Abstract

Background

Volatile anesthetics (VAs) alter the function of key central nervous system proteins but it is not clear which, if any, of these targets mediates the immobility produced by VAs in the face of noxious stimulation. A leading candidate is the glycine receptor, a ligand-gated ion channel important for spinal physiology. VAs variously enhance such function, and blockade of spinal GlyRs with strychnine affects the minimal alveolar concentration (an anesthetic EC50) in proportion to the degree of enhancement.

Methods

We produced single amino acid mutations into the glycine receptorα1 subunit that increased (M287L, third transmembrane region) or decreased (Q266I, second transmembrane region) sensitivity to isoflurane in recombinant receptors, and introduced such receptors into mice. The resulting knockin mice presented impaired glycinergic transmission, but heterozygous animals survived to adulthood, and we determined the effect of isoflurane on glycine-evoked responses of brain stem neurons from the knockin mice, and the minimal alveolar concentration for isoflurane and other VAs in the immature and mature knockin mice.

Results

Studies of glycine-evoked currents in brain stem neurons from knock-in mice confirmed the changes seen with recombinant receptors. No increases in the minimal alveolar concentration were found in knockin mice, but the minimal alveolar concentration for isoflurane and enflurane (but not halothane) decreased in 2-week-old Q266I mice. This change is opposite to the one expected for a mutation that decreases the sensitivity to volatile anesthetics.

Conclusion

Taken together, these results indicate that glycine receptors containing the α1 subunit are not likely to be crucial for the action of isoflurane and other VAs.

INTRODUCTION

A present consensus suggests that volatile anesthetics (VAs) bind to proteins to produce their effects, including immobility1. The key question is ‘Which proteins?’ The list of candidates is short1–3. A top candidate is the glycine receptor (GlyR).

Evidence for the GlyR as a target for VA includes their localization and sensitivity to VAs. The RNAs encoding the GlyR subunits are mostly in the spinal cord and brain stem4, and the spinal cord mediates the immobility effect of VA5. Moreover, anesthetic concentrations of VAs substantially enhance inhibitory currents through the GlyR, both in heterologous systems6–8 and neurons8. More direct evidence arises from the use of strychnine, a competitive GlyR-specific antagonist, both at the neuronal and whole animal level. The application of halothane to decerebrate rats depressed the spinal cord sensory neuronal activity to noxious stimuli; the concurrent application of strychnine partially reversed the halothane-induced depression9. Sevoflurane reduced spontaneous action potential firing of ventral horn interneurons in cultured spinal cord tissue slices; application of strychnine decreased the sevoflurane effect10. Intrathecal administration of strychnine increased the Minimal Alveolar Concentration (MAC) of isoflurane11. The magnitude of GlyR potentiation expressed in oocytes varies according to the VA used12. Intrathecal administration of strychnine to rats anesthetized with halothane, isoflurane or cyclopropane increased MAC in proportion to the enhancement of GlyRs observed in vitro13. Furthermore, intrathecal glycine reduced the isoflurane MAC in rats14. These results are compatible with the hypothesis that GlyRs partly mediate the capacity of VAs to produce immobility.

Construction of chimeric glycine-γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors (GABAA-Rs) allowed the identification of transmembrane amino acids crucial to the VAs’ action, namely S267 and A288 in the second and third GlyR transmembrane domains15. Mutation of S267 to cysteine and subsequent labeling with thiol-specific reagents blocked the VA potentiation of GlyRs16,17. Furthermore, a crystal structure of a prokaryotic protein closely related to GlyR was obtained in the presence of VAs and showed selective binding of the anesthetics to the regions proposed in the earlier studies of GlyR18.

The identification of a mutation in a receptor that renders it insensitive or hypersensitive to modulation by VAs would allow construction of a knock-in mouse that could be tested for changes in the sensitivity to VAs. This approach was successful in showing that specific GABAA-Rs are responsible for at least some of the actions of certain injectable anesthetics19,20. In our studies of alcohol action, we found two mutations in the α1 GlyR subunit, one in the second (Q266I) and another in the third transmembrane domain (M287L) that decreased ethanol modulation of GlyR21. Mutant mice were constructed in which each of these mutant α1 GlyR subunits replaced the endogenous GlyR subunit (knockin mice)21. The goal of the present study was to determine if these mutations altered the action of VA on GlyR and if such alterations would affect the immobility produced by VA. This was accomplished by studying glycine responses of recombinant receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes and of neurons isolated from brain stem of wild type and knockin mice, and the immobilizing potency (the MAC of anesthetic that abolished movement in response to noxious stimulation in 50% of test subjects) of anesthetics in wild-type and knockin mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Knockin mouse production and the electrophysiological techniques were described in detail in Borghese et al.21. We briefly describe them here, and add pertinent details. The experimental work on animals conformed to the guidelines laid out in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approval of the corresponding institutional Animal Care Committees was obtained.

Electrophysiology in Xenopus oocytes

Chloroform was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO), and isoflurane was purchased from Marsam Pharmaceuticals (Cherry Hill, NJ). Isoflurane and chloroform solutions were prepared in buffer immediately before application.

Manually isolated oocytes from Xenopus laevis frogs were injected in the nuclei with complementary DNA encoding wild type and mutated human α1 GlyR subunits. After 1–5 days, recordings were carried out using the whole-cell two-electrode voltage clamp configuration. All drugs were applied by bath-perfusion and solutions were prepared the day of the experiment. To study the chloroform (1 mM) and isoflurane (0.3 mM) modulation of glycine currents, the glycine concentration equivalent to 5% of the maximal glycine-evoked current (EC5) was determined after applying the glycine concentration that produced maximal current (3 mM for wild-type, 10 mM for mutant). Glycine was removed with a washout of 5 min between all applications, except after application of maximal glycine concentrations (15 min). After two applications of EC5 glycine, each of the modulators was preapplied for 1 min and then coapplied with glycine for 30 s. EC5 glycine was applied in between coapplication of glycine and modulator. The concentrations of isoflurane and chloroform were chosen as equivalent to 1 × MAC22. All experiments shown include data obtained from oocytes taken from at least two different frogs, and oocytes that presented a maximal current > 20 μA were not included in the data collection.

Knockin Mouse Production

Breeding colonies were established in the Lovinger and Eger laboratories, and mice were produced by heterozygous breeding, resulting in litters with wild-type, heterozygous mutant, and homozygous mutant mice. Homozygous mice for either mutation appear normal at birth, but display tremors and reduced growth 2 two weeks of age with lethality occurring by 2–3 weeks of age for Q266I mice21. Thus, studies with mice older than 3 weeks of age were carried out with only heterozygous (vs. wild-type) mice.

Isolation of Neurons and Electrophysiological Recording

Postnatal day 14–21 mice were sacrificed by decapitation under halothane (Sigma-Aldrich) anesthesia and their brains were rapidly removed and placed in ice-cold buffer. Brain stem slices were cut using a vibrating blade microtome (Leica VT1200S; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), incubated with pronase, and then with thermolysin. The slices were then transferred to a culture dish, and mildly triturated using pipettes to dissociate single neurons.

Membrane currents were recorded in the whole-cell configuration at 20–22°C. Cells were held at −60 mV unless otherwise indicated. Data were acquired using pClamp 9.2 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Isoflurane was purchased from Baxter (Deerfield, IL). Isoflurane solution was prepared in the extracellular recording solution immediately before beginning experiments each day, and kept in a sealed bottle. Solutions were applied through 3 barrel square glass tubing (Warner Instrument, Hamden, CT) with a tip diameter of ~700 μm, using the Warner Fast-Step stepper-motor driven system. The solution exchange time constants were ~4 ms for an open pipette tip and 4–12 ms for whole-cell recording. The solution in the wells feeding into the solution exchange system was changed after recording from 1–2 cells to replenish isoflurane in the line. The drug application system was sealed at all times except when applying isoflurane to a cell, to reduce loss of the volatile anesthetic. In neurons that were recorded for at least 30 min, the isoflurane-induced potentiation did not change over time, indicating limited, if any, loss of the volatile anesthetic from our system.

MAC Determination

Animals were held in rooms with 12-h on-off light cycles. The offspring were observed daily for signs of central nervous system irritability, namely tremors. When tremors were observed in a given litter, the capacity of VA to induce immobility in 50% of individual littermates in the face of noxious stimulation (i.e., MAC) was tested within 2–4 days for all mice using techniques described previously23. Rectal temperatures were monitored and usually maintained between 35.5 and 38.5°C. Anesthetic concentrations were monitored with an infrared analyzer (Datascope, Helsinki, Finland). The initial anesthetic concentration was imposed for a 40-min equilibration period. A low initial target concentration was chosen to ensure movement in response to up to a 1-min application of an alligator clip to the base of the tail. We then increased the anesthetic concentration in steps of 15–20% of the preceding concentration, holding each step for a minimum of 20 to 30 min before again applying the alligator clip. This continued until all mice ceased moving in response to the stimulation. At the end of each step (after application of the tail clip), a sample of gas was taken for anesthetic analysis by gas chromatography (see next paragraph). On completion of these studies, snips of tail tips were sent to the Harris laboratory for genotyping. Two groups that were not genotyped (2-week-old Q266I mice tested with enflurane and halothane) were grouped according to the phenotype: tremoring (homozygous) and nontremoring (wild-type and heterozygous) mice. Mice then were returned to their home cages and in 2 days tested with another anesthetic. The test anesthetics were isoflurane and enflurane for M287L mice, and isoflurane, halothane and enflurane for Q266I mice. Surviving mice (i.e., wild-type and heterozygous mice) then were allowed to grow to 8–12 weeks of age and were tested for MAC for isoflurane, enflurane, and/or cyclopropane.

The gas chromatograph (Gow-Mac 750 flame ionization detector gas chromatograph; Gow-Mac Instrument Corp., Bridgewater, NJ) was calibrated with secondary standards from tanks containing volatile anesthetic or from concentrations obtained by serial dilution from 100% cyclopropane. MAC for each mouse was calculated as the mean of the concentrations that bracketed movement-nonmovement. The group MAC and standard errors were calculated from these individual values.

Statistical analysis

Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used to conduct the statistical analysis. In all cases, pooled data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Differences were assessed with Student’s two-tailed t-test in the oocyte recordings. In the neuronal recordings, we used One-Way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test, where the objective is to identify groups whose means are significantly different from the mean of a selected “reference group”, in our case, the wild-type mice. We accepted p < 0.05 as significant.

RESULTS

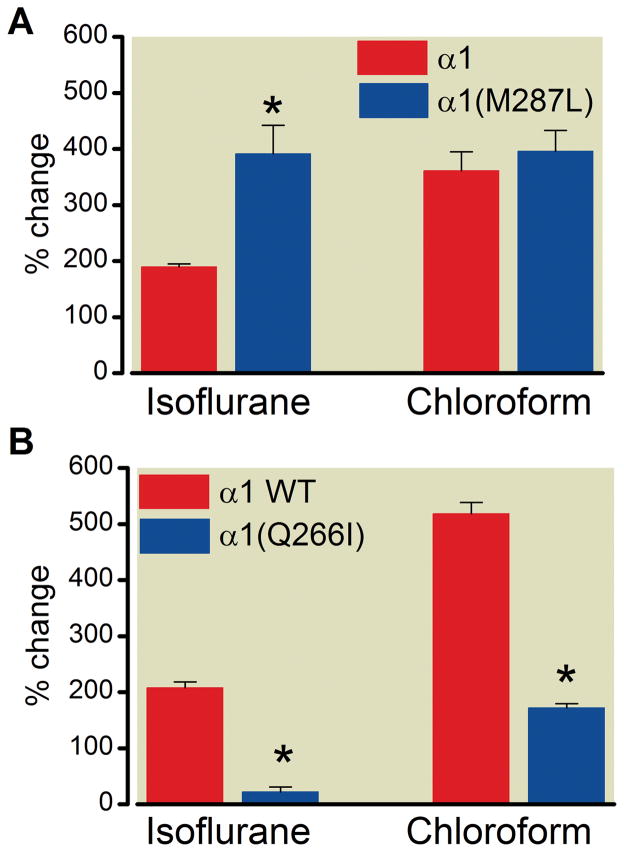

We first asked if the M287L or Q266I mutations altered the sensitivity of GlyR to modulation by anesthetics. The application of isoflurane or chloroform produced different effects on the glycine-evoked currents through the mutant receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes (representative tracings in the presence of isoflurane in fig. 1). When applied to the α1(M287L) GlyR, 0.3 mM isoflurane showed an increased potentiation compared with α1 wild-type, while the chloroform (1 mM) potentiation was unchanged (fig. 2A). In line with the observed lack of alcohol effects on Q266I21, isoflurane potentiation was almost abolished in α1(Q266I) GlyR, and chloroform potentiation was severely decreased (fig. 2B).

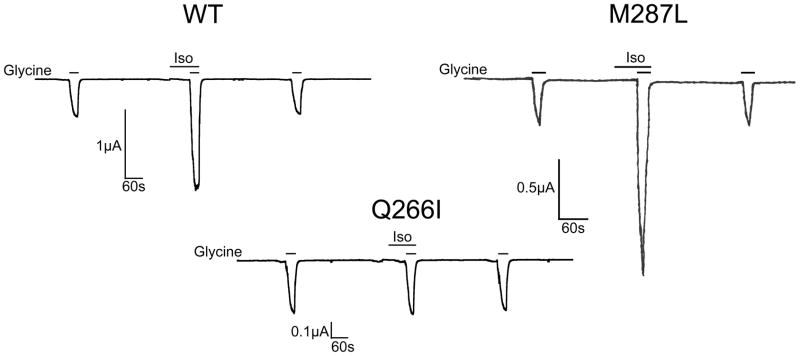

Figure 1.

Representative tracings of isoflurane (0.3 mM) effect on currents induced by glycine (with a concentration that induced a current that is 5% of the maximal current, effective concentration 5, or EC5) in homomeric α1 wild-type, α1(M287L) and α1(Q266I) GlyRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Data from multiple recordings are presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Volatile anesthetics’ effect on glycine responses in homomeric α1 wild-type, α1(M287L) and α1(Q266I) expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Isoflurane (0.3 mM) and chloroform (1 mM) potentiation of glycine responses (with a concentration that induced a current that is 5% of the maximal current, effective concentration 5, or EC5) in A) α1 wild-type (n= 6) and α1(M287L) (n= 5), and B) α1 wild-type (n= 4) and α1(Q266I) (n= 4). Values are means ± S.E.M.; *p< 0.01 versus corresponding wild-type, Student’s t-test analysis.

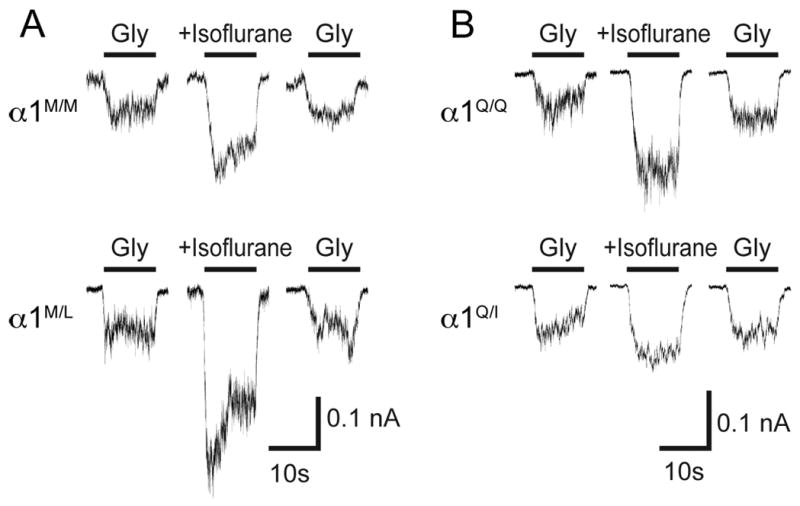

Previous studies had shown that although the glycine affinity is not modified in neurons from homozygous mice, the maximal glycine current is decreased in homozygous mice21. We studied the isoflurane effect on submaximal (10 μM) glycine-activated currents in isolated neurons from the knockin mice (fig. 3 shows representative tracings). The GlyR modulation by isoflurane (1 mM) in isolated neurons from knockin mice showed changes that were similar to those observed in Xenopus oocytes. In neurons from M287L mice, the isoflurane effect on glycine-evoked currents was increased, and this depended on gene ‘dosage’: it was greater in neurons from homozygous than in heterozygous mice, and greater in heterozygous than in wild-type mice (figs. 3A and 4A). In neurons from Q266I mice, the isoflurane effect was decreased according to the presence of the mutation: essentially absent in homozygous and smaller in heterozygous than in wild-type (figs. 3B and 4B).

Figure 3.

Representative tracings of isoflurane (1 mM) on (10 μM) glycine-evoked currents in neurons from wild type or heterozygous mutant mice.

A) Currents in neurons from M287L mice: α1M/M, wild-type (upper panel) and α1M/L, heterozygous (lower panel). B) Currents in neurons from Q266I mice: α1Q/Q, wild-type (upper panel) and α1Q/I, heterozygous (lower panel). Data from multiple tracings are presented in Fig. 4.

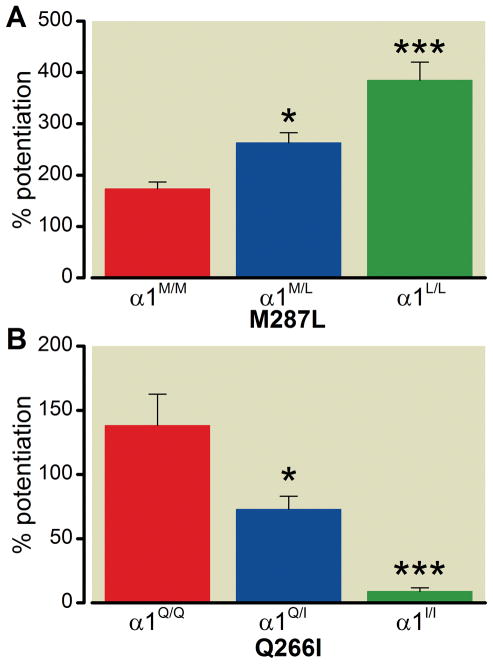

Figure 4.

Isoflurane (1 mM) effect on glycine-evoked (10 μM) currents in isolated neurons from wild-type and knockin mice. A. Neurons form M287L mice: α1M/M, wild-type; α1M/L, heterozygous; α1L/L, homozygous. B. Neurons form Q266I mice:α1Q/Q, wild-type; α1Q/I, heterozygous; α1I/I, homozygous. Values are means ± S.E.M.; n= 6 for each group; *p <0.05, **p <0.001 versus corresponding wild-type, One-Way ANOVA, Dunnett’s post-hoc test.

Anesthetic sensitivity in vivo was evaluated by determining the MAC values for M287L and Q266I mice of different ages: 14–21 days of age and adult (more than 8-week old), in homozygous, heterozygous, and wild-type mice (tables 1 and 2). Cyclopropane was tested as a negative control: it has a small effect on GlyRs expressed in heterologous systems12. The MAC values for isoflurane and enflurane were unchanged in M287L knockin mice compared with wild-type mice. In adult Q266I heterozygous mice, the MAC values for isoflurane and cyclopropane were not modified compared with wild-type mice. In 2-week-old Q266I mice, tremoring (homozygous) mice showed a decrease in isoflurane and enflurane MAC values compared with nontremoring (heterozygous + wild-type), while halothane showed no differences between these two groups.

Table 1.

Minimal Alveolar Concentration in M287L Knock-in Mice

| Volatile Anesthetic | Age | α1M/M (wild-type) | α1M/L (heterozygous) | α1L/L (homozygous) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflurane | 2–4 weeks | 1.65 ± 0.07 (5) | 1.77 ± 0.02 (4) | 1.65 ± 0.06 (7) |

| adult# | 1.54 ± 0.07 (6) | 1.50 ± 0.06 (10) | ||

| Enflurane | 2–4 weeks | 2.45 ± 0.07 (5) | 2.42 ± 0.08 (8) | 2.33 ± 0.03 (9) |

| adult | 2.28 ± 0.07 (6) | 2.38 ± 0.05 (7) |

Values are in % atmosphere (average ± S.E.M., n between parenthesis).

8-week old or older

Table 2.

Minimal Alveolar Concentration in Q266I Knock-in Mice

| Volatile Anesthetic | Age | α1Q/Q (wild-type) | α1Q/I (heterozygous) | α1I/I (homozygous) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflurane | 2 weeks | 1.79 ± 0.07 (10) | 1.48 ± 0.03 (8)* | |

| Enflurane | 2 weeks | 3.55 ± 0.09 (8) | 3.23 ± 0.11 (5)* | |

| Halothane | 2 weeks | 1.93 ± 0.05 (9) | 1.86 ± 0.09 (9) | |

| Isoflurane | adult | 1.69 ± 0.06 (7) | 1.73 ± 0.07 (5) | |

| Cyclopropane | adult | 18.7 ± 1.1 (7) | 16.4 ± 1.0 (5) | |

Values are in % atmosphere (average ± S.E.M., n between parenthesis). Two-week-old mice were grouped according to their phenotype (tremoring mice: homozygous; nontremoring mice: wild-type or heterozygous). Adult mice (8-week old or older) were grouped according to genotype.

p <0.05 versus corresponding control group, Student’s t-test.

DISCUSSION

Defining protein sites of VA action has proven remarkably difficult1,3. It is useful to consider the criteria that must be satisfied for a protein to be considered a plausible target for VA action. VAs have many similarities to ethanol (small molecules, low potency, multiple potential sites of action), and ethanol might be considered as a VA. Four criteria were proposed for defining a molecular target of alcohol action24, and they are equally applicable to other VA. In brief, they are: 1. Function of the protein must be altered by pharmacologically reasonable concentrations of the drug; 2. Mutation of specific amino acids should provide evidence of a binding site; 3. Manipulation of the protein in vivo (e.g., knockin mice) should produce expected changes in behavioral actions of the drug; 4. Physical structural studies should demonstrate the presence of the drug at the proposed sites in the protein. Both GABAA-Rs and GlyRs fulfill several of these criteria. Pharmacological concentrations of most (but not all) VAs enhance the function of these receptors2, and extensive mutation and thiol-labeling studies provide evidence for a binding site within the transmembrane regions15–17. In addition, a recent structural study of GLIC, a ligand-gated ion channel closely related to GlyR and GABAA-R, shows the binding of anesthetics in the site proposed based on mutations18. The requirement to introduce a VA-resistant protein into a mouse and reduce the VA immobilizing effect in vivo has proven to be the most difficult criterion to satisfy. Thus far, knockin mice constructed with VA resistant GABAA-Rs have not shown any increase in MAC25–28. This is in contrast to injectable anesthetics such as propofol and etomidate where a knockin mouse with a GABAA-R resistant subunit [β3(N265M)] displayed remarkable resistance to anesthetics20 with little change in the action of VAs28. With the lack of support for GABAA-R as a mechanism for the immobility produced by VA, GlyR emerged as one of the ‘last best hopes’29, making the construction and study of knockin mice for this receptor a critical step. To accomplish this, we constructed single amino acid mutations in the α1 GlyR subunit that would increase or decrease the actions of VA and constructed knockin mice with each of the mutations21. We chose the α1 subunit because there are two kinds of GlyR subunits, α (α1-α4) and β. The α2 subunit predominates perinatally, while the heteromeric α1β GlyRs replace them during the first 3 weeks of the postnatal stage, and are the main GlyR present in spinal cord and brain stem in adulthood4. The α1β GlyR is difficult to express in Xenopus oocytes, so we decided to use the homomeric α1 GlyR in our heterologous experiments.

The striking finding from the present experiments is that introduction of GlyR α1 subunits with either enhanced or decreased modulation by VA into mice has almost no effect on the ability of these agents to produce immobility, and none in the direction expected if the immobility effect was mediated by enhancement of currents mediated by GlyRs. Electrophysiological studies of recombinant receptors as well as neurons from the mutant mice showed that the M287L and Q266I mutations in transmembrane regions of the GlyR consistently altered anesthetic actions, yet the MAC for immobility was not altered for any anesthetic tested, with two exceptions. The 2-week old homozygous Q266I mice showed a small decrease in the MAC value for isoflurane and enflurane (17% and 9%, respectively). If the immobility effect were in part mediated by GlyRs, the presence of a mutation in the GlyRs that made them insensitive to a VA would be predicted to increase, not decrease, the concentration of anesthetic necessary to achieve immobility in the face of a noxious stimulus. In this particular case, the MAC was reduced. In 2-week old mice, the perinatal α2 GlyRs are being replaced by the α1β GlyRs44, which carry the Q266I mutation in α1. These mutated GlyRs have a reduced functionality21, that translates in modification in the behavior and response to nonglycinergic drugs30. Some of these changes could be attributed to the development of compensatory changes (see next paragraph). Furthermore, the adult heterozygous Q266I did not differ from wild type in their response to isoflurane.

Because strychnine increased MAC for VAs in proportion to their ability to modulate GlyR (halothane > isoflurane > cyclopropane), it appeared that actions of VAs on GlyR likely mediated at least part of immobility, making the GlyR a leading candidate target for VAs13,29. However, the current findings provide strong evidence that the α1 GlyR is not important for VA immobility.

One caveat is that the effects of the mutations we studied were not limited to alterations in VA actions on the receptors, as they also impaired the function of GlyRs. It is possible that reduced glycinergic neurotransmission in the mutants could lead to compensatory changes in other neurotransmitters. Indeed, we found that the sedative effects of several drugs that do not affect GlyRs, such as flurazepam and ketamine, were increased in both mutants30. Additionally, the changes in the loss of righting reflex induced by flurazepam and ketamine were more pronounced in Q266I than in M287L, as could be expected considering that the impairment in glycinergic transmission, as assessed by the acoustic startle reflex and the mortality of homozygous knockin mice, was more marked in Q266I than in M287L21,30. However, we need to keep in mind that immobility (assessed through MAC) and sedation (assessed through loss of righting reflex) are mediated by different areas in the central nervous system31. Furthermore, the data do not support the simple explanation that main systems, like the GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission, have undergone changes to compensate for a decrease in the glycinergic transmission, because the N-methyl-D-aspartic acide-induced tonic convulsions were the same in heterozygous knockin mice versus wild type30, and the flunitrazepam binding was unchanged in Q266I heterozygous mice in brain stem and spinal cord21. So, even if other signaling systems changed, we would have to propose that these changes exactly offset the altered sensitivity of the GlyR to VAs in exactly the same structures, when the compensatory changes would presumably offset the decreased glycinergic transmission, not the changes in the sensitivity to isoflurane. This seems unlikely because both the M287L and Q266I mutations reduce GlyR function, but they do it to a different degree21, and there is no evidence for specific compensatory changes in the structures mediating immobility. We conclude that actions of VAs on the α1 GlyR have little or no role in the production of immobility by VAs. As Thomas Henry Huxley said32, we face once again “the great tragedy of Science – the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.” We conclude that the known molecular targets of VAs are not able to account for the immobilizing actions of VAs, and a search for new targets is required.

What we already know about this topic

Inhibitory spinal glycine receptor function is enhanced by volatile anesthetics, making this a leading candidate for their immobilizing effect

Point mutations in the α1 subunit of glycine receptors have been identified that increase or decrease receptor potentiation by volatile anesthetics

What this article tells us that is new

Mice harboring specific mutations in their glycine receptors that increased or decreased potentiation by volatile anesthetic in vitro did not have significantly altered changes in anesthetic potency in vivo

These findings indicate that this glycine receptor does not mediate anesthetic immobility, and that other targets must be considered

Acknowledgments

CMB and RAH would like to thank Rebecca J. Howard and Kathryn Ondricek for constructing the Q266I mutant complementary DNA, and Chelsea Geil, Brianne Patton and Virginia Bleck for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure of funding: National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, grants 1PO1GM47818 and AA06399 supported this work. WX, LZ and DML would like to acknowledge support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Division of Intramural Clinical and Biomedical Research.

References

- 1.Franks NP. Molecular targets underlying general anaesthesia. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl 1):S72–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamakura T, Bertaccini E, Trudell JR, Harris RA. Anesthetics and ion channels: Molecular models and sites of action. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:23–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eger EI, 2nd, Raines DE, Shafer SL, Hemmings HC, Jr, Sonner JM. Is a new paradigm needed to explain how inhaled anesthetics produce immobility? Anesth Analg. 2008;107:832–48. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318182aedb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch JW. Native glycine receptor subtypes and their physiological roles. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antognini JF, Carstens E. In vivo characterization of clinical anaesthesia and its components. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:156–66. doi: 10.1093/bja/aef156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mascia MP, Machu TK, Harris RA. Enhancement of homomeric glycine receptor function by long-chain alcohols and anaesthetics. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:1331–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison NL, Kugler JL, Jones MV, Greenblatt EP, Pritchett DB. Positive modulation of human γ-aminobutyric acid type A and glycine receptors by the inhalation anesthetic isoflurane. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44:628–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Downie DL, Hall AC, Lieb WR, Franks NP. Effects of inhalational general anaesthetics on native glycine receptors in rat medullary neurons and recombinant glycine receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:493–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamauchi M, Sekiyama H, Shimada SG, Collins JG. Halothane suppression of spinal sensory neuronal responses to noxious peripheral stimuli is mediated, in part, by both GABA(A) and glycine receptor systems. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:412–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200208000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grasshoff C, Antkowiak B. Propofol and sevoflurane depress spinal neurons in vitro via different molecular targets. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1167–76. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200411000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Wu S, Eger EI, 2nd, Sonner JM. Neither GABA(A) nor strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors are the sole mediators of MAC for isoflurane. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:123–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200101000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hara K, Eger EI, 2nd, Laster MJ, Harris RA. Nonhalogenated alkanes cyclopropane and butane affect neurotransmitter-gated ion channel and G-protein-coupled receptors: Differential actions on GABAA and glycine receptors. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1512–20. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200212000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Laster MJ, Hara K, Harris RA, Eger EI, 2nd, Stabernack CR, Sonner JM. Glycine receptors mediate part of the immobility produced by inhaled anesthetics. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:97–101. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200301000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao J, Zhang Y, Eger EI, 2nd, Sonner J. Intrathecal glycine significantly decreases the minimum alveolar concentration of isoflurane in rats. Chin Med Sci J. 2008;23:16–8. doi: 10.1016/s1001-9294(09)60003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mihic SJ, Ye Q, Wick MJ, Koltchine VV, Krasowski MD, Finn SE, Mascia MP, Valenzuela CF, Hanson KK, Greenblatt EP, Harris RA, Harrison NL. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABA(A) and glycine receptors. Nature. 1997;389:385–9. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mascia MP, Trudell JR, Harris RA. Specific binding sites for alcohols and anesthetics on ligand-gated ion channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9305–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160128797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lobo IA, Mascia MP, Trudell JR, Harris RA. Channel gating of the glycine receptor changes accessibility to residues implicated in receptor potentiation by alcohols and anesthetics. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33919–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nury H, Van Renterghem C, Weng Y, Tran A, Baaden M, Dufresne V, Changeux JP, Sonner JM, Delarue M, Corringer PJ. X-ray structures of general anaesthetics bound to a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2011;469:428–31. doi: 10.1038/nature09647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeller A, Arras M, Jurd R, Rudolph U. Identification of a molecular target mediating the general anesthetic actions of pentobarbital. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:852–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jurd R, Arras M, Lambert S, Drexler B, Siegwart R, Crestani F, Zaugg M, Vogt KE, Ledermann B, Antkowiak B, Rudolph U. General anesthetic actions in vivo strongly attenuated by a point mutation in the GABA(A) receptor β3 subunit. FASEB J. 2003;17:250–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0611fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borghese CM, Blednov YA, Quan Y, Iyer SV, Postdoc, Mihic SJ, Zhang L, Lovinger DM, Trudell JR, Homanics GE, Harris RA. Characterization of two mutations, M287L and Q266I, in the α1 glycine receptor subunit that modify sensitivity to alcohols and anesthetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340:304–16. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.185116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franks NP, Lieb WR. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of general anaesthesia. Nature. 1994;367:607–14. doi: 10.1038/367607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonner JM, Gong D, Eger EI., 2nd Naturally occurring variability in anesthetic potency among inbred mouse strains. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:720–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200009000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris RA, Trudell JR, Mihic SJ. Ethanol’s molecular targets. Sci Signal. 2008;1:re7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.128re7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Werner DF, Swihart A, Rau V, Jia F, Borghese CM, McCracken ML, Iyer S, Fanselow MS, Oh I, Sonner JM, Eger EI, 2nd, Harrison NL, Harris RA, Homanics GE. Inhaled anesthetic responses of recombinant receptors and knockin mice harboring α2(S270H/L277A) GABA(A) receptor subunits that are resistant to isoflurane. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:134–44. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.170431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J, Atherley R, Werner DF, Homanics GE, Carstens E, Antognini JF. Isoflurane depression of spinal nociceptive processing and minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration are not attenuated in mice expressing isoflurane resistant γ-aminobutyric acid type-A receptors. Neurosci Lett. 2007;420:209–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonner JM, Werner DF, Elsen FP, Xing Y, Liao M, Harris RA, Harrison NL, Fanselow MS, Eger EI, 2nd, Homanics GE. Effect of isoflurane and other potent inhaled anesthetics on minimum alveolar concentration, learning, and the righting reflex in mice engineered to express α1 γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors unresponsive to isoflurane. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:107–13. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao M, Sonner JM, Jurd R, Rudolph U, Borghese CM, Harris RA, Laster MJ, Eger EI., 2nd β3-containing γ-aminobutyric acidA receptors are not major targets for the amnesic and immobilizing actions of isoflurane. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:412–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000154196.86587.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonner JM, Antognini JF, Dutton RC, Flood P, Gray AT, Harris RA, Homanics GE, Kendig J, Orser B, Raines DE, Rampil IJ, Trudell J, Vissel B, Eger EI., 2nd Inhaled anesthetics and immobility: Mechanisms, mysteries, and minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:718–40. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000081063.76651.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blednov YA, Benavidez JM, Homanics GE, Harris RA. Behavioral characterization of knockin mice with mutations M287L and Q266I in the glycine receptor α1 subunit. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340:317–29. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.185124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. Molecular and neuronal substrates for general anesthetics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:709–20. doi: 10.1038/nrn1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huxley TH. Collected Essays. 1. Vol. 8. London: Macmillan; 1908. p. 244. [Google Scholar]