Abstract

Germline LKB1 mutations cause Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, a hereditary disorder that predisposes to gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis and several types of malignant tumors. Somatic LKB1 alterations are rare in sporadic cancers, however, a few reports showed the presence of somatic alterations in a considerable fraction of lung cancers. To determine the prevalence and the specificity of LKB1 alterations in lung cancers, we examined a large number of lung cancer cell lines and lung adenocarcinoma (AdC) specimens for the alterations. LKB1 genetic alterations were frequently detected in the cell lines (21/70, 30%), especially in non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) (20/51, 39%), and were significantly more frequent in cell lines with KRAS mutations. Point mutations were detected only in AdCs and large cell carcinomas, whereas homozygous deletions were detected in all histological types of lung cancer. Among lung AdC specimens, LKB1 mutations were found in seven (8%) of 91 male smokers but in none of 64 females and/or nonsmokers, and were significantly more frequent in poorly differentiated tumors. The difference in the frequency of LKB1 alterations between cell lines and tumor specimens was likely to be owing to masking of deletions by the contamination of noncancerous cells in the tumor specimens. These results indicate that somatic LKB1 genetic alterations preferentially occur in a subset of poorly differentiated lung AdCs that appear to correlate with smoking males.

Keywords: LKB1, lung cancer mutation, deletion, smoking, poor differentiation

Introduction

Germline mutations of the LKB1 gene (also known as STK11) cause Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (PJS), an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis and mucocutaneous melanin pigmentation (Hemminki et al., 1998; Jenne et al., 1998). PJS patients also have an increased risk for intestinal and extraintestinal malignancies, including breast, ovarian, pancreatic and lung cancers (Hemminki, 1999; Westerman et al., 1999). The majority of germline LKB1 mutations result in truncation of the protein, leading to its dysfunction, thus, the LKB1 gene has been considered to act as a tumor suppressor in PJS. The LKB1 gene is implicated in the regulation of multiple biological processes, including cell-cycle arrest, p53-mediated apoptosis and induction of cell polarity (Baas et al., 2004; Alessi et al., 2006). Therefore, LKB1 has been also predicted to have a potential of a tumor suppressor in sporadic tumors. However, somatic LKB1 gene alterations has been identified in a small fraction of those tumors, such as malignant melanomas, pancreatic and breast cancers (Bignell et al., 1998; Avizienyte et al., 1999; Guldberg et al., 1999; Su et al., 1999). Recently, it was reported that half of lung adenocarcinoma (AdC) cell lines and one-third of primary lung AdCs harbor somatic LKB1 gene alterations, whereas other histological types of lung cancer, including squamous cell carcinoma (SqC) and small cell carcinoma (SCLC) do not (Sanchez-Cespedes et al., 2002; Carretero et al., 2004). A more recent study showed that large cell carcinoma (LCC) cell lines also had LKB1 genetic alterations (Zhong et al., 2006). Given the results from these studies, somatic LKB1 gene alterations might occur preferentially in lung AdCs and LCCs. However, the pathogenic significance of LKB1 genetic alterations in lung cancers is not well understood. Thus, we investigated a larger number of lung cancer cell lines as well as primary and metastatic lung AdCs for the genetic alterations. We further analysed the correlation of the genetic alterations with clinicopathological characteristics of patients with lung AdC.

Results

Genetic alterations of the LKB1 gene in lung cancer cell lines

We first examined 70 lung cancer cell lines for LKB1 genetic alterations. The cell lines consisted of 31 AdCs, 2 adenosquamous carcinomas (AdSqCs), 11 SqCs, 7 LCCs and 19 SCLCs. Exons 1–9 covering the entire coding region and exon–intron boundaries of the LKB1 gene were analysed for mutations and deletions/insertions by genomic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and direct sequencing. Homozygous deletions of regions upstream of the LKB1 gene were also examined. Point mutations and homozygous deletions were detected in nine and 13 cell lines, respectively. One cell line, Ma29, had both a point mutation and a homozygous deletion. Thus, in total, 21 of the 70 cell lines (30%) showed genetic alterations of the LKB1 gene (Table 1). Point mutations were detected only in AdCs and LCCs, whereas homozygous deletions were detected in all histological types of lung cancer.

Table 1.

Frequencies of LKB1 genetic alterations in lung cancer cell lines

| Histological type | Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Point mutation | Homozygous deletion | Total | |

| AdC | 7/31 (23) | 7/31 (23) | 13/31 (42)a |

| AdSqC | 0/2 (0) | 1/2 (50) | 1/2 (50) |

| SqC | 0/11 (0) | 3/11 (27) | 3/11 (27) |

| LCC | 2/7 (29) | 1/7 (14) | 3/7 (43) |

| SCLC | 0/19 (0) | 1/19 (5) | 1/19 (5) |

| Total | 9/70 (13) | 13/70 (19) | 21/70 (30) |

Abbreviations: AdC, adenocarcinoma; AdSqC, adenosquamous carcinomas; LCC, large cell carcinoma; SCLC, small cell carcinoma; SqC, squamous carcinoma.

In cell line Ma29, both a point mutation and a homozygous deletion were detected.

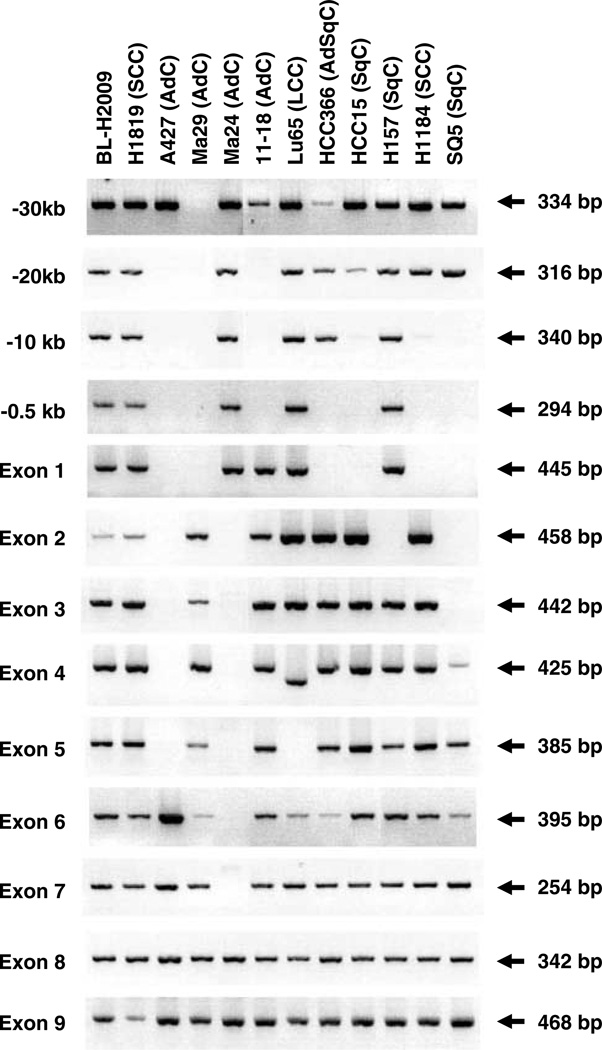

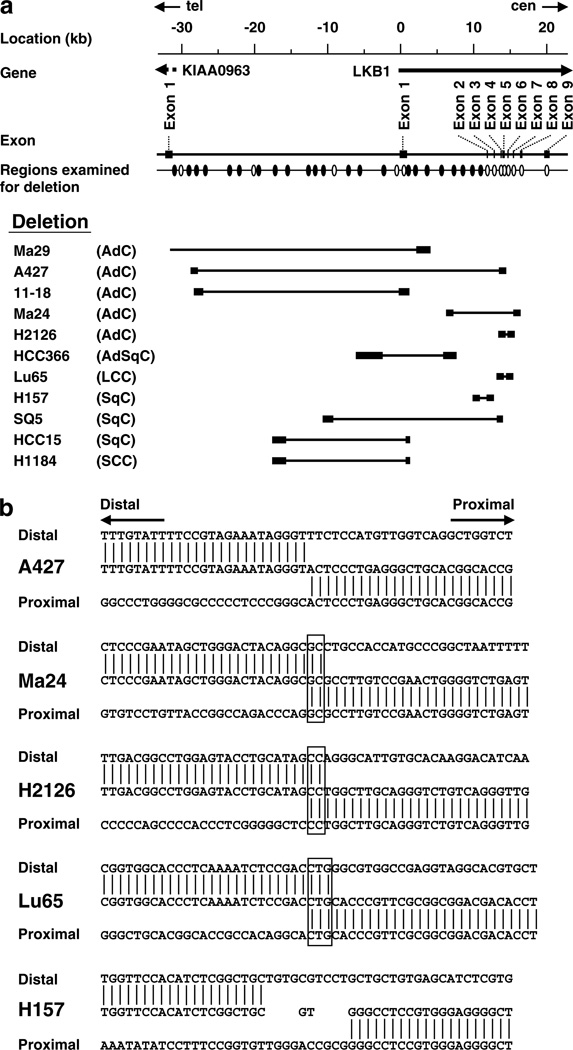

The types of genetic alterations are summarized in Table 2. Point mutations detected in PC7, Ma29 and PC13 were missense mutations, and those in A549, H23 and Ma25 were nonsense mutations. HCC44 had a point mutation in combination with a 1-bp insertion, resulting in a missense mutation coupled with a frame-shift mutation. The remaining two-point mutations, detected in VMRC-LCD and HCC515, respectively, were splice site mutations. In all the cell lines with point mutations, only the sequences for mutant allele were detected and those for the wild-type allele were not detected. The sequence analysis also revealed 1-bp homozygous deletions leading frameshift mutations in two other AdC cell lines, H1395 and H2122. Large homozygous deletions, excluding the 1-bp deletions, were detected in 11 cell lines (Figure 1). In seven (Ma29, A427, 11–18, HCC366, SQ5, HCC15 and H1184) of the 11 cell lines, the deleted regions commonly included exon 1 and/or a 0.5 kb upstream region, which was considered as a promoter region of the LKB1 gene (Hearle et al., 2005). The remaining four cell lines, Ma24, H2126, Lu65 and H157, had intragenic deletions. In Lu65, exon 5 was not amplified and exon 4 was amplified with a shorter size. Sequencing of the shorter-sized product revealed that Lu65 had a 93-bp deletion from exon 4 to exon 5.

Table 2.

Table 2 of LKB1 alterations in lung cancer cell lines

| Genetic alteration | Cell line | Histological type | Site/region | Nucleotide change | mRNA expression | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point mutation | A549 | AdC | exon 1 | 109C > T | + | Q37 Ter |

| HCC44 | AdC | exon 1 | 153G > C + 1C ins. | + | M51I, 52 → 162 stop | |

| PC7 | AdC | exon 6 | 747A > C + 749G > T | + | T250P | |

| Ma29a | AdC | exon 6 | 847C > G | − | L283V | |

| H23 | AdC | exon 8 | 996G > A | + | W322 Ter | |

| VMRC-LCD | AdC | IVS 3 | −1G > T | + | Y156-E199 del., 200 → 286 stop | |

| HCC515 | AdC | IVS 5 | + 1G > T | + | V236-L245 del., 246 → 265 stop | |

| PC13 | LCC | exon 5 | 668A > T | + | E223V | |

| Ma25 | LCC | exon 6 | 782C > G | + | Y261 Ter | |

| Deletion | H1395 | AdC | exon 1 | 165–169 1G del. | + | 56 → 63 stop |

| H2122 | AdC | exon 6 | 837–842 1C del. | + | 279 → 286 stop | |

| Ma29a | AdC | ~ exon 1 | − | |||

| A427 | AdC | −29 kb ~ exon 4 | 43 308 bp del. | − | ||

| 11–18 | AdC | −25 kb ~ −0.5 kb | − | |||

| Ma24 | AdC | exon 2 ~ exon 7 | 9058 bp del. | + | K97N, E98-S307 del. | |

| H2126 | AdC | exon 4 ~ exon 6 | 1194 bp del. | + | Y156-G268 del., 269 → 271 stop | |

| HCC366 | AdSqC | −2.5 kb ~ exon 1 | − | |||

| Lu65 | LCC | exon 4 ~ exon 5 | 93 bp del. | + | G196-L201 del. | |

| H157 | SqC | exon 2 | 1498 bp del. | + | E98-G155 del. | |

| SQ5 | SqC | −9kb ~ exon 3 | − | |||

| HCC15 | SqC | −15 kb ~ exon 1 | − | |||

| H1184 | SCLC | −15 kb ~ exon 1 | − | |||

| Unknown | H322 | AdC | + | E98-G155 del. | ||

| H1437 | AdC | + | E98-G155 del. |

This cell line has both a point mutation and a large deletion.

Figure 1.

Homozygous deletions of the LKB1 gene in lung cancer cell lines. DNA fragments for exons and upstream regions of the LKB1 gene amplified by genomic PCR were fractionated by a 3% agarose gel. Sizes of the fragments are shown on the right. A homozygous deletion in H2126, which was demonstrated in a previous report (Carretero et al., 2004), is not shown.

Altered LKB1 expression in lung cancer cell lines

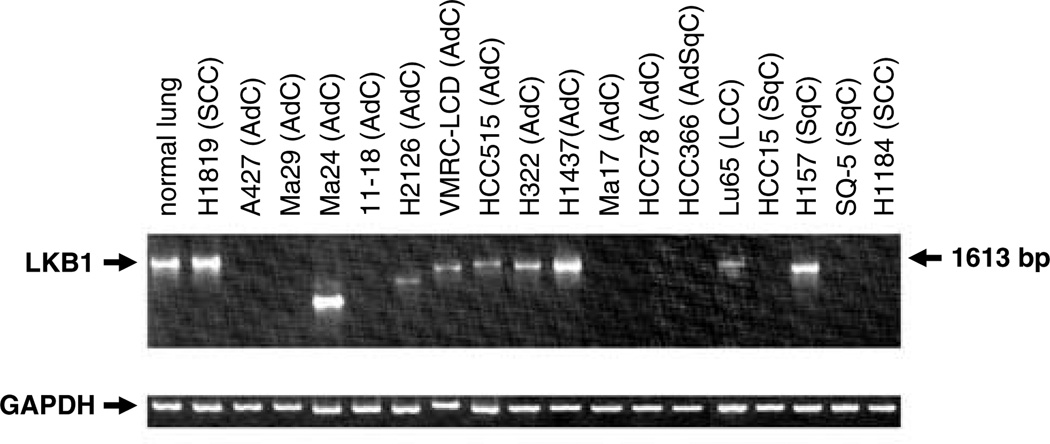

To evaluate the expression status of the LKB1 gene in lung cancer cell lines, reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR) analysis was performed in all 70-lung cancer cell lines. Normal-sized and shorter-sized RT–PCR products were found in 53 (76%) and eight cell lines (11%), respectively. The remaining nine cell lines (13%) showed the absence of the products, implying no or decreased expression of LKB1 mRNA (Figure 2). The nine cell lines without RT–PCR products included the seven cell lines, in which exon 1 and/or a 0.5 kb upstream region of the LKB1 gene were homozygously deleted, suggesting that the LKB1 gene is not expressed owing to the lack of promoter sequence in these cell lines (Table1 and Figure 1). Ma17 and HCC78 also showed the absence of RT–PCR products, although their genetic alterations were unknown.

Figure 2.

Expression of the LKB1 gene in lung cancer cell lines. RT–PCR was performed as described in Materials and methods. RT–PCR products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel. GAPDH amplification was used for a loading control.

To confirm genetic alterations and to investigate causative genetic changes for the expression of mutated and truncated transcripts, the normal-sized and shorter-sized RT–PCR products were sequenced. The intraexonal point mutations in seven cell lines and the 1-bp deletions in two cell lines were all confirmed in this analysis. In two cell lines with splice site mutations, abnormal mRNA splicing was observed. In VMRC-LCD carrying a point mutation at the 3′ splice site of intron 3, exon 3 was spliced directly to exon 5 skipping exon 4. In HCC515 carrying a point mutation at the 5′ splice site of intron 5, exon 5 was spliced to exon 6 skipping the terminal 29 bp in exon 5. Both the aberrantly spliced transcripts led to frameshifts, thus, were expected to synthesize truncated proteins. In four cell lines with intragenic homozygous deletions, interstitially deleted sequences were also shown in cDNA. In Ma24, in agreement with a deletion of exons 2–7 in genomic DNA, cDNA also lacked the sequence for these exons. In H2126, RT–PCR products were also shorter and lacked the sequence for exons 4–6. The abnormal cDNA sequence in H2126 defined in this study was identical to that in a previous report (Carretero et al., 2004). In Lu65, the breakpoint for deletion in genomic DNA was consistent with that in cDNA. In H157, cDNA lacked the sequence for exons 2 and 3, whereas only exon 2 was homozygously deleted in genomic DNA. The sequence for exons 2 and 3 was also deleted in H322 and H1437, although no genetic alteration was detected in these cell lines. This interstitial deletion was in-frame, thus, was expected to synthesis a small protein.

Deletion mapping of the LKB1 gene in lung cancer cell lines

To more precisely determine deleted regions in the LKB1 locus, large deletions detected in 11 cell lines were mapped at a 1 ~ 3-kb resolution by genomic PCR (Figure 3a). Most deletions, excluding a deletion in Ma29, were located in the 45-kb region between 29-kb upstream and intron 7 of the LKB1 gene. The region 0.5–2.5-kb upstream of the LKB1 gene was deleted in seven of the 11 cell lines, suggesting that this is a common region of deletions in lung cancer.

Figure 3.

(a) Deletion map of the LKB1 locus. Regions analysed by genomic PCR are shown by ovals. Results of the PCR analysis for the regions indicated by open ovals are shown in Figure 1. Distal and proximal breakpoints for deletions are shown by closed boxes, respectively. The bar put between the closed boxes indicates the extent of deletion in each cell line. In Ma29, the distal breakpoint was undetermined. (b) DNA sequences of breakpoint junctions for deletions in or upstream of the LKB1 gene. Junctions without insertion or overlap of nucleotides (A427), with overlaps of 2- or 3-bp nucleotides (Ma24, H2126 and Lu65) and with insertion of 2-bp nucleotides (H157) are shown, respectively. Overlapped nucleotides are boxed.

To elucidate the molecular process of interstitial deletions in the LKB1 locus, DNA sequences of break-points for such deletions were determined. DNA fragments including breakpoint junctions were amplified by genomic PCR using primers recognizing regions flanking the breakpoints. DNA sequences of breakpoint junctions were able to be determined in A427, Ma24, H2126 and H157 in addition to Lu65 (Figure 3b). Of the five junctions, 2- or 3-bp nucleotides overlapped at three junctions. At two other junctions, DNAs were directly joined or were joined with insertion of two nucleotides. There were no junctions joined by homologous recombination utilizing repetitive sequences.

Both a point mutation in exon 6 and a homozygous deletion of exon 1 and an upstream sequence were detected in the Ma29 cell line. No sequence for the wild-type allele was detected in this cell line. Thus, it was deduced that both a point mutation in exon 6 and an interstitial deletion including exon 1 had occurred in one allele, and the other allele was deleted by a larger deletion including exon 6 and this interstitial deletion. As no LKB1 mRNA was detected in Ma29, the biological significance of the mutation was unclear. In five other cell lines with homozygous deletions, breakpoint junctions were successfully determined. Thus, it was revealed that interstitial deletions had occurred in one allele and the other allele was lost by larger deletions including their respective interstitial deletions. In the remaining six cell lines with homozygous deletions, the nature of homozygous deletions was unclear.

Genetic alterations of the LKB1 gene in primary and metastatic lung AdCs

We further examined primary and metastatic lung AdC cases for the genetic alterations (Table 3). First, 106 stage I primary lung AdCs and 25 brain metastases were examined. In stage I tumors, only one tumor (1%) had a mutation, a missense mutation coupled with a frameshift mutation owing to 1-bp insertion in exon 1. On the other hand, LKB1 mutations were detected in three (12%) of the 25 metastases; two nonsense mutations in exons 4 and 6, respectively, and one frameshift mutation owing to a 1-bp deletion in exon 6. Next, an additional set of primary lung AdCs, for which both RNAs and genomic DNAs were available for analysis, was examined for interstitial deletions as well as mutations in the LKB1 gene. In 24 cases, a cDNA fragment covering the entire coding region of LKB1 was amplified by nested RT–PCR and directly sequenced. If mutations were detected in RT–PCR products, the presence of identical mutations in genomic DNA was confirmed by genomic PCR and direct sequencing. The cases consisted of 13 cases pathologically diagnosed as stage I, 5 as stage II and 6 as stage III. LKB1 mutations were detected in three (13%) of the 24 cases. These three cases (100T, 170T and 171T) were pathologically diagnosed as stages IB, IA and IIB, respectively. In case 100T, a lack of the terminal 151-bp in exon 1 was shown in RT–PCR products, and the presence of a point mutation at the 5′ splice-donor site of intron 1 was revealed by genomic DNA sequencing. Therefore, the lack of the terminal 151-bp in exon 1 was concluded to be a consequence of abnormal mRNA splicing owing to a splice donor site mutation. Case 170T showed three base substitutions coupled with a 1-bp insertion leading a frameshift, and case 171T had a nonsense mutation identical to that detected in a lung cancer cell line, A549. As interstitial deletions in the LKB1 gene were not identified by RT– PCR analysis in the tumor specimens, long-range PCR analysis was performed on genomic DNA to explore large deletions in the LKB1 gene in these 24 AdCs. However, no deletions were identified in the tumors. All of the nucleotide changes detected in tumor specimens were confirmed to be somatic mutations by sequencing DNA from the corresponding noncancerous tissues.

Table 3.

LKB1 gene alterations in primary and metastatic lung adCs

| Tumor | Material | Frequency (%) | Types of LKB1 gene alterations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Smokers | Sample (Stage) |

Exon or intron |

Nucleotide change | Effect | ||

| Primary tumor | |||||||

| Set 1 (Stage I) | DNA only | 1/106 (1) | 1/62 (2) | 10–22 (IA) | exon 1 | 150G > T, 152T > A, 153–157 1Gins. | M51K, 53 → 162 stop |

| Set 2 (stage I–III) | DNA/RNA | 3/24 (13) | 3/10 (30) | 100T (IB) | IVS 1 | +1G > T | G47-K96 del., 97 → 102 stop |

| 170T (IA) | exon 1 | 150 1Tins., 152T > G, 156–157GG > TT | 51 → 162 stop | ||||

| 171T (IIB) | exon 1 | 109C > T | Q37Ter | ||||

| Brain metastases | DNA only | 3/25 (12) | 3/19 (16) | N011T | exon 4 | 475C > T | Q159Ter |

| N111T | exon 6 | 766G > T | E256Ter | ||||

| BM6 | exon 6 | 837–842 1C del. | 279 → 286 stop | ||||

Correlation of LKB1 mutations with clinicopathological characteristics of patients with lung AdC

We further analysed the correlation of LKB1 mutations with several clinicopathological characteristics of patients with lung AdC. In particular, information on gender, age, smoking history and differentiation of tumors was available in all cases subjected to LKB1 mutation analysis. Thus, an association study of LKB1 mutations with these variables was performed among 155 AdC cases (Table 4). LKB1 mutations were present only in males and smokers, and not in females and nonsmokers. Moreover, LKB1 mutations were significantly more frequent in poorly differentiated AdCs than in well or moderately differentiated ones.

Table 4.

Correlations of LKB1 genetic alterations with clinicopathological characteristics of patients with lung adC

| Clinicopathological feature | Subset | Number | LKB1 mutation (%) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | ||||

| Gender | Male | 96 | 7 (7) | 89 (93) | 0.04 |

| Female | 59 | 0 (0) | 59 (100) | ||

| Age | < 62 | 73 | 3 (4) | 70 (96) | > 0.99 |

| ≥ 62 | 82 | 4 (5) | 78 (95) | ||

| Smoking history | Smoker | 91 | 7 (8) | 84 (92) | 0.04 |

| Nonsmoker | 64 | 0 (0) | 64 (100) | ||

| Differentiation | Well | 73 | 1 (1) | 72 (99) | (Well vs mod.) > 0.99 |

| Moderately | 48 | 0 (0) | 48 (100) | (Well vs poorly) < 0.01 | |

| Poorly | 34 | 6 (18) | 28 (82) | (Mod. vs poorly) < 0.01 | |

| EGFR mutation | + | 54 | 0 (0) | 54 (100) | 0.10 |

| − | 101 | 7 (7) | 94 (93) | ||

| KRAS mutation | + | 15 | 1 (7) | 14 (93) | 0.52 |

| − | 140 | 6 (4) | 134 (96) | ||

| p53 mutation | + | 52 | 3 (6) | 49 (94) | 0.30 |

| − | 79 | 1 (1) | 78 (99) | ||

Fisher’s exact test.

Correlation of LKB1 genetic alterations with EGFR, KRAS or p53 mutations

We also analysed the correlation of LKB1 genetic alterations with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), KRAS and p53 mutations in 70 lung cancer cell lines. Types of EGFR, KRAS and p53 mutations as well as those of LKB1 genetic alterations detected in these cell lines are summarized in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Table S1). EGFR mutations and KRAS mutations showed mutually exclusive correlations, as reported (Kosaka et al., 2004). LKB1 genetic alterations were significantly more frequent in cell lines with KRAS mutations (8/12, 67%) than those without (13/58, 22%), whereas there was no significant correlation or inverse correlation between LKB1 genetic alterations and EGFR or p53 mutations (Table 5). A correlation between LKB1 and KRAS alterations was also significant, when the analysis was limited to the 31 AdC cell lines only. LKB1 genetic alterations were detected in six of eight (75%) AdC cell lines with KRAS mutations but only in seven of 23 (30%) AdC cell lines without (P = 0.04). We also examined all 155 AdC cases for EGFR and KRAS mutations, and the 106 stage I AdCs and the 25 brain metastases for p53 mutations. Among the seven cases with LKB1 mutations, one case had both a KRAS mutation and a p53 mutation, and two other cases had p53 mutations. EGFR mutations were not detected in any of the seven cases. However, no significant correlation or inverse correlation between LKB1 mutations and the other gene mutations was observed in these AdC cases (Table 4).

Table 5.

Correlations of LKB1 genetic alterations with EGFR, KRAS or p53 mutations in lung cancer cell lines

| Gene | Mutation | Number | LKB1 mutation/deletion (%) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | ||||

| EGFR | + | 5 | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 0.63 |

| − | 65 | 19 (29) | 46 (71) | ||

| KRAS | + | 12 | 8 (67) | 4 (33) | < 0.005 |

| − | 58 | 13 (22) | 45 (78) | ||

| p53 | + | 56 | 17 (30) | 39 (70) | > 0.99 |

| − | 14 | 4 (29) | 10 (71) | ||

Abbrevaition: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor

Fisher’s exact test.

Discussion

In the present study, 70 lung cancer cell lines and 155 lung AdC cases were examined for LKB1 genetic alterations. Of the lung cancer cell lines examined, LKB1 genetic alterations were detected in 21 cell lines (30%). The alterations were more frequently detected in NSCLCs (20/51, 39%) than in SCLCs (1/19, 5%). The high incidence of LKB1 genetic alterations in NSCLC cell lines was previously reported by Carretero et al. (2004). They reported the presence of LKB1 alterations only in AdCs among various histological types of lung cancer cell lines. Another study showed that two LCC cell lines, H157 and H460, had LKB1 genetic alterations (Zhong et al., 2006), although H157 was histologically classified as a SqC in this study, and H460 as an AdC in Carretero et al. (2004). The present study revealed that point mutations commonly occur in AdC and LCC, whereas homozygous deletions occur not only in AdC and LCC but also in other histological types, such as SqC and SCLC. Thus, this is the first report, to our knowledge, demonstrating the presence of LKB1 genetic alterations in SqC and SCLC. Among 21 lung cancer cell lines with the genetic alterations, missense mutations were detected only in three cell lines. As, in other sporadic cancers, missense mutations of the gene were reported to be relatively frequent compared with nonsense mutations or insertions/deletions (Launonen, 2005), the high frequencies of nonsense mutations and insertions/deletions are considered distinctive of lung cancer. The difference in the types of LKB1 genetic alteration, in addition to that in the frequencies of the alterations, between lung cancer and other sporadic cancers raises a possibility that LKB1 alterations might be induced by environmental factors, such as smoking. This is supported by a previous report showing that allelic losses or gains of chromosome 19p, on which the LKB1 gene maps, were more frequent in lung AdCs from smokers than those from nonsmokers (Sanchez-Cespedes et al., 2001).

Mutations of the LKB1 gene were also detected in tumor specimens of lung AdCs. The frequency of the genetic alterations was 1% of stage I cases (1/106), 13% of another stage IIII cases (3/24) and 12% of brain metastases (3/25). All of the genetic alterations detected were point mutations or a 1-bp deletion, and large deletions were not detected. The difference in the frequency of large deletions between tumor specimens and cell lines is likely to be owing to masking of large deletions by the contamination of noncancerous cells in the tumor specimens. Recently, LKB1 deletions, which cannot be detected by conventional methods, were reported to be detected by a highly sensitive method, called multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, in 14–16% of PJS patients (Hearle et al., 2006; Volikos et al., 2006). Thus, it is possible that such deletions may occur in a considerable fraction of primary lung AdCs. The frequencies of point mutations and 1-bp deletions were also lower in tumor specimens than in cell lines. As LKB1 plays a role in the regulation of cell cycle and apoptosis, cell lines might be preferentially established from LKB1-mutated lung cancer cells, which are likely to acquire proliferative and survival advantages in vitro by LKB1 inactivation.

In the present study, LKB1 genetic alterations were detected in pathological stage I or II cases. Thus, the genetic alterations are not necessarily a late event during lung AdC progression. This result was consistent with a previous immunohistochemical study showing marked reduction of LKB1 protein in 10% of AAH, a precursor lesion of lung AdCs (Ghaffar et al., 2003). As all of the LKB1 genetic alterations detected in our analysis of tumor specimens were nonsense mutations or frameshift mutations, the expression of truncated LKB1 proteins was also predicted to occur relatively early in the development of lung AdCs. Furthermore, LKB1 genetic alterations were detected only in males and smokers, indicating a correlation between the occurrence of genetic alterations and tobacco exposure. Additionally, LKB1 genetic alterations were more frequently detected in poorly differentiated AdCs. Therefore, defects in differentiation of AdC cells with LKB1 genetic alterations might be associated with the functional loss of LKB1 proteins in the cells. Consistent with our result, a recent study revealed that a lung cancer cell line, A427, with a large deletion in the LKB1 gene, possessed a greater invasive potential compared with a cell line expressing the wild-type LKB1 gene, and forced expression of wild-type LKB1 in A427 led to reduction of this potential (Upadhyay et al., 2006).

Frequent alterations of the LKB1 gene in lung cancer have made it possible for us to analyse the correlation of the alterations with the status of p53, EGFR and KRAS mutations. LKB1 genetic alterations were significantly frequent in lung cancer cell lines with KRAS mutations. This correlation was particularly observed in lung AdC cell lines. As KRAS mutations are considered to be relevant to smoking, the frequent coexistence of LKB1 genetic alterations and KRAS mutations supports our result of frequent LKB1 genetic alterations in lung AdCs from smokers. In tumor specimens, a case with a KRAS mutation also had a LKB1 mutation. However, there was no tumor carrying both LKB1 genetic alterations and EGFR mutations. Because EGFR mutations occur frequently in lung AdCs of females and nonsmokers (Kosaka et al., 2004; Shigematsu and Gazdar, 2006), lung AdCs with LKB1 genetic alterations, all of which were detected in males and smokers, are likely to be a different subset from those with EGFR mutations. On the other hand, several studies revealed that LKB1 leads to cell growth inhibition owing to G1 cell-cycle arrest through a p53-dependent mechanism (Tiainen et al., 2002), and to apoptosis through its physical interaction with p53 (Karuman et al., 2001). Among 21 lung cancer cell lines and four lung AdC specimens with LKB1 genetic alterations, 17 (81%) and three (75%) had p53 mutations, respectively. The frequent coexistence of LKB1 genetic alterations and p53 mutations, as well as that of LKB1 genetic alterations and KRAS mutations, are suggested to be involved in aggressiveness of lung cancer. Further analyses are needed to elucidate the pathogenic significance of the interaction of these genes in lung carcinogenesis.

We demonstrated here that LKB1 genetic alterations occur frequently in lung cancers, especially in NSCLCs with KRAS mutations and with smoking histories, and are significantly associated with poorly differentiated phenotypes of lung AdCs. Our results indicate the involvement of somatic LKB1 genetic alterations in the development of a subset of poorly differentiated lung AdCs that appear to correlate with smoking males.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Seventy lung cancer cell lines, consisting of 51 NSCLCs and 19 SCLCs, were used as listed in Supplementary Table S1. The 51 NSCLCs consisted of 31 AdCs, two AdSqCs, 11 SqCs and seven LCCs. Additionally, in six AdCs (H1395, H1437, H2009, H2087, H2122 and H2347) and four SCCs (H209, H2107, H2141, and H2171), corresponding lymphoblast cell lines were available for analysis. Detailed information about H- and HCC-series cell lines have been described elsewhere (Burbee et al., 2001). PC-, Lu- and Ma-series cell lines were provided by Drs Y Hayata (Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan), T Terasaki (Kanagawa Institute of Technology, Kanagawa, Japan) and S Hirohashi (National Cancer Center Research Institute, Tokyo, Japan) and M Takada (National Hospital Organization Kinkichuo Chest Medical Center, Osaka, Japan), respectively. Cell lines were also obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA), the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (Tokyo, Japan), and the RIKEN BioResource Center (Tsukuba, Japan). Genomic DNA was isolated as described previously (Kishimoto et al., 2005), and polyadenylated RNA was extracted with a Fast Track mRNA isolation kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA).

Tumor specimens

One hundred thirty primary tumors, 25 brain metastases and corresponding noncancerous tissues were obtained at surgery or at autopsy from lung AdC patients treated at the National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. Primary tumors consisted of a set of 106 stage I primary tumors, for which genomic DNAs were available for analysis, and another set of 24 stage I–III primary tumors, for which both genomic DNAs and RNAs were available for analysis. All of the 130 primary tumors, 16 of the 25 brain metastases and corresponding noncancerous tissues were macrodissected and stored at −80°C until DNA or RNA extraction. Genomic DNAs were prepared described previously (Kishimoto et al., 2005). Total RNA was extracted with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The remaining nine brain metastases and corresponding noncancerous tissues were fixed with methanol and embedded in paraffin. Cancerous and noncancerous cells of these nine cases were microdissected using the Pixcell Laser Capture Microdissection system (Arcturus Engineering, Mountain View, CA, USA), and their genomic DNAs were extracted as described previously (Matsumoto et al., 2006a).

Mutation and deletion analysis of the LKB1 gene

PCR primers were designed to amplify each exon in the LKB1 gene. Ten nanograms of DNA from the cell lines and the macrodissected materials were used for PCR amplification. For the microdissected materials, nested PCR was carried out after initial PCR using 100 pg of DNA. PCR products were cycle-sequenced using an ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and an ABI PRISM 3700 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR primers were also set to examine the cell lines for homozygous deletions of upstream regions of the LKB1 gene. Homozygous deletions were confirmed by multiplex PCR using the IRF1 locus on chromosome arm 5q as a reference (Kishimoto et al., 2005). PCR primer sequences and PCR conditions are available on request.

Expression analysis of the LKB1 gene

Polyadenylated RNA or total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA by using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA conversion mixtures were subjected to PCR amplification of the entire coding region of LKB1 for 35 cycles. Primers used for the amplification were 5′-GGACTGACGTGTAGAACAAT-3′ in the noncoding region of exon 1 and 5′-CGTGGTCGGCACAGAAG CA-3′ in exon 10. PCR products were directly sequenced in both directions. The gene encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was amplified to estimate the efficiency of cDNA synthesis.

Mutation analysis of the EGFR, KRAS and p53 genes

All of the 106 stage I primary lung AdCs and 19 of the 25 brain metastases of lung AdC were previously examined for mutations of exons 18–21 in the EGFR gene and of exons 1 and 2 in the KRAS gene (Matsumoto et al., 2006a, b). The remaining tumors and all the 70 cell lines were also examined for these mutations by genomic PCR and direct sequencing as described previously (Matsumoto et al., 2006a). Mutations of exons 2–11 in the p53 gene were previously analysed using the 106 stage I cases and 38 of the 70 cell lines (Fujita et al., 1999; Tomizawa et al., 2002). All of the 25 brain metastases and the remaining cell lines were examined for mutations of exons 4–8 in the p53 gene by genomic PCR and direct sequencing as described previously (Park et al., 2003).

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the association of LKB1 genetic alterations with clinicopathological factors or mutations of the EGFR, KRAS and p53 genes. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan for the 3rd-term Comprehensive 10-year Strategy for Cancer Control and for Cancer Research (16-1), from the program for promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (NiBio), and from National Cancer Institute Lung Cancer SPORE (Grant Number: P50CA70907).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc).

References

- Alessi DR, Sakamoto K, Bayascas JR. Lkb1-dependent signaling pathways. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:137–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avizienyte E, Loukola A, Roth S, Hemminki A, Tarkkanen M, Salovaara R, et al. LKB1 somatic mutations in sporadic tumors. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:677–681. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65314-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas AF, Smit L, Clevers H. LKB1 tumor suppressor protein: PARtaker in cell polarity. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignell GR, Barfoot R, Seal S, Collins N, Warren W, Stratton MR. Low frequency of somatic mutations in the LKB1/Peutz–Jeghers syndrome gene in sporadic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1384–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbee DG, Forgacs E, Zochbauer-Muller S, Shivakumar L, Fong K, Gao B, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A in lung and breast cancers and malignant phenotype suppression. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:691–699. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.9.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretero J, Medina PP, Pio R, Montuenga LM, Sanchez-Cespedes M. Novel and natural knockout lung cancer cell lines for the LKB1/STK11 tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2004;23:4037–4040. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Kiyama M, Tomizawa Y, Kohno T, Yokota J. Comprehensive analysis of p53 gene mutation characteristics in lung carcinoma with special reference to histological subtypes. Int J Oncol. 1999;15:927–934. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.5.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffar H, Sahin F, Sanchez-Cepedes M, Su GH, Zahurak M, Sidransky D, et al. LKB1 protein expression in the evolution of glandular neoplasia of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2998–3003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldberg P, thor Straten P, Ahrenkiel V, Seremet T, Kirkin AF, Zeuthen J. Somatic mutation of the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome gene, LKB1/STK11, in malignant melanoma. Oncogene. 1999;18:1777–1780. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearle NC, Rudd MF, Lim W, Murday V, Lim AG, Phillips RK, et al. Exonic STK11 deletions are not a rare cause of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e15. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.036830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearle NC, Tomlinson I, Lim W, Murday V, Swarbrick E, Lim G, et al. Sequence changes in predicted promoter elements of STK11/LKB1 are unlikely to contribute to Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemminki A. The molecular basis and clinical aspects of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:735–750. doi: 10.1007/s000180050329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemminki A, Markie D, Tomlinson I, Avizienyte E, Roth S, Loukola A, et al. A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Nature. 1998;391:184–187. doi: 10.1038/34432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenne DE, Reimann H, Nezu J, Friedel W, Loff S, Jeschke R, et al. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel serine threonine kinase. Nat Genet. 1998;18:38–43. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuman P, Gozani O, Odze RD, Zhou XC, Zhu H, Shaw R, et al. The Peutz-Jegher gene product LKB1 is a mediator of p53-dependent cell death. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1307–1319. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto M, Kohno T, Okudela K, Otsuka A, Sasaki H, Tanabe C, et al. Mutations and deletions of the CBP gene in human lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:512–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, Kuwano H, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in lung cancer: biological and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8919–8923. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launonen V. Mutations in the human LKB1/STK11 gene. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:291–297. doi: 10.1002/humu.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S, Iwakawa R, Kohno T, Suzuki K, Matsuno Y, Yamamoto S, et al. Frequent EGFR mutations in noninvasive bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006a;118:2498–2504. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S, Takahashi K, Iwakawa R, Matsuno Y, Nakanishi Y, Kohno T, et al. Frequent EGFR mutations in brain metastases of lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006b;119:1491–1494. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MJ, Shimizu K, Nakano T, Park YB, Kohno T, Tani M, et al. Pathogenetic and biologic significance of TP14ARF alterations in nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;141:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00645-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Cespedes M, Ahrendt SA, Piantadosi S, Rosell R, Monzo M, Wu L, et al. Chromosomal alterations in lung adenocarcinoma from smokers and nonsmokers. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1309–1313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Cespedes M, Parrella P, Esteller M, Nomoto S, Trink B, Engles JM, et al. Inactivation of LKB1/STK11 is a common event in adenocarcinomas of the lung. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3659–3662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu H, Gazdar AF. Somatic mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway in lung cancers. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:257–262. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su GH, Hruban RH, Bansal RK, Bova GS, Tang DJ, Shekher MC, et al. Germline and somatic mutations of the STK11/LKB1 Peutz–Jeghers gene in pancreatic and biliary cancers. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1835–1840. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65440-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiainen M, Vaahtomeri K, Ylikorkala A, Makela TP. Growth arrest by the LKB1 tumor suppressor: induction of p21(WAF1/CIP1) Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1497–1504. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.13.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa Y, Kohno T, Kondo H, Otsuka A, Nishioka M, Niki T, et al. Clinicopathological significance of epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A at 3p21.3 in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2362–2368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay S, Liu C, Chatterjee A, Hoque MO, Kim MS, Engles J, et al. LKB1/STK11 Suppresses Cyclooxygenase-2 Induction and Cellular Invasion through PEA3 in Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7870–7879. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volikos E, Robinson J, Aittomaki K, Mecklin JP, Jarvinen H, Westerman AM, et al. LKB1 exonic and whole gene deletions are a common cause of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e18. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.039875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerman AM, Entius MM, de Baar E, Boor PP, Koole R, van Velthuysen ML, et al. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, 78-year follow-up of the original family. Lancet. 1999;353:1211–1215. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)08018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong D, Guo L, de Aguirre I, Liu X, Lamb N, Sun SY, et al. LKB1 mutation in large cell carcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2006;53:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.