Abstract

In animal cell lysates the multiprotein heat-shock protein 90 (hsp90)-based chaperone complexes consist of hsp70, hsp40, and p60. These complexes act to convert steroid hormone receptors to their steroid-binding state by assembling them into heterocomplexes with hsp90, p23, and one of several immunophilins. Wheat germ lysate also contains a hsp90-based chaperone system that can assemble the glucocorticoid receptor into a functional heterocomplex with hsp90. However, only two components of the heterocomplex-assembly system, hsp90 and hsp70, have thus far been identified. Recently, purified mammalian p23 preadsorbed with JJ3 antibody-protein A-Sepharose pellets was used to isolate a mammalian p23-wheat hsp90 heterocomplex from wheat germ lysate (J.K. Owens-Grillo, L.F. Stancato, K. Hoffmann, W.B. Pratt, and P. Krishna [1996] Biochemistry 35: 15249–15255). This heterocomplex was found to contain an immunophilin(s) of the FK506-binding class, as judged by binding of the radiolabeled immunosuppressant drug [3H]FK506 to the immune pellets in a specific manner. In the present study we identified the immunophilin components of this heterocomplex as FKBP73 and FKBP77, the two recently described high-molecular-weight FKBPs of wheat. In addition, we present evidence that the two FKBPs bind hsp90 via tetratricopeptide repeat domains. Our results demonstrate that binding of immunophilins to hsp90 via tetratricopeptide repeat domains is a conserved protein interaction in plants. Conservation of this protein-to-protein interaction in both plant and animal cells suggests that it is important for the biological action of the high-molecular-weight immunophilins.

Immunophilins are immunosuppressant drug-binding proteins, which, based on their affinity for two different drugs, cyclosporin A or FK506 and rapamycin, are classified as cyclophilins or FKBPs (for reviews, see Schreiber, 1991; Walsh et al., 1992). All immunophilins have peptidylprolyl isomerase activity, which suggests a role for these proteins in protein folding (Schmid, 1993). It has been demonstrated that immunophilins affect protein folding both in vitro (Bose et al., 1996; Freeman et al., 1996) and in vivo (Lodish and Kong, 1991; Steinmann et al., 1991). The high-Mr immunophilin FKBP52 is a component of the steroid-receptor complexes in mammalian cells (Pratt and Toft, 1997). The recent demonstration that the chaperone activity of FKBP52 is not affected by the presence of immunosuppressant drugs that inhibit its peptidylprolyl isomerase activity suggests that the chaperone activity of FKBP52 is independent of its peptidylprolyl isomerase activity (Bose et al., 1996).

Several lines of evidence suggest that low-Mr immunophilins such as FKBP12 and cyclophilins A and B in complex with immunosuppressant drugs inhibit the activity of calcineurin, a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase, thereby blocking the signaling pathway for T-cell activation (Liu et al., 1991; Clipstone and Crabtree, 1992). High-Mrimmunophilins such as FKBP51, FKBP52, and Cyp40 have been identified as components of steroid-receptor complexes (for reviews, see Pratt, 1997; Pratt and Toft, 1997). Although it remains to be demonstrated that these immunophilins affect receptor action or heterocomplex assembly in any way (Hutchison et al., 1993; Dittmar et al., 1996), there is some evidence to suggest that FKBP52 may play a role in trafficking of the receptor to the nucleus (Czar et al., 1995; Owens-Grillo et al., 1996a).

The high-Mr immunophilins possess a TPR domain and a calmodulin-binding domain in their C-terminal half (Callebaut et al., 1992). The TPR domains consist of 34 amino acid repeats with a degenerate consensus and are believed to be sites for protein-protein interactions (Sikorski et al., 1990). The immunophilins in steroid-receptor complexes bind to a common site on hsp90 via their TPR domains (Radanyi et al., 1994; Owens-Grillo et al., 1995). It is predicted that mammalian hsp90 has a universal TPR-domain-binding region that permits it to bind to immunophilins and other TPR-domain-containing proteins such as PP5 and the stress-related protein p60 (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996a; Silverstein et al., 1997).

Both FKBPs and cyclophilins have been identified in plants (for review, see Boston et al., 1996). Genes encoding cyclophilin homologs have been isolated from tomato, maize, oilseed rape, and Arabidopsis (Gasser et al., 1990; Hayman and Miernyk, 1994). Luan et al. (1994) isolated a high-Mr FKBP from broad bean using a FK506 affinity column. More recently, genes encoding high-Mr FKBPs were isolated from Arabidopsis (Vucich and Gasser, 1996) and wheat (Blecher et al., 1996; Kurek et al., 1999). The deduced amino acid sequences of FKBPs from both plant species show the presence of TPR motifs and a putative calmodulin-binding domain.

In a previous study we used purified p23, a component of the mammalian steroid-receptor heterocomplex, preadsorbed to JJ3 antibody to isolate a mammalian p23-wheat hsp90 heterocomplex following incubation with wheat germ lysate (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996b). The immunopurified complex bound [3H]FK506 in a specific manner, suggesting the presence of one or more FKBPs in the complex. Here we show that the two recently identified high-Mr wheat FKBPs, FKBP73 and FKBP77, are components of this complex and that they interact with hsp90 via TPR domains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Wheat germ lysate, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG were from Promega. Protein A-Sepharose was from Pharmacia, and mouse IgG1 κ (MOPC-21) clarified ascites was from Sigma. Enhanced chemiluminescence western blotting detection reagents were from Amersham. The bacterial strain expressing human p23 and the JJ3 monoclonal antibody against p23 (Johnson et al., 1994) were kindly provided by Dr. D.O. Toft (Rochester, MN). Geldanamycin was kindly provided by Dr. W.B. Pratt (Ann Arbor, MI). The source of geldanamycin was as described by Owens-Grillo et al. (1996b). The rabbit R2 antiserum (Krishna et al., 1997) was used to detect wheat hsp90, and a polyclonal antiserum against recombinant wheat FKBP73 (Blecher et al., 1996) was used for detection of FKBP73. A polyclonal antibody raised against a 24-mer peptide corresponding to amino acids 545 to 568 of wheat FKBP77 (Kurek et al., 1999) was used to detect FKBP77. The amino acid sequence between residues 545 to 568 is unique to FKBP77. As would be expected, the anti-FKBP77 antibody reacted specifically with FKBP77 and showed no cross-reactivity with FKBP73 in the western assay (I. Kurek, K. Aviezer, N. Erel, E. Herman, and A. Breiman, unpublished data).

Purification of p23

The bacterial expression of human p23 and its purification were described previously (Johnson and Toft, 1994). p23 is soluble in bacterial lysates, and its abundance and high affinity for DEAE-cellulose allowed purification to 90% by chromatography. The protein was concentrated by precipitation with ammonium sulfate at 80% saturation. It was dissolved and dialyzed into 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mm KCl, and 10% glycerol and stored at −70°C.

Preparation of Insect Cell Lysates

Sf9 cells were maintained in Grace's medium supplemented with lactalbumin hydrolysate, Yeastolate (Life Technologies), gentamicin, and 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were infected with a recombinant baculovirus expressing the FLAG epitope (DYKDDDDK)-tagged TPR domain of rat PP5 (Chen et al., 1996), at a multiplicity of infection of 3, and then incubated for 48 h at 27°C. Cells were harvested by scraping into Earle's balanced saline, washed once, suspended in 1× volume of HKD buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 25 mm KCl, and 2 mm DTT), and ruptured by Dounce homogenization. Homogenates were centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000g, and the supernatant was stored at −70°C.

p23 Immunoadsorption

The JJ3 antibody was prebound to protein A-Sepharose pellets by incubating 40 μL of a 20% slurry of protein A-Sepharose with 8 μL of ascites in 300 μL of HEG buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, and 10% glycerol) for 1 h at 4°C, followed by centrifugation and washing with additional HEG buffer. p23 was immunoadsorbed from 20 μL of purified p23 stock (1 mg/mL) by rotation for 1 h at 4°C with JJ3-protein A-Sepharose pellets. Immunoadsorbed p23 was washed once with 1 mL of HEG buffer prior to incubation with wheat germ lysate. The nonimmune protein A-Sepharose pellets were prepared similarly and incubated with p23 as described for JJ3 immunopellets.

Mammalian p23-Plant hsp90 Heterocomplex Formation

The JJ3 immunopellets containing p23 were incubated with 50 μL (or as indicated in the figure legends) of wheat germ lysate at 30°C for 30 min with resuspension of the pellets every 5 min. The immunopellets were washed three times by suspension and centrifugation in 1 mL of HEG buffer containing 100 mm KCl.

In experiments in which geldanamycin was added, wheat germ lysate was preincubated at 30°C for 10 min with DMSO or with varying concentrations of geldanamycin dissolved in DMSO, as described in the legend to Figure 4. The geldanamycin-containing lysate was then added to the immunoadsorbed p23-protein A-Sepharose pellets and incubated again for 30 min at 30°C. For examination of the effect of geldanamycin at 0°C, both preincubation and incubation were carried out at this temperature.

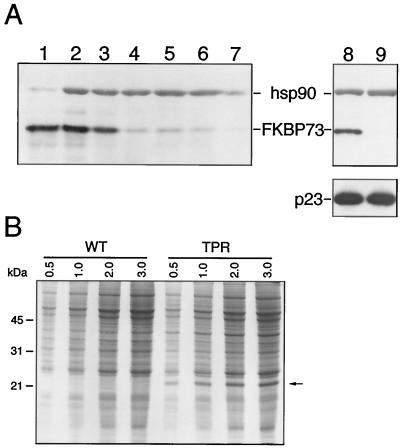

Figure 4.

Inhibition of p23-hsp90 heterocomplex formation by geldanamycin in a concentration-dependent manner. A, Protein-antibody complex visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. Lane 1, Commercial wheat germ lysate (0.25 μL). Lanes 2 through 7, Wheat germ lysate (30 μL) preincubated for 10 min at 30°C with 6 μL of DMSO (lane 2) or with geldanamycin at a concentration of 0.5 μg/mL (lane 3), 1.0 μg/mL (lane 4), 1.5 μg/mL (lane 5), 2.0 μg/mL (lane 6), or 2.5 μg/mL (lane 7) in a final volume of 6 μL of DMSO. The samples were then incubated with immunoadsorbed p23 for 30 min at 30°C. After the pellets were washed, proteins were extracted in 60 μL of SDS sample buffer, and an aliquot of 20 μL was separated on a 11% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Following transfer to nitrocellulose membrane, hsp90 and FKBP73 were detected by western blotting. Lanes 8 and 9 are results of a similar experiment in which incubation of immunoadsorbed p23 with geldanamycin (10 μg/mL) containing wheat germ lysate was at either 30°C (lane 8) or 0°C (lane 9). B, Proteins visualized by silver staining. Lanes 1 and 2 are same as lanes 8 and 9, respectively, in A.

In experiments in which binding of immunophilins to hsp90 was competed for by PP5 TPR motifs, wheat germ lysate was preincubated at 30°C for 10 min with insect cell lysate containing the expressed TPR fragment or with an equal amount of wild-type lysate (without the TPR domain). The mixture of lysates was then added to immunoadsorbed p23-protein A-Sepharose pellets and the entire sample was incubated at 30°C for 30 min.

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting

The immunoadsorbed protein A-Sepharose pellets, after three washes with HEG buffer containing 100 mm KCl, were heated in SDS sample buffer with 10% β-mercaptoethanol. The released proteins were resolved on either 7.5% or 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Laemmli, 1970) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were probed for 2 h with the R2 antibody at a dilution factor of 1:5000 to detect hsp90, JJ3 antibody at a dilution of 1:5000 to detect p23, anti-FKBP73 antibody at a dilution of 1:10,000, and anti-FKBP77 antibody at a dilution of 1:1000 to detect FKBP73 and FKBP77, respectively. The immunoblots were incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, and the protein-antibody complex was visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. For the experiment described in Figure 5, the membrane was probed with anti-FKBP77 antibody, incubated in the strip buffer (100 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, and 62.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) at 50°C for 30 min, washed twice in the same buffer, and then reprobed with the R2 antibody to detect hsp90.

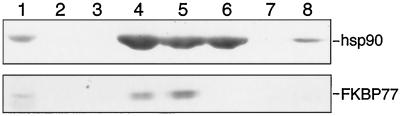

Figure 5.

FKBP77 is also a component of the mammalian p23-plant hsp90 heterocomplex. Protein A-Sepharose (50 μL) was coated with 10 μL of JJ3 ascites followed by adsorption of p23. Immunoadsorbed p23 was incubated with 50 μL of wheat germ lysate. After the pellets were washed, proteins were extracted in SDS sample buffer and separated on a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. FKBP77 was detected by western blotting. Lane 1, Wheat germ lysate; lane 2, nonimmune IgG-bound protein A-Sepharose incubated first with p23 and then with wheat germ lysate; lane 3, JJ3-bound protein A-Sepharose incubated directly with wheat germ lsyate; lane 4, JJ3-bound-protein A-Sepharose incubated first with p23 and then with wheat germ lysate; lane 5, immunoadsorbed p23 incubated with wheat germ lysate mixed with 15 μL of insect cell lysate without the TPR domain; lane 6, immunoadsorbed p23 incubated with wheat germ lysate mixed with 15 μL of insect cell lysate containing the TPR domain; lane 7, immunoadsorbed p23 incubated with wheat germ lysate in the presence of geldanamycin (10 μg/mL) at 30°C; lane 8, same as lane 7 but incubation was at 0°C.

RESULTS

Identification of a Wheat Immunophilin Coimmunoadsorbed with Human p23-Wheat hsp90 Complex

The highly acidic p23 protein is a component of steroid-receptor-hsp90 heterocomplexes (Pratt and Toft, 1997). Johnson and Toft (1994) demonstrated that immunoadsorption of p23 from rabbit reticulocyte lysate results in coisolation of hsp90 and immunophilins, including FKBP52, FKBP54, and Cyp40. Subsequently, it was shown that p23 binds directly to hsp90 through a process that requires ATP (Johnson et al., 1996). Immunophilins were shown, using purified proteins, to bind directly to a TPR-binding domain on hsp90 (Owens-Grillo et al., 1995). Although a p23 homolog has not yet been identified in plants, purified human p23 was demonstrated to form a complex with plant hsp90 following incubation with wheat germ lysate (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996b). This complex was found to contain an immunophilin(s) of the FKBP class. At that time the immunophilin(s) in the complex could not be identified any further, due in part to the unavailability of antibodies specific to plant immunophilins.

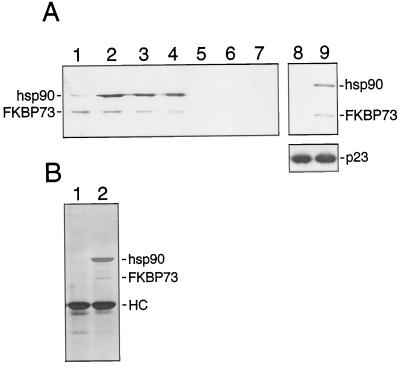

Recently, a cDNA encoding a high-Mr FKBP, FKBP73, was isolated from wheat, and a polyclonal antibody was raised to its recombinant form (Blecher et al., 1996). Since antibodies against plant hsp90 and FKBPs are not efficient for immunoadsorption, we used the previously published (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996b) indirect strategy of adding immunoadsorbed p23 to wheat germ lysate to isolate a human p23-plant hsp90 complex, and we investigated the presence of FKBP73 in this complex by immunoblotting. Incubation for 30 min at 30°C allowed complex formation between wheat hsp90 and human p23 (Fig. 1, lane 4), and the resulting complex also contained the wheat FKBP73 (Fig. 1, lane 4). Neither hsp90 nor FKBP73 were detected in the absence of p23 (Fig. 1, lane 3) or when immunoadsorption was carried out with nonimmune IgG-bound protein A-Sepharose pellets (Fig. 1, lane 2).

Figure 1.

Mammalian p23-plant hsp90-plant FKBP73 heterocomplex formation. Protein A-Sepharose (40 μL) was coated with 8 μL of JJ3 ascites followed by immunoadsorption of p23. The immunoadsorbed p23 was incubated with 30 μL of wheat germ lysate for 30 min at 30°C. After the pellets were washed, proteins were extracted in 50 μL of SDS sample buffer. Proteins (30 μL of the sample) were separated on a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting. hsp90 and FKBP73 were detected using R2 and anti-wheat FKBP73 antisera, respectively. An aliquot (7 μL) of the sample containing extracted proteins was run on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. After transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane, p23 was detected using the JJ3 antibody. Lane 1, Wheat germ lysate; lane 2, nonimmune IgG-bound protein A-Sepharose incubated first with p23 and then with wheat germ lysate; lane 3, JJ3-bound protein A-Sepharose incubated directly with wheat germ lsyate; lane 4, JJ3-bound-protein A-Sepharose incubated first with p23 and then with wheat germ lysate.

FKBP73 Binds to hsp90 via Its TPR Domain

FKBP73 contains TPR motifs (Blecher et al., 1996); therefore, we wondered whether it binds to hsp90 via its TPR motifs. Previously, Silverstein et al. (1997) showed that rat PP5 binds directly to mammalian hsp90 via TPR motifs. The TPR domain of PP5 is closely related to TPR domains of several high-Mr immunophilins known to associate with hsp90 (Chinkers, 1994). We therefore added lysate of insect cells expressing the TPR domain of PP5 to wheat germ lysate before incubating it with immunoadsorbed p23. Figure 2 shows that the addition of increasing amounts of insect cell lysate containing the TPR domain did not affect the presence of hsp90 in the heterocomplex but eliminated FKBP73. Addition of equivalent amounts of wild-type insect cell lysate (without the TPR domain) to wheat germ lysate did not affect the amount of either hsp90 or FKBP73 in the complex (data not shown). Lanes 8 and 9 of Figure 2 represent results of a similar experiment, in which it can also be seen that the addition of 20 μL of insect cell lysate without the TPR domain to wheat germ lysate had no effect on the amounts of hsp90, FKBP73, or p23 in the immune pellet (compare lane 8 of Fig. 2 with lane 4 of Fig. 1; the experiments were carried out at the same time), but the addition of lysate with the TPR domain eliminated the binding of FKBP73 to hsp90 due to competition by TPR domain (Fig. 2, lane 9). From these data we conclude that wheat FKPB73 binds to wheat hsp90 via its TPR domain.

Figure 2.

Rat PP5 TPR domain competes for wheat FKBP73 binding to wheat hsp90. A, Protein A-Sepharose beads (40 μL) were coated with 8 μL of JJ3 ascites followed by adsorption of p23. The immunoadsorbed p23 was incubated with wheat germ lysate either without addition of insect cell lysate or with addition of insect cell lysate containing the expressed rat PP5 TPR domain. After the pellets were washed, proteins were extracted in SDS sample buffer, resolved on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and analyzed for hsp90 and FKBP73 by western blotting. Lane 1, Wheat germ lysate; lane 2, immunoadsorbed p23 incubated with 30 μL of wheat germ lysate; lanes 3 to 7, immunoadsorbed p23 incubated with wheat germ lysate mixed with 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 μL, respectively, of insect cell lysate containing the expressed TPR domain; lane 8, immunoadsorbed p23 incubated with 50 μL of wheat germ lysate mixed with 20 μL of wild-type insect cell lysate without TPR domain; lane 9, immunoadsorbed p23 incubated with wheat germ lysate mixed with 20 μL of insect cell lysate containing the TPR domain. B, Insect cell lysates (0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 μL) without the TPR domain (wild type [WT]) and with the TPR domain were subjected to electrophoresis on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. The arrow indicates the expressed TPR domain of PP5 only in the lysates of cells infected with the recombinant baculovirus.

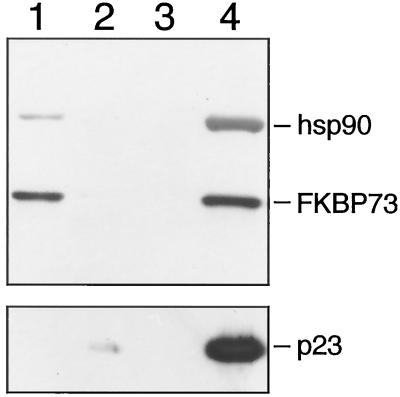

Detection of Wheat Proteins Coimmunoprecipitating with Human p23 by Silver Staining of the SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel

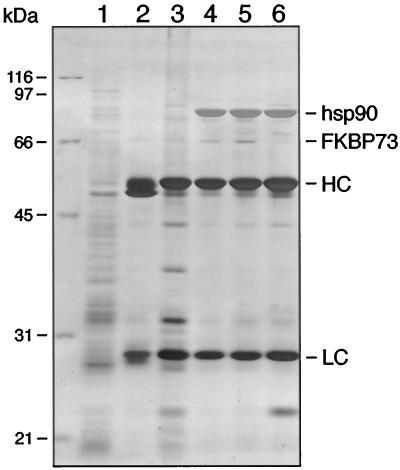

Under the experimental conditions used in the present study, two major proteins coimmunoprecipitated with p23 (Fig. 3, lane 4). These proteins were not detected in the two control lanes (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 3), suggesting that their presence was due to specific interactions within the complex. Based on their mobility on the SDS-polyacrylamide gel, these proteins were identified as hsp90 and FKBP73. Further evidence that the lower band is FKBP73 is that it was lost from the complex in the presence of insect cell lysate containing the TPR domain (Fig. 3, lane 6) but not in the presence of wild-type lysate (Fig. 3, lane 5). It is possible that additional proteins were present in this complex but were either masked by the antibody heavy chain or were not present in the quantity required for detection by silver staining.

Figure 3.

Wheat proteins coimmunoadsorbed with human p23. Samples were purified from 50 μL of wheat germ lysate using p23 immunoadsorbed with JJ3 IgG prebound to 60 μL of protein A-Sepharose. Proteins were extracted in SDS sample buffer, separated on a 11% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and visualized by silver staining of the gel. Lane 1, One microliter of wheat germ lysate; lane 2, nonimmune IgG-bound protein A-Sepharose incubated with p23 and then with wheat germ lysate; lane 3, JJ3-bound protein A-Sepharose incubated directly with wheat germ lysate; lane 4, JJ3-bound protein A-Sepharose incubated first with p23 and then with wheat germ lysate; lanes 5 and 6 are the same as lane 4 with the exception that the wheat germ lysate was mixed with 20 μL of insect cell lysate without PP5 TPR domain (lane 5) or with lysate containing the expressed TPR domain (lane 6). HC, Heavy chain; LC, light chain.

Geldanamycin Eliminates hsp90 Binding to p23, Which Is Accompanied by the Loss of FKBP73 from the Complex

Geldanamycin, a benzoquinione ansamycin, disrupts both mammalian p23-hsp90 complexes (Johnson and Toft, 1995) and mammalian p23-plant hsp90 complexes (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996b). In the latter case, the blockage of heterocomplex formation was temperature-dependent and took place after preincubation of wheat germ lysate with geldamamycin or after subsequent incubation with p23 at 30°C. Previously, it was observed that inhibition of hsp90 binding to p23 in the presence of geldanamycin was paralleled by decline of [3H]FK506 binding to the immune pellet (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996b), suggesting that the unidentified FKBP was bound to the complex through interaction with hsp90. We wanted to know whether FKBP73 would conform to this behavior. Figure 4A, lane 5, shows that geldanamycin at a concentration of 1.5 μg/mL completely inhibited the binding of hsp90 to p23. Like hsp90, FKBP73 was not detected in this sample.

In a previous study (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996b), 5 μg/mL of geldanamycin was observed to completely disrupt p23-hsp90 complexes. Since differences were observed in the immunoadsorption and western-blotting techniques in the two studies, variation in what may be the most effective concentration of geldanamycin in blocking the complex formation was not unexpected. Lanes 8 and 9 of Figure 4A represent data from a similar experiment. When the preincubation and incubation were at 0°C, hsp90 and FKBP73 were not completely eliminated from the complex (compare Fig. 4, lane 9, to Fig. 1, lane 4; the experiments were carried out at the same time), but at 30°C neither hsp90 nor FKBP73 was detected in the immune pellet (Fig. 4, lane 8). The results obtained by western blotting were further confirmed by silver staining of proteins present in the immune pellet (Fig. 4B). These data are consistent with a previous report by Owens-Grillo et al. (1996b) in that the effect of geldanamycin on plant hsp90 was temperature-dependent.

The Heat-Regulated Wheat FKBP77 Is a Component of the p23-hsp90 Heterocomplex

Recently, FKBP77 was identified in wheat as an immunophilin whose synthesis is enhanced severalfold by high-temperature stress (Kurek et al., 1999). In the absence of high temperature, the protein was present in root and shoot tips and soaked embryos of wheat, but the levels were very low. The availability of an antibody to FKBP77 allowed us to check for its presence in the p23-hsp90 heterocomplex. FKBP77 was detected in wheat germ lysate (Fig. 5, lane 1) and its presence in the p23 immune pellet paralleled that of hsp90 (Fig. 5, lane 4). FKBP77 also binds to hsp90 via its TPR domain, because the insect cell lysate with the PP5 TPR domain could successfully compete for its binding to hsp90 (Fig. 5, lane 6), but the wild-type insect cell lysate was ineffective in eliminating its binding to hsp90 (Fig. 5, lane 5). The effect of geldanamycin on hsp90 and indirectly on FKBP77 was similar to that observed for FKBP73 (Fig. 5, lanes 7 and 8).

DISCUSSION

In an earlier study the presence of FKBPs in the human p23-plant hsp90 complex was demonstrated using the radiolabeled FK506 drug-binding assay (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996b). The recent cloning of two high-Mr wheat FKBPs has allowed the generation of antibodies specific to these proteins (Blecher et al., 1997; Kurek et al., 1999). Using these antibodies in immunoblot assays, we demonstrate here that wheat FKBP73 and FKBP77 are components of the wheat hsp90 heterocomplex. Since p23 interacts specifically with hsp90 (Johnson and Toft, 1995) and does not affect the binding of immunophilins to hsp90 (W.B. Pratt, personal communication), the present data unequivocally establish that hsp90-immunophilin complexes do exist in plant cells, as has already been demonstrated for animal and yeast cells.

The high-Mr immunophilins were first discovered as part of steroid-receptor multiprotein heterocomplexes in animals (Pratt and Toft, 1997). These studies also revealed that the chaperone components of these heterocomplexes exist in cytosols as heterocomplexes independent of their association with steroid receptors and that each component has a unique function in the assembly and maturation process of steroid receptors to the steroid-binding state. The first step in the assembly process is the formation of a steroid-receptor-hsp90-p60-hsp70 complex. The p60 cycles out by an unknown mechanism, and p23 enters the complex dynamically and helps to stabilize the receptor-hsp90 heterocomplex (Pratt, 1997). Once p60 dissociates from hsp90, the immunophilin can bind to the TPR-binding domain, which p60 has vacated.

Although immunophilins were detected in steroid-receptor heterocomplexes some time ago, their specific function in these complexes remains unclear. One view is that immunophilins may play a role in targeting receptor movement to the nucleus. In support of this view, an antibody raised to a negatively charged region of FKBP52, which is electrostatically complimentary to the receptor's nuclear-localization signal, inhibited the movement of the receptor to the nucleus (Czar et al., 1995). FKBP52 has also been localized by indirect immunofluorescence to the nucleus (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996a), supporting the idea that immunophilins participate in the targeted movement of the complexes.

The other view is that immunophilins take part in the protein-folding process. Recently, it was shown through in vitro protein-folding assays that FKBP52 can efficiently suppress the aggregation of citrate synthase and promote reactivation of unfolded citrate synthase by stabilizing folding-competent intermediates (Bose et al., 1996). These data define FKBP52 as a molecular chaperone. However, a chaperone function for immunophilins in the assembly process of the steroid-receptor heterocomplex has not yet been described. In fact, receptor heterocomplexes have been assembled with purified proteins in the absence of immunophilins (Dittmar et al., 1996). Although immunophilins appear to be linked with protein targeting in receptor heterocomplexes, the possibility that they have a specific role in protein folding cannot be ruled out at this point. The observations that the abundance of ROF1 (the Arabidopsis homolog of FKBP59) mRNA is increased severalfold under stress conditions such as wounding or exposure to high salt concentrations (Vucich and Gasser, 1996), that wheat FKBP73 is expressed at higher levels in young tissues (Blecher et al., 1996), and that wheat FKBP77 accumulates to higher levels in response to high-temperature stress (I. Kurek, K. Aviezer, N. Erel, E. Herman, and A. Breiman, unpublished data) together suggest that high-Mr FKBPs may have a role in protein folding.

The identification of FKBP73 and FKBP77 in hsp90 heterocomplexes has produced a number of questions: What are the other components of these heterocomplexes? What are the plant proteins analogous to steroid receptors that are chaperoned by hsp90-immunophilin heterocomplexes? What are the specific functions of immunophilins within these complexes?

Prior to demonstrating the presence of hsp90-immunophilin complexes in plant cells (Owens-Grillo et al., 1996b; present study), studies of cell-free assembly of receptor-hsp90 complexes revealed that the assembly process is conserved in animal and plant cell lysates (Stancato et al., 1996), that purified plant hsp90 and hsp70 proteins have the conserved ability to interact functionally with chaperone proteins of the animal kingdom (Stancato et al., 1996), and that purified human p23 added to wheat germ lysate can stabilize the receptor-plant hsp90 heterocomplex formed in wheat germ lysate (Hutchison et al., 1995). All of these findings attest to the conserved nature of the chaperone complex in animals and plants. On the basis of these findings it can be speculated that functions of immunophilins, in a general sense, may also be conserved in animal and plant cells.

A p23 homolog has not yet been identified in plants; however, a stress-inducible gene encoding a protein with high homology to p60 has been isolated from soybean (Torres et al., 1995). Whether the plant p60 homolog occupies the same site on hsp90 as the immunophilins remains to be determined. The identification of FKBP73 and FKBP77 as components of the hsp90 heterocomplex will allow such questions to be answered in the future through reconstitution of heterocomplexes with purified proteins.

We have shown that in the presence of geldanamycin, which disrupts the hsp90-p23 heterocomplex, FKBP73 and FKBP77 were eliminated from the heterocomplex. Recently, geldanamycin was demonstrated to inhibit steroid-dependent translocation of the glucocorticoid receptor from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Czar et al., 1997). Because geldanamycin blocks the assembly of the receptor-hsp90 heterocomplex at an intermediate state, this suggests that dynamic association of receptors with hsp90 is required for receptor translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. According to the model proposed by Owens-Grillo et al. (1996a), the immunophilin component that binds to the complex via hsp90 would be absent, resulting in the inability of the receptor to translocate to the nucleus. The fact that geldanamycin interacts with plant hsp90 in a manner similar to that of animal hsp90 suggests that it will prove useful in the future for dissecting the functions of plant chaperone proteins within the heterocomplex.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. W.B. Pratt for many useful discussions and for providing geldanamycin and Dr. D.O. Toft for providing Escherichia coli-expressing human p23 and JJ3 antibody.

Abbreviations:

- FKBP

FK506-binding protein(s)

- hsp

heat-shock protein

- PP5

protein phosphatase 5

- TPR

tetratricopeptide repeat

Footnotes

This work was supported by a research grant to P.K. by the National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada, by a research grant to A.B. from the Israeli National Academy of Science, and by a National Institutes of Health grant to M.C. (no. HL47063).

LITERATURE CITED

- Blecher O, Erel N, Callebaut I, Aviezer K, Breiman A. A novel plant peptidylprolyl-cis-trans-isomerase (PPIase): cDNA cloning, structural analysis, enzymatic activity and expression. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:493–504. doi: 10.1007/BF00019101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose S, Weikl T, Bugl H, Buchner J. Chaperone function of hsp90-associated proteins. Science. 1996;274:1715–1717. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boston RS, Viitanen PV, Vierling E. Molecular chaperones and protein folding in plants. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:191–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00039383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut I, Renoir JM, Lebeau MC, Massol N, Burny A, Baulieu EE, Mornon JP. An immunophilin that binds Mr 90,000 heat shock protein: main structural features of a mammalian p59 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6270–6274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M-S, Silverstein AM, Pratt WB, Chinkers M. The tetratricopeptide repeat domain of protein phosphatase 5 mediates binding to glucocorticoid receptor heterocomplexes and acts as a dominant negative mutant. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32315–32320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkers M. Targeting of a distinctive protein-serine phosphatase to the protein kinase-like domain of the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11075–11079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clipstone NA, Crabtree GR. Identification of calcineurin as a key signalling enzyme in T-lymphocyte activation. Nature. 1992;357:695–697. doi: 10.1038/357695a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czar MJ, Galigniana MD, Silverstein AM, Pratt WB. Geldanamycin, a heat shock protein 90-binding benzoquinone ansamycin, inhibits steroid-dependent translocation of the glucocorticoid receptor from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7776–7785. doi: 10.1021/bi970648x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czar MJ, Lyons RH, Welsh MJ, Renoir JM, Pratt WB. Evidence that the FK506-binding immunophilin heat shock protein 56 is required for trafficking of the glucocorticoid receptor from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:1549–1560. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.11.8584032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar KD, Hutchison KA, Owens-Grillo JK, Pratt WB. Reconstitution of the steroid receptor-hsp90 heterocomplex assembly system of rabbit reticulocyte lysate. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12833–12839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman BC, Toft DO, Morimoto RI. Molecular chaperone machines: chaperone activities of the cyclophilin Cyp-40 and the steroid aporeceptor-associated protein p23. Science. 1996;274:1718–1720. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser CS, Gunning DA, Budelier KA, Brown SM. Structure and expression of cytosolic cyclophilin/peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase of higher plants and production of active tomato cyclophilin in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9519–9523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman GT, Miernyk JA. The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of a peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1219:536–538. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KA, Scherrer LC, Czar MJ, Ning Y, Sanchez ER, Leach KL, Diebel MR, Pratt WB. FK506 binding to the 56-kilodalton immunophilin (hsp56) in the glucocorticoid receptor heterocomplex has no effect on receptor folding or function. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3953–3957. doi: 10.1021/bi00066a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KA, Stancato LF, Owens-Grillo JK, Johnson JL, Krishna P, Toft DO, Pratt WB. The 23-kDa acidic protein in reticulocyte lysate is the weakly bound component of the hsp foldosome that is required for assembly of the glucocorticoid receptor into a functional heterocomplex with hsp90. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18841–18847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Corbisier R, Stensgard B, Toft DO. The involvement of p23, hsp90, and immunophilins in the assembly of progesterone receptor complexes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;56:31–37. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Beito TG, Krco CJ, Toft DO. Characterization of a novel 23- kilodalton protein of unactive progesterone receptor complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1956–1963. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Toft DO. A novel chaperone complex for steroid receptors involving heat shock proteins, immunophilins, and p23. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24989–24993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Toft DO. Binding of p23 and hsp90 during assembly with the progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:670–678. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.6.8592513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna P, Reddy RK, Sacco M, Frappier JRH, Felsheim RF. Analysis of the native forms of the 90 kDa heat shock protein (hsp90) in plant cytosolic extracts. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;33:457–466. doi: 10.1023/a:1005709308096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurek I, Aviezer K, Erel N, Herman E, Breiman A (1999) The wheat peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerase FKBP77 is heat induced and developmentally regulated. Plant Physiol 119: (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Farmer JD, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell. 1991;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodish HF, Kong N. Cyclosporin A inhibits an initial step in folding of transferrin within the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14835–14838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan S, Albers MW, Schreiber SL. Light-regulated, tissue-specific immunophilins in higher plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:984–988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens-Grillo JK, Czar MJ, Hutchison KA, Hoffmann K, Perdew GH, Pratt WB. A model of protein targeting mediated by immunophilins and other proteins that bind to hsp90 via tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domains. J Biol Chem. 1996a;271:13468–13475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens-Grillo JK, Hoffmann K, Hutchison KA, Yem AW, Deibel MR, Handschumacher RE, Pratt WB. The cyclosporin A-binding immunophilin CyP-40 and the FK506-binding immunophilin hsp56 bind to a common site on hsp90 and exist in independent cytosolic heterocomplexes with the untransformed glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20479–20484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens-Grillo JK, Stancato LF, Hoffmann K, Pratt WB, Krishna P. Binding of immunophilins to the 90 kDa heat shock protein (hsp90) via a tetratricopeptide repeat domain is a conserved protein interaction in plants. Biochemistry. 1996b;35:15249–15255. doi: 10.1021/bi9615349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB. The role of the hsp90-based chaperone system in signal transduction by nuclear receptors and receptors signaling via MAP kinase. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:297–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Toft DO. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocrine Rev. 1997;18:306–360. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radanyi C, Chambraud B, Baulieu EE. The ability of the immunophilin FKBP59-HB1 to interact with the 90-kDa heat shock protein is encoded by its tetratricopeptide repeat domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11197–11201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid FX. Prolyl isomerase: enzymatic catalysis of slow protein folding reactions. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1993;22:123–143. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.22.060193.001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber SL. Chemistry and biology of the immunophilins and their immunosuppressive ligands. Science. 1991;251:283–287. doi: 10.1126/science.1702904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski RS, Boguski MS, Goebl M, Hieter P. A repeating amino acid motif in CDC23 defines a family of proteins and a new relationship among genes required for mitosis and RNA synthesis. Cell. 1990;60:307–317. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90745-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein AM, Galigniana MD, Chen M-S, Owens-Grillo JK, Chinkers M, Pratt WB. Protein phosphatase 5 is a major component of glucocorticoid receptor.hsp90 complexes with properties of an FK506-binding immunophilin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16224–16230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancato LF, Hutchison KA, Krishna P, Pratt WB. Animal and plant cell lysates share a conserved chaperone system that assembles the glucocorticoid receptor into a functional heterocomplex with hsp90. Biochemistry. 1996;35:554–561. doi: 10.1021/bi9511649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann B, Bruckner P, Superti-Furga A. Cyclosporin A slows collagen triple-helix formation in vivo: indirect evidence for a physiologic role of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1299–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JH, Chantellard P, Stutz E. Isolation and characterization of gmsti, a stress-inducible gene from soybean (Glycine max) coding for a protein belonging to the TPR (tetratricopeptide repeats) family. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:1221–1226. doi: 10.1007/BF00020896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vucich VA, Gasser CS. Novel structure of a high molecular weight FK506 binding protein from Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:510–517. doi: 10.1007/BF02172397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CT, Zydowsky LD, McKeon FD. Cyclosporin A, the cyclophilin class of peptidylprolyl isomerases, and blockade of T cell signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13115–13118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]