Abstract

It has been hypothesized that neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) should have broad specificity to be effective in protection against diverse HIV-1 variants. The mother-to-child transmission model of HIV-1 provides the opportunity to examine whether the breadth of maternal NAbs is associated with protection of infants from infection. Samples were obtained at delivery from 57 transmitting mothers (T) matched with 57 nontransmitting mothers (NT) enrolled in the multicenter French perinatal cohort (ANRS EPF CO1) between 1990 and 1996. Sixty-eight (59.6%) and 46 (40.4%) women were infected by B and non-B viruses, respectively. Neutralization assays were carried out with TZM-bl cells, using a panel of 10 primary isolates of 6 clades (A, B, C, F, CRF01_AE, and CRF02_AG), selected for their moderate or low sensitivity to neutralization. Neutralization breadths were not statistically different between T and NT mothers. However, a few statistically significant differences were observed, with higher frequencies or titers of NAbs toward several individual strains for NT mothers when the clade B-infected or non-clade B-infected mothers were analyzed separately. Our study confirms that the breadth of maternal NAbs is not associated with protection of infants from infection.

INTRODUCTION

Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) is the leading source of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in children. In the absence of preventive measures, transmission may occur during pregnancy (in utero), during labor or delivery (intrapartum), or after birth, through breastfeeding. Maternal neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) can cross the placental barrier, reaching high levels in the fetus at the end of pregnancy and protecting the infant against infection with numerous pathogens (12, 30). Maternal antibodies are therefore among the selective host factors that could play a role in limiting transmission of HIV to the infant. Conflicting results have been obtained concerning the role of maternal NAbs in reducing MTCT of HIV (3, 6, 14, 19, 20, 33). Supporting a role for maternal NAbs in limiting MTCT of HIV-1, a few molecular studies have suggested that transmitted viruses are escape variants resistant to autologous maternal plasma (9, 40).

Since we are faced with the difficulty of identifying correlates of protection, a major obstacle that still impairs the design of efficient HIV-1 vaccine immunogens, the MTCT model offers the opportunity to explore whether some specific neutralizing antibodies are associated with protection. Indeed, MTCT may be compared to a natural challenge in which someone is exposed to HIV in the presence of preexisting antibodies. The results of passive immunization experiments in the macaque model have demonstrated that human broadly neutralizing monoclonal NAbs can fully protect macaques from HIV infection after exposure to simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) through intravenous, mucosal, and oral routes (1, 8, 13, 15, 16, 21, 22, 24). However, the current SHIV models, which include only a few HIV Envs, provide data limited to protection against a very restricted number of isolates and therefore have limitations in addressing the hypervariability of HIV. One of the advantages of studies performed in the context of MTCT is to provide evidence of protection from a wide spectrum of naturally occurring variants. We previously hypothesized that broadly cross-neutralizing heterologous antibodies would protect babies against intrapartum HIV transmission, and working with a homogeneous population in Thailand, we identified an association between higher titers of NAbs against a CRF01_AE primary isolate, MBA—belonging to the predominant clade in Thailand—and lower rates of intrapartum transmission (3, 31). Discrepancies within all published studies led us to conduct an additional study of a large population of mother-infant pairs infected by viruses of different clades. Here we examined the breadth and levels of NAbs in 114 untreated HIV-1-infected mothers who were enrolled in the French perinatal cohort (ANRS cohort CO1/CO11), using a panel of 10 informative primary isolates of 6 different clades, in order to identify potential correlates of protection in the context of MTCT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

Since 1985, the French perinatal cohort EPF (Enquête Périnatale Française; ANRS cohort CO1/CO11) has prospectively enrolled around 17,000 HIV-infected women delivering infants in 90 centers throughout France (37, 38), with this initiative including constitution of a maternal biobank. This cohort study was approved, according to French laws, by the Cochin Hospital Institutional Review Board and the French computer database watchdog commission (Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés).

We performed a matched case-control study among the 382 HIV-1-infected women enrolled in EPF between 1990 and 1996 who met the following criteria: they did not receive antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy, they did not breastfeed their infants, and frozen maternal serum was available in the EPF biobank. All transmitting (T) mothers (cases; n = 57) were included in the present study. For each transmitting mother, we selected a nontransmitting (NT) control mother of similar geographical origin (France, sub-Saharan Africa, or other origin) who delivered in the same obstetrical ward at the most proximal date (controls; n = 57).

The maternal serum samples that were used for neutralization assays were obtained at the time of delivery and before peripartum zidovudine (ZDV) infusion for the few women who received this treatment.

Demographic data (age and geographical origin), mode of delivery, gestational age at entry and at delivery, twinship, primiparity, CD4+ T-cell counts at delivery, infant gender, and peripartum and/or postnatal ZDV therapy were recorded prospectively (Table 1). Initially, viral loads (VL) were not available because they were not yet determined regularly at that time. However, since maternal VL is the factor most highly associated with transmission (17, 23), we retrospectively tried to document VL in the maternal plasma at delivery. Frozen plasma was still available, albeit in small amounts, for only 43 T mothers and 40 NT mothers. Plasma samples were tested at a 1:10 dilution in a real-time HIV-1 assay (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL), increasing the quantification cutoff from 40 copies/ml to 400 copies/ml.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studied population (a subsample of the ANRS EPF survey)

| Characteristic | No. (%) of individuals with characteristic |

P valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (T; n = 57) | Controls (NT; n = 57) | ||

| Year of delivery | |||

| 1990–1993 | 51 (89.5) | 52 (91.2) | 0.75PC |

| 1994–1996 | 6 (10.5) | 5 (8.8) | |

| HIV subtype | |||

| B | 34 (59.6) | 34 (59.6) | 1PC |

| Non-B | 23 (40.4) | 23 (40.4) | |

| Agea (yr) | |||

| <25 | 13 (25.0) | 15 (28.3) | 0.91F |

| 25–34 | 39 (75.0) | 38 (71.7) | |

| Twinship | |||

| Yes | 4 (7.0) | 0 (0) | 0.12F |

| No | 53 (93.0) | 57 (100) | |

| Primiparitya | |||

| Yes | 32 (56.1) | 24 (42.9) | 0.16PC |

| No | 25 (43.9) | 32 (57.1) | |

| Geographical origin | |||

| France | 32 (56.1) | 32 (56.1) | 1PC |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 25 (43.9) | 25 (43.9) | |

| HIV diagnosis before pregnancy | |||

| Yes | 27 (47.4) | 31 (54.4) | 0.45PC |

| No | 30 (52.6) | 26 (45.6) | |

| Gestational age (wk) at bookinga | |||

| <14 | 21 (41.2) | 19 (39.6) | 0.98PC |

| 14–27 | 22 (43.1) | 21 (43.8) | |

| ≥28 | 8 (15.7) | 8 (16.7) | |

| Gestational age (wk) at delivery | |||

| ≥37 | 50 (87.7) | 56 (98.3) | 0.09F |

| 33–36 | 4 (7.0) | 1 (1.7) | |

| ≤32 | 3 (5.3) | 0 (0) | |

| CD4+ T-cell count (mm3)a,b | |||

| <200 | 8 (14.8) | 4 (8.5) | 0.33PC |

| 200–350 | 8 (14.8) | 4 (8.5) | |

| >350 | 38 (70.4) | 39 (83.0) | |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| Elective caesarean | 5 (8.8) | 3 (5.3) | 0.041F |

| Emergency caesarean | 11 (19.3) | 3 (5.3) | |

| Vaginal | 41 (71.9) | 51 (89.4) | |

| Infant gender | |||

| Female | 26 (45.6) | 26 (45.6) | 1PC |

| Male | 31 (54.4) | 31 (54.4) | |

| Peripartum ZDV infusion | |||

| Yes | 2 (3.5) | 3 (5.3) | 1F |

| No | 55 (96.5) | 54 (94.7) | |

| Postnatal ZDV prophylaxis | |||

| Yes | 8 (14.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0.032F |

| No | 49 (86.0) | 56 (98.3) | |

| Period of transmission | |||

| In utero | 16 | ||

| Peripartum | 29 | ||

| Unknown | 12 | ||

Missing data explain why the total number is not reached.

At delivery or last available determination.

PC, Pearson's χ2 test; F, Fisher's exact test. Data in bold indicate statistical significance.

The period of transmission (intrapartum or in utero) was determined as follows: infants were considered to have been infected intrapartum if initial PCR (proviral DNA) or attempts of HIV isolation by cell coculture within 7 days after birth were negative and subsequent assays were positive. They were considered to have been infected in utero if assays were positive within the first 7 days of life.

Maternal viruses were subtyped by both V3 serotyping (4) and phylogenetic analysis of a 425-bp gp41 fragment obtained by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (7), as done in a previous study (31).

All experiments were performed blindly.

Neutralization assay and virus panel.

Neutralization assays were carried out with TZM-bl cells. The virus panel included 10 primary isolates selected for their moderate (tier 2) or low (tier 3) sensitivity to neutralization. There were four primary isolates (FRO, GIL, MBA, and KON) of four different clades (B, F, CRF01_AE, and CRF02_AG, respectively) that we had used in previous studies (3, 31). We added six primary isolates, including four viruses (94UG103, 92BR020, 93IN905, and 92TH021, of clades A, B, C, and CRF01_AE, respectively) identified as indicators of cross-clade neutralization (35) and two moderately resistant viruses (BIG and 92RW020, of clades B and A, respectively) (2, 35). This virus panel included viruses that were resistant to almost all of the broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies that we tested (2G12, b12, 2F5, 4E10, PG9, and PG16) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Neutralizing activity of each mother's serum was tested in duplicate using four 3-fold serial dilutions (from 1:20 to 1:540). Briefly, aliquots of 50 μl of the virus dilution corresponding to 100 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 11 μl of each dilution of heat-inactivated mother's serum. The mixture was then used to infect 10,000 TZM-bl cells (26, 39) in the presence of 30 μg/ml DEAE-dextran. Infection levels were determined after 48 h by measuring the mean value of luciferase activities of cell lysates. The IC50, defined as the reciprocal of the serum dilution required to reduce the number of relative light units (RLUs) by 50%, was determined 2 days after infection with 100 TCID50. Neutralizing activity of the human monoclonal antibodies was tested using the same methodology, starting at 50 μg/ml for 2G12, b12, 2F5, and 4E10 and at 10 μg/ml for PG9 and PG16. Specificity of the assays was assessed using pseudotyped HIV-1 particles carrying the amphotropic Moloney murine leukemia virus (Mo-MLV) envelope protein as a target (27), with a pool of HIV-negative sera as a serum control.

Breadth scores.

Breadth scores were calculated for each maternal serum sample to compare neutralization between cases and controls, following the procedures described in several previous reports (5, 10, 20, 25, 28, 32). Briefly, the NAb breadth score represents the number of viruses (out of 10) that a given serum sample neutralized at an IC50 that was higher than the median IC50 for that virus across all 114 serum samples. A breadth score of +1 was given if the IC50 was above the median IC50, and a score of 0 was given if the IC50 was below the median value. The overall breadth score for a given serum sample was determined by summing the scores for all 10 viruses tested.

Dendrogram and heat map.

A heat map of the IC50s for maternal serum samples was generated, and clustering of the isolates was analyzed based on their neutralization profiles toward all 114 sera. A dendrogram was created using statistical and multivariate analysis software (XLStat 2011; Addinsoft).

Statistical analysis.

Sociodemographic, clinical, and biological characteristics of case (T) and control (NT) mothers were compared using Pearson's χ2 test and Fisher's exact test as appropriate.

Titer was transformed into a 2-class variable, defined as “neutralizing activity” if the titer was detectable (≥20) or “no neutralizing activity” if the titer was below the limit of detection for various strains. Proportions of neutralizing activity were compared between maternal B and non-B groups by use of the χ2 test and between cases and controls by use of the McNemar test. Antibody titers, mean numbers of strains neutralized, and breadth scores were compared between cases and controls, using paired Student's t test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. IC50s below the limit of detection (<20) were assigned to half the limit of detection. The association between transmission status and titer or neutralizing activity was tested overall and separately for the B and non-B groups and the in utero and peripartum transmission groups.

All statistical analyses were performed by using Stata statistical software (Stata/SE V11.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the T and NT populations.

Fifty-seven transmitting mothers (cases) and 57 nontransmitting mothers (controls) were included in the study. Among the 57 case mothers, 29 mothers (50.9%) transmitted HIV-1 intrapartum, and 16 mothers (28.1%) transmitted the virus in utero (infant blood was positive by PCR or virus isolation within the first week). The data were not available for the 12 remaining cases. Based on data obtained through both serotyping for first-line screening and genotyping for confirmation and precise typing, 32 case-control mother pairs were infected by subtype B variants (56.1%), and 21 pairs were infected by non-B viruses (36.8%). Although the case mothers were matched with control mothers of similar geographical origin, there were 4 pairs that were discrepant based on the infecting genotype (7.0%). In these 4 pairs, the T mothers were infected by B variants, whereas the matched NT mothers were infected by non-B viruses. The env sequence-based genotype was obtained for 48 of the 114 samples (42.1%), including 17 from non-B infections. The low percentage of sequences that were obtained after RT-PCR might have been due to suboptimal long-term storage of the serum samples. The 17 precisely identified non-B infections were due to variants related to clades A (n = 3), D (n = 3), F (n = 1), H (n = 1), J (n = 1), CRF01_AE (n = 1), CRF02_AG (n = 5), CRF45_cpx (n = 1), and U (n = 1).

The main clinical and biological characteristics of T and NT mothers are summarized in Table 1. There were more premature and caesarean deliveries among case mothers than among control mothers (P = 0.09 and P = 0.041, respectively). Although relatively rare in our population, which was recruited before 1996, postnatal ZDV prophylaxis was significantly more frequent in case mothers than in control mothers (P = 0.03). There was no statistically significant difference in maternal CD4+ T-cell counts between T and NT mothers. Among the 83 pregnant women whose plasma samples were available for VL determination, 27 of 40 NT mothers (67.5%) had VL below the limit of detection, compared to 16 of 43 T mothers (37.2%) (P = 0.004; χ2 test), and the median VL was lower for NT mothers (1.70 log10 copies/ml) than for T mothers (2.77 log10 copies/ml). However, the observed VL were much lower than expected for a population of untreated women (17), suggesting that the long-term storage of the plasma samples rendered this analysis questionable.

Characterization of HIV-specific NAbs in mothers.

None of the serum samples neutralized pseudotyped HIV-1 particles carrying the amphotropic Mo-MLV envelope protein, and none of the HIV-1 strains on the panel was neutralized by the control pool of HIV-negative sera. Most of the serum samples showed a cross-clade neutralizing activity. Fifteen sera (13.2%) exhibited large cross-neutralizing activity against the 10 strains, with the IC50 determinable at least at the first serum dilution (1:20). KON (CRF02_AG), GIL (F), and BIG (B), which were neutralized by 56 (49.1%), 60 (52.6%), and 65 (57.0%) sera, respectively, were the most resistant strains. In contrast, 94UG103 (A), 92BR020 (B), and FRO (B), which were neutralized by 111 (97.4%), 106 (93.0%), and 108 (94.7%) sera, respectively, were the most sensitive strains (Table 2). Detection of NAbs toward B or non-B isolates did not differ significantly between sera from mothers infected by B or non-B viruses, except for the 92RW20 strain, which was more sensitive to neutralization by non-B sera than by B sera (P = 0.02). Figure S1 in the supplemental material, which shows an IC50 heat map of the log-transformed IC50s for the maternal plasma samples and for each isolate, illustrates that the clusters were not linked to the genotype of the strains but rather to their intrinsic sensitivity to neutralization.

Table 2.

Neutralizing activity in serum according to the HIV subtype infecting the mothers

| Subtype and strain | No. (%) of mothers with neutralizing activity in serum |

P value by Pearson χ2 testa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| B group (n = 68) | Non-B group (n = 46) | ||

| B | |||

| 92BR020 | 63 (92.7) | 43 (93.5) | 0.87 |

| BIG | 39 (57.4) | 26 (56.5) | 0.93 |

| FRO | 64 (94.1) | 44 (95.7) | 0.72 |

| A | |||

| 92RW020 | 44 (64.7) | 39 (84.8) | 0.02 |

| 94UG103 | 66 (97.1) | 45 (97.8) | 0.80 |

| C | |||

| 93IN105 | 57 (83.8) | 41 (89.1) | 0.42 |

| F | |||

| GIL | 33 (48.5) | 27 (58.7) | 0.29 |

| CRF01_AE | |||

| 92TH021 | 49 (72.1) | 36 (78.3) | 0.46 |

| MBA | 63 (92.7) | 41 (89.1) | 0.52 |

| CRF02_AG | |||

| KON | 30 (44.1) | 26 (56.7) | 0.19 |

Data in bold indicate statistical significance.

HIV-1 specific NAbs in transmitting and nontransmitting mothers.

Although there was a higher frequency of detection of NAbs in NT mothers than in T mothers, globally or for each isolate except for three strains (BIG, 92TH021, and KON), the differences were not statistically significant (Table 3). This was confirmed through analysis of breadth scores, which were not different between NT and T mothers (5.8 versus 5.2) (Table 3). In analyzing the data according to the subtype infecting the mothers (B versus non-B), the proportion of neutralizing antibodies toward strain 92BR020 was significantly higher in nontransmitting than in transmitting mothers for the subtype B subpopulation (P = 0.046) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Table 3.

Neutralizing activity in maternal serum samples from transmitting and nontransmitting mothers

| Subtype and strain | No. (%) of mothers with neutralizing activity in seruma |

P value by McNemar χ2 test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmitters (n = 57) | Nontransmitters (n = 57) | ||

| B | |||

| 92BR020 | 51 (89.5) | 55 (96.5) | 0.10 |

| BIG | 33 (57.9) | 32 (56.1) | 0.81 |

| FRO | 52 (91.2) | 56 (98.3) | 0.10 |

| A | |||

| 92RW020 | 40 (70.2) | 43 (75.4) | 0.47 |

| 94UG103 | 54 (94.7) | 57 (100) | 0.08 |

| C | |||

| 93IN105 | 47 (82.5) | 51 (89.5) | 0.16 |

| F | |||

| GIL | 29 (50.9) | 31 (54.4) | 0.65 |

| CRF01_AE | |||

| 92TH021 | 43 (75.4) | 42 (73.7) | 0.83 |

| MBA | 51 (89.5) | 53 (93.0) | 0.41 |

| CRF02_AG | |||

| KON | 28 (49.1) | 28 (49.1) | 1 |

The mean number of strains neutralized (95% confidence interval [95% CI]) was 7.5 (6.9 to 8.1) for transmitters and 7.9 (7.5 to 8.3) for nontransmitters (P = 0.23 by paired Student's t test). The mean breadth score (95% CI) was 5.2 (4.5 to 6.0) for transmitters and 5.8 (5.1 to 6.6) for nontransmitters (P = 0.20 by paired Student's t test).

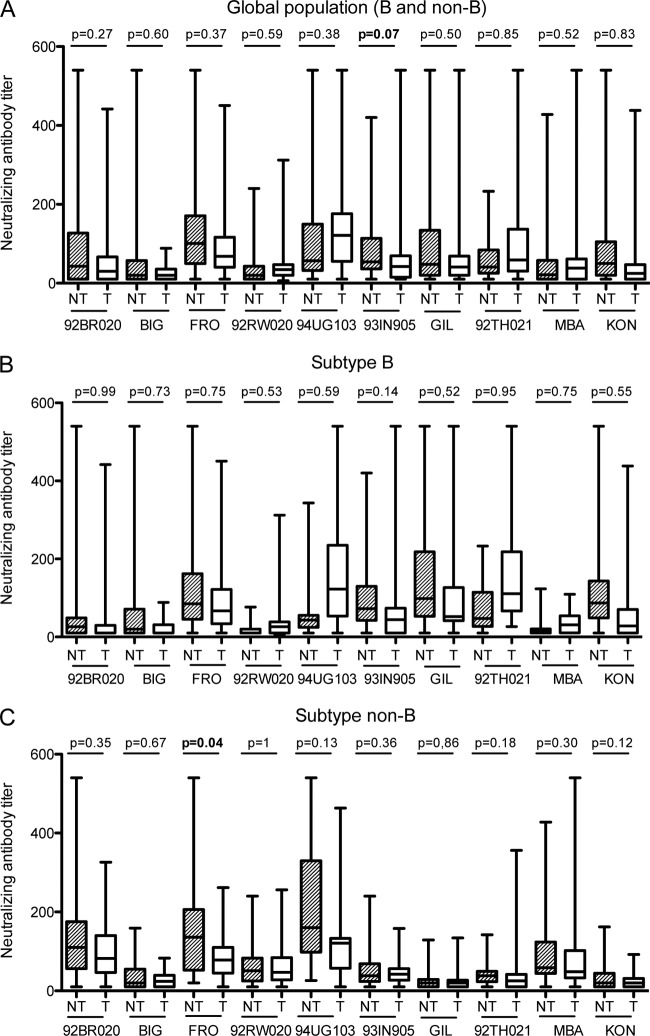

We also observed higher titers of NAbs toward most of the strains in NT mothers than toward those in T mothers (Fig. 1A), but the differences were not statistically significant except for the 93IN105 isolate, for which the result was just above the limit of significance (mean IC50, 66.4 versus 50.4; P = 0.07). However, different features were observed in analyzing the data by subpopulation according to the subtype of the strains that infected the mothers. Titers of NAbs did not differ significantly between NT and T mothers for the subtype B subpopulation (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the mean NAb titers were higher in NT mothers than in T mothers for all the strains of the non-B subpopulation (Fig. 1C), and significantly so for the FRO strain (P = 0.04).

Fig 1.

Comparison of neutralizing antibody titers against 10 primary isolates in sera from transmitting (T) and nontransmitting (NT) mothers. Box plots show the distribution of maternal antibody titers; for each distribution, the horizontal lines represent the lower adjacent, 25th, median, 75th, and upper adjacent percentiles. (A) Comparison of NAb titers in T and NT mothers from the entire population (n = 114). (B) Comparison of NAb titers in T and NT mothers from the subtype B-infected population (n = 68). (C) Comparison of NAb titers in T and NT mothers from the non-subtype B-infected population (n = 46). NAb titers were compared using the Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test.

Neither the frequency of detection of NAbs nor the breadth score was statistically different in NT versus T mothers in an analysis of the data according to timing of transmission, i.e., in utero or intrapartum (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). However, there was still a trend toward a higher frequency of NAbs toward two strains (92BR020 and FRO) in NT mothers than in mothers who transmitted the virus intrapartum (P = 0.08).

DISCUSSION

Maternal antibodies of the IgG class are transferred passively to the fetus, reaching high levels at the end of pregnancy, and therefore protect the infant from infections with numerous pathogens during the first months of life. In the absence of breastfeeding, HIV-1 acquisition from mothers may occur in utero but mainly occurs at the end of pregnancy, during labor and delivery. Therefore, this physiological context represents a unique setting in which to examine the potential of neutralizing antibodies to prevent HIV infection and thereby to identify correlates of protection. However, conflicting results have been obtained concerning the role of maternal NAbs in reducing MTCT of HIV (3, 6, 14, 19, 20, 33). Many factors may be involved to explain the discrepant results, either at the virus level or at the population level. At the virus level, a few studies have analyzed neutralizing activity toward autologous variants, whereas most studies have analyzed neutralizing activity toward heterologous strains. In considering heterologous neutralization, discrepancies might be attributed to the composition of the panels, since HIV isolates exhibit a high degree of variability in sensitivity to neutralization (11, 34, 35). At the population level, breastfeeding mothers were excluded in some studies but not in others, and timing of transmission was not documented systematically. In addition, the predominant subtypes were different according to the geographical areas of the various studies. Supporting a role for NAbs in limiting MTCT of HIV-1, a few studies showed that viruses transmitted to infants were escape variants resistant to neutralization by autologous maternal sera (9, 40, 41), yet this finding was not confirmed by others (18, 29, 36).

In the present study, our population was among the largest that have been analyzed to date, and none of the mothers breastfed their infants. All were enrolled before 1996 and did not benefit from the prophylactic measures that have been implemented since then. Therefore, despite a few cases of mothers who received a peripartum ZDV infusion and children who received postnatal ZDV prophylaxis, the mother-infant pairs were representative of a natural history situation. It must be considered that there will be no additional opportunity to explore the role of NAbs in the absence of preventive measures, because every HIV-1-infected woman henceforth should benefit from chemoprophylaxis of MTCT. Only biological material collected from historical cohorts will remain relevant to this situation. Transmitters were matched with controls selected based on a similar geographical origin and on delivery in the same obstetrical ward at the most proximal date. The comparison of the groups did not show any major differences except for higher frequencies in the transmitter group for both caesarean delivery and postnatal ZDV prophylaxis, both of which are interventions that might have been dictated by risk factors for transmission identified in the mothers at the end of pregnancy. Considering these potential caveats, multivariate analyses were included in the statistical analyses. A limitation of our study is that we did not include maternal VL in the multivariate analysis. Indeed, remaining frozen plasma for VL determination was not available for the entire population, and although higher VL were observed in T mothers than in NT mothers, the observed values were much lower than expected. We believe that the probable degradation of viral RNA after long-term storage under suboptimal conditions rendered the relevance of the VL data questionable. Sixty percent and 40% of the women were infected by B and non-B viruses, respectively. This allowed us to perform both global analyses and subanalyses by subgroup, although we were conscious that the non-B group was highly heterogeneous in terms of subtypes. The virus panel included 10 primary isolates selected for moderate or low sensitivity to neutralization, excluding highly neutralization-sensitive strains that would be less relevant to predicting protection.

The first conclusion that we report here is that the breadth of maternal NAbs clearly does not seem to be associated with a lower risk of infant infection. Although we cannot assert that the entire neutralizing activity present in the maternal sera was passively transferred to the infants, it can be assumed, based on the biology of antibodies of the IgG class, that the neutralizing activity of maternal sera is representative of the neutralizing activity present in infant sera (12, 30). Our study confirms previous data that we obtained for a homogeneous Thai population (3) and recent data that were obtained by others for a population of Kenyan infants (20). Therefore, these three large studies, conducted on three continents where the circulating strains are different and using different panels of indicator strains, have brought forth a fully concordant answer.

However, our previous studies suggested that particular HIV-1 variants might be indicators of neutralizing antibodies associated with in vivo protection. Indeed, we reported that NAbs toward a CRF01_AE isolate, MBA, were associated with a lower rate of MTCT in Thailand (3, 31). Therefore, the next question we asked was as follows: are there indicator strains that can provide a surrogate measure of protective antibodies? Our results showed both a higher frequency of detection and higher titers of NAbs toward most of the strains tested in nontransmitting mothers than in transmitting mothers, although the differences did not reach statistical significance. At the level of the entire population, only differences in NAb titers toward isolate 93IN105 were close to being statistically significant. When the populations were separated according to the infecting subtype, i.e., B versus non-B, NAb titers were significantly higher toward isolate FRO for nontransmitting mothers infected with the non-B population. Qualitatively, the frequency of Nab detection toward 92BR020 was significantly higher for nontransmitting mothers infected with the B population. Altogether, these data support the hypothesis that NAbs to particular strains might be associated with a lower rate of MTCT of HIV-1. Taking into consideration both the present study and our previous studies performed on Thai populations (3, 31), the data would mean that this association is dependent on both the isolate and the population. It should also be considered that other factors, such as a higher ability of viruses related to some clades, particularly clades C and A, to induce stronger NAb responses, might introduce an additional degree of complexity to these analyses (11).

In conclusion, while we confirmed that the breadth of HIV-1 neutralizing activity seems not to be associated with a lower rate of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1, we cannot exclude that particular HIV-1 variants may provide a surrogate measure of protective antibodies. Our data indicate that the identification of such indicator strains would necessitate large studies concerning only homogeneous populations in order to limit confounding factors that would dilute the relevant information. We still consider MTCT to be a unique model of natural challenge in the presence of passively acquired antibodies that could help to define characteristics of a protective antibody response toward a broad range of naturally occurring HIV-1 variants.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA et les Hépatites (ANRS, Paris, France) and by Sidaction (Paris, France).

We thank all the contributors to the ANRS French perinatal cohort (CO1/CO11), particularly the mothers who agreed to participate. We thank Pascal Poignard and IAVI for providing us with PG9 and PG16. We thank Sylvie Brunet, Florence Colin, Sylvie Delgeon, and Laurence Giraudeau for their valuable technical assistance. The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: pNL4.3.LUC.R-E− from Nathaniel Landau; TZM-bl cells from John C. Kappes, Xiaoyun Wu, and Tranzyme Inc.; 92BR020, 94UG103, 92TH021, and 92RW020 from the UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization; and 93IN905 from Robert Bollinger.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 July 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Baba TW, et al. 2000. Human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies of the IgG1 subtype protect against mucosal simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. Nat. Med. 6:200–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barin F, et al. 2004. Interclade neutralization and enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 identified by an assay using HeLa cells expressing both CD4 receptor and CXCR4/CCR5 coreceptors. J. Infect. Dis. 189:322–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barin F, et al. 2006. Revisiting the role of neutralizing antibodies in mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. J. Infect. Dis. 193:1504–1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barin F, et al. 2006. Human immunodeficiency virus serotyping on dried serum spots as a screening tool for the surveillance of the AIDS epidemic. J. Med. Virol. 78(Suppl 1):S13–S18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blish CA, et al. 2008. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 superinfection occurs despite relatively robust neutralizing antibody responses. J. Virol. 82:12094–12103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bongertz V, et al. 2001. Vertical HIV-1 transmission: importance of neutralizing antibody titer and specificity. Scand. J. Immunol. 53:302–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brand D, et al. 2004. First identification of HIV-1 groups M and O dual infections in Europe. AIDS 18:2425–2428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burton DR, et al. 2011. Limited or no protection by weakly or nonneutralizing antibodies against vaginal SHIV challenge of macaques compared with a strongly neutralizing antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:11181–11186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dickover R, et al. 2006. Role of maternal autologous neutralizing antibody in selective perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 escape variants. J. Virol. 80:6525–6533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Doria-Rose NA, et al. 2009. Frequency and phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus envelope-specific B cells from patients with broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 83:188–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dreja H, et al. 2010. Neutralization activity in a geographically diverse East London cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients: clade C infection results in a stronger and broader humoral immune response than clade B infection. J. Gen. Virol. 91:2794–2803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Englund J, Glezen WP, Piedra PA. 1998. Maternal immunization against viral disease. Vaccine 16:1456–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferrantelli F, et al. 2004. Complete protection of neonatal rhesus macaques against oral exposure to pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus by human anti-HIV monoclonal antibodies. J. Infect. Dis. 189:2167–2173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hengel RL, et al. 1998. Neutralizing antibody and perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 14:475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hessell AJ, et al. 2009. Broadly neutralizing human anti-HIV antibody 2G12 is effective in protection against mucosal SHIV challenge even at low serum neutralizing titers. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000433 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hessell AJ, et al. 2009. Effective, low-titer antibody protection against low-dose repeated mucosal SHIV challenge in macaques. Nat. Med. 15:951–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. John GC, et al. 2001. Correlates of mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transmission: association with maternal plasma HIV-1 RNA load, genital HIV-1 DNA shedding, and breast infections. J. Infect. Dis. 183:206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kishko M, et al. 2011. Genotypic and functional properties of early infant HIV-1 envelopes. Retrovirology 8:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lathey JL, et al. 1999. Lack of autologous neutralizing antibody to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and macrophage tropism are associated with mother-to-infant transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 180:344–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lynch JB, et al. 2011. The breadth and potency of passively acquired human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific neutralizing antibodies do not correlate with the risk of infant infection. J. Virol. 85:5252–5261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mascola JR, et al. 2000. Protection of macaques against vaginal transmission of a pathogenic HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus by passive infusion of neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Med. 6:207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mascola JR, et al. 1999. Protection of macaques against pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus 89.6PD by passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 73:4009–4018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mofenson LM, et al. 1999. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in women treated with zidovudine. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parren PW, et al. 2001. Antibody protects macaques against vaginal challenge with a pathogenic R5 simian/human immunodeficiency virus at serum levels giving complete neutralization in vitro. J. Virol. 75:8340–8347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Piantadosi A, et al. 2009. Breadth of neutralizing antibody response to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is affected by factors early in infection but does not influence disease progression. J. Virol. 83:10269–10274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Platt EJ, Wehrly K, Kuhmann SE, Chesebro B, Kabat D. 1998. Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macrophagetropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:2855–2864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reiser J, et al. 1996. Transduction of non-dividing cells using pseudotypes defective high-titer HIV type 1 particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:15266–15271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rodriguez SK, et al. 2007. Comparison of heterologous neutralizing antibody responses of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)- and HIV-2-infected Senegalese patients: distinct patterns of breadth and magnitude distinguish HIV-1 and HIV-2 infections. J. Virol. 81:5331–5338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Russell ES, et al. 2011. The genetic bottleneck in vertical transmission of subtype C HIV-1 is not driven by selection of especially neutralization-resistant virus from the maternal viral population. J. Virol. 85:8253–8262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Safrit JT, et al. 2004. Immunoprophylaxis to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 35:169–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Samleerat T, et al. 2009. Maternal neutralizing antibodies against a CRF01_AE primary isolate are associated with a low rate of intrapartum HIV-1 transmission. Virology 387:388–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sather DN, et al. 2009. Factors associated with the development of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 83:757–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Scarlatti G, et al. 1993. Mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: correlation with neutralizing antibodies against primary isolates. J. Infect. Dis. 168:207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seaman MS, et al. 2010. Tiered categorization of a diverse panel of HIV-1 Env pseudoviruses for assessment of neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 84:1439–1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Simek MD, et al. 2009. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite neutralizers: individuals with broad and potent neutralizing activity identified by using a high-throughput neutralization assay together with an analytical selection algorithm. J. Virol. 83:7337–7348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thenin S, et al. 2012. Envelope glycoproteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants issued from mother-infant pairs display a wide spectrum of biological properties. Virology 426:12–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tubiana R, et al. 2010. Factors associated with mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 despite a maternal viral load <500 copies/ml at delivery: a case-control study nested in the French perinatal cohort (EPF-ANRS CO1). Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:585–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Warszawski J, et al. 2008. Mother-to-child HIV transmission despite antiretroviral therapy in the ANRS French perinatal cohort. AIDS 22:289–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wei X, et al. 2002. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1896–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wu X, et al. 2006. Neutralization escape variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are transmitted from mother to infant. J. Virol. 80:835–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang H, et al. 2010. Functional properties of the HIV-1 subtype C envelope glycoprotein associated with mother-to-child transmission. Virology 400:164–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.