Abstract

Adult neural stem cells (NSCs) are known to exist in a few brain regions; however, the entity and physiological/disease relevance of adult hypothalamic NSCs (htNSCs) remain unclear. Here, this work showed that adult htNSCs are multipotent and predominantly present in the mediobasal hypothalamus of adult-aged mice. Chronic high-fat-diet feeding led to not only depletion but also neurogenic impairment of htNSCs associated with IKKβ/NF-κB activation. In vitro htNSC models demonstrated that their survival and neurogenesis dramatically decreased upon IKKβ/NF-κB activation but increased upon IKKβ/NF-κB inhibition, mechanistically mediated by IKKβ/NF-κB-controlled apoptosis and Notch signaling. Mouse studies revealed that htNSC-specific IKKβ/NF-κB activation led to depletion and impaired neuronal differentiation of htNSCs, and ultimately the development of obesity and pre-diabetes. In conclusion, adult htNSCs are important for central regulation of metabolic physiology, and IKKβ/NF-κB-mediated impairment of adult htNSCs is a critical neurodegenerative mechanism for obesity and related diabetes.

Keywords: Neural stem cells, hypothalamus, IKKβ, NF-κB, Notch, obesity, diabetes

Adult neurogenesis, a once unconventional concept, has now changed into one impelling topic in neuroscience. Recent research has shown that adult central nervous system (CNS) contains NSCs that generate neural cells including neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes1–15. As appreciated till date, adult NSCs are present prominently in the sub-ventricular zone (SVZ) of the forebrain and the sub-granular zone (SGZ) of hippocampal dentate gyrus1–15. In light of the hypothalamus, Kokoeva et al used Brdu labeling to show postnatal neurogenic activities in the hypothalamus of mice in either CNTF-stimulated16 or basal conditions17. Pierce et al reported cell proliferation in the hypothalamus of mutant mice with AGRP neuronal degeneration18. In this year, McNay et al showed postnatal turnover of arcuate neurons and its impairment in obesity conditions19. Also in this year, Lee el al reported that tanycytes in the median eminence are important for postnatal hypothalamic neurogenesis, an observation based on newborn pups or pre-adult young mice20. We are interested in understanding the identity and characteristics of adult hypothalamic NSCs at post-development ages and their physiological actions and especially the disease relevance. It has been appreciated that environmental changes such as chronic high-fat-diet (HFD) feeding induce hypothalamic dysfunctions to cause and promote obesity and diabetes. Recent research revealed that proinflammatory pathway of IκB kinase (IKKβ) and downstream nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) mediates HFD-induced hypothalamic inflammation to cause metabolic syndrome21–25. It is of note that in addition to being an inflammatory regulator, IKKβ/NF-κB controls cell survival, growth, apoptosis and differentiation in cell-specific manners26–29. While IKKβ/NF-κB can be either pro-survival or anti-survival depending on cell types and conditions30, 31, inflammatory changes such as those induced by brain microglia have been found to inhibit neurogenesis32–38.

Metabolic physiological activities including feeding, body weight and glucose homeostasis are critically regulated by the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) which comprises the arcuate nucleus (ARC) and the ventral medial hypothalamic region (VMH). This regulation is primarily mediated by the balance between anorexigenic neurons expressing proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and orexigenic neurons expressing neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AGRP). In normal physiology, increased systemic levels of nutrients and related hormones can act in the hypothalamus to activate POMC neurons but inhibit NPY/AGRP neurons. As a result, appetite is suppressed and energy expenditure is enhanced to maintain body weight and metabolic balance. However, under obesity-prone environment like chronic HFD feeding condition, POMC neurons are significantly impaired, exhibiting reduced sensitivities to hormones such as insulin and leptin, leading to the onset of central insulin and leptin resistance, which has been appreciated as a critical neural mechanism for obesity and related type-2 diabetes (T2D)39–42. Research over the recent years have significantly appreciated the molecular pathways and cell types involved in hypothalamic leptin and insulin resistance39–42; however, these understandings were mainly based on the principle of non-replenishable populations of involved neurons. Most recently, it was shown that mice under chronic HFD feeding suffered from a loss of POMC neurons and also impaired hypothalamic neurogenesis19, 43. Here, our study demonstrates that adult htNSCs are multipotent and predominantly present in the mediobasal hypothalamus of adult-aged mice, but are markedly impaired in survival, proliferation and differentiation upon IKKβ/NF-κB activation to contribute to the neurodegenerative mechanism of obesity and related diabetes.

RESULTS

Enrichment, stemness and multi-potency of adult htNSCs

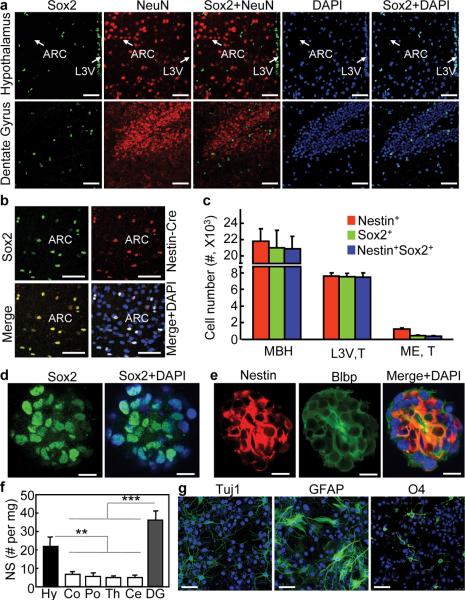

In this work, we aimed to investigate the entity and characteristics of htNSCs in adult-aged mice. Using immunostaining for Sox2, an authentic biomarker of NSCs established in the literature44, we found that Sox2-positive cells were enriched in the MBH and the adjacent third-ventricle wall of adult hypothalamus (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1). Indeed, various neuronal markers such as NeuN were undetectable in these cells (Fig. 1a). Other brain regions were also analyzed, showing that Sox2-positive cells were similarly found in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (Fig. 1a) and SVZ. In addition to Sox2, nestin has often been used in research to report neural stem cells and also neural progenitors and precursors45. Due to the poor quality of nestin immunostaining, we resorted to Nestin-Cre mice to report nestin activities based on nestin promoter-controlled Cre expression. Indeed, Sox2 significantly co-exists with nestin in adult htNSCs (Fig. 1b). We observed strong nestin activities in tanycytes located in the median eminence as well as the third-ventricle lateral walls, which was also recently reported in newborn pups or pre-adult young mice20. Interestingly, tanycytes in the median eminence had weak or absent Sox2 expression despite strong nestin expression in post-development, adult-aged mice (Supplementary Fig. S2). In contrast, htNSCs in the MBH expressed both Sox2 and nestin strongly (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S2); nonetheless, tanycytes in the upper portion of the third-ventricle lateral walls still shared this pattern (Supplementary Fig. S2). Because the MBH is much bigger, it contains more than10 times htNSCs compared to the median eminence, and ~3 times more compared to the third-ventricle lateral walls (Fig. 1c). By definition, NSCs are self-renewing, multipotent cells and can give rise to neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. We assessed if adult htNSCs possess these characteristics using in vitro neurosphere assay. Data revealed that hypothalami of adult mice produced in vitro neurospheres which expressed NSC biomarkers Sox2, nestin and Blbp (Fig. 1d,e), and this characteristic was maintained >15 generations of passages which we followed. The numbers of primary neurospheres obtained from the hypothalamus were nearly comparable to dentate gyrus (Fig. 1f). Also, we revealed that hypothalamic neurospheric cells at various passages can differentiate into neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (Fig. 1g). Altogether, Sox2/nestin co-expressing htNSCs with full NSC functions are enriched in the MBH and the third ventricle walls of adult mice at post-development ages, and thus, in addition to SVZ and SGZ, the hypothalamus is another critical adult NSC-containing brain region.

Figure 1.

In vivo and in vitro definition of htNSCs in adult mice.

(a–c) Brain sections across the ARC were made from C57BL/6 mice (a) or Nestin-Cre mice (b,c) for immunostaining. Brain sections across dentate gyrus were included in (a). Mice were on chow-fed and ~3-month-old males. Nuclear staining by DAPI (blue) revealed all cells in the sections. Merged images show the co-distribution of the indicated molecular markers. Chow-fed males at 3 months of age were used in these studies. (c) Numbers of Nestin+, Sox2+, or Nestin+Sox2+ cells in the MBH (comprising the ARC and VMH) were compared to numbers of tanycytes in lateral third-ventricle wall (L3V, T) vs. median eminence (ME, T). n = 6 mice (c). Scale bar = 50 μm (a,b).

(d,e) Hypothalamic tissues were sampled from normal C57BL/6 mice (chow-fed, 3 months old) for neurosphere culture as described in Method section. Neurospheres were formed and passaged in growth medium containing bFGF and EGF. Neurospheres at various passages were attached to slides and immunostained for Sox2 (d), nestin and Blbp (e). Images were merged with DAPI staining to reveal the nuclear distribution of Sox2 and the cytoplasmic distribution of nestin and Blbp. Scale bar = 50 μm.

(f) The hypothalamus and various other brain components were sampled from normal C57BL/6 mice (chow-fed, 3 months old) for the neurosphere (NS) assay. Data shows the total number of primary NS (without passage) normalized by the mass (mg) of brain tissue from which NS were derived. Hy: hypothalamus; Co: cortex; Po: pons; Th: thalamus; Ce: cerebellum; DG: dentate gyrus. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, n = 4 mice per group; error bars reflect means ± s.e.m.

(g) Neurospheres were derived from the hypothalamus of normal mice (chow-fed, 3 months old). Dissociated neurospheric cells at the same passage were induced to differentiate as described in the method. Following 7-day differentiation, cells were immunostained for neuronal marker Tuj1, astrocyte marker GFAP, and oligodendrocyte marker O4. Nuclear staining of DAPI revealed all cells in the slides. Scale bar = 50 μm.

In vivo neurogenesis of adult htNSCs leads to new MBH neurons

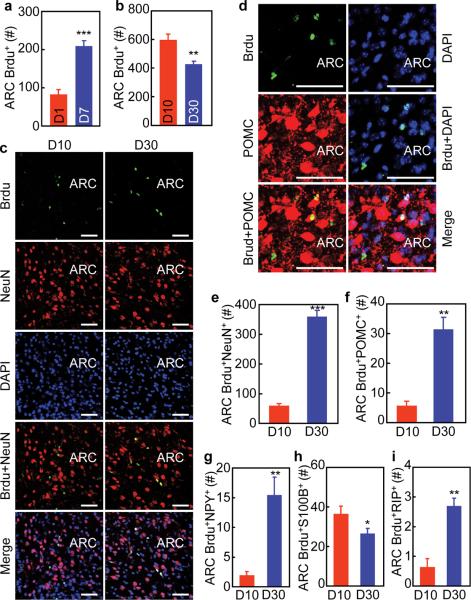

Subsequently, we employed 5-bromodeoxyuridine (Brdu) labeling to study if adult-onset htNSCs can lead to new neurons in post-development, adult-aged mice. Through pre-implanted icv cannula, normal adult C57BL/6 mice received a single-day Brdu injection for the proliferation analysis of Brdu-labeled cells. Data revealed that Brdu-labeled cells doubled at 7 days post labeling (Fig. 2a). To study the survival rates of Brdu-labeled cells, we employed daily icv Brdu injections for 7 consecutive days. By comparing the numbers of Brdu-labeled cells at Day 10 vs. 30, we found that survival rate of these cells during 30 days was about 70% (Fig. 2b). During this period, a fraction of these Brdu-labeled cells differentiated into neurons (Fig. 2c). Using immunostaining for MBH neuropeptides including POMC (Fig. 2d) and NPY, we found that among the newly-generated neurons (Fig. 2e), 8% of them were POMC neurons (Fig. 2f), and 4% were NPY neurons (Fig. 2g). A small number of Brdu-labeled cells differentiated into S100B-expressing astrocytes at Day 10, and these astrocytes seemed to undergo a turnover process since the total number dropped by 30% at Day 30 (Fig. 2h). In addition, a few Brdu-labeled RIP-expressing oligodendrocytes were detected (Fig. 2i). Overall, compared to the whole population of mature neural cells in the ARC, the numbers of new neural cells generated via adult htNSCs-directed neurogenesis revealed by Brdu labeling was rather small. On the other hand, these small increments suggest that htNSCs use a very slow speed to mediate neurogenesis including neuronal generation in mice at post-development adult ages.

Figure 2.

Brdu tracking of adult htNSCs-mediated neurogenesis in mice.

(a) C57BL/6 mice (chow-fed males, 4 months old) received a single-day icv injection of Brdu. Brains were fixed at Day 1 vs. 7 and sectioned for Brdu staining. Total numbers of Brdu-labeled cells in serial ARC sections were counted.

(b–i) C57BL/6 mice (chow-fed males, 4 months old) received daily icv injections of Brdu consecutively for 7 days. Brains were fixed at Day 10 vs. 30 and then sectioned for Brdu staining (b) or co-immunostaining with indicated markers (c–i). (b) Total numbers of Brdu-labeled cells in serial ARC sections were counted. (e–i) Total numbers of Brdu-labeled cells co-immunostained with NeuN (e), POMC (f), NPY (g), S100B (h), and RIP (i) in serial ARC sections were counted.

** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, n = 6 mice (a,b,g,i), n = 4 mice (e,h) and n = 5 mice (f) per group. Error bars reflect means ± s.e.m. Scale bar = 50 μm (c,d).

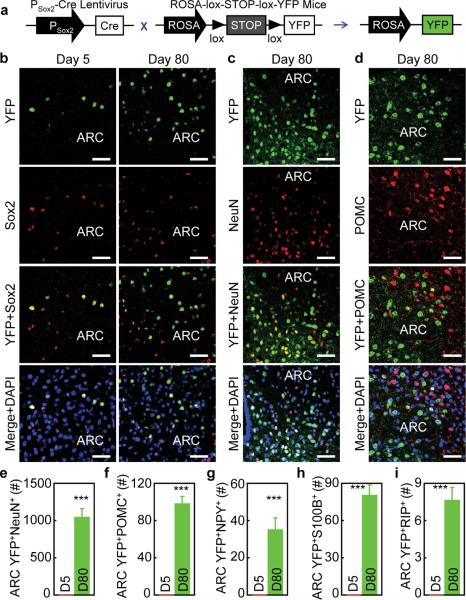

In vivo neurogenesis of adult htNSCs is slow in physiology

In addition to Brdu labeling, we developed an alternative approach by which we permanently labeled htNSCs with fluorescent YFP for long-term fate mapping. Briefly, we delivered Sox2 promoter-directed lentiviral Cre vs. control lentivirus to the MBH of ROSA-lox-STOP-lox-YFP mice. Cre-dependent removal of lox-STOP-lox cassette enables ROSA promoter to induce YFP in Sox2-expressing htNSCs in the MBH (Fig. 3a). Using this tracking system, we confirmed that YFP was expressed in Sox2-positive htNSCs at Day 5 post lentiviral Cre delivery (Fig. 3b). At this time point, none of the YFP-expressing cells expressed neuronal marker NeuN. However, over an 80-day follow-up, the MBH of mice clearly showed increased numbers of YFP-labeled cells (Fig. 3b), and a significant pool of these YFP-labeled cells were neurons (Fig. 3c). Using neuropeptide immunostaining for POMC (Fig. 3d) and NPY, we detected ~1000 new neurons generated in the ARC at Day 80 (Fig. 3e) – which account for 6% of neuronal population in this region, and 10% of new neurons belonged to POMC neurons (Fig. 3f) and 3% belonged to NPY neurons (Fig. 3g). Also, we detected some YFP-positive S100B-expressing astrocytes (Fig. 3h) and a few YFP-positive RIP-expressing oligodendrocytes (Fig. 3i). Therefore, compared to the short-term Brdu tracking, neuronal differentiation revealed by long-term YFP tracking was more appreciable. By comparing these two neurogenic tracking methods, it can be further deduced that neuronal differentiation by adult htNSCs is rather slow in normal physiology. Taken together, htNSCs slowly and cumulatively lead to significant numbers of new MBH neural cells including neurons in post-development adult mice under physiological conditions.

Figure 3.

Fate mapping of adult htNSCs in mice under normal physiology.

ROSA-lox-STOP-lox-YFP mice (chow-fed males, 3 months old) were bilaterally injected in the mediobasal hypothalamus with lentiviruses which directed Cre expression under the control of Sox2 promoter. Following indicated days post viral injection, hypothalamus sections were made for tracking neural differentiation of YFP-labeled cells.

(a) Schematic of lentiviral vector and genetic mouse model. Lentivirus expressing Cre under the control of Sox2 promoter was termed Psox2-Cre lentivirus. The control was a lentiviral vector without containing Cre (schematic not shown).

(b–i) Co-imaging of YFP (green) (b–d) with immunostaining (red) of Sox2 (b), NeuN (c) or POMC (d) at indicated days post viral injection. Cell nuclear staining (blue) by DAPI revealed all cells in the sections. Bar graphs: YFP-labeled NeuN-positive cells (YFP+NeuN+) (e); POMC-positive cells (YFP+POMC+) (f); NPY-positive cells (YFP+NPY+) (g); S100B-positive cells (YFP+S100B+) (h) and RIP-Positive cells (YFP+RIP+) (i) in serial ARC sections were counted.

*** P < 0.001, n = 5 mice (e,f), n = 6 mice (g,i) and n = 4 mice (h) per group. Error bars reflect means ± s.e.m. Scale bar = 50 μm (b–d).

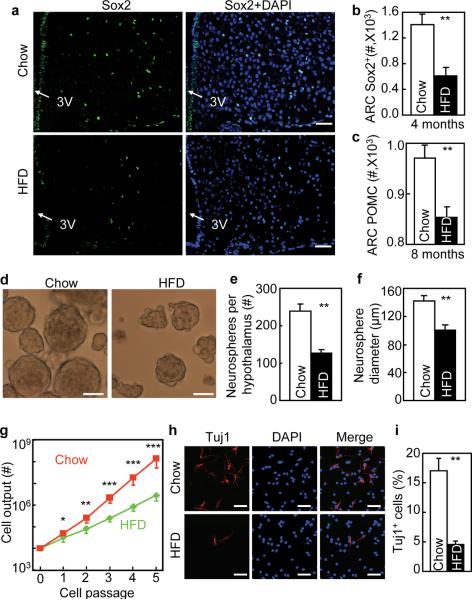

Long-term HFD feeding impairs survival and neurogenesis of adult htNSCs

To investigate the disease relevance of htNSCs, we focused on HFD-induced obesity and pre-diabetes. Using Brdu labeling, we found that compared to chow-fed mice, mice with long-term (4-month) HFD feeding had much fewer Brdu-labeled cells in the MBH (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Also, these HFD-fed mice suffered from severe decreases in proliferation and survival rates of Brdu-labeled cells (Supplementary Fig. S3b,c). Using co-immunostaining with NeuN or neuropeptides, we found that Brdu-labeled cells in HFD-fed mice showed impaired differentiation into neurons including POMC and NPY neurons (Supplementary Fig. S3d–f), astrocytes (Supplementary Fig. S3g) and oligodendrocytes (Supplementary Fig. S3h). Compared to neuronal reduction, glial cell reduction was less severe, leading to an increased ratio of glia to neurons in HFD-fed mice. In addition to Brdu labeling, we further employed Sox2 immunostaining and found that Sox2-positive cells were scarce in the MBH of HFD-fed mice (Fig. 4a,b). Based on these findings, we predicted that impaired hypothalamic neurogenesis by HFD feeding could result in a reduction in certain types of neurons over an extra-long HFD feeding period. Indeed, following an 8-month HFD feeding, POMC neurons in the ARC reduced by ~12% compared to chow-fed mice (Fig. 4c). This finding was in line with observations reported in the recent literature19, 43. Using in vitro neurosphere assay, we observed that neurospheres derived from the hypothalamus of HFD-fed mice were not only fewer but also smaller than that derived from chow-fed mice (Fig. 4d–f). In vitro proliferation rate analysis showed that htNSCs derived from HFD-fed mice proliferated poorly (Fig. 4g). In vitro differentiation analysis further revealed that htNSCs derived from HFD-fed mice showed a striking impairment in neuronal differentiation (Fig. 4h,i). Cultured NSCs isolated from the SVZ and SGZ of these HFD-fed mice were also impaired in terms of proliferation and neuronal differentiation, but the impairments were less severe compared to the changes in htNSCs (Supplementary Fig. S4a–c).Taken together, chronic HFD feeding causes neurogenic impairment in the mediobasal hypothalamus.

Figure 4.

Impaired survival and neurogenesis of htNSCs derived from mice dietary obesity.

(a–c) Adult male C57BL/6 mice were maintained under chow vs. HFD feeding for 4 months (a,b) or 8 months (c). Hypothalamic sections were immunostained for Sox2 (a) or POMC (image not shown). DAPI nuclear staining revealed all cells in the section. Sox2-immunoreactive (Sox2+) cells (b) and POMC neurons (c) were counted in the arcuate nucleus (ARC).

(d–i) C57BL/6 mice were maintained under normal chow vs. HFD feeding for 4 months (4M), and the hypothalami of these mice were removed to generate neurospheres for in vitro assays.

(d–f) Morphology (d), number (e), and size (f) of primary neurospheres. (g) Primary neurospheres were passaged with the same initial number (104 cells per group), and cell outputs were followed for 5 passages. (h,i) Neurospheric cells at the same passage (representing Passages 5–10) were induced to differentiate for 7 days, cells were fixed and immunostained for Tuj1 (h), and Tuj1-positive (Tuj1+) cells were counted in the slides (i).

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, comparisons between chow and HFD at indicated points, n = 5 mice (b), n = 6 mice (c) and n = 4 mice (e,f) per group, and n = 4 per group (g,i); error bars reflect means ± s.e.m. Scale bar = 50 μm (a,d,h).

Adult htNSCs are vulnerable to micro-environmental inflammation

In our studies, we noted that obese mice-derived htNSCs displayed impaired proliferation and differentiation even after being passaged to subsequent generations. In exploring the underlying basis, we found that excessive cytokines TNFα and IL-1β were produced in the medium of obese mice-derived htNSCs over culture passages (Supplementary Fig. S5a,b). Because cytokines TNFα and IL-1β are produced by NF-κB activation and also known to potently activate IKKβ/NF-κB, a positive feed-forward loop consisting of TNFα/IL-1β and IKKβ/NF-κB may work as a molecular basis for the trans-generational defects in these cells. To test this idea, we co-inhibited gene expression of TNFα and IL-1β in obese mice-derived htNSCs via siRNAs (Supplementary Fig. S5c), and then examined proliferation and differentiation of these cells. Brdu pulse labeling revealed that TNFα and IL-1β co-inhibition improved the proliferation of these htNSCs (Supplementary Fig. S5d,e). In addition, neuronal differentiation of these cells was markedly increased by the co-inhibition of TNFα and IL-1β (Supplementary Fig. S5f,g). In this context, we directly measured NF-κB signaling, and found that NF-κB activation was up-regulated in obese mice-derived htNSCs (Fig. 5a). We then aimed to test if hypothalamic inflammation is important for HFD feeding-induced defects of htNSCs, given that we also observed that HFD feeding increased MBH microglia cell numbers and TNFα production in these cells (Supplementary Fig. S6A). To test this hypothesis, we inhibited IKKβ/NF-κB in microglia using microglia-specific IKKβ gene ablation. Briefly, IKKβlox/lox mice received MBH injection of microglia-specific (CD11b promoter-driven) lentiviral Cre. We confirmed that HFD feeding-induced microglial TNFα expression decreased in these Cre-delivered mice but not the control mice (Supplementary Fig. S6b). Subsequently, htNSCs from these mice were isolated for in vitro analyses, showing that HFD feeding-impaired htNSC proliferation and differentiation were significantly attenuated in htNSCs isolated from Cre-delivered mice (Supplementary Fig. S6c–e). Hence, adult htNSCs are vulnerable to inflammation, and hypothalamic microglia are involved in this inflammatory mechanism.

Figure 5.

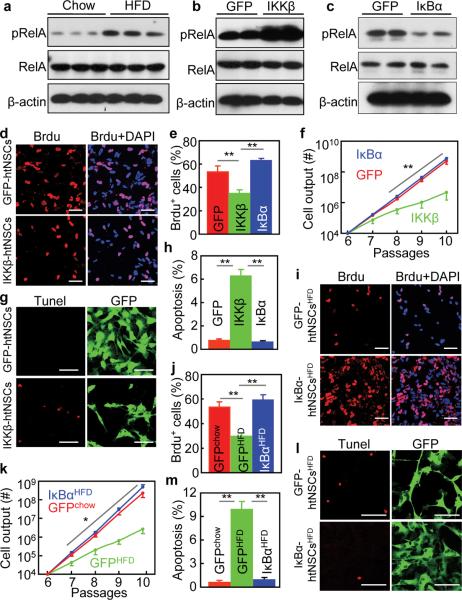

Impaired in vitro proliferation of htNSCs with IKKβ/NF-κB activation. (a) Adult C57BL/6 mice were fed on a chow vs. HFD for 4 months. Hypothalamic neurospheres were generated from these mice, cultured and passaged in vitro. Western blotting was performed for cultured neurospheric cells to measure phosphorylated RelA (pRelA). RelA and β-actin were analyzed as controls.

(b,c) Neurospheres were derived from the hypothalamus of chow-fed C57BL/6 mice (3 months old). Dissociated neurospheric were infected with lentiviruses expressing CAIKKβ (GFP-conjugated), DNIκBα (GFP-conjugated), and GFP. In vitro models of htNSCs with stable transduction of GFP, CAIKKβ and DNIκBα were established and maintained in the selection medium, named GFP-htNSCs, IKKβ-htNSCs and IκBα-htNSCs (Suppl. Fig. 7), respectively. Cells were analyzed via Western blots for pRelA. Total protein levels of RelA and β-actin were analyzed as controls.

(d–h) Dissociated IKKβ-htNSCs, IκBα-htNSCs, and GFP-htNSCs were maintained in the growth medium. (d,e) Cells (Passage 6) were labeled with Brdu and analyzed for Brdu-positive (Brdu+) cells. (f) Cell outputs over subsequent 4 passages were analyzed. (g,h) Cells (Passage 6) were subjected to Tunel staining, and Tunel staining-positive cells were counted.

(i–m) Neurospheres derived from the hypothalamus of C57BL/6 mice that received a normal chow vs. HFD for 4 months. Dissociated neurospheric cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing DNIκBα (GFP-conjugated) or GFP to establish IκBα-htNSCsHFD, GFP-htNSCsHFD, and GFP-htNSCschow lines. Dissociated cells with the same initial cell numbers from Passage 6 were maintained in the growth medium. (i,j) Cells (Passage 6) were pulse labeled with Brdu, and Brdu-positive (Brdu+) cells were analyzed. (k) Cell outputs from the same initial number at Passage 6 were followed for 4 passages. (l,m) Tunel assay was performed for cells (Passage 6, Day 2) and analyzed using Tunel staining.

(b,c,e,f,h) IKKβ: IKKβ-htNSCs; IκBα: IκBα-htNSCs; GFP: GFP-htNSCs

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, n = 4 (e,f,h,k), n = 5 (j) and n = 6 (m) per group. Error bars reflect means ± s.e.m. Statistics in (f,k): data points in red or blue lines were compared to the corresponding points in green line. Scale bar = 50 μm (d,g,i,l).

IKKβ/NF-κB inhibits survival and proliferation of htNSCs via apoptosis

Given the significant relevance of IKKβ/NF-κB in htNSCs, we decided to directly study if and how IKKβ/NF-κB activation or inhibition affected adult htNSCs. To facilitate this study, we established stable cell lines of htNSCs with genetically-induced IKKβ/NF-κB activation or inhibition. Using a lentiviral system to transfer cDNA into the genome of infected cells (Supplementary Fig. S7a), normal mice-derived htNSCs were stably transduced with the cDNA of constitutively-active IKKβ (GFP-conjugated) to activate NF-κB, termed IKKβ-htNSCs. In parallel, htNSCs with stable transduction of cDNA encoding dominant-negative IκBα (GFP-conjugated) to inhibit NF-κB were generated, termed IκBα-htNSCs. Control htNSCs cell lines were stably transduced with GFP cDNA, termed GFP-htNSCs. Using antibiotic selection, lentivirus-transduced htNSCs survived and were passaged in blasticidin-containing medium, as verified by the presence of GFP in individual cells over serial passages (Supplementary Fig. S7b–d). Using co-immunostaining, we verified that all these engineered htNSCs stably co-expressed all NSC markers Sox2, nestin, Musashi-1, and Blbp throughout many passages that we monitored (Supplementary Fig. S7b–d). Western blots confirmed that NF-κB activities increased in IKKβ-htNSCs (Fig. 5b) and decreased in IκBα-htNSCs (Fig. 5c). These cells were subjected to Brdu pulse labeling for proliferation assay. As shown in Fig. 5d–e, the proliferation of IKKβ-htNSCs significantly reduced compared to the control cells. We further analyzed the total cell numbers over 4 passages, showing that the total proliferation output of IKKβ-htNSCs was only ~1% of the control (Fig. 5f). We then used Tunnel assay to assess whether the growth defect in IKKβ-htNSCs was the result of enhanced apoptosis. Data showed that compared to control cells, there was a ~9-fold induction of apoptosis in IKKβ-htNSCs (Fig. 5g,h). At the same time, IκBα-htNSCs were analyzed for proliferation and apoptosis. We found that the proliferation rates of IκBα-htNSCs and control cells were comparable (Fig. 5e,f), consistent with the observation that both groups barely had apoptosis (Fig. 5h). Furthermore, to explore the molecular basis which underlies the apoptosis of IKKβ-htNSCs, we analyzed a battery of apoptotic and anti-apoptotic genes which are known as NF-κB target genes. Data revealed that apoptotic genes Bim, Bax, BNIP3 and caspase-3 were up-regulated in IKKβ-htNSCs while down-regulated in IκBα-htNSCs (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Upregulation of anti-apoptotic genes Bcl-2, Bcl-xl and Traf-2 by IKKβ/NF-κB was also observed, but these changes were relatively modest. Therefore, IKKβ/NF-κB over-activation uses the apoptotic program to significantly reduce the survival of adult htNSCs.

We next studied if IKKβ/NF-κB mediates the proliferation defect in obese mice-derived htNSCs. To do this, htNSCs derived from mice with HFD-induced obesity were stably transduced with dominant-negative IκBα vs. GFP, termed IκBα-htNSCsHFD and GFP-htNSCsHFD, respectively. To provide a normal reference, chow-fed mice-derived htNSCs were stably tranduced with GFP, termed GFP-htNSCschow. Brdu pulse labeling verified that GFP-htNSCsHFD proliferated poorly with only a small number of Brdu-positive cells (Fig. 5i,j). Strikingly, we found that IκBα-htNSCsHFD proliferated as normally as did the reference control (Fig. 5i,j). Furthermore, proliferation outputs over 4 passages revealed that while GFP-htNSCsHFD displayed severe proliferative defect, IκBα-htNSCsHFD had normal proliferation as GFP-htNSCschow (Fig. 5k). Tunnel assay was also performed to assess apoptosis of these cells, showing that apoptosis was evident in GFP-htNSCsHFD, but rarely seen in IκBα-htNSCsHFD which was similar to the normal reference GFP-htNSCschow (Fig. 5l,m). In sum, IKKβ/NF-κB mediates the proliferation defect in obese mice-derived htNSCs.

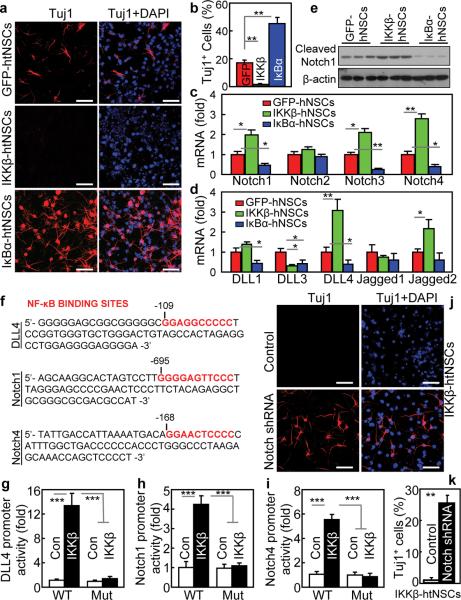

IKKβ/NF-κB inhibits neuronal differentiation of htNSCs via Notch signaling

IKKβ-htNSCs, IκBα-htNSCs and control GFP-htNSCs were subjected to neuronal differentiation analysis. GFP-htNSCs revealed ~17% of neuronal differentiation (Fig. 6a,b). However, neuronal differentiation completely stopped in IKKβ-htNSCs, as we barely detected neuronal morphology or neuronal marker in these cells (Fig. 6a,b). This change recapitulated the defect of neuronal differentiation in obese mice-derived htNSCs shown in Fig. 4h–i. Conversely, IκBα-htNSCs showed a pronounced increase in neuronal differentiation, which was even higher by 3 folds compared to GFP-htNSCs (Fig. 6a,b). We next explored how IKKβ/NF-κB affected neuronal differentiation of htNSCs. Through gene expression profiling, we found that mRNA levels for Notch isoforms including Notch1, 3 and 4 increased upon IKKβ/NF-κB activation but decreased upon IKKβ/NF-κB inhibition (Fig. 6c). Gene expression of Notch ligands including delta-like ligand-1 (DLL1), DLL4, and Jagged2 were similarly affected by IKKβ/NF-κB (Fig. 6d). Notch signaling, reflected by Notch protein cleavage, was upregulated by IKKβ/NF-κB activation but downregulated by NF-κB inhibition (Fig. 6e). To further examine the relationship between IKKβ/NF-κB and Notch signaling, we examined the promoter regions of genes that encode Notch signaling components, and found that the canonical NF-κB DNA-binding motif 5-GGRRNNYYCC-3 exists in the promoters of DLL4, Notch1 and Notch4 genes (Fig. 6f). Thus, we tested if IKKβ/NF-κB can control the promoter activities of these genes. To do this, we created luciferase plasmids controlled by each of these promoters, and found that IKKβ/NF-κB increased the transcriptional activities of these promoters when transfected in HEK293 cells (Fig. 6g–i). On the other hand, mutagenesis of NF-κB DNA-binding motif abrogated the effect of IKKβ/NF-κB in activating the transcriptional activities of these promoters (Fig. 6g–i). To further test the IKKβ/NF-κB-Notch connection in htNSCs, we ablated Notch genes using co-transduction of lentiviral shRNA against individual Notch isoform (Supplementary Fig. S8b–e). Notch inhibition completely reversed the differentiation defect in IKKβ-htNSCs (Fig. 6j,k). Notch inhibition also promoted neuronal differentiation in GFP-htNSCs (data not shown), which is similar to the effect of IKKβ/NF-κB inhibition as displayed in IκBα-htNSCs (Fig. 6a,b). Altogether, IKKβ/NF-κB employs Notch signaling to inhibit the neuronal differentiation of htNSCs. In this context, we employed IκBα-htNSCsHFD, GFP-htNSCsHFD, and GFP-htNSCschow (Fig. 5i–m) to assess if IKKβ/NF-κB inhibition can reverse the neuronal differentiation defect in obese mice-derived htNSCs. Data revealed that neuronal differentiation was impaired in GFP-htNSCsHFD, but was substantially improved in IκBα-htNSCsHFD (Fig. 7a,b). In parallel, we tested if Notch inhibition could similarly improve neuronal differentiation of obese mice-derived htNSCs, as indeed these cells showed upregulation of Notch signaling (Fig. 7c). We ablated Notch isoforms in these cells by co-infection with lentivrial shRNAs against Notch1–4, as similarly used for Fig. 6j–k. With Notch inhibition, GFP-htNSCsHFD displayed enhanced neuronal differentiation (Fig. 7d,e). In sum, neuronal differentiation defect in obese mice-derived htNSCs can be reversed by inhibition of NF-κB or downstream Notch signaling.

Figure 6.

In vitro effect of IKKβ/NF-κB activation on neuronal differentiation of htNSCs.

(a–e) Dissociated IKKβ-htNSCs, IκBα-htNSCs and GFP-htNSCs from Passage 6 were induced to differentiate. (a,b) Immunostaining of neuronal marker Tuj1. (b) The percentage of Tuj1-positive (Tuj1+) cells. IKKβ: IKKβ-htNSCs; IκBα: IκBα-htNSCs; GFP: GFP-htNSCs. (c,d) mRNA levels of genes encoding Notch isoforms (c) and Notch ligands (d). (e) Analysis of Notch signaling via Western blot measurement of cleaved Notch1 protein.

(f–i) NF-κB controls genes that encode Notch signaling proteins. (f) NF-κB DNA-binding motif in the promoter regions of murine DLL4, Notch1 and Notch4 genes. (g–i) Gene promoter activities of wildtype (WT) vs. mutant (Mut) murine DLL4 (g), Notch1 (h) and Notch4 (i) in HEK293 cells in presence or absence of IKKβ/NF-κB activation, induced by transfection of pcDNA expressing constitutively-active IKKβ or a control (Con).

(j,k) IKKβ-htNSCs were co-infected with lentiviral shRNAs against Notch1–4, as evaluated in Suppl. Fig. 8. Cells were induced to differentiate and analyzed for neuronal marker Tuj1 via immunostaining (j) and quantitatively analyzed for Tuj1-positive (Tuj1+) cells (k).

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, n = 4 (b,c,d,g,h,i) and n = 6 (k) per group; error bars reflect means ± s.e.m. Scale bar = 50 μm (a,j).

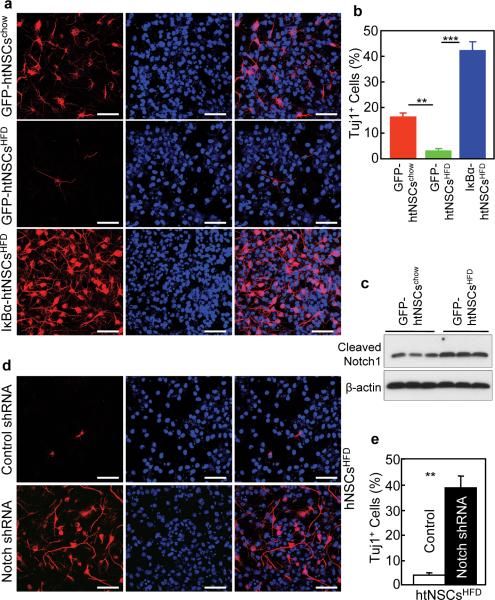

Figure 7.

Effect of NF-κB inhibition on differentiation of obese mice-derived htNSCs.

(a,b) Dissociated IκBα-htNSCsHFD, GFP-htNSCsHFD and GFP-htNSCschow (established in Supplementary Fig. S7) at Passage 6 were induced to differentiate. Cells were then immunostained for neuronal marker Tuj1. (b) Percentage of Tuj1-positive (Tuj1+) cells.

(c) Western blotting of cleaved Notch1. β-Actin (β-Act) was used to provide an internal control.

(d,e) GFP-htNSCsHFD expressing lentiviral Notch1–4 shRNAs vs. control shRNA were induced to differentiate for 7 days. Cells were then fixed and analyzed for Tuj1 Immunostaining (d). (e) Percentage of Tuj1-positive (Tuj1+) cells.

** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, n = 4 per group (b,e); error bars reflect means ± s.e.m. Scale bar = 50 μm (a,c,d).

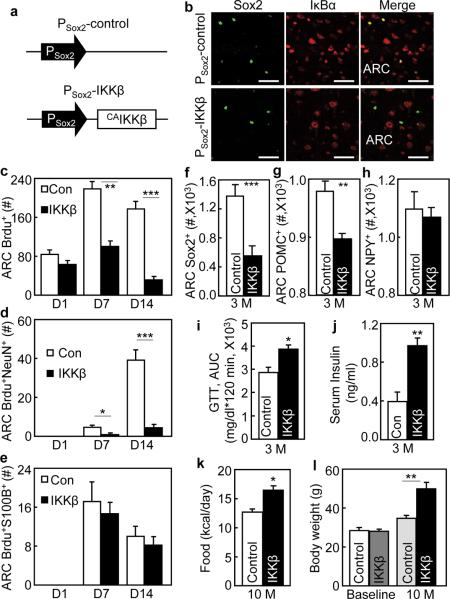

IKKβ/NF-κB in htNSCs mediates obesity and pre-diabetes in adult mice

To explore if IKKβ/NF-κB in htNSCs is important for disease, we developed a mouse model with IKKβ/NF-κB gain-of-function in MBH htNSCs of adult mice. These mice were obtained through MBH injection of Sox2 promoter-driven lentiviruses expressing constitutively-active IKKβ (Fig. 8a). We assessed IκBα degradation via immunostaining to report IKKβ/NF-κB activation in htNSCs of these mice. Indeed, IκBα degradation occurred in Sox2-positive cells but not other cells in the ARC of IKKβ-injected mice (Fig. 8b). Contrasting to the control group, proliferation and survival of Brdu-labeled cells over a 14-day tracking period were poor in IKKβ-injected mice (Fig. 8c), and Brdu-labeled cells in IKKβ-injected mice showed impaired neuronal differentiation (Fig. 8d). Interestingly, over this 14-day period, IKKβ did not result in a significant number in S100B-expressing astrocytes (Fig. 8e). Over a 3-month tracking period, Sox2-positive htNSCs reduced 60% in IKKβ-injected mice compared to the control mice (Fig. 8f). As a result, the total number of POMC neurons in the ARC of IKKβ-injected mice reduced by ~10% (Fig. 8g). NPY neurons in the ARC were not significantly affected over this 3-month period (Fig. 8h). In physiological studies, we maintained IKKβ-injected mice and the controls under normal chow feeding and monitored their glucose and insulin levels as well as food intake and body weight profiles. As shown in Fig. 8i–j, IKKβ-injected mice manifested glucose intolerance and hyperinsulinemia at ~3 months post gene delivery. These mice also displayed overeating and weight gain, and these effects cumulatively resulted in the onset of severe obesity at ~10 months post gene delivery despite normal chow feeding (Fig. 8k,l). The findings here explicitly demonstrated that IKKβ/NF-κB over-activation mediates the effect of chronic HFD feeding in impairing htNSCs-directed neurogenesis to cause obesity and prediabetic disorders.

Figure 8.

Mouse model of htNSCs-specific IKKβ activation and metabolic phenotypes.

C57BL/6 mice (3-month-old, chow-fed males) bilaterally received intra-MBH injections of PSox2-CA IKKβ vs. PSox2-control lentiviruses. All mice were maintained under normal chow feeding throughout experiments.

(a,b) Schematic of lentiviral vector that expressed CAIKKβ under the control of Sox2 promoter (PSox2-CA IKKβ). The same vector with the removal of CAIKKβ was used as the matched control (PSox2-control). (b) Hypothalamic sections were prepared from mice at 2 weeks post injection and co-immunostained for Sox2 (green) and IκBα (red).

(c–e) Mice with PSox2-CAIKKβ vs. PSox2-control received a single-day icv injection of Brdu. Brains were fixed at Day 1, 7 or 14 post Brdu injection. Brain sections across the ARC were processed with Brdu staining or co-immunostaining with NeuN or S100B, and analyzed for total Brdu-labeled cells (c) and Brdu-labeled cells positive for NeuN (d) or S100B (e).

(f–h) Brain sections across the ARC were prepared from mice at ~3 months (3 M) post lentiviral injection, subjected to Sox2 and POMC immunostaining, and counted for Sox2-positive cells (f), POMC neurons (g) and NPY neurons (h) in serial ARC sections.

(i–l) Data show glucose tolerance (i) and fasting insulin levels (j) of mice at 3 M post lentiviral injection, and food intake (k) and body weight (l) of mice at 10 months (10 M) post lentiviral injections. Baseline body weight levels of mice prior to lentiviral injections were also included in (l). GTT: glucose tolerance test.

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, n = 6 mice (c), n = 5 mice (c,e) and n = 4 mice (f,g,h) per group; n = 6 mice per group (d,i,j,k) and n = 10 mice per group (l). Error bars reflect means ± s.e.m. Scale bar = 50 μm (b).

DISCUSSION

Adult htNSCs are multipotent but vulnerable to inflammation

The existence of adult NSCs in the brain was not a well accepted notion until recently, and to date, research on adult NSCs has been mainly based on SVZ and SGZ in the brain1–15. Recently, several studies have reported the observations of postnatal hypothalamic neurogenesis in mice16–19. Of note, in a recent study by Lee et al20, it was reported that median eminence tanycytes led to newborn neurons in mouse pups at ages of P10 to P19, an observation which was based on Brdu labeling and nestin-based fate mapping. Further, these authors showed that tanycyte-directed neuronal generation can be enhanced by a short-term (30-day) HFD feeding starting at either a pre-weaning (P15) or a pre-adult (P45) age20. In our research, we focused on studying if the hypothalamus crucially contains adult NSCs at post-development and adult-aged mice, and if so, whether they are important for physiology or diseases. Using Sox2 which is known as an authentic NSC marker44, we found that Sox2-expressing htNSCs are enriched in the MBH and surrounding third-ventricle ependyma. These htNSCs can be isolated and maintained in vitro in the form of neurospheres for >15 generations, and dissociated neurospheric cells at any generation express NSC/progenitor biomarkers, and can differentiate into neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Our findings are in line with all the recent literature which reported the observations of postnatal hypothalamic neurogenesis16–20. Therefore, these Sox2-expressing adult cells are a bona fide population of htNSCs. Interestingly, in contrast to the findings by Lee et al, our data showed that tanycytes constitute only a small fraction of htNSCs, while majority of htNSCs exist in the MBH in post-development adult-aged mice. This difference may reflect a developmental dynamic of htNSCs. In our research, we further examined the effect of chronic HFD feeding on htNSCs. Differing from the short-term HFD feeding which was reported to promote hypothalamic neurogenesis in pre-adult ages20, we found that long-term (4-month) HFD feeding remarkably depleted htNSCs and also severely impaired their neuronal differentiation, as assessed using both in vivo and in vitro paradigms. We postulate that while neurogenic upregulation by short-term HFD feeding may represent a compensatory reaction, long-term HFD feeding is detrimental for the cell fate of adult htNSCs. As we further uncovered, the neurodegenerative actions of chronic HFD feeding are attributed to IKKβ/NF-κB over-activation which involves the inflammatory paracrine actions of microglia. In sum, the findings in this research can provide conclusive in vivo and in vitro evidences showing the critical existence of multipotent adult htNSCs, and also reveal that these cells are vulnerable to hypothalamic inflammation induced by chronic HFD feeding.

IKKβ/NF-κB Impairs survival and differentiation of adult htNSCs

Given the significant link between hypothalamic inflammation and htNSCs, we comparatively examined IKKβ/NF-κB in htNSCs derived from normal vs. obese animals. It was uncovered that IKKβ/NF-κB is over-activated in obese mice-derived htNSCs. IKKβ/NF-κB activation in obese mice-derived htNSCs was transferable over generations, and the underlying basis was revealed to be attributed to the paracrine release of cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β – both of which are not only two classical IKKβ/NF-κB products but also potent inducers of IKKβ/NF-κB activation. Indeed, inhibition of both cytokines blocked the paracrine activation loop of IKKβ/NF-κB to improve the proliferation and neuronal differentiation of obese mice-derived htNSCs. To better decipher the role of IKKβ/NF-κB in the cell biology of htNSCs, we developed in vitro models of htNSCs with genetically-induced IKKβ/NF-κB activation or inhibition. Using cell output and Brdu labeling analyses, we found that that survival and proliferation of htNSCs were reduced by IKKβ/NF-κB activation but improved by IKKβ/NF-κB inhibition, and both effects were remarkable. In-depth analyses revealed that IKKβ/NF-κB activation upregulates apoptotic genes to cause apoptosis of htNSCs, and these defects are reversible by IKKβ/NF-κB inhibition. In parallel, we importantly discovered that IKKβ/NF-κB strongly suppresses neural differentiation of htNSCs, and identified that upregulation of Notch signaling by IKKβ/NF-κB is responsible. These findings align with recent literature showing that Notch signaling counteracts NF-κB in various other cell types46–49, and also support the literature reports that Notch signaling inhibits neuronal differentiation and neurogenesis of NSCs50–56. Thus, IKKβ/NF-κB negatively affects the survival and neurogenesis of adult htNSCs via apoptotic and Notch molecular programs.

Adult neurogenesis via htNSCs is important for physiology and disease

Adult NSCs belong to a small population of cells with slow dividing rate in the brain, and because of this nature, the biological characteristics and physiological functions of these cells are still limitedly appreciated. In this work, using two in vivo tracking approaches, we found that adult htNSCs contribute to the generation of new MBH neurons in normal mice at post-development ages. Indeed, the neurogenic activities of adult htNSCs are slow and thus modest during short-term periods, as revealed by Brdu-based pharmacological approach. With genetic YFP labeling, htNSCs-induced neuronal generation over a long period was more evidently visible. Strikingly, chronic HFD feeding can dramatically deplete htNSCs and inhibit neuronal differentiation of these cells in the MBH of adult mice. Compared to the entire population of mature neurons, the fraction of neuronal loss due to htNSC defects is relatively modest and does not affect the vitality of animals in general. However, for certain types of neurons such as POMC neurons which have rather small population numbers by nature, even a modest loss can have major impacts on physiology. In this context, we studied if adult htNSCs are important for physiology using mice with adult-onset htNSCs ablation induced via IKKβ/NF-κB activation in the MBH. We found that these mice developed overeating, glucose disorder, insulin resistance and obesity. The collective development of these metabolic diseases was associated with a fractional loss of neurons including POMC neurons. These findings, while aligning with the critical role of POMC neurons in metabolic regulation, indicate that adult htNSCs-directed neurogenesis is required for central regulation of physiology. These metabolic derangements induced by htNSCs-specific IKKβ/NF-κB activation, to certain extent, contribute to the disease outcomes of chronic HFD feeding – which indeed similarly inhibits the survival and neurogenesis of adult htNSCs. Supportively, recent research reported that chronic HFD feeding leads to a loss of POMC neurons in the MBH43, a phenomenon which we similarly observed in this work. Altogether, dietary obesity represents a mild version of neurodegenerative disease, and neural regeneration can be a basis for developing new strategies to counteract obesity and related co-morbidities.

METHODS

Animals, biochemical treatments and phenotyping

C57BL/6 mice, Nestin-Cre mice, and ROSA-lox-STOP-lox-YFP mice were from Jackson Laboratory. IKKβlox/lox mice were used in our previous research27, 28 and maintained under standard conditions. All mice in this study are males. High-fat diet was obtained from Research Diets, Inc. Body weight of individually housed mice was measured twice a week and food intake was recorded daily. For GTT, overnight fasted mice were injected with glucose (2 g kg−1 body weight) intraperitoneally, and blood glucose levels at various time points were measured using a Glucometer Elite (Bayer, Elkhart, IN). Fasting insulin levels were measured using ELISA kits (Linco). Brdu labeling: mice were pre-implanted with cannula into the lateral ventricle, and after surgical recovery, they received single-day icv injections of 10 μg Brdu (Sigma) for proliferation rate analysis or daily icv injections of 10 μg Brdu consecutively for 7 days for survival rate analysis. Mice were perfused with 4% PFA at indicated days post injections, and brains were removed, post-fixed and sectioned for Brdu staining. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Lentiviruses and MBH injections

Using Sox2 promoter-controlled lentiviral system44 (provided by F. Gage), Sox2 promoter-controlled lentiviral vectors were created to direct the expression of Cre, CAIKKβ, or control GFP. Cre (GFP-conjugated) were constructed to lentiviral vector controlled by CD11b promoter (provided by Dr. D. Hickstein). Lentiviruses were produced by co-transfecting viral expression vectors with the package plasmids into HEK 293 FT cells, as described previously22, 57. Bilateral injections of mediobasal hypothalamus were described previously21, 22, 57. Briefly, anaesthetized mice under an ultra-precise stereotax (resolution: 10 μm, David Kopf Instruments) were injected with purified lentiviruses in the vehicle (PBS) into each side of the mediobasal hypothalamus through a guide cannula directed to the coordinates at 0.17 mm posterior to the bregma, 0.03 mm lateral to the middle line, and 0.50 mm below the skull surface of mice.

Neurosphere culture and analysis

Hypothalamus was dissected from adult mice as described previously21, 22, 57. Tissues were cut into small pieces (~1 mm3), digested with 0.25% Papain (Worthington) for 30 min at 30°C, and gently triturated for approximately 10 times using fire-polished tips. Desired cell population was separated by density gradient centrifugation. After washing with Hibernate-A medium (BrainBits LLC) twice, cells were suspended in the growth medium containing Neurobasal-A (Invitrogen), 2% B27 (Invitrogen), 10 ng ml−1 EGF (Sigma) and 10 ng ml−1 b-FGF (Invitrogen), seeded in Ultra-low adhesion 6-well plates (Corning) at the density of 100, 000 cells per well, and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C. On day 7, neurospheres were collected through centrifugation, dissociated into single cells by trypsinization using TrypLE™ express media, and passaged in suspension culture to form further generations of neurospheres. Neurosphere counting: neurospheres prepared in 24-well plates were counted under a microscope. Neurosphere size quantitation: neurospheres were photographed microscopically and the diameters were measured using software Image J.

NSC proliferation and differentiation assays

NSC proliferation output assay: Neurospheres were dissociated into single cells and plated in Ultra-low adhesion 6-well culture plate at the density of 104 cells in 1 ml of the growth medium. Cells were passaged every 5 days at the density of 104 cells in 1 ml of growth medium. Viable cells in each passage were evaluated by trypan blue staining. The accumulated total cell number for each passage was calculated by assumption that the total cells from the previous passage were replated. Brdu incorporation assay: Neurospheres were dissociated into single cells and plated on poly-D-lysine (Sigma) and laminin (Roche)-coated coverslips at the density of 105 ml−1 in growth medium. Following 24-hour culturing, cells were treated with Brdu (Sigma) at the final concentration of 10 μM for 2 hours. Subsequently, cells were washed and fixed with 4% PFA for Brdu staining. Tunnel assay: Neurospheres were dissociated into single cells and plated into poly-D-lysine and laminin-coated coverslips at the density of 105 in 1 ml of growth medium. Following 24-hour culturing, cells were fixed and examined for apoptosis using the TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (Upstate). Images were captured from multiple areas in the sections on random basis using a con-focal microscope for counting and statistical analysis. NSC differentiation: Dissociated single cells were seeded in poly-D-lysine and laminin-coated coverslips placed in 24-well plates. Cells were cultured in the differentiation medium (Neurobasal-A, 2% B27 and 1% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 1 μM retinoic acid). Culture medium was changed every other day, and neural differentiation was induced for one week.

Lentiviruses and cell transduction

Lentiviral vectors (Invitrogen) were constructed to express CAIKKβ (GFP-conjugated), DNIκBα (GFP-conjugated) or GFP controlled by CMV promoter. Lentiviral vectors containing shRNA against each Notch isoform including Notch1, 2, 3 and 4 and matched control lentiviral vector were purchased from Sigma (please see detailed information in supplementary information). Lentiviruses were produced by co-transfecting viral expression vectors with the package plasmids into HEK 293 FT cells (ATCC), as described previously22, 57. NSC transduction: NSCs were maintained in the growth medium with lentiviruses for 3 days, and followed by cell selection process through adding nucleoside antibiotic blasticidin (1μg ml−1) to the culture medium. Cells tranduced with lentiviral DNAs were resistant to blasticidin, and were monitored for the induction of GFP via a fluorescent microscope. Transduced cells were stably passaged in blasticidin-containing selection growth medium, and the presence of GFP in all cells was monitored over passages.

Promoter assays

Promoter sequences of mouse DLL4, Notch1, and Notch4 genes were PCR amplified (−1987 to +41 for DLL4, −717 to +92 for Notch1, and −708 to +16 for Notch4), and sub-cloned into the pGL3 luciferase vector (Promega) using standard strategies. Point mutations were made on GGRRNNYYCC decamers present in the promoter sequences to disrupt the NF-κB DNA-binding base pairs (GGGGGCCTCC was replaced with CACTTAGTGA for DLL4, GGGGAGTTCCC replaced with GTTGAGGGAAG for Notch1, and GGGGAGTTCC replaced with TTCCAGAAGA for Notch4). HEK 293 cells (ATCC) were cultured in standard conditions at 37°C and 5% CO2 with DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and PenStrep, and transfected with luciferase plasmid and expression plasmid via Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega) was performed according to the manufacturer's instruction, and co-transfection of pRL-TK was used to internally control firefly activity. Empty plasmids pGL3 and pcDNA3.1 were used as negative controls.

Heart Perfusion, tissue or cell immunostaining and imaging

Mice under anesthesia were trans-heart perfused with 4% PFA, and the brains were removed, post-fixed in 4% PFA for 4 hours, and infiltrated in 20%–30% sucrose. Brain sections (20 μm) were made using a cryostat at −20°C. Cultured cells on coverslips were fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature. For Brdu staining, samples were pre-treated with 2M HCl for 20 min followed by 2-min incubation with 0.1M sodium borate (pH 8.5). Fixed tissue sections or cells were blocked with serum of appropriate species, penetrated with 0.2% Triton-X 100, treated with primary antibodies and followed by reaction with Alexa Fluor® 488 or 555 or 633 secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). Naïve IgGs of appropriate species were used as negative controls. Primary antibodies included rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:500; Woka, 019-19741), rabbit anti-S100B (1:1000; ABcam, ab41548), rabbit anti-Blbp (1:300; Millipore, ABN14) and rabbit anti-musashi1 (1:500; Millipore, AB5977); mouse anti-RIP (1:300; Stem cells technology, Clone NS-1, 01433); mouse anti-Tuj1 (1:500, Cell Signaling, 4466), mouse anti-Brdu (1:1000, Cell Signaling, #5292) and mouse anti-TNFα (1:100, Abcam, Clone 52b83, AB1793), mouse anti-GFAP (1:500; Millipore, Clone EPR1034Y, 04-1062), mouse anti-O4 (1:100, Millipore, MAB345), mouse anti-nestin (1:100; Millipore, Clone Rat-401, MAB 353) and mouse anti-NeuN antibodies (1:100; Millipore, Clone A60, MAB 377) and mouse anti-Sox2 antibody (1:200, R&D Systems, Clone 245610, MAB2018); Goat anti-Cre (1:200, santa cruze, sc-83398) and sheep anti-α-MSH antibody (1:500; Millipore, AB5087).

Western blot, biochemistry, and quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Western blot analysis was performed using proteins extracted from cells and dissolved in a lysis buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and identified by immunoblotting. Primary antibodies were rabbit anti-phosphorylated RelA (1:1000, Cell signaling, #3033), rabbit anti-RelA (1:1000, Cell signaling, #4764), rabbit anti-cleaved Notch1 (1:1000, Cell signaling, #3447) and rabbit anti-β-actin (1:1000, Cell Signaling, #4967). Secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated antibodies (Pierce). TNF-α and IL-1β concentrations in cultured media were measured using ELISA kits (Ebioscience). Cells were plated in 24 wells at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well, and were transfected on the following day with TNFα siRNA (Sigma, SASI_Mm01_00047023) and IL1 β siRNA (Sigma, SASI_Mm01_00125194) via Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX Reagent (Invitrogen). Total RNA from cells was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) following the manual. cDNA was synthesized using the Advantage RT for PCR kit (BD Biosciences). Real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Relative gene expression levels were normalized against mRNA levels of housing-keeping β-actin. Please see supplementary information for detailed primer and RNAi information.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. Statistical differences were evaluated using Student's t-test for two-group comparison or ANOVA and appropriate post hoc analyses for >2-group comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors sincerely thank D. F. Gage for Sox2 promoter-containing lentiviral vector, D. Hickstein for CD11b promoter cDNA, and Cai's laboratory members for general technical assistance. This study was supported by Albert Einstein College of Medicine internal start-up funds and NIH R01 DK078750 and R01 AG031774 (all to D. Cai).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS D.C. conceived the project and designed the study. J.L. did all experiments and participated in the experimental design. Y.T. generated luciferase constructs of wildtype and mutant Notch signaling element gene promoters. J.L. and D.C. did data interpretation and discussion. D.C. wrote the paper.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERETS The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255:1707–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray J, Peterson DA, Schinstine M, Gage FH. Proliferation, differentiation, and long-term culture of primary hippocampal neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:3602–3606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron HA, McKay R. Stem cells and neurogenesis in the adult brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1998;8:677–680. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johansson CB, et al. Identification of a neural stem cell in the adult mammalian central nervous system. Cell. 1999;96:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80956-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gage FH. Mammalian neural stem cells. Science. 2000;287:1433–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross CG. Neurogenesis in the adult brain: death of a dogma. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2000;1:67–73. doi: 10.1038/35036235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison SJ. Neuronal potential and lineage determination by neural stem cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001;13:666–672. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.varez-Buylla A, Lim DA. For the long run: maintaining germinal niches in the adult brain. Neuron. 2004;41:683–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emsley JG, Mitchell BD, Kempermann G, Macklis JD. Adult neurogenesis and repair of the adult CNS with neural progenitors, precursors, and stem cells. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005;75:321–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gould E. How widespread is adult neurogenesis in mammals? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:481–488. doi: 10.1038/nrn2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitman MC, Greer CA. Adult neurogenesis and the olfactory system. Prog. Neurobiol. 2009;89:162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temple S. The development of neural stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:112–117. doi: 10.1038/35102174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doetsch F, Caille I, Lim DA, Garcia-Verdugo JM, varez-Buylla A. Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cell. 1999;97:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merkle FT, Mirzadeh Z, varez-Buylla A. Mosaic organization of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Science. 2007;317:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1144914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kriegstein A, varez-Buylla A. The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;32:149–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokoeva MV, Yin H, Flier JS. Neurogenesis in the hypothalamus of adult mice: potential role in energy balance. Science. 2005;310:679–683. doi: 10.1126/science.1115360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kokoeva MV, Yin H, Flier JS. Evidence for constitutive neural cell proliferation in the adult murine hypothalamus. J. Comp Neurol. 2007;505:209–220. doi: 10.1002/cne.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierce AA, Xu AW. De novo neurogenesis in adult hypothalamus as a compensatory mechanism to regulate energy balance. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:723–730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2479-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNay DE, Briancon N, Kokoeva MV, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS. Remodeling of the arcuate nucleus energy-balance circuit is inhibited in obese mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:142–152. doi: 10.1172/JCI43134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee DA, et al. Tanycytes of the hypothalamic median eminence form a diet-responsive neurogenic niche. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:700–702. doi: 10.1038/nn.3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purkayastha S, et al. Neural dysregulation of peripheral insulin action and blood pressure by brain endoplasmic reticulum stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:2939–2944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006875108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, et al. Hypothalamic IKKbeta/NF-kappaB and ER stress link overnutrition to energy imbalance and obesity. Cell. 2008;135:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai D, Liu T. Hypothalamic inflammation: a double-edged sword to nutritional diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011;1243:E1–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai D, Liu T. Inflammatory cause of metabolic syndrome via brain stress and NF-kappaB. Aging (Albany. NY) 2012 doi: 10.18632/aging.100431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purkayastha S, Zhang G, Cai D. Uncoupling the mechanisms of obesity and hypertension by targeting hypothalamic IKK-beta and NF-kappaB. Nat. Med. 2011;17:883–887. doi: 10.1038/nm.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayden MS, West AP, Ghosh S. SnapShot: NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Cell. 2006;127:1286–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann A, Baltimore D. Circuitry of nuclear factor kappaB signaling. Immunol. Rev. 2006;210:171–186. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Verma IM. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:725–734. doi: 10.1038/nri910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karin M, Lin A. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:221–227. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vousden KH. Partners in death: a role for p73 and NF-kB in promoting apoptosis. Aging (Albany. NY) 2009;1:275–277. doi: 10.18632/aging.100033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dutta J, Fan Y, Gupta N, Fan G, Gelinas C. Current insights into the regulation of programmed cell death by NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 2006;25:6800–6816. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rolls A, et al. Toll-like receptors modulate adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:1081–1088. doi: 10.1038/ncb1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koo JW, Duman RS. IL-1beta is an essential mediator of the antineurogenic and anhedonic effects of stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:751–756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708092105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koo JW, Russo SJ, Ferguson D, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Nuclear factor-kappaB is a critical mediator of stress-impaired neurogenesis and depressive behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:2669–2674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910658107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.is-Donini S, et al. Impaired adult neurogenesis associated with short-term memory defects in NF-kappaB p50-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:3911–3919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0148-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martino G, Pluchino S. The therapeutic potential of neural stem cells. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:395–406. doi: 10.1038/nrn1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villeda S, Wyss-Coray T. Microglia--a wrench in the running wheel? Neuron. 2008;59:527–529. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villeda SA, et al. The ageing systemic milieu negatively regulates neurogenesis and cognitive function. Nature. 2011;477:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niswender KD, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW. Insulin and its evolving partnership with leptin in the hypothalamic control of energy homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;15:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Munzberg H, Myers MG., Jr. Molecular and anatomical determinants of central leptin resistance. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:566–570. doi: 10.1038/nn1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flier JS. Neuroscience. Regulating energy balance: the substrate strikes back. Science. 2006;312:861–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1127971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coll AP, Farooqi IS, O'Rahilly S. The hormonal control of food intake. Cell. 2007;129:251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thaler JP, et al. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:153–162. doi: 10.1172/JCI59660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suh H, et al. In vivo fate analysis reveals the multipotent and self-renewal capacities of Sox2+ neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:515–528. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilyarov AV. Nestin in central nervous system cells. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2008;38:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s11055-008-0025-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vacca A, et al. Notch3 and pre-TCR interaction unveils distinct NF-kappaB pathways in T-cell development and leukemia. EMBO J. 2006;25:1000–1008. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oakley F, et al. Basal expression of IkappaBalpha is controlled by the mammalian transcriptional repressor RBP-J (CBF1) and its activator Notch1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:24359–24370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Espinosa L, Ingles-Esteve J, Robert-Moreno A, Bigas A. IkappaBalpha and p65 regulate the cytoplasmic shuttling of nuclear corepressors: cross-talk between Notch and NFkappaB pathways. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:491–502. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng P, et al. Notch-1 regulates NF-kappaB activity in hemopoietic progenitor cells. J. Immunol. 2001;167:4458–4467. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borghese L, et al. Inhibition of notch signaling in human embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem cells delays G1/S phase transition and accelerates neuronal differentiation in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cells. 2010;28:955–964. doi: 10.1002/stem.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carlen M, et al. Forebrain ependymal cells are Notch-dependent and generate neuroblasts and astrocytes after stroke. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:259–267. doi: 10.1038/nn.2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Louvi A, rtavanis-Tsakonas S. Notch signalling in vertebrate neural development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:93–102. doi: 10.1038/nrn1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oya S, et al. Attenuation of Notch signaling promotes the differentiation of neural progenitors into neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region after ischemic injury. Neuroscience. 2009;158:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lutolf S, Radtke F, Aguet M, Suter U, Taylor V. Notch1 is required for neuronal and glial differentiation in the cerebellum. Development. 2002;129:373–385. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.rtavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hansen DV, Lui JH, Parker PR, Kriegstein AR. Neurogenic radial glia in the outer subventricular zone of human neocortex. Nature. 2010;464:554–561. doi: 10.1038/nature08845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang G, et al. Neuropeptide exocytosis involving synaptotagmin-4 and oxytocin in hypothalamic programming of body weight and energy balance. Neuron. 2011;69:523–535. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.