Abstract

The galactolipids monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) constitute the major glycolipids of the thylakoid membranes in chloroplasts. In Arabidopsis, the formation of MGDG is catalyzed by a family of three MGDG synthases, which are encoded by two types of genes, namely type A (atMGD1) and type B (atMGD2 and atMGD3). Although the roles of the type A enzyme have been intensively investigated in several plants, little is known about the contribution of type B enzymes to MGDG synthesis in planta. From our previous analyses, unique expression profiles of the three MGDG synthase genes were revealed in various organs and developmental stages. To characterize the expression profiles in more detail, we performed histochemical analysis of these genes using β-glucuronidase (GUS) assays in Arabidopsis. The expression of atMGD1::GUS was detected highly in all green tissues, whereas the expression of atMGD2::GUS and atMGD3::GUS was observed only in restricted parts, such as leaf tips. In addition, intense staining was detected in pollen grains of all transformants. We also detected GUS activity in the pollen tubes of atMGD2::GUS and atMGD3::GUS transformants grown in wild-type stigmas but not in atMGD1::GUS, suggesting that type B MGDG synthases may have roles during pollen germination and pollen tube growth. GUS analysis also revealed that expression of atMGD2 and atMGD3, but not atMGD1, are strongly induced during phosphate starvation, particularly in roots. Because only DGDG accumulates in roots during phosphate deprivation, type B MGDG synthases may be acting primarily to supply MGDG as a precursor for DGDG synthesis.

Galactolipids are major constituents of the photosynthetic membranes in oxygenic photosynthetic organisms, including cyanobacteria, red and green algae, and higher plants. The simplest of these lipids, monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG), constitutes up to 50% of thylakoid membrane lipids in chloroplasts and together with the other major galactolipid, digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), represents the bulk of photosynthetic membranes (80 mol % of total glycerolipids; Joyard et al., 1996). Recent x-ray crystallographic analysis of PSI revealed that MGDG is tightly bound to the reaction center (Jordan et al., 2001); therefore, MGDG might be required not only as a bulk constituent of photosynthetic membranes but also for the photosynthetic reaction itself. In addition, galactolipids make up 60% of the total membrane lipids even in plastids of non-photosynthetic tissues (Alban et al., 1988); however, their roles in these tissues are not well investigated.

MGDG biosynthesis occurs in the plastid envelope and is catalyzed by MGDG synthase, which transfers d-Gal from UDP-Gal to sn-1,2-diacylglycerol (Shimojima et al., 1997). DGDG is synthesized by galactosylation of MGDG; therefore, MGDG synthase is the key enzyme for the biosynthesis of galactolipids and, hence, construction of the plastid membranes. We have cloned three MGDG synthase genes from Arabidopsis and designated these genes as atMGD1, atMGD2, and atMGD3 (Miège et al., 1999; Awai et al., 2001). Based on amino acid identity and subcellular localization of the enzymes, these genes were classified into type A (atMGD1) and type B (atMGD2 and atMGD3), whose gene products are thought to be located in inner and outer envelope membranes of chloroplasts. Gene expression analysis in major plant organs revealed that the type B MGDG synthase genes atMGD2 and atMGD3 were expressed specifically in flowers and roots, respectively, whereas strong expression of the type A gene (atMGD1) was observed in all organs analyzed. During the development of Arabidopsis, the high-level expression of atMGD1 was detected constantly, but atMGD2 showed no significant expression. On the other hand, atMGD3 showed intense expression in the early stages of growth, but as the plant grew, the expression decreased to undetectable levels (Awai et al., 2001). A T-DNA mutant deficient in the expression of atMGD1 has been reported, and this mutant exhibits a pale-green phenotype (Jarvis et al., 2000). The mutant has abnormal chloroplasts with a major deficiency in galactolipid synthesis, suggesting that the type A MGDG synthase is responsible for the bulk of MGDG synthesis during chloroplast development (Jarvis et al., 2000; Awai et al., 2001).

To investigate the localization of expression of these three MGDG synthase genes in greater detail, we constructed promoter::GUS fusions for these genes and introduced these constructs into plants. Here, we report histochemical analyses of these transformants in several organs, growth conditions, and developmental stages. Together with the analysis of reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and galactolipid synthesis activity, we propose possible functions for the type B MGDG synthases, which might have unknown roles, particularly in non-photosynthetic organs such as flowers and roots.

RESULTS

Expression of Three atMGD Genes in Plant Development

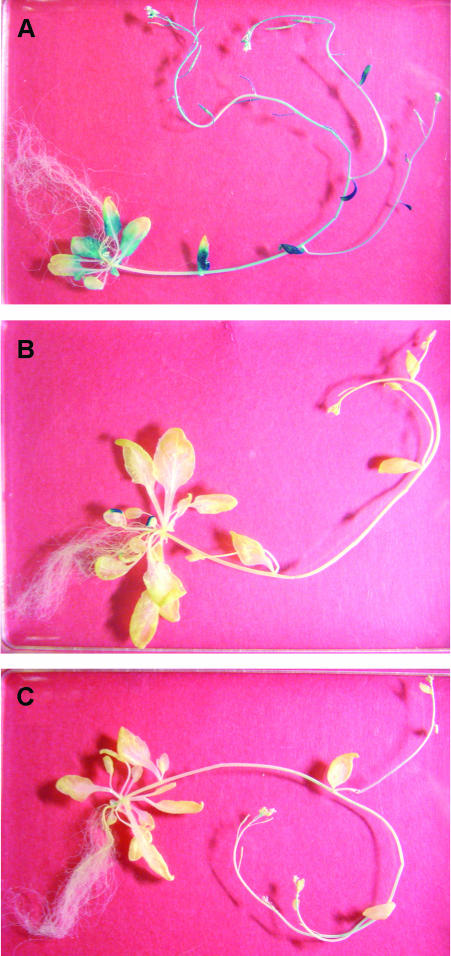

The presumed promoter region of approximately 1,400 bp upstream from the transcription start site was used to construct β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene fusions for stable transformants of the three MGDG synthase genes (Fig. 1). In 40-d-old whole adult plants, GUS staining of the atMGD1 transformant was mostly observed in photosynthetic green tissues, such as rosette leaves, cauline leaves, stems, and sepals (Fig. 2). Based on substrate specificity, localization, abundance of the enzyme among isozymes (Awai et al., 2001), and analysis of a T-DNA-tagged mutant (Jarvis et al., 2000), it is considered that type A MGDG synthase (atMGD1) is involved in bulk synthesis of MGDG for photosynthetic membranes (Jarvis et al., 2000; Awai et al., 2001). The staining in Figure 2A for atMGD1 clearly agreed with this idea because MGDG is particularly important during the development of photosynthetic membranes in green tissues. On the other hand, in the atMGD2 and atMGD3 transformants, GUS activity was detected only in tips of the leaves and flowers. Furthermore, the blue staining was also observed in anthers in all transformants (see below).

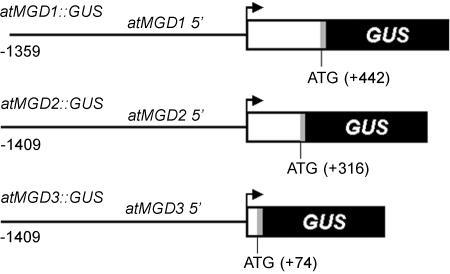

Figure 1.

Structure of atMGD promoters::GUS fusion genes. Lines and open boxes indicate 5′-upstream regions and untranslated regions (UTRs) of each gene, respectively. Gray boxes show the regions of first three amino acids derived from each MGD gene. GUS coding regions are depicted in black. The nucleotides in the promoter regions are numbered beginning with the transcriptional start points indicated by each allow. The numbers added in regions indicate the translational start points of each MGD gene.

Figure 2.

Histochemical analysis of atMGD::GUS expression in mature plants. Whole GUS staining of transgenic plants carrying atMGD1::GUS (A), atMGD2::GUS (B), and atMGD3::GUS (C). Each transgenic plant was grown on Murashige and Skoog medium for 40 d.

Analysis of GUS activity was also performed during vegetative growth (Fig. 3). In the early stages of seedling development (within 5 d after sowing), atMGD1::GUS transformants showed intense GUS staining only in the cotyledons but not in hypocotyls and roots. In the 10-d-old plants, strong GUS expression was detected throughout all of the cotyledons and rosette leaves without detectable staining in remaining regions. Fifteen-day-old plants also showed the same staining pattern as 10-d-old plants. In 20-d-old plants, however, weak staining was detected in petioles, roots, and leaves. Constitutive but low staining was also observed in the atMGD2::GUS transformant throughout development. In the early stages of atMGD2::GUS transformants, staining was scarcely detected. After 10 d, GUS staining was observed around the tips of cotyledons or rosette leaves, and it remained until d 20.

Figure 3.

GUS activity in atMGD::GUS transformants detected during development. Each transformant was grown for several days as described and then used for GUS assay.

In contrast, in atMGD3::GUS transformants, strong GUS activity was detected in cotyledons of 3-d-old seedling similar to the atMGD1::GUS transformant. Although staining in the cotyledons was constitutive in the atMGD1::GUS transformant, it began to decrease in 5-d-old atMGD3::GUS transformants. As shown in Figure 3, GUS staining was observed at the edge of cotyledons. In young seedlings, GUS activity was also evident at the stem apex. In the older seedlings, i.e. 10 and 15 d old, there was GUS staining only in the tips of leaves like atMGD2::GUS transformants. In 20-d-old plants, staining was observed in the tips of rosette leaves and cotyledons. In addition to the leaves, weak staining was detected in the roots of 20-d-old plants. These results are basically consistent with the result from RT-PCR analysis (Awai et al., 2001) indicating that the regulation of the three MGDG synthase genes in plant development was basically the same in both transcriptional and translational levels because all transformants used here were made by translational GUS-fusion constructs (Fig. 1).

Type B MGDG Synthases Are Expressed during Pollen Germination

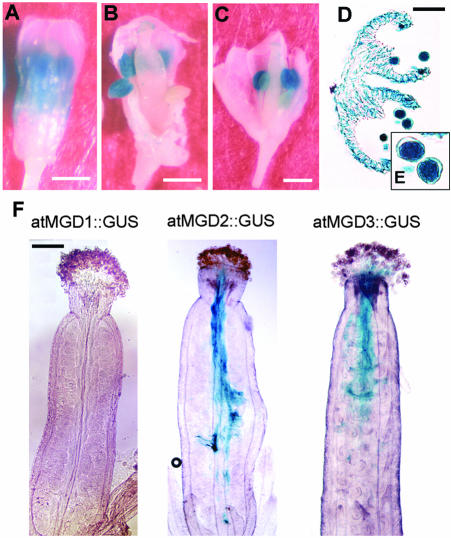

To investigate the expression of atMGD genes in floral organs in more detail, we carried out the GUS assay by using flowers of each transformant (Fig. 4, A–E). In the atMGD1::GUS transformants, intense staining was observed in anthers, in addition to green organs of flowers such as sepals and a part of immature petals. In the flowers of the transformants carrying atMGD2 or atMGD3::GUS fusions, GUS activity was detected specifically in anthers without detectable staining in remaining regions. Staining was not detected in young anthers but became more intense as buds developed (data not shown). When we observed thin sections of these anthers under the microscope, pollen grains were strongly stained (Fig. 4, D and E). These results indicated that in Arabidopsis, the expression of MGDG synthases was induced during pollen development. We wondered whether this expression profile was also associated with pollen germination and/or growth of pollen tubes. To clarify the expression pattern of MGDG synthase genes during pollen germination, pollen from each GUS transformant was cross-pollinated to wild-type stigmas, and GUS staining was performed. As shown in Figure 4F, the pistils pollinated with type B MGDG synthase::GUS transformants showed blue staining in pollen tubes, but those receiving pollen from the type A transformant did not. This result clearly indicated that only type B promoters are active after pollination and during growth of the pollen tube.

Figure 4.

GUS expression driven by each atMGD promoter in floral tissues. A to C, Flowers of atMGD1::GUS, atMGD2::GUS, and atMGD3::GUS transformants, respectively. Scale bars = 500 μm. D, Thin section of stained anther from atMGD2::GUS transformant. Scale bar = 50 μm. E, Magnified images of D, focusing on pollen grains. F, GUS staining observed in wild-type pistils. This GUS activity was derived from pollen of each atMGD::GUS transformant. Scale bars = 300 μm.

Expression of Type B MGD Enzymes under Phosphate (Pi) Deprivation

In a previous paper, RT-PCR analysis revealed that the expression of type B MGDG synthase genes was induced intensely under Pi-deprived conditions (Awai et al., 2001). To examine the spatial expression of MGDG synthases under these conditions, the GUS transformants were analyzed after Pi deprivation (Fig. 5). In atMGD1::GUS transformants, no difference in the staining pattern between Pi-deprived and -replete conditions was observed, similar to the results of RT-PCR analysis. In contrast, atMGD2::GUS and atMGD3::GUS transformants were stained intensely, especially in roots, under Pi-deprived conditions. The staining was also observed in some leaves and shoot apex and was obviously different from that detected under Pi-replete conditions in Figure 3. In our previous report, we used only the aerial portion of the plants for RT-PCR analysis in Pi starvation experiments. To confirm whether the expression level of type B genes under Pi starvation was different between shoots and roots, we carried out northern hybridization for the both tissues of Pi-deprived Arabidopsis. However, no remarkable difference between the two samples was observed (data not shown). When we measured in vitro GUS activity in atMGD2::GUS and atMGD3::GUS transformants, higher activity was observed in the root than in the shoot of each transformant. These results suggest that there is posttranscriptional regulation in the translation of type B MGDG synthases because we constructed the reporter genes as translational fusions. We also examined GUS activity of each transformant under sulfate-deprived conditions and found that none of the three promoter::GUS fusion genes were induced by sulfate starvation (data not shown). This result demonstrates that the strong expression of the type B enzymes induced by Pi deprivation is not a common phenomenon in Pi and sulfate deficient condition, but is specific to Pi starvation.

Figure 5.

Expression of each atMGD::GUS gene in response to Pi-deprived conditions. Each transgenic plant was grown in Murashige and Skoog media for 10 d and then transferred to Pi-sufficient (Pi+; 10 mm) or depleted (Pi–; 0 mm) media for 10 d.

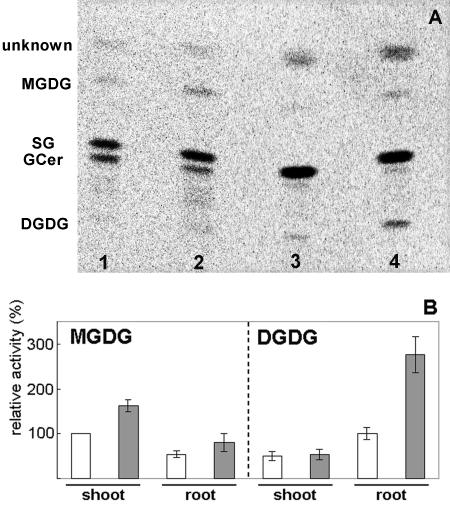

A previous report (Härtel and Benning, 2000) showed only a slight increase of MGDG accumulation in both shoots and roots under Pi starvation but a high accumulation of DGDG in roots. To confirm whether the Pi-limited growth condition triggered the increase of MGDG synthase activity, we measured the galactolipid synthetic activity of both shoots and roots from Pi-deprived Arabidopsis (Fig. 6). In both the shoot and the root, incorporation of Gal into MGDG increased over 150% under Pi-deprived conditions compared with Pi-replete conditions. This result showed that MGDG synthesis was activated by Pi-limited growth in parallel with the accumulation of type B mRNAs. Moreover, incorporation of Gal into DGDG in the Pi-starved root was increased approximately 280% compared with the Pi-sufficient root. This result was consistent with the evidence that, in the roots, DGDG accumulates greatly under Pi starvation (Härtel and Benning, 2000). The increase in radioactive MGDG induced by Pi deprivation in the root seemed to be lower than what would be expected from the GUS activity observed in the roots of Pi-starved type B::GUS transformants. However, because the MGDG produced could be channeled into DGDG synthesis, the overall flux through MGDG in the roots of Pi-starved plants is probably much higher than the apparent incorporation of Gal into MGDG as the end product of the pathway.

Figure 6.

Galactosyltransferase activity in response to Pi starvation. Enzymatic reaction was performed using radiolabeled UDP-Gal as a substrate in crude extracts from several samples. A, Radioactivity incorporated into lipids was visualized by Image Analyzer (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ). Lanes 1 to 4, Enzymatic activity in the shoot of Pi-replete plants, the shoot of Pi-depleted plants, the root of Pi-replete plants, and the root of Pi-depleted plants, respectively. SG, Sterylglycoside, Gcer, glycosylceramide. B, Relative values of radioactivity incorporated into galactolipids. White bars indicate the activity detected in Pi-replete plants. Gray bars indicate the activity measured in Pi-depleted plants. Radioactivity of MGDG in the shoot of Pi-replete plants corresponds to 100%. Presented values are means from five independent measurements (±se).

Type A MGDG Synthase Contributes to the Construction of Membranes in Both Chloroplasts and Etioplasts

As indicated above, types A and B MGDG synthases were associated with distinct physiological events in plants. To clarify how the expression of these genes was regulated, we analyzed the effects of phytohormones, i.e. GA, auxin, ethylene, abscisic acid, cytokinin, methyl jasmonate, and salicylic acid on 10-d-old seedlings by RT-PCR. There was, however, no significant change on the gene expression by these treatments (data not shown).

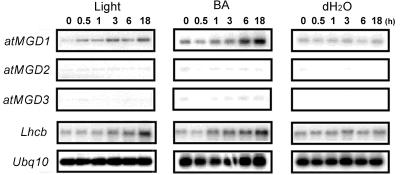

We also analyzed the effects of illumination and cytokinin on the expression of MGDG genes to etiolated seedlings because the expression of a cucumber (Cucumis sativus) MGD gene was induced by these treatments in the etiolated seedlings (Yamaryo et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 7, atMGD1 expression was induced significantly by both treatments. This result supports the assertion that atMGD1 is the enzyme responsible for bulk synthesis of MGDG, similar to cucumber MGD1 (Yamaryo et al., 2003), because these treatments induce development of the thylakoid membrane (Chory et al., 1994). Furthermore, we also detected weak expression of atMGD1 in etiolated seedlings (see 0 h of treatment and/or negative control), whereas there is no expression of type B MGD genes. To confirm this result, GUS activity was also analyzed in the etiolated seedlings of each transformant, but only atMGD1::GUS transformants showed GUS staining in the etiolated cotyledons (data not shown). These results indicate that atMGD1 contributes to the development of not only thylakoid membranes in chloroplasts, but also prolamellar bodies in etioplasts, which are mainly composed of galactolipids and NADPH-protochlorophyllide-protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase complexes (Selstam and Sandelius, 1984).

Figure 7.

RT-PCR analysis of Arabidopsis MGD genes in response to light and benzyladenine. Plants were grown for 5 d in darkness before light or benzyladenine treatments. Times for treatments of light or benzyladenine were described in figure. Lhcb, Light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein of PSII. Ubq10, Ubiquitin 10.

DISCUSSION

Posttranscriptional Regulation on Expression of MGD Genes

In this paper, we present histochemical analyses of Arabidopsis MGDG synthases during plant development and Pi deprivation by using translational fusions to the GUS gene. In atMGD1 and atMGD2, there are 442 and 316 bp of 5′-UTR between the transcription and translation start sites, respectively. In this region, six (atMGD1) and one (atMGD2) ATG start codons were found upstream of the expected start codons. We observed, however, that GUS staining detected in this report agreed well with the results of RT-PCR analysis (Awai et al., 2001). Thus, these genes are translated from the seventh and second ATG codons, respectively. These results strongly support the idea that there are polypyrimidine tracts in the 5′-UTRs of both genes that might regulate the translation of the respective mRNA (Awai et al., 2001).

Beside these cis-elements, there is additional posttranscriptional regulation of type B MGDG synthases during Pi-deprived conditions. We reported previously that in the aerial parts of Arabidopsis, the mRNAs of the type B synthases were highly accumulated under Pi-deprived conditions. GUS activity was, however, mainly detected in the roots as shown in Figure 5. This result suggests that some factor(s) activates the translation of type B synthases in the root under Pi-limiting conditions because no difference was found in the accumulation of these mRNAs between shoots and roots (data not shown). In Pi-limiting conditions, DGDG synthases (DGD1 and DGD2) and a SQDG synthase (SQD2) have been shown to be up-regulated at the level of mRNA like type B MGDG synthases in Arabidopsis (Kelly and Dörmann, 2002; Yu et al., 2002; Kelly et al., 2003). In addition, mRNA induction of SQD1 that catalyzes the synthesis of UDP-sulfoquinovose also has been shown (Essigmann et al., 1998). Such induction by Pi starvation of these genes for glycolipid synthesis may be regulated by the same mechanism under Pi-limiting conditions. However, comparing the sequences of the 5′-upstream regions of these genes with available databases, we could not find any consensus sequences for either transcriptional or posttranscriptional regulation. Thus, it is still unknown which factor(s) regulates their transcription and translation in Pi-limiting conditions. There is no induction of the gene expression by plant hormone treatments. The GUS transformants presented in this study may prove to be powerful tools to analyze the regulation of plastidic glycolipid synthesis under these conditions.

Galactolipid Synthesis during Developmental Stages of Etioplasts and Chloroplasts

MGDG is a major constituent of the thylakoid membrane, the site of electron transfer in photosynthesis. In this report, we showed the intense GUS staining of atMGD1::GUS transformants in all green tissues and the accumulation of atMGD1 mRNA by treatment with light and cytokinin in etiolated seedlings. We also observed atMGD1::GUS activity and gene expression of atMGD1 even in etiolated seedlings. These tissues and organs have developing chloroplasts and etioplasts, both of which contain intramembrane structures related to thylakoids. Thus, we postulate that atMGD1 is the major contributor to the construction of intra-organellar membrane structures in plastids, such as the thylakoid membranes and prolamellar bodies.

Jarvis et al. (2000) speculated that atMGD1 did not have a main role in construction of etioplasts because prolamellar bodies showed no significant defect in the mgd1 mutant. In our study, only the transformants carrying atMGD1::GUS showed GUS activity during etiolated growth, which suggested that at-MGD1 was the primary MGDG synthase responsible for formation of prolamellar bodies, in addition to thylakoid membranes. The mgd1 mutant in the previous study still showed MGDG synthase activity, although the activity was 30% of wild type. Moreover, it is a mutant in which the T-DNA was inserted in the 5′-non-coding region. It is possible that the atMGD1 activity remaining in the mutant is enough for the construction of prolamellar bodies in Arabidopsis. Besides the importance of atMGD1 in formation of both etioplasts and chloroplasts, it should be noted that in illuminated young seedlings, atMGD3 probably also contributes to MGDG synthesis (Fig. 3), as was suggested in a previous report (Awai et al., 2001).

Galactolipid Synthesis under Pi Deprivation

As described above, type B MGDG synthases and DGDG synthases are induced by Pi deprivation in Arabidopsis. These enzymes are localized to the outer envelope membranes of chloroplasts (Awai et al., 2001; Froehlich et al., 2001) and might contribute to galactolipid synthesis simultaneously at least in that condition. As shown in Figure 5, we detected strong GUS activity in the roots of typeB::GUS transformants. The strong induction of MGDG and particularly DGDG synthesizing activities also was observed. These results agreed well with the report that DGDG is accumulated in roots during Pi starvation (Härtel et al., 2000). They also reported that the over-accumulated DGDG was localized in extra-plastidic membranes. In addition, accumulation of DGDG has been observed in the plasma membranes of Pi-deprived oats (Avena sativa; Andersson et al., 2003). Thus, type B MGDG synthases probably contribute to the accumulation of DGDG in extra-plastidic membranes under Pi-deprived conditions. In this context, it should be noted that DGDG synthases are also known to be present in outer envelope membrane. Colocalization of DGDG synthase with type B MGDG synthase may be important for cooperation of these enzymes to efficiently produce large amount of DGDG under specific conditions.

Galactolipid Synthesis in Pollen Germination

We observed that all atMGD genes were expressed in pollen. This finding is in accord with the fact that large amounts of galactolipids are found in the pollen coat (Evans et al., 1990) and that these lipids are considered to localize in amyloplasts, which accumulate starches (Singh et al., 1991). In Arabidopsis, the plastids observed in early microspores released from tetrads have no inner membrane system. However, inner membranes begin to appear with the maturation of microspores, and a large amount of starch grains accumulate in plastids by the time of uninucleate microspore formation (Kuang and Musgrave, 1996). During the maturation of microspores, the expression of Arabidopsis MGDG synthases detected in anthers seemed to occur simultaneously with the construction of inner membranes of amyloplasts; therefore, it is likely that these enzymes contribute to the construction of the inner membrane systems and accumulation of starch grains in pollen.

In contrast to the profile during the maturation of microspores, only the expression of type B MGDG synthases was observed during germination of pollen tubes. Until now, there has been no report that indicates the importance of galactolipids in floral organs, particularly in pollen tube growth; thus, their subcellular localization and roles in pollen germination are quite unclear. It is known that the starch grains in plastids are decreased as pollen matures, and, synchronized with that, lipid bodies accumulate in pollen grains (Kuang and Musgrave, 1996). The accumulation of polar lipids and triacylglycerols was also observed during pollen maturation in Brassica napus (Piffanelli et al., 1997). In olive (Olea europaea) pollen, lipid bodies were localized near the germinative aperture of pollen grains, moved to pollen tubes as pollen was germinated, and then decreased as the pollen tubes grew (Rodríguez-García et al., 2003). These phenomena suggest that the lipid bodies provide the energy and/or materials for pollen tube growth. Because a large amount of lipid is required to form a long pollen tube, lipids in lipid bodies may be used for galactolipid synthesis during membrane construction of pollen tubes.

The present study clearly indicated that expression of genes for galactolipid synthesis is strongly activated during pollen development and germination, suggesting their importance in these steps. As mentioned above, the type B MGDG synthases probably contribute to the synthesis of extra-plastidic galactolipids that are accumulated in the plasma membrane under Pi deprivation. For pollen tube growth, de novo lipid synthesis is required for the construction of membrane structures, whereas in vitro germination of pollen could be observed in Pi-less media (Fan et al., 2001). It is possible that type B MGDG synthases are involved in the construction of extraplastidic membrane structures, like the plasma membrane of pollen tubes, by supplying MGDG as a substrate for DGDG synthesis, as they do under Pi-deprived conditions. Recently, we found that DGDG is a major glycolipid in floral organs of petunia (Petunia hydrida; Nakamura et al., 2003). Moreover, stigma has the strongest galactolipid synthesizing activity in the floral organs. Type B MGDG synthases may be involved in the production of the large amount of DGDG found in such floral organs.

Distribution of Type B MGDG Synthases

Type B MGDG synthases are identified not only in Arabidopsis but also in other dicotyledonous plants, including Lotus japonicus and soybean (Glycine max), and the monocotyledonous plant maize (Zea mays; Awai et al., 2001). The expression level of these enzymes is very low in greening tissues, at least in Arabidopsis. However, the present evidence indicates the conditional importance of the type B enzymes for plants. In this report, we showed that specific expression of type B isoforms occurred in pollen tubes and under Pi-deprived conditions. It should be pointed out that in the mgd1 mutant (Jarvis et al., 2000), apparent DGDG synthase activity was not altered, and no phenotypical changes in floral organs were found, suggesting that atMGD1 is of less importance in both DGDG synthesis and flower development.

A role of the type B MGDG synthases in Pi-replete photosynthetic tissues remains to be revealed. However, we showed broad expression of atMGD3 in young cotyledons, suggesting the importance of this type of enzyme in the early developmental stages of the photosynthetic tissues. As already mentioned, both type B MGDG synthases (MGD2 and MGD3) and DGDG synthases (DGD1 and DGD2) colocalize in outer envelope membranes of chloroplasts, whereas atMGD1 is present in inner envelope membranes. Although transcript levels of type B MGD genes are quite low in photosynthetic tissues under Pi-replete conditions, type B enzymes may also contribute to DGDG synthesis in chloroplasts of the green tissues to some extent, in addition to non-photosynthetic tissues such as Pi-starved roots.

Our results indicate a functional sharing among MGDG synthases, which may be necessary optimal growth and development. Further studies, such as mutant analysis, are needed to clarify the function of type B MGDG synthases and the potential for functional redundancy among MGDG synthases, providing us new insight to understand the roles of galactolipids in higher plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Condition

Arabidopsis (Columbia) was grown on Murashige and Skoog media (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) containing 1% (w/v) Suc or on soil at 23°C in continuous white light. All transformants described here were produced by modified versions of the vacuum-infiltration method (Bechtold et al., 1993; Bechtold and Pelletier, 1998) and selected on Murashige and Skoog media containing 50 μg mL–1 kanamycin. For Pi-limiting experiments, plants were grown for 10 d on Murashige and Skoog media and then transferred to Pi-replete media (10 mm Pi) or depleted media (0 mm Pi) prepared as described by Härtel et al. (2000) for another 10 d. For the analysis of the effect of light and cytokinin on etiolated seedlings, about 40 μL of sterilized seeds was sown in flasks with 30 mL of liquid Murashige and Skoog media. Then, each flask was wrapped with aluminum foil, placed into light-proof boxes, and incubated on the rotary shaker in darkness at 22°C after 3 h of light exposure. Five-day-old seedlings were applied to the treatments. For cytokinin treatment, benzyladenine was added to the flask to a final concentration of 10 μm.

Construction of GUS Fusion Vectors

The 5′-upstream region of atMGD1, which was amplified by PCR between –1,359 to +442 bp from the transcription initiation site, was translationally ligated into a GUS gene in the BamHI site of a pBI101 vector. By the same way, a 5′-upstream region of atMGD2 (from –1,409 to +316 bp), and atMGD3 (from –1,409 to +74 bp) were inserted into HindIII/BamHI sites and SalI site of pBI101, respectively. These fragments included the regions coding for the first three amino acids of each MGD gene. All PCR fragments described here were sequenced and checked for PCR errors.

GUS Assay

Histochemical analyses for GUS expression were carried out in six independent transgenic lines for each construct. Plant samples were soaked at 37°C for 1 d in the GUS assay solution, which included 1 mm 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylglucronide, 0.5 mm K3Fe(CN)6, 0.5 mm K4Fe(CN)6, 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100, 20% (v/v) methanol, and 50 mm Pi-buffered saline. Then the samples were soaked in 70% (w/v) ethanol for 1 d to stop reaction and remove chlorophyll.

Preparation for Thin Sections

Floral samples used for GUS assay were subjected to vacuum infiltration for 15 min in 20 volumes of formaldehyde/glacial acetic acid/70% (w/v) ethanol (1:1:18 [v/v]) and fixed for 1 h at room temperature. Fixed samples were then dehydrated in a sequential deionized water/ethanol/n-butanol series (3 h each at 50:40:10, 30:50:20, 15:50:35, 1:49:50, 0:25:75, 0:0:100, and 0:0:100 [v/v]). Then, the samples were infiltrated in dissolved paraffin (Paraplast Plus, Oxford, St. Louis) at 56°C for about 2 d. The solidified samples embedded in paraffin were cut on a rotary microtome (Reichert-Jung microtome 2040, Cambridge Instruments, Nussloch, Germany). Thin sections (10 μm) were fixed on slides and deparaffinized in xylenes. Then, the samples were enclosed with Entellan neu (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

In Vivo Pollen Germination Experiment

Wild-type Arabidopsis pistils were prepared by removing other tissues from buds. Then the stigmas were brushed with anthers of atMGD-GUS transformants until they were completely covered with pollen grains. Pollinated pistils (total of 21 per transgenic line) were incubated on solidified Murashige and Skoog media for 12 h and used for GUS assay as described above.

RT-PCR and Northern-Blot Analysis

Total RNA was prepared, separated on an agarose gel, blotted onto nylon membranes, and probed with [α-32P]dCTP-labeled DNA. Hybridizations were carried out as described by Church and Gilbert (1984). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was carried out as previously described (Awai et al., 2001).

Galactosyltransferase Activity Assay

Crude enzyme solutions for the assay were prepared from the shoots or the roots of Arabidopsis according to Yamaryo et al. (2003). Total protein contents in the crude enzyme solution were quantified by the method of Bensadoun and Weinstein (1976) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Reaction products of galactosyltransferase were determined by one-dimensional thin-layer chromatography using 400 μm UDP-[14C]Gal (308.3 Bq nmol–1) as substrates. The crude enzyme (30 μL) was mixed with 110 μL of MOD buffer (100 mm MOPS-NaOH [pH 7.8] and 3 mm dithiothreitol) and 50 μL of 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol (200 μg; dispersed in 0.01% [w/v] Tween 20). Reaction mixture with 10 μL of 8 mm UDP-[14C]Gal (308.3 Bq nmol–1; 200 μL in final volume) was incubated at 30°C for 40 min. The reaction was stopped by vigorous vortexing with 1 mL of ethyl acetate and centrifuged twice at 1,500g for 5 min with 0.5 mL of 0.45% (w/v) NaCl. Nine hundred microliters of upper layer was dried and dissolved in 50 μL of chloroform: methanol (2:1 [v/v]) for one-dimensional thin-layer chromatography analyses. The product solutions were developed in chloroform:methanol:water (65:15:2 [v/v]). Radioactive spots were detected by Image Plate (Fuji Photofilm, Tokyo) and quantified by Image Analyser (Storm, Amersham Bioscience).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.032656.

This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Sports, Science and Culture of Japan (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas no. 15380049).

References

- Alban C, Joyard J, Douce R (1988) Preparation and characterization of envelope membranes from nongreen plastids. Plant Physiol 88: 709–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson MX, Stridh MH, Larsson KE, Liljenberg C, Sandelius AS (2003) Phosphate-deficient oat replaces a major portion of the plasma membrane phospholipids with the galactolipid digalactosyldiacylglycerol. FEBS Lett 537: 128–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awai K, Maréchal E, Block MA, Brun D, Masuda T, Shimada H, Takamiya K, Ohta H, Joyard J (2001) Two types of MGDG synthase genes, found widely in both 16:3 and 18:3 plants, differentially mediate galactolipid syntheses in photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic tissues in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10960–10965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N, Ellis J, Pelletier G (1993) In planta Agrobacterium mediated gene transfer by infiltration of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants. C R Acad Sci Paris Life Sci 316: 1194–1199 [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N, Pelletier G (1998) In planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants by vacuum infiltration. Methods Mol Biol 82: 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensadoun A, Weinstein D (1976) Assay of proteins in the presence of interfering materials. Anal Biochem 70: 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chory J, Reinecke D, Sim S, Washburn T, Brenner M (1994) A role for cytokinin in de-etiolation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 104: 339–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W (1984) Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 1991–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essigmann B, Güler S, Narang RA, Linke D, Benning C (1998) Phosphate availability affects the thylakoid lipid composition and expression of SQD1, a gene required for sulfolipid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 1950–1955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DE, Sang JP, Cominos X, Rothnie NE, Knox RB (1990) A study of phospholipids and galactolipids in pollen of two lines of Brassica napus L. (rapeseed) with different ratios of linoleic to linolenic acid. Plant Physiol 93: 418–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L-M, Wang Y-F, Wang H, Wu W-H (2001) In vitro Arabidopsis pollen germination and characterization of the inward potassium currents in Arabidopsis pollen grain protoplasts. J Exp Bot 52: 1603–1614 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JE, Benning C, Dörmann P (2001) The digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) synthase DGD1 is inserted into the outer envelope membrane of chloroplasts in a manner independent of the general import pathway and does not depend on direct interaction with monogalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase for DGDG biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 276: 31806–31812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härtel H, Benning C (2000) Can digalactosyldiacylglycerol substitute for phosphatidylcholine upon phosphate deprivation in leaves and roots of Arabidopsis? Biochem Soc Trans 28: 729–732 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härtel H, Dörmann P, Benning C (2000) DGD1-independent biosynthesis of extraplastidic galactolipids after phosphate deprivation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 10649–10654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis P, Dörmann P, Peto CA, Lutes J, Benning C, Chory J (2000) Galactolipid deficiency and abnormal chloroplast development in the Arabidopsis MGD synthase 1 mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 8175–8179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan P, Fromme P, Witt HT, Klukas O, Saenger W, Krauβ N (2001) Three-dimensional structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature 411: 909–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyard J, Maréchal E, Block MA, Douce R (1996) Plant galactolipids and sulfolipid: structure, distribution and biosynthesis. In M Smallwood, P Knox, DJ Bowles, eds, Membranes: Specialized Functions in Plants. BIOS Scientific Publishers, Oxford, pp 179–194

- Kelly AA, Dörmann P (2002) DGD2, an Arabidopsis gene encoding a UDP-galactose-dependent digalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase is expressed during growth under phosphate-limiting conditions. J Biol Chem 277: 1166–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AA, Froehlich JE, Dörmann P (2003) Disruption of the two digalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase genes DGD1 and DGD2 in Arabidopsis reveals the existence of an additional enzyme of galactolipid synthesis. Plant Cell 15: 2694–2706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang A, Musgrave ME (1996) Dynamics of vegetative cytoplasm during generative cell formation and pollen maturation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Protoplasma 194: 81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miège C, Maréchal E, Shimojima M, Awai K, Block MA, Ohta H, Takamiya K, Douce R, Joyard J (1999) Biochemical and topological properties of type A MGDG synthase, a spinach chloroplast envelope enzyme catalyzing the synthesis of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic MGDG. Eur J Biochem 265: 990–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bio-assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant 15: 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Arimitsu H, Yamaryo Y, Awai K, Masuda T, Shimada H, Takamiya K, Ohta, H (2003) Digalactosyldiacylglycerol is a major glycolipid in floral organs of Petunia hybrida. Lipids 38: 1107–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piffanelli P, Ross JHE, Murphy DJ (1997) Intra- and extracellular lipid composition and associated gene expression patterns during pollen development in Brassica napus. Plant J 11: 549–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-García MI, M'rani-Alaoui M, Fernández MC (2003) Behavior of storage lipids during development and germination of olive (Olea europaea L.) pollen. Protoplasma 221: 237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selstam E, Sandelius AS (1984) A comparison between prolamellar bodies and prothylakoid membranes of etioplasts of dark-grown wheat concerning lipid and polypeptide composition. Plant Physiol 76: 1036–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimojima M, Ohta H, Iwamatsu A, Masuda T, Shioi Y, Takamiya K (1997) Cloning of the gene for monogalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase and its evolutionary origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 333–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh MB, Hough T, Theerakulpisut P, Avjioglu A, Davies S, Smith PM, Taylor P, Simpson RJ, Ward LD, McCluskey J et al. (1991) Isolation of cDNA encoding a newly identified major allergenic protein of rye-grass pollen: intracellular targeting to the amyloplast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 1384–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaryo Y, Kanai D, Awai K, Shimojima M, Masuda T, Shimada H, Takamiya K, Ohta H (2003) Light and cytokinin play a co-operative role in MGDG synthesis in greening cucumber cotyledons. Plant Cell Physiol 44: 844–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Xu C, Benning C (2002) Arabidopsis disrupted in SQD2 encoding sulfolipid synthase is impaired in phosphate-limited growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 5732–5737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]