Abstract

In eukaryotic cells, actin filaments are involved in important processes such as motility, division, cell shape regulation, contractility, and mechanosensation. Actin filaments are polymerized chains of monomers, which themselves undergo a range of chemical events such as ATP hydrolysis, polymerization, and depolymerization. When forces are applied to F-actin, in addition to filament mechanical deformations, the applied force must also influence chemical events in the filament. We develop an intermediate-scale model of actin filaments that combines actin chemistry with filament-level deformations. The model is able to compute mechanical responses of F-actin during bending and stretching. The model also describes the interplay between ATP hydrolysis and filament deformations, including possible force-induced chemical state changes of actin monomers in the filament. The model can also be used to model the action of several actin-associated proteins, and for large-scale simulation of F-actin networks. All together, our model shows that mechanics and chemistry must be considered together to understand cytoskeletal dynamics in living cells.

Introduction

Actin filaments play central roles in important cellular processes such as motility, division, morphogenesis, cell-shape regulation, and mechanosensation. In cells, actin monomers polymerize into dynamic filaments that form an entangled network. Filaments in the network are constantly undergoing changes such as polymerization and depolymerization, branching and severing/fragmentation. This dynamic morphological change enables the network to remodel itself in response to external stimuli. Actin polymerization and depolymerization have been studied in vitro and in vivo (1–3). The mechanical properties of actin networks also have been examined in a range of experiments, from single filaments (4–6) to networks with actin-associated proteins (7). These experiments demonstrate that actin possesses unique mechanical and chemical properties, yet many of these observations have not been explained theoretically. In particular, a unified model does not exist where the mechanics and chemistry of actin are considered together on an equal footing. Here, we develop such a mechanochemical model, and demonstrate that forces can have a strong influence on actin chemistry. This mechanochemical coupling may explain some of the unique properties of actin in the cell. The model is also applied to examine the role of several actin-associated proteins. The model represents an intermediate scale description of actin filaments, which provides a crucial link from the molecular scale to the cytoplasmic cellular scale.

There have been many important studies on the unique roles of actin in the cell. For instance, a molecular mechanism of actin-driven cell motility, together with the action of actin-associated proteins have been proposed (1,8,9). Actin filaments polymerize at the cellular leading edge, and extend the membrane forward. Arp2/3 promotes branching of new filaments from existing filaments. Slightly behind the leading edge, ADF/cofilin promotes severing of existing actin filaments (1,10,11) while transmembrane integrin adhesions form between filaments and the extracellular substrate to anchor the leading edge. These processes are known to control the filament length distribution and dynamics of filament turnover (12,13). Dynamics of actin filaments are also known to be involved in other important cellular functions such as endocytosis (14,15) and cytokinesis (15,16). A common feature during these processes is that actin filaments are under the action of mechanical forces, either from the cell membrane or molecular motors. Actin network remodeling, together with the activity of nonmuscle myosin II and adhesion molecules, also play a crucial role in cellular mechanosensation (17–19). A recent modeling study has shown how actin-myosin bundles (stress fibers) can form in response to cell substrate mechanical stiffness (19); although, it is also pointed out that actin filaments alone can have mechanosensing properties (20). These properties mostly arise from structural changes in the actin filament under external forces. Therefore, an improved understanding of actin mechanical response and how forces can regulate actin chemistry are important for elucidating the mechanisms of actin function in the cell.

Actin filament is a staggered double helix formed by nucleation and directional polymerization of G-actin monomers (3). The monomers that polymerize on the same helix are connected via longitudinal bonds (noncovalent interaction), whereas the monomers on two opposite helices interact through diagonal bonds. The intrinsic bond energy of a longitudinal bond was shown to be three times larger than a diagonal bond (21). The filament subunits can be found in three bound nucleotide states, ATP, ADP, and the reaction intermediate ADP.Pi. The bonds between subunits with ATP are lower in free energy (22). Recent studies (23–25) have proposed full atomistic models of actin filaments by fitting the known atomic structures of G-actin monomers into low resolution electron microscopy images. However, there is accumulating evidence that F-actin is an inherently polymorphic filament (20,26–28). The structural polymorphism also potentially affects the mechanical properties of single filaments.

Mechanical properties of actin filaments and networks have been studied extensively (7,29). In particular, computational (30,31) and experimental (4–6,32) studies on the persistence length of the actin filament have been performed. Although the average persistence length with all subunits in the ATP state (F-ATP) is ∼17μm, the data show a large variation ranging from several to a few tens of microns (5). One of the factors that can affect bending stiffness is the nucleotide state of the subunits, i.e., ATP or ADP (4,33). From computational studies, F-ATP was found to be twice as stiff as F-ADP, and this is attributed to a structural change of DNase I-binding loop in subdomain 2 (34,35). The identity of the bound nucleotide is not the only factor that could affect filament stiffness. Due to the helical structure of F-actin, mechanical coupling of bending and twist was shown to be important, especially for short filaments (36). In addition, factors such as ions, pH, drugs, and other proteins can change filament behavior (4). Actin interacts with >100 different actin-binding proteins (ABPs) and these interactions alter the intrinsic mechanical properties of actin filaments and networks. Among these, Arp2/3 and cofilin are two well-studied examples (37,38). Cofilin cooperatively severs actin filaments by increasing the intrinsic longitudinal bond length and decreasing the pitch of the staggered helical actin structure while the actin filament length stays the same (20,39,40). Furthermore, cofilin-decorated actin filaments are experimentally found to be four times softer than standard F-Actin (40). It was shown that the most probable location of severing on the filament is at the boundaries between the cofilin decorated and bare actin region (41,42). On the other hand, Arp2/3 promotes actin filament branching by nucleating new filaments at an angle 70° with respect to the mother filament (43). A recent experimental study showed that Arp2/3 binds preferentially to the convex side of a bent filament (44). This has clear implications on filament branching, especially at the cellular cortex region where actin is under large bending forces.

Chemical and mechanical properties of actin have been two separate directions for modeling studies. Extensive experimental studies (2) have provided rich information on chemical kinetics of actin and its binding partners, and paved the way for elaborate simulations (42,45–49). Mechanical behaviors of actin monomers (34) and filament models (31,40) have been studied with detailed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. However, MD currently cannot access filament-scale biologically relevant phenomena. Therefore, coarse-grained models have been proposed at the cost of lost atomistic detail (30,50–52). The elastic rod theory has been also previously used to study F-actin buckling and force production (53) and filament severing by cofilin (54). These studies provide important insights into global F-actin behavior. How the global behavior is affected by the interaction between helical strands and nonlinearities such as local perturbations on elasticity, single actin subunit kinematics, and cooperativity yet remains as an active area of research. To fully understand the role of actin in the cell however, it is important to develop models that can examine the interplay between mechanics and chemistry (55). Currently, a detailed mechanochemical model of actin filaments does not exist. In this work, we build a simple mechanical model of the actin filament that can simultaneously compute filament deformations as well as internal chemical kinetics. We parameterize the model using available experimental and computational data, and use the model to address chemical state changes when the filaments are under external forces. The model combines stochastic chemical dynamics with mechanical deformations. We outline the basic framework of the model in the next section. After the discussion of the obtained results, we address how the model can be improved for larger scale simulations and predictions.

Methods

The model

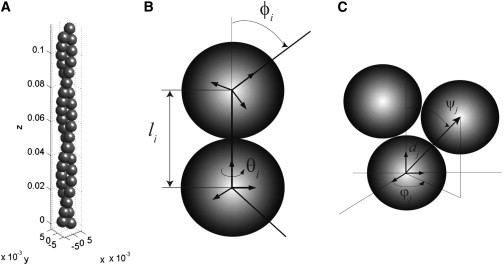

The undeformed actin filament is a straight double helical structure shown in Fig. 1 A. The monomer is roughly 6 nm in diameter and the pitch of the double helix is 72 nm (56). Within the double helix, monomers bind to each other through noncovalent interactions, forming longitudinal bonds between monomers in each helical strand and diagonal bonds between adjacent monomers in opposite helical strands (21). The monomer is also structurally asymmetric. Therefore, the configuration of the monomer is described by the position of its center of mass as well as a coordinate frame that describes its orientation in space. We describe the interaction between actin monomers using a set of linear and angular bonds. The bond variables are described in Fig. 1. The details of the mechanical model are given in the Supporting Material.

Figure 1.

Coarse-grained model of an actin filament. (A) The model represents the filament as two helical chains of monomers staggered with respect to each other. The configuration of the filament is described by bond distances, bond angles, and local material frames attached to each monomer (see Methods). (B) The interaction between intrastrand monomers is defined by bond distance l, relative twist angle θ, and relative bending angle φ. (C) The interaction between interstrand monomers is defined by bond distance d, relative twist angle ϕ, and relative bending angle ψ. For detailed definitions, see Methods.

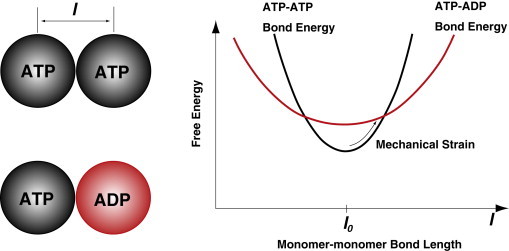

In addition to the mechanical model, monomers in F-actin can have either ATP, ADP.Pi, or ADP in the nucleotide pocket. The mechanical properties of the monomers depend on its chemical state (Fig. 2). Therefore, our mechanical bond model depends on the chemical states of the monomers. In this work, we specify the parameters for ATP-ATP and ADP-ADP bonds (Table 1). The details are given in the Supporting Material.

Figure 2.

Force-induced chemical state change of monomers in actin filaments. As a schematic example, ATP-ATP bond and ATP-ADP bond energies are plotted as a function of bond length. At equilibrium, , the ATP-ATP bond is favored. However, due to differences in the bond stiffness, as the bond is stretched, the ATP-ADP bond can become favorable, leading to a change in the monomer chemical state.

Table 1.

Bond stiffness parameters, bond free energies, and intrinsic geometric parameters for our model

| ATP-ATP | ADP-ADP | |

|---|---|---|

| [pN/ ] | 2.50 × 105 | 1.60 × 105 |

| [pN ] | 0.81 | 0.53 |

| [pN | 0.52 | 0.01 |

| [pN/ ] | 1.81 × 105 | 1.75 × 105 |

| [pN ] | 24.3 | 21.5 |

| [pN ] | 29.1 | 27.7 |

| −20.07 | −18.07 | |

| −8.08 | −6.08 | |

| [nm] | 6.00 | 6.00 |

| θ [°] | 28.55 | 28.55 |

| φ [°] | −6.43 | −6.43 |

| [nm] | 6.00 | 6.00 |

| [°] | 104.27 | 104.27 |

| [°] | 60.00 | 60.00 |

Finally, when actin filaments are under external force, the applied force will influence chemical transitions in the monomers. We investigate the influence of this mechanochemical coupling by developing a simple model for the transition rate between chemical states. We use this model and the Gillespie simulation algorithm to investigate how F-actin deforms under forces.

Results

Model predictions of F-actin deformation under load

We use our F-actin model to investigate mechanical deformation as a function of the applied force. Stretching and bending deformation calculations are performed for varying filament lengths and applied forces. In each calculation, we consider changes in the chemical state of the monomer: i.e., where all the monomers are either in ATP or ADP states, respectively.

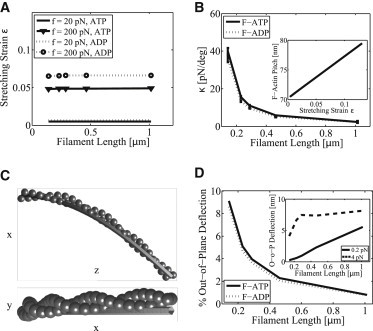

In Fig. 3 A, the equilibrium strain, , as a function of stretching force f is plotted for several different forces and lengths. As expected, an actin filament with ADP in the catalytic site is softer than with ATP. We find that ε is a linear function of the applied force for up to pN. The stretching modulus can be computed by analyzing the strain as a function of force. We find that the modulus is . In cases where there is a mixture of ATP and ADP monomers in the filament, the modulus is also well described by an interpolation relationship: , where x is the fraction of ATP monomers.

Figure 3.

Mechanical properties of an actin filament according to the coarse-grained model. (A) Stretching strain as a function of force, f, filament length and filament type, F-ATP (solid lines), or F-ADP (dotted lines). (B) κ, stiffness of filament twist-stretch coupling, is shown as a function of filament length, F-ATP (solid lines), F-ADP (dotted lines). Shown in the inset is the increase of average pitch of 0.46 μm long filament as a function of stretching strain. (C) Bent configuration of a 0.145 μm F-ATP and the best two-dimensional fit (plane) thin rod as seen from two different viewing angles. Applied bending force is in x-direction with a magnitude of 4 pN. (D) Percent contribution of the out-of-plane filament tip deflection to the overall tip deflection due to bending as a function of filament length. Applied bending force is 0.2 pN. F-ATP (solid lines), F-ADP (dotted lines). Inset shows the amount of out-of-plane tip deflection for different filament lengths and bending forces, 0.2 pN (solid line), 4 pN (dashed line).

Although F-actin is quite stiff under stretch, because it is helical, stretching deformation is naturally coupled to filament twist. This coupling has been discussed as a possible mechanism of mechanosensation (20). We define κ as the stretch-twist coupling parameter: , where f is the magnitude of the stretching force and Θ is the induced twist at the end of the filament. Fig. 3 B shows κ as a function of filament length, L. The error bars represent results from different stretching forces (20, 100, 200, 400 pN). The plotted relationship obeys the power law where b is around −3/2. In the inset of Fig. 3 B, we see that the F-actin pitch also changes (shown for 0.46 μm ATP filament) as a function of stretching strain. These results indicate that a helical structure must naturally couple twist with the tension in the filament. If there are actin-associated proteins bound on the filament, binding kinetics and conformations of these proteins would be affected by tension. This could be another underlying mechanism during cellular mechanosensation where actin filaments are pulled by myosin motors in stress fibers.

A helical structure such as F-actin will also respond with out-of-plane bending when a force is applied perpendicular to the filament. This is caused by bend-twist coupling, which is also common in other helical bundles such as the coiled coil (57). Using a different model, the twist-bend coupling length of F-actin was predicted to be 0.4 μm (36). This result can be compared to the elastic thin rod theory, which is a standard methodology in defining mechanical properties of biofilaments. Fig. 3 C shows the bending geometry of a 0.145 μm ATP actin filament and the best thin rod theory comparison. In Fig. 3 D, we quantify the out-of-plane deflections in terms of filament length, amount of bending force, and monomer chemical state. From our results, we see that the thin rod theory predicts no out-of-plane bending and therefore is not an accurate model for short actin filaments. For long filaments (>1 μm), the out-of-plane bending is less important. The inset of Fig. 3 D shows that the amount of out-of-plane deflection levels out once a critical filament length and bending force are reached.

Bending persistence length and effects of broken bonds

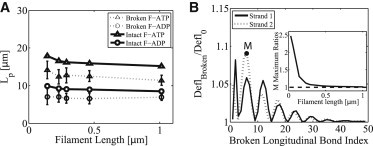

Bending properties of F-actin is important for understanding the mechanical behavior of the cellular cytoplasm and the dynamics of actin network remodeling under force (7). In the cell, actin filaments also experience forces from membranes and other proteins, as well as forces from thermal fluctuations (46). Therefore, it is possible that some of the bonds in the filaments are broken. In addition, monomers in the filament can be either in ATP or ADP states. From the bending simulation results, we can estimate the bending persistence length, , by comparing the bending results of our model with those from the elastic thin rod theory. This comparison serves as a verification of our model and enables us to explore the role of broken bonds and filaments with different monomer chemical states in determining the overall actin network mechanics.

Fig. 4 A shows the obtained bending persistence length values of F-actin with different structural conditions. The obtained persistence lengths of an intact F-ATP and intact F-ADP under 1 pN force are in good agreement with the reported values (4,5), μm. Note that due to the helical nature of the filament, there is some length dependence in . In the second set of the simulations, 5% of all the bonds in the filament are randomly broken. This calculation is repeated 20 times and bending data are averaged. The corresponding error bars for ATP and ADP filaments are shown in Fig. 4 A. As the portion of broken bonds increases, the mean persistence length decreases and the standard deviation increases (data not shown). Note that we compute the persistence length from the comparison of the bending deflection (tip-to-tip vector) projected onto the plane of the applied force because the thin rod theory predicts only the two-dimensional shape of a filament (see Fig. 3 C). Strictly speaking, if we include out-of-plane deflection due to the bend-twist coupling effect, the corresponding persistence length would be slightly lower than the values shown. However, bend-twist coupling is not significant in longer filaments and therefore is ignored.

Figure 4.

Persistence length Lp derived from the mechanical model and the effect of broken bonds. (A) Lp prediction obtained from the fitting thin rod theory to deformations in intact filaments (solid lines). Dotted lines with error bars represent the mean and standard deviation in Lp for filaments with randomly broken bonds (see text for details). All the filaments are bent under 1 pN force. Different chemical states of the filaments are denoted as F-ATP (triangles) and F-ADP (circles). (B) The ratio of bending deflection of a filament with a broken longitudinal bond at a particular index (abscissa) to the deflection of an intact filament. Filament length is 0.29 μm and bent under 4 pN.

The physical location of the broken bond on a filament also strongly influences the overall bending of the filament under force. In Fig. 4 B, we show the ratio of the bending deflection of a 0.29 μm filament under 4 pN with a broken longitudinal bond at a particular index of one strand to the deflection of an intact filament. We observe that broken bonds that are closer to the fixed boundary increase the amount of bending deflection. The effect of the location of the broken bonds on bending also diminishes as filament length increases. We do not observe any significant difference due to breaking of diagonal bonds.

Influence of actin binding proteins

In the cell, a large number of ABPs interact with the filament network and alter the biochemical and mechanical state of the network. Our model can be used to investigate the influence of ABPs on the filament structure. There have been studies of ABPs interacting with actin using MD. In our modeling approach, we can describe the role of ABPs by considering how these proteins can change structural parameters such as and/or stiffness parameters for each monomer. Binding of a single ABP can potentially change these parameters for the bound actin, and these local changes can be amplified to global changes in the actin structure.

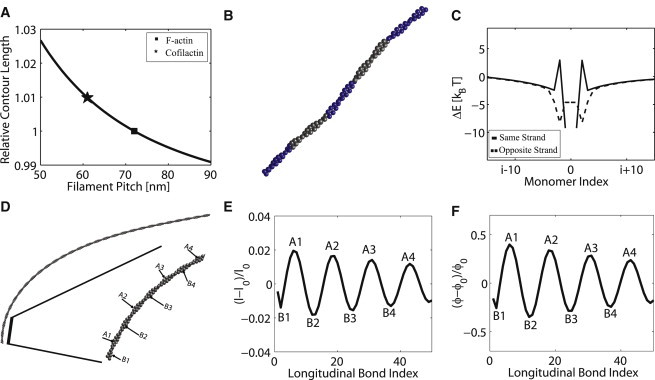

Changes in the F-actin pitch upon ABPs binding has been observed experimentally (39,58). ADF/cofilin is an important ABP whose cellular function is to sever actin filaments by introducing local mechanical deformations. Cofilin binds between two actin monomers and affects the actin-actin longitudinal bond. Therefore, its function can be modeled by changing the longitudinal bond parameters while leaving the diagonal bond unchanged (40). To obtain the change in in response to cofilin binding, we can consider the relationship between the helical pitch and the helical contour length while keeping the filament length and radius fixed. A helical contour is described by the vector where the contour length t ranges from ; , , and P is the helical pitch. If the contour length changes from t to , the changes in the filament length is given by , where is the change in helical contour length, and is obtained with the new pitch . Because cofilin does not appear to change the filament length, we can solve for and using the equation . Fig. 5 A shows the solution of this equation plotted as vs. . This result suggests that the new actin-actin bond length with cofilin, , is ∼1% longer, and the pitch of the cofilin decorated filament is roughly 60 nm.

Figure 5.

Influence of ABPs. (A) The stretch (or compression) strain in the longitudinal bond lengths, l, for a fixed filament length and radius (see text). The stretching strain is shown as a function of changing pitch. (B) Conformation of a 0.29 μm actin filament partially decorated with cofilin in a banded manner. Blue monomers are decorated with cofilin. (C) Cooperative binding energy for a filament with two bound cofilins (see text). The cooperative energy is plotted as a function of relative positions (in terms of actin monomer index) of the cofilins. (D) Conformation of a 1.01 μm F-ATP bent under 0.5 pN. (E) Longitudinal bond strains of the filament shown in D. (F) Angular strain on the longitudinal bonds of the filament shown in D. In both (E) and (F), the peaks and valleys labeled by and correspond to the outer and inner positions labeled in D.

In addition to a change in , it was also showed that upon binding of cofilin, actin monomers tilt toward the helical contour axis by 6°–12° (59). This corresponds to a modification of in our model. Table 2 shows the model parameters for the cofilin modified actin-actin longitudinal bond. Fig. 5 B shows the overall filament conformation with a number of monomers decorated with cofilin. As noted by recent studies (42), we observe that maximum strain occurred at the boundaries between decorated and nondecorated monomers. Finally, Fig. 5 C shows the possible cooperativity when two cofilins are bound to the same filament. Because cofilin changes the bond parameters of a single longitudinal bond, it induces local mechanical strain on the neighboring bonds. We can compute the total strain energy of the filament as a function of distance between two bound cofilins. We define as the difference between the energy of a single filament with two cofilins and two times the energy of the filament with one cofilin. This difference can be thought of as a cooperative binding energy.

Table 2.

Model parameters for bonds in a cofilactin filament

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| [nm] | 6.20 |

| θ [°] | 34.94 |

| φ [°] | −9.34 |

| [nm] | 6.00 |

| [°] | 107.47 |

| [°] | 58.80 |

Fig. 5 C shows that this cooperativity is generally favorable when two cofilin molecules are on the same helical strand, and is always favorable when bound on the opposite strands. The degree of cooperativity decreases as the distance between two cofilins increases. Furthermore, there is anticooperativity between two second nearest neighbor cofilins (i and ) located on the same helical strand. We observe that this is due to a higher cost of compression on subunit on the opposite strand and the twist accumulation on the local diagonal bonds. Another way to understand the action of cofilin is that it introduces a local mechanical defect; these defects can interact over long distances, leading to cooperativity. Note that by stretching the actin-actin bond, cofilin also catalyzes conversion from ATP-actin to ADP (see next section). This leads to eventual filament severing.

Arp2/3 is another ABP whose main cellular function is to nucleate new filaments by creating a branch from an existing filament. A recent study (44) showed that Arp2/3 preferentially binds to the convex side of a curved filament confined on a two-dimensional surface. They explained these phenomena by treating the actin filament as a structureless rod and considering curvature fluctuations of the filament. They proposed that Arp2/3 prefers to bind to highly curved configurations and bending biases the curvature fluctuation. Within our model, actin is a double helix, and without considering fluctuations, we can examine the equilibrium structure when the filament is curved. In particular, we can examine the strains in the actin-actin bonds when the filament is curved. Fig. 5 D shows a 1.01 μm F-ATP bending under 0.5 pN. Fig. 5, E and F, show the linear and angular strain in the bonds in the bent structure shown in Fig. 5 D. The results show that the strain in the inner strand (measured with respect to positive curvature as shown in Fig. 5 D, inset) is different than the outer strand. This result is obtained for mechanical equilibrium structures without considering fluctuations. It arises because of the helical nature of F-actin. Arp2/3 could potentially bind between actin monomers with positive strain, and therefore preferentially bind on the outer strand of positively curved filaments.

Force-induced chemical state change and mechanosensation

In earlier results, we showed that the mechanical properties of F-actin depend on the hydrolysis state of the monomers. ATP-actin, even though structurally very similar to ADP-actin, at the filament level is slightly stiffer. The consequence of such a mechanical difference is that externally applied forces can alter the chemical state of monomers in the filament. See Fig. 2 for the basic concept. If the bond energy is plotted as a function of the monomer-monomer bond length, the equilibrium length, , is then identical for the ATP-ATP bond versus ATP-ADP bond. The free energy difference of ATP-ADP bond is taken to be as higher by . (Other energy differences can be used as well, and would change the quantitative influence of force on actin chemistry.) As a force is applied and l increases away from , the difference in the curvature of the energy landscape will lead to a crossing point. At this point, the ATP-ATP bond has the same free energy as the ATP-ADP bond; therefore, the probability of converting one of the monomers to ADP is enhanced. As l increases further, the ADP-actin state becomes more favorable. Thus, the equilibrium between ATP and ADP states (actually ADP.Pi and ADP states) is influenced by forces and changes in the mechanical energy. In the Model section, we discussed a simple model to modify the rate constants while preserving detailed balance. The actual rates may differ quantitatively, but the overall effect must remain the same.

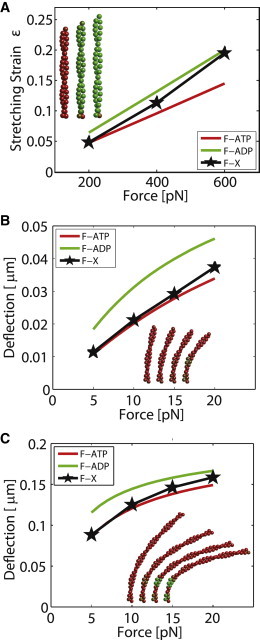

Using the Gillespie stochastic simulation algorithm, we computed ATP-actin filaments under bending forces up to 60 pN and stretching forces up to 600 pN and allowed the monomers to change their chemical state. As forces are applied, the individual monomers stochastically change their chemical state according to rate constants defined in Eq. S7 and Eq. S8. The rate constant, , has been estimated (2). Here, we report the equilibrium result as the simulation time approaches infinity. Fig. 6 A shows the average stretching strain for a 112 nm long filament under different pulling forces. As the pulling force is increased, the monomers increasingly convert to ADP. Eventually, at 600 pN, all of the monomers are essentially in ADP state. Note that our model currently does not allow the filaments to rupture. It is likely that filaments would have a high probability of breaking before the filament fully converts.

Figure 6.

Force-induced chemical state change of monomers in actin filaments. (A) Stretching-induced changes in the monomer chemical state as a function of force. The filament length is 0.11 μm. (B and C) Bending induced changes in the monomer chemical state as a function of force. In (B), the filament length is 0.9 μm and in (C) the filament length is doubled, 0.17 μm. In all figures, the average conformation of filaments that correspond to a particular force are compared with filaments with all ATP or all ADP. We see that for a longer filament, changes in chemical states are more dramatic for the same force.

Fig. 6 B shows the bending deformations while the chemical states of the monomers are changing. We see that if monomers are allowed to convert to ADP, the bending stiffness decreases as a function of applied force. This observation could potentially explain the reversible stress softening behavior of F-actin (60). Fig. 6, A and B, also show the average chemical state of the filament under force with a color code (between red and green). For the bending case, together with Fig. 3 F, we can conclude that the monomers under highest strain are closest to the left end, which is fixed (see Movie S2 in the Supporting Material). This is the reason why ADP-rich monomers tend to appear in those locations. Note that the magnitude of the bending forces can be quite low. At 20 pN, there is already a significant amount of conversion to ADP. For longer filaments (Fig. 6 C), smaller bending forces are needed to induce chemical state change because of the larger mechanical work done. For filaments under stretching forces, we observe that for large stretching forces (>400 pN), there is a fast nucleation of ADP monomers that eventually promotes the conversion of whole filament into the ADP state (Movie S1).

The results presented in Fig. 6 do depend on the choice of , the difference in bond free energies of ATP and ADP states. As an alternative, we may consider a different parameter set in Table 1 with different relative magnitudes of diagonal and longitudinal bonds. For example, a smaller would lead to increasing populations of ADP subunits as shown in Fig. S1.

Discussion and Conclusion

We have introduced a mechanochemical model of actin filaments by explicitly considering the bonding interaction between actin monomers. The filament is described as two helical strands connected by longitudinal and diagonal bonds. The chemical state of the actin monomers can change, and the rate of ATP conversion depends on the overall elastic energy of the filament. As expected, we find actin filaments are mechanically stiff under stretch, but deform easily under bending forces. The model shows that for filament length much longer than the helical actin pitch (>1 μm), the filament mechanically deforms as a semiflexible rod. However, the mechanical behavior depends on the chemical state of actin. ADP-actin filaments are softer than ATP-actin. The model is also able to capture aspects of actin accessory proteins interacting with the filament.

The model uses a coarse-grained description of actin monomer mechanics, and does not consider internal conformational complexity of actin, although it does include possible conformational changes due to ATP hydrolysis. Therefore, it is an intermediate scale model in between atomistic scale and the network scale. Internal conformational complexity can also be partially captured using nonlinear mechanical models. Here, simple harmonic spring-like functions are assumed for monomer-monomer interaction with no coupling between kinematic variables. This is the simplest model that still reproduces the essential features of actin filament mechanics. More sophisticated models can be made, but would require an increased number of parameters. Nevertheless, the model parameters can be obtained from MD simulations, or fitting to experimental data. Further studies on the model parameters would improve model predictions.

In this model, we examined a chemical state change from ATP-actin to ADP-actin. There are in fact many more possible chemical states, and this could underlie the mechanochemical complexity of actin networks. For instance, after ATP is hydrolyzed to ADP, the monomer can release inorganic phosphate and break the existing actin-actin bond, especially when the filament is under high mechanical load. This can lead to filament rupture. Actin filament rupture has been studied experimentally with single filaments (61). It was found that when the radius of curvature of the filament is <300 nm, the rupture probability increases. Furthermore, using simple force balance considerations in a nerve growth cone, a recent study (62) has estimated the forces on a steady-state actin treadmill and showed the importance of filament rupture in resistance to retrograde flow. The framework used in this work can be extended to describe such situations.

By understanding the full range of mechanochemical behavior of actin, improved models of the role of actin in the cell can be made. For instance, to understand cortical actin network contraction and stress-induced softening seen in experiments, chemical state changes and turnover of actin monomers in response to forces must be examined. To our knowledge, our model is the first such model in this direction. Extrapolating to the network scale, these mechanochemical effects will significantly influence the viscoelasticity of the network. Combined with nucleation, growth, contraction, and turnover of the network, a quantitative model of the cellular cytoplasm can be developed. Note that these mechanochemical effects may lead to unique network properties that are not present in static polymer networks where bonds between monomers are essentially permanent. Therefore, new physics may be present and could lead to surprising mechanistic insights for the cell.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported in part by National Science Foundation CHE0514749 and National Institutes of Health GM075305.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Pollard T.D., Borisy G.G. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujiwara I., Vavylonis D., Pollard T.D. Polymerization kinetics of ADP- and ADP-Pi-actin determined by fluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8827–8832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702510104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sept D., Xu J., McCammon J.A. Annealing accounts for the length of actin filaments formed by spontaneous polymerization. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2911–2919. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)77124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isambert H., Venier P., Carlier M.F. Flexibility of actin filaments derived from thermal fluctuations. Effect of bound nucleotide, phalloidin, and muscle regulatory proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:11437–11444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brangwynne C.P., Koenderink G.H., Weitz D.A. Bending dynamics of fluctuating biopolymers probed by automated high-resolution filament tracking. Biophys. J. 2007;93:346–359. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.096966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ott A., Magnasco M., Libchaber A. Measurement of the persistence length of polymerized actin using fluorescence microscopy. Phys. Rev. E. 1993;48:R1642–R1645. doi: 10.1103/physreve.48.r1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardel M.L., Shin J.H., Weitz D.A. Elastic behavior of cross-linked and bundled actin networks. Science. 2004;304:1301–1305. doi: 10.1126/science.1095087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peskin C.S., Odell G.M., Oster G.F. Cellular motions and thermal fluctuations: the Brownian ratchet. Biophys. J. 1993;65:316–324. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81035-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mogilner A., Oster G. Cell motility driven by actin polymerization. Biophys. J. 1996;71:3030–3045. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79496-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao W., Goodarzi J.P., De La Cruz E.M. Energetics and kinetics of cooperative cofilin-actin filament interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;361:257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCullough B.R., Blanchoin L., De la Cruz E.M. Cofilin increases the bending flexibility of actin filaments: implications for severing and cell mechanics. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;381:550–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollard T.D., Blanchoin L., Mullins R.D. Molecular mechanisms controlling actin filament dynamics in nonmuscle cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000;29:545–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmoller K.M., Niedermayer T., Bausch A.R. Fragmentation is crucial for the steady-state dynamics of actin filaments. Biophys. J. 2011;101:803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J., Sun Y., Drubin D.G. Mechanochemical crosstalk during endocytic vesicle formation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skau C.T., Kovar D.R. Fimbrin and tropomyosin competition regulates endocytosis and cytokinesis kinetics in fission yeast. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1415–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pelham R.J., Chang F. Actin dynamics in the contractile ring during cytokinesis in fission yeast. Nature. 2002;419:82–86. doi: 10.1038/nature00999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mogilner A., Oster G. Polymer motors: pushing out the front and pulling up the back. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:R721–R733. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fournier M.F., Sauser R., Verkhovsky A.B. Force transmission in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:287–297. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walcott S., Sun S.X. A mechanical model of actin stress fiber formation and substrate elasticity sensing in adherent cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7757–7762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912739107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galkin V.E., Orlova A., Egelman E.H. Actin filaments as tension sensors. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:R96–R101. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erickson H.P. Co-operativity in protein-protein association. The structure and stability of the actin filament. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;206:465–474. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90494-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooke R. The role of the bound nucleotide in the polymerization of actin. Biochemistry. 1975;14:3250–3256. doi: 10.1021/bi00685a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Splettstoesser T., Holmes K.C., Smith J.C. Structural modeling and molecular dynamics simulation of the actin filament. Proteins. 2011;79:2033–2043. doi: 10.1002/prot.23017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oda T., Iwasa M., Narita A. The nature of the globular- to fibrous-actin transition. Nature. 2009;457:441–445. doi: 10.1038/nature07685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujii T., Iwane A.H., Namba K. Direct visualization of secondary structures of F-actin by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 2010;467:724–728. doi: 10.1038/nature09372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galkin V.E., Orlova A., Egelman E.H. Structural polymorphism in F-actin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:1318–1323. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirata H., Tatsumi H., Sokabe M. Dynamics of actin filaments during tension-dependent formation of actin bundles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1770:1115–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greene G.W., Anderson T.H., Israelachvili J.N. Force amplification response of actin filaments under confined compression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:445–449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812064106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuda Y., Yasutake H., Yanagida T. Torsional rigidity of single actin filaments and actin-actin bond breaking force under torsion measured directly by in vitro micromanipulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12937–12942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu J.W., Voth G.A. Coarse-grained modeling of the actin filament derived from atomistic-scale simulations. Biophys. J. 2006;90:1572–1582. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfaendtner J., Lyman E., Voth G.A. Structure and dynamics of the actin filament. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;396:252–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kojima H., Ishijima A., Yanagida T. Direct measurement of stiffness of single actin filaments with and without tropomyosin by in vitro nanomanipulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:12962–12966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janmey P.A., Hvidt S., Hartwig J.H. Effect of ATP on actin filament stiffness. Nature. 1990;347:95–99. doi: 10.1038/347095a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J.Y., Iverson T.M., Dima R.I. Molecular investigations into the mechanics of actin in different nucleotide states. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:186–195. doi: 10.1021/jp108249g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chu J.W., Voth G.A. Allostery of actin filaments: molecular dynamics simulations and coarse-grained analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13111–13116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503732102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De La Cruz E.M., Roland J., Martiel J.L. Origin of twist-bend coupling in actin filaments. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1852–1860. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svitkina T.M., Borisy G.G. Arp2/3 complex and actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin in dendritic organization and treadmilling of actin filament array in lamellipodia. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:1009–1026. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollard T.D., Cooper J.A. Actin and actin-binding proteins. A critical evaluation of mechanisms and functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1986;55:987–1035. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGough A., Pope B., Weeds A. Cofilin changes the twist of F-actin: implications for actin filament dynamics and cellular function. J. Cell Biol. 1997;138:771–781. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.4.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfaendtner J., De La Cruz E.M., Voth G.A. Actin filament remodeling by actin depolymerization factor/cofilin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7299–7304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911675107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suarez C., Roland J., Blanchoin L. Cofilin tunes the nucleotide state of actin filaments and severs at bare and decorated segment boundaries. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De La Cruz E.M. How cofilin severs an actin filament. Biophys Rev. 2009;1:51–59. doi: 10.1007/s12551-009-0008-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goley E.D., Welch M.D. The ARP2/3 complex: an actin nucleator comes of age. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:713–726. doi: 10.1038/nrm2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Risca V.I., Wang E.B., Fletcher D.A. Actin filament curvature biases branching direction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:2913–2918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114292109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atilgan E., Wirtz D., Sun S.X. Mechanics and dynamics of actin-driven thin membrane protrusions. Biophys. J. 2006;90:65–76. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Atilgan E., Wirtz D., Sun S.X. Morphology of the lamellipodium and organization of actin filaments at the leading edge of crawling cells. Biophys. J. 2005;89:3589–3602. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.065383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halavatyi A.A., Nazarov P.V., Friederich E. An integrative simulation model linking major biochemical reactions of actin-polymerization to structural properties of actin filaments. Biophys. Chem. 2009;140:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berro J., Sirotkin V., Pollard T.D. Mathematical modeling of endocytic actin patch kinetics in fission yeast: disassembly requires release of actin filament fragments. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:2905–2915. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vavylonis D., Yang Q., O’Shaughnessy B. Actin polymerization kinetics, cap structure, and fluctuations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8543–8548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501435102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deriu M.A., Shkurti A., Acquaviva A. Multiscale modelling of cellular actin filaments: from atomistic molecular to coarse grained dynamics. Proteins. 2012;80:1598–1609. doi: 10.1002/prot.24053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sinitskiy A.V., Saunders M.G., Voth G.A. Optimal number of coarse-grained sites in different components of large biomolecular complexes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:8363–8374. doi: 10.1021/jp2108895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ming D., Kong Y., Ma J. Simulation of F-actin filaments of several microns. Biophys. J. 2003;85:27–35. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74451-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berro J., Michelot A., Martiel J.L. Attachment conditions control actin filament buckling and the production of forces. Biophys. J. 2007;92:2546–2558. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.094672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCullough B.R., Grintsevich E.E., De La Cruz E.M. Cofilin-linked changes in actin filament flexibility promote severing. Biophys. J. 2011;101:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Asakura S., Taniguchi M., Oosawa F. Mechano-chemical behavior of F-actin. J. Mol. Biol. 1963;7:55–69. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Howard J. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2001. Mechanics of Motor Proteins and the Cytoskeleton. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yogurtcu O.N., Wolgemuth C.W., Sun S.X. Mechanical response and conformational amplification in α-helical coiled coils. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3895–3904. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmid M.F., Sherman M.B., Chiu W. Structure of the acrosomal bundle. Nature. 2004;431:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature02881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galkin V.E., Orlova A., Egelman E.H. Actin depolymerizing factor stabilizes an existing state of F-actin and can change the tilt of F-actin subunits. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:75–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chaudhuri O., Parekh S.H., Fletcher D.A. Reversible stress softening of actin networks. Nature. 2007;445:295–298. doi: 10.1038/nature05459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arai Y., Yasuda R., Itoh H. Tying a molecular knot with optical tweezers. Nature. 1999;399:446–448. doi: 10.1038/20894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Craig E.M., Van Goor D., Mogilner A. Membrane tension, myosin force, and actin turnover maintain actin treadmill in the nerve growth cone. Biophys. J. 2012;102:1503–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.