Abstract

Background

One in every 10 000 to 40 000 passengers on commercial aircraft will have a medical incident while on board. Many physicians are unaware of the special features of the cabin atmosphere, the medical equipment available on airplanes, and the resulting opportunities for medical intervention.

Methods

A selective literature search was performed and supplemented with international recommendations and guidelines and with data from the Lufthansa registry.

Results

Data on in-flight medical emergencies have been collected in various ways, with varying results; it is generally agreed, however, that the more common incidents include gastrointestinal conditions (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting), circulatory collapse, hypertension, stroke, and headache (including migraine). Data from the Lufthansa registry for the years 2010 and 2011 reveal the rarity of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (mean: 8 cases per year), death (12 cases per year), childbirth (1 case per year), and psychiatric incidents (81 cases per year). If one assumes that one medical incident arises for every 10 000 passengers, and that there are 400 passengers on board each flight, then one can calculate that the probability of experiencing at least one medical incident reaches 95% after 24 intercontinental flights.

Conclusion

An in-flight medical emergency is an exceptional event for the physician and all other persons involved. Physician passengers can act more effectively if they are aware of the framework conditions, the available medical equipment, and the commonly encountered medical conditions.

Over the past few decades, commercial aviation has become one of the safest modes of transportation. Commercial airline flights took 2.5 million passengers to their destinations in 2011. Medical incidents occasionally occur during such flights because of the large number of passengers, the uninterrupted flight times of as long as 16 hours, and the biomedical consequences of the cabin atmosphere. For multiple reasons, the care of persons suffering from medical emergencies on board presents a special challenge to their fellow passengers who happen to be physicians (1).

Learning objectives

The aim of this review is to acquaint readers with

the properties of the cabin atmosphere and its biomedical consequences,

the physiological compensatory mechanisms,

the medicolegal framework,

and the opportunities for, and limitations of, medical care on board commercial aircraft.

Medical incidents.

Medical incidents occasionally occur on commercial airplanes because of the large number of passengers, the long flight times, and the biomedical consequences of the cabin atmosphere.

The cabin atmosphere in a commercial airplane

Modern commercial aircraft fly in the troposphere and stratosphere at cruising altitudes of 32 000 to 45 000 feet (about 10 000 to 14 000 m), where the outside temperature lies between -52 and -60 °C and the air pressure is about 200–300 hPa; thus, the cabin must be isolated and pressurized (2). The cabin pressure in civil aircraft is at least the pressure at an altitude of 8000 feet (ca. 2438 m), i.e., no less than 753 hPa, where the air pressure of the standard atmosphere at sea level is 1013 hPa (3). Because of this relatively low pressure, and because the fractional oxygen content of the air in the cabin is the same as that at sea level, the partial pressure of oxygen in cabin air at cruising altitude is 25% to 30% lower than normal—about 110 mm Hg, compared to about 160 mm Hg at sea level (by Dalton’s law of gases). Part of the cabin air (no more than 40% to 50%) is recirculated and cleaned with high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, while the remainder is derived from outside air (“bleed air”). Minimum quantities of fresh air and minimum filter-pore diameters are specified in the approval requirements for aircraft models. The humidity on board ranges from 6% to 18% depending on the compartment, while the temperature ranges from 19° to 23°C.

Physiological changes.

Reduced cabin pressure leads to expansion of closed gas- and air-containing compartments in the human body, such as the paranasal sinuses, frontal sinus, and middle ear.

Physiological changes: adaptation to the cabin atmosphere

In accordance with the gas law of Boyle and Mariotte, reduced cabin pressure leads to expansion of closed gas- and air-containing compartments in the human body, such as the paranasal sinuses, frontal sinus, and middle ear, as well as of non-physiological collections of gas and air that may be found after abdominal, intracranial, or ophthalmic surgery and in pneumothorax. The low partial pressure of oxygen causes mild hypoxia, with a fall of the oxygen saturation of the blood to the range of 92% to 95%, and compensatory hyperventilation and tachycardia (3, 4). Hydrostatic edema in the dependent limbs is common because of immobilization combined with the low ambient air pressure. The low humidity of cabin air, combined with hyperventilation, can lead to dehydration if the passenger does not consume adequate amounts of fluid during flight.

Medical incidents on board: facts and figures

Registries of data from multiple airlines are very rare; airlines usually do not publish of such figures, and the figures that reach the public are therefore often not validated in any way. One medical incident is estimated to occur for every 10 000 to 40 000 passengers on intercontinental flights (5). Assuming the lower figure and assuming that there are 400 passengers on board each flight, one can calculate that with 95% probability one medical incident will be experienced within 24 intercontinental flights. Such incidents can range in severity from simple discomfort, without any threat to health or life, all the way to childbirth, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and death. The great majority of medical incidents on board are not so dramatic (6, 7).

Studies of in-flight medical emergencies often fail to take account of the highly variable distances traveled, flight times, and routes. Nor has there been, to date, any uniform standard for the characterization and categorization of clinical manifestations, or for the assignment of diagnoses. Thus, the variable modes of data collection themselves account for marked variation in the reported numbers and frequencies of medical incidents. In any case, it is generally agreed that among the five most common types of conditions encountered are gastrointestinal diseases, cardiovascular diseases, neurological diseases, and primary pulmonary events (1, 7, 8).

Partial pressure of oxygen.

The low partial pressure of oxygen causes mild hypoxia, with a fall of the oxygen saturation of the blood to the range of 92% to 95%, and compensatory hyperventilation and tachycardia.

In-flight emergencies: the Lufthansa registry

The Lufthansa registry, which contains data from the year 2000 onward, documents a disproportionate increase in the frequency of in-flight medical incidents and emergencies in relation to passenger volume and to the number of person-miles flown over the period studied. In 2011, the airline registered one medical incident per 30 000 passengers; 70% of all incidents and emergencies occurred on intercontinental flights, of which the airline has about 140 per day, out of a total of roughly 1700 Lufthansa flights. In more than 80% of cases, a physician or other professional helper (e.g., nurse, emergency medical technician) gave help on board. Common clinical problems included dizziness, collapse, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, paralysis, and colic (Figure 1). A further classification by suspected diagnoses, symptom complexes, and clinical conditions was made possible by post-hoc characterization of symptoms, physical findings, and relevant information from emergency protocols and flight documentation (Table).

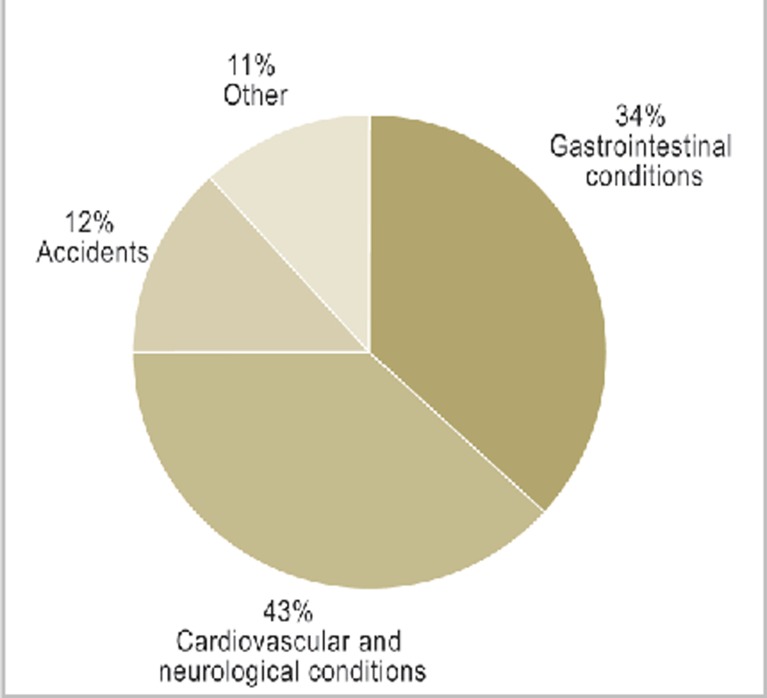

Figure 1.

Symptom and diagnosis classification for more than 20 000 documented medical events on Lufthansa flights, 2000–2011. The symptoms are classified by suspected diagnosis. Cardiovascular conditions are grouped together with neurological conditions, including stroke, for the purpose of this diagram. Accidents usually involved luggage falling out of the overhead storage rack or burns and scalds from hot drinks. The category “Other” includes conditions of the ear, nose, and throat, colic, suspected infectious conditions, and psychiatric disturbances

Table. Post hoc characterization of conditions*1.

| Gastrointestinalconditions | Cardiovascularconditions | Neurological and psychiatric conditions | Accidents | Other |

| Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting | Circulatory collapse | Stroke, transient ischemic attack | Blunt trauma | Respiratory symptoms, asthma |

| Diffuse abdominal pain | High blood pressure | Headache (including migraine) | Burns, scalds | Fever |

| Colic (renal, biliary) | Chest symptoms | Dizziness, epilepsy, absence attacks | Cuts, bleeding | Hyper- or hypoglycemia |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | Dehydration | Altered mentation, anxiety | Fractures | Intoxication (alcohol, medications, illicit drugs) |

| Pregnancy |

*1Clinical conditions and their descriptions in all documented medical incidents on Lufthansa flights in the years 2000–2011, as in Figure 1. The categories “Cardiovascular conditions” and “Neurological and psychiatric conditions” are shown separately here.

Shown in order of most to least frequent suspected diagnosis, with considerable overlap due to multiple types of condition per incident

Distribution of incidents.

70% of all incidents and emergencies occur on intercontinental flights.

85% of the emergency protocols filled out on board in 2010 and 2011 concerned medical incidents on intercontinental flights. More than 35% involved patients over age 55, with a peak between age 56 and age 65. The most common medical activity on board was blood-pressure measurement, followed by the administration of drugs and of oxygen (Figure 2). An automatic defibrillator device was used in about 6% of the incidents (a total of 136 times in 2010–2011), but almost always only to record an ECG, rather than to defibrillate the patient in the setting of a cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The latter occurred only twice over the entire period 2010–2011. In-flight cardiopulmonary resuscitation and death were both rare events, occurring in an average of one per 5 to 10 million passengers. In general, the only patients who survive after in-flight cardiopulmonary resuscitation are those who are successfully defibrillated. 80 persons survived after the use of an automated external defibrillator (AED) on American Airlines flights from 1997 to 2010 (9); this happened once on Lufthansa flights in 2010–2011. In the same two years, 25 passengers died on board out of a total of 124.1 million passengers.

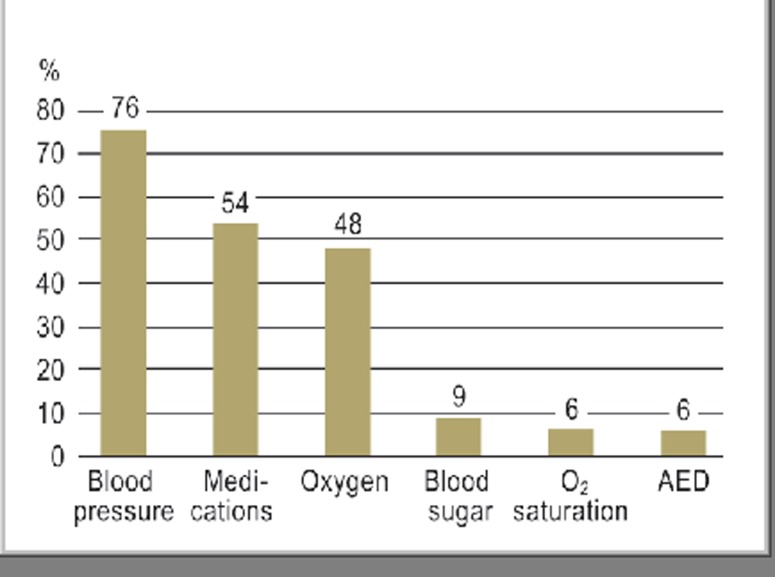

Figure 2.

Interventions carried out during medical incidents on Lufthansa flights in 2010 and 2011 (based on 2264 filled-out emergency protocols); more than one intervention was possible per incident. (Blood-pressure measurement, administration of drugs, administration of oxygen, blood sugar measurement, monitoring of oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter, use of an automatic external defibrillator [AED]). Only about 50% of the physicians who helped in medical incidents on board filled out an emergency protocol

The medical incidents were distributed proportionally to the flight volumes to the individual regions served, i.e., their frequency was no different on flights to Asia, North America, or South America. Nor was there any difference in frequency depending on the type of airplane (Airbus vs. Boeing).

CPR and death.

In-flight cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and death are rare events, occurring an average of once each per 5 to 10 million passengers.

Travel-associated thromboembolic complications

The Lufthansa data contain only rare cases of venous thrombosis in the lower limbs occurring on long-distance flights. In a current guideline, the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is estimated at one case for every 4656 passengers on flights lasting longer than 4 hours, and at 0.5% among passengers at low or intermediate risk who fly for longer than 8 hours. Symptomatic, severe pulmonary embolism is rare: its frequency is estimated in recent studies at about five per million passengers on flights lasting longer than 12 hours (10, 11). Pre-existing risk factors significantly increase the probability of VTE, while exercise during the flight markedly lowers it. A general recommendation for anti-thrombotic stockings or anticoagulants appears unjustified (10), because VTE has not been observed in any passengers without risk factors, even when they flew for longer than 8 hours (12). For persons at greater risk who will be taking a long flight, individualized prophylaxis should be considered. Anti-platelet drugs are not suitable for this purpose (10, 11).

The WRIGHT project (i.e., the World Health Organization’s Research into Global Hazards of Travel), currently in progress, places a major emphasis on risk assessment as a means of lowering the incidence of travel-associated VTE (13).

Among the more than 20 000 in-flight medical incidents documented in the Lufthansa registry (2000–2011), thrombosis was suspected in 202 cases (1% of the total). It was not possible to check on the correctness of these diagnoses or to include data on thromboembolic events occurring after landing, as the law forbids the active follow-up of airline passengers.

Thrombosis prevention.

A general recommendation for anti-thrombotic stockings or anticoagulants appears unjustified, because venous thromboembolism has not been observed in any passengers without risk factors, even when they flew for longer than 8 hours.

Legally required medical equipment on commercial aircraft

There are legal requirements for the medical equipment that must be carried on board any commercial airplane. That which the law in each country requires would be considered a minimal standard from the point of view of a physician (or a specialist in emergency medicine). In each country or supranational jurisdiction, this standard is determined by the responsible aviation authority (14): the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the United States (Box 1), and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) in collaboration with the Joint Aviation Authorities (JAA) in Europe (Box 2).

Box 1. Contents of the FAA emergency medical kits*1.

-

Automatic external defibrillator (AED)

(model approved in the USA, maintenance certification, approved battery)

Sphygmomanometer

Stethoscope

Orotracheal tubes in three sizes (child, small adult, large adult)

4 syringes, including 1 × 5 mL, 2 × 10 mL and syringes corresponding to the ampoules carried on board

6 needles (2 × 18 G, 2 × 20 G, 2 × 22 G) or more as needed

1 intravenous infusion set with tubing, 2 Y-connectors, alcohol wipes, adhesive tape, scissors, and tourniquet

500 mL of normal saline solution

Bag-valve-mask resuscitator with a reservoir and three masks (child, small adult, large adult)

Emergency airway, three sizes (child, small adult, large adult)

1 pair of disposable gloves

List of contents and drug information

Drugs

4 tablets of an antihistamine drug

2 ampoules of an antihistamine drug (50 mg) or the equivalent

4 tablets of aspirin 325 mg

2 ampoules of atrophine 5 mL, 0,5 mg, or the equivalent

1 bronchodilator (for inhalation) or the equivalent

2 ampoules of lidocaine 5 mL, 20 mg/mL

4 tablets of a non-opioid analgesic

1 ampoule of 50% glucose, 50 mL or the equivalent

2 ampoules of epinephrine 1 : 1000 or the equivalent

2 ampoules of epinephrine 1 : 10 000 or the equivalent

2 ampoules of diphenhydramine or the equivalent

10 tablets of trinitroglycerin 0.4 mg

*1Medical kit specifications of the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) according to Final Rule FAA-2000–7119, Sec. A121.1 Appendix A. April 2004. In force for all American and foreign airlines and all types of airplanes with one or more accompanying personnel

Box 2. Contents of the JAR emergency medical kit*1.

Sphygmomanometer

Syringes and needles

Orotracheal tubes in two sizes

Tourniquet

Disposable gloves

Urine catheter

List of contents (in English and at least one other language)

Drugs

Corticosteroids

An antiemetic

An antihistamine

A spasmolytic

Atropine

A bronchiodilator (for inhalation and injection)

Nitrates, trinitroglycerin

Digoxine

A diuretic

Epinephrine 1 : 1000

An analgesic

Glucose or glucagon

A sedative / an anticonvulsant

A uterotonic agent

No infusion set is required.

*1Contents of the JAR-OPS 1.755 emergency medical kit (September 2005). Minimal standard for aircraft with more than 30 passengers and a flight time of more than 60 minutes to the nearest airport with qualified medical support. The commander of the aircraft is responsible for ensuring that drugs are administered only by medical personnel (physicians, trained nurses, or emergency medical technicians)

European airlines that fly to the USA must meet the requirements of both the FAA and the JAA. Thus, in addition to the European requirements, their airplanes must also carry the following equipment:

an automatic external defibrillator,

an infusion system with normal saline solution, and

a bag-valve-mask resuscitator.

Medical equipment on board Lufthansa planes

Many airlines carry more medical equipment on board than required by law. Often, the equipment carried on board is determined on the basis of a comprehensive medical safety plan, incorporating considerations of quality and risk management. The medical equipment on board Lufthansa planes can serve as an example (Box 3, eTable ). Ever since the SARS pandemic of 2003 (15) and the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 (16), additional infection protection sets have been carried so as to minimize the already low risk of in-flight transmission of viral or bacterial infections (17, 18).

Box 3. Contents of the Lufthansa doctor’s kit.

Modular construction

with transparent module bags and multilingual labeling, list of contents, emergency protocol, multilingual release from liability, sharp disposal unit, ampoule set in the doctor’s kit (yellow bag, see Box 2).

-

Diagnostic module

Sphygmomanometer

Disposable gloves, unsterile

Pulse oximeter

Glucometer, including necessary accessories

Fever thermometer

Stethoscope

-

Infusion module

Alcohol wipes, surgical sponges

Leukofix, adhesive bandages

Disposable gloves, unsterile

Infusion materials, tourniquet

Indwelling venous catheters (18-, 20-, and 22-gauge)

Infusion solution, 500 mL

-

Bladder catheter module

Foley catheters (sizes Ch12 and Ch14), blocker syringe

Disposable gloves, sterile

Disinfectant solution, fenestrated drape, lubricant

Sterile drapes, surgical sponges, forceps

Urine bag, 1000 mL

-

Suction module

Manual suction pump

Suction catheters (sizes Ch18 and Ch22)

Disposable gloves, unsterile

-

Intubation module

Endotracheal tubes (sizes 3 to 7.5)

Stylet, lubricant

Disposable gloves, unsterile; blocker syringe

Laryngoscope with spatula (sizes 2 and 3)

Magill forceps

Pack of bandages, Leukofix

-

Ventilation module

Oxygen catheter, nasal prongs

Oxygen tube with connecting device

Resuscitator device with reservoir

Ventilation masks for children (sizes 0, 1, 2)

Ventilation mask for adults (size 5)

Guedel tubes (sizes 0, 2, 3, and 4)

Disposable gloves, unsterile

eTable. Ampoule-set module (yellow plastic bag) and medical kit in the Lufthansa doctor’s kit.

| Drug | Form | Number |

| Epinephrine hydrogen tartrate 1:1000 Jenapharm ampoule/1 mL | Ampoule | 10 |

| Biperidene lactate ampoule 5 mg/1 mL | Ampoule | 1 |

| Amiodarone HCl ampoule 150 mg/ 3 mL | Ampoule | 3 |

| Water ampoule 5 mL | Ampoule | 3 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid i.v. ampoule | Ampoule | 1 |

| Atropine sulfate ampoule 1mg/ mL | Ampoule | 4 |

| Metoprolol tartrate i.v. ampoule | Ampoule | 2 |

| Fenoterol hydrobromide N 100 dosed aerosol | Spray | 1 |

| Theophylline sodium glycinate ampoule 10 mL | Ampoule | 3 |

| Reproterol ampoule 0.09 mg/1 mL | Ampoule | 2 |

| Butylscopolamine bromide ampoule 20 mg/1 mL | Ampoule | 2 |

| Diazepam 10 mg/2 mL | Ampoule | 5 |

| Midazolam ampoule 15 mg/3 mL | Ampoule | 1 |

| Glucose 40% ampoule 10 mL | Ampoule | 5 |

| Urapidil 50 mg 2 ampoules/10 mL | Ampoule | 2 |

| Haloperidol ampoule 5 mg/1 mL | Ampoule | 2 |

| Heparin sodium 5000 | Ampoule | 1 |

| Sodium chloride solution 0.9 % 10 mL | Ampoule | 3 |

| Esketamine HCl ampoule 50 mg/2 mL | Ampoule | 1 |

| Furosemide ampoule 40 mg | Ampoule | 2 |

| Metoclopramide HCl ampoule 10 mg/2 mL | Ampoule | 2 |

| Metamizole ampoule 2,5 g/5 mL | Ampoule | 2 |

| Ranitidine hydrochloride solution for injection | Ampoule | 1 |

| Prednisolone 250 mg ampoule | Flask | 2 |

| Clemastine ampoule 2 mg/5 mL | Ampoule | 1 |

| Tramadol HCl ampoule 100 mg/2 mL | Ampoule | 1 |

| Other: Disposable canulae (sizes 1 and 12, 4 of each), disposable syringes (2 mL, 5 mL, and 10 mL, four of each), disposable scalpel, 4 umbilical clamps, alcohol wipes, cellulose swabs | ||

| Contents of the red plastic bag | ||

| Drug | Form | Number |

| Nitrendipine (phials) | Phial | 4 |

| Lidocaine HCl 20 g | Tube | 1 |

| Butylscopolamine bromide tablets | Coated tablet | 10 |

| Butylscopolamine bromide supp. | Suppository | 2 |

| Diazepam rectal tube 10 mg | Tube | 1 |

| Loperamide HCl coated tablets | Coated tablet | 6 |

| Nitroglycerine capsules | Capsule | 10 |

| Paracetamol 250 supp. | Suppository | 2 |

| Aluminum phosphate | Bag | 4 |

| Povidone eye drops | Phial | 2 |

| Prednisone supp. 100 mg | Suppository | 2 |

| Dimenhydrinate coated tablets | Coated tablet | 10 |

| Dimenhydrinate 150 supp. | Suppository | 5 |

All medical incidents that occur in flight, and the responses to them, are continually documented and analyzed. Important information and any changes that may be necessary are integrated into the training of flight personnel, and the medical equipment on board is updated as needed.

Crew training: instruction in first aid

Preparation for in-flight medical emergencies includes not only the provision of medical equipment on board all aircraft, but also annual training sessions for the cabin crew. Minimum requirements for crew instruction are set by law. These include practice in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and in the management of various medical problems, ranging from arterial hypertension and dehydration to childbirth on board (a rare event that occurs less than once per year [mean occurrence]). Aside from medical skills per se, instruction is given in group behavior strategies (“crew resource management”), cases are simulated, and communication among all involved persons (the patient, physicians on board, cockpit personnel, medical advisors on the ground) is practiced.

Medical equipment on board.

Many airlines carry more medical equipment on board than required by law. Often, the equipment carried on board is determined by a comprehensive medical safety plan, with considerations of quality and risk management.

Medical advice from the ground

Many airlines offer their crews, and any physicians who may be called on to help passengers with medical problems on board, the additional option of medical advice by satellite telephone. Physician specialists in aviation and emergency medicine are ready to advise in-flight helpers from the ground, assisting them both with diagnostic assessment and with treatment decisions, in consideration of the equipment and personnel that are present on board. These advisors can also help assess the medical infrastucture available on the ground if an emergency landing is contemplated.

The law on board commercial aircraft.

An airplane is not a law-free zone. During flight, “flag right” is in effect, i.e., the applicable laws are those of the country under whose jurisdiction the aircraft or airline operate.

Applicable laws on board commercial aircraft

Legal uncertainty and the putative risk of a malpractice suit are often cited by physicians as reasons for their own hesitancy to provide medical assistance on board an airplane, even in an emergency. Indeed, neither the Earth’s upper atmosphere nor the interior of an aircraft constitutes a law-free zone. During flight, “flag right” is in effect, i.e., the applicable laws are those of the country under whose jurisdiction the aircraft or airline operates: for example, the United States in the case of United Airlines, or the Federal Republic of Germany in the case of Lufthansa. The law in many countries explicitly requires physicians who are present at a medical emergency to provide assistance (the applicable German law is § 323c StGB; similar laws are in effect in France, Australia, and many Asian and Middle Eastern countries, among others). In contrast, British, Canadian, and American law do not require physicians to help in a medical incident on board, unless there is a pre-existing physician-patient relationship (19).

Medical advice from the ground.

Many airlines offer their crews, and any physicians who may be called on to help passengers with medical problems on board, the additional option of medical advice by satellite telephone.

In order to relieve assisting physicians on board of any medicolegal worries that could hinder them in the provision of aid, the cabin crew often issues a declaration of assumption of liability, according to which the physician is insured for any claims arising from his or her actions on board except in the case of deliberate harm or gross negligence. This insurance is a component of the insurance of the aircraft for personal injury claims; it covers medical interventions even by persons whose medical qualifications are not generally recognized in the country under whose jurisdiction the aircraft or airline operates. Such interventions are covered, however, only if the assisting person obtains no monetary or equivalent recompense for the medical intervention. Emergency assistance is accepted and insured, but the practice of medicine as an ordinary commercial activity is not.

If, for example, an airline employee calls out for medical assistance from a physician, this should not be construed as a professional referral. If a physician who provides assistance on board decides to request financial compensation for his or her services, this request should be made to the passenger who was assisted, rather than to the airline.

In the United States, the Aviation Medical Assistance Act (49 USC 44701), popularly known as the Good Samaritan Law, has been in effect since 1998: physicians providing emergency assistance on airplanes cannot be held liable except in case of “gross negligence or wilful misconduct” (20).

The legal situation.

The cabin crew often issues a declaration of assumption of liability, according to which the physician is insured for any claims arising from his or her actions on board except in the case of deliberate harm or gross negligence.

What physicians should do in a medical emergency on board

The conduct of a physician in an in-flight emergency does not differ in any major respect from emergency care on the ground. The following considerations, however, must be borne in mind:

on-board treatment is by its very nature carried out in an isolated setting,

the available expert knowledge and specialized equipment are highly limited, and

the setting is very different from the physician’s usual working environment (21, 22).

Most of the affected persons and their fellow passengers are aware of all these things. Thus, a calm and competent demeanor on the part of the helping physician can lighten the stressful emotional situation on board and contribute to the success of any medical interventions provided.

Financial claims.

If a physician who provides assistance on board decides to request financial compensation for his or her services, this request should be made to the passenger who was assisted, rather than to the airline.

The framework conditions on board an airplane, and the diverse nationalities of the passengers, create a number of challenges for the helping physician. History-taking is often difficult because of the lack of a common language (1). Physical examination, too, is limited in many ways because of the narrow space, suboptimal lighting, vibrations, and ambient noise: Inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation can only be performed with difficulty, if at all. Because of the noise, stethoscopic examination of the heart, lungs, or abdomen is usually impossible.

Before attempting to help the affected person, the physician helper should always first obtain that person’s consent, ideally with a crew member as a witness (6). If third parties interfere with the physician’s attempt to help a person who cannot give his or her own consent, German law gives the commander of the aircraft the authority to ensure that actions are taken in the interest of the affected person. According to §12 of the German Aviation Safety Law (Luftsicherheitsgesetz), the captain has the equivalent of a policeman’s power of enforcement.

The overall emotional situation.

A calm and competent demeanor on the part of the helping physician can lighten the stressful emotional situation on board and contribute to the success of any medical interventions provided.

Limitations to physical examination.

Physical examination is difficult because of the narrow space, suboptimal lighting, vibrations, and ambient noise. Inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation can only be performed with difficulty, if at all.

Communication with the crew is also essential while the physician is caring for the patient. If the affected passenger is suffering from an impairment of consciousness or any other condition that appears to be life-threatening, the crew must be informed of this so that he or she can be properly positioned in a place where further emergency measures can be carried out, if necessary. For example, respiratory support with a bag-valve-mask resuscitator or full cardiopulmonary resuscitation are possible only in the kitchen or toilet area with the patient lying on the ground; there is too little space available elsewhere on the plane.

The captain’s power of enforcement.

If third parties interfere with the physician’s attempt to help a person who cannot give his or her own consent, German law gives the commander of the aircraft the authority to ensure that actions are taken in the interest of the affected person.

Unscheduled landings

Depending on the (presumed) diagnosis, the severity of the passenger’s condition, the degree of medical expertise and support available on board, and the flight route, an unscheduled landing may be considered necessary. The captain discusses this option with the helping physician. In doubtful cases, the helping physician should now (at the very latest) take the opportunity to speak by satellite telephone with a physician on the ground who has special expertise in aviation medicine, because the important considerations for the decision to land include not just the technical feasibility of landing at a suitable airport, but also the nature of the medical infrastructure and further transport modalities that will be available there (if necessary). For example, a hemodynamically stable patient with the symptoms and signs of a stroke will benefit only from care in a center that can perform neuroimaging to distinguish cerebral hemorrhage from cerebral ischemia. In many parts of the world, such centers, even where they exist, may be accessible only by a long and difficult ground voyage from the airport, perhaps in an unsuitable vehicle (i.e., something other than a fully equipped ambulance). The available medical care and equipment on board, though suboptimal, are still often better than those at the nearest airport; thus, the decision whether to make an unscheduled landing should always be taken in awareness of the actual possibilities for the further care of the patient.

Such decisions are at the sole discretion of the captain and are his or her sole responsibility. Clearly, the advice of a helping physician on board is a very important aid to decision-making, but the captain has more to consider than just the medical care of the ill passenger. The safety of the other passengers on board (often more than 300 of them; on the A380, more than 500) and of the crew must be considered as well. Thus, the captain may reach a well-founded decision that is the opposite of what one might expect from the point of view of individual, patient-centered medicine alone.

Unscheduled landings.

The captain discusses this option with the helping physician. In doubtful cases, the helping physician should now (at latest) speak by satellite telephone with a physician on the ground who has special expertise in aviation medicine.

Opportunities for prevention: evaluating flight-worthiness before the trip

In some cases, the likelihood of a medical incident on board can be minimized by suitable preventive measures taken in advance. The gate crew is trained to identify passengers with markedly impaired physical abilities or severe medical conditions and to address them directly, requesting whenever necessary that their flight-worthiness be evaluated by a physician of the appropriate specialty before the passenger boards the plane. The airlines’ right to do this is derived from their overall responsibility for safety on board. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) has issued relevant recommendations (23). A physician designated by the airline can refuse transport, or permit it only under certain conditions, to persons with acute or chronic illnesses that might compromise the overall safety of the flight.

Medical contraindications to flying include:

infectious and contagious diseases,

decompensated cardiac and respiratory diseases,

poorly controlled epilepsy,

acute or poorly controlled psychosis,

intraocular air or gas inclusions,

intracerebral air inclusions,

ileus, and

pregnancy beyond the 36th week of gestation (for uncomplicated pregnancies) or beyond the 28th week of gestation (for complicated or twin pregnancies).

Evaluating flight-worthiness before the trip.

The gate crew is trained to identify and address passengers with impaired physical abilities or severe medical conditions, requesting if necessary that their flight-worthiness be evaluated by a medical specialist before boarding.

Medical recommendations before flying

Cardiac and respiratory diseases are the most important considerations for risk assessment because of the low partial pressure of oxygen in the cabin atmosphere. For individual assessment of flight-worthiness, the guidelines of the British Thoracic Society (24) are especially useful for persons with respiratory diseases, and the recommendations of Smith et al. (25) for those with cardiovascular diseases.

In general, the risk of a medical incident increases with the age of the traveler, the distance to be flown, and the duration of the flight. The climatic and hygienic conditions at the point of departure can also influence the frequency of in-flight medical incidents.

Physicians counseling patients in travel-related medicine should make an individual assessment of the effects of the physiological changes expected to occur in the aircraft cabin (mild hypoxia, mild hyperventilation, and faster pulse, in an environment of low humidity) and judge the patient’s physiological reserve when confronted with them. The patient’s drug regimen may also need to be adjusted after careful consideration of time-zone differences and the accompanying shift of the circadian rhythm.

Risk assessment before flying.

Cardiovascular and respiratory diseases are the most important considerations for risk assessment because of the low partial pressure of oxygen in the cabin atmosphere.

Patients with respiratory disease are often given particular attention. Such persons should not fly if currently suffering from an exacerbation of a chronic pulmonary condition, or if they regularly need supplemental oxygen at home for activities less demanding than a 100-meter walk. Patients with low tolerance for hypoxia must be thoroughly informed of the risks of flying (or travel by other means) and medically prepared for the trip on an individual basis; the same holds for patients with congestive heart failure, renal failure, or hepatic cirrhosis. The appropriate preparations may include vaccination (against hepatitis A, meningococci, tick-borne encephalitis, cholera, and other diseases) and prophylactic medication (e.g., against malaria).

Support for acutely or chronically ill passengers

Many airlines have special information booklets for passengers with physical and mental impairments and disabilities. Individual counseling is also provided to patients and medical colleagues for optimal support of the planned voyage.

Aside from counseling in aviation medicine, some airlines also offer specific transport options, e.g., the booking of extra seats if special positioning is needed, transport with the passenger lying on a stretcher in the cabin, or long-distance intensive care transport in a patient-transport compartment (PTC, Figure 3). Intensive care transport on long-distance flights is offered exclusively by Lufthansa; the transport module was developed in the 1990s by the airline’s medical and technical departments.

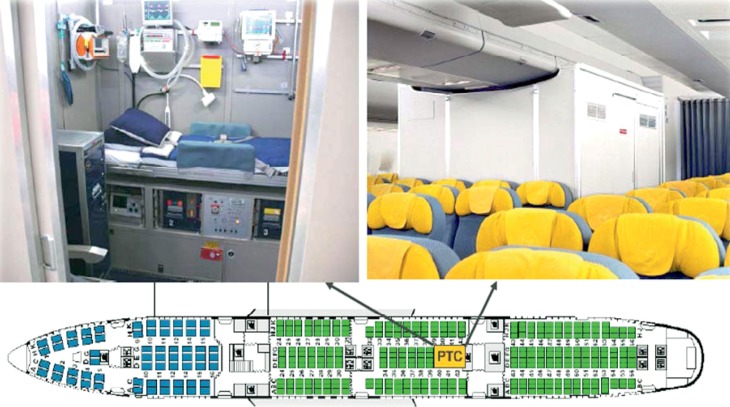

Figure 3.

Patient-transport compartment (PTC) for intensive care on board Lufthansa commercial long-distance aircraft on intercontinental routes. The configuration on board a Boeing 747–400 is shown. Three rows of seats are removed to make room for the PTC. Backup devices are present for all vital medical equipment (for monitoring, artificial ventilation, infusions, etc.) in case of failure. 13 000 L of oxygen (gas volume) are carried on the flight. The patient is accompanied by one intensive care nurse and one physician

Patients with (for example) ventilatory disturbances or limited cardiopulmonary function can use a supplemental oxygen unit, approved for use in flight, that delivers up to 5 liters of oxygen per minute via nasal prongs. This so-called Wenoll system can also be used to control peripheral oxygen saturation with the aid of an integrated pulse oximeter (Figure 4). Portable oxygen concentrators, such as are available for home use, and other medical devices (e.g., continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP] devices for sleep apnea) may be taken on the plane, and some may also be used on board. Specific information on the permitted use of various devices and the necessary battery running times should be requested from the airline at least 48 hours before the flight.

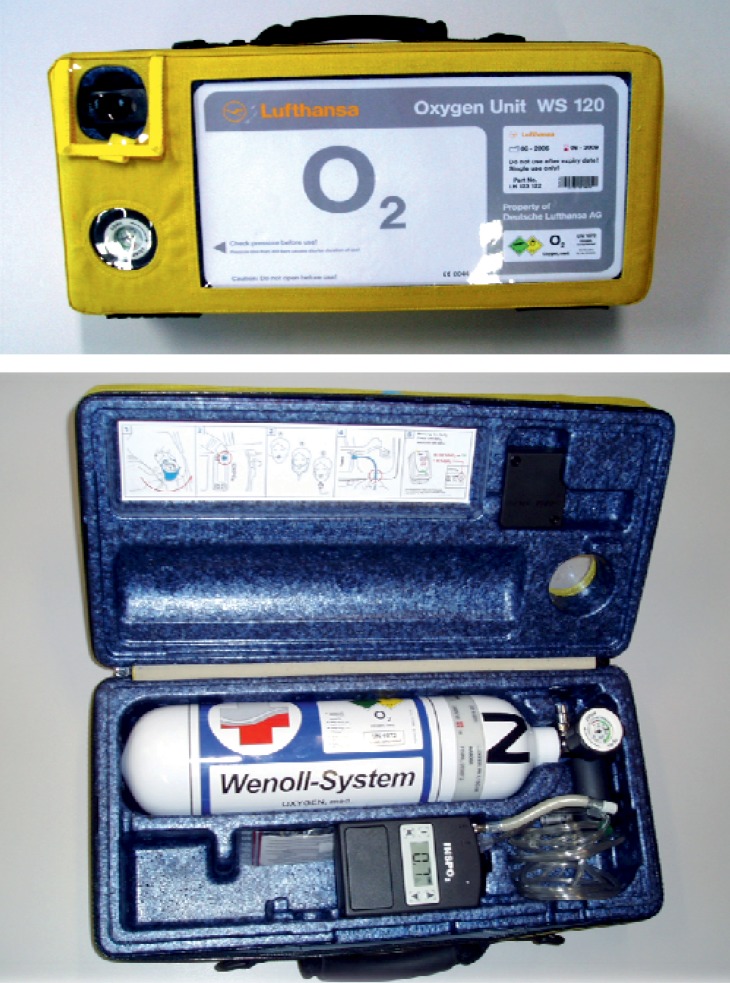

Figure 4.

Supplemental oxygen: a 2 L carbon-composite cylinder at a pressure of 300 bar. Oxygen flows of 1.2 to 5.2 L/min can be achieved for 10 to 20 hours with the aid of an electronic valve (actuated by the drop in pressure during inspiration). This system is used by Lufthansa, Swiss, Air France, and other airlines. A pulse oximeter is incorporated in the shockproof hard-shell case

Travel medicine: counseling for passengers.

The physician should make an individual assessment of the effects of the physiological changes expected to occur in the aircraft cabin and judge the patient’s physiological reserve when confronted with them.

Overview

Medical incidents and emergencies on commercial aircraft present an unusual challenge to everyone involved. Knowledge of the medical aspects of such events and of other special considerations relating to the in-flight situation can be of great help to physicians who are called on to help. All physicians can lower the probability of such events by properly advising their patients with acute or chronic illnesses who are at elevated risk and are contemplating an airplane trip. A pre-flight medical evaluation can also be requested from an airline physician.

Recent technical and logistical advances have made it possible for chronically and acutely ill patients to travel safely on long-distance flights as long as they receive the necessary support. Even intubated and artificially ventilated patients can be safely transported over long distances with provision of in-flight intensive care services.

Acutely ill persons on board.

Patients with chronic and acute illnesses can now travel safely on long-distance flights. Even intubated and artificially ventilated patients can be safely transported over long distances with in-flight intensive care.

Further information on CME.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education. Deutsches Ärzteblatt provides certified continuing medical education (CME) in accordance with the requirements of the Medical Associations of the German federal states (Länder). CME points of the Medical Associations can be acquired only through the Internet, not by mail or fax, by the use of the German version of the CME questionnaire within 6 weeks of publication of the article.

See the following website: cme.aerzteblatt.de.

Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the cme.aerzteblatt.de website under “meine Daten” (“my data”), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate.

The solutions to the following questions will be published in issue 45/2012.

The CME unit “Drug Interactions” (issue 33–34/2012) can be accessed until 1 October 2012. For issue 41/2012, we plan to offer the topic “Viruses acquired abroad—what does the primary care physician need to know?”

Solutions to the CME questions in issue 29–30/2012:

Führer D, Bockisch A, Schmid K: Euthyroid Goiter with and without

Nodules—Diagnosis and Treatment.

Solutions: 1b, 2a, 3e, 4a, 5b, 6e, 7d, 8a, 9c, 10d

Please answer the following questions to participate in our certified Continuing Medical Education program.

Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

What is the approximate altitude to which the cabin of a commercial airliner at cruising altitude is pressurized?

6000 feet/approx. 2000 m

8000 feet/approx. 2400 m

10 000 feet/approx. 2800 m

12 000 feet/approx. 3200 m

14 000 feet/approx. 3600 m

Question 2

Which of the following is a physiological effect of the cabin atmosphere of a commercial airliner at cruising altitude?

Low intraocular pressure

Marked bradycardia

Mild paresthesia

Mild hyperventilation

Moderate hypersalivation

Question 3

Which of the following is true of the partial pressure of oxygen in a commercial airliner at cruising altitude?

It is 25–30% lower than at sea level

It is higher than at sea level

The oxygen content is higher than at sea level, but the partial pressure is lower

It is the same as at sea level

It is 15% higher in tropical regions

Question 4

What was the most common action of physicians in medical incidents on Lufthansa flights?

Checking oxygen saturation

Giving oxygen

Using a defibrillator

Giving medications

Measuring blood pressure

Question 5

What additional medical equipment must be carried on an airplane of a European airline flying to the USA, beyond the requirements within Europe?

A diagnostic kit including a sphygmomanometer, a glucometer, and a stethoscope

A drug kit with ampoules of epinephrine, ketamine, diazepam, midazolam, aspirin, heparin, and urapidil

A pulse oximeter

An infusion system with normal saline

a rapid test for procalcitonin (PCT) and troponin (TrT or TrI)

Question 6

What is the probability that physicians traveling on an airplane will be involved in a medical incident on board?

86% for every 18 intercontinental flights

89% for every 20 intercontinental flights

92% for every 22 intercontinental flights

95% for every 24 intercontinental flights

98% for every 26 intercontinental flights

Question 7

What must be borne in mind by patients who intend to use a portable oxygen concentrator on an airplane?

Such devices are not allowed on commercial aircraft.

Such devices may be used in flight without any restriction.

Such devices must be checked as special baggage.

Permission to use such devices on board must be obtained from the airline at least 48 hours in advance.

Question 8

Which of the following is true of the air in an airplane cabin?

It is carried along in pressurized containers.

It is enriched with oxygen.

Disinfectant is added to it.

It is partially recirculated, filtered, and mixed with air from outside.

Its humidity is controlled by the addition of fine aerosols.

Question 9

What is generally recommended to prevent thromboses in persons without risk factors who will be flying longer than 8 hours?

compressive stockings

aspirin

adequate fluid intake (>2 L) to prevent dehydration

brief exercise breaks in the aisle every 45 minutes

individualized prophylaxis

Question 10

Which of the following is true of airplane passengers with acute or chronic illnesses?

They must carry a note from the appropriate health authorities.

They must have written permission to enter the destination country.

They are not allowed to travel on European airlines.

Airlines can deny them permission to fly.

They have a right to be taken on board and may demand this from gate personnel.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors are employees of Deutsche Lufthansa AG. Prof. Graf and Prof. Stüben also own Lufthansa stock.

Prof. Stüben has received honoraria from Lilly for the preparation of continuing medical education events.

References

- 1.Tonks A. Cabin fever. BMJ. 2008;336:584–586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39511.444618.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Von Mülmann M. Die Flugzeugkabine. In: Stüben U, editor. Taschenbuch Flugmedizin. Berlin: MWV Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 2008. pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muhm JM, Rock PB, et al. Effect of aircraft-cabin altitude on passenger discomfort. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:18–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirth D, Rumberger E. Fundamentals of aviation physiology. In: Curdt-Christiansen C, Draeger J, Kriebel J, editors. Principles and practice of aviation medicine. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing; 2009. pp. 71–149. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cocks R, Liew M. Commercial aviation in-flight emergencies and the physician. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2006.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverman D, Gendreau M. Medical issues associated with commercial flights. Lancet. 2009;373:2067–2077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowdall N. Is there a doctor on the aircraft? Top 10 in-flight medical emergencies. BMJ. 2000;3211:336–1337. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7272.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung KKC, Chan EYY, Cocks RA, Ong RM, Rainer TH, Graham CA. Predictors of flight diversions and death for in-flight medical emergencies in commercial aviation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1401–1402. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charles RA. Cardiac Arrest in the Skies. Singapore Med J. 2011;52:582–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson HG, Baglin TP. Guidelines on travel-related venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2011;152:31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehmann R, Suess C, Leus M. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and long-term prognosis of travel-associated pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:233–241. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz T, Siegert G, Oettler W. Venous thrombosis after long-haul flights. Arch Intern Med. 2009;163:2759–2764. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scurr JRH, Ahmad N, Thavarajan D, Fisher RK. Traveller’s thrombosis: airlines still not giving passengers the WRIGHT advice! Phlebology. 2010;25:257–260. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2009.009070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thibeault C, Evans A. Emergency medical kit for commercial airlines: an update. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2007;78:1170–1171. doi: 10.3357/asem.2188.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen SJ, Chang HL, Cheung TY, et al. Transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome on aircraft. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2416–2422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foxwell AR, Roberts L, Lokuge K, Kelly PM. Transmission of influenza on international flights, may 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1188–1194. doi: 10.3201/eid1707.101135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangili A, Gendreau MA. Transmission of infectious diseases during commercial air travel. Lancet. 2005;365:989–996. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71089-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brownstein JS, Wolfe CJ, Mandl KD. Empirical evidence for the effect of airline travel on inter-regional influenza spread in the United States. PLoS Med. 2006;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gendreau MA, DeJohn C. Responding to medical events during commercial airline flight. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1067–1073. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shepherd B, Macpherson D, Edwards CM. In-flight emergencies: playing The Good Samaritan. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:628–631. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.99.12.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace WA. Managing in flight medical emergencies. BMJ. 1995;311:374–375. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaul G, Von Mülmann, M . Allgemeine Bedingungen bei medizinischen Notfällen. In: Stüben U, editor. Taschenbuch Flugmedizin. Berlin: MWV Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 2008. pp. 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Air Transport Association (IATA) Medical Manual. www.iata.org/whatwedo/safety_security/safety/health/Documents/medical-manual-jan2011.pdf. 4th edition 2011. Jan,

- 24.Shrikrishna D, Coker RK. Air travel working party of the british thoracic society standards of care committee managing passengers with stable respiratory disease planning air travel: British Thoracic Society recommendations. Thorax. 2011;66:831–833. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith D, Toff W, Joy M. Fitness to fly for passengers with cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2010;96(Suppl 2):ii1–16. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.203091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]