Abstract

Objective

Genital tract secretions exhibit bactericidal activity against Escherichia coli. We hypothesized that this defense may be modulated during pregnancy.

Study Design

Secretions were collected by vaginal swab from 70 pregnant women (35–37 weeks gestation) and 35 non-pregnant controls. Escherichia coli were mixed with swab eluants or control buffer and colonies enumerated to measure bactericidal activity. Cytokines, chemokines and antimicrobial peptides were quantified by Luminex or ELISA.

Results

Pregnant women had significantly greater bactericidal activity, higher concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines and lower levels of beta defensins compared to controls. Seven (10%) pregnant and 8 (23%) non-pregnant women were vaginally colonized with Escherichia coli; colonization was inversely associat ed with bactericidal activity.

Conclusion

The soluble mucosal immune environment is altered in pregnancy. We speculate that the observed changes may protect against colonization and ascending infection and could provide a biomarker to identify pregnant women at risk for infectious complications including preterm birth.

Keywords: Cytokines/chemokines, Defensins, E. coli, Pregnancy

Introduction

Prevention of preterm birth and perinatal infection is a global health imperative. Worldwide, 13 million infants (10% of births) are born prematurely each year and 30% of preterm births are associated with infection.1 Preterm delivery is responsible for almost half of all infant mortality in the United States.2–4 The cause of most preterm births is unknown, but evidence strongly implicates infection and changes in the genital tract mucosal immune environment as primary triggers.5–9 For example, in the Vaginal Infections and Prematurity (VIP) Study of over 13,000 pregnant women, an increase in Escherichia coli (E. coli) or Klebsiella pneumoniae was associated with an increased risk of preterm birth and a higher adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for preterm birth than any other factor identified in the data set (AOR 2.99, 95% CI 1.37–6.53).10 E. coli is currently the most frequently isolated pathogen in neonatal early-onset sepsis and meningitis11 and accounted for 41% of early-onset sepsis in very low birth weight preterm infants.12

Genital tract secretions from healthy non-pregnant women exhibit variable bactericidal activity against E. coli.13 We speculate that this activity, which likely reflects cumulative interactions between multiple mediators secreted by genital tract epithelial cells, immune cells, and vaginal microbiota, may provide a biomarker of a healthy mucosal immune environment. However, whether this ex vivo bactericidal activity provides clinical protection against infection remains unclear. Moreover, no studies have examined the bactericidal properties of genital tract secretions during pregnancy. To begin to elucidate the role of genital tract mucosal immunity in preventing or promoting preterm birth, the mucosal immune environment in healthy term pregnancy must first be defined.

We therefore designed a cross-sectional study to examine the mucosal immune environment and vaginal E. coli colonization in near term pregnant women compared to non-pregnant controls. We hypothesized that E. coli colonization may be inversely associated with bactericidal activity.

Materials and Methods

Participants and sample collection

Following Institutional Review Board approval from the Montefiore Medical Center, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Pregnant women were approached during their routine GBS screening prenatal visit (35 to 37 weeks of gestation) and non-pregnant women were approached during a routine gynecologic visit. Exclusion criteria included age less than 18 years, evidence of active genitourinary infection, abnormal Pap smear within the past year, current antibiotic or steroid use within the past month, sexual intercourse within the last 48 hours (as semen may modify the mucosal immune environment), and major chronic medical illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosis, or HIV infection. Samples were collected from March 2010 to October 2011.

Demographic and clinical data were collected for each participant. Since self-collected swabs for GBS screening are the standard of care in many obstetrical clinical settings,14–16 participants were given the option to have observed self-collection or physician collection of the following study-related vaginal swabs: cotton swab for measurement of vaginal wall pH (Whatman pH paper, pH 3.8–5.5); flocked swab to sample genital tract secretions; and cotton swab for E. coli culture.

Sample processing

The swabs for culture were transported to the Montefiore Clinical Microbiology Lab and cultured for E. coli on MacConkey plates; the plates were evaluated for bacterial colonies after 24 and 48 hours of incubation. The swabs for genital tract secretions were placed in a 1.5 ml sterile eppendorf tube that had been pre-filled with 0.5 ml of sterile saline and transported on ice to the laboratory and processed within 6 hours of collection. The sample was vortexed, the swab was compressed against the side of the tube to maximize elution of the secretions, and clarified by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 7 minutes at 4°C. The eluant was divided into 50 μl aliquots and stored at −80°C.

Bactericidal activity

E. coli (ATCC strain 4382627) was grown overnight to stationary phase and then 3μl of bacteria (~109 cfu/ml) were mixed with 27 μl of swab eluant or control buffer (20 mmol/L potassium phosphate, 60 mmol/L sodium chloride, 0.2 mg/ml albumin, pH 4.5) and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. The mixtures were then further diluted in buffer (to yield 800–1000 colonies on control plates) and plated on agar (Acros Organics, Fischer Scientific) enriched with trypticase soy broth (Fluka, Sigma-Aldrich). Colonies were counted using ImageQuant TL v2005 after an overnight incubation at 37°C. All samples were tested in duplicate and the percentage inhibition was determined relative to the colonies formed on the control plates. To evaluate whether viable bacteria were present in the vaginal eluants, random samples were directly plated onto agar and evaluated for bacterial growth. Of note, none of the eluants yielded bacterial growth.

Measurement of protein and immune mediators

Total protein concentration was measured by microBCA™ Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) in swab eluants diluted 1:4. The concentration of interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, interferon alpha 2 (IFN-α2), macrophage inhibitory protein-1 alpha and 1 beta (MIP-1α, MIP-1β), and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) were determined by multiplex assay with beads from Chemicon International (Billerica, Ma, measured using Luminex100 (Austin, Texas) and analyzed using StarStation (Applied Cyotmetry Systems, Sacramento, CA) in eluants diluted 1:2. The levels of all other mediators were determined using commercial ELISA kits with dilutions as noted: secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) (1:1000 dilution of eluant) (R&D Systems), human beta defensin (HBD)-1 (1:25), HBD-2 (1:100) and HBD-3 (1:25) (Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX), and human neutrophil peptides 1–3 (HNP1-3) (1:200) (Hycult Biotech, Uden, The Netherlands). The lower limits of detection (LOD) for each assay were (pg/ml): HNP1-3, 156; SLPI, 25; HBD-1, 25; HBD-2, 5; HBD-3, 20; IL-1α, 3.5; IL-1β, 0.4; IL-6, 0.3; IL-8, 0.2; IFN-α2, 24.5; IL-1ra, 2.9; MIP-1α, 3.5; MIP-1β, 4.5; RANTES, 1.0. The dilutions selected for each analyte were based on previous studies performed in our lab. Insufficient material was available to repeat samples that fell below the LOD at a lower dilution. Therefore, concentrations that fell below the LOD were set at the midpoint between zero and the LOD multiplied by the dilution factor. Concentrations that fell above the highest detection concentration were repeated at a higher dilution factor. Mediators with >45% of the samples below the LOD were dichotomized; All other mediators were reported as continuous variables.

Statistical analysis

To reduce skewness in the distribution, log10 transformed concentrations of all mediators were used in the analyses. Categorical variables were compared between groups by Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared by Student’s t test or the Mann-Whitney U test, depending on the distribution of the data. Spearman rank-order correlation was calculated to assess correlations between mediators and bactericidal activity. A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered significant and a False Discovery Rate (FDR) adjusted p-value was reported to account for multiple comparisons. Heat maps were generated to graphically display the correlations among the two cohorts of pregnant and non-pregnant women.

A multivariable linear regression was performed to assess for predictors of bactericidal activity against E. coli. A backward stepwise regression approach was used and age, race, and smoking were placed in the model a priori; soluble immune mediators that correlated with E. coli bactericidal activity at an FDR-adjusted p-value of <0.05 were also added. Mediators that did not have a significant association with bactericidal activity against E. coli and reduced the fit of the model were removed. Regression diagnostics were performed to ensure reasonable estimates and fit. All statistical tests were performed using STATA version 11.0 (College Station, TX), R version 2.12.2, and GraphPad Prism version 5. (La Jolla, CA).

Results

Description of participants

105 pregnant women were assessed for eligibility during their third trimester and 70 enrolled. Reasons for exclusion included declined participation (n=15), abnormal Pap smear (n=10), active infection (n=5), recent intercourse (n=3), and persistent asthma requiring steroid therapy (n=2). Thirty-seven non-pregnant women were approached for recruitment in the control arm and 35 enrolled; two women were excluded because of recent sexual intercourse. There were no significant differences with respect to age, current smoking status, history of sexually transmitted infections, vaginal wall pH, or method of swab collection (Table 1). The groups did differ with respect to race (p=0.05). Among the non-pregnant women, 76% were using hormonal contraception and the remaining 24% were having normal menstrual cycles; phase of cycle was not determined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of pregnant and non-pregnant women.

| Pregnant (n=70) | Non-pregnant (n=35) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 28.3 (6.5) | 30.9 (6.2) | 0.06 |

|

| |||

| Race, n (%) | 0.05 | ||

| White | 47 (67) | 30 (86) | |

| Black | 18 (26) | 2 (6) | |

| Other | 5 (7) | 3 (8) | |

|

| |||

| Current Smoker, n (%) | 1 (1) | 3 (9) | 0.1 |

|

| |||

| History of genital herpes, n (%) | 4 (6) | 3 (9) | 0.3 |

|

| |||

| History of chlamydia, n (%) | 6 (9) | 4 (11) | 0.5 |

|

| |||

| History of gonorrhea, n (%) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0.5 |

|

| |||

| History of genital warts, n (%) | 4 (6) | 3 (9) | 0.6 |

|

| |||

| Contraception | NAa | NAa | |

| None | 9 (26) | ||

| Barrier methods | 11 (31) | ||

| Oral contraceptive pills | 5 (14) | ||

| Intra-vaginal ring | 3 (9) | ||

| Progesterone injectable | 5 (14) | ||

| Progestin-containing IUD | 2 (6) | ||

|

| |||

| Lateral vaginal wall pH, mean (SD) | 4.8 (0.02) | 4.8 (0.37) | 0.7 |

|

| |||

| Method of Swab Collection n (%) | 0.5 | ||

| Physician-collection | 44 (63) | 21 (60) | |

| Observed self-collection | 26 (37) | 14 (40) | |

Not applicable

Pregnant women have greater E. coli bactericidal activity

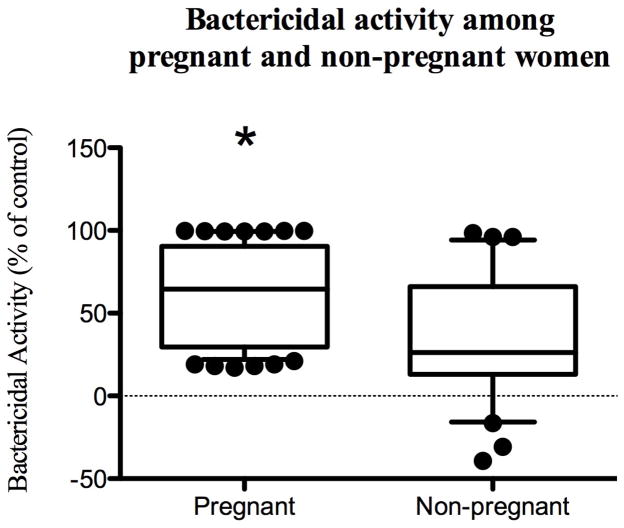

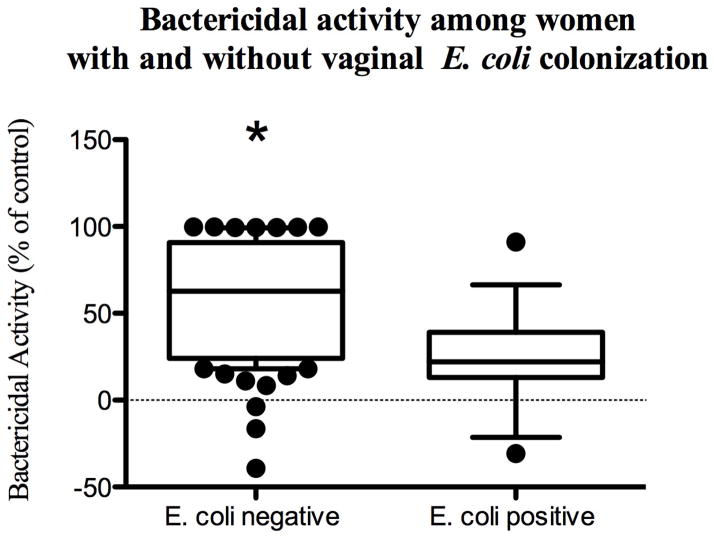

Genital tract secretions collected from pregnant women had significantly greater bactericidal activity against E. coli compared to non-pregnant women (median [range] 65% [17–99] vs. 26.2% [−39–98], p<0.001; Fig. 1). Moreover, the pregnant women were less likely to be vaginally colonized with E. coli (10% vs. 23%, p=0.002) and bactericidal activity was significantly less in women who were colonized compared to women who were not (62.7% [39–99] vs. 22% [−30.7–91], Fig. 2), suggesting that activity may protect against vaginal colonization. Pregnancy, E. coli colonization, and HBD-3 were significant predictors of bactericidal activity and remained significant after adjusting for age, race, smoking, and immune mediators within the genital tract (Table 2). Pregnancy was associated with a 26% increase in bactericidal activity compared to controls. Independent of pregnancy status, women who were vaginally colonized with E. coli had a 20% reduction in their bactericidal activity compared to women whose vaginal cultures did not yield E. coli. In addition, in women whose HBD-3 levels were above the limit of detection, there was an associated 21% increase in bactericidal activity. Of note, vaginal pH was adjusted for in the multivariable logistic regression. However, there was no significant association with vaginal pH and bactericidal activity and it was subsequently removed due to improvement in model fit.

Figure 1. Bactericidal activity against E. coli among pregnant and non-pregnant women.

Vaginal eluants or control fluid were mixed with E. coli and colonies counted after an overnight incubation. Control plates had 800–1000 colony forming units (cfu). Boxplots show the percentage inhibition relative to control and line indicates median (10–90%) and circles are outliers. The asterisk denotes a significant difference relative to controls.

Figure 2. Bactericidal activity is inversely associated with E. coli vaginal colonization.

Boxplots show percentage inhibition of cfu among pregnant and non-pregnant women stratified by E. coli vaginal colonization. The asterisk denotes a significant difference relative to controls.

Table 2.

Multivariate linear regression model of bactericidal activity against E. coli.

| Linear regressiona | β-coefficient (SE) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy | 25.7 (8.5) | 0.003b |

|

| ||

| E. coli colonization | −20.1 (9.3) | 0.031b |

|

| ||

| Age | 0.29 (0.5) | 0.594 |

|

| ||

| Racec | ||

| Black | −6.9 (8.6) | 0.421 |

| Other | 15.7 (12.8) | 0.223 |

|

| ||

| Current Smoker | −25.1 (17.3 | 0.151 |

|

| ||

| HBD-2 | .00002 (0.00009) | 0.838 |

|

| ||

| HBD-3 (Detectable) | 20.5 (9.1) | 0.026b |

|

| ||

| IL-1α | −0.0003 (0.002) | 0.899 |

|

| ||

| IL-1β | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.282 |

|

| ||

| IL-8 | .002 (0.001) | 0.527 |

Raw values of the mediators were entered into the model; HBD-3 was entered as a dichotomized variable.

p<0.05 considered significant

White as reference

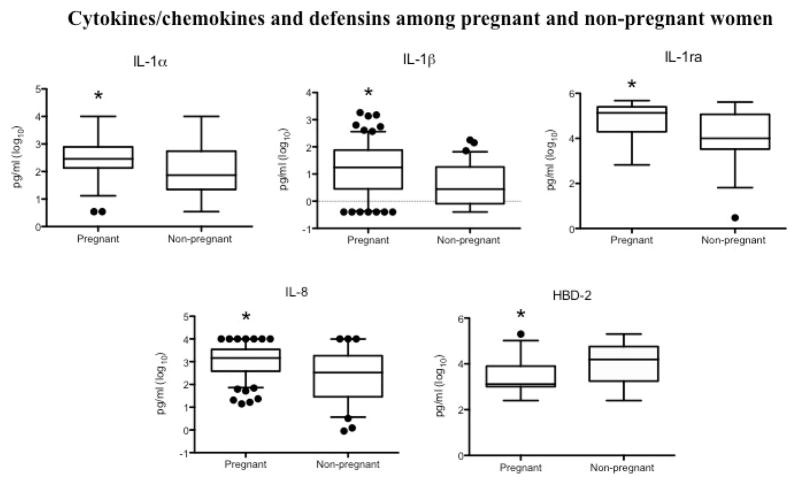

Changes in soluble mucosal immune mediators and correlations with E. coli activity

To evaluate whether the increased bactericidal activity observed in pregnant women was associated with differences in mucosal immune mediators, we compared the concentrations of total protein, cytokines, chemokines and select antimicrobial peptides recovered in vaginal eluants between pregnant and non-pregnant women. There were no significant differences in total protein. However, compared to controls, pregnant women had significantly higher levels of several cytokines including IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-1ra, and the chemokines including IL-8 and RANTES (Figure 3, Table 3). IFN-α2 was below the limit of detection in the majority of pregnant and non-pregnant women, and did not differ significantly between the two groups. In contrast to the increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, pregnant women had significantly lower levels of the epithelial beta defensins, HBD-2 (Figure 3) and HBD-3 (Table 3). No differences in HBD-1, HNP1-3 or SLPI were observed.

Figure 3. Pregnancy is associated with significantly increased pro-inflammatory cytokines and decreased defensins.

Box-plots show the concentrations of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-8 and HBD-2 after log10 transformation. The line indicates median values (10–90%) and circles indicate outliers. The asterisk denotes a significant difference relative to controls.

Table 3.

Total protein, defensins, cytokines, and chemokines for pregnant vs. non-pregnant women after log10 transformation.

| Mediatora | Percentage of subjects with levels below LODa (n=105) | Pregnant (n=70) | Non-pregnant (n=35) | FDR adjusted p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Protein (μg/ml) | 2 | 3.1 (1.4–3.7) | 3.1 (2.1–3.7) | 0.743 |

|

| ||||

| Alpha and Beta Defensins

| ||||

| HNP 1–3 (pg/ml) | 38 | 4.7 (4.1–6) | 4.6 (4.2–5.7) | 0.697 |

|

| ||||

| HBD-1 (pg/ml) | 42 | 3.2 (2.5–4.3) | 3.2 (2.5–4.3) | 0.543 |

|

| ||||

| HBD-2 (pg/ml) | 17 | 3.1 (2.4–5.3) | 4.2 (2.4–5.3) | <0.001c |

|

| ||||

| HBD-3 n (%)b | 58 | <0.001c | ||

| Detectable (>250 pg/ml) | 11 (16) | 33 (94) | ||

| Undetectable (≤250 pg/ml) | 59 (84) | 2 (6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Pro-Inflammatory Mediators

| ||||

| IL-1α (pg/ml) | 5 | 2.5 (0.5–4) | 1.9 (0.5–4) | 0.017c |

|

| ||||

| IL-1β (pg/ml) | 12 | 1.2 (−0.4–3.3) | 0.4 (−0.4–2.3) | 0.012c |

|

| ||||

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 0 | 0.3 (−1.2–2.5) | 0.02 (−1.0–1.2) | 0.062 |

|

| ||||

| IL-8 (pg/ml) | 0 | 3.2 (1.2–4.0) | 2.5 (−0.4–4.0) | 0.007c |

|

| ||||

| IFN- α2, n (%)b | 91 | 0.480 | ||

| Detectable (>24.5 pg/ml) | 6 (9) | 3 (9) | ||

| Undetectable (≤24.5 pg/ml) | 64 (91) | 32 (91) | ||

|

| ||||

| MIP-1α, n (%)b | 73 | 0.459 | ||

| Detectable (>3.5 pg/ml) | 17 (24) | 11 (31) | ||

| Undetectable (≤3.5 pg/ml) | 53 (76) | 24 (69) | ||

|

| ||||

| MIP-1 β, n (%)b | 89 | 0.747 | ||

| Detectable (>4.5 pg/ml) | 9 (13) | 3 (9) | ||

| Undetectable (≤4.5 pg/ml) | 61(87) | 32 (91) | ||

|

| ||||

| RANTES n (%)b | 49 | |||

| Detectable (>2 pg/ml) | 43 (59) | 11 (31) | 0.002c | |

| Undetectable (≤2 pg/ml) | 27 (41) | 24 (69) | ||

|

| ||||

| Anti-Inflammatory Mediators

| ||||

| IL-1ra (pg/ml) | 1 | 5.1 (2.8–5.7) | 4.0 (0.5–5.6) | 0.006c |

|

| ||||

| SLPI (pg/ml) | 21 | 5.3 (4.4–6.3) | 5.7 (4.4–6.3) | 0.447 |

Limit of detection

Median (range) reported except for HBD-3, IFN-α2, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES which were dichotomized around the limit of detection.

p<0.05 considered statistically significant

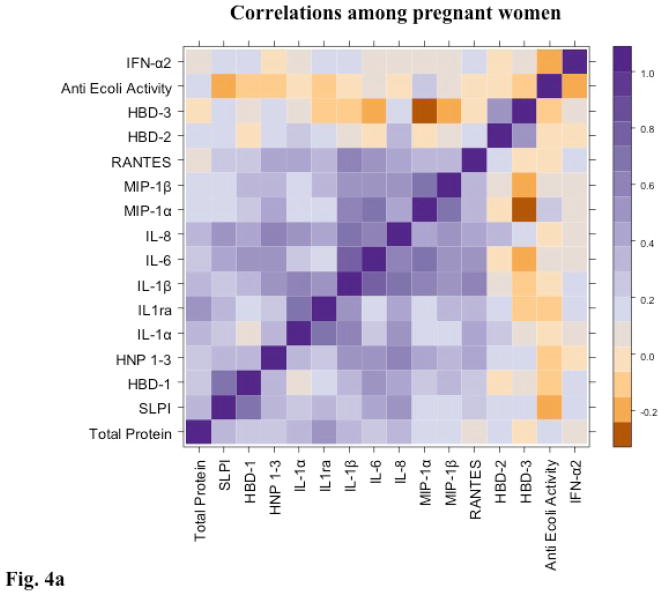

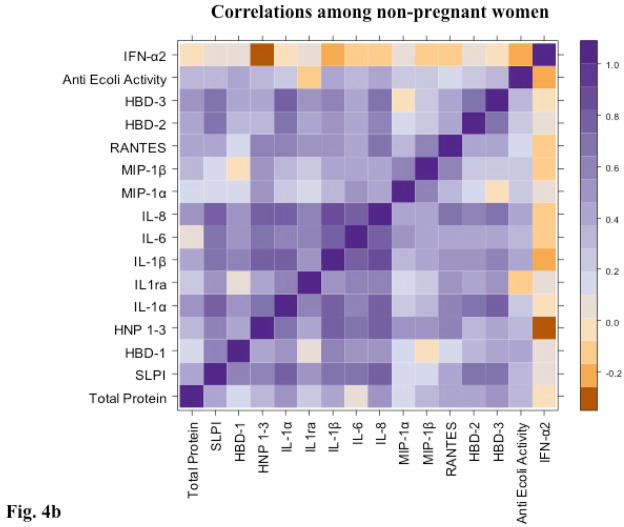

The bactericidal activity against E. coli correlated modestly and significantly with several immune mediators in the non-pregnant cohort including SLPI (ρ=0.38, p=0.02), HBD-1 (ρ=0.45, p=0.002), HBD-2 (ρ=0.44, p=0.007), IL-1β (ρ=0.37, p=0.04), IL-6 (ρ=0.35, p=0.04), and IL-8 (ρ=0.42, p=0.01) (Figure 4). However, bactericidal activity did not correlate with any of the mediators among the pregnant women. In general, cytokines and chemokines clustered together more tightly in secretions obtained from non–pregnant compared to pregnant women, suggesting alterations in the cytokine-chemokine-defensin network within the genital tract in pregnancy.

Figure 4. Correlations between cytokines, chemokines and defensins are reduced in pregnant women.

A color-coded heat map of Spearman correlation coefficients between soluble immune mediators and endogenous bactericidal activity against E. coli for pregnant (a) and non-pregnant (b) participants.

Comment

This cross sectional study demonstrates that healthy near term pregnant women have greater E. coli bactericidal activity in their genital tract secretions and were less likely to be vaginally colonized with these pathogenic bacteria than non-pregnant controls. Moreover the activity was inversely associated with colonization suggesting that pregnancy induces changes in the mucosal immune environment to protect against one of the more common causes of perinatal infection linked to preterm birth.17–19

The bactericidal activity of vaginal secretions correlated modestly with several cytokines and antimicrobial peptides in the non-pregnant cohort, but did not correlate with any of the mediators in the pregnant cohort. This observation suggests that different molecules may contribute to the ex vivo bactericidal activity in pregnancy. Protective molecules may include proteins secreted by genital tract epithelial or immune cells as well as contributions from vaginal microbiota. The bactericidal activity was significantly less in women colonized with E. coli linking the activity to vaginal microbiota. However, whether the loss of bactericidal activity facilitates E. coli colonization or whether E. coli colonization (which has been previously shown to be inversely correlated with a predominance of lactobacilli20) leads to a loss in activity will require prospective longitudinal studies.. The potential role of lactobacilli in contributing to the bactericidal activity is supported by the observations that spent culture supernatants from lactobacillus cultures are bactericidal for E. coli 21 and by studies showing a reduction in E. coli activity in the setting of bacterial vaginosis, a condition associated with a loss in lactobacilli. 13

Consistent with prior studies, we also observed an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in secretions obtained from pregnant women compared to non-pregnant women, but conversely, lower levels of HBD-2 and HBD-3. An increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in genital tract secretions during pregnancy has previously been suggested to be protective. For example, lower levels of IL-8 in secretions sampled at a mean of 29 weeks gestation were associated with a significant risk of delivering newborns with early onset infection (OR=4.9; 95% CI, 1.1–22.8).22 An earlier study also found that decreased concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6 or IL-8 early in pregnancy, is a risk factor for clinical chorioamnionitis.23

The paradoxical finding of decreased HBD-2 and HBD-3 in the setting of increased pro-inflammatory cytokines suggests dysregulation of the normal cytokine-defensin network.24 Dysregulation is also suggested by the more modest correlations between cytokines and chemokines in pregnant compared to non-pregnant women (Figure 4). Few studies have examined levels of HBDs in genital tract secretions during pregnancy. While HBDs are presumed to be protective and have direct bactericidal activity in vitro25, one study found that higher levels of HBD-2 in amniotic fluid were positively associated with preterm premature rupture of membranes.26 Perhaps the higher levels were in response to subclinical infection as fetal tissue responds to E. coli by increasing expression of HBDs.27 Further studies are needed to elucidate the role of HBDs in pregnancy.

The cross sectional design and sampling only at a single time point in healthy near term pregnant women in this first study of bactericidal activity in pregnancy limit the conclusions, but suggest that genital tract secretions may play key roles in mucosal defenses and protect against colonization with bacteria (E. coli) associated with preterm birth and neonatal sepsis. We also did not evaluate participants for other factors that could modulate the mucosal environment including subclinical genitourinary infections28–29, presence of semen in the genital tract30 or, among non-pregnant controls, phase of menstrual cycle or use of hormonal contraception.31 A prospective longitudinal study is underway to examine changes in bactericidal activity, immune mediators, and vaginal microbiota throughout gestation and to link the findings to pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Future studies also should address the antimicrobial activity against other potential pathogens such as Group B Streptococcus. This approach may lead to the discovery of biomarkers predictive of infection and preterm birth as well as the identification of novel strategies to augment host defense to reduce the risk of preterm birth.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by research grant numbers: KL2 RR025749 (JG), UL1 RR025750 (BH), AI076980 (BH), AI079763 (BH), UL1 RR025750 (BH).

We would like to thank Setul Pardanani, MD and the staff at the Comprehensive Family Care Center, Janice Falls, MD, Judy Levy, MD, and Karen Sumner, MD for their help with subject recruitment.

No funding sources or conflict of interest to disclose for acknowledged individuals.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: None of the authors have a conflict of interest

Reprints will not be available

This research was presented as a poster at the 32nd Annual Clinical Meeting of the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, Dallas, TX, February 6-11, 2012.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. New Eng Journ Med. 2000;342:1500–1507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrman RE, Butler AS. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on understanding premature birth and assuring healthy outcomes. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. Preterm birth: causes, consequences, and prevention. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Health Statistics, final natality data. Retrieved September 21, 2010, from www.marchofdimes.com/peristats.

- 4.Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF. Infant mortality statistics from the 2005 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008 Jul 30;57:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei SQ, Fraser W, Luo ZC. Inflammatory cytokines and spontaneous preterm birth in asymptomatic women-a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:393–401. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e6dbc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACOG Practice Bulletin. Assessment of risk factors for preterm birth. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 31, October 2001. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:709–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Holzman CB, Arvidson CG, Chung H, Goepfert AR. Midpregnancy vaginal fluid defensins, bacterial vaginosis and risk of preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:524–31. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318184209b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iams JD, Berghella V. Care for women with prior preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.004. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalan AM, Simhan HN. Mid-trimester cervical inflammatory milieu and sonographic cervical length. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:126.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey JC, Klebanoff MA. Is a change in the vaginal flora associated with an increased risk of preterm birth? Amer Jour of Obstet and Gyn. 2005;192:1341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin CY, Hsu CH, Huang FY, et al. The changing face of early-onset neonatal sepsis after the implementation of a maternal Group B Streptococcus screening and intrapartum prophylaxis policy-a study in one medical center. Pediatr Neonatol. 2011;52:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Sánchez PJ, et al. for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Early onset neonatal sepsis: the burden of Group B Streptococcal and E. coli disease continues. Pediatrics. 2011;127:817–826. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valore EV, Wiley DJ, Ganz T. Reversible deficiency of antimicrobial polypeptides in bacterial vaginosis. Infec and Immu. 2006;74:5693–702. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00524-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease--revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010 Nov 19;59(RR-10):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price D, Shaw E, Howard M, Zazulak J, Waters H, Kaczorowski J. Self-sampling for group B Streptococcus in women 35 to 37 weeks pregnant is accurate and acceptable: a randomized cross-over trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28:1083–8. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arya A, Cryan B, O’Sullivan K, Greene RA, Higgins JR. Self-collected versus health professional-collected genital swabs to identify the prevalence of group B Streptococcus: a comparison of patient preference and efficacy. Eur J Obstet, Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;139:43–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holst E, Goffeng AR, Andersch B. Bacterial vaginosis and vaginal microorganisms in idiopathic premature labor and association with pregnancy outcome. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:176–86. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.176-186.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald HM, O’Loughlin JA, Jolley P, Vigneswaran R, McDonald PJ. Vaginal infection and preterm labour. Br J Obstet GynaecoI. 1991;98:427–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb10335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krohn MA, Thwin SS, Rabe LK, Brown Z, Hillier SL. Vaginal colonization by Escherichia coli as a risk factor for very low birth weight delivery and other perinatal complications. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:606–10. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadieux PA, Burton J, Devillard E, Reid G. Lactobacillus by-products inhibit the growth and virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60( Suppl 6):13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atassi F, Brassart D, Grob P, Graf F, Servin AL. Vaginal Lactobacillus isolates inhibit uropathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;257:132–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalinka J, Krajewski P, Sobala W, Wasiela M, Brzezinska-Blaszczyk E. The association between maternal cervicovaginal proinflammatory cytokines concentrations during pregnancy and subsequent early-onset neonatal infection. J Perinat Med. 2006;34:371–7. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2006.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simhan HN, Caritis SN, Krohn MA, Martinez de Tejada B, Landers DV, Hillier SL. Decreased cervical proinflammatory cytokines permit subsequent upper genital tract infection during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:560–7. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King AE, Critchley HO, Kelly RW. Innate immune defences in the human endometrium. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:116. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-116. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehrer RI, Lu W. Alpha-Defensins in human innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2012;245:84–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iavazzo C, Tassis K, Gourgiotis D, et al. The role of human beta defensins 2 and 3 in the second trimester amniotic fluid in predicting preterm labor and premature rupture of membranes. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010 May;281(5):793–9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1155-4. Epub 2009 Jun 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Lopez G, Flores-Espinosa P, Zaga-Clavellina V. Tissue-specific human beta-defensins (HBD)1, HBD2, and HBD3 secretion from human extra-placental membranes stimulated with Escherichia coli. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:146. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mhatre M, McAndrew T, Carpenter C, et al. Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia is Associated With Genital Tract Mucosal Inflammation. Sex Trans Dis. 2012 Apr;1:32. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318255aeef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mlisana K, Naicker N, Werner L, et al. Symptomatic vaginal discharge is a poor predictor of sexually transmitted infections and genital tract inflammation in high-risk women in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2012 Jul;206(1):6–14. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis298. Epub 2012 Apr 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharkey DJ, Tremellen KP, Jasper MJ, et al. Seminal fluid induces leukocyte recruitment and cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression in the human cervix after coitus. J Immunol. 2012 Mar 1;188(5):2445–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shust GF, Cho S, Kim M, et al. Female genital tract secretions inhibit herpes simplex virus infection: correlation with soluble mucosal immune mediators and impact of hormonal contraception. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010 Feb;63(2):110–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00768.x. Epub 2009 Dec 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]