Abstract

We present an integrated method that exploits extended time-lapse automated imaging to quantify dynamics of cell proliferation. Cell counts are fit with a Quiescence-Growth model that estimates rates of cell division, entry into quiescence and death. The model is constrained with rates extracted experimentally from the behavior of tracked single cells over time. We visualize the output of the analysis in Fractional Proliferation graphs, which deconvolve dynamic proliferative responses to perturbations into the relative contributions of dividing, quiescent (non-dividing) and dead cells. The method reveals that the response of “oncogene-addicted” human cancer cells to tyrosine kinase inhibitors is a composite of altered rates of division, death and entry into quiescence, challenging the notion that such cells simply ‘die’ in response to oncogene-targeted therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Proliferation is a fundamental property of living cells. Altering or controlling cell—proliferation often by chemical compounds—is a major goal of several disciplines, including oncology, tissue engineering, and developmental biology. Many current proliferation assays rely on surrogate measurements of cell number (e.g. total ATP or DNA content) rather than direct cell counts1. Moreover, since cells are not directly visualized in most proliferation assays, their states (dividing, quiescent, apoptotic) are unknown; a given proliferation curve could be the consequence of one of many combination of states. Proliferation assays are also typically performed with very few time points and rarely account for proliferation dynamics. Flow cytometry provides measurements at the single-cell level, including: cell cycle position 2, expression of proliferative markers, fractions of dead or dying cells 3, and division tracking by dye dilution 4. However, adherent cells must be detached for end point analysis and single cells cannot be tracked or individual cell histories recorded.

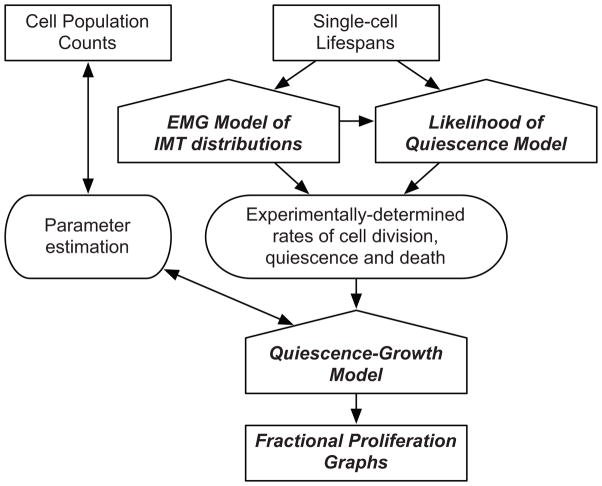

Here we describe a methodology to quantify dynamic changes in a proliferating cell population and to deconvolve fractional cell fates over time (Fig. 1). We label cells with a nuclear fluorescent protein, carry out extended time-resolved automated microscopy (typically for ~96 h and as long as 10 days), segment nuclei in image stacks to directly count cells and track single cells for determining cell lifespans and fates (Methods). The large image datasets require analysis with computational tools and newly developed mathematical models (Supplementary Notes 1 and 2) that utilize information at both the population and single-cell levels and integrate them into a model of cell proliferation dynamics (Fig. 1). Briefly, we fit cell count data obtained from time-lapse automated microscopy with a novel Quiescence-Growth model, which incorporates rates of cell division, entry into quiescence and death. The model is constrained with experimental rates derived from tracked single cells and its output is visualized in Fractional Proliferation graphs. These graphs resolve the dynamic change in total cell numbers into fractions of dividing and quiescent (non-dividing) cells.

Figure 1. The Fractional Proliferation methodology.

The principal inputs are cell population counts and metrics of single-cell fate obtained by automated time-lapse imaging. The Quiescence-Growth Model is fit to cell count data to estimate rates of cell division, death and entry into quiescence. These estimated rates are statistically bound and can be evaluated with the Quiescence-Growth model to provide initial insights into the underlying biology without requiring experimental determination of the rates. The EMG model of IMT distribution and the Likelihood of Quiescence models extract experimental rates of division and entry into quiescence from single-cell tracking data. Incorporating experimentally derived rates constrains the Quiescence Growth Model and produces Fractional Proliferation graphs that dynamically resolve the change in cell counts into fractions of dividing and quiescent cells.

RESULTS

Quiescence-Growth model of cell population dynamics

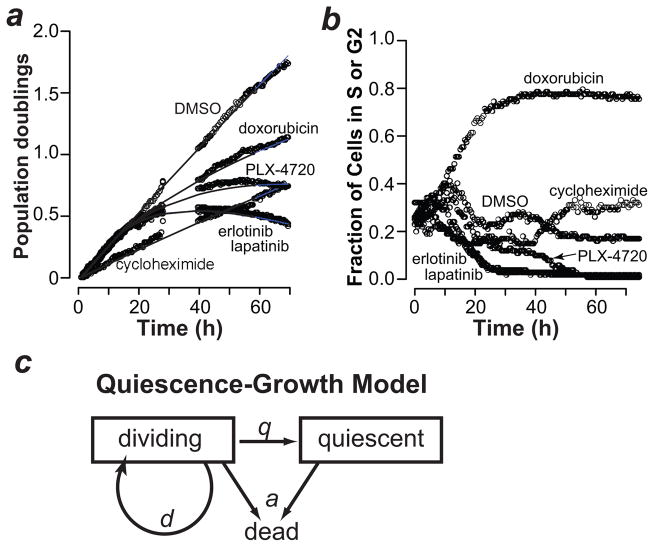

We used our approach to monitor the proliferation dynamics of drug-treated cells. Cell counts extracted from the image data show that vehicle-and cycloheximide-treated PC9 cells exhibit linear proliferation (in log scale). In contrast, treatment with erlotinib, lapatinib, PLX-4720 or doxorubicin resulted in nonlinear effects on proliferation of PC9 cells (Fig. 2a). We observed similar effects, in other cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 1). We analyzed the expression of a marker of S or G2 phase (mAG-geminin)5 in drug-treated cells: erlotinib, lapatinib and PLX-4720 induced arrest in G1 (or G0) and doxorubicin in S or G2 (Fig. 2b), suggesting a correlation between cell cycle arrest and nonlinear proliferation. We also observed this correlation in erlotinib-treated PC9 cells analyzed using flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b) and in MCF10A cells deprived of serum (Supplementary Figure 2c). Nonlinear population dynamics are traditionally modeled using logistic or Gompertz equations 6,7, which have been applied to cultured cells as well as tumors 8–10. A major assumption of these models is the idea of a “carrying capacity” representing the maximum size a population can reach in a given environment. There is no clear relationship between carrying capacity and the biological processes that affect cell population size, such as cell division, quiescence and death.

Figure 2. The Quiescence-Growth model explains nonlinear proliferation.

(a) The number of population doublings of PC9 cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) or the indicated drugs is shown as circles (see Methods for details). Cycloheximide, 250 ng/ml; erlotinib, 4 μM; lapatinib, 4 μM; PLX-4720, 16 μM; doxorubicin, 31 nM. The lines indicate Quiescence-Growth model fits to the data. (b) PC9 cells treated as in Fig. 2a (except 250 ng/ml doxorubicin) were analyzed for their expression of a marker of S or G2 phase (mAG-geminin) 5. (c) The Quiescence-Growth model considers two cellular compartments, dividing and non-dividing (quiescent). The dividing cell compartment is depleted at the rate of entry into quiescence (q), and replenished at the rate of division (d). A rate of death (a) depletes both compartments. The differential equations derived from the model are shown in Methods.

To explain the nonlinear proliferation dynamics using biologically relevant parameters, we constructed a “Quiescence-Growth” model that includes two compartments, a dividing and a non-dividing (which we term quiescent) population, with death occurring from both compartments (Fig. 2c, Methods, and Supplementary Notes 1,2). The equation derived from this model incorporates three parameters (Fig. 2c), rates of division (d), death (a) and entry into quiescence (q). The term “quiescence” in the Quiescence-Growth model reflects arrest at any position in the cell cycle. We applied the Quiescence-Growth model to fit the cell count data obtained from drug-treated PC9 cells (Fig 2a). PC9 response to CHX was linear and best explained by decreasing the rate of division (d). In contrast, proliferation in response to erlotinib, lapatinib and PLX-4720 is nonlinear and can only be explained by varying the q parameter, rate of entry into quiescence (Fig. 2a). Varying the q parameter also best fits the response to doxorubicin (Fig. 2a), known to cause arrest in G2 (Fig. 2b).

Data-derived Quiescence-Growth model parameters

Good fits of the cell count data with the Quiescence-Growth model may be achieved by different combinations of parameter values (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Software 1), particularly death and division rates, which oppose each other. We therefore constrained the model with experimentally measured rates from single cell tracking of time-lapse images.

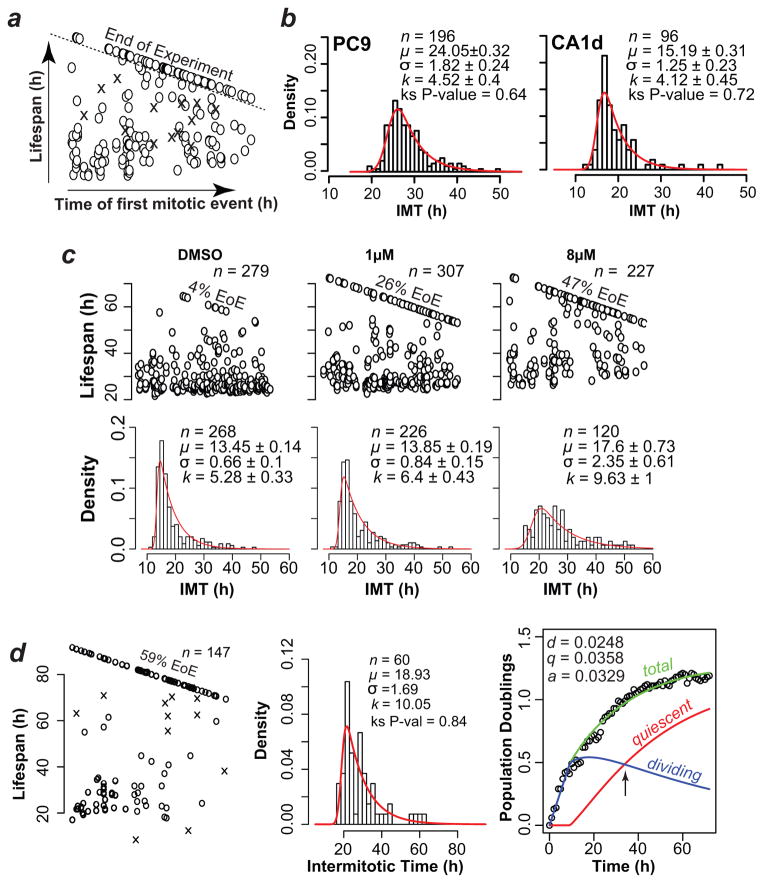

We first tracked single cells across time lapse image stacks to quantify observed cell lifespans, which are defined as the time between an initial mitotic event and: 1) a death event, 2) another mitotic event (defining an intermitotic time; IMT), or 3) the end of the experiment (EoE) (Fig. 3a, Methods and Supplementary Video 1). Cell lifespans demarcated by an initial mitotic event and the EoE may belong to either dividing or non-dividing (quiescent) fractions.

Figure 3. Interpretation of tracked single-cell data with mathematical models.

(a). Schematic example plot of tracked single cell lifespans. The data used in this example plot are shown in Fig. 3c (CA1d cells treated with 8μM erlotinib). Time of first mitotic event (birth time) is along the x-axis and cell lifespan along the y-axis. O, live cells; X, dead cells. Cells born during the experiment but reaching the end of experiment (EoE) without a second mitotic event are above the dashed line and are not included in IMT distributions. (b) Representative intermitotic time (IMT) distributions of untreated populations of the indicated cell types (shown as a density histogram). Distributions were fit to an EMG model. n = number of IMT in the distribution; μ =mean of the Gaussian component of EMG; σ = deviation of the Gaussian component of EMG; k= the mean of the exponential component of EMG. Values ± 95% confidence intervals. (c) Plots of single cell lifespans (top) and IMT distributions (bottom) of CA1d cells treated with indicated concentrations of erlotinib or vehicle (DMSO). (d) The plots show proliferation of CA1d cells treated with 16 μM erlotinib. The left panel shows single cell lifespans, the middle panel is the IMT distribution and the right panel is the Fractional Proliferation graph. The Fractional Proliferation graph (Methods) shows total cells (green), the fraction of dividing cells (blue) and the fraction of non-dividing or quiescent cells (red) over time. Arrow, time at which quiescent and dividing fractions are equal. Note that the death rate is not explicitly represented but is applied to both quiescent and dividing fractions.

For death rates, we identified death events by shrinkage/disintegration of nuclei (Supplementary Fig. 4a), tallied these events and converted them directly to rates (Methods).

For division rates, we first determined the variability of IMT in the population by examining IMT distributions, which are non-Gaussian by visual inspection (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Figs. 5,6), fail several statistical tests of normality (Supplementary Tables 2,3) and cause bias in the estimation of division rate if a simple mean value is used. We searched for model distributions that adequately capture the variability (Fig. 3b). Among several possible models we examined (Supplementary Table 2), an Exponentially Modified Gaussian (EMG) model 11 fits well the observed IMT distributions from a wide range of cells and conditions (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. 5,6), while minimizing the number of parameters to three. An additional benefit is that EMG model parameters are mathematically and biologically separable, i.e. their values are differentially affected by drugs (Supplementary Fig. 6).

We adapted a method of calculating division rates in bacterial cultures 12 to utilize all EMG parameters fit to the observed IMT distribution (Supplementary Notes 1,2). This method accounts for the dispersion of individual IMT, especially the slowly dividing cells in rightward skewed tails. In addition, this calculation of the division rate takes into account the age structure of an asynchronously dividing cell population under the assumption of exponential growth.

For quiescence rates, a crucial question is whether cells with lifespans demarcated by an initial mitotic event and the EoE are quiescent or whether they would have divided if the experiment had continued (Fig. 3a). We estimated the probability that a cell is quiescent by implementing a Likelihood of Quiescence Model based on a statistical survival formula 13 (Methods and Supplementary Notes 1,2). The older the undivided cell relative to the distribution, the lower the likelihood that it would have divided after the EoE, and the higher the likelihood that it is quiescent. The rate of entry into quiescence is then calculated using the fraction of quiescent cells in the population and is relative to the calculated rate of division. Importantly, without properly accounting for the slowly dividing cells in the population with a well-fit model (such as an EMG), the rate of entry into quiescence could be significantly overestimated.

We experimentally derived the three Quiescence-Growth model parameters from single cell tracking data of CA1d cells (Fig. 3c) treated with erlotinib (1 and 8 μM). Compared to control (DMSO), a large number of cells reached the EoE without dividing and were estimated to be quiescent by the Likelihood of Quiescence model (Table 1). The IMT distribution of cells treated with 8 μM erlotinib was flattened and elongated rightward (Fig. 3c). Rates calculated from the single-cell tracking data, EMG parameters and estimated quiescence fraction confirmed a decreased rate of division, a slight increase in death rate and a 10-fold increase in the rate of entry into quiescence at either erlotinib concentration. These experimentally-measured rates were in agreement with the rates estimated from fitting the Quiescence-Growth model to the cell count data (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1), indicating that the Quiescence-Growth model provides an accurate description of cell proliferation and validating its prediction that the nonlinear proliferation response to erlotinib (Fig. 2a) is explained by alteration of the rate of entry into quiescence (Fig. 3c). We observed that very few cells die during the experiment and cells considered quiescent did not exhibit preapoptotic nuclear condensation (not shown).

Table 1.

Quiescence-Growth Model parameters obtained from single-cell tracking data. The following parameter values were calculated from the data shown in Figure 3c: Fraction of live cells reaching the end of experiment, fEoE; fraction of quiescent cells, fQ; division rate, d; doubling time of dividing cells alone, DTd; and rate of entry into quiescence, q. The death rate (a) was obtained directly from analyzed image stacks

| DMSO | 1μM | 8μM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| fEoE | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.47 |

| fQ | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.41 |

| d | 0.0379 | 0.035 | 0.0241 |

| DTd | 18.3 h | 19.8 h | 28.8 h |

| q | 0.0015 | 0.0123 | 0.0167 |

| a | 0.0012 | 0.0013 | 0.0018 |

Fractional Proliferation graphs

We then used the parameters obtained from single-cell tracking data (Supplementary Video 2) in the Quiescence-Growth model to produce graphs of the total population deconvolved into fractions of dividing and quiescent cells (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Software 2). At ~24 h the fractions of cells in the two compartments are equal (Fig. 3d); in contrast, at 80 h the quiescent fraction is 82% and the dividing fraction is 18%.

Drug response of oncogene-addicted cells

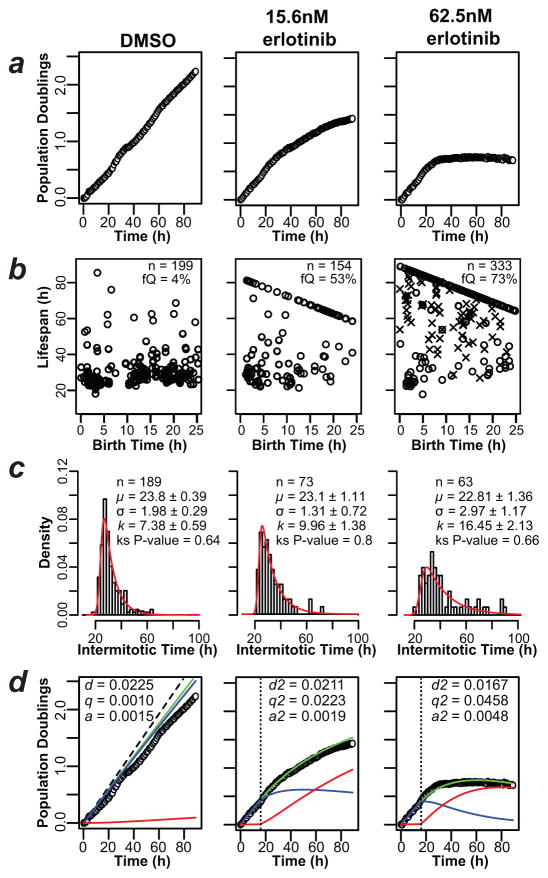

We applied this approach to investigate the dynamic response of PC9 cells to erlotinib (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1c). PC9 cells harbor activating mutations of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), are “oncogene-addicted,” and hypersensitive (GI50 <20 nM) to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI). These cells are representative of EGFR-mutated tumor cells in lung cancer patients that respond favorably to treatment with erlotinib (or other EGFR-specific TKI). The prevalent view is that PC9 cells have a strong apoptotic response to EGFR TKI 14,15 but, to our knowledge, the relative contributions of cell death versus quiescence in the PC9 response to erlotinib remain uncharacterized.

Figure 4. Application of Fractional Proliferation to a model of oncogene-addicted tumor cells.

(a) The plots show PC9 cell counts obtained by automated quantification of cell nuclei from time-lapse images of cultures treated as indicated. Data were normalized and plotted (open circles) on a log2 scale (Population Doublings). (b) Lifespan plots of tracked PC9 cells treated as indicated; observed birth time is on the x-axis and observed lifespan on the y-axis. Only cells born within the first 25 h of the experiment are shown. fQ, quiescent fraction; n = number of lifespans examined. (c) IMT distributions of PC9 cells treated as indicated. The EMG model was fit with the parameters shown within each graph. The P-value of the Kolmogorov-Smirnoff (ks) test indicates that the EMG model cannot be excluded as an explanation of the data (P>0.05). (d) Fractional Proliferation graphs of erlotinib-treated PC9 cells, as in 3d. The dashed line indicates calculated proliferation without the contribution of death and quiescence (based on DTd; see Fig. 3c). Parameter values fitting these data are indicated in the boxes and were applied after a delay (vertical dotted line) to account for lag time in drug action.

From cell count data derived from image stacks, PC9 cells exhibit exponential proliferation with a rate = 0.0183 (doubling time = 38 h) in medium containing vehicle (DMSO); however, single-cell tracking data show that this value underestimates the rate of division and does not consider the contribution of quiescence and death (Fig. 4d). Proliferation decreases in a nonlinear fashion upon erlotinib treatment (Fig. 4a) and cells accumulate at the EoE (Fig. 3a and 4b). From single-cell tracking data, 53% and 73% of cells with initial mitotic events within the first 25 h entered quiescence in response to 15.6 nM and 62.5 nM erlotinib, respectively, compared to 4% in the control cells. The IMT distributions showed a rightward skew in response to erlotinib characterized by an increased k parameter value, while all other parameter values remain essentially unchanged (Fig. 4c). We calculated the rates of division, death and entry into quiescence from the single-cell tracking data and produced Fractional Proliferation graphs (Fig. 4d). As for CA1d cells, using these rates in the Quiescence-Growth model correctly predicted the experimentally determined cell counts (Fig. 4d). The rate of cell death increased from 0.0015 in DMSO to 0.0048 in 62.5 nM erlotinib, but this cannot by itself explain the decreased proliferation seen after 30 h. The q parameter increased >40-fold from DMSO to 62.5 nM erlotinib-treated cells (Fig. 4d). These results indicate that in “oncogene-addicted” PC9 cells, the antiproliferative response to erlotinib is primarily due to increased entry into a non-dividing or quiescent state, and not to apoptosis as commonly assumed.

We verified that erlotinib treatment increased the fraction of quiescent PC9 cells by flow cytometry on Ki-67 (Supplementary Fig. 7) and p27-immunostained cells (not shown). We further confirmed these observations in another oncogene-addicted model cell line (A375, representing B-Raf V600E-mutated melanoma) (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs. 7,8). The non-dividing quiescent state we observe is not equivalent to a preapoptotic state; after 96 h in 1 μM erlotinib, a drug washout experiment showed that proliferation resumed to pretreatment levels (Supplementary Video 1 and Supplementary Fig. 9). Also, a large fraction of cells remained viable (Ki-67-positive) after more than 90 h of erlotinib treatment (Supplementary Fig. 7). Determining the eventual fate of these cells (division, death or extended quiescence) would require longer duration studies.

Application to primary cells

We assessed the performance of our approach on primary cells using a baculovirus-based transduction of a genetically-encoded fluorescent nuclear probe that is easy to use and commercially available (CellLight® Nucleus, Invitrogen). Labeled nuclei were detectable within 12 h, persisted for 5–6 days, and were amenable to automated counting and manual tracking. As an example, the proliferation of primary human squamous cell carcinoma cells is shown in Supplementary Figure 10 and Supplementary Video 3. It is worth noting that an EMG distribution also describes the distribution of IMT in primary cultured cells. Additional experimentation will be required to determine whether this distribution is applicable to all cell types.

DISCUSSION

The Fractional Proliferation method provides quantitative insight into cell proliferation in response to perturbations and permits deconvolution of the relative contribution of multiple cell fates to cell population dynamics. Using this approach, it is possible to capture the behavior of minor subpopulations of cells (e.g. stem or progenitor cells, clonal variants, drug resistant phenotypes) within perturbed populations. The importance of these subpopulations is increasingly appreciated, and methods to study them should be broadly applicable.

The integrated mathematical models we developed describe the emergence of population behavior from experimental data measuring single cell fates. We note that these models are not definitive; for example, they will need to be adjusted to more accurately accommodate age structure in asynchronously dividing populations; to apply them to stem cells, a rate of entry into one or more differentiated state would have to be included. However, image data sets such as those described here can be analyzed by future models. Furthermore, the approach could be enhanced by the incorporation of other read-outs, such as immunofluorescence on molecular markers or live cell reporters of molecular activity.

Time-lapse video microscopy has been used for decades, but its high-throughput implementation has only recently been enabled by technological advances in automated microscopy instrumentation coupled to computation. Methods to automate the extraction of mitotic phases and duration from time-lapse movies were recently developed 16–18. These approaches mainly focus on extracting image features that correlate with mitotic events.

The labeling approach we employed involves the expression of a fluorescent nuclear protein (H2BmRFP) introduced by recombinant viral particles. Although other labeling techniques are feasible, and even phase contrast imaging can provide data amenable to this approach, the use of H2BmRFP overcomes limitations due to photobleaching, toxicity, low signal-to-noise ratio in images, and fluctuating subcellular localization. In our hands, nuclear dyes (e.g. Hoechst 33342) demonstrate significant toxicity and cytoplasmic and membrane dyes (e.g. carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester and carbocyanine-based dyes) are prone to photobleaching, tend to aggregate in vesicles and pose challenges to identification of individual cells. The development of nontoxic fluorescent nuclear dyes would enable rapid cell labeling without genetic manipulation.

Observation of cells for several days permits study of the cell response to perturbations as they approach population steady state, which usually happens over many days of treatment. Our discovery that a major component of the PC9 response to TKI erlotinib is entry into a quiescent state challenges current views that the major response to erlotinib in oncogene-addicted cells is cell death 15, but is consistent with previous reports that erlotinib and other EGFR TKI induce cell cycle arrest in G1 in many cancer cell lines 19–21.

Erlotinib is of special interest because it is currently used clinically as adjuvant or first-line therapy in subsets of lung cancer patients with sensitizing EGFR mutationsfor reviews on the subject see references 22,23. Questions remain as to the basis for erlotinib hypersensitivity (“oncogene addiction”) in EGFR-mutated cancer cells, and the inevitable rise of resistance 24. As we have demonstrated, application of the Fractional Proliferation method should help answer these questions.

Describing IMT distributions with an EMG model provides value beyond calculating the rates of division and quiescence in the Quiescence-Growth model. The EMG model is mathematically separable into two components, Exponential and Gaussian. Intriguingly, erlotinib primarily affects the exponential (k) while CHX primarily affects the mean of the Gaussian (μ) (Supplementary Fig. 6). The possibility that these separable components reflect distinct biochemical mechanisms is currently under investigation. The EMG can be interpreted biologically as a combination of a Gaussian process (several random variables that are additive such as protein accumulation) and an exponential process (e.g. a checkpoint process such as the G1/S transition with a chance of passing at each check). Other descriptive distributions offer no simple interpretation biologically 25. The EMG may be more common in time-dependent cellular processes due to the mathematical properties of the chemical master equation which can have an exponential distribution of halting times after a well mixing time has passed 26,27.

It has long been known that antiproliferative responses are not limited to a single fate but the lack of methods to deconvolve behaviors has forced assumptions of linearity. The Fractional Proliferation method provides a means to accommodate nonlinear antiproliferative responses and to separate the underlying cellular fates that shape the population-level response.

METHODS

Software

We provide: i) an interactive Mathematica CDF Player file to explore the effects of altering Quiescence-Growth model parameter values on cell proliferation plots (Supplementary Software 1); ii) an ImageJ28,29 macro for automated cell counting (enumeration of nuclei) (Supplementary Note 2); and iii) fracprolif, an extension of the freely available statistical software package R30 (http://www.R-project.org) that incorporates all of the code (Supplementary Software 2) used to analyze single-cell tracking and cell count proliferation data and generate Fractional Proliferation Graphs (described in Supplementary Note 2).

Cell culture and labeling

The following cell lines were used: MCF10A, MCF10A-CA1d (abbreviated as CA1d), SQ20B, and PC9. MCF10A and CA1d cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% equine serum, 5% fetal bovine serum, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 10 μg/ml insulin, 500 ng/ml hydrocortisone, and 100 ng/ml cholera toxin. SQ20B cells were cultured in DMEM containing 20% fetal bovine serum and 400 ng/ml hydrocortisone, and PC9 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Primary human tumor-derived cells were obtained from a patient with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and grown continuously in culture in keratinocyte (serum-free) growth medium (Invitrogen). Cell lines were engineered to express the histone H2B/monomeric red fluorescent protein (H2B-mRFP) fusion protein using lentivirus-mediated transduction as previously described 31. Brightly fluorescent single-cell clones were expanded and compared to parental populations using traditional proliferation measurements to ensure they were representative of the initial population. Primary cells were induced to express H2B-mRFP using recombinant baculoviral particles (CellLight® Nucleus, Invitrogen) at 20 particles per cell, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Imaging with extended temporally-resolved automated microscopy (ETRAM)

Imaging was performed on 96-well plates (BD cat# 353219) using a BD Pathway 855 with a 20X (0.75 NA) objective in a CO2- and temperature-controlled environment. Images were acquired every 6–30 min using BD Attovision 1.6.2 software with the instrument in confocal mode (spinning disk). Nine adjacent images were captured at 0.4 s exposure and 2X2 binning to comprise a single 3X3 montage (approximately 800 μm2) from each of approximately 40–60 wells per experiment, and images were acquired for at least 72 h. Example montaged images are shown in Supplementary Figure 1a. Assays minimally included duplicate or triplicate wells and complete experiments were performed at least twice. Cells were seeded at 2,500–5,000 cells per well and allowed to grow overnight yielding approximately 200–600 cells at the onset of imaging. Cells were imaged until confluence (approximately 3,000 cells in an image) was achieved in control wells. Erlotinib concentration-response curves on PC9 cells were performed more than five times.

Enumerating nuclei

Nuclei were counted from ETRAM-generated image stacks sampled at approximately 1 h intervals. Images were imported into the freely available ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) program and subjected to a macro optimized for images obtained from a BD Pathway 855. The macro: i) corrects for uneven illumination using a 50 pixel diameter rolling ball filter; ii) converts images to binary using a predefined threshold intensity value; iii) segments individual nuclei using a watershed algorithm; and iv) quantifies objects within specified range of areas and circularity. Example images and resultant cell population plots are shown in Supplementary Figure 1a, b. The ImageJ macro is provided in Supplementary Note 2, and an example image sequence showing nuclei enumeration by ImageJ is shown in Supplementary Figure 4.

Quantifying rates of cell death

An example of a region of a manually tracked ETRAM-generated image stack is shown in Supplementary Video 1. Cell death was identified by nuclear shrinkage to less than 50% of average nuclear area and subsequent nuclear dispersion or detachment (no longer detectable) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Rates of cell death were determined by dividing the number of events (cell deaths) detected across all frames by the total cell observation time (number of cell nuclei in each frame multiplied by the time interval between frames); this rate does not require individual cells to be tracked over complete lifespans.

Quantifying intermitotic times and rate of division

For most cell lines, ETRAM was performed at 12 min intervals to minimize light exposure and phototoxicity, and for highly motile cells at 6 min intervals to eliminate bias against faster moving cells.

Intermitotic times were measured by manually tracking individual nuclei through the series of ETRAM-generated images, identifying mitotic events (metaphase chromosomes), and determining the number of frames between mitotic events for each individual cell lifespan. Lifespans of cell nuclei that divided once during the experiment but reached the EoE were also determined. 100 nuclei were tracked for each condition, and more if too many cells reached the EoE without having divided, since a minimum of 50 individual IMT represented a distribution.

Model of proliferation kinetics (Quiescence-Growth Model)

The Quiescence-Growth model is formulated as a pair of coupled ordinary differential equations where x represents the dividing cell number, y the quiescent cell number and x + y equals the total cell population. The rates are described by the three parameters: d for division or birth rate, q for quiescence rate and a for death rate.

which has an analytical solution of the following form:

On a log scale the model is nonlinear due to the quiescence compartment (y). Also of note, when d=q the following solution applies.

When d is greater than or equal to q + a, the following asymptotic behavior is observed:

This shows that the model approaches exponential growth as long as the division rate exceeds the sum of the rates of death and entry into quiescence and mathematically proves that the observation of exponential proliferation of a population does not exclude the possibility of quiescence and death. Thus, only in the absence of any death or quiescence does the rate of cell division reflect the rate of proliferation of the population. On the other hand, note that the population could grow exponentially even if nearly half of the cells enter quiescence or die. Furthermore, entry into the quiescent compartment (with rate q) provides the only mechanism by which nonlinear proliferation curves can be achieved. An alternative of the model has been produced in which a different rate of death from each compartment is provided (Supplementary Note 1). However, since measuring these different rates from the single-cell data with sufficient statistical power is not yet feasible, the alternative model reverts to the form used in this method.

Statistical methods

To determine whether a model could describe the observed data with sufficient statistical accuracy, a one-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test was performed with a two-sided test being the null hypothesis. This test determines the probability that the data and the model are sampled from the same distribution, and a P value of less than 0.05 was assumed to be statistically significant evidence that the data and the model represent different distributions.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality. The likelihood of one of two specific models (e.g. a linear model compared to the Quiescence-Growth model) correctly fitting the data was determined using Akaike’s Information Criteria <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akaike_information_criterion>.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank J. Hao and A. Udyavar for technical assistance, E. Pham and R. Feroze for assistance in manual image analysis, G. Ostheimer for assistance with flow cytometry and A. Weaver, G. Webb, B. Rexer, K. Dahlman, W. Yarbrough and L. Estrada for reviewing the manuscript and providing stimulating discussions. We acknowledge the generous gift of primary squamous cell carcinoma and SQ20B cells from W. Yarbrough and PC9 cells from W. Pao (both at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine). We also acknowledge A. Miyawaki (RIKEN Brain Science Institute) for the mAG-geminin plasmid and Gideon Bollag (Plexxikon) for the generous gift of PLX-4720. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Integrative Cancer Biology Program (5U54 CA113007-07). Flow cytometry experiments were performed in the Vanderbilt Medical Center Flow Cytometry Shared Resource, which is supported by the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (P30 CA68485) and the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center (DK058404). In addition, the project described was partially supported by the National Center for Research Resources (UL1 RR024975-01) and is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (2 UL1 TR000445-06).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.R.T. conceived of the approach, D.R.T. and P.L.F. cultured, treated and imaged cells, D.R.T. analyzed images; S.P.G. and D.R.T. developed the mathematical models, D.R.T. and S.P.G. fit model parameters to data; D.R.T. and V.Q. co-wrote the paper.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Hughes M, et al. Early Drug Discovery and Development Guidelines: For Academic Researchers, Collaborators, and Start-up Companies. In: Sittampalam GS, et al., editors. Assay Guidance Manual. Bethesda (MD): 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terry NH, White RA. Flow cytometry after bromodeoxyuridine labeling to measure S and G2+M phase durations plus doubling times in vitro and in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:859–869. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Genderen H, et al. In vitro measurement of cell death with the annexin A5 affinity assay. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkins ED, et al. Measuring lymphocyte proliferation, survival and differentiation using CFSE time-series data. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2057–2067. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakaue-Sawano A, et al. Visualizing spatiotemporal dynamics of multicellular cell-cycle progression. Cell. 2008;132:487–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.d’Onofrio A, Fasano A, Monechi B. A generalization of Gompertz law compatible with the Gyllenberg-Webb theory for tumour growth. Math Biosci. 2011;230:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gyllenberg M, Webb GF. Age-size structure in populations with quiescence. Math Biosci. 1987;86:67–95. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florian JA, Jr, Eiseman JL, Parker RS. Accounting for quiescent cells in tumour growth and cancer treatment. Syst Biol (Stevenage) 2005;152:185–192. doi: 10.1049/ip-syb:20050041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozusko F, Bajzer Z. Combining Gompertzian growth and cell population dynamics. Math Biosci. 2003;185:153–167. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(03)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner ME, Jr, Bradley EL, Kirk KA, Pruitt KM. A theory of growth. Math Biosci. 1976;29:367–373. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grushka E. Characterization of exponentially modified Gaussian peaks in chromatography. Anal Chem. 1972;44:1733–1738. doi: 10.1021/ac60319a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell EO. Growth rate and generation time of bacteria, with special reference to continuous culture. J Gen Microbiol. 1956;15:492–511. doi: 10.1099/00221287-15-3-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLachlan GJ, Peel D. Finite Mixture Models. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong Y, et al. Induction of BIM is essential for apoptosis triggered by EGFR kinase inhibitors in mutant EGFR-dependent lung adenocarcinomas. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma SV, et al. A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell. 2010;141:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harder N, et al. Automatic analysis of dividing cells in live cell movies to detect mitotic delays and correlate phenotypes in time. Genome Res. 2009;19:2113–2124. doi: 10.1101/gr.092494.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Held M, et al. CellCognition: time-resolved phenotype annotation in high-throughput live cell imaging. Nat Methods. 2010;7:747–754. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sigoillot FD, et al. A time-series method for automated measurement of changes in mitotic and interphase duration from time-lapse movies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bos M, et al. PD153035, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, prevents epidermal growth factor receptor activation and inhibits growth of cancer cells in a receptor number-dependent manner. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:2099–2106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. A novel approach in the treatment of cancer: targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2958–2970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ling YH, et al. Erlotinib, an effective epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, induces p27KIP1 up-regulation and nuclear translocation in association with cell growth inhibition and G1/S phase arrest in human non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:248–258. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grunwald V, Hidalgo M. Developing inhibitors of the epidermal growth factor receptor for cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:851–867. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.12.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pao W, Chmielecki J. Rational, biologically based treatment of EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:760–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riely GJ, et al. Clinical course of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 and exon 21 mutations treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:839–844. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golubev A. Exponentially modified Gaussian (EMG) relevance to distributions related to cell proliferation and differentiation. J Theor Biol. 2010;262:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sbano L, Kirkilionis M. Multiscale analysis of reaction networks. Theory Biosci. 2008;127:107–123. doi: 10.1007/s12064-008-0036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chichagov VV. Asymptotic behavior of the first arrival time in Markovian random walks. J Math Sci. 1987:2944–2948. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abramoff MD, Magalhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasband WS. ImageJ. U. S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland: 1997–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quaranta V, et al. Trait variability of cancer cells quantified by high-content automated microscopy of single cells. Methods Enzymol. 2009;467:23–57. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)67002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.