Abstract

We demonstrate that phosphorylation of the NS1 protein of a human influenza A virus occurs not only at the threonine (T) at position 215 but also at serines (Ss), specifically at positions 42 and 48. By generating recombinant influenza A/Udorn/72 (Ud) viruses that encode mutant NS1 proteins, we determined the roles of these phosphorylations in virus replication. At position 215 only a T-to-A substitution attenuated replication, whereas other substitutions (T to E to mimic constitutive phosphorylation, T to N, and T to P, the amino acid in avian influenza A virus NS1 proteins) had no effect. We conclude that attenuation resulting from the T-to-A substitution at position 215 is attributable to a deleterious structural change in the NS1 protein that is not caused by other amino acid substitutions and that phosphorylation of T215 does not affect virus replication. At position 48 neither an S-to-A substitution nor an S-to-D substitution that mimics constitutive phosphorylation affected virus replication. In contrast, at position 42, an S-to-D, but not an S-to-A, substitution caused attenuation. The S-to-D substitution eliminates detectable double-stranded RNA binding by the NS1 protein, accounting for attenuation of virus replication. We show that protein kinase C α (PKCα) catalyzes S42 phosphorylation. Consequently, the only phosphorylation of the NS1 protein of this human influenza A virus that regulates its replication is S42 phosphorylation catalyzed by PKCα. In contrast, phosphorylation of Ts or Ss in the NS1 protein of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus was not detected, indicating that NS1 phosphorylation probably does not play any role in the replication of this virus.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza A viruses cause a highly contagious respiratory disease in humans, resulting in annual epidemics and periodic worldwide pandemics. The smallest of the eight negative-sense viral gene segments encodes the NS1 protein, a nonstructural protein that plays multiple crucial roles in virus replication (5). Most NS1 proteins are 230 to 237 amino acids long, although shorter forms have also been found. The NS1 protein comprises two functional domains: the N-terminal (amino acids 1 to 73) RNA-binding domain (RBD) and the C-terminal (amino acids 74 to 230/237) effector domain (ED), which binds several cellular proteins.

The NS1 protein undergoes three posttranslational modifications: phosphorylation by cellular kinases (4, 12, 13), ISG15 modification by the interferon (IFN)-induced ISG15 conjugation system (17, 21), and modification by SUMO (11, 20). It has been reported that these modifications affect the NS1 protein and the phenotype of the virus (4, 17, 21). Phosphorylation of threonines (Ts) of the NS1 protein was observed many years ago (12, 13). It was reported that T at position 215 (T215) of the NS1 protein of the human H3N2 influenza A/Udorn/72 virus (Ud) is phosphorylated and that this phosphorylation is important for virus replication (4). The basis for the latter conclusion was that a recombinant Ud virrus encoding an NS1 protein with a T-to-A substitution at position 215 in the ED was attenuated for replication in tissue culture cells. This phosphorylation is of interest because T215 is a signature for human influenza A virus strains. All influenza A viruses circulating in humans from 1920 to 2008 encode NS1 proteins with T at position 215, whereas the NS1 proteins of avian influenza A viruses, including H5N1 viruses, contain proline (P) at this position. Two viruses that have circulated in humans, the 1918 virus and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus, encode NS1 proteins with the avian P215 signature.

Here we confirm that T215 of the Ud NS1 protein is phosphorylated during virus infection, but in contrast to the conclusion of a previous study (4), we show that phosphorylation of T215 does not affect replication of the Ud virus. We also demonstrate that NS1 phosphorylation is not restricted to Ts by identifying two phosphorylated serines (Ss), specifically the Ss at positions 42 and 48 (S42 and S48) in the RBD. By generating recombinant influenza A/Udorn/72 viruses that encode mutant NS1 proteins, we show that the only phosphorylation of the NS1 protein that regulates Ud virus replication is phosphorylation of S42, which is catalyzed by protein kinase C α (PKCα). In contrast, the NS1 protein of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus is not phosphorylated at S42 or at any other T or S.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

A549, MDCK, and 293T cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). Calu3 cells were grown in advanced MEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Wild-type (wt) and mutant influenza A/Udorn/72 and A/California/04/09 viruses were generated by plasmid-based reverse genetics, as described previously (16, 18). Viruses expressing N-terminal 3×Flag-tagged NS1 and NS2 proteins were generated as described previously (21). Amino acid substitutions were introduced into the NS1 protein using standard oligonucleotide mutagenesis methods. Several of the amino acid substitutions at position 215 of the NS1 protein lead to changes in the overlapping NS2 protein sequence. The T-to-A substitution at 215 does not change the NS2 protein sequence; the T-to-E substitution results in an L-to-S substitution at position 58 in the NS2 protein; the T-to-P substitution leads to an L-to-S substitution at position 57 in NS2, the same substitution in the influenza A/Vietnam/1203/04 NS2 protein; and the T-to-N substitution causes an L-to-I substitution at position 58 in NS2. All eight genomic RNA segments of recombinant viruses were sequenced. Virus stocks were grown in 10-day-old fertilized eggs, and virus titers were determined by plaque assays in MDCK cells. For multiple-cycle growth, MDCK or Calu3 cells were infected with virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001 PFU/cell. After 1 h of adsorption at 37°C, the cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), replenished with medium, either DMEM (MDCK cells) or advanced MEM (Calu3 cells), containing 2.5 μg/ml N-acetylated trypsin (NAT), and incubated at 37°C. For single-cycle growth, MDCK cells were infected with virus at an MOI of 5 PFU/cell.

Identification of phosphorylation sites in the NS1 protein.

A549 cells were infected for 8 h with 5 PFU/cell of virus expressing 3×Flag-tagged NS1 and NS2 proteins. Cells were extracted with a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 1% NP-40, supplemented with the Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Pierce). After clarification by centrifugation for 15 min at 10,000 × g, the extracts were affinity selected by binding to anti-Flag M2–agarose beads, followed by elution with 3×Flag peptide. The eluate was subjected to electrophoresis on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The NS1 protein band was identified by colloidal blue staining and was analyzed by mass spectrometry (Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility at Harvard Medical School) to identify phosphorylated amino acids. The procedure used by this facility was as follows. The gel slice containing the NS1 protein was subjected to a modified in-gel trypsin digestion procedure (15), and the resulting peptides were eluted from the gel. The peptides were then separated on a nanoscale high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) capillary column. Each peptide was subjected to electrospray ionization and entered into an LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA). Eluting peptides were detected, isolated, and fragmented to produce a tandem mass spectrum of specific fragment ions for each peptide. Peptide sequences (and hence protein identity) were determined by matching protein or translated nucleotide databases with the acquired fragmentation pattern by the software program Sequest (2). The modification of 80 mass units to serine, threonine, and tyrosine was included in the database searches to determine phosphopeptides. Each phosphopeptide that was determined by the Sequest program was also manually inspected to ensure confidence. Based on the amount of the NS1 protein that was analyzed, it was estimated based on previous experience that phosphorylation of 0.1 to 1.0% of an amino acid would be detected. Sequence coverage of the NS1 protein was approximately 85% to 90%. For unknown reasons, the N-terminal 18 amino acids of NS1 were absent from each analysis.

dsRNA binding assays.

Coding sequences for NS1 RBDs, wild type or containing amino acid substitutions, were inserted into pGEX-6P1 vectors, and the resulting glutathione S-transferase (GST)–RBDs were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 and purified by selection on glutathione-Sepharose. To prepare a labeled 140-base-pair double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) substrate, the Ud NS2 coding sequence was inserted into a pGEM1 vector, which was separately transcribed by the SP6 and T7 RNA polymerases in the presence of ATP, CTP, GTP, and [32P]UTP. The two RNAs were annealed to each other to form labeled dsRNA, which was incubated with various concentrations of the GST-NS1 RBD on ice for 30 min in 50 μl of binding buffer (43 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 8% glycerol, 0.5 μg/μl tRNA, 0.5 U/μl RNase inhibitor). The binding mixtures were applied to the wells of a 96-well dot blot apparatus and allowed to pass through a nitrocellulose membrane that binds labeled RNA bound to the RBD, followed by a nylon membrane that binds free labeled RNA. The two membranes were exposed to storage phosphor screens, which were quantified using a Typhoon Trio imager system. The fraction of the RNA bound to the RBD was calculated by dividing the amount of RNA on the nitrocellulose filter by the amount of the total RNA on the two filters.

Kinase assay.

The GST-NS1 RBD (10 μg) was incubated at 30°C for 30 min with 50 ng of activated PKCα kinase (Invitrogen) in a buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM ATP. The mixtures were subjected to electrophoresis on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and were first analyzed using Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein gel stain (Invitrogen), followed by Sypro Ruby total protein stain (Invitrogen). After each staining, the gels were analyzed using the Typhoon Trio imager system.

RESULTS

Identification of the sites of phosphorylation of the NS1 protein of A/Udorn/72 (Ud) virus.

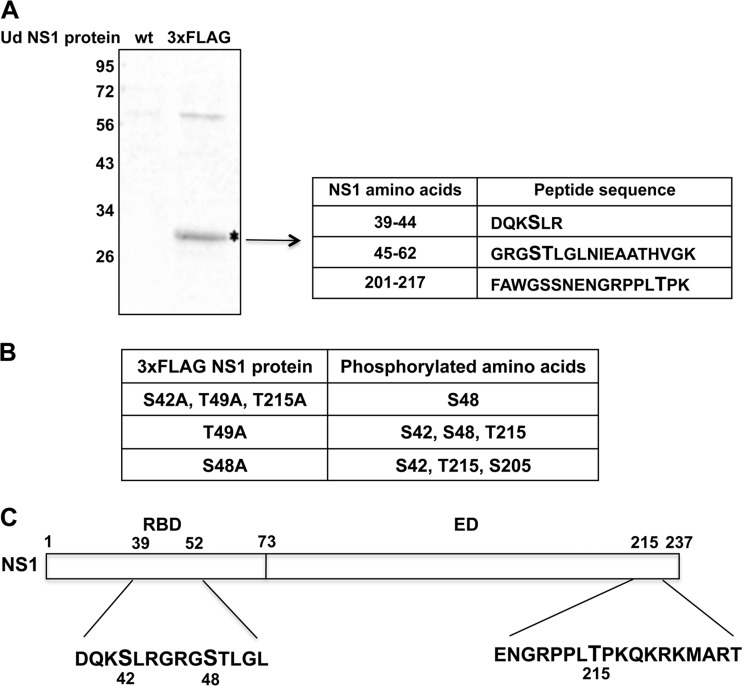

To identify the sites of phosphorylation of the Ud NS1 protein, we purified the NS1 protein from virus-infected cells and used mass spectrometry to determine which amino acids were phosphorylated. To facilitate this purification, we used a Ud virus that encodes N-terminal 3×Flag-tagged NS1 and NS2 proteins (21). At 8 h after high-multiplicity infection of human A549 cells, the 3×Flag-tagged NS1 protein was purified from cell extracts by selection on anti-Flag M2–agarose followed by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1A). Mass spectrometry of the purified NS1 protein identified phosphorylation of S42 and T215, as well as a phosphorylated amino acid in the tryptic peptide containing amino acids 45 to 62 (peptide 45-62) (see the supplemental material). This analysis did not establish whether phosphorylation in the latter tryptic peptide is at S48 or T49.

Fig 1.

Three amino acids of the NS1 protein of Ud influenza A virus are phosphorylated during infection. (A) A549 cells were infected with the Ud virus expressing NS1 and NS2 proteins with an N-terminal 3×Flag tag. Infected-cell proteins were affinity purified using anti-Flag M2–agarose and were then resolved by gel electrophoresis followed by staining with colloidal blue (left). Molecular masses in kDa are shown on the left of the gel. The 3×Flag-tagged NS2 protein migrated off the gel. The 3×Flag-tagged NS1 protein (*) was cut out and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The three peptides that contain a phosphorylated T or S (denoted by larger lettering) are shown (right). Peptide 45-62 contains either a phosphorylated S (position 48) or a phosphorylated T (position 49). (B) The same analysis was carried out with the Ud viruses containing the indicated amino acid substitutions. (C) Positions of the phosphorylated S and T amino acids in the Ud NS1 protein.

To determine whether S48 or T49 is phosphorylated, we first generated a Ud virus encoding a 3×Flag-tagged NS1 protein with three mutations (S42A, T49A, and T215A). Mass spectrometry of this mutant NS1 protein showed that tryptic peptide 45-62 contained a phosphorylated amino acid at position 48/49, which could only be phosphorylated S48 (Fig. 1B; see the supplemental material). As confirmation, we generated two other Ud viruses encoding 3×FLAG-tagged NS1 proteins with either a T49A or an S48A mutation. Mass spectrometry of the T49A mutant NS1 showed that S48 was phosphorylated, along with the S42 and T215 phosphorylations. Conversely, mass spectrometry of the S48A mutant NS1 did not detect T49 phosphorylation but only S42 and T215 phosphorylation, along with a new phosphorylation at S205 that was not present in the wt NS1 protein. Consequently, these results show that S48, and not T49, is phosphorylated, indicating that there are three sites of phosphorylation of the Ud NS1 protein: T215 in the ED and S42 and S48 in the RBD (Fig. 1C).

T215 phosphorylation is not required for replication of Ud virus in tissue culture.

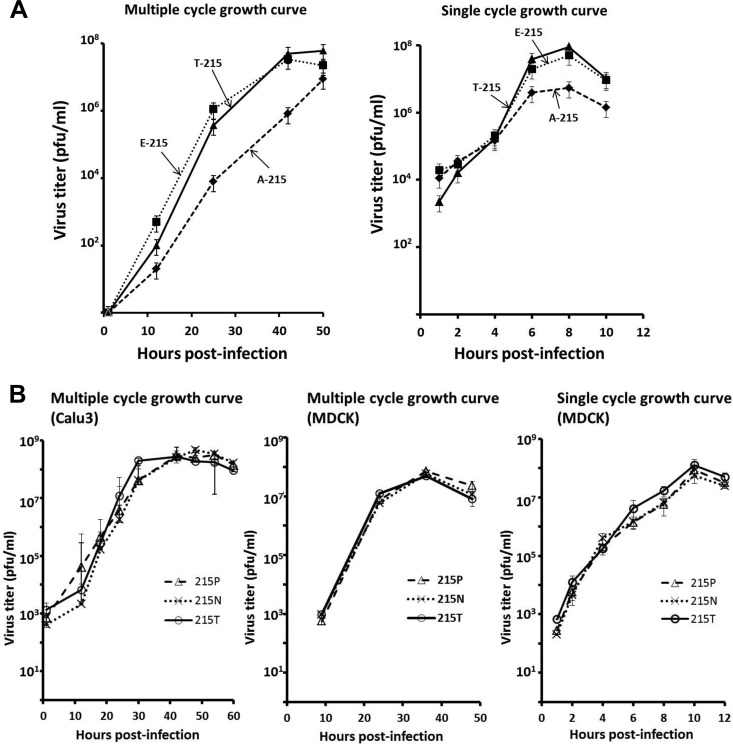

We reevaluated the effect of T215 phosphorylation on Ud virus replication in tissue culture by generating recombinant Ud viruses encoding NS1 proteins with several different substitutions at position 215. First, we generated recombinant Ud viruses encoding an NS1 protein with either a T-to-A substitution at 215 to eliminate phosphorylation or a T-to-E substitution at 215 to mimic constitutive phosphorylation. The virus expressing the A215 NS1 protein (A215 virus) is attenuated. During multiple-cycle growth in MDCK cells the A125 virus replicated slower than the wt T215 virus, yielding approximately 60-fold less virus at both 24 and 44 h postinfection (Fig. 2A). The A215 virus was also attenuated during single-cycle growth in MDCK cells, yielding approximately 10-fold less virus than the T215 wt virus. In contrast, replication of the E215 virus was not attenuated during either multiple- or single-cycle growth (Fig. 2A), indicating that constitutive phosphorylation of T215 of the NS1 protein does not affect virus replication in tissue culture.

Fig 2.

Phosphorylation of T215 is not required for replication of Ud virus in tissue culture. (A) The Ud virus expressing an A215 NS1 protein (A215 virus) replicates slower than the wild-type (T215) virus during both multiple- and single-cycle growth in MDCK cells, whereas the E215 virus is not attenuated in replication. Growth curves were carried out in triplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviations from the mean values of the three independent assays. (B) Ud viruses expressing an NS1 protein with P215 or N215 are not attenuated in replication in tissue culture. Shown are multiple-cycle growth of T215, P215, and N215 Ud viruses in Calu3 and MDCK cells and single-cycle growth of these viruses in MDCK cells. Growth curves were carried out in triplicate. Error bars are shown.

To further assess the role of T215 phosphorylation, we generated Ud viruses with other amino acid substitutions at position 215 in the NS1 protein. Specifically, we made a T-to-P substitution to mimic the avian P215 signature and a T-to-N substitution. N is approximately the same size as E (the phosphorylation mimic) but lacks its negative charge. We measured the multiple-cycle growth of these two mutant viruses, as well as the T215 wild-type virus, in both MDCK cells and human Calu3 cells (Fig. 2B). Neither the P215 nor the N215 virus was attenuated for virus replication in either cell line. In addition, neither of these two viruses was attenuated in single-cycle growth in MDCK cells. These results, coupled with the results with the E215 virus, establish that phosphorylation of T215 does not affect replication of Ud virus in tissue culture cells and indicate that the attenuation of the A215 virus is likely due to a deleterious effect on the structure of the NS1 protein.

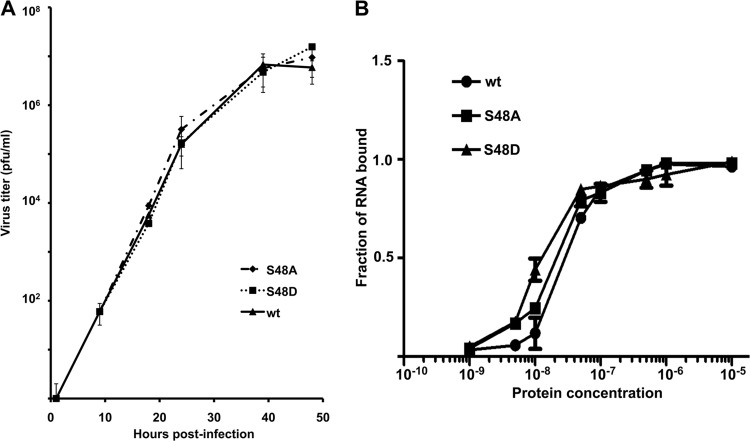

Phosphorylation of S48 does not affect Ud virus replication.

To determine the role of S48 phosphorylation in virus replication, we generated Ud viruses expressing NS1 proteins with either an S-to-A or an S-to-D (mimicking constitutive phosphorylation) substitution at position 48, denoted the S48A and S48D Ud viruses, respectively. Based on their multiple-cycle growth in MDCK cells (Fig. 3A), the S48A and S48D Ud viruses were not attenuated in virus replication. This lack of attenuation is consistent with the results of assays of the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) binding activities of purified wt, S48A, and S48D Ud RBDs (Fig. 3B). Increasing amounts of these three RBDs were incubated with a labeled 140-base-pair dsRNA, and dsRNA binding was measured in a filter-binding assay. The three RBDs had the same affinity for dsRNA, demonstrating that changing S48 to either A or D does not reduce the affinity of the RBD for dsRNA.

Fig 3.

Phosphorylation of S48 is not required for replication of Ud virus in tissue culture. (A) Ud viruses expressing an NS1 protein with A or D at position 48 are not attenuated during multiple-cycle growth in MDCK cells. Growth curves were carried out in triplicate. (B) RBDs with S48 (wt) or S48 replaced with either A or D bind to a 140-bp dsRNA with similar affinities. Binding assays were carried out in triplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the three assays.

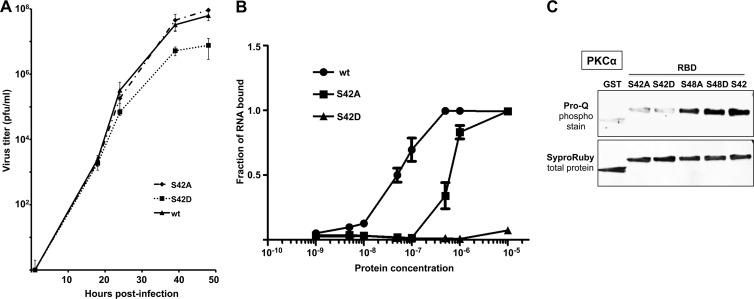

Phosphorylation of S42, which is catalyzed by PKCα, attenuates Ud virus replication.

To determine the role of S42 phosphorylation in virus replication, we generated Ud viruses expressing NS1 proteins with either an S-to-A or an S-to-D substitution at position 42, denoted the S42A and S42D Ud viruses, respectively. Based on their multiple-cycle growth in MDCK cells (Fig. 4A), the S42A virus was not attenuated in virus replication, whereas the S42D virus was attenuated, yielding approximately 10-fold-less virus. Assays for dsRNA binding showed that the affinity of the S42A RBD for dsRNA was approximately 10-fold lower than that of the wt RBD (Fig. 4B), although there was no detectable effect on virus infection (see Discussion). The S42D RBD had essentially no dsRNA-binding activity (Fig. 4B), consistent with the attenuation of virus replication.

Fig 4.

Phosphorylation of S42 attenuates Ud virus replication. (A) The Ud virus expressing an NS1 protein with D at position 42 is attenuated during multiple-cycle growth in MDCK cells, whereas the Ud virus expressing an NS1 protein with A at position 42 is not attenuated. Growth curves were carried out in triplicate. (B) Relative binding affinities of the RBDs with S42 (wt), with S42 replaced with A, or with S42 replaced by D. (C) S42 in the Ud NS1 is phosphorylated by activated PKCα. GST or RBDs with the indicated amino acid at position 42 or 48 were incubated with PKCα, and after gel electrophoresis the gels were stained with Pro-Q to detect phosphorylation, followed by staining with Sypro Ruby to detect total protein.

Several computer programs (Scansite 2.0, NetPhosK, and Phospho Motif Finder) predicted that S42 would be phosphorylated by PKCα. To test this prediction, we purified bacterially expressed NS1 RBDs containing either the wt sequence (S42) or S-to-A or S-to-D substitutions at position 42 or 48 and incubated these RBDs with activated PKCα. After gel electrophoresis, the RBDs were stained with Pro-Q to detect phosphorylation or with Sypro Ruby to measure the amount of protein. The S-to-A and S-to-D substitutions at 42 eliminated phosphorylation of the RBD, demonstrating that PKCα phosphorylates S42. Because the S-to-A and S-to-D substitutions at position 48 did not affect phosphorylation of the RBD, PKCα is not responsible for phosphorylation of the S at this position.

The NS1 protein of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus is not phosphorylated at S42.

The NS1 protein of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus has P, rather than T, at position 215 and N, rather than S, at position 48, so that phosphorylations at these two positions are not possible. To determine whether this NS1 protein is phosphorylated at S42, we generated a recombinant 2009 H1N1 virus encoding N-terminal 3×Flag-tagged NS1 and NS2 proteins. Mass spectrometry did not detect any phosphorylation of S42 of the NS1 protein (see the supplemental material).

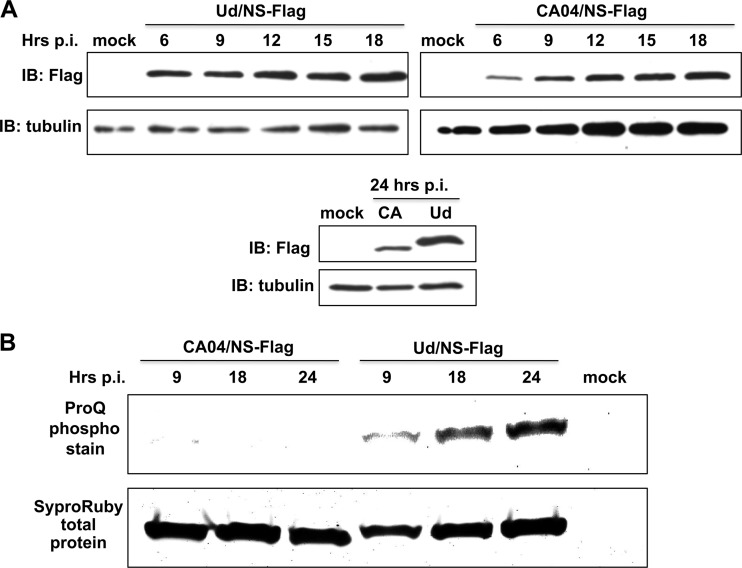

To verify this result, we used Pro-Q staining to determine whether phosphorylation of the 2009 H1N1 protein was detectable at any times after infection (Fig. 5). First, we compared the time course of NS1 protein production in 2009 H1N1-infected cells to the time course in Ud-infected cells (Fig. 5A). NS1 protein production started earlier in Ud-infected cells, which was most evident at 6 h postinfection. In addition, approximately 5 times more NS1 protein was produced at 24 h postinfection in Ud-infected cells than in the 2009 H1N1-infected cells. To compensate for this difference, we used large amounts of the 2009 H1N1 NS1 protein for Pro-Q staining (Fig. 5B). Pro-Q staining of the 2009 H1N1 NS1 protein isolated at 9, 18, or 24 h was not detected. In contrast, Pro-Q staining of the Ud NS1 protein was detected at these time points. Consequently, phosphorylation was not detected in the 2009 H1N1 NS1 protein.

Fig 5.

Phosphorylation of the CA09 NS1 protein is not detected by Pro-Q staining at any times after infection. (A) Time course of NS1 protein production in A549 cells infected with 5 PFU/cell of either Ud/NS-Flag (Ud virus expressing a NS1 with a N-terminal Flag tag) or CA09/NS-Flag virus. The amount of NS1 protein produced was determined by measuring immunoblots (IBs) probed with anti-Flag antibody. p.i., postinfection. (B) Pro-Q staining to detect phosphorylation of the NS1 proteins of Ud/NS-Flag and CA09/NS-Flag viruses at the indicated times of infection. Total NS1 protein was measured using Sypro Ruby staining.

DISCUSSION

We show that the NS1 protein of the 1972 H3N2 Ud influenza A virus is phosphorylated not only at T at position 215 but also at two Ss at positions 42 and 48 and that only the phosphorylation at S42 affects virus replication in mammalian cells in tissue culture. At position 215 only a T-to-A substitution led to attenuated replication, whereas the following substitutions had no effect: a T-to-E substitution to mimic constitutive phosphorylation, a T-to-N substitution, and a T-to-P substitution to mimic the avian signature at this position. We realize that each of the latter three substitutions also introduced a single amino acid change in the NS2 protein, which as shown here did not lead to attenuation of virus replication. Based on these results, it is likely that the attenuation resulting from the T-to-A substitution is caused by a deleterious structural change in the NS1 protein that is not caused by the other amino acid substitutions. Because the structure of the NS1 protein in the region of amino acid 215 has not yet been determined (3, 19), it is not known how the T-to-A substitution at 215 would disrupt critical structural elements. Consequently, we did not detect any role for T215 phosphorylation in Ud virus replication in mammalian cells in tissue culture. We also did not detect any effect on Ud virus replication when the avian signature amino acid P was substituted for T at 215. In fact, T215 phosphorylation is not required for human infection and transmissibility, because the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus that encodes P at 215 in its NS1 protein is readily transmitted between humans (10).

At position 48 neither an S-to-A nor an S-to-D substitution in the NS1 protein affected Ud virus infection. Because of its location in the RBD, S48 does not participate in dsRNA binding (1), so the A and D substitutions at this position would not be expected to affect dsRNA binding, an expectation that was verified by our filter binding assay (Fig. 3B). In fact, S at position 48 in the NS1 proteins of H3N2 viruses changed to N in the mid-1980s, and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus has N at this position. Consequently, phosphorylation at S48 not only does not play a role in influenza A virus replication in tissue culture but also is not required for efficient infection and transmission in humans.

In contrast, our results show that phosphorylation of S42 in the NS1 protein does affect Ud virus replication. S42 is highly conserved in the NS1 proteins of human influenza A viruses. We showed that changing S42 to D to mimic phosphorylation caused a 10-fold reduction in Ud virus replication during multiple-cycle growth. This attenuation is attributable to the loss of dsRNA-binding activity caused by the S-to-D substitution at position 42. S42 is directly involved in dsRNA binding by forming hydrogen bonds with 2′-OH groups of the dsRNA (1). Consequently, replacing S42 with the negatively charged D amino acid not only eliminates this hydrogen bonding but also repels the negatively charged dsRNA, explaining the loss of dsRNA-binding activity. Phosphorylation of S42 would have the same effect. Previous results have shown that the loss of NS1 dsRNA-binding activity leads to activation of the IFN-induced 2′-5′ oligo(A)synthetase (2′-5′ OAS), resulting in the activation of RNase L (8). Because it is not known when S42 phosphorylation occurs during infection and what fraction of the NS1 protein is phosphorylated, the timing and extent of activation of the 2′-5′ OAS/RNase L pathway by S42 phosphorylation during infection are also not known.

Because of the absence of detectable dsRNA-binding activity resulting from the S-to-D replacement at position 42, it was unexpected that the attenuation of virus replication was only 10-fold. In contrast, the loss of dsRNA-binding activity caused by the R-to-A change at position 38 in the NS1 protein of the Ud virus (R38A virus) resulted in 1,000-fold attenuation of virus replication during multiple-cycle growth (8). Activation of the 2′-5′ OAS/RNase L pathway accounted for part, but not all, of the attenuation of the R38A virus. The residual attenuation was not due to an increase in IFN production because no such increase was detected (8). The present results suggest an unexpected explanation for the residual attenuation of the R38A virus. The major difference between the R38A mutation and the S42D mutation carried out in the present study is that the former, but not the latter, mutation inactivates the nuclear localization signal (NLS) (NLS1, amino acids 35 to 41) associated with the RBD. Although the second NLS (NLS2) in the C terminus of the Ud NS1 protein (amino acids 219 to 232) (7) enabled the R38A Ud NS1 protein to enter the nucleus (8), it is conceivable that nuclear import of the NS1 protein mediated solely by NLS2 is not optimal. It was also unexpected that an S-to-A substitution at position 42, which reduces dsRNA-binding by 10-fold, did not lead to detectable attenuation during multiple-cycle growth. One explanation for the lack of attenuation is that even 10-fold-reduced dsRNA binding by the NS1 protein is sufficient to compete with 2′-5′ OAS for dsRNA, thereby maintaining the blockage of 2′-5′ OAS activation.

We have shown that activated PKCα phosphorylates S42 in the Ud NS1 protein. This kinase also phosphorylates two amino acids in PB1-F2 (9). PKCα, as well as other PKCs, is rapidly activated upon influenza virus infection (6, 14). Nonetheless, as shown here, phosphorylation of the 2009 H1N1 NS1 protein, including its S42 amino acid, was not detected, indicating that NS1 phosphorylation probably does not play any role in the replication of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This investigation was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI-11772 to R.M.K.

We thank Ross Tomaino and Steven Gygi of the Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility at Harvard Medical School for their expert help and advice.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 July 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cheng A, Wong SM, Yuan YA. 2009. Structural basis for dsRNA recognition by NS1 protein of influenza A virus. Cell Res. 19:187–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR. 1994. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 5:976–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hale BG, Barclay WS, Randall RE, Russell RJ. 2008. Structure of an avian influenza A virus NS1 protein effector domain. Virology 378:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hale BG, et al. 2009. CDK/ERK-mediated phosphorylation of the human influenza A virus NS1 protein at threonine-215. Virology 383:6–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hale BG, Randall RE, Ortin J, Jackson D. 2008. The multifunctional NS1 protein of influenza A viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 89:2359–2376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kunzelmann K, et al. 2000. Influenza virus inhibits amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels in respiratory epithelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:10282–10287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Melen K, et al. 2007. Nuclear and nucleolar targeting of influenza A virus NS1 protein: striking differences between different virus subtypes. J. Virol. 81:5995–6006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Min J-Y, Krug RM. 2006. The primary function of RNA binding by the influenza A virus NS1 protein in infected cells: inhibiting the 2′-5′ OAS/RNase L pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:7100–7105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitzner D, et al. 2009. Phosphorylation of the influenza A virus protein PB1-F2 by PKC is crucial for apoptosis promoting functions in monocytes. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1502–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Neumann G, Noda T, Kawaoka Y. 2009. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature 459:931–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pal S, Rosas JM, Rosas-Acosta G. 2010. Identification of the non-structural influenza A viral protein NS1A as a bona fide target of the small ubiquitin-like modifier by the use of dicistronic expression constructs. J. Virol. Methods 163:498–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Privalsky ML, Penhoet EE. 1978. Influenza virus proteins: identity, synthesis, and modification analyzed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75:3625–3629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Privalsky ML, Penhoet EE. 1981. The structure and synthesis of influenza virus phosphoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 256:5368–5376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rott O, Charreire J, Semichon M, Bismuth G, Cash E. 1995. B cell superstimulatory influenza virus (H2-subtype) induces B cell proliferation by a PKC-activating, Ca(2+)-independent mechanism. J. Immunol. 154:2092–2103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. 1996. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68:850–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takeda M, Pekosz A, Shuck K, Pinto LH, Lamb RA. 2002. Influenza a virus M2 ion channel activity is essential for efficient replication in tissue culture. J. Virol. 76:1391–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tang Y, et al. 2010. Herc5 attenuates influenza A virus by catalyzing ISGylation of viral NS1 protein. J. Immunol. 184:5777–5790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Twu KY, Noah DL, Rao P, Kuo R-L, Krug RM. 2006. The CPSF30 binding site on the NS1A protein of influenza A virus is a potential antiviral target. J. Virol. 80:3957–3965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xia S, Monzingo AF, Robertus JD. 2009. Structure of NS1A effector domain from the influenza A/Udorn/72 virus. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65:11–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xu K, et al. 2011. Modification of nonstructural protein 1 of influenza A virus by SUMO1. J. Virol. 85:1086–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao C, Hsiang TY, Kuo RL, Krug RM. 2010. ISG15 conjugation system targets the viral NS1 protein in influenza A virus-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:2253–2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.