Abstract

Activation of vagal afferent sensory C-fibres in the lungs leads to reflex responses that produce many of the symptoms associated with airway allergy. There are two subtypes of respiratory C-fibres whose cell bodies reside within two distinct ganglia, the nodose and jugular, and whose properties allow for differing responses to stimuli. We here used extracellular recording of action potentials in an ex vivo isolated, perfused lung-nerve preparation to study the electrical activity of nodose C-fibres in response to bronchoconstriction. We found that treatment with both histamine and methacholine caused strong increases in tracheal perfusion pressure that were accompanied by action potential discharge in nodose, but not in jugular C-fibres. Both the increase in tracheal perfusion pressure and action potential discharge in response to histamine were significantly reduced by functionally antagonizing the smooth muscle contraction with isoproterenol, or by blocking myosin light chain kinase with ML-7. We further found that pretreatment with AF-353 or 2’,3’-O-(2,4,6-Trinitrophenyl)-adenosine-5’-triphosphate (TNP-ATP), structurally distinct P2X3 and P2X2/3 purinoceptor antagonists, blocked the bronchoconstriction-induced nodose C-fibre discharge. Likewise, treatment with the ATPase apyrase, in the presence of the adenosine A1 and A2 receptor antagonists 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) and SCH 58261, blocked the C-fibre response to histamine, without inhibiting the bronchoconstriction. These results suggest that ATP released within the tissues in response to bronchoconstriction plays a pivotal role in the mechanical activation of nodose C-fibres.

Key points

Activation of bronchopulmonary C-fibres can lead to parasympathetic reflex bronchoconstriction, mucus secretion, as well as sensations of dyspnea and urge-to-cough.

We show here that a subset of bronchopulmonary C-fibres innervating the airways is stimulated when airways are exposed to either histamine or methacholine.

We provide evidence that supports the hypothesis that the C-fibre activation is secondary to bronchoconstriction and the consequential release of ATP. It is the released ATP that then stimulates the C-fibres.

This provides a mechanism by which bronchoconstriction itself can lead to certain sensations, as well as parasympathetic reflexes. Dysregulation of this process could contribute to symptoms of airway inflammatory diseases

Introduction

Vagal bronchopulmonary C-fibres are the predominant type of afferent nerve innervating the respiratory tract (Agostoni et al. 1957). They are activated by environmental irritants as well as numerous endogenous chemical mediators, particularly those associated with inflammation (Coleridge & Coleridge, 1984). When stimuli known to activate C-fibres are applied to the respiratory tract, increases in parasympathetic reflexes (bronchoconstriction and mucus secretion), changes in breathing pattern, and sensations of dyspnoea and urge to cough can occur (Coleridge & Coleridge, 1984).

Previous investigation has identified two subtypes of vagal C-fibres innervating the respiratory tract. The subtypes of C-fibres have been based either on the location of the terminals (Coleridge & Coleridge, 1984) or the location of their cell bodies (Undem et al. 2004). Those C-fibres terminating at sites more accessible to chemical stimuli added to the systemic (bronchial) circulation are termed ‘bronchial C-fibres’ and those more accessible to stimuli added to the pulmonary circulation are termed ‘pulmonary C-fibres’. An alternative characterization scheme is based on whether the C-fibres, regardless of their site of termination, arise from neurons situated in the neural crest-derived vagal jugular ganglia, versus the epibranchial placode-derived nodose ganglia (Undem et al. 2004).

In the guinea pig, the jugular and nodose C-fibres respond identically to capsaicin and other TRPV1 activators (Undem et al. 2004), as well as to bradykinin (Fox et al. 1993; Kajekar et al. 1999), but respond differently to other stimuli. For example, the nodose C-fibres respond strongly to adenosine, serotonin and ATP, whereas the jugular C-fibres are unresponsive to these autacoids. The activation of nodose C-fibres by these autacoids is due to the fact they express adenosine A1 and A2A receptors, 5-HT3 receptors and purinergic P2X2/3 receptors, respectively (Chuaychoo et al. 2005, 2006).

Bronchopulmonary C-fibres are only modestly responsive to mechanical stimulation. However, responses to mechanical stimuli such as lung inflation can be enhanced by inflammatory mediators (Lee & Morton, 1993; Mutoh et al. 1999; Ho et al. 2000). Several autacoids that cause bronchoconstriction in laboratory animals also cause C-fibre stimulation, including histamine, PGF2a, thromboxane A2, serotonin, bradykinin and substance P (Kaufman et al. 1980; Karla et al. 1992; Mohammed et al. 1993; Schelegle et al. 2000; Chuaychoo et al. 2005; Bergren, 2006). The mechanism of afferent activation may be due to direct effects on the nerves, but it is possible that in some cases the activation is partially or completely secondary to the evoked bronchoconstriction, or any associated pulmonary vascular effects.

Inasmuch as vagal C-fibres, like the C-fibres in the somatosensory system, have evolved to respond to an array of disparate endogenous chemical mediators, we addressed the hypothesis that there is a chemical intermediate in the mechanical activation of respiratory C-fibres caused by bronchoconstricting mediators. In particular we provide evidence that bronchial smooth muscle contraction leads to mechanical activation of nodose, but not jugular, bronchopulmonary C-fibres, and that this is dependent on ATP release and its subsequent interaction with P2X2/3 receptors at the C-fibre terminal.

Methods

Ethical approval

All experimental protocols were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Extracellular recording of action potential discharge

Male Hartley guinea pigs (100–200 g; Hilltop Laboratory Animals, Inc., Scottsdale, PA, USA) were injected with heparin (2000 IU kg−1 in saline solution). After 20 min, animals were killed by an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1 delivered i.p.). The chest was opened and blood was flushed from the pulmonary circulation in situ with Krebs–Ringer–bicarbonate solution (KRBS) composed of (in mm): 118 sodium chloride, 5.4 KCl, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.9 CaCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 11.1 glucose equilibrated with 95% O2–5% CO2 (pH 7.4). The trachea and right lungs were dissected out with their intrinsic vagal innervation, including the nodose and jugular ganglia, intact, and pinned out in a two-compartment tissue bath with the portion of the vagus nerve containing the ganglia extended into a separate chamber from that containing the lungs and trachea. The two compartments were separately perfused with KRBS (flow rate 6 ml min−1, 37°C), and the trachea and pulmonary artery were cannulated with PE tubing, and continuously perfused with warmed, equilibrated KRBS (flow rate 4 ml min−1 and 2 ml min−1, respectively). Perfusate was allowed to exit the lungs via the pulmonary veins and through 10 ports created by puncturing each lobe 10 times with a 30-gauge dissecting pin. Tracheal perfusion pressure (PTr) was measured as a surrogate for smooth muscle contraction via a pressure transducer (P23AA, Stratham, Hata Rey, PR, USA) placed in the tracheal line, and recorded on a chart recorder (TA240, Gould, Valley View, OH, USA).

After 30–60 min of equilibration, the nodose or jugular ganglion, visualized through a dissecting scope, was impaled with a borosilicate glass microelectrode pulled on a micropipette puller (model P87, Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA, USA) and filled with 3 m sodium chloride solution (resistance ∼2 MΩ). A mechanically sensitive receptive field innervated by a cell body near to the tip of the electrode was located by gently probing the surface of the lungs with a Von Frey filament (1800–3000 mN) until a burst of action potentials was elicited. The signal was amplified (Microelectrode AC Amplifier 1800, A-M Systems, Everett, WA, USA), filtered (low cut off 0.3 kHz, high cut off 1 kHz) and displayed on an oscilloscope (TDS 340, Techtronix, Beaverton, OR, USA) and a chart recorder (TA240), and recorded (sampling frequency 33 kHz) onto a MacIntosh computer for offline analysis (The NerveOfIt software, PHOCIS, Baltimore, MD, USA). The mechanically sensitive receptive field was then stimulated electrically by delivering a brief (<1 ms) pulse by a small concentric electrode positioned over the discrete receptive field. The conduction velocity of each fibre studied was calculated by dividing the distance between the electrode and the receptive field by the time delay between the shock artifact and the action potential elicited by this stimulus. In nearly all of the experiments conducted, a single neuron was studied; however, on the few occasions when more than one fibre was identified in a single preparation and studied simultaneously, wave analysis software (NerveOfIt, PHOCIS) was used to distinguish between signals generated by distinct neurons as previously described.

Based on previously established criteria for the classification of C-fibres in this model (Ricco et al. 1996; Undem et al. 2004), nerve fibres with conduction velocities of <1 m s−1, and that responded with action potential discharge to capsaicin (1 μm) administered at the end of each experiment were considered to be C-fibres and included for analysis in this study.

Tissues were exposed to ATP (100 μm), histamine (30 μm), or methacholine (10 μm) diluted to its final concentration in KRBS via a 1 ml simultaneous infusion into the trachea and the pulmonary artery at a rate of ∼50 μl s−1. One C-fibre was studied per animal. Multiple stimuli were studied on a given C-fibre, with at least a 45 min interval allowed between stimulations. The C-fibres did not desensitize over the course of multiple treatments with either ATP or histamine. The total number of action potentials evoked by the first and second treatment with histamine averaged 151 ± 27 and 213 ± 43 (P > 0.1, n = 3). The total number of action potentials evoked by the first and second ATP treatment averaged 186 ± 48 and 183 ± 20, respectively (P > 0.1, n = 3). The agonist challenge was repeated in the presence or absence of either pyrilamine (1 μm), AF-353 (100 μm), 2’,3’-O-(2,4,6-Trinitrophenyl)-adenosine-5’-triphosphate (TNP-ATP) (30 μm), ML-7 (30 μm), isoproterenol (100 μm), or apyrase (5 U ml−1), the latter agent studies with and without concomitant exposure to 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) (100 nm) and SCH 58261 (100 nm). Antagonists were infused into the trachea and pulmonary artery for a period of 15–20 min depending on the agent used, prior to the second application of the agonist(s). None of the antagonists elicited action potential discharge on its own.

A fibre was considered unresponsive to an agonist if it failed to evoke a response (less than twofold increase of action potential frequency or number over baseline), but a capsaicin response (positive control) could be obtained.

Retrograde labelling of vagal neurons innervating the lungs

A retrograde dye was used to label vagal neurons innervating the lungs. Briefly, male Hartley guinea pigs (150–200 g; Hilltop Laboratory Animals, Inc., Scottsdale, PA, USA) were anaesthetized with xylazine (2.5 mg ml−1) and ketamine (50 mg ml−1) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and a tracheostomy was performed. With the head and thorax of the animal elevated, the fluorescent tracer DiI (1% solution in DMSO then diluted 1:10 in DMSO) was instilled into the lungs via tracheal injection using a tuberculin syringe with a bent-tip needle angled caudally to allow delivery of the dye to occur just rostral to the carina. The incision was sutured closed, and the animal was allowed 2 weeks recovery time for sufficient labelling of the cell bodies within the vagal ganglia. During the postoperative period, animals were closely monitored for signs of excessive pain or infection. Animals exhibiting symptoms of undue distress were immediately euthanized.

Cell dissociation of vagal ganglia

Fourteen days post-injection, animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation. Blood was flushed from the circulation via in situ perfusion with KRBS (composition listed above). The nodose and jugular ganglia were harvested and incubated in separate tubes containing enzyme solution (2 mg ml−1 collagenase, 2 mg ml−1 dispase II dissolved in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hank's balanced salt solution) for 30 min in a 37°C water bath. Cells were then dissociated by gentle trituration with a glass fire-polished Pasteur pipette. Two more 20 min incubations in the enzyme solution at 37°C were performed, each followed by trituration with pipettes of decreasing bore size. Cells were then alternately washed in L-15 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and centrifuged (1000 g for 2 min) three times, and then resuspended in L-15 medium (10% FBS). The cell suspension was transferred to coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine (0.1 mg ml−1) and laminin (0.004 mg ml−1). Cells were placed in a 37°C incubator for 2 h to allow for adherence to the coverslips after which they were flooded with L-15 medium (10% FBS).

Individual coverslips containing DiI-labelled, dissociated nodose or jugular ganglia neurons were mounted on a fluorescence microscope and constantly perfused with KRBS equilibrated with 95% O2–5% CO2. Single lung-labelled nodose or jugular neurons were identified by fluorescence microscopy, and gently drawn by negative pressure into the tip of a glass microelectrode (tip diameter 50–150 μm) pulled with a micropipette puller (model P-87, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA). The pipette tip containing a single labelled nodose or jugular neuron was broken off into a PCR tube containing 1 μl of Invitrogen resuspension buffer and RNase inhibitor (2 U μl−1 RNaseOUT) and placed on dry ice. One to four cells were collected from each coverslip, and each cell was placed in an individual PCR tube. All cells processed for single cell RT-PCR were ‘picked’ within 8 h of harvesting the ganglia from the killed animal. Once all coverslips were processed, tubes containing the cells were stored at –80°C until RT-PCR analysis was performed.

Single cell RT-PCR

Single cells were processed using the Superscript Cells Direct III cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were thawed and each cell was lysed by the addition of 10 μl of resuspension buffer (75°C for 10 min), and then treated for 5 min at room temperature with 5 μl of DNase I and 1.6 μl of 10× DNase I buffer. Next, 1.2 μl of 25 mm EDTA was added to each tube and incubated at 70°C for 5 min, after which 1 μl each of random primers (Invitrogen), oligo(dT), and 10 mm dNTP mix was added to each sample and incubated again at 70°C for 5 min. Finally, 5× RT buffer (5 μl), RNaseOUT (1 μl), and 0.1 m DTT (1 μl) were added to each tube, and one-third of the total volume of each sample was aliquoted into a separate individual tube. Each two-thirds portion was reverse transcribed by adding Superscript III reverse transcriptase (1 μl) for cDNA synthesis. Each one-third portion contained water in place of reverse transcriptase, thus serving as a negative RT control. All samples were placed in a thermocycler preheated to 50°C for 50 min, with an inactivation step set at 85°C for 5 min. The reaction was chilled at 4°C, and cDNA was stored at –20°C until PCR amplification.

PCR amplification was carried out using 0.5 units of HotStar Taq polymerase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) with 2.5 mm MgCl2, PCR buffer, 10 mm dNTP, custom primers for β-actin, TRPV1, and the muscarinic M3 receptor (Table 1), as well as template (cDNA, negative-RT control, and water control). RNA isolated from guinea pig trachealis muscle using the RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Omniscript RT kit was assayed as a positive control. After an initial activation step of 95°C for 15 min, amplification was carried out by 50 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 30 s), annealing (60°C for 30 s), and extension (72°C for 1 min), followed by a final extension (72°C for 10 min). All products (β-actin, TRPV1, M3) could be consistently amplified from cDNA isolated from guinea pig trachealis muscle and whole nodose ganglia. Products were visualized in ethidium bromide-stained 1.5% agarose gel.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for single cell RT-PCR

| M3 | Forward | TAC ACA GCC CAT CAG AAG CA | 175 bp |

| Reverse | GCC AAG AAG CCC GTT AAG A | ||

| TRPV1 | Forward | CCA ACA AGA AGG GGT TCA CA | 168 bp |

| Reverse | ACA GGT CAT AGA GCG AGG AG | ||

| β-Actin | Forward | TGG CTA CAG TTT CAC CAC CA | 212 bp |

| Reverse | GGA AGG AGG GCT GGA AGA |

*Forward primers are listed in the 5′ to 3′ direction and reverse primers are listed from 3′ to 5′.

Drugs, solutions and concentrations

The compounds used were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA) except for AF-353, which was generously provided by Afferent Pharmaceuticals, Palo Alto San Mateo, CA, USA. ATP magnesium salt, histamine, pyrilamine, and TNP-ATP, pirenzepine and 1,1-dimethyl-4-diphenylactoxypiperidinium iodide (4-DAMP) were made up as concentrated stock solutions (1 mm to 1 m) in diH20, aliquoted and stored at –20°C. A stock solution of ML-7 was prepared in a 1:1 dilution of diH2O and ethanol, and stored at –20°C. AF-353, DPCPX and SCH 58261 were made as stock solutions in DMSO, aliquoted and stored at –20°C. On the day of the experiment, working solutions were prepared from stock in warmed, oxygenated KRBS. Apyrase was diluted directly to its working concentration in KRBS on the day of the experiment.

L-15 medium, Ca2+-, Mg2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution, and FBS were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). DiI was obtained from Molecular Probes/Invitrogen (Eugene, OR, USA). Dispase II and collagenase were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

The concentrations of the 1 ml solution of methacholine and histamine studied were selected to provide ∼75% response based on preliminary data. The concentration of the selective histamine H1 receptor antagonist pyrilamine (also known as mepyramine) and the selective anti-muscarinic drugs used were chosen, based on published pA2 values, to provide approximately 3-log rightward shift in the respective agonist concentration–response, and therefore abolish the response to the submaximally effective concentration of the agonist. The concentrations of the P2X receptor antagonists and apyrase chosen were based on a preliminary analysis of the concentration required to nearly abolish the response to 1 ml of 100 μm ATP. The concentrations of the adenosine receptor antagonists were based on our previous study (Chuaychoo et al. 2006).

Data analysis

All agonist-evoked activity was recorded in 1 s bins and analysed off-line. A response (greater than two times the baseline activity) was considered to have terminated when recorded activity returned to threshold level (≤2 times baseline activity). The total number of action potentials and the maximum number of impulses per second (peak frequency) above baseline were counted from fibres that responded. All data are presented as means ± SEM. Sample means were compared using Student's t test for two means, paired or unpaired, as experimental parameters indicated. Control and experimental mean values were considered to differ significantly if P < 0.05.

Results

Histamine evokes action potential discharge in nodose, but not jugular C-fibres

The conduction velocities of nodose and jugular C-fibres averaged 0.8 ± 0.02 m s−1 (n = 48) and 0.9 ± 0.03 m s−1 (n = 7), respectively. The nodose and jugular C-fibres studied responded similarly to capsaicin with peak frequencies (maximum impulses per second) of action potential discharge averaging 17 ± 3 (n = 15) and 16 ± 3 Hz (n = 7), respectively (P > 0.1). Background activity was generally present in the nodose C-fibres averaging 1.1 ± 0.2 Hz (see traces in Figs 1 and 3).

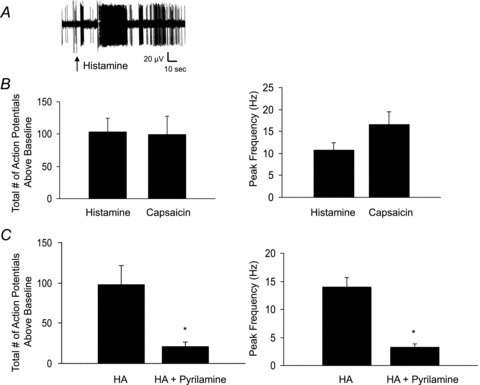

Figure 1. Response of intrapulmonary nodose C-fibres to histamine and caspsaicin.

Single nodose C-fibres were exposed to histamine (30 μm) or capsaicin (1 μm) via a 1 ml bolus simultaneously injected into the trachea and pulmonary artery. A, a recording of action potential discharge of a nodose C-fibre in response to histamine. Arrow indicates onset of histamine injection. B, the average histamine-induced action potential discharge over baseline in 15 nodose C-fibres. Average total number of action potentials generated (left) and peak frequency of action potential discharge above baseline (right) in response to histamine or the TRPV1 receptor agonist capsaicin. Data are means ± SEM, n = 15. C, the response to histamine (1 ml, 30 μm) before and after the tissues were pretreated with pyrilamine (1 μm for 15 min). The data represent the mean ± SEM of 4 experients, *P < 0.05.

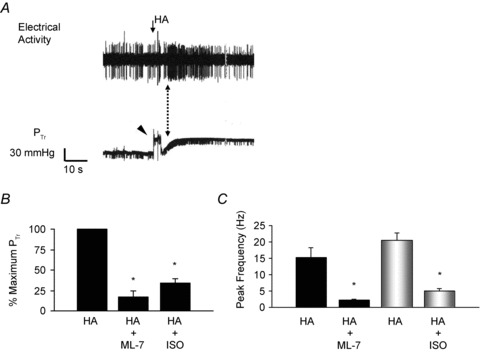

Figure 3. Histamine-induced increases in tracheal perfusion pressure and action potential discharge are blocked by antagonists of airway smooth muscle contraction.

A, simultaneous recording of histamine-induced action potential discharge and tracheal perfusion pressure in a single nodose C-fibre. The dotted arrow indicates the robust increase in action potential discharge during the dynamic phase of the tracheal pressure increase. Arrow indicates onset of histamine injection. Arrowhead indicates the pressure artifact generated during histamine infusion. The peak histamine-induced increase in PTr averaged 30.1 ± 6.2 mmHg (n = 10). B, the average histamine-induced increase in tracheal pressure (PTr) as a percentage of the maximum response after perfusion with the myosin light chain kinase inhibitor ML-7 (30 μm) or the β-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol (ISO, 100 μm). C, the average peak frequency of action potential discharge in response to histamine before and after 20 min of perfusion with ML-7 (30 μm; n = 5) or isoproterenol (100 μm, n = 5). Neither ML-7 nor isoproterenol inhibited ATP-induced activation of these C-fibres.

Nodose C-fibres in guinea pig lungs are strongly activated by ATP via P2X2/3 receptors (Kwong et al. 2008). In our ex vivo preparation, the majority of intrapulmonary nodose C-fibres are activated by ATP administered via the trachea, whereas a minority of nodose C-fibres are situated in the lungs such that they are preferentially activated by ATP delivered via the pulmonary artery, but not trachea. We found that 15 of 22 nodose C-fibres studied responded robustly to ATP delivered via the trachea. The remaining seven C-fibres that were studied responded preferentially to ATP via the pulmonary artery. Each of the 15 nodose C-fibres accessible to ATP via the trachea responded strongly to histamine. Infusing 1 ml of 30 μm histamine evoked robust action potential discharge (peak frequency 10 ± 2 Hz; total action potentials 104 ± 21, n = 15). This response commenced ∼1.5 s after the onset of administration and persisted for an average of 18 ± 3 s, after which action potential discharge either ceased, or decreased to a frequency within 2 times baseline activity (see example in Fig. 1). Of the seven fibres that were situated such that the pulmonary artery was the activating route of administration, only one was activated in response to histamine (>3 Hz, peak frequency). All the studies below were carried out on nodose C-fibres accessible via the tracheal administration of ATP.

In contrast to nodose C-fibres, jugular C-fibres were either unaffected or only very modestly stimulated by histamine (30 μm). In seven experiments the total number of action potentials evoked by histamine averaged only 16 ± 4 (data not shown); these fibres all responded strongly to capsaicin, with the average total number of action potentials generated and the peak frequency of action potential discharge above baseline measuring 105 ± 20 and 16 ± 3 Hz, respectively.

H1 receptor antagonism inhibits histamine-induced action potential discharge in nodose C-fibres

In four paired experiments, the histamine H1 receptor antagonist pyrilamine (1 μm) significantly inhibited histamine-induced action potential discharge in nodose C-fibres (Fig. 1), reducing the mean total number of action potentials generated from 98 ± 24 to 21 ± 6 (P < 0.05), as well as the peak frequency of action potentials from 14 ± 2 Hz to 3 ± 1 Hz (P < 0.05). These data indicate that the action potential discharge in nodose C-fibres in response to histamine is predominately due to histaminergic H1 receptors.

Methacholine causes action potential discharge in nodose C-fibres

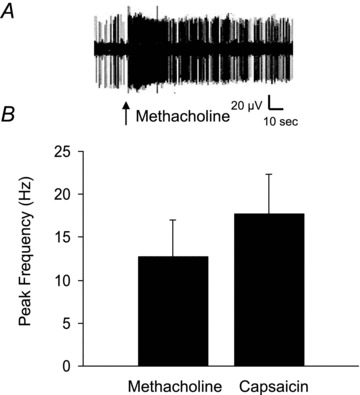

In order to address the hypothesis that the histamine-induced activation of nodose C-fibres was secondary to bronchoconstriction, we examined the ability of methacholine, an unrelated bronchoconstrictor to activate nodose C-fibres. We evaluated the effect of a 1 ml bolus of 10 μm methacholine, as this concentration is approximately equieffective as a 1 ml bolus of 30 μm histamine. Methacholine mimicked the histamine response in causing robust action potential discharge in nodose C-fibres that averaged 73 ± 19 total action potentials above baseline with a peak frequency of 13 ± 4 Hz (n = 6, Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Methacholine causes action potential discharge in nodose C-fibres.

Single nodose C-fibres were exposed to a 1 ml bolus of methacholine (10 μm) or capsaicin (1 μm). A, a recording of action potential discharge of a nodose C-fibre in response to methacholine. Arrow indicates the onset of methacholine injection. B, the peak frequency of action potential discharge above baseline in response to methacholine. The response of the same fibres to the TRPV1 agonist capsaicin (1 μm) is shown for comparison. Data are means ± SEM, n = 7.

We sought to determine the muscarinic receptor involved in this response, and as methacholine contracts airway smooth muscle via M3 receptor activation (Haddad et al. 1991), we compared responses to methacholine in tissues before and after pretreatment with the preferential M3 receptor antagonist 4-DAMP (100 nm). 4-DAMP inhibited responses to 10 μm methacholine, reducing the total number of action potentials generated from 125 ± 34 to 35 ± 16, and the peak frequency of action potential discharge from 11 ± 2 to 2 ± 1 Hz (n = 3 paired experiments, data not shown).

Muscarinic M3 receptor expression in intrapulmonary nodose C-fibres

Histamine is known to be capable of directly interacting with H1 receptors on guinea pig nodose neurons leading to inhibition of potassium currents (Undem et al. 1993), but there is little evidence for muscarinic M3 receptors on nodose C-fibres. To determine if the nodose lung C-fibres express muscarinic M3 receptors we evaluated mRNA expression in single neurons traced from the lungs. We focused on those lung-specific neurons that expressed TRPV1 (as a marker for C-fibres). The vast majority of presumed nodose C-fibre neurons failed to express M3 receptor mRNA – we noted that there was no M3 receptor mRNA expression detectable in 8 of 11 TRPV1 expressing neurons (not shown).

Is the histamine-induced action potential discharge secondary to smooth muscle contraction?

To determine whether the nodose C-fibre activation by bronchoconstricting agonists is dependent on the mechanical stimulus produced by airway smooth muscle contraction, we simultaneously measured action potential discharge and tracheal perfusion pressure, and examined the effect of inhibition of smooth muscle contraction on histamine-induced C-fibre activation. Histamine caused an average increase in tracheal perfusion pressure that measured 26.4 ± 3.1 mmHg over baseline (n = 25). The onset of the increase in perfusion pressure occurred within 5 s of the initiation of histamine delivery, and peaked within 25.3 ± 4.9 s (Fig. 3). As can be seen in the example in Fig. 3, the nodose C-fibre discharge typically peaks during the dynamic phase of the increase in tracheal pressure.

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that nodose C-fibre discharge occurred due to mechanical displacement caused by smooth muscle contraction. In order to test this hypothesis we compared the tracheal pressure before and after treatment with a concentration of the myosin light chain kinase inhibitor ML-7 (30 μm) known to block airway smooth muscle contraction (Matsumoto et al. 2007). ML-7 significantly inhibited the increase in tracheal pressure in response to histamine reducing it by 83 ± 8% (n = 5, P < 0.01; Fig. 3). Likewise, functionally antagonizing airway smooth muscle contraction with the β-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol (100 μm) reduced histamine-induced increases in tracheal perfusion pressure by an average of 66 ± 6% (n = 5, P < 0.05; Fig. 3). Similarly, both ML-7 and isoproterenol inhibited histamine-induced activation of nodose-C-fibres. In five experiments, inhibition of smooth muscle contraction with ML-7 significantly decreased the average total number of action potentials from 157 ± 33 to 32 ± 5, and the mean peak frequency from 15 ± 3 to 2 ± 0 Hz (P < 0.01). Isoproterenol inhibited the histamine-induced action potential discharge from 171 ± 36 to 55 ± 23 and reduced peak frequency of action potential discharge from 21 ± 2 to 5 ± 1 Hz (n = 5, Fig. 3). ATP did not increase tracheal perfusion pressure, and action potential discharge in response to ATP (100 μm) was unaffected by inhibition of airway smooth muscle with either isoproterenol or ML-7, as the ATP-induced action potential discharged averaged 19 ± 3 before and 17 ± 6 after ML-7; and 22 ± 3 and 14 ± 3 before and after isoproterenol, respectively (data not shown, P > 0.05).

P2X receptor antagonism inhibits histamine- and methacholine-induced action potential discharge

Several reports in other tissue beds have noted that muscle contraction and mechanical force can lead to ATP release from cells that can then activate nerves via purinergic receptors (Ferguson et al. 1997; Hanna & Kaufman, 2003; Cockayne et al. 2005). A purinergic mechanism would be consistent with the observation that nodose, but not jugular C-fibres were sensitive to smooth muscle contractions since only nodose C-fibres are activated by ATP (Undem et al. 2004; Kwong et al. 2008).

We exposed nodose C-fibres to histamine before and after treatment with a high concentration (100 μm) of the P2X3–P2X2/3-selective receptor antagonist AF-353 (Gever et al. 2006). In preliminary studies, this was the concentration required to block the nodose C-fibre response to a near maximally effective concentration of ATP (1 ml of 100 μm). AF-353 strongly inhibited both the total number of action potentials and the peak frequency of action potentials generated in response to histamine from 123 ± 32 to 21 ± 5, and 8 ± 1 to 3 ± 1 Hz, respectively (Fig. 4). A 10-fold lower concentration of AF-353 (10 μm) did not significantly inhibit histamine-induced action potential discharge; (81 ± 23 vs. 90 ± 25 in the absence and presence of AF-353, respectively). Although this concentration of AF-353 modestly inhibited the response to 10 μm ATP, it failed to inhibit the response to 100 μm ATP, which evoked 89 ± 26 action potentials and 101 ± 42 action potentials in the absence and presence of 10 μm AF-353, respectively (n = 4). It should be kept in mind that this is a 1 ml volume of ATP added (over ∼20 s) to the perfusate; the actual concentration of ATP (and indeed any agonist tested in this manner) at the nerve ending cannot be determined in this experimental model.

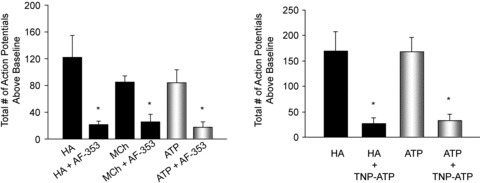

Figure 4. Effect of P2X3–P2X2/3 receptor antagonists on histamine-induced action potential discharge in nodose C-fibres.

The total number of action potentials generated in response to a 1 ml bolus of histamine (HA, 30 μm), methacholine (MCh, 10 μm) or ATP (100 μm) before and after 20 min of perfusion with the P2X3–P2X2/3 receptor antagonist AF-353 (100 μm), or the P2X2/3 selective antagonist TNP-ATP (30 μm). Data are means ± SEM, n = 6 HA/AF-353, n = 3 MCh/AF-353; n = 4 HA/TNP-ATP; *P < 0.05. The peak action potential frequency in response to capsaicin averaged 10 ± 2 and 8 ± 0 in the presence of AF-353 and TNP-ATP, respectively. This response is not different than untreated controls (P > 0.05, data not shown).

We next evaluated the effect of TNP-ATP, a nucleotide P2X1, P2X3 and P2X2/P2X3 antagonist that is structurally unrelated to AF-353 (Gever et al. 2006). In preliminary studies we found that 30 μm was the minimum concentration capable of blocking the action potential discharge in response to 1 ml infusion of 100 μm ATP. At this concentration, TNP-ATP mimicked the effect of AF-353 by strongly inhibiting (P < 0.01) the histamine-induced action potential discharge, decreasing the total number of action potentials generated from 170 ± 38 to 27 ± 10 (Fig. 4). Peak frequency of action potential discharge was reduced from 11 ± 3 to 3 ± 1 Hz.

Activation of nodose C-fibres by methacholine was also inhibited by P2X2/3 receptor antagonism. Treatment with AF-353 (100 μm) reduced the average total number of action potentials generated in response to MCh from 85 ± 9 to 26 ± 10 (Fig. 4) and the peak frequency of action potential discharge from 10 ± 3 to 2 ± 1 (n = 3, data not shown).

In these experiments, the histamine- and methacholine-induced increases in tracheal perfusion pressure were unaffected by the presence of AF-353 or TNP-ATP (P > 0.1, data not shown). Also, in these experiments, the P2X receptor antagonists did not inhibit the responses to capsaicin. Peak frequency of action potential discharge in response to capsaicin measured 10 ± 2 Hz and 8 ± 0 Hz in the presence of AF-353 and TNP-ATP, respectively. These values are not different from control (P > 0.05, unpaired t test). The receptive fields could still be activated by punctate mechanical stimulation using von Frey fibres in the presence of AF-353 or TNP-ATP.

Apyrase combined with A1 and A2 receptor antagonists inhibits the nodose C-fibre response to histamine

If locally released ATP is acting in a paracrine fashion, adding apyrase, an enzyme that hydrolyses ATP to AMP, might be expected to inhibit the overall nodose C-fibre response. Histamine-induced nodose C-fibre activation was studied before and after perfusion of the tissues with apyrase at concentrations of 5 U ml−1 or 10 U ml−1. This treatment had no effect on the action potential discharge in response to histamine. Surprisingly, 10 U ml−1 apyrase also failed to inhibit the nodose C-fibre response to exogenously applied 100 μm ATP (n = 2, not shown). We postulated that ATP was being broken down to adenosine, which in turn stimulated the nodose C-fibres. Chuaychoo et al. (2006) have noted that adenosine is an effective and potent activator of intrapulmonary nodose C-fibres in the guinea pig, and that this activation can be blocked by a combination of A1 and A2 receptor antagonists. Therefore we repeated the apyrase experiments in preparations in which the relevant adenosine receptors were blocked using the same antagonists as Chuayachoo et al., namely DPCPX (100 nm) and SCH58261 (100 nm) (Chuaychoo et al. 2006). In initial preliminary experiments we noted that treatment with DPCPX and SCH58261 did not inhibit the histamine-induced action potential discharge, indicating that adenosine is not normally participating along with ATP in the mediation of afferent activation. The respective total number of action potentials and peak frequency of action potential discharge averaged 183 ± 62 and 16 ± 1 Hz before, and 195 ± 10 and 10 ± 3 after, treatment with the adenosine receptor antagonists (n = 4). In the presence of these antagonists, apyrase strongly inhibited the exogenous ATP-induced action potential discharge in four experiments from a total number of 125 ± 23 to 33 ± 11, and peak frequency of action potential discharge from 17 ± 3 to 6 ± 2 Hz (Fig. 5). Responses to histamine were likewise inhibited by apyrase and the A1 and A2 antagonists, reducing the total number of action potentials from 120 ± 29 to 31 ± 9, and the peak frequency of action potential discharge from 14 ± 3 to 3 ± 0 Hz (n = 4, Fig. 5).

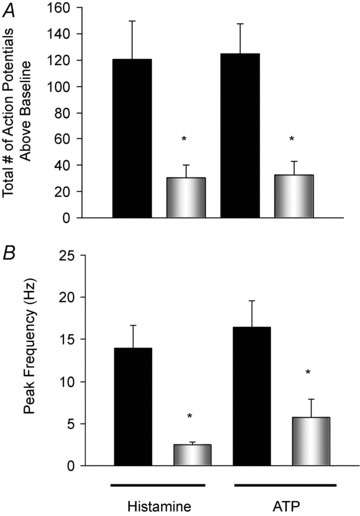

Figure 5. Effect of apyrase and adenosine A1 and A2A receptor blockade on histamine-induced action potential discharge in nodose C-fibres.

The total number of action potentials generated (A), and peak frequency of action potential discharge (B) in response to a 1 ml bolus of histamine (30 μm) or ATP (100 μm) before (solid bars) and after (open bars) 20 min of perfusion with the ATPase apyrase (5 U ml−1) in combination with the A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX (100 nm) and A2A receptor antagonist SCH58261 (100 nm). Responses to capsaicin in C-fibres treated with apyrase and the adenosine receptor antagonists were not different from those in untreated controls averaging a peak frequency discharge of 15 ± 6 (P > 0.05, data not shown). Data are means ± SEM, n = 4. *P≤ 0.05.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that histamine and methacholine activate guinea pig vagal nodose, but not jugular, intrapulmonary C-fibres by a mechanism that is secondary to the mechanical effect of bronchial smooth muscle contraction. The data also support the hypothesis that ATP released as a consequence of bronchial smooth muscle contraction is ultimately responsible for stimulating the C-fibres via interaction with purinergic P2X3 containing receptors, with the P2X2/3 heterotrimers likely to be mediating most, if not all, of this effect.

The conclusion that the histamine- and methacholine-induced C-fibre activation was secondary to the mechanical effect of bronchoconstriction is supported by several lines of evidence. First, both the bronchoconstriction and C-fibre activation were strongly inhibited by blocking histaminergic H1 receptors and muscarinic M3 receptors, respectively. Second, the action potential discharge in response to histamine and methacholine was temporally correlated with the dynamic phase of the increase in tracheal perfusion pressure. Third, functionally antagonizing the bronchoconstriction with isoproterenol strongly inhibited the C-fibre activation (without inhibiting ATP- or capsaicin-induced activation). Fourth, inhibiting the smooth muscle contraction with the myosin light chain kinase inhibitor ML-7 strongly inhibited the histamine-induced C-fibre activation without inhibiting the response to either ATP or capsaicin. Fifth, relatively few nodose C-fibre neurons (as denoted by TRPV1 expression) traced from the lungs expressed muscarinic M3 receptor mRNA implicating an indirect mechanism for methacholine-induced activation. Finally, the minority of nodose C-fibres that were not immediately accessible to ATP delivered via the trachea (possibly because their terminals were not in the airways) were not activated by histamine.

Virtually all C-fibres studied in the guinea pig respiratory tract can be activated by mechanical stimulation with von Frey filaments. It is therefore possible that the nodose C-fibres are situated such that bronchial smooth muscle contraction mechanically perturbs the terminal membrane directly, leading to suprathreshold generator potentials and action potential discharge. Alternatively, vagal C-fibres are susceptible to chemical stimulation by myriad endogenous autacoids, so there may be chemical intermediates involved in the action potential discharge caused by bronchoconstriction. With respect to this latter possibility, we considered ATP to be a candidate, as ATP stimulates nodose C-fibres (Undem et al. 2004), and is known to be released in numerous tissues, including airways, upon mechanical perturbation (Ferguson et al. 1997; Knight et al. 2002; Wynn et al. 2003; Button et al. 2007; De Proost et al. 2009).

We have previously reported that nodose C-fibres in the guinea pig and mouse lungs are strongly activated by ATP, and that this activation is secondary to stimulation of purinergic receptors, most likely the ionotropic P2X2/3 receptors (Kwong et al. 2008; Nassenstein et al. 2010). Neurons that express only the P2X3 subunit, and presumably form homomeric P2X3 receptors do not respond to ATP with action potential discharge (Kwong et al. 2008). In the present study, AF-353, a potent and highly selective human P2X3/P2X2/3 antagonist (Gever et al. 2006), had no effect on the histamine- or methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction, but did block the consequent nodose C-fibre activation. Although the affinity of AF-353 has not yet been assessed specifically at guinea pig P2X2/3 receptors, it should be noted that this required a relatively high concentration of the drug, one capable of inhibiting the response to 1 ml of 100 μm ATP. Lower concentrations that failed to inhibit the response 100 μm ATP also failed to inhibit the C-fibre response to histamine. It is noteworthy that this concentration of AF-353 had no effect on the capsaicin-induced activation of nodose C-fibres. We also report that TNP-ATP, a structurally unrelated P2X3/P2X2/3 antagonist (Gever et al. 2006), strongly inhibited the histamine-induced C-fibre activation.

The experiments using ayprase add further independent support to the hypothesis that released ATP acts as a necessary intermediary in the bronchoconstriction-induced nodose C-fibre activation. Apyrase hydrolyses ATP to AMP. Apyrase alone, however, had no effect on the histamine- (or ATP-) induced nodose C-fibre activation. This can be explained by the fact that adenosine, the eventual breakdown product of the interaction between apyrase and ATP, is a potent and effective activator of nodose C-fibres via adenosine A1 and A2A receptor stimulation (Chuaychoo et al. 2006). When the apyrase experiment was repeated in tissues in which the relevant adenosine receptors were antagonized, it effectively inhibited both ATP- and histamine-induced nodose C-fibre activation. The fact that apyrase alone had no inhibitory effect argues against a non-specific inhibitory effect of the enzyme on C-fibres. Moreover, the combination of apyrase and adenosine receptor blockade had no effect on capsaicin-induced activation, also arguing against a non-selective effect.

The conclusion that ATP is a necessary intermediate for bronchoconstriction-induced nodose C-fibre activation explains why jugular C-fibres were not activated by histamine. Although guinea pig jugular C-fibres are situated in large airways (Undem et al. 2004), they apparently do not express P2X2 receptor subunits, and are not activated by ATP (Undem et al. 2004; Kwong et al. 2008).

The data provide little insight into the source of the activating ATP. The observation that concentrations of the P2X receptor antagonists capable of inhibiting 1 ml of 100 μm ATP were required to block the histamine and methacholine-induced C-fibre activation suggests that the C-fibre terminals were exposed to relatively large local concentrations of ATP. That relatively large local concentrations of extracellular ATP are achieved is consistent with the assertion that release of cellular ATP may yield local very high extracellular ATP concentrations in the 10–100 μm range (Ford & Cockayne, 2011). It should be kept in mind that the 100 μm ATP was added to the perfusate as a 1 ml bolus to the perfusing buffer; the concentration at the nerve terminal is unknown. Nevertheless that relatively large ATP concentrations were locally reached indicates that the source of the ATP was close to the terminals. One candidate source of ATP are the neuroepithelial bodies (NEBs). NEBs are known to be capable of releasing ATP that can then act in a paracrine fashion on nearby cells (De Proost et al. 2009). The innervation of NEBs has not been investigated in guinea pigs. In rats, however, the nodose fibres in close proximity to NEBS do not appear to be C-fibres, but rather capsaicin-insensitive myelinated A-fibres (Brouns et al. 2003, 2006). Our studies do not rule out other potential sources including, epithelial cells, smooth muscle cells, other cell resident cell types, or even the nerve terminals themselves as the key source of the activating ATP.

Although the requisite mechanical force to induce ATP release was presumably due to smooth muscle contraction, the mechanical energy produced may also perturb all of the perfused tissue. It is somewhat instructive that nodose C-fibres with terminals located such that they were activated by ATP preferentially via the pulmonary artery rather than the trachea responded poorly or not at all to bronchoconstriction. This leads to the guarded conclusion that nodose C-fibres whose terminals reside in close proximity to the intrapulmonary airways may be activated more robustly by the forces produced during bronchoconstriction than C-fibres that terminate outside the airway wall.

The concept that a mechanical event leads to afferent nerve activation via purinergic mechanisms is not unique to C-fibres innervating the respiratory system. For example, distention of the bladder is thought to activate afferent nerves via a purinergic intermediate (Vlaskovska et al. 2001; Calvert et al. 2008). Likewise the exercise pressor reflex is thought to involve purinergic activation of afferent nerves secondary to the mechanical effects of skeletal muscle contraction (Hanna & Kaufman, 2003; McCord et al. 2010).

There have been few studies evaluating the effect of histamine or methacholine on vagal C-fibres in guinea pigs. Histamine failed to activate C-fibres in a guinea pig tracheal preparation (Fox et al. 1993). This is consistent with the present findings and can be explained by the fact that guinea pig tracheal C-fibres originate largely from the jugular, and not nodose, ganglia (Ricco et al. 1996). Bergren, (1997) convincingly noted that histamine aerosol activated vagal fast-conducting rapidly adapting afferent nerves in guinea pig lungs by a mechanism that is blocked by isoproterenol, but failed to activate C-fibres. As we have mentioned, bronchoconstriction activates only a subset of intrapulmonary C-fibres. Jugular C-fibres, which represent >50% of the vagal C-fibres innervating the guinea pig respiratory tract, are not activated, and neither were nodose C-fibres presumed to terminate outside the airway tree. In Bergren's study it cannot be determined if the C-fibres were jugular or nodose derived, nor was the location of the terminals determined. It is also possible that the rate of bronchoconstriction is an important variable. When isoproterenol was present the rate and magnitude of the contraction were reduced and the action potential discharge nearly eliminated. In the present study we perfused a large concentration of histamine that is likely to have led to a more rapid rise in perfusion pressure than what is achieved in vivo with inhalation of an aerosol.

Others have noted that histamine can stimulate subsets of vagal C-fibres in lungs of dogs, rats and cats (Armstrong & Luck, 1974; Coleridge et al. 1978; Lee & Morton, 1993). Histamine aerosol also causes reflexes commonly associated with C-fibre activation, such as changes in respiratory frequency (Schelegle et al. 2000). The mechanical effect of tissue distention has been found to activate vagal C-fibres in the oesophagus (Yu et al. 2005), heart (Veelken et al. 2003) and inflamed airways (Lee & Morton, 1993). The work presented in the present study raises the question as to the extent to which these activities are secondary to purinergic mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by The National Institutes of Health (RO1HL062296 and IF31HL099635-01).

Glossary

- KRBS

Krebs–Ringer–bicarbonate solution

- NEB

neuroepithelial body

Author contributions

L.A.W. performed the vast majority of experiments and data analysis, and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. A.P.F. provided valuable assistance in the studies related to purinergic pharmacology. B.J.U. oversaw the entire project, and assisted in writing the final drafts of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for publication. All of the work for this project was carried out at The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

References

- Agostoni E, Chinnock JE, De Daly MB, Murray JG. Functional and histological studies of the vagus nerve and its branches to the heart, lungs and abdominal viscera in the cat. J Physiol. 1957;135:182–205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong DJ, Luck JC. A comparative study of irritant and type J receptors in the cat. Respir Physiol. 1974;21:47–60. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(74)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergren DR. Sensory receptor activation by mediators of defense reflexes in guinea-pig lungs. Respir Physiol. 1997;108:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(97)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergren DR. Prostaglandin involvement in lung C-fiber activation by substance P in guinea pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1918–1927. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01276.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns I, De Proost I, Pintelon I, Timmermans JP, Adriaensen D. Sensory receptors in the airways: neurochemical coding of smooth muscle-associated airway receptors and pulmonary neuroepithelial body innervation. Auton Neurosci. 2006;126–127:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns I, Van Genechten J, Hayashi H, Gajda M, Gomi T, Burnstock G, Timmermans JP, Adriaensen D. Dual sensory innervation of pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:275–285. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0117OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button B, Picher M, Boucher RC. Differential effects of cyclic and constant stress on ATP release and mucociliary transport by human airway epithelia. J Physiol. 2007;580:577–592. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert RC, Thompson CS, Burnstock G. ATP release from the human ureter on distension and P2X3 receptor expression on suburothelial sensory nerves. Purinergic Signal. 2008;4:377–381. doi: 10.1007/s11302-008-9123-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuaychoo B, Lee MG, Kollarik M, Pullmann R, Jr, Undem BJ. Evidence for both adenosine A1 and A2A receptors activating single vagal sensory C-fibres in guinea pig lungs. J Physiol. 2006;575:481–490. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuaychoo B, Lee MG, Kollarik M, Undem BJ. Effect of 5-hydroxytryptamine on vagal C-fiber subtypes in guinea pig lungs. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2005;18:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockayne DA, Dunn PM, Zhong Y, Rong W, Hamilton SG, Knight GE, Ruan HZ, Ma B, Yip P, Nunn P, McMahon SB, Burnstock G, Ford AP. P2X2 knockout mice and P2X2/P2X3 double knockout mice reveal a role for the P2X2 receptor subunit in mediating multiple sensory effects of ATP. J Physiol. 2005;567:621–639. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC, Baker DG, Ginzel KH, Morrison MA. Comparison of the effects of histamine and prostaglandin on afferent C-fiber endings and irritant receptors in the intrapulmonary airways. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1978;99:291–305. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-4009-6_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge JC, Coleridge HM. Afferent vagal C fibre innervation of the lungs and airways and its functional significance. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;99:1–110. doi: 10.1007/BFb0027715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Proost I, Pintelon I, Wilkinson WJ, Goethals S, Brouns I, Van Nassauw L, Riccardi D, Timmermans JP, Kemp PJ, Adriaensen D. Purinergic signaling in the pulmonary neuroepithelial body microenvironment unraveled by live cell imaging. FASEB J. 2009;23:1153–1160. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-109579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson DR, Kennedy I, Burton TJ. ATP is released from rabbit urinary bladder epithelial cells by hydrostatic pressure changes–a possible sensory mechanism? J Physiol. 1997;505:503–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.503bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford AP, Cockayne DA. ATP and P2X purinoceptors in urinary tract disorders. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2011:485–526. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-16499-6_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AJ, Barnes PJ, Urban L, Dray A. An in vitro study of the properties of single vagal afferents innervating guinea-pig airways. J Physiol. 1993;469:21–35. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gever JR, Cockayne DA, Dillon MP, Burnstock G, Ford AP. Pharmacology of P2X channels. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452:513–537. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad EB, Landry Y, Gies JP. Muscarinic receptor subtypes in guinea pig airways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1991;261:L327–333. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1991.261.4.L327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna RL, Kaufman MP. Role played by purinergic receptors on muscle afferents in evoking the exercise pressor reflex. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:1437–1445. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01011.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CY, Gu Q, Hong JL, Lee LY. Prostaglandin E2 enhances chemical and mechanical sensitivities of pulmonary C fibers in the rat. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:528–533. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9910059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajekar R, Proud D, Myers AC, Meeker SN, Undem BJ. Characterization of vagal afferent subtypes stimulated by bradykinin in guinea pig trachea. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:682–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karla W, Shams H, Orr JA, Scheid P. Effects of the thromboxane A2 mimetic, U46,619, on pulmonary vagal afferents in the cat. Respir Physiol. 1992;87:383–396. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(92)90019-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MP, Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC, Baker DG. Bradykinin stimulates afferent vagal C-fibers in intrapulmonary airways of dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1980;48:511–517. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.48.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GE, Bodin P, De Groat WC, Burnstock G. ATP is released from guinea pig ureter epithelium on distension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F281–288. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00293.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong K, Kollarik M, Nassenstein C, Ru F, Undem BJ. P2X2 receptors differentiate placodal vs. neural crest C-fiber phenotypes innervating guinea pig lungs and esophagus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L858–865. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90360.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LY, Morton RF. Histamine enhances vagal pulmonary C-fiber responses to capsaicin and lung inflation. Respir Physiol. 1993;93:83–96. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(93)90070-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Moir LM, Oliver BG, Burgess JK, Roth M, Black JL, McParland BE. Comparison of gel contraction mediated by airway smooth muscle cells from patients with and without asthma. Thorax. 2007;62:848–854. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.070474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord JL, Tsuchimochi H, Kaufman MP. P2X2/3 and P2X3 receptors contribute to the metaboreceptor component of the exercise pressor reflex. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:1416–1423. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00774.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed SP, Higenbottam TW, Adcock JJ. Effects of aerosol-applied capsaicin, histamine and prostaglandin E2 on airway sensory receptors of anaesthetized cats. J Physiol. 1993;469:51–66. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutoh T, Bonham AC, Kott KS, Joad JP. Chronic exposure to sidestream tobacco smoke augments lung C-fiber responsiveness in young guinea pigs. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:757–768. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassenstein C, Taylor-Clark TE, Myers AC, Ru F, Nandigama R, Bettner W, Undem BJ. Phenotypic distinctions between neural crest and placodal derived vagal C-fibres in mouse lungs. J Physiol. 2010;588:4769–4783. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricco MM, Kummer W, Biglari B, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Interganglionic segregation of distinct vagal afferent fibre phenotypes in guinea-pig airways. J Physiol. 1996;496:521–530. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelegle ES, Mansoor JK, Green JF. Interaction of vagal lung afferents with inhalation of histamine aerosol in anesthtized dogs. Lung. 2000;178:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s004080000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undem BJ, Chuaychoo B, Lee MG, Weinreich D, Myers AC, Kollarik M. Subtypes of vagal afferent C-fibres in guinea-pig lungs. J Physiol. 2004;556:905–917. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.060079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undem BJ, Hubbard W, Weinreich D. Immunologically induced neuromodulation of guinea pig nodose ganglion neurons. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1993;44:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veelken R, Stetter A, Dickel T, Hilgers KF. Bimodality of cardiac vagal afferent C-fibres in the rat. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446:516–522. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1078-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaskovska M, Kasakov L, Rong W, Bodin P, Bardini M, Cockayne DA, Ford AP, Burnstock G. P2X3 knock-out mice reveal a major sensory role for urothelially released ATP. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5670–5677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05670.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn G, Rong W, Xiang Z, Burnstock G. Purinergic mechanisms contribute to mechanosensory transduction in the rat colorectum. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1398–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Undem BJ, Kollarik M. Vagal afferent nerves with nociceptive properties in guinea-pig oesophagus. J Physiol. 2005;563:831–842. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]