Abstract

To provide a basis for improved prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus (HBV) re-infection after liver transplantation, variations in the S and P genes of HBV under immunosuppression in vitro and their association with patient prognosis were investigated. For the in vitro study, HepG2.2.15 hepatocellular carcinoma cells stably producing HBV particles were treated with the immunosuppressants methylprednisolone (MP) and tacrolimus (FK506) at doses found to be non-toxic by the methylthiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) cell viability assay. MP dose-dependently inhibited HBV DNA expression in HepG2.2.15 cells, while FK506 did not, as determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). By gene sequencing, both MP and FK506 were found to cause variations in HBV S, P, and S/P overlapping regions. MP- but not FK506-induced mutations were common in the glucocorticoid response element of the P region, while both immunosuppressants caused mutations outside the nucleoside analogue resistance sites. For the in vivo study, 14 patients with HBV-related end-stage liver disease re-infected after liver transplantation, and 20 cases without HBV re-infection as controls, were studied. Seventy-five percent of re-infected recipients showed multi-loci amino acid mutations at different sites besides lamivudine (LAM)-resistant loci in the P region, including in the glucocorticoid response element. Fifty percent of re-infected recipients had mutations in the “a” determinant region and flanking sequences. Re-infection was associated with negative serum hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG), as measured by a microparticle capture enzyme immunoassay. Nucleotide mutations in the S region caused missense or synonymous mutations, which caused synonymous mutations in the overlapping P region. These results showed that effects of immunosuppressants on HBV genes in vitro were different from those in clinical recipients. Positive HBV DNA and gene mutations pre-transplantation were factors affecting re-infection post-transplantation. Multiple mutations found in the P and S genes suggest that the formation of quasispecies contributes to HBV re-infection after liver transplantation.

Introduction

Every year in China more than 300 thousand patients die of end-stage liver disease. Of the more than 30 million patients with chronic liver disease in China, 80% are infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV). The most effective treatment for HBV-related end-stage liver disease is liver transplantation, but without effective prophylaxis, the risk of HBV re-infection after transplantation may be more than 80% (1,18), which may lead to graft failure and the need for a second transplantation. The common use of anti-HBV and immunosuppressant agents has greatly improved the long-term effects of liver transplantation, and combined low-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) and nucleoside analogues such as lamivudine (LAM) are the currently accepted regimens for prevention and treatment of HBV re-infection. Although HBV re-infection after transplantation is significantly reduced by these treatments, approximately 10% of cases still fail (17,1), threatening the long-term survival of the graft (23).

During long-term infection, HBV needs to adapt to the host environment, medications, and vaccines, leading to variations in the genome. HBV gene heterogeneity is associated with HBV re-infection after transplantation. HBV belongs to the hepatotropic virus family, and its genome is an incomplete double-chain circular DNA. The long chain contains four regions, namely the pre-C/C, X, pre-S/S, and DNA-P regions (16). A recent clinical study associated HBV re-infection, among other factors, with LAM-resistant mutation sites in the P region (3,7). Methylprednisolone (MP) and tacrolimus (FK506) are the most commonly used immunosuppressants after organ transplantation, and some studies unfortunately have shown that immunosuppressants can increase HBV replication. The glucocorticoid response element region in the HBV genome, activated by engagement of the glucocorticoid receptor, has been shown to increase gene transcription and HBV replication, thereby accelerating the process of HBV re-infection in the graft (22). Other researchers have found that glucocorticoid stimulates HBV release outside the liver tissue, and the low level of released HBV is reactivated and expressed again (26). However, recent studies showed that not all immunosuppressants increase HBV replication, and some even show inhibitory effects. In a study by Xia et al. (30), cyclosporine was shown to dose-dependently inhibit HBV replication in vitro, while FK506 had no effect.

Recent studies correlated HBV re-infection after transplantation with variations in the S and P regions, which render resistance to high-titer HBIG and nucleoside analogues (28). However, the nature of the quasispecies and drug-resistant HBV induced by the combined use of immunosuppressants, nucleoside analogues, and HBIG, is not known. Specifically, whether HBV re-infection under immunosuppression correlates with variations in the S and P regions, and whether other in vivo factors are involved in this process is not clear. In this study the factors associated with HBV re-infection after liver transplantation and variations in the S and P region of HBV under immunosuppression were investigated both in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Cells and reagents

The human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 was obtained from the Chongqing Institute of Hepatology. The HepG2.2.15 cell line was donated by Wei Lai of the Hepatology Institute of Peking University Affiliated Hospital. MP was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Tacrolimus (FK506) was donated by Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. (Chuo-ku, Osaka, Japan). Methylthiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were obtained from Amresco (Solon, OH). Propidium iodide (PI) and the DNA extraction and detection kit were purchased from Shanghai Kehua Bio-Engineering Company (Shanghai, China). Plasmid extraction reagents were purchased from Shanghai Chaoshi Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China). DIG-High-Primer was purchased from Roche (Shanghai, China). Elecsy, Multikan Ascent microplate reader and the DEM-1 ELISA plate washer were purchased from Roche. Other equipment included the fluorescence-based ABI 7500 quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), automatic fluorescence quantitative flow cytometry (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), and RT-6000 automatic microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT). PCP10 was donated by Professor Cheng Jun from Beijing Ditan Hospital.

Patients

Three-hundred twenty patients receiving liver transplantation due to HBV-related end-stage liver disease between June 2002 and December 2003 were followed up for 18–36 mo, until September 2005. Among them 20 recipients were diagnosed with HBV re-infection based on clinical manifestations, laboratory examinations, and liver biopsies. Infections with other viruses were excluded. Fourteen HBV re-infected recipients with complete medical records were selected as the experimental group. Twenty recipients without HBV re-infection were randomly selected as the control group. Of all the patients, 31 were male and 3 were female, and their ages ranged from 25–66 y (mean 42±9.8 y). Among the HBV re-infected transplantation recipients, 7 were diagnosed with HBV-related liver cirrhosis before transplantation, 4 had severe hepatitis, and the other 3 had HBV-related cirrhosis combined with hepatocellular carcinoma. In the control group, 10 were diagnosed with HBV-related liver cirrhosis before transplantation, 4 had severe hepatitis, 5 had HBV-related cirrhosis combined with hepatocellular carcinoma, and the remaining patient had liver cirrhosis due to infection with both HBV and HCV (Table 1). The study was approved by the hospital's research and ethics committee.

Table 1.

General Characteristics of HBV Re-infected Liver Transplant Recipients

| No. | Gender | Age | Primary disease | Genotype/serotype | HBsAg/Ab before transplant | HBeAg/Ab before transplant | HBcAb before transplant | HBV-DNA before transplant (copies/mL) | Re-infection time (mo) | HBsAb concentration (IU/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 60 | HBV-related cirrhosis | C/adr | +/− | +/− | + | 1.22×106 | 6 | 0 |

| 2 | Male | 46 | Chronic severe hepatitis B | C/adr | +/− | −/+ | + | 9.05×107 | 5 | 0 |

| 3 | Male | 50 | HBV-related cirrhosis | C/adr | +/− | +/− | + | 6.57×107 | 14 | 92.3 |

| 4 | Male | 52 | Primary hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatitis B | C/adr | −/− | −/+ | + | <103 | 14 | 0 |

| 5 | Male | 31 | HBV-related cirrhosis | C/adr | +/− | +/− | + | 1.7×105 | 9 | 0 |

| 6 | Male | 40 | Chronic severe hepatitis B | C/adr | +/− | −/+ | + | <103 | 18 | 67.6 |

| 7 | Male | 47 | Primary hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatitis B | C/adr | +/− | +/− | + | 1.75×103 | 3 | 0 |

| 8 | Male | 51 | HBV-related cirrhosis | C/adr | +/− | −/+ | + | 4.35×105 | 7 | 0 |

| 9 | Male | 50 | HBV-related cirrhosis | C/adr | +/− | +/− | + | 1.43×105 | 18 | 62.7 |

| 10 | Male | 40 | Chronic severe hepatitis B | B/adw | +/− | −/+ | + | <103 | 8 | 80.1 |

| 11 | Male | 40 | HBV-related cirrhosis | C/adr | −/− | −/− | + | 1.28×106 | 19 | 61.8 |

| 12 | Male | 47 | Primary hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatitis B | C/adr | +/− | −/+ | + | 1.22×103 | 8 | 128.7 |

| 13 | Female | 37 | HBV-related cirrhosis | C/adr | +/− | −/+ | + | 9.95×107 | 10 | 298.3 |

| 14 | Female | 51 | HBV-related cirrhosis | B/adw | +/− | −/− | + | <103 | 12 | 0 |

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAb, hepatitis B surface antibody.

Cell culture

Human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin 100 U/mL, and streptomycin 100 mg/L, in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. HepG2.2.15 cells were cultured in high glucose-DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 200 mg/L G418, 6 mmol/L glutamine, penicillin 100 U/mL, and streptomycin 100 mg/L, in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Methylthiazolyl tetrazolium cell viability assay

Monolayers of cultured cells were digested with 0.05% trypsin for about 15 min, and then a single-cell suspension was prepared in medium with 10% FBS. After counting, the cell concentration was adjusted to 5×104 cells/mL, and 200 μL of the cell suspension (1×104 cells) was added to each well of a 96-well plate, which was incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cells were treated with different concentrations of MP or FK506 for 24, 48, or 72 h. Then MTT solution (20 μL at 5 g/L) was added to every well and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 4 h. After terminating the incubation, the medium was aspirated, DMSO (150 μL) was added to each well, and the plate was placed on the shaker for 10 min to fully dissolve the crystals. The absorbance value (A) at 490 nm was measured using an automatic microplate reader, and the cell survival rate was calculated as follows: survival rate=(A of test well – A of blank well)/(A of control well – A of blank well)×100%.

Methylprednisolone or FK506 treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma cells

Three generations of cells were drug treated. The cells were treated with fresh medium containing different concentrations of MP or FK506. Cells cultured in drug-free medium were used as the control group. Concentrations of MP were categorized as low (10 and 50 (g/L), and high (100 and 250 (g/L). The concentrations of FK506 were also categorized as low (50 (g/L), and high (100 and 500 (g/L). After treatment for 24, 48, or 72 h, the cells and supernatants were collected and preserved at −80°C for subsequent DNA extraction for qRT-PCR analysis of HBV DNA and detection of HBV covalently-closed circular DNA (cccDNA).

DNA extraction from HepG2.2.15 cells and culture supernatant

Twenty-four hours after subculture, the HepG2.2.15 cells were treated with different concentrations of MP or FK506. When more than 95% of the cells survived, we deemed the concentration as safe/non-toxic. After treatment for 24, 48, or 72 h, the supernatants and cells were collected and preserved at 4°C for subsequent detection. HBV DNA was extracted using the Shanghai Kehua DNA extraction and detection kit, and cccDNA was extracted with Shanghai Chaoshi plasmid extraction reagents.

Determination of HBV DNA in supernatants by qRT-PCR

The supernatant HBV DNA levels were tested using a real-time PCR kit (Shanghai Kehua), according to the manufacturer's instructions, on an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The automatic fluorescence quantitative flow cytometry (PerkinElmer), and RT-6000 automatic microplate reader (Bio-Tek) were used for analysis. This kit was approved by the State Food and Drug Administration of China for in vitro diagnosis with a low detection limit (21).

Detection of cccDNA in HepG2.2.15 cells

The following HBV cccDNA primer sequences were designed based on the sequence of GenBank NC_003977: 1 (GI: 21326584): F: TTCTC ATCTG CCGGA CC (HBV genome position 1560–1576); P: FAM-ATGT CCTAC TGTTC AAGCC TCCAA-TAMRA (HBV genome position 1852–1871); R: GGC ATGGACATTG ACCC (HBV genome position 1898–1914). The primers were synthesized by Shanghai Jikang. For each reaction, the total volume was 25 μL, containing 2.5 μL template DNA, 300 nM/L primers, probe at a final concentration of 150 nM/L, and 12.5 μL MIXI. The amplification conditions were one cycle at 95°C for 5 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, and 58°C for 90 sec. The positive control was the PCP10 purified plasmid containing double copies of the whole HBV genome (kindly provided by Cheng Jun, Beijing Ditan Hospital). The negative control was DNA extracted from HepG2 cells. PCR products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Gene sequencing

The HBV DNA (HepG2.2.15) U95551.1-GI:2182117 whole genome sequence and highly conserved sequences of the S and P genes were found in Genbank of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). A set of primers was designed to amplify and clone genes from the S and P regions (Table 2), and to determine the genotype and mutations. HBV DNA was extracted using a kit from QIAGEN (Valencia, CA), and gene sequencing was performed by Shanghai Jikang Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China), using the 3700 DNA sequencer (ABI, Carlsbad, CA), with universal forward and reverse primers for the cloning vector. The DNA products were analyzed using DNA Star software. After sequencing, the amino acid sequences of the HBV genes were analyzed in order to identify the mutations.

Table 2.

Primer Sequences for Amplifying the S and P Regions of HBV

| Gene | Primer sequence | Amplified fragment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| S gene | Upstream nt 56–72 | 5′-CCTGCTGGTGGCTCCAG-3′ | 796 bp |

| Downstream nt 824–842 | 5′-TTAGGGTTTAAATGTATAC-3′ | ||

| Upstream nt 247–266 | 5′-CCTGCTGGTGGCTCCAG-3′ | 600 bp | |

| Downstream nt 740–759 | 5′-GGGCATTTGGTGGTCTATA-3′ | ||

| P gene | Upstream nt 481–495 | 5′-ACT TCC AGG AAC ATC-3′ | 804 bp |

| Downstream nt 1270–1284 | 5′-TAG GAG TTC CGC AGT-3′ | ||

| Upstream nt 561–575 | 5′-CTT GTT GCT CTA CAA-3′ | 517 bp | |

| Downstream nt 1172–1186 | 5′-CAA ACA CTT GGC AGA-3′ | ||

HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Regimen for immunosuppression and anti-HBV treatment

All recipients received triple immunosuppressants, including FK506 and MP. LAM was taken at least 2 wk before transplantation. A high dose of HBIG was infused during the operation, and the combination of LAM and HBIG was used after transplantation. HBIG titers were measured by microparticle enzyme immunoassays (AxSYM AUSAB; Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Detection of mutations in the S and P regions of HBV from patients by gene sequencing

The whole genome sequence of HBV and highly conserved sequences of the S and P genes were obtained from NCBI Genbank under accession number HBV-DQ986376. A set of primers were designed based on these sequences to determine mutations in the S and P regions (Table 2). Extraction and detection of HBV DNA was performed as described above. The DNA products were analyzed using DNA Star software to compare with published adw and adr subtypes to determine the genotype and gene mutations (13).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 10.0 was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as means±standard deviation. Univariate analysis of variance was used for comparison between groups, and the q test for comparison between two groups. Dunnett's C method was used when the variance was not homogenous. Count data of the patients between the re-infection groups and non-re-infection groups were compared by the chi-square test. The relationships between drug concentration and variable indexes were tested by bivariate correlation analysis (Pearson test). The level of p<0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

Results

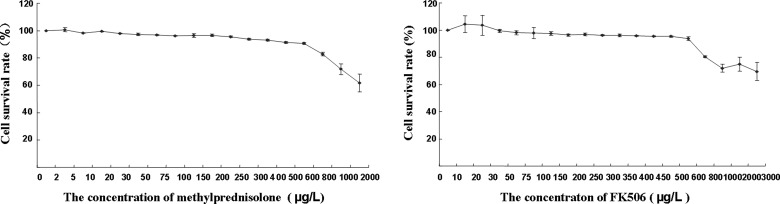

Effects of MP and FK506 on HepG2.2.15 cell survival

HepG2.2.15 cells were treated with different concentrations of MP and FK506 for 24, 48, and 72 h to determine the survival rate. There was no significant difference in the survival rate (viability) between treatments for 24, 48, and 72 h. Fig. 1 shows the survival rate under treatments with different concentrations of MP/FK506 for 72 h. For HepG2.2.15, the MP concentrations of 0–250 (g/L, and FK506 concentrations of 0–500 (g/L were safe, indicating that the cells were not significantly inhibited (survival rate >95%).

FIG. 1.

Survival rates of HepG2.2.15 cells treated with different concentrations of MP and FK506 for 72 h.

Effects of different concentrations of MP and FK506 on HBV DNA and cccDNA expression in HepG2.2.15 cells

HepG2.2.15 cells were treated with different concentrations of MP to determine the effects on HBV DNA expression at different time points. The results showed that HBV DNA expression decreased with MP treatment in a concentration-dependent manner. The differences were statistically significant between each concentration and the control group (0 μg/L), as shown in Table 3. These results suggest that MP had a dose-dependent (but time-independent) inhibitory effect on HBV DNA in vitro. When treated with FK506, HBV DNA expression of HepG2.2.15 cells showed no significant difference compared with the control group (Table 3), suggesting that FK506 had no inhibitory effect on HBV replication in vitro.

Table 3.

Effects of Different Concentrations of MP and FK506 on HBV DNA in HepG2.2.15 Cells (n=3)

| |

|

HBV DNA (log10 copies/mL) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication | Concentration (μg/L) | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

| MP | 0(1) | 7.0940±0.2389 | 6.7511±0.0577 | 6.3799±0.3973 |

| MP | 10(2) | 6.4632±0.2961 | 5.5023±0.2925 | 5.7821±1.1861 |

| MP | 50(3) | 5.3705±0.3239 | 5.1875±0.2211 | 4.6730±0.4476 |

| MP | 100(4) | 4.7231±0.0879 | 4.8842±0.1091 | 4.7865±0.0398 |

| MP | 250(5) | 4.5739±0.0735 | 4.4997±0.0248 | 4.1468±0.1016 |

| F | 69.053** | 73.358** | 30.366** | |

| r | −0.957 | −0.927 | −0.917 | |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| FK506 | Control group(1) | 5.1126±0.1331 | 5.5691±0.1907 | 6.2491±0.1761 |

| FK506 | 50(2) | 4.6379±0.3692 | 4.7083±0.1963 | 6.1639±0.1354 |

| FK506 | 100(3) | 4.5368±0.2338 | 4.8246±0.3577 | 6.0457±0.1181 |

| FK506 | 500(4) | 4.4856±0.2583 | 5.2264±0.5135 | 6.0644±0.1817 |

| F | 3.579 | 3.987 | 1.110 | |

| r | −0.676 | −0.232 | −0.498 | |

| p | 0.016 | 0.469 | 0.099 | |

p<0.01.

HepG2.2.15 cells were treated with different concentrations of MP and FK506 as indicated to determine the effects on HBV DNA expression at different times. The results showed that HBV DNA expression decreased with increasing concentrations of MP. The differences were statistically significant between each concentration and the control group (0 μg/L). These results suggest that MP had a dose-dependent (but time-independent) inhibitory effect on HBV DNA in HepG2.2.15 cells. FK506 showed no significant effect on HBV DNA levels compared with the control group.

MP, methylprednisolone; FK506, tacrolimus; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

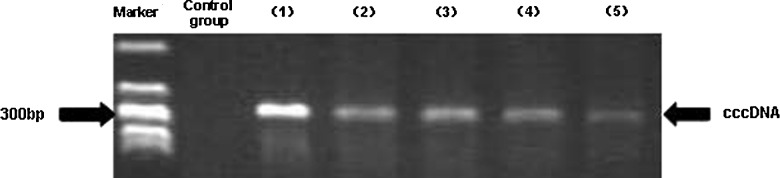

The effects of MP on cccDNA expression were also evaluated. After HepG2.2.15 cells were treated with different concentrations of MP determined to be safe, cccDNA expression significantly decreased compared with the control group (Table 4 and Fig. 2). These results suggest that MP had an inhibitory effect on cccDNA. Although it was not related to time of exposure, the inhibitory effect increased as the MP concentration increased (r=−0.957, −0.927, −0.917; p≤0.001), suggesting that MP had a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on HBV cccDNA in vitro.

Table 4.

Effects of Different Concentrations of MP and FK506 on cccDNA in HepG2.2.15 Cells (n=3)

| |

|

HBV cccDNA (copies/mL) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication | Concentration (μg/L) | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

| MP | 0(1) | 6.9279±0.0278 | 6.9480±0.0119 | 6.8164±0.0752 |

| MP | 10(2) | 6.2319±0.4287 | 5.9526±0.0454 | 5.8975±0.0295 |

| MP | 50(3) | 6.1858±0.7162 | 5.5906±0.1751 | 5.7471±0.0524 |

| MP | 100(4) | 5.7439±0.8762 | 5.5800±0.0979 | 5.1162±0.0038 |

| MP | 250(5) | 5.1583±0.3957 | 5.1427±0.3142 | 4.8272±0.0364 |

| F | 3.956* | 49.283** | 842.499** | |

| r | −0.762 | −0.902 | −0.972 | |

| p | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| FK506 | 0(1) | 6.2142±0.1357 | 6.3327±0.0224 | 6.3972±0.0824 |

| FK506 | 50(2) | 5.9847±0.1808 | 5.9449±0.2451 | 6.4222±0.1501 |

| FK506 | 100(3) | 6.0663±0.0502 | 5.8854±0.2664 | 5.7476±0.3293 |

| FK506 | 500(4) | 5.59033±0.0449 | 5.6382±0.4164 | 5.5517±0.6007 |

| F | 3.791 | 3.251 | 4.790 | |

p<0.05; **p<0.01.

HepG2.2.15 cells were treated with different concentrations of MP and FK506. The cccDNA levels were significantly decreased by MP in a concentration-dependent (but time-independent) manner compared with the control group (r=−0.957, −0.927, −0.917; p≤0.001). FK506 had no inhibitory effect on cccDNA replication in vitro (p>0.05).

MP, methylprednisolone; FK506, tacrolimus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; cccDNA, covalently-closed circular DNA.

FIG. 2.

Effect of MP on cccDNA in HepG.2.2.15 cells. Control: DNA extracted from HepG2 cells as negative control. Lane 1: PCP10-purified plasmid as positive control. Lanes 2–5: HepG.2.2.15 cells treated with MP at concentrations of 10 μg/L, 50 μg/L, 100 μg/L, and 250 μg/L, respectively.

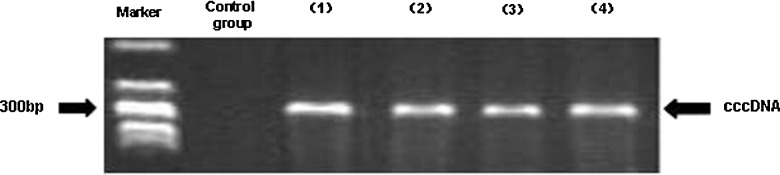

When the HepG2.2.15 cells were treated with different concentrations of FK506 for different time periods, there was no significant difference in the expression of cccDNA compared with the control group (Table 4 and Fig. 3). This result suggested that FK506 had no inhibitory effect on cccDNA replication in vitro (p>0.05).

FIG. 3.

Effect of FK506 on cccDNA in HepG.2.2.15 cells. Control: DNA extracted from HepG2 cells as negative control. Lane 1: PCP10-purified plasmid as positive control. Lanes 2–4: HepG.2.2.15 cells treated with FK506 at concentrations of 50 μg/L, 100 μg/L, and 500 μg/L, respectively.

Effects of MP and FK506 on HBV gene sequences in vitro

The effects of MP on HBV gene sequences were evaluated. In the S region, as the concentration of MP increased, changes in nucleotides and amino acids decreased, and there was no mutation in the “a” determinant region. In the P region, MP induced mutations at the nucleotide and amino acid levels, especially at high concentrations, and the mutations were in rt148-170 and rt307-379 (Table 5). Mutations induced by MP were found in the glucocorticoid response element (nt1080–nt1234) of the P region: ntT1082A change, nt1086C insertion, ntT1091A change, ntC1094G change, nt1095G insertion, nt1137T insertion, nt1146T deletion, nt1154T deletion, nt1160G deletion, ntA1163T change, and nt1164T insertion.

Table 5.

Effects of MP and FK506 on HBV Gene Sequences in HepG2.2.15 Cells

| |

HBV gene sequence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Amino acid mutations in S region |

Amino acid mutations in P region |

||

| Concentration | MP | FK506 | MP | FK506 |

| Control | No mutation | No mutation | No mutation | No mutation |

| Low concentration | K2Q; P211L; L213M; C221G | C221G | rtK148E; rtF151I; rtA307G; rtY339T; rtD354G; rtA355R; rtT356N; rtP357K | No mutation |

| High concentration | L213M L215I |

T5I L213M L213F C221V |

rtY335N; rtG361G; rtM364H; rtH367S; rtQ368A; rtV370A; rtR371L; rtG372E; rtP373T; rtS374R; rtA375L; rtP376L; rtL377C; rtP379S | rtP138K; rtK154E; rtI169T; rtP170L; rtT184I; rtD354G; rtA355R; rtT356N; rtP357K; rtA382G |

Underlined mutations in the P region are at nucleoside analogue-resistant sites.

MP, methylprednisolone; FK506, tacrolimus; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Effects of FK506 on HBV gene sequences were also determined. In the S region, FK506 induced mutations at the nucleotide and amino acid levels, but most were nucleotide deletions, insertions, and mutations. Amino acid mutations were common in 203–221, but there was no mutation in the “a” determinant region. In the P region, FK506 induced changes in nucleotides and amino acids at rt138–184 and rt354–382, with few mutations in the glucocorticoid response element region (Table 5).

Effects of immunosuppressants on serum HBV DNA after transplantation

Based on serum HBV DNA before liver transplantation, the 14 re-infected patients and 20 non-re-infected patients could be divided into three groups: (1) 4 re-infected patients with <103 copies/mL (28.57%) versus 14 non-re-infected patients (70.00%); (2) 2 re-infected patients with ≥103–4 copies/mL (14.28%) versus 2 non-re-infected patients (10.00%); and (3) 8 re-infected patients with ≥105 copies/mL (57.14%) versus 4 non-re-infected patients (20.00%). Serum HBV DNA levels in the re-infected recipients after transplantation were in the range of 1.75×103–1.05×108 copies/mL.

The re-infection risk increased as the level of serum HBV DNA increased. When the patients were categorized according to whether HBV DNA was more than 103 copies/mL, the difference in the ratio between the re-infection groups and non-re-infection groups was statistically significant (χ2=5.673, p=0.017).

HBV gene mutations after transplantation

Results of gene sequencing in the S region before and after transplantation are shown in Table 6. Sequencing of the “a” determinant region (124–147) revealed the mutations T126I, T131N, S143T, and G145R. Within the sequences upstream and downstream of the “a” determinant region, the mutations L110F, I113S, and T160K were found. The number of mutations increased after transplantation, except that there was a S167 stop mutation instead of T160K.

Table 6.

Amino Acid Mutation Sites in the S Gene and RT Region of the P Gene in Patients (n=14)

| |

Mutation in S region amino acid |

Mutation in P region amino acid |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | a-determinant | Outside a-determinant | LAM-resistant mutation | Outside LAM-resistant mutation |

| Before transplant | I126T(2), I126S(3), A128A(1), G130G(2), S136S(1), S143T(1), N146N(2) | S3N(13), G10A(4), Q30R(2), N40N, F41S L42R(3), A45A(3), T47A(3), T47K(3), T57I, N59S, P62L(3), S64C, I68T(6), F69L, G71G, F85C, L98V(5), Y100Y(4), L110F, I113S, T115T, T118T, K122K, A128A(2), Q129K(2), G145S(2), T148T, S155S(2), T160K, S171S(2), L175stop, L176L, L176Q, V177V, V184A(3), A185E(2), L186L, I195M(3), L209L, F212L(3), F212V(7), T538C(2) | rtL180M(2), rtM204V(2) | rtE11E(10), rtR18T(4), rtT38T, rtF49L, rtS50S(3), rtS53N, rtT54S(2), rtH55R(4), rtH55Q(2), rtN65Q, rtQ67Q, rtT70T, rtL72V, rtN76N(3), rtS78T, rtL93L, rtS106C(5), rtP109S(2), rtT118I, rtN121I, rtY124N, rtG127R, rtD131N, rtH133H, rtD134E(4), rtS137Q, rtN139H, rtL145M, rtF151Y, rtR153Q, rtK154Q, rtL155L(2), rtL157L, rtL164P(2), rtK168K, rtF183L, rtT184I, rtS185N(2), rtR192C, rtL220V(4), rtF221V(3), rtV217V |

| After transplant | T125M, T125T(2), I126T(3), I126S, G130G(6), T131N(4), S136S(3), S143T, D144D(3), N146N(4) | S3N(5), T4I, T5A, F8S, R24K, A45T, D45D, T47A(4), T47K, P49L, P56Q, T57I, N59S, S64C, I68T(3), R73R, I82I, F85C, Y100Y, L110F, L110R, T113T, T115T(2), T118T, K122K, T125T, I126T, G130G, G145S, T148T(2), S155S, T160K, F161Y, S167stop(2), S171S(2), L175stop(2), V177V(2), V184A(2), M198I(2), W199L, L203S, F212V(3), A288T | rtL180M | rtE11E(5), rtH12H, rtP13R, rtI16T, rtK32K, rtS53N, rtH55R(3), rtH55Q, rtP64P, rtN65Q(2), rtQ67Q, rtL72V, rtN76N(3), rtL81M, rtL93L, rtP109S, rtT118I, rtT118T, rtT118D, rtI122F, rtY124H, rtY124N(2), rtG127R, rtD131N, rtD134N(2), rtD134E, rtD134D(5), rtN139Q(3), rtN139H(3), rtL145M(4), rtL145M, rtF151Y, rtR153W, rtR153Q, rtR153W(2), rtK154Q, rtL155L(5), rtL157L(2), rtL164P, rtK168K, rtI169I, rtS176G(2), rtF183L(2), rtS185N, rtR192C(2), rtV207M(2), rtL220V(2) |

Synonymous mutations in the S region before and after transplantation are shown in italics only. Underlined mutations are those in the RT region in the P gene overlapping the “a” determinant region of the S gene. Mutations that are both underlined and italicized are those in the RT region of the P region gene overlapping the S gene outside of the “a” determinant region. Numbers in brackets are frequencies of the mutations; no brackets indicates 1 frequency of mutation.

HBIG titers and HBV gene mutations were determined post-transplantation by microparticle capture enzyme immunoassay (MEIA) and sequencing, respectively. In the “a” determinant region, mutations were found in all seven HBV re-infected recipients whose HBIG levels were undetectable. N131T (seven cases) and T126I (six cases) were the most common, in addition to G145R/T (two cases) and S143T (one case). The other seven HBV re-infected recipients whose HBIG levels were detectable also showed mutations in the “a” determinant region. The most common were N131T (seven cases) and T126I (two cases), and there were no other mutation sites.

Synonymous amino acid mutations in the S region of HBV in re-infected recipients before and after transplantation were determined (Table 6). The number of nucleotide mutations in the S region showed no obvious change, but the mutation sites were slightly different (T274C and T538C before transplantation versus A493T, G529A, and C586T after transplantation). Interestingly, a mutation that was synonymous in the S region caused the missense mutation rtL180M in the overlapping P gene. This result suggested that while some nucleotide mutations did not change the amino acids in the S region, they could affect the protein sequence in the P region.

Missense mutations in the S region of HBV in re-infected recipients before and after transplantation were also determined (Table 7). The number of nucleotide mutations in the S region showed no change before and after transplantation (both 21). Missense mutations were found in the S region and likewise in the overlapping P gene. The frequencies of missense mutations such as rtR153Q, rtT184I, rtM204V, and rtV207I, which have been associated with immune evasion and resistance to nucleoside analogues, increased after transplantation. The nucleotide mutation sites were different: A289T, G633A, and T790G before transplantation, versus A167G, T176C, G748A, and G750T after transplantation.

Table 7.

Effects of Missense Mutations in the S Region on Mutations in the RT Region of the Overlapping P Gene in Patients

| No | Missense mutations in the S region before transplantation (aa) | Mutations in the RT region of the overlapping P gene before transplantation (aa) | Frequency (%) | Missense mutations in the S region after transplantation (aa) | Mutations in the RT region of the overlapping P gene after transplantation (aa) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | G10A | rtR18T | 28.57% (4/14) | T5A | rtP13R | 21.43% (3/14) |

| 2 | A45T | rtS53N | 7.143% (1/14) | F8S | rtI16T | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 3 | A45A | rtT54S | 14.29% (2/14) | G10A | rtR18T | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 4 | T47A | rtH55R | 21.43% (3/14) | A45T | rtS53N | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 5 | T47K | rtH55Q | 14.29% (2/14) | T47A | rtH55R | 21.43% (3/14) |

| 6 | T57I | rtN65Q | 7.143% (1/14) | T47K | rtH55Q | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 7 | S64C | rtL72V | 7.143% (1/14) | T57I | rtN65Q | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 8 | F69L | rtS78T | 7.143% (1/14) | S64C | rtL72V | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 9 | L98V | rtS106C | 35.71% (5/14) | F69L | rtS78T | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 10 | L110F | rtT118I | 7.143% (1/14) | L98V | rtS106C | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 11 | I113S | rtN121I | 7.143% (1/14) | L110F | rtT118I | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 12 | I126S | rtD134E | 28.57% (4/14) | I113S | rtN121I | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 13 | T131N | rtN139K | 21.43% (3/14) | I126S | rtD134E | 35.71% (5/14) |

| 14 | S143T | rtF151Y | 14.29% (2/14) | T131N | rtN139K | 21.43% (3/14) |

| 15 | G145R | rtR153Q | 14.29% (2/14) | S143T | rtF151Y | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 16 | T160K | rtK168K | 7.143% (1/14) | G145R | rtR153Q | 14.29% (2/14) |

| 17 | L176Q | rtT184I | 7.143% (1/14) | L176Q | rtT184I | 7.143% (1/14) |

| 18 | V184A | rtR192C | 7.143% (1/14) | V184A | rtR192C | 14.29% (2/14) |

| 19 | I195M | rtM204V | 14.29% (2/14) | I195M | rtM204V | 14.29% (2/14) |

| 20 | F212V | rtL220V | 28.57% (4/14) |

M198I V199V |

rtV207I | 14.29% (2/14) |

| 21 | F212L | rtF221V | 21.43% (3/14) | F212V | rtL220V | 21.43% (3/14) |

Mutations in the “a” determinant region and S gene outside the “a” determinant region are shown in italics. Underlined mutations are related to immune evasion or nucleoside analogue resistance. Bold mutations were different before and after transplantation.

HBV gene mutations in the P region after transplantation

Before transplantation only the L682M mutation was found in the glucocorticoid response element region (nt1080–nt1234 and aa664–713) of the P region in HBV, but after transplantation the number of mutations increased to include P671T, T672N, L682M, Y685-, A688T, A699V, and T704N. The result suggested that immunosuppressants could lead to multi-site amino acid mutations in this region.

Mutations in the RT sequence of the P region in HBV such as rtI169I, rtL180M, rtM204V, and rtT184I, have been associated with nucleoside analogue insensitivity, but most mutation sites were not related to drug resistance. In the P region three HBV re-infected recipients with genotype C had a LAM-resistant mutation before transplantation, while nine recipients showed multiple mutations (≥5 amino acid mutations) besides the LAM-resistant mutation after transplantation. Recipients with genotype B showed no LAM-resistant mutation before transplantation, but they did have multiple mutations (<5 amino acid mutations) after transplantation. The results suggested that HBV re-infection was related not only to mutations in the YMDD motif, but also to multi-site mutations in the glucocorticoid response element region and P region (Tables 6 and 7).

Discussion

HepG2.2.15 cells stably expressing HBV were derived from the HepG2 cell line by transfection with cloned HBV DNA. Our preliminary experiment confirmed positive expression of HBsAg and HBeAg in the supernatant of the HepG2.2.15 cell culture, as reported by Sells et al. (20). As a liver embryonic tumor cell line able to express HBV antigens and secrete complete HBV particles, the HepG2.2.15 cell line is the most appropriate cell model system for studies of HBV replication, HBV effects on hepatocellular carcinogenesis, and hepatocyte response to medication. The mechanism of HBV DNA replication is complex and unique (9), and detection of HBV DNA is the gold standard and most sensitive method for directly observing HBV infection and replication. The HBV DNA replication cycle is a continuous process that begins with cccDNA serving as a template for the transcription of pre-genomic RNA using host cell enzymes, followed by reverse transcription to minus-strand DNA, synthesis to plus-strand DNA, and then double-stranded DNA maturation to cccDNA (32).

Our in vitro studies showed that after treatment of the human hepatoma cell line HepG2.2.15 with non-toxic concentrations of MP, HBV DNA decreased in the cell culture supernatants, and the inhibitory effect was found to be MP dose-dependent. MP also inhibited the expression of intracellular cccDNA, and its inhibitory effect was closely correlated with the MP concentration, suggesting that MP could inhibit HBV replication in vitro. However, FK506 showed no inhibitory effect on HBV replication. A possible reason may be that it does not affect the mitochondrial permeability transition pore complex (MPTP), which plays a key role in the course of HBV DNA replication (4,14). Though binding with cyclophilin D prevents conformational changes of MPTP, leading to inhibitory effects on HBV replication (29), FK506 binding protein has not been determined to interfere with MPTP.

MP and FK605 could cause changes in the HBV gene sequence in our in vitro studies. Higher concentrations of MP induced more mutations at the nucleotide and amino acid levels in the S region. High concentrations of MP could also induce mutations in the “a” determinant region. Meanwhile, FK506 also induced mutations in nucleotides and amino acids in the S region, but mostly nucleotide deletions, insertions, and mutations. Amino acid mutations due to FK506 mainly occurred in the 203–221 sequence, and few mutations were observed in the “a” determinant region. MP and FK506 both induced mutations of nucleotides (rt148–170 and rt307–379, respectively), and amino acids (rt138–184 and rt354–382, respectively), in the P region, none of which were in nucleoside analogue resistance sites.

There are three open reading frames (ORF) in the S gene of HBV, designated as the pre-S1, pre-S2, and S region (5,15). The “a” determinant region of the S gene is located at the HBV genome sequence at 124–147. Mutations in this region may change the HBsAg structure and allow escape from host antibody neutralization, which would promote HBV replication (31) and re-infection in the transplanted liver (12). Chen et al. (6) reported that mutations in sequences downstream of the “a” determinant region also influence neutralization. Since the S gene and polymerase P gene overlap, mutations in the S gene may affect the polymerase gene, and vice versa (24).

This study confirmed the inhibitory effects of MP on HBV replication in vitro, while FK506 did not show the same effect. MP inhibited not only HBV DNA, but also intracellular cccDNA, and this knowledge may help guide anti-HBV treatment after transplantation. Combination therapy of MP with other types of anti-HBV medications may result in synergistic antiviral effects. In addition, understanding the effect of immunosuppressants on HBV cccDNA may provide useful approaches to screening for anti-HBV drugs. In our study, most mutation sites in the P region induced by MP were only in the glucocorticoid response element region (27), which may be one of the reasons that MP affects HBV replication in vitro. However, this idea still needs to be supported by further clinical observation and research.

Having studied the effects of MP and FK506 on HBV in vitro, we investigated the clinical relevance of the effects of immunosuppressants on HBV in vivo after liver transplantation. Patients receiving liver transplantation diagnosed with HBV-related end-stage liver disease were selected in our center for analysis of serum HBV DNA, liver histology, and HBV gene mutations. HBV re-infection was not correlated with positive histological detection of HBsAg/HBcAg pre-transplantation, but it did show a positive relationship with HBV DNA serum load before transplantation. Twenty-one (61.76%) of the selected patients were infected with genotype C, and 13 (38.24%) with genotype B. In the 14 HBV re-infected recipients, 10 had more than 1000 copies/mL of serum HBV DNA, of whom 9 were genotype C and 1 was genotype B. The difference in genotype distribution was statistically significant (p<0.05), suggesting that HBV replication was related to the genotype, and replication of genotype C was higher than that of genotype B. Each patient's genotype did not change after transplantation under immunosuppressant therapy.

Some studies have attributed mutations in the S gene to immune pressure from HBIG (8,10,19). Of the 14 HBV re-infected recipients, 7 had undetectable HBIG titers (0 IU/L). Further gene analysis of the “a” determinant region in the S gene showed mutations of T126I, N131T, and S143T, of which the 126th amino acid mutation was the most common. Mutation of the threonine at position 126 may have caused immune evasion that could not be prevented by clinical treatment with HBIG. YMDD mutations have been shown to occur in 14–39% of HBV-infected patients receiving liver transplantation (2,11), and in our clinical study this rate was 14.3% (2/14). However, there were only two patients with YMDD mutations who were re-infected, suggesting that there may be other causes of HBV re-infection after transplantation.

Other mutations outside the P gene (e.g., S gene mutation) may contribute to HBV re-infection post-transplantation. Torresi et al. (25) reported that rtT128N and rtW153Q in the P region, accompanied by gene mutations P120T and G145R in the overlapping S region, can partly recover the replication of LAM-resistant HBV. The P gene has the longest ORF, from nt230 to 1621. The starting segment overlaps C-ORF, the middle segment overlaps S-ORF, and the last segment overlaps X-ORF.

Our gene sequencing analysis of the S region showed that because of its overlap with the polymerase region ORF, mutation of nucleotides in the S region could cause synonymous and missense mutations of the corresponding amino acid, as well as missense mutations of the corresponding amino acids in the overlapping HBV polymerase P region. This missense mutation may be one of the reasons for HBV re-infection.

Our study found HBV gene mutations in recipients after liver transplantation, and the HBV quasispecies formation was related to antiviral drug and immunosuppressant treatment. After transplantation, immune status, viral quasispecies, and gene mutation would all affect the efficacy of antiviral treatments. Additionally, some patients may already have had mutations in both the S and P regions and formation of quasispecies before transplantation.

In conclusion, the effects of immunosuppressants on HBV genetic characteristics were different in vitro from those seen in vivo. The immunosuppressants showed no significant effect on the number of HBV gene mutations, but did affect the mutation sites. Thus, using immunosuppressants after liver transplantation introduces mutations in the HBV genome that make the task of inhibiting the virus more complex. HBV re-infected patients receiving long-term combined treatment with LAM and HBIG after transplantation showed not only mutation of the YMDD motif, but also multi-site mutations in the S and P genes, although it cannot be ruled out that some of these mutations were present before transplantation. These findings suggest that the HBV genotype and interactions between the S and P gene mutations should be taken into account when using regimens such as combined treatment with LAM and HBIG for prevention of HBV re-infection after transplantation. Immunosuppression plays an important role in the variations seen in the S and P regions of the HBV genome, both in vitro and in vivo, especially in re-infected patients after liver transplantation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin, China (no. 12JCZDJC25200 and 11JCZDJC27800), and the Technology Foundation of Health Bureau in Tianjin, China (no. 05KYZ24 and 2011KY11).

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Avolio AW. Nure E. Pompili M, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatitis B virus patients: long-term results of three therapeutic approaches. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1961–1964. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Ari Z. Pappo O. Zemel R. Mor E. Tur-Kaspa R. Association of lamivudine resistance in recurrent hepatitis B after liver transplantation with advanced hepatic fibrosis. Transplantation. 1999;68:232–236. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199907270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Ari Z. Daudi N. Klein A, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic resistance: longitudinal and sequential analysis of hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations in patients with lamivudine resistance after liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:151–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouchard MJ. Wang LH. Schneider RJ. Calcium signaling by HBx protein in hepatitis B virus DNA replication. Science. 2001;294:2376–2378. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5550.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budkowska A. Dubreuil P. Poynard T, et al. Anti-pre-S responses and viral clearance in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 1992;15:26–31. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YC. Delbrook K. Dealwis C. Mimms L. Mushahwar IK. Mandecki W. Discontinuous epitopes of hepatitis B surface antigen derived from a filamentous phage peptide library. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1997–2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffin CS. Mulrooney-Cousins PM. van Marle G. Roberts JP. Michalak TI. Terrault NA. Hepatitis B virus quasispecies in hepatic and extrahepatic viral reservoirs in liver transplant recipients on prophylactic therapy. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:955–962. doi: 10.1002/lt.22312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furukawa Y. Becker G. Stinn JL. Shimizu K. Libby P. Mitchell RN. Interleukin-10 augments allograft arterial disease: paradoxical effects of IL-10 in vivo. Am J Patnol. 1999;155:1929–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65512-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganem D. Varmus HE. The molecular biology of the hepatitis B viruses. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:651–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghany MG. Ayola B. Villamil FG, et al. Hepatitis B virus S mutants in liver transplant recipients who were reinfected despite hepatitis B immune globulin prophylaxis. Hepatology. 1998;27:213–222. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilic ZM. Kuran S. Akdogan M, et al. The long-term effects of lamivudine treatment in patients with HBeAg-negative liver cirrhosis. Adv Ther. 2008;25:190–200. doi: 10.1007/s12325-008-0038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KH. Lee KH. Chang HY, et al. Evolution of hepatitis B virus sequence from a liver transplant recipient with rapid breakthrough despite hepatitis B immune globulin prophylaxis and lamivudine therapy. J Med Virol. 2003;71:367–375. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramvis A. Arakawa K. Yu MC. Nogueira R. Stram DO. Kew MC. Relationship of serological subtype, basic core promoter and precore mutations to genotypes/subgenotypes of hepatitis B virus. J Med Virol. 2008;80:27–46. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee YI. Hwang JM. Im JH, et al. Human hepatitis B virus-X protein alters mitochondrial function and physiology in human liver cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15460–15471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Locarnini S. McMillan J. Bartholomeusz A. The hepatitis B virus and common mutants. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:5–20. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pourcel C. Louise A. Gervais M. Chenciner N. Dubois MF. Tiollais P. Transcription of the hepatitis B surface antigen gene in mouse cells transformed with cloned viral DNA. J Virol. 1982;42:100–105. doi: 10.1128/jvi.42.1.100-105.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenau J. Bahr MJ. Tillmann HL. Trautwein C. Klempnauer J. Manns MP. Böker KHW. Lamivudine and low-dose hepatitis B immune globulin for prophylaxis of hepatitis B reinfection after liver transplantation possible role of mutations in the YMDD motif prior to transplantation as a risk factor for reinfection. J Hepatol. 2001;34:895–902. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samuel D. Feray C. Bismuth H. Hepatitis viruses and liver transplantation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:S335–S341. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santantonio T. Gunther S. Sterneck M, et al. Liver graft infection by HBV S-gene mutants in transplant patients receiving long-term HBIg prophylaxis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1848–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sells MA. Chen ML. Acs G. Production of hepatitis B virus particles in HepG2 cells transfected with cloned hepatitis B virus DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1005–1009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.4.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi M. Zhang Y. Zhu YH. Zhang J. Xu WJ. Comparison of real-time polymerase chain reaction with the COBAS Amplicor test for quantitation of hepatitis B virus DNA in serum samples. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:479–483. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiota G. Harada K. Oyama K, et al. Severe exacerbation of hepatitis after short-term corticosteroid therapy in a patient with “latent” chronic hepatitis B. Liver. 2000;20:415–420. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020005415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinmüller T. Seehofer D. Rayes N, et al. Increasing applicability of liver transplantation for patients with hepatitis B-related liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;35:1528–1535. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torresi J. The virological and clinical significance of mutations in the overlapping envelope and polymerase genes of hepatitis B virus. J Clin Virol. 2002;25:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torresi J. Earnest-Silveira L. Deliyannis G, et al. Reduced antigenicity of the hepatitis B virus HBsAg protein arising as a consequence of sequence changes in the overlapping polymerase gene that are selected by lamivudine therapy. Virology. 2002;293:305–313. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsou PL. Lee HS. Jeng YM. Huang TS. Submassive liver necrosis in a hepatitis B carrier with Cushing's syndrome. J Formos Med Assoc. 2002;101:156–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tur-Kaspa R. Burk RD. Shaul Y. Shafritz DA. Hepatitis B virus DNA contains a glucocorticoid-responsive element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1627–1631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vierling JM. Management of HBV infection in liver transplantation patients. Int J Med Sci. 2005;2:41–49. doi: 10.7150/ijms.2.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia WL. Shen Y. Zheng SS. Inhibitory effect of cyclosporine A on hepatitis B virus replication in vitro and its possible mechanisms. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia WL. Xie HY. Shen Y. Wu LM. Zhang F. Zheng SS. Effects of ciclosporin and tacrolimus on replication of hepatitis B virus in vitro: a comparative study. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2006;86:111–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng X. Weinberger KM. Gehrke R, et al. Mutant hepatitis B virus surface antigens (HBsAg) are immunogenic but may have a changed specificity. Virology. 2004;329:454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoulim F. Antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis B: can we clear the virus and prevent drug resistance? Antivir Chem Chemother. 2004;15:299–305. doi: 10.1177/095632020401500602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]