Abstract

Primary osteoporosis is an age-related disease characterized by an imbalance in bone homeostasis. While the resorptive aspect of the disease has been studied intensely, less is known about the anabolic part of the syndrome or presumptive deficiencies in bone regeneration. Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are the primary source of osteogenic regeneration. In the present study we aimed to unravel whether MSC biology is directly involved in the pathophysiology of the disease and therefore performed microarray analyses of hMSC of elderly patients (79–94 years old) suffering from osteoporosis (hMSC-OP). In comparison to age-matched controls we detected profound changes in the transcriptome in hMSC-OP, e.g. enhanced mRNA expression of known osteoporosis-associated genes (LRP5, RUNX2, COL1A1) and of genes involved in osteoclastogenesis (CSF1, PTH1R), but most notably of genes coding for inhibitors of WNT and BMP signaling, such as Sclerostin and MAB21L2. These candidate genes indicate intrinsic deficiencies in self-renewal and differentiation potential in osteoporotic stem cells. We also compared both hMSC-OP and non-osteoporotic hMSC-old of elderly donors to hMSC of ∼30 years younger donors and found that the transcriptional changes acquired between the sixth and the ninth decade of life differed widely between osteoporotic and non-osteoporotic stem cells. In addition, we compared the osteoporotic transcriptome to long term-cultivated, senescent hMSC and detected some signs for pre-senescence in hMSC-OP.

Our results suggest that in primary osteoporosis the transcriptomes of hMSC populations show distinct signatures and little overlap with non-osteoporotic aging, although we detected some hints for senescence-associated changes. While there are remarkable inter-individual variations as expected for polygenetic diseases, we could identify many susceptibility genes for osteoporosis known from genetic studies. We also found new candidates, e.g. MAB21L2, a novel repressor of BMP-induced transcription. Such transcriptional changes may reflect epigenetic changes, which are part of a specific osteoporosis-associated aging process.

Introduction

Primary osteoporosis is a polygenetic disease characterized by low bone mineral density and microarchitectural deteriorations, leading to an increased risk of fragility fractures of vertebrae, femoral neck and other typical localizations of lower incidence [1]. Advanced age, gender and immobilization are major risk factors for developing osteoporosis besides a series of other contributors, e.g. diminished sex steroid production in elderly individuals and after menopause [2], [3]. During the first decades of osteoporosis research the main focus has been the imbalance of bone resorption over bone formation as a consequence of pathologically enhanced osteoclast development and function [4]. Hence, antiresorptive treatment, targeting mature osteoclasts and the osteoclastogenesis promoting RANK (Receptor Activator of NF-κB)/RANKL (RANK ligand) pathway has evolved as a standard therapy over the last decades [1], [5]. In contrast, research on presumptive deficiencies in bone anabolism has been relatively neglected. Little is known about the impact of bone forming osteoblasts on the pathophysiology of osteoporosis in humans, although evidence was found for reduced activity [6] and enhanced apoptosis [7], [8]. Osteoblasts derive from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), which can also give rise to other mesodermal cell types, such as adipocytes, chondrocytes and fibroblasts [9]. Despite of MSC as the source for bone regeneration it is currently unknown if intrinsic deficiencies in these cells contribute to osteoporotic bone loss.

Three major signaling pathways have been identified to govern bone regeneration with an intense intracellular crosstalk: a) Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling, b) WNT signaling and c) signaling through parathyroid hormone receptor (PTH1R) activation. Recent research has highlighted the relevance of inhibitors of the respective pathways for the regulation of bone mass and thereby suggested new targets for the treatment of bone loss [1].

BMP proteins belong to the TGFβ superfamily and activation of BMP receptors leads to induction of transcription through either MAP kinase signaling or phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8 proteins [10], [11]. Signaling through BMP proteins is regulated by either extracellular antagonists such as Noggin and Gremlin [12], [13] or by intracellular inhibitors, e.g. inhibitory SMAD proteins [14] or nuclear MAB21L2 (Mab-21-like 2), a recently discovered BMP4 inhibitor [15].

Depending on coreceptors WNT signaling can be divided into canonical and non-canonical pathways. Canonical signaling is induced by binding of WNT ligands to the receptors of the Frizzled (FZD) family and LRP5/6 coreceptors, which results in activation of WNT-specific gene transcription by stabilization and nuclear translocation of β-Catenin. Non-canonical WNT signaling is transduced through FZD and ROR2/RYK coreceptors, which leads to the activation of G-protein or Ca2+-dependent cascades [16]. In MSC canonical signaling through WNT2, WNT3 or WNT3a induces proliferation and keeps the cells in an undifferentiated state, whereas non-canonical signaling, e.g. by WNT5a, WNT5b or WNT11, supports osteogenesis [17], [18], [19].

The osteocyte-specific factor Sclerostin (SOST) was described as an inhibitor of canonical WNT signaling, whereas there is ongoing discussion about its putative inhibitory effect on BMP signaling [20], [21]. Sclerostin leads to reduced bone formation [22] and loss of function mutations are responsible for the high bone mass syndromes Van Buchem disease and sclerosteosis [23]. A neutralizing antibody against Sclerostin is a new, upcoming therapeutic treatment for osteoporosis [1], [24].

Intermittent treatment with parathyroid hormone (PTH) is another therapeutical approach for osteoporosis and activates the third major signaling pathway in bone regeneration. However, continuous activation of PTH receptor has negative effects on bone homeostasis because subsequently enhanced RANKL expression on maturing osteoblasts stimulates osteoclast formation and bone resorption [25], [26].

Interestingly, the genetic loci of proteins involved in the signaling pathways mentioned above, e.g. LRP5, LRP4, Sclerostin, PTH, BMPs or BMP receptor BMPR1B, have already been linked to the polygenetic nature of primary osteoporosis by whole-genome association studies and meta-analyses [27], [28], [29], [30].

Besides genetic predisposition, advanced age is another strong risk factor for developing osteoporosis with adult stem cells being the restrictive parameter for unlimited tissue regeneration. In vitro, cells exhibit limited dividing capacity and enter replicative senescence, a state of irreversible G1 phase arrest, after about 50 population doublings [31], [32]. It is caused by multiple factors like telomere shortening, oxidative stress, deficiencies in DNA repair and epigenetic changes. Currently it is still controversial, whether clock-driven, organismic aging is caused by the loss of self-regeneration due to replicative senescence of stem cells or by extrinsic environmental factors [33].

The impact of presumptive deficiencies of hMSC in elderly, osteoporotic patients has not been studied intensely yet and to our knowledge changes at the gene expression level have not been examined before. Therefore, we performed microarray analyses of hMSC of elderly donors with and without osteoporosis to detect disease-associated changes in gene expression. With osteoporosis being an age-related disease, we also investigated the impact of aging on hMSC in general by analyzing the transcriptome of in vivo-aged and in vitro-aged, senescent cells. We discovered that hMSC of patients suffering from severe osteoporosis display a disease-specific gene expression pattern that is distinct from the effects of organismic aging per se. Besides the induced expression of inhibitors of bone formation we detected promising new candidate genes for osteoporosis and even found evidence for reduced stem cell function.

Results

Osteoporosis-induced changes in gene expression

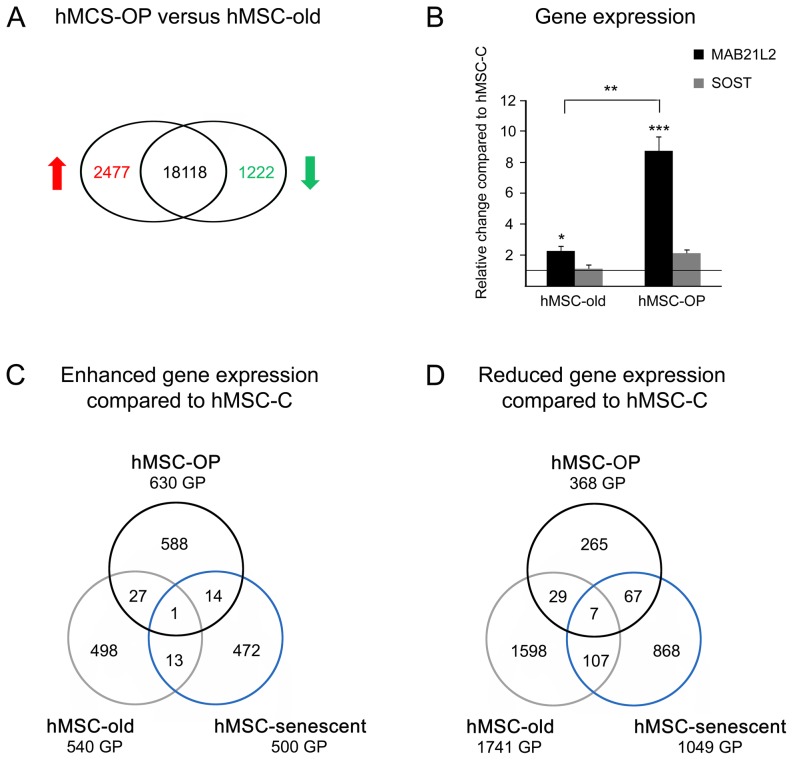

In this study, we compared the transcriptome of hMSC from 5 patients (79–94 years old) suffering from primary osteoporosis (hMSC-OP) with hMSC of the age-matched control group (hMSC-old; donor age 79–89 years) (Table 1). Genome-wide gene expression patterns were examined by employing microarray hybridizations; the obtained data was compared by SAM method (GEO accession number GSE35958). Fold changes (FC) in gene expression were regarded as significant at a threshold of at least 2fold and a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 10%. We detected 2477 gene products with higher and 1222 gene products with reduced expression in osteoporotic hMSC-OP in comparison to non-osteoporotic hMSC-old (Figure 1A, Table S1).

Table 1. Human MSC populations used for microarray hybridization.

| hMSC group | hMSC-C | hMSC-OP | hMSC-old | hMSC-senescent |

| Donors (n) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Average donor age (years) | 57.6±9.56 | 86.2±5.89 | 81.75±4.86 | 56.4±8.96 |

| Donors showed signs of osteoporosis | no | yes | no | no |

| Gender | 4x f, 1x m | 5x f | 3x f, 1x m | 3x f, 2x m |

| RNA of hMSC used in passage | 4x P1, 1x P2 | 4x P1, 1x P2 | P1 | Px |

hMSC-C = control hMSC; hMSC-OP = osteoporotic hMSC; hMSC-old = hMSC of non-osteoporotic, elderly donors; hMSC-senescent = long term-cultivated hMSC in the state of replicative senescence; standard deviations are indicated by ±; n = number; f = female; m = male; P = passage; Px = senescent passage.

Figure 1. Differential gene expression of osteoporotic and aged hMSC.

(A) Microarray comparison of hMSC-OP of elderly patients suffering from primary osteoporosis to age-matched control group hMSC-old. The numbers indicate the number of gene products with enhanced expression (red) and reduced expression (green) in hMSC-OP (for gene names see Table S1). Black numbers mark expressed gene products without significant change in expression. (B) Quantitative PCR of relative change in gene expression of SOST (Sclerostin) and MAB21L2 (Mab-21-like 2) in hMSC-old and osteoporotic hMSC-OP in comparison to hMSC-C. Complementary DNA of hMSC-OP of patients suffering from primary osteoporosis (n = 12, including 4 samples also used for microarray hybridization; age 84.2±6.3), hMSC-old from non-osteoporotic donors of advanced age (n = 13, including 4 samples also used for microarray hybridization; age 82.3±3.6) and hMSC-C of middle-aged, healthy donors (n = 11, including one sample also used for microarray hybridization; age 41.6±2.6) was used. Asterisks indicate significant differences as analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). (C–D) Comparison of differential gene expression patterns of hMSC-OP, hMSC-old and hMSC-senescent when compared to hMSC-C of middle-aged, healthy donors by microarray analyses. The numbers indicate the number of gene products (GP) with significantly enhanced (C) or reduced (D) expression, respectively (for gene names see Table S2).

Osteoporosis as a polygenetic disease has been studied intensively on gene level, resulting in the detection of gene loci and polymorphisms associated with low bone mineral density (BMD), osteoporosis and fracture risk. In contrast to these approaches, our data represents the effects of both genetic and epigenetic changes in hMSC during the development of osteoporosis.

To see if our results coincide at least partly with the genes associated to BMD by specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and copy number variations, we searched the NCBI data base for genome-wide association studies, meta-analyses and candidate gene association studies. The genes listed in these studies were compared to all gene products differentially expressed in the approach hMSC-OP versus hMSC-old.

We identified enhanced expression of 39 genes in hMSC-OP and reduced expression of 16 genes that are already described as reliable or promising candidates for osteoporosis, including susceptibility genes like LRP5, SPP1 (Osteopontin), COL1A1 and SOST (Table 2).

Table 2. Differentially expressed genes in hMSC-OP in comparison to hMSC-old with known association to BMD or fracture risk.

| Symbol | Gene name | Probeset ID | FC | FDR (%) | Reference |

| Enhanced expression in hMSC-OP | |||||

| AAS | achalasia, adrenocortical insufficiency, alacrimia | 218075_at | 3.57 | 0.08 | [58] |

| ANKH | ankylosis, progressive homolog | 223094_s_at | 3.60 | 0.26 | [27] |

| 1560369_at | 3.40 | 0.35 | |||

| ARHGAP1 | Rho GTPase activating protein 1 | 216689_x_at | 7.06 | 0.00 | [58] |

| ASPH | aspartate beta-hydroxylase | 205808_at | 7.80 | 0.00 | [28] |

| ASXL2 | additional sex combs like 2 | 1555266_a_at | 9.07 | 0.00 | [59] |

| 218659_at | 2.39 | 0.33 | [59] | ||

| CAMK1G | calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IG | 217128_s_at | 2.45 | 0.44 | [60] |

| CKAP5 | cytoskeleton associated protein 5 | 1555278_a_at | 2.78 | 0.26 | [58] |

| COL1A1 | collagen, type I, alpha 1 | 217430_x_at | 22.19 | 0.00 | [27] |

| CRTAP | cartilage associated protein | 1554464_a_at | 2.44 | 0.86 | [61] |

| CUL7 | cullin 7 | 203558_at | 4.09 | 0.00 | [28] |

| 241747_s_at | 3.41 | 0.35 | |||

| 36084_at | 3.07 | 0.08 | |||

| DBP | D site of albumin promoter (albumin D-box) binding protein | 209782_s_at | 2.87 | 2.45 | [27] |

| DIO2 | deiodinase, iodothyronine, type II | 231240_at | 4.48 | 0.00 | [62] |

| DMWD | dystrophia myotonica, WD repeat containing | 213231_at | 4.11 | 0.26 | [59] |

| 33768_at | 3.11 | 0.23 | |||

| 1554429_a_at | 2.71 | 0.19 | |||

| E2F7 | E2F transcription factor 7 | 241725_at | 2.21 | 0.86 | [63] |

| ERCC2 | excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 2 | 213468_at | 2.97 | 0.08 | [59] |

| ERLIN1 | ER lipid raft associated 1 | 202444_s_at | 4.33 | 0.08 | [58] |

| FOXC2 | forkhead box C2 (MFH-1, mesenchyme forkhead 1) | 214520_at | 6.24 | 0.00 | [27] |

| FZD1 | frizzled homolog 1 | 204452_s_at | 2.85 | 0.35 | [27] |

| GSR | glutathione reductase | 205770_at | 2.10 | 2.06 | [64] |

| GSTM1 | glutathione S-transferase mu 1 | 204550_x_at | 3.57 | 0.19 | [64] |

| 215333_x_at | 3.19 | 0.35 | |||

| HMGA2 | high mobility group AT-hook 2 | 1558682_at | 3.33 | 0.63 | [27] |

| HSD11B1 | hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 1 | 205404_at | 2.15 | 9.00 | [65] |

| IBSP | integrin-binding sialoprotein | 207370_at | 9.41 | 0.00 | [29], [66] |

| 236028_at | 4.88 | 0.26 | |||

| KPNA4 | karyopherin alpha 4 (importin alpha 3) | 209653_at | 4.04 | 0.19 | [58] |

| LRP5 | low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 | 209468_at | 3.54 | 0.33 | [27] |

| MRPL2 | mitochondrial ribosomal protein L2 | 218887_at | 2.07 | 0.73 | [28] |

| ND2 | mitochondrially encoded NADH dehydrogenase 2 (MTND2) | 1553551_s_at | 2.66 | 0.14 | [67] |

| PDE7B | phosphodiesterase 7B | 220343_at | 3.39 | 0.55 | [28] |

| PRR16 | proline rich 16 | 1554867_a_at | 2.12 | 2.72 | [68] |

| PTPRD | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, D | 213362_at | 3.07 | 3.21 | [69] |

| 205712_at | 2.91 | 1.67 | |||

| RARG | retinoic acid receptor, gamma | 204189_at | 3.85 | 0.26 | [58] |

| RERE | arginine-glutamic acid dipeptide (RE) repeats | 221643_s_at | 5.26 | 0.00 | [27] |

| RUNX2 | runt-related transcription factor 2 | 216994_s_at | 11.86 | 0.00 | [27] |

| SIX5 | SIX homeobox 5 | 229009_at | 2.69 | 0.26 | [59] |

| SOST | sclerostin | 223869_at | 4.60 | 1.00 | [27] |

| SOX4 | SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 4 | 201418_s_at | 2.23 | 2.72 | [29] |

| SP1 | Sp1 transcription factor | 1553685_s_at | 4.19 | 0.08 | [58] |

| 214732_at | 3.49 | 0.35 | |||

| SPP1 | secreted phosphoprotein 1 | 209875_s_at | 2.53 | 4.15 | [70] |

| TBC1D1 | TBC1 (tre-2/USP6, BUB2, cdc16) domain family, member 1 | 1568713_a_at | 4.11 | 0.35 | [58] |

| Reduced expression in hMSC-OP | |||||

| CTNNB1 | catenin (cadherin-associated protein), beta 1, 88 kdf | 201533_at | 0.44 | 1.67 | [66] |

| 1554411_at | 0.23 | 0.23 | |||

| FAM3C | family with sequence similarity 3, member C | 236316_at | 0.44 | 9.00 | [27] |

| FBXL17 | F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 17 | 227203_at | 0.32 | 0.55 | [68] |

| FGF14 | fibroblast growth factor 14 | 230231_at | 0.50 | 5.82 | [68] |

| FGFR2 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 | 208229_at | 0.20 | 0.73 | [70] |

| IFNAR2 | interferon (alpha, beta and omega) receptor 2 | 204786_s_at | 0.43 | 2.72 | [71] |

| ITIH5 | inter-alpha (globulin) inhibitor H5 | 1553243_at | 0.30 | 2.72 | [69] |

| JAG1 | Jagged 1 (Alagille syndrome) | 231183_s_at | 0.33 | 2.06 | [72] |

| NHS | Nance-Horan syndrome | 242800_at | 0.38 | 2.72 | [28] |

| PLCL1 | phospholipase C-like 1 | 205934_at | 0.25 | 5.82 | [27] |

| PTN | pleiotrophin | 211737_x_at | 0.49 | 6.81 | [70] |

| 209465_x_at | 0.46 | 5.82 | |||

| PTPRM | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, M | 1555578_at | 0.47 | 6.81 | [28] |

| RAPGEF4 | Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 4 | 205651_x_at | 0.46 | 3.67 | [69] |

| SERPINE2 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 2 | 227487_s_at | 0.44 | 4.93 | [28] |

| SFRP4 | secreted frizzled-related protein 4 | 204052_s_at | 0.26 | 3.67 | [73] |

| SMAD1 | SMAD family member 1 | 227798_at | 0.47 | 3.21 | [71] |

FC = fold change; FDR = false discovery rate.

Effects of osteoporosis are independent of clock-driven aging

One of the main risk factors for developing primary osteoporosis is advanced age. Therefore, in the next step, we focused on gene expression patterns that were identical in hMSC-OP of elderly patients suffering from osteoporosis and hMSC-old of non-osteoporotic, elderly donors. As a new control group for microarray comparisons, we used hMSC of middle-aged donors (hMSC-C; donor age 42–67 years).

In the comparison of hMSC-OP versus hMSC-C (GEO accession number GSE35956) we detected 630 gene products with higher and 368 gene products with reduced expression due to osteoporosis and advanced donor age. By comparing hMSC-old with hMSC-C (GEO accession number GSE35955) we obtained gene expression changes due to advanced age per se and found enhanced expression of 540 gene products and decreased expression of 1741 gene products in hMSC-old.

Due to the fact that we used hMSC-C as a control in both SAM approaches we could compare the differentially gene expression patterns of hMSC-OP and hMSC-old (Figure 1C and D). Surprisingly we detected a minority of 28 gene products with enhanced and 36 gene products with reduced expression in both approaches (for gene names see Table S2).

One of the genes that was enhanced expressed due to osteoporosis but also due to advanced age was MAB21L2 with FC[hMSC-old versus hMSC-C] = 2.7 and FC[hMSC-OP versus hMSC-C] = 14.4. By performing qPCR analysis with up to 13 samples per hMSC group we confirmed that the expression of MAB21L2 is significantly higher in osteoporotic hMSC-OP than in hMSC-old when compared to hMSC-C of the middle-aged control group (Figure 1B).

In contrast, SOST, the gene coding for Sclerostin, is not associated with advanced age (no significant FC), but both microarray analysis (FC[hMSC-OP versus hMSC-C] = 7.3) and qPCR revealed the enhanced expression of the gene in osteoporotic hMSC-OP (Figure 1B).

Osteoporotic stem cells show few signs of replicative senescence

Because donors of osteoporotic cells were of highly advanced age (79+ years old) and due to the hypothesis that aging is caused by stem cells losing their self-renewal capacity due to replication limits, we investigated whether hMSC-OP showed any signs of replicative senescence. Therefore, we performed long-term cultivation of hMSC from healthy donors of medium age (42–64 years old) until they entered senescence (hMSC-senescent), proved by proliferation stop and positive senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining (data not shown).

Microarray analyses of hMSC in senescent passage Px revealed 500 gene products with enhanced and 1049 gene products with reduced expression when compared to the previously used control group hMSC-C of early passages (GEO accession number GSE35957).

By using hMSC-C as control cells for all three SAM datasets we could compare the differential gene expression pattern of hMSC-OP, hMSC-old and hMSC-senescent to find parallels in gene expression. We detected small overlap for gene products with enhanced expression when comparing hMSC-OP with hMSC-senescent (15) and hMSC-old with hMSC-senescent (14) (Figure 1C). More senescence-associated gene products were found reduced expressed in hMSC-old (114) and hMSC-OP (74) (Figure 1 D, Table S2). Few genes were differentially expressed in all three datasets: TMEFF1 showed induced expression, whereas MED13L, ANLN, ZWILCH, CMPK2, DDX17, MCM2 and MCM8 showed diminished expression in hMSC-OP, hMSC-old and hMSC-senescent when compared to hMSC-C.

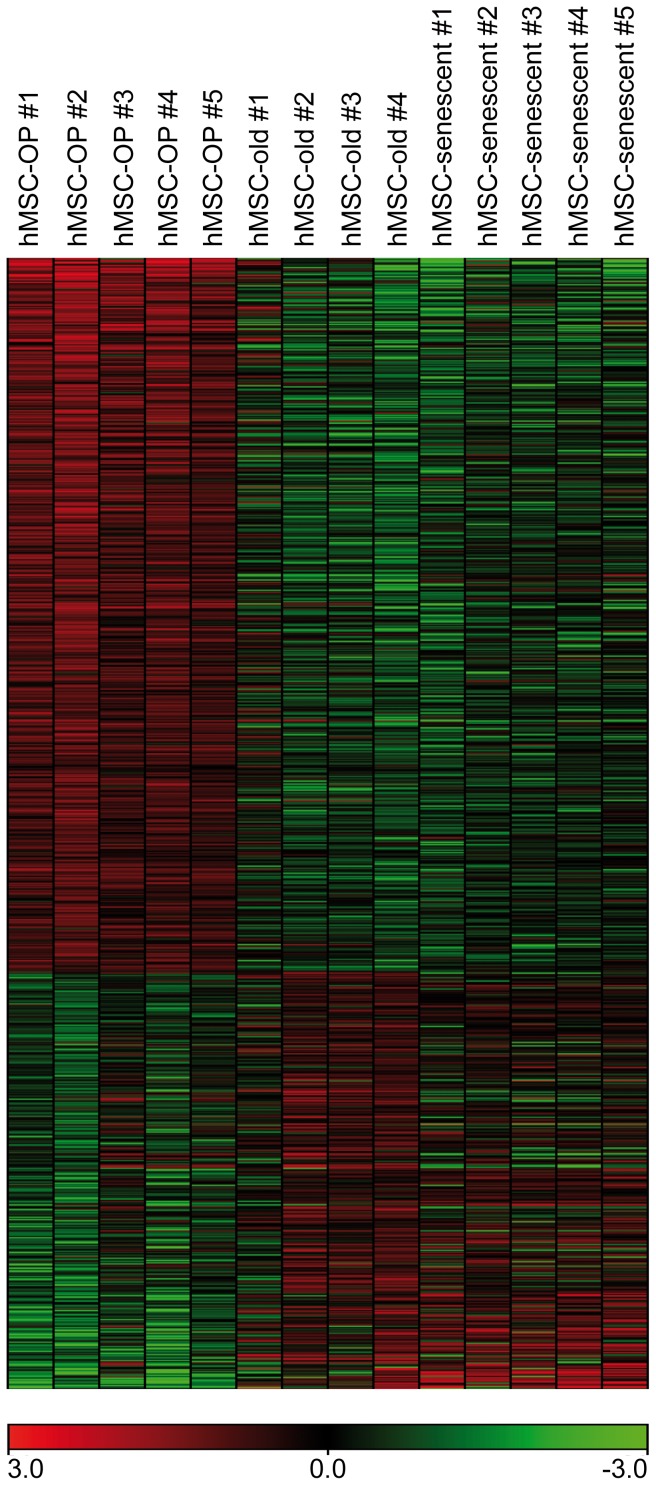

By generating a heat map for gene products at least 2fold differentially expressed in hMSC-OP compared to hMSC-C we could highlight the difference between hMSC-OP, hMSC-old and hMSC-senescence (Figure 2). Osteoporotic cells exhibit a distinct gene expression profile independent of both clock-driven aging and cellular aging.

Figure 2. Heat map of microarray results of osteoporotic and aged hMSC.

Color-coded microarray hybridization signals (green to red = low to high signals) of hMSC-OP, hMSC-old and hMSC-senescent. The 998 gene products depicted showed at least 2fold differential gene expression (630 enhanced, 368 reduced; FDR<10%) in SAM comparison of hMSC-OP versus hMSC-C (for gene names see Table S2).

Relevance of transcriptional changes for stem cell function

To unravel if changes in gene expression profile could cause deficiencies in cellular processes we carried out gene function and pathway identifications by Gene Ontology classification and by searching within the NCBI database for literature. By comparing functions of genes differentially expressed in hMSC-OP, hMSC-old and hMSC-senescent when compared to hMSC-C we detected differences in the effect of osteoporosis, age and senescence on stem cell characteristics. Hereby we focused on genes with known relevance in the following 4 processes: (1) osteoblastogenesis, (2) osteoclastogenesis, (3) proliferation and (4) DNA repair (Table 3). These categories play important roles in sustaining bone homeostasis by influencing bone formation, bone resorption and self-renewal of stem cells.

Table 3. Functional clustering of differentially expressed genes of hMSC-OP, hMSC-old and hMSC-senescent when compared to hMSC-C.

| Symbol | Gene name | hMSC-OP | hMSC-old | hMSC-senescent | Reference | ||||||

| (1) Osteoblastogenesis | |||||||||||

| positive | |||||||||||

| PTH1R | parathyroid hormone 1 receptor | ↑ | [74] | ||||||||

| IBSP | integrin-binding sialoprotein | ↑ | [75] | ||||||||

| INHA | inhibin, alpha | ↑ | [76] | ||||||||

| IGFBP2 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 | ↑ | [77] | ||||||||

| IGF2 | insulin-like growth factor 2 | ↑ | ↓ | [77] | |||||||

| VEGFB | vascular endothelial growth factor B | ↑ | ↓ | [78] | |||||||

| VEGFA | vascular endothelial growth factor A | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [78] | ||||||

| FOXC2 | forkhead box C2 (MFH-1, mesenchyme forkhead 1) | ↑ | ↓ | [79] | |||||||

| COL1A1 | collagen, type I, alpha 1 | ↓ | [75] | ||||||||

| RUNX2 | runt-related transcription factor 2 | ↓ | [75] | ||||||||

| ANKH* | ankylosis, progressive homolog | ↓ | ↓ | [80] | |||||||

| SMAD3B | SMAD family member 3 | ↓ | [81] | ||||||||

| SPP1 | secreted phosphoprotein 1 | ↓ | [75] | ||||||||

| EFNB2 | ephrin-B2 | ↓ | [82] | ||||||||

| ALPL | alkaline phosphatase, liver/bone/kidney | ↓ | [80] | ||||||||

| CYP2R1 | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily R, polypeptide 1 | ↓ | [80], [83] | ||||||||

| FOXC1 | forkhead box C1 | ↑ | ↓ | [84] | |||||||

| IL6ST | interleukin 6 signal transducer (Oncostatin M receptor) | ↓ | ↑ | [85] | |||||||

| PDGFA | platelet-derived growth factor alpha polypeptide | ↑ | [11] | ||||||||

| VDR | vitamin D receptor | ↑ | [80] | ||||||||

| FGFR2* | fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 | ↑ | ↓ | [86] | |||||||

| BMP6B | bone morphogenetic protein 6 | ↑ | [11] | ||||||||

| ROR1W | receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1 | ↓ | ↑ | [87] | |||||||

| ANKRD6W | ankyrin repeat domain 6 | ↑ | [16], [18] | ||||||||

| negative | |||||||||||

| TGFB1 | transforming growth factor, beta 1 | ↑ | ↓ | [88] | |||||||

| MAB21L2B | mab-21-like 2 | ↑ | ↑ | [15] | |||||||

| FST | follistatin | ↑ | ↑ | [89], [90] | |||||||

| FSTL3 | follistatin-like 3 | ↑ | [91] | ||||||||

| KREMEN1W | kringle containing transmembrane protein 1 | ↑ | [38] | ||||||||

| SOSTW B | sclerostin | ↑ | [23] | ||||||||

| FGFR1 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 | ↑ | [92] | ||||||||

| IGFBP5 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 | ↑ | ↑ | [11] | |||||||

| IGFBP4 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 4 | ↓ | [11] | ||||||||

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor | ↓ | [93] | ||||||||

| GREM2B | gremlin 2, cysteine knot superfamily, homolog | ↓ | ↓ | [94] | |||||||

| NOGB | noggin | ↑ | [11] | ||||||||

| CTNNB1W | catenin, beta 1 | ↑ | [17], [18] | ||||||||

| SFRP4W | secreted frizzled-related protein 4 | ↑ | [95] | ||||||||

| WNT2W | wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 2 | ↑ | [17], [18] | ||||||||

| WNT3W | wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 3 | ↑ | [17], [18] | ||||||||

| (2) Osteoclastogenesis | |||||||||||

| positive | |||||||||||

| PTH1R | parathyroid hormone 1 receptor | ↑ | [25] | ||||||||

| CSF1 | colony stimulating factor 1 | ↑ | [4] | ||||||||

| PTGS2 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | ↑ | ↓ | [96] | |||||||

| IGF2 | insulin-like growth factor 2 | ↑ | ↓ | [97] | |||||||

| TNFSF11 | tumor necrosis factor superfamily, member 11 | ↓ | [98] | ||||||||

| SPP1 | secreted phosphoprotein 1 | ↓ | [99] | ||||||||

| IL7 | interleukin 7 | ↓ | [100] | ||||||||

| THBS1 | thrombospondin 1 | ↑ | [101] | ||||||||

| IL1A* | interleukin 1, alpha | ↓ | ↑ | [67] | |||||||

| TNFSF10 | tumor necrosis factor superfamily, member 10 | ↓ | ↓ | [102] | |||||||

| TGFB2 | transforming growth factor, beta 2 | ↓ | ↓ | [103] | |||||||

| VEGFA | vascular endothelial growth factor A | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [46] | ||||||

| VEGFB | vascular endothelial growth factor B | ↑ | ↓ | [46] | |||||||

| TGFB1 | transforming growth factor, beta 1 | ↑ | ↓ | [47] | |||||||

| RUNX2 | runt-related transcription factor 2 | ↓ | [104] | ||||||||

| negative | |||||||||||

| TNFRSF11B | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 11b | ↑ | [98] | ||||||||

| FSTL3 | follistatin-like 3 | ↑ | [105] | ||||||||

| (3) Proliferation | |||||||||||

| positive | |||||||||||

| HMMR | hyaluronan-mediated motility receptor | ↓ | ↓ | [49] | |||||||

| HELLS | helicase, lymphoid-specific | ↓ | [106] | ||||||||

| PTN | pleiotrophin | ↓ | [107] | ||||||||

| SOD2 | superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial | ↓ | ↑ | [108] | |||||||

| CCNB2 | cyclin B2 | ↓ | [109] | ||||||||

| CDC2 | cell division cycle 2, G1 to S and G2 to M | ↓ | ↓ | [109] | |||||||

| CCNA2 | cyclin A2 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [109] | ||||||

| CCNE2 | cyclin E2 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [109] | ||||||

| CCNF | cyclin F | ↓ | [110] | ||||||||

| CCND1 | cyclin D1 | ↑ | [109] | ||||||||

| CCND2 | cyclin D2 | ↑ | [109] | ||||||||

| CDC25A | cell division cycle 25 homolog A | ↓ | [111] | ||||||||

| CDC25B | cell division cycle 25 homolog B | ↓ | [112] | ||||||||

| CDC25C | cell division cycle 25 homolog C | ↓ | [113] | ||||||||

| CDK2 | cyclin-dependent kinase 2 | ↓ | [109] | ||||||||

| negative | |||||||||||

| PSG1 | pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein 1 | ↑ | [114] | ||||||||

| PSG2 | pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein 2 | ↑ | [114] | ||||||||

| PSG3 | pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein 3 | ↓ | ↑ | [114] | |||||||

| PSG4 | pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein 4 | ↑ | [114] | ||||||||

| PSG6 | pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein 6 | ↑ | [114] | ||||||||

| PSG7 | pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein 7 | ↑ | [114] | ||||||||

| ARHGAP29 | Rho GTPase activating protein 29 | ↓ | ↑ | [107] | |||||||

| CDKN2A | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | ↑ | [107] | ||||||||

| CDKN1A | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A | ↑ | [50] | ||||||||

| (4) DNA-repair | |||||||||||

| positive | |||||||||||

| POLD1 | polymerase (DNA directed), delta 1, catalytic subunit 125kDa | ↓ | [115] | ||||||||

| POLE2 | polymerase (DNA directed), epsilon 2 (p59 subunit) | ↓ | ↓ | [115] | |||||||

| POLQ | polymerase (DNA directed), theta | ↓ | [115] | ||||||||

| POLH | polymerase (DNA directed), eta | ↓ | [115] | ||||||||

| POLK | polymerase (DNA directed) kappa | ↓ | [115] | ||||||||

| MRE11A | MRE11 meiotic recombination 11 homolog A | ↓ | [116] | ||||||||

| PARP3 | poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase family, member 3 | ↓ | [117] | ||||||||

| RAD50 | RAD50 homolog | ↓ | [116] | ||||||||

| RAD51 | RAD51 homolog | ↓ | [116] | ||||||||

| RAD51AP1 | RAD51 associated protein 1 | ↓ | ↓ | [118] | |||||||

| TOP2A | topoisomerase (DNA) II alpha 170 kDa | ↓ | ↓ | [119] | |||||||

| EXO1 | exonuclease 1 | ↓ | [116] | ||||||||

| CHEK1 | CHK1 checkpoint homolog | ↓ | [120] | ||||||||

| HMGB2 | high-mobility group box 2 | ↓ | [121] | ||||||||

arrows pointing downward = at least 2fold reduced expression in comparison to hMSC-C; arrows pointing upward = at least 2fold enhanced expression in comparison to hMSC-C;

= gene associated with WNT signaling;

= gene associated with BMP signaling;

= probesets that refer to the gene are not identical in the indicated comparisons.

In hMSC-OP we found enhanced expression of gene products with relevance in osteoblastogenesis by autocrine and paracrine stimulation, respectively (PTH1R, IBSP, IGF2, VEGFA and VEGFB). In senescent hMSC and hMSC-old we detected reduced expression of genes coding for enhancers of osteoblast differentiation and matrix mineralization (SPP1, ALPL, EFNB2, COL1A1, RUNX2 and ANKH).

Genes coding for inhibitors of WNT signaling (SOST, KREMEN1) showed enhanced expression in hMSC-OP in comparison to hMSC-C, whereas activators of canonical WNT signaling that indirectly inhibit osteogenic differentiation by augmenting proliferation, were more highly expressed in in vitro- aged and senescent hMSC (WNT2, WNT3, CTNNB1). Next to MAB21L2, which codes for a repressor of BMP-induced transcription, another negative regulator of osteoblastogenesis was enhanced expressed in hMSC-OP and hMSC-old: Follistatin (FST), which is associated with inhibition of Activin.

Genes linked to bone resorption were differentially expressed in all three hMSC groups with senescent cells exhibiting strongly diminished potential for inducing osteoclastogenesis by decreased expression of secreted ligands (TGFB, VEGF, IL7, IL1A) and other stimulators like TNFSF11 (RANKL). The gene coding for the osteoclast inhibitor Osteoprotegerin (TNFRSF11B) was expressed to a higher extent in hMSC-senescent. In vivo-aged hMSC-old showed a similar gene expression pattern whereas osteoporotic hMSC-OP revealed enhanced expression of genes indirectly (PTH1R, PTGS2 and IGF2) as well as directly (CSF1, VEGFA and VEGFB) involved in promoting osteoclast formation.

By examining the expression of genes related to proliferation we found a substantial number of repressed genes that code for proteins important for cell division, like several Cyclins, CDC2 and CDC25 proteins in hMSC-senescent. Markers for cellular senescence and genes described as mediators of cell cycle were also differentially expressed in these cells, e.g. CDKN2A (P16), several PSG, PTN, ARHGAP29 (PARG1), HMMR and HELLS. Clock-driven aging and osteoporosis showed less negative effects on proliferative capacity of stem cells, but in hMSC-OP the expression of a second well known marker of replicative senescence – besides P16 – was increased: CDKN1A, which codes for P21.

DNA repair is one of the reasons for cell cycle arrest at the G1, S or G2 checkpoints of mitosis to prevent the accumulation of DNA damage or mutations that could result in tumor development. Again hMSC-senescent exhibited the most severe deficiencies with a diminished expression of genes involved in DNA repair like TOP2A, EXO1 and several DNA polymerases. Osteoporotic and aged hMSC showed minor changes.

Discussion

During aging, a continuous decrease in bone mass and bone density occurs and peaks in the development of primary osteoporosis in one of three women and one of eight men over the age of 50 [2], [27]. Induced by a variety of risk factors like advanced age, loss of sex steroid production and unhealthy life style [2], [3], [34], recent research has largely unraveled the polygenetic nature and the multifaceted pathophysiology of this syndrome [27], [29], [35]. Hitherto, approaches for studying the disease mostly consisted of whole genome association studies of BMD-associated gene loci as well as of manipulating expression of candidate genes in animal models or cells in vitro, followed by characterization of phenotypes [36], [37], [38]. However, bone loss associated with increasing age is a continuous process not only caused by gene polymorphisms but very likely also by epigenetic modulations of gene expression changes that accompany aging [39]. So far, analyses of these changes in primary cells of osteoporotic patients or in whole bone samples have been almost neglected.

We analyzed the effect of primary osteoporosis on the source of bone regeneration and performed microarray hybridizations of hMSC of elderly patients suffering from severe osteoporosis (hMSC-OP) and of donors of advanced age without any indication for the syndrome (hMSC-old). We detected several genes connected to BMD with either reduced (16) or increased (39) expression in hMSC-OP including well-investigated susceptibility genes like LRP5, SPP1 (Osteopontin), COL1A1 and SOST (Table 2) [27]. The latter codes for the osteocyte-specific protein Sclerostin, which acts as a WNT antagonist and is also controversially discussed as a BMP inhibitor [20], [22], [23]. Upon release, the protein inhibits proliferation of MSC and osteoblasts, blocks osteogenic differentiation and even induces apoptosis in osteoblasts [23], [40]. Direct connections between the protein and osteoporosis have already been described: serum levels of Sclerostin were found enhanced in postmenopausal women [41] and one of the upcoming treatments for osteoporosis is the application of anti-Sclerostin-antibodies [24], [42]. It is conceivable that the premature expression of SOST in osteoporotic stem cells auto-inhibits proliferation and self-renewal of hMSC-OP and thereby leads to the reduced ratios of formation to resorption observed in primary osteoporosis [43].

Furthermore we also found higher expression of MAB21L2 (Mab-21-like 2) in hMSC-OP in comparison to hMSC-old. QPCR revealed that, even though the expression was induced by advanced donor age itself, the transcription of MAB21L2 was even more triggered in osteoporotic stem cells (Figure 1B). In Xenopus laevis gastrulae it was shown that MAB21L2 antagonizes the effects of BMP4 by repressing the BMP-induced gene expression. The nuclear protein binds SMAD1, the transducer of BMP2/4/7 signaling, but so far it is still unknown if MAB21L2 exerts its effects in a DNA-binding or a non-binding fashion [15]. Our data of age- and osteoporosis-induced expression of MAB21L2 in hMSC made us hypothesize that BMP-signaling in stem cells is less effective in advanced age and even less so in primary osteoporosis due to transcriptional repression of BMP-target genes.

Despite high inter-individual variability in the gene expression level, as demonstrated in our heat map (Figure 2), we could validate the microarray results for both SOST and MAB21L2 in qPCR analysis with up to 13 different hMSC-OP and hMSC-old populations. We hereby demonstrate the reliability of our microarray approach, which was performed with a comparably low number of samples. Being inhibitors of WNT and BMP signaling, our two leading candidates are major hubs in blocking differentiation programs right at the beginning. Hereby, our data support the results of Rodriguez et al. and Dalle Carbonare et al., who demonstrated in vitro that osteoporotic hMSC exhibit diminished osteogenic differentiation potential [44], [45]. Future research will have to unravel how many of the genes differentially expressed in osteoporotic hMSC-OP (Table S1) are downstream SOST or MAB21L2 over-expression.

Furthermore, we detected indications for osteoporotic stem cells actively enhancing osteoclastogenesis and therefore bone resorption. Besides the enhanced expression of genes coding for osteoclast stimulating ligands, e.g. VEGF, TGFB and CSF1 [4], [46], [47], we also detected the osteoporosis-induced expression of Parathyroid hormone receptor PTH1R. Activation of PTH1R triggers osteoblast maturation and induces RANKL expression which leads to osteoclast precursor differentiation and activation [26]. The enhanced expression of osteoclastogenesis promoting factors has already been described in fragility fractured bone [48] and is in general consistent with the enhanced bone resorption described for osteoporosis [2].

Because high age is one of the main risk factors for developing osteoporosis, we tried to dissect effects of aging from effects of primary osteoporosis by using hMSC from middle-aged donors as control cells (hMSC-C) for comparisons with hMSC-OP and hMSC-old, respectively, of elderly individuals (Figure 1C and 1D, Table S2). Surprisingly, the patterns of the differential gene expression in aged and osteoporotic hMSC differed widely. Only a few gene products with identical expression profiles in hMSC-old and hMSC-OP were observed and we therefore conclude that osteoporosis-associated changes are very distinct and independent of effects of clock-driven aging. We hypothesize that donors of advanced age who suffered from osteoarthritis but not from osteoporosis, aged in a healthier way than osteoporotic patients, or vice versa that osteoporosis is a distinct syndrome of premature aging.

One hypothetical reason for aging is the loss of tissue regeneration due to replicative senescence of stem cells, which accumulates over time and ends in organ failure and death of the organism [33]. Due to the fact that donors of hMSC-OP were of advanced age we analyzed whether these cells exhibited signs of replicative senescence by comparing them to the gene expression pattern of long term-cultivated, senescent hMSC. Thereby we detected a small overlap of genes differentially expressed in hMSC-OP and hMSC-senescent when compared to the identical control group hMSC-C (Figure 1C and D). Despite the distinct gene expression pattern, we found some markers for replicative senescence in osteoporotic hMSC-OP, like the reduced expression of Hyaluronan receptor HMMR, which was described as inversely regulated to tumor suppressor P53 [49], and the induction of CDKN1A, which codes for P21, another inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases (Table 3) [50]. In contrast, analyses of non-osteoporotic hMSC-old of the age-matched donor group revealed no expression of markers for senescence and highlighted even more the differences between aging with and without primary osteoporosis. Our findings suggest that osteoporotic stem cells exhibit deficiencies in proliferation and might already be prone to a pre-senescent state. So far, reduction in proliferative activity in osteoporotic cells has only been described for osteoblasts [51], [52]. For confirmation, more detailed investigations of hMSC-OP on protein level and by proliferation or senescence studies are needed.

In summary, this study indicates that intrinsic alterations in stem cell biology are involved in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis. By microarray analyses, we detected significant differences between hMSC of elderly donors with and without osteoporosis, suggesting that primary osteoporosis causes distinct transcriptional changes, which differ from age-related changes in non-osteoporotic donors. Next to indications for a pre-senescent state we detected enhanced transcription of inhibitors of WNT and BMP signaling in osteoporotic hMSC-OP, which can lead to functional deficiencies, such as autoinhibition of osteogenic differentiation and loss of self-renewal. Our data facilitate the importance of well-known susceptibility genes of osteoporosis such as SOST, COL1A1 and LRP5, and additionally, we detected new candidate genes for further investigations, e.g. MAB21L2. Our study confirms that disturbed bone homeostasis by inhibition of osteogenic regeneration is at least an equally important feature of primary osteoporosis besides enhanced bone resorption. Therefore, “inhibition of inhibitors” of bone regeneration by using, e.g. SOST antibodies, is a mechanistically plausible treatment of the syndrome and will get even more attention in the future.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Bone material was used under agreement of the local Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Wuerzburg with written informed consent of each patient.

Cell culture

Human MSC of non-osteoporotic donors were obtained from bone marrow of femoral heads according to the described protocol [53] after total hip arthroplasty due to osteoarthritis and/or hip dysplasia. MSC of patients suffering from osteoporosis were isolated from femoral heads after low-energy fracture of the femoral neck. Additional criteria for confirming primary osteoporosis in these donors were vertebrae fractures and advanced age.

Cell culture medium, fetal calf serum (FCS), trypsin-EDTA and antibiotics were obtained from PAA Laboratories GmbH, Linz, Austria. Human MSC were selected by surface adherence and expanded in DMEM/Ham's F-12 (1∶1) medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 1 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 50 µg/ml L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma Aldrich GmbH, Schnelldorf, Germany).

For long term cultivation, cells were expanded at 70–90% confluence by trypsinization with 1× trypsin-EDTA and reseeding in a ratio of 1∶3. This procedure was repeated for up to x passages when the hMSC did not become confluent within 3 weeks due to replicative senescence.

RNA isolation

At 80–90% confluence human MSC monolayers were lysed directly in the cell culture flask in passage (P) 1 or 2 and the last, senescent passage Px, respectively. Total RNA was isolated using the NucleoSpin RNA II Purification Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions including DNase digestion.

Microarray analysis

For microarray analyses total RNA of hMSC-C, hMSC-senescent and hMSC-OP (Table 1) was amplified and labeled according to the GeneChip One-Cycle cDNA Synthesis Kit (Affymetrix, High Wycombe, United Kingdom). Total RNA of hMSC-old was amplified and labeled according to the Affymetrix GeneChip 3′IVT Express Kit. Following fragmentation, 10 µg of cRNA were hybridized for 16 hr at 45°C on Affymetrix GeneChips Human Genome U133_Plus_2.0. GeneChips were washed and stained in the Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450 using the Affymetrix Hybridization, Wash and Stain Kit. Hybridization signals were detected with Affymetrix Gene Chip Scanner 3000 and global scaling was performed by Affymetrix GeneChipOperatingSoftware 1.4 using the MAS5 algorithm. Microarray data of all 4 hMSC groups have been published in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through GEO superSeries accession number GSE35959. Gene expression patterns of two groups of hMSC populations were compared with the significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) approach by using the SAM software of Stanford University, Palo Alto, USA (http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/SAM/) [54]. For data interpretation we only took those gene products into account that provided present hybridization signals in at least 3 of x hMSC populations in at least one of the two groups compared. Furthermore, only gene products (probesets) with fold changes (FC) ≤0.5 or ≥2.0, and a false discovery rate (FDR) <10% were considered as significantly, differentially expressed.

Heat maps were generated by CARMAweb using globally normalized data [55].

Differentially expressed gene products were assigned to protein function by Gene Ontology classification (http://www.geneontology.org/) and NCBI PubMed literature search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez). Genes with at least one differentially expressed probeset were taken into account.

Additionally, SAM data was compared to publically available data from genome-wide association studies, meta-analyses or candidate gene association studies obtained by a NCBI PubMed search for reviews and original publications from 2010 and later with the following search terms: genome-wide association/polymorphism/meta-analysis+osteoporosis or+bone mineral density.

Quantitative PCR analysis

One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with Oligo(dT)15 primers (peqlab Biotechnologie GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) and MMLV reverse transcriptase (Promega GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed in triplets in 20 µl with 16 ng cDNA, 5 µl KAPA SYBR FAST Universal 2× qPCR Master Mix (peqlab Biotechnologie GmbH) and 0.25 pmol of sequence specific primers obtained from biomers.net GmbH, Ulm, Germany. The following primer sequences were used (5′-3′ forward and reverse, respectively): RPLP0 (ribosomal protein, large, P0) as housekeeping gene (NM_001002.3) [56], TGCATCAGTACCCCATTCTATCAT and AGGCAGATGGATCAGCCAAGA; SOST (NM_025237.2), CAGGCGTTCAAGAATGATGC and TACTCGGACACGTCTTTGGTC; and MAB21L2 (NM_006439.4), TGGGTGCTACAGTTCG and CAGGCAGGAGATGAGC. QPCR was performed with Opticon DNA Engine (MJ Research, Waltham, USA) and the following conditions: 95°C for 3 min; 40 cycles: 95°C for 15 s; 60°C for 15 s; 72°C for 10 s; followed by melting curve analysis. Results were calculated with the ΔΔCT method.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining

To confirm replicative senescence in the last, non-confluent passage of hMSC after long time cultivation, senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining was performed as described [57]. After each passage 2×105 cells were seeded on coverslips in 9.6 cm2 petri dishes and cultured to 70–90% confluence. After fixation in 2% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde for 5 min the coverslips were stored at 4°C. Staining was performed for hMSC in P1and Px simultaneously by incubating the cells for 16 h at 37°C (normal air CO2) with 1 ml staining solution (1 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactosidase (Sigma Aldrich GmbH), 40 mM citric acid/sodium phosphate (pH 6.0), 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM MgCl2). Counterstaining with nuclear fast red was performed after washing twice with ddH2O.

Supporting Information

Gene products with significant expression changes in hMSC-OP compared to hMSC-old. FC = fold change (at least 2fold); FDR = false discovery rate (<10%).

(DOC)

Gene products differentially expressed in hMSC-OP, hMSC-old and hMSC-senescent when compared to hMSC-C. arrows pointing downward = significant, reduced expression in comparison to hMSC-C; arrows pointing upward = significant, enhanced expression in comparison to hMSC-C; FC = fold change (at least 2fold); FDR = false discovery rate (<10%); — = no expression in both hMSC groups compared.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Orthopedic Surgeons U. Nöth and A. Steinert (Wuerzburg, Germany) who supplied us with explanted human femoral heads.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation [FOR793 JA506/9-1](http://www.dfg.de/index.jsp). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Rachner TD, Khosla S, Hofbauer LC (2011) Osteoporosis: now and the future. Lancet 377: 1276–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seeman E (2008) Bone quality: the material and structural basis of bone strength. J Bone Miner Metab 26: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pietschmann P, Rauner M, Sipos W, Kerschan-Schindl K (2009) Osteoporosis: an age-related and gender-specific disease–a mini-review. Gerontology 55: 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manolagas SC (2000) Birth and death of bone cells: basic regulatory mechanisms and implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoporosis. Endocr Rev 21: 115–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khosla S (2001) Minireview: the OPG/RANKL/RANK system. Endocrinology 142: 5050–5055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Misof B, Gamsjaeger S, Cohen A, Hofstetter B, Roschger P, et al. (2012) Bone material properties in premenopausal women with idiopathic osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jilka RL (2003) Biology of the basic multicellular unit and the pathophysiology of osteoporosis. Med Pediatr Oncol 41: 182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duque G (2008) Bone and fat connection in aging bone. Curr Opin Rheumatol 20: 429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valtieri M, Sorrentino A (2008) The mesenchymal stromal cell contribution to homeostasis. J Cell Physiol 217: 296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rawadi G, Vayssiere B, Dunn F, Baron R, Roman-Roman S (2003) BMP-2 controls alkaline phosphatase expression and osteoblast mineralization by a Wnt autocrine loop. J Bone Miner Res 18: 1842–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Canalis E (2009) Growth factor control of bone mass. J Cell Biochem 108: 769–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gazzerro E, Pereira RC, Jorgetti V, Olson S, Economides AN, et al. (2005) Skeletal overexpression of gremlin impairs bone formation and causes osteopenia. Endocrinology 146: 655–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Devlin RD, Du Z, Pereira RC, Kimble RB, Economides AN, et al. (2003) Skeletal overexpression of noggin results in osteopenia and reduced bone formation. Endocrinology 144: 1972–1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Estrada KD, Retting KN, Chin AM, Lyons KM (2011) Smad6 is essential to limit BMP signaling during cartilage development. J Bone Miner Res 26: 2498–2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baldessari D, Badaloni A, Longhi R, Zappavigna V, Consalez GG (2004) MAB21L2, a vertebrate member of the Male-abnormal 21 family, modulates BMP signaling and interacts with SMAD1. BMC Cell Biol 5: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Katoh M (2007) WNT signaling pathway and stem cell signaling network. Clin Cancer Res 13: 4042–4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boland GM, Perkins G, Hall DJ, Tuan RS (2004) Wnt 3a promotes proliferation and suppresses osteogenic differentiation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem 93: 1210–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ling L, Nurcombe V, Cool SM (2009) Wnt signaling controls the fate of mesenchymal stem cells. Gene 433: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cho HH, Kim YJ, Kim SJ, Kim JH, Bae YC, et al. (2006) Endogenous Wnt signaling promotes proliferation and suppresses osteogenic differentiation in human adipose derived stromal cells. Tissue Eng 12: 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krause C, Korchynskyi O, de Rooij K, Weidauer SE, de Gorter DJ, et al. (2010) Distinct modes of inhibition by sclerostin on bone morphogenetic protein and Wnt signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 285: 41614–41626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Bezooijen RL, Svensson JP, Eefting D, Visser A, van der Horst G, et al. (2007) Wnt but not BMP signaling is involved in the inhibitory action of sclerostin on BMP-stimulated bone formation. J Bone Miner Res 22: 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Winkler DG, Sutherland MK, Geoghegan JC, Yu C, Hayes T, et al. (2003) Osteocyte control of bone formation via sclerostin, a novel BMP antagonist. EMBO J 22: 6267–6276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. ten Dijke P, Krause C, de Gorter DJ, Lowik CW, van Bezooijen RL (2008) Osteocyte-derived sclerostin inhibits bone formation: its role in bone morphogenetic protein and Wnt signaling. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90 Suppl 1: 31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ominsky MS, Vlasseros F, Jolette J, Smith SY, Stouch B, et al. (2010) Two doses of sclerostin antibody in cynomolgus monkeys increases bone formation, bone mineral density, and bone strength. J Bone Miner Res 25: 948–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Potts JT (2005) Parathyroid hormone: past and present. J Endocrinol 187: 311–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Datta NS, Abou-Samra AB (2009) PTH and PTHrP signaling in osteoblasts. Cell Signal 21: 1245–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li WF, Hou SX, Yu B, Li MM, Ferec C, et al. (2010) Genetics of osteoporosis: accelerating pace in gene identification and validation. Hum Genet 127: 249–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koller DL, Ichikawa S, Lai D, Padgett LR, Doheny KF, et al. (2010) Genome-wide association study of bone mineral density in premenopausal European-American women and replication in African-American women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 1802–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Duncan EL, Danoy P, Kemp JP, Leo PJ, McCloskey E, et al. (2011) Genome-wide association study using extreme truncate selection identifies novel genes affecting bone mineral density and fracture risk. PLoS Genet 7: e1001372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rivadeneira F, Styrkarsdottir U, Estrada K, Halldorsson BV, Hsu YH, et al. (2009) Twenty bone-mineral-density loci identified by large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 41: 1199–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hayflick L (1965) The Limited in Vitro Lifetime of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp Cell Res 37: 614–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wagner W, Horn P, Castoldi M, Diehlmann A, Bork S, et al. (2008) Replicative senescence of mesenchymal stem cells: a continuous and organized process. PLoS One 3: e2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sethe S, Scutt A, Stolzing A (2006) Aging of mesenchymal stem cells. Ageing Res Rev 5: 91–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kawaguchi H (2006) Molecular backgrounds of age-related osteoporosis from mouse genetics approaches. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 7: 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Richards JB, Kavvoura FK, Rivadeneira F, Styrkarsdottir U, Estrada K, et al. (2009) Collaborative meta-analysis: associations of 150 candidate genes with osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture. Ann Intern Med 151: 528–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Albers J, Schulze J, Beil FT, Gebauer M, Baranowsky A, et al. (2011) Control of bone formation by the serpentine receptor Frizzled-9. J Cell Biol 192: 1057–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schulze J, Seitz S, Saito H, Schneebauer M, Marshall RP, et al. (2010) Negative regulation of bone formation by the transmembrane Wnt antagonist Kremen-2. PLoS One 5: e10309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ellwanger K, Saito H, Clement-Lacroix P, Maltry N, Niedermeyer J, et al. (2008) Targeted disruption of the Wnt regulator Kremen induces limb defects and high bone density. Mol Cell Biol 28: 4875–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, et al. (2005) Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 10604–10609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sutherland MK, Geoghegan JC, Yu C, Turcott E, Skonier JE, et al. (2004) Sclerostin promotes the apoptosis of human osteoblastic cells: a novel regulation of bone formation. Bone 35: 828–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mirza FS, Padhi ID, Raisz LG, Lorenzo JA (2010) Serum sclerostin levels negatively correlate with parathyroid hormone levels and free estrogen index in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 1991–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li X, Ominsky MS, Warmington KS, Niu QT, Asuncion FJ, et al. (2011) Increased bone formation and bone mass induced by sclerostin antibody is not affected by pretreatment or cotreatment with alendronate in osteopenic, ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology 152: 3312–3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Teitelbaum SL (2007) Osteoclasts: what do they do and how do they do it? Am J Pathol 170: 427–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rodriguez JP, Garat S, Gajardo H, Pino AM, Seitz G (1999) Abnormal osteogenesis in osteoporotic patients is reflected by altered mesenchymal stem cells dynamics. J Cell Biochem 75: 414–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dalle Carbonare L, Valenti MT, Zanatta M, Donatelli L, Lo Cascio V (2009) Circulating mesenchymal stem cells with abnormal osteogenic differentiation in patients with osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheum 60: 3356–3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yang Q, McHugh KP, Patntirapong S, Gu X, Wunderlich L, et al. (2008) VEGF enhancement of osteoclast survival and bone resorption involves VEGF receptor-2 signaling and beta3-integrin. Matrix Biol 27: 589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fox SW, Lovibond AC (2005) Current insights into the role of transforming growth factor-beta in bone resorption. Mol Cell Endocrinol 243: 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hopwood B, Tsykin A, Findlay DM, Fazzalari NL (2009) Gene expression profile of the bone microenvironment in human fragility fracture bone. Bone 44: 87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sohr S, Engeland K (2008) RHAMM is differentially expressed in the cell cycle and downregulated by the tumor suppressor p53. Cell Cycle 7: 3448–3460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bringold F, Serrano M (2000) Tumor suppressors and oncogenes in cellular senescence. Exp Gerontol 35: 317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Trost Z, Trebse R, Prezelj J, Komadina R, Logar DB, et al. (2010) A microarray based identification of osteoporosis-related genes in primary culture of human osteoblasts. Bone 46: 72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Giner M, Rios MA, Montoya MA, Vazquez MA, Naji L, et al. (2009) RANKL/OPG in primary cultures of osteoblasts from post-menopausal women. Differences between osteoporotic hip fractures and osteoarthritis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 113: 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Limbert C, Ebert R, Schilling T, Path G, Benisch P, et al. (2010) Functional signature of human islet-derived precursor cells compared to bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 19: 679–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G (2001) Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 5116–5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rainer J, Sanchez-Cabo F, Stocker G, Sturn A, Trajanoski Z (2006) CARMAweb: comprehensive R- and bioconductor-based web service for microarray data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 34: W498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Boukhechba F, Balaguer T, Michiels JF, Ackermann K, Quincey D, et al. (2009) Human primary osteocyte differentiation in a 3D culture system. J Bone Miner Res 24: 1927–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, et al. (1995) A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92: 9363–9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cheung CL, Sham PC, Xiao SM, Bow CH, Kung AW (2011) Meta-analysis of gene-based genome-wide association studies of bone mineral density in Chinese and European subjects. Osteoporos Int [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Farber CR, Bennett BJ, Orozco L, Zou W, Lira A, et al. (2011) Mouse genome-wide association and systems genetics identify Asxl2 as a regulator of bone mineral density and osteoclastogenesis. PLoS Genet 7: e1002038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Saint-Pierre A, Kaufman JM, Ostertag A, Cohen-Solal M, Boland A, et al. (2011) Bivariate association analysis in selected samples: application to a GWAS of two bone mineral density phenotypes in males with high or low BMD. Eur J Hum Genet 19: 710–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Li GH, Kung AW, Huang QY (2010) Common variants in FLNB/CRTAP, not ARHGEF3 at 3p, are associated with osteoporosis in southern Chinese women. Osteoporos Int 21: 1009–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Heemstra KA, Hoftijzer H, van der Deure WM, Peeters RP, Hamdy NA, et al. (2010) The type 2 deiodinase Thr92Ala polymorphism is associated with increased bone turnover and decreased femoral neck bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res 25: 1385–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Paternoster L, Lorentzon M, Vandenput L, Karlsson MK, Ljunggren O, et al. (2010) Genome-wide association meta-analysis of cortical bone mineral density unravels allelic heterogeneity at the RANKL locus and potential pleiotropic effects on bone. PLoS Genet 6: e1001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mlakar SJ, Osredkar J, Prezelj J, Marc J (2011) Opposite effects of GSTM1 - and GSTT1 - gene deletion variants on bone mineral density. Dis Markers 31: 279–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hwang JY, Lee SH, Kim GS, Koh JM, Go MJ, et al. (2009) HSD11B1 polymorphisms predicted bone mineral density and fracture risk in postmenopausal women without a clinically apparent hypercortisolemia. Bone 45: 1098–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ralston SH, Uitterlinden AG (2010) Genetics of osteoporosis. Endocr Rev 31: 629–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Guo Y, Yang TL, Liu YZ, Shen H, Lei SF, et al. (2011) Mitochondria-wide association study of common variants in osteoporosis. Ann Hum Genet 75: 569–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhang YP, Deng FY, Chen Y, Pei YF, Fang Y, et al. (2010) Replication study of candidate genes/loci associated with osteoporosis based on genome-wide screening. Osteoporos Int 21: 785–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Karasik D, Hsu YH, Zhou Y, Cupples LA, Kiel DP, et al. (2010) Genome-wide pleiotropy of osteoporosis-related phenotypes: the Framingham Study. J Bone Miner Res 25: 1555–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cheung CL, Xiao SM, Kung AW (2010) Genetic epidemiology of age-related osteoporosis and its clinical applications. Nat Rev Rheumatol 6: 507–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yerges LM, Klei L, Cauley JA, Roeder K, Kammerer CM, et al. (2010) Candidate gene analysis of femoral neck trabecular and cortical volumetric bone mineral density in older men. J Bone Miner Res 25: 330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mitchell BD, Yerges-Armstrong LM (2011) The genetics of bone loss: challenges and prospects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96: 1258–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lee DY, Kim H, Ku SY, Kim SH, Choi YM, et al. (2010) Association between polymorphisms in Wnt signaling pathway genes and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Korean women. Menopause 17: 1064–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Pountos I, Georgouli T, Henshaw K, Bird H, Jones E, et al. (2010) The effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2, bone morphogenetic protein-7, parathyroid hormone, and platelet-derived growth factor on the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from osteoporotic bone. J Orthop Trauma 24: 552–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Komori T (2010) Regulation of bone development and extracellular matrix protein genes by RUNX2. Cell Tissue Res 339: 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Perrien DS, Nicks KM, Liu L, Akel NS, Bacon AW, et al. (2011) Inhibin A enhances bone formation during distraction osteogenesis. J Orthop Res [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Palermo C, Manduca P, Gazzerro E, Foppiani L, Segat D, et al. (2004) Potentiating role of IGFBP-2 on IGF-II-stimulated alkaline phosphatase activity in differentiating osteoblasts. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 286: E648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Street J, Lenehan B (2009) Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates osteoblast survival - evidence for an autocrine feedback mechanism. J Orthop Surg Res 4: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Park SJ, Gadi J, Cho KW, Kim KJ, Kim SH, et al. (2011) The forkhead transcription factor Foxc2 promotes osteoblastogenesis via up-regulation of integrin beta1 expression. Bone 49: 428–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Orimo H (2010) The mechanism of mineralization and the role of alkaline phosphatase in health and disease. J Nippon Med Sch 77: 4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Dingwall M, Marchildon F, Gunanayagam A, Louis CS, Wiper-Bergeron N (2011) Retinoic acid-induced Smad3 expression is required for the induction of osteoblastogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells. Differentiation 82: 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhao C, Irie N, Takada Y, Shimoda K, Miyamoto T, et al. (2006) Bidirectional ephrinB2-EphB4 signaling controls bone homeostasis. Cell Metab 4: 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Schuster I (2011) Cytochromes P450 are essential players in the vitamin D signaling system. Biochim Biophys Acta 1814: 186–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rice R, Rice DP, Thesleff I (2005) Foxc1 integrates Fgf and Bmp signalling independently of twist or noggin during calvarial bone development. Dev Dyn 233: 847–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Shin HI, Divieti P, Sims NA, Kobayashi T, Miao D, et al. (2004) Gp130-mediated signaling is necessary for normal osteoblastic function in vivo and in vitro. Endocrinology 145: 1376–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Miraoui H, Severe N, Vaudin P, Pages JC, Marie PJ (2010) Molecular silencing of Twist1 enhances osteogenic differentiation of murine mesenchymal stem cells: implication of FGFR2 signaling. J Cell Biochem 110: 1147–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Fukuda T, Chen L, Endo T, Tang L, Lu D, et al. (2008) Antisera induced by infusions of autologous Ad-CD154-leukemia B cells identify ROR1 as an oncofetal antigen and receptor for Wnt5a. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 3047–3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zhou S (2011) TGF-beta regulates beta-catenin signaling and osteoblast differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem 112: 1651–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gaddy-Kurten D, Coker JK, Abe E, Jilka RL, Manolagas SC (2002) Inhibin suppresses and activin stimulates osteoblastogenesis and osteoclastogenesis in murine bone marrow cultures. Endocrinology 143: 74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Abe Y, Abe T, Aida Y, Hara Y, Maeda K (2004) Follistatin restricts bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2 action on the differentiation of osteoblasts in fetal rat mandibular cells. J Bone Miner Res 19: 1302–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sidis Y, Mukherjee A, Keutmann H, Delbaere A, Sadatsuki M, et al. (2006) Biological activity of follistatin isoforms and follistatin-like-3 is dependent on differential cell surface binding and specificity for activin, myostatin, and bone morphogenetic proteins. Endocrinology 147: 3586–3597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Jacob AL, Smith C, Partanen J, Ornitz DM (2006) Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 signaling in the osteo-chondrogenic cell lineage regulates sequential steps of osteoblast maturation. Dev Biol 296: 315–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zhu J, Shimizu E, Zhang X, Partridge NC, Qin L (2011) EGFR signaling suppresses osteoblast differentiation and inhibits expression of master osteoblastic transcription factors Runx2 and Osterix. J Cell Biochem 112: 1749–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ideno H, Takanabe R, Shimada A, Imaizumi K, Araki R, et al. (2009) Protein related to DAN and cerberus (PRDC) inhibits osteoblastic differentiation and its suppression promotes osteogenesis in vitro. Exp Cell Res 315: 474–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Nakanishi R, Akiyama H, Kimura H, Otsuki B, Shimizu M, et al. (2008) Osteoblast-targeted expression of Sfrp4 in mice results in low bone mass. J Bone Miner Res 23: 271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kaji H, Sugimoto T, Kanatani M, Fukase M, Kumegawa M, et al. (1996) Prostaglandin E2 stimulates osteoclast-like cell formation and bone-resorbing activity via osteoblasts: role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Bone Miner Res 11: 62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Avnet S, Salerno M, Quacquaruccio G, Granchi D, Giunti A, et al. (2011) IGF2 derived from SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells induces the osteoclastogenesis of human monocytic precursors. Exp Cell Res 317: 2147–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Perez-Sayans M, Somoza-Martin JM, Barros-Angueira F, Rey JM, Garcia-Garcia A (2010) RANK/RANKL/OPG role in distraction osteogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 109: 679–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Shapses SA, Cifuentes M, Spevak L, Chowdhury H, Brittingham J, et al. (2003) Osteopontin facilitates bone resorption, decreasing bone mineral crystallinity and content during calcium deficiency. Calcif Tissue Int 73: 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Roato I, Brunetti G, Gorassini E, Grano M, Colucci S, et al. (2006) IL-7 up-regulates TNF-alpha-dependent osteoclastogenesis in patients affected by solid tumor. PLoS One 1: e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Carron JA, Wagstaff SC, Gallagher JA, Bowler WB (2000) A CD36-binding peptide from thrombospondin-1 can stimulate resorption by osteoclasts in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 270: 1124–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Brunetti G, Oranger A, Mori G, Sardone F, Pignataro P, et al. (2011) TRAIL effect on osteoclast formation in physiological and pathological conditions. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 3: 1154–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Shaarawy M, Zaki S, Sheiba M, El-Minawi AM (2003) Circulating levels of osteoclast activating cytokines, interleukin-11 and transforming growth factor-beta2, as valuable biomarkers for the assessment of bone turnover in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Clin Lab 49: 625–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Geoffroy V, Kneissel M, Fournier B, Boyde A, Matthias P (2002) High bone resorption in adult aging transgenic mice overexpressing cbfa1/runx2 in cells of the osteoblastic lineage. Mol Cell Biol 22: 6222–6233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Bartholin L, Destaing O, Forissier S, Martel S, Maguer-Satta V, et al. (2005) FLRG, a new ADAM12-associated protein, modulates osteoclast differentiation. Biol Cell 97: 577–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Sun LQ, Arceci RJ (2005) Altered epigenetic patterning leading to replicative senescence and reduced longevity. A role of a novel SNF2 factor, PASG. Cell Cycle 4: 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Wagner W, Bork S, Lepperdinger G, Joussen S, Ma N, et al. (2010) How to track cellular aging of mesenchymal stromal cells? Aging (Albany NY) 2: 224–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Longo VD (2004) Ras: the other pro-aging pathway. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ 2004: pe36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Musgrove EA (2006) Cyclins: roles in mitogenic signaling and oncogenic transformation. Growth Factors 24: 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Kong M, Barnes EA, Ollendorff V, Donoghue DJ (2000) Cyclin F regulates the nuclear localization of cyclin B1 through a cyclin-cyclin interaction. EMBO J 19: 1378–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Sandhu C, Donovan J, Bhattacharya N, Stampfer M, Worland P, et al. (2000) Reduction of Cdc25A contributes to cyclin E1-Cdk2 inhibition at senescence in human mammary epithelial cells. Oncogene 19: 5314–5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Dalvai M, Mondesert O, Bourdon JC, Ducommun B, Dozier C (2011) Cdc25B is negatively regulated by p53 through Sp1 and NF-Y transcription factors. Oncogene 30: 2282–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Bonnet J, Coopman P, Morris MC (2008) Characterization of centrosomal localization and dynamics of Cdc25C phosphatase in mitosis. Cell Cycle 7: 1991–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Endoh M, Kobayashi Y, Yamakami Y, Yonekura R, Fujii M, et al. (2009) Coordinate expression of the human pregnancy-specific glycoprotein gene family during induced and replicative senescence. Biogerontology 10: 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Hubscher U, Maga G, Spadari S (2002) Eukaryotic DNA polymerases. Annu Rev Biochem 71: 133–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Mimitou EP, Symington LS (2011) DNA end resection–unraveling the tail. DNA Repair (Amst) 10: 344–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Boehler C, Gauthier LR, Mortusewicz O, Biard DS, Saliou JM, et al. (2011) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 3 (PARP3), a newcomer in cellular response to DNA damage and mitotic progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 2783–2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Modesti M, Budzowska M, Baldeyron C, Demmers JA, Ghirlando R, et al. (2007) RAD51AP1 is a structure-specific DNA binding protein that stimulates joint molecule formation during RAD51-mediated homologous recombination. Mol Cell 28: 468–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Nitiss JL (2009) DNA topoisomerase II and its growing repertoire of biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 327–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ranuncolo SM, Polo JM, Melnick A (2008) BCL6 represses CHEK1 and suppresses DNA damage pathways in normal and malignant B-cells. Blood Cells Mol Dis 41: 95–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Thomas JO (2001) HMG1 and 2: architectural DNA-binding proteins. Biochem Soc Trans 29: 395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Gene products with significant expression changes in hMSC-OP compared to hMSC-old. FC = fold change (at least 2fold); FDR = false discovery rate (<10%).

(DOC)

Gene products differentially expressed in hMSC-OP, hMSC-old and hMSC-senescent when compared to hMSC-C. arrows pointing downward = significant, reduced expression in comparison to hMSC-C; arrows pointing upward = significant, enhanced expression in comparison to hMSC-C; FC = fold change (at least 2fold); FDR = false discovery rate (<10%); — = no expression in both hMSC groups compared.

(DOC)