (95% confidence intervals) for intervention arms unless stated otherwise

|

General leaflet

|

Depression leaflet

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No leaflet | Leaflet | P value | No leaflet | Leaflet | P value |

| Satisfaction* | 5.25 (5.14 to 5.36) | 0.17 (0.01 to 0.32) | 0.04 | 5.34 (5.23 to 5.46) | −0.03 (−0.15 to 0.08) | 0.56 |

| Time (min) | 10.51 (10.05 to 10.97) | 0.36 (−0.54 to 1.26) | 0.42 | 10.52 (10.06 to 10.98) | 0.34 (−0.27 to 0.95) | 0.27 |

| Depression score† | 4.04 (3.59 to 4.49) | 0.02 (−0.62 to 0.67) | 0.94 | 4.23 (3.78 to 4.68) | −0.37 (−0.98 to 0.24 | 0.23 |

| Anxiety score† | 6.33 (5.77 to 6.89) | −0.13 (−0.74 to 0.48) | 0.67 | 6.35 (5.81 to 6.90) | −0.17 (−0.87 to 0.53) | 0.62 |

| Overall score | 10.37 (9.46 to 11.28) | −0.10 (−1.12 to 0.91) | 0.35 | 10.58 (9.67 to 11.49) | −0.54 (−1.71 to 0.62) | 0.35 |

| State trait anxiety inventory | 11.00 (10.50 to 11.50) | −0.23 (−0.73 to 0.27) | 0.35 | 10.77 (10.28 to 11.25) | 0.25 (−0.42 to 0.91) | 0.45 |

| Enablement | 3.74 (3.24 to 4.24) | 0.29 (−0.29 to 0.88) | 0.31 | 3.86 (3.36 to 4.37) | 0.04 (−0.66 to 0.75) | 0.91 |

| Resolution of symptoms at one month‡ | 3.58 (3.39 to 3.77) | −0.04 (−0.31 to 0.24) | 0.78 | 3.63 (3.43 to 3.82) | −0.14 (−0.39 to 0.12) | 0.28 |

Medical interview satisfaction scale.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale.

Measure yourself medical outcome profile.

Effect of leaflet on doctors' behaviour

The general leaflet increased the number of investigations (odds ratio 1.43, 1.00 to 2.05 after control for clustering for doctor). Perceptions of the medical need for investigation and of patients' expectations strongly predicted investigation.29 After controlling for these potential confounders we found that the effect of leaflets on investigations was unlikely to be due to either chance or confounding (odds ratio 1.87, 1.10 to 3.19). Most of the increase in number of investigations (90 v 71—that is, 19 extra) was among patients in whom investigations were thought not to be needed or slightly needed (14 extra: leaflet 41 (46%), no leaflet 27 (38%)). In the study population there were 60 consultations where the doctor thought the pressure from patients was moderate or strong, but of these patients only 20 (33%) actually reported a moderate or strong preference for investigation.

Detection of depression

Overall, 80 patients (16%) had possible major depression (score of ≥ 8 on the hospital anxiety and depression scale). Of these patients the doctors judged 45 to be depressed and 35 not depressed. Neither leaflet significantly increased the detection of depression (table 3).

Table 3.

Odds of detecting depression according to leaflet type. Values are numbers (percentages) of doctors detecting depression in patients with possible major depression

| Leaflet | Depression correctly detected (n=45) | Depression not detected (n=35) | Odds ratio*(95% CI) | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | 21 (47) | 15 (43) | 1.04 (0.43 to 2.52) | 0.93 |

| Depression | 19 (42) | 16 (46) | 0.97 (0.40 to 2.38) | 0.95 |

Score of ≥8 on hospital anxiety and depression scale indicated possible major depression.

Adjusted mutually for each leaflet.

Wald test.

Discussion

Encouraging patients to raise concerns and to discuss symptoms or other health related issues in the consultation improves their satisfaction and perceived communication, particularly when consultation time is limited. However, doctors need to elicit expectations to prevent needless investigations.

Limitations of study

One limitation of our study was that consultation time had an impact on recruitment; if doctors kept to time it was difficult for us to recruit patients because we had less time to complete the initial study protocols. The impact of this selection bias was probably to underestimate the effect of the leaflets on outcome.

The prevalence of undetected depression (16%) was slightly less than in previous studies, and we had fewer patients than the power calculation required.30,31

Although some patients may not have had sufficient time to read the leaflets before consultation, we found that the greatest effect of leaflets was with short consultations, which meant less time available before the consultation. To avoid contamination, we needed to distribute individual leaflets, but in practice there are other more pragmatic approaches, such as videos or posters in the waiting room and practice booklets and newsletters.

Detecting depression

Training doctors about depression has been shown to be of little benefit.15 Our study suggests that encouraging patients to discuss symptoms of depression during consultation is also unlikely to be beneficial.

Patient satisfaction

Encouraging patients to ask their doctor questions improves their perception of communication within the consultation and hence overall satisfaction without increasing time significantly. This supports evidence that improved communication does not necessarily greatly increase consultation time.1 The ineffectiveness of encouraging patients to raise issues in longer consultations is presumably due to doctors allowing sufficient time for the patient's agenda to be more fully discussed anyway.27 All subscales of satisfaction were affected, including those most related to communication (relief of distress, comfort from communication), the rapport between doctor and patient, and intention to comply with management. Since intention strongly predicts subsequent behaviour, the effectiveness of management decisions should be improved by encouraging patients to raise issues and to discuss symptoms in the consultation.32

What is already known on this topic

Evidence is mixed about whether empowering patients with leaflets or lists may improve outcomes of consultations, and there are concerns about consultation time

The effect on health service costs of empowering patients is unclear

Training doctors to detect depression or informing them of a patient with depression does not improve outcome

What this study adds

Empowering patients using leaflets is not likely to improve the detection of depression

Leaflets increase patient satisfaction and their perception of communication, particularly for short consultations

Leaflets do not greatly increase consultation time but may increase the number of investigations

If patients are encouraged to raise concerns and discuss symptoms in consultations, doctors need to elicit expectations to prevent needless investigations

Requested investigations

Controlling for the major potential confounders of patients' expectation and perceived medical need suggests that the increase in number of requested investigations with leaflets is not likely to be due to chance or confounding. It is also plausible that by raising more concerns and discussing symptoms in the consultation doctors may respond with more investigations. Most of the increase in requested investigations was in categories where the doctor did not think there was a strong medical need. This highlights the importance of the need for doctors to discuss patients' expectations for investigation, particularly if a patient activation approach is used.

We thank the staff of the practices and patients for their help and interest in the study.

Contributors: PL had the original idea for the study which was developed by all authors. MD, JS, and KS ran the study on a day to day basis, and with PL analysed the results. All authors contributed to writing the paper. PL will act as guarantor for the paper. The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: Southampton University.

Competing interests: None declared. JS can no longer be contacted but PL states she has no competing interests.

Ethical approval: Salisbury and Southampton and South West Hants ethics committees.

References

- 1.Stewart M. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ 1995;152: 1423-33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson S, Nanni C, Schwankovsky L. Patient oriented interventions to improve communication in a medical office visit. Health Psychol 1990;9: 390-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albertson G, Lin C, Schilling L, Cyran S, Anderson S, Anderson R. Impact of a simple intervention to increase primary care provider recognition of patient referral concerns. Am J Managed Care 2002;8: 375-81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hornberger J, Thom D, MaCurdy T. Effects of a self-administered previsit questionnaire to enhance awareness of patients' concerns in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12: 597-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frederikson L, Bull P. Evaluation of a patient education leaflet designed to improve communication in medical consultations. Patient Educ Counsel 1995;25: 51-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabak E. Encouraging patient question-asking: a clinical trial. Patient Educ Counsel 1998;12: 37-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Middleton J. Written lists in the consultation: attitudes of general practitioners to lists and the patients who bring them. Br J Gen Pract 2002;44: 309-10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCann S, Weinman J. Empowering the patient in the consultation: a pilot study. Patient Educ Counsel 1996;27: 227-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butow PN, Dunn S, Tattersall M, Jones Q. Patient participation in the cancer consultation: evaluation of a question prompt sheet. Ann Oncol 1994;5: 199-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleissig A, Glasser B, Lloyd M. Encouraging out-patients to make the most of their first hospital appointment: to what extent can a written prompt help patients get the information they want? Patient Educ Counsel 1999;38: 69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pill R, Prior L, Wood F. Lay attitudes to professional consultations for common mental disorder: a sociological perspective. Br Med Bull 2001;57: 207-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore R. Improving the treatment of depression in primary care: problems and prospects. Br J Gen Pract 1997;47: 587-90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmin C, Klocek J. To screen or not to screen: symptoms identifying primary care medical patients in need of screening for depression. Int J Psychol Med 1998;28: 293-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kendrick T. Why can't GPs follow guidelines on depression? BMJ 2002;320: 200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson C, Kinmonth A, Stevens L, Peveler R, Stevens A. Effects of a clinical practice guideline and practice-based education on detection and outcome of depression in primary care: Hampshire depression project randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355: 185-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeling P, Rao B, Paykel E. Unrecognised depression in general practice. BMJ 1985;290: 1880-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon G, von Korff M. Recognition, management and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med 1995;4: 99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowrick C, Buchan I. Twelve month outcome of depression in general practice: does detection or disclosure make a difference? BMJ 1995;311: 1274-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coulter A. After Bristol: putting patients at the centre. BMJ 2002;324: 648-51. [With commentary by N Dunn.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Moore M, Warner G, Gould C, et al. An observational study of patient-centeredness in primary care, and its relationship to outcome. BMJ 2001;323: 908-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Britten N, Ukoumunne O. The influence of patients' hopes of receiving a prescription on doctors' perceptions and the decision to prescribe: a questionnaire survey. BMJ 1997;315: 1506-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacFarlane J, Holmes W, MacFarlane R, Britten N. Influence of patients' expectations on antibiotics management of acute lower respiratory illness in general practice: questionnaire study. BMJ 1997;315: 1211-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cockburn J, Pit S. Prescribing behaviour in clinical practice: patients' expectations and doctors' perceptions of patients' expectations—a questionnaire study. BMJ 1997;315: 520-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zigmond A, Snaith R. The hospital anxiety and depression rating scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67: 361-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkin D, Hallam L, Doggett AM. Measures of need and outcome for primary health care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- 26.Paterson C. Measuring outcomes in primary care: a patient generated measure, MYMOP, compared with the SF-36 health survey. BMJ 1996;312: 1016-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howie J, Heaney D, Maxwell M, Walker J, Freeman G, Rai H. Quality at general practice consultations: cross sectional survey. BMJ 1999;319: 738-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Her Majesty's Stationery Office, Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Morbidity statistics from general practice: fourth national study 1991. London: HMSO, 1994.

- 29.Little P, Dorward M, Warner G, Stephens K, Senior J, Moore M. The importance of patient pressure and perceived medical need for investigations, referral, and prescribing in primary care: observational nested study. BMJ 2004;328: 444-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kendrick T, Stevens L, Bryant A, Goddard J, Stevens A, Thompson C. Hampshire depression project: changes in the process of care and cost consequences. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51: 911-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostler K, Thompson C, Kinmonth AL, Peveler R, Stevens L, Stevens A. Influence of socio-economic deprivation on the prevalence and outcome of depression in primary care. Br J Psychol 2001;178: 12-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armitage C, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol 2001;40: 471-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]